Abstract

Objective:

Although the high prevalence of mental health issues among postsecondary students is well documented, comparatively little is known about the adequacy, accessibility, and adherence to best practices of mental health services (MHSs)/initiatives on postsecondary campuses. We evaluated existing mental health promotion, identification, and intervention initiatives at postsecondary institutions across Canada, expanding on our previous work in one Canadian province.

Methods:

A 54-question online survey was sent to potential respondents (mainly front-line workers dealing directly with students [e.g., psychologists/counsellors, medical professionals]) at Canada’s publicly funded postsecondary institutions. Data were analyzed overall and according to institutional size (small [<2000 students], medium [2000–10 000 students], large [>10 000 students]).

Results:

In total, 168 out of 180 institutions were represented, and the response rate was high (96%; 274 respondents). Most institutions have some form of mental health promotion and outreach programs, although most respondents felt that these were not a good use of resources. Various social supports exist at most institutions, with large ones offering the greatest variety. Most institutions do not require incoming students to disclose mental health issues. While counselling services are typically available, staff do not reliably have a diverse complement (e.g., gender or race diversity). Counselling sessions are generally limited, and follow-up procedures are uncommon. Complete diagnostic assessments and the use of standardized diagnostic systems are rare.

Conclusions:

While integral MHSs are offered at most Canadian postsecondary institutions, the range and depth of available services are variable. These data can guide policy makers and stakeholders in developing comprehensive campus mental health strategies.

Keywords: campus mental health, postsecondary students, assessment

Abstract

Objectifs:

Bien que la prévalence élevée des problèmes de santé mentale chez les étudiants post-secondaires soit bien documentée, nous en savons relativement peu sur la conformité, l’accessibilité et l’adhésion aux « pratiques exemplaires » des services/initiatives de santé mentale sur les campus post-secondaires. Nous avons évalué la promotion, l’identification et les initiatives d’intervention en santé mentale existantes dans les institutions post-secondaires du Canada, une prolongation de nos travaux précédents dans une province canadienne.

Méthodes:

Un sondage en ligne de 54 questions a été envoyé aux répondants potentiels (principalement des travailleurs de première ligne en contact direct avec les étudiants (p. ex., des psychologues/conseillers, des professionnels de la santé) dans les institutions post-secondaires publiques du Canada. Les données ont été analysées globalement, et selon la taille de l’institution (petite [< 2 000 étudiants], moyenne [2 000-10 000 étudiants], grande [> 10 000 étudiants]).

Résultats:

Au total, 168 institutions sur 180 étaient représentées, et le taux de réponse était élevé (96%; 274 répondants). La plupart des institutions avaient une certaine forme de promotion de la santé mentale et de programmes de sensibilisation, même si les répondants croyaient pour la plupart que ceux-ci n’étaient pas une bonne utilisation des ressources. Divers soutiens sociaux existent dans la plupart des institutions, et les grandes institutions en offrent la plus large variété. La plupart des institutions ne demandent pas aux nouveaux étudiants de divulguer leurs problèmes de santé mentale. Bien que des services de consultation soient typiquement disponibles, le personnel n’offre pas de complément sérieux sur la diversité (p. ex., la diversité des genres ou raciale). Les séances de consultation sont généralement limitées, et les procédures de suivi sont peu communes. Les évaluations diagnostiques complètes et l’utilisation des systèmes diagnostiques normalisés sont rares.

Conclusions:

Bien que des services de santé mentale intégraux soient offerts dans la plupart des institutions post-secondaires canadiennes, la gamme et la profondeur des services offerts sont variables. Ces données peuvent guider les décideurs et les intervenants pour élaborer des stratégies détaillées de santé mentale sur les campus.

Clinical Implications

Most publicly funded postsecondary institutions in Canada offer some elements of mental health promotion, identification, and treatment services.

The accessibility of MHSs is variable across Canadian postsecondary institutions.

Evaluations of MHSs are needed at postsecondary schools.

Limitations

Certain components of mental health provisions/initiatives on campuses were not assessed.

Regional variations in campus MHSs/initiatives were not assessed.

There is limited information regarding best MHSs/practices for PSSs and universities/colleges, making it difficult to evaluate the quality of the services provided.

Psychiatric disorders (and coincident suicides) are common in adolescents/young adults1–5 and negatively influence their academic, occupational, and social development.6 Concern for the mental health of postsecondary students (PSSs), in particular, has garnered increased attention. In the United States, 15% to 20% of PSSs reported being treated for some form of mental disorder,7 while 17% screened positive for depression and 15% for nonsuicidal self-injuries.8 A report by the Ontario College Health Association found PSSs to be more than twice as likely to report mental illness symptoms and elevated distress than nonuniversity youth.9 Others, however, have noted comparable rates of psychiatric disorders among PSSs and age-matched populations,10 suggesting that PSSs may be more likely to disclose psychiatric issues or seek help. Further, the nature of distress in PSSs may be transient since the transition to postsecondary education is an acute stressor.11 Regardless, while it is recognized that mental health issues are prevalent among PSSs,12 less is known about the nature and effectiveness of available campus mental health services (MHSs).

