Abstract

We test the hypothesis that Lys72 suppresses the intrinsic peroxidase activity of human cytochrome c, as observed previously for yeast iso-1-cytochrome c [McClelland et al. PNAS 111, 6648–6653 (2014)]. A 1.25 Å X-ray structure of K72A human cytochrome c shows that the mutation minimally affects structure. Guanidine hydrochloride denaturation demonstrates that the K72A mutation increases global stability by 0.5 kcal/mol. The K72A mutation also increases the apparent pKa of the alkaline transition, a measure of the stability of the heme crevice, by 0.5 units. Consistent with the increase in the apparent pKa, the rate of formation of the dominant alkaline conformer decreases and this conformer is no longer stabilized by proline isomerization. Peroxidase activity measurements show that the K72A mutation increases kcat by 1.6– to 4–fold at pH values from 7 to 10, a larger effect than for the yeast protein. X-ray structures of wild type and K72A human cytochrome c indicate that direct interactions of Lys72 with the far side of Ω-loop D, which are seen in X-ray structures of horse and yeast cytochrome c and could suppress peroxidase activity, are lacking. Instead, we propose that the larger effect of the K72A mutation on peroxidase activity of human versus yeast cytochrome c results from relief of steric interactions between the side chains at positions 72 and 81 (Ile in human versus Ala in yeast), which suppress the dynamics of Ω-loop D necessary for the intrinsic peroxidase activity of cytochrome c.

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Cytochrome c (Cytc) was first recognized for its role as an intermediary in the electron transport chain.1 More recently, the range of its functions has expanded to include scavenging of reactive oxygen species, redox-mediated protein import and most notably apoptosis.2 Initial work on the role of Cytc in apoptosis3 demonstrated that Cytc was released into the cytoplasm, where it interacts with apoptosis protease activating factor 1, Apaf-1, forming the apoptosome. The apoptosome activates caspase-9 ultimately leading to cell death. More recently, it has been shown that Cytc acts as a peroxidase when bound to the mitochondrial lipid cardiolipin (CL).4, 5 Oxidation of cardiolipin leads to release of Cytc from the inner mitochondrial membrane and appears to aid in permeabilization of the outer mitochondrial membrane. Thus, the peroxidase activity is believed to be the earliest signal in the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis.5

When Cytc binds to CL-containing membranes it is known to lead to loss of heme-Met80 ligation.5–7 Thus, it seems likely that the highly conserved surface loop, Ω-loop D, that encompasses residues 70 to 858, 9 may be involved in mediating peroxidase activity. To act as a signaling agent, it is essential that the basal peroxidase activity of Cytc be minimal so that it can act as a true on/off switch. In the current work, we aim to understand how the sequence of the highly-conserved Ω-loop D is designed to suppress peroxidase activity. In particular, we investigate the role of the absolutely conserved lysine at position 72 in modulating the basal peroxidase activity of human Cytc (Hu Cytc). In the X-ray structures of yeast iso-1-cytochrome c (iso-1-Cytc)10 and horse Cytc,11 this residue lies across Ω-loop D making steric or hydrogen-bonding contacts with residues 80 to 82 on the opposite side of the loop. These interactions might stabilize Ω-loop D, which positions Met80 for heme binding, limiting the basal peroxidase activity of Cytc.

Previous work with iso-1-Cytc, which contains a trimethylated lysine at position 72 (tmK72),10 showed that when an alanine is introduced at position 72 (tmK72A variant), an alternate conformer of the protein with Met80 replaced by hydroxide in the 6th coordination site of the heme can form.12 An increase in peroxidase activity was also observed for this variant of iso-1-Cytc. Studies on the kinetics and thermodynamics of a His79-mediated alkaline transition with iso-1-Cytc showed that replacement of tmK72 with alanine destabilizes the native conformer relative to the alkaline conformer and increases the rate of formation of the alkaline conformer.13, 14 These kinetic and thermodynamic results are consistent with the enhanced peroxidase activity of the tmK72A variant of iso-1-Cytc. However, a K72G variant of horse Cytc changes neither the midpoint pH for the alkaline conformational transition nor the stability of Ω-loop D,15 indicating that this residue may not affect the peroxidase activity of mammalian cytochromes c.

In the current work, we probe the effect of a K72A mutation on the properties of Hu Cytc. We show that the native structure is unaffected by this mutation. However, we observe significant perturbation of the kinetics and thermodynamics of the alkaline transition. We also show a significant enhancement in peroxidase activity of K72A Hu Cytc relative to wild type (WT) Hu Cytc.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Preparation of Human K72A Cytochrome c

The K72A variant of Hu Cytc was prepared with site-directed mutagenesis using the pBTR(HumanCc) plasmid provided by the laboratory of Gary Pielak at the University of North Carolina.16 pBTR(HumanCc) is derived from the pBTR1 plasmid17, 18 through replacement of the yeast iso-1-Cytc gene (CYC1) with a synthetic human cytochrome c gene.16, 19 pBTR(HumanCc) like pBTR1 co-expresses the yeast heme lyase (CYC3) and uses it to covalently attach heme to the CSQCH heme recognition sequence of Hu Cytc. Double-stranded pBTR(HumanCc) DNA was prepared using BL21-Gold(DE3) (Agilent Technologies) competent Escherichia coli cells and used as a template for site-directed mutagenesis with the Agilent Technologies QuikChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit. The oligonucleotide, K72A: d(GGAATACCTCGAGAACCCGGCGAAATACATCCCGGGCACG) and its reverse complement, K72A-r were used for mutagenesis. The mutated DNA was transformed into TG-1 E. coli cells. Individual colonies were then grown in L-broth with Ampicillin (10 mL L-broth with 10 μL of 100 mg/mL Ampicillin) at 37 °C overnight. The DNA was extracted and purified with the Promega Wizard® Plus Miniprep DNA Purification System. The sequence was confirmed with an ABI 3130 Genetic Analyzer at the Genomics Core Facility at the University of Montana.

Expression of Human Cytochrome c

WT and K72A Hu Cytc were expressed from the pBTR(HumanCc) plasmid after transformation into Ultra BL21 (DE3) E. coli competent cells (EdgeBio, Gaithersburg, MD) using the manufacturers protocol. Transformed cells were grown on 2xYT bacterial media, as described previously,20 except with the addition of 100 μL of antifoam per liter of culture. On average, a 1 L culture yielded 4.7 g of pelleted cells.

Protein extraction and purification were carried out as described, previously.14, 20–22 In brief, cells were lysed with French Pressure Cell followed by precipitation of contaminating proteins with 50% ammonium sulfate. After CM-sepharose cation exchange chromatography, protein was exchanged into 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7 by centrifuge ultrafiltration, flash frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80 °C until used. Prior to experiments, WT and K72A Hu Cytc were purified by HPLC using a BioRad UNO S6 column, as previously decribed.20

Purified proteins were characterized by MALDI-ToF mass spectrometry using a Bruker microflex mass spectrometer. For WT Hu Cytc; 12,234.78 m/z (expected: 12,234.03 m/z). For K72A Hu Cytc, 12175.17 m/z (expected: 12,176.94 m/z)

Crystallization and Structure Determination of Human K72A Cytc

K72A Hu Cytc was oxidized with K3[Fe(CN)6], followed by separation from the oxidizing agent and exchanged into 50 mM Tris pH 7 using Sephadex G-25 chromatography. It was then concentrated to ~16.5 mg/ml using centrifuge ultrafiltration (Amicon Ultra-4 10,000 MWCO). Screening for crystallization conditions was carried out using the JCSG core I, JCSG core II, JCSG core III, JCSG core IV, PEGS, PEGS II, Wizard classic 1&2, Wizard classic 3&4, Classic, Classic II, and Classic Lite commercial screening suites at 20 °C. The ratio of protein to reservoir solution in the drops in the 96 well sitting drop screening plates was 1:1. We obtained initial crystals from JCSG core I, well A2, which has a 0.1 M Bicine pH 8.5, 20%(w/v) PEG 6000 reservoir solution. Additional vapor diffusion crystallization experiments were set up in a 24-well VDX plate by expanding upon the pH and precipitant concentration of this initial condition. After 4 days to 2 weeks of equilibration at 20 °C, crystals were obtained from a drop containing 1 μL of protein and 1 μL of 25% PEG 6000, 0.1 M Tris pH 8, which diffracted to 1.8 Å at SSRL beamline 14-1. Further trials in the presence of sodium dodecyl sarcosine as an additive at 4.16 mM final concentration (60 mM stock) with a reservoir solution containing 30% PEG 3350 and 0.1 M sodium citrate, pH 6.4 and protein at 17.2 mg/mL (mixed 0.14:0.93:0.93) yielded crystals diffracting to 1.25 Å resolution in the P 21 space group. All crystals were cryoprotected with 20% glycerol and flash frozen in liquid N2 for data collection.

