Significance

Numerous bacterial toxins can cross cell membranes, penetrating the cytosol of their target cells, but to do so exploits cellular endocytosis or intracellular sorting machineries. Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin (ACT) delivers its catalytic domain directly across the cell membrane by an unknown mechanism, and generates cAMP, which subverts the cell signaling. Here, we decipher the fundamentals of the molecular mechanism of ACT transport. We find that AC translocation and, consequently cytotoxicity, are determined by an intrinsic ACT–phospholipase A (PLA) activity, supporting a model in which in situ generation of nonlamellar lysophospholipids by ACT–PLA activity remodels the cell membrane, forming proteolipidic toroidal “holes” through which AC domain transfer may directly take place. PLA-based specific protein transport in cells is unprecedented.

Keywords: bacterial toxins, RTX toxin family, protein translocation, biological membranes, membrane remodeling

Abstract

Adenylate cyclase toxin (ACT or CyaA) plays a crucial role in respiratory tract colonization and virulence of the whooping cough causative bacterium Bordetella pertussis. Secreted as soluble protein, it targets myeloid cells expressing the CD11b/CD18 integrin and on delivery of its N-terminal adenylate cyclase catalytic domain (AC domain) into the cytosol, generates uncontrolled toxic levels of cAMP that ablates bactericidal capacities of phagocytes. Our study deciphers the fundamentals of the heretofore poorly understood molecular mechanism by which the ACT enzyme domain directly crosses the host cell membrane. By combining molecular biology, biochemistry, and biophysics techniques, we discover that ACT has intrinsic phospholipase A (PLA) activity, and that such activity determines AC translocation. Moreover, we show that elimination of the ACT–PLA activity abrogates ACT toxicity in macrophages, particularly at toxin concentrations close to biological reality of bacterial infection. Our data support a molecular mechanism in which in situ generation of nonlamellar lysophospholipids by ACT–PLA activity into the cell membrane would form, likely in combination with membrane-interacting ACT segments, a proteolipidic toroidal pore through which AC domain transfer could directly take place. Regulation of ACT–PLA activity thus emerges as novel target for therapeutic control of the disease.

The Gram-negative bacterium Bordetella pertussis causes whooping cough (pertussis), a highly contagious respiratory disease that is an important cause of childhood morbidity and mortality (1, 2). Despite widespread pertussis immunization in childhood, there are an estimated 50 million cases and 300,000 deaths caused by pertussis globally each year. Infants who are too young to be vaccinated, children who are partially vaccinated, and fully vaccinated persons with waning immunity are especially vulnerable to disease (1).

B. pertussis secretes several virulence factors, and among them adenylate cyclase toxin (ACT or CyaA) is crucial in the early steps of colonization of the respiratory tract by the bacterium (3). Upon binding to the CD11b/CD18 integrin expressed on myeloid phagocytes (4), ACT invades these immune cells by delivering into their cytosol a calmodulin-activated adenylate cyclase (AC) domain that catalyzes the uncontrolled conversion of cytosolic ATP into cAMP (5), which causes inhibition of the oxidative burst and complement-mediated opsonophagocytic killing of bacteria (6, 7). ACT also has hemolytic properties conferred by its C-terminal domain, which may form pores that permeabilize the cell membrane for monovalent cations, thus contributing to overall cytoxicity of ACT toward phagocytes (8–10). Bordetella ACT toxin, together with the anthrax edema factor, are the two prototypes of bacterial protein toxin that attack the immune response by overboosting the major signaling pathway in the immune response (cAMP, together with the MAPK pathway) (11).

ACT is a single polypeptide of 1,706 amino acids, constituted by an AC enzyme domain (≈residues 1–400) and a C-terminal hemolysin domain (residues ≈ 400–1,706) characteristic of the RTX family of toxins to which ACT belongs (12, 13). Both activities can function independently as AC and hemolysin, respectively (14, 15). The hemolysin domain contains, in turn, a hydrophobic region with amphipathic α-helices (∼500–750 residues) likely involved in pore-formation, two conserved Lys residues (Lys-863 and Lys-913) that are posttranslationally fatty acylated by a dedicated acyltransferase (CyaC), and a C-terminal secretion signal recognized by a specific secretion machinery (CyaB, CyaD, and CyaE) (13, 16). ACT activity on cells requires binding of Ca2+ ions into the numerous (∼40) sites located in the C-terminal calcium-binding RTX repeats that are formed by Gly- and Asp-rich nonapeptides harboring a conserved X-(L/I/V)-X-G-G-X-G-X-D motif (17, 18). This repeat domain has been reported to be involved in the toxin binding to its specific cellular receptor, the CD11b/CD18 integrin (4, 19).

To generate cAMP into the host cytosol, ACT has to translocate its catalytic domain from the hydrophilic extracellular medium into the hydrophobic environment of the membrane, and then to the cell cytoplasm. How this is accomplished remains poorly understood. It is believed that after binding to the CD11b/CD18 receptor, ACT inserts its amphipathic helices into the plasma membrane and then delivers its catalytic domain directly across the lipid bilayer into the cytosol (20, 21) without receptor-mediated endocytosis (22). Temperatures above 15 °C (20), calcium at millimolar range, negative membrane potential, and unfolding of the AC domain (23) have been noted to be necessary for AC delivery.

Several studies have highlighted the importance of various amino acids and the contribution of distinct domains of the ACT polypeptide in the translocation process (21, 24). However, a full description at the molecular level of the individual steps that the polypeptide follows to cross the membrane is still missing. Delivery of the AC domain does not appear to proceed through the cation-selective pore formed by the hemolysin domain (25), but it requires structural integrity of the hydrophobic segments (24), and it seems that the RTX hemolysin domain (residues 374–1,706) harbors all structural information required for AC translocation (26). The region encompassing the helix 454–485 of ACT has been recently noted as possibly playing an important role in promoting translocation of the AC domain across the plasma membrane of target cells (27, 28). A two-step model was proposed for AC translocation: in a first step, and upon ACT binding to its CD11b/CD18 integrin receptor, a translocation-competent ACT conformer would conduct extracellular Ca2+ ions across the plasma membrane, which would activate a calpain-mediated cleavage of talin, releasing the ACT–integrin complex from the cytoskeleton. In a second step, this ACT–integrin complex would move into lipid rafts, and there the cholesterol-rich lipid environment would promote the translocation of the AC domain across the cell membrane (29). A caveat of this model is the difficulty to explain how ACT translocates its AC domain into cells that do not express the CD11b/CD18 integrin receptor (22, 30, 31).

In recent years our laboratory has extensively explored ACT interaction with lipid membranes, and we have discovered that toxin insertion into lipid bilayers induces transbilayer lipid motion (lipid “scrambling” or “flip-flop”) (32). Transbilayer lipid movement may occur as a result of the insertion of foreign molecules (detergents, lipids, or even proteins) in one of the membrane leaflets, or it may result from the enzymatic generation of lipids (e.g., lysophospholipids, diacylglycerol, or ceramide) at one side of the membrane (33), and it has been involved in enhancing the transmembrane permeability of the lipid membranes (33). Here we sought to investigate whether ACT might possess intrinsic enzyme activity on lipids, which could participate in AC domain translocation. We discovered that ACT is a calcium-dependent phospholipase A (PLA) that, by remodeling the cell membrane, mediates translocation of its catalytic domain in target macrophages.

Results

In Vitro ACT–PLA Activity.

To explore potential enzyme activity of ACT on lipids, liposomes (LUV) composed of the common membrane lipid phosphatidylcholine (PC) were incubated with ACT (at four different lipid:protein molar ratios) for 30 min at 37 °C, after which we performed lipid extraction of the samples. The extracted lipid fractions were spotted on silica plates together with appropriate lipid standards, and after being chromatographed in one dimension (thin-layer chromatography, TLC) we performed quantification of the spots by densitometry. The spots whose intensity was proportional to the lipid:toxin ratio used in each experiment were detected and found to migrate with an Rf value similar to the lipid standard corresponding to free fatty acids, thus suggesting that ACT possess intrinsic PLA activity. Data from the densitometric analysis are depicted in Fig. S1. A control value, which was arbitrarily set as the unity, corresponds to the data obtained from liposomes treated without toxin. Because no spots corresponding to diacylglycerol, phosphatidic acid, or ceramide were detected on the TLC gels analyzed, potential phospholipase C (PLC), phospholipase D (PLD), and sphingomyelinase activities were in principle discarded.

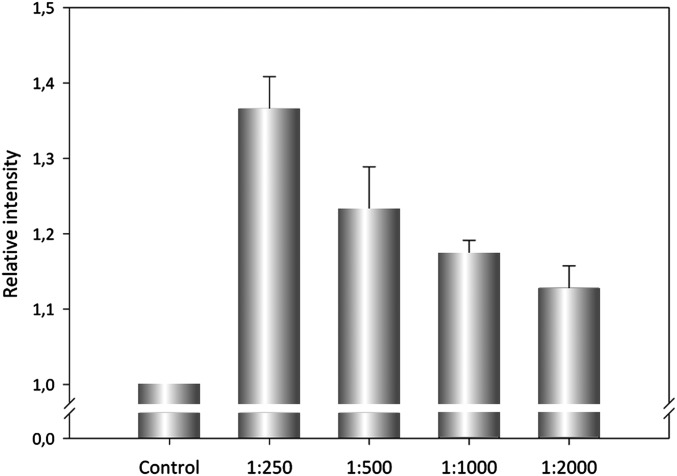

Fig. S1.

Densitometric quantification of the lipid spots resolved by TLC from the reaction products generated in an in vitro incubation of pure DOPC liposomes with ACT. Liposomes composed of pure DOPC were incubated with ACT at different lipid:protein molar ratio for 30 min at 37 °C, after which lipid extraction of lipids was performed. Samples were run on silica gel 60 glass sheets (Merck Millipore). TLC plates were developed in a solution of 70 mL n-heptane, 30 mL diisopropyl ether, and 2 mL acetic acid.

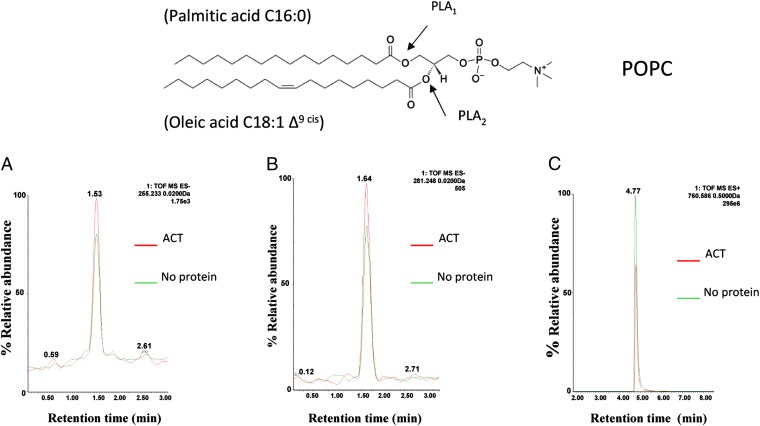

The ACT–PLA activity was further demonstrated by means of an ultrahigh performance liquid-chromatography mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS) analysis of the products of an in vitro ACT phospholipase reaction (Fig. 1). POPC vesicles (1-palmitoyl-2-oleil-phosphatidylcholine) with distinct fatty acids, palmitic acid (C16:0) and oleic acid (C18:1) on sn-1 and sn-2 positions, respectively, were used as substrate. Superimposition of the chromatograms obtained for the POPC substrate incubated with ACT showed a considerable increase in the relative abundance of a mass of 255.233 m/z (Fig. 1A), which corresponds to the reference standard for free palmitic acid (C16:0), and of a mass of 281.248 m/z (Fig. 1B), corresponding to free oleic acid (C18:1). Coincident with the appearance of free fatty acids, there was a quantitative reduction (35% reduction) in the relative abundance of the substrate with a mass of 760.586 m/z (Fig. 1C) corresponding to intact POPC (C34:1). These data corroborate that ACT cleaves the sn-1 and sn-2 ester bonds in POPC, and thus possesses PLA activity.

