Abstract.

The purpose of this study was to formulate a systematic, evidence-based method to relate quantitative diagnostic performance to radiation dose, enabling a multidimensional system to optimize computed tomography imaging across pediatric populations. Based on two prior foundational studies, radiation dose was assessed in terms of organ doses, effective dose (), and risk index for 30 patients within nine color-coded pediatric age-size groups as a function of imaging parameters. The cases, supplemented with added noise and simulated lesions, were assessed in terms of nodule detection accuracy in an observer receiving operating characteristic study. The resulting continuous accuracy–dose relationships were used to optimize individual scan parameters. Before optimization, the nine protocols had a similar of with accuracy decreasing from 0.89 for the youngest patients to 0.67 for the oldest. After optimization, a consistent target accuracy of 0.83 was established for all patient categories with ranging from 1 to 10 mSv. Alternatively, isogradient operating points targeted a consistent ratio of accuracy–per-unit-dose across the patient categories. The developed model can be used to optimize individual scan parameters and provide for consistent diagnostic performance across the broad range of body sizes in children.

Keywords: children, pediatric, lung nodule, computed tomography, image quality, diagnostic accuracy, radiation dose, size-specific protocols

1. Introduction

Patient size is a dominant factor in dose and quality in medical imaging, particularly in pediatric imaging given the wide range of body sizes from newborn to teenage patients. This necessitates a size-specific approach toward pediatric computed tomography (CT). This has been well recognized1,2 and has further been made practical through size-specific pediatric CT protocols, such as the color-coded Broselow–Luten system.3 Ideally, a size-specific protocol for a pediatric examination is defined based on diagnostic accuracy for a task of interest, and a targeted balance between the accuracy and patient dose. But designing such an optimized protocol tailored to the patient size may only be achieved if the three-way dependency of quality, dose, and size is ascertained. Considering the size adaptation offered in modern CT systems through automated tube current modulation (TCM), one can assume that protocols no longer need explicit patient size accommodation. However, current TCM technologies do not target diagnostic accuracy; they aim to reduce variability in noise across patient sizes only, which does not directly translate to consistency in diagnostic task.

There have been a number of excellent prior efforts to formulate size-specific protocols for pediatric CT.4–9 They have shown potential for dose saving, further enhanced with the use of iterative reconstruction algorithms.10 CT dose management is made practical with the use of diagnostic reference levels (DRLs).11 However, most prior efforts rely on radiation dose alone; if image quality is included, it is in terms of preference-based subjective metrics. Furthermore, these paradigms rarely include the larger continuum of the relationship between quality and dose. Precise optimization requires objective quantitative metrology, not only for dose but also image quality,6,7 a task that has been proven difficult to achieve.12 Phantom-based physical image quality metrics can be ascribed to clinical images (as is the case for most TCM algorithms), but to be most informative clinically for a given pathology, they would need to be translated into diagnostic accuracy.

This paper offers a methodology to ascertain the interdependency of patient size, dose, and task-based image quality across the range of pediatric sizes. The basis for the estimation and optimization of image quality was image quality data pertaining to the detection of lung nodules representing pulmonary metastatic diseases.13–15 This task was chosen as the detection of these lesions has critical implications for patient care (e.g., for tumor staging, treatment planning, and prognosis). Pediatric cancer patients often undergo a large number of CT scans, and unlike adult cancers, over 70% of pediatric cancers are curable, making the task of protocol optimization even more critical.16 The methodology was devised based on contributing data from prior investigations providing independent quantitative components of dose and quality. The goal was to determine dose quality curves for the range of pediatric CT protocols to determine where nodule detection tasks may be optimized based on the size of patients. Piloted for one specific CT system, the methodology was devised such that it could serve as a template of optimizations for other indications, diagnostic tasks, and technologies.

2. Materials and Methods

This work involved the development of a framework for balancing quality and safety for varying pediatric patient sizes. The study drew from two foundational prior studies but deployed new characterizations using an original and not previously described methodology. The patient data included anonymized CT images of 30 pediatric patients. The institutional review board approved this study and waived informed consent.