The X-ray diffraction dataset was collected under cryogenic conditions at 100 K at the SMB beamline 9-2 of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) using a Pilatus 6 M detector. Diffraction data were processed using HKL2000.23 The initial electron density map was determined using phases obtained with the molecular replacement method using Phaser, incorporated in the PHENIX software suite,24 and the coordinates of the wild-type human Cytc structure (PDB ID: 3ZCF)25 as a search model. The initial model was built into a continuous electron density map and subsequently refined using PHENIX. The structure model was further refined to 1.25 Å resolution by multiple rounds of manual model rebuilding with COOT26 and restrained refinement with PHENIX using 5 % of reflections for calculation of Rfree. Data collection and refinement statistics of the final model are summarized in Table 1. The coordinates and structure factors for K72A Hu Cytc have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 5TY3).

Table 1.

X-ray crystallography and data collection and refinement statistics.

| PDB ID | 5TY3 |

| Beamline | SSRL SMB 9-2 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.07 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 25.00-1.25 (1.29-1.25)* |

| Space group | P 21 |

| Unit cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 56.8, 37.9, 60.3 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 116.8, 90 |

| Total reflections | 1539904 |

| Unique reflections | 62478 (5985)* |

| Redundancy | 6.5 (5.3)* |

| Completeness (%) | 97.8 (93.6)* |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 24.5 (6.1)* |

| Wilson B-factor | 10.85 |

| Rsym† | 0.07 (0.27)* |

|

| |

| Refinement | |

|

| |

| Rwork§ | 0.147 (0.194)* |

| Rfree § | 0.166 (0.201)* |

| Number of total atoms | 2204 |

| protein | 1660 |

| ligands | 96 |

| solvent | 448 |

| Total protein residues | 210 |

| RMS (bonds, Å) | 0.017 |

| RMS (angles, °) | 1.38 |

| Ramachandran favored (%)†† | 98 |

| Rotamer outliers (%)†† | 0.2 |

| Average B-factor | 17.69 |

| macromolecules | 14.89 |

| ligands | 11.44 |

| solvent | 29.40 |

Data for highest resolution shell are given in brackets.

Rsym =Σhkl Σi | Ii (hkl)- áI (hkl)ñ|/ Σhkl Σi Ii (hkl) where Ii (hkl) is the ith observation of the intensity of the reflection hkl.

Rwork =Σhkl || Fobs|-|Fcalc||/ Σhkl |Fobs|, where Fobs and Fcalc are the observed and calculated structure-factor amplitudes for each reflection hkl. Rfree was calculated with 5% of the diffraction data that were selected randomly and excluded from refinement.

Calculated using MolProbity.28

Global Unfolding by Guanidine Hydrochloride Denaturation

Global unfolding thermodynamics of WT and K72A Hu Cytc were determined by guanidine hydrochloride (GdnHCl) denaturation monitored by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy. Protein was oxidized with potassium ferricyanide and separated from oxidant by G-25 size exclusion chromatography in CD buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 40 mM NaCl). Concentration of GdnHCl stock solutions were determined using the empirical equation of Nozaki for the change in refractive index relative to the background buffer.27

GdnHCl unfolding titrations were carried out with an Applied Photophysics Chirascan CD Spectrophotometer coupled to a Hamilton Microlab 500 Titrator. The change in ellipticity was monitored at 222 nm using 250 nm as background, θ222corr (θ222nm - θ250nm). The protein concentration was 4 μM. θ222corr versus GdnHCl concentration denaturation curves were fit to eq 1 with SigmaPlot v. 13 (Systat Software, Inc.), which assumes two state unfolding and a linear dependence of the free energy of unfolding, ΔGu, on GdnHCl concentration.29, 30 Native and denatured state baselines were also varied linearly with GdnHCl concentration. In eq 1, θN and

| (1) |

mN are the intercept and the slope of the native state baseline, θD and mD are the intercept and the slope of the denatured state baseline, m is slope of ΔGu with respect to GdnHCl concentration and ΔGu∘′(H2O) is the free energy of unfolding extrapolated to 0 M GdnHCl.

Measurement of the Alkaline Transition by pH Titration

The alkaline conformational transition of WT and K72A Hu Cytc was monitored with a Beckman DU800 spectrophotometer using absorbance at 695 nm, A695, a weak absorbance band which reports on the Met80-heme ligation of the native state of oxidized Cytc.31 The absorbance data were corrected for baseline drift using absorbance at 750 nm, A750, as baseline (A695corr = A695 – A750) and then converted to extinction coefficient, ε695corr, by dividing by concentration. Titrations were monitored at room temperature (22 ± 3 °C) at 175 – 200 μM protein concentration in 100 mM NaCl. Titrations were carried out by adding equal amounts of an appropriate concentration of NaOH and a 2x protein stock (350 – 400 μM protein in 200 mM NaCl) to keep protein concentration constant throughout the experiment.32, 33 Plots of ε695corr versus pH were used to determine the apparent pKa (pKapp) by fitting the data to eq 2 (SigmaPlot v. 13), a modified form of the Henderson-Hasselbalch

| (2) |

equation that evaluates the number of protons, n, linked to the alkaline conformational transition. In eq 2, εN and εAlk are the corrected extinction coefficients at 695 nm of the native and alkaline conformers, respectively.

pH Jump Stopped-flow Kinetic Measurements

Kinetics of the alkaline conformation transition were monitored via pH jump stopped-flow experiments carried out with an Applied Photophysics SX20 stopped-flow apparatus at 25 °C. The conformational transition was monitored at the 406 nm in the heme Soret region. Oxidized protein (Fe(III)-heme) was separated from ferricyanide using a G25 column equilibrated to and run with 0.1 M NaCl. The solution was adjusted to 20 μM protein concentration and pH 6 for upward pH jumps and to near pH 10 for downward pH jumps. 1:1 mixing with 0.1 M NaCl containing 20 mM buffer yields a final protein concentration of 10 μM in 10 mM buffer, 0.1 M NaCl. Buffers used for pH jump stopped-flow were: MES, pH 5.5 – 6.5; NaH2PO4, pH 6.75 – 7.5; Tris, pH 7.75 – 8.75; Boric Acid, pH 9.0 – 10.0; CAPS, pH 10.25 – 11.0. Samples were taken from the stopped-flow waste line and pH was measured directly after mixing experiments at each pH. Data were fit to a one to four exponential equation, as appropriate.

Peroxidase Activity Measurements

Peroxidase activity was measured with the colorimetric reagent, guaiacol, using previously reported conditions and procedures.12, 34 The reaction was monitored using an Applied Photophysics SX20 stopped-flow apparatus at 25 °C. The formation of tetraguaiacol from guaiacol and H2O2 in the presence of Cytc is monitored at 470 nm. A 4 μM Cytc solution in 50 mM buffer was mixed with guaiacol in 50 mM buffer at 4-fold the desired final concentration to produce a 2 μM Cytc and 2-fold concentrated guaiacol stock in 50 mM buffer. This solution was mixed 1:1 with 100 mM H2O2 in 50 mM buffer yielding a final solution containing 1 μM Cytc, 50 mM H2O2 and guaiacol at the desired concentration in 50 mM buffer. Concentration was determined using the extinction coefficients of H2O2 (ε240 = 41.5 M−1 cm−1, the average of published values)35, 36 and guaiacol (ε274 = 2,150 M−1 cm−1).37 Buffers used for peroxidase experiments were the same as those used in pH-Jump experiments. Final guaiacol concentrations used were 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 40, 50, 60, 80, 100, 150 and 200 μM.

