Abstract

Introduction

Data on management of atrial fibrillation (AF) in the Balkan Region are scarce. To capture the patterns in AF management in contemporary clinical practice in the Balkan countries a prospective survey was conducted between December 2014 and February 2015, and we report results pertinent to the use of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs).

Methods

A 14-week prospective, multicenter survey of consecutive AF patients seen by cardiologists or internal medicine specialists was conducted in Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Montenegro, Romania, and Serbia (a total of about 50 million inhabitants).

Results

Of 2712 enrolled patients, 2663 (98.2%) had complete data relevant to oral anticoagulant (OAC) use (mean age 69.1 ± 10.9 years, female 44.6%). Overall, OAC was used in 1960 patients (73.6%) of whom 338 (17.2%) received NOACs. Malignancy [odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.06, 1.20–3.56], rhythm control (OR 1.64, 1.25–2.16), and treatment by cardiologists were independent predictors of NOAC use (OR 2.32, 1.51–3.54) [all p < 0.01)], whilst heart failure and valvular disease were negatively associated with NOAC use (both p < 0.01). Individual stroke and bleeding risk were not significantly associated with NOAC use on multivariate analysis.

Conclusions

NOACs are increasingly used in AF patients in the Balkan Region, but NOAC use is predominantly guided by factors other than evidence-based decision-making (e.g., drug availability on the market or reimbursement policy). Efforts are needed to establish an evidence-based approach to OAC selection and to facilitate the optimal use of OAC, thus improving the outcomes in AF patients in this large region.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-017-0589-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Adherence to guidelines, Atrial fibrillation, Balkan Region, Bleeding risk, Clinical practice, Evidence-based approach, General cardiology, Oral anticoagulation, Stroke prevention, Stroke risk

Introduction

Oral anticoagulants (OAC), either non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) or vitamin K antagonists (VKAs), effectively reduce thromboembolism associated with atrial fibrillation (AF), and long-term OAC treatment is recommended to all AF patients with one or more additional stroke risk factors [1, 2]. Compared to VKAs, NOACs are effective, safe, and relatively convenient [3], but their use in routine clinical practice may be influenced by a variety of “non-medical” factors such as economic considerations and local health policy.

Accumulating data from real-world observational registry-based studies offer insights into the uptake and patterns of NOAC use in routine clinical practice [4, 5]. However, data on AF management in the Balkan Region are generally scarce, in contrast to other parts of Europe. To capture the patterns of AF management in routine practice in the Balkan Region, the Serbian Atrial Fibrillation Association (SAFA) conducted a prospective 3-month survey of consecutive AF patients in clinical practice in seven Balkan countries. In this paper, we report results pertinent to the uptake and patterns of NOAC use in participating Balkan countries.

Methods

Study Design

A detailed report on the Balkan-AF study protocol has been published previously [6]. From December 2014 to February 2015 a 14-week prospective, multicenter “snapshot” survey of consecutive patients with electrocardiographically documented AF was conducted in Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Montenegro, Romania, and Serbia (a total of about 50 million inhabitants). Each country participated with university and non-university hospitals and outpatient health centers situated inside and outside the capital cities. Patients were seen by cardiologists or internal medicine specialists (in the centers where a cardiologist was not readily available). Patients younger than 18 years and those with prosthetic mechanical heart valves or significant valve disease requiring surgical repair were not included.

The Balkan-AF survey was designed and conducted by SAFA, a non-profit association of expert physicians dedicated to the management of AF and research. The survey was announced to the national cardiology societies and relevant working groups or associations in Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Former Yugoslav Republic Macedonia, Montenegro, Romania, Slovenia, and Serbia. In the participating countries the Balkan-AF survey was approved by the national and/or local institutional review board, or the need for approval was waived according to the regulations in the respective country. Where requested by the local policy, a signed patient informed consent was obtained before enrollment. As a result of its cross-sectional snapshot design, we have not formally registered the study.

Data Collection

Data were collected via a web-based electronic case report form (CRF), with a range of prespecified plausibility checks for the entries. The CRF was formulated to obtain the following information (see Appendix 1 for details): (i) patients’ characteristics—demographic data, cardiovascular risk factors, medical history, AF-related data (i.e., symptoms, AF clinical type, prior history of AF), prior use of antithrombotic medication, antiarrhythmic drugs or other therapies, (ii) health-care setting and patient’s presentation (i.e., university or non-university health center, in-hospital or outpatient setting, internal medicine specialist or cardiologist, main reason for enrolling visit or hospitalization, emergency or non-emergency setting, length of hospitalization, etc.), (iii) AF management at enrolling visit or hospitalization (i.e., medication, cardioversion, AF ablation) and further management strategy post discharge, and (iv) diagnostic procedures performed because of AF during the enrolling visit/hospitalization or within the last 12 months (the latter was not applicable to patients with first-diagnosed AF).

As a result of the relatively short duration of the survey, systematic monitoring of centers was not performed. The national coordinators and all investigators are the guarantors of the consecutiveness of enrollment, accuracy, and completeness of data. The CRF, patient files, and medical records (paper or database) serve as source documents.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables with normal distribution were presented as mean (±SD) or those with a skewed distribution as median with interquartile range (IQR, 25th–75th quartile). Categorical variables were reported as counts with percentages. Student’s t test was used for comparison of continuous variables with normal distribution and the Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables with a skewed distribution. Differences in categorical variables were tested by the Chi-square test.

Univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to investigate the associations of demographic data, patient clinical characteristics, AF characteristics, and health-care setting with the use of NOACs. Variables statistically significant on univariate analysis were entered into the multivariable model to identify independent predictors of OAC use. Results are reported as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). A two-sided p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

