Abstract

Very few studies have been conducted on the long-term effects of typhoon damage on mesophotic coral reefs. This study investigates the long-term community dynamics of damage from Typhoon 17 (Jelawat) in 2012 on the coral community of the upper mesophotic Ryugu Reef in Okinawa, Japan. A shift from foliose to bushy coral morphologies between December 2012 and August 2015 was documented, especially on the area of the reef that was previously recorded to be poor in scleractinian genera diversity and dominated by foliose corals. Comparatively, an area with higher diversity of scleractinian coral genera was observed to be less affected by typhoon damage with more stable community structure due to less change in dominant coral morphologies. Despite some changes in the composition of dominant genera, the generally high coverage of the mesophotic coral community is facilitating the recovery of Ryugu Reef after typhoon damage.

Keywords: Mesophotic, Succession, Coral reef, Pachyseris, Japan, Typhoon recovery, Shifting communities

Introduction

Scleractinian corals are the primary architects of reef ecosystems and the major contributors to reef rugosity, a fundamental parameter for the resilience of the ecosystem after a disturbance (Graham et al., 2015). Therefore, documenting the extent of damage to corals after perturbations is key to understanding the potential trajectory of recovery. To quantify the shifts in functional composition of coral reefs after environmental and anthropogenic disturbances, Darling et al. (2012) determined coral life history strategies based on several traits, including growth form, reproductive mode, and fecundity. Shifts to stress-tolerant, generalist and weedy species after disturbances have been documented in both the Caribbean (Alvarez-Filip et al., 2009; Alvarez-Filip et al., 2011) and the Indo-Pacific (McClanahan et al., 2007; Rachello-Dolmen & Cleary, 2007). Recruitment of coral larvae can be an important factor in the recovery of a coral reef (Pearson, 1981), but plays a lesser role if there is regrowth from surviving coral colonies and/or if fragmentation occurs (Hughes, 1985). Shallow areas with few local survivors are most likely dependent on recruitment and show low rates of recovery, whereas areas with many survivors often show rapid recovery due to regrowth of remnant colonies (Connell, Hughes & Wallace, 1997).

The recovery of coral reefs after disturbances is usually measured by changes in coral cover, abundance, species composition, and/or diversity (Davis, 1982; Connell, Hughes & Wallace, 1997; Graham et al., 2015). The type of disturbance, original species composition, reef complexity (rugosity), and depth are all thought to be responsible for the wide variation in patterns of recovery. For example, a 95-year study of Dry Tortugas Reef in Florida demonstrated a relatively constant abundance of coral and other benthic organisms, despite changes in species composition and coral reef structure (Davis, 1982). However, if coral cover is significantly reduced after a disturbance, the reef will likely undergo a shift in the composition of coral species to the coral species that survived the disturbance (Connell, Hughes & Wallace, 1997), or to other taxa, such as fleshy macroalgae. For example, phase shifts from scleractinian coral dominance to fleshy macroalgae were observed after multiple storm and anthropogenic disturbances on Jamaican reefs over 40 years (Hughes, 1994).

Reports measuring coral reef recovery after storm disturbances based on coral cover on shallow reefs vary in time from two to 15 years, with little attention paid to species composition (Pearson, 1981; Platt & Connell, 2003; Gardner et al., 2005). Ecological succession (the replacement of early species with late species; Cowles, 1899) occurs following disturbances, and community recovery processes are affected by different types of disturbances that create the opportunity for a change in succession (Platt & Connell, 2003). Storms often result in various successional states or phase shifts, for which the capacity to return to the original condition has been intensively debated (Dudgeon et al., 2010; Bruno, 2014; Dixon et al., 2015). Coral cover throughout Caribbean coral reefs decreased by an average of 17% after hurricanes between 1980 and 2001, with no further coral loss in the year following a disturbance and no evidence of recovery eight years after a disturbance (Gardner et al., 2005). Gardner et al. (2005) suggested that the lack of recovery was a result of other stressors such as sedimentation or eutrophication impacting shallow reefs and that exposure to storms makes coral reefs less susceptible to storms in the future due to the recovery of more tolerant species.

Most coral reef storm recovery studies have been conducted on relatively shallow Caribbean reefs (e.g., Stoddart, 1974; Shinn, 1976; Pearson, 1981), but more work is needed to understand storm recovery on Indo-Pacific reefs in general and mesophotic reefs in particular. In one example from the Indo-Pacific, coral cover on a 6–12 m tabulate Acropora reef in the Coral Sea declined from 80% to less than 10% after several storms over a two year period, leaving only encrusting and robust coral species (Halford et al., 2004). This was followed by coral cover increasing exponentially 5–9 years after the storm disturbances, with the reef having recovered to pre-storm levels after 11 years, albeit with a shift from branching to tabulate coral morphology (Halford et al., 2004). In another example, Nozawa, Lin & Chung (2013) examined coral recruitment at 5 and 15 m depths in Taiwan, and concluded that shallower coral reefs with more pocilloporid and poritid recruits were more influenced by post-settlement processes compared to deeper reefs that have more acroporid recruits and were more affected by pre-settlement processes.

