Abstract

Purpose

The perceptual consequences of rate reduction, increased vocal intensity, and clear speech were studied in speakers with multiple sclerosis (MS), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and healthy controls.

Method

Seventy-eight speakers read sentences in habitual, clear, loud, and slow conditions. Sentences were equated for peak amplitude and mixed with multitalker babble for presentation to listeners. Using a computerized visual analog scale, listeners judged intelligibility or speech severity as operationally defined in Sussman and Tjaden (2012).

Results

Loud and clear but not slow conditions improved intelligibility relative to the habitual condition. With the exception of the loud condition for the PD group, speech severity did not improve above habitual and was reduced relative to habitual in some instances. Intelligibility and speech severity were strongly related, but relationships for disordered speakers were weaker in clear and slow conditions versus habitual.

Conclusions

Both clear and loud speech show promise for improving intelligibility and maintaining or improving speech severity in multitalker babble for speakers with mild dysarthria secondary to MS or PD, at least as these perceptual constructs were defined and measured in this study. Although scaled intelligibility and speech severity overlap, the metrics further appear to have some separate value in documenting treatment-related speech changes.

Keywords: intelligibility, speech severity, dysarthria, rate reduction, clear speech, loud speech

Maximizing speech intelligibility and naturalness are common goals of speech-oriented, behavioral treatments for dysarthria (Duffy, 2013; Yorkston, Beukelman, Strand, & Hakel, 2010). Global dysarthria treatment techniques, which extend across the time domain of an entire utterance and simultaneously impact multiple speech components (i.e., respiration, phonation, articulation, resonance) are intended to improve intelligibility (Hustad & Weismer, 2007; Yorkston, Hakel, Beukelman, & Fager, 2007). The following sections consider the rationale for using the global therapy techniques of rate reduction, an increased vocal intensity, and clear speech to maximize intelligibility in dysarthria (also see reviews in Duffy, 2013; Hustad & Weismer, 2007; Ramig, 1992; Sapir, Ramig, & Fox, 2011; Weismer, 2008; Weismer, Yunusova, & Bunton, 2012; Yorkston et al., 2007, 2010). The impact of these therapy techniques on perceived speech quality as inferred from judgments of speech naturalness, acceptability, normalcy, and so forth, also is considered.

Rate Reduction

Regardless of the method for reducing articulation rate, a reduced rate of speech is thought to enhance intelligibility for speakers with dysarthria because a slower-than-normal rate of speech sound production gives talkers increased time to achieve more canonical vocal tract shapes that are distinctive from one another. A reduced rate of speech may also enhance “coordination” among the speech subsystems. In addition to the possibility of these speech production adjustments, a slowed rate may benefit intelligibility by providing the listener increased time to process the acoustic signal as well as more clearly demarcating word boundaries which, in turn, may facilitate lexical segmentation. Although empirical support for these assertions is still fairly limited, Yorkston et al. (2007) reviewed 17 dysarthria studies investigating rate reduction outcomes and concluded that findings generally supported a relationship between a slower-than-habitual rate and improved intelligibility. More recently, Van Nuffelen, De Bodt, Vanderwegen, Van de Heyning, and Wuyts (2010) studied the impact of seven rate-control methods on scaled intelligibility for passages read by speakers with a variety of dysarthrias and neurological diagnoses. Group results indicated decreased intelligibility for each rate control technique relative to habitual or typical speech. Similarly, Tjaden and Wilding (2004) reported no improvement in scaled intelligibility for a reading passage produced at a slower-than-normal rate by speakers with multiple sclerosis (MS) and Parkinson’s disease (PD; also see McRae, Tjaden, & Schoonings, 2002). Finally, speech produced by individuals with dysarthria at a slower-than-normal rate tends to be perceived as less natural than speech produced at a habitual or typical rate, regardless of whether the reduced rate improves intelligibility (Dagenais, Brown, & Moore, 2006; Hanson, Beukelman, Fager, & Ullman, 2004; Yorkston, Hammen, Beukelman, & Traynor, 1990).

Increased Vocal Intensity

Therapeutic techniques that increase vocal intensity, whether by means of a standardized training program like the Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT; Ramig, Bonitati, Lemke, & Horii, 1994; Ramig, Countryman, Thompson, & Horii, 1995) or by less formalized approaches (Duffy, 2013; Yorkston et al., 2010), seek to improve intelligibility for individuals with dysarthria by increasing effort in the respiratory–phonatory mechanism. In addition to increasing average sound pressure level (SPL) and fundamental frequency (f0) range, adjustments in segmental articulation may accompany an increased vocal intensity (Sapir, Spielman, Ramig, Story, & Fox, 2007; Wenke, Cornwell, & Theodoros, 2010; Yorkston et al., 2007). The improved audibility of speech produced at a higher SPL appears to partially explain increased intelligibility (Neel, 2009; Yorkston et al., 2007; but see Kim & Kuo, 2012). However, variables such as enhanced segmental contrast and increased prosodic modulation also appear to play a role in explaining the improved intelligibility of speech produced at an increased vocal intensity by speakers with dysarthria that has been reported in at least some studies (e.g., Neel, 2009; Tjaden & Wilding, 2004). As noted by Yorkston et al. (2010), the impact of an increased vocal intensity on perceptual constructs other than intelligibility has not been systematically studied in dysarthria. Improvements in perceived vowel quality or goodness as well as improvements in voice (i.e., breathiness, monotone, shakiness, etc.), however, have been reported (Ramig, 1992; Sapir et al., 2007; Yorkston et al., 2007).

Clear Speech

Clear speech is a style of talking characterized by exaggerated or hyperarticulation. A slower-than-normal rate and increased vocal intensity also characterize clear speech, but the focus is on hyperarticulation. Although clear speech has not been studied much in dysarthria, an extensive literature focusing on neurologically normal talkers supports using clear speech therapeutically to improve intelligibility in dysarthria, with studies reporting improvements in intelligibility of up to 26% relative to conversational or habitual speech (see reviews in Smiljanić & Bradlow, 2009; Uchanski, 2005). The increased intelligibility of clear speech is thought to derive from similar types of production adjustments that might explain improvements in intelligibility associated with a slow rate or increased vocal intensity.

In one of the few dysarthria studies of clear speech, Beukelman, Fager, Ullman, Hanson, and Logemann (2002) found an 8% intelligibility improvement, on average, for clear versus habitual sentences produced by speakers with dysarthria secondary to traumatic brain injury (TBI). Although the increase in intelligibility was not statistically significant, an intelligibility increase of 8% may be clinically meaningful (Van Nuffelen et al., 2010). In a follow-up study, Hanson et al. (2004) obtained judgments of effectiveness and acceptability from a variety of listener groups (i.e., family, allied health professionals, speech–language pathologists, general public). All listener groups ranked the clear sentences as more effective and acceptable than habitual productions. In addition, for most listener groups, clear sentences judged to be more intelligible were also judged to be more acceptable. Sentences produced at a slower-than-normal rate (i.e., alphabet supplementation) were ranked as even more effective or acceptable than clear sentences. However, overall results for a slower-than-normal rate indicated that sentences judged to be more intelligible were judged as less acceptable or effective. This example highlights the complex relationship between intelligibility and perceptual constructs such as acceptability.

Summary and Purpose

Although rate reduction, increased vocal intensity, and clear speech hold promise for maximizing intelligibility in dysarthria, studies directly comparing these therapeutic techniques are lacking. Clear speech is a particularly interesting comparison to the other two techniques as clear speech is associated with a simultaneous increase in vocal intensity and lengthened speech durations, but the magnitude of these adjustments is less than for loud or slow speech techniques individually (Smiljanić & Bradlow, 2009; Tjaden, Lam, & Wilding, 2013). Comparison of clear speech and an increased vocal intensity further allows for inferences concerning the relative merits of a speech manipulation emphasizing articulatory behavior versus one emphasizing respiratory–phonatory behavior.

In addition, although separate studies have reported the effect of rate reduction, clear speech, and an increased vocal intensity on intelligibility, their effect on perceived speech quality is poorly understood, especially for clear speech and an increased vocal intensity. Moreover, there is conflicting evidence as to whether listeners distinguish among the perceptual constructs of intelligibility, naturalness, acceptability, severity, and so forth (Dagenais et al., 2006; Dagenais, Watts, Turnage, & Kennedy, 1999; Hanson et al., 2004; Southwood & Weismer, 1993; Sussman & Tjaden, 2012; Weismer, Jeng, Laures, Kent, & Kent, 2001; Whitehill, Ciocca, & Yiu, 2004).