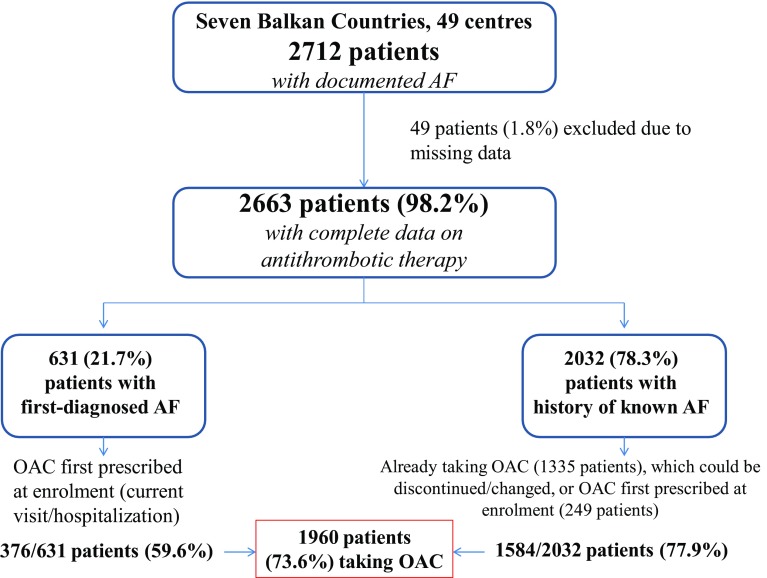

A total of 2712 patients were enrolled in 49 centers from seven Balkan countries. Full data on antithrombotic therapy prescribed before and at current visit/hospitalization were available in 2663 patients (98.2%) with either first-diagnosed AF (n = 631, 21.7%) or a history of prior AF (n = 2032, 78.3%), Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study flowchart. AF atrial fibrillation, OAC oral anticoagulants

Of 631 patients with first-diagnosed AF, OAC therapy was given to 376 patients (59.6%), whilst in 2032 patients with a history of prior AF the use of OAC increased from 1335 patients (65.7%), before the enrolling visit or hospitalization, to 1584 patients (77.9%) after the enrolling visit or at discharge. Thus, a total of 1960 patients were given OAC (73.6% of 2663 patients), Fig. 1.

Overall Use of NOACs

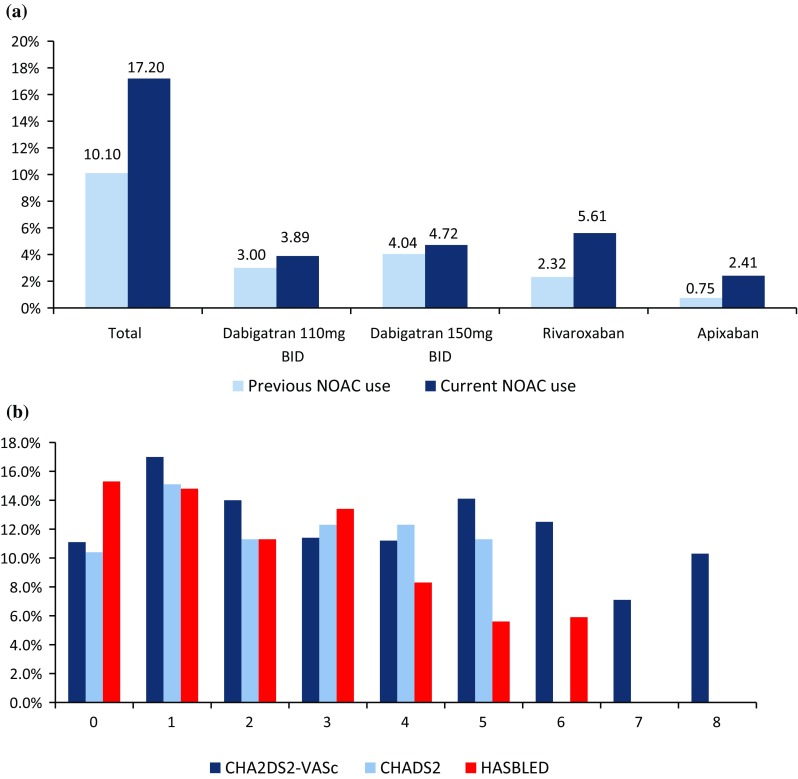

After the enrolling visit or at hospital discharge, the use of NOACs significantly increased from 135 patients already taking a NOAC before enrollment (10.1% of 1335 patients) to a total of 338 patients (17.2% of 1960 patients taking OAC after the enrolling visit or hospitalization), p < 0.001 (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

a Proportion of NOACs use within the overall use of OAC before the enrollment visit/hospitalization (light blue) and after the enrolling visit/at discharge (dark blue). b Use of NOACs across the stroke (CHA2DS2-VASc and CHADS2) and bleeding (HAS-BLED) risk strata. NOAC non-vitamin K oral anticoagulant

Of 175 patients given dabigatran, 96 (54.9%) were prescribed the 150-mg dose, whilst 79 (45.1%) received the 110-mg dose; of 114 patients taking rivaroxaban, 82 (71.9%) were given 20 mg once daily [the remaining 32 patients (28.1%) were prescribed the 15-mg dose], and of 49 patients taking apixaban, 38 (77.6%) were prescribed the 5-mg dose, whilst 11 patients (22.4%) received apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily. Edoxaban was not available in any of participating countries during the survey.

Determinants of NOAC Use Relative to VKAs

This analysis included 1960 patients who were given OAC at the enrolling visit or hospital discharge (Fig. 1). Demographic features, stroke and bleeding risk, AF characteristics, clinical parameters, treatment strategies, and health-care setting are shown in Table 1. Mean age in the OAC group was 68.95 ± 10.25 years, and there were no significant differences in demographic features among patients given NOACs or VKAs. Patients receiving NOACs had lower stroke and bleeding risk and were more frequently first diagnosed with AF and less frequently had permanent AF compared with patients who were given VKAs (Table 1). The use of NOACs across the stroke and bleeding risk strata is shown in Fig. 2b, where no consistent trends were seen for stroke risk scores, whilst NOAC use was less common at high HASBLED score.

Table 1.

Univariate analyses of the association of demographic, stroke and bleeding risk factors, AF characteristics, clinical parameters, treatment strategies, and health-care setting with NOAC use; and independent predictors of NOAC use in patients given OAC therapy

| All (NOAC and VKA) n = 1960 (%) |

NOAC n = 338 (12.7) |

VKA n = 1622 (82.8) |

p | OR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analyses | |||||||

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age (mean) | 68.95 ± 10.25 | 68.47 ± 11.50 | 69.05 ± 9.97 | 0.345 | 0.99 | 0.98–1.01 | 0.345 |

| Age <65 years (%) | 633 (32.3) | 117 (34.6) | 516 (31.8) | 0.338 | 1.14 | 0.89–1.45 | 0.316 |

| Age 65–74 years (%) | 663 (33.8) | 104 (30.8) | 559 (34.5) | 0.206 | 0.85 | 0.66–1.09 | 0.192 |

| Age ≥75 years (%) | 664 (33.9) | 117 (34.6) | 547 (33.7) | 0.752 | 1.04 | 0.81–1.33 | 0.753 |

