Abstract

Urothelial carcinoma (UC), arising from the urothelium of the urinary tract, can occur in the upper (UTUC) and the urinary bladder (UBUC). A representative molecular aberration for UC characteristics and prognosis remains unclear. Data mining of Gene Expression Omnibus focusing on UBUC, we identified sulfatase-1 (SULF1) upregulation is associated with UC progression. SULF1 controls the sulfation status of heparan sulfate proteoglycans and plays a role in tumor growth and metastasis, while its role is unexplored in UC. To first elucidate the clinical significance of SULF1 transcript expression, real-time quantitative RT-PCR was performed in a pilot study of 24 UTUC and 24 UBUC fresh samples. We identified that increased SULF1 transcript abundance was associated with higher primary tumor (pT) status. By testing SULF1 immunoexpression in independent UTUC and UBUC cohorts consisted of 340 and 295 cases, respectively, high SULF1 expression was significantly associated with advanced pT and nodal status, higher histological grade and presence of vascular invasion in both UTUC and UBUC. In multivariate survival analyses, high SULF1 expression was independently associated with worse DSS (UTUC hazard ratio [HR] = 3.574, P < 0.001; UBUC HR = 2.523, P = 0.011) and MeFS (UTUC HR = 3.233, P < 0.001; UBUC HR = 1.851, P = 0.021). Furthermore, depletion of SULF1 expression by using RNA interference leaded to impaired cell proliferative, migratory, and invasive abilities in vitro. In addition, we further confirmed oncogenic role of SULF1 with gain-of function experiments. In conclusion, our findings implicate the oncogenic role of SULF1 expression in UC, suggesting SULF1 as a prognostic and therapeutic target of UC.

Keywords: urothelial carcinoma, transcriptome, SULF1, prognosis

INTRODUCTION

Urothelial carcinomas (UCs) arising from the transitional epithelium of the urinary tract are the fourth most common tumors after prostate (or breast), lung and colorectal cancers [1]. These carcinomas grow in the upper urinary tract (pyelocaliceal cavities and ureter) or lower urinary tract (bladder and urethra). Bladder cancer is the most common malignancy of the urinary tract and accounts for 90–95% of UCs [2]. Upper tract urothelial carcinomas (UTUCs) are relatively rare compared with urinary bladder UCs (UBUCs) in Western society [3]. The male-to-female ratio of UTUC is approximately 2-3:1, and pyelocaliceal tumors are approximately two to three times as common as ureteral tumors [4]. However, UTUC accounts for up to 30% of all UCs in Taiwan, and the incidence is approximately equal in men and women, similar to renal pelvis and ureter events [5]. UCs are characterized by frequent recurrence, and even with early diagnosis, poor clinical outcomes were reported with progression into advanced or metastatic disease [6]. Currently, no biomarkers can fulfill the clinical and statistical criteria for better cancer detection, outcome prediction, treatment decision-making or therapy monitoring. Therefore, identification of novel prognostic molecular markers for UC development and progression is needed.

Heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) play essential roles in various biological processes and organ systems. These substances are located on the surfaces of most animal cells and represent a crucial element of the extracellular matrix (ECM). HSPGs are composed of a restricted set of core proteins to which are covalently linked one or more heparan sulfate (HS) glycosaminoglycan (GAG) chains. The great diversity of HS structures includes the length and size of the sulfated and non-sulfated regions as well as disaccharide composition [7–8]. The variations differ in specific ways and are dynamically managed at distinct cell type and tissue levels, during development, and in pathological statuses such as cancer progression. These markers manifest the primary principle dictating that HS-ligand interactions are largely dependent on specific sulfation patterns in segments of the chain with distinct docking sites for the various ligands [9–10].

Human sulfatase-1 and sulfatase-2 (SULF1 and SULF2, hereafter referred to as the SULFs) are novel enzymes discovered in the early 2000s that control the sulfation status of HSPGs and demonstrate up- or down-regulation in different types of malignancies to promote or repress tumor growth and metastasis [11]. According to the previous literature, SULF1 and SULF2 may have opposing effects in cancer progression despite similar structures and activities. Earlier evidence has shown that SULF1 downregulates multiple signaling pathways via HS-binding growth factors such as FGF2, HGF, HB-EGF, VEGF, PDGF and amphiregulin. In this respect, SULF1 displayed tumor suppressor function in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), ovarian cancer, kidney cancer and multiple myeloma [12]. However, more recent studies revealed over-expressed SULF1 in cancers such as pancreatic, gastric, and lung adenocarcinoma, glioma, invasive breast carcinoma, and leukemia, which exhibited protumorigenic effects [13–16]. Overall, these divergent results highlight a poor understanding of the complicated mechanisms and multifactorial implications of the SULF1 in cancers.

The role of SULF1 in UCs is limited according to known information. We conducted this study to evaluate the expression status of SULF1 associated with disease states in human UCs. Furthermore, we assessed the effects of SULF1 on patient survival and identified that the expression of SULF1 is a prognostic biomarker in UCs.

RESULTS

SULF1 identified as a significant differentially upregulated gene implicated in tumor progression in UBUC

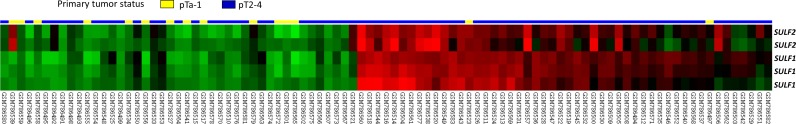

Using data mining from published transcriptomic datasets of UBUCs (GSE31684 and GSE32894), SULF1 and SULF2 were identified as significant genes showing upregulation during tumor progression among those associated with the heparan sulfate proteoglycan metabolic process (GO:0030201) (Figure 1, Supplementary Figure 1 and Table 1, Supplementary Table 1). Of these SULF1 showed a log2 ratio of 2.8929 and 1.4253-fold upregulation and SULF2 showed 1.7641 and 0.7979-fold upregulation in GSE31684 and GSE32894, respectively.

Figure 1. Reappraisal of transcriptome dataset in urothelial carcinoma (GSE31684).

Clustering analysis of genes focusing on those involving heparan sulfate proteoglycan metabolic process revealed SULF1 is the most significantly up-regulated gene associated with increments of pT status, followed by SULF2, prompting us to further validate their significance. Tissue specimens from tumors with different pT statuses are indicated on top of the heatmap, and expression levels of up-regulated and down-regulated genes are represented as a spectrum of brightness or red and green, respectively. Cases unaltered in mRNA transcriptional level are coded black.

Table 1. Summary of differentially expressed genes associated with heparan sulfate proteoglycan metabolic process in the transcriptome of urothelial carcinoma of urinary bladder (GSE31684).

| Probe | Comparing T2-4 to Ta-T1 | Gene Symbol | Biological Process | Molecular Function | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| log ratio | p-value | ||||

| 212353_at | 2.8929 | 0 | SULF1 | apoptosis, heparan sulfate proteoglycan metabolic process, metabolic process | arylsulfatase activity, calcium ion binding, hydrolase activity, metal ion binding, sulfuric ester hydrolase activity |

| 212354_at | 2.2812 | 0 | SULF1 | apoptosis, heparan sulfate proteoglycan metabolic process, metabolic process | arylsulfatase activity, calcium ion binding, hydrolase activity, metal ion binding, sulfuric ester hydrolase activity |

| 224724_at | 1.7641 | 0 | SULF2 | heparan sulfate proteoglycan metabolic process, metabolic process | arylsulfatase activity, calcium ion binding, hydrolase activity, metal ion binding, sulfuric ester hydrolase activity |

| 212344_at | 1.5038 | 0.0036 | SULF1 | apoptosis, heparan sulfate proteoglycan metabolic process, metabolic process | arylsulfatase activity, calcium ion binding, hydrolase activity, metal ion binding, sulfuric ester hydrolase activity |

| 233555_s_at | 0.9063 | 0.001 | SULF2 | heparan sulfate proteoglycan metabolic process, metabolic process | arylsulfatase activity, calcium ion binding, hydrolase activity, metal ion binding, sulfuric ester hydrolase activity |

