Abstract

Purpose

There is little information about healthcare utilization for sarcoidosis. This study examined need for hospitalization as a measure of healthcare burden in this disease.

Methods

A cohort of Olmsted County, Minnesota residents diagnosed with sarcoidosis between January 1, 1976 and December 31, 2013 was identified using the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Diagnosis was made based on individual medical record review. For each sarcoidosis subject, one sex and age-matched comparator without sarcoidosis was randomly selected from the same population. Data on hospitalizations were retrieved electronically from billing data of the Mayo Clinic, the Olmsted Medical Center and their affiliated hospitals. These data were available from 1987 through 2015. Subjects who died or emigrated from Olmsted County prior to 1987 were excluded.

Results

332 incident cases of sarcoidosis and 342 comparators were included. Hospitalization rates were significantly higher among patients with sarcoidosis than comparators (rate ratio [RR]:1.37; 95% confidence interval [CI]:1.24–1.52). Analysis based on sex revealed a significantly increased rate among females (RR: 1.60; 95% CI: 1.40–1.82) but not among males (RR 1.06; 95% CI 0.91–1.25). The overall age and sex-adjusted rates of hospitalization were stable from 1987 to 2015 for both cases and comparators. The average length of stay was similar (4.6 and 4.4 days for sarcoidosis and non-sarcoidosis hospitalizations, respectively, p=0.87).

Conclusion

In this population, patients with sarcoidosis had a significantly higher rate of hospitalization than patients without sarcoidosis, driven by higher rates in females.

Keywords: Sarcoidosis, Clinical epidemiology, Hospitalization

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a chronic granulomatous disease that commonly affects the lungs and intra-thoracic lymph nodes although any organ can be involved. The clinical manifestations of sarcoidosis are variable, ranging from asymptomatic incidental radiographic findings to chronic progressive disease with organ failure [1, 2]. Sarcoidosis is a fairly common disease in United States (U.S.). A recent study utilizing a health insurance database has estimated a prevalence of sarcoidosis of 141 cases per 100,000 African-Americans and 50 cases per 100,000 Caucasian-Americans [3]. The etiology of sarcoidosis is not known but is believed to be an interaction between genetic predisposition and environmental factors [4].

Little is known about the disease burden and healthcare utilization among patients with sarcoidosis, especially hospitalization. Previous epidemiologic studies on trends of hospitalization among these patients have yielded conflicting results. Two coding-based studies using nationwide hospitalization samples from the U.S. found an increased rate of hospitalization among patients with sarcoidosis from 1980 to mid-2000 [5, 6] while a coding-based study from Switzerland using a national hospitalization registry reported a stable rate of hospitalization from 2002 to 2012 [7]. On the other hand, a prospective cohort study of U.S. Navy personnel demonstrated a marked decline of hospitalization for sarcoidosis from 1975 to 2001 [8]. There is no study that directly compares the rate of hospitalization among patients with sarcoidosis with comparators without sarcoidosis.

This study used a previously identified population-based cohort of patients with sarcoidosis [9] to investigate the rate and characteristics of their hospitalization in comparison with a cohort of comparators without sarcoidosis drawn from the same underlying population.

Methods

Approval for this study was obtained from the Mayo Clinic and the Olmsted Medical Center institutional review boards (Mayo Clinic IRB 14-008651, Olmsted Medical Center IRB 012-OMC-15). The need for informed consent was waived. This study used a previously identified cohort of 345 residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota with diagnosis of sarcoidosis between January 1, 1976 and December 31, 2013, which was identified through the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) 9. The REP allows a virtually complete identification of all clinically recognized cases of sarcoidosis because of the complete access to inpatient and outpatient medical records, pathologies and laboratory investigations of all residents for over six decades from all local healthcare providers, which include the Mayo Clinic, the Olmsted Medical Center, local nursing homes and the few private practitioners. The utility of the REP for epidemiologic investigations has been previously discussed [10].