Fig. 1.

Identification of the reaction products of ACT-PLA activity by UHPLC-MSE. Identification of the reaction products of an in vitro PLA reaction on POPC lipid substrate were performed using UHPLC and simultaneous acquisition of exact mass at high and low collision energy, MSE. In the figure, representative extracted ion UHPLC-ESI-MSE chromatograms are shown: electrospray ionization (ESI)−, m/z 255.233 of ion [Palmitic acid-H]− (A), m/z 281.248 of ion [Oleic acid-H]− (B), and ESI+, m/z 760.586 of ion [PC(16:0/18:1)+H]+ (C) obtained from samples containing POPC lipid substrate (green) or substrate exposed to ACT (red). On top of the figure is a schematic representation of PLA1 and PLA2 cleavage sites on phospholipids is shown.

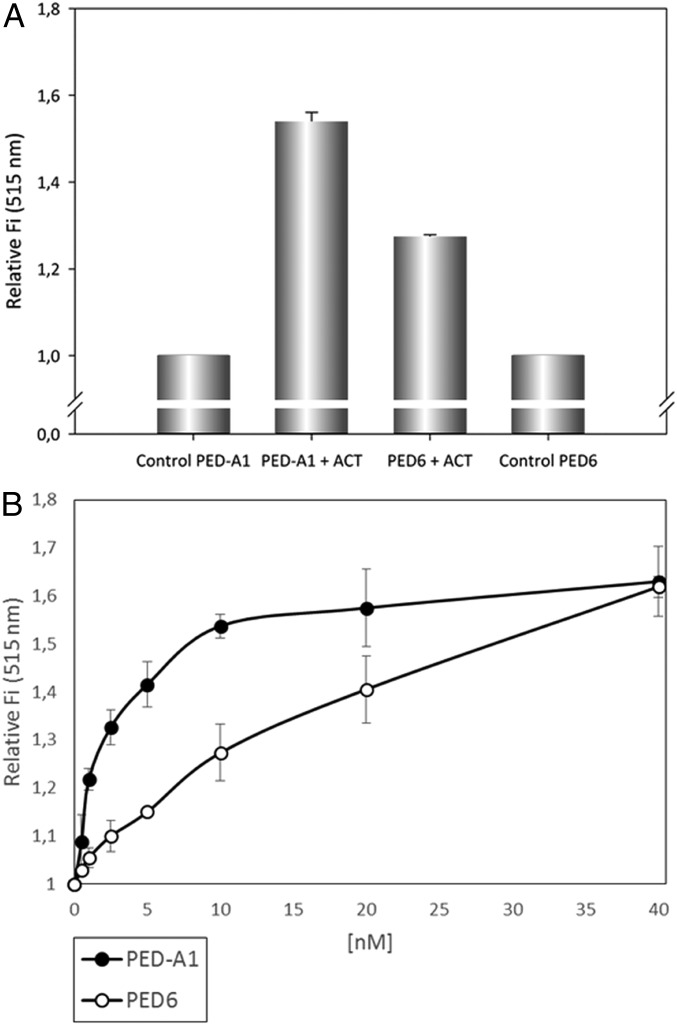

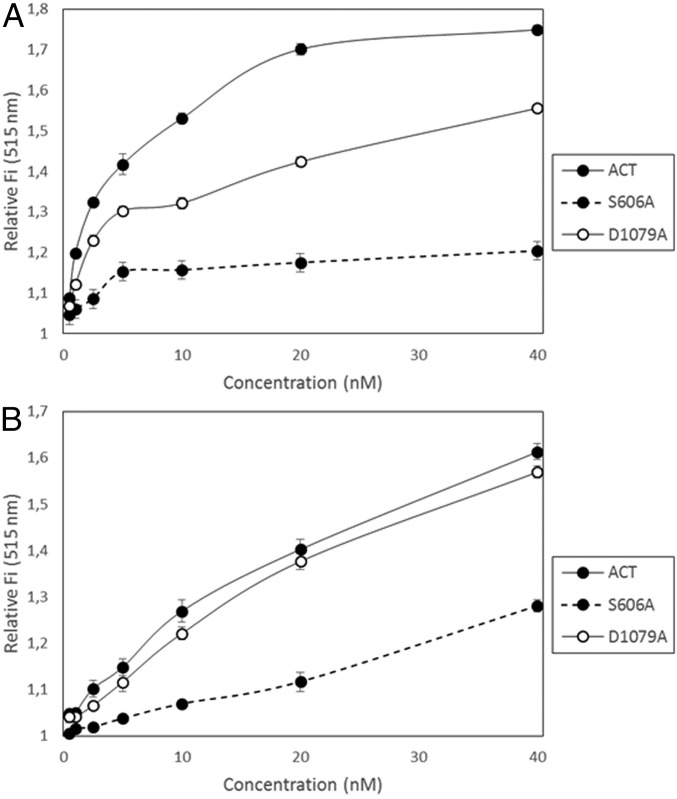

To identify more clearly whether the ACT–PLA activity cleaves specifically the sn-1 or the sn-2 ester bond of the lipid substrate, we used highly sensitive fluorogenic phospholipid substrates called PED-A1 [N-((6-(2,4-DNP)Amino)Hexanoyl)-1-(BODIPY FL C5)-2-Hexyl-Sn-Glycero-3-Phosphoethanolamine] (which measures PLA1 activity) and PED6 [N-((6-(2,4-Dinitrophenyl)amino)hexanoyl)-2-(4,4-Difluoro-5,7-Dimethyl-4-Bora-3a,4a-Diaza-s-Indacene-3-Pentanoyl)-1-Hexadecanoyl-sn-Glycero-3-Phosphoethanolamine] (which measures PLA2 activity) (34). Both substrates are modified glycerophosphoethanolamines with BODIPY FL dye-labeled sn-1 or sn-2 acyl chains, respectively, and a dinitrophenyl group conjugated to the polar head group of the lipid to provide intramolecular quenching. Thus, sn-1 or sn-2 acyl chain cleavage by PLA1 or PLA2 activity eliminates the dye quenching, which results in increased fluorescence of the fluorophore. As shown in Fig. 2, incubation of ACT (10 nM) with DOPC liposomes containing PED-A1 substrate (20% molar ratio) induced an increase of the fluorescence measured at 515 nm, indicating the release of free fatty acid from the sn-1 ester bond of the fluorescent substrate (Fig. 2A). Similarly, addition of ACT (10 nM) to DOPC liposomes containing PED6 (20% molar ratio) induced as well fluorescence increase at 515 nm (Fig. 2A), indicating that the sn-2 ester bond was also being hydrolyzed by ACT and free fatty acid released at the same time. Comparison of EC50 values obtained from the fluorescence data for both fluorescent substrates at identical conditions (EC50 for PED-A1 = 2.42 nM; EC50 for PED6 = 12.85 nM) indicated, however, that ACT cleaves with notably more efficiency the sn-1 ester bond of the fluorescent substrate than the sn-2 ester bond. For both fluorogenic substrates the fluorescence increase was proportional to the toxin concentration added (Fig. 2B), and interestingly, the data indicated that the toxin PLA activity achieved saturation long before all of the substrate present was consumed (maximal relative fluorescence values for the hydrolysis of PED-A1 and PED6 substrates by the respective positive controls, PLA1 and PLA2, at a concentration of 0.25 µg/mL upon incubation for 30 min at 37 °C, were 3.066 ± 0.046 and 2.896 ± 0.078, respectively). In conclusion, this set of experiments demonstrates that ACT displays PLA activity, with preference for the sn-1 ester bond, and hence, most likely that ACT acts as a phospholipase A1 (PLA1) on natural membranes. Importantly, it also indicates that a “product inhibition” mechanism might operate in ACT–PLA activity. Several proteins with PLA activities may also display lysoPLA activity (35); in contrast, ACT did not detectably hydrolyze either LysoPC (C18:1) or DLPC:LysoPC (C18:1) lipid substrates, suggesting that it is not a lysophospholipase A (Fig. S2).

Fig. 2.

ACT–PLA reaction determined by cleavage of PLA1- and PLA2-specific fluorogenic substrates. Two different specific fluorogenic phospholipid substrates, PED-A1 and PED6, were used for measurement of PLA1 and PLA2 activities, respectively. These substrates incorporate a BODIPY FL-dye–labeled sn-1 or a BODIPY FL-dye–labeled sn-2 acyl chain, and a dinitrophenyl quencher group. Cleavage of the corresponding labeled-acyl chain by PLA1 or PLA2 activities results in the formation of nonfluorescent lysophospholipid and fluorescent fatty acid tagged to the fluorophore-BODIPY FL. The release of the corresponding fatty acid is determined as an increase of the fluorescence intensity at 515 nm (a.u.). The respective substrate hydrolysis was determined 30 min after incubation of the substrate with the toxin (10 nM) at 37 °C. PLA1 and PLA2 activities are expressed as an increase of the fluorescence intensity at 515 nm (a.u.) relative to the corresponding control (lipid substrate in buffer, without toxin). The phospholipid substrates in the assay were liposomes (LUV) prepared with mixtures of DOPC:PED-A1 (4:1 mol:mol) or DOPC:PED6 (4:1 mol:mol) as described in SI Materials and Methods (A). PLA1 and PLA2 activities expressed as increase of the fluorescence intensity at 515 nm (a.u.) as a function of ACT toxin concentration (0.5–40 nM) determined 30 min after incubation with the toxin (B). Data are expressed as average values ± SD from at least three independent experiments (n = 3).

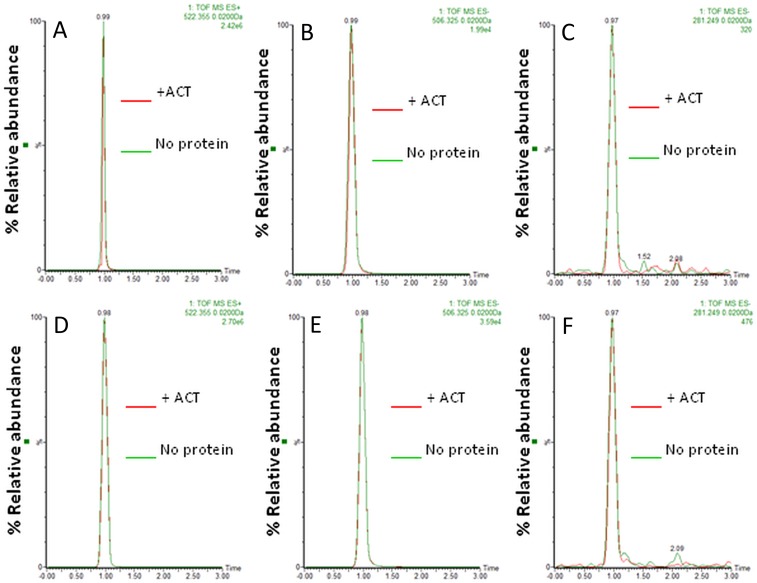

Fig. S2.

Analysis by UHPLC/MSE of the reaction products of ACT activity on LysoPC or LysoPC:DLPC lipid substrates. Identification of the reaction products of an in vitro ACT reaction on LysoPC (C18:1) or LysoPC (C18:1):DLPC (C12:0, C12:0) lipid substrates were performed using UHPLC and simultaneous acquisition of exact mass at high and low collision energy, MSE . In the figure, representative extracted ion UHPLC-ESI-MSE chromatograms are shown. (Upper) ESI+, m/z 522.3554 of ion [LysoPC(18:1)+H]+ (A); ESI−, m/z 506.3247 of ion [Lyso PC(18:1)-CH3-H]− (B); and m/z 281.2486 of ion [Oleic acid-H]− fragment ion from Lyso PC(18:1) (C) obtained from samples containing DLPC:LysoPC (18:1) lipid substrate (green) or substrate exposed to ACT (red). (Lower) ESI+, m/z 522.3554 of ion [LysoPC(18:1)+H]+ (D); ESI−, m/z 506.3247 of ion [Lyso PC(18:1)-CH3-H]− (E); and m/z 281.2486 of ion [Oleic acid-H]− fragment ion from Lyso PC(18:1) (F) obtained from samples containing LysoPC (18:1) lipid substrate (green) or substrate exposed to ACT (red).