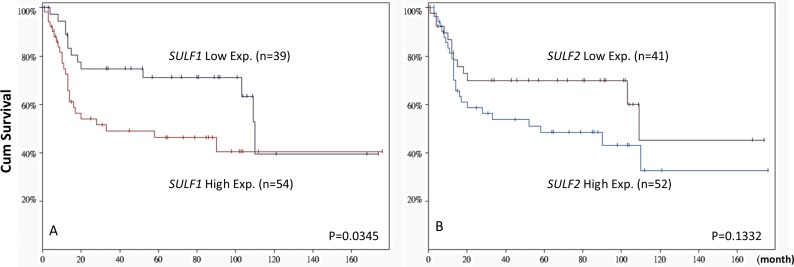

SULF1 but not SULF2 transcript expression predicts survival in UBUC transcriptomic dataset

Subdividing 93 cases from GSE31684 into SULF1 high-expression (n = 54) and low-expression (n = 39) clusters showed that a high expression level of SULF1 significantly determined worse patient survival (P = 0.0345, Figure 2). However, high SULF2 expression (n = 52) did not significantly predict patient outcome (P = 0.1332). The findings prompt us to further characterize the significance of SULF1 transcript and protein expression in our large cohort of urothelial carcinoma.

Figure 2. Patient outcome stratified by SULF1 and SULF2 transcript levels based on GSE31684.

The expression level of SULF1 significantly predicts worse patient outcome (left, P = 0.0345). While SULF2 expression status is not predictive for patient survival (right, P = 0.1332).

Higher SULF1 mRNA expression is associated with advanced pT stages in both UTUC and UBUC

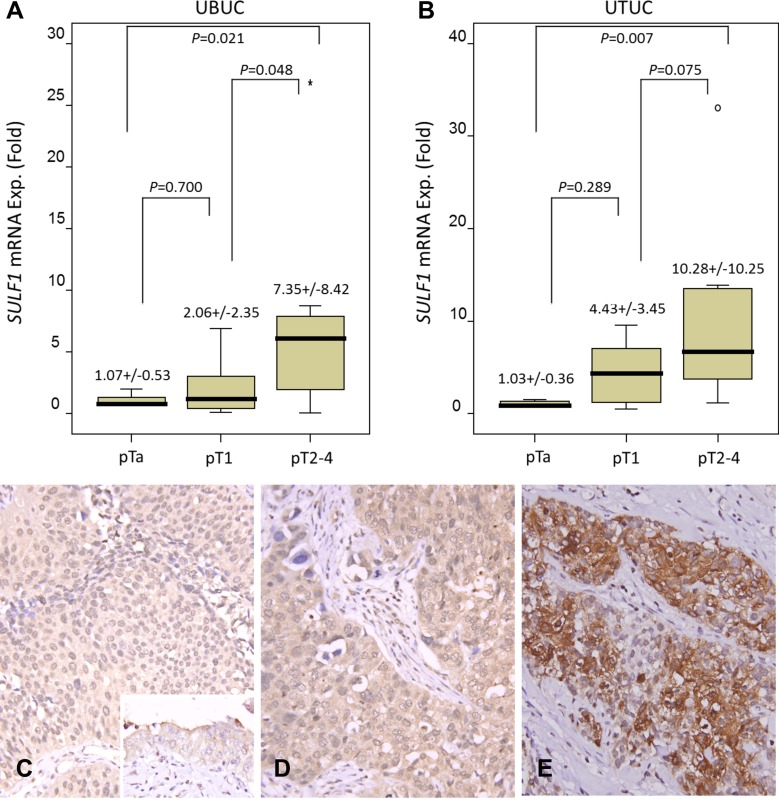

The SULF1 mRNA expression was analyzed in both UTUC and UBUC samples. It showed SULF1 mRNA expression significantly increased in higher stage tumors in both UTUC (P = 0.007) and UBUC (P = 0.021), verifying the important role of SULF1 in cancer progression (Figure 3A, 3B).

Figure 3. Validation of SULF1 transcript and protein expression.

SULF1 mRNA level was significantly increased in both UBUCs (A) and UTUCs (B) with advanced primary pT status. (p = 0.021 and p = 0.007, respectively). Immunhistochemically, SULF1 is barely detected in non-tumorous urothelium (C, inset) and non-invasive UC (C) and shows a mild increase in superficially invasive UC (D). The representative high-grade and high-stage UC shows a bright SULF1 immunoreactivity (E).

Clinicopathological findings of UTUC

The clinicopathological characteristics of the UTUC patients are listed in Table 2. Between low and high SULF1 expression, gender has no significant difference and the age of patients at diagnosis ranged from 34 to 87 years (median 68). Sixty-two patients (18.2%) had multiple foci tumors, and 49 (14.4%) had tumors in both the renal pelvis and ureter simultaneously. Most patients (n = 284, 83.5%) were high histological grade and advanced pT stages (pT2-T4) were noted in 159 (46.8%) of cases. Around half (n = 167, 49.1%) of the cases showed frequent mitosis. 106 cases (31.2%) and 19 cases (5.9%) presented vascular invasion and perineural invasion, respectively. Nodal metastasis was noted in 28 patients (8.2%).

Table 2. Correlations between SULF1 expression and other important clinicopathological parameters in urothelial carcinomas.

| Parameter | Category | Upper Urinary Tract Urothelial Carcinoma | Urinary Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case No. | SULF1 Expression | p–value | Case No. | SULF1 Expression | p–value | ||||

| Low | High | Low | High | ||||||

| Gender | Male | 158 | 84 | 74 | 0.277 | 216 | 105 | 111 | 0.489 |

| Female | 182 | 86 | 96 | 79 | 42 | 37 | |||

| Age (years) | < 65 | 138 | 75 | 63 | 0.185 | 121 | 50 | 71 | 0.015* |

| ≥ 65 | 202 | 95 | 107 | 174 | 97 | 77 | |||

| Tumor location | Renal pelvis | 141 | 64 | 77 | 0.344 | – | – | – | – |

| Ureter | 150 | 79 | 71 | – | – | – | – | ||

| Renal pelvis & ureter | 49 | 27 | 22 | – | – | – | – | ||

| Multifocality | Single | 278 | 138 | 140 | 0.779 | – | – | – | – |

| Multifocal | 62 | 32 | 30 | – | – | – | – | ||

| Primary tumor (T) | Ta | 89 | 60 | 29 | < 0.001* | 84 | 57 | 27 | < 0.001* |

| T1 | 92 | 47 | 45 | 88 | 54 | 34 | |||

| T2-T4 | 159 | 63 | 96 | 123 | 36 | 87 | |||

| Nodal metastasis | Negative (N0) | 312 | 164 | 148 | 0.002* | 266 | 142 | 124 | < 0.001* |

| Positive (N1–N2) | 28 | 6 | 22 | 29 | 5 | 24 | |||

| Histological grade | Low grade | 56 | 36 | 20 | 0.019* | 56 | 37 | 19 | 0.007* |

| High grade | 284 | 134 | 150 | 239 | 110 | 129 | |||

| Vascular invasion | Absent | 234 | 133 | 101 | < 0.001* | 246 | 134 | 112 | < 0.001* |

| Present | 106 | 37 | 69 | 49 | 13 | 36 | |||

| Perineural invasion | Absent | 321 | 162 | 159 | 0.479 | 275 | 141 | 134 | 0.066 |

| Present | 19 | 8 | 11 | 20 | 6 | 14 | |||

| Mitotic rate (per 10 high power fields) | < 10 | 173 | 94 | 79 | 0.104 | 139 | 76 | 63 | 0.116 |

| > = 10 | 167 | 76 | 91 | 156 | 71 | 85 | |||

*Statistically significant.

