Abstract

Importance

Little is known about the relative contributions of multisystem degenerative processes across the spectrum of pre-demented cognitive decline in Parkinson disease (PD).

Objective

To investigate the relative frequency of caudate nucleus dopaminergic and forebrain cholinergic deficits across a spectrum of cognitively impaired PD subjects in order to explore their relative individual and combined contributions to cognitive impairment in PD.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Academic movement disorders clinic.

Participants

A predominantly non-demented cohort of 143 PD subjects, mean age 65.5±7.4 years, mean Hoehn and Yahr stage 2.4±0.6.

Main outcome measures

Binary classification of [11C]PMP acetylcholinesterase and caudate nucleus [11C]DTBZ monoaminergic PET imaging based on normative data. The frequency of significant degenerative processes based on normative values was determined for consecutive intervals of cognitive impairment ranging from no or minimal (Z>−0.5) to more severe cognitive impairment (Z≤ −2).

Results

Across the spectrum ranging from minimal (Z>−0.5) to more severe global cognitive impairment scores (Z≤ −2), caudate nucleus dopaminergic denervation was relatively frequent in those with minimal or no cognitive changes (51.1%) and increased in subjects with more severe cognitive impairments (χ2=12.8, P=0.012). Cortical cholinergic denervation frequency increased monotonically with increasing cognitive impairment from 24.7% (Z>−0.5) to 85.7% (Z≤ −2; χ2=23.2, P=0.0001). 87.0% of subjects with neocortical cholinergic deficits had caudate nucleus dopaminergic deficits. Multiple regression analysis (model F=7.51, P<0.0001) showed both independent cognitive predictions for caudate nucleus dopaminergic (F=7.25, P=0.008) and cortical cholinergic (F=7.50, P=0.007) degenerations and also interaction effects (F=5.40, P=0.022).

Conclusions

Cortical cholinergic denervation is a major neurodegeneration associated with progressive declines across the spectrum of cognitive impairment in PD and typically occurs in the context of significant caudate nucleus dopaminergic denervation. Our findings imply that dopaminergic and cholinergic degenerations exhibit both independent and interactive contributions to cognitive impairment in PD.

Keywords: Acetylcholinesterase, cognitive impairment, dopamine, motor, Parkinson disease, PET

Introduction

Clinical studies of the heterogeneous nature of cognitive impairments in PD have focused on disentangling and characterizing inter-individual variation in deficits, differences in treatment responses, and risk estimations for conversion to PD dementia (PDD) 1,2. An intriguing dual syndrome hypothesis was proposed to explain the heterogeneity of cognitive changes in PD 2. This model posits that the high frequency of fronto-striatal executive dysfunction relates to common dopaminergic deficits and that the development of dementia is associated with more widespread cortical changes secondary to additional pathologies, including cholinergic deficits 1,2. In vivo neuroimaging studies provide some support for this hypothesis. Although dopaminergic denervation affects specific cognitive functions in PD, striatal and limbofrontal dopaminergic changes are present also in non-demented PD subjects, and their presence is not sufficient to explain the development of dementia in PD 3. In contrast, greater cholinergic denervation is shown consistently in PDD compared to PD 3,4.

Others and we have previously reported on dopaminergic and cholinergic associations with cognitive impairment in PD 3,5. This purpose of the current study is to directly compare the relative frequency and potential for interactions between these two neurodegenerations across the mostly non-demented cognitive spectrum in PD. In order to determine the frequency of each of the different pathologies, we used normative data to dichotomize significant deficits. Although profound putaminal nigrostriatal denervation is a defining feature of patients with PD with essentially no overlap with putaminal dopaminergic denervation in normal control subjects, denervation of the caudate nucleus -which has prominent non-motor cognitive connections- is less severe and occurs in a range with partial overlap between innervation levels seen in PD and those of normal control subjects 6,7. We investigated also possible interactive cognitive effects between these two system degenerations in PD. We hypothesized that unlike more common dopaminergic deficits frequency of cholinergic denervation is low in PD subjects with minimal cognitive changes but very prevalent in those with more severe cognitive impairment. Furthermore, we hypothesized that combined dopaminergic and cholinergic changes are not merely additive but also have interactive effects on cognitive performance in PD.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

This cross-sectional study involved 143 subjects with PD (106 males, 37 females), mean age 65.5±7 and duration of disease of 6.0±4.3 years. PD subjects met the UK Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank clinical diagnostic criteria 8. The majority of subjects were on dopaminergic drugs but none were on anti-cholinergic or cholinergic drugs. The mean Hoehn and Yahr stage was 2.4±0.6 9. The Movement Disorder Society-revised Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) motor score in the practically defined overnight “off” state was 32.5±14.2 10.

