Abstract

Of the anticipated 50,000 individuals expected to be diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 2016, the majority will have metastatic disease. Given the noncurative nature of advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma, treatment is aimed at inducing disease regression, controlling symptom, and extending life. The last 5 years have been marked by advances in the treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer, specifically the approval by the US Food and Drug Administration of 2 combination chemotherapy regimens and the widespread use of a third, which have reproducibly been shown to improve survival. Ongoing studies are building on these regimens along with targeted and immunotherapeutic agents. This article will review the current treatment standards and emerging targets for metastatic pancreatic cancer.

Keywords: chemotherapy, metastatic, pancreatic cancer, targets, treatment standards

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAC) is expected to be diagnosed in approximately 53,070 individuals in 2016 and is the 11th most common cause of cancer. However, this disease represents the third highest cause of cancer-related deaths, with 41,780 deaths estimated to occur in 2016.1 This review will focus on standard therapy for patients with metastatic PAC and emerging directions.

Chemotherapy in the Treatment of Metastatic Disease

Cytotoxic chemotherapy

In 1997, gemcitabine was determined to be the standard treatment for patients with metastatic PAC when it was identified as being superior to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) in a randomized study of 125 patients. Patients receiving gemcitabine were found to have improved overall survival (OS) compared with those receiving 5-FU (median OS of 5.7 months for gemcitabine and 4.4 months for 5-FU [P=.0025]).2 Many gemcitabine-based combinations have been evaluated to date, and the majority of trials have found no meaningful improvements when combining gemcitabine with cytotoxic agents (Table 1).3–20 Two meta-analyses of these trials did note improvements in OS and the response rate (RR) with gemcitabine-based combinations for those patients with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) of 0 to 1.21,22

TABLE 1.

Clinical Trials Comparing Single-Agent Gemcitabine With Combination Chemotherapy

| Study | Therapy | No. | Overall Survival, Months | Response Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E2297 Berlin 20023 | Gemcitabine/5-FU | 322 | 5.4 vs 6.7 | 5.6% vs 6.9% |

| Rocha Lima 20044 | Gemcitabine/irinotecan | 342 | 6.6 vs 6.3 | 4.4% vs 16.1% |

| Louvet 20055 | Gemcitabine/oxaliplatin | 313 | 7.1 vs 9 | 17.3% vs 26.8% |

| Reni 20056 | Cisplatin/epirubicin/5-FU/gemcitabine | 99 | Not reported | 8.5% vs 38.5% |

| Stathopoulos 20067 | Gemcitabine/irinotecan | 145 | 6.5 vs 6.4 | 10% vs 15% |

| Heinemann 20068 | Gemcitabine/cisplatin | 195 | 6 vs 7.5 | 8.2% vs 10.2% |

| Herrmann 20079 | Gemcitabine/capecitabine | 319 | 7.2 vs 8.4 | 7.8% vs 10% |

| E6201 Poplin 200910 | Gemcitabine/oxaliplatin | 832 | 4.9 vs 5.7 | 6% vs 9% |

| Cunningham 200911 | Gemcitabine/capecitabine | 533 | 6.2 vs 7.1 | 12.4% vs 19.1% |

| GIP-1 Colucci 201012 | Gemcitabine/cisplatin | 400 | 8.3 vs 7.2 | 10.1% vs 12.9% |

| PRODIGE Conroy 201113 | FOLFIRINOX | 342 | 6.8 vs 11.1 | 9.4% vs 31.6% |

| Von Hoff 201114 | Gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel | 67 | 12.2a | 48%a |

| MPACT Von Hoff 201315 | Gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel | 861 | 6.7 vs 8.5 | 7% vs 23% |

| PA.3 Moore 200716 | Gemcitabine/erlotinib | 569 | 5.9 vs 6.2 | 8% vs 8.6% |

| S0205 Philip 201017 | Gemcitabine/cetuximab | 745 | 5.9 vs 6.3 | 8% vs 7% |

| Kindler 201118 | Gemcitabine/axitinib | 623 | 8.3 vs 8.5 | 2% vs 5% |

| CALGB 80303 Kindler 201019 | Gemcitabine/bevacizumab | 535 | 5.9 vs 5.8 | 10% vs 13% |

| Rougier 201320 | Gemcitabine/aflibercept | 427 | 7.8 vs 6.5 | Not reported |

Abbreviations: 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; CALGB, Cancer and Leukemia Group B; FOLFIRINOX, 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin; GIP-1, Gruppo Italiano Pancreas 1; PRODIGE, Partenariat de Recherche en Oncologie Digestive.

Single-arm study of gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel only.

In 2011, the PRODIGE 4/ACCORD 11 study (Partenariat de Recherche en Oncologie Digestive/Actions Concertees dans les Cancers Colo-Rectaux et Digestifs) was reported and evaluated a combination of 5-FU, leucovorin (LV), irinotecan, and oxaliplatin (FOLFIRINOX) compared with gemcitabine for patients with newly diagnosed metastatic PAC with a good PS (ECOG PS of 0–1).13 Patients receiving FOLFIRINOX experienced a median OS of 11.1 months with a 31.6% objective RR, compared with a median OS of 6.8 months (hazard ratio [HR], 0.57; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.45–0.73) and an objective RR of 9.4% among patients receiving gemcitabine (P<.001).13 Significant increases in toxicity with FOLFIRINOX compared with gemcitabine were observed with regard to neutropenia (45.7% vs 21%; P<.001), diarrhea (12.7% vs 1.8%; P<.001), and neuropathy (9% vs 0%; P<.001). Although side effects were increased with this combination, fewer patients receiving FOLFIRINOX noted a degradation to their quality of life compared with patients receiving gemcitabine (31% vs 66%; HR, 0.47 [95% CI, 0.3–0.7]).23 Those patients receiving FOLFIRINOX noted that time until deterioration was prolonged compared with that of patients receiving gemcitabine (HR, 4.7; 95% CI, 2.3–9.5).13,23 These findings suggest that improvement in symptoms outweighed the increased toxicities observed with FOLFIRINOX in patients with good PS.

