Abstract

This protocol illustrates the production of 64Cu and the chelator conjugation/radiolabeling of a monoclonal antibody (mAb) followed by murine lymphocyte cell culture and 64Cu-antibody receptor targeting of the cells. In vitro evaluation of the radiolabel and non-invasive in vivo cell tracking in an animal model of an airway delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction (DTHR) by PET/CT are described.

In detail, the conjugation of a mAb with the chelator 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid (DOTA) is shown. Following the production of radioactive 64Cu, radiolabeling of the DOTA-conjugated mAb is described. Next, the expansion of chicken ovalbumin (cOVA)-specific CD4+ interferon (IFN)-γ-producing T helper cells (cOVA-TH1) and the subsequent radiolabeling of the cOVA-TH1 cells are depicted. Various in vitro techniques are presented to evaluate the effects of 64Cu-radiolabeling on the cells, such as the determination of cell viability by trypan blue exclusion, the staining for apoptosis with Annexin V for flow cytometry, and the assessment of functionality by IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Furthermore, the determination of the radioactive uptake into the cells and the labeling stability are described in detail. This protocol further describes how to perform cell tracking studies in an animal model for an airway DTHR and, therefore, the induction of cOVA-induced acute airway DHTR in BALB/c mice is included. Finally, a robust PET/CT workflow including image acquisition, reconstruction, and analysis is presented.

The 64Cu-antibody receptor targeting approach with subsequent receptor internalization provides high specificity and stability, reduced cellular toxicity, and low efflux rates compared to common PET-tracers for cell labeling, e.g.64Cu-pyruvaldehyde bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) (64Cu-PTSM). Finally, our approach enables non-invasive in vivo cell tracking by PET/CT with an optimal signal-to-background ratio for 48 h. This experimental approach can be transferred to different animal models and cell types with membrane-bound receptors that are internalized.

Keywords: Immunology, Issue 122, Small animal imaging, cell labeling, non-invasive in vivo cell tracking, PET/CT, TH1 T cells, airway delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction

Introduction

Non-invasive cell tracking is a versatile tool to monitor cell function, migration and homing in vivo. Recent cell tracking studies have focused on mesenchymal1,2 or bone-marrow derived stem cells3 in the context of regenerative medicine, autologous peripheral white blood cells in inflammation or T lymphocytes in adoptive cell therapies against cancer3,4. The elucidation of the sites of action and the underlying biological principles of cell-based therapies is of tremendous importance. CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes, genetically engineered chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells or tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) were widely considered as the gold standard. However, tumor-associated antigen-specific TH1 cells have proven to be an effective alternative treatment option4,5,6,7.

As key players in inflammation, organ-specific autoimmune diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis or bronchial asthma), and cells of high interest in cancer immunotherapy, it is important to characterize the temporal distribution and homing patterns of TH1 cells. Noninvasive in vivo imaging by PET presents a quantitative, highly sensitive method8 to examine cell migration patterns, in vivo homing, and the sites of T cell action and responses during inflammation, allergies, infections or tumor rejection9,10,11.

Clinically, 111In-oxine is used for leukocyte scintigraphy for the discrimination of inflammation and infection12, while 2-deoxy-2-(18F)fluoro-D-glucose (18F-FDG) is commonly used for cell tracking studies by PET3,13. One major disadvantage of this PET tracer, however, is the short half-life of the radionuclide 18F at 109.7 min and the low intracellular stability that impedes imaging at later time points post adoptive cell transfer. For longer term in vivo cell tracking studies by PET, although unstable in the cells, 64Cu-PTSM is frequently used to nonspecifically label cells14,15 with minimized detrimental effects on T cell viability and function16.

This protocol describes a method to further reduce disadvantageous effects on cell viability and function using a T cell receptor (TCR)-specific radiolabeled mAb. First, the production of the radioisotope 64Cu, the conjugation of the mAb KJ1-26 with the chelator DOTA, and the subsequent 64Cu-radiolabeling are shown. In a second step, the isolation and expansion of cOVA-TH1 cells of DO11.10 donor mice and the radiolabeling with 64Cu-loaded DOTA-conjugated mAb KJ1-26 (64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26) are described in detail. The assessment of uptake values and efflux of radioactivity with a dose calibrator and by γ-counting, respectively, as well as the evaluation of the effects of 64Cu-radiolabeling on cell viability by trypan blue exclusion and functionality with IFN-γ ELISA are presented. For non-invasive in vivo cell tracking, the elicitation of a mouse model of cOVA-induced acute airway DTHR and image acquisition by PET/CT after adoptive cell transfer are described.

Moreover, this labeling approach can be transferred to different disease models, murine T cells with different TCRs or general cells of interest with membrane-bound receptors or expression markers underlying continuous membrane shuttling17.

Protocol

Safety Precautions: When handling radioactivity, store 64Cu behind 2-inch-thick lead bricks and use respective shielding for all vessels carrying activity. Use appropriate tools to indirectly handle unshielded sources to avoid direct hand contact and minimize exposure to radioactive material. Always wear radiation dosimetry monitoring badges and personal protection equipment and check oneself and the working area for contamination to immediately address it. Discard potentially contaminated personal protection equipment prior to leaving the area where radioactive material is used. Store the entire radioactive waste behind lead shielding until the radioactive 64Cu is decayed (approximately 10 half-lifes = 127 h) before adequate disposal.

1. 64Cu Production

NOTE: The radioisotope 64Cu is produced via the 64Ni(p,n)64Cu nuclear reaction using a PETtrace cyclotron according to a modified protocol of McCarthy et al.18.

For 64Cu production, irradiate 64Ni, which is electroplated on a platinum/iridium plate (90/10), with 30 µA for 6 h with a proton beam of 12.4 MeV.

Heat the platinum/iridium target to 100 °C in a dedicated polyetheretherketone (PEEK) chamber and incubate in 2 mL of concentrated HCl for 20 min to dissolve 64Cu/64Ni.

Add another 1 mL of concentrated HCl and incubate for 10 min.

Evaporate HCl using a stream of argon and cool the chamber to room temperature.