In an effort to better characterize the speech of individuals with dysarthria over and above the speakers’ intelligibility, we recently compared word and sentence intelligibility with perceptual impressions of “speech severity” for speakers with PD, MS, and healthy controls (Sussman & Tjaden, 2012). In addition to clinical metrics of single word and sentence intelligibility, perceptual judgments for a paragraph reading task were obtained wherein listeners were instructed not to judge intelligibility but to focus on speech naturalness and prosody and to judge the overall severity of the impairment (i.e., operationally defined construct of speech severity). Intelligibility metrics did not differentiate speaker groups, but judgments of speech severity did distinguish disordered speaker groups from age- and sex-matched controls. It was suggested that the operationally defined construct of speech severity may be sensitive to aspects of speech impairment in MS and PD not captured by traditional percent correct intelligibility scores and that speech severity might prove useful for documenting treatment-related changes in speech. A limitation of this study was that intelligibility and speech severity were assessed using varied speech materials and perceptual tasks. The present study, in which judgments of intelligibility and speech severity were obtained using the same speech materials and task, provides a more rigorous evaluation of the suggestion that the construct of speech severity might provide information regarding the perceptual adequacy of spoken communication beyond that provided by intelligibility.

Thus, this study sought to compare the effect of rate reduction, an increased vocal intensity, and clear speech on judgments of intelligibility and speech severity, as operationally defined in Sussman and Tjaden (2012), for sentences produced by individuals with MS and PD. Healthy controls were included for comparison. Rate reduction, clear speech, and an increased vocal intensity are potential treatment techniques for PD and MS (Duffy, 2013), and studying multiple neurological diagnoses speaks to the generalizability of the therapy techniques. A reduced rate, increased vocal intensity, and clear speech were stimulated using magnitude production. As we and others have noted, studies using a one-time instruction should not be compared with treatment studies using training (Sapir et al., 2011; Tjaden & Wilding, 2004). However, studies using experimental manipulation or stimulation speak to the potential value of intervention techniques and help increase the scientific basis for dysarthria treatment (Yorkston et al., 2007, 2010).

Method

Speakers

The 78 speakers reported in Sussman and Tjaden (2012) also were of interest to this study. Control speakers (n = 32) included 10 men (25–70 years, M = 56) and 22 women (27–77 years, M = 57). PD speakers (n = 16) included eight men (55–78 years, M = 67) and eight women (48–78 years, M = 69) with a medical diagnosis of idiopathic PD. MS speakers (n = 30) included 10 men (29–60 years, M = 51) and 20 women (27–66 years, M = 50) with a medical diagnosis of MS. See Table 1 for a summary of speaker characteristics.

Table 1.

Summary of participant characteristics.

| Group | Males | Females | Age (years) | Years postdiagnosis | M sentence intelligibility (%) | M word intelligibility (%) | Scaled speech severity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 10 | 20 | 52 (12) | 94 (2.7) | 97 (.01) | .18 (.08) | |

| MS | 10 | 22 | 50 (12) | 14 (11) | 93 (4.5) | 96 (.03) | .44 (.25) |

| PD | 8 | 8 | 68 (9) | 9 (8) | 85 (10) | 95 (.03) | .46 (.21) |

Note. Values in parentheses are standard deviations. Sentence intelligibility scores are from the Sentence Intelligibility Test (Yorkston, Beukelman, & Tice, 1996), and single-word intelligibility was obtained using the single word test of Kent, Weismer, Kent, and Rosenbek (1989). Scaled estimates of speech severity were obtained for the Grandfather Passage. These perceptual measures are considered in detail in Sussman and Tjaden (2012). MS = multiple sclerosis; PD = Parkinson’s disease.

Participants with medical diagnoses were recruited through patient support groups and newsletters for PD or MS in western New York, whereas control speakers were recruited through posted flyers and advertisements. All participants were native speakers of standard American English, had achieved at least a high school diploma, and had visual acuity or corrected acuity adequate for reading printed materials. Hearing aid use was an exclusion criterion. Pure tone thresholds were obtained by an audiologist at the University at Buffalo Speech and Hearing Clinic for the purpose of providing a global indication of their auditory status, but no speaker was excluded on the basis of pure tone thresholds. Participants with MS and PD were taking a variety of symptomatic medications, but no one had undergone neurosurgical treatment for their disease. Speakers with PD ranged from 2 to 32 years postdiagnosis (M = 9 years, SD = 7.8 years). Four of the female participants with PD had completed LSVT. Two speakers completed the treatment more than 2 years prior to the current experiment, and two speakers had completed LSVT approximately 6 months prior to this study, with one individual enrolled in twice-monthly LSVT refresher sessions.

Speakers with MS ranged from 2 to 47 years post-diagnosis (M = 14 years, SD = 11 years). Five participants with MS had a primary progressive disease course, 18 participants had a relapsing remitting disease course, and seven participants had a secondary progressive disease course. Six speakers with MS had received dysarthria therapy within the past 5 years, with one individual receiving treatment a year before data collection. None of the MS participants had received LSVT or any treatment focused on vocal loudness. All speakers scored at least 26/30 on the standardized Mini-Mental State Examination (Molloy, 1999), with the exception of one man with MS who scored 25/30. Speakers were paid a modest fee for participating.

Percent correct word and sentence intelligibility scores and scaled estimates of speech severity for the Grandfather Passage (Duffy, 2013) in Table 1 were reported in Sussman and Tjaden (2012) and are provided here for the purpose of describing participants’ speech. Note that procedures for obtaining sentence intelligibility scores differed from the clinical implementation of the test. Briefly, stimuli were pooled across the 78 speakers, and 42 inexperienced listeners were blinded to speaker identity and neurological status. Stimuli also were presented in quiet through headphones at the same sound pressure level at which they were naturally produced by talkers. Scaled estimates of speech severity for the Grandfather Passage in Table 1 reflect mean scale values for 10 inexperienced listeners obtained using a computerized continuous visual analog scale, with scale endpoints of 0 (no impairment) and 1.0 (severe impairment). Procedures for obtaining these judgments were similar to those described in the section, Stimuli Preparation and Perceptual Task. Table 1 suggests that speakers with MS and PD had mostly preserved word and sentence intelligibility but were judged to have impaired speech, likely because of reduced speech naturalness and poorer prosody in a longer, connected speech task, as measured speech severity. The speech profile of good intelligibility but with noticeable speech impairment is consistent with Yorkston et al.’s (2010) description of mild dysarthria. Finally, as reviewed in Sussman and Tjaden (2012), we also anecdotally noted that many of the speakers with PD had reduced segmental precision and a breathy, monotonous voice. Speakers with MS also had reduced segmental precision as well as prosodic and voice deficits, with some talkers perceived as having a slow speech rate coupled with excess and equal stress, whereas others exhibited vocal harshness or hoarseness.

Experimental Speech Stimuli and Speech Tasks

Speakers read 25 Harvard Psychoacoustic Sentences (The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, 1969) in habitual, slow, loud, clear, and fast conditions. Sentences were selected from the larger corpus of Harvard Sentences to include multiple occurrences of a variety of monophthongs and diphthongs in stressed syllables of content words as well as a variety of obstruent consonants in word initial, medial, and final positions. Each sentence contained between seven and nine words. Sentences were semantically and syntactically normal and included both declaratives and imperatives. For each speaker, a random sample of the same 10 sentences produced in the habitual, slow, loud, and clear conditions was of interest. A subset of the 25 sentences was used so the perceptual task could be completed within a single listening session. Moreover, although sentences produced in the fast condition were included in the larger list of stimuli for which listeners judged intelligibility and speech severity (see section titled Stimuli Preparation and Perceptual Task), our focus was on the more frequently used global dysarthria therapy techniques of rate reduction, increased vocal loudness, and clear speech.

Audio recording took place in a quiet or sound-treated room. The acoustic signal was transduced using an AKG C410 head-mounted microphone positioned 10 cm and 45°–50° from the left oral angle. The signal was preamplified, low-pass filtered at 9.8 kHz and digitized directly to computer hard disk at a sampling rate of 22 kHz using TF32 (Milenkovic, 2005). A calibration tone also was recorded to allow for offline measure of vocal intensity (see Lam, Tjaden, & Wilding, 2012).

