Abstract

This article argues that technological innovation is transforming the flow of information, the fluidity of social action, and is giving birth to new forms of bottom up innovation that are capable of expanding and exploding old theories of reproduction and resistance because ‘smart mobs’, ‘street knowledge’, and ‘social movements’ cannot be neutralized by powerful structural forces in the same old ways. The purpose of this article is to develop the concept of YPAR 2.0 in which new technologies enable young people to visualize, validate, and transform social inequalities by using local knowledge in innovative ways that deepen civic engagement, democratize data, expand educational opportunity, inform policy, and mobilize community assets. Specifically this article documents how digital technology (including a mobile, mapping and SMS platform called Streetwyze and paper-mapping tool Local Ground) – coupled with ‘ground-truthing’ – an approach in which community members work with researchers to collect and verify ‘public’ data – sparked a food revolution in East Oakland that led to an increase in young people’s self-esteem, environmental stewardship, academic engagement, and positioned urban youth to become community leaders and community builders who are connected and committed to health and well-being of their neighborhoods. This article provides an overview of how the YPAR 2.0 Model was developed along with recommendations and implications for future research and collaborations between youth, teachers, neighborhood leaders, and youth serving organizations.

Keywords: People sensors, location-based services, citizen science, digital organizing, Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR), CPBR, environmental justice

Introduction

The evolution of smart phones, wearables, micro-chips, GPS, GIS, and information communication technology (ICT) is transforming the field of Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR). Over the past several decades the increasing miniaturization and subsequent proliferation of people-sensing platforms and wireless networks is helping to drive this trend by creating new ways to share and visualize information about ourselves, friends, communities, and the ways in which we live, learn, work, and play. People-sensing platforms expand the traditional notion of YPAR in which young people identify a local issue, develop a research agenda, and plan an appropriate intervention – by adding wireless sensor networks, location-based devices, digital organizing, participatory technology, data visualization and community asset mapping to the research process enabling a host of new ways to democratize data and decision-making in real time and engage in health promotion. The emergence of new technologies has many potential benefits for young people. All one has to do is to observe the prolific use of cell phones and social networking platforms like Facebook Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, and ‘the next big thing,’ to see that today’s youth are born digital – seamlessly integrating technology into their everyday lives (Lenhart, Purcell, Smith, & Zickuhr 2010; Nielsen, 2014). At the same time, technological advances in mobile, mapping, SMS, and location-based services are shrinking the digital divide and turning the rapidly expanding mobile marketplace into a global sensor network. This article describes a model (YPAR 2.0) for using location-based technology, new media, and digital organizing to engage youth in ‘people powered place-making’ and urban health promotion.

The YPAR 2.0 Model was developed iteratively by the author, staff, and young people at the Institute for Sustainable Economic Educational and Environmental Design (ISEEED) located in Oakland, CA. Oakland shares many of the same problems as other communities suffering from de-industrialization, displacement, and massive gentrification (Self, 2005). Just like 26.5 million other Americans, East Oakland and West Oakland are located in food deserts and surrounded by liquor stores, fast food, brown fields, abandoned buildings, vacant lots, and poor air quality. People are dying from curable diseases in our communities. For instance, the obesity rate in West Oakland – which is at the edge of where ISEEED is located – is five times higher than, say, Piedmont, which is 2 miles away.

Founded in 2012 by the author, Dr. Allyson Tintiangco-Cubales, and Dr. Jeff Duncan-Andrade and with support from Pedro Noguera, Sanjeev Khagram, Patrick Camangian, Aekta Shah, Aaron Nakai, Bouapha Toommaly, Ana Cervantes, Sabaa Shoraka, Tessa Cruz and others – ISEEED is at the forefront of building culturally and community responsive technology tools that increase civic engagement and create positive community development models which integrate technology and participatory action research into health promotion, education, and urban planning. Part design lab, part community capacity builder, part accelerator of neighborhood innovation, ISEEED is internationally recognized for addressing the role that technology can play in putting the power back in the hands of everyday people by identifying community assets, providing real-time feedback loops, crowd-sourcing data, elevating place-based stories & counter-narratives, and transforming schools & communities through ongoing youth and community-driven metrics, monitoring, and evaluation (Tintiangco-Cubales et al., 2014).

A fundamental pillar of ISEEED’s community engagement strategy centers on researching, developing, and deploying technology platforms that communities need to make decisions and take action. Communities are limitless repositories of local knowledge and often develop their own innovative tools and placed-based practices for information sharing (Patel, Sotsky, Gourley, & Houghton, 2013). ISEEED’s work seeks to understand these invisible ecosystems and to build tools and systems that help communities collect and share information and connect that information to collaborative design principles and action that improves the built environment and enhances educational outcomes. In particular we focus on tools that can help amplify the voices of communities often excluded from the digital and physical public spheres and connect them with resources that help transform ecosystems, augment civic participation, increase knowledge mobilization, and foster digital inclusion. This article describes the ways in which the author and ISEEED staff translated a research project on food access, food security, and civic technologies in East Oakland into action by describing YPAR 2.0 as a new model for integrating location-based technology, participatory media, and digital organizing to engage urban youth in social justice and health promotion.

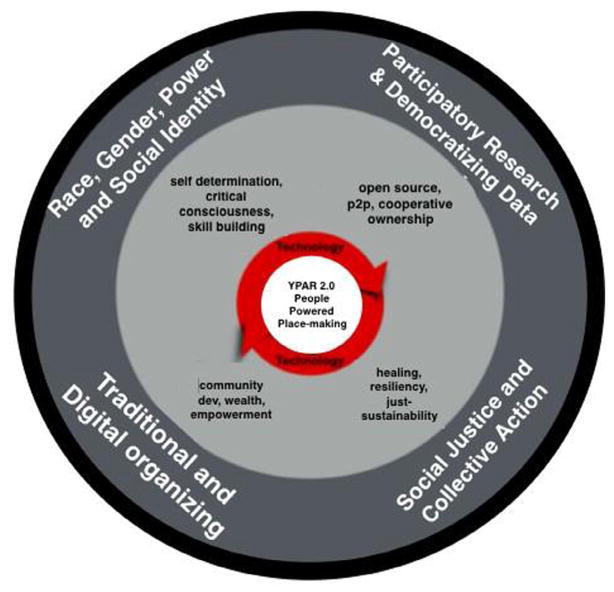

The YPAR 2.0 Model is designed to be used with youth facilitators, teachers, or adult facilitators working with youth serving organizations (YSOs) or directly with schools. A visual representation of the YPAR Model is provided in Figure 1. In contrast to neo-liberal educational interventions, which often narrow what constitutes ‘expert’ knowledge, YPAR 2.0 emphasizes local knowledge and collaborative problem solving and allows for deeper and multi-directional analysis of the power dynamics between race, space, place, and waste. Additionally, by utilizing ‘ground-truthing’ YPAR 2.0 can in many instances improve the accuracy of secondary and quantitative public data sets.

Figure 1.

YPAR 2.0 visual. Source: Adapted from Flicker et al. (2008).

A critical driver towards YPAR 2.0 is the diminishing digital divide on a national and international scale (Resch, 2013; Ridgley, Maley, & Skinner, 2004). The digital divide is composed of at least two key components: (1) that access to the Internet of Things (IOT) and ICT is ‘unevenly distributed around the world and within countries’ (Resch, 2013, p. 392); and (2) the disproportionate access to ICT and IOT have far reaching societal impacts because people with access to these institutional resources and privileges have increased chances for educational and economic development (Nielsen, 2014; Resch, 2013, p. 392). The growth of ‘mobile technology in China, India, East Asia, Africa, and South America both within countries and between countries is strongly shaping access to information’ (Resch, 2013, p. 392). Mobile penetration was at 76.2% of the world’s population in 2010, 94.1% in the Americas and grew 131.5% in the Commonwealth of Independent States over the past year (ICT Data & Statistics Division, 2015). Additionally, the concept of YPAR 2.0 is strongly supported by the exponential growth in use of the Internet. Predictive analytics suggest that the number of users will grow from 2 billion internet-users in 2010 to 50 billion connected devices in 2020 (Resch, 2013). This rapid growth is a clear indication that YPAR 2.0 has arrived and is here to stay.