Also in 2011, a phase 1/2 study of gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel in 67 patients with an excellent PS demonstrated an RR of 48% with a median OS of 12.2 months.14 Due to these promising findings, the phase 3 Metastatic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma Clinical Trial (MPACT) ensued, in which 861 patients (with an ECOG PS of 0–2 or a Karnofsky PS of 70%–100%) were randomized to receive gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel or gemcitabine alone.15 This study reported an OS of 8.5 months and an RR of 23% for patients receiving gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel compared with an OS of 6.7 months (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.62–0.83) and an RR of 7% for patients receiving gemcitabine (P<.0001).15 It is interesting to note that the MPACT study included patients with an ECOG PS of 0 to 2, whereas the PRODIGE/ACCORD 11 study included only those patients with an ECOG PS of 0 to 1. Based on these data, the combination of gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel is recommended as a first-line treatment of patients with metastatic PAC and either FOLFIRINOX or the combination of gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel is an appropriate choice for the treatment of patients with untreated metastatic PAC.

Nanoliposomal irinotecan

Irinotecan has known activity in PAC as evidenced by its role in FOLFIRINOX and in multiple single-agent and combination studies.7,13,24–29 Nanoliposomal irinotecan includes the free base of irinotecan within a liposome barrier, which impairs irinotecan metabolism and allows for increased plasma and, potentially, intratumoral exposure of irinotecan and its active metabolite SN-38. In a single-arm phase 2 study in which patients previously treated with gemcitabine received nanoliposomal irinotecan, OS was measured at 5.2 months.30 The phase 3 NAnoliPOsomal Irinotecan-1 (NAPOLI-1) study compared nanoliposomal irinotecan and 5-FU/LV among patients previously treated with gemcitabine.31 A total of 417 patients were randomized to treatment with nanoliposomal irinotecan plus 5-FU/LV, nanoliposomal irinotecan alone, or 5-FU/LV alone, with a median OS of 6.1 months, 4.9 months, and 4.2 months, respectively, reported. The combination of nanoliposomal irinotecan and 5-FU/LV compared with 5-FU/LV alone resulted in improvements in the median OS (6.1 months vs 4.2 months; HR, 0.67 [95% CI, 0.49–0.92]). The OS for patients receiving single-agent nanoliposomal irinotecan compared with 5-FU/LV alone was found to be similar (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.77–1.28).31 As a result of these findings, the combination of 5-FU/LV and nanoliposomal irinotecan was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for patients previously treated with gemcitabine-based therapy.

Targeted therapies in patients with metastatic PAC

Although targeted therapies have altered outcomes in several malignancies, their use has met with limited success in patients with PAC. One example is targeting epidermal growth factor receptor despite compelling preclinical rationale.16,17,32,33 In a randomized phase 3 study of gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine and erlotinib, the median OS was found to be significantly improved from 5.9 months to 6.2 months (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.69–0.99).16 Although the combination of gemcitabine and erlotinib was approved as a treatment option in patients with metastatic PAC, the modest signal, toxicity, and more recent cytotoxic developments have resulted in low uptake of this regimen. Other studies evaluating gemcitabine in combination with targeted therapies such as the epidermal growth factor receptor-directed antibody cetuximab and antivascular agents have demonstrated no significant improvements (Table 1).1–20

Treatment decision making in patients with metastatic PAC

In practice, the choice of which chemotherapeutic agents to use is determined by a patient’s PS along with potential toxicities and patient preference. For fit patients, FOLFIRINOX, gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel, or consideration of a clinical trial is recommended. For those patients with a lower PS (ECOG PS≥2), single-agent gemcitabine, gemcitabine-based combinations along with supportive care, or supportive care alone is recommended.

To improve the tolerability of FOLFIRINOX, modifications to the regimen have been undertaken. Several single-institution, retrospective studies have reported elimination of the 5-FU bolus, using dose-reduced irinotecan, or using routine growth factor support.34,35 Similar OS and improved toxicity profiles have been reported in studies of full-dose and dose-adjusted FOLFIRINOX, suggesting that dose-adjusted FOLFIRINOX appears to be more tolerable than full-dose FOLFIRINOX with limited detrimental effects on efficacy.

Many questions remain regarding the use of these combinations for patients with untreated metastatic PAC. First, which regimen is superior: FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel? Although these regimens have not been compared in the metastatic setting, insights into their comparative efficacy may come from the ongoing S1505 trial, a Southwest Oncology Cooperative Group study evaluating induction chemotherapy with FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel in patients with resectable PAC (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02562716).

Second, what is the optimal sequencing of these regimens? In a retrospective study evaluating 57 patients receiving gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel after experiencing disease progression while receiving FOLFIRINOX, patients received a median of 4 cycles of gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel with a disease control rate of 58%, thereby suggesting that this combination can add significantly after first-line FOLFIRINOX. Notably, the median OS was 18 months from the time of first treatment with FOLFIRINOX.36

Third, can we identify which patients are more likely to respond to gemcitabine-based or 5-FU-based regimens? Currently, there are no biomarkers with which to determine the likelihood of response. Yu et al have developed pharmacogenomic RNA-based expression arrays associated with sensitivity to cytotoxic treatments, including gemcitabine, nab-paclitaxel, FOLFIRINOX, and others.37 These pharmacogenomic models were tested with circulating tumor cells from patients receiving treatment for metastatic PAC and were found to predict which patients were likely to respond to 5-FU-based therapies compared with gemcitabine-based therapies, thereby holding promise for a noninvasive, prospective method with which to match patients to a particular therapy.37

Fourth, how does the combination of 5-FU/LV and nanoliposomal irinotecan fit into these regimens, and what is the optimal treatment after gemcitabine-based therapy? Data from the NAPOLI-1 trial add to several studies designed to answer this question. In Charite Okologie-003 (CONKO-003), a total of 160 patients previously treated with gemcitabine were randomized to treatment with either 5-FU/LV or 5-FU/LV and oxaliplatin.38 The median OS in the 5-FU/LV and oxaliplatin arm was found to be significantly improved compared with that of patients treated with 5-FU/LV alone, at 5.9 months versus 3.3 months, respectively (HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.48–0.91).38 However, conflicting findings were preliminarily reported in the PANCREOX study, in which 108 patients previously treated with gemcitabine were randomized to treatment with infusional and bolus 5-FU, LV, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) or 5-FU/LV, and the median OS was found to be inferior in patients receiving FOLFOX (6.1 months vs 9.9 months; P=.02).39 Within the context of these differing results, the combination of 5-FU/LV and nanoliposomal irinotecan is an emerging standard after gemcitabine-based therapy.