For each speaker and condition, a unique random ordering of Harvard sentences was recorded. The nonhabitual conditions were elicited using a magnitude production paradigm, and all speakers were given the same standard instructions that were read from a printed script. For the loud condition, speakers were instructed to produce sentences using speech twice as loud as their regular speaking voice. For the slow condition, speakers were instructed to produce the sentences at a rate half as fast as their regular rate. Speakers were further encouraged to stretch out words rather than solely insert pauses and to say each sentence on a single breath. Similar instructions have been used in other studies (e.g., McHenry, 2003). This instruction was intended to discourage speakers from only using pauses to reduce speech rate, as only adjusting pause characteristics to reduce rate would likely not enhance intelligibility (Hammen, Yorkston, & Minifie, 1994). Finally, for the clear condition, speakers were instructed to say each sentence twice as clearly as their typical speech. Speakers were told to exaggerate the movements of their mouth as how they might speak to someone in a noisy environment or to someone with a hearing loss. Speakers also were told that their speech might be slower and louder than usual. Clear speech instructions were modeled after other clear speech studies and were intended to maximize the likelihood that speakers would not only exaggerate articulation but would also increase vocal intensity and reduce rate (Smiljanić & Bradlow, 2009).

All speakers first produced sentences in the habitual condition to obtain a baseline performance (see also Darling & Huber, 2011; McHenry, 2003; Turner & Weismer, 1993). Clear speech studies also routinely elicit conversational or habitual speech prior to the clear speech style (Smiljanić & Bradlow, 2009). Five orderings of the remaining conditions were created, and speakers were randomly assigned to an order. Potential carryover effects were addressed by engaging talkers in conversation for a few minutes between conditions. Prior to recording, speakers were familiarized with the stimuli and also were allowed a brief practice period prior to recording for nonhabitual conditions. An investigator first modeled the desired speaking condition for a sentence taken from the Sentence Intelligibility Test (SIT; Yorkston et al., 2007) recorded previously for that speaker. To encourage speakers not to imitate the investigator, participants were told that their loud (or slow or clear) speech might differ from that of the investigator. Speakers then practiced using their own clear, loud, or slow speech style for a different sentence, with general feedback. Speakers with PD were recorded 1 hr prior to taking PD medications.

Acoustic measures of sound pressure level (SPL) and articulatory rate were obtained using TF32 to verify the presence of production differences among the various speaking conditions. Other production adjustments may accompany rate control, increased loudness, and clear speech. However, adjustments in rate and vocal intensity are the most obvious changes expected when a slower-than-normal rate or increased vocal intensity are stimulated. A simultaneous reduction in rate and increased vocal intensity, albeit to a lesser extent than slow or loud speech, were expected to characterize clear speech (Smiljanić & Bradlow, 2009; Uchanski, 2005).

To analyze the production characteristics of the speech, sentences first were segmented into runs, operationally defined as a stretch of speech bounded by silent periods or pauses between words of at least 200 ms (Turner & Weismer, 1993). Conventional acoustic criteria were used to identify run onsets and offsets. Articulatory rate was computed by dividing the number of syllables produced by run duration in milliseconds and multiplying by 1,000. For each speaker and condition, a mean articulatory rate was calculated by averaging articulatory rates for all speech runs. Mean SPL also was calculated for each speech run. RMS traces were generated in TF32, and voltages were converted to dB SPL in Excel with reference to each speaker’s calibration tone. The loud condition for one MS female was excluded from all analyses because of technical difficulties during recording.

Listeners

One hundred listeners participated. All listeners passed a hearing screening at 20 dB HL for octave frequencies from 250 to 8000 Hz, bilaterally. Listeners ranged in age from 18 to 30; were native speakers of standard American English; had at least a high school diploma or the equivalent; reported no history of speech, language, or hearing problems; and were unfamiliar with speech disorders. Listeners were recruited using flyers posted at the University at Buffalo and were paid a modest participation fee.

Stimuli Preparation and Perceptual Task

Speakers in this study had mostly preserved intelligibility on the clinical metrics of sentence and single-word intelligibility (see Table 1). Thus, to prevent ceiling effects and to increase task difficulty, Harvard sentences were mixed with multitalker babble as is commonly done in clear speech studies (see Smiljanić & Bradlow, 2009; Uchanski, 2005) and in select, published dysarthria studies (Bunton, 2006). Speech intelligibility measurement in adverse listening conditions also was suggested by Yorkston et al. (2007) as a future area of needed research. The challenging perceptual environment should be kept in mind when interpreting results and is also considered further in the discussion.

Sentences first were equated for peak vowel amplitude using Goldwave Version 5 (Goldwave, Inc., 2010) to minimize differences in audibility among sentences (Hustad, 2007; Kim & Kuo, 2012). The amplitude normalization assists in interpreting the source of potential variations in intelligibility and speech severity by at least minimizing the influence of one variable (i.e., audibility; see Kim & Kuo, 2012; Neel, 2009). Stimuli then were mixed with 20-talker multitalker babble (Frank & Craig, 1984; Nilsson, Soli, & Sullivan, 1994) using Goldwave Version 5, and a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of −3 dB then was applied to each sentence. This SNR was identified with pilot testing to not produce ceiling or floor effects. An SNR of −3 dB has also been used in other studies investigating intelligibility of clear speech (Ferguson & Kewley-Port, 2002; Maniwa, Jongman, & Wade, 2008). Using procedures similar to Sussman and Tjaden (2012), stimuli were presented to individual listeners at 75 dB SPL through headphones (SONY, MDR V300) in a double-walled audiometric booth. The task took approximately 90 min with breaks and was self-paced.

Fifty listeners scaled intelligibility and 50 listeners scaled speech severity using the 150 mm, computerized, continuous visual analog scale also used in Sussman and Tjaden (2012). Although orthographic transcription is frequently used in studies of intelligibility, scaling tasks also have been widely used to quantify intelligibility in dysarthria, including the type of continuous visual analog scale used in our study (e.g., Bunton, Kent, Kent, & Duffy, 2001; Kim, Kent, & Weismer, 2011; Van Nuffelen et al., 2010; Weismer, Laures, Jeng, Kent, & Kent, 2000; Yunusova, Weismer, Kent, & Rusche, 2005).

The continuous 150-mm scale contained no tick marks and was oriented vertically on a computer monitor. Listeners judged each sentence without knowledge of the speaker’s neurological diagnosis. Written instructions for the intelligibility task directed listeners to judge how well a sentence was understood with scale endpoints labeled understand everything to cannot understand anything. Listeners who judged speech severity were instructed as follows:

-

Rate the overall severity of sentences paying attention to the following:

Voice (quality—breathy, noisy, gurgly, high pitch, too low pitch, or sounds normal)

Resonance (too nasal, not nasal in the right places, sounds like they have a cold, or sounds normal)

Articulatory precision (some sounds are crisp or slurred or somewhere in between or sounds normal)

Speech rhythm (the timing of speech doesn’t sound right or sounds normal).

Pay attention to overall speech naturalness and prosody (melody and timing of speech). Do not focus on the speaker’s intelligibility or how understandable is each sentence.

After hearing a sentence once, listeners used the computer mouse to click anywhere along the scale to indicate their response. Following completion of the experiment, software converted responses to numerical values ranging from 0 (i.e., understand everything or no impairment) to 1.0 (i.e., cannot understand anything or severely impaired).

Procedures were the same for intelligibility and scaled severity tasks. Sentences for all speakers and conditions first were pooled and then divided into 10 carefully constructed sets. Five listeners were assigned to judge each set. Sentence sets contained one sentence produced by each of the 78 talkers in each condition. Sentence sets further included similar numbers (N = 15 or 16) of each of the 25 Harvard sentences in all conditions. Each listener also judged a random selection of 10% of sentences twice to ascertain intra-judge reliability. To familiarize listeners with the stimuli which repeated, listeners first heard all Harvard sentences produced by one healthy male and female speaker who were not part of the study. Then, listeners practiced using the computer interface and were exposed to sentences mixed with babble by scaling intelligibility (or speech severity) for six sentences produced by speakers who were not part of the current study.