This article begins with an overview of the realities that young people who live in neighborhoods like East Oakland must navigate on a daily basis, and the ways in which these students are often mis-categorized and mis-represented by resistance theorists and oppositional culturalists. We then outline the theoretical basis of the YPAR 2.0 Model and the ways in which technology is enabling youth to be more active agents in the research process, while also making democracy more transparent, efficient, and inclusive of community input. In the third section we provide a description of the Mapping 2 Mobilize collaborative (M2M) in East Oakland including its use of the Local Ground mapping platform and Streetwyze community engagement platform (originally called B-TEC), and how this lead to ground-truthing. We close by summarizing findings and discussing implications for research and practice.

YPAR 2.0 Model in theory

Living in areas of punishing poverty and toxic waste, burdened by the legacy of slavery, servitude, and second-class citizenship, too many Black and Brown youth are dying of unnatural causes. They are vanishing or in the classic metaphor of Ralph Ellison they are being rendered invisible to such an extent that dysfunctional schools, dilapidated housing, food deserts, brown fields, unemployment, prison, pollution, diabetes, detention, and early death – have now become part of the expected social trajectory for many of youth of color from low-income communities (Akom, Scott, & Shah, 2013; Akom, Shah, & Nakai, 2014). When youth of color resist, when they speak out and make their insightful institutional and social critiques known, when they talk about what’s right in their communities instead of what’s wrong – they are often referred to as engaging in ‘oppositional culture’ (Akom et al., 2013, 2014; MacLeod, 1987/1995). Strongly identified with disruptive behavior, adopting a non-conformist style of dress, talking back, devaluing educational achievement – Black and Brown youth are too often rejected and labeled as social problems by the police, schools, employers and employment agencies (Dance, 2002; MacLeod, 1987/1995).

This article analyzes these young peoples’ struggles and resistance by theorizing working class students’ oppositional behavior in the context of using technological innovation and participatory action research to transform social and material conditions and engage in people powered place- making. Early resistance theorists faced two major challenges that have not been adequately addressed by YPAR or resistance literature. One, they failed to understand the centrality of structural racism in the life and every day experiences of working class youth. Willis (1975) and other resistance and reproduction researchers are barely audible when it comes to race – particularly the structural dimensions of race (Akom, 2009a, 2009b; Akom, 2011a; Akom, Cammarota, & Ginwright, 2008; Bonilla-Silva, 2001; Cammarota & Fine, 2010; Omi & Winant, 2004, 2014; Powell, 2007, 2008; Winant & Omi, 1986).

Yet, structural racialization, particularly cumulative causation or what Akom refers to as Eco-Apartheid (2011a) not only figures prominently in the collective identities of working class youth of color, but substantially shapes the entire opportunity structure in terms of access to institutional resources and privileges (Hacker, 1992; Williams & Collins, 2001). The second flaw in early resistance literature is that theorists examined working class students’ oppositional behavior during a time when manufacturing jobs were readily available for white males only. In other words, they argued that oppositional behavior constituted a rejection of middle class culture motivated by an implicit understanding of the myth of meritocracy that was racist, gendered, patriarchal, and homophobic (Nolan, 2011).

This article presents a new and expanded theory of youth resistance called YPAR 2.0. It challenges readers to go beyond traditional dichotomies of reproduction or resistance. Instead, YPAR 2.0 presents an analysis of youth resistance that includes womanist and feminist critiques between oppressed/oppressor and highlights the ways in which intersecting systems of power and privilege operate in low income communities and communities of color (Hooks, 2000; Tsuruta, 2012). As a result of this more nuanced approach, embedded within the YPAR 2.0 Model are forms of structural transformation and individual agency that complicate, expand, and potentially implode, current conceptualizations of youth resistance theory and participatory action research.

This article builds on the works of several scholars on race, space, and community mapping, including Powell (2007, 2008), Al-Kodmany (2000), Flicker et al. (2008), Corburn (2002, 2005), Bonam, Eberhardt, Markus, and Ross (2010), Noguera (2003), Tuck and Yang (2013), Ginwright (2010), Parikh et al. (2006), Van Wart and Parikh (2013), Kelley (1996), Agyeman (2003), Solorzano and Bernal (2001), Duncan-Andrade and Morrell (2008), Sadd et al. (2013), Bullard (1990), Bullard, Johnson, and Torres (2004), Bell and Lee (2011); Darden (1986), Pulido (2000), and Tintiangco-Cubales et al. (2014). In particular, we build from and expand these theories while also engaging questions that were previously un-addressed or under-addressed. We argue that youth resistance theory needs to be ‘Revolutionized’ in the sense that many early and contemporary researchers have focused on the self-defeating resistance of working-class students without acknowledging and studying other forms of resistance that could lead to structural and individual transformation.

As powerful as Willis (1975) landmark study of social identities and social justice in education has been for critical theorists of education, the key question and seminal process to be studied from my point of view isn’t how working class kids get working class jobs – or self-defeating resistance. Rather, a more contemporary and transformative question is: How do working class kids get world-class careers, while maintaining their racial/ethnic and social identities, healing from physical and emotional trauma (Ginwright, 2010), exercising self-efficacy and self-determination, and remaining connected to their community cultural wealth (Yosso, 2005). A YPAR 2.0 Model of community engagement begins to address these questions and helps us move from solely focusing on ‘raising young peoples’ consciousness (which is often a stated goal of PAR/YPAR projects) to simultaneously focusing on transforming social and material conditions and affecting real world change.

Historical overview: the birth of PAR & YPAR 2.0

The term participatory research (PR) was born in Tanzania in the early 1970s with revolutionary roots that trace back to emancipatory social movements of resistance, agency, and political contestation (Park, Brydon-Miller, Hall, & Jackson, 1993). The central methodology to promote community empowerment comes from Brazilian educator Freire (2000), who advocates a liberatory education based on dialogue, mutual respect, and belief that people can listen to their own experiences, discuss common interconnections and create actions to change their lives and the health and well-being of their communities (Khanlou & Peter, 2005; Wallerstein & Auerbach, 2004; Wallerstein & Duran, 2006; Minkler, 2005; González et al., 2007). Energized by the political urgency of the times, Freire, Fals-Borda, and other scholars from developing countries created an alternative method of inquiry as a direct counter to the ways in which knowledge about people of color was being ‘collected, classified, and characterized by the West, and at times, mis-represented by those who have been colonized by the West’ (Khanlou & Peter, 2005; Smith, 1999, p. 3). In his seminal article on PR, Hall (1981) identified its central goals and key characteristics. The goal of PR is community transformation and its target of focus is ‘exploited or oppressed groups; immigrants, labor, indigenous peoples, women’ (Hall, 1981, p. 7).

In the years that followed, feminist, womanists, and critical race theorists added further conceptual depth and richness to the participatory action research approach (Akom, 2009a, 2009b; Collins, 2003). Feminist researchers raised critical questions about traditional PAR approaches purporting to be gender neutral and questioned PAR’s commitment to gender equality (Gatenby & Humphries, 2000). Black Feminist scholars shifted the PAR paradigm by introducing an interlocking system of race, class, sexual orientation, and gender oppression into PR methods (Collins, 1991, 2003). And Africana Womanists stated in no uncertain terms the importance of race for Black women as an important prerequisite for dealing with issues of gender (Hudson-Weems, 1994; Tsuruta, 2012).

This method of social inquiry was termed by Freire (2000) as ‘pedagogy of the oppressed’ – a social praxis, or process, wherein communities learn to perceive social, political, and economic contradictions, and to take action against the oppressive elements society. At the core of Freire’s work was the desire to understand the ways in which adults ‘read’ the world’s existing political and economic stratifications. However, even though Freire’s pedagogical techniques revolutionized adult education and literacy programs worldwide, absent from Freire’s analysis was an explicit commitment to understanding how young people ‘read’ existing racial, gendered, and socio-economic stratifications.

