Abstract

Objective:

To describe trends in psychological health symptoms in Canadian youth from 2002 to 2014 and examine gender and socioeconomic differences in these trends.

Method:

We used data from the Canadian Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study. We assessed psychological symptoms from a validated symptom checklist and calculated a symptom score (range, 0-16). We stratified our analyses by gender and affluence tertile based on an index of material assets. We then plotted trends in symptom score and calculated the probability of experiencing specific symptoms over time.

Results:

Between 2002 and 2014, psychological symptom score increased by 1.01 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.73 to 1.41), 1.08 (95% CI, 0.79 to 1.37), and 0.84 (95% CI, 0.55 to 1.13) points in girls in the low-, middle-, and high-affluence tertiles, respectively. In boys, psychological symptoms decreased by –0.39 (95% CI, –0.66 to –0.12) and –0.12 (95% CI, –0.43 to 0.19) points in the high- and middle-affluence tertiles, respectively, and increased by 0.30 (95% CI, –0.04 to 0.63) points in the low-affluence tertile. The probability of feeling anxious and having sleep problems at least once a week notably increased in girls from all affluence groups, while the probability of feeling depressed and irritable decreased among boys from the high-affluence tertile.

Conclusion:

Psychological symptoms increased in Canadian adolescent girls across all affluence groups while they remained stable in boys from low and middle affluence and decreased in boys from high affluence. Specific psychological symptoms followed distinct trends. Further research is needed to uncover the mechanisms driving these trends.

Keywords: adolescence, child and adolescent psychiatry, trends, social class, socioeconomic factors

Abstract

Objectif:

Décrire les tendances des symptômes de santé psychologique chez les adolescents canadiens de 2002 à 2014 et examiner les différences socioéconomiques et selon le sexe de ces tendances.

Méthode:

Nous avons utilisé les données de l’Enquête sur les comportements liés à la santé chez les jeunes d’âge scolaire (Enquête HBSC). Nous avons évalué les symptômes psychologiques d’après une liste validée de vérification des symptômes et nous avons calculé un score des symptômes (échelle de 0 à 16). Nous avons stratifié nos analyses selon le sexe et le tertile d’affluence basé sur un indice des actifs matériels. Nous avons ensuite inscrit le score des symptômes des tendances et calculé la probabilité de subir des symptômes spécifiques avec le temps.

Résultats:

Entre 2002 et 2014, le score des symptômes psychologiques a augmenté de 1,01 (IC à 95% 0,73 à 1,41), 1,08 (IC à 95% 0,79 à 1,37) et 0,84 (IC à 95% 0,55 à 1,13) points chez les filles des tertiles d’affluence inférieur, moyen et supérieur, respectivement. Chez les garçons, les symptômes psychologiques ont diminué de –0,39 (IC à 95% –0,66 à –0,12) et de –0,12 (IC à 95% –0,43 à 0,19) points dans les tertiles d’affluence supérieur et moyen, respectivement, et augmenté de 0,30 (IC à 95% –0,04 à 0,63) point dans le tertile d’affluence inférieur. La probabilité de ressentir de l’anxiété et d’avoir des problèmes de sommeil au moins une fois par semaine s’est accrue notablement chez les filles de tous les groupes d’affluence, tandis que la probabilité de se sentir déprimé et irritable a diminué chez les garçons du tertile d’affluence supérieur.

Conclusion:

Les symptômes psychologiques ont augmenté chez les adolescentes canadiennes de tous les groupes d’affluence alors qu’ils sont demeurés stables chez les garçons d’affluence inférieure et moyenne et qu’ils ont diminué chez les garçons d’affluence supérieure. Les symptômes psychologiques spécifiques suivaient des tendances distinctes. Il faut plus de recherche pour découvrir les mécanismes qui agissent sur ces tendances.

