Abstract

Aims and objectives

In this critical literature review, we examine evidence-based interventions that target sexual behaviours of 18- to 25-year-old emerging adult women.

Background

Nurses and clinicians implement theory-driven research programmes for young women with increased risk of HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted infections. Strategies to decrease transmission of HIV and sexually transmitted infections are rigorously evaluated and promoted by public health agencies such as the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. While many interventions demonstrate episodic reductions in sexual risk behaviours and infection transmission, there is little evidence they build sustainable skills and behaviours. Programmes may not attend to contextual and affective influences on sexual behaviour change.

Design

Discursive paper.

Methods

We conducted a conceptually based literature review and critical analysis of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s best-evidence and good-evidence HIV behavioural interventions. In this review, we examined three contextual and affective influences on the sexual health of emerging adult women: (1) developmental age, (2) reproduction and pregnancy desires and (3) sexual security or emotional responses accompanying relationship experiences.

Results

Our analyses revealed intervention programmes paid little attention to ways age, desires for pregnancy or emotional factors influence sexual decisions. Some programmes included 18- to 25-year-olds, but they made up small percentages of the sample and did not attend to unique emerging adult experiences. Second, primary focus on infection prevention overshadowed participant desires for pregnancy. Third, few interventions considered emotional mechanisms derived from relationship experiences involved in sexual decision-making.

Conclusions

Growing evidence demonstrates sexual health interventions may be more effective if augmented to attend to contextual and affective influences on relationship risks and decision-making. Modifying currently accepted strategies may enhance sustainability of sexual health-promoting behaviours.

Keywords: emotional aspects, HIV/AIDS, literature review, sexual health, sexuality

Introduction

The number of strategic choices for a woman to maintain her sexual health is limited. A primary focus of sexual health research is on prevention of unintended outcomes such as HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) that affect broad sections of the global population. Nurses and clinicians advocate that women engaged in sexual relationships with men: (1) abstain from sexual intercourse, (2) negotiate for condom use with their male partners, (3) maintain one sexual partner with the hope that their chosen partner is uninfected and also monogamous and/or (4) if sexually active, undergo regular screening for sexual infections (Ehrhardt et al. 2002). These recommendations are embedded in evidence-based intervention studies designed to reduce infection incidence and sexual risk behaviours. Nurses working in clinical and community settings are well positioned to deliver evidence-based interventions to individuals and groups most affected by unintended sexual health outcomes.

In the USA, national priorities for improving sexual health are guided by morbidity and mortality statistics. Thus, researchers develop interventions to target subpopulations with disproportionate unintended outcomes according to race, gender, age and sexual behaviours (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention 2010a,b). Programmes designed to encourage behavioural changes are theory-based and evidence-based. These programmes also attend to cultural and social contexts of an intended group to enhance their applicability and efficacy (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention 2012). In this study, we refer to context as the components of sexual health discourse that shape scientific understanding of its meaning. For example, individual sexual health is influenced by cultural and social determinants including, but not limited to, ethnicity, nationality, religion, age, developmental maturity and family structure (World Health Organization 2006). Additionally, emotions or affect influences individual interpretations of relationship experiences and shapes sexual decisions (Higgins & Hirsch 2007).

We use the USA as an exemplar to demonstrate the systematic framing of sexual health for a group of young women that experience high numbers of sexually related morbidities. Globally, young women experience greater biological risk of HIV transmission, and interventions should be tailored to fit the cultural context of the region. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) apply rigorous standards and promote interventions with scientific efficacy at individual, group and community levels. However, rates of HIV continue to increase, especially among emerging adult women (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention 2008, 2010a,b). Sexual contact with male partners accounts for the most prominent driver of HIV transmissions among young women in the USA (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention 2010a,b).

Investigations about sexual development and experiences during the emerging adult years are rare (Tanner et al. 2009). When included in studies, young adults are seldom targeted as an isolated cohort. This group has distinct, contextually bound developmental needs and sexual experiences that influence ways they operationalise sexual safety and sexual security in their relationships (Alexander, K. University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, unpublished results; Alexander, K. University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, unpublished results). In this study, we critically analysed the HIV intervention literature specific to the USA to find whether these concepts were included in publications.

Sexual security describes how individuals use emotions drawn from past relationship experiences to influence future sexual decisions (Davies & Cummings 1994, Alexander, K University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 2012). Emerging adult women interpret sexual security as they begin to form longer-lasting sexual partnerships (Tanner et al. 2009). Thus, their emotions provide a road map for making sexual decisions and may be influenced by feelings ranging from happiness and joy to sadness and despair. Challenging periods of extreme vulnerability often accompany these emotional peaks and valleys. Some individuals may lack insight about ways emotions influence their judgment and sexual decision-making (Alexander K, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 2012). These definitions provided a framework for conducting this review.

Background

Individuals develop sexual behaviours and make decisions based on relationship experiences that are formed within a complex set of physical, cultural and social circumstances. Yet, sexual health nurses tend to measure the success of intervention approaches around discrete individual behavioural risks of HIV/AIDS (Bourne & Robson 2009). Outcomes measured in interventions examine sexual health as episodic events, and sexual decisions are dichotomised as positive or negative (Naisteter & Sitron 2010). After intervention, nurses evaluate sexual behaviour changes through participants’ self-report of increasing condom use and negotiation, limiting numbers of partners and increased frequency of screening for infections. To further support women in reaching optimal sexual health, intervention programmes focus on skill-building techniques that women can transfer to their everyday lives (Sales et al. 2008). However, sexual health intervention research is rarely conducted using longitudinal designs >12 months; therefore, clinicians may see only episodic effects on sexual decision-making as they implement programmes (Coates et al. 2008).

Sexual health programmes use several theoretical approaches to design interventions such as social-cognitive, transtheoretical, AIDS risk reduction and health belief model (Ehrhardt et al. 2002, Kershaw et al. 2009, Diallo et al. 2010). Clinicians promote skillbuilding around condom use by using demonstrations and information sharing (Miller et al. 2000, Baker et al. 2003, Melendez et al. 2003, DiClemente et al. 2004, Jemmott et al. 2007, Corneille et al. 2008). Teaching condom negotiation through innovative communication techniques is also prevalent in programme curricula (Shain et al. 1999, Miller et al. 2000, Ehrhardt et al. 2002, Melendez et al. 2003, Peragallo et al. 2005, Jemmott et al. 2007, Thurman et al. 2008). Effective interventions should be comprehensive in their approach, incorporating cognitive, affective and behavioural self-management skills (Rotheram-Borus et al. 2009). Hence, sole emphasis on cognitive approaches to sexual health promotion may discount affective ways in which individuals make sexual decisions and downplay the social experiences women bring to relationships.