Each patient underwent a detailed cognitive examination following an approach previously reported to characterize cognitive impairment in PD 11. These tests included measures of verbal memory: California Verbal Learning Test 12; executive/reasoning functions: WAIS III Picture Arrangement test 13, and Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System Sorting Test 14; attention/psychomotor speed as absolute time on the Stroop 1 test 15; and visuospatial function: Benton Judgment of Line Orientation test 16. Composite z-scores were calculated for these different cognitive domains based on normative data. A global composite cognitive Z-score was calculated as the mean of the domain Z-scores.

To study the relative contributions of different degenerative processes, we stratified our cohort by severity of cognitive impairment. The magnitude of cognitive impairment was fractionated using categories of consecutive 0.5 Z-score ranges of global composite Z-scores. The study groups ranged from no or minimal global cognitive impairments (Z>−0.5), mild to moderate cognitive impairments (−0.5 to −1.0, −1.0 to −1.5, −1.5 to −2), to more severe cognitive impairment (Z≤ −2). There were 89 patients in the best cognitive range subgroup (Z>−0.5), 26 in the −0.5 to −1.0 subgroup, 10 in the −1.0 to −1.5 subgroup, 11 in the −1.5 to 2 subgroup, and 7 in the Z≤ −2 cognitive range subgroup.

The study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT01565473) was approved by and study procedures were followed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Imaging techniques

All subjects underwent brain MRI and [11C] methyl-4-piperidinyl propionate (PMP) acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and [11C]dihydrotetrabenazine (DTBZ) vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 (VMAT2) PET except for one subject where the DTBZ PET scan failed for technical reasons. All DTBZ PET scans showed evidence of nigrostriatal degeneration. MRI was performed on a 3 Tesla Philips Achieva system (Philips, Best, The Netherlands) and PET imaging was performed in 3D imaging mode with an ECAT Exact HR+ tomograph (Siemens Molecular Imaging, Inc., Knoxville, TN) as previously reported 5.

[11C]DTBZ and [11C]PMP were prepared as described previously 17. Dynamic PET scanning was performed for 70 minutes using a bolus dose of 15 mCi [11C]PMP dose. A 60 minute bolus/infusion protocol was used for [11C]DTBZ (15 mCi) 18.

Image Analysis

Imaging registration was performed as previously reported 5. Interactive Data Language image analysis software (Research systems, Inc., Boulder, CO) was used to manually trace volumes of interest on MRI images to include the thalamus and neostriatum (caudate nucleus, putamen) of each hemisphere. Total neocortical VOI were defined using semi-automated threshold delineation of the cortical gray matter signal on the magnetic resonance imaging scan. AChE [11C]PMP hydrolysis rates (k3) were estimated using the striatal volume as the tissue reference 19. AChE PET imaging assesses the two major brain cholinergic projection systems with cortical uptake reflecting largely basal forebrain and thalamic uptake principally reflecting pedunculopontine nucleus/complex (PPN) integrity.

[11C]DTBZ caudate nucleus DVR were estimated using the Logan plot graphical analysis method using cortical reference tissue 20. The mean caudate nucleus VMAT2 DVR was 1.89±0.37 (range 1.23–3.49). The mean forebrain neocortical and PPN-thalamic AChE hydrolyis rates were 0.0237±0.0028 (range 0.0167–0.0333 min−1) and 0.0546±0.0055 (range 0.0377–0.0681 min−1), respectively.