| Age ≥80 years (%) | 269 (13.7) | 56 (16.6) | 213 (13.1) | 0.099 | 1.31 | 0.95–1.81 | 0.096 |

| Female gender (%) | 874 (44.6) | 144 (42.6) | 730 (45.0) | 0.435 | 0.91 | 0.72–1.15 | 0.419 |

| Current smoker (%) | 239 (12.2) | 48 (14.2) | 191 (11.8) | 0.235 | 1.24 | 0.88–1.74 | 0.216 |

| Ever smoker (%) | 587 (29.9) | 102 (30.2) | 485 (29.9) | 0.948 | 1.01 | 0.79–1.31 | 0.920 |

| Alcohol abuse (%) | 80 (4.1) | 17 (5.0) | 63 (3.9) | 0.363 | 1.31 | 0.76–2.27 | 0.334 |

| Body mass index | 28.03 ± 4.43 | 27.71 ± 4.07 | 28.10 ± 4.51 | 0.134 | 0.98 | 0.95–1.01 | 0.134 |

| Stroke and bleeding risk | |||||||

| CHA2DS2-VASc cont. | 3.49 ± 1.72 | 3.33 ± 1.74 | 3.53 ± 1.72 | 0.051 | 0.93 | 0.87–1.00 | 0.051 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc ≥2 (%) | 1703 (86.9) | 280 (82.2) | 1423 (87.7) | 0.021 | 0.68 | 0.49–0.93 | 0.016 |

| CHADS2 cont. | 2.17 ± 1.25 | 2.09 ± 1.27 | 2.19 ± 1.25 | 0.177 | 0.94 | 0.86–1.03 | 0.177 |

| CHADS2 ≥2 (%) | 1304 (66.5) | 206 (60.9) | 1098 (67.7) | 0.019 | 0.75 | 0.59–0.95 | 0.017 |

| HASBLED cont. | 2.02 ± 1.25 | 1.79 ± 1.16 | 2.07 ± 1.26 | <0.001 | 0.83 | 0.75–0.92 | <0.001 |

| HASBLED ≥3 (%) | 634 (32.2) | 93 (27.5) | 541 (33.4) | 0.041 | 0.76 | 0.59-0.98 | 0.037 |

| Characteristics of AF | |||||||

| Symptomatic AFa (%) | 1526 (77.9) | 263 (77.8) | 1263 (77.9) | 1.000 | 0.99 | 0.75–1.32 | 0.966 |

| Permanent AF (%) | 862 (44.0) | 109 (32.2) | 753 (46.4) | <0.001 | 0.55 | 0.43–0.70 | <0.001 |

| Paroxysmal AF (%) | 589 (30.1) | 115 (34.0) | 474 (29.2) | 0.090 | 1.25 | 0.97–1.60 | 0.080 |

| First diagnosed AFb (%) | 376 (19.2) | 85 (25.2) | 291 (18.0) | 0.003 | 1.54 | 1.17–2.03 | 0.002 |

| Clinical parameters | |||||||

| Heart failure ever (%) | 873 (44.6) | 119 (35.2) | 754 (46.5) | <0.001 | 0.57 | 0.44–0.73 | <0.001 |

| Heart failure at presentation (%) | 827 (42.7) | 106 (31.4) | 721 (44.5) | <0.001 | 0.63 | 0.49-0.80 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 1603 (81.8) | 288 (85.2) | 1315 (81.1) | 0.075 | 1.35 | 0.97–1.86 | 0.074 |

| Coronary artery disease (any) (%) | 568 (29.0) | 86 (25.4) | 482 (29.7) | 0.129 | 0.81 | 0.62–1.05 | 0.114 |

| Stable CAD (%) | 406 (20.7) | 58 (17.2) | 348 (21.5) | 0.077 | 0.76 | 0.56–1.03 | 0.076 |

| PCI (%) | 162 (8.3) | 28 (8.3) | 134 (8.3) | 1.000 | 1.00 | 0.66–1.54 | 0.989 |

| Prior MI (%) | 247 (12.6) | 23 (6.8) | 224 (13.8) | <0.001 | 0.46 | 0.29–0.71 | 0.001 |

| Prior CABG (%) | 73 (3.7) | 6 (1.8) | 67 (4.1) | 0.039 | 0.42 | 0.18–0.98 | 0.044 |

| Vascular disease (any) (%) | 401 (20.5) | 57 (16.9) | 344 (21.2) | 0.075 | 0.75 | 0.55–1.03 | 0.072 |

| PAD (%) | 93 (4.7) | 16 (4.7) | 77 (4.8) | 1.000 | 1.00 | 0.58–1.74 | 0.999 |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy (%) | 183 (9.3) | 22 (6.5) | 161 (9.9) | 0.051 | 0.63 | 0.40–1.00 | 0.051 |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (%) | 40 (2.0) | 5 (1.5) | 35 (2.2) | 0.529 | 0.68 | 0.27–1.75 | 0.425 |

| Valve disease (%) | 715 (36.5) | 80 (23.7) | 635 (39.1) | <0.001 | 0.48 | 0.37–0.63 | <0.001 |

| Mitral valve disease (%) | 653 (33.3) | 75 (22.2) | 578 (35.6) | <0.001 | 0.52 | 0.39–0.68 | <0.001 |

| Aortic valve disease (%) | 212 (10.8) | 22 (6.5) | 190 (11.7) | 0.004 | 0.53 | 0.33–0.83 | 0.006 |

| Other cardiac disease (%) | 158 (8.1) | 14 (4.1) | 144 (8.9) | 0.003 | 0.44 | 0.25–0.78 | 0.005 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 488 (24.9) | 78 (23.1) | 410 (25.3) | 0.408 | 0.89 | 0.67–1.17 | 0.395 |

| Chronic kidney disease (%) | 309 (15.8) | 56 (16.6) | 253 (15.6) | 0.682 | 1.07 | 0.78–1.47 | 0.660 |

| CKD on dialysis (%) | 5 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (2.0) | 0.589 | 0.00 | 0.00–0.00 | 0.999 |

| COPD (%) | 234 (11.9) | 29 (8.6) | 205 (12.6) | 0.042 | 0.65 | 0.43–0.98 | 0.038 |

| Sleep apnea (%) | 42 (2.1) | 5 (1.5) | 37 (2.3) | 0.589 | 0.64 | 0.25–1.65 | 0.358 |

| Dementia (%) | 40 (2.0) | 3 (0.9) | 37 (2.3) | 0.136 | 0.38 | 0.12–1.25 | 0.112 |

