Abstract

The extant literature documents burden among caregivers of patients undergoing a hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), but little is known about the burden of caregivers of patients receiving outpatient and homebound HSCTs. This scoping study sought to evaluate what is known about the burden of the increasing number of adult caregivers of patients receiving outpatient HSCTs and to create practice guidelines for how to best support this vulnerable group. Online databases were searched for studies that evaluated caregiver burden in adult caregivers of HSCT patients since 2010 (the publication date of the most recent systematic review on HSCT caregiver burden). Of the 1,271 articles retrieved, 12 met inclusion criteria, though none specifically examined outpatient or homebound caregivers. Overall, studies corroborated existing literature on the experience of significant burden among HSCT caregivers across the HSCT trajectory, and highlighted the emotional costs of outpatient transplants on caregivers and the need to identify caregivers at high risk for burden early in the transplant process. Future studies of outpatient caregivers should include a comprehensive assessment of burden and seek to identify points along the transplant trajectory at which caregivers are at particular risk for negative outcomes and when intervention is most appropriate.

Keywords: caregivers, family, hematopoietic stem cell transplant, burden, outpatient HSCT, caregiver strain

Introduction

HSCT is a treatment option available for patients with high-risk hematologic malignancies and non-malignant diseases sensitive to immune modulation (1). HSCT recipients receive allogeneic (unrelated, related) or autologous (self) stem cells (peripheral blood, bone marrow, cord blood) dependent on donor availability and human leukocyte antigen compatibility. These factors, along with the intensity of the preparative regimen (myeloablative, reduced intensity (RIC), non-myeloablative), demographic, and disease characteristics, create a complex treatment requiring the assistance of many trained professionals.

Traditionally, HSCT, especially allogeneic, is performed in an inpatient setting where patients are monitored by health care professionals for life-threatening complications such as cytopenias, infections, and acute graft-versus-host disease. Comprehensive assessment and rapid management of treatment toxicities are critical to ensuring success of HSCT. After a myeloablative regimen, where the treatment-related toxicities are often more severe, the median length of the initial hospitalization ranges from 25 to 30 days. (2, 3)

The outpatient or ambulatory care setting is increasingly used for less intense HSCT, such as autologous and reduced-intensity and non-myeloablative allogeneic HSCT. Outpatient HSCT involves providing the patient with the preparative regimen and cell infusion in an ambulatory environment (4). Evidence suggests this practice is safe and may be superior to isolation in the hospital. One study found that discharge to home after allogeneic HSCT was associated with decreased bacteraemia, antibiotic and analgesic use, fewer erythrocyte transfusions and decreased need for parenteral nutrition (5). The results also highlighted decreased costs associated with home care, and improved appetite and quality of life.

Informal caregivers (ICs; also referred to as family caregivers in the extant literature) include parents, partners, siblings, children, and friends who are intimately involved in the patient’s care and play a critical role in the recovery from HSCT. In the majority of cases, an IC is a required and critical element of the HSCT process. One study found that when an IC was involved during the hospitalization phase of HSCT, the overall survival for the patient at four years was 42% compared to 26% among recipients without an IC (6). Moreover, the cost cutting and feasibility reportedly associated with care of HSCT patients in the outpatient or homebound setting (6) appears to be mediated in large part by the efforts of ICs (7), whose involvement is needed to decrease the necessity for hospital readmissions.

As a result of the many possible complications faced by post-HSCT patients, most centers offering outpatient HSCTs require the availability of an IC for 24 hours a day, seven days a week, for the duration of the post-HSCT period to assume many responsibilities traditionally carried out by professionals. Such an agreement represents a complete devotion of ICs’ time to the patient, which impacts multiple areas of ICs’ lives, including the ability to engage in their own health-promoting behaviors (7, 8). ICs of patients receiving outpatient HSCTs prepare their homes to avoid potential infectious complications, are responsible for the administration of medications, monitoring of vital signs, and intake and output of fluids (9). Additionally, while ICs of patients receiving inpatient HSCTs are often tasked with the transportation of the patient to the treatment center multiple times a week after discharge, ICs of outpatient HSCT patients may be required to facilitate daily visits. Not surprisingly, such ICs often have difficulty maintaining full-time, paid employment. In an observational study, Simoneau et al. demonstrated the changes in employment status among 109 ICs of allogeneic blood or marrow transplant patients (8); full time employment decreased from 51% before caregiving to 27% during caregiving, while the percentage of those on leave from work altogether increased from 2% to 25% (8).