Flush the chamber with 3 mL of 4% 0.2 M HCl and 96% methanol (v/v) and transfer this solution to an ion exchange column that was pre-conditioned with 4% 0.2 M HCl in methanol for at least 15 min. The flow-through can be used to recycle 64Ni.

Wash the 64Cu retained in the column with 4% 0.2 M HCl in methanol.

Elute 64Cu with 70% 1.3 M HCl/30% isopropanol (v/v) into a collection vial, evaporate the solution in a stream of argon and let the vial cool to room temperature.

Dissolve 64Cu in 140-210 µL of 0.1 M HCl.

2. Antibody Conjugation with DOTA and Subsequent 64 Cu-radiolabeling

NOTE: The chelator DOTA will be linked to functional amino groups of the mAb by N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) ester chemistry and the conjugate will be subsequently radiolabeled with 64Cu19.

Adjust the concentration of the KJ1-26-mAb to 8 mg/mL and diafiltrate 1 mL of mAb solution against 0.1 M Na2HPO4 pH 7.5 treated with 1.2 g/L of a chelating ion exchange resin using a molecular weight cut off (MWCO 30 kDa) centrifugal filter unit. Apply 3 subsequent washing steps with 14 mL of the buffer. After the final washing step, concentrate the solution again to 1 mL. Quantify the antibody concentration by OD280nm measurements.

Prepare a DOTA-NHS solution in ultrapure or PCR-grade water at a concentration of 10 mg/mL immediately before use. Let the vial adjust to room temperature before opening to avoid water condensation, and carefully remove DOTA-NHS using a plastic spatula. Add 216 µL of this DOTA-NHS solution to 8 mg of the diafiltrated KJ1-26-mAb solution, mix thoroughly, and incubate for 24 h at 4 °C on a tumble mixer.

Diafiltrate the DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb against 0.25 M ammonium acetate, pH 7.0, treated with 1.2 g/L of a chelating ion exchange resin, using a molecular weight cut off (MWCO 30 kDa) centrifugal filter unit. Apply 7 washing steps. Concentrate the mAb to a final volume of 1 mL and again measure the protein concentration by OD280nm measurements.

Before radiolabeling, exchange the buffer of the DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb to PBS via size-exclusion chromatography using gel filtration columns. This also removes potential small-molecule impurities.

Prepare 100 MBq 64CuCl2 solution in 10 mM HCl and adjust the pH to 6-7 with 10x PBS. Add 200 µg of DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb. Incubate for 60 min at 37 °C.

For quality control, perform thin layer chromatography with 0.1 M sodium citrate (pH 5) as the mobile phase and analyze by autoradiography. At least 90% of the activity should be bound to the antibody and thus be detected at the starting spot. Unbound activity is chelated by the citrate-based mobile phase and streaks to the solvent front. For a reference, the use of 64CuCl2 is advised.

3. Chicken Ovalbumin-specific TH1 (cOVA-TH1) Cell Isolation and Expansion

NOTE: The culture of TH1 cells is described according to previously published studies16,17.

- Isolate spleens and extraperitoneal lymph nodes (LNs) from DO11.10 mice.

- Sacrifice the mouse according to federal regulations. Disinfect the animal with 70% ethanol and fixate it with adhesive tape for the removal of the spleen and LNs. Make a median incision and separate the skin from the peritoneum by laterally pulling it to each site.

- Locate the cervical, axial, brachial and inguinal LNs. Remove them with blunt forceps and place them in 1% fetal calf serum (FCS)/PBS buffer.

- Open the peritoneum and locate the spleen. Separate the spleen from the pancreas and connective tissue and place it in 1% FCS/PBS buffer. For further guidance, see references20,21.

Mince spleen and LNs through a 40 µm filter into a 50 mL screw cap tube using the plunger of a syringe. Rinse the filter with 10 mL 1% FCS/PBS-buffer.

Centrifuge at 400 x g for 5 min and remove the supernatant. Subsequently, perform lysis of erythrocytes by adding ammonium-chloride-potassium (ACK) lysis buffer (1.5 mL per donor animal) for 5 min at room temperature. Add 8.5 mL 1% FCS/PBS-buffer (per donor animal).

Centrifuge the cells at 400 x g for 5 min and remove the supernatant. Wash the cells in 10 mL 1% FCS/PBS-buffer, centrifuge at 400 x g for 5 min and remove the supernatant.

For magnetic cell separation, resuspend the cells in 1% FCS/PBS-buffer and add CD4+ microbeads. Refer to the manufacturer's instructions for the buffer volume and the amount of CD4+ microbeads to use.

Incubate for 20 min at 4 °C. Then add 1% FCS/PBS-buffer up to 50 mL, centrifuge the cells at 400 x g for 5 min, and remove the supernatant.

Continue with CD4+ T cell isolation using commercial magnetic separation columns and a respective magnet stand according to the manufacturer's protocol. Adjust the eluted CD4+ T cells to a concentration of 106 cells/mL in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium with 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 2.5% Penicillin/Streptomycin, 1% HEPES buffer, 1% MEM amino acids, 1% sodium pyruvate, and 0.2% 2-mercaptoethanol and store them at 4 °C.

Collect the column discharge in a 50 mL screw cap tube to prepare antigen-presenting cells (APCs). Centrifuge the column discharge at 400 x g for 5 min and remove the supernatant.

Add 10 µg/mL anti-CD4 (clone: Gk1.5), 10 µg/mL anti-CD8 (clone: 5367.2) and 10 µg/mL mouse anti-rat–mAb (MAR18.5) and 1.5 mL rabbit complement. Incubate for 45 min at 37 °C.

Centrifuge the cells at 400 x g for 5 min, remove the supernatant and add 3 mL medium. Irradiate the APCs on a γ-ray or x-ray source with 30 Gy in total. Afterwards, adjust the APCs to a concentration of 5 x 106 cells/mL.

Add 100 µL of CD4+ T cells and 100 µL of APCs on a 96-well plate together with 10 µg/mL cOVA 323-339-peptide, 10 µg/mL anti-IL-4-mAb, 0.3 µM CPG1668-oligonucleotides and 5 U/mL IL-2.