Data Analysis

The primary purpose of this study is to directly extend our previous work 5 and investigate the relative frequency of binary defined (present or absent) substantial caudate nucleus dopaminergic and cholinergic degenerative processes at different stages of cognitive impairment in PD in a more expanded subject population. Specifically, we estimated the frequency of each degenerative process in each global cognitive subgroup by classifying each subject as normal or abnormal for cholinergic forebrain or caudate dopaminergic nerve terminals as measured by the two different PET probes. Because of the significant overlap of cholinergic innervation seen between subjects with PD and healthy controls, we classified AChE PET scans as either below or within normal range. Abnormal neocortical and thalamic cholinergic innervation was based on a 5th percentile cut-off from non-PD elderly normative data (n=29, mean age 66.8 ± 10.9 years comparable to the current patient cohort) 5. Similarly, given the significant overlap of caudate nucleus dopaminergic innervation between PD and healthy control subjects 7, a 5th percentile cut-off from the same non-PD normative data set was used also to define significant deficits 5. Given the asymmetric hemispheric nigrostriatal degeneration in PD, the lowest hemispheric dopaminergic innervation status was used for the analysis. Given absence of singificant interhemispheric differences for the cholinergic system in PD, bilaterally averaged hemispheric data were used for the forebrain cortical and PPN-thalamic AChE status 21.

χ2 testing was performed for comparison of proportions of innervation deficits between groups. In addition to analysis of independent effects of cholinergic and nigrostriatal dopaminergic degenerations in PD to predict global and cognitive domain Z-scores, we also performed a post hoc multiple regression analysis of possible interaction effects between caudate nucleus dopaminergic and cortical cholinergic denervation using absolute VMAT2 and AChE innervation variables. Duration of disease was used as a co-regressor. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2, SAS institute (Cary, North Carolina). Holm-Bonferroni correction for multiple testing was performed for each main analysis.

Results

Relative frequency of dopaminergic and cholinergic deficits

Table 1 provides a summary of the relative frequencies of significant caudate nucleus dopaminergic denervation and significant neocortical and thalamic AChE deficits status in each cognitive severity subgroup for the total patient cohort (n=143). Significant caudate nucleus dopaminergic denervation was present in about two thirds of all subjects while cortical cholinergic denervation was present in only about one third of all subjects in this predominantly non-demented cohort. Thalamic cholinergic denervation was present in about one sixth of subjects (Table 1).

Table 1.

Frequency listing of significant caudate nucleus dopaminergic, neocortical and PPN-thalamic cholinergic deficits in the total cohort of patients (left column) and cognitive severity subgroups based on global cognitive z-scores ranging from no or minimal (Z >−0.5) to more severe cognitive impairment (Z ≤ −2). Statistical significances for the distribution differences for each of the neurochemical deficits between the 5 cognitive sub-groups are listed in the right column.

| Neurochemical deficit | Z-score ranges | Statistical significance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Z ≤ −2 cognitive sub-group (n=7) | Z in −1.5 to −2 range cognitive sub-group (n=11) | Z in −1.0 to −1.5 range cognitive sub-group (n=10) | Z in −0.5 to −1.0 range cognitive sub-group (n=26) | Z > −0.5 cognitive sub-group (n=88) | ||

| Caudate nucleus VMAT2 deficit (total group: 100/142, 70.4%) | n=5 (71.4%) | n=11 (100%) | n=5 (50%) | n=19 (73%) | n=45 (51.1%) | χ2=12.8, P=0.012* |

| Neocortical AChE deficit (total group: 46/143, 32.2%) | n=6 (85.7%) | n=8 (72.7%) | n=5 (50%) | n=5 (19.2%) | n=22 (24.7%) | χ2=23.20; P=0.0001* |

| PPN-thalamic AChE deficit (total group: 23/143, 16.8%) | n=2 (28.6%) | n=2 (18.2%) | n=3 (30.0%) | n=5 (19.2%) | n=11 (12.4%) | χ2=3.39; P=0.50 |

Significant variable after Holm-Bonferroni correction.