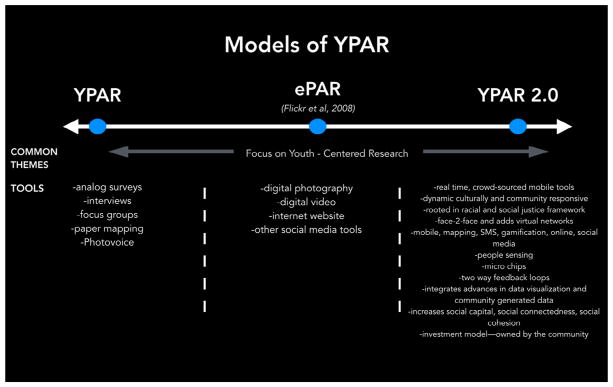

Drawing from critical, feminist, and post-structuralist theorists e-PAR (electronic participatory action research) emerged at the dawn of the twenty-first century for the purpose of liberatory activism and social change, and began to expand the mechanisms and processes for which subordinate groups claim autonomy and independence over their own lives. What is unique about ePAR is its commitment to using technology, social media, and communication tools as strategies to engage youth in health promotion, community development, civic engagement, and social activism (Flicker et al., 2008). At the core of the ePAR Model is the belief that youth have the capacity to make transformative change in themselves and in their communities, and that encouraging youth to become critical thinkers by using youth-centered media methodologies that support critical scientific inquiry leads to transformative social change (Flicker et al., 2008). See Figure 2 for continuum depicting different models of YPAR.

Figure 2.

Models of YPAR continuum.

YPAR 2.0 draws from the rich tradition of PR, ePAR, popular education, and other PAR methodologies and is premised on the notion that technology advances in sensing, communication, computation, visualization, and storage, are enabling young people to see, hear, share, sense, learn, and validate information about themselves, friends, families, and communities in ways previously unimaginable.

YPAR 2.0 follows and extends traditional forms of PAR with one in which young people carrying or working with ICT, mobile devices, social media, micro-technology advances, and/or other digital organizing platforms in order to challenge ‘expert knowledge’ with real time ‘local knowledge’. This local knowledge can be crowd-sourced and as a result create new forms of bottom up validity, reliability, and innovation that can be analyzed through a rigorous systematic process (Cammarota & Fine, 2010; Corburn, 2002, 2005).

By embracing a people power place-making approach whereby youth and the technologies they are using are the key architectural components in facilitating two-way feedback loops that have the power to transform oppressive social and material conditions, YPAR 2.0 offers subordinate groups new ways to share their own stories and highlight the good stuff happening in the communities where they live, learn, work, play, and pray.

YPAR 2.0 Model in practice

In the twenty-first century powerful special interest groups continue to hi-jack our democracy and one of the ways to reclaim the democratic ethos are new forms of technological innovation and creative place-making that strengthen informal and formal social networks, build power and self-determination, and improve social capital. YPAR 2.0 also reveals new ways of knowing, experiencing, seeing, hearing, sharing, and communicating for youth to define their own reality which has far greater implications because it begins to transform social relations of domination and resistance, subjectivity and objectivity, official knowledge and local knowledge, researched and researcher.

In a YPAR 2.0 Model, youth, working with adults (or sometimes not) (Camino, 2005), become the focal point of people power place-making, and the visualization of the data they collect is for themselves, their friends, the community, and/or, if they choose, they may partner with university researchers, scientists, or engineers. Additionally, young people’s ability to carry sensing devices enables coverage of public spaces that would otherwise be difficult to reach (e.g. the fastest growing cities in the world are informal settlements, ghettos, slums, favelas and cities, schools, and municipalities have very little data on what’s happening inside of these communities. YPAR 2.0 allows us to see, feel, hear, and experience what’s happening beneath the regulatory radar from the perspective of those who are most marginalized. Even basic data like dirt roads and roads without names can be visualized and ground-truthed with YPAR 2.0). YPAR 2.0 also allows individuals to act as ‘information catalysts’ by using local knowledge in innovative ways that deepen civic engagement, democratize data, expand educational opportunity, inform policy, mobilize community assets, and generate shared wealth.

Because YPAR 2.0 utilizes theories of empowerment education, problem-posing education, and popular education, its implementation with youth in educational and community settings expands the goals of positive youth development to include personal and community transformation (Freire, 2000; Ginwright, Noguera, & Cammarota, 2006). By providing participants with opportunities for meaningful engagement in problem identification, analysis, participatory planning, civic engagement, and youth-led evaluation, YPAR teaches young people to ‘read the world’ and develop skills, which can contribute to a sense of mastery, power and control over their environment.

As introduced above, the YPAR 2.0 Model is designed to be used with a youth facilitator, teachers, or adult facilitators working with YSOs or directly with schools and is premised on the notion that youth are active agents in their own transformation. The Model is most effective when youth are initially grounded in the local history of race, class, gender, sexual orientation, disability and other systems of interlocking oppression (Akom, 2009a, 2009b, 2011a, 2011b; Duncan-Andrade & Morrell, 2008; Morrell, 2008; Nasir, Rosebery, Warren, & Lee, 2006). Second, it is important to focus on young people’s emerging ‘assets,’ ‘agency,’ and ‘aspirations’. In this regard, YPAR 2.0 should be nested in an asset-based and collective impact framework that organizes young people around common agendas, shared progress measures, mutually reinforcing activities, and a culture of collaboration. Third, young people should be given the freedom to innovate by using new and culturally and community responsive ‘youth-friendly’ participatory technologies (Ridgley et al., 2004; Strack, Magill, & McDonagh, 2004). Meeting places that are always safe and supportive (Lax & Galvin, 2002). ‘They are given an appropriate amount of responsibility and control … are supported through a trained and trusted facilitator … and an agreed upon governance structure’ (Flicker et al., 2008, p. 289). As such the Model is about introducing a more expansive notion of youth cultural production, one that posits young people, and the technology that they use, as central subjects to knowledge production and underscores their ability to actualize their agency for personal, social, and community transformation and the building of formal and informal forms of social capital and community cultural wealth (Akom, 2008; Yosso, 2005).

YPAR 2.0 key stakeholders

YPAR 2.0 while grounded in theory was cultivated in practice. Between 2011 and 2013, the Model was implemented to study and address community-defined environmental justice issues in East Oakland and beyond. Initially anchored by Youth Uprising, a YSO with strong roots in East Oakland, I-SEEED, a community-based organization with expertise in YPAR, Community based participatory research, participatory technology, education and environmental justice, and Oakland Unified School Districts Research-Assessment-Data dept, the collaborative grew in size and scope to San Francisco State University and UC Berkeley, Castlemont High School, and additional community-based partners.

The initial vision was to help move OUSD from thinking about putting health centers in schools towards a new model of educational transformation where schools could be seen as centers of health and well-being for the entire community – i.e., full service community schools (Duncan-Andrade, 2011). According to OUSD officials one of the catalysts for this shift in philosophy was the movie Unnatural Causes (2007) which was grounded in a social determinants of health model which argues that a persons life chances, command over resources, health and well-being is directly linked to their access to opportunity and the neighborhood conditions in which they grow up and live (Morello-Frosch, Pastor, & Sadd, 2002; Pastor, 2000; Pastor, Sadd, & Morello-Frosch, 2002; Reece, Norris, Olinger, Holley, & Martin, 2013). More specifically, the summer mapping work was an important piece of a larger OUSD effort around opportunity mapping which built off of and expanded john powell’s work at the Kirwan Institute and was led by then Oakland Superintendent Tony Smith.

In order to ‘ground-truth’ students’ daily access to opportunity our team set out to examine student, family, community health and well-being, and connect these variables to children’s ability to thrive and learn in school (Morello-Frosh et al., 2011; Sharkey & Horel, 2008). The unique approach that we collectively developed we came to internally call ‘Streetwyze’: which at the time meant a 360° view of educational space ranging from effective teaching, to physical, behavioral, emotional well-being data, as well as place-based indicators of healthy neighborhoods and access to opportunity where children live, learn, work, play, and go to school.