Although many questions remain regarding the optimal sequencing of therapies in patients with advanced PAC, the advances in the last 5 years have unequivocally improved outcomes. Although the OS in patients with this disease is typically measured as <1 year, several retrospective and limited prospective studies cited above have noted an OS of ≤18 months in patients with good PS in this era of modern cytotoxic combination therapy.36,40–42

Promising New Targets and Treatment Strategies in Patients With Metastatic PAC

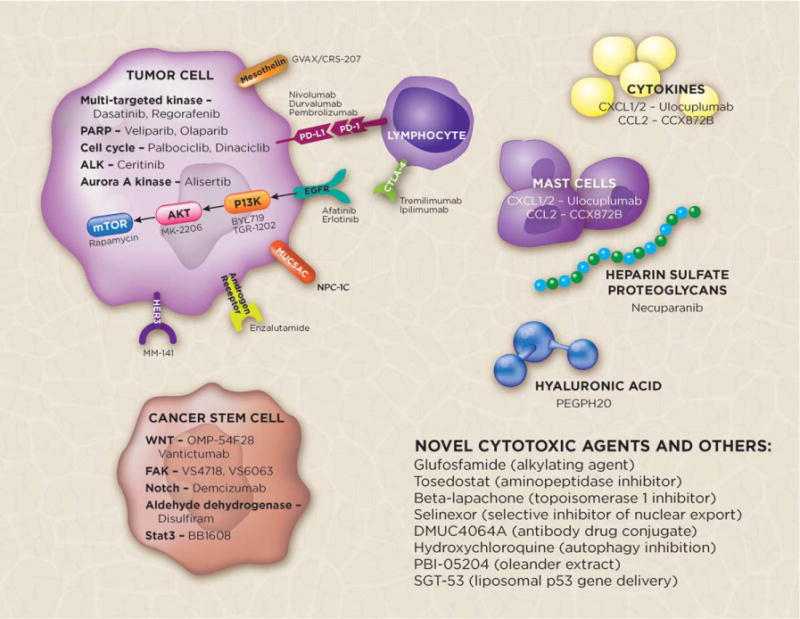

Beyond cytotoxics, a major unmet need exists for new therapies. Historically, PAC has been characterized as a poorly immunogenic tumor harboring no clear actionable molecular alterations and hallmarked by a dense and inert stroma. Each of these features of PAC is being explored and, in some instances, debunked entirely. Preclinical work has demonstrated that there is a dynamic and inhibitory role of PACs and their associated stroma that may allow for evasion of the immune system. Exploiting this complex interplay among the tumor, immune system, and stroma is a focus of ongoing trials (Table 2) (Fig. 1).

TABLE 2.

Selected Ongoing Clinical Trials for Patients With Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer

| Categories | ClinicalTrials.gov Trial No. | Phase | Drugs | Mechanism of Action | Key Endpoint(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stromal targeting | NCT01621243 | 1, 2 | Phase 1: GN and necuparanib Phase 2: GN ± necuparanib |

Necuparanib (M402): heparin sulfate mimetic | Phase 1: DLTs Phase 2: OS |

| NCT01839487 | 2 | GN ± PEGPH20 | PEGPH20: pegylated recombinant hyaluronidase | PFS | |

| NCT01959139 | 1, 2 | Phase 1: FOLFIRINOX and PEGPH20 Phase 2: FOLFIRINOX ± PEGPH20 |

PEGPH20: pegylated recombinant hyaluronidase | Phase 1: DLT Phase 2: OS |

|

| NCT02715804 | 3 | GN ± PEGPH20 | PEGPH20: pegylated recombinant hyaluronidase | PFS, OS | |

| NCT02345408 | 1 | FOLFIRINOX, CCX872-B | CCX872-B: CCR2 inhibitor | PFS | |

| NCT02436668 | 2, 3 | GN ± ibrutinib | Ibrutinib: Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor | PFS | |

| NCT02562898 | 1, 2 | GN and ibrutinib | Ibrutinib: Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor | DLT | |

| Immunotherapy | NCT01876511 | 2 | MK-3475 | MK-3475 (pembrolizumab): anti-PD-1 antibody | PFS |

| NCT01896869 | 2 | Arm A: ipilimumab and GVAX Arm B: FOLFIRINOX |

GVAX: vaccine against mesothelin-expressing cancer cells Ipilimumab: anti-CTLA-4 antibody | OS | |

| NCT02243371 | 2 | CY, GVAX, and CRS-207 ± nivolumab | GVAX: vaccine against mesothelin-expressing cancer cells CRS-207: modified Listeria that promotes mesothelin expression Nivolumab: anti-PD-1 antibody | OS | |

| NCT02472977 | 1, 2 | Phase 1: ulocuplumab and nivolumab Phase 2: Arm A: ulocuplumab and nivolumab Arm B: investigator’s choice | Ulocuplumab: CXCR4 antibody | MTD, ORR, OS | |

| NCT02558894 | 2 | MEDI4736 ± tremelimumab | MEDI4736: anti-PD-L1 antibody Tremelimumab: anti-CTLA-4 antibody | ORR | |

| NCT02620423 | 1 | Pembrolizumab, pelareorep, and chemotherapy (gemcitabine, irinotecan, or 5-FU/LV) | Pelareorep: oncolytic virus targeting RAS-mutant cells | DLT | |

| NCT02548169 | 1 | Dendritic cell vaccine and chemotherapy (FOLFIRINOX or GN) | DLT | ||

| NCT02268825 | 1, 2 | MK-3475, FOLFOX | MK-3475 (pembrolizumab): anti-PD-1 antibody | DLT | |

| NCT02672917 | 1 | MVT-5873 ± chemotherapy | MVT-5873: monoclonal antibody targeting CA 19-9 | MTD | |

| DNA damage response | NCT01489865 | 1, 2 | 5-FU/LV, oxaliplatin, ABT-888 | ABT-888 (veliparib): PARPi | DLT |

| NCT01585805 | 2 | Part 1: veliparib, gemcitabine, and cisplatin Arm B: gemcitabine and cisplatin Part 2: veliparib | Veliparib: PARPi | Part 1: DLT Part 2: ORR |

|

| NCT02184195 | 3 | Arm A: olaparib Arm B: placebo | Olaparib: PARPi | PFS | |

| Novel cytotoxic agents and combinations | NCT02581501 | 1 | GN and capecitabine | DLT | |

| NCT02324543 | 1, 2 | Gemcitabine, docetaxel, capecitabine, cisplatin, and irinotecan | DLT, OS | ||

| NCT02333188 | 1, 2 | 5-FU/LV, irinotecan, and nab-paclitaxel | DLT | ||

| NCT01893801 | 1, 2 | Nab-paclitaxel, cisplatin, and gemcitabine | ORR | ||

| NCT01954992 | 3 | Arm A: glufosfamide Arm B: 5-FU | Glufosfamide: novel alkylating agent | OS | |

