Abstract

Basilar perforator aneurysms are rare and a communication between a basilar perforator and a separate pseudoaneurysm cavity is extremely rare. We describe a case presenting with high grade subarachnoid hemorrhage which on further investigation delineated a 2–3 mm dissecting basilar perforator aneurysm communicating superiorly into a contained 6 mm pseudoaneurysm cavity. This case illustrates an unusual neurovascular pathology with low potential for successful endovascular treatment such as coil embolization or intracranial flow diverter stenting. Conservative medical management remains the main stay of treatment for such poor surgical candidates.

Keywords: Basilar perforator aneurysm, acute subarachnoid hemorrhage, CT angiography, endovascular coil embolization, flow diversion stenting

Introduction

Basilar perforator aneurysms are rare lesions with very few reported cases. We describe a case of a 2–3 mm dissecting and ruptured basilar perforator aneurysm communicating with a separate, isolated 6 mm pseudoaneurysm cavity. This case illustrates an unusual communication of a small perforator aneurysm and pseudoaneurysm cavity that frankly ruptured into the peri-mesencephalic and pre-pontine cisterns resulting in subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). The case represents a difficult treatment paradigm with high morbidity and low potential for success either via endovascular coil embolization, flow diversion stenting, or microsurgical strategies. Medical management with meticulous antihypertensive control may be the default treatment for poor surgical candidates.

Case presentation

A 76-year-old male with past medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, cecal arteriovenous malformation, and acute myeloid leukemia presented with Hunt–Hess grade 4/Fisher grade 4 SAH with prominent pre-pontomedullary hemorrhage extending along the foramen magnum. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) head/neck findings were initially suggestive of a 2–3 mm sidewall basilar artery aneurysm (Figure 1).

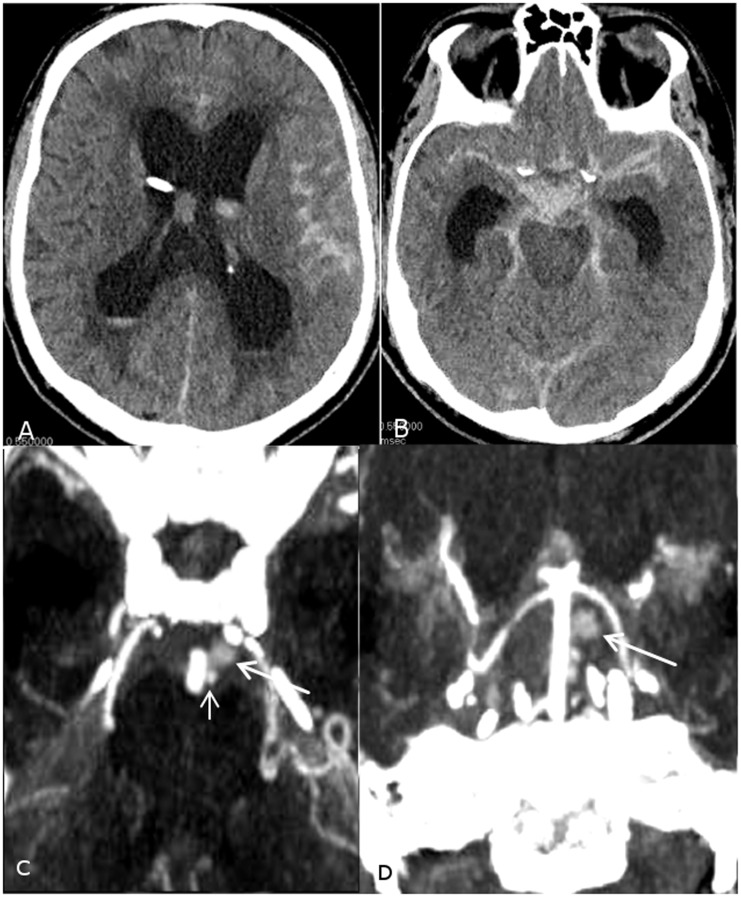

Figure 1.

(a, b) Initial axial non-contrast CT scans demonstrate Fisher grade 4 subarachnoid hemorrhage more pronounced at the prepontine cistern with intraventricular extension into both lateral ventricles resulting in supratentorial hydrocephalus. (c, d) Axial and coronal maximum intensity projection CTA reconstructions demonstrate a sidewall aneurysm arising from the basilar artery (small arrow) with adjacent contrast cavity suspicious for pseudoaneurysm (large arrow).