Add 50 U/mL IL-2 every second day. After 3 - 4 days, transfer the cells from 96-well plates to 24-well plates. Combine 3-5 wells from the 96-well plate in one well on the 24-well plate. Add 100 U/mL IL-2 containing medium in a 1:1 ratio.

After another 2-3 days, transfer the cells from the 48-well plate to 175 cm2 cell culture flasks (1 x 48-well plate per flask). Fill with medium in a 1:1 ratio. Add 50 U/mL IL-2 every second day.

Split the cells according to cell density and add 50 U/mL IL-2 every second day. In this fashion, culture the cells for another 10 days.

4. cOVA-TH1 Cell Radiolabeling

NOTE: The 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb will be applied to cultured cOVA-TH1 cells to enable intracellular radioactive labeling.

For cOVA-TH1 cell radiolabeling, draw 37 MBq of the radiolabeled 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb in a syringe without dead volume using a dose calibrator. Add 1 mL saline to receive a 37 MBq/mL solution.

Suspend cOVA-TH1 cells in medium at 2 x 106 cells/mL and add 0.5 mL of the cell suspension to each well in a 48-well plate.

Add 20 µL of the freshly prepared 37 MBq/mL 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb solution to each well of the 48-well plate. The final ratio for the labeling is 0.7 MBq per 106 cells in a volume of 520 µL. Incubate at 37 °C and 7.5% CO2 for 30 min.

After incubation, carefully resuspend the cells in each well and transfer the cell suspension from the 48-well plate into a 50 mL screw cap tube. To minimize cell loss, rinse each well with pre-warmed medium.

Centrifuge the cOVA-TH1 cell suspension at 400 x g for 5 min, discard the supernatant, and resuspend the cells in 10 mL prewarmed PBS. Remove an aliquot of the cell suspension for cell counting. Repeat the washing step.

Count viable cOVA-TH1 cells in an appropriate dilution with trypan blue staining.

Adjust the cell concentration to 5 x 107 cells/mL for intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 107 cells in 200 µL PBS.

- Repeat steps 4.3-4.5 to radiolabel the cOVA-TH1 cells with increasing amounts of activity, e.g., 1.4 MBq or 2.1 MBq per 106 cells.

- To radiolabel the cells with 1.4 MBq per 106 cells, use 40 µL of the 37 MBq/mL 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb solution and 60 µL for radiolabeling with 2.1 MBq per 106 cells. Perform the steps 4.3-4.7 with 0.7 MBq, 1.4 MBq and 2.1 MBq 64Cu-PTSM but increase the labeling time to 3 h for comparative investigations17.

- Proceed to step 5 to determine the optimal amount of activity.

5. In Vitro Evaluation of the Effect of the Radiolabel on cOVA-TH1 Cells

NOTE: The characterization of the influences of the radiolabel on the TH1 cells is performed via trypan blue exclusion assay for viability, IFN-γ ELISA for functionality assessment and PE-Annexin V staining for the induction of apoptosis16,17. Determination of the intracellular uptake and the efflux of radioactivity is also described below. As comparison, 64Cu-PTSM-labeled cOVA-TH1 cells can also be used.

- Effect on viability by trypan blue exclusion

- Adjust at least 18 x 106 cOVA-TH1 cells radiolabeled with 0.7 MBq/106 cells, 1.4 MBq/106 cells and 2.1 MBq/106 cells respectively to a concentration of 2 x 106 cells/mL and perform steps 5.1.2-5.1.7 for each activity dose. Use non-radioactive KJ1-26-mAb labeled cOVA-TH1 cells and unlabeled cOVA-TH1 cells as the controls.

- Pipet 1 mL of the cell solution into 9 wells of a 24-well plate.

- Collect the content of 3 wells into 3 separate 15 mL screw cap tubes, 3 h after initial radiolabeling.

- Rinse the now empty wells with pre-warmed medium to minimize cell loss and add the medium to the respective 15 mL screw cap tubes from step 5.1.3.

- Centrifuge the 15 mL tubes at 400 x g for 5 min and resuspend the resulting cell pellet in 1 mL of pre-warmed medium.

- Count both viable and dead cells in trypan blue separately for each 15 mL tube and calculate the percentage of viable cells.

- Repeat steps 5.1.3-5.1.6 24 and 48 h post 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb radiolabeling.

- Effects on functionality determined by IFN-γ ELISA NOTE: To assess the effect of the 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1 26-mAb radiolabel on IFN-γ production as a marker of functionality, perform an IFN-γ ELISA from a commercial supplier and refer to reference 17 for further details.

- Disperse 105 viable cells in 100 µL of medium on a 96-well plate, 3 h post 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26 radiolabeling of the cOVA-TH1 cells with 0.7 MBq, 1.4 MBq or 2.1 MBq. Use unlabeled, non-radioactive KJ1-26-mAb-labeled or 64Cu-PTSM-labeled cOVA-TH1 cells as the controls.

- Stimulate IFN-γ production in 105 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb-labeled cOVA-TH1 cells in 100 µL medium with 10 µg/mL of cOVA peptide, 5 U/mL IL-2 and 5x105 APCs in 100 µL of medium for 24 h at 37 °C and 7.5% CO2. Further controls may be the other conditions without the addition of the cOVA peptide.

- Analyze the supernatant by ELISA according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Repeat step 5.2.2. to 5.2.3. at 24 and 48 h after the labeling procedure.

- Induction of apoptosis determined by PE-Annexin V staining for flow cytometry NOTE: To assess apoptosis induction by the 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb radiolabel, use a commercially available kit for flow cytometry and prepare cell samples according to the manufacturer's instructions before staining with Annexin V for phosphatidyl serine exposition on the cell membrane.

- At 3, 24 and 48 h post 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb radiolabeling of the cOVA-TH1 cells, stain triplicates with at least 106 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb-labeled cOVA-TH1 cells with the Annexin V kit according to the manufacturer's instructions and analyze within the next hour. Use non-radioactive KJ1-26-mAb-labeled, 64Cu-PTSM-labeled and unlabeled cOVA-TH1 cells as controls. Please refer to reference 17 for further details.