Emerging adulthood

Emerging adulthood is a recognised developmental stage that includes individuals 18–25 years old (Arnett 2000). Marked by age-specific cognitive and affective changes that occur during this period, emerging adults experience important life transitions from adolescence to adulthood. They develop intimate relationships and discover sexual experiences at an often rapid pace; attitudes and beliefs about mature intimacy are beginning to form; and individuals seek relationship experiences that endure longer and have a deeper quality (Tanner et al. 2009). The emerging adult brain rearranges to accommodate for integration of cognitive and emotional growth towards more rational decision-making (Tanner et al. 2009).

This period is distinguished from adolescence and older adulthood in several ways. While the sexual partnerships of adolescents may last several weeks, those of emerging adults tend to endure several months with a focus on physical and emotional intimacy (Arnett 2000). In contrast, adolescents have greater difficulty with emotion regulation, and older adults have increased capacity for monitoring their own behaviour (Tanner et al. 2009). These new cognitive abilities and affective responses influence sexual decision-making and are unique to this developmental age (Byno et al. 2009, Tyson 2011). In this period of transition, enhanced opportunities for vulnerability to unintended sexual health outcomes may occur and may influence future pathways towards sexual health over the life course (Meier & Allen 2008).

Reproduction and pregnancy desires

Seventy-five per cent of young people in the USA report having sex by the age of 20 (Finer 2007). Therefore, childbearing and pregnancy are predictive outcomes of sexual relationships between young men and women. During the transition between adolescence and emerging adulthood, many young women’s pregnancy intentions change. More emerging adult women have childbearing desires compared with adolescents. Although over half of those women that experience pregnancy during emerging adulthood did not intend to do so, there are large numbers of women in this age group who do wish to reproduce (Finer & Henshaw 2006).

Pregnancy intention is culturally influenced by racial/ethnic identity and social class positions (Edin & Kefalas 2011). While on average more women in the USA are delaying childbearing until their late twenties, some desire and experience pregnancy at earlier ages. For example, Black and Hispanic women tend to have children at younger ages (22·7 and 23·1, respectively) as compared to Whites (26; Centers for Disease Control 2006). Therefore, desires for children among emerging adult women may be more common than we think. Additionally, Black and Hispanic women are groups most affected by sexual health disparities. Thus, pregnancy desires among these young women may supersede fears of HIV/STI transmission (Cochran & Mays 1993, Guthrie et al. 2010). Approaches to relationship development and sexual health may also be affected during this period as young women in their early 20s begin to have children and, thus, experience burdens related to parenting responsibilities (Tanner et al. 2009, Tyson 2011).

A desire to reproduce creates a confounding dilemma for infectious disease prevention programming and research. Although a variety of barrier and contraceptive methods exist, there are none that facilitate pregnancy while simultaneously protecting from infection transmission (Higgins et al. 2009). While many studies examine fertility prevention, desires and contraceptive use, they are overwhelmingly performed in adolescent populations or with women living with HIV/AIDS who tend to be older (Finocchario-Kessler et al. 2010). Few interventions targeting adult women address sexual health in a comprehensive manner; instead, interventions tend to target one unintended outcome at a time – HIV/STI or pregnancy (Finocchario-Kessler et al. 2010). This separation of focus is also notably distinguished by age group. Research targeting adolescents within school-based or clinical interventions tends to address behaviours that prevent both pregnancy and HIV/STI (Kirby & Laris 2009, Jemmott et al. 2010, Markham et al. 2011).

Sexual security and relationship experiences

Emotions, or affect, are important drivers of sexual activity and decision-making (Loewenstein & Lerner 2003). Varying levels of emotional distress affect high-risk behaviours (Sterk et al. 2006, Higgins et al. 2008, Tyson 2011). Researchers find that emotions such as love, pleasure and arousal affect perceptions of safety and uptake of condom or contraceptive use (Ariely & Loewenstein 2006, Higgins 2008, Corbett et al. 2009). Efforts to approach sexual health promotion in a more comprehensive manner include framing new perspectives of emotional processes in HIV/AIDS prevention (Marazzo et al. 2005, Harrison 2008) and contraceptive research (Nelson & Shields 2005, Higgins & Hirsch 2007).

Sexual security indicates the patterned, affective sense of being that undergirds ways individuals approach sexual relationships over time. This concept describes how young women feel in relationships and shapes sexual behaviours (Alexander, K. University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 2012). Often, enactment of safety behaviours, such as condom or contraceptive use, is a cognitive decision influenced by the individual’s affective state of sexual security (Ariely & Loewenstein 2006, Higgins et al. 2008). People are often in flux between states of security and insecurity depending on meanings attached to relationships and sexual experiences. Emerging adult women, in contrast to men, tend to make decisions to bring them closer to sexual security because they approach sexual activity in terms of intimacy, emotion and commitment (Knox et al. 2001).

Comprehensive intervention strategies

Some sexual health researchers recognise that safety strategies may be broader than condom use and are influenced by affective factors at multiple levels. They incorporate strategies that evoke gender and racial/ethnic pride, community caregiving and personal relationship strengthening (Miller et al. 2000, Ehrhardt et al. 2002, DiClemente et al. 2004, Shain et al. 2004). These approaches provide foundational messages for changing sexual health behaviours. Emerging adult women, however, continue to experience higher rates of sexually related consequences (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention 2012). Thus, this broader strategy is still incomplete, and nurses should consider that uptake and sustainability of healthy sexual behaviours may be influenced by a myriad of different situations and experiences (Cochran & Mays 1993, Wyatt et al. 2008).

In this literature review, we critically analysed the characteristics of best- and good-evidence HIV interventions that target emerging adult women. We examined these investigations to understand whether three factors were present in the published literature. The following broad research question framed our analysis of the literature: In what ways do researchers attend to the contextual and affective components of sexual activity to promote sexual health among emerging adult women? Specifically, we were interested in the following factors that influence sexual decision-making behaviours:

Developmental age.

2 Reproduction and pregnancy desires.

3 Sexual security and relationship experiences.

We were interested in understanding ways sexual health researchers develop intervention programmes to arm young women participants with health-promoting skills that will persist throughout the emerging adulthood transition.