In the past decade, youth mental health emerged as a public health priority in Canada. In 2008, the Canadian government established the Child and Youth Advisory Committee of the Mental Health Commission,1 and in 2010, the committee published the Evergreen Framework2 to inform governments, stakeholders, and the general public in the development of local policy frameworks for youth mental health.3 Since these initiatives, however, information on the progression of youth mental health in Canada has been limited. Previous research has tracked symptoms of adolescent mental health prior to 2010 and found little change since 1994.4,5 However, inequalities between gender groups and socioeconomic classes may underlie mental health trends. Symptoms of common mental disorders, such as mood and anxiety disorders, are more prevalent among girls than boys,6,7 and the gap may be growing.8,9 Increasing social pressure placed on girls at school and in their personal lives is thought to be a key factor.8 In recent years, several studies from high-income countries have found an increase in psychological symptoms among girls but no change or a decrease among boys.8,9 Socioeconomically deprived adolescents are also more at risk of experiencing psychological symptoms.10 As income inequality rises in Canada,11 socioeconomic inequality in youth mental health may also be rising, concurrently with international trends.12 Our study extends previous research on youth mental health trends in Canada by including the most recent generation of adolescents and investigating gender and socioeconomic differences in trends over time. We examined data on psychological symptoms in a representative sample of Canadian adolescents between 2002 and 2014. Updated information on trends in youth psychological symptoms may help inform current policies and future strategies. The identification of vulnerable subgroups could further help target efforts.

Methods

Data Sources

The study used data from the 2002, 2006, 2010, and 2014 waves of the Canadian Health Behaviors in School-aged Children (HBSC) study (www.hbsc.org), a nationally representative cross-sectional survey of adolescents in grades 6 to 10 from all provinces and territories in Canada. For each of the 4 waves, a 2-stage cluster approach was used to select a sample of students by grade and school representative of school population characteristics such as religion, community size, school size, and language of instruction. Private schools, special needs schools, and schools for youth in custody were excluded, in line with an HBSC international protocol used in 45 countries. Further details on the sampling methodology can be found elsewhere.13 Teachers or trained interviewers distributed the questionnaires in classroom settings. The HBSC protocol stipulated a standard questionnaire format, item order, and testing conditions. The questionnaire items used in this analysis were consistent across the 4 survey waves. We included all participants from the 2002 (n = 7235), 2006 (n = 9717), 2010 (n = 26,078), and 2014 (n = 30,117) surveys, resulting in a total sample of 73,147 participants between 10 and 19 years old.

Measures

The HBSC mandatory questionnaire included an 8-item symptom checklist that asks students to report the frequency of physical and psychological symptoms experienced in the past 6 months. A copy of the questionnaire is available online.14 We used the 4-item psychological subscale of the checklist to measure psychological symptoms, a validated and reliable tool to measure youth psychological health.15,16 The items of the subscale focus on internalizing (emotional) problems, including feeling low or depressed, feeling irritable or bad tempered, feeling nervous, and sleeping difficulties. Students rated the frequency of each symptom on a 5-point scale from 0 (rarely or never) to 4 (about every day). The HBSC psychological subscale was designed as a surveillance tool and has been successfully used in several surveys.12,17 It was validated in a Canadian sample of adolescents as a measure of psychological health and demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.78) and convergent validity with indicators for emotional problems (r = –0.79) and emotional well-being (r = 0.48).15 We used the sum score of the scale (range, 0-16) as a global assessment of emotional health.

The HBSC Family Affluence Scale (FAS) was used to measure socioeconomic position. The FAS is an index of material assets that asks about 4 common indicators of family wealth (number of cars, computers, whether the child has his or her own bedroom, and how often the family travels on holidays). The scale has been used in numerous studies that focus on the relationship between socioeconomic status and adolescent health and has better criterion validity and less susceptibility to nonresponse bias than adolescents’ reports of household income or parental occupation or education level.18 For each survey wave, the FAS was categorized into approximate tertiles based on proportional ranks within grade and gender groups (low, medium, high) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of Family Affluence Scale by Year and Gender in the Canada Health Behaviour in School-aged Children 2002-2014 Surveys.