2.1. Optimization Framework

To approach optimization in imaging based on quality and safety, there are four main requirements: first, radiation safety requires quantification with metrics (or indices) reasonably related to patient risk. Second, image quality should likewise be characterized with metrics reasonably correlated with the clinical indication. Third, the above two dependent parameters should be linked to the image acquisition factors, the independent parameters of the optimization process. Doing so establishes the user-controlled factors, which affect the image quality and patient dose. Finally, the determination of these metrics and their proper balance should be approached in the context of the individual patient, aligned with the growing international call for personalized imaging.17 This is due to the fact that the quality and safety of an examination are highly dependent on the specifics of the patient (e.g., anatomy and age) and the indication: a dose that is proper for one patient or one indication may be grossly elevated or insufficient for another. In the midst of great variability in clinical practice, appropriate adjustments in the examination to achieve the balance between quality and safety are meaningful only when done with consideration for the individual patient.

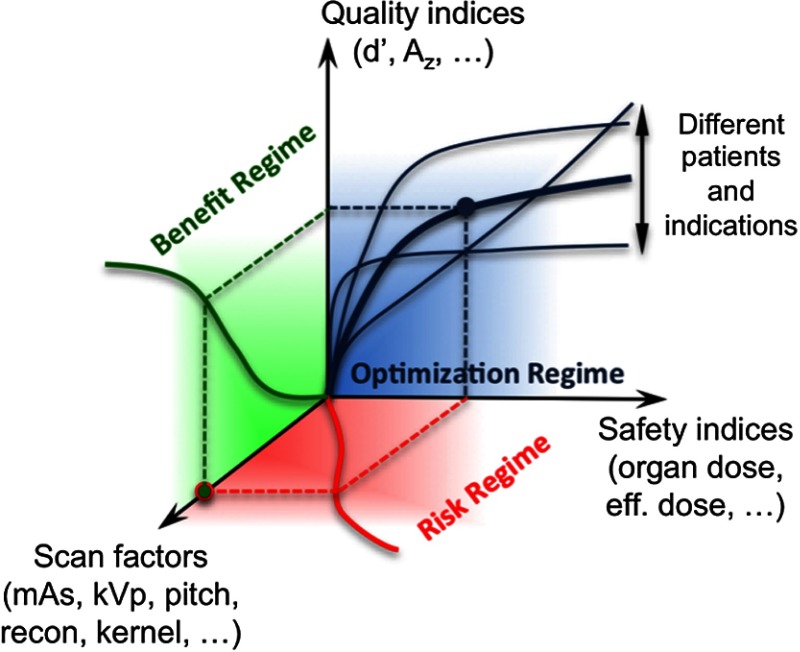

The above approach and relationship form a framework that can be visualized by way of a three-dimensional (3-D) graph of safety indices, quality indices, and the (multidimensional) scan factors that govern the image acquisition process (Fig. 1). The safety, quality, and scan factors then are boundaries, further classified depending on the location within the 3-D structure of the risk, benefit, and patient individualization. As a scan parameter is changed, it can potentially change the irradiation burden to the patient of a specific attribute (e.g., size), illustrated in the “risk regime” in this figure. The change in the parameter similarly can invoke a change in quality (e.g., likelihood of the detection of the indication of interest) in the resultant image, illustrated in the “benefit regime” of this Figure. Ascertaining these regimes enables the establishment of the relationship between quality and safety indices for an individual patient and examination (“optimization regime” of Fig. 1). Once the optimization space is ascertained, the individualized decisions and adjustments to the acquisition parameters or CT techniques can be made based on adherence to targeted diagnostic quality for particular abnormalities, dose levels, or any combination of the two. This enables the practitioner to minimize the dose for any given examination while simultaneously safeguarding its clinical utility.

Fig. 1.

The optimization framework.

Practically speaking, personalized CT requires the use of patient-specific, surrogate indices of radiation safety and image quality, and a method for prospectively determining these indices for an individual patient. A prior study18 in pediatric chest CT characterized image quality in terms of detection accuracy and scan parameters. A second study likewise determined organ doses as a function of patient size and scan parameters.19 Below is an outline of these studies and the process to put their findings in terms of the framework of Fig. 1 as a model to ascertain task-based, quality-safety relationships in pediatric patients.