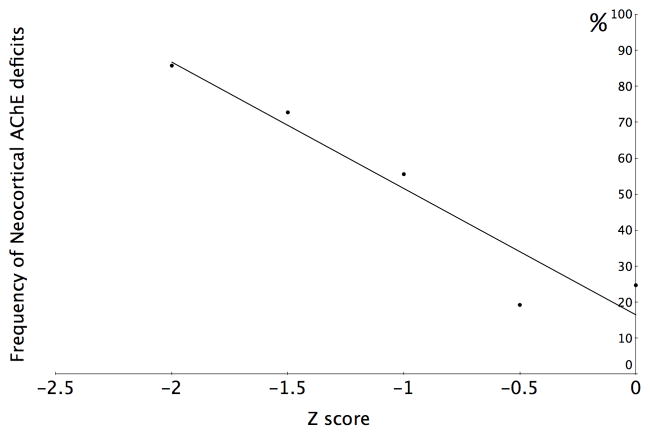

Caudate nucleus dopaminergic denervation was relatively frequent in the subgroup with minimal cognitive changes (51.1%) and caudate nucleus dopaminergic denervation frequency increased in those with severe cognitive impairment (χ2=12.8, P=0.012). Cortical cholinergic denervation frequency increased monotonically from 24.7% in the minimally affected group to 85.7% in the most severely affected group (χ2=23.2, P=0.0001; figure 1). The frequency of subjects with thalamic cholinergic denervation did not increase significantly across the range of cognitive impairment (χ2=3.39; P=0.50).

Figure 1. Frequency of neocortical cholinergic deficits across cognitive spectrum.

The relative frequencies of significant neocortical cholinergic deficits in consecutive 0.5 Z-score ranges of cognitive impairment based on global cognitive z-scores ranging from no or minimal (Z>−0.5) to more severe cognitive impairment (Z≤ −2) in a cohort of predominantly non-demented PD subjects (n=143). Abbreviations: AChE, acetylcholinesterase.

Combined dopaminergic and cholinergic deficits

Table 2 shows the relative frequencies of combinations of significant caudate nucleus dopaminergic and neocortical cholinergic deficits in the different cognitive severity subgroups. The combined presence of caudate nucleus dopaminergic and neocortical cortical cholinergic deficits increased from 14.8% to 71.4% across the spectrum of cognitive impairment (total model χ2=37.0, P=0.0002).

Table 2.

Frequency listing of the four different combinations of presence or absence of significant caudate nucleus dopaminergic and neocortical cholinergic deficits in cognitive severity subgroups ranging from no or minimal (Z >−0.5) to more severe cognitive impairment (Z ≤ −2). Statistical significance for the distribution differences for the four possible combinations of presence or absence of the two neurochemical deficits between the 5 cognitive sub-groups is listed in the right column.

| Combination of absence or presence of neurochemical deficits | Z-score ranges | Statistical significance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Z ≤ −2 cognitive sub-group (n=7) | Z in −1.5 to −2 range cognitive sub-group (n=11) | Z in −1.0 to −1.5 range cognitive sub-group (n=10) | Z in −0.5 to −1.0 range cognitive sub-group (n=26) | Z > −0.5 cognitive sub-group (n=88) | ||

| Abnormal caudate nucleus VMAT2 & abnormal neocortical AChE activity (total group: 40/142, 28.2%) | n=5 (71.4%) | n=8 (72.7%) | n=3 (30%) | n=5 (19.2%) | n=13 (14.8%) | χ2=37.80; P=0.0002 |

| Abnormal caudate nucleus VMAT2 & normal neocortical AChE activity (total group: 60/142, 42.3%) | n=0 (0%) | n=3 (27.3%) | n=2 (20%) | n=14 (53.9%) | n=33 (36.4%) | |

| Normal caudate nucleus VMAT2 activity & abnormal neocortical AChE activity (total group: 6/142, 4.2%) | n=1 (14.3%) | n=0 (0%) | n=2 (20%) | n=0 (0) | n=9 (10.2%) | |

| Normal caudate nucleus VMAT2 & normal neocortical AChE activity (total group: 36/142, 25.4%) | n=1 (14.3%) | n=0 (0%) | n=3 (30%) | n=7 (26.9) | n=34 (38.6%) | |

Post hoc analysis: interactive effects between caudate nucleus dopaminergic and cortical cholinergic degenerations

As the vast majority (40 out of 46, 87.0%) of subjects with neocortical cholinergic deficits also had caudate nucleus dopaminergic deficits (Table 2), we investigated possible interactive effects between these two degenerations and cognitive functions. Table 3 shows the findings of the multiple regression analysis performed with cognitive Z-scores as outcome parameters and absolute cortical [11C]PMP AChE activity levels and caudate nucleus [11C]DTBZ VMAT2 distribution volume ratios and their interaction term as regressors. The total model was significant for the global composite Z-score (F=7.51, P<0.0001) and showed not only independent cognitive predictions for caudate nucleus dopaminergic (F=7.25, P=0.008) and cortical cholinergic (F=7.50, P=0.007) degenerations but also a significant interaction effect (F=5.40, P=0.022). No significant additional effect for duration of disease was present in the multivariate regression models.