Clinicopathological findings of UBUC

Of the 295 UBUC cases, male (n = 216, 73.2%) is more than female. As shown in Table 2, 239 (81%) patients had high histological grades, and 123 cases (41.7%) were at a muscle-invasion stage (pT2-T4) during diagnosis. High mitotic activity (≥ 10) and lymph node metastasis were found in 156 cases (52.9%) and 29 cases (23.6%), respectively. In addition, 49 cases (16.6%) have vascular invasion and perineural invasion were present in 20 cases (6.8%).

Correlations of immunoreactivity of SULF1 and SULF2 with clinicopathological features of UTUC and UBUC

SULF1 and SULF2 show variable cytoplasmic expression in both UTUC and UBUC. The tumors were dichotomized into those with low and high SULF1 expression, as demonstrated in Figure 3C–3E, Table 2, high SULF1 expression was significantly associated with age less than 65 (UBUC, P = 0.015), more advanced primary tumor pT stage (P < 0.001, both UTUC and UBUC), lymph node metastasis (UTUC, P = 0.002; UBUC, P < 0.001), higher histological grade (UTUC, P = 0.019; UBUC, P = 0.007) and vascular invasion (P < 0.001, both UTUC and UBUC) in urothelial carcinomas. As showed in Supplementary Figure 2, high-grade and high-stage UC shows a bright SULF2 immunoreactivity. The clinicopathological associations of SULF2 expression in UTUC and UBUC patients are listed in Supplementary Table 2. Renal pelvis location, single site tumor, advanced pT stages, lymph node metastasis, high grade, vascular invasion, higher mitotic rate present high SULF2 expression in UTUC significantly. Advanced pT stages, lymph node metastasis, high grade present high SULF2 expression in UBUC significantly.

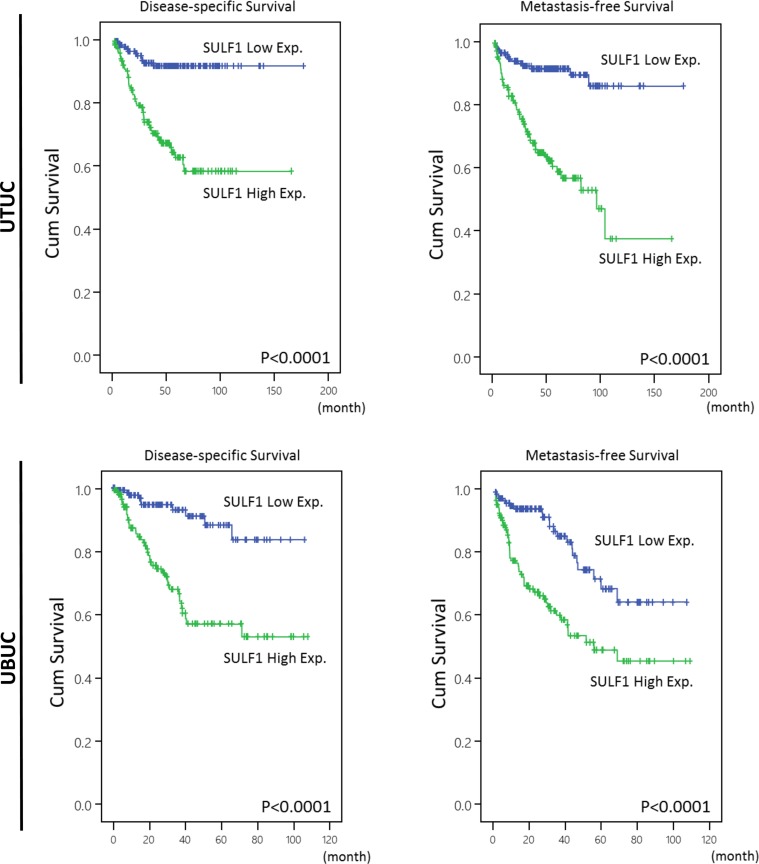

Survival analysis for UTUC

Table 3 showed univariate and multivariate analyses of the association between clinical outcomes and various clinicopathological features of UTUC cases. In univariate and multivariate analysis, high SULF1 immunoexpression together with a number of important clinicopathological factors including tumor multifocality, higher primary tumor pT stage status, nodal status, high histological grade, and perineurial invasions were predictive of worse outcomes in terms of disease-specific survival (DSS). After univariate and multivariate analysis in metastasis-free survival (MeFS), high SULF1 expression, tumor multifocality, nodal metastasis, high histological grade, vascular and perineural invasion remained as independently significant prognosticators. From Kaplan-Meier analysis, high expression of SULF1 also predict significantly worse DSS (Hazard Ratio [H.R.] = 3.574, P < 0.001) and MeFS (H.R. = 3.233, P < 0.001) in UTUC (Figure 4, upper panel). As shown in Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Figure 3, high expression of SULF2 predicts significantly worse MeFS (P = 0.026) but not DSS and is not enrolled into multivariate survival analysis.

Table 3. Univariate log-rank and multivariate analyses for disease-specific and metastasis-free survivals in upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma.

| Parameter | Category | Case No. | Disease-specific Survival | Metastasis–free Survival | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||||||

| No. of event | p-value | R.R. | 95% C.I. | p–value | No. of event | p–value | R.R. | 95% C.I. | p–value | |||

| Gender | Male | 158 | 28 | 0.8286 | – | – | – | 32 | 0.7904 | – | – | – |

| Female | 182 | 33 | – | – | – | 38 | – | – | – | |||

| Age (years) | < 65 | 138 | 26 | 0.9943 | – | – | – | 30 | 0.8470 | – | – | – |

| ≥ 65 | 202 | 35 | – | – | – | 40 | – | – | – | |||

| Tumor side | Right | 177 | 34 | 0.7366 | – | – | – | 38 | 0.3074 | – | – | – |

| Left | 154 | 26 | – | – | – | 32 | – | – | – | |||

| Bilateral | 9 | 1 | – | – | – | 0 | – | – | – | |||

| Tumor location | Renal pelvis | 141 | 24 | 0.0079* | 1 | – | 0.536 | 31 | 0.0659 | – | – | – |

| Ureter | 150 | 22 | 0.873 | 0.472–1.615 | 25 | – | – | – | ||||

| Renal pelvis & ureter | 49 | 15 | 2.139 | 0.584–7.837 | 14 | – | – | – | ||||

| Multifocality | Single | 273 | 48 | 0.0026* | 1 | – | 0.009* | 52 | 0.0127* | 1 | – | 0.002* |

| Multifocal | 62 | 18 | 2.734 | 1.290–5.795 | 18 | 2.452 | 1.407–4.308 | |||||

| Primary tumor (T) | Ta | 89 | 2 | < 0.0001* | 1 | – | 0.015* | 4 | < 0.0001* | 1 | – | 0.250 |

| T1 | 92 | 9 | 2.388 | 0.501–11.386 | 15 | 2.099 | 0.677–6.511 | |||||

| T2–T4 | 159 | 50 | 4.935 | 1.094–22.250 | 51 | 2.216 | 0.693–7.088 | |||||

| Nodal metastasis | Negative (N0) | 312 | 42 | < 0.0001* | 1 | – | < 0.001* | 55 | < 0.0001* | 1 | – | 0.001* |