Data Analysis

Dependent measures were characterized using both descriptive (i.e., mean [M], standard deviation [SD]) and parametric statistics. Using SAS Version 9.1.3 statistical software, a multivariate linear model was fit to each dependent measure in this repeated measures design. Each measure was fit as a function of group (control, MS, PD), condition (habitual, loud, slow, and clear) and a Group × Condition interaction. The within-subject covariance matrix was assumed to be unstructured (see Brown & Prescott, 1999, for details on this approach). A variable representing speaker sex was included in each model to account for different proportions of male and female speakers among groups. Order of nonhabitual conditions also was included as a blocking variable in models fit to perceptual metrics. Standard diagnostic plots were used to assess model fit. All tests were two-sided and were evaluated at a .05 nominal significance level. Once a model was fit, specific linear, follow-up contrasts were performed based on the estimated model parameters. Follow-up contrasts were made in conjunction with a Bonferroni correction for multiple tests. The p values for follow-up contrasts reported in the Results are Bonferroni-corrected p values. Exact p values are reported when not referring to multiple significant contrasts. Finally, relationships among perceptual measures were assessed using correlation and regression analysis.

Results

Acoustic Measures of Articulatory Rate and SPL

Descriptive statistics in Table 2 indicate that all speaker groups increased mean SPL for the loud and clear conditions relative to the habitual condition. The average magnitude of the increase across groups was 7–10 dB for the loud condition and 3–4 dB for the clear condition. Statistical analyses of SPL further indicated a significant effect of group, F(2, 73) = 3.52, p = .035, condition, F(3, 73) = 236.02, p < .001, and a Group × Condition interaction, F(6, 73) = 2.64, p = .023. Follow-up contrast tests indicated that within each speaker group, all contrasts were significant (p < .001), with the exception of the habitual–slow contrast. Descriptive statistics in Table 3 suggest a reduced rate for the slow and clear conditions relative to the habitual condition. The average magnitude of the rate reduction across groups was 49%–29% for the slow condition and 19%–37% for the clear condition. Mean articulation rates for the loud condition in Table 3 are more similar to those for the habitual condition, however, especially for the PD group. The statistical analysis indicated significant effects of group, F(2, 74) = 9.78, p < .001, condition, F(3, 74) = 158.60, p < .001, and a Group × Condition interaction, F(6, 74) = 6.22, p < .001. Follow-up contrast tests further indicated that all contrasts were significant (p < .001) for each of the three speaker groups, with the exception of the habitual–loud contrast for the PD group.

Table 2.

Sound pressure level.

| Group | Habitual | Clear | Loud | Slow |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 73 (2.7) | 77 (4.5) | 83 (4.0) | 73 (4.0) |

| 68–81 | 70–90 | 75–94 | 66–81 | |

| MS | 72 (3.0) | 75 (4.4) | 80 (3.6) | 72 (4.7) |

| 66–80 | 68–87 | 73–87 | 64–85 | |

| PD | 72 (3.2) | 75 (4.0) | 79 (4.0) | 72 (4.6) |

| 66–79 | 69–82 | 70–85 | 62–78 |

Note. Mean sound pressure level (in dB) and standard deviations (SDs) are reported in the first row for each speaker group. The corresponding range is reported in the row directly below means and SDs.

Table 3.

Articulation rate.

| Group | Habitual | Clear | Loud | Slow |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 3.7 (.44) | 2.3 (.32) | 3.2 (.46) | 1.9 (.48) |

| 2.9–4.7 | 1.7–3.0 | 2.2–4.0 | 1.1–2.8 | |

| MS | 3.6 (.60) | 2.7 (.63) | 3.3 (.69) | 2.4 (.60) |

| 1.8–4.7 | 1.5–4.0 | 1.7–5.2 | 1.0–3.7 | |

| PD | 4.1 (.58) | 3.3 (.75) | 4.0 (.71) | 2.9 (.75) |

| 2.8–5.0 | 1.6–4.9 | 2.7–5.4 | 1.7–4.8 |

Note. Mean articulatory rates and SDs are reported in syllables per second for all speaker groups and conditions. The corresponding range is reported in the row directly below means and SDs.

In summary, all groups significantly reduced articulatory rate in the Slow condition relative to the Habitual, Clear, and Loud conditions but maintained mean SPL at habitual-levels. All groups also significantly increased mean SPL in the Loud condition versus Habitual, Clear, and Slow conditions. The MS and control groups, but not the PD group, also slowed articulation rate in the Loud versus Habitual condition. Finally, for the Clear condition, all groups increased mean SPL and reduced mean articulatory rate relative to Habitual, with the magnitude of the adjustments being less than for the Loud and Slow conditions. Thus, the Clear, Loud, and Slow conditions were characterized by differences in production from each other as well as the Habitual condition.

Intelligibility and Speech Severity: Listener Reliability

Intrajudge reliability

For intelligibility, Pearson product correlation coefficients for the first and second presentation of sentences ranged from .60 to .88 across the 50 listeners, with a mean of .71 (SD = .07). For speech severity, correlations ranged from .60 to .88 across the 50 listeners, with a mean of .73 (SD = .07). All correlations were significant (p < .001). However, to be conservative, listeners with intrajudge coefficients less than r = .70 were excluded from further consideration. All remaining analyses reflect judgments of intelligibility for 29 listeners (M intra-judge r = .76; SD = .05; range = .70–.88) and judgments of Scaled Severity for 35 listeners (M intrajudge r = .77; SD = .02; range = .70–.88).

Interjudge reliability

Interjudge reliability was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). Following Neel (2009), ICCs were calculated separately for all sentence sets using a two-way mixed-effects model to determine the overall consistency of ratings among listeners. As in other dysarthria studies that use scaling tasks to assess intelligibility (i.e., Kim et al., 2011; Neel, 2009; Weismer et al., 2001, 2012; Yunusova et al., 2005), aggregate listener performance was of interest. Average ICC metrics, therefore, should be considered as the primary measure of agreement among listeners, although single measure ICCs are provided for completeness. For intelligibility, average ICCs ranged from .63 to .91 (M = .83, SD = .09) and single measure ICCs ranged from .46 to .71 (M = .61, SD =.07). For speech severity, average ICCs ranged from .76 to .86 (M = .83, SD = .04) and single measure ICCs ranged from .49 to .66 (M = .57, SD = .05). All ICCs were statistically significant (p < .001).

A second ICC measure was obtained to further characterize interjudge reliability for the pooled group of 29 intelligibility listeners and the pooled group of 35 speech severity listeners. The one-way random ICC model is recommended for studies using large data sets in which an individual judge rates a subset of stimuli. In this manner, the model does not separate listeners and stimuli and provides a more stringent estimate of interjudge reliability than the two-way mixed-effects model (i.e., smallest ICC). The average, one-way random model ICC for intelligibility was .96 (confidence interval [CI] [.948, .951]) and for scaled severity was .96 (CI [.958, .968]). Single ICCs were .42 and .43 for intelligibility and scaled severity, respectively. These ICCs also were statistically significant (p < .001).

Relationships Between Perceptual Measures

SIT scores and intelligibility judgments in the habitual condition were significantly correlated when data was pooled across all 78 speakers (Pearson r = −.68, p < .001, two-tailed test). Measures also were significantly correlated for both the MS (Pearson r = −.63, p < .001, two-tailed test) and PD groups (Pearson r = −.73, p = .001, two-tailed test), but not for controls.