Project design

To begin to better understand the ways in which out of school neighborhood conditions can impact how young people learn and thrive, during the summer of 2011 we initially used a platform called Local Ground. Local Ground is a paper-mapping tool that captured qualitative data, created digital annotations, and then imported the annotations on to a digital map. However even though Local Ground is a brilliant paper mapping technology, we found it insufficient as a standalone mechanism to measure neighborhood indicators around young people’s access to opportunity without first being rooted in a racial and social justice pedagogical framework that helped the young people ‘read the world’.

As a result, we incorporated ISEEED’s YPAR 2.0 methodology and expertise with culturally and community responsive technology, as well as OUSD’s Opportunity Mapping project as the most comprehensive way to measure the accessibility to health and educational related resources, embed young people in STEM opportunity mapping, 360 feedback loops, and sustainable urban design.

During phase II of our project, which spanned Sept 2011–2013, the young people we were working with continued to demand a mobile digital platform that could produce real time data, rankings/ratings, and integrate social media elements. To meet this demand we first approached UC Berkeley’s School of Information about partnering with ISEEED to build a separate and distinct platform from Local Ground’s paper maps. However, they respectfully declined to pursue a different research agenda. As a result, ISEEED began building and incubating what would become the Streetwyze platform – a mobile, mapping, and SMS tool that collects real time information about how people are experiencing cities and services and turns them into actionable analytics.

Over the course of 3 years we worked with 90 youth. The youth met 4 weeks during the summer as well as 9 months throughout the school year at Castlemont High School. In terms of recruitment, ISEEED staff approached Youth Uprising, Castlemont High School, and University partners to ask if they would be interested in collaborating to test our Model. In some instances, ISEEED staff (including youth interns) facilitated the process, in others a co-facilitation approach with Castlemont teachers was employed. During the summer, participating youth were paid an honorarium for project participation and were asked to commit to summer work. During the academic year, students (who were juniors and seniors) received college credit for the course through the Step-to-College program at San Francisco State University, which awards college level credit for High School juniors and seniors and is an important model of youth development and college and career pathway building in low-income communities. Over the course of 3 years, we trained three cohorts of 30 students each and conducted extensive interviews with 30 youth. The table below summarizes the grade, race, and gender of the students interviewed (all names are pseudonyms to protect the identity of the youth) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Summary of interview data of 30 youth participants over 3 years.

Mapping the neighborhood

Youth Uprising (adults and youth) were influential in helping to develop the initial focus on food access and food insecurity. An important focus of Youth Uprising is to educate youth and communities about the impact of food insecurity on people and communities locally. We defined food insecurity as: the structural, political, and experiential limits on the availability of nutritious, healthy, affordable, and culturally appropriate foods, and/or limited or uncertain access to food (Alter & Eny, 2005; Alkon & Norgaard, 2009; Basch, 2011; Belot & James, 2011; Block, Scribner, & DeSalvo, 2004; Brownell & Horgen, 2004). Measured at the community level, food security investigates the underlying racial, social, economic, and institutional factors within a community that affect the quantity and quality of available food and its affordability relative to the financial resources available to acquire it (Cohen, 2002). In order to investigate food insecurity in East Oakland, the collaborative decided to ‘ground-truth’ the Alameda Country Public Health Department’s ‘food outlet’ database which identifies East Oakland as a food oasis when the young living there are aware that it is a food desert. The ground-truthing process began with workshops during which youth were trained on theories of structural racialization, youth empower-ment, resistance, problem-posing education, the science of environmental health, cumulative impacts, social vulnerability, as well as state and federal databases that keep locational and other records of the number of grocery stores and corner stores in the neighborhood. The YPAR 2.0 workshops also trained young people on the use of diverse methodologies to solve the food apartheid problem including: resident interviews, store-owner interviews, a community health survey, location based participatory technology, digital media, and GIS mapping.

These early place-making workshops led the youth to gain a deeper understanding of the complex intersection of race, space, place, and waste in general, and in particular, food access issues in East Oakland. Through analog and digital community mapping activities and the development of a youth driven community health survey, it became clear that the origins of food apartheid and associated negative health outcomes arose from a multitude of sources – including structural racism, transportation gaps, grocery store gaps, poor lunch quality, congested schools, dilapidated housing – and that higher incidents of diabetes and childhood obesity were directly related to inadequate access to fresh, healthy, and culturally appropriate food. Problem posing though community mapping helped make visible complex structural issues about the intersection of race, space, place, and waste and motivated the youth to take a closer look at the gap between ‘official’ knowledge and local knowledge in relation to food access.

To ground-truth what regulatory databases (such as the Alameda County Public Health Department) were recognizing as a food oases – however youth were experiencing as food deserts – youth conducted mapping research, visiting 30 retail-food outlets in East Oakland to determine how many were in fact grocery stores, vs. liquor stores or corner stores. More specifically, to ground-truth food retail outlets in East Oakland, youth were equipped with clipboards, Local Ground paper maps embedded with digital QR codes, handheld digital devices (iPhones, Smartphones, tables, Flip Cameras, and later we prototyped the Streetwyze mobile, mapping, and SMS platform), and step-by-step instructions on data collection. Group leaders organized participants into teams of three – with each team trained and responsible for conducting street-by-street assessments of their portion of the study area, identifying, and locating grocery stores, liquor stores and/or any other type of food/retail outlets.

Teams were tasked the following (Sadd et al., 2013):

Verify the location and correct information of all food retail outlets/’grocery stores’ documented in regulatory agency (Alameda County Public Health Department) databases – Collecting written data on paper maps as well as pictures and audio-field notes of observations.

Verify the type of retail outlet as defined by the local community (liquor store, corner store, grocery store, ethnic food store, smoke shop, gas station, etc.) – Collecting written data on paper maps, written field notes, as well as pictures, and audio field-notes.

Locate and map any additional food retail outlets and healthy food locations not included in the regulatory agency databases – Collecting written data on paper maps, written field notes, as well as pictures, and audio field-notes.

Five communities in East Oakland were mapped to test the YPAR 2.0 Model: MacArthur Blvd, International Blvd, Eastmont District, High Street, and Fruitvale District (Oakland Uptown, Oakland Chinatown and Piedmont were also mapped as comparative communities, but used a different protocol and thus these data are not reported here). To characterize variations in categorization of retail outlet, youth developed a plan to visit these sites in groups of at least two (to internally check for variation in outlet categorization during the summer), between 10 am and 8 pm, including both low and high ‘rush hour’ traffic periods (Sadd et al., 2013).

Results and analysis

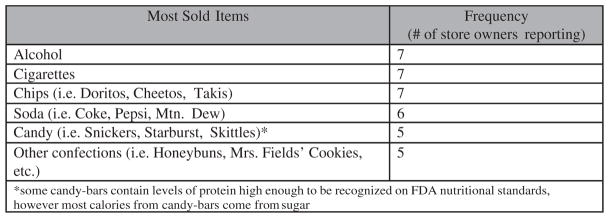

Ground-truthing revealed that retail food outlet locations were majority liquor stores and corner stores, rather then grocery stores. Youth researchers further found that the top three non-tobacco or alcohol-related products available at these stores were chips, soda, candy/confection-items (i.e. Snickers, Skittles, Honeybuns), many of which had high sugar, fat, and salt content. Figure 4 shows an itemized list of most sold items (as reported by store owners) at seven retail outlets on MacArthur Boulevard. Asterisked items depict items containing some nutritional value as identified by the US FDA’s nutritional guide. Sales tended to peak between 12 and 8 pm, according to store owners, corresponding with school lunch-time, after-school and dinner period during which most youth consume the majority of their daily calories. This is not atypical to MacArthur community: each of the five communities mapped had a similar distribution of types of food/beverage items sold as well as peak hours of consumption.

Figure 4.

Itemized list of most sold items at seven food retail outlets on MacArthur Boulevard.