| Positive (N1–N2) | 28 | 19 | 5.155 | 2.757–9.639 | 15 | 2.795 | 1.501–5.203 | |||||

| Histological grade | Low grade | 56 | 4 | 0.0215* | 1 | – | 0.024* | 3 | 0.0027* | 1 | – | 0.019* |

| High grade | 284 | 57 | 3.658 | 1.184–11.298 | 67 | 4.345 | 1.267–14.901 | |||||

| Vascular invasion | Absent | 234 | 24 | < 0.0001* | 1 | – | 0.344 | 26 | < 0.0001* | 1 | – | 0.008* |

| Present | 106 | 37 | 1.353 | 0.724–2.529 | 44 | 2.362 | 1.252–4.457 | |||||

| Perineural invasion | Absent | 321 | 50 | < 0.0001* | 1 | – | < 0.001* | 61 | < 0.0001* | 1 | – | 0.005* |

| Present | 19 | 11 | 4.297 | 2.038–9.059 | 9 | 2.930 | 1.381–6.219 | |||||

| Mitotic rate (per 10 high power fields) | < 10 | 173 | 27 | 0.167 | – | – | – | 30 | 0.0823 | – | – | – |

| > = 10 | 167 | 34 | – | – | – | 40 | – | – | – | |||

| SULF1 expression | Low | 170 | 11 | < 0.0001* | 1 | – | < 0.001* | 14 | < 0.0001* | 1 | – | < 0.001* |

| High | 170 | 50 | 3.574 | 1.818–7.027 | 56 | 3.233 | 1.773–5.895 | |||||

* Statistically significant.

Figure 4. Kaplan-Meier plots of disease-specific survival (DSS) and metastasis-free survival (MeFS) of UTUCs and UBUCs.

SULF1 expression significantly predicts inferior DSS and MeFS in UTUC and UBUC (all P < 0.0001).

Survival analysis for UBUC

After analyzing in UBUC, a list of clinicopathological variables significantly predicted worse DSS and MeFS, including advanced pT stage and nodal status, higher histological grade, the presence of vascular and perineurial invasions and higher mitotic activity in univariate analysis, shown in Table 4. Of note, high SULF1 expression not only significantly predicted worse outcome in both univariate and multivariate analysis but also significantly impacted DSS (H.R. = 2.523, P = 0.011) and MeFS (H.R. = 1.851, P = 0.021) in Kaplan-Meier analysis (Figure 4, lower panel). SULF2 expression is not predictive for worse patient outcome.

Table 4. Univariate log-rank and multivariate analyses for disease-specific and metastasis-free survivals in urinary bladder urothelial carcinoma.

| Parameter | Category | Case No. | Disease-specific Survival | Metastasis–free Survival | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||||||

| No. of event | p–value | R.R. | 95% C.I. | p–value | No. of event | p–value | R.R. | 95% C.I. | p–value | |||

| Gender | Male | 216 | 41 | 0.4446 | – | – | – | 60 | 0.2720 | – | – | – |

| Female | 79 | 11 | – | – | – | 16 | – | – | – | |||

| Age (years) | < 65 | 121 | 17 | 0.1136 | – | – | – | 31 | 0.6875 | – | – | – |

| ≥ 65 | 174 | 35 | – | – | – | 45 | – | – | – | |||

| Primary tumor (T) | Ta | 84 | 1 | < 0.0001* | 1 | – | 0.001* | 4 | < 0.0001* | 1 | – | 0.012* |

| T1 | 88 | 9 | 6.192 | 0.672–57.068 | 23 | 5.076 | 1.476–17.454 | |||||

| T2–T4 | 123 | 42 | 20.271 | 2.267–181.274 | 49 | 6.639 | 1.911–23.057 | |||||

| Nodal metastasis | Negative (N0) | 266 | 41 | 0.0002* | 1 | – | 0.489 | 61 | < 0.0001* | 1 | – | 0.068 |

| Positive (N1–N2) | 29 | 11 | 1.281 | 0.635–2.586 | 15 | 1.768 | 0.959–3.260 | |||||

| Histological grade | Low grade | 56 | 2 | 0.0013* | 1 | – | 0.921 | 5 | 0.0007* | 1 | – | 0.675 |

| High grade | 239 | 50 | 1.081 | 0.230–5.082 | 71 | 1.250 | 0.440–3.550 | |||||

| Vascular invasion | Absent | 246 | 37 | 0.0024* | 1 | – | 0.166 | 54 | 0.0001* | 1 | – | 0.827 |

| Present | 49 | 15 | 0.618 | 0.313–1.221 | 22 | 0.937 | 0.522–1.682 | |||||

| Perineural invasion | Absent | 275 | 44 | 0.0001* | 1 | – | 0.081 | 66 | 0.0007* | 1 | – | 0.235 |

| Present | 20 | 8 | 2.90 | 0.914–4.778 | 10 | 1.561 | 0.748–3.256 | |||||

| Mitotic rate (per 10 high power fields) | < 10 | 139 | 12 | < 0.0001* | 1 | – | 0.014* | 23 | < 0.0001* | 1 | – | 0.011* |

| > = 10 | 156 | 40 | 2.313 | 1.182–4.526 | 53 | 1.952 | 1.164–3.273 | |||||

| SULF1 expression | Low | 147 | 10 | < 0.0001* | 1 | – | 0.011* | 22 | < 0.0001* | 1 | – | 0.021* |

| High | 148 | 42 | 2.523 | 1.233–5.165 | 54 | 1.851 | 1.098–3.119 | |||||

* Statistically significant.

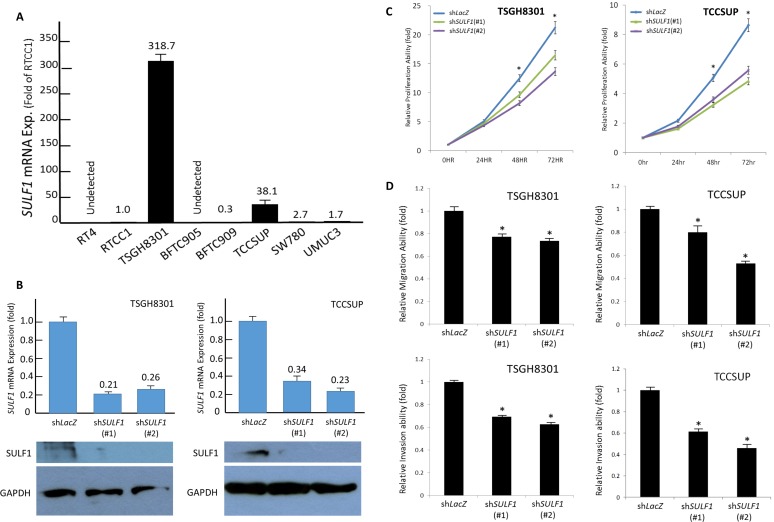

SULF1 promotes in vitro aggressiveness of UC cells

The above-mentioned results prompted us to further work on the biological significances of SULF1 expression UC. We first evaluated the endogenous SULF1 expression by using real-time quantitative RT-PCR in a list of UC cell lines and identified TSGH8301 and TCCSUP have most abundant SULF1 transcript level. To further clarify whether SULF1 modulates cell aggressiveness, we performed SULF1 knockdown by means of short hairpin RNA to deplete SULF1 expression in TSGH8301 and TCCSUP cells. Evaluated by (2,3-bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide) XTT, modified Boyden chamber migration and invasion assays, we identified depletion of SULF1 leaded to significant diminished cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. These findings demonstrated that SULF1 promotes in vitro aggressiveness of UC cells (Figure 5).

Figure 5. SULF1 expression promotes growth of UC cells in vitro.

