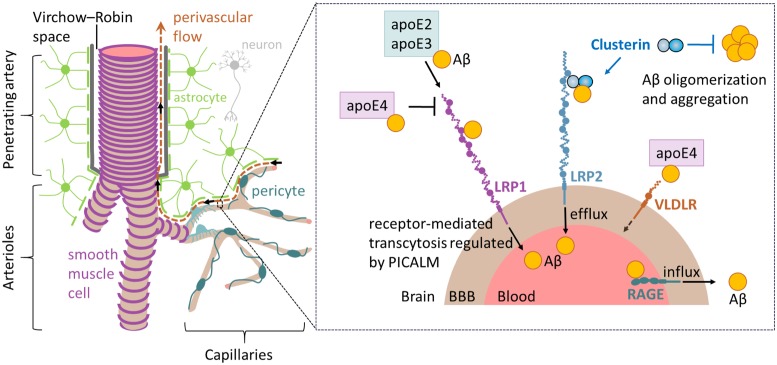

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia, characterized by neurovascular dysfunction, elevated brain parenchymal and vascular amyloid-β (Aβ) levels, tau pathology, and neuronal loss (1, 2). Faulty transvascular clearance of brain Aβ across the blood–brain barrier (BBB) plays an important role in Aβ accumulation in the brain, both in human AD and animal models (1–4). Normally, transvascular brain-to-blood transport across the BBB clears most of Aβ from brain (∼85%), whereas the interstitial fluid (ISF) bulk flow along perivascular spaces removes the remaining smaller fraction of ∼15% of Aβ (5). The two major apolipoproteins in brain, apolipoprotein E (APOE) and apolipoprotein J (APOJ), also known as clusterin (CLU), interact with Aβ and regulate its clearance from brain (1, 2) (Fig. 1). Specifically, Aβ is cleared across the BBB as a free peptide and/or bound to apolipoproteins E2 and E3, but not E4, via endothelial low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1), whereas CLU binds Aβ and mediates its clearance across the BBB via low-density lipoprotein-related protein 2 (LRP2; also known as megalin and gp330) (2, 4). Peripheral Aβ reenters the brain by the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) (6). In PNAS, Wojtas et al. (7) explore the effect of endogenous murine Clu deficiency on Aβ pathology.

Fig. 1.

The neurovascular unit includes neurons, astrocytes, mural cells, and endothelial cells. The type of mural cell varies along the vascular tree, with smooth muscle cells circumventing arteries and arterioles, and pericytes coursing along capillaries. Astrocytic endfeet form the outer glia limitans membrane of the Virchow–Robin spaces along the penetrating arteries. Aβ is predominantly cleared from brain by transvascular clearance across the BBB at the capillary level (see boxed area). Aβ binds LRP1 at the abluminal side of endothelium either as a free peptide or bound to apoE2 and apoE3, and is cleared by receptor-mediated transcytosis that is regulated by phosphatidylinositol binding clathrin assembly protein (PICALM). CLU facilitates Aβ clearance across the BBB via LRP2 and also inhibits Aβ oligomerization and aggregation. Aβ bound to apoE4 is very slowly cleared via VLDLR. Aβ reentry into brain occurs via RAGE. Although most Aβ is cleared from the brain across the BBB, a smaller fraction (∼15%) is cleared by perivascular interstitial fluid (ISF) flow. Transport of Aβ via ISF flow is driven from one hand by the pressure gradient generated by arterial pulsation waves, and from the other by its concentration gradient, which both transport Aβ that has not been cleared across the BBB in direction opposite to arterial blood flow out of the brain for drainage into the cervical lymph nodes.

The CLU gene on chromosome 8p21.1 encodes a 70-kDa multifunctional CLU glycoprotein that is involved in clearance of misfolded proteins, regulation of apoptosis, inflammation, and cancer (8). Brain CLU secreted by glia binds to Aβ and plays a protective role by preventing Aβ aggregation (9–11). CLU forms a stable complex with Aβ (12–14) and promotes its clearance from brain across the BBB via LRP2 (14) (Fig. 1).