Unlike their shallow-water counterparts, there is very little information available documenting recovery of mesophotic coral reefs (benthic communities including hermatypic zooxanthellate corals at 30–150 m depths (Baker, Puglise & Harris, 2016)) after storm disturbances. Although it has often been assumed that mesophotic reefs are relatively protected from storm damage (Bongaerts et al., 2010), recent studies have shown this is not the case (Bongaerts, Muir & Bridge, 2013; White et al., 2013). The impact of storms on patterns of benthic communities documented on large horizontal scales can help to determine upper mesophotic shelf edge (30–60 m) coral development (Smith et al., 2016). Depending on the topography and distance between shallow and deep reefs, storms can damage corals on low-angle slopes as a result of coral debris or sediment transported down the reef slope compared to high-angle slopes (Bongaerts et al., 2010); whereas other low-angle upper mesophotic reefs do not appear to be impacted by terrestrial sediment transport (Weinstein, Klaus & Smith, 2015). Growth rates of different coral species may also be a factor in recovery processes (Bongaerts et al., 2015). Studies suggest that upper mesophotic coral species in the Caribbean have comparatively slower growth rates than shallow water coral species (Dustan, 1975; Hughes & Jackson, 1985; Leichter & Genovese, 2006; Weinstein et al., 2016). However, Bongaerts et al. (2015) reported that growth rates of some coral species at lower mesophotic depths (60–150 m) may be similar to observed rates in shallow water.

One of the few ecological studies monitoring the direct impact of storm damage on a mesophotic reef system is from Okinawa, Japan. Ohara et al. (2013) described Ryugu Reef as an upper mesophotic reef with a large, nearly monospecific stand of Pachyseris foliosa from 32 to 45 m. Heading deeper, away from shore, Ryugu Reef transitions on a low-angle slope from rubble with some corals (Fungiidae) at 21 m; to a high diversity of corals at 26 m; a Pachyseris- dominated area at 31 m; and finally to sand at 42 m. The center of Typhoon 17 (Jelawat), the strongest typhoon ever recorded to hit Okinawa-jima Island, with wave heights up to 12 m, passed within 30 km of Ryugu Reef on 29 September 2012 (Ohara et al., 2013; White et al., 2013). Analyses of coral species composition and morpho-functional groups on Ryugu Reef before and after Typhoon 17 suggested that the highly diverse areas were less susceptible to typhoon damage (White et al., 2013). White et al. (2013) also theorized that Ryugu Reef would be resilient because of a high likelihood of recovery based on only slight changes in functional groups after the typhoon. Despite such speculation, little is known regarding long-term recovery of mesophotic reef systems following major storm events.

Previous studies suggest that coral communities recover from storm disturbances via succession (Gardner et al., 2005; McClanahan et al., 2007; Rachello-Dolmen & Cleary, 2007; Alvarez-Filip et al., 2009; Alvarez-Filip et al., 2011; Hughes et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2016), with dominant coral genera shifting until the reef can mature and possibly return to initial conditions (Dudgeon et al., 2010; Bruno, 2014). Halford et al. (2004) observed exponential coral growth on the southern Great Barrier Reef 5–9 years after storms. Signs of recovery were documented on the Great Barrier Reef as early as 24–35 months after Tropical Cyclone Yasi in 2011, with evidence of regrowth of branching corals on King Reef (Perry et al., 2014) and an average 4% increase in coral cover on 19 reefs in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Preserve (Beeden et al., 2015). Combined, these results suggest that Indo-Pacific reefs’ successional changes may occur only a few years after a storm event. Thus, the objectives of this study include documenting the initial recovery of an upper mesophotic coral reef (Ryugu Reef) over a four-year period (2012–2015), and describing resulting changes in scleractinian coral communities based on functional morphology and species composition. This study provides the first in-depth record of an upper mesophotic reef shifting communities based on functional group changes after a storm disturbance and offers insight into the implications of this shift in the recovery of mesophotic coral reefs.

Materials and Methods

Random line transects were surveyed at Ryugu Reef (see map of stations in Fig. 1B; White et al., 2013) at seven locations near station 2 (30–32 m) and seven locations near station 3 (26–30 m). Adjacent 4 × 6 cm2 photographs (12–79 per transect) were taken along a 10-m tape for each line transect 1.5 years after Typhoon 17 (designated ‘2014’ dataset) and 2.5–3 years after the typhoon (designated ‘2015’ dataset). Scleractinian coral (+ one Millepora sp., hereafter ‘coral’) operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were identified in a similar manner as in White et al. (2013), following Hoeksema (1989) and Gittenberger, Reijnen & Hoeksema (2011) for Fungiidae, Huang et al. (2016) for Lobophylliidae, Huang et al. (2014) for Merulinidae, Diploastraeidae and Montastraeidae, and Veron (2000) for all remaining corals. Scientific binomens were checked for validity in the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS; Hoeksema & Cairns, 2015; accessed May 2, 2017). Post-typhoon data from 2012 (White et al., 2013) were combined with the newest dataset. Many mesophotic coral species at Ryugu, particularly those within genera Acropora (see Wallace, 1999), Galaxea, and Montipora, were very hard to conclusively identify to species level. Therefore, changes in the community were investigated at the genus-level. Bray-Curtis dissimilarities were calculated on raw data by comparing each transect to every other transect, and visualized using non-metric multidimensional scaling (nMDS). Time-period centroids (spatial median) were overlaid to visualize temporal dynamics. Differences in the composition of the benthic assemblage between stations, and between temporal dynamics within each station were tested using permutational multivariate analysis of variance (ADONIS).