TSGH8301 and TCCSUP cell lines reveal the most abundant SULF1 transcript level (A). These two cell lines with high endogenous SULF1 expression are stably silenced against SULF1 expression by a lentiviral vector bearing one of the two clones of SULF1 short hairpin (sh)RNA with different sequences for both TSGH8301 and TCCSUP cells. The efficiency of RNA silencing is confirmed by both quantitative RT-PCR (upper) and western blotting (lower) assays (B). Using 2,3-bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide (XTT), we confirmed depletion of SULF1 impairs cell growth (C) as well as cell migration (D, upper) and invasion abilities (D, lower).(*P < 0.05).

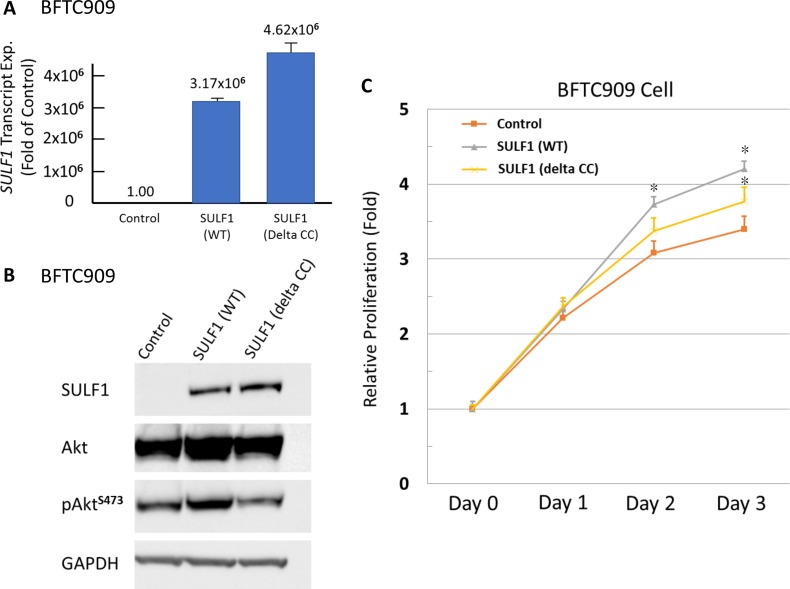

SULF1 expression promotes in vitro proliferation of UC cells

It revealed a low SULF1 transcript expression in BFTC909 cell lines (Figure 5A) which is eligible for gain-of function experiments by using wild-type (WT) and mutant (delta CC, with impaired enzymatic function) SULF1 (Figure 6A). We identified SULF1 (WT) significantly promoted cell proliferation while the effect is significantly diminished but not completely lost by a delta CC mutation (Figure 6B, 6C). The western blotting showed Akt phosphorylation increased by exogenous wild-type SULF1 expression but not in that with delta CC mutation, suggesting a role of SULF1 enzymatic function in activating Akt pathway to promote it oncogenic nature. Of interest, SULF1 also leaded to significantly increased cancer cell migration and invasion, which were not depleted by delta CC mutation (Supplementary Figure 4). These findings not only confirmed the oncogenic role of SULF1 in promoting cell proliferation, migration, and invasiveness, but also first disclosed the oncogenic role of SULF1 might be related to but not totally relay on its enzymatic function.

Figure 6. Exogenous SULF1 expression promotes UC cells proliferation in vitro.

Exogenous expression of wild-type and mutant (delta CC) SULF1 has been performed in SULF1-low-expressing BFTC909 cell line. The efficiency is confirmed by both quantitative RT-PCR (A) and western blotting assays (B). The significant increased phosphorylated Akt can be detected in that with wild-type SULF1, while not in that with delta CC mutation, suggesting the activation of Akt pathway is associated with enzymatic function of SULF1. Exogenous expression of wild-type SULF1 significantly promotes cell proliferation (C). That with delta CC mutated SULF1 revealed a proliferation rate between control cells and that with wild-type SULF1, indicating the oncogenic role of SULF1 may be partly relay on its enzymatic function.

DISCUSSION

UC presents either a noninvasive or invasive pattern with different management approaches and prognoses. When a patient with UC progresses to an advanced stage, the survival rate is dramatically decreased if standard treatment is received. A study revealed that the 5-year survival rate in non-muscle invasive UC (pTa, pTis and pT1 stages) was greater than 90% but decreased to less than 50% for pT3 stage and to 5% for pT4 stage [17]. For early identification of patients with potential for advanced status, we must find significant prognostic factors and therapeutic markers for UC and design individualized plans of treatment and surveillance. Modern technologies have been used to identify a variety of molecular markers for this purpose.

Experiments illustrated the crucial characters of HS chains from global HS deficiency in mice that resulted in extraordinary gastrulation leading to embryonic death [7]. Because HSPGs have the ability to bind a large diversity of ligands (namely, cytokines, chemokines, morphogens, enzymes, receptors, growth factors, matrix/adhesion molecules, and plasma proteins), they modulate nutritional metabolism, organize basement membrane barriers, regulate cell signaling and morphogenesis and are involved in cellular crosstalk as well as participate in injury and repair. In the tumor microenvironment, these modifications are known to significantly influence cancer progression, metastasis and prognosis [18].

A number of studies have reported that biosynthesis of HS influenced cell transformation and evolution through the different stages of cancers, including desulfation of 6-O-sulfate [7, 19]. Many researchers also demonstrated the ability of SULF1 and SULF2 in editing post-synthetic sulfation status of 6-O-S from HSPGs, and thus the implication and potential roles of SULFs in malignancies were extensively investigated [20, 21]. However, the precise functions of SULFs in regulatory mechanisms and molecular interactions in a variety of tumors remain unclear. Our study depicted the oncogenic character of SULF1 in UC progression. The major findings of the current study reveal that upregulation of SULFs is found in UCs, and overexpression of SULF1 proteins correlates with worse survival in both UTUC and UBUC patients.

In 2001, Dhoot and colleagues first proved that SULF1 positively regulates the Wnt signaling pathway in embryonic quail (QSULFs). The orthologs and isoforms of QSULF1 were subsequently identified in species including humans (so-called SULF1 and SULF2). Even if the two SULFs are structurally similar, they are unique and markedly different from other members of the sulfatase family. Most of the previously recognized cellular sulfatases cleave sulfate esters from the terminus of the chains (exosulfatases) within the acidic conditions of the lysosomal compartment (intracellular). SULFs localized at the plasma membrane or secreted into the ECM (extracellular) are endoglucosamine-6-sulfatases and show sequence heterology with other sulfatases. These substances selectively catalyze removal of 6-O-sulfate groups, mainly from the S domains of heparan sulfate polymers [22, 23].

Many studies have shown that SULF1 and SULF2 are involved in multiple cellular signaling pathways by modulation of the binding and activating properties of a variety of protein ligands to HS/heparin. Depending on the different SULFs involved, the targeted HS ligands, and the biochemical situations, these pathways are prompted or inhibited and result in pro- or anti-tumor effects. For instance, SULFs have been demonstrated to weaken the affinity of HSPGs for Wnt ligands, which activate signal transduction of Frizzled (Fz) receptors and construct the HS/Wnt/Fz functional compound. This mechanism inducts a series of cytoplasmic reactions that accumulate β-catenin in the nucleus and trigger the Wnt signaling pathway. Via a similar mechanism, BMP4 signaling was enhanced with the action of SULFs via release of an HSPG-binding inhibitor (Noggin) of BMP from the cell surface. GDNF signaling was also reported to be activated by SULFs during mouse neuronal cell protection/regeneration and spermatogenesis [24–26]. By releasing ligands from immobilized HS/heparin (decrease binding ability), SULFs increase the engagement of ligands with receptors and consequently turn on the signaling pathways downstream.