- Uptake and efflux NOTE: The uptake of the 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb into the cells is measured in a dose calibrator and the efflux of radioactivity is measured in a γ-counting assay 0, 5, 24, and 48 h after radiolabeling.

- Prepare ten γ-counting tubes each for 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb-labeled cOVA-TH1 cells, the respective supernatant and the wash step.

- Transfer 106 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb-labeled cOVA-TH1 cells in 1 mL of medium into each of the ten γ-counting tubes directly after radiolabeling. For each of the time points 5, 24 and 48 h after radiolabeling, keep at least 107 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb-labeled cOVA-TH1 cells in medium on 24-well cell culture plates in an incubator at 37 °C and 7.5% CO2.

- Centrifuge the γ-counting tubes at 400 x g for 5 min and transfer the supernatant into ten new γ-counting tubes.

- Wash the cells once in 1 mL medium to remove the unbound fraction of 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb and collect the supernatant in ten new γ-counting tubes.

- Add 1 mL new medium to the cOVA-TH1 cells and determine the initial uptake value in a dose calibrator. The tubes can also be stored in an incubator at 37 °C and 7.5% CO2.

- Repeat steps 5.4.2 to 5.4.5 after 5, 24 and 48 h and measure all tubes in a γ-counter according to manufacturer's protocol. To correct for radioactive decay and for quantitative analysis, use a standard with a defined dose of radioactivity.

6. OVA-induced Acute Airway DTHR

NOTE: The migration dynamics and homing patterns of adoptively transferred and radiolabeled cOVA-TH1 cells to the site of inflammation will be visualized and quantified in an animal model for cOVA-induced airway-DTHR16,17.

Inject 8 weeks-old BALB/c mice i.p. with a mixture of 150 µL aluminum gel/50 µL cOVA-solution (10 µg in 50 µL PBS) to immunize the mice.

Two weeks after the immunization, anesthetize the mice with 100 mg/kg ketamine and 5 mg/kg xylazine by i.p. injection. Place the experimental mice on their backs and slowly pipet 100 µg cOVA dissolved in 50 µL PBS into the nostrils of the animals. The animals will inhale the solution drop by drop.

Repeat after 24 h. For stronger airway DTHR inductions, repeat again after 48 h.

To analyze the specific migration of the transferred cOVA-TH1 cells, induce airway-DTHR with turkey-or pheasant-OVA as control. Therefore, repeat steps 6.1-6.3 by using the respective OVA-protein.

7. In Vivo Imaging Using PET/CT

NOTE: In vivo imaging of 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb-labeled cOVA-TH1 cells in cOVA-DTHR diseased mice and control littermates demonstrates the specific homing and the migration dynamics of the cOVA-TH1 cells. Therefore, acquire static PET scans and anatomical CT scans sequentially 3, 24 and 48 h post adoptive cell transfer.

Directly after radiolabeling, adjust the 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb-labeled cOVA-TH1 cells to 5 x 107 cells/mL for i.p. injection of 107 cells in 200 µL.

Using a 1 mL syringe and a 30-gauge needle, draw 200 µL of the 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb-labeled cOVA-TH1 cell suspension and inject the cells i.p. into the cOVA-DTHR-diseased animals between the 4th and 5th nipple. To determine the total injected amount of radioactivity, measure the syringe in a dose calibrator before and after injection.

Anesthetize the mice, 10 min prior to the desired uptake time, with 1.5% isoflurane in 100% oxygen (flow rate: 0.7 L/min) in a temperature-controlled anesthesia box.

- In the meantime, to facilitate co-registration of PET and CT images during image analysis, fix glass capillaries containing 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb solution or free 64CuCl2 solution under the mouse bed.

- Therefore, prepare a solution of 0.37 MBq/mL and fill glass capillaries with a volume of 10 µL with this solution. Since cell-derived radioactivity signals are inherently weak, do not use high amounts of activity to make sure that the markers are not interfering with cell-derived signals in mice.

After reaching surgical tolerance, as indicated by the loss of the pedal withdrawal reflex of the hind limb, transfer the mouse to a PET-and CT-compatible small animal bed equipped with a suitable tubing system to maintain anesthesia.

Immobilize the mouse on the small animal bed using cotton swabs and surgical tape. Apply eye ointment to avoid drying of the eyes.

Transfer the mouse bed to the PET scanner, center the field of view with a focus on the lungs and acquire a 20 min static PET scan with an energy window of 350-650 keV.

Transfer the mouse bed to the CT scanner. Via scout view, center the field of view on the lungs. Acquire a planar CT image via 360 projections during a 360° rotation in the "step and shoot" mode with an exposition time of 350 ms and binning factor 4.

8. Image Analysis

Reconstruct PET list-mode data by applying statistical iterative ordered subset expectation maximization (OSEM) 2D algorithm and CT scans into a 3D image with a pixel size of 75 µm.

For image co-registration in an appropriate image analysis software (e.g. Inveon Research Workplace or Pmod), use the automatic co-registration tool. If this fails, use the glass capillaries under the mouse bed as guidance to co-register the reconstructed PET and CT images spatially in the axial, coronal and sagittal view.

- Correct the PET images for radioactive decay using the radioactive decay law and the half-time of the radionuclide 64Cu at 12.7 h. For image normalization, choose one image (A) as a reference and adjust the intensity of the image display in the respective image analysis software.

- Utilizing the values just set for the reference image (A), the injected activity (A) and the injected activity for the other images (X), normalize the other images using the following equation: (injected activity (X) /injected activity (A)) x intensity values (A).

Draw 3D volumes of interest (VOI) on the normalized PET signal of the pulmonary and perithymic LNs.

Determine the percentage injected dose per cm3 (%ID/cm3) using the following equation: (mean activity in VOI/overall activity in the mouse) x 100. For further guidance concerning image analysis, see references22,23.