| NCT02620800 | 1, 2 | 5-FU/LV, nab-paclitaxel, bevacizumab, and oxaliplatin | Phase 1: DLT Phase 2: 1-y OS |

||

| NCT02551991 | 2 | Arm A: nanoliposomal irinotecan, 5-FU/LV, and oxaliplatin Arm B: nanoliposomal irinotecan, 5-FU/LV Arm C: nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine | PFS | ||

| NCT02080221 | 2 | FOLFOX and nab-paclitaxel | OS | ||

| Cancer stem cell targeting | NCT02651727 | 1 | GN and VS-4718 | VS-4718: focal adhesion kinase inhibitor | DLT |

| NCT02289898 | 2 | GN ± demcizumab | Demcizumab: delta-like ligand 4 antibody | PFS | |

| NCT02671890 | 1 | Gemcitabine ± disulfiram | Disulfiram: acetaldehyde dehydrogenase inhibitor | DLT | |

| NCT02546531 | 1 | Gemcitabine, pembrolizumab, and defactinib | Defactinib: focal adhesion kinase inhibitor | DLT | |

| NCT02231723 | 1 | Arm A: GN and BBI608 Arm B: FOLFIRINOX and BBI608 Arm C: FOLFIRI and BBI608 Arm D: 5-FU/LV, BBI608, and MM-398 | BBI608: STAT, stem cell inhibitor | DLT | |

| NCT02050178 | 1 | GN and OMP54F28 | OMP54F28: WNT pathway antagonist | DLT | |

| NCT02005315 | 1 | GN and vantictumab | Vantictumab: WNT signaling inhibitor | DLT | |

| NCT02077881 | 1, 2 | GN and indoximod | Indoximod: IDO pathway inhibitor | Phase 1: DLT Phase 2: OS |

|

| Targeted therapies and others | NCT02352831 | 1, 2 | Tosedostat | Tosedostat: aminopeptidase inhibitor | Phase 1: DLT Phase 2: PFS |

| NCT02574663 | 1 | Arm A: TGR-1202 Arm B: GN and TGR-1202 Arm C: FOLFOX and TGR-1202 Arm D: FOLFOX, bevacizumab, and TGR-1202 | TGR-1202: PI3K delta inhibitor | DLT | |

| NCT02501902 | 1 | Nab-paclitaxel and palbociclib | Palbociclib: CDK4/6 inhibitor | DLT | |

| NCT02514031 | 1 | GN and beta-lapachone | Beta-lapachone: novel 1,2-naphthoquinone | DLT | |

| NCT02468557 | 1 | Arm A: Idelalisib Arm B: Nab-paclitaxel and idelalisib Arm C: FOLFOX and idelalisib | Idelalisib : PI3K delta inhibitor | DLT | |

| NCT02451553 | Afatinib and capecitabine | Afatinib: EGFR/HER2 inhibitor | DLT | ||

| NCT02178436 | 1, 2 | GN and KPT-330 | KPT-330: selective inhibitor of nuclear export inhibitor | Phase 1: DLT Phase 2: OS |

|

| NCT02227940 | 1 | Arm A: Ceritinib and gemcitabine Arm B: Ceritinib and GN Arm C: Ceritinib, gemcitabine, and cisplatin |

Ceritinib: ALK inhibitor | DLT | |

| NCT02155088 | 1 | GN and BYL719 | BYL719: PI3K alpha inhibitor | DLT | |

| NCT02146313 | 1 | DMUC4064A | Antibody-drug conjugate to MUC16 | DLT | |

| NCT02154737 | 1 | Gemcitabine and erlotinib | DLT | ||

| NCT02138383 | 1 | GN and enzalutamide | Enzalutamide: nonsteroidal antiandrogen | MTD | |

| NCT01783171 | 1 | Dinaciclib and MK-2206 | Dinaciclib: CDK4 inhibitor MK-2206: AKT inhibitor | DLT | |

| NCT01924260 | 1 | Gemcitabine and alisertib | Alisertib: aurora kinase A inhibitor | DLT | |

| NCT01506973 | 1, 2 | Hydroxychloroquine, gemcitabine, and nab-paclitaxel | Hydroxychloroquine: antimalarial drug, inhibits autophagy | OS | |

| NCT02048384 | 1, 2 | Metformin ± rapamycin | Rapamycin: mTOR inhibitor | Safety and feasibility | |

| NCT02650804 | 2 | BPM31510 and gemcitabine | BPM31510: small molecule targeting cancer metabolism | ORR | |

| NCT02570711 | 2 | GN ± ACP-196 | ACP-196: Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor | ORR | |

| NCT02329717 | 2 | PBI-05204 | PBI-05204 : Oleander derivative, inhibitor of AKT, FGF-2, NF-Kb, and p70S6K | OS | |

| NCT02340117 | 2 | SGT-53 and GN | SGT-53: nanoliposomal delivery method targeting p53 | PFS | |

| NCT02399137 | 2 | GN ± MM-141 | MM-141: IGF-1R and ErbB3 bispecific antibody | PFS | |

| NCT02080260 | 2 | Regorafenib | Regorafenib: oral multityrosine kinase inhibitor | PFS | |

| NCT01905150 | 2 | Gemcitabine, 5-FU/LV, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin ± vitamin C | 1-y OS | ||

| NCT01834235 | 1, 2 | GN ± NPC-1C | NPC-1C: monoclonal antibody targeting colon and pancreatic cancer cells | OS | |

| NCT01666730 | 2 | FOLFOX and metformin | OS | ||

| NCT01652976 | 2 | FOLFOX and dasatinib | Dasatinib: oral multi-tyrosine kinase inhibitor | PFS | |

| NCT02244489 | 1 | Capecitabine, oxaliplatin, and momelotinib | Momelotinib: JAK1/2 inhibitor | DLT | |

| NCT02101021 | 3 | GN ± momelotinib | Momelotinib: JAK1/2 inhibitor | OS |

Abbreviations: 5-FU/LV, 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin; ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; CCR2, C-C chemokine receptor type 2; CCX872-B, C-C chemokine receptor type 2 (CCR2) antagonist; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4; CXCR4, C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4; DLT, dose-limiting toxicity; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; FGF-2, fibroblast growth factor 2; FOLFIRINOX, 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin; FOLFOX, 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin; GN, gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; IDO, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; IGF-1R, insulin-like growth factor receptor 1; JAK1/2, Janus kinase 1/2; MTD, maximum tolerated dose; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; NF-kB, nuclear factor kB; ORR, objective response rate; OS, overall survival; PARPi, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors; PD-1, programmed cell death protein 1; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1 PFS, progression-free survival; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase.