The identification process and clinical characteristics of this cohort have been previously described 9. In brief, potential cases of sarcoidosis were identified from diagnostic codes related to sarcoidosis and non-caseating granuloma. Diagnosis of sarcoidosis was then confirmed by individual medical record review which required physician diagnosis of sarcoidosis supported by histological evidence of non-caseating granuloma, radiographic evidence of intrathoracic sarcoidosis and compatible clinical manifestations with exclusion of other granulomatous diseases such as tuberculosis and histoplasmosis. The only exception for these requirements was stage I pulmonary sarcoidosis that required only the presence of symmetric bilateral hilar adenopathy on thoracic imaging. Histopathologic confirmation was not required for stage I disease. Cases with a diagnosis of sarcoidosis prior to residency in Olmsted County (i.e., prevalent cases) were excluded.

A cohort of comparators without sarcoidosis at the time of the patient’s sarcoidosis diagnosis was assembled. One comparator was randomly selected from the same underlying population for each patient with sarcoidosis. Matching criteria were similar age (±3 years) and same sex. The index date of the comparator was the sarcoidosis diagnosis date of the corresponding case. Data on demographics of cases and comparators were collected. Data on hospitalizations (admission/discharge dates and admission/discharge diagnoses) for cases and comparators were retrieved electronically from billing data of the Mayo Clinic as well as the Olmsted Medical Center and its affiliated hospitals. These data are available from 1987 and continuing through 2015. Thus, cases and comparators who died or emigrated from Olmsted County prior to 1987 were excluded (11 sarcoidosis cases + 3 comparators) as were those who declined to authorize the use of their medical records for research purposes per Minnesota statute sometime following their initial inclusion in the cohorts (2 sarcoidosis cases). For this analysis, follow-up began with the latter of index date or January 1, 1987 (defined as baseline) and ended at the earlier of death, migration from Olmsted County, or December 31, 2015. Readmissions were defined as admissions that occur within 30 days of a previous hospital discharge. Primary discharge diagnosis for each hospitalization was made by healthcare providers caring for the patient during the hospital stay and these diagnoses were coded using ICD-9-CM during the billing process. Primary discharge diagnoses were grouped together using the Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project [11]. According to the CSS, diagnoses are classified into 18 chapters including infections (which include systemic infection and parasitic diseases but do not include specific organ infection); neoplasms; endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases and immunity disorders; diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs; mental illness; diseases of the nervous system and sense organs; diseases of the circulatory system; diseases of respiratory system; diseases of the digestive system; diseases of the genitourinary system; complications of pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium; diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue; diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue; congenital anomalies; certain conditions originating in the perinatal period; injury and poisonings (including fractures); symptoms, signs and ill-defined conditions; and residual codes (unclassified). Congenital anomalies, certain conditions originating in the perinatal period, and unclassified categories were excluded from the summarized results due to the paucity of hospitalizations for these diagnoses. For this study, sarcoidosis was analyzed as a separate category rather than within the systemic infection and parasitic diseases chapter. Data on primary discharge diagnosis were available since 1995. For analyses using discharge diagnosis, additional cases and comparators who died or emigrated from Olmsted County prior to 1995 were excluded (15 sarcoidosis cases + 10 comparators), and follow-up began with the latter of index date or January 1, 1995 and ended at the earlier of death, migration from Olmsted County, or December 31, 2015.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics (means, proportions etc.) were used to summarize the baseline characteristics of cases and comparators. Comparisons of characteristics between cases and controls and between sexes were performed using chi-square, Fisher’s exact and rank sum tests. Data were analyzed using person-year methods and rate ratios comparing sarcoidosis to non-sarcoidosis. Comparisons of person-year rates were performed using Poisson methods. Poisson regression models with smoothing splines were used to examine trends over time to allow for non-linear effects. Poisson regression models were also used to examine risk factors for hospitalizations. Medication use was modeled using time-dependent covariates whereby patients were considered to be non-users during the person-years of follow-up prior to initiation of medication were considered as medication users during the person-years of follow-up after initiation of medication. Direct adjustment methods were used to obtain age and sex adjusted estimates of hospitalization rates over time. Comparisons of length of stay for sarcoidosis vs. non-sarcoidosis were performed using generalized linear models adjusted for age, sex and calendar year with random intercepts to account for multiple hospitalizations in the same patient. Readmission rates were calculated as the number of readmissions divided by the number of subsequent hospitalizations (not counting the first hospitalization for each patient, as it could not be a readmission by definition). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, U.S.) and R 3.2.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