In contrast to upregulation on signaling, SULF1 inhibited the signaling response to several ligands such as HGF, HB-EGF, VEGF, FGF1, FGF2, TGF-β and amphiregulin. Sonic Hedgehog (shh) signaling was enhanced during embryonic development and axonal guidance but repressed in gastric cancer by SULF1. The manifestation may be distinctive depending on different stage of the cancer and the hypoxic level in the tumor microenvironment [27].

FGF2 is a powerful angiogenic factor for HCC. The effects of SULF1 as a tumor suppressor have been identified in HCC for mediating the inhibition of HS-dependent receptor tyrosine kinase signaling in in vitro and in vivo mouse xenografts. Moreover, knockdown of SULF1 by SULF1-targeting short hairpin RNA (shRNA) constructs significantly attenuated apicidin-induced inhibition of HCC cell migration. Nevertheless, higher expression of SULF1 in HCC tissues at a level 1.5× greater than that of adjacent benign tissues was noted in a third of HCCs. In addition, nearly 40% of patients with high tumor SULF1 expression have the hepatoblast phenotype of HCC, which showed relatively poor survival [28]. The complicated interaction between SULF1 and anti-/pro-tumorigenic signaling molecules signifies its bimodal effect in HCC. It is also interesting that Lai et al. showed a combination of apicidin and doxorubicin leads to an increased DNA-damage and apoptosis in SULF1-expressing HCC cells in vitro and invivo [29].

In breast and ovarian cancers, SULF1 exhibition of a tumor suppressive effect was relevant to its ability to attenuate FGF2, HB-EGF, and amphiregulin signaling. According to studies by Liu et al., restoring the expression of SULF1 on ovarian cancer resulted in reduced tumor development and angiogenesis and increased efficacy of anti-cancer agents such as cisplatin [30–31]. SULFs are known to activate Wnt signaling cascade in pancreatic adenocarcinomas, which implies that their higher expression contributes to progression and tumorigenicity of pancreatic cancers. SULF1 mRNA levels in pancreatic cancer samples have been reported as increased compared with normal tissuein these patients, although SULFs were shown to attenuate other pro-tumorigenic signaling pathways and subsequently interfere with cancer advancement, e.g., inhibition of angiogenesis and tumorigenesis by SULF1 in vivo [32–33].

Our study showed that high expression of SULF1 was associated with worse prognosis and higher risk of metastasis in both UTUCs and UTUBs. In addition, high SULF1 expression correlates with advanced T-stage, nodal metastasis, higher grade, and vascular invasion, and the results can also be identified from our functional study, not only knockdown of SULF1 expression, but also over-expression SULF1 in vitro experiments which demonstrated that SULF1 promotes tumor migration and invasion ability. Interestingly, we identify the phosphorylation of Akt is increased by exogenous wild-type SULF1 but not that with delta CC mutation. Akt is known to fully activated after phosphorylation at two regulatory residues, a threonine residue (p-AktThr308) on the kinase domain and a serine residue (p-AktSer473) on the C-terminal hydrophobic motif. The fully active Akt is known to impact various substrates related to the regulation of cell proliferation and inhibition of apoptosis by phosphorylation downstream substrate so related to cellular survival [34]. Meanwhile, although delta CC mutant SULF1 revealed less pAkt protein, it also can promote cancer cell proliferation, migration and invasion. The phenomenon indicates the oncogenic role of SULF1 may not only from its enzymatic function and may have alternative activating pathways than Akt signaling. However, the exact pathway still needs to be clarified. This trend was also detected in SULF2, although no statistical significance was found. In our results, high SULF2 expression is only associated with worse MeFS in UTUC. Our findings suggest that SULF1 plays a critical role in advanced UCs and shows that SULF1 overexpression has important clinical implications as a prognostic and predictive factor in UCs. Since the imperative role of SULF1 expression was demonstrated from our result, it can considered for clinical application in development of therapy targeting SULF1 or as a biomarker for diagnosis and surveillance strategies. In addition, the SULF1 level may be added to a prognostic model in patients with UCs.

In conclusion, our study found that increased SULF1 expression is significantly predictive of more advanced tumor stage and poorer metastasis-free survival and disease-specific survival in patients with both UTUC and UBUC. These findings demonstrated the oncologic role of SULF1 in UC through SULF1 knockdown and overexpression functional assays. Therefore, SULF1 expression in UCs may be a clinically prognostic factor indicating poor patient survival and a biomarker for development of targeted therapies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data mining to identify SULF1 and SULF2 transcripts in UC progression

We performed data mining on public domain data from the GEO (Gene Expression Omnibus, National Center Biotechnology information, Bethesda, MD, USA) and identified two datasets, GSE31684 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE31684) (Figure 1) and GSE32894 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE32894) (Supplementary Figure 1), which profiled 93 and 308 UBUCs using Affymetrix U133 Plus 2.0 Array and HumanHT-12 V3.0 expression bead chip, respectively. To analyze the expression level, we imported the raw files into the Nexus Expression 3 statistical software (BioDiscovery, EI Segundo, CA, USA). All probes in the analysis were used without preselection or filtering. We performed supervised comparative analysis to examine the statistical significance of differentially expressed genes based on the primary tumor status (pT). For this purpose, we compared the differential expression between high-stage (pT2-pT4) and low-stage (pTa-pT1) UCs to perform functional profiles focusing on those related to the heparan sulfate proteoglycan metabolic process (GO:0030201). Further survival analysis was performed in all cases from GES31684 by separating the cases into high-expression and low-expression clusters to computerize the prognostic impact of SULF1 and SULF2 genes.

Patients and tumor specimens

This study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB10302015) of Chi Mei Medical Center and (KMUHIRB-E(I)-20160023) of Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital. We retrieved urothelial carcinoma cases diagnosed between 1996 and 2004 for immunohistochemical study and survival analysis. A total of 635 consecutively treated well-characterized urothelial carcinomas were enrolled, including 340 tumors originating from the UT and 295 arising from the UB. All patients were treated initially by surgical intervention with curative intent. As a rule, UBUC patients with pT3 or pT4 tumors or with nodal involvement received cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy. However, only 29 of 106 pT3 or pT4 and nodal positive UTUC patients received cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy. The criteria for clinicopathological evaluation were essentially identical to those used in our previous work [35, 36]. Two pathologists (PIL & CFL) re-evaluated the hematoxylin-eosin sections of all cases. For validation of SULF1 transcript level, 24 UTUC and 24 UBUC snap frozen samples with high percentage (> 70%) of tumor components were retrieved.

RNA retraction and quantitative real-time RT-PCR

We extracted total RNA from both cell lines and snap frozen tumor samples using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN). The extracted total RNAs were subjected to reverse-transcription reactions using SuperScript III (Invitrogen) for cDNA synthesis. SULF1 mRNA abundance levels were measured with pre-designed TaqMan assay (Hs00290918_m1) coupled with the ABI StepOnePlus System (Applied Biosystems). We calculated the fold level of expression of SULF1 relative to normal adjacent tissues using a comparative Ct method, and POLR2A (Hs01108291_m1) was used as the internal control for normalization. The protocol was described previously [37, 38, 39].

Cell culture

UC cell lines, including RT4, T24, TCCSUP and J82, were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA 20108, USA). TSGH8301, BFTC-905, and BFTC-909 cell lines were obtained from the Food Industry Research and Development Institute (Hsinchu, Taiwan). The RTCC1 UTUC cell line derived from the renal pelvis was sourced from Professor Lien-Chai Chiang at Kaohsiung Medical University [40]. These cells were cultured on the suggested medium using the conditions described in our previous work [37].