| Thyroid disease (%) | 219 (11.2) | 48 (14.2) | 171 (10.5) | 0.058 | 1.40 | 0.99–1.98 | 0.053 |

| Liver disease (%) | 63 (3.2) | 14 (4.1) | 49 (3.0) | 0.308 | 1.39 | 0.76–2.54 | 0.290 |

| Malignancy (%) | 82 (4.2) | 22 (6.5) | 60 (3.7) | 0.025 | 1.81 | 1.10–3.00 | 0.021 |

| Anemia (%) | 244 (12.5) | 34 (10.1) | 210 (13.0) | 0.148 | 0.75 | 0.51–1.10 | 0.144 |

| Prior bleedinga (%) | 93 (4.7) | 21 (6.2) | 72 (4.4) | 0.160 | 1.43 | 0.87–2.36 | 0.161 |

| Prior stroke (%) | 209 (10.7) | 36 (10.7) | 173 (10.7) | 1.000 | 1.00 | 0.68–1.46 | 0.994 |

| Prior TIA (%) | 57 (2.9) | 13 (3.8) | 44 (2.7) | 0.284 | 1.43 | 0.76–2.69 | 0.263 |

| Prior pulmonary embolism (%) | 42 (2.1) | 3 (0.9) | 39 (2.4) | 0.097 | 0.36 | 0.11–1.18 | 0.093 |

| Prior systemic TE (%) | 17 (0.9) | 1 (0.3) | 16 (1.0) | 0.335 | 0.30 | 0.04–2.26 | 0.242 |

| Treatment strategies | |||||||

| Planned electrical cardioversion (%) | 92 (4.7) | 23 (6.8) | 69 (4.2) | 0.048 | 1.64 | 1.01–2.68 | 0.046 |

| Planned AF ablation (%) | 56 (3.5) | 12 (3.6) | 44 (2.7) | 0.373 | 1.32 | 0.69–2.53 | 0.402 |

| Rhythm control (%) | 639 (32.6) | 154 (45.6) | 485 (29.9) | <0.001 | 1.96 | 1.55–2.49 | <0.001 |

| Rate control (%) | 1261 (64.6) | 179 (53.4) | 1082 (66.9) | <0.001 | 0.57 | 0.45–0.72 | <0.001 |

| Prior OAC therapy (%) | 1335 (68.1) | 155 (45.8) | 1180 (72.7) | <0.001 | 0.39 | 0.29–0.52 | <0.001 |

| Dual therapy (%) | 240 (12.2) | 26 (7.7) | 214 (13.2) | 0.005 | 0.59 | 0.36–0.84 | 0.006 |

| Triple therapy (%) | 83 (4.2) | 11 (3.3) | 72 (4.4) | 0.375 | 0.33 | 0.38–1.38 | 0.328 |

| Health-care setting | |||||||

| Capital city center (%) | 986 (50.3) | 187 (55.3) | 799 (49.3) | 0.048 | 1.28 | 1.01–1.61 | 0.043 |

| Hospital-based center (%) | 1813 (92.3) | 273 (80.8) | 1540 (94.9) | <0.001 | 0.22 | 0.16–0.32 | <0.001 |

| Outpatient center (%) | 147 (7.5) | 65 (19.2) | 82 (5.1) | <0.001 | 4.47 | 3.15–6.35 | <0.001 |

| University center (%) | 1613 (89.0) | 244 (89.4) | 1369 (88.9) | 0.917 | 1.05 | 0.69–1.59 | 0.815 |

| Treatment by a cardiologist (%) | 1594 (81.3) | 310 (91.7) | 1284 (79.2) | <0.001 | 2.91 | 1.94–4.37 | <0.001 |

| Multivariable analysis | |||||||

| Heart failure at current visit | 0.65 | 0.48–0.87 | 0.004 | ||||

| Valve disease | 0.66 | 0.49–0.88 | 0.006 | ||||

| Malignancy | 2.06 | 1.20–3.56 | 0.009 | ||||

| Rhythm control strategy | 1.64 | 1.25–2.16 | <0.001 | ||||

| Dual therapy | 0.54 | 0.34–0.86 | 0.009 | ||||

| Prior OAC therapy | 0.59 | 0.48–0.71 | <0.001 | ||||

| Treatment by a cardiologist | 2.32 | 1.51–3.54 | <0.001 | ||||

| Hospital-based center | 0.25 | 0.17–0.37 | <0.001 | ||||

NOAC non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant, VKA vitamin K antagonist, AF atrial fibrillation, CAD coronary artery disease, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, MI myocardial infarction, CABG coronary artery bypass grafting, PAD peripheral arterial disease, CKD chronic kidney disease, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, TIA transient ischemic attack, TE thromboembolic event, OAC oral anticoagulan

aData missing for one patient

bUnknown for 3 patients

Patients with heart failure (HF), prior myocardial infarction (MI) or prior surgical revascularization (CABG), valvular heart disease, or other cardiac disease, and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) were less likely to receive NOACs than VKAs, whilst patients with malignancy were more often given NOACs. There was no significant difference between NOAC and VKA use in patients with prior stroke or other thromboembolism or history of bleeding events (Table 1).

Rhythm control strategy (OR 1.96, 95% CI 1.55–2.49) and electrical cardioversion (OR 1.64, 95% CI 1.01–2.68) were associated with increased NOAC use compared to VKA, whilst the use of NOACs was less likely with rate control, prior OAC therapy, or combination of OAC with antiplatelet drugs (Table 1). Patients treated in the capital city centers (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.01–1.61) and patients treated by a cardiologist (OR 2.91, 95% CI 1.94-4.37) were given NOACs more frequently than VKAs, whilst patients treated by physicians from hospital-based centers were less likely to receive NOACs (Table 1).

Independent Predictors of NOAC Use

On multivariate analysis (Table 1), only malignancy was an independent predictor of preference for NOACs (OR 2.06, 95% CI 1.20–3.56, p = 0.009), whilst HF and valvular heart disease were negative predictors of NOAC use (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.48–0.87, p = 0.004 and OR 0.66, 95% CI 0.49–0.88, p = 0.006, respectively).