Table 3.

Results from regression analysis with the cognitive Z-scores as outcome parameters and the neocortical AChE activity levels and caudate nucleus VMAT2 distribution volume ratios and their interaction term as regressors.

| Outcome measure | Cortical acetylcholinesterase group effect | Caudate nucleus VMAT2 distribution volume ratio covariate effect | Interaction term | Total Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global composite Z-score | F=7.50, P=0.007 | F=7.25, P=0.008 | F=5.40, P=0.022 | F=7.51, P<0.0001* |

| Cognitive sub-domains | ||||

| Verbal learning Z-score | F=4.49, P=0.036 | F=4.30, P=0.04 | F=2.98, P=0.087 | F 6.0, P=0.002* |

| Executive functions Z-score | F=8.98. P=0.0032 | F=9.18, P=0.0029 | F=7.03, P=0.009 | F=7.38, P<0.0001* |

| Visuospatial function Z-score | F=0.73, P=0.40 | F=0.43, P=0.51 | F=0.37, P=0.55 | F=0.81, P=0.53 |

| Attention Z-score | F=5.88, P=0.016 | F=6.28, P=0.013 | F=4.63, P=0.034 | F=6.06, P=0.0002* |

Significant variable after Holm-Bonferroni correction.

Similar independent and interactive effects of caudate nucleus dopaminergic and cortical cholinergic denervation were seen for executive function and attention Z-scores. Independent effects of the two degenerations were also seen for verbal learning Z-scores but with a non-significant trend for the interaction term (Table 3). There was no predictive effect of either caudate nucleus dopaminergic or cortical cholinergic denervation on visuospatial Z-scores.

Discussion

Our findings show that substantial caudate nucleus dopaminergic denervation is common even in PD subjects with minimal or no cognitive impairment. Cortical cholinergic denervation, in contrast, is significantly less common in PD subjects with minimal cognitive impairment and becomes very frequent in PD subjects with greatest cognitive deficits. These data indicate that cortical cholinergic deficits are likely important contributors to the emergence of dementia in PD. Cortical cholinergic afferent degeneration, consequently, is probably a major process associated with progressive cognitive decline across the spectrum of cognitive impairment in PD. These results agree with prior cholinergic in vivo imaging and post-mortem studies showing that cortical cholinergic denervation can occur early in some subjects with PD but progressive and more extensive cortical cholinergic denervation is characteristic of PDD 3,4,22–26.

Although dopaminergic denervation of the caudate nucleus and fronto-limbic system alone may not be sufficient for the development of marked cognitive impairments in PD 3,24, it is notable that cortical cholinergic denervation occurs mainly in subjects with significant caudate nucleus dopaminergic denervation. Our post hoc regression analysis showed significant interaction effects with combined effects of these two degenerative processes implicating their contributions to worsening cognitive impairment in PD, indicating that caudate nucleus dopaminergic and cortical cholinergic deficits may contribute to cognitive impairment in PD both additively and multiplicatively. A recent rat study evaluated cognitive effects of either selective dopaminergic denervation of the rodent homologue of the caudate nucleus and/or lesions of frontal cortical cholinergic afferents 27. Dual forebrain dopaminergic and cholinergic lesions induced greater deficits on a sustained attention test compared to effects of isolated lesions of either system alone 27. Isolated dopaminergic lesions actually enhanced attentional performance. As attentional function in this behavioral paradigm is mediated by cortical cholinergic afferents, this result suggests that caudate homologue dopaminergic denervation induces compensatory over-activity of cortical cholinergic afferents. These observations suggest that dual dopaminergic-cholinergic lesions result in loss of attentional cognitive resources that compensate for cognitive deficits resulting from striatal dysfunction 28.