2.2. Study 1: Risk Dependency

Ascertaining the “risk regime” of Fig. 1, the first study was conducted to ascertain the relationship between organ doses and scan parameters as a function of patient size.19 Whole-body computational models were created for 30 pediatric patients (0 to 18 years) based on the patient’s clinical CT data. The models represented nine pediatric age/size categories based on a color-coded Broselow–Luten system in place at our institution (Table 1). The cases were unique (no repeat or follow-up scans) and largely equally distributed across the age categories. A validated Monte Carlo program modeling a typical commercial CT system (LightSpeed VCT, GE Healthcare) was used to estimate organ doses for the 30 patients undergoing chest CT scans using various combinations of scan parameters. The organ dose estimates were subsequently used to calculate patient-based effective dose, per ICRP.21 While ICRP uses as a metric of population-based radiation protection, the study applied it as a holistic metric of radiation burden to the patient, as now customarily applied in patient imaging (see Sec. 4).22,23 The effective dose values were subsequently related to the average diameter of the chest region as

| (1) |

where and are constants, and DLP is the dose length product. The methodology to determine is detailed in the Appendix.

Table 1.

Nine color-coded size-specific protocols for the examinations of pediatric chest on a 64-slice CT system (LightSpeed VCT, GE healthcare).

| Unit | Pink | Red | Purple | Yellow | White | Blue | Orange | Green | Black | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient parameters | Age range | Year | 0 to 0.5 | 0.5 to 1.0 | 1.0 to 1.8 | 1.8 to 3.2 | 3.2 to 5.2 | 5.2 to 7.3 | 7.3 to 9.2 | 9.2 to 13.5 | 13.5 to 18 |

| Median age | Year | 0.2 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 2.5 | 4.1 | 6.2 | 8.2 | 11.3 | 14.7 | |

| Weight range | kg | 5.5 to 7.4 | 7.5 to 9.4 | 9.5 to 11.4 | 11.5 to 14.4 | 14.5 to 18.4 | 18.5 to 23.4 | 23.5 to 29.4 | 29.5 to 36.4 | 36.5 to 55 | |

| Chest sizea | |||||||||||

| AP thickness | cm | 10.5 | 11.6 | 12.3 | 13.2 | 14.2 | 15.4 | 16.6 | 18.5 | 20.5 | |

| Transverse thickness | cm | 14.1 | 16.0 | 17.3 | 18.5 | 20.0 | 21.9 | 23.8 | 26.6 | 29.8 | |

| Diameter | cm | 12.2 | 13.6 | 14.6 | 15.6 | 16.9 | 18.4 | 19.9 | 22.2 | 24.7 | |

| WEDb | cm | 10.6 | 11.8 | 12.7 | 13.5 | 14.6 | 15.9 | 17.2 | 19.1 | 21.3 | |

| Height | cm | 9.2 | 9.5 | 10.1 | 11.0 | 12.3 | 14.0 | 15.6 | 18.1 | 20.8 | |

| Scan parameters | Tube voltage | kVp | 100 | 100 | 100 | 120 | 120 | 120 | 120 | 120 | 120 |

| Scan FOV typec | — | Ped body | Ped body | Small body | Small body | Small body | Medium body | Medium body | Medium body | Large body | |

| (Bowtie filter) | — | (Small) | (Small) | (Small) | (Small) | (Small) | (Medium) | (Medium) | (Medium) | (Large) | |

| Collimation | mm | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 40 | 40 | |

| Pitch | — | 0.969 | 0.969 | 0.969 | 1.375 | 1.375 | 1.375 | 1.375 | 1.375 | 1.375 | |

| Rotation time | s | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | |

| Slice thickness | mm | 2.5 | 3.75 | 3.75 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Reconstruction interval | mm | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | |

| Reconstruction algorithm | — | FBPd | FBP | FBP | FBP | FBP | FBP | FBP | FBP | FBP | |

| Reconstruction filter | — | Standard | Standard | Standard | Standard | Standard | Standard | Standard | Standard | Standard | |

| Operating points | Noise index | HU | 9.5 | 10 | 10.5 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| Min tube current | mA | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |

| Max tube currente | mA | 70 | 80 | 90 | 70 | 75 | 80 | 90 | 95 | 110 | |

| f | mGy | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.6 | |

| SSDEg | mGy | 3.3 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 4.1 | 4.4 | 3.9 | 4.0 | |

| Effective dose | mSv | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | |

| Noise in lung parenchyma | HU | 10 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 13 | 16 | |

| AUC | — | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 0.74 | 0.67 |

Appendix describes how metrics of chest size were determined based on age.