A rhythm control strategy was an independent predictor of increased NOAC use (OR 1.64, 95% CI 1.25–2.16, p < 0.001), whilst prior OAC use and combination of OAC with antiplatelet drugs were predictors of less NOAC use (OR 0.59, 95% CI 0.48–0.71, p < 0.001 and OR 0.54, 95% CI 0.34–0.86, p = 0.009, respectively). Treatment by a cardiologist was a positive independent predictor of NOAC use (OR 2.32, 95% CI 1.51–3.54, p < 0.001), and treatment in a hospital-based center was negatively associated with NOAC use (OR 0.25, 95% CI 0.17–0.37, p < 0.001).

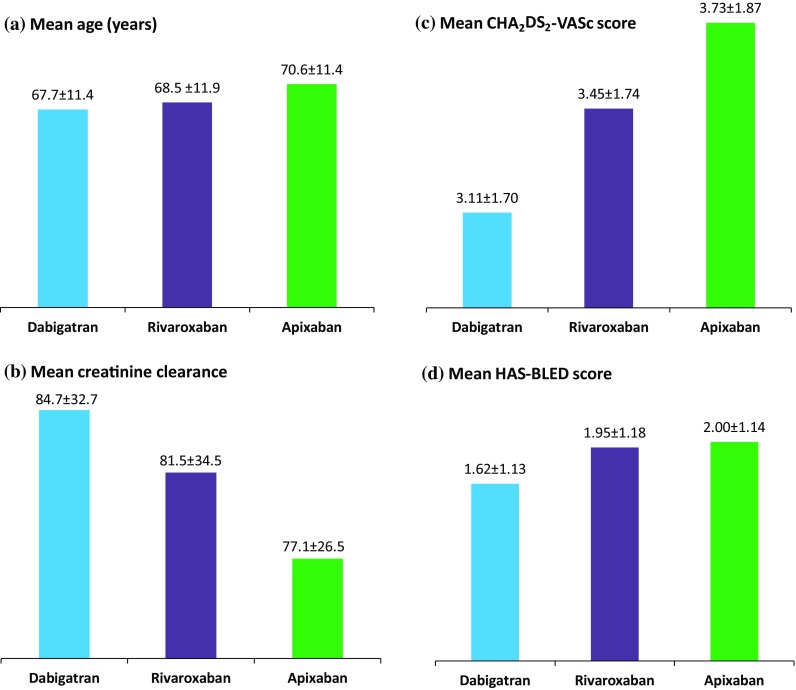

Drug-Specific Patterns of NOAC Use

As shown in Fig. 3, dabigatran was generally given to younger patients, with higher creatinine clearance and lower stroke and bleeding risks, as measured by the CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED score, whilst rivaroxaban and especially apixaban were prescribed to patients with less favorable risk profiles (i.e., elderly, with lower creatinine clearance and higher stroke and bleeding risks).

Fig. 3.

Drug-specific patterns of NOAC use. Creatinine clearance (mL/min) was calculated using the Cockcroft–Gault equation

The use of apixaban was higher than the use of rivaroxaban or dabigatran in patients treated in the capital city centers [n = 35/49 (71.4%), n = 64/114 (56.1%), and n = 88/175 (50.3%), respectively, p < 0.01] or the university centers [n = 42/46 (91.3%), n = 95/114 (83.3%), and n = 108/175 (61.7%), respectively, p < 0.01]. Apixaban was more often prescribed to patients with prior stroke/TIA compared to rivaroxaban or dabigatran [n = 8/49 (16.3%), n = 13/114 (11.4%), and n = 15/175 (8.6%), respectively, p < 0.01], whilst dabigatran was more often used in patients undergoing cardioversion compared to rivaroxaban or apixaban [n = 19/115 (10.9%), n = 3/114 (2.6%), and n = 1/49 (2.0%), respectively, p < 0.05].

Switching From NOACs to VKAs or Vice Versa

Before the enrolling visit 135 patients were taking NOACs for a mean of 9.53 ± 8.17 months, and at the enrolling visit/hospitalization NOACs were switched to VKAs in only 4 patients (3.0%). No reason for switching from NOACs could be elucidated from patients’ medical history (including bleeding events).

VKAs were switched to NOACs in 41 of 1198 patients previously taking VKAs (3.4%), and the switch was performed almost exclusively by a cardiologist (n = 40, 97.6%). Independent predictors of switch to NOACs (adjusted for country and physician’s specialty) were a HAS-BLED of at least 3 (OR 2.24, 95% CI 1.17–4.28, p = 0.015) and treatment in the capital city center (OR 2.20, 95% CI 1.08–4.48, p = 0.031), whilst concomitant mild-to-moderate valvular disease was a negative predictor of the treatment change (OR 0.34, 95% CI 0.16–0.76, p = 0.008).

Of note, the time in therapeutic range (TTR) in the previous 3 months was available in only 224 (18.7%) of 1198 patients who were previously taking a VKA for at least 6 months or longer. Of those patients, 158 had a TTR of less than 65%, but only seven such patients (4.4%) were switched from VKAs to NOACs.

Discussion

This survey provides a unique contemporary insight into the use of NOACs in seven countries of the Balkan Region, which were largely underrepresented in recent European registries. We also provide data on the independent predictors of NOAC use, drug-specific patterns of NOAC use, and features related to switching from NOACs to VKAs (or vice versa).

Our findings suggest that the use of NOACs in the Balkan Region is similar to that in other European countries [4, 7], but is not driven by patients’ clinical features or individual stroke and bleeding risk profile. Instead, a mixture of determinants of NOAC use were identified, suggesting that factors other than evidence-based medicine played an important role when deciding whether to use NOACs or VKAs, thus modifying the decision-making process beyond medical reasons. Our findings have important clinical implications, suggesting the need for a structured decision-making algorithm(s) which would facilitate evidence-based choices between NOACs and VKAs in routine daily clinical practice in order to ensure optimal thromboprophylaxis in all AF patients eligible for OAC [8]. This need would be applicable not only for the Balkan region but also for Europe and other regions of the world.

At the Balkan-AF enrolling visit/hospitalization, NOACs were prescribed to 17.2% of all patients given OAC, which represented a significant increase in NOAC use compared to the period before enrollment. Of note, NOACs were not reimbursed in most of the participating countries (excluding Bulgaria) during the survey period.

Evidence shows that the use of VKAs is associated with positive net clinical benefit in all AF patients with at least one stroke risk factor, across all bleeding risk strata, and that NOACs may offer additional benefit in comparison to VKAs in most AF patients eligible for OAC [9–11]. Indeed, European AF guidelines clearly favor NOACs over VKAs in most AF patients [1, 2], but the guidelines were only modestly implemented in routine clinical practice in Balkan countries [12]. As could be expected, patients treated by a cardiologist were more likely to receive NOACs compared to patients seen by internal medicine specialists [13].