Data were fit using SigmaPlot v. 13. The segment of the A470 versus time data with the greatest slope following the initial lag phase was used to obtain initial velocity, v, at each guaiacol concentration. The data were fit to a linear equation and the slope from five repeats was averaged. The slope (dA470/dt) was divided by the extinction coefficient of tetraguaiacol at 470 nm (ε470 = 26.6 mM−1cm−1)38 and multiplied by 4 to produce the initial rate of guaiacol consumption, v. The initial rate, v, was divided by cytochrome c concentration, plotted against guaiacol concentration and fit with eq 3 to obtain Km and kcat values.

| (3) |

RESULTS

Structure of K72A Human Cytc

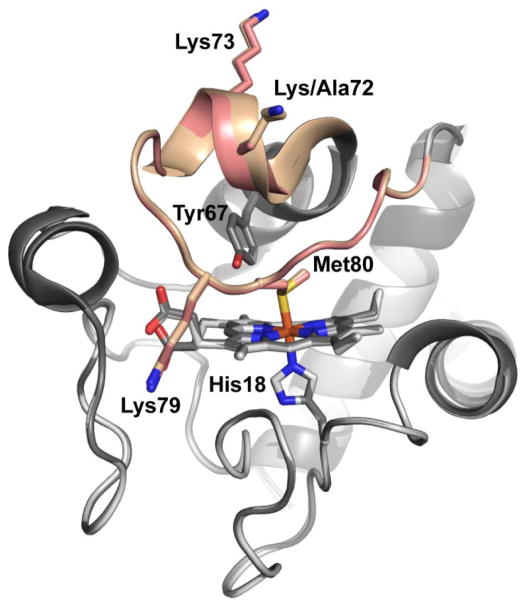

Crystals of K72A Hu Cytc were prepared in the absence and presence of sodium dodecyl sarcosine as an additive. In both cases, the K72A Hu Cytc crystallized in the P 21 space group. The crystal obtained in the presence of the additive diffracted to a resolution of 1.25 Å (Table 1). A high quality structural model with Rwork/Rfree of 0.15/0.17 (Table 1) was obtained. Figure 1 shows an overlay of the K72A Hu Cytc structure with that of WT Hu Cytc. The structures are very similar. An all atom alignment of the K72A Hu Cytc structure with the WT Hu Cytc crystal structure (PDB ID: 3ZCF;25 PyMol align function using chain A of each structure) yields an RMSD of 0.18 Å. The methyl side chain of Ala72 of K72A Hu Cytc is in the same position as the β-carbon of Lys72 of WT Hu Cytc (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overlay of the structures of K72A Hu Cytc (PDB ID: 5TY3) and WT Hu Cytc (PDB ID: 3ZCF).25 The K72A variant is shown in light gray and WT Hu Cytc is shown in dark gray. The heme-crevice loop (Ω-loop D, residues 70–85) is highlighted in salmon for the K72A variant and tan for WT Hu Cytc. The heme and its environment, Met80, His18, and Tyr 67, are shown as stick models. The three lysine residues in Ω-loop D (Lys/Ala72, Lys73 and Lys79) are also shown as stick models.

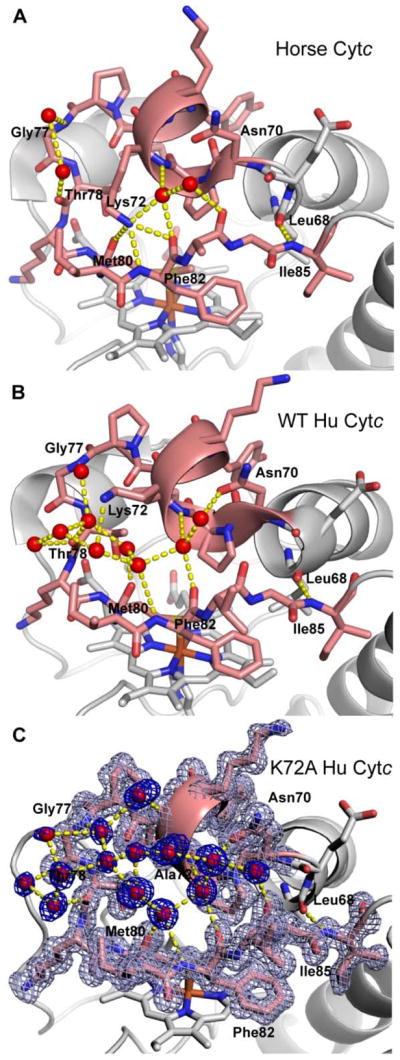

Lys72 of horse Cytc11 and trimethyllysine72 (tmK72) of yeast iso-1-Cytc10 both lie across Ω-loop D making contacts with residues 80 to 82 on the far side of the loop. In the case of horse Cytc, Lys72 makes three hydrogen bonds to backbone atoms of Met80 and Phe82 (Figure 2A). In our previous work on a K72A variant of iso-1-Cytc,12 we proposed that removal of this cross loop interaction by replacement of tmK72 with alanine labilized Ω-loop D permitting enhanced peroxidase activity. Thus, it seemed likely that a similar phenomenon might be operative for Hu Cytc. However, in the structure of WT Hu Cytc,25 Lys72 does not make direct contacts with the backbone atoms of Met80 and Phe82 as seen for horse Cytc. In chain A of the WT Hu Cytc crystal structure, Lys72 makes water-mediated contacts with the backbone atoms of Thr78, Met80 and Phe82 (Figure 2B). In our K72A Hu Cytc crystal structure, the position of the ε-NH2 group of Lys72 in chain A of the WT structure is occupied by a water molecule (Figure 2C). However, in the other three molecules in the asymmetric unit of the WT Hu Cytc crystal structure, the hydrogen bond network around Lys72 does not lead to cross loop contacts (Figure S1). Instead, the water-mediated cross loop interactions in these molecules of WT Hu Cytc are similar to those in the two molecules in the asymmetric units of our K72A Hu Cytc structure (Figure 2C and Figure S2). In particular, irrespective of the presence of lysine at position 72, there is always a hydrogen bond between the carbonyl of Leu68 and the amide NH of Ile 85 at the neck of Ω-loop D (Figures 2, S1 and S2). Similarly, there is always a water-mediated hydrogen bond between the amide NH of residue 72 and the carbonyl of Phe82, which is often further supported by a water-mediated hydrogen bond to the side chain of Asn70 (Figures 2, S1 and S2). In many cases, the water-mediated hydrogen bond network extends the entire length of Ω-loop D.

Figure 2.

Hydrogen bond network across Ω-loop D. (A) Horse Cytc (PDB ID: 1HRC) (B) WT Hu Cytc (PDB ID: 3ZCF, chain A) and (C) K72A Hu Cytc (PDB ID: 5TY3, chain A). Ω-loop D is colored salmon. Residues in the H-bond network are labeled. Waters are shown as red spheres and hydrogen bonds as yellow dashed lines. In part (C) the 2mFo-Fc electron density map for Ω-loop D (light blue) and for the waters (dark blue) is contoured at 1.2σ.

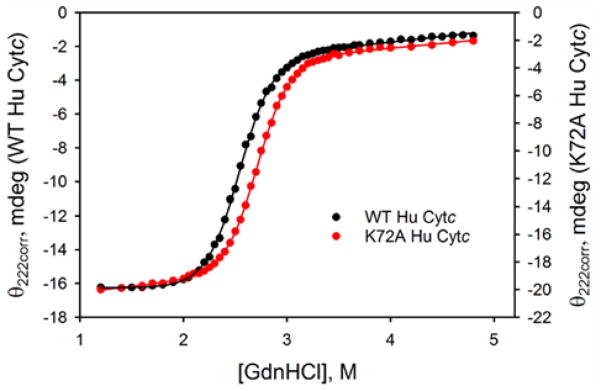

Global Unfolding of Human Cytc Variants

Global unfolding thermodynamics of WT20 and K72A Hu Cytc were monitored by CD at 25 °C and pH 7.5 with the use of GdnHCl as denaturant. Figure 3 compares the denaturation curves, θ222corr versus GdnHCl concentration, for the two proteins. The unfolding curve for the K72A variant is shifted to slightly higher GdnHCl concentration indicating a small stabilization relative to WT Hu Cytc. To fit the K72A Hu Cytc data, a sloping native state baseline was necessary (eq 1, Experimental Procedures). For consistency, we refit our previously published WT Hu Cytc data,20 which had originally been fit with a constant native state baseline. Thermodynamic parameters from fits to a two-state model are given in Table 2. Within error, the denaturant m-value is unchanged by the K72A mutation. However, the K72A mutation increases the unfolding midpoint, Cm, by ~0.2 M and the stability, ΔGu∘′(H2O), by ~ 0.5 kcal/mol. Our previously reported stability parameters for Hu WT Cytc are similar to those in Table 2.20 Cm is unchanged, however, m increases by ~ 0.2 kcal mol−1 M−1 when a sloping native state baseline is used, which leads to an increase of ~0.5 kcal/mol in the stability of WT Hu Cytc.