The analysis included 332 cases of sarcoidosis (50.3% female, 90.2% Caucasian, mean age at diagnosis 45.7 years [standard deviation [SD] 13.4] and mean follow-up from baseline 14.8 years [SD 9.2]) and 342 comparators without sarcoidosis (50.0% female, 95.0% Caucasian, mean age 45.2 years [SD 13.5] and mean follow-up 16.1 years [SD 9.3]). Age at diagnosis of sarcoidosis was higher among females (mean: 48.4, SD: 13.6 years) than males (mean: 43.0, SD: 12.7 years; p<0.001). Females with sarcoidosis had a higher prevalence of extra-thoracic disease, use of immunosuppressive agents and obesity compared to males with sarcoidosis. Demographics and characteristics of males and females with sarcoidosis at the time of sarcoidosis diagnosis are described in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of 332 patients with sarcoidosis at the time of sarcoidosis diagnosis

| Females (N=167) | Males (N=165) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Demographics | |||

|

| |||

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 48.4 (13.6) | 43.0 (12.7) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Ethnicity (%) | 0.20 | ||

| Caucasian | 149 (89.8) | 144 (90.6) | |

| African-American | 7 (4.2) | 11 (6.9) | |

| Asian | 5 (3.0) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Native American | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Other | 5 (3.0) | 2 (1.3) | |

| Missing | 1 | 6 | |

|

| |||

| Sarcoidosis characteristics | |||

|

|

|||

| Stage (%) | 0.44 | ||

| 1 | 89 (58.6) | 79 (52.7) | |

| 2 | 43 (28.3) | 44 (29.3) | |

| 3–4 | 20 (13.2) | 27 (18.0) | |

| Missing* | 15 | 15 | |

|

| |||

| Presence of extra-thoracic involvement (%) | 78 (46.7) | 58 (35.2) | 0.032 |

|

| |||

| Use of glucocorticoids within 12 months after diagnosis (%) | 46 (30.3) | 38 (25.3) | 0.34 |

|

| |||

| Use of DMARDs within 12 months after diagnosis (%) | 9 (5.9) | 1 (0.7) | 0.020 |

|

| |||

| Comorbidities | |||

|

| |||

| Obesity (%) | 81 (48.5) | 61 (37.0) | 0.034 |

|

| |||

| Hypertension (%) | 43 (25.7) | 28 (17.0) | 0.051 |

|

| |||

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 25 (15.0) | 23 (13.9) | 0.79 |

|

| |||

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 19 (11.4) | 10 (6.1) | 0.09 |

not available for patients without pulmonary involvement

DMARDs, disease-modifying ant-rheumatic drugs; SD, standard deviation

Hospitalization rates

The patients with sarcoidosis had 852 hospitalizations during 4,913 person-year (py) of follow-up, corresponding to a hospitalization rate of 17.3 per 100 py. Comparators without sarcoidosis had 694 hospitalizations during 5,496 py, corresponding to a hospitalization rate of 12.6 per 100 py. Hospitalization rates were significantly higher among patients with sarcoidosis than comparators without sarcoidosis with the rate ratio (RR) of 1.37 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.24 – 1.52).

Analysis by sex revealed 567 hospitalizations during 2,577 py of follow-up among females with sarcoidosis, corresponding to a hospitalization rate of 22.0 per 100 py. There were 378 hospitalizations during 2,741 py among females without sarcoidosis, corresponding to a hospitalization rate of 13.8 per 100 py. Hospitalization rates were significantly higher among females with sarcoidosis than comparators without sarcoidosis (RR 1.60; 95% CI 1.40 – 1.82).

Among males with sarcoidosis, there were 285 hospitalizations during 2,336 py of follow-up, corresponding to a hospitalization rate of 12.2 per 100 py. Among males without sarcoidosis, there were 316 hospitalizations during 2,755 py of follow up, corresponding to a hospitalization rate of 11.5 per 100 py. Hospitalization rates were not significantly different between males with and without sarcoidosis (RR 1.06; 95% CI 0.91 – 1.25).

Unadjusted rates of hospitalization and rate ratios between cases and comparators by sex, age group, calendar year as well as number of years after diagnosis/index date are described in table 2. As expected, the rates of hospitalization increased with age in both cohorts but the rate ratios comparing the 2 cohorts were relatively stable across age groups except for a higher rate ratio in the age group 35–39 years (RR 1.94; 95% CI 1.50 – 2.54).

Table 2.