Methods

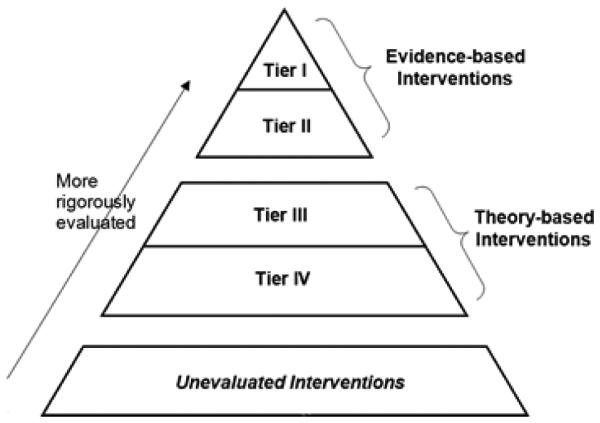

We performed a review and critical analysis of CDC’s best-evidence and good-evidence HIV behavioural interventions. The review included published, peer-reviewed studies with a demonstrated level of quality and strong research findings according to specific criteria of the CDC. The Prevention Research Synthesis Project (PRS) of the CDC applies rigorous standards to empirically based interventions (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention 2012). The efficacy review process of the PRS includes systematic procedures to identify ‘best’ and ‘good’ evidence-based interventions. Interventions meeting these criteria are considered to advance the fight against high HIV transmission incidence and could result in tangible behaviour change. Using a ‘Tiers of Evidence’ pyramid framework, reviewers classify the interventions as evidence-based or theory-based. This continuum of evaluation establishes a range for intervention strength. Evidence-based interventions reside at the top of the pyramid and are classified as Tiers I and II. They are most likely established from the research literature and are more rigorously evaluated. Tier III and IV interventions are developed from theory-based scientific knowledge but lack sufficient empirical evidence to satisfy the CDC criteria for ongoing evaluation and promotion (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention 2012, Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Tiers of evidence table: a framework for classifying HIV behavioural interventions (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention 2012).

In this study, we reviewed interventions targeted towards individuals, groups and entire communities. Inclusion criteria for this review were as follows: (1) research performed in the USA; (2) study sample included participants aged 18–25 years and ≥ 40% women; (3) research participants spoke English; (4) targeted women engaged in sex with men; and (5) primary source was peer-reviewed. Intervention studies were excluded if they targeted drug-using behaviours or were delivered at the community level only, with no individual measurements. We excluded these investigations because while several studies that aimed to change drug-using behaviours also incorporated sexual behaviour change messaging, this was not their primary focus. Furthermore, some community-level interventions were excluded because units for analysis did not include outcomes derived from interpersonal exchanges.

The CDC identified 74 best- and good-evidence HIV risk reduction interventions from the published or in press literature as of 12 August 2011 (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention 2012). Critical analyses of each intervention’s published content in peer-reviewed journals were included in this review. However, this investigation is limited because we were unable to obtain the full curricula used to implement each intervention. Interventions were often described in more than one article from a group of authors. In this case, primary findings articles that described the intervention activities in greatest detail were reviewed. We approached the literature asking the following questions about the content of each intervention: (1) Are factors of developmental age accounted for in the curriculum? (2) How are reproduction and pregnancy desires approached by the intervention? and (3) Are affective approaches to decision-making, such as sexual security and meanings of previous relationship experiences, attended to in the intervention? Each article was read three times by the primary author. The first time, articles were analysed for relevance to the research study questions and adherence to inclusion criteria. The second reading accounted for the overall aims of the study and content of the curricula. Finally, the third reading confirmed that information gleaned from the first two readings was accurate and supported our thesis. After each step, all authors contributed to the conceptualisation of findings within a consistent framework.

Results

Seventeen interventions met the inclusion criteria for review in this analysis. Although there were 46 interventions with large samples of adult women, 29 were excluded because the mean age (including standard deviations) of the sample was significantly older or younger than 18–25 years old or less than 25% of their sample fell into the target age group. Some articles provided greater detail about the curriculum and focus of the intervention than others. All were theoretically based, and many described formative research activities that supported intervention development. In Table 1, we provide brief descriptions of the study interventions according to variables of this literature review.

Table 1.

Reviewed evidence-based interventions

| Best-evidence interventions |

Lead author |

Year | Samplesize/ description |

Outcome variables |

Pregnancy/ reproduction component |

Relationship experience component |

Developmental age component |

Sexual security component |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centering Pregnancy Plus |

Kershaw | 2009 |

n = 1047 14–25 years Mean age = 20·4 100% F |

↓Repeat pregnancy ↓risk behaviours ↓sexually transmitted infections (STI) ↓psychosocial risk |

Yes | No | Yes Compared adolescent outcomes to young adults |

No |

| CHOICES | Baker | 2003 |

n = 229 Mean age = 29·5 100% F |

↓STI ↓risky sex acts |

No | Yes – developing healthy relationships with low-risk men |

No | Yes – identifying triggers for unsafe sex |

| Communal effectance–AIDS prevention |

Hobfoll | 2002 |

n = 935 16–29 years Mean age = 21·42 100% F |

↑Condom use ↓# sex partners ↓STI ↑preventive psychosocial/ structural factors |

No | No | No | Yes – externally – to identify partner’s feelings, needs |

| Female condom (FC) skills training |

Choi | 2008 |

n = 409 18–39 years 100% F Mean age = 22 77% = 18–24 years |

↑Use of FC ↑any condom use |

Yes – excluded pregnant or desiring women |

No | No | Yes – pleasure or displeasure from condom use |

| Future Is Ours (FIO) | Ehrhardt | 2002 |

n = 360 18–30 years Mean age = 22·26 100% F |

↓Unprotected sex ↑condom use ↑outercourse ↑refusal of risky sex |

Yes – excluded pregnant or desiring women included information about staying safe and becoming pregnant at the same time |

Yes | No | Yes – externally; feelings about relationships, personal vulnerability; pleasure |

| Project ‘LIGHT’ | NIMH Multisite HIV Prevention Trial Group |

1998 |

n = 3706 Ages 18+ <25% = 25 years |

↓STI ↓risk behaviours ↑self-efficacy and problem- solving skills for safe sex |

No | No | No – large age variation |

Perhaps – identifying trigger for risk |

| RESPECT: Brief counselling |

Kamb | 1998 |

n = 5758 Ages 14+ 43% F |

↓STI ↓sex risk behaviours |

No | No | No | No |

| RESPECT: Brief counselling + booster |

Metcalf | 2005 |

n = 3297 Ages 15–39 Mean age = 26 46% F |

↓STI ↓#partners ↓sex w untreated partners |

No | No | No | No |

| SAFE (standard version) |

Shain | 1999 |

n = 775 15–45 years Mean age = 21 100% F; 80% < 25 years |

↓STI ↓#partners |

Yes – emphasis reproductive age |

No | No | Yes – misplaced trust; ↓self-esteem Prevention of loss |

| Sister-to-sister: one-on-one skills-building and group skills-building |

Jemmott | 2007 |

n = 564 100% F 18–45 years Mean age = 27 |

↓STI ↓ unprotected sex ↑condom use |

Yes – excluded ppts if pregnant but included those potentially desiring pregnancy (Shain et al. 2004, 401–408, Choi et al. 2008, 1841–1848) |