Postsecondary institutions face challenges when attempting to prevent, identify, and treat mental illnesses on campus (e.g., fragmented services, reactive responses, piecemeal funding, high resource needs9). They report struggling with an increase in student psychopathology, severity of issues, and counselling services usage.13–15 This may be related to increased numbers of nontraditional groups on campus (e.g., students with disabilities),16 treatment advances,17 and/or a greater willingness to report mental health issues and seek treatment.18 The pressure on strained campus MHSs is especially true at smaller institutions, which tend to have fewer staff (including mental health professionals), budgetary constraints, and dual relationship/boundary concerns.19

While the goal of postsecondary institutions is not necessarily to provide psychiatric interventions per se, most strive towards creating a mental health strategy that supports students. Despite the challenges in constructing comprehensive strategies for postsecondary institutions, guidelines have started to emerge.20 Further, some research has assessed the success of certain initiatives based on “best practices” with respect to addressing mental illness/distress on campuses. One best practice is for prevention efforts to target high-risk populations, such as LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender), international, and first-year students.21,22 Prevention initiatives should be focused on reducing stress, providing social support, and encouraging self-care.23 Additionally, campus programs focused on early identification and intervention, such as gatekeeper training (i.e., identifying suicidal/distressed students and referring them to appropriate resources),24 can foster an environment that deals more effectively with students’ mental health needs.25–27 Finally, integrating and sharing information among campus MHS groups, as well as encouraging students to use available disability/accessibility services, is viewed as an optimal service provision strategy.23

There are knowledge gaps regarding the services that postsecondary institutions are currently offering, whether/which best practices are implemented, and the feasibility of providing comprehensive mental health programs by institutions. The current study broadens our previous work, which evaluated postsecondary MHSs in the province of Alberta,28 to the national level. The Alberta survey identified the need for institutions to evaluate campus mental health initiatives and develop strategies to optimize mental health among students (e.g., tracking success/retention of students who access campus MHSs). This likely entails a comprehensive approach that identifies priority problems and establishes long-term goals to address them.

Our primary aim was to acquire a comprehensive, nationwide understanding of MHSs that Canadian postsecondary institutions are providing (i.e., assess the current state of MHSs on campuses). An assessment of the national scene is a necessary precursor for comparing regional patterns in campus MHSs/initiatives. As a secondary aim, we were interested in the extent to which services varied as a function of institutional size, as suggested by the literature, and whether these differences were consistent with what was observed in the Alberta study.28 These data should allow institutions to compare their services with similar-sized schools as a starting point for analyzing local service gaps and developing comprehensive mental health policies.

Methods

Survey Development and Overview

This project was approved by the University of Calgary’s Research Ethics Board. The survey was an update of the original, which was refined for clarity, readability, and user-friendliness,28 and adhered to the recommendations for survey data collection.29 A literature search on strategies/programs relevant to mental health at postsecondary institutions guided question development.

The survey (54 items; French/English) (available online) was disseminated via email using SurveyMonkey (www.surveymonkey.com). Most items (ordinal responses) pertained to institutional mental health promotion, outreach, identification, and intervention services/initiatives (defined in the survey). “Promotion” referred to programs/initiatives with the goal of increasing mental health awareness. “Outreach” referred to encouraging students with known or potential issues to seek help; questions on initiatives to identify such students were included. Additional items assessed social supports and campus climate, including questions on stress reduction and self-care initiatives. Finally, questions regarding campus medical, counselling, and accessibility services as well as mental health policies were incorporated. Some questions were opinion based, and most permitted commenting.

Participants and Procedures

One hundred eighty publicly funded Canadian postsecondary institutions were identified by searching the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada and Colleges and Institutes Canada websites. Survey invitations were emailed to 286 potential respondents (purposive sampling29). Respondents were identified through institutional websites or by communicating directly with staff. Participants were selected based on their perceived knowledge/involvement with campus MHSs (i.e., individuals with job titles/descriptions that identified them as front-line workers dealing with students, such as counsellors/psychologists and resident advisors [RAs]). Individuals who appeared to be most informed regarding available campus services were solicited. If a respondent did not complete the survey after the initial request, a reminder was sent after 1 week, and a second reminder was sent as necessary (January to August 2014). When possible, 2 or more responders per institution were contacted. Study personnel analyzing the data did not have access to respondents’ personal information (i.e., a third person de-identified responses pre-analyses). Respondents were assured of confidentiality/anonymity at the beginning of the survey.

Data Synthesis

Surveys from multiple respondents at one institution were combined to develop a representative profile.28 For additive questions, multiple responses were summed. If the response option was categorical and multiple responses from the same institution differed, the institutional profile reflected the majority or was coded as “unsure.” For Likert scale questions, responses were analyzed for all respondents (not combined).

Summary data (%) and results per institution size (small [S]: <2000 students; medium [M]: 2000–10 000 students; large [L]: >10 000 students) are presented. Responses from institutions with satellite campuses were combined with the parent institution if the satellite was small and close to the main campus (likely shared resources). Satellite schools were considered independent institutions if they were large/medium, not in close proximity to the main campus, or listed independently on government websites.