This model is supported by our data in that we found significant caudate nucleus dopaminergic denervation was present in about two thirds of subjects with essentially normal global cognition (global cognitive composite Z score greater than −0.5) but a high proportion of subjects with markedly impaired cognition (global cognitive Z score less than −2.0) had dual dopaminergic-cholinergic deficits. Also consistent with the model of enhanced cholinergically mediated attentional function compensating for caudate dopaminergic deficits are the results of our regression analysis demonstrating that attentional and executive functions, which are strongly influenced by cortical mechanisms, but not visuospatial function deficits, were strongly related to combined dopaminergic-cholinergic deficits. Relatively isolated impairment of a single neurotransmission system in PD (i.e., nigrostriatal denervation) may not lead to the development of significant cognitive impairments because of adaptive plasticity in other intact brain systems 28–30.

Attempts to reconcile the existence of multisystem degenerations and cognitive impairments in PD have been dominated by models suggesting direct correlations between single neurochemical system changes and distinct cognitive deficits 31. These models are undoubtedly too simplistic. Our findings support more complex pathophysiological models of interacting dopaminergic and cholinergic degenerative changes producing cognitive dysfunctions in PD 28,31.

Our results are relevant also to evaluating the “dual syndrome” hypothesis of Kehagia ed,t al. which posits early executive deficits secondary to fronto-striatal system dysfunction driven by caudate dopaminergic denervation and later more global deficits due to multiple pathologies, including cholinergic system degeneration, affecting more posterior cortices. Our results, however, are more consistent with cholinergic deficits exacerbating fronto-striatal dysfunction due to loss of compensatory frontal cortical attentional functions, perhaps resulting in additional dysfunctional cortico-striate signaling 28. This interpretation is also more consistent with recent findings that cholinergic afferents are relatively enriched in frontal cortices 32.

A limitation of our study is its cross-sectional design which lacks longitudinal information about the rate of conversion to dementia and lack of inclusion of more severely demented patients (in whom commonly prescribed use of cholinesterase inhibitor drug therapy precluded participation in the present study). Another limitation is that our monoaminergic PET ligand is not suited to assess extra-striatal mesofrontal or limbic changes. The lack of visuospatial function findings in our study may be related to differences in cognitive test battery between our and other studies 2. Our study included more men than women. It is possible that gender differences in PD incidence and age of onset may be due to the possible neuroprotective effects of estrogens PD 33. Such as possiblity, however, would not be expected to affect a relative difference of degree of denervation between the dopaminergic versus the cholinergic systems in individuals who already have PD.

Finally, we did not assess other a-synucleinopathy associated processes, such as degeneration of noradrenergic projections or cortical a-synucleinopathy that likely contribute to impaired cognition in PD 34.

The heterogeneous basis of cognitive deficits in PD suggests multiple, complementary approaches to symptomatic treatment. Our data provide good rationale for improved cholinergic augmentation therapy in PD subjects with cognitive symptoms. We conclude that caudate nucleus and cortical cholinergic deficits contribute to cognitive impairment in PD, not only in an additive but also in a synergistic fashion.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all patients for their time commitment and research assistants, PET technologists, cyclotron operators, and chemists, for their assistance with the study. This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs [grant number I01 RX000317]; the Michael J. Fox Foundation; and the NIH [grant numbers P01 NS015655 and RO1 NS070856]. None of these funding agencies had a specific role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Dr. Bohnen, who conducted and is responsible for the data analysis, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Abbreviations

- AChE

Acetylcholinesterase

- DTBZ

dihydrotetrabenazine

- PD

Parkinson disease

- PDD

Parkinson disease with dementia

- PET

positron emission tomography

- PMP

methyl−4-piperidinyl propionate

- VMAT2

vesicular monoamine transporter type 2

Footnotes

Disclosure/conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest relevant to this work.

Author contributions:

Dr. Bohnen: Obtained funding; study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation; manuscript preparation.

Dr. Albin: Analysis and interpretation; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Dr. Muller: Acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Dr. Petrou: Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Dr. Kotagal: Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Dr. Koeppe: Acquisition of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; study supervision.

Dr. Scott: Acquisition of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; study supervision.