Each coral OTU was described following similar methods to those described in Denis et al. (2013) and White et al. (2013). Corals were assigned to one or more of eight morphological groups as in White et al. (2013), following growth form information found in Wallace (1999), Veron (2000), Pillay (2002) and Bellwood et al. (2004) as well as by confirming morphologies from in situ photographs. OTU categories (massive/submassive, encrusting, laminar/foliose, columnar, plate-like, bushy, arborescent and unattached morphologies) are provided in Table S1. Often, colonies presented more than one growth form in the field, and these OTUs were therefore assigned to two growth forms. Community-level Weighted Means (CWM) of trait values (Lavorel et al., 2008) were computed for each transect, and standardized to determine the relative contribution of each morpho-functional group to the coral assemblage (removing all non-coral OTUs). Contribution of a given morpho-functional group was summarized for each station/period sampled and compared among years using Kruskal-Wallis tests followed by Conover’s multiple comparison tests.

All data were analyzed in R v3.2.3 (R Core Team, 2014) using the packages Vegan (Oksanen et al., 2016) and FD (Laliberté & Legendre, 2010; Laliberté, Legendre & Shipley, 2014).

Results

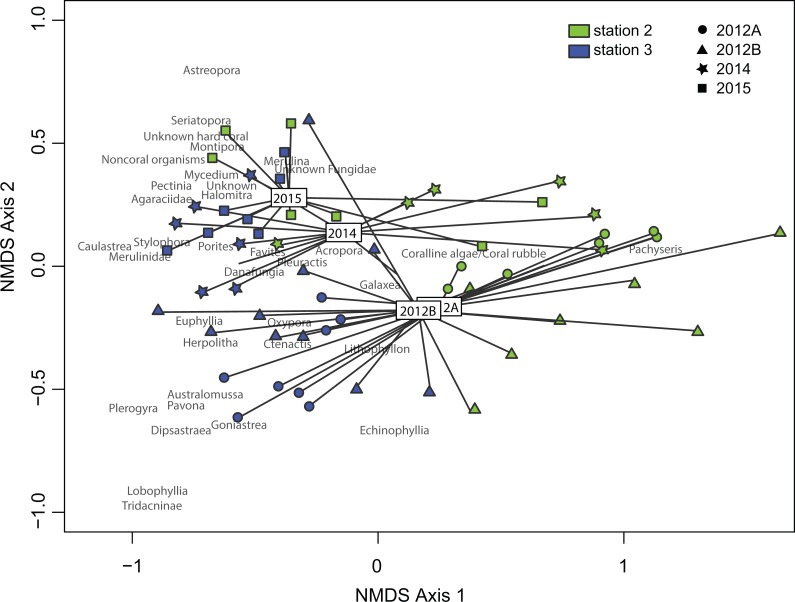

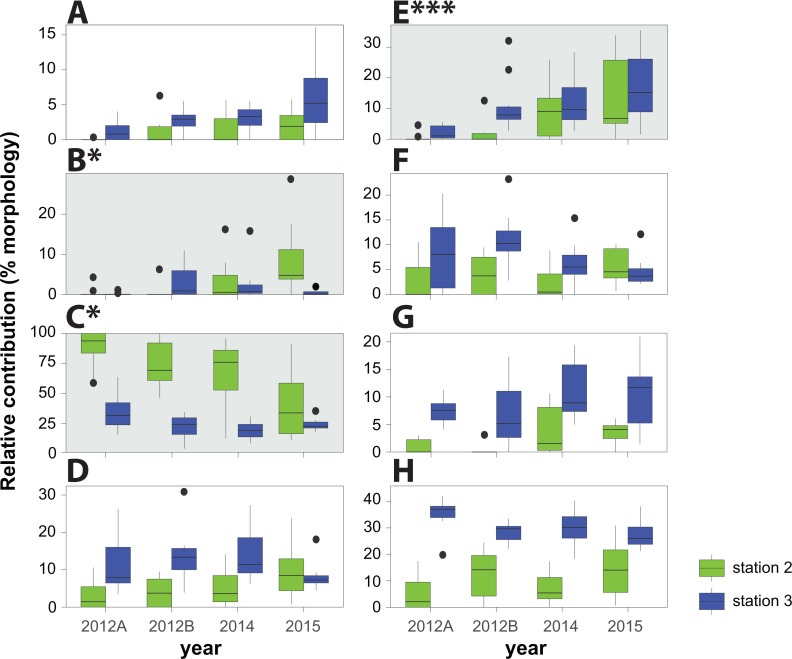

Relative live coral cover increased at each station by 5% between 2012 and 2014 and by another 6% between 2014 and 2015 (Table 1). Significant changes in cover of coral genera occurred over time at both stations 2 and 3 (ADONIS test, R2 = 0.19, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). However, variation between stations (ADONIS test, R2 = 0.41, p < 0.001) was greater than among years (Fig. 1). Station 3 showed minor changes in cover of coral genera between 2014 and 2015 after a major shift in coral assemblage between 2012 and 2014. Station 2 showed diversification of coral genera in the three years after Typhoon 17 (Jelawat) with a decrease in Pachyseris cover and an increase in several other genera (Table 1). An increase in cover of bushy corals (Acropora, Porites, Seriatopora, Stylophora) was significant (Kruskal-Wallis/Conover tests, p < 0.01) at station 3 as of 2015, compared to 2012 before the typhoon (Fig. 2). Significant coral cover changes at station 2 as of 2015 included a decrease of foliose corals, compared to 2012 before the typhoon (Kruskal-Wallis/Conover test, p < 0.05), an increase of bushy corals (Kruskal-Wallis/Conover test, p < 0.01), and an increase in some plate-like corals (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2). A major factor in the decrease of foliose coral cover at station 2 was the continuous decrease of Pachyseris from 2012 (post-typhoon) to 2015 (Table 1).