No | No | No |

| WiLLOW | Wingood | 2004 |

n = 366 Ages 18–50 50% < 35 years HIV+ 100% F |

↓Unprotected sex ↑condom use |

No | No | No | Yes – network emotional support assessed |

|

| ||||||||

| Good-evidence interventions |

Lead author |

Year | Sample size/ description |

Outcome variables |

Pregnancy/ reproduction component |

Relationship experience component |

Developmental age component |

Sexual security component |

|

| ||||||||

| Condom promotion |

Bryan | 1996 |

n = 198 Mean age = 18·6 100% F |

↑Increased condom use intentions ↑condom use |

No | No | No | No |

| Healthy love | Diallo | 2010 |

n = 313 18–69 years Mean age = 31·6 100% F |

↑Condom use ↓# sex partners ↓# unprotected sexual encounters |

Yes – excluded ppts if pregnant/desiring pregnancy |

Yes – risk assessment based on past behaviours |

No | Yes – potential for internalised sexual oppression |

| Insights | Scholes | 2003 |

n = 1210 Mean age = 21 years 48% 18–21; 52% 21–24 100% F |

↑Condom use | Yes – excluded for pregnancy tailored intervention to account for ppt having children |

No | No | No |

| Real AIDS Prevention Project (RAPP) |

Lauby | 2000 |

n = 3722 Mean age = 25 15–34 years 100% F |

↑Condom use | Yes – emphasised recruitment of childbearing aged women; no discussion in intervention |

No | No | No |

| RESPECT: Enhanced counselling |

Kamb | 1998 |

n = 5758 Ages 14+43% F |

↓STI ↓sex risk behaviours |

No | No | No | No |

| Salud, Educacion, Prevencion, y, Autocuidado (SEPA) |

Peragallo | 2005 |

n = 454 18–44 years 27% = 18–25 years 100% F |

↓STI ↓sex risk behaviours |

No | No | No | Yes – trust and fear r/t partner, condom use |

Developmental age

We found no interventions targeted exclusively to adults in emerging adulthood. Age ranges varied widely encompassing ages 14–25, overlapping adolescence and emerging adulthood, or adults between ages 18–69. Mean ages of study participants, when documented in the article, ranged from 18·6 (SD = 1·23; Bryan et al. 1996) to 31·3 (SD = 11·6; Diallo et al. 2010). Discussions including age-specific developmental strategies to approach emerging adult women were not evident. However, Kershaw et al. (2009) analysed behavioural results from the Centering Pregnancy Plus intervention according to age groups. They found that young women aged 15–19 had decreased STI incidence postintervention. Conversely, their older counterparts aged 20–25 showed no change in rates of infection (Kershaw et al. 2009). Follow-up periods for postintervention effects ranged from three months to three years postintervention, although the majority of interventions lasted six months to one year. Mean age at first sexual intercourse was used as a sample descriptive variable in two studies (Bryan et al. 1996, Jemmott et al. 2007). Many researchers described participant samples using numbers of sex partners prior to study entry (Bryan et al. 1996, Shain et al. 1999, Lauby et al. 2000, Ehrhardt et al. 2002, Hobfoll et al. 2002, Scholes et al. 2003, Metcalf et al. 2005, Jemmott et al. 2007, Choi et al. 2008).

Reproduction and pregnancy desires

Overall, CDC interventions we reviewed for this study emphasised HIV/STI prevention separately from unintended pregnancy. Five studies included in this analysis used pregnancy or desire for pregnancy as exclusion criteria for research participation (Ehrhardt et al. 2002, Scholes et al. 2003, Jemmott et al. 2007, Choi et al. 2008, Diallo et al. 2010). Although Jemmott et al. (2007) excluded pregnant women, they conducted their intervention trial in a setting that served women wishing to get pregnant and included these women as eligible to participate in their study. One research article explicitly included information that promoted protected sex while balancing simultaneous fertility desires (Ehrhardt et al. 2002). Scholes et al. (2003) tailored their intervention to attend to the needs of participants with children. There were two studies that emphasised participant eligibility as contingent on childbearing status; however, they did not address competing fertility desires with condom use outcomes of the research (Lauby et al. 2000, Shain et al. 2004). Lauby et al. (2000) documented the numbers of participants who had experienced an unplanned pregnancy prior to study entry, although this was not an outcome variable of the study.

Sexual security and relationship experiences

Individual sexual security, or the affective processes occurring in sexual relationships, was a component of several intervention curricula. Through cognitive coping mechanisms, feelings of self-esteem and empowerment were evoked as strategies for changing sexual behaviours (Hobfoll et al. 2002, Baker et al. 2003, Wingood et al. 2004, Kershaw et al. 2009, Diallo et al. 2010). For example, stress management, maintenance of sexual self-control and recognition of high-risk behavioural ‘triggers’ presented avenues for behaviour change (NIMH Multisite HIV Prevention Trial Group 1998, Baker et al. 2003, Ickovics et al. 2007, Diallo et al. 2010). One intervention programme discussed feelings of guilt relating to sexual activity and ways to overcome it by assessing personal perceptions of sexuality (Bryan et al. 1996). Additionally, interventions addressed perceptions of vulnerability by presenting statistics and information to young women participants as a motivator for behaviour change (Bryan et al. 1996, Hobfoll et al. 2002, Diallo et al. 2010).

On an interpersonal level, women participants were encouraged to process their partners’ reactions to condom use negotiations and to identify feelings of anger and misplaced trust (Peragallo et al. 2005). Curricula also focused on unwanted advances and (re)gaining control in sexual situations by refusing sex, managing rejection and handling partner dissatisfaction with condom use (Bryan et al. 1996, Ehrhardt et al. 2002). Some researchers also assessed relationship satisfaction or encouraged healthy relationships with low-risk men as a precursor for changing behaviours (Shain et al. 2004).

Feelings of gender and racial/ethnic pride and awareness of sexual rights were promoted in several interventions targeting racial minority women (Ehrhardt et al. 2002, Jemmott et al. 2007). Triggering these feelings evoked communal effectance, encouraging participants to engage in protective activities by demonstrating care for themselves as well as for their families and communities. This provided a platform for showing respect for the neighbourhood where participants lived, the race with which they identified, and/or their (extended) families (Hobfoll et al. 2002, Wingood et al. 2004). Choi et al. (2008) incorporated emotional responses to understand participant evaluative feelings about delivery of the curricula or of a specific safety device such as the male or female condom or contraceptive.

Discussion

The CDC identified a diverse group of effective best- and good-evidence interventions designed to increase sexual safety behaviours in populations with the greatest unintended sexual health outcomes. In this conceptually based critical analysis, we identified several strengths and limitations to their potential for sustainable application over the course of women’s emerging adulthood.