| 2002, n (%) | 2006, n (%) | 2010, n (%) | 2014, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls | ||||

| Family affluence scale | ||||

| Low | 1094 (29.5) | 1367 (27.5) | 3750 (32.2) | 4413 (29.3) |

| Medium | 1354 (36.5) | 1826 (36.8) | 4552 (37.0) | 4741 (33.8) |

| High | 1264 (34.1) | 1772 (35.7) | 3996 (30.8) | 4659 (36.9) |

| Boys | ||||

| Family affluence scale | ||||

| Low | 1089 (34.5) | 1721 (39.5) | 3853 (34.9) | 4195 (29.1) |

| Medium | 933 (29.6) | 1293 (29.6) | 3373 (30.0) | 4170 (31.0) |

| High | 1135 (36.0) | 1348 (30.9) | 4180 (35.0) | 4562 (39.9) |

Prevalence was weighted using survey weights.

Statistical Analysis

We used a linear regression to examine the association between gender and affluence with psychological symptoms, adjusted for age and year of survey. We included interaction terms between gender, affluence, and year of survey in the model, allowing the association between gender and symptoms to vary by affluence and year, as well as the association between affluence and symptoms to vary by gender and year. We conducted similar analyses using logistic regressions for each of the 4 symptoms (feeling low or depressed, feeling irritable or bad tempered, feeling nervous, sleep difficulties), modeling the log odds of experiencing each symptom once a week or more compared to once a month or never/rarely. We estimated the predicted scores (from the linear models) and predicted probabilities (from the logistic models) for each gender-affluence category by survey year using the margins commands in Stata 14 and calculated the 12-year differences in symptom score and probability from the regression output. Statistical analyses were conducted in Stata (version 14.1; Stata Corp, College Station, TX). All analyses accounted for clustering at the school level and incorporated sampling weights to ensure results were representative of public school students in Canada.

Results

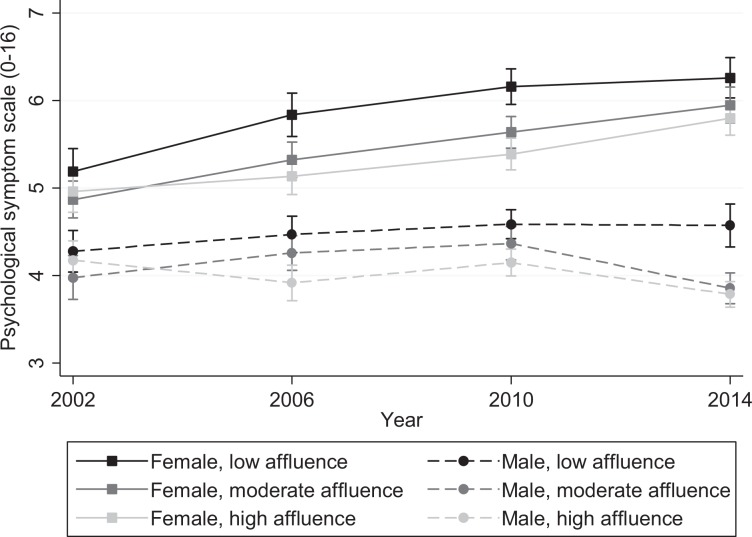

The distribution of affluence groups was similar between boys and girls across the survey years (Table 1). As shown in Figure 1, there was an increase in psychological symptoms among girls from 2002 to 2014. Psychological symptom scores increased by 1.01 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.73 to 1.41), 1.08 (95% CI, 0.79 to 1.37), and 0.84 (95% CI, 0.55 to 1.13) points among girls in the low-, middle-, and high-affluence groups, respectively (Supplementary File 1). Conversely, psychological symptoms score decreased by 0.39 (95% CI, 0.12 to 0.66) among boys in the high-affluence group during the same time period, while they remained statistically stable for others, although estimates and confidence intervals suggest a small decrease in middle-affluence boys (–0.12; 95% CI, –0.43 to 0.19) and an increase in low-affluence boys (0.30; 95% CI, –0.04 to 0.63) (Supplementary File 1). There was no evidence of an interaction between gender and affluence in the model (P > 0.05; Supplementary File 2), suggesting that each factor associated with trends independently from each other. Estimates from the linear regression model are available in Supplementary File 2.