Categorical responses (e.g., yes/no) between S, M, and L schools were compared using Pearson chi-square tests; significant tests (P < 0.05) were followed by chi-square tests to identify response differences between school sizes (P < 0.02).

Results

Responder and Institutional Information

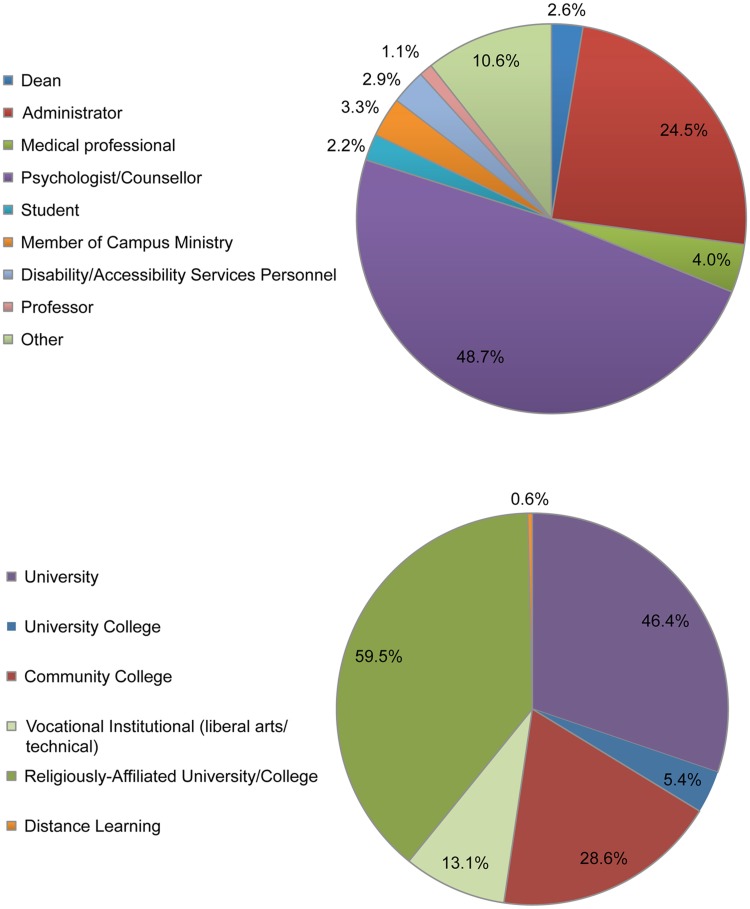

Of the 286 individuals contacted, 274 completed the survey (96%). Most institutions were represented (n = 168/180; 48 S, 60 M, 60 L; 4 S, 8 M, 0 L not represented). Of these, 13% had 3 to 4, 34% had 2, 56% had 1, and 7% had 0 respondent(s). Positions of respondents and institutional types/categories are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Upper graph: Positions of postsecondary institution respondents. “Other” represents positions such as campus life coordinator, student outreach coordinator, or support staff. Lower graph: Types of postsecondary institutions represented in the mental health survey.

Mental Health Promotion and Outreach

A majority of institutions (73%) reported that they had campus mental health promotion programs. A relation between school size and response existed (χ2(9,226) = 254.90, P < 0.001; S: 54%, M: 72%, L: 92% responded positively); follow-up tests indicated a difference in responses between all school sizes (P < 0.001). The counselling centre/student counsellor was most commonly identified as responsible for mental health promotion. At S institutions, the student affairs office, students’ association, and residence staff/RAs also had a big role. At M and L institutions, promotion was carried out by the accessibility/disability office and campus medical services. Across institutions, promotion programs aimed to inform students about available campus MHSs, reduce stigma, and educate students about mental illness, in that order. Mental health issues targeted by promotion programs are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Targeted mental health issues of mental health promotion programs at postsecondary institutions.

| Targeted promotion programs (%) | Small (n = 48) | Medium (n = 60) | Large (n = 60) | Average (n = 168) | Chi-square test (P value)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol abuse | 37.5 | 41.7 | 48.3 | 42.5 | N.S. (0.51) |

| Drug abuse | 29.2 | 30.0 | 33.3 | 30.8 | N.S. (0.85) |

| Eating disorders | 20.8 | 20.0 | 41.7 | 27.5 | 0.013 |

| Depression | 39.6 | 38.3 | 48.3 | 42.1 | N.S. (0.49) |

| Bipolar disorder/schizophrenia | 12.5 | 11.7 | 11.7 | 12.0 | N.S. (0.99) |

| Suicide | 35.4 | 36.7 | 48.3 | 40.1 | N.S. (0.30) |

| Stress/anxiety | 41.7 | 51.7 | 70.0 | 54.5 | 0.010 |

| Focus is only on promoting mental health as a whole | 27.0 | 23.3 | 10.0 | 16.8 | N.S. (0.057) |

Small: <2000 students; medium: 2000–10 000 students; large: >10 000 students. N.S. = not significant.

aChi-square tests represent the results of the 3 school sizes (P > 0.05).