Figure 3.

Denaturation curves of WT HuCytc (black) and K72A Hu Cytc (red) are shown as plots of corrected ellipticity at 222 nm, θ222corr, versus GdnHCl concentration. Solid curves are fits to eq 1 in Experimental Procedures. Parameters obtained from the fits are given in Table 2. Experiments were performed at 25 °C in CD Buffer (20 mM Tris, 40 mM NaCl, pH 7.5) at 4 7mu;M protein concentration. Previously reported data for WT Hu Cytc20 is refit here.

Table 2.

Thermodynamic parameters for global unfolding of WT and K72A Hu Cytc at 25 °C and pH 7.5.

| Variant | m, kcal mol−1 M−1 | ΔGu∘′(H2O), kcal mol−1 | Cm, M |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 3.71 ± 0.05 | 9.46 ± 0.11 | 2.55 ± 0.01 |

| K72A | 3.64 ± 0.15 | 10.01 ± 0.30 | 2.75 ± 0.03 |

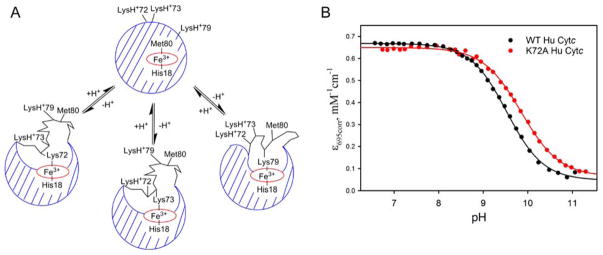

Local Unfolding via the Alkaline Conformational Transition

The local unfolding thermodynamics for the alkaline conformational transition of WT and K72A Hu Cytc were determined by pH titration, monitored at 695 nm to observe the loss of Met80-heme iron ligation31 when a lysine from Ω-loop D binds to the heme. A schematic representation of the human alkaline conformational transition is shown in Figure 4A. Lysines 72, 73 and 79 could all potentially bind to the heme. However, while all three lysines contribute to the alkaline conformer of yeast iso-1-Cytc expressed from E. coli,18 NMR studies suggest only two distinguishable alkaline conformers exist for horse Cytc.39 Mutational analysis indicates that lysines 73 and 79 contribute to the alkaline transition of horse Cytc, but that Lys72 does not.15 Representative pH titration data for K72A Hu Cytc are compared to previously reported data for WT Hu Cytc20 in Figure 4B. Within error, ε695corr of the native form of Hu Cytc (below pH 8) is unaffected by the K72A mutation indicating minimal mutation-induced perturbation to Met80-heme ligation in the native state.40, 41 The K72A mutation, however, does cause a shift of the alkaline transition of Hu Cytc to higher pH. Fits of the K72A Hu Cytc data to eq 2 (Experimental Procedures) yield pKapp = 10.0 ± 0.1 for the K72A variant, which is ~0.5 units higher than pKapp = 9.54 ± 0.03 for WT Hu Cytc measured under the same conditions.20 The number of protons linked to the alkaline transition is near 1 for both WT Hu Cytc (n = 1.03 ± 0.02)20 and K72A Hu Cytc (n = 0.98 ± 0.06).

Figure 4.

(A) Schematic representation of the alkaline conformational transition for Hu Cytc showing all three possible alkaline conformers with lysines from Ω-loop D as alkaline state ligands. (B) Plots of ε695corr versus pH for the alkaline transition for WT (black)20 and K72A (red) Hu Cytc. Data were collected at room temperature (22 ± 3°C) in 0.1 M NaCl solution at protein concentrations of 200 μM and 175.5 μM for the WT Hu Cytc and K72A Hu Cytc, respectively. Solid lines are fits to eq 2 in Experimental Procedures.

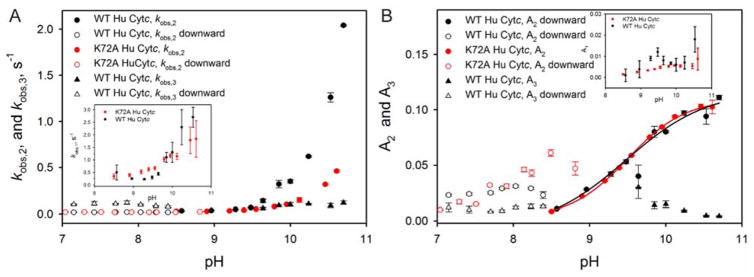

Kinetics of the Alkaline Conformational Transition

For WT Hu Cytc, the upward pH jump kinetic traces are best fit to a two exponential equation below pH 9.5, a three exponential equation from pH 9.6 to pH 10 and a four exponential equation above pH 10 (Figure S3 and Table S1 in the Supporting Information). The rate constant for the phase which emerges above pH 9.5, kobs,3, is near 0.1 s−1, typical for proline isomerization (Figure 5A). The amplitude of this phase, A3, is largest at the pH where it can first be observed near the midpoint of the alkaline conformational transition of WT Hu Cytc (Figure 5B). As pH increases and the alkaline conformer fully populates, the amplitude of this phase decreases. This amplitude behavior is characteristic of proline isomerization.42 Above pH 10, a kinetic phase, kobs,4, with a rate constant of 20 – 30 s−1 begins to be observable. Fast phases in the 20 – 100 s−1 range are usually observed above pH 10 in the kinetics of the alkaline transition of Cytc.43–48 This fast phase has been assigned to a transient intermediate, which is thought to have either a weakened heme-Met80 bond or a hydroxide replacing Met80 as a heme ligand.45, 47 The intermediate has also been suggested to be due to a conformational change involving opening of the least stable substructure of Cytc.44

Figure 5.

(A) Rate constants as a function of pH for the alkaline conformational transition of WT (black symbols) and K72A Hu Cytc (red symbols). Data for a fast phase, kobs,1, are shown in the inset. Data for two slower phases, kobs,2 and kobs,3, are shown as circles and triangles, respectively, in the main panel. (B) Amplitudes as a function of pH for the alkaline conformational transition of WT (black symbols) and K72A Hu Cytc (red symbols). Data for the fast phase amplitude, A1, are shown in the inset. Two slower phases, A2 and A3, are shown as circles and triangles, respectively, in the main panel. The solid curves are fits of the A2 versus pH data for WT (black) and K72A (red) Hu Cytc to the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation (eq 2 in Experimental Procedures). Rate constants and amplitudes obtained from upward pH jump experiments are shown as solid symbols and for downward pH jump experiments as open symbols. Upward jumps had an initial pH of 6.0 and downward jumps had an initial pH of near 10. Data were acquired at 25 °C. Final buffers after mixing were 10 mM with 100 mM NaCl. Final protein concentration was 10 μM. Error bars are standard deviations. Rates constants are collected in Tables S1 to S4 of the Supporting Information.

For K72A Hu Cytc a two exponential fit is sufficient to fit the upward pH jump kinetics traces up to pH 10 (Figure S3 and Table S3 in the Supporting Information). No slow proline isomerization phase is evident as for WT Hu Cytc. However, as with WT Hu Cytc, a fast phase with a rate constant near 20 s−1 is observed above pH 10 (Table S3 of the Supporting Information).

Rate constants and amplitudes for both upward and downward pH jump experiments are shown in Figure 5 for WT and K72A Hu Cytc. The pH dependencies of both kobs,1 and kobs,2 are qualitatively consistent with the behavior expected for the standard mechanism for the alkaline conformational transition for both WT and K72A Hu Cytc. This mechanism involves a rapid deprotonation equilibrium (KH) followed by a conformational change with forward and backward rate constants, kf and kb, respectively (eq 4).49 Thus, at low pH kobs is equal to kb. kobs then

| (4) |

increases when an ionizable group is deprotonated (KH or pKH) ultimately leveling off at kb + kf, if sufficiently high pH is achieved. While the pH dependence of kobs,1 and kobs,2 are qualitatively consistent with eq 4, the upper limit of neither kobs,1 nor kobs,2 is sufficiently well-defined to allow reliable fits to eq 4 to extract kf and KH.