Rate of hospitalization per 100 person-years for patients with sarcoidosis and comparators without sarcoidosis

| Sarcoidosis rate | Non-sarcoidosis rate | Rate ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Overall | 17.3 | 12.6 | 1.37 (1.24 – 1.52) |

|

| |||

| Sex | |||

| Females | 22.0 | 13.8 | 1.60 (1.40 – 1.82) |

| Males | 12.2 | 11.5 | 1.06 (0.91 – 1.25) |

|

| |||

| Ages | |||

| 20–34 | 11.5 | 9.8 | 1.18 (0.74 – 1.88) |

| 35–49 | 9.7 | 5.0 | 1.94 (1.50 – 2.54) |

| 50–64 | 16.2 | 11.8 | 1.38 (1.17 – 1.64) |

| 65–79 | 25.7 | 21.1 | 1.22 ( 1.01 – 1.46) |

| 80+ | 48.8 | 42.9 | 1.14 (0.88 – 1.48) |

|

| |||

| Calendar year | |||

| 1987–1991 | 15.5 | 9.8 | 1.57 (1.10 – 2.28) |

| 1992–1996 | 13.4 | 11.5 | 1.16 (0.86 – 1.57) |

| 1997–2001 | 14.3 | 11.8 | 1.22 (0.93 – 1.59) |

| 2002–2006 | 23.0 | 14.0 | 1.64 (1.34 – 2.03) |

| 2007–2011 | 16.8 | 13.1 | 1.28 (1.04 – 1.58) |

| 2012–2015 | 18.3 | 13.5 | 1.36 (1.09 – 1.69) |

|

| |||

| Years after sarcoidosis diagnosis | |||

| 0–4 | 15.9 | 10.2 | 1.56 (1.26 – 1.94) |

| 5–9 | 15.1 | 11.0 | 1.37 (1.09 – 1.73) |

| 10–14 | 18.6 | 14.2 | 1.31 (1.05 – 1.64) |

| 15–19 | 21.8 | 12.7 | 1.71 (1.33 – 2.21) |

| 20–24 | 17.2 | 14.4 | 1.19 (0.88 – 1.61) |

| 25–29 | 18.5 | 15.8 | 1.17 (0.80 – 1.71) |

CI, confidence interval

A sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate hospitalization risk after excluding non-Caucasian patients (39 cases and 18 comparators). There were 293 Caucasian patients with sarcoidosis who had 785 hospitalizations over 4,515 py of follow-up, corresponding to a hospitalization rate of 17.4 per 100 py. The RR of hospitalization compared with comparators was 1.36 (95% CI 1.22 – 1.50). The RR for hospitalization by sex was 1.57 (95% CI 1.37 – 1.79) among females and 1.05 (95% CI 0.89 – 1.24) among males.