Caregiver burden describes the potential negative impact of the patient’s illness on ICs, and encompasses the multiple difficulties of caregiving and associated alterations in ICs’ emotional and physical health that can occur when care demands exceed resources (10). The burden experienced by cancer ICs is well documented (11–16) and a growing number of studies have demonstrated the burden of ICs of patients receiving inpatient HSCTs (7, 8, 17–19). Indeed, while several systematic reviews have evaluated the burden of ICs of patients receiving HSCT (20, 21), only a few studies reviewed included ICs of patients receiving HSCTs in the outpatient or homebound setting (22, 23), likely due to the relative infancy of such practices. Gemmill et al. reviewed the literature on the quality of life, roles, and resources of HSCT ICs, as well as existing interventions, none of which were focused on the needs of outpatient ICs (20). The authors highlighted the need to develop supportive services for HSCT ICs and use existing descriptive evidence of caregiver burden for the basis of such interventions. Beattie et al. noted that an increase in outpatient HSCTs is likely associated with an increase in IC burden (21). Their conclusions highlight the dearth of investigations that include outpatient ICs and the need for a greater understanding of such ICs’ experiences and support needs. While the trend to move allogeneic HSCT patients to an outpatient setting has the potential to have a significant, negative impact on ICs’ overall psychological and physical health (24) risks, these outcomes currently remain largely unaddressed.

The purpose of this scoping study (25) was to expand on the existing literature on burden among ICs of patients receiving HSCT summarized by the two most recent existing systematic reviews (20, 21), and specifically, to evaluate what is known about the experiences of ICs of patients receiving HSCTs in the outpatient and homebound setting. A second goal of this study was to, based on our review, create practice guidelines for how to best support outpatient and homebound HSCT ICs.

Method

An electronic literature search of articles published in any language since 2010 was conducted in PubMed, PsycINFO (Psychological Abstracts) via OVID, Cochrane via Wiley, EMBASE provided by Elsevier, CINAHL via EBSCO, and Web of Knowledge provided by Thompson Reuters. Grey literature sources were also searched and reviewed to include Open Grey, World Catalogue for doctoral dissertations, SCOPUS and BIOSIS Previews® for conference proceedings and meeting abstracts. Controlled vocabulary (MeSH, PsycINFO Subject Headings, CINAHL Headings, EMTREE) and keywords were used.

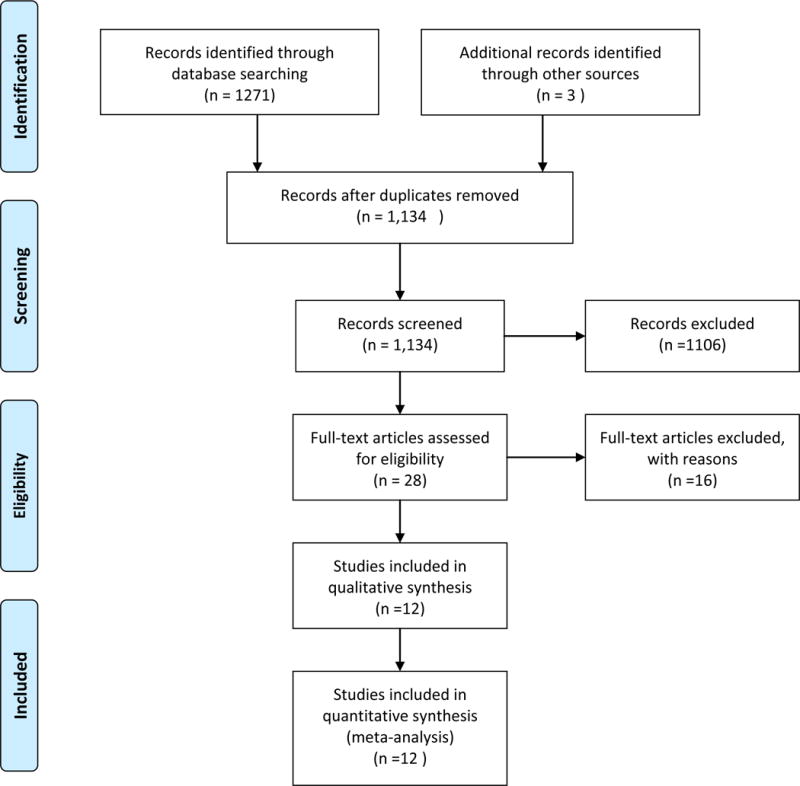

Three broad concept categories were searched, and results were combined using the appropriate Boolean operators (AND, OR). These categories included: caregivers and burden and bone marrow transplantation. Related terms were also incorporated into the search strategy to ensure all relevant papers were retrieved. The Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) used were as follows: (“Caregivers”[Mesh] OR “Family”[Mesh] OR “Spouses”[Mesh]) AND (“Adaptation, Psychological”[Mesh] OR “Stress, Psychological”[Mesh] OR “Quality of Life”[Mesh]) AND (“Bone Marrow Transplantation”[Mesh] “Hematologic Neoplasms”[Mesh]). Keyword terms included: (informal caregiver OR caregiver OR spouse OR family) AND (strain OR distress OR stress OR burden OR self neglect OR quality of life OR QOL) AND (BMT OR bone marrow transplant*). Studies were included if they enrolled adult ICs of HSCT patients, and both quantitative and qualitative studies were included. The PRISMA flow diagram of this search strategy is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram

Results

The search produced 1,271 articles and once duplicates were removed, 1,137 articles remained. The titles and abstracts were reviewed by two independent members of the team, and differences were discussed with a third member until consensus was reached. A final sample of 12 studies met inclusion criteria and was included in the review. The majority were either cross-sectional (N=6, 50%) or longitudinal (N=5, 42%), with one employing mixed methods. Six studies enrolled patients receiving allogeneic HSCTs, and six enrolled patients undergoing both types of HSCTs. While the majority (N=8, 67%) of studies included assessments conducted post-HSCT in the outpatient setting, all patients received their HSCTs and acute care in the inpatient setting. No studies examined the experience of ICs of patients undergoing outpatient or homebound allogeneic HSCT.

Key characteristics of ICs enrolled in the reviewed studies are presented in Table 1. ICs were predominantly female, White, partnered, employed full time, and were the spouse/partner of the patient undergoing transplant. Table 2 presents the assessment strategy used to evaluate burden as defined by the individual study. The majority of studies indicated in either their titles or abstracts that caregiver burden was conceptually of interest, however, only four included a comprehensive multidimensional measure of burden (8, 26–28). One additional study examined role strain (29) which is very closely linked conceptually to burden. Instead, 75% of studies examined specific correlates of burden, including anxiety and depression (27, 28, 30–32), quality of life (29, 31), unmet needs (33), fatigue (27, 30, 32), and relationship quality (29, 30, 34). Additionally, one study examined the potential benefits (i.e., meaning, growth) derived from caregiving. Despite the variation in the measures of burden and the correlates explored, emotional burden or psychological distress (i.e., depression, anxiety) was consistent.(29).

Table 1.

Study & Caregiver Characteristics

| Author | Study Design | Transplant Type | Patient Status at Time of Evaluation | Age (Mean (SD)) | % Female | Race/Ethnicity | Education | Employment Status | Relationship to Patient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akgul & Ozdemir, 2014 | C | Both | O | 44.01 (14.04) | 69.1 | NR | 45.45% HS grad 52.7% Primary school |

NR | 56.5% Spouse |

| Armoogum, Richardson, & Armes, 2013 | C | Both | O | 51.8 (12.4) | 69 | 84% White, 11% other |

43% HS grad | 58% full time 21% retired 10% homemaker |

73% spouse/partner 8% parent 7% child 5% other |

| Bevans et al., 2014 | L | Allo | O | 52.8 (12.9) | 71.2 | 75.8% White 10.6% African American 7.6% Hispanic |

45.5% Bachelor’s or graduate degree | 40.9% full or part time | 51.5% spouse 40.9% family member/non-spouse 7.6% friend |

| Bishop et al., 2011 | C | Both | O | 51.3(9.1) | 46.7 | 90% White | 6.7% HS or less 36.6% some college 56.7% college+ |

66.7% full time 13.3% part time 20% not working |

100% spouse/partner |

| Cooke et al., 2011 | C | Allo | O | NR | 50 | 80.4% White | 18.9% HS grad 73.6% some college |

NR | NR |

| El-Jawahri et al., 2015 | L | Both | I | 55.8 (median) (14.0) | 70.2 | 97.9% White | 27.7% HS 48.9% College 23.4% Postgraduate |

46.8% full time 12.8% part time 29.8% retired 4.3% paid leave 6.4% unemployed |

72.3% partner 6.4% sibling 6.4% child 10.6% parent 4.3% friend |

| Jim et al., 2014 | C | Allo | O | Median 55 (25–80) | NR | 100% White: (88% Non-Hispanic) |

38% College Grad | 79% working | NR |

| Langer et al., 2010 | L | Both | O | 43.5(9.8) | 48 | 90.1% White 4.9% Other 5% Hispanic |

54.6% < 4 year college | NR | 100% spouse/partner |

| Langer et al., 2012 | L | Allo | I&O | 54 | 72 | 96% White | 61% College | NR | 100% spouse/partner |

| Laudenslager et al., 2015 | L | Allo | I&O | 53.5 (CI 51.5, 55.5) | 75.7 | 89.9% White 8.2% Other |