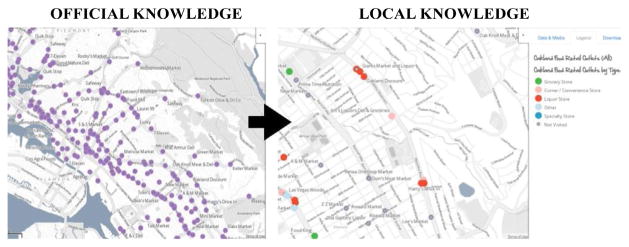

Youth-generated data on locations and types of grocery stores vs. liquor stores and corner stores was also produced. Figure 5 shows the official public database of how many grocery stores were in East Oakland vs. local knowledge. It should come as no surprise that once the data was ground-truthed, validated, and verified, that instead of there being 50 grocery stores and E. Oakland appearing to be a food oasis, ground-truthed data showed there were only three grocery stores and the rest were liquor stores (within the bounded area between 35th and 90th between International Boulevard and MacArthur Avenue). As a result of engaging in a YPAR 2.0 research process youth were empowered and gained confidence not only in the authenticity of their findings, but also as ‘people powered place-makers’ with the ability to link knowledge to action.

Figure 5.

Official public database vs. ‘Ground-truthed’ Database. Source: Images from Local Ground.

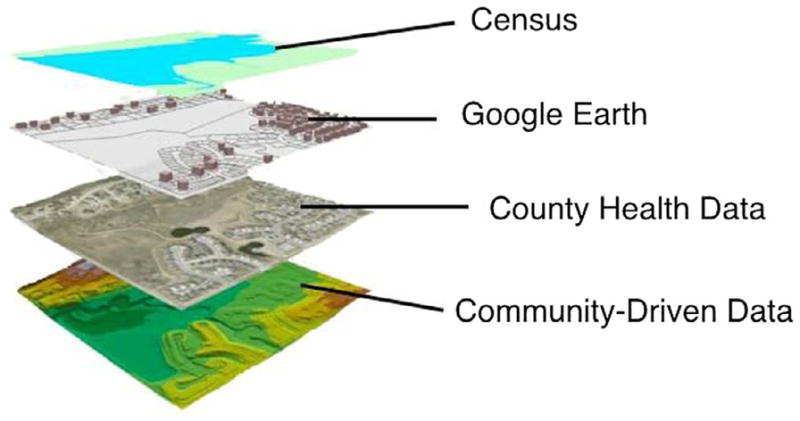

This is exactly why YPAR 2.0 is an important model of research in low-income communities and communities of color. What the YPAR 2.0 Model demonstrates is that merely having multiple sets of data points and information is insufficient. Without systematic ways of integrating ‘Big data’ with community-generated data, data can be confusing or appear as a disorganized array of random facts (González et al., 2007). The real challenge of the twenty-first century data revolution is then how do you intergrate official data with local knowledge in ways that make data more valid, reliable, authentic, and meaningful from the perspective of everyday people. In order to address this question we used Local Ground (and later Streetwyze community mapping platforms) as data engines that not only triangulated, but also integrated ‘big secondary data’ with smaller community-generated data in order to provided a ‘thick description’ of the relationship between race, space, place and waste. By using tools like Local Ground and Streetwyze, we were able to map and data-visualize and corroborate results with digital media, place-based storytelling and counter narratives, youth interviews, and secondary data that identified the hot spots and cool spots of food security in East Oakland (Van Wart, Tsai, & Parikh, 2010). In Figure 6 we show how the Local Ground and Streetwyze platform are able to display multiple data layers.

Figure 6.

Data layers.

Replacing symbols of decline with symbols of improvement

There is a great deal of research on community development that describes neighborhood decline, however much less that describes urban renewal from the prospective of the people who actual live there (Anderson, 1990). Any significant amount of time spent talking with everyday people will generally yield an understanding that there are specific places in urban neighborhoods that symbolize decline. This could be a particular building, an abandoned lot, or a corner store that has seen sunnier days. YPAR 2.0 helped the young people identify areas of decline and turn them into areas of renewal.

For example, integration of different data layers helped the young people achieve policy outcomes at the local, municipal, and state levels. The types of health-promoting changes recommended by youth researchers to help transform the food environment and help spark a food revolution in liquor/corner stores were:

Stock more of fresh produce (encouraging organic and locally grown);

Stock more healthy staple foods (e.g. whole wheat bread or skim milk);

Stock healthy products at more affordable prices through participation in food stamp, WIC and other related programs;

Adhere to environmental standards and codes that address loitering, cleanliness, and safety;

Limit tobacco and alcohol advertising, promotion, and sales;

To further mitigate food insecurity conditions in East Oakland, youth researchers recommended:

Locate farmers’ markets in central youth-serving locations throughout East Oakland – such as at school-sites or at organizations like Youth Uprising (Note: this recommendation was implemented with a farmers’ market at Castlemont High School launched during the 2011–2012 school year).

Examine alternate uses for empty lots (prevalent throughout) East Oakland – recommendations included: Pop-up farmers’ market sites, urban farm sites, or future grocery-store locations.

Corner store and other health-promoting recommendations were disseminated through a presentation that the YPAR 2.0 collaboration helped develop under the direction of lead organization ISEEED.

The pilot store-mapping project was seen as a local success with broad interest in replication and expansion. Community and school-based partners shared that the combination of research and media both raised awareness of the issues and influenced decision-makers to address food apartheid in preliminary ways. Additionally, in Fall 2011, Castlemont High School launched a weekly farmers-market – featuring produce grown on the school’s student-run urban farm. And in 2012 Oakland Unified School District announced a central Food Commissary in West Oakland (a community that experiences food apartheid conditions in similar ways to East Oakland) featuring a forty-four thousand (44,000) square foot specialized kitchen space, four-thousand (4000) square foot healthy food education center, and a 4-acre urban farm accessible to OUSD students.

Youth perspective

The project also illustrates how principles and methods of YPAR 2.0 can be adapted for use with youth in an underserved community to increase feelings of empowerment, facilitate the development of critical thinking skills, and promote social justice through social action. As stated by various interventionists and researchers (Catalano, Haggerty, Oesterle, Fleming, & Hawkins, 2004), YPAR 2.0 can lead to the fostering and building of competence (skills and resources for developing healthy options, developmentally appropriate skill- building activities), confidence (opportunities for making decisions, positive self-identity), connection (primary or secondary support, bonding with others, relationships with caring adults and peers), character (a sense of responsibility for self and for others), caring (a sense of belonging), and contribution to the community (participation in meaningful community work). To this list, we added an emphasis on a participatory strategy of having youth identify their community concerns, and then plan and engage in social action to change underlying conditions contributing to food apartheid in their communities. In student exit interviews and focus groups youth spoke about how participation in ground-truthing activities increased their awareness of the social and environmental determinants of health that disproportionately affect their communities generally, and themselves personally, and ultimately inspired them to take action. As one African-American male student notes,

We went to different communities and what really stuck out to me was the huge differences that I’ve never noticed before in my daily life … we went inside stores and we seen them glorify and promote sales on unhealthy food, while in the wealthier community, they didn’t even sell any unhealthy food at all … we, the youth, need to do something to make things more equal … more healthy …. for our communities … – LeShawn (10th Grade)

A Latina student expands on her peer’s statement about how the mapping process can crystallize understanding of food apartheid and structural racism. She speaks more specifically about how the processes of ground-truthing and mapping give community- voice and community-driven data a platform to be considered as ‘valid’ as other sources of data and – ultimately – a vehicle for change:

It was very interesting, to finally show people what’s actually happening, because if you’re not aware of it, then you don’t really know what to fix, but once you finally find what the problem is you realize that you can do something to fix it – Norma (12th Grade)

Her African-American female classmate also shared her feelings on how the ground-truthing and mapping process not only changed her awareness of food apartheid but also influenced others in her community as well as policy-makers:

It makes people that are oblivious open up their eyes to what’s really happening. It’s like a wake-up call – Candia (11th Grade)

In this project we stressed principles of relevance -or starting where the youth are, participation, and the importance of creating environments in which individuals and youth become empowered as they increase their community understanding and problem- solving abilities. As evidenced through these stories/quotes from the young people involved in the project – as well as the policy- related outcomes in the earlier section – integrating YPAR 2.0 and ground-truthing strategies and techniques into classroom (and outside of classroom) practice and pedagogy can provide an effective foundation to achieve positive, and participatory, individual and community-change (Akom, Shah, & Nakai, 2016).