Most institutions engage in mental health outreach (86% overall; not significant [N.S.] relation between school size and response), with the counselling centre being primarily responsible for this (S: 60%, M: 78%, L: 83%; N.S.). At S institutions, the student affairs office also plays a large role, while at M and L ones, the accessibility/disability office is active in outreach. Groups most frequently targeted by outreach initiatives in S institutions are Aboriginal, international, and LGBT students, although 34% indicated that targeted outreach initiatives did not exist (M: 30%, L: 27%; N.S.). At M/L institutions, international students are the most frequent targets of outreach initiatives, followed by Aboriginal students at M ones and LGBT groups at L ones. First-year students are common targets for outreach, with 75% of all respondents indicating that information about available campus MHSs is provided as part of the first-year orientation.

Professors are able to request presentations on mental health promotion and outreach/intervention at most institutions (71% overall; 16% unsure). However, 52% of respondents from S institutions and 43% from M institutions indicated that such presentations are rarely/never requested (35% at L ones; N.S. relation between school size and response). Classroom outreach, through mental health curriculum integration programs, was largely absent, although uncertainty was high.

Seventy-four percent of all respondents agreed (somewhat to strongly) that students are informed about mental health and available services. However, 84% agreed that their institutions could benefit from expanding mental health promotion and outreach programs. Not as many respondents were confident that current promotion programs were an effective and good use of campus resources/budgets; 41% of respondents from S (21% unsure), 49% from M (8% unsure), and 35% from L (8% unsure; N.S.) institutions agreed with this. Only a minority endorsed current outreach programs as an effective use of resources (43% overall). There was a relation between school size and response (χ2(6,225) = 13.71, P = 0.033), with a difference between S and M/L schools (P < 0.05; positive response: S: 36%, M: 43%, L: 50%; unsure/neutral response: S: 33%, M: 21%, L: 25%).

Social Support and Mental Health Climate on Campus

For S institutions, peer support centres are the most commonly available support structures, followed by the Aboriginal centre and LGBT club/safe meeting space. Almost a third of S institutions (31%) do not have specific social supports in place (M: 8%, L: 0%; relation between school size and response [χ2(2,168) = 24.87, P < 0.001]); follow-up tests indicated a difference between S versus M/L schools (P < 0.001). For M ones, the Aboriginal centre, international students’ centre, and LGBT club are the most frequent social supports. L institutions are most likely to report having multiple types of social supports. Fifteen percent of S institutions indicated that they either have no specific support services for international students or do not usually host them (relation between school size and response [χ2(2,168) = 10.28, P = 0.006]); responses for S institutions differed from L ones (P = 0.002; L: 0%, M: 5%). Specific supports for first-year students are outlined in Table 2.

Table 2.

Support services for first-year students and other services offered to students that contribute to a healthy mental health campus climate at postsecondary institutions.

| Small (n = 48) | Medium (n = 60) | Large (n = 60) | Average (n = 168) | Chi-square test (P value)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support services for first-year students (%) | |||||

| Orientation | 72.9 | 75.0 | 80.0 | 76.0 | N.S. (0.67) |

| Peer tutors | 47.9 | 53.3 | 63.3 | 54.8 | N.S. (0.27) |

| Transition program | 31.3 | 40.0 | 48.3 | 39.9 | N.S. (0.14) |

| Mentors | 20.8 | 38.3 | 56.7 | 38.6 | <0.001 |

| Advisors | 54.2 | 61.7 | 68.3 | 61.4 | N.S. (0.32) |

| Workshops | 54.2 | 58.3 | 76.7 | 63.1 | 0.03 |

| None of the above | 4.2 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 2.0 | N.S. (0.27) |

| Other services offered to students (%) | |||||

| Access to a recreation centre/gymnasium | 52.1 | 75.0 | 83.3 | 70.1 | 0.0013 |

| Opportunity to participate in a wellness program | 31.3 | 48.3 | 56.7 | 45.4 | 0.029 |

| Access to a meditation centre | 27.1 | 36.7 | 50.0 | 37.9 | 0.048 |

| On-campus preventive health care programs | 33.3 | 46.7 | 66.7 | 48.9 | 0.0022 |

| Programs facilitating community involvement | 50.0 | 56.7 | 70.0 | 58.9 | N.S. (0.093) |

| Programs facilitating campus involvement | 64.6 | 65.0 | 81.7 | 70.4 | N.S. (0.071) |

| Unsure | 2.1 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 1.8 | N.S. (0.26) |

Small: <2000 students; medium: 2000–10 000 students; large: >10 000 students. N.S. = not significant.

aChi-square tests represent the results of the 3 school sizes (P > 0.05).

Almost three-quarters of all institutions (74%) have a student residence (S: 58%, M: 80%, L: 85%; relation between school size and response [χ2(2,137) = 16.79, P < 0.001]); follow-up tests indicated a difference between S and M/L institutions (P < 0.01). RAs/residence staff are typically trained in crisis intervention at S (40%) and M (52%) institutions; at L ones, they are most commonly trained to know about available campus resources (73%). One in 3 of all institutions have programs to train students to be “leaders” for mental health awareness on campus. Table 2 lists services that contribute to a healthy campus climate.