Figure 1.

Time trends in psychological symptoms by gender and family affluence scale, Canada 2002 to 2014. Predicted psychological symptom score estimated from a linear regression model adjusted for gender, family affluence, year of survey, age of adolescent, and all 2-way and 3-way interaction terms between gender, family affluence, and year of survey and weighted using survey weights.

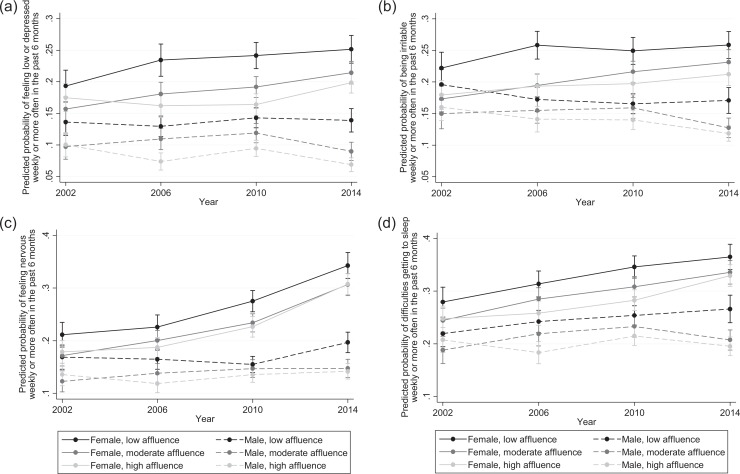

As illustrated in Figure 2, trends in psychological symptoms varied by specific symptoms, gender, and affluence. The probability of feeling nervous and having sleep problems once a week or more significantly increased among girls across all affluence groups, as did the probability of feeling depressed and irritable once a week or more, particularly among girls from the low- and middle-affluence groups (Supplementary File 3). Conversely, the probability of feeling depressed, irritable, nervous, or having sleep problems once a week or more did not increase among boys, except for sleep problems, which increased among boys from the low-affluence group. The probability of feeling depressed or irritable decreased among boys from the high-affluence group (Supplementary File 3).

Figure 2.

Time trends of specific psychological symptoms (depressed, irritable, nervous, sleep difficulties) every week or more in the past 6 months by gender and family affluence scale. Predicted probability of reporting each symptom estimated from a logistic regression model adjusted for gender, family affluence, year of survey, age of adolescent, and all 2-way and 3-way interaction terms between gender, family affluence, and year of survey and weighted using survey weights. (a) Average predicted probabilities of feeling low or depressed once a week or more in the past 6 months. (b) Average predicted probabilities of being irritable or bad tempered once a week or more in the past 6 months. (c) Average predicted probabilities of feeling nervous once a week or more in the past 6 months. (d) Average predicted probabilities of having difficulties in getting to sleep once a week or more in the past 6 months.

Discussion

This study examined trends in psychological symptoms between 2002 and 2014 in a representative sample of Canadian adolescents. Our results show a rise in psychological symptoms among girls and no significant change or a decline among boys, especially boys from high-affluence families. Specific psychological symptoms followed distinct time trends, with a notable increase in the probability of feeling nervous and having sleep difficulties once a week or more among girls, regardless of their family affluence, and a decrease in the probability of feeling depressed and irritable among boys from high-affluence families. These findings mirror trends from other countries that found an increase in psychological symptoms among adolescent girls.8,9 Our study provides an update to earlier Canadian data that showed a flat trend in adolescent psychological symptoms prior to 20104,5 and further clarifies the role of gender and socioeconomic factors in current trends. We did not find an interaction between gender and family affluence in this study, suggesting that both factors are important but separate issues in the progression of youth mental health.

