Abstract

Recent studies suggest that vitamin D modulates innate immunity and reduces the risk of microbial infections. Little is known the role of vitamin D in anti-pneumococcal immunity in individuals with asthma. We determined the correlation between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) levels and pneumococcal antibody levels in individuals with asthma, atopic dermatitis or allergic rhinitis, and atopic sensitization status.

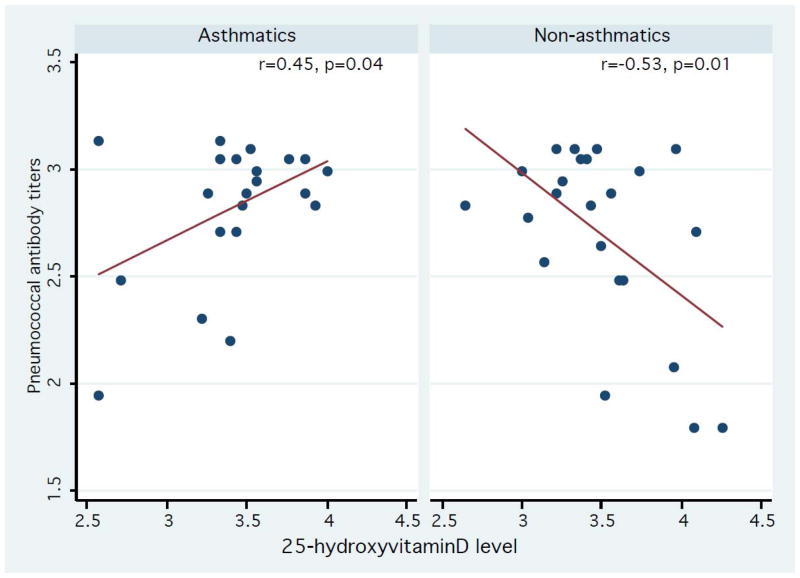

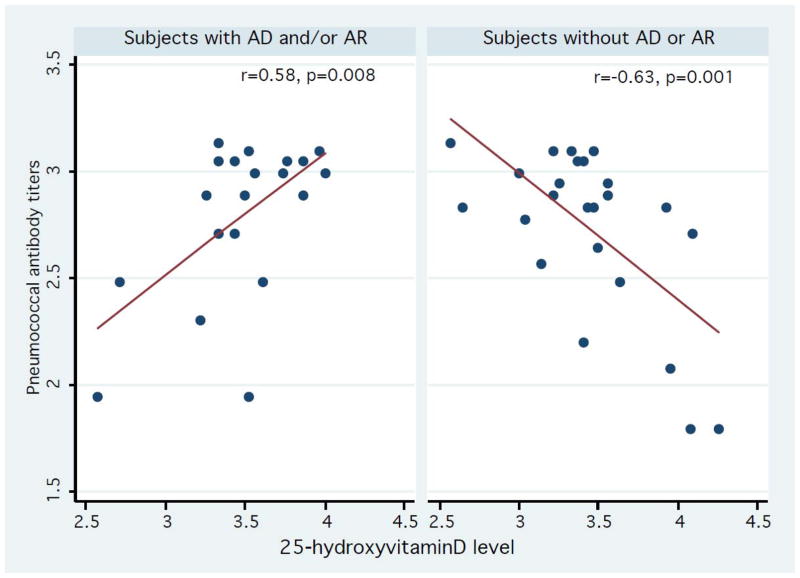

A cross-sectional study was conducted for 21 subjects with asthma and 23 subjects without asthma. Pearson’s correlation coefficient between serum 25(OH)D levels and the number of positive serotype-specific antibody levels was calculated among individuals with and without asthma, atopic dermatitis and/or allergic rhinitis, and atopic sensitization status. The overall correlation between serum 25(OH)D and the number of positive pneumococcal antibody levels in all subjects regardless of asthma was not significant (r= −0.14, p=0.38). Stratified analysis results showed that there was a positive correlation between serum 25(OH)D and the number of positive pneumococcal antibody levels in asthmatics (r= 0.45, p<0.05) and an inverse correlation was observed in non-asthmatics (r= −0.53, p<0.05). These trends were similar for subjects with and without atopic dermatitis and/or allergic rhinitis (r=0.58, p=0.008 vs. r= −0.63, p=0.001).