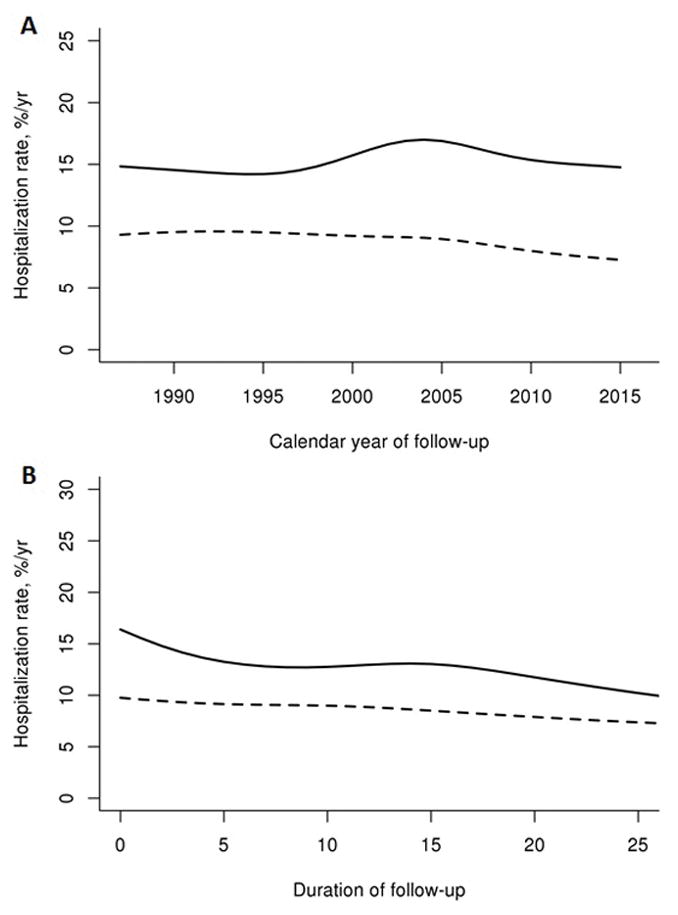

While the unadjusted rates appear to increase over calendar time in both cohorts (table 2), the overall age and sex-adjusted rates of hospitalization were stable from 1987 to 2015 for both cases and comparators (p = 0.15 for cases and p = 0.73 for comparators, figure 1a). Likewise, while the unadjusted hospitalization rates appeared to increase with disease duration in both cohorts (table 2), the age and sex adjusted rates did not. In fact, there was a significant decline in age and sex-adjusted rates of hospitalization among patients with sarcoidosis over the disease duration (p=0.001). This decline persisted after removal of 19 hospitalizations that occurred at the time of sarcoidosis diagnosis (p=0.008). Age and sex adjusted hospitalization rates were stable among comparators (p=0.19) (figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Figure 1a. Age and sex-adjusted rates across calendar year among patients with sarcoidosis (solid line) and comparators without sarcoidosis (dashed line)

Figure 1b. Age and sex-adjusted rates across duration among patients with sarcoidosis (solid line) and comparators without sarcoidosis (dashed line)

Patients with sarcoidosis were hospitalized at a significantly higher rate than subjects without sarcoidosis in 7 of 15 CCS chapters. Excluding 20 hospitalizations for sarcoidosis itself (primarily occurring at the time of sarcoidosis diagnosis), the highest RR was observed for the skin / soft tissue disease chapter (RR 3.23, 95% CI 1.63 – 7.38), followed by the endocrine / metabolic disease chapter (RR 2.73, 95% CI 1.46–5.59). Interestingly, the rate and RR of hospitalization among females were higher than males in almost every disease chapter except for the respiratory chapter (table 3). The difference was most pronounced in the skin / soft tissue disease chapter as the RR of this chapter was the highest among female (RR 4.33) but was less than 1.0 among males (RR 0.51). The increased hospitalization rates among females compared to males with sarcoidosis were partially due to the older age at diagnosis of sarcoidosis among females. Adjusting for age, significant increases in hospitalizations rates among patients with sarcoidosis for females compared to males were limited to hospitalizations for diagnoses in the nervous system, digestive system, genitourinary system, skin/subcutaneous tissue and symptoms/signs/ill-defined conditions. The only chapter with higher hospitalization rates among males with sarcoidosis compared to females was the respiratory system.

Table 3.

Rate of hospitalization per 100 person-years for specific Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) chapters of patients with sarcoidosis and comparators without sarcoidosis

| CCS chapters | Overall hospitalization rate (sarcoidosis / non-sarcoidosis) | Overall rateratio (95% CI) | Female hospitalization rate (sarcoidosis / non-sarcoidosis) | Female rateratio (95% CI) | Male hospitalization rate (sarcoidosis /non-sarcoidosis) | Male rateratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infections, parasitics* | 0.6 / 0.2 | 2.28 (1.16–4.90) | 0.8 / 0.3 | 2.86 (1.24–8.01) | 0.3 / 0.2 | 1.39 (0.44–4.73) |

| Neoplasms | 1.0 / 1.1 | 0.93 (0.62–1.38) | 1.1 / 1.0 | 1.11 (0.62–1.99) | 1.0 / 1.3 | 0.79 (0.44–1.37) |

| Endocrine, metabolic | 0.7 / 0.3 | 2.73 (1.46–5.59) | 1.0 / 0.3 | 3.04 (1.41–7.83) | 0.5 / 0.2 | 2.04 (0.74–6.60) |

| Blood | 0.2 / 0.1 | 2.39 (0.73–10.93) | 0.3 / 0.1 | 2.76 (0.73–17.90) | 0.1 / 0.0 | 1.18 (0.08–18.20) |

| Mental | 0.8 / 0.5 | 1.59 (0.95–2.75) | 1.1 / 0.7 | 1.61 (0.86–3.16) | 0.5 / 0.3 | 1.46 (0.59–3.79) |