Representative Results

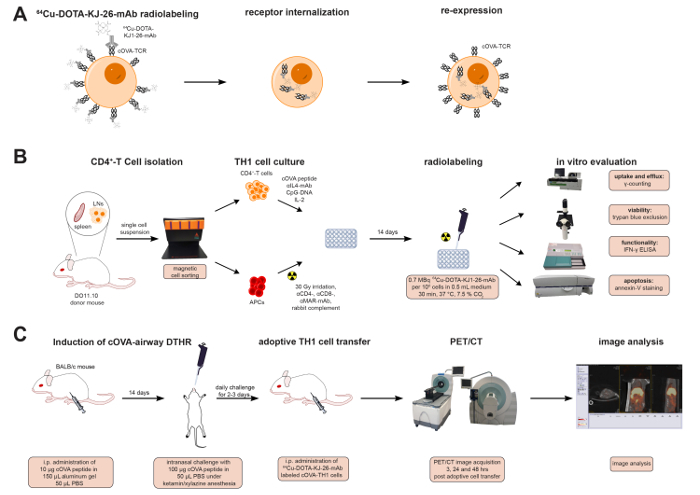

Figure 1 summarizes the labeling of cOVA-TH1 cells with the 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb and the experimental design for the in vitro and in vivo studies covered in this protocol.

Figure 1: 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb Labeling Process & Experimental Design. (A) Schematic representation of radioactive cell labeling with 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb. The 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb binds to cOVA-TCR receptors on the cell surface of the TH1 cells and is internalized with the receptor within 24 h. cOVA-TCRs are re-expressed 24 h after radiolabeling. (B) CD4+ T cells were isolated, expanded and radiolabeled with 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb in vitro. Uptake and efflux values were determined by a dose calibrator and γ-counting. Effects of the radioactive antibody on cell viability were assessed with trypan blue staining, on functionality with IFN-γ ELISA, and on induction of apoptosis with Phycoerythrin (PE)-Annexin V staining. (C) cOVA-airway DHTR was induced in female BALB/c mice. 107 TH1 cell were adoptively transferred into cOVA-airway DHTR-diseased animals directly after radiolabeling. PET/CT images were acquired 3, 24 and 48 h post adoptive cell transfer.

Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 1: 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb Labeling Process & Experimental Design. (A) Schematic representation of radioactive cell labeling with 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb. The 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb binds to cOVA-TCR receptors on the cell surface of the TH1 cells and is internalized with the receptor within 24 h. cOVA-TCRs are re-expressed 24 h after radiolabeling. (B) CD4+ T cells were isolated, expanded and radiolabeled with 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb in vitro. Uptake and efflux values were determined by a dose calibrator and γ-counting. Effects of the radioactive antibody on cell viability were assessed with trypan blue staining, on functionality with IFN-γ ELISA, and on induction of apoptosis with Phycoerythrin (PE)-Annexin V staining. (C) cOVA-airway DHTR was induced in female BALB/c mice. 107 TH1 cell were adoptively transferred into cOVA-airway DHTR-diseased animals directly after radiolabeling. PET/CT images were acquired 3, 24 and 48 h post adoptive cell transfer.

Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

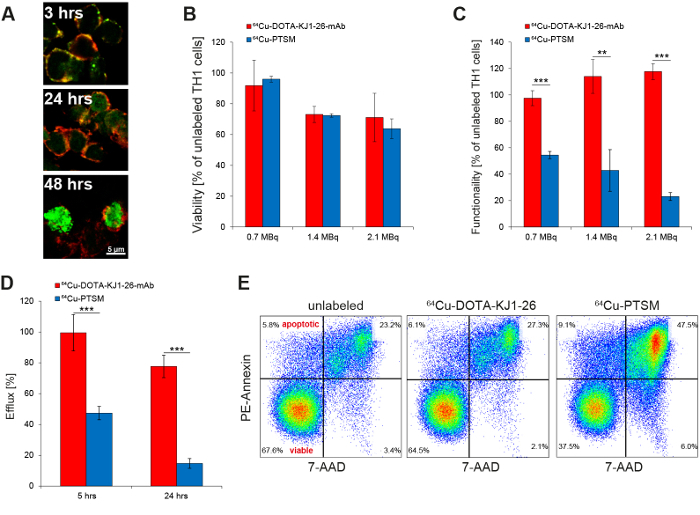

The successful intracellular labeling of the TH1 cells with the 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb was confirmed by immunohistochemistry (Figure 2A). The 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26 antibody (green) was co-localized with CD3 at the cell membrane 3 h after radiolabeling, while the signal of the mAb at the cell membrane was only faint at 24 h (yellow). At 48 h after radiolabeling, the 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-TCR complex was internalized via endocytosis with a strong signal in the cytoplasm of the TH1 cells. The applied radioactive dose of 0.7 MBq reduced viability of the TH1 cells by only 8% while higher doses of 1.4 MBq and 2.1 MBq 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb had more pronounced effects. Compared to radiolabeling with 64Cu-PTSM, however, no significant advantage of 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb was observed (Figure 2B). 64Cu-antibody radiolabeled cells showed little loss in functionality as shown by IFN-γ secretion (Figure 2C), reduced efflux of radioactivity (Figure 2D), and reduced induction of apoptosis (Figure 2E) compared to 64Cu-PTSM-labeled TH1 cells.

Figure 2: In Vitro Evaluation of Radioactive TH1 Cell Labeling with 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb. (A) Confocal microscopy proves the intracellular uptake of 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAbs (green) in cOVA-TH1 cells (cell membrane; red) within 24 h after initial labeling (This figure has been modified from reference17). (B) Titration of radioactive labeling doses of 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb or 64Cu-PTSM revealed an equal influence on the viability as detected by trypan blue exclusion 24 h post labeling. The usage of 0.7 MBq for cell labeling induced the lowest impairments of the viability (mean ± SD in percent; this figure has been modified from references16,17. (C) Titration of radioactive labeling doses of 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb or 64Cu-PTSM revealed a stronger impairment of the functionality after 64Cu-PTSM labeling, as detected by IFN-γ ELISA 24 h post labeling. An increasing dose of 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb for cell labeling had no influences on the functionality (mean ± SD in percent; statistics: Student's t-test; * p <0.05, ** p <0.01, *** p <0.001; this figure has been modified from references16,17). (D) Efflux measurements of radiolabeled cells (γ-counting) showed a higher labeling stability of 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb compared to 64Cu-PTSM 5 h and 24 h post labeling (mean ± SD in percent; statistics: Student's t-test; *** p< 0.001; this figure has been modified from17).(E) Respective flow cytometry (PE-Annexin V) diagrams indicate a higher apoptosis induction 24 h after 64Cu-PTSM labeling compared to 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb-labeling (This figure has been modified from reference17).

Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2: In Vitro Evaluation of Radioactive TH1 Cell Labeling with 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb. (A) Confocal microscopy proves the intracellular uptake of 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAbs (green) in cOVA-TH1 cells (cell membrane; red) within 24 h after initial labeling (This figure has been modified from reference17). (B) Titration of radioactive labeling doses of 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb or 64Cu-PTSM revealed an equal influence on the viability as detected by trypan blue exclusion 24 h post labeling. The usage of 0.7 MBq for cell labeling induced the lowest impairments of the viability (mean ± SD in percent; this figure has been modified from references16,17. (C) Titration of radioactive labeling doses of 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb or 64Cu-PTSM revealed a stronger impairment of the functionality after 64Cu-PTSM labeling, as detected by IFN-γ ELISA 24 h post labeling. An increasing dose of 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb for cell labeling had no influences on the functionality (mean ± SD in percent; statistics: Student's t-test; * p <0.05, ** p <0.01, *** p <0.001; this figure has been modified from references16,17). (D) Efflux measurements of radiolabeled cells (γ-counting) showed a higher labeling stability of 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb compared to 64Cu-PTSM 5 h and 24 h post labeling (mean ± SD in percent; statistics: Student's t-test; *** p< 0.001; this figure has been modified from17).(E) Respective flow cytometry (PE-Annexin V) diagrams indicate a higher apoptosis induction 24 h after 64Cu-PTSM labeling compared to 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb-labeling (This figure has been modified from reference17).

Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

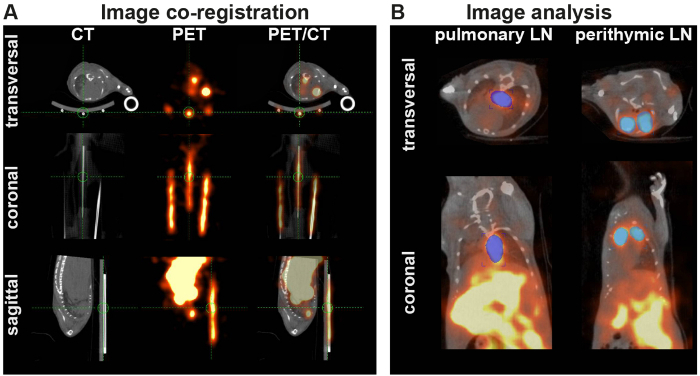

After adoptive transfer of 107 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb-labeled cOVA-TH1 cells into cOVA-DTHR-diseased animals and untreated controls, high resolution static PET and anatomical CT images were acquired. For image analysis, images were fused in the coronal, axial and sagittal view with the help of glass capillaries containing a small amount of 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb (Figure 3A). VOIs were drawn on the pulmonary and perithymic LNs on the decay-corrected and normalized PET images to calculate the percentage injected dose per cm3 (Figure 3B).

Figure 3: PET/CT-co-registration and Analysis. (A) PET and CT images were co-registered in image analysis software. If automated registration by the software failed, the images were fused by overlaying the PET and CT signals of glass capillaries (markers), filled with radioactivity and fixed under the animal bed. (B) VOIs are placed on the corrected and normalized PET signals of the perityhmic and pulmonary LNs. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3: PET/CT-co-registration and Analysis. (A) PET and CT images were co-registered in image analysis software. If automated registration by the software failed, the images were fused by overlaying the PET and CT signals of glass capillaries (markers), filled with radioactivity and fixed under the animal bed. (B) VOIs are placed on the corrected and normalized PET signals of the perityhmic and pulmonary LNs. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

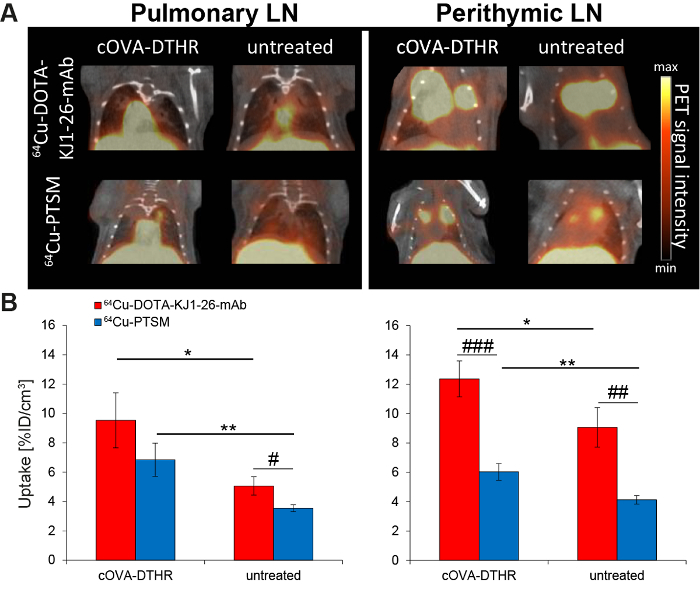

cOVA-TH1 cell migration was tracked to the pulmonary and perithymic LN as cOVA-presentation sites in airway DTHR. In vivo PET signals derived from 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb-labeled cOVA-TH1 cells were considerably higher than signals from 64Cu-PTSM-labeled cells (Figure 4A). cOVA-TH1 cell uptake values in the pulmonary and perithymic LNs were significantly increased in DTHR-diseased animals compared to untreated control littermates (Figure 4B).