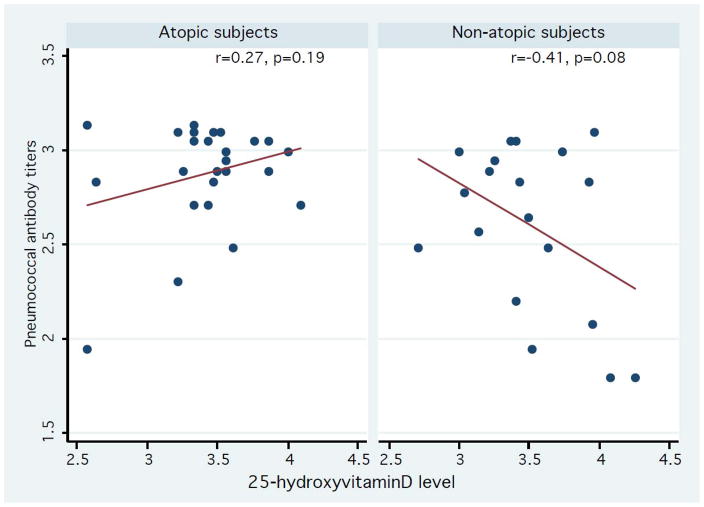

Despite similar trends in the correlation among those with and without atopic sensitization status (r=0.27, p=0.19 vs. r= −0.41, p=0.08), they did not reach statistical significance. 25(OH)D may enhance humoral immunity against S. pneumonia in subjects with atopic conditions but not without atopic conditions. Atopic conditions may have an important effect modifier in the relationship between serum 25(OH)D levels and immune function.

Keywords: Asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, atopy, pneumococcal antibody, Vitamin D, 25(OH)D

Vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency is relatively common and yet a significant public health problem.1–4 In the United States, Ginde et al reported a marked decrease in serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D(25(OH)D) levels from 1988–1994 to 2001–2004.5 The effects of serum vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency on health outcomes at a population level are yet to be determined. Recent data suggests that 1,25(OH)2D may regulate innate immune function by the altering cathelicidin (antimicrobial peptide) expression, which, in turn, might reduce microbial infections.6–9 However, little is known about the role of vitamin D status in altering adaptive immune functions such as serotype-specific pneumococcal polysaccharide antibody responses. A recent study suggested a potential association between duration of sun exposure and risk of invasive pneumococcal disease.10 However, the correlation between vitamin D status assessed by measuring serum 25(OH)D levels and pneumococcus-specific immune responses, such as serotype-specific pneumococcal antibody levels, has not been assessed. Therefore, determining the correlation between serum 25(OH)D levels and serotype-specific pneumococcal antibody responses is important given the concerns about S. pneumoniae as a significant public health threat.

In addition, even if pneumococcal polysaccharide is considered a T cell-independent type II antigen (TI-2), individuals with defect in T-cell development such as atopic or asthmatic individuals (i.e., Th2 immune profile) might have suboptimal pneumococcal antibody responses because TI-2 antigen still needs T-B cell interactions for optimal antibody response. 11, 12 Th2-cytokines directly and indirectly (reciprocal inhibition of Th1 activity) reduce antibody responses to pneumococcal antigens.12, 13 Indeed, we recently reported the similar inverse correlation between Th2-predominant immune responses (ratio of IL5/IFN-γ secretion after PBMC stimulations with house-dust mite) and serotype-specific pneumococcal antibody levels. 14 Importantly, like others, we observed that the inverse correlation between Th2-predominant immune response and serotype-specific pneumococcal antibody levels was significantly modified by clinically defined asthma status.15, 16

We reasoned that vitamin D status, determined by measuring serum 25(OH)D levels, might influence serotype-specific pneumococcal antibody levels in individuals with asthma or atopy who exhibit defective T-cell development. Addressing this question could clarify the inconsistent effects of vitamin D status and serum 25(OH)D on immune functions.17–19 Therefore, we assessed whether serum 25(OH)D levels are correlated with the number of positive serotype-specific pneumococcal antibody levels and whether the correlation is modified by asthma, atopic dermatitis or allergic rhinitis, or atopic sensitization status.

METHODS

Study design

The study was designed as a cross-sectional study that assessed the correlation between serum 25(OH)D levels and the number of positive pneumococcal antibody levels. In addition, we examined whether the correlation was modified by asthma, atopic dermatitis and/or allergic rhinitis, or atopic sensitization status by performing stratified analysis. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Mayo Clinic.