79.1% College or above | 23.6% full time 11.5% part time 14.9% unemployed 24.3% on leave 20.3% retired |

69.6% spouse/partner 18.2% parent 10.8% other |

| Sabo, McLeod &Couban, 2013 | M | Both | O | “30’s–60s” | 64 | 100% White | NR | NR | 100% spouse/partner |

| Simoneau, et al., 2013 | C | Allo | Pre-HSCT | 52.2 (11.3) | 77 | 95% White | 55% College or above | Before caregiving: 51% Full time 17% Part time 12% Unemployed 2% On leave 16% Retired During caregiving: 27% Full time 13% Part time 15%Unemployed 25% On leave 18% Retired |

75% Spouse/Partner 15% Parent 10% Other |

NR = Not reported.

C= Cross-sectional

L= Longitudinal

M= Mixed methods

Allo= Allogeneic

I= Inpatient

O= Outpatient

I&O= Inpatient and Outpatient

Auto= Autologous

CI = Confidence Interval

Table 2.

Measurement of Burden and Correlates

| Author | Outcome Variables | Assessment Measure |

|---|---|---|

| Akgul & Ozdemir, 2014 | Burden | Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) The Caregiver Questionnaire (IGM) |

| Armoogum, Richardson, & Armes, 2013 | Unmet supportive care needs | Supportive Care Needs Survey Partners and Carers (SCNS-P&C) General Health Questionnaire (GHQ12) |

| Bevans et al., 2014 | Self-Efficacy Psychological Distress Health Behaviors Sleep Quality Fatigue Relationship Quality |

Cancer Self-Efficacy Scale-transplant (CASE-t) Brief Symptom Inventory – 18 (BSI-18) HPLP-II Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory – Short Form (MFSI-SF) Family Caregiving Inventory (mutuality scale) |

| Bishop et al., 2011 | Long lasting negative changes after cancer | Qualitative Interviews |

| Cooke et al., 2011 | Relationship quality Rewards of caregiving Predictability Role strain/activities Quality of Life |

Mutuality Scale Rewards of Caregiving Scale Predictability Scale Caregiver Activities and Role Strain (IGM) City of Hope QOL-Family |

| El-Jawahri et al., 2015 | Quality of Life Anxiety and Depression Depressed Mood |

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Bone Marrow Transplant (FACT-BMT) Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 (PHQ-9) |

| Jim et al., 2014 | Anxiety Insomnia Helplessness Guilt Fatigue Fear of Cancer Recurrence |

Qualitative Interviews/Focus Groups |

| Langer et al., 2010 | Marital Adjustment | Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS) |

| Langer et al., 2012 | Positive and Negative Affect | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) |

| Laudenslager et al., 2015 | Control Over Stress Depression State Anxiety Caregiver Burden Total Mood Disturbance Sleep Quality Mental and Physical Health Trauma |

Perceived Stress Scale Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) Caregiver Reaction Assessment (CRA) Profile of Mood States (POMS-TMD) Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Inventory (PSQI) Short Form Health Survey Version 2, SF-36) Impact of Event Scale (IES) |

| Sabo, McLeod &Couban, 2013 | Caregiver Burden Depression Secondary Trauma |

Caregiver Quality of Life – Cancer (CQOLC) Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) Professional Quality of Life Scale (PRO-QOL-R-IV) Qualitative Interviews |

| Simoneau, et al., 2013 | Caregiver Burden Stress Health Affect |

Caregiver Reaction Assessment (CRA) Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) Impact of Events Scale (IES) Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) Profile of Mood States (POMS) Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) |

Note.

Investigator Generated Measure

The majority (N=8, 67%) of studies were descriptive in nature (8, 26, 28, 29, 31–33, 35). Overall, the findings of these studies corroborated existing literature on the experience of significant burden among HSCT ICs across the HSCT trajectory. For example, the results of Simoneau et al’s investigation of 109 allogeneic HSCT ICs indicated significantly high levels of distress prior to HSCT (8). El-Jawahri evaluated QOL and mood among ICs during patients’ hospitalization and found that not only did depressive symptomatology increase overall during the hospital course, but notably, the percent of ICs meeting criteria for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) nearly tripled from baseline to day eight (31). Sabo et al. followed ICs for one year, starting immediately before transplant and through mixed-methods assessments found distress waxed and waned at critical points (i.e., before HSCT and 6 weeks-, 6 months-, and 1 year – post HSCT), but burden remained consistent and impairing (28).