| Nervous system | 0.6 / 0.6 | 1.00 (0.57–1.72) | 0.9 / 0.5 | 1.74 (0.88–3.68) | 0.2 / 0.7 | 0.34 (0.10–0.88) |

| Circulatory | 3.3 / 2.9 | 1.11 (0.87–1.41) | 3.9 / 2.8 | 1.37 (1.00–1.91) | 2.6 / 3.1 | 0.85 (0.59–1.21) |

| Respiratory | 1.6 / 1.1 | 1.45 (1.01–2.10) | 1.2 / 1.0 | 1.25 (0.71–2.22) | 2.0 / 1.2 | 1.63 (1.01–2.68) |

| Digestive | 2.0 / 1.4 | 1.43 (1.03–1.99) | 2.6 / 1.6 | 1.60 (1.06–2.44) | 1.3 / 1.2 | 1.14 (0.66–1.95) |

| Genitourinary | 1.0 / 0.6 | 1.65 (1.02–2.71) | 1.6 / 0.9 | 1.79 (1.05–3.17) | 0.3 / 0.3 | 1.02 (0.33–2.99) |

| Pregnancy and childbirth | -- | -- | 0.5 / 0.6 | 0.77 (0.33–1.69) | 0.0 / 0.0 | -- |

| Skin and subcutaneous | 0.7 / 0.2 | 3.23 (1.63–7.38) | 1.2 / 0.3 | 4.33 (2.00–11.84) | 0.1 / 0.1 | 0.51 (0.03–2.98) |

| Musculoskeletal | 1.8 / 1.1 | 1.61 (1.13–2.30) | 2.3 / 1.1 | 2.02 (1.28–3.31) | 1.3 / 1.1 | 1.13 (0.65–1.96) |

| Injury, poisoning | 1.5 / 1.4 | 1.08 (0.76–1.54) | 1.7 / 1.0 | 1.69 (1.02–2.90) | 1.2 / 1.7 | 0.71 (0.42–1.16) |

| Ill-defined conditions | 1.3 / 1.1 | 1.18 (0.80–1.75) | 1.9 / 1.3 | 1.46 (0.91–2.37) | 0.6 / 0.9 | 0.72 (0.34–1.43) |

Excluding 20 hospitalizations for sarcoidosis

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval

Length of stay and readmission

The average length of stay was 4.6 and 4.4 days respectively among the sarcoidosis and non-sarcoidosis hospitalizations (median 3 days, 25th percentile 1 day, 75th percentile 5 days in both cohorts; p=0.87). Readmission rates were similar among the sarcoidosis subjects with 136 readmissions (21% of 653 subsequent hospitalizations) compared to the non-sarcoidosis subjects with 103 readmissions (20% of 503 subsequent hospitalizations; p=0.88).

Predictors of hospitalization among patients with sarcoidosis

Several variables, including age per 10 year increase, female sex, presence of extra-thoracic involvement, stage of pulmonary sarcoidosis higher than 1, use of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs and use of glucocorticoids were predictive for hospitalization among patients with sarcoidosis. Relative risks and 95% confidence intervals of these variables are described in table 4.

Table 4.

Predictors of hospitalization among 332 patients with sarcoidosis

| Characteristic | Age and sex adjusted relative risk (95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|

| Age per 10 year increase | 1.33 (1.24–1.42) |

| Female sex | 1.55 (1.26–1.91) |

| Extrathoracic Involvement | 1.23 (1.01–1.49) |

| Stage | |

| Stage 2 (vs 1) | 1.52 (1.22–1.89) |

| Stage 3–4 (vs 1) | 1.47 (1.14–1.88) |

| DMARD Use (time dependent) | 2.59 (1.91–3.53) |

| Steroid Use (time dependent) | 1.60 (1.32–1.95) |

Discussion

The disease burden and healthcare utilization of sarcoidosis are not well-studied. Previous investigations of hospitalization trends among these patients have yielded conflicting results. The current study is the first to utilize a population-based cohort to investigate the rate of hospitalization among patients with sarcoidosis compared to sex and age-matched subjects without sarcoidosis.