Study subjects

Study subjects were a convenience sample of 21 patients with asthma and 23 patients without asthma who received medical care at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. We applied the same enrollment and exclusion criteria as our previous study (non-Olmsted County residents, no research authorization) for using medical record for research.20–22 Briefly, the exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) the exclusion criteria for a previous longitudinal Finnish study23 (moderate or severe disability; cerebral palsy; syndromes and nasopharyngeal disorders affecting swallowing; ear, nose, throat disorders affecting the anatomy of the nose and pharynx; documented or suspected immune deficiency; and immunosuppressive therapy); 2) those without research authorization for use of medical records; 3) receipt of blood products or immunoglobulin within 3 months; 4) documented pneumococcal diseases (e.g., acute otitis media, acute sinusitis, community acquired pneumonia) with antibiotic treatment within one month prior to enrollment; and 5) non-Olmsted County, MN residents.

Measurement of serotype-specific anti-pneumococcal polysaccharide IgG

The details of measurement of pneumococcal antibodies were previously reported.14 Briefly, antibodies to 23 serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae which were measured by microsphere photometry method at the Mayo Clinic Clinical Immunology Lab.24 A serotype-specific anti-pneumococcal polysaccharide antibody (IgG) concentration of 1.3 μg/mL or greater is considered an adequate or positive response.25 The individual serotype-specific pneumococcal antibody concentrations were coded as a binary variable (0 vs. 1). For analysis, we summed the number of positive serotype-specific antibody levels (i.e., 0 vs. 1) and thus, the possible range of the number of positive serotype-specific antibody levels were 0–23.

Measurement of Serum 25 (OH)D

We measured serum 25(OH)D levels (ng/mL) at a single point in all subjects using mass spectrometry at Mayo Clinic.26 25(OH)D concentrations were log-transformed for data analysis because data for 25(OH)D levels did not follow the Gaussian distribution.

Measurement of IL-6, IL-13, and IFN-γ

We measured LPS (lipopolysaccharide) induced IL-6 (interleukin-6) secretion by PBMCs (mononuclear cells) and tetanus toxoid induced IL-13(interleukin-13) and IFN-γ (interferon-gamma) secretion by PBMCs. IL-6, IFN-γ and IL-13 secretion from PBMCs cultured with LPS and tetanus toxoid for four days were measured by specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA). The amount of IL-6, IL-13, and IFN-γ in culture supernatants was determined by ELISA using matched-pair antibodies (Pierce, Rockford, IL), according to the manufacturer’s directions. The ELISA detection thresholds were as 0.5 pg/mL for IL-6, IL-13 and IFN-γ.

Ascertainment of asthma status

We enrolled only subjects who met the criteria for definite asthma in this study. Asthma status was ascertained by applying predetermined criteria used in previous studies.14, 20 Briefly, patients were considered to have definite asthma if a physician had made a diagnosis of asthma or if each of three conditions (1: specific asthma symptoms, 2: recurrence of asthma symptoms, and 3: two or more of eight specific asthma risk factors) were present. Patients were considered to have probable asthma if the first two of the above three conditions were present. We also confirmed asthma status at the time of enrollment.

Ascertainment of other atopic conditions

We determined atopic dermatitis or eczema and allergic rhinitis or hay fever based on a physician diagnosis documented in medical records. Also, we confirmed this diagnosis at the time of enrollment.

Determination of atopic sensitization status

Atopic sensitization status was defined in these analyses as a positive specific IgE response (≥ 0.35 kU/L) to at least one of the allergens tested (house dust mite, elm, oak, cat, ragweed, alternaria, and grass allergens). Allergen-specific IgE levels were determined in the Mayo Clinic Clinical lab, using the Phadia immunoCAP system (Phadia, Uppsala, Sweden).