Dr. Frey: Obtained funding; acquisition of data; study supervision; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Disclosures

Dr. Bohnen has research support from the NIH, Department of Veteran Affairs, and the Michael J. Fox Foundation.

Albin serves on the editorial boards of Neurology, Experimental Neurology, and Neurobiology of Disease. He receives grant support from the National Institutes of Health, CHDI, Michael J. Fox Foundation, and the Dept. of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Albin serves on the Data Safety and Monitoring Boards of the TV7820-CNS-20002 trial.

Dr. Muller has research support from the NIH, Michael J. Fox Foundation and the Department of Veteran Affairs.

Dr. Petrou has research support from the Radiological Society of North America.

Dr. Kotagal has research support from the American Academy of Neurology Clinical Research Training Fellowship.

Dr. Koeppe receives research support from NIH (NINDS, NIA).

Dr. Scott receives Editorial Royalties from Wiley, is an owner of SynFast Consulting, LLC, and has received research funding from the University of Michigan, GE Healthcare, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Bayer Pharma AG, Eli Lilly, and Molecular Imaging Research.

Dr. Frey has research support from the NIH, GE Healthcare and AVID Radiopharmaceuticals (Eli Lilly subsidiary). Dr. Frey also serves as a consultant to AVID Radiopharmaceuticals, MIMVista, Inc, Bayer-Schering and GE healthcare. He also holds equity (common stock) in GE, Bristol-Myers, Merck and Novo-Nordisk.