Limitations

As digital activism scholars have previously noted – there exist constraints with utilizing digital media as a tool to create change. However, rather then heralding digital tools as the source of social change, or dismissing it as ‘slacktivism’ – we encourage a more tempered approach which embraces digital tools while acknowledging it’s limitations. Technology is not a panacea. Nothing can replace the power and ability of everyday people to transform the social and material conditions that oppress them. But technology combined with traditional forms of community organizing can help. Digital tools can democratize decision-making in a ways that were previously not possible, in particular by allowing previously marginalized narratives to contest those put forward by the mainstream. With the penetration of mobile phones and other forms of technology growing in low-income and communities of color, digital tools will continue to provide opportunities to organize, mobilize, and transform social and material conditions in all communities. Importantly, any form of organizing, digital or otherwise, requires a strong facilitation/organization (either offline or online). In this project the role of experienced facilitators/researcher – who can both spark participant empowerment and decision-making and provide structure and guidance to help the group and its social action efforts move forward – was critical. Advance training for the facilitators/researchers proved critical to this project’s success. Facilitators/researchers also need a clear understanding of their role and how to serve as the holder of the vision of the project if a group was stuck. Ongoing dialogue between facilitators/researchers and youth – as well as frequent opportunities to debrief/discuss how to handle difficult situations are also essential to effective community organizing and community-building work with youth (Akom et al., 2016; Wilson et al., 2007; Wilson, Minkler, Dasho, Wallerstein, & Martin, 2008).

The next frontier: the social determinants of education

Schubert (2015) in his article ‘Designing and Directing Neighborhood Change Efforts’ discusses that there are two major schools of thought that inform the work of community revitalization and define the status quo. Each adds value, however both have limitations. YPAR 2.0 proposes a third way of approaching equitable development and educational transformation– one that builds and extends the first two yet offers a different way of engaging community and influencing change.

Schubert calls the first the development approach. This approach focuses on the built environment – redeveloping affordable housing, district energy and utilities, transforming brown fields, the maker movement, and improving green infrastructure. These are all important pieces in the puzzle of equitable development and important in creating opportunity rich neighborhoods for low-income youth attending public schools. Yet the ‘build beautiful stuff’ approach is often made with the assumption that with enough development the neighborhood will be changed – but the important question is changed for whom. Low income communities and communities of color are increasingly getting pushed out, dropped out, locked out, and forced out by developers, landlords, cities, schools, and governments. Most of these gentrifying communities are disproportionately working-class communities of color that have historically faced forms of American Apartheid like redlining, in which banks refused to lend to communities based on race (Just Cause, 2013; Massey & Denton, 1993). Simply put, the ‘build it and they will come approach’ is not sufficiently intentional about creating development without displacement policies and practices that provide baseline protections for vulnerable populations, preserves affordable housing, promotes access to healthy food, embraces non-market approaches to land use, ensures the right to return, and utilizes planning as a participatory process to create opportunity rich learning environments for all. As a result, even if millions or billions dollars are invested, community development and neo-liberal approaches to education can still fail if they are not meeting the needs of the most important stakeholders in the process – the people that have historically lived there and are living there now.

The second approach to ‘neighborhood revitalization’ and community transformation Schubert calls the comprehensive planning approach (Schubert, 2015). This approach challenges the development approach by suggesting that ‘building beautiful stuff alone’ is not sufficient to transform urban communities and schools. Instead, holistic community transformation also requires a range of social investments.

There is much in this approach that is positive and we should build on – engaging residents and promoting social investments as well as improve civic and green infrastructure (Schubert, 2015). But often this approach ignores the social and cultural community wealth of low-income communities and communities of color (Yosso, 2005). Low-income communities are not just a collection of issues or problems that need to be resolved. There is a lot of good stuff happening and working in poor communities that can be leveraged and built upon for strategic and targeted investment.

YPAR 2.0 in general, and Streetwyze in particular, builds and extends Schubert’s work and proposes a different way of thinking about neighborhood change and educational transformation – ‘not completely in opposition to these current ways of approaching neighborhoods but as a means to inform them and maximize the capacity for collective impact’ (Schubert, 2015, p. 12). This approach sees the conditions in schools as the sum total of lots of decisions – decisions by students, teachers, administrators, staff, residents, renters, home-owners, developers, investors, municipal government, prospective home buyers, lenders, and institutions. One challenge that is often overlooked in neo-liberal approaches to education is how do neighborhood conditions impact what teaching and learning happening inside of educational spaces and places (Blum & Coleman, 1970; Coleman, 1968). The YPAR 2.0 Model embraces what we call the Social Determinants of Education perspective – which we define as the ways in which race, class, gender, sexual orientation, ability, neighborhood conditions, and access to opportunity play as significant a role in educational outcomes and identity development as the quality of teachers. Neoliberal approaches to education seem to ignore the social determinants of education and as a result continue to misdiagnose the problem even-though the OCED’s most recent reported noted that ‘socio-economic disadvantage translates more directly into poor educational performance in the United States than in other countries (OCED, 2011).’ The intersecting lines of race, waste, and poverty are the invisible architects of educational disparities in low-income communities and communities of color.

Discussion

By implementing the YPAR 2.0 Model over three years, ISEEED and our community partners have learned a great deal about the challenges of enhancing and expanding community engagement, integrating people sensing, participatory technology, and social action to improve health outcomes. Many of the challenges that helped reform and refine the Model and are outlined below.

YPAR 2.0 is more than a set of research methods rather, it is an orientation to research that disrupts the role of power and privilege in the research relationship. Neoliberal approaches to educational reform tend to over-value ‘official’ knowledge and undervalue and de-legitimize ‘local’ knowledge (Corburn, 2005). Additionally, neoliberal approaches have been slow to understand the impact that digital tools are having on young people, and consequently, underemphasize the power that technology can have on teaching and learning both inside and outside of the classroom. For example community-generated data was effective at uncovering flawed government data sets and improve the accuracy of so-called ‘official’ data. Importantly, the social determinants to education and access to opportunity that is happening beyond the regulatory radar and underneath the veil of secondary data sets can be made visible by engaging and implementing the YPAR 2.0 Model.

More specifically, a YPAR 2.0 Model is an important model of research for vulnerable populations because it allows for a discovery-based learning process, capacity building, and culturally and community responsiveness to the needs of underserved communities that are embedded in the Model. In high poverty situations fraught with uncertainty, there is a need for a model that can unearth new hypotheses from a community-driven perspective rather than test predetermined ones (González et al., 2007). This is evidenced in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

YPAR 2.0 Model of research engagement. Source: Adapted from González et al. (2007).

In particular, I note the elements in the YPAR 2.0 Model that are participatory and bottom up and not fixed before hand. This is critical because of the complexity of environmental health issues happening in the urban context and the need for community capacity building (González et al., 2007, p. 90).

The classic neoliberal approach to research requires pre-defined hypotheses. However, in E. Oakland, and communities like it, the possible risk and rewards are so complex that it is difficult to form one hypothesis. Instead, a YPAR 2.0 Model suggests that young people can enter into a discovery-based mode of inquiry through a process of reflection and action that encourages the identification of multiple hypotheses and use local knowledge from different sources (González et al., 2007). In fact, the first few meetings of ‘people powered place-making’ workshops revolve around questions that the youth consider important and often reveal multiple dimensions of social vulnerability and multiple pathways to prosperity based on principles of asset based organizing approaches to youth and community empowerment.

Because tools like Local Ground and Streetwyze seamlessly integrate qualitative and quantitative data collection methodologies into our community engagement platforms, the YPAR 2.0 Model allows for discovery of new sources of social vulnerability that are invisible or barely audible. For example, youth could use Streetwyze to map their lived experience of public spaces like: ‘that’s the park where all the drugs are sold’. Youth also used Streetwyze to differentiate between different types of local amenities on the street level like liquor-stores vs. grocery stores that don’t show up in regulatory databases. Using ICT, Location-based, wireless, digital media, and participatory forms of technology also allowed youth from different cohorts to digitally organize and communicate even when students had never physically met in person. Howard Rheingold (2007) suggests that community-generated data technologies like Local Ground, Ushahidi, Streetwyze, Facebook, Instagram, snap chat and the ‘next big thing’ allow young people to act in ‘smart mobs’ and share ‘street knowledge’ ‘even when they do not know each other, and in ways they could not previously conceive, because the devices they use have both communication and computing capabilities’ (Etling, Faris, & Palfrey, 2010).