Table 1. Relative percent coral.

Relative percent cover of coral genera, coral rubble/coralline algae, and pavement at stations 2 and 3 over time after Typhoon Jelawat, 2012–2015.

| Taxonomic units | Station 2 (%) | Station 3 (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| December 2012 | April 2014 | March 2015 | December 2012 | April 2014 | August 2015 | |

| Acropora | <1 | 9 | 17 | 2 | 11 | 18 |

| Agaraciidae | 0 | <1 | <1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Astreopora | 0 | 0 | <1 | 0 | <1 | <1 |

| Australomussa | 0 | 0 | <1 | <1 | <1 | 0 |

| Caulastrea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | <1 | <1 |

| Ctenactis | <1 | <1 | <1 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Danafungia | <1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Dipsastraea | 0 | 0 | 0 | <1 | 0 | <1 |

| Echinophyllia | <1 | <1 | <1 | 4 | <1 | <1 |

| Euphyllia | 0 | 0 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| Favites | 0 | 0 | 0 | <1 | 0 | 0 |

| Galaxea | 2 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 8 |

| Halomitra | 0 | 0 | <1 | <1 | <1 | 0 |

| Herpolitha | 0 | <1 | <1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Lithophyllon | 2 | 2 | 1 | 19 | 10 | 12 |

| Lobophyllia | 0 | 0 | 0 | <1 | 0 | 0 |

| Merulina | 0 | 0 | <1 | 0 | <1 | 1 |

| Montipora | 0 | <1 | 2 | 0 | <1 | 4 |

| Mycedium | 0 | <1 | 1 | <1 | 1 | 1 |

| Oxypora | 0 | <1 | <1 | 0 | <1 | 0 |

| Pachyseris | 58 | 49 | 34 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Pavona | 0 | 0 | <1 | 4 | <1 | 2 |

| Pectinia | 0 | 0 | <1 | 0 | <1 | <1 |

| Pectiniidae | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Pleuractis | <1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Porites | 0 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| Seriatopora | 0 | <1 | <1 | 0 | <1 | 0 |

| Stylophora | 0 | 0 | <1 | 0 | <1 | <1 |

| Turbinaria | 0 | 0 | 0 | <1 | 0 | 0 |

| Coral rubble/coralline algae | 37 | 21 | 7 | 49 | 32 | 22 |

| Pavement | N/A | 11 | 19 | N/A | 12 | 16 |

| Unknown live coral | 0 | <1 | <1 | <1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total live coral cover | 63 | 68 | 74 | 51 | 56 | 62 |

Figure 1. nMDS genus data.

nMDS genus data with stress value of 0.16. Station factor (Bray-Curtis dissimilarities test, R2 = 0.41, p < 0.001); temporal factor (Bray-Curtis dissimilarities test, R2 = 0.19, p < 0.001). 2012A refers to pre-typhoon data and 2012B refers to post-typhoon data, both from White et al. (2013).

Figure 2. Community weight mean (CWM) of trait values.

Community weight mean (CWM) of trait values representing the contribution (%) of corals representing each given morphology. Significant results are shaded with a grey background (Kruskal-Wallis/Conover tests, * p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01). 2012A refers to pre-typhoon data and 2012B refers to post-typhoon data, both from White et al. (2013). (A) Arborescent; (B) Plate-like; (C) Laminar & Foliose; (D) Massive & Submassive; (E) Bushy; (F) Columnar; (G) Unattached; (H) Encrusting.

Percent cover of coral rubble/coralline algae decreased from 31% to 27% at station 2 between 2012b and 2014 from 27% to 7% between 2014 and 2015 (Table 1). This followed a 29% increase in coral rubble/coralline algae directly after typhoon Jelawat (White et al., 2013). At station 3, coral rubble/coralline algae decreased from 49% to 32% between 2012b and 2014 and from 32% to 22% between 2014 and 2015.