Figure 4: cOVA-TH1 Cell Tracking in the Airway DTHR Model by In Vivo PET/CT. (A) Respective PET/CT images of adoptively transferred cOVA-TH1 cells, which were previously labeled with 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb or 64Cu-PTSM, into cOVA-DTHR-diseased or untreated mice. The transferred cOVA-TH1 cells homed to the pulmonary and perithymic LNs. (B) Quantitative analysis of the homing sites of the cOVA-TH1 cells proved a higher homing to inflamed tissues (mean ± SD; statistics: Student's t-test; * p <0.05, ** p <0.01). The labeling with 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb proved a higher sensitivity (increased %ID/cm3) compared to 64Cu-PTSM in the different homing sites (mean ± SD, statistics: Student's t-test; # p <0.05, ## p <0.01, ### p <0.001). This figure has been modified from reference16,17.

Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 4: cOVA-TH1 Cell Tracking in the Airway DTHR Model by In Vivo PET/CT. (A) Respective PET/CT images of adoptively transferred cOVA-TH1 cells, which were previously labeled with 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb or 64Cu-PTSM, into cOVA-DTHR-diseased or untreated mice. The transferred cOVA-TH1 cells homed to the pulmonary and perithymic LNs. (B) Quantitative analysis of the homing sites of the cOVA-TH1 cells proved a higher homing to inflamed tissues (mean ± SD; statistics: Student's t-test; * p <0.05, ** p <0.01). The labeling with 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb proved a higher sensitivity (increased %ID/cm3) compared to 64Cu-PTSM in the different homing sites (mean ± SD, statistics: Student's t-test; # p <0.05, ## p <0.01, ### p <0.001). This figure has been modified from reference16,17.

Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Discussion

This protocol presents a reliable and easy method to stably radiolabel cells for in vivo tracking by PET. Utilizing this method, cOVA-TH1 cells, isolated and expanded in vitro from donor mice, could be radiolabeled with 64Cu-DOTA-KJ1-26-mAb and their homing was tracked to the pulmonary and perithymic LNs as sites of cOVA presentation in a cOVA-induced acute airway DTHR.

The modification of the mAb with the chelator requires fast and efficient working and the use of ultra-pure solutions without traces of amines. The solutions were treated with a chelating ion exchange resin to ensure proper conjugation of the DOTA-NHS active ester to amine residues of the mAb. The chelator-conjugated mAb as an intracellular radiolabel has several advantages over the use of non-specific cell labeling agents. First, the mAb provides excellent specificity allowing for the targeted labeling of a defined cell population. The mAb itself is not cytotoxic and has no detrimental effect on the viability or functionality of the cells. Next, the efflux of radioactivity from the cells was significantly reduced improving the signal-to-background ratio of the PET images17,24. By choosing a mAb with a different specificity, this method is easily transferrable to other cell populations of interest such as CD8+ TIL or CD14+ monocytes. Moreover, this cell labeling approach can be used for cell tracking studies in various animal models of inflammatory human diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis and bronchial asthma) or animal models for different human cancer types. This labeling method, however, is confined to membrane-bound receptors or differentiations markers as targets since mAbs do not passively diffuse across the cell membrane. The activation-induced internalization of the target or, simply, membrane-shuttling is advantageous. A high avidity between the mAb and the target, however, might also be sufficient for in vivo imaging, possibly with a reduced signal to background ratio.

The choice of DOTA as a chelator for our experiments was based on early work using 64Cu25. However, in the meantime DOTA was shown to not be an optimal chelator for this isotope, leading to rather high activity uptake in the liver by transchelation to superoxide dismutase26. Although using the radiolabeled antibody for in vitro labeling of cells that are then adoptively transferred should lower the risk of 64Cu release and transport to the liver, modern chelators optimized for 64Cu, like 1,4,7-triazacyclononane,1-glutaric acid-4,7-acetic acid (NODAGA) or 1,4,7-triazacyclononane-triacetic acid (NOTA), can be preferably used with our method to further enhance specificity of the obtained data27. Besides, other active esters can be used for 64Cu (e.g. N-chlorosuccinimide (NCS)) or other isotopes, such as 89Zr (e.g. desferrioxamine; DFO).

The choice of 64Cu as the radioisotope was based on the fact that in vivo cell migration and homing is a rather slow process compared to metabolic changes usually imaged by PET. 64Cu with a half-life time of 12.7 h enables the repeated imaging of cell migration over 48 h post injection. For 64Cu production, it is important to use high-grade solutions without trace metal ions to ensure the purity of 64Cu. Furthermore, the purity of 64Cu is of high importance for radiolabeling of the DOTA-mAb since multivalent metal ion impurities could lead to a reduced specific activity of the 64Cu solution to levels that preclude protein radiolabeling and consequently imaging. Although 64Cu produces a significant percentage of highly energetic, cytotoxic Auger electrons when decaying28, an adjusted dose of the radioisotope is well tolerated by the cells as represented by minimal effects on viability and functionality and low apoptosis induction after radiolabeling. Nevertheless, it is clearly advisable to initially titrate the activity dose used for radiolabeling for other cell types and adjust the radiolabeling protocol. Fast and easy in vitro evaluation methods have been demonstrated in the protocol, including the determination of viability by trypan blue exclusion and staining with PE-Annexin V for the determination of the apoptotic fractions of the cells. Both methods are relatively cheap and use easily accessible laboratory equipment. Combining PE-Annexin V staining with a dye for the discrimination of living and dead cells such as 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) would allow for the determination of the viability and apoptosis in one experimental step. As an alternative to assess the viability of labeled T cells, a 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT-) assay can be used to assess the cell metabolic activity. The evaluation of the uptake and efflux values with a dose calibrator and γ-counter are more advanced but still fast and cheap to achieve since nearly every laboratory working with radioactivity has the respective hardware on site. Gene sequencing or microchip-based methods would yield more detailed data. These methods, however, are not always easily accessible, need appropriate expertise and are most often linked to higher costs.