The amplitude data show that the phase corresponding to kobs,2 is the dominant alkaline conformer for both WT and K72A Hu Cytc (Figure 5B). The pH dependence of A2 is similar for both proteins. At low pH, where kobs,2 should equal kb, kobs,2 obtained from downward pH jump experiments is near 0.02 – 0.03 s−1 for both WT and K72A Hu Cytc (Tables S2 and S4). The approximately 50 second timescale of kobs,2 at low pH for both WT and K72A Hu Cytc is typical for lysine ligation in the alkaline state.50 As pH increases, kobs,2 increases more rapidly for WT than for K72A Hu Cytc. The magnitude of kobs,1 is ~0.3 s−1 near pH 8.5 (Tables S1 and S3), about 10-fold larger than kobs,2. The magnitude of kobs,1 increases slowly as pH increases (Figure 5A inset), but the phase is a minor contributor to overall amplitude at all pH values for both WT and K72A Hu Cytc (Figure 5B inset) and is not observable in downward pH jump experiments for either protein. At pH 10.7, kobs,1 and kobs,2 become indistinguishable for WT Hu Cytc (Table S1 of the Supporting Information). For WT Hu Cytc, kobs,3 is also observable in downward pH jump experiments. As in upwards pH jump experiments, it has a value near 0.1 s−1, consistent with proline isomerization.

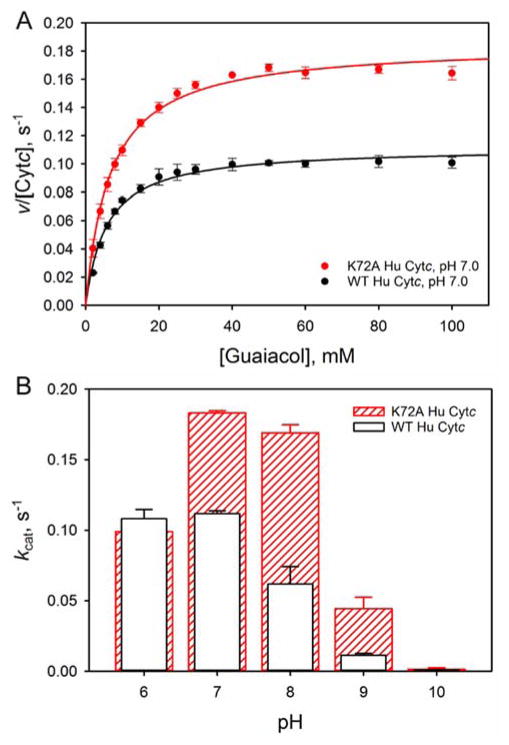

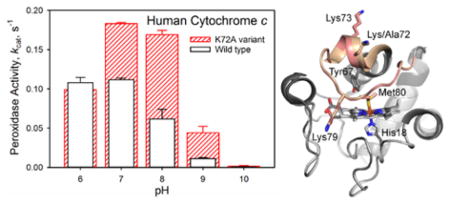

Peroxidase Activity

In the early stages of apoptosis, Cytc acts as a peroxidase in conjunction with binding to the mitochondrial membrane lipid cardiolipin.5 In previous work, we have shown that a K72A mutation to yeast iso-1-Cytc enhances peroxidase activity and provides access to alternate conformers of Cytc.12 Thus, it is of interest to determine if a similar effect occurs for Hu Cytc. Peroxidase activity of WT and K72A Hu Cytc was measured by monitoring the formation of tetraguaiacol from guaiacol at 470 nm in the presence of H2O2. Michealis-Menten plots with respect to guaiacol concentration were generated to permit extraction of kcat and Km across the pH range 6 to 10. It is evident in Figure 6A that the K72A mutation causes a significant increase in kcat at pH 7. Similar behavior is observed at pH 8 – 10, while kcat is within error the same at pH 6 for WT and K72A Hu Cytc (Figure 6B, Table S5). The Km values with respect to guaiacol concentration are not strongly affected by the mutation (Table S5).

Figure 6.

Peroxidase activity of WT (black) and K72A (red) Hu Cytc. (A) Michaelis-Menten plots for WT (solid black circles) and K72A (solid red circles) Hu Cytc at pH 7. The solid curves are fits to eq 3 (Experimental Procedures). Data were acquired at 25 °C in 10 mM buffer and 100 mM NaCl. (B) kcat versus pH for WT (white bars black outline) and K72A (red outlined bars with slashes) Hu Cytc. Error bars are the standard deviation from three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Effect of the K72A Mutation on Structure and Stability of Hu Cytc

The native state structure of Hu Cytc is essentially unaffected by the K72A mutation (Figure 1). Given that Lys72 is located on the surface of Hu Cytc only modest effects on stability would be expected.51 We observe a small shift in the midpoint for GdnHCl unfolding, Cm, from 2.55 ± 0.01 M for WT to 2.75 ± 0.03 M for K72A Hu Cytc. Given that the denaturant m-value is unchanged by the K72A mutation, the result is a small increase in global stability,Δ G∘′(H2O), of ~0.5 kcal/mol.

Effect of the K72A mutation on the Alkaline Transition of Hu Cytc

Our data show that the K72A mutation causes the pKapp for the alkaline transition to shift ~0.5 units to higher pH, consistent with a destabilization of the alkaline state relative to the native state of Hu Cytc. The ~0.5 kcal/mol stabilization of the native state of HuCytc by the K72A mutation suggests that stabilization of the native state by this mutation could contribute to the higher pKapp.

In previous work on the kinetics of the alkaline transition of WT Hu Cytc, a single exponential equation was used to fit the pH jump kinetic traces.52 In our hands, we observe significantly improved fits of the pH jump kinetic traces for the alkaline transition to a double exponential function at mildly alkaline pH and 3 and 4 exponential equations above pH 9.5 (Figure S3). The kobs,1 and kobs,2 phases show behavior consistent with the standard model for the alkaline transition (eq 4) for both WT and K72A Hu Cytc. Both these phases have similar amplitude behavior for both WT and K72A Hu Cytc, too. Thus, these data indicate that Lys72 is not an important ligand in the alkaline transition of Hu Cytc as observed in previous studies on a K72G variant of horse Cytc.31 There are two effects of the K72A mutation on the kinetics of the alkaline transition. The rate of formation of the dominant Lys-mediated alkaline conformer increases more slowly above pH 9.5 and the proline isomerization phase coupled to formation of the dominant alkaline conformer is eliminated. Given our previous observation that a proline isomerization phase is coupled to formation of a His73-heme alkaline conformer of yeast iso-1-Cytc,53 we tentatively assign the dominant alkaline conformer (A2, kobs,2) to the Lys73-mediated alkaline conformer of Hu Cytc.

Given that the K72A mutation increases the global stability of Hu Cytc (Table 2), increases the pKapp of the alkaline transition (Figure 4) and decreases the rate of formation of the dominant alkaline conformer (kobs,2), the simplest explanation is that this mutation stabilizes the native state relative to the alkaline state. However, the loss of proline isomerization in the alkaline state may cause some destabilization of this state.

Effect of K72A Mutation on Peroxidase Activity of Hu Cytc

The primary impetus for this work was to determine if the enhancement of peroxidase activity observed for yeast iso-1-Cytc upon introduction of the K72A mutation also occurs with Hu Cytc. The pH dependence of kcat for WT versus K72A Hu Cytc is similar to our previous observations for yeast iso-1-Cytc. At pH 6, kcat is identical for the WT proteins and the K72A variants of both yeast iso-1-Cytc and Hu Cytc. However, at pH 7 and above kcat is significantly higher for the K72A variants of yeast and human Cytc. At pH 7, the K72A mutation leads to a 30% increase in kcat for yeast iso-1-Cytc, whereas for Hu Cytc a 60% increase is observed. At pH 8, a two-fold increase in kcat results from the K72A mutation for yeast iso-1-Cytc, whereas a three-fold increase is observed for Hu Cytc. Thus, Lys72 is also important in suppressing the basal peroxidase activity of Hu Cytc. However, the percent increase in activity is larger for Hu Cytc than for yeast iso-1-Cytc.