In this way YPAR 2.0 expands the capacity of traditional organizing and connects it with transformational resistance. According to Solorzano and Delgado-Bernal, transformative resistance is when

young people possess a social critique of the systems and structures which oppress them, and at the same time, the motivation for social justice. Because of this deeper knowledge and motivations, these students have the most potential to create social change or transform the oppressive situations and systems they exist within. (2001, pp. 319, 320)

By utilizing a YPAR 2.0 community engagement model, young people can engage in transformational resistance and address problems of systemic injustice and seek actions that foster ‘the greatest possibility for social change’ (2001, pp. 319, 320).

Another important lesson is how YPAR 2.0 and community partnerships created change in the community. A goal of many YPAR studies is to raise young people’s consciousness. And this study is no different. However, at the same time, by integrating consciousness raising with participatory technology, ground-truthing, and participatory planning – local policies were impacted and the young people were able to move from solely raising consciousness towards transforming social and material conditions in their communities. Thus YPAR 2.0 is more than a set of research skills, but rather the integration of technology and social action, which facilitates youth’s ability to ‘read the world,’ act as agents of change, and understand, validate, and act upon interpretations of digital data, and visual maps in order to improve their neighborhoods, schools, and communities.

Finally, our Model supports the growing recognition by researchers, educators, and policy makers of ‘creative place making’ and of the potential of learning through location-based technologies and digital media. In particular, ICT and digital media are important mechanisms for young people to speak truth to power, and the YPAR 2.0 Model helps young people develop and interrogate the research of others, and in doing so, gain an expanded understanding of themselves. A YPAR 2.0 orientation understands that data-driven models by themselves can distort schools systems and accountability measures in deep, invisible, and insidious ways. By encouraging critical creativity, people-powered place-making, and community commitment through self-awareness, YPAR 2.0 avoids the ‘data demi-god’ trap by promoting capacity building, critical dialogue, empowerment, self-determination, cooperation, and collection action.

Place also matters in terms of where our research center is located. We put ISEEED in the heart of the community because given the enormous historical and contemporary divides in access to food, housing, health care, economic, educational, and environmental forms of capital that are the daily reality for many youth of color in the United States and abroad – it is clear that neoliberal approaches to educational reform are not reaching the people who need them the most (Lipman, 2016). More specifically, we placed ISEEED in the heart of the community because universities founded on a commitment to public service are failing their stated educational missions – and unstated moral missions – for using their enormous wealth and cultural capital to bridge these gaps. In an effort to change universities’ relationships with communities, and break ivory tower approaches to educational reform, we began architecting pathways out of poverty for low income communities and communities of color using digital technologies and extended the work of MIT and others by created a community-driven lab where everyday people are the experts.

Although the YPAR 2.0 Model is still evolving, it does provide a critical framework for linking critical youth studies with the rapidly growing field of ICT, wireless technology, location-based technology, and digital media. Additionally, the YPAR 2.0 Model may be a powerful example of how we can democratize data and democratize decision-making in urban adolescent health promotion. By engaging youth in a process of identifying existing or missing community assets, organizations can paint a clear picture of the overall health status of their communities and organize around the cause of strengthening community resources. Tools like Streetwyze and Local Ground can also be used as a tool to raise community awareness and empowerment and show the impact of these organizing efforts. The possibilities are endless. The key is to find the technology that will work best within each context and inspire youth engagement and critical reflection ‘while balancing, staffing, available hardware, software, and other resources and youth talent, skills, and desires’ (Flicker et al., 2008, p. 299). The future is people-powered-placemaking and real-time feedback loops that enable everyday people to document and improve their social and material conditions. YPAR 2.0 can play an important role in the next wave of people powered place-making by helping smart mobs, smart social movements, and digital/traditional organizing tools inside and outside of classrooms and communities to use wireless networks to motivate participants, organize protests, recruit new members, communicate with mainstream media (and each other), and exert political influence, by integrating technological innovations with visible and invisible forms of resistance that lead to structural and individual forms of transformation.

Biographies

Antwi Akom, PhD, is Associate Professor in the Department of Africana Studies at SFSU where he directs the Neighborhood Innovation and Neighborhood Justice Alliance (The NINJA Research Group) – a joint research lab between UCSF and SFSU and is also an Affiliate Faculty with UCSF’s Center for Vulnerable Populations at San Francisco General Hospital. Dr. Akom’s work focuses on researching, developing, and deploying new health information communication technologies that amplify the voices of communities often excluded from digital and physical public spheres and connecting them with resources that improve health literacy, health care delivery, and promote equitable health outcomes for vulnerable populations. Dr. Akom is the co-founder of Streetwyze which has recently been recognized by President Obama, The White House, Rockefeller Foundation, Knight News Challenge and is the Co-Founding Director of the Institute for Sustainable Economic Educational and Environmental Design (ISEEED.org) – an award winning community-based center for research, teaching, and action. His current research examines the linkages between race, built environment, science, technology, and environmental justice using mobile platforms and participatory action research approaches to promote community engagement, social innovation, and neighborhood revitalization.

Aekta Shah is currently pursuing her PhD in Technology Design at Stanford University and is the recipient of the prestigious Stanford Graduate Fellowship. At Stanford, her research and work range from running Design-thinking workshops at the Stanford d.School to developing new social impact technology and community engaged design ideas to catalyze equitable economic development in low-income communities and communities of color in collaboration with the Stanford Graduate School of Business. Aekta is also Director of Technology and Community engagement at ISEEED and the co-founder and COO of Streetwyze: which has recently been recognized by President Obama, The White House, Rockefeller Foundation, Knight News Challenge and others. Aekta’s areas of expertise include research and development on issues of participatory technology, GIS mapping, and sustainable community development.

Aaron Nakai is a critical educator who has served as a trainer, mentor, community-based participatory action researcher and youth development specialist in various spaces for the past 15 years. His graduate studies include a Master’s of Education focused on Equity and Social Justice from San Francisco State University. He is currently the Program Director of Health Equity and Youth Engagement at the Institute for Sustainable Economic, Educational and Environmental Design (I-SEEED) in Oakland, CA. His work includes designing health and environmental equity curriculum, implementing community-based action research projects with young people and their families, and co-teaching early college/model high school classes in urban ecology, ethnic studies, health equity and environmental justice.

Tessa Cruz is the Director of Outreach and Engagement at Streetwyze and the Program Manager of Equitable Development and Community-Engaged Design at ISEEED, The Institute for Sustainable Economic, Educational and Environmental Design. Previously, Tessa served as the public programming and public policy intern at SPUR, a San Francisco Urban Policy and Research think tank, assisting with the organization’s community outreach and education efforts, as well as ballot analysis research for San Francisco’s November 4th 2014 ballot. She is a recent graduate of Oberlin college, where she earned a BA in Environmental Studies and was heavily involved in community service within the City of Oberlin, serving as a critical liaison between various college and city communities.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Adelman L. Unnatural causes: Is inequality making us sick? Preventing Chronic Disease. 2007;4(4) [Google Scholar]

- Agyeman J. Just sustainabilities: Development in an unequal world. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Akom AA. Ameritocracy and infra-racial racism: Racializing social and cultural reproduction theory in the twenty-first century. Race Ethnicity and Education. 2008;11:205–230. [Google Scholar]

- Akom AA. Critical race theory meets participatory action research: Creating a community of youth as public intellectuals. In: Ayers W, Quinn T, Stovall D, editors. Social justice in education handbook. New York, NY: Erlbaum Press; 2009a. pp. 508–521. [Google Scholar]

- Akom AA. Research for liberation: Du Bois, the Chicago school, and the development of black emancipatory action research. In: Anderson NS, Kharem H, editors. Education as a practice of freedom: African American educational thought and ideology. New York, NY: Lexington Press; 2009b. pp. 193–212. [Google Scholar]