Overall, the rate of hospitalization was significantly higher among patients with sarcoidosis than those without. However, the increased overall hospitalization rate was primarily driven by the increased hospitalization rate among females with sarcoidosis. The hospitalization rate was not significantly increased among males. Sensitivity analysis including only Caucasian patients (which were the majority of patients in this cohort) revealed similar results. Significantly increased hospitalization rates were observed in about half of the chapters of diseases categorized by CCS.

The higher rate and rate ratio of hospitalization among females compared to males were seen in almost every disease chapter and were most prominent in the skin/subcutaneous tissue disease chapter. The higher rate of hospitalization among females with sarcoidosis compared with males with sarcoidosis has also been previously described [6]. The reasons for this observation are uncertain. Sarcoidosis in females may be more severe than males as some studies have suggested a slightly less favorable outcome among females. For example, a report from a Finnish cohort observed that the rate of normalization of chest x-ray at 5 years among females was 19% lower than males [12]. Another study from the United States found that 19% of females with sarcoidosis who did not receive any specific treatments deteriorated compared to 8% of males [13]. In our cohort, females had a significantly higher frequency of extra-thoracic involvement and required treatment with glucocorticoids and immunosuppressive agents more often.

Differences in extra-thoracic manifestations of sarcoidosis between males and females in our cohort were previously described in detail elsewhere, including a higher prevalence of cutaneous involvement in females (25% vs 12%) [14] which may shed some light on why the difference was most prominent in skin/subcutaneous diseases chapter in the current study. The higher prevalence of cutaneous involvement among females with sarcoidosis compared to males with sarcoidosis was observed in other cohorts as well [15–17]. Females with sarcoidosis in the current cohort also had a higher prevalence of chronic diseases including obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension and dyslipidemia which could also predispose them to illnesses that require hospitalization.

Age and sex-adjusted hospitalization rates for patients with sarcoidosis were stable over the studied period. This observation is different from 2 previous U.S. studies using nationwide hospitalization samples that found an increased rate of hospitalization in 2000s compared to 1980s [5, 6]. The difference in the ethnic background of the cohorts is a possible explanation for the conflicting results as the current cohort was predominantly Caucasian (>90%) while the previous studies were more diverse [5, 6]. It has been well demonstrated that the clinical manifestations and outcomes of sarcoidosis are different across ethnic groups which may influence the need for inpatient care [15, 18, 19]. In fact, one study reported that African-Americans with sarcoidosis were hospitalized 9 times more often than Caucasians with sarcoidosis [6]. The results of the current study are in line with the other predominantly Caucasian cohort from Switzerland that also did not observe a significant trend in hospitalization rates from 2002 to 2012 [7].

Interestingly, a study of U.S. Navy personnel revealed a marked decline in hospitalized sarcoidosis from 1975 to 2001 [8]. However, its methodology was significantly different from the current study, as it included only patients who were first diagnosed with sarcoidosis during the hospitalization (i.e., patients who were admitted for investigations for sarcoidosis and were found to have sarcoidosis) and calculated rate of hospitalization based on the number of those patients. The decline in hospitalization rates in that study may reflect change in clinical practice toward outpatient diagnostic evaluation.

There was a significant decline of age and sex-adjusted hospitalization rates among patients with sarcoidosis over the disease duration. As this decline persisted after removing hospitalizations for diagnostic evaluations (such as bronchoscopy and mediastinoscopy) of sarcoidosis at the time of diagnosis, it appears that patients with sarcoidosis have higher hospitalization rates during the early years of their disease duration, which declines over time. This is likely due to the varying clinical course of sarcoidosis, which ranges from an indolent process to an acute self-limited process to a progressive disease with permanent organ damage. Those with an acute self-limited process that resolves would be less likely to be hospitalized many years after sarcoidosis diagnosis. Trend for age and sex-adjusted hospitalization rates per calendar year was not observed for either cases or comparators.

The major strength of this study is that it is a population-based cohort using individual medical record review. Thus, the accuracy of the diagnosis was high and the risk of disease misclassification was minimal, unlike previous coding-based studies. Moreover, the comprehensive resources of REP database allows a complete identification of all hospitalizations while those coding-based studies may not be able to identify all episodes of inpatient care if diagnostic codes for sarcoidosis were not recorded as admission/discharge diagnoses.