The decrease in kcat as pH increases (Figure 6B) is also observed for horse Cytc38, 54 and has been attributed to replacement of Met80 by a lysine, which is a stronger ligand for Fe(III) than methionine. At pH 7 and 8, the alkaline conformer for both WT and K72A Hu Cytc is poorly populated (Figure 4) and thus is not a significant factor in the pH regime where the largest enhancement of peroxidase activity is observed for the K72A variant relative to WT Hu Cytc (Figure 6). Based on the horse Cytc (Figure 2A) and yeast iso-1-Cytc structure, we have suggested that Lys72 may act like a brace across Ω-loop D, stabilizing it against opening and allowing reactive oxygen species like hydrogen peroxide to bind to the heme iron.12 The human Cytc structure indicates that the direct interaction of Lys72 with the other side of Ω-loop D may not be the primary reason that Lys72 inhibits the intrinsic peroxidase activity of Hu Cytc. In fact, the water-mediated hydrogen bond network that connects one-side of Ω-loop D with the other is similar in WT and K72A Hu Cytc (Figures 2, S1 and S2). In our structure of K72A iso-1-Cytc,12 where Met80 ligation to the heme is replaced by a hydroxide, the smaller side chain at position 72 appears to be essential for allowing the backbone movement necessary for expulsion of Met80 from the heme crevice. Thus, the primary function of Lys72 may be to sterically inhibit this backbone motion, suggesting that any amino acid of sufficient steric size at position 72 would reduce the intrinsic peroxidase activity of Cytc. Our K72A iso-1-Cytc structure shows that the side chain of residue 81 must move toward Lys72 to allow expulsion of Met80 from the heme crevice.12 Yeast iso-1-Cytc has alanine at this position and Hu Cytc has isoleucine at this position. The larger percent increase in kcat for the K72A mutation for Hu Cytc versus yeast iso-1-Cytc may result from the greater steric congestion of isoleucine at position 81 of Hu Cytc versus alanine at this position for yeast iso-1-Cytc.

The increased peroxidase activity of K72A Hu Cytc is perhaps surprising given that the K72A mutation increases the stability of the native state relative to the alkaline state (Figure 4) and appears to slow the formation of the alkaline conformer (Figure 5A). The structural fluctuation that is enhanced by the K72A mutation and allows access of peroxide does not appear to require the full cooperative structural rearrangement of the alkaline transition. Our X-ray structure of K72A iso-1-Cytc shows that a very modest structural rearrangement is sufficient to allow loss of Met80 ligation to the heme.12 Segments of all of the substructures of horse Cytc are known to undergo hydrogen-deuterium (HD) exchange by local structural fluctuations that are more rapid than the full cooperative unfolding of the substructure. Available data indicate that Lys72 and Ile81 are prone to non-cooperative fluctuations that allow exchange at lower free energy than the full cooperative unfolding of the Ω-loop, which positions the Met80 heme ligand.55, 56 Thus, it seems plausible that the K72A mutation might increase local flexibility enhancing access of peroxide to the heme and thus increasing kcat. At the same time, this increase in local flexibility could entropically stabilize the native state of the protein leading to the observed effects on both global (Figure 3) and local (Figure 4) stability.

Comparison with Peroxidase Activity in other Variants and other Species

To keep the current results in context, we note that the basal peroxidase activity of WT Hu Cytc is about 15% less than horse Cytc at pH 7 under the same conditions. The K72A mutation leads to a 1.6-fold increase in kcat, whereas formation of a domain-swapped dimer of horse Cytc produces a 5-fold increase in kcat.34 Both mammalian proteins have a kcat that is 20-fold less than that of yeast iso-1-Cytc. Thus, while Lys72 plays a role in modulating peroxidase activity in both yeast and mammalian cytochromes c, evolution of other segments of the primary structure of cytochrome c are responsible for the substantial suppression of the basal peroxidase activity of Cytc in higher eukaryotes.

There has also been considerable interest in naturally occurring variants of cytochrome c, G41S,57 Y48H58 and A51V,59 which have enhanced apoptotic activity and are implicated in thrombocytopenia. The physical and biochemical properties of the G41S, G41A and G41T variants have been extensively studied.25, 60–64 All three variants show increased peroxidase activity61 that correlates with the stability of the heme crevice as measured by the accessibility of the alkaline conformer and the strength of the heme-Met80 bond.62 However, introduction of the G41S mutation into mouse Cytc shows that the correlation between a more accessible alkaline state and higher peroxidase activity is not absolute,61 consistent with our results for K72A Hu Cytc. HD exchange and backbone dynamics measured by NMR show that the G41S mutation in Hu Cytc enhances the dynamics of both the 40–57 and 70–85 Ω-loops of Hu Cytc, suggesting that increased dynamics near the heme are primarily responsible for the enhance peroxidase activity.64 As noted in the studies on the peroxidase activity of G41S Cytc, the effects of the intrinsic peroxidase activity of Cytc when it is not bound to cardiolipin remain unclear.61 However, the much lower intrinsic peroxidase activity of Cytc from higher eukaryotes, like horse12, 34 and human, compared to lower eukaryotes like yeast,12 show that Cytc has evolved to limit intrinsic peroxidase activity. Our work shows that Lys72 contributes to limiting the intrinsic peroxidase activity of Cytc.

Relevance to Peroxidase Activity in the Presence of CL

Both compact and extended conformers of Cytc form when it binds to CL, with the latter being more important at higher lipid to protein ratios.7, 65, 66 Both the compact and extended conformers are competent for peroxidase activity.7, 67 However, peroxidase activity is higher for the extended conformer, suggesting that it could be more effective at CL oxidation.7 Which CL-bound conformer functions in vivo remains a matter of debate.7 The peroxidase activity of the position 41 variants, which is higher in aqueous solution, is not enhanced in the presence of CL vesicles, nor is release of Cytc from mitochondria enhanced by position 41 mutations after stimulating apoptosis.61 Mutations that effect intrinsic peroxidase activity in aqueous solution would seem more likely to affect peroxidase activity of compact conformers than extended conformers. Thus, it may be important to study the effect of lipid to protein ratio on the peroxidase activity of Cytc variants permissive for peroxidase activity in aqueous buffer to understand whether these variants also affect peroxidation of CL.

The Many Roles of Lys72

Position 72 of Cytc is absolutely conserved as lysine (or trimethyllysine in fungi).9, 31 Lys72 has been implicated as essential for interaction with redox partners68 for being a component of site A for the interaction with CL,69 and for the interaction of Cytc with Apaf-1 to form the apoptosome.16, 70, 71 Our current work indicates that Lys72 may also be important in limiting the intrinsic peroxidase activity of Cytc, so that this activity is more effectively turned off when Cytc is not bound to CL. The K72A mutation increases basal peroxidase activity, so it should not inhibit release of Cytc from mitochondria. Studies with K72A Cytc knockin mice show that Cytc is still released from the mitochondria after pro-apoptotic stimuli.72 However, as expected, the apoptosome does not form and apoptosis does not proceed. Given the involvement of Lys72 in so many of the functions of Cytc, it is not surprising that it is evolutionally conserved.

CONCLUSIONS

Lys72 is a significant suppressor of peroxidase activity in both yeast and human cytochromes c. The percent effect of Lys72 is somewhat larger in human cytochrome c. The K72A mutation causes a small increase in global stability, thus the intrinsic peroxidase activity of cytochrome c must not be solely controlled by global stability. Structural data for horse and yeast cytochromes c suggested that Lys72 stabilizes Ω-loop D via direct interactions with the far side of Ω-loop D. The X-ray structures of WT Hu Cytc and of the K72A variant indicate that Lys72 may not be the primary mediator of interactions between opposite sides of Ω-loop D. Instead, it appears that steric clashes between the side chains of positions 72 and 81 may be of primary importance in suppressing the Ω-loop D dynamics, which support peroxidase activity. This interpretation is supported by our crystal structure of K72A iso-1-Cytc with Met80-heme ligation replaced by heme-hydroxide ligation which requires the side chain of position 81 to move against that of residue 72.12 Our observation that the percent enhancement of peroxidase activity by the K72A mutation is larger for Hu Cytc, which has isoleucine at position 81, than for yeast iso-1-Cytc, which has alanine at position 81, supports this interpretation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was supported by National Science Foundation grants, CHE-1306903 and CHE-1609720 to B.E.B. The Bruker microflex MALDI-ToF mass spectrometer was purchased with Major Research Instrumentation Grant CHE-1039814 from the National Science Foundation. The Macromolecular X-ray Diffraction Core Facility at the University of Montana was supported by a CoBRE grant from NIGMS, P20GM103546. We thank the staff at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsouce (SSRL) SMB for assistance with data collection. Use of the SSRL, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (including P41GM103393).