- Akom AA. Eco-apartheid: Linking environmental health to educational outcomes. Teachers College Record. 2011a;113:831–859. [Google Scholar]

- Akom AA. Black emancipatory action research: Integrating a theory of structural racialisation into ethnographic and participatory action research methods. Ethnography and Education. 2011b;6:113–131. [Google Scholar]

- Akom AA, Cammarota J, Ginwright S. Youthtopias: Towards a new paradigm of critical youth studies. Youth Media Reporter. 2008;2:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Akom AA, Scott A, Shah A. Rethinking resistance theory through STEM education: How working class kids get world class careers. In: Tuck E, Yang KW, editors. Youth resistance research and theories of change. Routledge; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Akom AA, Shah A, Nakai A. Visualizing change: Using technology and participatory research to engage youth in urban planning and health promotion. In: Hall H, Robinson CC, Kohli A, editors. Uprooting urban America: Multidisciplinary perspectives on race, class and gentrification. New York, NY: Peter Lang; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Akom AA, Shah A, Nakai A. Kids, kale, and concrete: Using participatory technology to transform an urban American food desert. In: Noguera P, editor. Race, equity, and education. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016. pp. 75–102. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Kodmany K. Public participation: Technology and democracy. Journal of Architectural Education. 2000;53:220–228. [Google Scholar]

- Alkon AH, Norgaard KM. Breaking the food chains: An investigation of food justice activism. Sociological Inquiry. 2009;79:289–305. [Google Scholar]

- Alter DA, Eny K. The relationship between the supply of fast-food chains and cardiovascular outcomes. Revue Canadienne de Sante’e Publique [Canadian Journal of Public Health] 2005;1:173–177. doi: 10.1007/BF03403684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. Streetwise: Race, class, and change in an urban community. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Basch C. Healthier students are better learners: A missing link in school reforms to close the achievement gap. Journal of School Health. 2011;81:593–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell J, Lee MM. Report. Oakland, CA: Policy Link; 2011. Why place and race matter: Impacting health through a focus on race and place. Retrieved from http://www.policylink.org/atf/cf/%7B97c6d565-bb43-406d-a6d5-eca3bbf35af0%7D/WPRM%20FULL%20REPORT,20. [Google Scholar]

- Belot M, James J. Healthy school meals and educational outcomes. Journal of Health Economics. 2011;30:489–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block JP, Scribner RA, DeSalvo KB. Fast food, race/ethnicity, and income: A geographic analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;27:211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum ZD, Coleman JS. Longitudinal effects of education on the incomes and occupational prestige of blacks and whites. 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Bonam CM, Eberhardt JL, Markus H, Ross L. Devaluing black space: Black locations as targets of housing and environmental discrimination. Stanford University; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva E. White supremacy and racism in the post-civil rights era. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Brownell KD, Horgen KB. Food fight: The inside story of the food industry, America’s obesity crisis, and what we can do about it. Chicago, IL: Contemporary Books; 2004. p. 69. [Google Scholar]

- Bullard R. Dumping in Dixie: Race, class, and environmental quality. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bullard RD, Johnson GS, Torres AO, editors. Transportation racism and new routes to equity. Cambridge, MA: South End Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Camino L. Pitfalls and promising practices of youth–adult partnerships: An evaluator’s reflections. Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;33:75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Cammarota J, Fine M, editors. Revolutionizing education: Youth participatory action research in motion. New York, NY: Routledge; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Haggerty KP, Oesterle S, Fleming CB, Hawkins JD. The importance of bonding to school for healthy development: Findings from the social development research group. Journal of School Health. 2004;74:252–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen BE. Community food security assessment toolkit. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2002. pp. 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JS. Equality of educational opportunity. Integrated Education. 1968;6:19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH. Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness and the politics of empire. Boston: Unwin Hyman; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH. Some group matters: Intersectionality, situated standpoints, and black feminist thought. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Corburn J. Combining community-based research and local knowledge to confront asthma and subsistence-fishing hazards in Greenpoint/Williamsburg, Brooklyn, New York. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2002;110(Suppl 2):241. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s2241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corburn J. Street science: Community knowledge and environmental health justice. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dance LJ. Tough fronts: The impact of street culture on schooling. New York, NY: RoutledgeFalmer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Darden JT. The residential segregation of Blacks in Detroit, 1960–1970. International Journal of Comparative Sociology. 1986;17:84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan-Andrade JMR, Morrell E. The art of critical pedagogy: Possibilities for moving from theory to practice in urban schools. New York, NY: Peter Lang; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan-Andrade JMR. The principal facts: New directions for teacher education. In: Ball AF, Tyson CA, editors. Studying Diversity in Teacher Education. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield; 2011. pp. 309–326. [Google Scholar]

- Etling B, Faris R, Palfrey J. Political change in the digital age: The fragility and promise of online organizing. SAIS Review of International Affairs. 2010;30:37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Flicker S, Maley O, Ridgley A, Biscope S, Lombardo C, Skinner HA. e-PAR Using technology and participatory action research to engage youth in health promotion. Action Research. 2008;6:285–303. [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Bloomsbury; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gatenby B, Humphries M. Feminist participatory action research: Methodological and ethical issues. Women’s Studies International Forum. 2000 Feb;23:89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Ginwright SA. Black youth rising: Activism and radical healing in urban America. New York, NY: Teachers College Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ginwright SA, Noguera P, Cammarota J, editors. Beyond resistance! Youth activism and community change: New democratic possibilities for practice and policy for America’s youth. New York, NY: Routledge; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- González ER, Lejano RP, Vidales G, Conner RF, Kidokoro Y, Fazeli B, Cabrales R. Participatory action research for environmental health: Encountering Freire in the urban barrio. Journal of Urban Affairs. 2007;29:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Hacker A. Two nations: African American and white, separate, hostile, unequal. New York, NY: Scribner; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hall BL. Participatory research, popular knowledge and power: A personal reflection. Convergence. 1981;14:6. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks B. Feminist theory: From margin to center. London: Pluto Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson-Weems C. Africana womanism: Reclaiming ourselves. Troy, MI: Bedford Publishers; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- ICT Data and Statistics Division. ICT Facts & Figures. The world in 2015. 2015 Retrieved from https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Documents/facts/ICTFactsFigures2015.pdf.

- Just Cause. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.cjjc.org/publications/reports.

- Kelley R. Race rebels: Culture, politics, and the black working class. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Khanlou N, Peter E. Participatory action research: Considerations for ethical review. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;60:2333–2340. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lax W, Galvin K. Reflections on a community action research project: Interprofessional issues and methodological problems. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2002;11:376–386. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2002.00622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart A, Purcell K, Smith A, Zickuhr K. Pew Internet & American Life Project. 2010. Social media & mobile internet use among teens and young adults. Millennials. [Google Scholar]

- Lipman P. The new political economy of urban education: Neoliberalism, race, and the right to the city. New York, NY: Routledge; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod J. Ain’t no makin’ it: Aspirations and attainment in a low-income neighborhood. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1987/1995. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Denton NA. American apartheid: Segregation and the making of the underclass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M. Community-based research partnerships: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Urban Health. 2005;82:ii3–ii12. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morello-Frosch R, Pastor M, Jr, Sadd J. Integrating environmental justice and the precautionary principle in research and policy-making: The case of ambient air toxic exposures and health risks among schoolchildren in Los Angeles. ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2002;584:47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Morello-Frosch R, Zuk M, Jerrett M, Shamasunder B, Kyle AD. Understanding the cumulative impacts of inequalities in environmental health: Implications for policy. Health Affairs. 2011;30:879–887. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrell E. Critical literacy and urban youth: Pedagogies of access, dissent, and liberation. New York, NY: Routledge; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nasir NIS, Rosebery AS, Warren B, Lee CD. Learning as a cultural process: Achieving equity through diversity. In: Sawyer K, editor. The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 489–504. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen Multiplying mobile: How multicultural consumers are leading smartphone adoption. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/news/2014/multiplying-mobile-how-multicultural-consumers-are-leading-smartphone-adoption.html.