Discussion

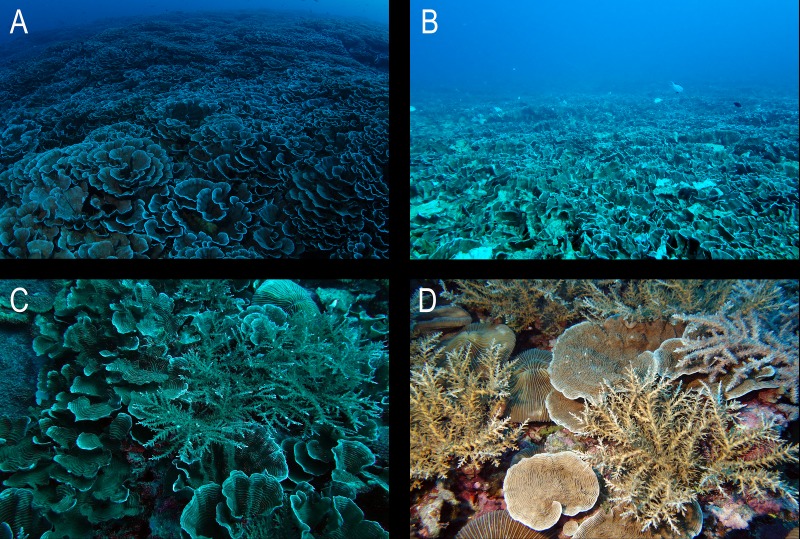

Data are sparse on the recolonization of mesophotic reefs. The diversification of mesophotic coral reef organisms after a disturbance may occur as a result of horizontal connectivity with other mesophotic reefs or vertical connectivity with shallow water reefs (Kahng, Copus & Wagner, 2014). Species with wide depth ranges are more likely to benefit from vertical connectivity, while horizontal connectivity would most likely affect only the acquisition of symbiotic zooxanthellae for species that acquire Symbiodinium from the water column (Bongaerts et al., 2010; Kahng, Copus & Wagner, 2014). Over a short time, it is likely that a storm disturbance would open up space in the area previously documented with nearly 100% Pachyseris coverage (Ohara et al., 2013), allowing more opportunistic species a chance to prosper. Station 2 showed a diversification of coral species in the three years after Typhoon 17 (Jelawat) created vacant ecological niches (Table 1). Pachyseris (foliose morphology) cover decreased immediately following the typhoon (White et al., 2013), allowing the increased growth of arborescent, bushy, columnar, massive, and encrusting morphologies (Fig. 3), although significant increases were only seen in bushy genera at this station (Kruskal-Wallis/Conover test, p < 0.01). At least six of the ‘massive’ genera (Astreopora, Caulastrea, Favites, Galaxea, Goniastrea, Plerogyra) have been noted to be ‘stress-tolerant’ and four ‘weedy’ genera (fast growing with high turnover) are known to do well under disturbance (Goniastrea, Porites, Seriatopora, Stylophora) (Darling et al., 2012). However, the dominant genus (Pachyseris) on Ryugu Reef is a ‘generalist’ (Darling et al., 2012). It appears that Typhoon Jelawat created the opportunity for genera aside from Pachyseris to increase coverage, and these genera could possibly consist of opportunistic species at upper mesophotic depths. Similarly, areas of the Great Barrier Reef recovered at different rates after disturbances, with the fastest recovery rates occurring when more space was available as a result of reduced coral cover (Graham et al., 2014). At Ryugu Reef, coral rubble cover decreased from the post-typhoon survey of 2012 (Table 1), and Pachyseris coral cover continually decreased in the four years post-typhoon. Following damages from the typhoon, diversification of the area previously dominated by Pachyseris corals occurred, with an increase in cover of genera such as Seriatopora and Galaxea. It is possible that colonies of these genera were previously present but in much smaller numbers than Pachyseris or that these genera contain opportunistic species.

Figure 3. Station 2.

Example of community shift from foliose to bushy coral genera on Ryugu Reef at station 2 (30–32 m) from (A) 2012 (pre-typhoon); (B) 2012 (post-typhoon); (C) 2014; and (D) 2015.

Immediately after Typhoon 17, little change in coral community assemblage was evident at the shallower station 3, suggesting that the diverse/complex community was more resistant due to lower impact on individual genera than the impact on the Pachyseris-dominated community (White et al., 2013). At station 3, corals recovered with progressive recolonization of the available substrate via surviving corals between 2012 (post-typhoon) and 2015 (Table 1). Cover of Acropora, Ctenactis, Danafungia, Porites, Seriatopora, and Stylophora increased, suggesting that bushy and unattached coral genera did better than the foliose genera (Montipora, Mycedium, Oxypora, Pachyseris) that stabilized with no significant increase or decrease in cover at station 3 (Table 1).

Major shifts in functional groups were evident at both stations 2 and 3 post-typhoon (Fig. 1). Foliose genera decreased at stations 2 and 3 after the typhoon, with a significant decrease as of 2015 at station 2 (Kruskal-Wallis/Conover test, p < 0.05). These results are similar to a previous shallow-water study on the Great Barrier Reef in which foliose coral colonies declined drastically after a storm event (Perry et al., 2014). Bushy coral genera increased at both Ryugu stations post-typhoon (Kruskal-Wallis/Conover test, p < 0.01). The functional shift shows that beyond the apparent recovery of Ryugu Reef, the trajectory followed could lead ultimately to a fundamentally different coral community, as previously reported from the Great Barrier Reef (Harmelin-Vivien, 1994). However, maturation of the coral assemblage with time may lead to the return of a state dominated by generalist Pachyseris corals (Darling et al., 2012). Continued monitoring of Ryugu Reef will determine whether this community will return to the initial state recorded prior to Typhoon 17 or if eventually the ecosystem might reach stability in an alternative configuration.

White et al. (2013) hypothesized that mesophotic reefs such as Ryugu would be resilient and recover quickly after disturbance to the original conditions of the reef. The current data do not support this hypothesis as a shift in community structure to more bushy and columnar morphologies and less foliose morphologies was observed. The large Pachyseris stand at station 2 was heavily damaged after Typhoon 17 (Jelawat) in 2012, but showed signs of recovery in 2015 with only slight diversification of the coral community. This fast recovery, combined with behavioral characteristics, may enable Pachyseris spp. to outcompete other coral genera at upper mesophotic depths, allowing Ryugu Reef to return to the initial, pre-typhoon coral assemblage. However, if Ryugu Reef coral genera are limited by their growth rates as many other mesophotic coral genera are (Dustan, 1975; Hughes & Jackson, 1985; Leichter & Genovese, 2006; Weinstein et al., 2016), it is more likely that there will be a permanent shift with increasing presence of weedy or stress-tolerant species (McClanahan et al., 2007; Rachello-Dolmen & Cleary, 2007; Alvarez-Filip et al., 2009; Hughes et al., 2012). While the dominant genera are changing on Ryugu Reef, there were no new species recorded, suggesting the regrowth of damaged corals or local recruitment. Examinations of shallow Acropora corals around Okinawa Main Island (Shinzato et al., 2015) and on the Great Barrier Reef after Cyclone Yasi (Lukoschek et al., 2013) both suggest the importance of local recruitment for replenishment of Acropora species, and such research remains to be conducted on corals of deeper reefs such as Ryugu Reef. The high live coral cover of Ryugu Reef suggests that although mesophotic reefs may be affected by large storms, recovery may be facilitated by the relative stability of the mesophotic zone.