Figure 1.

Selected investigational agents and targets in metastatic pancreatic cancer. ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; CCL2, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4; CXCL1/2, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1/2 (CXCL1/2); EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; HER3, human epidermal growth factor receptor 3; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; MUC5AC, mucin 5AC, oligomeric mucus/gel-forming; PARP, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase; PD-1, programmed cell death protein 1; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase.

Stromal targeting agents

The dense stroma associated with PAC provides a physical barrier to chemotherapy.43,44 Preclinical work from Hingorani et al have confirmed a changing interplay between the tumor and its stroma such that disease progression is associated with a robust desmoplastic reaction, thereby limiting delivery of therapeutic agents.45–47 The in vivo administration of PEGPH20, a pegylated recombinant hyaluronidase, alone and in combination with gemcitabine to mice models with PAC demonstrated degradation and depletion of hyaluronic acid, a component of the tumor stroma, with an improvement in RR and prolonged responses.47 Ongoing trials are evaluating the combination of PEGPH20 with cytotoxic chemotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed PAC (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers NCT01839487, NCT01959139, and NCT02715804) (Table 2).

Heparin sulfate proteoglycans within the tumor stroma stimulate tumor growth, and necuparanib (M402) is a heparin sulfate mimetic that blocks these stimulatory activities. O’Reilly et al presented a phase 1 trial evaluating the combination of necuparanib, gemcitabine, and nab-paclitaxel, and a disease control rate of 88% was noted among the 16 patients who completed the first cycle of treatment.48 This phase 2 study is currently ongoing (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01621243) (Table 2).

Another dynamic component of the tumor stroma is mast cells, which are required for tumor progression and angiogenesis.49 Preclinical models have suggested that ibrutinib, an inhibitor of mast cells, results in antitumor effect, and a trial currently is underway to evaluate its safety and efficacy in combination with chemotherapy (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers NCT02436668 and NCT02562898) (Table 2).50

Application and investigation of immunotherapy treatments and strategies in PAC

Some have argued that PAC is a poorly immunogenic tumor given that it lacks tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and high numbers of somatic mutations, features that have been linked to diseases with responses to immune checkpoint inhibition with anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) or anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) antibodies.43,51–58 In a trial of 27 unselected patients with PAC, single-agent checkpoint inhibitors demonstrated a modest signal of activity.59 No patients experienced an objective initial response, although one patient did experience a delayed response.59 These findings are consistent with molecular analysis of PACs, which has found that a subset of PACs may be more immunogenic than others, suggesting that immunotherapy may be helpful in a selected patient population.60 In addition, preliminary reports of single-agent check-point inhibition in patients with mismatch repair (MMR)-deficient pancreatic cancer are promising, with stable disease noted among 3 of 4 patients with MMR-deficient pancreatic cancer and 1 of 4 patients experiencing a partial response, thereby expanding on responses observed with checkpoint inhibition for patients with MMR-deficient colorectal cancers (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01876511).51,61 Given the synergistic effect of multiple agents targeting checkpoint blockade with anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 antibodies in melanoma, combination strategies are ongoing in PAC (Clinical-Trials.gov identifier NCT02558894) (Table 2).54

The tumor stroma also contributes to immune system evasion. Fibroblasts within the stroma produce chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1/2 (CXCL1/2), a cytokine that inhibits T-cell recruitment. CXCL1/2 inhibition was reported to work synergistically with checkpoint blockade to cause tumor regression in preclinical models.62 This combination strategy currently is being evaluated in a trial of ulocuplumab (antibody to C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4 [CXCR4], a receptor for CXCL1/2) with nivolumab (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02472977) (Table 2).

The chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2)/C-C chemokine receptor type 2 (CCR2) axis likely plays an important role in disease progression as well. CCL2 and its receptor CCR2 mobilize inflammatory monocytes to the tumor-stroma microenvironment to promote metastatic disease. Using in vivo PAC models, CCR2 inhibition was found to result in decreased tumor growth.63 A phase 1 study found that the CCR2 inhibitor CCX872-B was tolerable as a single agent, and a phase 1B study currently is ongoing with CCX872-B combined with FOLFIRINOX (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02345408) (Table 2).64

Immunotherapy using the GVAX and CRS-207 vaccines also has been studied in patients with PAC. GVAX induces T-cell response against PAC-associated antigens, including mesothelin. CRS-207 secretes mesothelin into antigen-presenting cells. The combination of CRS-207 and GVAX is believed to stimulate an autoimmune response to mesothelin-expressing PAC cells. Although preliminary reports evaluating the combination of these agents suggested a tolerable side effect profile and promising efficacy, an interim analysis from the phase 2b ECLIPSE (Safety and Efficacy of Combination Listeria/GVAX Pancreas Vaccine in the Pancreatic Cancer Setting) trial demonstrated no significant difference in OS for patients receiving CRS-207 with and without GVAX (3.8 months vs 5.4 months).65,66 However, treatment with CRS-207 alone did demonstrate outcomes similar to those of patients receiving chemotherapy (4.6 months), thereby suggesting some benefit to CRS-207.66

The combination of checkpoint inhibitors and vaccines provides another therapeutic avenue. The STELLAR trial (Safety and Therapeutic Efficacy of Live-attenuated Listeria/GVAX with Anti-PDl Regimen) currently is evaluating the activity of this regimen (Clinical-Trials.gov identifier NCT02243371) (Table 2). In this randomized phase 2 trial, patients receive CRS-207/GVAX with and without nivolumab with OS as the primary endpoint. Another recently completed but not yet reported randomized phase 2 trial study evaluated the role of ipilimumab with and without the PAC vaccine GVAX in the second-line setting (Table 2). Further trials investigating novel combinations of immunotherapy, chemotherapy, and vaccines currently are ongoing, a selection of which are described in Table 2.