Wojtas et al. (7) used APP/PS1 mice, which carry both the amyloid precursor protein (APP) Swedish and the presenilin-1 ΔE9 mutations on a Clu+/+ and Clu−/− background. Compared with 12-mo-old APP/PS1;Clu+/+ littermates, APP/PS1;Clu−/− mice showed a decrease in thioflavin-S–positive Aβ plaques in brain cortex and hippocampus (7). Contrary to this, APP/PS1;Clu−/− mice had a significant increase in thioflavin-S–positive Aβ deposits in leptomeningeal vessels and penetrating arterioles, indicative of cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) (7). Additionally, Wojtas et al. (7) find that APP/PS1;Clu−/− mice have increased Aβ40:42 ratio, which may promote the formation of CAA. This is further supported by the finding that t1/2 (half-time) of Aβ40 clearance from ISF as determined by in vivo microdialysis technique was significantly longer in 10-wk-old mice lacking Clu, suggesting that CLU is important for clearance of soluble Aβ from brain (7) in agreement with previous studies (14). The lack of Clu did not affect brain APP levels, APP processing, Aβ-degrading enzymes, or expression of other AD-risk genes such as Picalm and Cd33 (7). The authors conclude that Clu deficiency shifts brain Aβ clearance toward the perivascular drainage pathway, thereby increasing CAA (7). Because CLU plays an important role in transvascular clearance of Aβ, its absence reduces clearance across the BBB and likely increases the levels of Aβ flowing along and accumulating in the perivascular drainage spaces.

Previous studies investigated the impact of the loss of Clu on Aβ accumulation in PDAPP mice homozygous for the APPV717F transgene driven by the platelet-derived growth factor promoter (15, 16). Similar to Wojtas et al., DeMattos et al. (15, 16) found a reduced number of thioflavin-S–positive plaques in 12-mo-old PDAPP;Clu−/− mice compared with PDAPP;Clu+/+ littermate controls. However, in contrast to Wojtas et al., they found no change in the level of total Aβ in cortex or hippocampus, nor did they identify the presence of CAA (15, 16). Contradictory to Wojtas et al. (7), DeMattos et al. (16) found that the lack of CLU in PDAPP mice may increase levels of soluble Aβ in the brain. This raises the question as to whether or not the altered levels of total Aβ and CAA observed by Wojtas et al. could be a phenomenon specific to the APP/PS1 mouse model. This seems likely, as APP/PS1 mice develop CAA at 6 mo of age (17), and PDAPP mice develop CAA at 24 mo of age (18).

CLU is one of the most associated late-onset AD risk genes (19, 20). The major rs11136000C SNP in the intron region of CLU is associated with reduced CLU expression and increased risk of AD (21), and the minor protective rs11136000T allele is associated with increased CLU expression in brain tissue and reduces the risk of AD (19–23). A recent study investigated the relationship of CLU SNPs with Aβ loads, as measured by PET imaging with florbetapir, and reported that individuals that carried CC allele of rs11136000 had more amyloid deposits than TC allele carriers, and TT allele individuals had the least amyloid deposits (23). Altogether, this evidence supports that increased CLU in brain may be protective in AD by preventing aggregation and increasing clearance of Aβ. Development of and studies in CRISPR mice expressing human CLU SNPs in the presence of increased amyloid pathology are critical to better understand the impact of human polymorphisms in AD pathogenesis. Additionally, investigating the impact of increasing brain CLU expression in transgenic models of amyloidosis is timely and important. Based on the work of Wojtas et al., it would be interesting to determine whether therapies directed at increasing brain CLU levels can reduce CAA and behavioral deficits.

Acknowledgments

Our research is supported by National Institute on Aging (NIA) and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) Grants R01AG023084, R01NS034467, R01AG039452, R01NS090904, P01AG052350, R01NS100459, and P50AG005142. Our work is also supported by Fondation Leducq Transatlantic Network of Excellence for the Study of Perivascular Spaces in Small Vessel Disease (Reference No. 16 CVD 05) and Alzheimer’s Association Grant 509279.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page E6962.