Although PET is not able to reach a cellular resolution like microscopic imaging techniques29, it provides excellent sensitivity in the picomolar range for the detection of even small numbers of cells within animals or humans8. Compared to other non-invasive imaging techniques such as optical imaging, PET is quantitative, not limited in penetration depth and provides high-quality images with three dimensional resolutions. Combining the high sensitivity of PET with the anatomical accuracy of CT allows for high precision imaging of cell migration. Moreover, in vivo data can be easily validated by several ex vivo methods including γ-counting for biodistribution analysis. Autoradiography of cryosections and subsequent histological staining of the cryosections can be overlaid to correlate the autoradiographic activity map with the immune cell infiltrates identified by hematoxylin and eosin staining.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Julia Mannheim, Walter Ehrlichmann, Ramona Stumm, Funda Cay, Daniel Bukala, Maren Harant as well as Natalie Altmeyer for the support during the experiments and data analysis. This work was supported by the Werner Siemens-Foundation, the DFG through the SFB685 (project B6) and Fortüne (2309-0-0).

References

- Cerri S, et al. Intracarotid Infusion of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in an Animal Model of Parkinson's Disease, Focusing on Cell Distribution and Neuroprotective and Behavioral Effects. Stem Cells Trans Med. 2015;4(9):1073–1085. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasenbach K, et al. Monitoring the glioma tropism of bone marrow-derived progenitor cells by 2-photon laser scanning microscopy and positron emission tomography. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14(4):471–481. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sood V, et al. Biodistribution of 18F-FDG-Labeled Autologous Bone Marrow – Derived Stem Cells in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Clin Nucl Med. 2015;40(9):697–700. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000000850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Diez A, et al. CD4 cells can be more efficient at tumor rejection than CD8 cells. Blood. 2007;109(12):5346–5354. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-051318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muranski P, Restifo NP. Adoptive immunotherapy of cancer using CD4+ T cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2009;21(2):200–208. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braumuller H, et al. T-helper-1-cell cytokines drive cancer into senescence. Nature. 2013;494(7437):361–365. doi: 10.1038/nature11824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer JN, et al. Eradication of B-lineage cells and regression of lymphoma in a patient treated with autologous T cells genetically engineered to recognize CD19. Blood. 2010;116(20):4099–4102. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-281931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry SR. Fundamentals of Positron Emission Tomography and Applications in Preclinical Drug Development. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2001;41(5):482–491. doi: 10.1177/00912700122010357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavaré R, et al. An Effective Immuno-PET Imaging Method to Monitor CD8-Dependent Responses to Immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2016;76(1):73–82. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavaré R, et al. Engineered antibody fragments for immuno-PET imaging of endogenous CD8+ T cells in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014;111(3):1108–1113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316922111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrenkov K, et al. Monitoring the Efficacy of Adoptively Transferred Prostate Cancer-Targeted Human T Lymphocytes with PET and Bioluminescence Imaging. J Nucl Med. 2008;49(7):1162–1170. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.047324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rini JN, et al. PET with FDG-labeled Leukocytes versus Scintigraphy with 111In-Oxine-labeled Leukocytes for Detection of Infection. Radiology. 2006;238(3):978–987. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2382041993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie D, et al. In vivo tracking of macrophage activated killer cells to sites of metastatic ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2006;56(2):155–163. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0181-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adonai N, et al. Ex vivo cell labeling with 64Cu-pyruvaldehyde-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) for imaging cell trafficking in mice with positron-emission tomography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99(5):3030–3035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052709599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Lee CCI, Sutcliffe JL, Cherry SR, Tarantal AF. Radiolabeling Rhesus Monkey CD34+ Hematopoietic and Mesenchymal Stem Cells with 64Cu-Pyruvaldehyde-Bis(N4-Methylthiosemicarbazone) for MicroPET Imaging. Mol. Imaging. 2008;7(1) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griessinger CM, et al. In Vivo Tracking of Th1 Cells by PET Reveals Quantitative and Temporal Distribution and Specific Homing in Lymphatic Tissue. J Nucl Med. 2014;55(2):301–307. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.126318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griessinger CM, et al. 64Cu antibody-targeting of the T-cell receptor and subsequent internalization enables in vivo tracking of lymphocytes by PET. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015;112(4):1161–1166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418391112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy DW, et al. Efficient production of high specific activity 64Cu using a biomedical cyclotron. Nucl. Med. Biol. 1997;24(1):35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(96)00157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalkhof S, Sinz A. Chances and pitfalls of chemical cross-linking with amine-reactive N-hydroxysuccinimide esters. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2008;392(1):305–312. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-2231-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedoya SK, Wilson TD, Collins EL, Lau K, Larkin Iii , J Isolation and Th17 Differentiation of Naive CD4 T Lymphocytes. J Vis Exp. 2013. p. e50765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Flaherty S, Reynolds JM. Mouse Naive CD4+ T Cell Isolation and In vitro Differentiation into T Cell Subsets. J Vis Exp. 2015. p. e52739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Judenhofer M, Wiehr S, Kukuk D, Fischer K, Pichler B. Small Animal Imaging. Basics and Practical Guide. Springer; 2011. Chapter 363; pp. 363–370. [Google Scholar]

- Phelps ME. PET. Molecular Imaging and Its Biological Applications. Springer-Verlag; 2004. pp. 93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Wu AM. Antibodies and Antimatter: The Resurgence of Immuno-PET. JNM. 2009;50(1):2–5. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.056887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MR, et al. In vivo evaluation of pretargeted 64Cu for tumor imaging and therapy. J Nucl Med. 2003;44(8):1284–1292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boswell CA, et al. Comparative in vivo stability of copper-64-labeled cross-bridged and conventional tetraazamacrocyclic complexes. J Med Chem. 2004;47(6):1465–1474. doi: 10.1021/jm030383m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh SC, et al. Comparison of DOTA and NODAGA as chelators for (64)Cu-labeled immunoconjugates. Nucl Med Biol. 2015;42(2):177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TE, Birky BK. Health Physics and Radiological Health. 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Helmchen F, Denk W. Deep tissue two-photon microscopy. Nat Meth. 2005;2(12):932–940. doi: 10.1038/nmeth818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]