Statistical analysis

We assessed the distribution of natural log-transformed serum 25(OH)D levels and positive serotype-specific pneumococcal antibody levels as both did not follow Gaussian. Subsequently, we characterized subjects with and without asthma with regard to pertinent variables. We used Pearson’s correlation coefficient to assess the overall correlation between serum 25(OH)D levels and the number of positive serotype-specific pneumococcal antibody levels. To examine the potential effect modification by asthma, we determined the correlation between serum 25(OH)D levels and the number of positive serotype-specific pneumococcal antibody levels by asthma. We also assessed the potential effect modification of the correlation between serum 25(OH)D levels and the number of positive serotype-specific pneumococcal antibody levels by atopic dermatitis and/or allergic rhinitis and atopic sensitization status. Statistical significance was tested at a two-sided alpha error of 0.05, and data analysis was performed using Stata version 10 (State College, Texas)

RESULTS

Study subjects

The details of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of study subjects are summarized in Table I. Briefly, of the 44 subjects, 23 (52.3%) were male, and 36 (81.8%) were Caucasians. Eight subjects (18.2%) were younger than 18 years of age. Twenty-one (48%) subjects had asthma, 20 (45%) had atopic dermatitis and/or allergic rhinitis, and 25(57%) had atopic sensitization status.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants

| Characteristic | Control (N=23) | Asthma (N=21) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at index date (y) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 39.9 ± 21.0 | 38.1 ± 18.6 | 0.77 |

| Median (Interquartile range) | 37.8 (59.6–24.8) | 39.8 (23.5–54.5) | |

| Sex, no (%) | 0.54 | ||

| Male | 11 (47.9) | 12 (57.1) | |

| Female | 12 (52.1) | 9 (42.9) | |

| Tobacco smoke exposure at index date, no. (%) | 0.50 | ||

| Yes | 1 (4.3) | 2 (9.5) | |

| No | 22 (95.7) | 19 (90.5) | |

| Inhaled corticosteroid intake at the enrollment | 0.41 | ||

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 11 (52.4) | |

| No | 23 (100.0) | 10 (47.6) | |

| Other atopic conditions (atopic dermatitis and/or allergic rhinitis) | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 4 (17) | 16 (76) | |

| No | 19 (83) | 5 (24) | |

| Atopic sensitization status* | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 7 (30.4) | 18 (85.7) | |

| No | 16 (69.6) | 3 (14.3) | |

| Family history of asthma | 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 4 (17.4) | 13 (65.0) | |

| No | 19 (82.6) | 7 (35.0) | |

| Pneumococcal vaccinations | 0.27 | ||

| PCV-7 | 2 (8.7) | 1 (4.7) | |

| PPV23 | 3 (13) | 7 (33) | |

| Never received | 18 (78.3) | 13 (61.9) | |

| Comorbid conditions** | 0.29 | ||

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.8) | |

| No | 23 (100.0) | 20 (95.2) | |

| 25-hydroxyvitamin D (ng/mL) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 35.6 ± 14.4 | 32.5 ± 11.6 | 0.44 |

: ≥ 0.35 IU/mL specific IgE levels in house dust mite, elm, oak, cat, ragweed, alternaria, and grass allergens by using CAP;

only one subject had the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended pneumococcal vaccine eligible conditions (chronic obstructive lung disease).

The association of 25(OH)D and pneumococcal antibody levels

Amongst all subjects, there was no significant correlation between serum 25(OH)D levels and the number of positive serotype specific pneumococcal antibody levels (r= −0.14, p=0.38). However, stratified analysis results showed that there was a significant positive correlation between serum 25(OH)D levels and the number of positive serotype specific pneumococcal antibody levels in asthmatics, (r= 0.45, p=0.04) whereas there was an inverse correlation in non-asthmatics (r= −0.53, p=0.01) (Figure 1). There were similar trends for subjects with atopic sensitization status (r=0.27, p=0.19) and those without atopic sensitization status (r= −0.41, p=0.08), but the correlations did not reach statistical significance (Figure 2). We also found that there were similar trends in subjects with atopic dermatitis and/or allergic rhinitis (r=0.58, p=0.008 for individuals with atopic dermatitis or allergic rhinitis vs. r= −0.63, p=0.001 for those without such conditions) (Figure 3). As a secondary analysis, we analyzed the correlation between serum 25(OH)D levels and the number of positive serotype-specific pneumococcal antibody levels after stratifying pneumococcal vaccination status: vaccinated group, not-vaccinated group, and all subjects despite the limited statistical power (data not shown). Overall, we observed the similar effect modifying trends on the correlation between serum 25(OH)D and the number of positive serotype-specific pneumococcal antibody levels by atopic conditions. For example, among subjects without pneumococcal vaccinations (n=31), there was a positive correlation trend between serum 25(OH)D levels and the number of positive serotype-specific pneumococcal antibody levels in asthmatics, (r= 0.41, p=0.17), whereas there was an inverse correlation in non-asthmatics (r= −0.46, p=0.05). Among those with pneumococcal vaccinations (n=13), there was a similar positive correlation trend between serum 25(OH)D and the number of positive serotype-specific pneumococcal antibody levels in asthmatics, (ρ= 0.68, p=0.063), whereas there was an inverse correlation in non-asthmatics (ρ= −0.80, p=0.10).