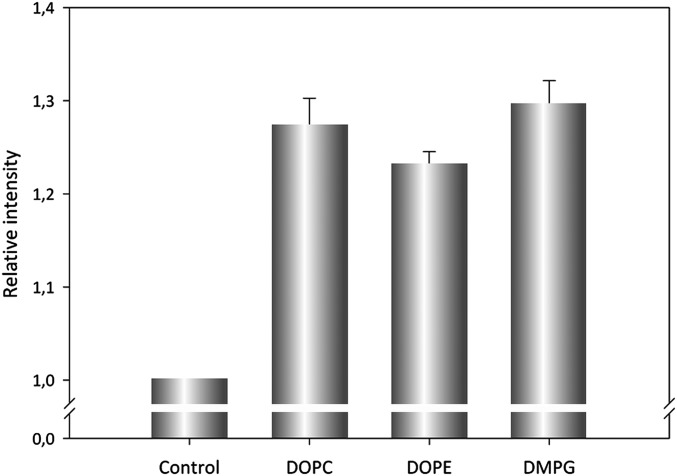

To have an idea of the substrate specificity of the ACT–PLA activity on several phospholipids, both neutral and anionic phospholipids were tested (Fig. S3). In this case, as a measure of the ACT–PLA activity, spots corresponding to free fatty acids were resolved by TLC and quantified by densitometry after incubation of ACT with liposomes made of different lipid substrates (DOPC, DOPE, DMPG) at a lipid:protein ratio of 1,000:1 for 30 min at 37 °C. Fig. S3 shows that ACT may hydrolyze, in vitro, both neutral and anionic phospholipids with similar efficiency, indicating that ACT–PLA may not have a clear specificity for any given phospholipid.

Fig. S3.

Analysis of the substrate specificity of the ACT–PLA activity on several phospholipids. Liposomes composed of pure DOPC, DOPE, or DMPG were incubated with ACT at a 1,000:1 lipid:protein molar ratio for 30 min at 37 °C, after which lipid extraction of lipids was performed. Samples were run on silica gel 60 glass sheets (Merck Millipore). TLC plates were developed in a solution of 70 mL n-heptane, 30 mL diisopropyl ether, and 2 mL acetic acid, and then an in situ quantification of the spots was performed by densitometry. Data were normalized with respect to the binding of the toxin to the different vesicles, as determined by immunostaining in a dot blot assay using anti-ACT antibodies. Average of two different experiments is shown.

ACT–PLA Harbors Conserved Ser/Asp Catalytic Sites, Sharing Similarity with Patatin-Like Phospholipases.

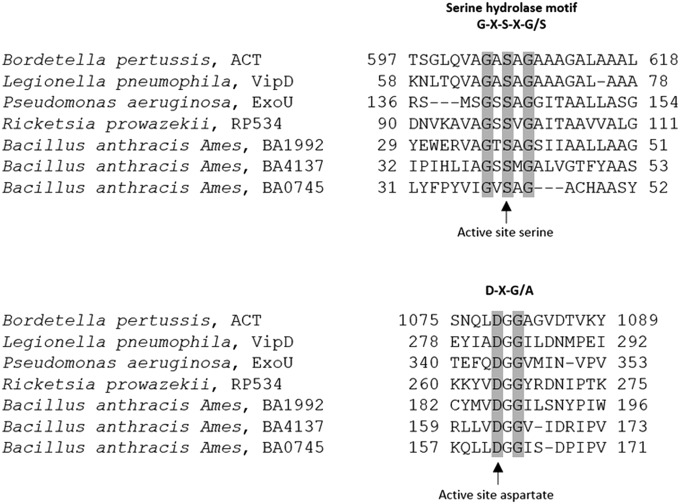

To characterize the ACT–PLA activity in greater detail, analysis of the ACT amino acid sequence was carried out with the multiple sequence alignment program ClustalOmega (https://www.ebi.ac.uk), finding similarities with several patatin-like phospholipases, such as the Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoU PLA2 (26.65% identity) or the Legionella pneumophila VipD PLA1 (21.60% identity) (Fig. S4). Patatin-like PLAs are most highly homologous to eukaryotic group IV cytosolic PLA2α and group VI calcium-independent PLA2, which are distinguished by a conserved Ser-Asp catalytic dyad within the active site, with catalytic Ser located in a conserved G-X-S-X-G hydrolase motif, and Asp in a D-X-G/A motif (boldface letters correspond to conserved catalytic residues involved in PLA activity) (36, 37). Remarkably, in its 1,706 amino acids long sequence, rich in Gly and Asp residues, ACT harbors a single G-X-S-X-G motif, with a GASAG sequence, which is localized in the predicted membrane-interacting α-helical region (residues 500–700) of ACT. On other side, the DXG/A motif that fits best in the alignment analysis against the sequences of several patatin-like phospholipases has a DGG sequence, and it is localized in the first one of the five Ca2+-binding β-rolls (block I, residues 1,014–1,087) that form the so-called C-terminal repeat domain. Additionally, along its C-terminal sequence ACT contains, in addition to the D1079GG motif, three more DXG motifs, but their fitting in the sequence alignment assay was worse.

Fig. S4.

Sequence alignment of ACT with patatin-like phospholipases. Alignment of the protein sequences of Bordetella pertussis ACT, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoU (amino acids 107–154 and 316352), and Legionella pneumophila VipD (amino acids 58–78 and 278–292), and other patatin‐like PLA2 domains using the EMBL-EBI Clustal Omega multiple sequence alignment program and the National Center for Biotechnology Information Conserved Domain Database.

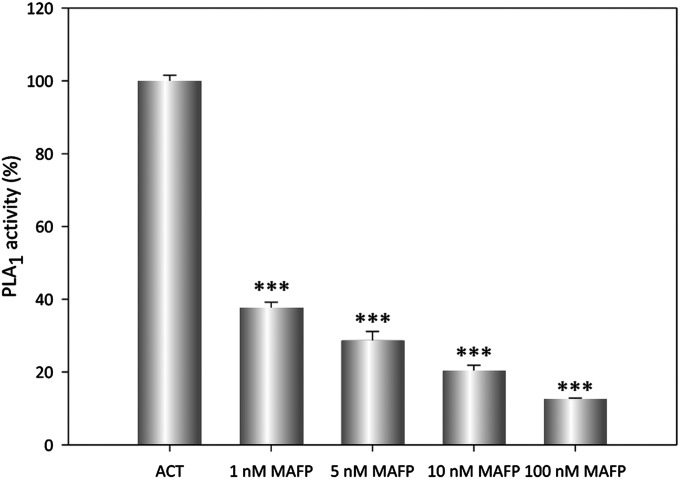

To ascertain whether ACT–PLA activity relies on the mentioned Ser and Asp residues, and thus to experimentally validate our prediction, we initially tested residue-specific agents, such as MAFP (methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphonate), for their ability to inhibit ACT–PLA activity. MAFP is the MAFP analog of arachidonic acid (AA), which is known to bind irreversibly to Ser residues and inhibit LysoPLA type I and PLA2 family members that exhibit LysoPLA activities (groups IV and VI) with an IC50 of 0.5–5 μM and other hydrolases, such as fatty acid amide hydrolase, with an IC50 of 2.5–20 nM (38, 39). MAFP is known to also inhibit enzymes with PLA1 activity (38). At a concentration of 10 nM, ACT was incubated with PED-A1–containing liposomes (lipid:protein molar ratio 1,000:1) in the presence of increasing amounts of MAFP (1–100 nM). Release of dye-labeled sn-1 fatty acid from DOPC–PED-A1 liposomes by ACT–PLA activity was drastically halted by MAFP in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3), which indicates that a catalytic Ser residue is involved in the ACT lipolytic activity.

Fig. 3.

Dose-dependent inhibition of the ACT–PLA activity by MAFP, a residue specific irreversible PLA inhibitor. Release of dye-labeled sn-1 fatty acid from DOPC:PED-A1 (4:1 mol:mol) liposomes by ACT–PLA1 activity was determined by fluorescence spectroscopy, in the presence of different concentrations of the PLA inhibitor MAFP, in the range 1–100 nM. PLA1 activity of ACT (10 nM) on DOPC:PED-A1 (4:1 mol:mol) liposomes after 30-min incubation, normalized with respect to the control (substrate in buffer, without toxin) was taken as 100% activity. Average values ± the SEM (n = 3) are shown. ***P < 0.001 with respect to intact ACT.

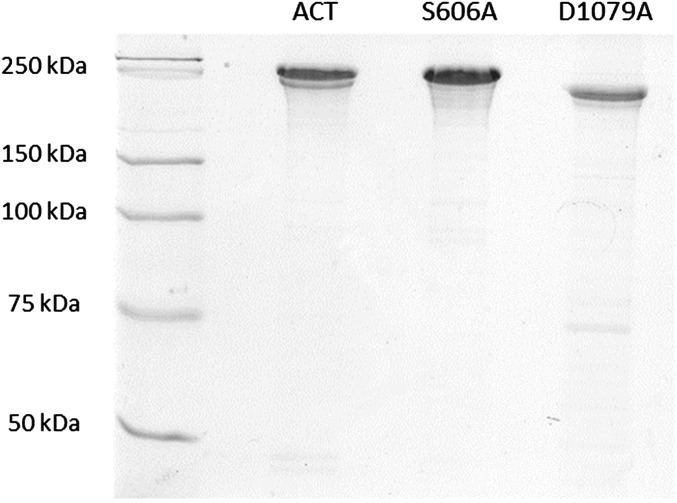

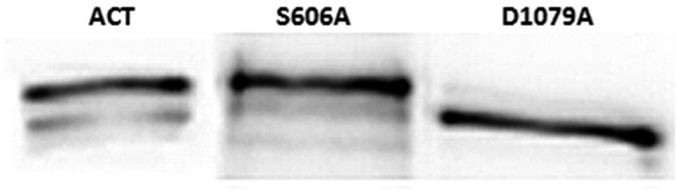

To further verify the involvement of the predicted catalytic residues in ACT–PLA activity, we constructed two ACT mutants, one in which Ser-606 was substituted by Ala (S606A), and a second mutant in which Asp-1079 was substituted by Ala (D1079A). A secondary structure of WT ACT and of the two mutant proteins at 1-μM concentration (buffer with 10 mM CaCl2) was checked by far-UV circular dichroism (CD), and it was verified that the structure of the three proteins was very similar (Figs. S5 and S6). PLA1 and PLA2 activities of the purified mutant proteins were checked using the substrates PED-A1 and PED6. As shown in Fig. 4, substitution of the Ser-606 by Ala had a dramatic effect on the toxin in vitro both PLA activities, so that the mutant protein S606A was almost inactive in cleaving the fluorogenic substrates, relative to the intact ACT toxin. Substitution of Ser-606 by Ala did not affect any of the other ACT activities (production of cAMP in solution, hemolytic activity) in the mutant protein ACT-S606A (Table S1). Replacement of Asp-1079 by Ala showed a less deleterious—although still substantial—decreasing effect on the mutant PLA1 activity, but its effect on the PLA2 activity was not significant (Fig. 4). Interestingly, this substitution also decreased the hemolytic potency of the ACT-D1079A protein relative to WT ACT, whereas it did not alter at all of the cAMP-producing AC activity of the mutant in solution (Table S1). Taken together, these results proved that Ser-606 and Asp-1079 are directly involved in the ACT–PLA1 catalytic reaction, corroborating our predictive data and suggesting that the catalytic mechanism of ACT–PLA might proceed through a serine-acyl intermediate, in the likeness of the patatin-like PLAs.

Fig. S5.