ABBREVIATIONS

- Cytc

cytochrome c

- Hu Cytc

human cytochrome c, iso-1-Cytc, yeast iso-1-cytochrome c, WT, wild type

- CD

circular dichroism

- GdnHCl

guanidine hydrochloride

- tmK

trimethyllysine

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Figures S1 and S2 show water-mediated hydrogen bond networks at the surface of WT and K72A Hu Cytc. Figure S3 shows typical pH jump stopped-flow data. Tables S1 to S4 provide rate constants and amplitudes obtained from pH jump stopped-flow data. Table S5 provides KM and kcat for peroxidation of guaiacol from pH 6 to 10.

References

- 1.Dickerson RE, Timkovich R. Cytochromes c. In: Boyer PD, editor. The Enzymes. 3. 3. Academic Press; New York: 1975. pp. 397–547. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hütteman M, Doan JW, Goustin A-S, Sinkler C, Mahapatra G, Shay J, Liu J, Elbaz H, Aras S, Grossman LI, Ding Y, Zielske SP, Malek MH, Sanderson TH, Icksoo L. Regulation of cytochrome c in respiration, apoptosis, neurodegeneration and cancer: the good, the bad and the ugly. In: Thom R, editor. Cytochromes b and c: biochemical properties, biological functions and electrochemical analysis. Nova Science Publishers; New York, NY: 2014. pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu X, Kim CN, Yang J, Jemmerson R, Wang X. Induction of apoptotic program in cell-free extracts: requirement for dATP and cytochrome c. Cell. 1996;86:147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ow YP, Green DR, Hao Z, Mak TW. Cytochrome c: functions beyond respiration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:532–542. doi: 10.1038/nrm2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kagan VE, Tyurin VA, Jiang J, Tyurina YY, Ritov VB, Amoscato AA, Osipov AN, Belikova NA, Kapralov AA, Kini V, Vlasova II, Zhao Q, Zou M, Di P, Svistunenko DA, Kurnikov IV, Borisenko GG. Cytochrome c acts as a cardiolipin oxygenase required for release of proapoptotic factors. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:223–232. doi: 10.1038/nchembio727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jemmerson R, Liu J, Hausauer D, Lam KP, Mondino A, Nelson RD. A conformational change in cytochrome c of apoptotic and necrotic cells is detected by monoclonal antibody binding and mimicked by association of the native antigen with synthetic phospholipid vesicles. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3599–3609. doi: 10.1021/bi9809268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanske J, Toffey JR, Morenz AM, Bonilla AJ, Schiavoni KH, Pletneva EV. Conformational properties of cardiolipin-bound cytochrome c. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:125–130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112312108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickerson RE, Takano T, Eisenberg D, Kallai OB, Samson L, Cooper A, Margoliash E. Ferricytochrome c: I. General features of the horse and bonito proteins at 2.8 Å resolution. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:1511–1535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banci L, Bertini I, Rosato A, Varani G. Mitochondrial cytochromes c: a comparative analysis. J Biol Inorg Chem. 1999;4:824–837. doi: 10.1007/s007750050356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berghuis AM, Brayer GD. Oxidation state-dependent conformational changes in cytochrome c. J Mol Biol. 1992;223:959–976. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90255-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bushnell GW, Louie GV, Brayer GD. High-resolution three-dimensional structure of horse heart cytochrome c. J Mol Biol. 1990;214:585–595. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90200-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McClelland LJ, Mou TC, Jeakins-Cooley ME, Sprang SR, Bowler BE. Structure of a mitochondrial cytochrome c conformer competent for peroxidase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:6648–6653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323828111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cherney MM, Junior CC, Bergquist BB, Bowler BE. Dynamics of the His79-heme alkaline transition of yeast iso-1-cytochrome c probed by conformationally gated electron transfer with Co(II)bis(terpyridine) J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:12772–12782. doi: 10.1021/ja405725f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cherney MM, Junior C, Bowler BE. Mutation of trimethyllysine-72 to alanine enhances His79-heme mediated dynamics of iso-1-cytochrome c. Biochemistry. 2013;52:837–846. doi: 10.1021/bi301599g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maity H, Rumbley JN, Englander SW. Functional role of a protein foldon - an Omega-loop foldon controls the alkaline transition in ferricytochrome c. Proteins. 2006;63:349–355. doi: 10.1002/prot.20757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olteanu A, Patel CN, Dedmon MM, Kennedy S, Linhoff MW, Minder CM, Potts PR, Deshmukh M, Pielak GJ. Stability and apoptotic activity of recombinant human cytochrome c. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;312:733–740. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.10.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosell FI, Mauk AG. Spectroscopic properties of a mitochondrial cytochrome c with a single thioether bond to the heme prosthetic group. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7811–7818. doi: 10.1021/bi016060e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pollock WB, Rosell FI, Twitchett MB, Dumont ME, Mauk AG. Bacterial expression of a mitochondrial cytochrome c. Trimethylation of Lys72 in yeast iso-1-cytochrome c and the alkaline conformational transition. Biochemistry. 1998;37:6124–6131. doi: 10.1021/bi972188d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel CN, Lind MC, Pielak GJ. Characterization of horse cytochrome c expressed in Escherichia coli. Protein Expression Purif. 2001;22:220–224. doi: 10.1006/prep.2001.1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldes ME, Jeakins-Cooley ME, McClelland LJ, Mou TC, Bowler BE. Disruption of a hydrogen bond network in human versus spider monkey cytochrome c affects heme crevice stability. J Inorg Biochem. 2016;158:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2015.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Redzic JS, Bowler BE. Role of hydrogen bond networks and dynamics in positive and negative cooperative stabilization of a protein. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2900–2908. doi: 10.1021/bi048218b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wandschneider E, Hammack BN, Bowler BE. Evaluation of cooperative interactions between substructures of iso-1-cytochrome c using double mutant cycles. Biochemistry. 2003;42:10659–10666. doi: 10.1021/bi034958t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276A:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkóczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rajagopal BS, Edzuma AN, Hough MA, Blundell KLIM, Kagan VE, Kapralov AA, Fraser LA, Butt JN, Silkstone GG, Wilson MT, Svistunenko DA, Worrall JAR. The hydrogen-peroxide-induced radical behaviour in human cytochrome c–phospholipid complexes: implications for the enhanced pro-apoptotic activity of the G41S mutant. Biochem J. 2013;456:441–452. doi: 10.1042/BJ20130758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nozaki Y. The preparation of guanidine hydrochloride. Methods Enzymol. 1972;26:43–50. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(72)26005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen VB, Bryan Arendall WI, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pace CN, Shirley BA, Thomson JA. Measuring the conformational stability of a protein. In: Creighton TE, editor. Protein structure: a practical approach. IRL Press at Oxford University Press; New York: 1989. pp. 311–330. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schellman JA. Solvent denaturation. Biopolymers. 1978;17:1305–1322. doi: 10.1002/bip.360260408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore GR, Pettigrew GW. Cytochromes c: Evolutionary, Structural and Physicochemical Aspects. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kristinsson R, Bowler BE. Communication of stabilizing energy between substructures of a protein. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2349–2359. doi: 10.1021/bi048141r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson CJ, Bowler BE. pH dependence of formation of a partially unfolded state of a Lys 73 -> His variant of iso-1-cytochrome c: implications for the alkaline conformational transition of cytochrome c. Biochemistry. 2000;39:13584–13594. doi: 10.1021/bi0017778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Z, Matsuo T, Nagao S, Hirota S. Peroxidase activity enhancement of horse cytochrome c by dimerization. Org Biomol Chem. 2011;9:4766–4769. doi: 10.1039/c1ob05552f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson DP, Kiesow LA. Enthalpy of decomposition of hydrogen peroxide by catalase at 25 °C (with molar extinction coefficients of H2O2 solutions in the UV) Anal Biochem. 1972;49:474–478. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(72)90451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noble RW, Gibson QH. The reaction of ferrous horseradish peroxidase with hydrogen peroxide. J Biol Chem. 1970;245:2409–2413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldschmid O. The effect of alkali and strong acid on the ultraviolet absorption spectrum of lignin and related compounds. J Am Chem Soc. 1953;75:3780–3783. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diederix REM, Ubbink M, Canters GW. The peroxidase activity of cytochrome c-550 from Paracoccus versutus. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:4207–4216. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hong X, Dixon DW. NMR study of the alkaline isomerization of ferricytochrome c. FEBS Lett. 1989;246:105–108. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)80262-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shah R, Schweitzer-Stenner R. Structural changes of horse heart ferricytochrome c induced by changes of ionic strength and anion binding. Biochemistry. 2008;47:5250–5257. doi: 10.1021/bi702492n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hagarman A, Duitch L, Schweitzer-Stenner R. The conformational manifold of ferricytochrome c explored by visible and far-UV electronic circular dichroism spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2008;47:9667–9677. doi: 10.1021/bi800729w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fersht A. Structure and Mechanism in Protein Science. W. H. Freeman and Company; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bandi S, Bowler BE. Effect of an Ala81His mutation on the Met80 loop dynamics of iso-1-cytochrome c. Biochemistry. 2015;54:1729–1742. doi: 10.1021/bi501252z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoang L, Maity H, Krishna MM, Lin Y, Englander SW. Folding units govern the cytochrome c alkaline transition. J Mol Biol. 2003;331:37–43. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00698-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saigo S. A transient spin-state change during alkaline isomerization of ferricytochrome c. J Biochem. 1981;89:1977–1980. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a133400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saigo S. Kinetic and equilibrium studies of alkaline isomerization of vertebrate cytochromes c. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;669:13–20. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(81)90217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kihara H, Saigo S, Nakatani H, Hiromi K, Ikeda-Saito M, Iizuka T. Kinetic study of isomerization of ferricytochrome c at alkaline pH. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976;430:225–243. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(76)90081-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hasumi H. Kinetic studies on isomerization of ferricytochrome c in alkaline and acid pH ranges by the circular dichroism stopped-flow method. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1980;626:265–276. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(80)90120-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davis LA, Schejter A, Hess GP. Alkaline isomerization of oxidized cytochrome c. Equilibrium and kinetic measurements. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:2624–2632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosell FI, Ferrer JC, Mauk AG. Proton-linked protein conformational switching: definition of the alkaline conformational transition of yeast iso-1-ferricytochrome c. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:11234–11245. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alber T, Sun DP, Nye JA, Muchmore DC, Matthews BW. Temperature-sensitive mutations of bacteriophage T4 lysozyme occur at sites with low mobility and low solvent accessibility in the folded protein. Biochemistry. 1987;26:3754–3758. doi: 10.1021/bi00387a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ying T, Zhong F, Xie J, Feng Y, Wang ZH, Huang ZX, Tan X. Evolutionary alkaline transition in human cytochrome c. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2009;41:251–257. doi: 10.1007/s10863-009-9223-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martinez RE, Bowler BE. Proton-mediated dynamics of the alkaline conformational transition of yeast iso-1-cytochrome c. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:6751–6758. doi: 10.1021/ja0494454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Radi R, Thomson L, Rubbo H, Prodanov E. Cytochrome c-catalyzed oxidation of organic molecules by hydrogen peroxide. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1991;288:112–117. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90171-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krishna MM, Maity H, Rumbley JN, Lin Y, Englander SW. Order of steps in the cytochrome c folding pathway: evidence for a sequential stabilization mechanism. J Mol Biol. 2006;359:1410–1419. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krishna MM, Lin Y, Rumbley JN, Englander SW. Cooperative omega loops in cytochrome c: role in folding and function. J Mol Biol. 2003;331:29–36. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00697-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morison IM, Cramer Bordé EM, Cheesman EJ, Cheong PL, Holyoake AJ, Fichelson S, Weeks RJ, Lo A, Davies SMK, Wilbanks SM, Fagerlund RD, Ludgate MW, da Silva Tatley FM, Coker MSA, Bockett NA, Hughes G, Pippig DA, Smith MP, Capron C, Ledgerwood EC. A mutation of human cytochrome c enhances the intrinsic apoptotic pathway but causes only thrombocytopenia. Nat Genet. 2008;40:387–389. doi: 10.1038/ng.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.De Rocco D, Cerqua C, Goffrini P, Russo G, Pastore A, Meloni F, Nicchia E, Moraes CT, Pecci A, Salviati L, Savoia A. Mutations of cytochrome c identified in patients with thrombocytopenia THC4 affect both apoptosis and cellular bioenergetics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842:269–274. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Johnson B, Lowe GC, Futterer J, Lordkipanidzé M, MacDonald D, Simpson MA, Sanchez-Guiú I, Drake S, Bem D, Leo V, Fletcher SJ, Dawood B, Rivera J, Allsup D, Biss T, Bolton-Maggs PHB, Collins P, Curry N, Grimley C, James B, Makris M, Motwani J, Pavord S, Talks K, Thachil J, Wilde J, Williams M, Harrison P, Gissen P, Mundell S, Mumford A, Daly ME, Watson SP, Morgan NV. Whole exome sequencing identifies genetic variants in inherited thrombocytopenia with secondary qualitative function defects. Haematologica. 2016;101:1170–1179. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.146316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ong L, Morison IM, Ledgerwood EC. Megakaryocytes from CYCS mutation-associated thrombocytopenia release platelets by both proplatelet-dependent and -independent processes. Br J Haematol. 2017;176:268–279. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Josephs TM, Morison IM, Day CL, Wilbanks SM, Ledgerwood EC. Enhancing the peroxidase activity of cytochrome c by mutation of residue 41: implications for the peroxidase mechanism and cytochrome c release. Biochem J. 2014;458:259–265. doi: 10.1042/BJ20131386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Josephs TM, Liptak MD, Hughes G, Lo A, Smith RM, Wilbanks SM, Bren KL, Ledgerwood EC. Conformational change and human cytochrome c function: mutation of residue 41 modulates caspase activation and destabilizes Met-80 coordination. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2013;18:289–297. doi: 10.1007/s00775-012-0973-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liptak MD, Fagerlund RD, Ledgerwood EC, Wilbanks SM, Bren KL. The proapoptotic G41S mutation to human cytochrome c alters the heme electronic structure and increases the electron self-exchange rate. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:1153–1155. doi: 10.1021/ja106328k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Karsisiotis AI, Deacon OM, Wilson MT, Macdonald C, Blumenschein TMA, Moore GR, Worrall JAR. Increased dynamics in the 40–57 Ω-loop of the G41S variant of human cytochrome c promote its pro-apoptotic conformation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30447. doi: 10.1038/srep30447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pandiscia LA, Schweitzer-Stenner R. Coexistence of native-like and non-native cytochrome c on anionic liposomes with different cardiolipin content. J Phys Chem B. 2015;119:12846–12859. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b07328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pandiscia LA, Schweitzer-Stenner R. Coexistence of native-like and non-native partially unfolded ferricytochrome c on the surface of cardiolipin-containing liposomes. J Phys Chem B. 2015;119:1334–1349. doi: 10.1021/jp5104752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mandal A, Hoop CL, DeLucia M, Kodali R, Kagan VE, Ahn J, van der Wel PCA. Structural changes and proapoptotic peroxidase activity of cardiolipin-bound mitochondrial cytochrome c. Biophys J. 2015;109:1873–1884. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Margoliash E, Schejter A. How does a small protein become so popular?: A succinct account of the developement of our understanding of cytochrome c. In: Scott RA, Mauk AG, editors. Cytochrome c: A Multidisciplinary Approach. University Science Books; Sausalito, CA: 1996. pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rytömaa M, Kinnunen PKJ. Reversibility of the binding of cytochrome c to liposomes. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:3197–3202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.7.3197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yu T, Wang X, Purring-Koch C, Wei Y, McLendon GL. A mutational epitope for cytochrome c binding to the apoptosis protease activation factor-1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13034–13038. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009773200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kluck RM, Ellerby LM, Ellerby HM, Naiem S, Yaffe MP, Margoliash E, Bredesen D, Mauk AG, Sherman F, Newmeyer DD. Determinants of cytochrome c pro-apoptotic activity. The role of lysine 72 trimethylation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:16127–16133. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.21.16127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hao Z, Duncan GS, Chang C-C, Elia A, Fang M, Wakeham A, Okada H, Calzascia T, Jang Y, You-Ten A, Yeh W-C, Ohashi P, Wang X, Mak TW. Specific ablation of the apoptotic functions of cytochrome c reveals a differential requirement for cytochrome c and Apaf-1 in apoptosis. Cell. 121:579–591. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.