Figure 1.

Association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and the number of serotype positive pneumococcal antibodies in asthmatics and non-asthmatics. Y-axis: log-transformed number of serotype positive pneumococcal antibody levels (range: 1.79–3.14). X-axis: log-transformed 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels (range: 2.57–4.26). Data were fitted to a least square model. The correlation between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and the number of serotype positive pneumococcal antibody levels was modified by clinically defined asthma status.

Figure 2.

Association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and the number of serotype positive pneumococcal antibody levels in participants with and without atopic sensitization status based on common allergen-specific IgE levels (≥ 0.35 IU/mL). Y-axis: log-transformed number of serotype positive pneumococcal antibody levels (range: 1.79–3.14). X-axis: log-transformed 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels (range: 2.57–4.26). Data were fitted to a least square model. The trend of correlation between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and the number of serotype positive pneumococcal antibody levels were similar in subjects classified by asthma.

Figure 3.

Association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and the number of serotype positive pneumococcal antibody levels in subjects with and without other atopic conditions based on a physician diagnosis documented in a medical record (AD: atopic dermatitis and AR: allergic rhinitis). Y-axis: log-transformed number of serotype positive pneumococcal antibody levels (range: 1.79–3.14). X-axis: log-transformed 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels (range: 2.57–4.26). Data were fitted to a least square model. The correlation between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and the number of serotype positive pneumococcal antibody levels was modified by clinically defined AD and/or AR.

The role of 25(OH)D in innate and cell-mediated immune functions

Overall, there was no correlation between serum 25(OH)D levels and IL-6 secretion by PBMCs stimulated with LPS (a measure of innate immune function). Also, we did not observe a significant correlation between 25(OH)D levels and IL-13 and IFN-γ secretion by PBMCs stimulated with tetanus toxoid (surrogate measures for cell-mediated immune function). These correlations were not significantly modified by asthma, atopic dermatitis and/or allergic rhinitis, and atopic sensitization status (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In our study, asthmatics showed a positive correlation between serum 25(OH)D levels and the number of positive serotype-specific pneumococcal antibody levels, ( r= 0.45, p=0.04) but non-asthmatics showed an inverse correlation (r= −0.53, p=0.01). Theses trends were stronger among those with and without atopic dermatitis and/or allergic rhinitis (r=0.58, p=0.008 vs. r= −0.63, p=0.001, respectively). However, there were similar trends among those with and without atopic sensitization status but the correlation did not reach statistical significance. These results suggest that the association between serum 25(OH)D (an index of vitamin D status) and pneumococcal antibody response depends on the atopic status of individuals, and the relationship between serum 25(OH)D and pneumococcal antibody response may not be homogeneous for all individuals. The results based on the analysis stratified by pneumococcal vaccination status showed the similar trends (data not shown). Kriesel et al reported there were no significant differences in the overall influenza vaccine response between groups with and without 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3) administration during influenza vaccination; however, they did not report the results stratified by atopic status.27 Previous studies have reported the associations between 25(OH)D and respiratory infections and atopic diseases.17, 28–32 Ginde et al reported lower serum 25(OH)D levels were associated with a risk of recent upper respiratory infections (OR:1.24–1.36) and this association was stronger in individuals with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (OR:2.26–5.67).31 There is a report suggesting that serum total IgG levels were negatively associated with serum 25(OH)D levels in certain individuals such as patients with cystic fibrosis.33 At present, no studies similar to ours are available and there is scant information on the correlation between serum 25(OH)D and humoral immune function.34–36

The results of previous studies on the relationship between 1,25(OH)2D3 and cytokine secretions reflecting innate and cellular immunities have been inconsistent. 37, 38 The mechanisms by which 25(OH)D might influence pneumococcal antibody titers or humoral immune response in general are unknown. Further studies are needed to identify the mechanisms underlying our study findings. It is unknown whether this observation applies to humoral immune responses to other bacterial or viral antigens. Further investigations regarding the quantitative association between serum 25(OHD and humoral responses are needed. Unlike humoral immune function such as pneumococcal antibody levels, IL-6, IL-13 and IFN–γ were not associated with serum 25(OH)D and there was no effect modification by atopic conditions (data not shown). The role of 25(OH)D in adaptive immunity needs further studies.