CD spectra of ACT and of ACT mutants S606A and D1079A. Far UV CD spectra (200–250 nm) of 1 µM WT and mutant proteins in Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, and 10 mM CaCl2 were acquired at 25 °C in a 0.1-cm cuvette at 100-nm/min speed using a Jasco J-815 Spectropolarimeter. The average of at least 20 individual spectra for each sample is shown. The CD signals were deconvoluted by CONTIN software.

Fig. S6.

Analysis by SDS/PAGE of proteins purity. Samples of proteins (10 µg of each protein) purified following the purification protocol described in SI Materials and Methods were electrophoresed and stained with Coomasie blue following standard protocols.

Fig. 4.

ACT–PLA has Gly-X-Ser-X-Gly hydrolase motif. PLA1 (A) and PLA2 (B) activities of intact ACT, and of the ACT mutants S606A and D1079A, as a function of the corresponding protein concentration (0–40 nM), were determined using the method of the PLA1- and PLA2-specific fluorogenic substrates PED-A1 and PED6. The S606A mutant has a point mutation in the amino acid Ser-606 of the conserved Gly-X-Ser-X-Gly hydrolase motif, which was substituted by an Ala, and the D1079A mutant has a mutation in the Asp-1079 of the Asp-X-Gly/Ala motif. Cleavage of the sn-1 and sn-2 ester bonds was followed as an increase of the fluorescence intensity at 515 nm determined 30 min after incubation with the corresponding protein toxin. Data are expressed as means ± SD (n = 3) from at least three independent experiments.

Table S1.

Comparison of the different activities elicited by WT ACT, ACT-S606A, and ACT-D1079A

| Version of ACT | PLA1 activity* | PLA2 activity† | Hemolysis‡ | Cytotoxicity§ | cAMP (solution)¶ | cAMP (cells)# |

| ACT | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| S606A | + | + | ++++ | + | ++++ | + |

| ++++ | ||||||

| D1079A | ++ | ++++ | + | + | ++++ | + |

The number of plus signs refers to the overall hemolytic activity of the corresponding ACT construct relative to WT ACT. + corresponds to 0–2 nM mutant concentration and ++++ corresponds to concentrations ≥2 nM.

PLA1 activity of the corresponding protein was determined using as lipid substrate PEDA1 as specified in SI Materials and Methods. The lipid:protein ratio used in the assays was 1,000:1. Changes of the fluorescence intensity were determined after 30-min incubation with the protein at 37 °C.

PLA2 activity of the corresponding protein was determined using as lipid substrate PED6 as specified in SI Materials and Methods. The lipid:protein ratio used in the assays was 1,000:1. Changes of the fluorescence intensity were determined after 30-min incubation with the protein at 37 °C.

The hemolytic activity on sheep erythrocytes (108 cells/mL) was determined upon 4.5-h incubation at 37 °C, as described in Gray et al. (62).

Cytotoxicity induced by the corresponding protein was determined as LDH release from J774A.1 cells upon incubation with the toxin for 2 h at 37 °C.

Production of cAMP in solution, by the corresponding protein was quantified as specified in SI Materials and Methods.

Production of cAMP in J774A.1 cells, by the corresponding protein was quantified as specified in SI Materials and Methods.

In Vivo ACT–PLA Activity.

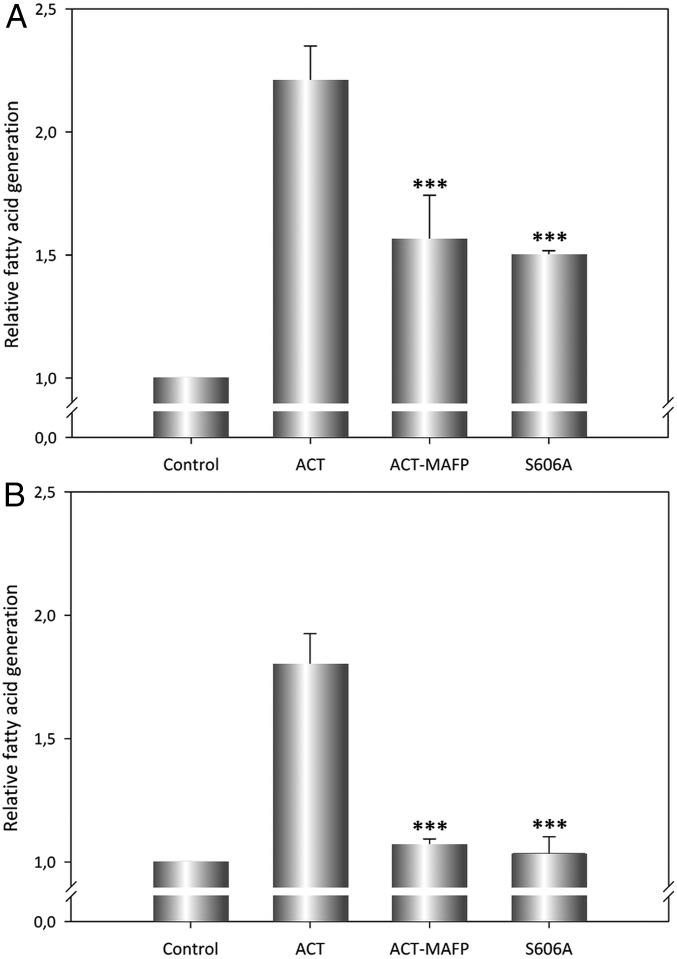

To investigate whether ACT exerts lipid acyl hydrolase activity in vivo, enzyme assays were next conducted in J774A.1 macrophages exposed to the toxin. To this end, we first labeled the cell membranes with tritiated arachidonic acid by an overnight incubation of the phagocytes (1 × 105 cells) in medium with 3H-arachidonic acid (1.5 µCi/106 cells) at 37 °C. Upon extensive cell washing, cells were then incubated with ACT (20 nM) for 10 min at 37 °C. After that incubation time, a solution of chloroform:methanol (1:1) was added to extract lipids, and then separation of free fatty acids from phospholipids (40) was carried out by TLC. Radioactivity in the sample extracted was quantified by scintillation counting. About 2- to 2.5-fold more 3H-arachidonic acid was detected in the samples exposed to ACT compared with control untreated cells (Fig. 5A), indicating that ACT exhibits PLA activity in vivo as well. As expected, the release of tritiated free AA from the J774A.1 cell membrane was notably reduced upon overnight preincubation of ACT with MAFP (Fig. 5A), thus corroborating the ACT–PLA activity features observed previously in the in vitro assays.

Fig. 5.

In vivo ACT–PLA activity. PLA activity of ACT was determined in macrophages by quantification of free [3H]-arachidonic acid released from J774A.1 cells upon treatment with ACT for 10 min, as described in SI Materials and Methods. (A) PLA activity of intact ACT (20 nM), of ACT (20 nM) preincubated with the PLA inhibitor MAFP (25 µM), and of the ACT mutant S606A (20 nM) was determined by the same procedure and graphically depicted as the ratio of scintillation counting relative to control untreated cells. (B) Cells were first preincubated with a combination of inhibitors of cytosolic and secreted PLA (MAFP + LY311727; each inhibitor at 25 µM) and then cells were treated with ACT, or ACT preincubated with MAFP (25 µM), or S606A proteins (20 nM), and upon 10-min incubation free [3H]-arachidonic acid released was quantified. Average values ± the SEM (n = 3) are shown. ***P < 0.001 with respect to intact ACT.

Also as expected, the release of tritiated fatty acid was significantly reduced in cells exposed to the inactive S606A mutant (Fig. 5A). However, this inhibition by MAFP or mutation (S606A) observed in vivo was apparently less efficient than the observed in the in vitro assays (Figs. 3 and 4). We hypothesized that because eukaryotic cells contain endogenous PLAs, some of which are Ca2+-dependent (41), it might be that part of the tritiated AA determined in our in vivo assays could come from the activity of such cellular PLAs. To settle the issue, we performed a control assay in which cells were preincubated with known inhibitors of both cytosolic and secretory cellular PLAs, MAFP and LY311727, respectively, prior to their treatment with ACT, ACT+MAFP, or ACT-S606A. Data from this experiment, depicted in Fig. 5B, confirmed our hypothesis and explained the apparent lower efficacy of inhibition. Fig. 5B shows, first, that as consequence of the inhibition of the cellular PLA2, the total amount of free arachidonic acid quantified was inferior (≈1.7 times the control vs. 2.3 times the control), and second, that the inhibitory effect of MAFP or the point mutation ACT-S606A was now almost complete. In cells incubated with a lower ACT concentration (1.5 nM), the pattern observed was very similar, except that in this case the contribution of the intracellular phospholipases was inferior (Fig. S7). We can thus state that ACT exhibits PLA activity in vivo, releasing free fatty acids into the membrane. A striking finding here is that treatment of monocytes with ACT promotes activation of cellular PLAs. We speculate that this activation might be mediated through ACT capacity to induce Ca2+ elevations into target cells, which is greater the higher the toxin concentration is (42). Elucidation of the potential biological consequence of such activation in target cells needs further investigation.

Fig. S7.

(A and B) Quantification of the free [3H]-arachidonic acid released upon incubation of macrophages with ACT. PLA activity of ACT in macrophages was determined by quantification of free [3H]-arachidonic acid released from J774A.1 cells upon treatment with ACT (1.5 nM) for three different incubation times, as described in SI Materials and Methods. Results are graphically depicted as the ratio of scintillation counting at each incubation time, relative to control untreated cells. Average values ± the SEM (n = 3) are shown.

ACT–PLA Activity Is Involved in AC Domain Translocation.

To understand the biological consequence of the novel ACT phospholipase activity, we hypothesized that it might modulate cellular processes related to membrane remodeling. Lysophospholipids, one of the end products of the PLA activity, are nonlamellar lipids with intrinsic positive curvature (43), and formation of nonlamellar structures in the membrane is thought to be one way for “lipid pores” to occur in it (44). Moreover, insertion of amphipathic regions of many cellular proteins is now recognized as possibly resulting in the formation of hybrid proteolipidic “toroidal pores” by contributing to the fusion of inner and outer bilayer leaflets, in a way that is analogous to the effect on a pure lipid system of an external charge or the presence of detergents (45–47).

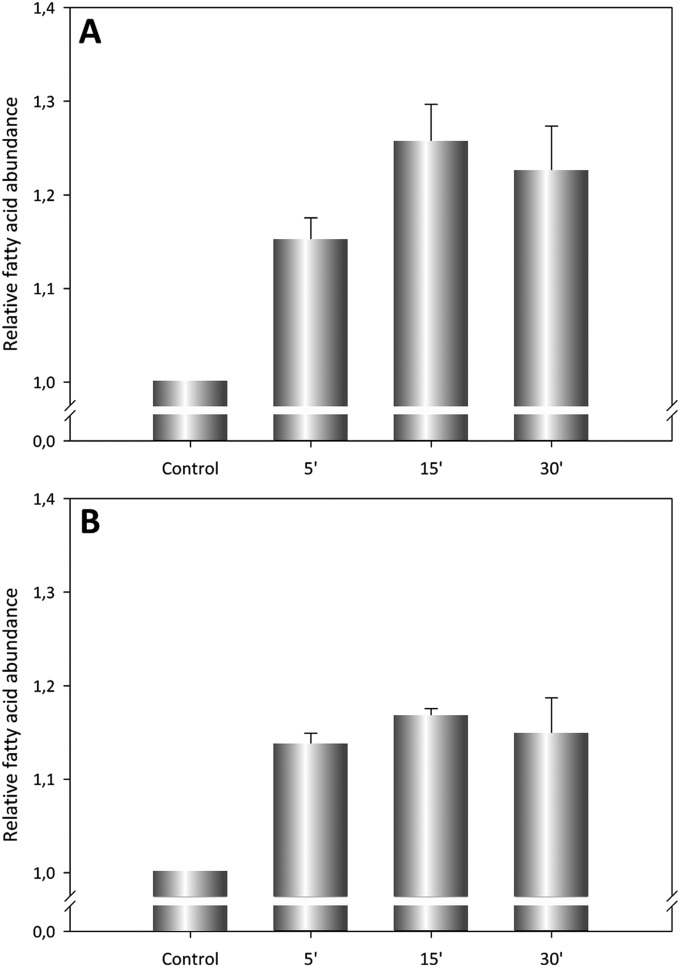

With this basis, we explored the possibility that ACT–PLA activity could contribute in vivo to AC domain translocation by inducing membrane-remodeling effects through the generation of lysophospholipids into the cell membrane. As a measure of the AC domain translocation efficiency, we quantified the intracellular cAMP accumulation induced by intact ACT (5 nM), by ACT preincubated with MAFP, and by the mutant proteins S606A (5 nM) and D1079A (5 nM) in J774A.1 macrophages. As shown in Fig. 6A, preincubation of ACT with MAFP abrogated almost completely the accumulation of cAMP into the macrophage cytosol. Possible side effects of the drug on ACT AC enzyme activity were ruled out, because cAMP production in solution by the MAFP-treated ACT was almost identical to intact ACT (Fig. 6B). Similarly, cAMP accumulation was importantly halted in macrophages incubated with the S606A and D1079A mutants, whereas the point substitutions of the catalytic Ser and Asp did not have any effect on the capacity of the respective ACT mutants to generate cAMP in solution (Fig. 6 A and B). Therefore, these results proved that ACT is not capable of translocating efficiently its AC domain into the host cytosol if the toxin intrinsic PLA activity results abrogated, both chemically (MAFP) or by mutagenesis. Thus, this set of experiments demonstrated a direct causal relationship between ACT–PLA activity and AC domain translocation.