Western blot

The tumor cells were lysed with cell lysis buffer containing 25 μg protein, separated by 4–12% gradient NuPAGE gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Amersham, Bioscience, Buckinghamshire, UK). The membranes were probed with antibodies at 4°C overnight against SULF1 (1:1000, H-41, Santa Cruz), Akt (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), phosphorylated AktSer473 (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology) and GAPDH as a loading control (6C5, 1:10,000, Millipore) after blocking with 5% skimmed milk in TBST buffer at room temperature for 1 hour. The secondary antibody was incubated at room temperature for 1.5 hours, and proteins were visualized by a chemiluminescence system (Amersham Biosciences).

RNA interference

The lentiviral vectors obtained from Taiwan National RNAi Core Facility, including pLKO.1-shLacZ (TRCN0000072223: 5′-TGTTCGCATTAT CCGAACCAT-3′) and pLKO.1-shSULF1 (TRCN0000 051098: 5′- CCCAAATATGAACGGGTCAAA -3′; TRCN 0000051100: 5′- CCAAGACCTAAGAATCTTGAT -3′), were used to set up stably SULF1-silenced clones of TSGH8301 and TCCSUP cell lines with the short-hairpin RNAs against SULF1 expression (shSULF1). These three vectors were transfected into HEK293 cells by Lipofectamine 2000 to create viruses, as previous described [37, 41].

2,3-bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide (XTT)-based assay (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA)

The tumor cells were seeded into 96-well flat-bottom plates with phenol red-free medium at a density of 3000–5000 cells per well for 48 hours. The cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. After 24, 48, or 72 hours of incubation, we removed the culture medium and added 20 μl of XTT reaction solution to each well and incubated the cultures for another 4 hours at 37°C. The optical density was measured with an enzyme-linked-immunosorbent assay (ELISA) microplate reader (GloMax Discover, Promega) for absorbance at a wavelength of 450 nm against a reference wavelength of 630 nm.

Migration and invasion assays

The migration and invasion ability of cells were determined by the Boyden chamber technique (transwell analysis). The cell migration assay was performed with Falcon HTS FluoroBlok 24-well inserts (BD Biosciences). The 24-well Collagen-Based Cell Invasion Assay (Millipore) was used in the cell invasion assay. In brief, we rehydrated each insert by adding serum-free medium, replacing it with serum-free suspension with equal amounts of cells in the upper chamber, and incubating the cells for 12 to 24 hours to allow the cells to migrate toward/invade the lower chamber containing 10% FBS. After removing the non-invading cells in the upper chamber, the cells invading through the inserts were stained with the supplied dye, dissolved in extraction buffer, and transferred to 96-well plates for colorimetric reading at 560 nm by using ELISA microplate reader (GloMax Discover, Promega) [42, 43].

Expression, small RNA interference plasmids, and transfection

Cysteines 87 and 88 of SULF1 (designated as SULF-1 delta CC) were mutated to alanines for blocking N-formylglycine modification of Cys87 of SULF-1 [44]. Transfected plasmids with wild type and mutant type SULF1 were cultured in BFTC909 cell lines for reexpression then analyzed using western blotting [44].

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS V.14.0 software (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA). The Chi-square test was performed to correlate SULF1 immunoexpression to various clinicopathological parameters. The end points analyzed were disease-specific survival (DSS) and metastasis-free survival (MeFS), as calculated from the starting date of curative operation to the date on which an event developed. Patients lost to follow-up were censored on the latest follow-up date. We plotted survival curves using the Kaplan-Meier method and the long-rank test to evaluate prognostic differences between groups. Parameters demonstrating less than 0.05 in the univariate analysis were subsequently enrolled in multivariate tests conducted using the Cox proportional hazards model. Student's t-test was used to analyze quantitative RT-PCR and functional assays for cell line samples. For all analyses, we used two-sided tests of significance with P < 0.05 considered significant.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS FIGURES AND TABLES