Deficiencies in homologous recombination and DNA repair as a biomarker for novel treatments in patients with PAC

Up to 10% to 15% of patients with PAC harbor an increased susceptibility to cancer due to an inherited cancer predisposition syndrome. The most common germline alterations are observed in the genes BRCA1, BRCA2, and PALB2 (Partner And Localizer of BRCA2). As described by Salo-Mullen et al, approximately 15.1% (95% CI, 9.5%–20.7%) of patients who underwent genetic testing in a clinical genetics service at a tertiary care cancer hospital were found to have germline pathogenic mutations. Alterations were observed most often in the genes listed above and genes in the MMR pathway suggestive of Lynch syndrome. BRCA1/2 and PALB2 play critical roles in the homologous recombination and repair of DNA double-stranded breaks, and these impaired DNA repair pathways represent another therapeutic target with platinum agents and inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP).

Platinum agents cause interstrand crosslinks that ultimately lead to DNA double-strand breaks. In the setting of deficient homologous repair such as in BRCA-deficient tumors, platinum agents can exploit this weakness and have been shown to be effective.68,69 Lowery et al reported that 5 of 6 patients with PAC and germline BRCA1/2 alterations achieved a partial response to platinum-containing regimens, and another retrospective review of 71 patients with BRCA-associated PAC noted an improvement in OS with platinum-containing regimens compared with those who did not receive platinum therapies (22 months vs 9 months; P=.039).68,69 Likewise, single-strand DNA breaks require repair and modification by PARP. PARP inhibition can further limit the ability to repair these single-strand DNA breaks, resulting in DNA double-strand breaks and cell death within the setting of impaired homologous recombination. In a phase 2 trial of 23 patients with a germline BRCA1/2 alteration and PAC who received the PARP inhibitor olaparib, 22% achieved a complete or partial response and 35% achieved stable disease, a finding that is consistent with those reported in other BRCA-related tumors.70 Given that PARP activity is increased within the setting of DNA damage, PARP inhibitors administered with platinum agents may have a synergistic effect that can be used to therapeutic benefit in patients with PACs with deficient homologous repair mechanisms.

Studies currently are ongoing to evaluate the role of platinum and PARP inhibitors in patients with BRCA-related PAC. Preliminary results from a phase 1B study in which patients with BRCA1/2 or PALB2 germline alterations received cisplatin, gemcitabine, and veliparib noted that 9 of 9 patients achieved disease control, with 5 of 9 patients achieving a partial response and 4 of 9 having stable disease.71 These findings suggest that deficient homologous recombination as identified by germline BRCA1/2 or PALB2 alterations is a biomarker for treatment with PARP inhibitors and platinum therapy. Several phase 2 studies evaluating platinum-based chemotherapy with and without PARP inhibitors currently are ongoing (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers NCT01585805 and NCT01489865) (Table 2). A phase 3 study is ongoing among patients with metastatic PAC and germline BRCA alterations in which they receive maintenance therapy with a PARP inhibitor after disease stability is achieved on first-line platinum-based chemotherapy (ClinicalTrials.gov identifierNCT02184l95) (Table 2).

Several phase 3 trials also recently have been reported that have demonstrated no significant benefits after promising phase 1 and 2 studies, thereby highlighting the need for the proper selection of patients in phase 1 and 2 studies as well as the more efficient use of patient time and resources with randomized phase 2 studies (Table 3).72–75

TABLE 3.

Recently Reported Negative Trials in Patients With Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer

| Study | ClinicalTrials.gov Trial No. | Therapy | No. | Overall Survival, Months | Response Rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALPINE 201672 | NCT01647828 | GN ± OMP-59R5 | 177 | OMP-59R5: notch 2/3 inhibitor | ||

| MAESTRO 201673 | NCT01746979 | Gemcitabine ± evofosfamide | 693 | Evofosfamide | 7.6 vs 8.7 (P=.0589) |

15% vs 19% (P=.18) |

| JANUS 1 and JANUS 2 201674 |

JANUS 1: NCT02117479 JANUS 2: NCT02119663 |

JANUS 1: ruxolitinib plus capecitabine JANUS 2: capecitabine ± ruxolitinib | Ruxolitinib: JAK 1/2 inhibitor | |||

| PANCRIT-1 trial 20165 | NCT01956812 | Gemcitabine ± yttrium-90-labeled clivatuzumab tetraxetan | Yttrium-90-labeled clivatuzumab: monoclonal antibody targeting mucin conjugated with localized radiation |

Abbreviations: GN, gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel; JAK1/2, Janus kinase 1/2.

With respect to molecular understanding of PAC, the vast majority of cases harbor molecular alterations in ≥1 of the genes KRAS, TP53, CDKN2, and SMAD4, genes that have been challenging to target successfully using precision medicine approaches at this time. Bailey et al published a genomic analysis of 456 patients with PAC and identified that the most commonly mutated genes clustered around 10 pathways, including KRAS transforming growth factor-β, WNT, NOTCH, DNA repair, and others, many of which do provide promising therapeutic opportunities (a selection of which are described in Table 2).60 In addition, many clinicians and patients are seeking next-generation sequencing approaches with which to search for targetable alterations in tumors. Given the growing number of “basket studies” with targeted therapies in which patients are selected based on a molecular alteration rather than a cancer’s site of origin, this presents another opportunity for investigational treatment.

Conclusions

The treatment of patients with metastatic PAC has evolved significantly, with several new active cytotoxic regimens (FOLFIRINOX, gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel, and nanoliposomal irinotecan/5-FU), all of which currently are in common use and have collectively improved survival. The interplay of the immune system and stromal targeting as well as enhanced understanding of molecular genomics, the identification of biomarkers and selected treatments for certain patient subgroups (homologous repair deficiency), and the emerging ability to classify subsets of patients with this disease collectively contribute to the optimism that meaningful improvements in patient outcomes for this cancer are on the horizon.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SUPPORT

Funded by the Andrea J. Will Foundation, the Davidson Family, and other philanthropic support.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