Developmental age

Unique developmental relationship processes experienced by emerging adult women require particular attention from sexual health nurses (Byno et al. 2009). There continues to be a question of long-term sustainability for positive sexual health outcomes among emerging adult women. Sexual health interventions reviewed in this study tended to rely on constrained biological and behavioural definitions of safety. They accounted for self-reported condom use and negotiation, partner numbers, STI incidence or repeat pregnancy (e.g. Baker et al. 2003, Jemmott et al. 2007). However, reliance on skill-building (e.g. Shain et al. 1999, Scholes et al. 2003) as an episodic, cognitive approach to sustainable communication strategies and behaviours may downplay a natural process of learning and implementing new abilities successfully, especially during this life phase.

Nurse educators and researchers posit that learning occurs in phases, is complex, can be drawn out over a period of time and is informed by prior knowledge and experiences (Benner 1984, Shuell 1990). Obtaining optimal sexual health is a continuous process and should be approached from that perspective. In initial phases, individuals take in facts, make analytical decisions and maintain a detached commitment to the process. As the learning process proceeds through competency and proficiency, decisions become intuitive and contextual (Benner 1984, Shuell 1990). In many of the sexual health interventions reviewed, condom demonstrations and communication strategies aimed at enhancing skills (e.g. Kamb et al. 1998, Baker et al. 2003, Choi et al. 2008) comprised one or two sessions of the programme and were not revisited. Approaching this aspect of interventions through a model of learning may increase long-term effectiveness and applicability to the lives of emerging adult women.

We noted a relative lack of interventions with longitudinal designs lasting greater than one year. Thus, a research gap may exist to guide nurses about how to promote sexual safety behaviours over cumulative time and through relationship changes, especially in emerging adult women. Sexual health researchers often described participant samples using sociodemographic variables such as numbers of partners in the previous three months (e.g. Hobfoll et al. 2002, Metcalf et al. 2005). However, these categorisations may not sufficiently contextualise the young women’s sexual experiences. Partnership changes during emerging adulthood may occur as part of a healthy developmental process but also creates a unique position of biological vulnerability. These experiences can inform future personal approaches to sexual relationships and should be acknowledged as such. Emerging adult women are experiencing a time of self-discovery often characterised by instability; and changes in love partners are irregular and emotionally intense (Tanner et al. 2009).

Emerging adulthood is a period of evolution that is important to prevention research aimed at decreasing unintended sexual health outcomes. Emerging adult women are not relying solely on cognitive understandings of their sexual experiences (Galinsky & Sonenstein 2011, Johns et al. 2013). Age is related to changes in sexual attitudes, beliefs and behaviours. For example, with increasing age, Huerta-Franco and Malacara (1999) found that college women developed less permissive sexual attitudes. Further, Kershaw et al’s. (2009) findings of differences in STI incidence between younger and older participants in a cohort of young women elicit further questions about the influences of developmental age on sexual health outcomes. Exclusive focus on condom use and negotiation as an endpoint is imperfect and may cause clinicians to overlook some larger influences on the sexual decision-making of 18- to 25-year-old women.

Reproductive and pregnancy desires

Sexual relationships and decision-making between emerging adult women and their male partners are bound by racial, gender, class and geographic lines. These unique characteristics provide a foundation from which to examine sexual health-compromising outcomes among this population. Women in emerging adulthood may experience desires for pregnancy or burdens of caregiving that inform sexual decision-making (Tanner et al. 2009, Tyson 2011). High pregnancy rates among this age group may reflect that our understanding of pregnancy intention requires further exploration (Edin & Kefalas 2011). Developing attitudes and beliefs regarding sexuality may lead emerging adult women to perceive pregnancy as less risky, causing them to interpret childbearing as an avenue for building trust and commitment with a partner (Lefkowitz & Gillen 2006).

Sexual security and relationship experiences

Multilevel approaches that incorporated aspects of emotional processes for behaviour change strengthened several interventions analysed in this study (e.g. Hobfoll et al. 2002, Wingood et al. 2004, Jemmott et al. 2007). These strategies add to emerging discourse aimed at improving their efficacy (Schensul & Trickett 2009). Sexual health researchers attended to gender and racial influences on safety behaviours specific to Black and Latina women (e.g. Ehrhardt et al. 2002, Wingood et al. 2004). This provided a contextualised strategy for provoking behaviour change by acknowledging environmental influences on affective modes of sexual decision-making. Calling on feelings associated with shared community experiences provides recognition of the contextual nature of inequalities that shape definitions and perceptions of sexually related safety and risk. The emergence of social explanations with emotional underpinnings as determinants for poor sexual health outcomes provides evidence that researchers are considering broader ways to approach sexual health interventions.

Additionally, individual-level strategies built on relationship experiences provided a foundation on which to propose changes in sexual behaviour (e.g. Scholes et al. 2003, Diallo et al. 2010). Gaining information, limiting numbers of sex partners and increasing screening practices further supported self-efficacy and empowerment over health behaviours (e.g. NIMH Multisite HIV Prevention Trial Group 1998, Hobfoll et al. 2002, Metcalf et al. 2005). These strategies promoted healthy behaviours and support positive decisions. For example, women participants were encouraged to refuse unprotected sexual advances from male partners in conjunction with a personalised assessment for risk (Ehrhardt et al. 2002). A further strength was found in researchers’ focus on skill acquisition to contend with social, psychological and physical barriers to healthy sexual decision-making (e.g. Baker et al. 2003, Jemmott et al. 2007, Choi et al. 2008). While the overwhelming majority of studies focused on condom demonstration and practice on models to enhance cognitive mechanisms for skill-building, several sexual health researchers used affective strategies to increase sexual safety behaviours (e.g. NIMH Multisite HIV Prevention Trial Group 1998, Shain et al. 1999, Ehrhardt et al. 2002, Hobfoll et al. 2002, Baker et al. 2003, Wingood et al. 2004, Peragallo et al. 2005, Diallo et al. 2010). Integrating proficiencies for sexual safety behaviours across cognitive, affective and behavioural domains was important to the success of many reviewed interventions and is aligned with emerging research designed to enhance sexual health (Coates et al. 2008).

Interpersonal approaches to emotional processes were limited, and some focused on reactions to anger or encouraged refusal of sexual advances (e.g. Shain et al. 1999, Ehrhardt et al. 2002, Peragallo et al. 2005). Although discussions were narrow in scope, some interventions included approaches to managing positive feelings of emotional love, affection and pleasure (Ehrhardt et al. 2002, Choi et al. 2008, Diallo et al. 2010). Applying the concept of sexual security may provide a more balanced perspective to understanding the influence of these emotional drivers on sexual behaviours. Constrained, binary approaches that emphasise positive or negative responses to attachment between sexual partners are incomplete (Alexander, K. University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 2012).