Conventional angiography was performed for potential endovascular treatment planning, clearly identifying the aneurysm as arising superiorly from a lateral basilar artery perforator and separate from the basilar artery sidewall, on both three-dimensional (3D) rotational and subsequent magnified oblique digital subtraction angiography (DSA) imaging. Subsequent outflow from the small perforator aneurysm was contained, superiorly into a channel communicating with a larger 6 mm saccular pseudoaneurysm cavity, also present on prior CTA head studies (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with a ruptured basilar perforator dissecting aneurysm and associated pseudoaneurysm cavity, exhibiting contrast stasis and slow washout in the capillary and venous phases. Although diagnosing a dissecting aneurysm can be challenging, it is possible that this “pseudoaneurysm” may have occurred secondary to containment of an acutely ruptured saccular perforator aneurysm, or less likely, that the dissection progressed along the course of the basilar perforator resulting in occlusion. Alternatively it may be possible that the first “saccular” structure seen in Figure 1(c) is presumably arising from the pontine perforator and may in fact represent a “pseudoaneurysm,” while the second larger and less densely filled pouch being part of the adjacent hematoma.

Figure 2.

(a–c) Left vertebral artery serial anteroposterior DSA images and (d) right vertebral artery 3D DSA reconstruction demonstrate a small aneurysm (solid arrow) arising from a left basilar artery perforator (asterisk) connected by a short stalk (arrowhead) to a larger pseudoaneurysm cavity (dotted arrow), opacified in the delayed capillary and venous phases.

The patient remained a poor surgical candidate due to comorbid conditions including a poor clinical grade presentation, elderly age, and eloquent posterior circulation location for microsurgical access. The patient was placed on vasospasm prophylaxis and antihypertensive control as well as slightly normal to high ventriculostomy drainage parameters at 10–20 cm H2O. Diagnostic cerebral angiogram and CT head study day 4 post-SAH demonstrated spontaneous occlusion of the dissecting aneurysm and large associated pseudoaneurysm, arising from the left pontine perforator, consistent with interval thrombosis (Figure 3). Unfortunately, follow-up cerebral angiography could not be performed for assessment of early aneurysm recanalization as the patient expired on day 16 post-SAH.

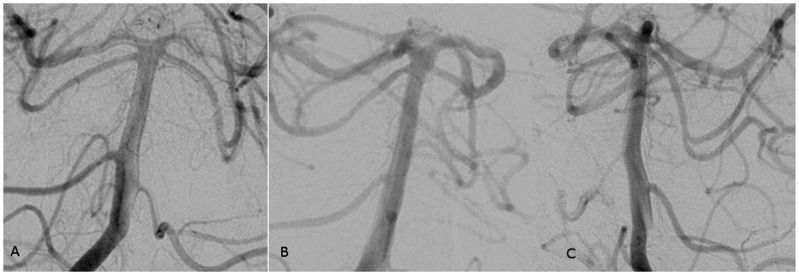

Figure 3.

(a) Right vertebral anteroposterior and (b, c) bilateral oblique DSA images performed after 4 days from the initial angiogram demonstrate normal appearance of the basilar artery with no evidence of the sidewall basilar artery aneurysm or the pseudoaneurysm cavity suggesting spontaneous thrombosis, but also poor visualization and probable interval occlusion of the associated basilar perforator.

Discussion

Basilar perforator aneurysms are exceedingly rare, but can be responsible for diffuse or a peri-mesencephalic pattern of SAH on non-contrast CT head studies. Arterial hypertension and intracranial dissection pathologies have been suspected as the inciting causes for perforator aneurysm development, but the exact etiology is unknown. Basilar artery perforators are classified into caudal, middle and rostral perforators: caudal perforators range from 2–5 in number with a diameter of 80–600 µm, middle perforators range from 5–9 in number with a diameter of 210–940 µm, and rostral perforators range from 1–5 in number with a diameter of 190–800 µm in diameter. Approximately 40–70% of these perforators anastomose with other perforators for redundancy. Aneurysms are more commonly associated with the middle or rostral basilar perforators. Male predilection in basilar artery perforating aneurysms has also been noted.1

Basilar perforator aneurysms are slow opacifying aneurysms on conventional angiography due to the small caliber of the parent vessel and commonly harbor intra-aneurysm thrombus. These characteristics make diagnostic evaluation of basilar perforating aneurysms a challenging task. Although CTA has been the initial and non-invasive assessment for acute SAH, a basilar perforating aneurysm can be easily missed due to its small size, variable location, and potential for obscuring intra-aneurysm thrombus.2 However, the CTA blood pool effect of intravenous contrast may provide some benefits of visualizing perforator aneurysms with delayed opacification. Hence it is important to maintain an index of suspicion for basilar perforating aneurysms in negative or equivocal imaging studies with careful assessment on follow-up conventional angiography in the delayed capillary and venous phases. Further utilization of other cross-sectional modalities such as magnetic resonance (MR) imaging and high resolution vessel wall imaging may be more sensitive to identify subtle or thrombosed aneurysm components. Cone beam CT after intra-arterial contrast injections with high resolution and multiplanar reconstructions could also prove a useful tool in further delineating and properly identifying these difficult cases.