Eileen M. O’Reilly has received research funding and consulting fees from Celgene and Bristol-Myers Squibb; research funding from Momenta Pharmaceuticals, Astra-Zeneca, OncoMed Pharmaceuticals, and MabVax Therapeutics; and consulting fees from Sanofi Aventis and Pfizer for work performed outside of the current study.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Anna M. Varghese: Conceptualization, writing-original draft, and writing-review and editing. Maeve A. Lowery: Writing-review and editing. Kenneth H. Yu: Writing-review and editing. Eileen M. O’Reilly: Conceptualization, writing-original draft, and writing-review and editing. Anna M. Varghese and Eileen M. O’Reilly are responsible for the overall content.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burris HA, 3rd, Moore MJ, Andersen J, et al. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2403–2413. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berlin JD, Catalano P, Thomas JP, Kugler JW, Haller DG, Benson AB., 3rd Phase III study of gemcitabine in combination with fluorouracil versus gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic carcinoma: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial E2297. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3270–3275. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rocha Lima CM, Green MR, Rotche R, et al. Irinotecan plus gemcitabine results in no survival advantage compared with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer despite increased tumor response rate. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3776–3783. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Louvet C, Labianca R, Hammel P, et al. GERCOR; GISCAD Gemcitabine in combination with oxaliplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: results of a GERCOR and GISCAD phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3509–3516. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reni M, Cordio S, Milandri C, et al. Gemcitabine versus cisplatin, epirubicin, fluorouracil, and gemcitabine in advanced pancreatic cancer: a randomised controlled multicentre phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:369–376. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70175-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stathopoulos GP, Syrigos K, Aravantinos G, et al. A multicenter phase III trial comparing irinotecan-gemcitabine (IG) with gemcitabine (G) monotherapy as first-line treatment in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:587–592. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heinemann V, Quietzsch D, Gieseler F, et al. Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3946–3952. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herrmann R, Godsky G, Ruhstaller T, et al. Gemcitabine Plus Capecitabine Compared With Gemcitabine Alone in Advanced Pancreatic Cancer: A Randomized, Multicenter, Phase III Trial of the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research and the Central European Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2212–2217. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.0886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poplin E, Feng Y, Berlin J, et al. Phase III, randomized study of gemcitabine and oxaliplatin versus gemcitabine (fixed-dose rate infusion) compared with gemcitabine (30-minute infusion) in patients with pancreatic carcinoma E6201: a trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3778–3785. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.9007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunningham D, Chau I, Stocken DD, et al. Phase III randomized comparison of gemcitabine versus gemcitabine plus capecitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5513–5518. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colucci G, Labianca R, Di Costanzo F, et al. Gruppo Oncologico Italia Meridionale (GOIM); Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio dei Carcinomi dell’Apparato Digerente (GISCAD); Gruppo Oncologico Italiano di Ricerca Clinica (GOIRC) Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin compared with single-agent gemcitabine as first-line treatment of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: the GIP-1 study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1645–1651. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, et al. Groupe Tumeurs Digestives of Unicancer; PRODIGE Intergroup FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817–1825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Von Hoff DD, Ramanathan RK, Borad MJ, et al. Gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel is an active regimen in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase I/II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4548–4554. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.5742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1691–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore MJ, Goldstein D, Hamm J, et al. National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1960–1966. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Philip PA, Benedetti J, Corless CL, et al. Phase III study comparing gemcitabine plus cetuximab versus gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Southwest Oncology Group-directed intergroup trial S0205. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3605–3610. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.7550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kindler HL, Ioka T, Richel DJ, et al. Axitinib plus gemcitabine versus placebo plus gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a double-blind randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:256–262. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kindler HL, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, et al. Gemcitabine plus bevacizumab compared with gemcitabine plus placebo in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: phase III trial of the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 80303) J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3617–3622. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rougier P, Riess H, Manges R, et al. Randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel-group phase III study evaluating aflibercept in patients receiving first-line treatment with gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:2633–2642. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sultana A, Smith CT, Cunningham D, Starling N, Neoptolemos JP, Ghaneh P. Meta-analyses of chemotherapy for locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2607–2615. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heinemann V, Boeck S, Hinke A, Labianca R, Louvet C. Meta-analysis of randomized trials: evaluation of benefit from gemcitabine-based combination chemotherapy applied in advanced pancreatic cancer. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:82. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gourgou-Bourgade S, Bascoul-Mollevi C, Desseigne F, et al. Impact of FOLFIRINOX compared with gemcitabine on quality of life in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer: results from the PRODIGE 4/ACCORD 11 randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:23–29. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.4869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yi SY, Park YS, Kim HS, et al. Irinotecan monotherapy as second-line treatment in advanced pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;63:1141–1145. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0839-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cereda S, Reni M, Rognone A, et al. XELIRI or FOLFIRI as salvage therapy in advanced pancreatic cancer. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:4785–4790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gebbia V, Maiello E, Giuliani F, Borsellino N, Arcara C, Colucci G. Irinotecan plus bolus/infusional 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin in patients with pretreated advanced pancreatic carcinoma: a multicenter experience of the Gruppo Oncologico Italia Meridionale. Am J Clin Oncol. 2010;33:461–464. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181b4e3b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neuzillet C, Hentic O, Rousseau B, et al. FOLFIRI regimen in metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma resistant to gemcitabine and platinum-salts. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4533–4541. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i33.4533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoo C, Hwang JY, Kim JE, et al. A randomised phase II study of modified FOLFIRI.3 vs modified FOLFOX as second-line therapy in patients with gemcitabine-refractory advanced pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1658–1663. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zaniboni A, Aitini E, Barni S, et al. FOLFIRI as second-line chemotherapy for advanced pancreatic cancer: a GISCAD multicenter phase II study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012;69:1641–1645. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-1875-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ko AH, Tempero MA, Shan YS, et al. A multinational phase 2 study of nanoliposomal irinotecan sucrosofate (PEP02, MM-398) for patients with gemcitabine-refractory metastatic pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:920–925. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang-Gillam A, Li CP, Bodoky G, et al. NAPOLI-1 Study Group Nanoliposomal irinotecan with fluorouracil and folinic acid in metastatic pancreatic cancer after previous gemcitabine-based therapy (NAPOLI-1): a global, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;387:545–557. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00986-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fjallskog ML, Lejonklou MH, Oberg KE, Eriksson BK, Janson ET. Expression of molecular targets for tyrosine kinase receptor antagonists in malignant endocrine pancreatic tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:1469–1473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tobita K, Kijima H, Dowaki S, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor expression in human pancreatic cancer: significance for liver metastasis. Int J Mol Med. 2003;11:305–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mahaseth H, Brutcher E, Kauh J, et al. Modified FOLFIRINOX regimen with improved safety and maintained efficacy in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Pancreas. 2013;42:1311–1315. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31829e2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghorani E, Wong HH, Hewitt C, Calder J, Corrie P, Basu B. Safety and efficacy of modified FOLFIRINOX for advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a UK single-centre experience. Oncology. 2015;89:281–287. doi: 10.1159/000439171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Portal A, Pernot S, Arbaud C, et al. Nab paclitaxel plus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma after failure of FOLFIRINOX: results of an AGEO multicenter prospective cohort [abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2015;33 Pages. Abstract 4123. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu KH, Ricigliano M, Hidalgo M, et al. Pharmacogenomic modeling of circulating tumor and invasive cells for prediction of chemotherapy response and resistance in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:5281–5289. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oettle H, Riess H, Stieler JM, et al. Second-line oxaliplatin, folinic acid, and fluorouracil versus folinic acid and fluorouracil alone forgemcitabine-refractory pancreatic cancer: outcomes from the CONKO-003 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2423–2429. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.6995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gill S, Ko Y, Cripps M, et al. PANCREOX: a randomized phase 3 study of 5FU/LV with or without oxaliplatin for second-line advanced pancreatic cancer (APC) in patients (pts) who have received gemcitabine (GEM)-based chemotherapy (CT) [abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2014;32 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.5776. Pages. Abstract 4022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Portal A, Pernot S, Tougeron D, et al. Nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabien for metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma after FOLFIRINOX failure: an AGEO prospective multicentre cohort. Br J Cancer. 2015;113:989–995. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramanathan RK, Lee P, Seng JE, et al. Phase II study of induction therapy with gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel followed by consolidation with mFOLFIRINOX in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(suppl 3) abstr 224. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goldstein D, Chiorean EG, Tabernero J, et al. Outcome of second-line treatment following nab-paclitaxel + gemcitabine or gemcitabine alone for metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Onc. 2016;34(supple 4S) abstr 333. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ko AH. Progress in the treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer and the search for next opportunities. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1779–1786. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.7625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chu GC, Kimmelman AC, Hezel AF, DePinho RA. Stromal biology of pancreatic cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2007;101:887–907. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hingorani SR. Cellular and molecular conspirators in pancreas cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35:1435. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stromnes IM, DelGiorno KE, Greenberg PD, Hingorani SR. Stromal reengineering to treat pancreas cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35:1451–1460. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Provenzano PP, Cuevas C, Chang AE, Goel VK, Von Hoff DD, Hingorani SR. Enzymatic targeting of the stroma ablates physical barriers to treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:418–429. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O’Reilly E, Mahalingam D, Roach J, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and antitumor activity of necuparanib combined with nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer: phase 1 results [abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2015;33 doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0472. Pages. Abstract 4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Soucek L, Lawlor ER, Soto D, Shchors K, Swigart LB, Evan GI. Mast cells are required for angiogenesis and macroscopic expansion of Myc-induced pancreatic islet tumors. Nat Med. 2007;13:1211–1218. doi: 10.1038/nm1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Masso-Valles D, Jauset T, Serrano E, et al. Ibrutinib exerts potent antifibrotic and antitumor activities in mouse models of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2015;75:1675–1681. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2509–2520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Snyder A, Makarov V, Merghoub T, et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2189–2199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clark CE, Beatty GL, Vonderheide RH. Immunosurveillance of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: insights from genetically engineered mouse models of cancer. Cancer Lett. 2009;279:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Postow MA, Chesney J, Pavlick AC, et al. Nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2006–2017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1627–1639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:123–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2455–2465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Royal RE, Levy C, Turner K, et al. Phase 2 trial of single agent ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4) for locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Immunother. 2010;33:828–833. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181eec14c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bailey P, Chang DK, Nones K, et al. Genomic analyses identify molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2016;531:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nature16965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, et al. PD-1 blockade in mismatch repair deficient non-colorectal gastrointestinal cancers [abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl 4S) Pages. Abstract 195. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Feig C, Jones JO, Kraman M, et al. Targeting CXCL12 from FAP-expressing carcinoma-associated fibroblasts synergizes with anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:20212–20217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320318110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sanford DE, Belt BA, Panni RZ, et al. Inflammatory monocyte mobilization decreases patient survival in pancreatic cancer: a role for targeting the CCL2/CCR2 axis. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:3404–3415. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hezel A, Eskens F, Sleijfer S, et al. Abstract B24: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile of the novel, oral and selective CCR2 inhibitor CCX872-B in a Phase 1B pancreatic cancer trial. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14(12 suppl 2):B24. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Le DT, Wang-Gillam A, Picozzi V, et al. Safety and survival with GVAX pancreas prime and Listeria Monocytogenes-expressing mesothelin (CRS-207) boost vaccines for metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1325–1333. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.4244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Aduro Biotech. Aduro Biotech announces phase 2b ECLIPSE trial misses primary endpoint in heavily pretreated metastatic pancreatic cancer. [press release] http://investors.aduro.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=242043&p=irol-newsArticle&ID=2168543. Accessed May 20, 2016.