Although the mechanisms underlying our study findings are unknown, our study findings may have important public health implications for asthmatics given the concerns about S. pneumoniae as a significant public health threat, the knowledge that asthmatics are at a high-risk for invasive pneumococcal diseases,20, 39, 40 and that asthmatics often have suboptimal pneumococcal antibody levels.14 The role of nutritional intervention to improve pneumococcal antibody response in high-risk individuals for pneumococcal diseases such as those with atopic conditions may be considered.41 However, we caution that our results not be over-interpreted to mean that all subjects should receive vitamin D supplementation. The recent Institute of Medicine report raised a concern over excessive vitamin D intake 42 and medical community should remain vigilant about unrecognized harmful effects of certain treatments introduced in clinical medicine.43 Previous studies have examined the association between 25(OH)D and innate immune function,6–8, 44, 45 but the results have been inconsistent.17–19, 46 Our study results suggest that the relationship between serum 25(OH)D levels and immune functions needs to be assessed in relation to atopic status, which may account for the potential inconsistency.

Our study has several potential limitations. Most asthmatics have other atopic conditions and atopic sensitization, and thus it is difficult to discern which specific condition is responsible for the relationship between 25(OH)D and pneumococcal antibody levels. Although this is a limitation, it could hint a potential causal attribute given the predictability and coherence. Our criteria for asthma and other atopic conditions were practical but might not be accurate. Given the lack of gold standard for defining asthma, misclassification of asthma ascertainment in our study is likely to allow null hypothesis to be supported. Another limitation of our study is limited statistical power, which did not allow analyses assessing complex interactions and adjustments. We did not collect dietary information regarding dietary vitamin D intake or sunlight exposure in this study. Finally, given the predominantly Caucasian population of our study, one needs to be cautious when generalize the findings to other racial groups.47

In conclusion, 25(OH)D may enhance humoral immunity against S. pneumoniae in asthmatics but not in non-asthmatics. While individuals with atopic conditions may be encouraged to take vitamin D supplementation, the effect of vitamin D supplementation on immune functions in normal individuals needs to be assessed. A larger prospective study is needed to confirm our findings.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for secretarial support from Elizabeth Krusemark and research support from the staff of the Pediatric Asthma Epidemiology Research Unit. This work was supported by a grant from the T. Denny Sanford Collaborative Research Fund, a partnership between Sanford Health and Mayo Clinic and the Bridge Award from Mayo Foundation. It was possible by the REP form the National institutes of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and Skin Disease (R01-AR 30582)