Fig. 6.

ACT–PLA activity is involved in AC domain translocation. The catalytic activities of intact ACT, ACT preincubated with MAFP, and of the ACT mutants S606A and D1079A, were measured in J774A.1 cells (A) or in solution (B) at a toxin concentrations of 5 nM and 1 nM, respectively, and expressed as picomole cAMP generated per microgram of the corresponding protein. The control sample corresponds to the cAMP amount measured in untreated cells. The cyclase activity was determined as described in SI Materials and Methods. Calcium-dependence of ACT–PLA1 activity was measured for the three proteins, ACT, ACT-S606A, and ACT-D1079A, by the method of the fluorogenic substrate PED-A1, as a function of the calcium concentration, and expressed as relative fluorescence values (515 nm) in a.u. (C). Average values ± the SEM (n = 3) are shown. ***P < 0.001 with respect to intact ACT.

One uncontestable feature of the AC domain translocation process is the requirement of calcium in the millimolar range. To determine whether the ACT–PLA activity was calcium-sensitive, the hydrolysis of the fluorogenic substrates was assayed in buffers with different CaCl2 concentrations, We found that the acyl hydrolase activity of ACT (PLA1 and PLA2) required Ca2+ in the millimolar range (Fig. 6C), thus indicating that ACT is a calcium-dependent PLA. This was a key finding, because this dependence of the ACT–PLA activity for calcium may rationally explain at the molecular level the strict requirement shown by the AC translocation process for this divalent cation.

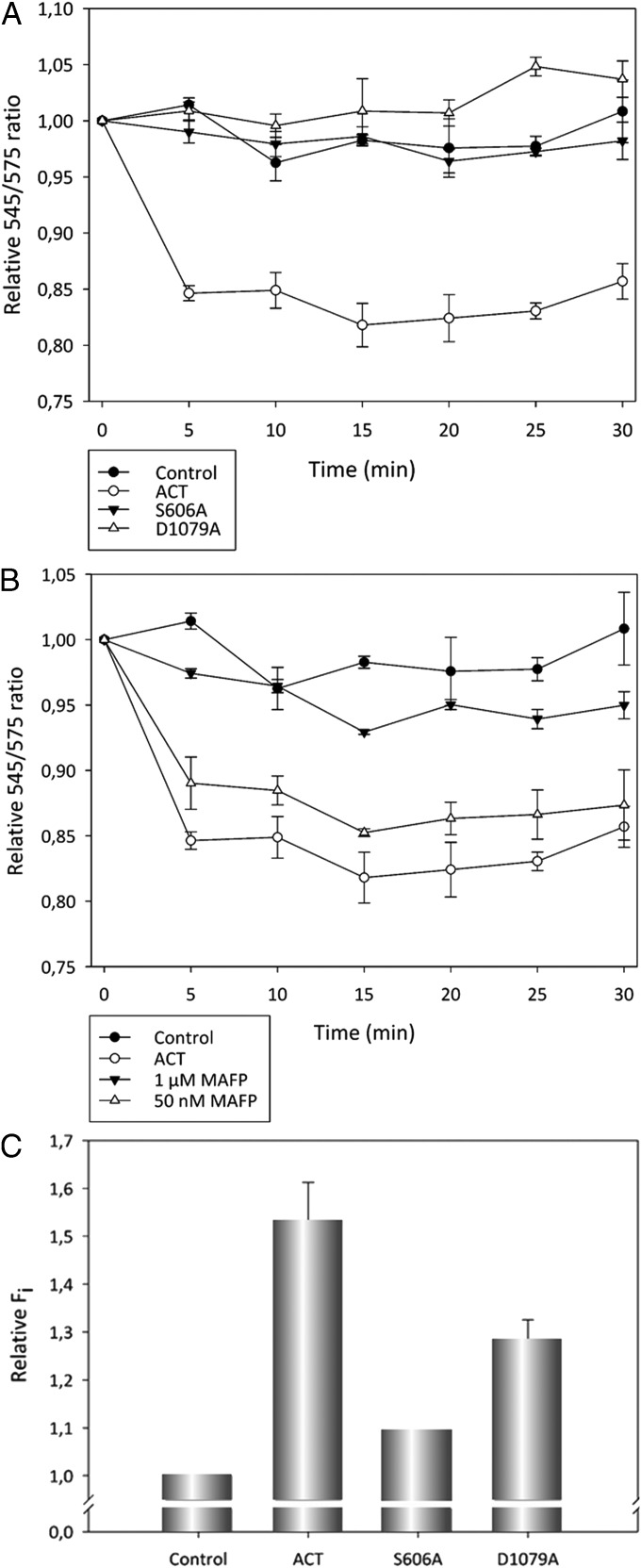

Finally, we wanted to corroborate whether the mechanism by which the ACT–PLA activity dictates AC translocation is based on the membrane remodeling capacity of the lipid hydrolase action. With this aim, we determined the capacity of ACT to induce transbilayer lipid motion in DOPC vesicles, using for that a flip-flop assay previously adapted for this purpose in our laboratory (32). This assay is based on the phenomenon of FRET (32). In the present case, the donor and acceptor are, respectively, 7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl (NBD) and rhodamine. NBD is bound to a phospholipid initially located only in the inner monolayer of the membrane, and rhodamine is bound to a large protein (antibody) located outside the vesicle, so that at time 0 no energy transfer can occur. However, if transbilayer lipid motion occurs, some of the NBD lipid is transferred to the outer monolayer and can interact with the external, protein-bound rhodamine, thus decreasing the fluorescence signal at 545 nm, the maximum of NBD emission. As expected, addition of ACT (10 nM) to DOPC liposomes induced a rapid reduction of the fluorescence signal at 545 nm, in a time scale of minutes (Fig. 7A), consistent with ACT capacity to promote lipid flip-flop, as previously noted by our group (32). In contrast, no changes in the fluorescence signal were detected upon addition of S606A or D1079A mutant proteins to liposomes (Fig. 7A), reflecting that the membrane restructuring capacity of ACT is directly linked to its intrinsic PLA activity. We provide a control of binding (Fig. S8) for the three proteins used in the flip-flop assay, from which we ruled out that mutations on Ser-606 or Asp-1079 had gross effects on the ability of those proteins to bind to the liposome membranes.

Fig. 7.

ACT induced membrane remodeling (lipid flip-flop) in liposomes and in macrophages. Time course of changes in fluorescence intensity of NBD represented as the ratio of the fluorescence intensities of the probe at 545/575 nm, in control liposomes or upon incubation of LUVs with WT ACT or with the ACT–PLA inactive mutants S606A and D1079A. Lipid concentration was 0.1 mM. ACT was added at 100 nM and liposomes were composed of DOPC and NBD-PE (DOPC:NBD-PE, 1,000:6 molar ratio) (A). Effect of two different concentrations (50 nM and 1 µM) of the irreversible inhibitor MAFP on the ACT flip-flop activity is shown. Lipid and protein concentrations were as above (B). Externalization of the lipid PS to the outer monolayer of the cell membrane of macrophages, determined by flow cytometry as annexin V staining, by ACT, ACT-S606A, and ACT-D1079A. Macrophages were incubated at 37 °C with the respective toxin at a concentration of 5 nM, for 10 min. The control represents cells that were treated with medium without toxin (C). Average values ± the SEM (n = 3) are shown.

Fig. S8.

Binding of WT ACT and the ACT mutant proteins, ACT-S606A and ACT-1079A, to DOPC liposomes. Binding of the three proteins to liposomes composed of DOPC was determined upon incubation of the vesicles with the respective toxins at a protein:lipid molar ratio of 1:1,000, for 30 min at 37 °C. Immunostaining with the antibody 9D4 was used for protein staining.

The concentration-dependent inhibitory effect of MAFP on the transbilayer lipid motion induced by ACT (Fig. 7B) was a further corroboration of the relation between ACT–PLA activity and membrane remodeling ability of ACT. This direct interrelation between both processes was furtherly proved into target cells, in which we could detect, through the widely used method of annexin V staining, that a few minutes (0–10 min) after the treatment of J774A.1 monocytes with ACT (5 nM), phosphatydylserine (PS; a phospholipid normally located in the cytoplasmic monolayer), was significantly located in the outer monolayer of the plasma membrane (Fig. 7C), and was reaffirmed by the experiments using the PLA inactive mutants ACT-S606A and ACT-D1079A, which were almost unable to promote such transmembrane lipid movement in the treated macrophages (Fig. 7C). Taken together, these results constitute a very solid indication that AC translocation relies on the generation of nonlamellar intermediates in the cell membrane by the ACT–PLA activity.

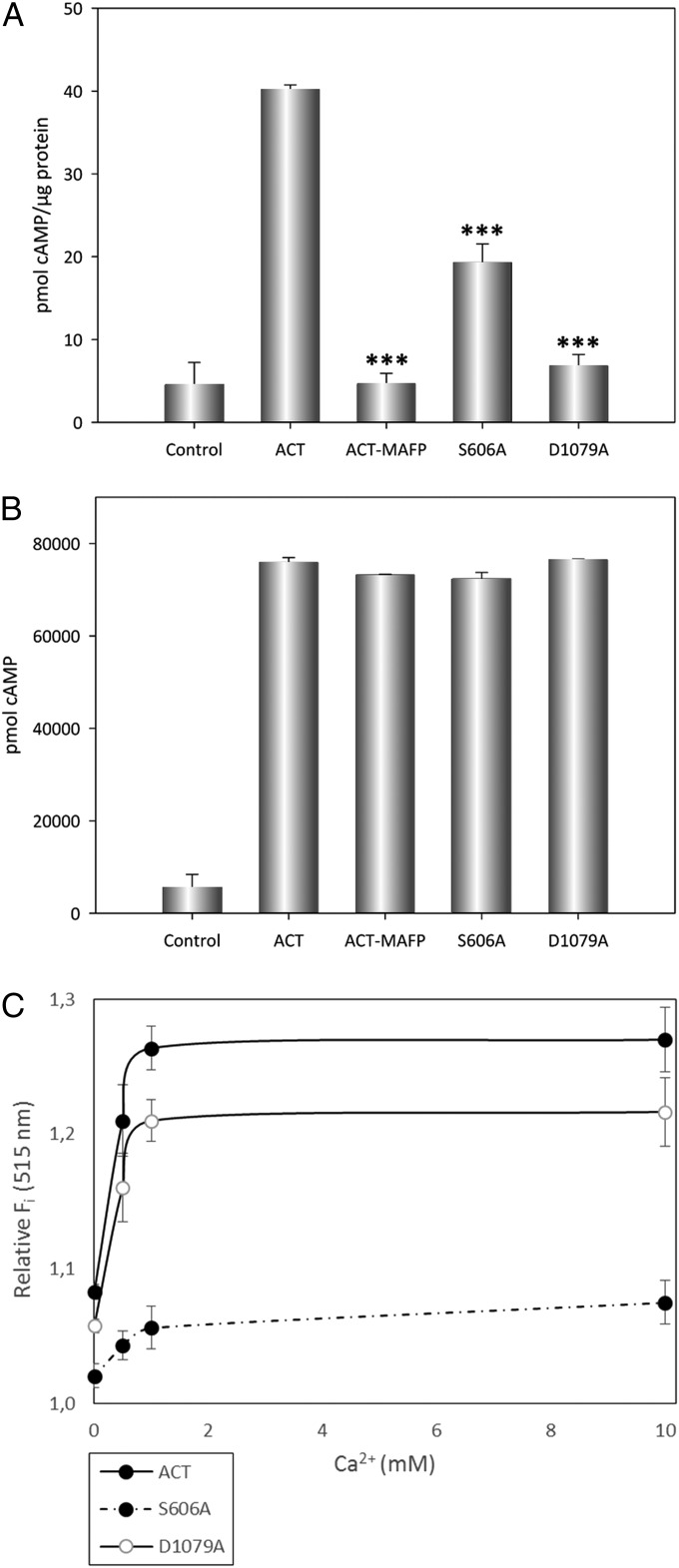

ACT–PLA Activity Is Instrumental to Induce Cell Cytotoxicity.