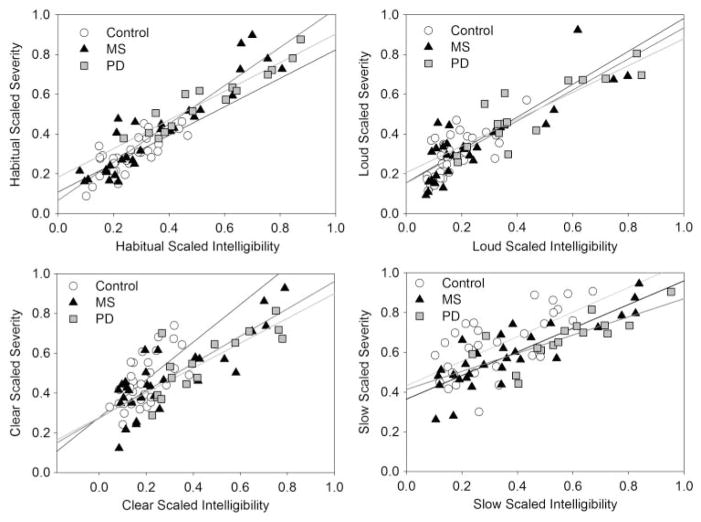

Results of the regression analyses relating intelligibility and speech severity are reported in Table 4. Boldface values indicate nonhabitual conditions for which metrics were less strongly associated versus the habitual condition, as determined using the procedure for comparing correlation coefficients outlined by Cohen and Cohen (1983). Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between scaled intelligibility and speech severity within speaker groups and conditions. Each symbol reflects scale values averaged across Harvard sentences for an individual speaker. Figure 1 shows that speakers judged to have better intelligibility also were judged to have better speech severity (i.e., less impaired). Within conditions, the relationship between intelligibility and speech severity was more robust for the MS and PD groups versus controls. In addition, the strongest relationship between scaled intelligibility and scaled speech severity was observed for the habitual condition. For the MS and PD groups, the strength of association between perceptual metrics also was significantly weaker in the clear versus habitual conditions. Similar results held for the PD group’s slow condition.

Table 4.

Results of the within-condition regression analyses relating scaled intelligibility and speech severity.

| Group | Condition | F | p | Adjusted r2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Habitual | F(1, 31) = 37.995 | <.001 | .54 |

| Clear | F(1, 31) = 20.058 | <.001 | .38 | |

| Loud | F(1, 31) = 23.640 | <.001 | .42 | |

| Slow | F(1, 31) = 23.027 | <.001 | .42 | |

| MS | Habitual | F(1, 29) = 167.709 | <.001 | .85 |

| Clear | F(1, 29) = 57.752 | <.001 | .66 | |

| Loud | F(1, 28) = 67.591 | <.001 | .70 | |

| Slow | F(1, 29) = 68.549 | <.001 | .70 | |

| PD | Habitual | F(1, 15) = 122.690 | <.001 | .89 |

| Clear | F(1, 15) = 26.286 | <.001 | .63 | |

| Loud | F(1, 15) = 41.682 | <.001 | .73 | |

| Slow | F(1, 15) = 19.014 | <.001 | .55 |

Note. Boldface indicates nonhabitual conditions for which the strength of the relationship between intelligibility and speech severity was significantly weaker versus habitual (p < .05, one-tailed).

Figure 1.

Scatter plots relating mean scaled intelligibility and speech severity are reported. Linear regression functions have been fit to the data separately for each group and condition. Each symbol corresponds to an individual speaker.

Group Findings: Intelligibility and Speech Severity

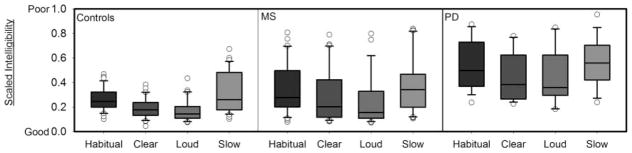

Results for intelligibility are shown in Figure 2. Scale values closer to 0 indicate relatively better intelligibility, whereas scale values closer to 1.0 indicate relatively poorer intelligibility. On average, intelligibility for the PD group was best (i.e., scale values closest to 0) in the clear condition (M = .440, SD = .200), followed by loud (M = .441, SD = .217), habitual (M = .540, SD = .197), and slow (M = .565, SD = .188). A similar pattern was observed when speakers with a history of LSVT were excluded (clear M = .415, loud M = .423, habitual M = .517, slow M = .557). Figure 1 also suggests that scaled intelligibility for the MS group was best in the loud condition (M = .250, SD = .202), followed by clear (M = .287, SD = .215), habitual (M = .356, SD = .209), and slow (M = .367, SD = .225). Scaled intelligibility for the control group also was best for the loud condition (M = .171, SD = .087), followed by clear (M = .189, SD = .085), habitual (M = .258, SD = .094), and slow (M = .329, SD = .166).

Figure 2.

Scaled intelligibility measures are reported as a function of group and condition.

Statistical analysis of intelligibility indicated significant effects of group, F(2, 71) = 12.92, p < .001, and condition, F(3, 71) = 35.78, p < .001. Follow-up contrast tests indicated that the PD group had poorer intelligibility compared with both control (p < .001) and MS groups (p = .004). The MS-control contrast only approached significance (p = .072). Within groups, scaled intelligibility for the clear and loud conditions was significantly better than habitual (p ≤ .002), but clear and loud did not differ. Intelligibility for the MS and PD groups’ habitual and slow conditions also was not significantly different. For controls, however, intelligibility in the slow condition was poorer versus habitual (p = .008). Finally, for all groups, intelligibility for the slow condition was poorer versus loud and clear (p ≤ .009).

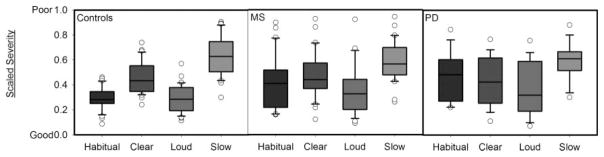

Results for speech severity are shown in Figure 3. Scale values closer to 0 indicate relatively better scaled speech severity, whereas scale values closer to 1.0 indicate relatively poorer scaled speech severity. Speech severity for the PD group was best in the loud condition (M = .503, SD = .169), followed by clear (M = .551, SD = .155), habitual (M = .572, SD = .150), and slow (M = .671, SD = .113). The same pattern was observed when speakers with a history of LSVT were excluded (i.e., loud M = .469, clear M = .527, habitual M = .544, slow M = .659). Relatedly, speech severity for the MS group was best in the loud condition (M = .348, SD = .180), followed by habitual (M = .409, SD = .217), clear (M = .471, SD = .180), and slow (M = .583, SD = .159). Finally, speech severity for the control group was best in the habitual condition (M = .292, SD = .090), followed by loud (M = .295, SD = .108), clear (M = .456, SD = .127), and low (M = .635, SD = .156).

Figure 3.

Scaled speech severity measures are reported as a function of group and condition.

The statistical analysis for speech severity indicated significant effects of group, F(2, 71) = 8.80, p = .0004, condition, F(3, 71) = 76.87, p < .0001, and a Group × Condition interaction, F(6, 71) = 7.08, p < .0001. Follow-up contrast tests indicated poorer speech severity for the PD group versus both the MS (p = .01) and control groups (p < .001). Within-group, follow-up contrasts for the MS and control groups further indicated a significant difference for the majority of contrasts (p < .001), with the exception of the habitual–loud contrast for both groups and the clear–habitual contrast for the MS group. Follow-up contrasts for the PD group also indicated significant differences for the clear–slow (p = .002), habitual–loud (p = .039), and loud–slow contrasts (p < .001).

To summarize, although scaled intelligibility improved in the loud and clear conditions for the PD and MS groups, speech severity was either maintained at habitual levels or also was improved relative to habitual. The PD group further maintained intelligibility and speech severity at habitual levels in the Slow condition. Relatedly, the MS group maintained intelligibility at Habitual levels in the Slow condition, but Speech Severity was significantly poorer than Habitual. Finally, for controls, intelligibility in the Clear and Loud conditions was significantly improved above Habitual, while Speech Severity was either maintained at Habitual levels or was significantly poorer. Both intelligibility and Speech Severity were significantly poorer than Habitual for controls in the Slow condition.

Individual Speaker Trends: Intelligibility and Speech Severity

Individual speaker data were examined to determine whether descriptive trends for the MS and PD groups held for individual talkers. Nine PD speakers (i.e., five females, four males) improved intelligibility in the clear and loud conditions versus habitual and slow, including three of the four speakers with a history of LSVT. No predominant pattern emerged for the remaining speakers, although intelligibility was best in the clear condition for three speakers and was best in the loud condition for two speakers. Sixteen speakers with MS (i.e., 11 females, five males) followed the overall group trend of improved intelligibility in both the clear and loud conditions versus habitual and slow. For 10 of the remaining speakers, the clear, loud, or both conditions improved intelligibility relative to habitual. Thus, descriptive group results for intelligibility generally held for individual talkers with PD or MS.