The evidence presented suggests that during of the first 100 days following HSCT, the needs of the patient, especially management of their symptoms, can exacerbate ICs’ psychological distress (8, 26, 28, 31–33). These findings are in accord with those summarized in the two most recent systematic reviews. Importantly, when ICs’ report higher impact of caregiving on their role, their capacity to engage in paid employment, and relationship with others, their distress is even greater (26). Burden was also associated with demographic factors such as low education, younger age, and financial difficulties (8, 26).

A unique element of burden not captured in previous reviews but highlighted here was existential distress faced by ICs when asked to provide emotional support to patients generally, and support around fears regarding end-of-life and dying, specifically. For example, Cooke et al. asked ICs of 56 patients within 3 to 12 months of allogeneic SCT to rank order elements of their role they found most distressing (29). ICs reported that providing emotional support to patients and discussing their concerns about death were most distressing, while handling their own emotions and providing physical care was least difficult.

Four studies presented interventions, three of which specifically targeted various elements of burden among HSCT ICs (27, 30, 36), and one which was focused on patient needs but invited IC participation (34). Bevans et al. examined the impact of three, one-hour problem solving education sessions (delivered at discharge, weeks one and three) on self-efficacy and distress in ICs of allogeneic HSCT patients (30). Assessment occurred pre-HSCT, at HSCT, and at week 6. The results indicated that responders reported decreased confidence and increased distress prior to transplant, and improvement in self-efficacy and distress was associated with decreased fatigue, and improved sleep and health promoting behaviors (30). Laudenslager et al. conducted a randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral stress management delivered individually over eight sessions across the 100 day post-transplant period(27) and examined both psychosocial (e.g., depression and anxiety) and physiological (i.e., cortisol awakening response, CAR) factors. The intervention was associated with significantly lower distress, depression and anxiety three months post-transplant, but CAR did not change. Importantly, this improvement in psychosocial functioning occurred in the setting of increasing burden, as indicated by scores on the Caregiver Reaction Assessment (CRA) (27). Finally, Langer et al. examined the impact of an expressive talking intervention for ICs of transplant survivors delivered on days 50, 53 and 56 post-transplant (36). Participants were instructed to speak specifically about their deepest thoughts and feelings about their partner’s transplant and their experience as an IC. Despite perceiving the sessions as helpful, participants randomized to the intervention experienced more negative emotions (as assessed by the PANAS) (36). The authors also measured skin conductance as a physiologic indicator of emotional intensity and results suggested sustained emotional engagement (36).

Discussion

The shifting of HSCT from the inpatient to the outpatient and homebound settings presumably will require ICs to assume increased role demands and responsibilities starting earlier in the treatment course compared to the traditional inpatient HSCT model. Similar to the findings of the two most recent existing systematic reviews (20, 21), across studies, role strain and unmet needs emerged as key areas of burden, which are similarly well documented and likely to increase in the setting of the homebound HSCT. For example, Gemmill et al (20) concluded that the complexities of the demands of the caregiving role and social problems such as isolation, financial demands, and family tension, are significant areas of burden among ICs. Similarly, Beattie et al. (21) highlighted the significant impact of the caregiving role on all domains of ICs’ lives and the distress experienced pre-HSCT, when ICs are tasked with quickly learning how to provide care to patients in preparation for their return home.

Importantly, however, data are limited on the unique experience of ICs of HSCT patients receiving their transplants in the outpatient and homebound settings. This represents a critical gap in our understanding, since ICs are likely receiving significantly less professional support and have considerably increased responsibilities in these environments. The results of this review add to the growing body of literature demonstrating distress and burden among HSCT ICs, though no studies focused specifically on the experience of ICs of patients receiving outpatient or homebound HSCTs. Notably, time since transplant and length of caregiving were not consistently or adequately described. Across studies, minimal details were given regarding the time that had elapsed between day of transplant and assessment of the IC, and no study documented specific details of the length of time the IC had been in that role.

This scoping study revealed challenges in evaluating burden across studies, partially attributed to a lack of uniformity in how burden was operationalised and measured. Given et al. (37) describe burden as a “multidimensional biopsychosocial reaction resulting froman imbalance of care demands relative to caregivers’ personal time, social roles, physical and emotional states, financial resources, and formal care resources given the other multiple roles they fulfill” (as cited in Given et al., 2001b) (37). This definition is multidimensional, yet as seen in many of the studies reviewed here, the construct is often measured as one that is unidimensional, such as depression. It is therefore critical for researchers to understand the multidimensionality of burden and include measurement strategies that account for such dimensionality in their assessment plans. While no gold standard measures has been established, the Caregiver Reaction Assessment (CRA) (38) appears to be the most widely used measure of caregiver burden in cancer research. Advantages of the CRA include its assessment of both the positive and negative aspects of caregiving and its five multidimensional subscales which capture the broad spectrum of areas impacted by caregiving. It is psychometrically sound (Cronbach’s alpha from the initial study ranges between 0.80 to 0.90) (38) and has been validated across a variety of patient populations and cultures (39–42). Importantly, the results from one study reviewed here suggests that while burden as measured by the CRA may remain high, particular domains of psychosocial functioning may concurrently improve (27). This potentially counterintuitive finding deserves greater attention, and replication studies are needed before conclusions about the relationship between burdens generally and specific psychosocial distress can be drawn. Specifically in transplantation, the CRA has been employed much less frequently, which limits our ability to draw conclusions about specific elements of burden in the samples evaluated. Future studies of distress among HSCT ICs across the caregiving trajectory and across settings should include the CRA so that more streamlined comparisons across samples will be possible and a clearer understanding of the multiply determined burden among such ICs can be derived.