References

- 1.Zlokovic BV. Neurovascular pathways to neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:723–738. doi: 10.1038/nrn3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao Z, Nelson AR, Betsholtz C, Zlokovic BV. Establishment and dysfunction of the blood-brain barrier. Cell. 2015;163:1064–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mawuenyega KG, et al. Decreased clearance of CNS beta-amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 2010;330:1774. doi: 10.1126/science.1197623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao Z, et al. Central role for PICALM in amyloid-β blood-brain barrier transcytosis and clearance. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:978–987. doi: 10.1038/nn.4025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shibata M, et al. Clearance of Alzheimer’s amyloid-ss(1-40) peptide from brain by LDL receptor-related protein-1 at the blood-brain barrier. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1489–1499. doi: 10.1172/JCI10498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deane R, et al. RAGE mediates amyloid-beta peptide transport across the blood-brain barrier and accumulation in brain. Nat Med. 2003;9:907–913. doi: 10.1038/nm890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wojtas AM, et al. Loss of clusterin shifts amyloid deposition to the cerebrovasculature via disruption of perivascular drainage pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E6962–E6971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1701137114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wyatt AR, et al. Clusterin facilitates in vivo clearance of extracellular misfolded proteins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:3919–3931. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0684-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammad SM, Ranganathan S, Loukinova E, Twal WO, Argraves WS. Interaction of apolipoprotein J-amyloid beta-peptide complex with low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-2/megalin. A mechanism to prevent pathological accumulation of amyloid beta-peptide. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18644–18649. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Narayan P, et al. The extracellular chaperone clusterin sequesters oligomeric forms of the amyloid-β(1–40) peptide. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;19:79–83. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beeg M, et al. Clusterin binds to Aβ1-42 oligomers with high affinity and interferes with peptide aggregation by inhibiting primary and secondary nucleation. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:6958–6966. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.689539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zlokovic BV, et al. Brain uptake of circulating apolipoproteins J and E complexed to Alzheimer’s amyloid beta. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;205:1431–1437. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zlokovic BV, et al. Glycoprotein 330/megalin: Probable role in receptor-mediated transport of apolipoprotein J alone and in a complex with Alzheimer disease amyloid beta at the blood-brain and blood-cerebrospinal fluid barriers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4229–4234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bell RD, et al. Transport pathways for clearance of human Alzheimer’s amyloid beta-peptide and apolipoproteins E and J in the mouse central nervous system. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:909–918. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeMattos RB, et al. Clusterin promotes amyloid plaque formation and is critical for neuritic toxicity in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:10843–10848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162228299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeMattos RB, et al. ApoE and clusterin cooperatively suppress Abeta levels and deposition: Evidence that ApoE regulates extracellular Abeta metabolism in vivo. Neuron. 2004;41:193–202. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00850-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia-Alloza M, et al. Characterization of amyloid deposition in the APPswe/PS1dE9 mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;24:516–524. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fryer JD, et al. Apolipoprotein E markedly facilitates age-dependent cerebral amyloid angiopathy and spontaneous hemorrhage in amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7889–7896. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-21-07889.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harold D, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and PICALM associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1088–1093. doi: 10.1038/ng.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lambert J-C, et al. European Alzheimer’s Disease Initiative Investigators Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and CR1 associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1094–1099. doi: 10.1038/ng.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roussotte FF, Gutman BA, Madsen SK, Colby JB, Thompson PM. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Combined effects of Alzheimer risk variants in the CLU and ApoE genes on ventricular expansion patterns in the elderly. J Neurosci. 2014;34:6537–6545. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5236-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ling I-F, Bhongsatiern J, Simpson JF, Fardo DW, Estus S. Genetics of clusterin isoform expression and Alzheimer’s disease risk. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan L, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Effect of CLU genetic variants on cerebrospinal fluid and neuroimaging markers in healthy, mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease cohorts. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26027. doi: 10.1038/srep26027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]