Half of the PD group (i.e., four females, four males) had the poorest speech severity in the slow condition and the best speech severity (i.e., least impaired) in the loud condition, with intermediate scale values for the clear and habitual conditions, including two of the four speakers with a history of LSVT. Six of the eight remaining speakers (i.e., three female, three males) also had the poorest speech severity in the slow condition but were judged to have the best speech severity (i.e., least impaired) in the clear or habitual conditions. This subset included one speaker with a history of LSVT. Finally, 16 speakers with MS (i.e., 12 females, four males) had the poorest speech severity in the slow condition and the best speech severity (i.e., least impaired) in the loud condition, with intermediate judgments for the clear and slow conditions. Six other speakers also had the poorest speech severity in the slow condition but had the best speech severity (i.e., least impaired) in the habitual or clear conditions. We found no discernible pattern for the remaining speakers. Thus, although the vast majority of speakers with PD or MS followed the descriptive group trend of having the poorest speech severity in the slow conditions, individual speaker trends for other conditions were variable.

Discussion

Scaled Intelligibility and Speech Severity: Impact of Conditions

Both the Clear and Loud conditions improved sentence intelligibility to a similar extent for all speaker groups (see Figure 1). Although methodological differences prevent direct comparison to other studies, findings are in broad agreement with studies reporting improved intelligibility for stimulated Clear speech as well as speech produced at an increased vocal intensity (e.g., Beukelman et al., 2002; Neel, 2009; Smiljanić & Bradlow, 2009; Tjaden & Wilding, 2004). The finding of improved intelligibility in the clear condition for the PD and MS groups is particularly important from the standpoint of increasing the scientific evidence base for this global therapy technique because only one published study based on eight speakers with TBI has reported the impact of clear speech on intelligibility in dysarthria (Beukelman et al., 2002). Whether certain cues for eliciting clear or loud speech serve to maximize intelligibility is worthy of study in the future, perhaps especially in light of research suggesting that the cue for stimulating an increased vocal intensity affects the nature of the speech production adjustments in PD (Darling & Huber, 2011). Clear speech instructions also have been shown to impact the magnitude of acoustic adjustments made by neurologically healthy talkers (Lam et al., 2012), as well as the magnitude of the improvement in intelligibility (Lam & Tjaden, 2013).

On average, intelligibility for the clear and loud conditions improved by .07–.11 scale values on a continuous scale with numerical values ranging from 0 to 1.0 (see descriptive statistics in the Results section). This translates into a 7%–11% improvement in scaled sentence intelligibility, which likely would be meaningful in a challenging perceptual environment like the multitalker babble used in our study (e.g., Van Nuffelen et al., 2010). Relatedly, speech severity for the PD group improved on average by .07 scale values or roughly 7% in the loud condition and was at least maintained at habitual levels in the loud condition by speakers with MS. Speech severity for the MS and PD groups also was maintained in the clear condition but was reduced by .16 scale values, on average, for control talkers. Thus, for the MS and PD groups, the clear and loud conditions maximized intelligibility in multitalker babble, and these conditions did not negatively impact scaled speech severity. Speakers with MS and PD in this study had mostly mild speech impairment, and this may help to explain why the improvements in intelligibility for the clear and loud conditions were not even greater. Future studies are needed to determine whether results extend to individuals with more severe dysarthria. Nonetheless, despite the fact that more attention has been devoted to studying speakers with moderate to severely reduced intelligibility, even mild dysarthria can have serious negative consequences for participation in real world activities such as employment, which is an issue of tremendous concern in the MS population (Yorkston et al., 2010).

The possibility that LSVT history for some PD speakers affected the pattern of results for the PD group as a whole also deserves comment. It might be speculated that LSVT primed speakers to adjust their speech in a way that enhanced intelligibility in the loud and clear conditions, both of which included directions regarding loudness. This scenario is improbable for a variety of reasons. First, findings for the PD group were identical to those for the MS and control groups, who had not received LSVT. Second, the same descriptive pattern of results for scaled intelligibility (and speech severity) was found when the four speakers with a history of LSVT were excluded. Moreover, the speaker attending bimonthly LSVT refresher sessions had the best scaled intelligibility in the slow condition and the poorest intelligibility in the clear condition. Finally, two individuals who had received LSVT had completed the treatment more than 2 years before participating in our study.

Voluntary rate reduction (i.e., speaking slower on demand) did not improve scaled sentence intelligibility for the current speakers with MS or PD. The slow condition was associated with a substantial lengthening of speech durations (see Table 3). The MS group reduced mean articulation rate by 33% in the slow condition, whereas the PD group reduced mean articulation rate by 29%, although speakers in both groups as well as control talkers varied substantially in the magnitude of rate change. The failure of the slow condition to enhance intelligibility therefore is not attributable to speakers being unable to voluntarily slow rate, as reported in the Van Nuffelen et al. (2010) study.

Rate reduction, as elicited in this study by encouraging the stretching out of speech, is intended to enhance segmental articulatory behavior. That single word and SIT scores in Table 1 suggest fairly well-preserved segmental articulation for speakers with MS and PD may explain why the slow condition did not enhance scaled sentence intelligibility. It is interesting that descriptive statistics for the majority of individuals with MS and PD indicated that intelligibility was poorer for the slow versus habitual conditions. A slower-than-normal articulation rate is associated with prosodic adjustments potentially detrimental to intelligibility, including reduced phrase-level fundamental frequency range (Tjaden & Wilding, 2011). It seems plausible that these types of prosodic changes could have been a barrier to improved intelligibility in the slow condition. Future studies investigating rate control are needed to investigate the contribution of these types of prosodic changes to intelligibility.

Relationship Between Perceptual Metrics

The significant correlation between SIT scores for disordered speaker groups and scaled intelligibility for the habitual condition suggests that the scaling task was indeed tapping into the extent to which listeners recovered the acoustic signal in the context of multitalker babble. The finding that SIT scores for the control group were not significantly correlated with scaled intelligibility for the habitual condition may be a statistical artifact of the compressed range of data for these speakers. The different results for controls versus disordered speaker groups also may be additional evidence that intelligibility of normal speech and dysarthria are affected differently by background noise (see poster of McAuliffe, Good, O’Beirne, & LaPointe, 2008). Regardless, results indicate that scaled intelligibility (i.e., how well speech is understood) of neurologically normal speech in multitalker babble does not map onto the accuracy with which sentences in quiet are orthographically transcribed.

Contemporary graduate-level motor speech texts indicate that maximizing intelligibility and naturalness is an overall goal of dysarthria treatment for individuals with mild to moderate involvement (Yorkston et al., 2010). Paradoxically, it is unclear whether perceptual constructs of intelligibility, naturalness, acceptability, severity, and so forth are interpreted similarly by listeners (Dagenais et al., 1999, 2006; Hanson et al., 2004; Southwood & Weismer, 1993; Sussman & Tjaden, 2012; Weismer et al., 2001; Whitehill et al., 2004). Similarly, Weismer et al.’s (2001) findings for habitual speech produced by talkers with more severe dysarthria showed a strong relationship between scaled intelligibility and speech severity (see Table 4). Thus, it appears that listeners interpret the operationally defined perceptual construct of speech severity in the same way as intelligibility or vice versa, and the value of obtaining both measures is questionable. Intelligibility or understandability might be preferred on the basis of transparency and slightly better listener reliability. However, the strength of the association between the two measures was significantly reduced in the clear condition versus habitual for both the MS and PD groups as well as for the slow condition of the PD group. There also was an upward shift of the y intercept for regression functions in the nonhabitual conditions (see Figure 1). Thus, our findings indicate that for a given scaled estimate of intelligibility, the corresponding judgment of speech severity was poorer in the clear, loud, and slow conditions. In addition, speech severity was maintained at habitual levels in the clear and loud conditions for the MS group, but intelligibility was significantly improved in these conditions. Descriptive statistics further indicated that a slower-than-normal rate was detrimental to speech severity, despite maintained intelligibility. Taken together, the implication is that these two perceptual constructs hold potential for providing at least some complementary information concerning the perceptual consequences of global dysarthria treatment techniques.