Supplemental Information

Morpho-functional groups of observed Scleractinia operational taxonomic units at Ryugu, Okinawa, Japan, 2012–2015.

Acknowledgments

We thank boat captain Tokunobu Toyama for assistance in surveys. We also thank MISE lab members I Kawamura, Y Kushida, V Nestor, T Kubomura, and H Kise, who assisted with surveys. Dr. Z Richards (Western Australian Museum, Curtin University) is thanked for advice on morpho-functional groups. Suggestions from Tom Bridge and Bert Hoeksema improved an earlier version of this manuscript.

Funding Statement

V Denis is the recipient of a grant from the Ministry of Science and Technology (Taiwan, no. 104-2611-M-002-020-MY2). JD Reimer was funded by a Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) ‘Zuno-Junkan’ grant entitled “Studies on origin and maintenance of marine biodiversity and systematic conservation planning”. D Weinstein was the recipient of a JSPS short-term postdoctoral fellowship (PE14789). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

James D. Reimer is an Academic Editor for PeerJ. Taku Ohara is an employee of Benthos Divers, Onna, Okinawa, Japan.

Author Contributions

Kristine N. White performed the experiments, analyzed the data, wrote the paper, prepared figures and/or tables, reviewed drafts of the paper.

David K. Weinstein analyzed the data, wrote the paper, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Taku Ohara conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Vianney Denis analyzed the data, wrote the paper, prepared figures and/or tables, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Javier Montenegro performed the experiments, prepared figures and/or tables, reviewed drafts of the paper.

James D. Reimer conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, wrote the paper, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

Data used for statistical analyses is uploaded as a Supplemental File.

References

- Alvarez-Filip et al. (2011).Alvarez-Filip L, Dulvy NK, Côté IM, Watkinson AR, Gill JA. Coral identity underpins architectural complexity on Caribbean reefs. Ecological Applications. 2011;21:2223–2231. doi: 10.1890/10-1563.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Filip et al. (2009).Alvarez-Filip L, Dulvy NK, Gill JA, Côté IM, Watkinson AR. Flattening of Caribbean coral reefs: region-wide declines in architectural complexity. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 2009;276:3019–3025. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.0339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Puglise & Harris (2016).Baker EK, Puglise KA, Harris PT, editors. Mesophotic coral ecosystems—a lifeboat for coral reefs? The United Nations Environment Programme and GRID-Arendal; Nairobi and Arendal: 2016. p. 98. [Google Scholar]

- Beeden et al. (2015).Beeden R, Maynard J, Puotinen M, Marshall P, Dryden J, Goldberg J, Williams G. Impacts and recovery from severe Tropical Cyclone Yasi on the Great Barrier Reef. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0121272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellwood et al. (2004).Bellwood DR, Hughes TP, Folke C, Nyström M. Confronting the coral reef crisis. Nature. 2004;429:827–833. doi: 10.1038/nature02691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongaerts et al. (2015).Bongaerts P, Frade PR, Hay KB, Englebert N, Latijnhouwers KR, Bak RP, Vermeij MJ, Hoegh-Guldberg O. Deep down on a Caribbean reef: lower mesophotic depths harbor a specialized coral-endosymbiont community. Scientific Reports. 2015;5:7652. doi: 10.1038/srep07652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongaerts, Muir & Bridge (2013).Bongaerts P, Muir P, Bridge TCL. Cyclone damage at mesophotic depths on Myrmidon Reef (GBR) Coral Reefs. 2013;32:935. doi: 10.1007/s00338-013-1052-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bongaerts et al. (2010).Bongaerts P, Ridgway T, Sampayo EM, Hoegh-Guldberg O. Assessing the “deep reef refugia” hypothesis: focus on Caribbean reefs. Coral Reefs. 2010;29:309–327. doi: 10.1007/s00338-009-0581-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno (2014).Bruno JF. How do coral reefs recover? Science. 2014;345:879–880. doi: 10.1126/science.1258556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell, Hughes & Wallace (1997).Connell JH, Hughes TP, Wallace CC. A 30-year study of coral abundance, recruitment, and disturbance at several scales in space and time. Ecological Monographs. 1997;67:461–488. doi: 10.1890/0012-9615(1997)067[0461:AYSOCA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cowles (1899).Cowles HC. The ecological relations of the vegetation on the Sand Dunes of Lake Michigan. Part I.-geographical relations of the Dune Floras. Botanical Gazette. 1899;27:95–117. doi: 10.1086/327796. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Darling et al. (2012).Darling ES, Alvarez-Filip L, Oliver TA, McClanahan TR, Côté IM. Evaluating life-history strategies of reef corals from species traits. Ecology Letters. 2012;15:1378–1386. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis (1982).Davis GE. A century of natural change in coral distribution at the Dry Tortugas: a comparison of reef maps from 1881 and 1976. Bulletin of Marine Science. 1982;32:608–623. [Google Scholar]