Abbreviations used

- SPD

Severe pneumococcal disease

- DCs

Dendritic cells

- Treg

Regulatory T cell

- PBMCs

Mononuclear cells

- IFN-γ

Interferon-gamma

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- IL-6

Interleukin-6

- IL-13

Interleukin-13

- ABPA

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis

- 25(OH)D

25-hydroxyvitamin D

- 1,25(OH)2D3

1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3

References

- 1.Rajakumar K, Thomas SB. Reemerging nutritional rickets: a historical perspective. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005 Apr;159(4):335–341. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.4.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elliott ME, Binkley NC, Carnes M, et al. Fracture risks for women in long-term care: high prevalence of calcaneal osteoporosis and hypovitaminosis D. Pharmacotherapy. 2003 Jun;23(6):702–710. doi: 10.1592/phco.23.6.702.32182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holick MF. High prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy and implications for health. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006 Mar;81(3):353–373. doi: 10.4065/81.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim DH, Sabour S, Sagar UN, Adams S, Whellan DJ. Prevalence of hypovitaminosis D in cardiovascular diseases (from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001 to 2004) Am J Cardiol. 2008 Dec 1;102(11):1540–1544. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ginde AA, Liu MC, Camargo CA., Jr Demographic differences and trends of vitamin D insufficiency in the US population, 1988–2004. Arch Intern Med. 2009 Mar 23;169(6):626–632. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang TT, Nestel FP, Bourdeau V, et al. Cutting edge: 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 is a direct inducer of antimicrobial peptide gene expression. J Immunol. 2004 Sep 1;173(5):2909–2912. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ginde AA, Mansbach JM, Camargo CA., Jr Vitamin D, respiratory infections, and asthma. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2009 Jan;9(1):81–87. doi: 10.1007/s11882-009-0012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu PT, Stenger S, Tang DH, Modlin RL. Cutting edge: vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis is dependent on the induction of cathelicidin. J Immunol. 2007 Aug 15;179(4):2060–2063. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baeke F, Takiishi T, Korf H, Gysemans C, Mathieu C. Vitamin D: modulator of the immune system. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010 Aug;10(4):482–496. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White AN, Ng V, Spain CV, Johnson CC, Kinlin LM, Fisman DN. Let the sun shine in: effects of ultraviolet radiation on invasive pneumococcal disease risk in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:196. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffioen AW, Toebes EA, Rijkers GT, Claas FH, Datema G, Zegers BJ. The amplifier role of T cells in the human in vitro B cell response to type 4 pneumococcal polysaccharide. Immunol Lett. 1992 May;32(3):265–272. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(92)90060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan AQ, Lees A, Snapper CM. Differential regulation of IgG anti-capsular polysaccharide and antiprotein responses to intact Streptococcus pneumoniae in the presence of cognate CD4+ T cell help. J Immunol. 2004 Jan 1;172(1):532–539. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan AQ, Shen Y, Wu ZQ, Wynn TA, Snapper CM. Endogenous pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines differentially regulate an in vivo humoral response to Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 2002 Feb;70(2):749–761. doi: 10.1128/iai.70.2.749-761.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung JA, Kita H, Dhillon R, et al. Influence of asthma status on serotype-specific pneumococcal antibody levels. Postgrad Med. 2010 Sep;122(5):116–124. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2010.09.2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee HJ, Kang JH, Henrichsen J, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in healthy children and in children at increased risk of pneumococcal infection. Vaccine. 1995 Nov;13(16):1533–1538. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00093-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arkwright PD, Patel L, Moran A, Haeney MR, Ewing CI, David TJ. Atopic eczema is associated with delayed maturation of the antibody response to pneumococcal vaccine. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000 Oct;122(1):16–19. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01338.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laaksi I, Ruohola JP, Tuohimaa P, et al. An association of serum vitamin D concentrations < 40 nmol/L with acute respiratory tract infection in young Finnish men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007 Sep;86(3):714–717. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.3.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leow L, Simpson T, Cursons R, Karalus N, Hancox RJ. Vitamin D, innate immunity and outcomes in community acquired pneumonia. Respirology. 2011 May;16(4):611–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.01924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li-Ng M, Aloia JF, Pollack S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of vitamin D3 supplementation for the prevention of symptomatic upper respiratory tract infections. Epidemiol Infect. 2009 Oct;137(10):1396–1404. doi: 10.1017/S0950268809002404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juhn YJ, Kita H, Yawn BP, et al. Increased risk of serious pneumococcal disease in patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008 Oct;122(4):719–723. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldblatt D, Hussain M, Andrews N, et al. Antibody responses to nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae in adults: a longitudinal household study. J Infect Dis. 2005 Aug 1;192(3):387–393. doi: 10.1086/431524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanania NA, Sockrider M, Castro M, et al. Immune response to influenza vaccination in children and adults with asthma: effect of corticosteroid therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004 Apr;113(4):717–724. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.12.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldblatt D, Hussain M, Andrews N, et al. Antibody responses to nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae in adults: a longitudinal household study. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2005 Aug 1;192(3):387–393. doi: 10.1086/431524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacob GL, Homburger HA. Simultaneous Quantitative Measurement of IgG Antibodies to Streptococcus Pneumoniae Serotypes by Microsphere Phtomometry. J Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2004;113(2):pS288. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sorensen RU, Leiva LE, Javier FC, 3rd, et al. Influence of age on the response to Streptococcus pneumoniae vaccine in patients with recurrent infections and normal immunoglobulin concentrations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998 Aug;102(2):215–221. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(98)70089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roth HJ, Schmidt-Gayk H, Weber H, Niederau C. Accuracy and clinical implications of seven 25-hydroxyvitamin D methods compared with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry as a reference. Ann Clin Biochem. 2008 Mar;45(Pt 2):153–159. doi: 10.1258/acb.2007.007091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kriesel JD, Spruance J. Calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxy-vitamin D3) coadministered with influenza vaccine does not enhance humoral immunity in human volunteers. Vaccine. 1999 Apr 9;17(15–16):1883–1888. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00476-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frieri M. The role of vitamin D in asthmatic children. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011 Feb;11(1):1–3. doi: 10.1007/s11882-010-0151-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor CE, Camargo CA., Jr Impact of micronutrients on respiratory infections. Nutr Rev. 2011 May;69(5):259–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou Y, Zhou X, Wang X. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 prevented allergic asthma in a rat model by suppressing the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2008 May-Jun;29(3):258–267. doi: 10.2500/aap.2008.29.3115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ginde AA, Mansbach JM, Camargo CA., Jr Association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and upper respiratory tract infection in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2009 Feb 23;169(4):384–390. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brehm JM, Schuemann B, Fuhlbrigge AL, et al. Serum vitamin D levels and severe asthma exacerbations in the Childhood Asthma Management Program study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Jul;126(1):52–58. e55. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pincikova T, Nilsson K, Moen IE, et al. Inverse relation between vitamin D and serum total immunoglobulin G in the Scandinavian Cystic Fibrosis Nutritional Study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011 Jan;65(1):102–109. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chambers ES, Hawrylowicz CM. The impact of vitamin D on regulatory T cells. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011 Feb;11(1):29–36. doi: 10.1007/s11882-010-0161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heine G, Niesner U, Chang HD, et al. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) promotes IL-10 production in human B cells. Eur J Immunol. 2008 Aug;38(8):2210–2218. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taher YA, van Esch BC, Hofman GA, Henricks PA, van Oosterhout AJ. 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 potentiates the beneficial effects of allergen immunotherapy in a mouse model of allergic asthma: role for IL-10 and TGF-beta. J Immunol. 2008 Apr 15;180(8):5211–5221. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jorde R, Sneve M, Torjesen PA, Figenschau Y, Goransson LG, Omdal R. No effect of supplementation with cholecalciferol on cytokines and markers of inflammation in overweight and obese subjects. Cytokine. 2010 May;50(2):175–180. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pichler J, Gerstmayr M, Szepfalusi Z, Urbanek R, Peterlik M, Willheim M. 1 alpha,25(OH)2D3 inhibits not only Th1 but also Th2 differentiation in human cord blood T cells. Pediatr Res. 2002 Jul;52(1):12–18. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200207000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Almirall J, Bolibar I, Serra-Prat M, et al. New evidence of risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia: a population-based study. Eur Respir J. 2008 Jun;31(6):1274–1284. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00095807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Talbot TR, Hartert TV, Mitchel E, et al. Asthma as a risk factor for invasive pneumococcal disease. N Engl J Med. 2005 May 19;352(20):2082–2090. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanderson P, Elsom RL, Kirkpatrick V, et al. UK food standards agency workshop report: diet and immune function. Br J Nutr. 2010 Jun;103(11):1684–1687. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509993692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Slomski A. IOM endorses vitamin D, calcium only for bone health, dispels deficiency claims. Jama. 2011 Feb 2;305(5):453–454. 456. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Riegelman RK. What to do until the FDA arrives. Postgrad Med. 1981 Dec;70(6):103–108. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1981.11715935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Di Nardo A, Vitiello A, Gallo RL. Cutting edge: mast cell antimicrobial activity is mediated by expression of cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide. J Immunol. 2003 Mar 1;170(5):2274–2278. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu PT, Stenger S, Li H, et al. Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response. Science. 2006 Mar 24;311(5768):1770–1773. doi: 10.1126/science.1123933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamshchikov AV, Kurbatova EV, Kumari M, et al. Vitamin D status and antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin (LL-37) concentrations in patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010 Sep;92(3):603–611. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oduwole AO, Renner JK, Disu E, Ibitoye E, Emokpae E. Relationship between Vitamin D Levels and Outcome of Pneumonia in Children. West Afr J Med. 2010 Nov-Dec;29(6):373–378. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v29i6.68261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]