What Explains the Variations in Scaled Intelligibility and Speech Severity

Future production studies are needed to determine the source of the variations in intelligibility or speech severity. However, the topic warrants at least some consideration here. Improvements in intelligibility and speech severity in the loud and clear conditions were not solely caused by differences in audibility because sentences were equated for peak amplitude prior to mixing with multitalker babble. Rather, we hypothesize that adjustments in segmental articulation, voice, and prosody in the loud and clear conditions contributed to the varied perceptual outcomes. For example, enhanced vowel and consonant acoustic contrasts, a wider dynamic pitch range, and phonatory changes in spectral tilt could have contributed to variations in perceptual measures (e.g., Neel, 2009; Smiljanić & Bradlow, 2009; Tjaden & Wilding, 2004). If the locus of treatment focus determines the magnitude of speech production changes, we further speculate that the magnitude of adjustments in segmental articulatory behavior would be greater for the clear versus the loud condition, given the focus of clear speech on exaggerated articulation, whereas the magnitude of respiratory–phonatory adjustments would be greater in the loud condition, given the focus on increasing respiratory–phonatory effort.

Caveats and Conclusions

Several factors should be kept in mind when interpreting our findings. First, different instructions for eliciting the nonhabitual conditions may have yielded different findings. It also might be speculated that the definition of intelligibility had some bearing on the results. Other dysarthria studies using scaling tasks to measure intelligibility have defined intelligibility as the “ease with which speech is understood,” which may tap into the cognitive effort required by the listener to recover the speaker’s intended message rather than the degree to which the message was understood. Additional studies are needed to investigate whether the definition of intelligibility affects outcomes in studies using scaling tasks. Given dysarthria studies reporting a strong relationship between intelligibility measures for a variety of speech materials (i.e., words, phrases, sentences) and tasks (i.e., forced-choice word identification, transcription, scaling) as well as the significant correlation between SIT scores and scaled habitual intelligibility for the current MS and PD groups, however, we speculate that the precise definition of intelligibility would have minimal impact on overall outcomes (e.g., Bunton et al., 2001; Weismer et al., 2001; Yunusova et al., 2005).

Perceptual judgments also were obtained in the presence of multitalker babble, which is arguably an ecologically valid perceptual environment. The importance of investigating speech intelligibility measurement in dysarthria in adverse listening conditions further was noted by Yorkston et al. (2007). Although the topic has been the focus of studies of neurologically normal speech for some time (e.g., Binns & Culling, 2007; Festen & Plomp, 1990; Plomp & Mimpen, 1979), intelligibility in background noise is only beginning to be reported in published dysarthria studies (Bunton, 2006; Cannito et al., 2012). Unpublished, preliminary data for three speakers with dysarthria suggests that background noise affects intelligibility in dysarthria in a slightly different way than for neurologically normal talkers and may even differ depending on the perceptual characteristics of the dysarthria (McAuliffe et al., 2008; McAuliffe, Schaefer, O’Beirne, & LaPointe, 2009). Extension of our results to other populations or perceptual environments therefore should be made with the appropriate degree of caution.

Another variable to consider was the elicitation of habitual speech first out of all conditions. Although the order of elicitation for nonhabitual conditions was randomized across speakers, the habitual condition was always recorded first. Thus, it might be suggested that improved perceptual judgments for nonhabitual conditions could partially reflect that speakers had greater familiarity with the speech materials. That the slow condition was always recorded after the habitual condition but was associated with no improvement in intelligibility regarding habitual is an argument against such an interpretation. Future studies could randomize recording order for the habitual condition. However, this introduces another level of difficulty. It seems likely that recording nonhabitual conditions before habitual could influence or bias an individual’s typical or conversational speech style. This is speculation, however, and might be addressed empirically in a separate study.

Last, listener reliability also deserves consideration. Although our metrics of listener reliability may seem modest, measures are consistent with or in some instances are better than other dysarthria studies using scaling tasks, bearing in mind the large number of listeners and speakers in this investigation. For example, Van Nuffelen, De Bodt, Wuyts, and Van de Heyning (2009) reported an intraclass correlation of .85 for five speech–language pathologists’ judgments of intelligibility for a paragraph read by speakers with dysarthria under varied rate manipulation techniques. Intra-judge reliability was not reported. Similarly, Neel (2009) reported an intraclass correlation of .92 for judgments of scaled sentence intelligibility made by 11 student judges for talkers with PD. For intrajudge reliability, Pearson correlations ranged from .42 to .52. Finally, Kim and Kuo (2012) reported intraclass correlation coefficients ranging from .54 to .69 for judgments of scaled intelligibility made by 60 student listeners for sentences produced by individuals with a variety of dysarthrias as well as healthy talkers. Even studies using transcription report variation both within and across listeners in the consistency or reliability of judgments (e.g., Bunton et al., 2001; Lam & Tjaden, 2013; McHenry, 2011). The source of listener variation in judgments of intelligibility remains a topic of ongoing study (see McHenry, 2011).

Overall, results showed that listeners’ impressions of intelligibility in multitalker babble improved for speech of individuals with PD and MS produced in loud or clear conditions. The slow condition not only did not improve intelligibility but also in many instances yielded poorer speech severity compared with all other conditions. Although results pertain to sentences produced by a relatively modest number of speakers with MS or PD, findings suggest that even individuals with mild dysarthria may derive perceptual benefit from the global dysarthria therapy techniques of clear and loud speech. Further research is warranted to determine whether these perceptual benefits can be maintained over time and in lengthier connected speech tasks. In sum, clear speech and an increased vocal intensity appear to have similar beneficial effects on scaled intelligibility and also are not detrimental to the closely related perceptual construct of speech severity.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this study were presented at the Sixth Motor Control Conference, Groningen, the Netherlands, June 2011. Research supported by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders grant R01 DC004689. We thank Jennifer Lam and Adrienne Ricchiazzi for assistance with manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have declared that no competing interests existed at the time of publication.

References

- Beukelman DR, Fager S, Ullman C, Hanson E, Logemann J. The impact of speech supplementation and clear speech on the intelligibility and speaking rate of people with traumatic brain injury. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology. 2002;10:237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Binns C, Culling JF. The role of fundamental frequency contours in the perception of speech against interfering speech. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2007;122:1765–1776. doi: 10.1121/1.2751394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown H, Prescott R. Applied mixed models in medicine. West Sussex, England: Wiley; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bunton K. Fundamental frequency as a perceptual cue for vowel identification in speakers with Parkinson’s disease. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica. 2006;58:323–339. doi: 10.1159/000094567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunton K, Kent RD, Kent JF, Duffy JR. The effects of flattening fundamental frequency contours on sentence intelligibility in speakers with dysarthria. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics. 2001;15:181–193. [Google Scholar]

- Cannito MP, Suiter DM, Beverly D, Chorna L, Wolf T, Pfeiffer RM. Sentence intelligibility before and after voice treatment in speakers with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Voice. 2012;26:214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Dagenais P, Brown G, Moore R. Speech rate effects upon intelligibility and acceptability of dysarthric speech. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics. 2006;20:141–148. doi: 10.1080/02699200400026843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagenais P, Watts C, Turnage L, Kennedy S. Intelligibility and acceptability of moderately dysarthric speech by three types of listeners. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology. 1999;7:91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Darling M, Huber J. Changes to articulatory kinematics in response to loudness cues in individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2011;54:1247–1257. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2011/10-0024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy J. Motor speech disorders: Substrates, differential diagnosis, and management. 3. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson S, Kewley-Port D. Vowel intelligibility in clear and conversational speech for normal-hearing and hearing impaired listeners. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2002;112:259–271. doi: 10.1121/1.1482078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festen JM, Plomp R. Effects of fluctuating noise and interfering speech on the speech-reception threshold for impaired and normal hearing. The Journal of the Acoustic Society of America. 1990;88:1725–1736. doi: 10.1121/1.400247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank T, Craig CH. Comparison of the auditec and rintelmann recordings of the NU-6. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1984;49:267–271. doi: 10.1044/jshd.4903.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen VL, Yorkston KM, Minifie FD. Effects of temporal alterations on speech intelligibility in Parkinsonian dysarthria. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1994;37:244–253. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3702.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson EK, Beukelman DR, Fager S, Ullman C. Listener attitudes toward speech supplementation strategies used by speakers with dysarthria. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology. 2004;12:161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Hustad K. Effects of speech stimuli and dysarthria severity on intelligibility scores and listener confidence ratings for speakers with cerebral palsy. Folia Phoniatrica. 2007;59:306–317. doi: 10.1159/000108337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hustad KC, Weismer G. Interventions to improve intelligibility and communicative success for speakers with dysarthria. In: Weismer G, editor. Motor speech disorders. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing; 2007. pp. 261–303. [Google Scholar]