- Denis et al. (2013).Denis V, Mezaki T, Tanaka K, Kuo C-Y, De Palmas S, Keshavmurthy S, Chen CA. Coverage, diversity, and functionality of a high-latitude coral community (Tatsukushi, Shikoku Island, Japan) PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e54330. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon et al. (2015).Dixon GB, Davies SW, Aglyamova GV, Meyer E, Bay LK, Matz MV. Genomic determinants of coral heat tolerance across latitudes. Science. 2015;348:1460–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.1261224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudgeon et al. (2010).Dudgeon SR, Aronson RB, Bruno JF, Precht WF. Phase shifts and stable states on coral reefs. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2010;413:201–216. doi: 10.3354/meps08751. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dustan (1975).Dustan P. Growth and form in the reef-building coral Montastrea annularis. Marine Biology. 1975;33:101–107. doi: 10.1007/BF00390714. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner et al. (2005).Gardner TA, Cote IM, Gill JA, Grant A, Watkinson AR. Hurricanes and Caribbean coral reefs: impacts, recovery patterns, and role in long-term decline. Ecology. 2005;86:174–184. doi: 10.1890/04-0141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gittenberger, Reijnen & Hoeksema (2011).Gittenberger A, Reijnen BT, Hoeksema BW. A molecularly based phylogeny reconstruction of mushroom corals (Scleractinia, Fungiidae) with taxonomic consequences and evolutionary implications for life history traits. Contributions to Zoology. 2011;80:107–132. [Google Scholar]

- Graham et al. (2014).Graham NA, Chong-Seng KM, Huchery C, Januchowski-Hartley FA, Nash KL. Coral reef community composition in the context of disturbance history on the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. PLOS ONE. 2014;9:e101204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham et al. (2015).Graham NA, Jennings S, MacNeil MA, Mouillot D, Wilson SK. Predicting climate-driven regime shifts versus rebound potential in coral reefs. Nature. 2015;518:94–97. doi: 10.1038/nature14140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halford et al. (2004).Halford A, Cheal AJ, Ryan D, Williams DM. Resilience to large-scale disturbance in coral and fish assemblages on the Great Barrier Reef. Ecology. 2004;85:1892–1905. doi: 10.1890/03-4017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harmelin-Vivien (1994).Harmelin-Vivien M. The effects of storms and cyclones on coral reefs: a review. Journal of Coastal Research. 1994;12:211–231. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeksema (1989).Hoeksema BW. Taxonomy, phylogeny and biogeography of mushroom corals (Scleractinia: Fungiidae) Zoologische Verhandelingen. 1989;254:1–295. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeksema & Cairns (2015).Hoeksema B, Cairns S. In: Hexacorallians of the world. Fautin DG, editor. World Register of Marine Species; 2015. [02 May 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- Huang et al. (2016).Huang D, Arrigoni R, Benzoni F, Fukami H, Knowlton N, Smith ND, Stolarski J, Chou LM, Budd AF. Taxonomic classification of the reef coral family Lobophylliidae (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Scleractinia) Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2016;178:436–481. doi: 10.1111/zoj.12391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang et al. (2014).Huang D, Benzoni F, Fukami H, Knowlton N, Smith ND, Budd AF. Taxonomic classification of the reef coral families Merulinidae, Montastraeidae, and Diploastraeidae (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Scleractinia) Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2014;171:277–355. doi: 10.1111/zoj.12140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes (1985).Hughes TP. Life histories and population dynamics of early successional corals. Proceedings of the fifth international coral reef congress, Tahiti, 4; 1985. pp. 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes (1994).Hughes TP. Catastrophes, phase shifts, and large-scale degradation of a Caribbean coral reef. Science-AAAS-Weekly Paper Edition. 1994;265:1547–1551. doi: 10.1126/science.265.5178.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes et al. (2012).Hughes TP, Baird AH, Dinsdale EA, Moltschaniwskyj NA, Pratchett MS, Tanner JE, Willis BL. Assembly rules of reef corals are flexible along a steep climatic gradient. Current Biology. 2012;22:736–741. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes & Jackson (1985).Hughes TP, Jackson JBC. Population dynamics and life histories of foliaceous corals. Ecological Monographs. 1985;55:141–166. doi: 10.2307/1942555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahng, Copus & Wagner (2014).Kahng SE, Copus JM, Wagner D. Recent advances in the ecology of mesophotic coral ecosystems (MCEs) Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability. 2014;7:72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2013.11.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laliberté & Legendre (2010).Laliberté E, Legendre P. A distance-based framework for measuring functional diversity from multiple traits. Ecology. 2010;91:299–305. doi: 10.1890/08-2244.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laliberté, Legendre & Shipley (2014).Laliberté E, Legendre P, Shipley B. FD: measuring functional diversity from multiple traits, and other tools for functional ecology. R package version 1.0-12https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=FD. 2014 doi: 10.1890/08-2244.1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lavorel et al. (2008).Lavorel S, Grigulis K, McIntyre S, Williams NSG, Garden D, Dorrough J, Berman S, Quétier F, Thébault A, Bonis A. Assessing functional diversity in the field–methodology matters! Functional Ecology. 2008;22:134–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2007.01339.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leichter & Genovese (2006).Leichter JJ, Genovese SJ. Intermittent upwelling and subsidized growth of the scleractinian coral Madracis mirabilis on the deep fore-reef slope of Discovery Bay, Jamaica. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2006;316:95–103. doi: 10.3354/meps316095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lukoschek et al. (2013).Lukoschek V, Cross P, Torda G, Zimmerman R, Willis BL. The importance of coral larval recruitment for the recovery of reefs impacted by Cyclone Yasi in the central Great Barrier Reef. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e65363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClanahan et al. (2007).McClanahan TR, Ateweberhan M, Graham NAJ, Wilson SK, Sebastian CR, Guillaume MM, Bruggemann JH. Western Indian Ocean coral communities: bleaching responses and susceptibility to extinction. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2007;337:1–13. doi: 10.3354/meps337001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nozawa, Lin & Chung (2013).Nozawa Y, Lin C-H, Chung A-C. Bathymetric variation in recruitment and relative importance of pre- and post-settlement processes in coral assemblages at Lyudao (Green Island), Taiwan. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e81474. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohara et al. (2013).Ohara T, Fujii T, Kawamura I, Mizuyama M, Montenegro J, Shikiba H, White KN, Reimer JD. First record of a mesophotic Pachyseris foliosa reef from Japan. Marine Biodiversity. 2013;43:71–72. doi: 10.1007/s12526-012-0137-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen et al. (2016).Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Kindt R, Legendre P, Minchin PR, O’Hara RB, Simpson GL, Solymos P, Henry M, Stevens H, Wagner H. Vegan: community ecology package. R package version 2.3-5https://CRANR-project.org/package=vegan 2016