Nonetheless, the use of NOACs was less likely with increasing stroke and bleeding risk. Indeed, only few parameters were positively associated with preference for NOACs (Table 1), whilst a number of “negative” associations were observed: patients with any cardiac disease (excluding hypertension), patients receiving a combination of OAC and antiplatelet drugs, those assigned to a rate control strategy, patients previously on OAC, and patients treated in hospital-based centers were more likely to receive VKAs than NOACs.

First-diagnosed AF was associated with greater likelihood of NOAC use only on univariate analysis. In general, most patients with first-diagnosed AF would be OAC-naive, and evidence clearly shows that the inception period of VKA therapy is associated with increased risk of thromboembolic and bleeding events due to suboptimal anticoagulant effect [14–16]. On multivariable analysis, however, concomitant diseases such as mild-to-moderate mitral or aortic valve disease or HF, therapies (e.g., combination of OAC with antiplatelet drugs), and health-care setting (i.e., treatment in hospital-based centers) were clearly “prohibitive” of NOAC use. This could be partly explained by reasons such as barriers in translation from NOAC trials to clinical practice [17], underrepresentation of patients with “valvular” AF in NOAC trials [18] or increased risk of bleeding with combination of OAC and antiplatelet drugs [19], etc. In addition, it could be speculated that cardiologists hesitated to use NOACs in sicker patients (as suggested by lower rates of NOAC use in patients with concomitant cardiac diseases and in patients treated in hospital-based centers).

However, certain co-morbidities (i.e., malignancy) and clinical scenarios (e.g., rhythm control treatment strategy) were “positive” independent predictors of preference for NOACs (Table 1). We speculate that anticipation of limited duration of OAC therapy might be linking these factors, although the use of OAC in patients with documented AF should be guided not by the estimate of successful rhythm control but the presence of additional stroke risk factors [1, 20].

Although the number of patients given NOACs in the Balkan-AF survey was small, the drug-specific patterns of NOAC use seen in our study broadly resemble those seen in the large observational administrative claims-based studies or nationwide administrative registries from the USA and Europe, showing that dabigatran is generally more often given to younger patients with less co-morbidity, whilst rivaroxaban and especially apixaban are more frequently prescribed to AF patients with less favorable risk profiles [21–23]. Such uniformity in the predominating patterns of NOAC use in various geographical regions likely results from the respective landmark NOAC trial design and results (e.g., the high-risk study population in the ROCKET-AF [24], favorable safety of apixaban in the ARISTOTLE [25] trial, etc.). In addition, similar to findings in other real-world reports [22, 26], the lower/reduced dose of respective NOAC was used in a greater proportion of patients in the Balkan-AF survey compared to the RE-LY (randomization to dabigatran 150 mg or 110 mg twice daily) [27], ROCKET-AF (20.7% of patients randomized to rivaroxaban) [24], and ARISTOTLE trial (4.7% of patients randomized to apixaban) [25]. Although the use of lower/reduced NOAC doses in real-world observational studies is generally driven by worse patients’ risk profile, underdosing (i.e., inappropriate use of the lower or reduced NOAC dose, discordant to the drug label and formal recommendations on NOAC use) is also likely in daily clinical practice, including the Balkan Region.

Data on the mean TTR in the Balkan-AF survey (although limited) suggest that low TTR was not decisive for switching from VKAs to NOACs. This is despite formal recommendations that a TTR of greater than 70% should be achieved to optimize efficacy and safety with the VKAs, as evident from various studies [16, 28, 29]. Overall, patients with cardiac co-morbidities or those with increased stroke or bleeding risk were more likely to be given VKAs, and other patients apparently could get NOACs mostly if they could afford to pay for the medication. Clearly, a more systematic, evidence-based approach to selection of OAC is needed to optimize thromboprophylactic treatment effects.

Recently, the SAMe-TT2R2 score has been proposed, assigning 1 point each to female sex, age of less than 60 years, history of at least two co-morbidities and treatment with drugs interacting with VKAs (e.g., amiodarone) and 2 points each to tobacco use and non-Caucasian ethnicity [30, 31]. The score performed well in identifying patients who were likely to have a good TTR, whilst a SAMe-TT2R2 value of greater than 2 was predictive of poor TTR, all-cause mortality, and composite endpoint of thromboembolic events, major bleeding, and mortality [32, 33]. Hence, the SAMe-TT2R2 could help decision-making regarding the choice between VKAs or NOACs in routine clinical practice, whereby AF patients with a SAMe-TT2R2 score of 0 to 2 could be given VKAs, whilst patients with a SAMe-TT2R2 score of greater than 2 should be started on NOACs. This concept is attractive, but needs to be confirmed by prospective, adequately powered trial(s).

Limitations

This study has all the limitations of observational snapshot survey design. Nonetheless, we made every effort to include consecutive patients. By recruiting a range of different types of centers in each country (i.e., university and non-university hospitals and outpatient centers inside and outside the capital cities) we tried to capture a sample representative of real-world clinical practice, but there still may be a selection bias due to variable health-care setting in the participating countries.

The proportion of cardiologists versus internal medicine specialists participating in the Balkan-AF survey may not be fully reflective of daily clinical practice in the participating countries, and we might have not adequately covered the rural areas. Nevertheless, participating centers situated outside the capital cities enrolled about 55% of patients, and in smaller countries many AF patients are often referred to the tertiary centers at least for initial evaluation.

As many as 95.6% of patients with a TTR of less than 65% were not switched to NOACs in our survey, but TTR was available in only a small proportion of patients treated with VKAs, thus precluding a reliable analysis of relationship between the quality of VKA therapy as measured by TTR and transition to NOACs. In addition, the total number of patients prescribed NOACs was small, which precluded a detailed analysis of the dosing patterns (and possible underdosing) in clinical practice. Increasing availability of NOACs and changes in the reimbursement policy after the Balkan-AF survey completion may change the picture captured by the survey.