Psychological symptoms increased among adolescent girls in our sample, similar to other high-income countries.8,9 The forces driving this trend are not yet fully understood. Exposure to social media, online content, and digital technology has rapidly increased in the past decade, and a growing body of evidence suggests that this new media consumption has led to an escalating cultural emphasis on female image and appearance, earlier and greater female sexualisation, and problems with body dissatisfaction and shame among adolescent girls19,20 that may in turn harm their mental health.21–23 Girls are also more vulnerable to online sexual harassment24 and are more likely to be victims of cyberbullying than boys.25 Moreover, evidence suggests that girls are affected by the rise in school pressure more than boys.26

Trends in psychological health symptoms differed by socioeconomic class, notably among boys, in whom improvement was significant only in those from high affluence. On a societal level, research found that socioeconomic differences in adolescent mental health have increased in tandem with income inequality,12 which was relatively stable in Canada between 2002 and 2010 but increased during the life span of these youth.11 Rising income inequality might have cumulative effects on adolescent mental health as it appears to have affected adults.27 The Canadian Institute for Health Information reported similar trends in income differences in adult self-rated mental health, which increased from 2002 to 2013 due to worsening mental health in the bottom income quintile.27

The study draws strengths from a large representative samples of adolescents. Some limitations should be considered. The psychological symptom scale only asked about 4 common symptoms and did not assess mental illness or disability. The items measured symptoms of internalizing (emotional) problems and not externalizing (behavioral) disorders. Further research using a more comprehensive tool is recommended. For instance, symptoms of externalizing disorders, such as aggression and noncompliance, are more common in boys6 and may present gender trends over time that differ from the trends reported here. The items on the FAS were sensitive to response drift over time.28 Although our use of relative affluence groups partly overcomes this limitation, the composition of the affluence tertiles may nonetheless differ over time. Furthermore, the data were drawn from Canadian adolescents attending public schools, and results may not be generalizable to adolescents from other countries or other schools, such as special needs schools or schools for youth in custody.

This study finds an increase in psychological symptoms among adolescent girls over the past decade and little change or a decrease among adolescent boys in Canada. Our results lend support to the work of the Child and Youth Advisory Committee of the Mental Health Commission of Canada1 that encourages initiatives to improve mental health among all Canadian adolescents. Our results further suggest that policies and interventions that specifically target adolescent girls and low socioeconomic groups are needed. Monitoring trends in youth mental health is one way to evaluate and inform current mental health policies, programs, and services aimed at Canadian youth. It can help identify vulnerable subgroups of adolescents who are worsening over time or lagging behind compared to others. Further research on the mechanisms driving these trends is needed, and continued monitoring of mental health among adolescents in Canada is recommended.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material: The online data supplements are available at http://cpa.sagepub.com/supplemental

References

- 1. Former Child and Youth Advisory Committee Calgary. AB Mental Health Commission of Canada [Online]. 2016. [cited 2016 March 29. Available from: http://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/English/former-advisory-committee/former-child-and-youth-advisory-committee

- 2. Kutcher S, McLuckie A, for the Child and Youth Advisory Committee Mental Health Commission of Canada. Evergreen: a child and youth mental health framework for Canada. Calgary (AB): Mental Health Commission of Canada; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mulvale G, Kutcher S, Randall G, et al. Do national frameworks help in local policy development? Lessons from Yukon about the Evergreen Child and Youth Mental Health Framework. Can J Community Mental Health. 2015;34(4):111–128. [Google Scholar]