Several descriptive studies have identified love as a key driver for sexual activity (Huerta-Franco & Malacara 1999, Warr 2001, Corbett et al. 2009). Additional emotional processes, such as desire, loneliness, and joy, which are not all positive, underpin sexual decisions and should also be incorporated into intervention approaches. Instead, researchers focused on cognitive-behavioural models of risk reduction and the harmful aspects of these emotions. These approaches downplay the evolving mind–body connection of young women transitioning from adolescence to adulthood (Tanner et al. 2009, Ghane & Sweeny 2013). As emerging adult women make sexual decisions and interpret diverse meanings of sexual security in their personal relationships, changes in attitudes and beliefs may influence future sexual relationship success (Alexander, K. University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 2012).

Limitations

There are several limitations to these research findings. Our review method may include some bias because the papers were reviewed by only the primary author. However, our review method was strengthened by conceptual interpretations of the data by each author during the review process. Additionally, we did not review the entire content of curriculum for each of the included studies. It is possible, therefore, that some pieces of the research questions were included in the intervention. However, we included primary papers in this review and outcome measures of the reviewed studies did not reflect an emphasis on the specific content of our research questions.

Conclusion

In summary, most evidence-based intervention models promoted by the CDC aimed to decrease contact with genital body fluids through improved condom use and improve condom negotiations. This approach potentially reifies scientific assumptions that emerging adult women should be fearful of sexual activity. In turn, clinicians and nurses might downplay lifelong sexuality processes such as pregnancy desires and sexual security that build on relationship experiences. Centring promotion messages and prevention strategies around one compartmentalised problem at a time may not address the full scope of individual lived experiences (Boyce et al. 2007, Kippax et al. 2013).

Nurses and researchers working with emerging adult women have a unique opportunity to serve as mentors and coaches during a period of rapid transition. Expanding interventions that currently focus solely on HIV/STI prevention to include comprehensive emotional processes of sexual security can begin life skill development for application in current and future relationships. Interventions and programmes that promote healthy sexual behaviours should aim to be inclusive, focusing on cognitive strategies that require rational decision-making and recognising that emerging adult women are influenced by affect and emotion.

Relevance to research and clinical practice

This review highlights several implications for designing and/or augmenting sexual health interventions currently used in clinical practice and in community settings. Targeted, age-specific approaches to address the unique needs of emerging adults are imperative to decrease high rates of unintended sexual health outcomes occurring in this population. Clinicians and researchers should include prevention messages that attend to the developmental age of patients and participants, their reproduction and pregnancy desires, and emotional processes involved in relationship experiences. Further, skills training and counselling strategies about these concepts should be integrated into nurse education programmes.

Strategies for targeting developmental age

Encourage emerging adult patients and participants to develop alternate personalised definitions of safety to work in conjunction with condom use to increase the definitions’ applicability to their lives. Providing emerging adults with a menu of options for healthy sexual behaviours may increase the likelihood that they will implement them. Meanings are context-specific and can change over time. Young women aged 18–25 years may be in the midst of experiencing a highly charged period of sexual self-discovery. Therefore, clinicians and researchers should allow for definitions to evolve based on perceptions, experiences and familial structure. In conjunction with the patient, nurses should develop a menu of activities that the patient can rely on to preserve her desire for safety. For example, researchers should acknowledge patients’ search for intimacy and romantic attachment as a healthy, normal process that may include sexual experiences with several partners. However, researchers should discuss alternatives to sexual intercourse that may provide patients with erotic stimulation, such as mutual masturbation, thereby decreasing potential exposure to biological infection while enhancing an opportunity to gain affection.

Strategies for addressing reproduction and pregnancy desires

Recognise that young women patients and participants may have competing priorities regarding reproduction and infection prevention. Emerging adult women have the highest rates of unintended pregnancy yet most sexual health interventions target school-aged adolescents. Fertility desires and childbearing have important roles in the intimate relationships of emerging adult women. Clinicians and researchers can provide integrated care that accounts for the potential for pregnancy intention. Questions that assess for current caregiving responsibilities and planned pregnancy may enhance applicability of infection prevention strategies.

Strategies for addressing sexual security and relationship experiences

Assess the patients’ and/or participants’ sexual security experiences and the effects of emotional processes on sexual decision-making over time. Methods for building self-esteem are widely used strategies but should be broadened to include assessment of interpersonal relationship experiences. Tools for encouraging healthy sexual behaviours could comprise survey or interview questions designed to elicit individualised responses to feelings about sexual decisions. Researchers and clinicians should elicit information regarding positive or desired outcomes from sexual activity such as economic stability, a caring relationship and/or pleasurable sex. Further assessment could include reflecting on a wide range of emotional dispositions previously experienced by the patient or participant during sexual relationships. For example, clinicians could incorporate questions such as How do you feel when you are in love? How did you handle those feelings in previous relationships? What do you do when you are lonely or sad? Are you more likely to engage in high-risk sex when you are feeling this way? Guidance from clinicians and educators regarding these lessons learned may inform the future sexual health behaviours of young women. Additionally, these questions provide patients and participants time to reflect, offering an opportunity for self-directed learning. This type of communication should endure over the course of the patient–provider relationship, allowing for a set of skills to be developed over time.

Opportunities for nursing education

Integrate broadened sexual health language that includes sexual security and reproduction into nurse training programmes. Nurses develop interviewing skills and counselling strategies as part of their entry-level training programmes, and eliciting sexual health information is a sensitive topic. Through enhanced training about these subjects, future nurses should be prepared to engage with patients and research participants using open-ended questions – one of the tenets of motivational interviewing. These strategies may foster healthy nurse–patient relationships, giving nurses unique opportunities to acknowledge nuances of sexual relations that shape young women across their lifespans.

What does this paper contribute to the wider global clinical community?

We emphasise the merits of individualised clinical approaches to sexual health care for young women.

We provide strategies to broaden research and clinical assessment of sexual health needs.

We promote attention to comprehensive sexual health language that addresses influences of affective processes on sexual decision-making.

Relevance to clinical practice.

This study provides nurses and public health educators with recommendations for broadening the content of sexual health promotion intervention programming.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: Ruth L. Kirschstein NRSA Individual Predoctoral Fellowship (F31NR0113121, PI: Alexander) funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research and administered by the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing. This research was also supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein NRSA Institutional Postdoctoral Fellowship (T32-HDO64428, PI: J. Campbell) funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Grants from Sigma Theta Tau International, the Alice Paul Center for the Study of Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies at the University of Pennsylvania and the Society for the Scientific Study of Sexuality also contributed to this research.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors have confirmed that all authors meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship credit (www.icmje.org/ethical_1author.html) as follows: (1) substantial contributions to conception and design of, or acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data, (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content and (3) final approval of the version to be published.

Contributor Information

Kamila A Alexander, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, Baltimore, MD.

Loretta S Jemmott1, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, Philadelphia, PA.

Anne M Teitelman, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, Philadelphia, PA.