Conclusion

Our results show that NOACs are increasingly used for stroke prevention in AF patients in the Balkan Region. However, the choice between NOACs and VKAs is predominantly guided by factors other than evidence-based decision-making (e.g., drug availability on the market or local reimbursement policy). The patterns of drug-specific NOAC use were broadly similar to other real-world observational US and European studies. Nevertheless, greater efforts are needed in the Balkan Region to establish a more systematic evidence-based approach to selection of OAC and to facilitate optimal use of both VKAs and NOACs in order to maximize benefits and minimize risks associated with OAC, thus improving the outcomes in AF patients in Balkan countries.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank all Balkan-AF investigators and Ms Zlatiborka Mijatovic for their hard work and contribution. No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

The BALKAN-AF Investigators List: Romania: Gheorghe-Andrei Dan, Rodica Musetescu, Mircea Ioachim Popescu, Elisabeta Badila, Catalina Arsenescu Georgescu, Sorina Pop, Raluca Popescu, Simina Neamtu, Floriana Oancea, Anca Rodica Dan. Serbia: Tatjana Potpara, Marija Polovina, Srdjan Milanov, Gorana Mitic, Marko Milanov, Jelena Savic, Snezana Markovic, Ivana Koncarevic, Jelena Gavrilovic, Marija Pavlovic, Dijana Djikic, Marijana Petrovic, Stefan Simovic, Semir Malic, Jusuf Hodzicl, Milovan Stojanovic, Sanja Gnip, Milan Zlatar, Dragan Matic, Snezana Lazic, Tijana Acimovic, Pavica Radovic, Vladan Peric, Sanja Markovic, Snezana Kovacevic, Aleksandra Arandjelovic, Milika Asanin, Milan M Nedeljkovic, Marija Zdravkovic, Marina Deljanin Ilic. Bulgaria: Elina Trendafilova, Elena Dimitrova, Stanislav Petranov, Delyana Kamenova, Penka Kamenova, Svetoslava Elefterova, Valentin Shterev, Maria Zekova, Stela Diukiandzhieva, Evgenii Goshev, Boiko Dimitrov, Tihomir Sotirov, Valentina Simeonova, Anna Velichkova, Dimitrina Drianovska, Liliya Ivanova Vasileva Boiadzhieva, Darina Buchukova. Albania: Artan Goda, Vilma Paparisto, Viktor Gjini, Uliks Ekmekciu, Hortensia Gjergo, Alma Mijo, Ervina Shirka, Ina Refatllari. Bosnia and Herzegovina: Zumreta Kusljugic, Daniela Loncar, Belma Pojskic, Denis Mrsic, Alma Sijamija, Amira Bijedic, Irma Bijedic, Indira Karamujic, Sanela Halilovic, Hazim Tulumovic, Sekib Sokolovic. Croatia: Sime Manola, Sandro Brusich, Ivan Zeljkovic, Ante Anic, Nikola Pavlovic, Vjekoslav Radeljic, Melita Jeric, Petar Pekic, Kresimir Milas. Montenegro: Ljilja Music, Ana Nenezic, Nebojsa Bulatovic, Dijana Asanovic.

Disclosures

Tatjana S. Potpara: speaker fees from Pfizer and Bayer. Elina Trendafilova: speaker fees from Bayer, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Astra Zeneca, Servier, Merck Serono, Gedeon Richter, Actavis, and Berlin Chemie. Gheorghe-Andrei Dan: speaker fees from Boehringer Ingelheim. Artan Goda, Zumreta Kusljugic, Sime Manola, Viktor Gjini, Belma Pojskic, Mircea Ioakim Popescu, Catalina Arsenescu Georgescu, Elena S. Dimitrova, Delyana Kamenova, Uliks Ekmeciu, Denis Mrsic, and Ana Nenezic have no conflicts of interest to declare. Ljilja Music: speaker fees from Bayer and Boehringer Ingelheim. Sandro Brusich: speaker fees from Bayer, Pfizer, and Boehringer Ingelheim. Gregory Y.H. Lip: consultant fees from Bayer, Merck, Sanofi, BMS/Pfizer, Daiitchi-Sankyo, Biotronic, Medtronic, Portola, and Boehringer Ingelheim and speaker fees from Bayer, BMS/Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiitchi-Sankyo, and Medtronic.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The survey was announced to the national cardiology societies and relevant working groups or associations in Albania, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Former Yugoslav Republic Macedonia, Montenegro, Romania, Slovenia, and Serbia. In the participating countries the Balkan-AF survey was approved by the national and/or local institutional review board, or the need for approval was waived according to the regulations in the respective country. Where requested by the local policy, a signed patient informed consent was obtained before enrollment.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

The members of BALKAN-AF Survey investigators are listed in Acknowledgements section.

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/00E8F06071EFA7AA.

Contributor Information

Tatjana S. Potpara, Email: tatjana.potpara@med.bg.ac.rs

On behalf of the BALKAN-AF Investigators:

Gheorghe-Andrei Dan, Rodica Musetescu, Mircea Ioachim Popescu, Elisabeta Badila, Catalina Arsenescu Georgescu, Sorina Pop, Raluca Popescu, Simina Neamtu, Floriana Oancea, Anca Rodica Dan, Tatjana Potpara, Marija Polovina, Srdjan Milanov, Gorana Mitic, Marko Milanov, Jelena Savic, Snezana Markovic, Ivana Koncarevic, Jelena Gavrilovic, Marija Pavlovic, Dijana Djikic, Marijana Petrovic, Stefan Simovic, Semir Malic, Jusuf Hodzic, Milovan Stojanovic, Sanja Gnip, Milan Zlatar, Dragan Matic, Snezana Lazic, Tijana Acimovic, Pavica Radovic, Vladan Peric, Sanja Markovic, Snezana Kovacevic, Aleksandra Arandjelovic, Milika Asanin, Milan M. Nedeljkovic, Marija Zdravkovic, Marina Deljanin Ilic, Elina Trendafilova, Elena Dimitrova, Stanislav Petranov, Delyana Kamenova, Penka Kamenova, Svetoslava Elefterova, Valentin Shterev, Maria Zekova, Stela Diukiandzhieva, Evgenii Goshev, Boiko Dimitrov, Tihomir Sotirov, Valentina Simeonova, Anna Velichkova, Dimitrina Drianovska, Liliya Ivanova Vasileva Boiadzhieva, Darina Buchukova, Artan Goda, Vilma Paparisto, Viktor Gjini, Uliks Ekmekciu, Hortensia Gjergo, Alma Mijo, Ervina Shirka, Ina Refatllari, Zumreta Kusljugic, Daniela Loncar, Belma Pojskic, Denis Mrsic, Alma Sijamija, Amira Bijedic, Irma Bijedic, Indira Karamujic, Sanela Halilovic, Hazim Tulumovic, Sekib Sokolovic, Sime Manola, Sandro Brusich, Ivan Zeljkovic, Ante Anic, Nikola Pavlovic, Vjekoslav Radeljic, Melita Jeric, Petar Pekic, Kresimir Milas, Ljilja Music, Ana Nenezic, Nebojsa Bulatovic, and Dijana Asanovic