On reviewing the paucity of literature, there has been debate regarding microsurgical and endovascular treatment versus conservative medical management for these lesions. Maeda et al. reported two cases of cerebral aneurysms arising from basilar perforators manifesting as intracranial and subarachnoid hemorrhages. In both cases the aneurysm was resected and the parent artery was clipped, but postoperatively one patient was severely disabled and the other died of pneumonia leading to septic shock.3 Another report by Hamel et al. described surgical resection of the aneurysm after failed attempt at endovascular coil embolization,4 but this resulted in a tension pneumocephalus with the patient suffering psychomotor slowing and gait ataxia. A literature review by Gross et al. investigated 12 cases of basilar perforator aneurysms of which three were managed conservatively.1 Only one patient developed transient third nerve palsy and hemiparesis due to cerebral vasospasm, but without permanent neurological sequelae. It was also noted that two-thirds of patients treated surgically or by endovascular coiling remained neurologically intact, while one-third suffered from neurological sequelae.1

Due to the higher morbidity from complications of aggressive endovascular treatment and/or microsurgical clipping in the eloquent posterior fossa and the inevitable sacrifice of a basilar perforator, conservative medical management may be considered. Basilar perforator aneurysms are supplied by lower flow, small caliber arteries and may spontaneously thrombose;2 however, the re-hemorrhage rates of such lesions is unpredictable. Alternatively, a basilar perforator aneurysm with compromised antegrade flow may induce the development/recruitment of anastomotic collaterals, prior to spontaneous thrombosis or allow safe vessel sacrifice for definitive treatment. Consequently, the risks of endovascular and surgical treatment as compared to conservative management should be carefully evaluated by the surgeon in such cases. Microsurgical treatment of perforator aneurysms possesses several challenging obstacles: (1) it is difficult to obtain proximal control prior to securing the lesion; (2) it is clearly not possible to perform subpial dissection around the dome of the aneurysm to completely assess the anatomy of the lesion; and (3) the surgeon must aim to preserve all the other perforating vessels while avoiding damage to the adjacent cranial nerves.2 Complications such as tension pneumocephalus have been seen for posterior fossa approaches, in particular when over drainage of cerebrospinal fluid from a ventriculostomy catheter may have occurred.

Endovascular treatment is equally difficult in these lesions as stable and safe catheterization of a basilar perforator and associated aneurysm for coil embolization or perforator sacrifice can be challenging or impossible. Alternative flow diverting stent reconstruction of the parent basilar artery has been attempted to induce progressive thrombosis and chronic aneurysm regression while attempting to maintain perforator patency, but this methodology is unproven for this rare pathology. Peschillo et al. presented three cases of basilar perforator aneurysms that were treated with flow diverting stents across the basilar artery,5 but complications occurred in all three patients. The first patient suffered from occlusion of the perforator leading to monoparesis of the upper extremity. The second procedure was complicated by immediate stent thrombosis, requiring emergent intravenous tirofiban therapy. The third patient suffered from intracranial hemorrhage along the external ventricular drain tract requiring surgical evacuation, secondary to dual antiplatelet therapy as a prerequisite for placement of intracranial stents.5 Although the complication rate is high in this series, flow diverter stent treatment may be considered on a case-by-case basis especially if the perforator aneurysm incorporates the sidewall of the basilar artery itself, to prevent early and delayed re-ruptures, which is particularly high in the reported natural history of these lesions. Despite SAH constituting a relative contraindication to the dual antiplatelet therapy, the major risks are related to the placement and removal of ventricular drains which can often be managed in the perioperative setting.

Conclusion

Basilar artery perforator aneurysms are rare neurovascular pathologies. We describe a dissecting basilar perforator aneurysm communicating superiorly to a pseudoaneurysm cavity. We stress the importance of considering these lesions in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with acute subarachnoid hemorrhage with normal or equivocal CT angiography. Perforator aneurysms not only pose a diagnostic challenge, but are equally difficult to manage. Lack of definitive endovascular and microsurgical treatment options along with a wide variety of technical challenges and perioperative complications may compel conservative medical management for co-morbid patients.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Gross BA, Puri AS, Du R. Basilar trunk perforator artery aneurysms. Case report and literature review. Neurosurg Rev 2013; 36: 163–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathieson CS, Barlow P, Jenkins S, et al. An unusual case of spontaneous subarachnoid haemorrhage: a ruptured aneurysm of a basilar perforator artery. Br J Neurosurg 2010; 24: 291–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maeda K, Fujimaki T, Morimoto T, et al. Cerebral aneurysms in the perforating artery manifesting intracerebral and subarachnoid haemorrhage: report of two cases. Acta Neurochir 2001; 143: 1153–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamel W, Grzyska U, Westphal M, et al. Surgical treatment of a basilar perforator aneurysm not accessible to endovascular treatment. Acta Neurochir 2005; 147: 1283–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peschillo S, Caporlingua A, Cannizzaro D, et al. Flow diverter stent treatment for ruptured basilar trunk perforator aneurysms. J Neurointerv Surg 2014. 011511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]