Patricia D’Antonio, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

References

- Ariely D, Loewenstein G. The heat of the moment: the effect of sexual arousal on sexual decision making. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. 2006;19:87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander K. Sexual safety and sexual security: Broadening the sexual health discourse. 2012 Accessed at http://repository.upenn.edu/dissertations/AAI3550742/, Dissertations Available at ProQuest. 1 January 2012.

- Baker SA, Beadnell B, Stoner S, Morrison DM, Gordon J, Collier C, Knox K, Wickizer L, Stielstra S. Skills training versus health education to prevent STDs/HIV in heterosexual women: a randomized controlled trial utilizing biological outcomes. Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome Education and Prevention. 2003;15:1–14. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.1.1.23845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner P. From novice to expert excellence and power in clinical nursing practice. The American Journal of Nursing. 1984;84:1479. [Google Scholar]

- Bourne AH, Robson MA. Perceiving risk and (re)constructing safety: the lived experience of having ‘safe’ sex. Health, Risk & Society. 2009;11:283–295. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce P, Lee MHS, Jenkins C, Mohamed S, Overs C, Paiva V, Reid E, Tan M, Aggleton P. Putting sexuality (back) into HIV/AIDS: issues. Theory and practice. Global Public Health. 2007;2:1–34. doi: 10.1080/17441690600899362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan AD, Aiken LS, West SG. Increasing condom use: evaluation of a theory-based intervention to prevent sexually transmitted diseases in young women. Health Psychology. 1996;15:371. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.5.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byno LH, Mullis RL, Mullis AK. Sexual behavior, sexual knowledge, and sexual attitudes of emerging adult women: implications for working with families. Journal of Family Social Work. 2009;12:309–322. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control HIV Among Women. 2013 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/women/pdf/women.pdf (accessed 13 June 2014)

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Subpopulation Estimates from the HIV Incidence Surveillance System United States, 2006. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5736a1.htm, accessed 15 March 2012. [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . A Public Health Approach for Advancing Sexual Health in the United States: Rationale and Options for Implementation, Meeting Report of an External Consultation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2010a. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2009. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Atlanta, GA: 2010b. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Compendium of Evidence-Based HIV Behavioral Interventions: Risk Reduction Chapter. 2012 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/research/prs/rr_chapter.htm (accessed 2 November 2012)

- Choi KH, Hoff C, Gregorich SE, Grinstead O, Gomez C, Hussey W. The efficacy of female condom skills training in HIV risk reduction among women: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:1841–1848. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates TJ, Richter L, Caceres C. Behavioural strategies to reduce HIV transmission: how to make them work better. Lancet. 2008;372:669. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60886-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Mays VM. Applying social psychological models to predicting HIV-related sexual risk behaviors among African Americans. The Journal of Black Psychology. 1993;19:142–151. doi: 10.1177/00957984930192005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett AM, Dickson-Gómez J, Hilario H, Weeks MR. A little thing called love: condom use in high-risk primary heterosexual relationships. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2009;41:218–224. doi: 10.1363/4121809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corneille MA, Tademy RH, Reid MC, Belgrave FZ, Nasim A. Sexual safety and risk taking among African American men who have sex with women: a qualitative study. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2008;9:207–220. [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM. Marital conflict and child adjustment: an emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:387–411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diallo DD, Moore TW, Ngalame PM, White LD, Herbst JH, Painter TM. Efficacy of a single-session HIV prevention intervention for black women: a group randomized controlled trial. Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome and Behavior. 2010;14:518–529. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9672-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Harrington KF, Lang DL, Davies SL, Hook EW, III, Oh MK, Crosby RA, Hertzberg VS, Gordon AB, Hardin JW, Parker S, Robillard A. Efficacy of an HIV prevention intervention for African American adolescent girls: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292:171–179. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edin K, Kefalas M. Promises I Can Keep: Why Poor Women Put Motherhood before Marriage, with a New Preface. University of California Press; Berkeley & Los Angeles, California: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt AA, Exner TM, Hoffman S, Silberman I, Leu CS, Miller S, Levin B. A gender-specific HIV/STD risk reduction intervention for women in a health care setting: short-and long-term results of a randomized clinical trial. Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome Care. 2002;14:147–161. doi: 10.1080/09540120220104677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finer LB. Trends in premarital sex in the United States, –. Public Health Reports. 2007;122:73–78. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finer LB, Henshaw SK. Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2006;38:90–96. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.090.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finocchario-Kessler S, Sweat MD, Dariotis JK, Trent ME, Kerrigan DL, Keller JM, Anderson JR. Understanding high fertility desires and intentions among a sample of urban women living with HIV in the United States. Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome and Behavior. 2010;14:1106–1114. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9637-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galinsky AM, Sonenstein FL. The association between developmental assets and sexual enjoyment among emerging adults. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;48:610–615. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arezou Ghane, Kate Sweeny. Embodied health: a guiding perspective for research in health psychology. Health Psychology Review. 2013;7(Suppl.1):S159–S184. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie BL, Choi RY, Bosire R, Kiarie JN, Mackelprang RD, Gatuguta A, John-Stewart GC, Farquhar C. Predicting pregnancy in HIV-1-discordant couples. Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome and Behavior. 2010;14:1066–1071. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9716-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison A. Hidden love: sexual ideologies and relationship ideals among rural South African adolescents in the context of HIV/AIDS. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 2008;10:175–189. doi: 10.1080/13691050701775068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JA. Pleasure, power, and inequality: incorporating sexuality into research on contraceptive use. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:1803. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.115790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JA, Hirsch JS. The pleasure deficit: revisiting the sexuality connection in reproductive health. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2007;33:133–139. doi: 10.1363/3313307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JA, Hoffman S, Graham CA, Sanders SA. Relationships between condoms, hormonal methods, and sexual pleasure and satisfaction: an exploratory analysis from the women’s well-being and sexuality study. Sexual Health. 2008;5:321–330. doi: 10.1071/sh08021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JA, Tanner AE, Janssen E. Arousal loss related to safer sex and risk of pregnancy: implications for women’s and men’s sexual health. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2009;41:150–157. doi: 10.1363/4115009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Jackson AP, Lavin J, Johnson RJ, Schröder KEE. Effects and generalizability of communally oriented HIV-AIDS prevention versus general health promotion groups for single, inner-city women in urban clinics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:950. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta-Franco R, Malacara JM. Factors associated with the sexual experiences of underprivileged Mexican adolescents. Adolescence. 1999;34:389–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ickovics JR, Kershaw TS, Westdahl C, Magriples U, Massey Z, Reynolds H, Rising SS. Group prenatal care and perinatal outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;110:330. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000275284.24298.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB, III, O’Leary A. Effects on sexual risk behavior and STD rate of brief HIV/STD prevention interventions for African American women in primary care settings. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:1034–1040. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.020271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemmott JB, III, Jemmott LS, Fong GT. Efficacy of a theory-based abstinence-only intervention over 24 months: a randomized controlled trial with young adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2010;164:152. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns MM, Zimmerman M, Bauermeister JA. Sexual attraction, sexual identity, and psychosocial wellbeing in a national sample of young women during emerging adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42:82–95. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9795-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamb ML, Fishbein M, Douglas JM, Jr, Rhodes F, Rogers J, Bolan G, Zenilman J, Hoxworth T, Malotte CK, Iatesta M. Efficacy of risk-reduction counseling to prevent human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted diseases. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280:1161–1167. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.13.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kershaw TS, Magriples U, Westdahl C, Rising SS, Ickovics J. Pregnancy as a window of opportunity for HIV prevention: effects of an HIV intervention delivered within prenatal care. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:2079–2086. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.154476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kippax S, Stephenson N, Parker RG, Aggleton P. Between individual agency and structure in HIV prevention: understanding the middle ground of social practice. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:1367–1375. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby D, Laris BA. Effective curriculum-based sex and STD/HIV education programs for adolescents. Child Development Perspectives. 2009;3:21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Knox D, Sturdivant L, Zusman ME. College student attitudes toward sexual intimacy. College Student Journal. 2001;35:241–243. [Google Scholar]