- Pearson (1981).Pearson RG. Recovery and recolonization of coral reefs. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 1981;4:105–122. doi: 10.3354/meps004105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perry et al. (2014).Perry CT, Smithers SG, Kench PS, Pears B. Impacts of Cyclone Yasi on nearshore, terrigenous sediment-dominated reefs of the central Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Geomorphology. 2014;222:92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.geomorph.2014.03.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pillay (2002).Pillay RM. Field guide to corals of Mauritius. Albion Fisheries Research Centre, Ministry of Fisheries; Albion: 2002. p. 334. [Google Scholar]

- Platt & Connell (2003).Platt WJ, Connell JH. Natural disturbances and directional replacement of species. Ecological Monographs. 2003;73:507–522. doi: 10.1890/01-0552. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2014).R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rachello-Dolmen & Cleary (2007).Rachello-Dolmen PG, Cleary DFR. Relating coral species traits to environmental conditions in the Jakarta Bay/Pulau Seribu reef system, Indonesia. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 2007;73:816–826. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2007.03.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shinn (1976).Shinn EA. Coral reef recovery in Florida and the Persian Gulf. Environmental Geology. 1976;1:241–254. doi: 10.1007/BF02407510. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shinzato et al. (2015).Shinzato C, Mungpakdee S, Arakaki N, Satoh N. Genome-wide SNP analysis explains coral diversity and recovery in the Ryukyu Archipelago. Scientific Reports. 2015;5:18211. doi: 10.1038/srep18211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith et al. (2016).Smith TB, Brandtneris VW, Canals M, Brandt ME, Martens J, Brewer RS, Kadison E, Kammann M, Keller J, Holstein DM. Potential structuring forces on a shelf edge upper mesophotic coral ecosystem in the US Virgin Islands. Frontiers in Marine Science. 2016;3 doi: 10.3389/fmars.2016.00115. Article 115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddart (1974).Stoddart DR. Post-hurricane changes on the British Honduras reefs: re-survey of 1972. In: Cameron AM, Cambell BM, Cribb AB, Endean R, Jell JS, Jones OA, Mather P, Talbot FH, editors. Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Coral Reefs. Vol. 2. Great Barrier Reef Committee; Brisbane: 1974. pp. 473–483. [Google Scholar]

- Veron (2000).Veron JEN. In: Corals of the world. Stafford-Smith M, editor. Vol. 3. Australian Institute of Marine Science Monograph Series; Cape Ferguson: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace (1999).Wallace C. Staghorn corals of the world: a revision of the coral genus Acropora. CSIRO; Collingwood: 1999. p. 421. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, Klaus & Smith (2015).Weinstein DK, Klaus JS, Smith TB. Habitat heterogeneity reflected in mesophotic reef sediments. Sedimentary Geology. 2015;329:177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.sedgeo.2015.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein et al. (2016).Weinstein DK, Sharifi A, Klaus JS, Smith TB, Giri SJ, Helmle KP. Coral growth, bioerosion, and secondary accretion of living orbicellid corals from mesophotic reefs in the US Virgin Islands. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2016;559:45–63. doi: 10.3354/meps11883. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White et al. (2013).White KN, Ohara T, Fujii T, Kawamura I, Mizuyama M, Montenegro J, Shikiba H, Naruse T, McClelland TY, Denis V, Reimer JD. Typhoon damage on a shallow mesophotic reef in Okinawa, Japan. PeerJ. 2013;1:e151. doi: 10.7717/peerj.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Morpho-functional groups of observed Scleractinia operational taxonomic units at Ryugu, Okinawa, Japan, 2012–2015.

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

Data used for statistical analyses is uploaded as a Supplemental File.