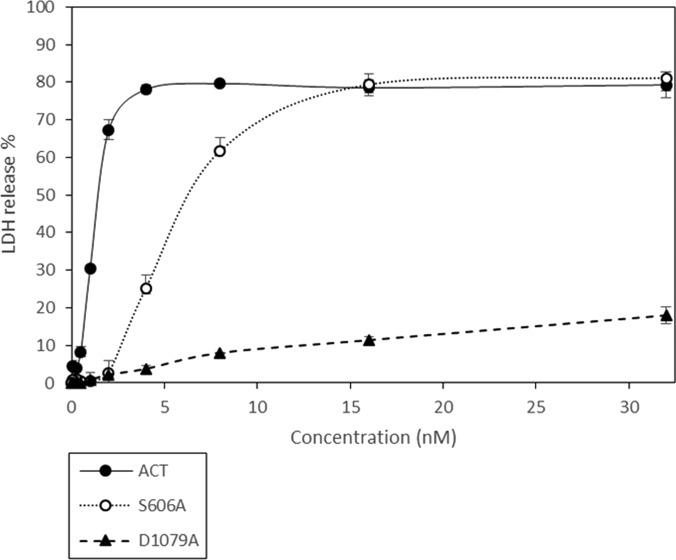

Toxic action of ACT on phagocytes results primarily from the cytotoxic signaling of toxin-produced cAMP (12). Because production of cAMP into the host cell cytosol requires AC domain translocation, we hypothesized that ablation of the ACT–PLA activity would redound in a lower ACT cytotoxicity on macrophages. Therefore, we examined the effect of eliminating the ACT–PLA activity on the ACT-induced cytotoxicity, measured as lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release. If PLA activity is necessary for AC translocation, treatment of J774A.1 cells with the PLA-deficient S606A or D1079A ACT mutants would be expected to be less deleterious to cells. As shown in Fig. 8, intact ACT induced a progressive, concentration-dependent increase in cell cytotoxicity, inducing the release of LDH in about 70% of the cells after 2 h at a toxin concentration of 2 nM. In contrast, the PLA-deficient mutant ACT-S606A did not result in cytotoxicity at this same range of toxin concentrations (0–2 nM) (Fig. 8). Only at toxin concentrations above 2–4 nM did the cytoxicity induced by the PLA-deficient mutant ACT-S606A become substantial, very likely because of its intact pore-forming activity, which has been reported that at this higher toxin concentrations synergizes with cAMP generation and ATP depletion in inducing cell death (9). The cytotoxicity induced by the ACT-D1079A mutant was almost negligable at both toxin concentration ranges (0–2 nM and ≥2 nM), very likely because besides the PLA deficiency, this point mutation decreases the toxin hemolytic potency as well (Table S1), which contributes more importantly to general toxicity at the higher toxin concentrations (9). According to a recent study performed in a baboon model of infection (48), at the bacterium–target cell interface during infection of the respiratory tract, the concentration of ACT can be around 100 ng/mL (≈0.5–1 nM); thus, our results indicated that PLA activity is instrumental for ACT to be cytotoxic, particularly at toxin concentrations close to biological reality of bacterial infection.

Fig. 8.

Cell toxicity induced by low ACT concentrations requires toxin intrinsic PLA activity. Cytotoxicity induced by WT ACT or by the ACT mutants S606A and D1079A, in J774A.1 phagocytes after 2-h incubation at 37 °C, as a function of toxin concentration is depicted. Cell cytotoxicity was determined through release of LDH into the culture medium, and is expressed as percent LDH released into the medium relative to the total LDH content, after 2-h incubation at 37 °C. Average values ± the SEM (n = 3) are shown.

Discussion

In this study, we decipher a fundamental event underlying the hitherto elusive and unique mechanism of translocation of the B. pertussis ACT.

We discover that ACT bears intrinsic PLA activity, both in vitro and in vivo. Our in vitro results obtained by means of two different biophysical techniques, highly sensitive fluorescent lipid substrates and MS, concur and clearly demonstrate that ACT hydrolyzes both the sn-1 and the sn-2 ester bonds of glycerophospholipid substrates, thus releasing into the membrane free fatty acids and lysophospholipids (Figs. 1 and 2). The comparison of the efficiencies of the respective catalytic activities clearly indicates, however, that ACT cleaves with notably more efficiency the sn-1 ester bond of glycerophospholipid substrates, suggesting that ACT most likely acts as a PLA1 on natural membranes. Although many of the known PLA1 also display LysoPLA activities, we could not detect lysophospholipase activity in ACT (Fig. S2). Interestingly, our data also suggest that a “product inhibition” or “feedback-like” mechanism might operate in the ACT–PLA activity (Fig. 2). This may be a relevant characteristic for the ACT–PLA mechanism, as we explain later, as it suggests that the ACT–PLA activity is not to massively “destroy” the target cell outer membrane lipids, but quite the opposite: that this ACT lipid hydrolytic activity has likely evolved as a “security mechanism” by inducing a local, subtle and “surgical” effect on the cell membrane of the target cells. The in vivo data obtained upon treatment of target macrophages with ACT (Fig. 5) are fully consistent with the in vitro results, and prove that ACT releases free fatty acids from the macrophage cell membrane in the same toxin concentration range in which it becomes cytotoxic for cells. Interestingly, we note here that ACT binding to target cells activates endogenous cellular Ca2+-sensitive PLAs (Fig. 5), most likely through its capacity to induce Ca2+ influx. At present, the biological consequences of such activation are unknown.

From the analysis of the toxin sequence, we conclude that ACT shares sequence similarity with members of the patatin-like phospholipases and mammalian cPLA2 (Fig. S4), suggesting that ACT may belong to the esterase/lipase hydrolase superfamily (37). Consistent with this, we identify in the ACT toxin sequence two conserved active-site catalytic motifs, namely, the GAS606AG sequence (consensus motif GXSXG) and D1079GG sequence (consensus motif DXG/A), and by means of pharmacological inhibition and site-directed mutagenesis, we provide evidence of the direct involvement of both Ser-606 and Asp-1079 as essential catalytic residues in the ACT–PLA1 activity (Figs. 3–5), and thus we validate that ACT is a serine acylhydrolase.

A first characterization of the substrate specificity of the ACT–PLA activity shows that ACT may hydrolyze in vitro both neutral and anionic phospholipids (Fig. S3) with similar efficiency, suggesting that ACT–PLA may not have a clear substrate specificity for any given phospholipid in the likeness of the patatin PLA enzyme (49). Recently, it has been shown that the so-called ABH effector domain of the Vibrio cholerae MARTX toxin, another member of the RTX family of proteins to which ACT toxin belongs, possess PLA1 activity (50). Relative to the ACT–PLA activity, ABH appears to be highly specific for its phospholipid substrates, cleaving preferentially phosphatidylinositols, in particular PI3P (50). Compared with ACT however, ABH takes several hours to hydrolyze PI3P (50), which might perhaps be because of an in vivo ABH requirement of some yet unknown intracellular cofactor. As shown here however, ACT–PLA does not require any extracellular or intracellular cofactor other than calcium to rapidly hydrolyze common membrane phospholipids; and given that ACT acts on the cell membrane outer monolayer where PC—in particular POPC and DOPC—are the most abundant glycerophospholipids, we hypothesize that PC could be an in vivo likely ACT–PLA lipid substrate.

Of great significance in the ACT context is the elucidation here of the biological consequence of this novel ACT–PLA activity, that ACT lipid hydrolytic activity is directly linked to the AC domain transport across the plasma membrane of target phagocytes. Two types of experiments allow us to conclude this. First, the sole inhibition of the ACT–PLA activity by MAFP prevents totally the accumulation of cAMP into the cytosol of the target cells, whereas it does not affect at all of the ACT production of cAMP in solution, thus proving that MAFP does not interfere with this second enzymatic activity of ACT (Fig. 6). Second, eradication of the ACT–PLA1 activity by introduction of a point substitution in the consensus catalytic center (S606, D1079) equally halts the accumulation of cAMP into the target cytosol (Fig. 6), whereas the mutated proteins remain fully functional in generation of cAMP in solution (Table S1). Hence, all of the results concur that AC transport across the membrane relies and is directly coupled to the hydrolysis of membrane phospholipids by ACT itself. Consistent with this essential role of the ACT–PLA activity in AC translocation, we show that toxin-induced cell toxicity dramatically decreases in the macrophages treated with PLA-deficient ACT mutant proteins (Fig. 8), particularly at the toxin concentration-range close to biological reality of bacterial infection, indicating that PLA activity is instrumental for ACT cytotoxicity.

A key question here is how the ACT–PLA activity may mechanistically allow the transference of the AC domain across the plasma membrane. The reaction products of ACT–PLA activity on plasma membrane phospholipids are lysophospholipids and free fatty acids. For decades it has been widely recognized that the modification of the cell-membrane composition through the direct action of hydrolytic enzymes, such as phospholipases on membrane lipids, may regulate cell-membrane physical properties, such as the membrane mechanical stretching and bending constants (51), membrane curvature, or membrane lateral organization, favoring the formation of transient nonlamellar structures (52–56). Lysophospholipids, nonlamellar lipids with positive spontaneous curvature, have been proven to induce formation of hydrophilic permeable proteolipidic “toroidal pores” in membranes in which amphipathic peptides and proteins are inserted, via a decrease in line tension within the lipid bilayer because of relief of curvature stress along the membrane edge of the pore wall (44, 57). By definition, in a toroidal pore its constituent monolayers become continuous via the pore-lining lipids (44, 57), and thus this structure allows the movement of lipid molecules from one monolayer of the bilayer to the other. Here we provide evidence that ACT–PLA activity is directly involved in promoting transbilayer lipid motion both in pure phosphatidylcholine liposomes and, moreover, also in macrophages, and prove that this is the direct inhibition of such ACT-induced lipid scrambling (flip-flop) by MAFP and point mutations in the PLA catalytic sites (Fig. 7), thus indicating that ACT–PLA activity could form in the lipid bilayer toroidal pores. Therefore, we provide herein an explanation to the question of how ACT–PLA activity may dictate AC domain transport through the plasma membrane. We postulate that in situ generation of nonlamellar lysophospholipids by ACT–PLA activity on plasma membrane phospholipids would form a hydrophilic lipid pore of toroidal architecture through which AC domain transfer could directly take place. The location of the catalytic Ser-606 within one of the predicted α-helices (helix IV) of the so-called hydrophobic pore-forming domain of ACT, leads us to plausibly hypothesize, that such a hydrophilic lipidic pore might be of proteolipidic nature, constituted likely by both lipids and one or more helical segments of the pore-forming region. Consistent with this idea, others have previously noted that mutations in specific amino acids of several α-helices from the hydrophobic domain impair not only the hemolytic activity, but also the translocation capacity of ACT (21).