References

- 1.Williams-Gray CH, Foltynie T, Brayne CE, Robbins TW, Barker RA. Evolution of cognitive dysfunction in an incident Parkinson’s disease cohort. Brain. 2007 Jul;130(Pt 7):1787–1798. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kehagia AA, Barker RA, Robbins TW. Cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: the dual syndrome hypothesis. Neurodegener Dis. 2013;11(2):79–92. doi: 10.1159/000341998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein JC, Eggers C, Kalbe E, et al. Neurotransmitter changes in dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson disease dementia in vivo. Neurology. 2010 Mar 16;74(11):885–892. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d55f61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohnen NI, Kaufer DI, Ivanco LS, et al. Cortical cholinergic function is more severely affected in parkinsonian dementia than in Alzheimer disease: an in vivo positron emission tomographic study. Arch Neurol. 2003 Dec;60(12):1745–1748. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.12.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohnen NI, Mueller MLTM, Kotagal V, et al. Heterogeneity of cholinergic denervation in Parkinson disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32(8):1609–1617. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frey KA, Koeppe RA, Kilbourn MR, et al. Presynaptic monoaminergic vesicles in Parkinson’s disease and normal aging. Ann Neurol. 1996;40:873–884. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bohnen NI, Albin RL, Koeppe RA, et al. Positron emission tomography of monoaminergic vesicular binding in aging and Parkinson disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006 Jan 18;26:1198–1212. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Kilford L, Lees AJ. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: a clinicopathologic study of 100 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992;55:181–184. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.3.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goetz CG, Poewe W, Rascol O, et al. Movement Disorder Society Task Force report on the Hoehn and Yahr staging scale: status and recommendations. Mov Disord. 2004 Sep;19(9):1020–1028. doi: 10.1002/mds.20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goetz CG, Fahn S, Martinez-Martin P, et al. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): Process, format, and clinimetric testing plan. Mov Disord. 2007 Nov 17;22:41–47. doi: 10.1002/mds.21198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aarsland D, Bronnick K, Larsen JP, Tysnes OB, Alves G. Cognitive impairment in incident, untreated Parkinson disease: the Norwegian ParkWest study. Neurology. 2009 Mar 31;72(13):1121–1126. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000338632.00552.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, Ober BA. California Verbal Learning Test Manual, Adult Version. 2. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wechsler D. WAIS III Technical Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delis DC, Kaplan E, Kramer JH. Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS): Examiner’s manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J Exp Psychol. 1935;18:643–662. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benton AL, Varney NR, Hamsher K. Judgment of Line Orientation, Form V. Iowa City: University of Iowa Hopsitals; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shao X, Hoareau R, Hockley BG, et al. Highlighting the Versatility of the Tracerlab Synthesis Modules. Part 1: Fully Automated Production of [F]Labelled Radiopharmaceuticals using a Tracerlab FX(FN) J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 2011 May 30;54(6):292–307. doi: 10.1002/jlcr.1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koeppe RA, Frey KA, Kume A, Albin R, Kilbourn MR, Kuhl DE. Equilibrium versus compartmental analysis for assessment of the vesicular monoamine transporter using (+)-alpha-[11C]dihydrotetrabenazine (DTBZ) and positron emission tomography. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997 Sep;17(9):919–931. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199709000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagatsuka S, Fukushi K, Shinotoh H, et al. Kinetic analysis of [(11)C]MP4A using a high-radioactivity brain region that represents an integrated input function for measurement of cerebral acetylcholinesterase activity without arterial blood sampling. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001 Nov;21(11):1354–1366. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200111000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Logan J, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Ding YS, Wang GJ, Alexoff DL. A strategy for removing the bias in the graphical analysis method. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:307–320. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200103000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bohnen NI, Muller ML, Koeppe RA, et al. History of falls in Parkinson disease is associated with reduced cholinergic activity. Neurology. 2009 Nov 17;73(20):1670–1676. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c1ded6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuhl D, Minoshima S, Fessler J, et al. In vivo mapping of cholinergic terminals in normal aging, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1996;40:399–410. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shinotoh H, Namba H, Yamaguchi M, et al. Positron emission tomographic measurement of acetylcholinesterase activity reveals differential loss of ascending cholinergic systems in Parkinson’s disease and progressive supranuclear palsy. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:62–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hilker R, Thomas AV, Klein JC, et al. Dementia in Parkinson disease: functional imaging of cholinergic and dopaminergic pathways. Neurology. 2005 Dec 13;65(11):1716–1722. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000191154.78131.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruberg M, Rieger F, Villageois A, Bonnet AM, Agid Y. Acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase in frontal cortex and cerebrospinal fluid of demented and non-demented patients with Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res. 1986;362:83–91. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91401-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi SH, Jung TM, Lee JE, Lee SK, Sohn YH, Lee PH. Volumetric analysis of the substantia innominata in patients with Parkinson’s disease according to cognitive status. Neurobiol Aging. 2012 Jul;33(7):1265–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kucinski A, Paolone G, Bradshaw M, Albin RL, Sarter M. Modeling fall propensity in Parkinson’s disease: deficits in the attentional control of complex movements in rats with cortical-cholinergic and striatal-dopaminergic deafferentation. J Neurosci. 2013 Oct 16;33(42):16522–16539. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2545-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarter M, Albin RL, Kucinski A, Lustig C. Where attention falls: Increased risk of falls from the converging impact of cortical cholinergic and midbrain dopamine loss on striatal function. Exp Neurol. 2014 May 5;257C:120–129. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bohnen NI, Frey KA, Studenski S, et al. Gait speed in Parkinson disease correlates with cholinergic degeneration. Neurology. 2013 Sep 27;81(18):1611–1616. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a9f558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Schouwenburg MR, O’Shea J, Mars RB, Rushworth MF, Cools R. Controlling human striatal cognitive function via the frontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2012 Apr 18;32(16):5631–5637. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6428-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calabresi P, Picconi B, Parnetti L, Di Filippo M. A convergent model for cognitive dysfunctions in Parkinson’s disease: the critical dopamine-acetylcholine synaptic balance. Lancet Neurol. 2006 Nov;5(11):974–983. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70600-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petrou M, Frey KA, Kilbourn MR, et al. In vivo imaging of human cholinergic nerve terminals with (−)-5-(18)F-fluoroethoxybenzovesamicol: biodistribution, dosimetry, and tracer kinetic analyses. J Nucl Med. 2014 Mar;55(3):396–404. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.124792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodriguez-Perez AI, Valenzuela R, Villar-Cheda B, Guerra MJ, Lanciego JL, Labandeira-Garcia JL. Estrogen and angiotensin interaction in the substantia nigra. Relevance to postmenopausal Parkinson’s disease. Exp Neurol. 2010 Aug;224(2):517–526. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Halliday GM, Leverenz JB, Schneider JS, Adler CH. The neurobiological basis of cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2014 Apr 15;29(5):634–650. doi: 10.1002/mds.25857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]