Practice Recommendations

This review highlights the significant risk for depression among HSCT ICs and the clear need for screening and intervention (e.g., El-Jawahri et al.(31)). It is critical that transplant providers (e.g., oncologists, nurse practitioners) screen for burden and distress, and based on these assessments, make targeted referrals to mental health professionals for further assessment and the provision of intervention and supportive resources. There is growing evidence to support the use of brief self-assessment measures – such as the Caregiver Self-Assessment Questionnaire ((43) and the Distress Thermometer (DT) (44) – which can be used to screen for distress and identify caregivers in need of support services. The single-item DT has been used extensively in psychosocial oncology and previously with HSCT IC samples, and has demonstrated construct validity in this population (45).

Evaluating depression in the pre-HSCT period will help to implement services pre-HSCT to prevent against worsening depression and enhance ICs’ ability to provide care and develop and sustain resilience during the transplant process. Moreover, as recovery at home is a family experience and hence, the success of recovery is contingent in large part on functioning of ICs, evaluating family functioning pre-HSCT will highlight potential challenges within the family system to which the patient is being discharged (46). This will allow for both the determination of the appropriateness of the discharge to home, and for targeted intervention for family systems in need of acute support before and during the discharge process. Moreover, a study of the family experience following inpatient transplantation (47) suggested that there is need for more external caregiving/support at home during the first year after HSCT, and such professional in-home help may help to relieve some of the strain/burden experienced and can ultimately help to strengthen the patient/caregiver relationship.

Interventions tailored to the unique needs of homebound ICs are needed. While psychoeducation fosters self-efficacy, alone it is not sufficient to prevent or ameliorate burden. Interventions that are flexibly administered, delivered early in the transplant process to protect ICs against poor psychosocial outcomes, and which teach skills needed to both provide care for the patient and help ICs attend to their own needs during the HSCT process, are needed. Also unique to the findings of this review is the need for interventions that attend to existential distress, and often overlooked element of burden among HSCT caregivers (29).

Limitations

The initial purpose of this scoping study was to evaluate the burden that results from providing care to patients receiving HSCT in the outpatient setting. This literature was restricted and therefore we are unable to comment specifically on the experience of burden among outpatient HSCT ICs. Additionally, due to inconsistencies in the use of the term “burden” and inconsistencies in the measurement strategies employed, the review may have failed to capture studies that assessed various elements subsumed under the multidimensional construct of burden. Moreover, the majority of studies included in this review enrolled participants who were predominantly White and non-Hispanic, thereby omitting other vulnerable, ethnic minority populations and limiting the generalisability of conclusions and implications.

Conclusions and Future Directions

It is imperative that interdisciplinary teams unite around new models of HSCT administration and include IC outcomes as a target for assessment. Routine screening for distress among ICs will facilitate the implementation of early supportive care services, including referrals to appropriate ancillary services.(20, 48) Such screening should also including continued routine monitoring and follow-up throughout the HSCT trajectory in order to identify and support ICs whose distress may fluctuate along the course of patient care.

Future research should be directed toward deriving a more detailed understanding of HSCT recipients’ and ICs’ experiences and needs during the outpatient and home-bound procedure and recovery. Risk factors that deserve attention and should be more consistently captured include race/ethnicity, education and income status, extent of caregiving (i.e., years, hours per week), and changes in family dynamics/relations, (26) along with clinical factors such as type of HSCT.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported in part by grant P30 CA008748 (PI Thompson)- Cancer Center Support Grant