Our translocation model is also consistent with the extraordinary versatility of the AC domain to transport into the cytosol of CD11b+ target cells large heterologous cargo polypeptides of up to 200 residues in length within the AC domain (23, 26), as among the unique characteristics of the proteolipidic toroidal pores are structural flexibility, low selectivity, and variable size (44, 57). Direct participation in AC domain translocation of an ACT–PLA-generated hydrophilic toroidal tunnel, in which the pore-walls may in part be lined by phospholipid head groups, may also be consistent with previous observations showing a net positive charge requirement for AC domain to be translocated (58). Moreover, the possible formation of ion couples among those positively charged amino acid lateral chains with negatively charged phospholipid and fatty acid headgroups exposed at the pore walls may represent an energy source that might contribute to lowering the energy barrier for the AC domain insertion within the lipid bilayer (59, 60).

Remarkably, our results may substantiate—at the molecular level—previous data on calcium dependence of the ACT catalytic domain translocation in eukaryotic cells (20), and this is a critical aspect that previous models on AC transport have failed to explain convincingly (20, 29). We show indeed that to be fully operative, the ACT–PLA activity requires calcium in the millimolar range, thus providing a straightforward explanation to the strict calcium dependence of the AC transport across the cell membrane (20). It is tempting to speculate that the requirement of a cofactor, such as calcium ions for the ACT–PLA activity, might be linked to the absence of toxicity of ACT when expressed in bacteria, acting somehow as a security mechanism for the prokaryotic cell.

A model cited in the ACT field to explain AC translocation is the two-step model proposed by Bumba et al. (29), in which in a first step, and upon ACT binding to its CD11b/CD18 integrin receptor, a translocation-competent ACT conformer would conduct extracellular Ca2+ ions across the plasma membrane, which it would activate a calpain-mediated cleavage of talin, releasing the ACT–integrin complex from the cytoskeleton. In a second step, this ACT–integrin complex would move into lipid rafts, and there the cholesterol-rich lipid environment would promote the translocation of the AC domain across the cell membrane (29). However, this model cannot explain convincingly the uncontestable dependence shown by the AC domain transport for millimolar calcium concentrations, because at very low ACT concentrations (<100 ng/mL) at which AC translocation is supposed to be physiologically more relevant for cytotoxicity, the intracellular calcium elevation induced by ACT is nearly null. Another feature also difficult to explain by Bumba et al.’s (29) model is how ACT can successfully transport, upon fusion to the C-terminal ACT-hemolysin domain, such a variety of N-terminal polypeptides carrying such different sequences and lengths. A path that has to assist indistinctly the translocation of a 400 amino acids-long chain or of other different polypeptides has to be expectedly dynamic, adaptable, and versatile, and these are typically features shared by lipid/protolipid toroidal pores, such as the ones that may be generated by a local PLA activity, as the ACT–PLA activity revealed here.

In conclusion, this study reveals intrinsic PLA activity of ACT that explains a fundamental molecular event underlying ACT protein translocation. The coupling in a single molecule of membrane remodeling capacity—given by an enzymatic activity—with the transport of proteins across membranes is unprecedented. Because delivery of the AC domain is essential for ACT-induced cell toxicity, regulation of the ACT–PLA activity emerges as a novel drug target for the therapeutic control of whooping cough, an infectious disease that is the fifth largest cause of vaccine-preventable death in infants.

Materials and Methods

Expanded methods are available in SI Materials and Methods.

In vitro PLA activity was assayed using TLC and ulterior densitometric analysis, UHPLC-MS analysis, and selective fluorogenic phospholipid substrates: namely, PED-A1 and PED6. For the in vivo PLA activity determination, cellular lipids were labeled with [3H]-arachidonic acid. Lipid flip-flop was assessed by FRET using NBD-PE and rhodamine as donor and acceptor, respectively.

SI Materials and Methods

Production and Purification of ACT.

ACT was produced in Escherichia coli XL-1 blue cells (Stratagene) transformed with plasmid pT7CACT1, kindly provided by Peter Sebo, Institute of Microbiology of the Czech Academy of Science, v.v.i., Prague, Czech Republic. ACT purification was performed according to the method described in Karst et al. (61). Exponential 500-mL cultures were grown at 37 °C and induced by isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (IPTG, 1 mM) for 4 h before the cells were washed with 50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, and disrupted by sonication. Nonbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 2,500 × g for 5 min and the supernatant was centrifuged at 25,000 × g for 20 min. The pellet was then resuspended in 8 M urea, 50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM CaCl2. Upon centrifugation at 25,000 × g for 20 min, clarified urea extracts were submitted to several chromatrography steps, as described in Karst et al. (61). All toxins purified by this method were more than 90% pure as judged by SDS/PAGE analysis and contained less than one endotoxin unit of LPS per microgram of protein, as determined by a standard Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (Lonza). Concentrations of purified ACT proteins were determined by the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad) using BSA as standard. Protein from at least two different purifications was used in the experiments.

Construction, Expression, and Purification of the ACT Mutants ACT-S606A and ACT-D1079A.

The catalytic variants of ACT S606A and D1079A were cloned, expressed, and purified from E. coli. cyaA DNA was amplified from genomic DNA by and cloned in pET-15b (Novagen) using BamH1 and Xhol enzymes to generate plasmid pME14. Site-directed mutagenesis according to Agilent protocol was performed on pME14 to replace Ala codons for Ser-606 and Asp-1079. Forward and reverse primers for S606A mutant were 5′ GTGGCCGGGGCGGCGGCCGGGGCGG 3′ and 5′ CCGCCCCGGCCGCCGCCCCGGCCAC 3′ respectively, and for D1079A were 5′ GCAACCAGCTCGCTGGCGGCGCGGG 3′ and 5′ CCCGCGCCGCCAGCGAGCTGGTTGC 3′. All plasmid inserts were sequenced to confirm accuracy of PCR and mutagenesis. For protein expression, E. coli BL21 transformed with pME14 plasmid was grown in LB with 100 μg⋅mL−1 ampicilin to A600 = 0.6–0.8 and protein expression was induced by 4-h growth in 1 mM IPTG. Protein purification was performed according to the method described in Karst et al. (61). Concentrations of purified ACT proteins were determined by the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad) using BSA as standard. All toxins purified by this method were more than 90% pure as judged by SDS/PAGE analysis, and contained less than one endotoxin unit of LPS per microgram of protein as determined by a standard Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (Lonza). SDS/PAGE gel performed with the purified protein samples is provided in Fig. S6.

Circular Dichroism.

Far UV CD spectra of 1 µM WT and mutant proteins in 20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, and 10 mM CaCl2 were acquired at 25 °C in a 0.1-cm cuvette using Jasco J-815 spectropolarimeter. Twenty individual spectra were averaged for each sample. The CD signals were de-convoluted by CONTIN software. The samples were measured for wavelengths from 200 to 260 nm at standard instrument sensitivity and a scanning speed of 100 nm/min. The resulting spectra were obtained by subtracting the spectrum of the buffer from the spectrum of the protein solution.

UHPLC-MSE Analysis.

For UHPLC-MSE analysis, 100 µM POPC LUVs were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C with 100 nM ACT in buffer (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris⋅HCl, 10 mM CaCl2, pH 8.0). Then lipids were extracted by addition of a chloroform:methanol 3:1 (vol:vol) solution, and analyzed by UHPLC.

UHPLC was carried out by using an ACQUITY UPLC system from Waters, equipped with a binary solvent delivery pump, an autosampler, and a column oven. The extracts were injected onto a column (Acquity UPLC HSS T3 1.8 μm, 100 × 2.1 mm) from Waters, which was heated to 65 °C. Mobile phases consisted of acetonitrile and water with 10 mM ammonium acetate [40:60 (vol/vol); phase A] and acetonitrile and isopropanol with 10 mM ammonium acetate [10:90 (vol/vol); phase B]. Separation was carried out in 13 min under the following conditions: 0–10 min, linear gradient from 40 to 100% B; 10–11 min, 100% B; and finally, reequilibration of the system with 40% B (vol/vol) for 2 min before the next injection. Flow rate was 0.5 mL/min and injection volume was 1 μL. All samples were kept at 4 °C during the analysis. All UHPLC-MSE data were acquired on a SYNAPT G2 HDMS, with a quadrupole time of flight (Q-ToF) configuration, (Waters) equipped with an ESI source that can be operated in both positive and negative modes. The capillary voltage was set to 0.7 kV (ESI+) or 0.5 kV (ESI−). Nitrogen was used as desolvation and cone gas, at flow rates of 900 L/h and 30 L/h, respectively. The source temperature was 120 °C, and the desolvation temperature was 400 °C.

Leucine-enkephalin solution (2 ng/μL) in acetonitrile:water [50:50 (vol/vol) + 0.1% formic acid] was used for the lock-mass correction and the ions at m/z 556.2771 and 278.1141, or 554.2615 and 236.1035, depending on the ionization mode, from this solution were monitored at scan time 0.3 s, and at 10-s intervals, three scans on average, using a mass window of ±0.5 Da. The rest of the conditions were: lockspray capillary 2.0 and 2.5 kV and collision energy 21 and 30 eV in ESI+ or ESI−, respectively. The reference internal calibrant was introduced into the lock mass sprayer at a constant flow rate of 10 μL/min, using an external pump. All acquired spectra were automatically corrected during acquisition using the lock mass. Before analysis, the mass spectrometer was calibrated with a sodium formate 0.5 mM solution. Data acquisition took place over the mass range 50–1,200 atomic mass units in resolution mode (FWHM ≈ 20,000) with a scan time of 0.5 s and an interscan delay of 0.024 s. The cone voltage was set to 35 V (ESI+ and ESI−). The mass spectrometer was operated in the continuum MSE acquisition mode for both polarities. During this acquisition method, the first quadrupole Q1 is operated in a wide band rf mode only, allowing all ions to enter the T-wave collision cell. Two discrete and independent interleaved acquisition functions were automatically created: the first function, typically set at 6 eV, collected low energy or unfragmented data, whereas the second function collected high energy or fragmented data typically obtained by using a collision energy ramp from 15 to 40 eV. In both cases, Ar gas was used for collision-induced dissociation.

In Vitro Phospholipase A Activity Assay with Fluorogenic Lipid Substrates.

Highly sensitive and selective fluorogenic phospholipid substrates namely, PED-A1 (Thermofisher Scientific) and PED6 were used to determine PLA1 and PLA2 activities, respectively. Briefly, liposomes of DOPC containing PED-A1 or PED6 at a 20% molar ratio (final total lipid concentration 10 µM) were incubated with the toxin (10 nM) in 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris⋅HCl, 10 mM CaCl2, pH 8.0 buffer, at 37 °C under constant stirring for 30 min. Changes in fluorescence intensity at 515 nm were measured, with excitation wavelength set at 480 nm and with both monochromator slits at 5 nm.

Determination of Free [3H]-Arachidonic Acid Released in J774A.1 Cells Exposed to ACT.

First, J774A.1 cells were incubated o/n at 37 °C with 1.5 μCi/mL of [3H]-arachidonic acid for labeling of the cellular lipids. Then, the radioactive medium was removed and the cells incubated with fresh, FBS-free medium for 1 h at 37 °C. The assay was then performed by incubating the labeled cells with 1.5 or 20 nM ACT, S606A, or ACT preincubated with MAFP (Sigma) for 10 min, then cells were washed and scraped in methanol (1 mL). Lipids were extracted by separation of phases upon addition of 1 mL chloroform and 0.9 mL 2 M KCl and 0.2 M HCl. The chloroformic phase was the dried and lipids separated by TLC using Silica Gel-60 coated-glass plates. The plates were developed in a single phase consisting of n-heptane:diisopropyl ether:acetic acid 70:30:1 (vol/vol/vol). Position of free fatty acids was determined staining the plates with I2 vapor and comparing the spots of each sample with the free fatty acid control spot. Radioactivity was quantified by liquid scintillation counting after scraping the spots of interest.