- 4. McMartin SE, Kingsbury M, Dykxhoorn J, et al. Time trends in symptoms of mental illness in children and adolescents in Canada. Can Med Assoc J. 2014;186(18):E672–E678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reid M-A, Freeman JG, Coe H, et al. Mental health. In: Health behaviour in school-aged children: trends report 1990-2010. Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; 2014. pp. 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Merikangas KR, Nakamura EF, Kessler RC. Epidemiology of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Dialog Clin Neurosci. 2009;11(1):7–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zahn-Waxler C, Shirtcliff EA, Marceau K. Disorders of childhood and adolescence: gender and psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:275–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bor W, Dean AJ, Najman J, et al. Are child and adolescent mental health problems increasing in the 21st century? A systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2014;48(7):606–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fink E, Patalay P, Sharpe H, et al. Mental health difficulties in early adolescence: a comparison of two cross-sectional studies in England from 2009 to 2014. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(5):502–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Reiss F. Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2013;90:24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Conference Board of Canada. World income inequality: is the world becoming more unequal [Online]? Ottawa (ON): The Conference Board of Canada; 2013. [cited 2016 July 27]. Available from: http://www.conferenceboard.ca/hcp/hot-topics/worldinequality.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 12. Elgar FJ, Pförtner T-K, Moor I, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in adolescent health 2002-2010: a time-series analysis of 34 countries participating in the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study. Lancet. 2015;385(9982):2088–2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. King M. Introduction. In: Health behaviour in school-aged children: trends report 1990-2010 [Online]. Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; 2014. [cited 2016 July 27]. Available from: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/hp-ps/dca-dea/prog-ini/school-scolaire/behaviour-comportements/trends-tendances-eng.php#a1.0 [Google Scholar]

- 14. HBSC International Coordinating Centre. HBSC 2005/06 Survey: International Standard Mandatory Questionnaire St-Andrews, United Kingdom 2006 [Online] [cited 2016 July 27]. Available from: http://filer.uib.no/psyfa/HEMIL-senteret/HBSC/2006_Mandatory_Questionnaire.pdf

- 15. Gariepy G, McKinnon B, Sentenac M, et al. Validity and reliability of a brief symptom checklist to measure psychological health in school-aged children. Child Indicators Research. 2016;9(2):471–484. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Haugland S, Wold B. Subjective health complaints in adolescence—reliability and validity of survey methods. J Adolesc. 2001;24(5):611–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Levin KA, Currie C, Muldoon J. Mental well-being and subjective health of 11- to 15-year-old boys and girls in Scotland, 1994-2006. Eur J Public Health. 2009;19(6):605–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Currie C, Molcho M, Boyce W, et al. Researching health inequalities in adolescents: the development of the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) Family Affluence Scale. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(6):1429–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. American Psychological Association. Report of the APA Task Force on the sexualization of girls. Washington (DC): American Psychological Association; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20. McKenney SJ, Bigler RS. Internalized sexualization and its relation to sexualized appearance, body surveillance, and body shame among early adolescent girls. J Early Adolesc. 2016;36(2):171–197. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nesi J, Prinstein MJ. Using social media for social comparison and feedback-seeking: gender and popularity moderate associations with depressive symptoms. J Abnormal Child Psychol. 2015;43(8):1427–1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lin Ly, Sidani JE, Shensa A, et al. Association between social media use and depression among U.S. young adults. Depression Anxiety. 2016;33(4):323–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stefanone MA, Lackaff D, Rosen D. Contingencies of self-worth and social-networking-site behavior. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Network. 2011;14(1-2):41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cooper K, Quayle E, Jonsson L, et al. Adolescents and self-taken sexual images: a review of the literature. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;55(Pt B):706–716. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hamm MP, Newton AS, Chisholm A, et al. Prevalence and effect of cyberbullying on children and young people: a scoping review of social media studies. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(8):770–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moksnes UK, Eilertsen MEB, Lazarewicz M. The association between stress, self-esteem and depressive symptoms in adolescents. Scand J Psychol. 2016;57(1):22–29. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Trends in income-related health inequalities in Canada. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schnohr CW, Makransky G, Kreiner S, et al. Item response drift in the Family Affluence Scale: a study on three consecutive surveys of the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) survey. Measurement. 2013;46(9):3119–3126. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.