References

- 1.Camm AJ, Lip GY, De Caterina R, et al. 2012 focused update of the ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2719–2747. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS: the task force for the management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Endorsed by the European Stroke Organisation (ESO). Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2893–2962. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Husted S, de Caterina R, Andreotti F, et al. Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs): no longer new or novel. Thromb Haemost. 2014;111:781–782. doi: 10.1160/TH14-03-0228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lip GY, Laroche C, Ioachim PM, et al. Prognosis and treatment of atrial fibrillation patients by European cardiologists: one year follow-up of the EURObservational Research Programme-Atrial Fibrillation General Registry Pilot Phase (EORP-AF Pilot registry) Eur Heart J. 2014;35:3365–3376. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu JC, Akao M, Abe M, et al. International collaborative partnership for the study of atrial fibrillation (INTERAF): rationale, design, and initial descriptives. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e004037. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Potpara TS, Balkan AFI, Lip GY. Patterns in atrial fibrillation management and ‘real-world’ adherence to guidelines in the Balkan Region: an overview of the Balkan-atrial fibrillation survey. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:1943–1944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirchhof P, Ammentorp B, Darius H, et al. Management of atrial fibrillation in seven European countries after the publication of the 2010 ESC guidelines on atrial fibrillation: primary results of the prevention of thromboemolic events—European registry in atrial fibrillation (PREFER in AF) Europace. 2014;16:6–14. doi: 10.1093/europace/eut263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shields AM, Lip GY. Choosing the right drug to fit the patient when selecting oral anticoagulation for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. J Intern Med. 2015;278(1):1–8. doi: 10.1111/joim.12360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friberg L, Rosenqvist M, Lip GY. Net clinical benefit of warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a report from the Swedish atrial fibrillation cohort study. Circulation. 2012;125:2298–2307. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.055079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banerjee A, Lane DA, Torp-Pedersen C, Lip GY. Net clinical benefit of new oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban) versus no treatment in a ‘real world’ atrial fibrillation population: a modelling analysis based on a nationwide cohort study. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107:584–589. doi: 10.1160/TH11-11-0784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skjoth F, Larsen TB, Rasmussen LH, Lip GY. Efficacy and safety of edoxaban in comparison with dabigatran, rivaroxaban and apixaban for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. An indirect comparison analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2014;111:981–988. doi: 10.1160/TH14-02-0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Potpara TS, Dan GA, Trendafilova E, et al. Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation and ‘real world’ adherence to guidelines in the Balkan Region: the Balkan-AF survey. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20432. doi: 10.1038/srep20432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lo-Ciganic WH, Gellad WF, Huskamp HA, et al. Who were the early adopters of dabigatran?: an application of group-based trajectory models. Med Care. 2016;54:725–732. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hylek EM, Evans-Molina C, Shea C, Henault LE, Regan S. Major hemorrhage and tolerability of warfarin in the first year of therapy among elderly patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2007;115:2689–2696. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.653048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azoulay L, Dell’Aniello S, Simon TA, Renoux C, Suissa S. Initiation of warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: early effects on ischaemic strokes. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1881–1887. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Caterina R, Husted S, Wallentin L, et al. Vitamin K antagonists in heart disease: current status and perspectives (section iii). Position paper of the ESC working group on thrombosis–task force on anticoagulants in heart disease. Thromb Haemost. 2013;110:1087–1107. doi: 10.1160/TH13-06-0443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hylek EM, Ko D, Cove CL. Gaps in translation from trials to practice: non-vitamin k antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Thromb Haemost. 2014;111:783–788. doi: 10.1160/TH13-12-1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Caterina R, Camm AJ. What is ‘valvular’ atrial fibrillation? A reappraisal. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:3328–3335. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lip GY, Windecker S, Huber K, et al. Management of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome and/or undergoing percutaneous coronary or valve interventions: a joint consensus document of the European Society of Cardiology working group on thrombosis, European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) and European Association of Acute Cardiac Care (ACCA) endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) and Asia-Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS) Eur Heart J. 2014;35:3155–3179. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freedman B, Potpara TS, Lip GY. Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Lancet. 2016;388:806–817. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Potpara TS. Dabigatran in ‘real-world’ clinical practice for stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Thromb Haemost. 2015;114:1093–1098. doi: 10.1160/TH15-10-0825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lip GY, Keshishian A, Kamble S, et al. Real-world comparison of major bleeding risk among non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients initiated on apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or warfarin. A propensity score matched analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2016;116:975–986. doi: 10.1160/TH16-05-0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yao X, Abraham NS, Sangaralingham LR, et al. Effectiveness and safety of dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(6):003725. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:883–891. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:981–992. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larsen TB, Skjoth F, Nielsen PB, Kjaeldgaard JN, Lip GY. Comparative effectiveness and safety of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants and warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: propensity weighted nationwide cohort study. BMJ. 2016;353:i3189. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139–1151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sjogren V, Grzymala-Lubanski B, Renlund H, et al. Safety and efficacy of well managed warfarin. A report from the Swedish quality register auricula. Thromb Haemost. 2015;113(6):1370–1377. doi: 10.1160/TH14-10-0859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gallego P, Roldan V, Marin F, et al. Cessation of oral anticoagulation in relation to mortality and the risk of thrombotic events in patients with atrial fibrillation. Thromb Haemost. 2013;110:1189–1198. doi: 10.1160/TH13-07-0556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Apostolakis S, Sullivan RM, Olshansky B, Lip GY. Factors affecting quality of anticoagulation control among patients with atrial fibrillation on warfarin: the SAMe-TT(2)R(2) score. Chest. 2013;144:1555–1563. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Proietti M, Lip GY. Simple decision-making between a vitamin K antagonist and non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant: using the SAMe-TT2R2 score. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother 2015;1:150–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Gallego P, Roldan V, Marin F, et al. SAMe-TT2R2 score, time in therapeutic range, and outcomes in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation. Am J Med. 2014;127:1083–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lip GY, Haguenoer K, Saint-Etienne C, Fauchier L. Relationship of the SAMe-TT(2)R(2) score to poor-quality anticoagulation, stroke, clinically relevant bleeding, and mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2014;146:719–726. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.