Identification

Most institutions do not require incoming students to fill out a medical/mental history questionnaire; only 8% do. Gatekeeper training programs, most commonly provided to RAs, are available at 27%, 40%, and 62% of S, M, and L institutions, respectively (χ2(4,137) = 11.86, P = 0.018); follow-up tests indicated a difference between S and L institutions (P = 0.003). Other measures to identify/report students in distress are presented in Table 3. Among S institutions, the most common means of identification is through self-referral; at M and L ones, it is via the counselling centre website (electronic self-referral). A minority of schools have an “early alert program.”

Table 3.

Methods used to identify/report students in distress at postsecondary institutions.

| Identification/reporting methods (%) | Small (n = 48) | Medium (n = 60) | Large (n = 60) | Average (n = 168) | Chi-square test (P value)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression screening | 20.8 | 26.7 | 46.7 | 31.4 | 0.0089 |

| Drinking problem screening | 20.8 | 26.7 | 36.7 | 28.1 | N.S. (0.18) |

| Problem with video gaming/online gambling screening | 10.4 | 16.7 | 23.3 | 16.8 | N.S. (0.21) |

| Substance abuse screening | 20.8 | 18.3 | 36.7 | 25.3 | 0.048 |

| Problematic eating patterns screening | 12.5 | 18.3 | 28.3 | 19.7 | N.S. (0.079) |

| “At-risk” student committees | 35.4 | 20.0 | 53.3 | 36.2 | <0.001 |

| Information on counselling website | 31.3 | 58.3 | 73.3 | 54.3 | <0.001 |

| Telephone hotline for students in distress | 18.8 | 40.0 | 46.7 | 35.2 | 0.0085 |

| Confidential email service | 16.7 | 31.7 | 23.3 | 23.9 | N.S. (0.19) |

| Onus is on students to self-refer | 54.2 | 45.0 | 48.3 | 49.2 | N.S. (0.64) |

Small: <2000 students; medium: 2000–10 000 students; large: >10 000 students. N.S. = not significant.

aChi-square tests represent the results of the 3 school sizes (P > 0.05).

Campus Medical Services, Counselling Services, and Disability/Accessibility Services

On-campus medical services are offered at 31%, 67%, and 85% of S, M, and L institutions, respectively (χ2(4,136) = 32.91, P < 0.001); follow-up tests indicated response differences between S/M compared with L schools (P < 0.02). Ninety-one percent of schools offer some form of on-campus counselling services. Most provide this through a designated counselling office/centre or wellness centre (S: 63%, M: 75%, L: 87%; χ2(2,168) = 7.21, P = 0.027); follow-up assessments yielded a difference in responses between S and L schools (P = 0.007). Of those with dedicated counselling offices/centres, the most commonly employed professionals are psychologists, followed by therapists. Two-thirds of schools have designated walk-in times for students needing immediate help. Smaller institutions were less likely to employ a triage system (students needing urgent care are seen first) (S: 35%, M: 57%, L: 73%; relation between school size and response [χ2(2,168) = 15.06, P < 0.001]); follow-up tests indicated a difference between S versus L schools (P < 0.001). Table 4 presents services offered by the counselling centre/services and further options for students.

Table 4.

Specifics regarding the services and options provided by counselling centres/services at postsecondary institutions.

| Small (n = 48) | Medium (n = 60) | Large (n = 60) | Average (n = 168) | Chi-square test (P value)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Counselling services offered (%) | |||||

| Personal counselling | 66.7 | 75.0 | 83.8 | 75.0 | N.S. (0.13) |

| Counselling for international students | 56.3 | 70.0 | 76.7 | 67.7 | N.S. (0.07) |

| Counselling for Aboriginal students | 50.0 | 58.3 | 63.3 | 57.2 | N.S. (0.25) |

| Academic counselling | 58.0 | 51.7 | 55.0 | 54.9 | N.S. (0.84) |

| Career counselling | 54.2 | 50.0 | 60.0 | 54.7 | N.S. (0.96) |

| Crisis counselling | 54.2 | 68.3 | 76.7 | 66.4 | 0.046 |

| Options offered for students seeking help (%) | |||||

| Student assistance programs | 37.5 | 36.7 | 41.7 | 38.6 | N.S. (0.86) |

| Peer counsellors | 20.8 | 16.7 | 28.3 | 21.9 | N.S. (0.27) |

| Mental health information available online | 35.4 | 50.0 | 75.0 | 53.5 | <0.001 |

| Opportunity to talk with a counsellor over the telephone | 37.5 | 38.3 | 40.0 | 38.6 | N.S. (0.96) |

| Self-help programs | 31.3 | 13.3 | 35.0 | 26.5 | 0.017 |

| Group help programs | 18.8 | 28.3 | 51.7 | 32.9 | <0.001 |

| Referrals to psychiatrists/physicians | 45.8 | 60.0 | 65.0 | 56.1 | N.S. (0.12) |

Small: <2000 students; medium: 2000–10 000 students; large: >10 000 students. N.S. = not significant.

aChi-square tests represent the results of the 3 school sizes (P > 0.05).