- 67.Salo-Mullen EE, O’Reilly EM, Kelsen DP, et al. Identification of germline genetic mutations in patients with pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2015;121:4382–4388. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Golan T, Kanji ZS, Epelbaum R, et al. Overall survival and clinical characteristics of pancreatic cancer in BRCA mutation carriers. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:1132–1138. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lowery MA, Kelsen DP, Stadler ZK, et al. An emerging entity: pancreatic adenocarcinoma associated with a known BRCA mutation: clinical descriptors, treatment implications, and future directions. Oncologist. 2011;16:1397–1402. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kaufman B, Shapira-Frommer R, Schmutzler R, et al. Olaparib monotherapy in patients with advanced cancer and a germ-line BRCA1/2 mutation: an open-label phase II study [abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2013;31 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.2728. Pages. Abstract 11024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.O’Reilly E, Lowery M, Segal M, et al. Phase IB trial of cisplatin (C), gemcitabine (G), and veliparib (V) in patients with known or potential BRCA or ALB2-mutated pancreas adenocarcinoma (PC) [abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2014;32 Pages. Abstract 4023. [Google Scholar]

- 72.OncoMed Provides Update on Tarextumab Phase 2 Pancreatic Cancer ALPINE Trial. 2016 [press release] http://investor.shareholder.com/oncomed/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID=951460. Accessed June 27, 2016.

- 73.Van Cutsem E, Lenz H, Furuse J, et al. Evofosfamide (TH-302) in combination with gemcitabine in previously untreated patients with metastatic or locally advanced unresectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: primary analysis of the randomized, double-blind phase III MAESTRO study [abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl 4S) Abstract 193. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Incyte announces decision to discontinue JANUS studies of ruxolitinib plus capecitabine in patients with advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer. [press release]. http://www.incyte.com/ir/press-releases.aspx. Accessed June 27, 2016.

- 75.Immunomedics provides update on phase 3 PANCRIT-1 trial of clivatuzumab tetraxetan in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. [press release]. http://www.immunomedics.com/pdfs/news/2016/pr03142016.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2016.