Transbilayer Lipid Movement.

The transbilayer lipid movement assay is based on the phenomenon of FRET. When two different fluorophores are in very close proximity, such that the emission spectrum of the first one overlaps the excitation spectrum of the second one, it is possible to excite the fluorescence of the first one (donor) and record the fluorescence emitted by the second one (acceptor). In the present case, the donor and acceptor are, respectively, NBD and rhodamine. NBD is bound to a phospholipid initially located only in the inner monolayer of the membrane, and rhodamine is bound to a large protein (antibody) located outside the vesicle, so that at time 0 no-energy transfer can occur. However, when transbilayer lipid motion occurs, some of the NBD-lipid is transferred to the outer monolayer and can interact with the external, protein-bound rhodamine. To prepare LUV labeled in the inside bilayer with NBD-PE, PC-PE-Ch (2:1:1) LUV containing 0.6 mol % NBD-PE (about 1 NBD-PE molecule in 170 nonfluorescent lipid molecules) were treated with membrane impermeable sodium dithionite (10 mM). The excess dithionite was removed by gel filtration through a Sephadex G-25 column. These NBD-PE–containing liposomes (0.1 mM final concentration) were incubated at 37 °C with the toxin (100 nM) under constant stirring in 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris⋅HCl, 10 mM CaCl2, pH 8.0 buffer. At different times, small aliquots of the suspension were removed and incubated with rhodamine conjugated to an antibody that was also membrane impermeable. Measurements were monitored in a Fluorolog-3 spectrofluorimeter at 37 °C, with a continuously stirred cuvette. Excitation was set at 460 nm, and emission was recorded between 510 and 640 nm, with slits of 5 nm for both monochromators. A cut-off filter (515 nm) was used to prevent contribution from scattered light.

Cell Culture.

J774A.1 macrophages (no. TIB-67; ATTC) were grown at 37 °C in DMEM containing 10% (vol/vol) FBS, and 4 mM l-glutamine in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

Measurement of cAMP.

cAMP produced in solution was assayed in presence of 1 mM calmodulin (CaM) and 5 mM ATP in AC reaction buffer (30 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4, 20 mM MgCl2 and 100 µM CaCl2). Reaction was started by addition of 1 nM ACT, and after 10 min at 37 °C with continuous stirring, the reaction was stopped with 0.1 M HCl. cAMP produced in cells was measured upon incubation of 5 nM ACT with J774A.1 cells (5 × 105 cells/mL) for 30 min at 37 °C. In both cases cAMP production was calculated by the direct cAMP ELISA kit (Enzo Lifesciences).

Cytotoxicity Assay.

Cell viability was determined by the LDH release assay. Briefly, J774A.1 cells were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C with twofold dilutions of toxin in OPTIMEM medium supplemented with 2 mM CaCl2. Upon that incubation time, the plates were centrifuged and supernatants were assayed with LDH Cytotoxicity assay kit (Innoprot). The percentage of LDH released was determined by the equation: % Cytotoxicity = (Experimental − Blank)/Control − Blank) × 100.

Preincubation of ACT with MAFP.

Chemical inhibition of ACT was performed with an overnight incubation at 4 °C with MAFP inhibitor (100:1 MAFP:ACT molar ratio) in a buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris, 10 mM CaCl2, pH 8.0. Because an unbound inhibitor may interfere with the experiments, dialysis of the mixture was done overnight at 4 °C. In all experiments in which the preincubated toxin was used, a parallel sample of ACT following these steps was used as a control to check that the toxin did not undergo degradation.

Statistical Analysis.

All measurements were independently performed at least three times, with n = 3 unless otherwise stated, and results are presented as mean ± SD. Levels of significance were determined by a two-tailed Student’s t test, and confidence level of greater than 95% (P < 0.05) were used to establish statistical significance.

Acknowledgments

We thank the technical and staff support provided by the Servicio de Lipidómica of the SGIker (Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea, Ministeria de Ciencia e Innovación, GV/EJ, European Social Fund) and Rocío Alonso for excellent technical assistance. This study was supported by Basque Government Grants Grupos Consolidados IT849-13 and ETORTEK Program KK-2015/0000089. D.G.-B. and K.B.U. were recipients of a fellowship from the Bizkaia Biophysics Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1701783114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Carbonetti NH. Pertussis toxin and adenylate cyclase toxin: Key virulence factors of Bordetella pertussis and cell biology tools. Future Microbiol. 2010;5:455–469. doi: 10.2217/fmb.09.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mattoo S, Cherry JD. Molecular pathogenesis, epidemiology, and clinical manifestations of respiratory infections due to Bordetella pertussis and other Bordetella subspecies. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:326–382. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.2.326-382.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodwin MSM, Weiss AA. Adenylate cyclase toxin is critical for colonization and pertussis toxin is critical for lethal infection by Bordetella pertussis in infant mice. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3445–3447. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.10.3445-3447.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guermonprez P, et al. The adenylate cyclase toxin of Bordetella pertussis binds to target cells via the alpha(M)beta(2) integrin (CD11b/CD18) J Exp Med. 2001;193:1035–1044. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.9.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berkowitz SA, Goldhammer AR, Hewlett EL, Wolff J. Activation of prokaryotic adenylate cyclase by calmodulin. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1980;356:360. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1980.tb29626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Confer DL, Eaton JW. Phagocyte impotence caused by an invasive bacterial adenylate cyclase. Science. 1982;217:948–950. doi: 10.1126/science.6287574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weingart CL, Weiss AA. Bordetella pertussis virulence factors affect phagocytosis by human neutrophils. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1735–1739. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1735-1739.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehrmann IE, Gray MC, Gordon VM, Gray LS, Hewlett EL. Hemolytic activity of adenylate cyclase toxin from Bordetella pertussis. FEBS Lett. 1991;278:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80088-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hewlett EL, Donato GM, Gray MC. Macrophage cytotoxicity produced by adenylate cyclase toxin from Bordetella pertussis: More than just making cyclic AMP! Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:447–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benz R, Maier E, Ladant D, Ullmann A, Sebo P. Adenylate cyclase toxin (CyaA) of Bordetella pertussis. Evidence for the formation of small ion-permeable channels and comparison with HlyA of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:27231–27239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dal Molin F, et al. Cell entry and cAMP imaging of anthrax edema toxin. EMBO J. 2006;25:5405–5413. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ladant D, Ullmann A. Bordatella pertussis adenylate cyclase: A toxin with multiple talents. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:172–176. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01468-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glaser P, Sakamoto H, Bellalou J, Ullmann A, Danchin A. Secretion of cyclolysin, the calmodulin-sensitive adenylate cyclase-haemolysin bifunctional protein of Bordetella pertussis. EMBO J. 1988;7:3997–4004. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03288.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bellalou J, Sakamoto H, Ladant D, Geoffroy C, Ullmann A. Deletions affecting hemolytic and toxin activities of Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3242–3247. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.10.3242-3247.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakamoto H, Bellalou J, Sebo P, Ladant D. Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin. Structural and functional independence of the catalytic and hemolytic activities. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:13598–13602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hackett M, Guo L, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Hewlett EL. Internal lysine palmitoylation in adenylate cyclase toxin from Bordetella pertussis. Science. 1994;266:433–435. doi: 10.1126/science.7939682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bauche C, et al. Structural and functional characterization of an essential RTX subdomain of Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16914–16926. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601594200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rose T, Sebo P, Bellalou J, Ladant D. Interaction of calcium with Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin. Characterization of multiple calcium-binding sites and calcium-induced conformational changes. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26370–26376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Azami-El-Idrissi M, et al. Interaction of Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase with CD11b/CD18: Role of toxin acylation and identification of the main integrin interaction domain. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38514–38521. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304387200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rogel A, Hanski E. Distinct steps in the penetration of adenylate cyclase toxin of Bordetella pertussis into sheep erythrocytes. Translocation of the toxin across the membrane. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:22599–22605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basler M, et al. Segments crucial for membrane translocation and pore-forming activity of Bordetella adenylate cyclase toxin. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:12419–12429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611226200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gordon VM, et al. Adenylate cyclase toxins from Bacillus anthracis and Bordetella pertussis. Different processes for interaction with and entry into target cells. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:14792–14796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gmira S, Karimova G, Ladant D. Characterization of recombinant Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxins carrying passenger proteins. Res Microbiol. 2001;152:889–900. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(01)01272-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osicková A, Osicka R, Maier E, Benz R, Šebo P. An amphipathic alpha-helix including glutamates 509 and 516 is crucial for membrane translocation of adenylate cyclase toxin and modulates formation and cation selectivity of its membrane channels. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37644–37650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Osickova A, et al. Adenylate cyclase toxin translocates across target cell membrane without forming a pore. Mol Microbiol. 2010;75:1550–1562. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holubova J, et al. Delivery of large heterologous polypeptides across the cytoplasmic membrane of antigen-presenting cells by the Bordetella RTX hemolysin moiety lacking the adenylyl cyclase domain. Infect Immun. 2012;80:1181–1192. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05711-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karst JC, et al. Identification of a region that assists membrane insertion and translocation of the catalytic domain of Bordetella pertussis CyaA toxin. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:9200–9212. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.316166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Subrini O, et al. Characterization of a membrane-active peptide from the Bordetella pertussis CyaA toxin. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:32585–32598. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.508838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bumba L, Masin J, Fiser R, Sebo P. Bordetella adenylate cyclase toxin mobilizes its beta2 integrin receptor into lipid rafts to accomplish translocation across target cell membrane in two steps. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000901. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rogel A, et al. Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase: Purification and characterization of the toxic form of the enzyme. EMBO J. 1989;8:2755–2760. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eby JC, Gray MC, Mangan AR, Donato GM, Hewlett EL. Role of CD11b/CD18 in the process of intoxication by the adenylate cyclase toxin of Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 2012;80:850–859. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05979-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martín C, et al. Membrane restructuring by Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin, a member of the RTX toxin family. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:3760–3765. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.12.3760-3765.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Contreras FX, Sánchez-Magraner L, Alonso A, Goñi FM. Transbilayer (flip-flop) lipid motion and lipid scrambling in membranes. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1779–1786. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gaspar AH, Machner MP. VipD is a Rab5-activated phospholipase A1 that protects Legionella pneumophila from endosomal fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:4560–4565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316376111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamura M, et al. Lysophospholipase A activity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III secretory toxin ExoU. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;316:323–331. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirschberg HJHB, Simons JW, Dekker N, Egmond MR. Cloning, expression, purification and characterization of patatin, a novel phospholipase A. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:5037–5044. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rydel TJ, et al. The crystal structure, mutagenesis, and activity studies reveal that patatin is a lipid acyl hydrolase with a Ser-Asp catalytic dyad. Biochemistry. 2003;42:6696–6708. doi: 10.1021/bi027156r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang A, Yang HC, Friedman P, Johnson CA, Dennis EA. A specific human lysophospholipase: cDNA cloning, tissue distribution and kinetic characterization. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1437:157–169. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lio YC, Reynolds LJ, Balsinde J, Dennis EA. Irreversible inhibition of Ca(2+)-independent phospholipase A2 by methylarachidonylfluorophosphate. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1302:55–60. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(96)00002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dole VP, Meinertz H. Microdetermination of long-chain fatty acids in plasma and tissues. J Biol Chem. 1960;235:2595–2599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schaloske RH, Dennis EA. The phospholipase A2 superfamily and its group numbering system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:1246–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martín C, Gómez-Bilbao G, Ostolaza H. Bordetella adenylate cyclase toxin promotes calcium entry into both CD11b+ and CD11b- cells through cAMP-dependent L-type-like calcium channels. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:357–364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.003491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]