Counselling centre/services staff are offered cross-cultural training at 48%, 63%, and 75% of S, M, and L institutions, respectively (N.S.); most staff have suicide prevention training (S: 69%, M: 78%, L: 90%; N.S.). A greater number of respondents from L institutions (64%) rated their staff to be diverse on aspects such as gender, race, or nationality compared to S (35%) and M (31%) institutions (relation between school size and response [χ2(6,126) = 26.79, P < 0.001]); follow-up tests indicated a difference in responses between L versus S/M schools (P < 0.001).

A sizeable proportion of respondents indicated that counselling sessions are limited in number (42%; the majority of S school respondents skipped this question). The limit is typically 6 to 10 (∼1 hour each), although respondents commented that restrictions were flexible. Across all institutions, only a minority (16%) provide a complete diagnostic, psychosocial, and functional assessment during the visit (uncertainty/nonresponse was high).

Overall, a limited proportion of respondents indicated that formalized diagnostic systems were used at their institution (yes: 21%, no: 48%). About half do not provide long-term therapy (53%) but refer students needing further care to appropriate off-campus services. Overall, 28% reported using a follow-up system to ensure that referrals are completed, although uncertainty and nonresponse was high (24%/13%, respectively ).

Most institutions offer disability/accessibility services, which facilitate classroom accommodations, provide needs assessments, and develop individual service plans (S: 79%, M: 87%, L: 95%; χ2(4,131) = 13.19, P = 0.01); follow-up tests yielded a difference between S versus L schools (P = 0.011). However, only about half of respondents indicated that these services include staff with mental health training (high uncertainty).

Discussion

This study examined the current state of MHSs/initiatives at Canadian postsecondary institutions. An up-to-date understanding of MHSs across Canadian campuses is lacking; such information is a critical first step for regional investigations/comparisons. In our previous study of Alberta’s postsecondary institutions,28 we found notable differences in MHSs/initiatives according to institution size; thus, we wanted to explore this on a national scale. Our response rate was high, increasing the probability that the data present a generalizable portrayal of campus MHSs/initiatives.

This survey addressed the need to define the responsibilities that universities/colleges have with respect to student mental health, as “duty to care” encompasses this domain.30 The first step in exercising duty to care lies in the provision of campus mental health promotion/outreach programs. Such programs are critical, as students may not seek help because of stigma, limited knowledge about available campus MHSs, or both.25,26,31 Enhancing promotion/outreach programs targeting specific disorders (e.g., addictions, eating disorders) was identified as a need across Canadian postsecondary institutions, especially small ones. Interestingly, most respondents did not think that current promotion or outreach programs were a good use of, presumably, scarce resources. This may reflect the view that existing programs need improvement, as most respondents indicated that they should be expanded.

Mental health is closely tied to overall well-being, and services that reduce stress and encourage self-care reflect this.32 Most institutions offer some form of social support to vulnerable groups, as well as programs that facilitate campus community involvement, and contribute to a healthy campus climate. Student-to-student or peer health educator programs have been shown to extend the reach of health (including mental health/well-being) services.33 Such programs involve training students on how to identify those in distress and what services exist for such individuals.33 Only a minority of institutions offer peer health educator training, despite evidence that students who come into contact with peer educators are likely to consume less alcohol and have fewer alcohol-related negative consequences and unhealthy behaviours.34 Implemented peer support initiatives, such as the Student Support Network (SSN) at the Worcester Polytechnic Institute in the United States, have been promising. The SSN is an initiative that educates student leaders on mental health campus resources and on reducing stigma associated with seeking help. Since its inception, a substantial increase in counselling centre consultations with “students of concern” (and with the student population in general) has been noted. While this may strain services initially, it may mitigate more serious mental health issues in the long term (and, likely, more costly strains on counselling services).33 As such, it is worth considering whether adopting peer health educator programs should be encouraged more broadly across Canada.

Most institutions do not employ methods for actively identifying students in distress, and few smaller institutions have gatekeeper training initiatives. This raises the possibility that these schools may have less comprehensive or effective programs for training students/staff. While the identification of those in distress is important, ensuring that such students are able to access appropriate services is paramount. A recent study found that increased identification (by RA gatekeepers) does not necessarily lead to increased MHS utilization on campus.27 Thus, further initiatives aimed at facilitating the use of campus MHSs may be needed.

A key recommendation from a Canadian student alliance was that institutions must develop mechanisms to allow incoming students opportunities to self-identify as needing additional support.35 Given that a large proportion of institutions do not have or do not know if they have procedures on how incoming students can alert schools regarding mental health issues, adopting and clarifying such procedures may be worthwhile. Early alert programs aimed at identifying underperforming first-year students, contacting them, and directing them to appropriate support programs36 may also be useful in minimizing distress and psychiatric issues.37

Most institutions have some form of an on-campus counselling centre/services, consistent with the increasing demand for such services at postsecondary institutions.38 Among the small institutions that have counselling centres/services, relatively few employ a triage system for students needing urgent care. Admittedly, small schools are more likely to face specific barriers with adopting a triage system (e.g., preparing for increased client flow with limited staff).39 However, the presence of such a system allows counselling centres to utilize the brief window of opportunity, during which time a distressed student is willing to access care. Further, employing nontraditional triage systems involving educators, ministers, or Aboriginal advisors, particularly at small institutions, should be considered.