The use of CCS is also advantageous as it conforms to national data and would allow an easy comparison with future studies. However, the lack of granularity of diagnoses of CCS chapters is one of the limitations as it may have led to ambiguity in the classification of the diseases into the chapters. The primary discharge diagnosis for each hospitalization was made by healthcare providers who cared for the patient during that hospitalization. Variation in how individual providers determined the primary diagnosis or how the diagnoses were coded during the billing process could decrease the accuracy of the analysis by CCS chapter. Hospitalizations that occurred outside Olmsted County would have been missed as the database could capture only hospitalizations within the County. Nonetheless, it is unlikely that the rate of out-of-county hospitalization would be significantly different between cases and comparators. Finally, as previously discussed, the epidemiology and clinical phenotypes of sarcoidosis vary across different ethnic groups. Thus, generalizability of the results of this study, which is based on a predominantly Caucasian cohort, may be limited.

Conclusion

In this population, females with sarcoidosis had a significantly higher rate of hospitalization compared to female without sarcoidosis. In contrast, the rate of hospitalization among males with and without sarcoidosis was not significantly different. Further investigation may illuminate reasons for these findings.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was made possible using the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project, which is supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AG034676, and CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of interest

None

Conflict of interest statement for all authors: The authors have no financial or non-financial potential conflicts of interest to declare. Dr. Carmona is a CO-I in a registry for patients with sarcoidosis associated pulmonary hypertension. The study is funded by Gilead.

References

- 1.Judson MA, Thompson BW, Rabin DL, et al. The diagnostic pathway to sarcoidosis. Chest. 2003;123:406–412. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.2.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newman LS, Rose CS, Bresnitz EA, et al. A case control etiologic study of sarcoidosis: environmental and occupational risk factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:1324–1330. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200402-249OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baughman RP, Field S, Costabel U, et al. Sarcoidosis in America. Analysis based on health care use. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 13:1244–1452. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201511-760OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen ES, Moller DR. Etiology of sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2008;29:365–377. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerke AK, Yang M, Tang F, et al. Increased hospitalizations among sarcoidosis patients from 1998 to 2008: a population-based cohort study. BMC Pulm Med. 2012;12:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-12-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foreman MG, Mannino DM, Kamugisha L, et al. Hospitalization for patients with sarcoidosis: 1979–2000. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2006;23:124–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pohle S, Baty F, Brutsche M. In-hospital disease burden of sarcoidosis in Switzerland from 2002 to 2012. Plos ONE. 2016;11:e0151940. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorham ED, Garland CE, Garland FC, et al. Trends and occupational associations in incidence of hospitalized pulmonary sarcoidosis and other lung diseases in Navy personnel. A 27-year historical prospective study 1975–2001. Chest. 2004;126:1431–1438. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.5.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ungprasert P, Carmona EM, Utz JP, et al. Epidemiology of sarcoidosis 1946–2013: A population-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, et al. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: Half a century of medical records linkage in a U.S. population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:1202–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. HCUPnet; http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/ [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pietinalho A, Ohmichi M, Lofroos AB, et al. The prognosis of pulmonary sarcoidosis in Finland and Hokkaido, Japan. A comparative five-year of biopsy-proven cases. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2000;200017:158–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunninghake GW, Gilbert S, Oueringer R, et al. Outcome of the treatment of sarcoidosis. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 1994;149:893–898. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.4.8143052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ungprasert P, Crowson CS, Matteson EL. Influence of gender on epidemiology and clinical manifestations of sarcoidosis: a population-based retrospective cohort study 1976–2013. Lung. 2017;195:87–91. doi: 10.1007/s00408-016-9952-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brito-Zeron P, Sellares J, Bosch X. Epidemiologic patterns of disease expression in sarcoidosis: age, gender and ethnicity-related differences. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016;34:380–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Judson MA, Boan AF, Lackland DT. The clinical course of sarcoidosis: presentation, diagnosis, and treatment in a large white and black cohort in the United States. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2012;29:119–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yanardag H, Nuri Pamuk O, Karayel T. Cutaneous involvement in sarcoidosis: analysis of the features in 170 patients. Respir Med. 2003;97:978–982. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(03)00127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mirsaedi M, Machado RF, Schraufnagel D, et al. Racial difference in sarcoidosis mortality in the United States. Chest. 2015;147:438–449. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rabin DL, Thompson B, Brown KM, et al. Sarcoidosis: social predictors of severity at presentation. Eur Resp J. 2004;24:601–608. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00070503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]