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Pasquini MC., ZX Current uses and outcomes of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Svahn BM, Ringden O, Remberger M. Long-term follow-up of patients treated at home during the pancytopenic phase after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone marrow transplantation. 2005;36(6):511–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pavletic ZS, Arrowsmith ER, Bierman PJ, Goodman SA, Vose JM, Tarantolo SR, et al. Outcome of allogeneic stem cell transplantation for B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Bone marrow transplantation. 2000;25(7):717–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solomon SR, Matthews RH, Barreras AM, Bashey A, Manion KL, McNatt K, et al. Outpatient myeloablative allo-SCT: a comprehensive approach yields decreased hospital utilization and low TRM. Bone marrow transplantation. 2010;45(3):468–75. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Svahn B, Bjurman B, Myrbäck K, Aschan J, Ringden O. Is it safe to treat allogeneic stem cell transplant recipients at home during the pancytopenic phase? A pilot trial. Bone marrow transplantation. 2000;26(10):1057–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster LW, McLellan L, Rybicki L, Dabney J, Copelan E, Bolwell B. Validating the positive impact of in-hospital lay care-partner support on patient survival in allogeneic BMT: a prospective study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48(5):671–7. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grimm PM, Zawacki KL, Mock V, Krumm S, Frink BB. Caregiver Responses and Needs. Cancer Practice. 2000;8(3):120–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2000.83005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simoneau TL, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK, Natvig C, Kilbourn K, Spradley J, Grzywa-Cobb R, et al. Elevated peri-transplant distress in caregivers of allogeneic blood or marrow transplant patients. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22(9):2064–70. doi: 10.1002/pon.3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDiarmid S, Hutton B, Atkins H, Bence-Bruckler I, Bredeson C, Sabri E, et al. Performing allogeneic and autologous hematopoietic SCT in the outpatient setting: effects on infectious complications and early transplant outcomes. Bone marrow transplantation. 2010;45(7):1220–6. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bevans MF, Spence Cagle C, Coleman M, Haisfield-Wolfe ME, Jadalla A, Page M, et al. Caregiver Strain and Burden: Oncology Nursing Society. Available from: https://www.ons.org/practice-resources/pep/caregiver-strain-and-burden.