- Kent RD, Weismer G, Kent JF, Rosenbek JC. Toward phonetic intelligibility testing in dysarthria. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1989;54:482–499. doi: 10.1044/jshd.5404.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Kent RD, Weismer G. An acoustic study of the relationships among neurologic disease, dysarthria type, and severity of dysarthria. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2011;54:417–429. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2010/10-0020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Kuo C. Effect level of presentation to listeners on scaled speech intelligibility of speakers with dysarthria. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica. 2012;64:26–33. doi: 10.1159/000328642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam J, Tjaden K. Intelligibility of clear speech: Effect of instruction. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2013;56:1429–1440. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2013/12-0335). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam J, Tjaden K, Wilding G. Acoustics of clear speech: Effect of instruction. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2012;55:1807–1821. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388. (2012/11-0154) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniwa K, Jongman A, Wade T. Perception of clear fricatives by normal-hearing and simulated hearing-impaired listeners. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2008;123:1114–1125. doi: 10.1121/1.2821966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAuliffe MJ, Good PV, O’Beirne GA, LaPointe LL. Influence of auditory distraction upon intelligibility ratings in dysarthria. Poster presented at the 14th Biennial Conference on Motor Speech: Motor Speech Disorders and Speech Motor Control; Monterey, CA. 2008. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- McAuliffe MJ, Schaefer M, O’Beirne GA, LaPointe LL. Effect of noise upon the perception of speech intelligibility in dysarthria; Poster presented at the American Speech-Language–Hearing Association Convention; New Orleans, LA. 2009. Nov, Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10092/3410. [Google Scholar]

- McHenry MA. The effect of pacing strategies on the variability of speech movement sequences in dysarthria. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2003;46:702–710. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2003/055). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHenry M. An exploration of listener variability in intelligibility judgments. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2011;20:119–123. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2010/10-0059). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRae PA, Tjaden K, Schoonings B. Acoustic and perceptual consequences of articulatory rate change in Parkinson disease. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2002;45:35–50. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milenkovic P. TF32 [Computer program] Madison: University of Wisconsin—Madison; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Molloy D. Standardized Mini-Mental State Examination. Troy, NY: New Grange Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Neel A. Effects of loud and amplified speech on sentence and word intelligibility in Parkinson disease. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2009;52:1021–1033. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2008/08-0119). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson M, Soli S, Sullivan J. Development of the hearing in noise test for the measurement of speech reception thresholds in quiet and in noise. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1994;95:1085–1099. doi: 10.1121/1.408469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomp R, Mimpen AM. Speech-reception thresholds for sentences as a function of age and noise level. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1979;66:1333–1342. doi: 10.1121/1.383554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramig LO. The role of phonation in speech intelligibility: A review and preliminary data from patients with Parkinson’s disease. In: Kent RD, editor. Intelligibility in speech disorders: Theory, measurement, and management. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: John Benjamins; 1992. pp. 119–156. [Google Scholar]

- Ramig LO, Bonitati CM, Lemke JH, Horii Y. Voice treatment for patients with Parkinson disease: Development of an approach and preliminary efficacy data. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology. 1994;2:191–209. [Google Scholar]

- Ramig L, Countryman S, Thompson L, Horii Y. A comparison of two forms of intensive speech treatment for Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1995;38:1232–1251. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3806.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapir S, Ramig LO, Fox CM. Intensive voice treatment in Parkinson’s disease: Lee Silverman Voice Treatment. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 2011;11:815–830. doi: 10.1586/ern.11.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapir S, Spielman J, Ramig L, Story B, Fox C. Effects of intensive voice treatment (the Lee Silverman Voice Treatment [LSVT]) on vowel articulation in dysarthric individuals with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: Acoustic and perceptual findings. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2007;50:899–912. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2007/064). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smiljanić R, Bradlow AR. Speaking and hearing clearly: Talker and listener factors in speaking style changes. Language and Linguistics Compass. 2009;3:236–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-818X.2008.00112.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southwood M, Weismer G. Listener judgments of the bizarreness, acceptability, naturalness and normalcy of dysarthria associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology. 1993;1:151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman J, Tjaden K. Perceptual measures of speech from individuals with Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis: Intelligibility and beyond. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2012;55:1208–1219. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2011/11-0048). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. IEEE recommended practice for speech quality measurements. IEEE Transactions on Audio and Electroacoustics. 1969;17:225–246. [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden K, Lam J, Wilding G. Vowel acoustics in Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis: Comparison of clear, loud and slow speaking conditions. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2013;56:1485–1502. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2013/12-0259). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden K, Wilding G. Rate and loudness manipulations in dysarthria: Acoustic and perceptual findings. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2004;47:766–783. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/058). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden K, Wilding G. The impact of rate reduction and increased loudness on fundamental frequency characteristics in dysarthria. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica. 2011;63:178–186. doi: 10.1159/000316315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner GS, Weismer G. Characteristics of speaking rate in the dysarthria associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1993;36:1134–1144. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3606.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchanski RM. Clear speech. In: Pisoni DB, Remez R, editors. The handbook of speech perception. Malden, MA: Blackwell; 2005. pp. 207–235. [Google Scholar]

- Van Nuffelen G, De Bodt M, Vanderwegen J, Van de Heyning P, Wuyts F. Effect of rate control on speech production and intelligibility in dysarthria. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica. 2010;62:110–119. doi: 10.1159/000287209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Nuffelen G, De Bodt M, Wuyts F, Van de Heyning P. The effect of rate control on speech rate and intelligibility in dysarthria. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica. 2009;61:69–75. doi: 10.1159/000208805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weismer G. Speech intelligibility. In: Ball MJ, Perkins MR, Muller N, Howard S, editors. The handbook of clinical linguistics. Oxford, England: Blackwell; 2008. pp. 568–582. [Google Scholar]

- Weismer G, Jeng JY, Laures J, Kent RD, Kent JF. Acoustic and intelligibility characteristics of sentence production in neurogenic speech disorders. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica. 2001;53:1–18. doi: 10.1159/000052649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weismer G, Kim Y-J. Classification and taxonomy of motor speech disorders: What are the issues? In: Maassen B, van Lieshout PHHM, editors. Speech motor control: New developments in basic and adapted research. Cambridge, England: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 229–241. [Google Scholar]

- Weismer G, Laures J. Direct magnitude estimates of speech intelligibility in dysarthria. Effects of a chosen standard. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 2002;45:421–433. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/033). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weismer G, Laures JS, Jeng JY, Kent RD, Kent JF. Effect of speaking rate manipulations on acoustic and perceptual aspects of the dysarthria in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopedica. 2000;52:201–219. doi: 10.1159/000021536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weismer G, Yunusova Y, Bunton K. Measures to evaluate the effects of DBS in speech production. Journal of Neurolinguistics. 2012;25:74–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroling.2011.08.006. doi:10.1016.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenke RJ, Cornwell P, Theodoros DG. Changes to articulation following LSVT(R) and traditional dysarthria therapy in non-progressive dysarthria. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2010;12:203–220. doi: 10.3109/17549500903568468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehill T, Ciocca V, Yiu E. Perceptual and acoustic predictors of intelligibility and acceptability in Cantonese speakers with dysarthria. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology. 2004;12:229–233. [Google Scholar]

- Yorkston K, Beukelman D, Strand E, Hakel M. Management of motor speech disorders in children and adults. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yorkston K, Beukelman DR, Tice R. Sentence Intelligibility Test. Lincoln, NE: Tice Technologies; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Yorkston K, Hakel M, Beukelman DR, Fager S. Evidence for effectiveness of treatment of loudness, rate, or prosody in dysarthria: A systematic review. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology. 2007;15:11–36. [Google Scholar]

- Yorkston K, Hammen VL, Beukelman DR, Traynor CD. The effect of rate control on the intelligibility and naturalness of dysarthric speech. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1990;55:550–560. doi: 10.1044/jshd.5503.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yunusova Y, Weismer G, Kent RD, Rusche NM. Breath-group intelligibility in dysarthria: Characteristics and underlying correlates. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2005;48:1294–1310. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2005/090). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]