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

GRANT SUPPORT

This study was supported by Kaohsiung Medical University “Aim for the Top Universities” (KMU-TP105G00, KMU-TP105G01, KMU-TP105G02, KMU-TP105E26), Center for Infectious Disease and Cancer Research (KMUTP105), Kaohsiung Medical University Research Foundation (KMUOR105), NSYSU-KMU JOINT RESEARCH PROJECT (NSYSUKMU 106-P006). It is also supported by Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital (KMUH104-4R46, KMUH104-4R44, KMUH105-5R47), the Biobank at Chi Mei Medical Center, as well as the health and welfare surcharge on tobacco products, Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW106-TDU-B-212-144007) and Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST104-2314-B-037-050-MY3).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ploeg M, Aben KK, Kiemeney LA. The present and future burden of urinary bladder cancer in the world. World J Urol. 2009;27:289–293. doi: 10.1007/s00345-009-0383-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rouprêt M, Babjuk M, Compérat E, Zigeuner R, Sylvester R, Burger M, Cowan N, Böhle A, Van Rhijn BW, Kaasinen E, Palou J, Shariat SF, European Association of Urology European guidelines on upper tract urothelial carcinomas: 2013 update. Eur Urol. 2013;63:1059–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verhoest G, Shariat SF, Chromecki TF, Raman JD, Margulis V, Novara G, Seitz C, Remzi M, Rouprêt M, Scherr DS, Bensalah K. Predictive factors of recurrence and survival of upper tract urothelial carcinomas. World J Urol. 2011;29:495–501. doi: 10.1007/s00345-011-0710-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai MN, Wang SM, Chen PC, Chen YY, Wang JD. Population-based case-control study of Chinese herbal products containing aristolochic acid and urinary tract cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:179–186. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lughezzani G, Burger M, Margulis V, Matin SF, Novara G, Roupret M, Shariat SF, Wood CG, Zigeuner R. Prognostic factors in upper urinary tract urothelial carcinomas: a comprehensive review of the current literature. Eur Urol. 2012;62:100–14. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bishop JR, Schuksz M, Esko JD. Heparan sulphate proteoglycans fine-tune mammalian physiology. Nature. 2007;446:1030–1037. doi: 10.1038/nature05817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarrazin S, Lamanna WC, Esko JD. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011:3. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ori A, Wilkinson MC, Fernig DG. The heparanome and regulation of cell function: structures, functions and challenges. Front Biosci. 2008;13:4309–4338. doi: 10.2741/3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vivès RR, Seffouh A, Lortat-Jacob H. Post-Synthetic Regulation of HS Structure: The Yin and Yang of the Sulfs in Cancer. Front Oncol. 2014;3:331. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morimoto-Tomita M, Uchimura K, Werb Z, Hemmerich S, Rosen SD. Cloning and characterization of two extracellular heparin-degrading endosulfatases in mice and humans. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49175–49185. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205131200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Narita K, Staub J, Chien J, Meyer K, Bauer M, Friedl A, Ramakrishnan S, Shridhar V. HSulf-1 inhibits angiogenesis and tumorigenesis in vivo. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6025–6032. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bret C, Moreaux J, Schved JF, Hose D, Klein B. SULFs in human neoplasia: implication as progression and prognosis factors. J Transl Med. 2011(9):72. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hur K, Han TS, Jung EJ, Yu J, Lee HJ, Kim WH, Goel A, Yang HK. Up-regulated expression of sulfatases (SULF1 and SULF2) as prognostic and metastasis predictive markers in human gastric cancer. J Pathol. 2012;228:88–98. doi: 10.1002/path.4055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosen SD, Lemjabbar-Alaoui H. Lemjabbar-Alaoui. Sulf-2: an extracellular modulator of cell signaling and a cancer target candidate. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2010(14):935–949. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2010.504718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nawroth R, van Zante A, Cervantes S, McManus M, Hebrok M, Rosen SD. Extracellular sulfatases, elements of the Wnt signaling pathway, positively regulate growth and tumorigenicity of human pancreatic cancer cells. PLoS One. 2007(2):e392. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeldres C, Sun M, Isbarn H, Lughezzani G, Budäus L, Alasker A, Shariat SF, Lattouf JB, Widmer H, Pharand D, Arjane P, Graefen M, Montorsi F, et al. A population-based assessment of perioperative mortality after nephroureterectomy for upper-tract urothelial carcinoma. Urology. 2010(75):315–320. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yan D, Lin X. Shaping morphogen gradients by proteoglycans. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a002493. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a002493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin X. Functions of heparan sulfate proteoglycans in cell signaling during development. Development. 2004;131:6009–6021. doi: 10.1242/dev.01522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frese MA, Milz F, Dick M, Lamanna WC, Dierks T. Characterization of the human sulfatase Sulf1 and its high affinity heparin/heparan sulfate interaction domain. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:28033–28044. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.035808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang R, Rosen SD. Functional consequences of the subdomain organization of the sulfs. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:21505–21514. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.028472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dhoot GK, Gustafsson MK, Ai X, Sun W, Standiford DM, Emerson CP., Jr Regulation of Wnt signaling and embryo patterning by an extracellular sulfatase. Science. 2001;293:1663–1666. doi: 10.1126/science.293.5535.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seffouh A, Milz F, Przybylski C, Laguri C, Oosterhof A, Bourcier S, Sadir R, Dutkowski E, Daniel R, van Kuppevelt TH, Dierks T, Lortat-Jacob H, Vivès RR. HSulf sulfatases catalyze processive and oriented 6-O-desulfation of heparan sulfate that differentially regulates fibroblast growth factor activity. FASEB J. 2013;27:2431–9. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-226373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ai X, Do AT, Lozynska O, Kusche-Gullberg M, Lindahl U, Emerson CP., Jr QSulf1 remodels the 6-O sulfation states of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans to promote Wnt signaling. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:341–351. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ai X, Kitazawa T, Do AT, Kusche-Gullberg M, Labosky PA, Emerson CP., Jr SULF1 and SULF2 regulate heparan sulfate-mediated GDNF signaling for esophageal innervation. Development. 2007(134):3327–3338. doi: 10.1242/dev.007674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dani N, Nahm M, Lee S, Broadie K. A targeted glycan-related gene screen reveals heparan sulfate proteoglycan sulfation regulates WNT and BMP trans-synaptic signaling. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1003031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yue X, Li X, Nguyen HT, Chin DR, Sullivan DE, Lasky JA. Transforming growth factor-beta1 induces heparan sulfate 6-O-endosulfatase 1 expression in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20397–20407. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802850200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang JD, Sun Z, Hu C, Lai J, Dove R, Nakamura I, Lee JS, Thorgeirsson SS, Kang KJ, Chu IS, Roberts LR. Sulfatase 1 and sulfatase 2 in hepatocellular carcinoma: associated signaling pathways, tumor phenotypes, and survival. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2011;50:122–135. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai JP, Sandhu DS, Moser CD, Cazanave SC, Oseini AM, Shire AM, Shridhar V, Sanderson SO, Roberts LR. Additive effect of apicidin and doxorubicin in sulfatase 1 expressing hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro and in vivo. J Hepatol. 2009;50:1112–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu P, Gou M, Yi T, Qi X, Xie C, Zhou S, Deng H, Wei Y, Zhao X. The enhanced antitumor effects of biodegradable cationic heparin-polyethyleneimine nanogels delivering HSulf-1 gene combined with cisplatin on ovarian cancer. Int J Oncol. 2012;41:1504–1512. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Staub J, Chien J, Pan Y, Qian X, Narita K, Aletti G, Scheerer M, Roberts LR, Molina J, Shridhar V. Epigenetic silencing of HSulf-1 in ovarian cancer: implications in chemoresistance. Oncogene. 2007;26:4969–4978. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Ashfaq R, Maitra A, Adsay NV, Shen-Ong GL, Berg K, Hollingsworth MA, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, Kern SE, Goggins M, Hruban RH. Highly expressed genes in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas: a comprehensive characterization and comparison of the transcription profiles obtained from three major technologies. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8614–8622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li J, Kleeff J, Abiatari I, Kayed H, Giese NA, Felix K, Giese T, Büchler MW, Friess H. Enhanced levels of Hsulf-1 interfere with heparin-binding growth factor signaling in pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer. 2005;4:14. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-4-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osaki M, Oshimura M, Ito H. PI3K-Akt pathway: its functions and alterations in human cancer. Apoptosis. 2004;9:667–76. doi: 10.1023/B:APPT.0000045801.15585.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li CF, Wu WJ, Wu WR, Liao YJ, Chen LR, Huang CN, Li CC, Li WM, Huang HY, Chen YL, Liang SS, Chow NH, Shiue YL. The cAMP responsive element binding protein 1 transactivates epithelial membrane protein 2, a potential tumor suppressor in the urinary bladder urothelial carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6:9220–9239. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang YH, Wu WJ, Wang WJ, Huang HY, Li WM, Yeh BW, Wu TF, Shiue YL, Sheu JJ, Wang JM, Li CF. CEBPD amplification and overexpression in urothelial carcinoma: a driver of tumor metastasis indicating adverse prognosis. Oncotarget. 2015;6:31069–31084. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li CF, Chen LT, Lan J, Chou FF, Lin CY, Chen YY, Chen TJ, Li SH, Yu SC, Fang FM, Tai HC, Huang HY. AMACR amplification and overexpression in primary imatinib-naive gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a driver of cell proliferation indicating adverse prognosis. Oncotarget. 2014;5:11588–11603. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang SH, Li CF, Chu PY, Ko HH, Chen LT, Chen WW, Han CH, Lung JH, Shih NY. Overexpression of regulator of G protein signaling 11 promotes cell migration and associates with advanced stages and aggressiveness of lung adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:31122–31136. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li CF, Fang FM, Kung HJ, Chen LT, Wang JW, Tsai JW, Yu SC, Wang YH, Li SH, Huang HY. Downregulated MTAP expression in myxofibrosarcoma: A characterization of inactivating mechanisms, tumor suppressive function, and therapeutic relevance. Oncotarget. 2014;5:11428–11441. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chiang LC, Chiang W, Chang LL, Wu WJ, Huang CH. Characterization of a new human transitional cell carcinoma cell line from the renal pelvis, RTCC-1/KMC. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 1996;12:448–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chi JY, Hsiao YW, Li CF, Lo YC, Lin ZY, Hong JY, Liu YM, Han X, Wang SM, Chen BK, Tsai KK, Wang JM. Targeting chemotherapy-induced PTX3 in tumor stroma to prevent the progression of drug-resistant cancers. Oncotarget. 2015;6:23987–24001. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Benedetti E, Antonosante A, d’Angelo M, Cristiano L, Galzio R, Destouches D, Florio TM, Dhez AC, Astarita C, Cinque B, Fidoamore A, Rosati F, Cifone MG, et al. Nucleolin antagonist triggers autophagic cell death in human glioblastoma primarycells and decreased in vivo tumor growth inorthotopic brain tumor model. Oncotarget. 2015;6:42091–42104. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ching RH, Lau EY, Ling PM, Lee JM, Ma MK, Cheng BY, Lo RC, Ng IO, Lee TK. Phosphorylation of nucleophosmin at threonine 234/237 is associated with HCCmetastasis. Oncotarget. 2015;6:43483–43495. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morimoto-Tomita M, Uchimura K, Werb Z, Hemmerich S, Rosen SD. Cloning and characterization of two extracellular heparin-degrading endosulfatases in mice and humans. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49175–49185. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205131200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.