- Lauby JL, Smith PJ, Stark M, Person B, Adams J. A community-level HIV prevention intervention for innercity women: results of the women and infants demonstration projects. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:216. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.2.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz ES, Gillen MM. “Sex is just a normal part of life”: sexuality in emerging adulthood. In: Arnett JJ, Tanner JL, editors. Emerging Adults in America: Coming of Age in the 21st Century. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2006. pp. 235–255. [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein G, Lerner JS. The role of affect in decision making. In: Davidson R, Sherer KR, Goldsmith HH, editors. Handbook of Affective Science. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2003. pp. 619–642. [Google Scholar]

- Markham CM, Tortolero SR, Fleschler Peskin M, Shegog R, Thiel M, Baumler ER, Addy RC, Escobar-Chaves SL, Reininger B, Robin L. Sexual risk avoidance and sexual risk reduction interventions for middle school youth: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50:279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrazzo JM, Coffey P, Bingham A. Sexual practices, risk perception and knowledge of sexually transmitted disease risk among lesbian and bisexual women. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2005;37:6–12. doi: 10.1363/psrh.37.006.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier A, Allen G. Intimate relationship development during the transition to adulthood: differences by social class. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2008;119:25–39. doi: 10.1002/cd.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melendez RM, Hoffman S, Exner T, Leu C-S, Ehrhardt AA. Intimate partner violence and safer sex negotiation: effects of a gender-specific intervention. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2003;32:499–511. doi: 10.1023/a:1026081309709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf CA, Malotte CK, Douglas JM, Jr, Paul SM, Dillon BA, Cross H, Brookes LC, DeAugustine N, Lindsey CA, Byers RH. Efficacy of a booster counseling session 6 months after HIV testing and counseling: a randomized, controlled trial (RESPECT-2) Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2005;32:123–129. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000151420.92624.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S, Exner TM, Williams SP, Ehrhardt AA. A gender-specific intervention for at-risk women in the USA. Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome Care. 2000;12:603–612. doi: 10.1080/095401200750003789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naisteter MA, Sitron JA. Minimizing harm and maximizing pleasure: considering the harm reduction paradigm for sexuality education. American Journal of Sexuality Education. 2010;5:101–115. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson AL, Shields WC. Healthy sexuality. Contraception. 2005;71:399–401. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIMH Multisite HIV Prevention Trial Group NIMH multisite HIV prevention trial: reducing HIV sexual risk behavior. Science. 1998;280:1889–1894. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peragallo N, DeForge B, O’Campo P, Lee SM, Kim YJ, Cianelli R, Ferrer L. A randomized clinical trial of an HIV-risk-reduction intervention among low-income Latina women. Nursing Research. 2005;54:108–118. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200503000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Swendeman D, Flannery D, Rice E, Adamson DM, Ingram B. Common factors in effective HIV prevention programs. Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome and Behavior. 2009;13:399–408. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9464-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sales JMD, Salazar LF, Wingood GM, Di-Clemente RJ, Rose E, Crosby RA. The mediating role of partner communication skills on HIV/STD-associated risk behaviors in young African American females with a history of sexual violence. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2008;162:432. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.5.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schensul JJ, Trickett E. Introduction to multi-level community based culturally situated interventions. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;43:232–240. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9238-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholes D, McBride CM, Grothaus L, Civic D, Ichikawa LE, Fish LJ, Yarnall KSH. A tailored minimal self-help intervention to promote condom use in young women: results from a randomized trial. Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome. 2003;17:1547–1556. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200307040-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shain RN, Piper JM, Newton ER, Perdue ST, Ramos R, Champion JD, Guerra FA. A randomized, controlled trial of a behavioral intervention to prevent sexually transmitted disease among minority women. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;340:93–100. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shain RN, Piper JM, Holden AEC, Champion JD, Perdue ST, Korte JE, Guerra FA. Prevention of gonorrhea and Chlamydia through behavioral intervention: results of a two-year controlled randomized trial in minority women. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2004;31:401–408. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000135301.97350.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuell TJ. Phases of meaningful learning. Review of Educational Research. 1990;60:531–547. [Google Scholar]

- Sterk CE, Theall KP, Elifson KW. The impact of emotional distress on HIV risk reduction among women. Substance Use & Misuse. 2006;41:157–173. doi: 10.1080/10826080500391639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner JL, Arnett JJ, Leis JA. Emerging adulthood: Learning and development during the first stage of adulthood. In: Smith MC, editor. Handbook of Research on Adult Learning and Development. Routledge; New York: 2009. pp. 34–67. [Google Scholar]

- Thurman AR, Holden AEC, Shain RN, Perdue S, Piper JM. Preventing recurrent sexually transmitted diseases in minority adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;111:1417–1425. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318177143a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson SY. Developmental and ethnic issues experienced by emerging adult African American women related to developing a mature love relationship. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2011;33:39–51. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2011.620681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warr DJ. The importance of love and understanding: speculation on romance in safe sex health promotion. Women’s Studies International Forum. 2001;24:241–252. [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Mikhail I, Lang DL, McCree DH, Davies SL, Hardin JW, Hook EW, Saag M. A randomized controlled trial to reduce HIV transmission risk behaviors and sexually transmitted diseases among women living with HIV: the WiLLOW program. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;37:S58–S67. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000140603.57478.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Defining Sexual Health: Report of a Technical Consultation on Sexual Health, 28–31 January 2002. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt GE, Williams JK, Myers HF. African–American sexuality and HIV/ AIDS: recommendations for future research. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2008;100:44–48. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31173-1. 50–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]