Complete diagnostic assessments tend not to be available, and the use of standardized diagnostic tools is rare across postsecondary institutions. More consistent use of such assessments and tools may assist campus personnel in guiding students to appropriate resources (e.g., further counselling, support services, etc.).19

Some research suggests that culturally adapted mental health interventions (e.g., in clients’ native language) are more effective than nonadapted ones.40 However, few respondents indicated that counselling services staff is composed of individuals from diverse backgrounds. As such, a policy regarding staff diversity may be beneficial. For instance, Canadian institutions in northern communities with higher Aboriginal student populations may benefit from hiring Aboriginal advisors.41 Further, “e-health interventions,” linking minority students with specialized providers, should also be considered.42 Finally, peer counsellors or incorporating self/group components in counselling sessions were seldom reported in smaller institutions. Such approaches could reduce the stress on limited resources, particularly at smaller schools, although further research on their effectiveness is needed.43

Consistent with concerns that campus MHSs are focused on short-term therapy,44 long-term therapy is generally not provided. Off-site referral may be associated with an extra financial burden, which may be particularly problematic for students with limited incomes/insurance.10 Formal follow-up procedures for those requiring long-term (generally off-campus) therapy are lacking. Having a formal policy is important, as data suggest that a large proportion of off-site referrals are unsuccessful.45 Washburn and Mandrusiak30 suggested that regularly updating lists regarding available community practitioners and offering formal campus follow-ups for clients through the transition may be useful.

One limitation of the current study is that the accuracy of each institution’s profile was limited by the personal knowledge of respondents. However, the awareness of available services by campus personnel may be as functionally important as “on-paper” services. Despite assurances of anonymity, social desirability may have also influenced the responses. Additionally, although the survey was comprehensive, it was not all-encompassing. We did not explore the ways in which schools are addressing social media and other technologies relevant to students’ well-being. Further, we did not focus on detailed assessments of suicide-specific programs, nor did we thoroughly assess the length and types of available on-campus interventions (and who provides them).

Conclusions

To date, systematic evaluations of mental health campus initiatives are absent or unreported. Until postsecondary institutions identify performance indicators, measure the impact of initiatives/services, and publicly disseminate this information, our understanding of whether an institution is doing well in supporting mental health is limited. This survey describes what is currently available on campuses of various sizes; the data may provide a reference for schools that are reviewing their own MHSs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the Michael J. Goodfellow Memorial Fund of The Calgary Foundation. The foundation had no influence on the study or the contents of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material: The online supplements are available at http://cpa.sagepub.com/supplemental.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. The world health report 2002: reducing risks, promoting healthy life. 2002. [accessed August 10, 2015]. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/2002/en/%3E. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2. Osborn D, Levy G, Nazareth I, King M. Suicide and severe mental illnesses: cohort study within the UK general practice research database. Schizophr Res. 2008;99(1–3):134–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cash SJ, Bridge JA. Epidemiology of youth suicide and suicidal behavior. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21(5):613–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Navaneelan T. Suicide rates: an overview. Catalogue no. 82-624-X. Statistics Canada; 2012. [accessed August 10, 2015]. Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-624-x/2012001/article/11696-eng.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wasserman D, Cheng Q, Jiang G-X. Global suicide rates among young people aged 15-19. World Psychiatry. 2005;4(2):114–120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Delaney L, Smith JP. Childhood health: trends and consequences over the life course. Future Child. 2012;22(1):43–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. American College Health Association. ACHA–National College Health Assessment. 2000. –2014. [accessed August 10, 2015]. Available from: http://www.acha-ncha.org/reports_ACHA-NCHAII.html.

- 8. Eisenberg D, Hunt J, Speer N. Mental health in American colleges and universities: variation across student subgroups and across campuses. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013;201(1):60–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ontario College Health Association. Towards a comprehensive mental health strategy: the crucial role of colleges and universities as partners. 2009. [accessed August 10, 2015]. Available from: http://www.oucha.ca/pdf/mental_health/2009_12_OUCHA_Mental_Health_Report.pdf.