- 11.Vess JD, Jr, Moreland JR, Schwebel AI. A follow-up study of role functioning and the psychological environment of families of cancer patients. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 1985;3(2):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Northouse LL. The impact of cancer on the family: An overview. International Journal of Psychiatric Medicine. 1984;14:215–42. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siegel K, Raveis VH, Houts P, Mor V. Caregiver burden and unmet patient needs. Cancer. 1991;68(5):1131–40. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910901)68:5<1131::aid-cncr2820680541>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kissane DW, Bloch S, Burns WI, McKenzie D, Posterino M. Psychological morbidity in the families of patients with cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 1994;3(1):47–56. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyle D, Blodgett L, Gnesdiloff S, White J, Bamford AM, Sheridan M, et al. Caregiver quality of life after autologous bone marrow transplantation. Cancer nursing. 2000;23(3):193–203. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200006000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Given BA, Given CW, Kozachik S. Family support in advanced cancer. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2001;51(4):213–31. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.51.4.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foxall MJ, Gaston-Johansson F. Burden and health outcomes of family caregivers of hospitalized bone marrow transplant patients. Journal of advanced nursing. 1996;24(5):915–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1996.tb02926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Futterman AD, Wellisch DK, Zighelboim J, Luna-Raines M, Weiner H. Psychological and immunological reactions of family members to patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation. Psychosom Med. 1996;58(5):472–80. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199609000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aslan O, Kav S, Meral C, Tekin F, Yesil H, Ozturk U, et al. Needs of lay caregivers of bone marrow transplant patients in Turkey: a multicenter study. Cancer Nurs. 2006;29(6):E1–7. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200611000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gemmill R, Cooke L, Williams AC, Grant M. Informal caregivers of hematopoietic cell transplant patients: a review and recommendations for interventions and research. Cancer nursing. 2011;34(6):E13. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31820a592d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beattie S, Lebel S. The experience of caregivers of hematological cancer patients undergoing a hematopoietic stem cell transplant: a comprehensive literature review. Psycho-Oncology. 2011;20(11):1137–50. doi: 10.1002/pon.1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stiff P, Mumby P, Miler L, Rodriguez T, Parthswarthy M, Kiley K, et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplants that utilize total body irradiation can safely be carried out entirely on an outpatient basis. Bone marrow transplantation. 2006;38(11):757–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Summers N, Dawe U, Stewart DA. A comparison of inpatient and outpatient ASCT. Bone marrow transplantation. 2000;26(4):389–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bevans M, Sternberg EM. Caregiving burden, stress, and health effects among family caregivers of adult cancer patients. Jama. 2012;307(4):398–403. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International journal of social research methodology. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akgul N, Ozdemir L. Caregiver burden among primary caregivers of patients undergoing peripheral blood stem cell transplantation: A cross sectional study. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2014;18(4):372–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laudenslager M, Simoneau T, Kilbourn K, Natvig C, Philips S, Spradley J, et al. A randomized control trial of a psychosocial intervention for caregivers of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients: effects on distress. Bone marrow transplantation. 2015 doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sabo B, McLeod D, Couban S. The experience of caring for a spouse undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: opening Pandora’s box. Cancer nursing. 2013;36(1):29–40. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31824fe223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cooke L, Grant M, Eldredge DH, Maziarz RT, Nail LM. Informal caregiving in Hematopoietic Blood and Marrow Transplant patients. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15(5):500–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bevans M, Wehrlen L, Castro K, Prince P, Shelburne N, Soeken K, et al. A problem-solving education intervention in caregivers and patients during allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Journal of health psychology. 2014;19(5):602–17. doi: 10.1177/1359105313475902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El-Jawahri AR, Traeger LN, Kuzmuk K, Eusebio JR, Vandusen HB, Shin JA, et al. Quality of life and mood of patients and family caregivers during hospitalization for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 2015;121(6):951–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jim H, Quinn G, Barata A, Cases M, Cessna J, Gonzalez B, et al. Caregivers’ quality of life after blood and marrow transplantation: a qualitative study. Bone marrow transplantation. 2014 doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Armoogum J, Richardson A, Armes J. A survey of the supportive care needs of informal caregivers of adult bone marrow transplant patients. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(4):977–86. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1615-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Langer SL, Yi JC, Storer BE, Syrjala KL. Marital adjustment, satisfaction and dissolution among hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients and spouses: a prospective, five-year longitudinal investigation. Psycho-Oncology. 2010;19(2):190–200. doi: 10.1002/pon.1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bishop MM, Beaumont JL, Hahn EA, Cella D, Andrykowski MA, Brady MJ, et al. Late effects of cancer and hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation on spouses or partners compared with survivors and survivor-matched controls. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(11):1403–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.5705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langer SL, Kelly TH, Storer BE, Hall SP, Lucas HG, Syrjala KL. Expressive talking among caregivers of hematopoietic stem cell transplant survivors: acceptability and concurrent subjective, objective, and physiologic indicators of emotion. Journal of psychosocial oncology. 2012;30(3):294–315. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2012.664255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Given B, Kozachik S, Collins C, DeVoss D, Given C. Caregiver role strain Nursing Care of Older Adult Diagnoses: Outcome and Interventions. Mosby; St Louis, MO: 2001. pp. 679–80. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Given CW, Given B, Stommel M, Collins C, King S, Franklin S. The caregiver reaction assessment (CRA) for caregivers to persons with chronic physical and mental impairments. Research in nursing & health. 1992;15(4):271–83. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770150406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stephan A, Mayer H, Guiteras AR, Meyer G. Validity, reliability, and feasibility of the German version of the Caregiver Reaction Assessment scale (G-CRA): a validation study. International Psychogeriatrics. 2013;25(10):1621–8. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213001178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Misawa T, Miyashita M, Kawa M, Abe K, Abe M, Nakayama Y, et al. Validity and reliability of the Japanese version of the Caregiver Reaction Assessment Scale (CRA-J) for community-dwelling cancer patients. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. 2009 doi: 10.1177/1049909109338480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoon SJ, Kim JS, Jung JG, Kim SS, Kim S. Modifiable factors associated with caregiver burden among family caregivers of terminally ill Korean cancer patients. Supportive care in cancer: official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2014;22(5):1243–50. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2077-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sautter JM, Tulsky JA, Johnson KS, Olsen MK, Burton-Chase AM, Hoff Lindquist J, et al. Caregiver experience during advanced chronic illness and last year of life. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2014;62(6):1082–90. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caregiving NAf. Caregiver Health. Bethesda, MD: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Network NCC. Distress management. Clinical practice guidelines. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network: JNCCN. 2003;1(3):344. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2003.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bevans M, Wehrlen L, Prachenko O, Soeken K, Zabora J, Wallen GR. Distress screening in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell (HSCT) caregivers and patients. Psycho-Oncology. 2011;20(6):615–22. doi: 10.1002/pon.1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zabora J, Buzaglo J, Kennedy V, Richards T, Schapmire T, Zebrack B, et al. Clinical perspective: Linking psychosocial care to the disease continuum in patients with multiple myeloma. Palliative and Supportive Care. 2014:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S1478951514000649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Young L. The family experience following bone marrow or blood cell transplantation. Journal of advanced nursing. 2013;69(10):2274–84. doi: 10.1111/jan.12111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wulff-Burchfield EM, Jagasia M, Savani BN. Long-term follow-up of informal caregivers after allo-SCT: a systematic review. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48(4):469–73. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]