- 10. Blanco C, Okuda M, Wright C, et al. Mental health of college students and their non-college-attending peers: results from the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(12):1429–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gall TL, Evans DR, Bellerose S. Transition to first-year university: patterns of change in adjustment across life domains and time. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2000;19(4):544–567. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hussain R, Guppy M, Robertson S, Temple E. Physical and mental health perspectives of first year undergraduate rural university students. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wolgast BM, Rader J, Roche D, Thompson CP, von Zuben FC, Goldberg A. Investigation of clinically significant change by severity level in college counseling center clients. J College Counseling. 2005;8(2):140–152. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Crozier S, Willihnganz N. Canadian Counselling Centre Survey. Victoria: Camosun College; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gallagher RP. National Survey of Counseling Center Directors. Alexandria (VA): International Association of Counseling Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rudd MD. University counseling centers: looking more and more like community clinics. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2003;35(3):316–317. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sharkin BS. Assessing changes in categories but not severity of counseling center clients’ problems across 13 years: comment on Benton, Robertson, Tseng, Newton, and Benton (2003). Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2003;35(3):313–315. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hunt J, Eisenberg D. Mental health problems and help-seeking behavior among college students. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(1):3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mowbray CT, Megivern D, Mandiberg JM, et al. Campus MHS: recommendations for change. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76(2):226–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Canadian Association of Colleges and University Student Services, Canadian Mental Health Association. Post-secondary student mental health: guide to a systemic approach. Vancouver: Canadian Association of Colleges and University Student Services, Canadian Mental Health Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mori S. Addressing the mental health concerns of international students. J Counsel Dev. 2000;78(2):137–144. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Principal’s Commission on Mental Health. Student mental health and wellness: framework and recommendations for a comprehensive strategy. Kingston: Queen’s University; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Salzer M, Wick L, Rogers J. Familiarity with and use of accommodations and supports among postsecondary students with mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(4):370–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yorgason J, Linville D, Zitzman B. Mental health among college students: do those who need services know about and use them? J Am Coll Health. 2008;57(2):173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Golberstein E, Eisenberg D, Gollust SE. Perceived stigma and mental health care seeking. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(4):392–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Eisenberg D, Downs MF, Golberstein E, Zivin K. Stigma and help seeking for mental health among college students. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(5):522–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lipson SK, Speer N, Brunwasser S, Hahn E, Eisenberg D. Gatekeeper training and access to mental health care at universities and colleges. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(5):612–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Heck E, Jaworska N, DeSomma E, et al. A survey of MHS at post-secondary institutions in Alberta. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(5):250–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Burns KE, Duffett M, Kho ME, et al. A guide for the design and conduct of self-administered surveys of clinicians. CMAJ. 2008;179(3):245–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Washburn CA, Mandrusiak M. Campus suicide prevention and intervention: putting best practice policy into action. Can J Higher Education. 2010;40(1):101–119. [Google Scholar]

- 31. mtvU. mtvU AP 2009 Economy, College Stress and Mental Health Poll. 2009. [accessed August 10, 2015]. Available from: http://www.halfofus.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/mtvU-AP-2009-Economy-College-Stress-and-Mental-Health-Poll-Executive-Summary-May-2009.pdf.

- 32. The Jed Foundation and Clinton Foundation. The Jed and Clinton Foundation Health Matters Campus Program. Campus program framework: criteria for developing a healthier school environment; 2014. [accessed August 10, 2015]. Available from: http://www.thecampusprogram.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kirsch DJ, Pinder-Amaker SL, Morse C, Ellison ML, Doerfler LA, Riba MB. Population-based initiatives in college mental health: students helping students to overcome obstacles. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(12):525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. White S, Park YS, Israel T, Cordero ED. Longitudinal evaluation of peer health education on a college campus: impact on health behaviors. J Am Coll Health. 2009;57(5):497–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Popovic TP. Mental health in Ontario’s post-secondary education system: policy paper. Toronto: The College Student Alliance; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tampke DR. Developing, implementing and assessing an early alert system. J Coll Stud Ret. 2013;14(4):523–532. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Campbell S, Nutt C. The role of academic advising in student retention and persistence. Manhattan (KS): National Academic Advising Association; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Watkins DC, Hunt JB, Eisenberg D. Increased demand for MHS on college campuses: perspectives from administrators. Qualitative Social Work. 2012;11(3):319–337. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rockland-Miller HS, Eells GT. The implementation of mental health clinical triage systems in university health services. J College Stud Psychother. 2006;20(4):39–51. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Griner D, Smith TB. Culturally adapted mental health intervention: a meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2006;43(4):531–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Statistics Canada. Aboriginal identity population by age groups, median age and sex, percentage distribution for both sexes, for Canada, provinces and territories: 20% sample data [cited 2015 Dec 7]. 2006. Available from: http://www12.statcan.ca/census-recensement/2006/dp-pd/hlt/97-558/pages/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo=PR&Code=01&Table=1&Data=Dist&Sex=1&Age=1&StartRec=1&Sort=2&Display=Page%3E.

- 42. Reavley N, Jorm AF. Prevention and early intervention to improve mental health in higher education students: a review. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2010;4(2):132–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Webel AR, Okonsky J, Trompeta J, Holzemer WL. A systematic review of the effectiveness of peer-based interventions on health-related behaviors in adults. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(2):247–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Stone GL, Vespia KM, Kanz JE. How good is mental health care oncollege campuses? J Counsel Psychol. 2000;47(4):498–510. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Owen J, Devdas L, Rodolfa E. University counselling center off-campus referrals: an exploratory investigation. J College Stud Psychother. 2007;22(2):13–29. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.