WED, water-equivalent diameter.

FOV, field-of-view. The correspondence between scan FOV and bowtie filter is based on the technical reference manual of the LightSpeed VCT system (5116422-100, Rev 6, GE Healthcare, 2006).

FBP, filtered back projection.

The maximum tube current values correspond to the upper limits of the tube currents when TCM is turned on. They also represent the constant tube currents used when TCM is turned off (for example, in situations where patients are uncooperative and accurate patient centering is difficult).

denotes volume-weighted CT dose index based on a 32-cm diameter phantom. was determined for each protocol using the method described in the technical reference manual of the LightSpeed VCT system (5116422-100, Rev 6, GE Healthcare, 2006).

SSDE, size-specific dose estimate. SSDE was calculated from using chest diameter and the size-specific conversion factor published in AAPM Task Group report 204.20

To account for the impact of age and gender, organ doses were also combined to characterize the patient burden in terms of the radiation risk index (RI)18,22

| (2) |

where is the absorbed dose to organ/tissue , and is the gender-, age-, and tissue-specific risk coefficient (cases/100,000 exposed to 0.1 Gy) for lifetime attributable risk of cancer incidence. Values of (gender, age) are tabulated in the BEIR VII.24 Like effective dose, RI incorporates the detriments of radiation exposure to various organs. However, unlike effective dose, RI is calculated using risk coefficients that are age- and gender-specific. As such, RI is not restricted to reference patients and is a preferred metric for optimizing CT examinations, taking the attributes of the patient into consideration.

As in the case of effective dose, the estimated RI values were further related to , age, and DLP as

| (3) |

where are gender-dependent constants, and is age. For the purpose of this study, we used RI values averaged for gender.

2.3. Study 2: Benefit Dependency

Ascertaining the “benefit regime” of Fig. 1, the second study aimed to ascertain the relationship between diagnostic image quality and scan parameters as a function of patient size.18 The study involved two specific steps. First, a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) experiment was performed ascertaining the detection of lung nodules as a function of varying imaging conditions. Clinical chest CT images of the thirty pediatric patients (0 to 18 years) were used to create three mA acquisition conditions (for one case, the mA was low and thus only one additional mA acquisition was rendered). The cases were replicated and embedded with 3-D realistically simulated subtle nodules, creating a total of 178 [() copies] cases of varying noise and randomized inserted lesions. Four experienced pediatric radiologists read the cases in a randomized fashion and scored their confidence pertaining to the presence of a lung nodule in each case. The accuracy of their detection was measured using the area under the ROC curve (AUC) as the measure of diagnostic image quality (or diagnostic performance). In addition, for each case, a physical surrogate of image quality was estimated as

| (4) |

where denotes the quantum noise in the lung regions of the image, is the peak contrast of the nodule, defined as the maximum Hounsfield unit (HU) difference between the nodule and lung parenchyma, and is the nodule diameter as displayed on the workstation used by the radiologists. This physical metric of image quality was found to be correlated with the measured diagnostic quality following the logistic function of

| (5) |

where are the constants. It should be noted that the coefficients of this relationship were discerned in the context of filtered-back projection reconstruction and a standard-resolution kernel. Different values are expected for different kernels and reconstructions including iterative reconstructions, which further exhibit additional dependencies on noise texture and dose-dependent resolution changes. However, the formalism can still be applied albeit updated coefficients.

In the second part of the study 2, each of the components of , quantum noise, nodule contrast, and nodule diameter, was individually related to patient size and scan parameter. For noise, uniform water phantoms with diameters ranging between 8.2 and 27.0 cm were scanned on a commercial CT scanner (LightSpeed VCT scanner, GE Healthcare). In CT imaging, in general, one expects noise to be related to the inverse square root of dose or mAs and exponential related to patient size. The study found that this dependency can be well characterized in terms of an exponential second-order polynomial as

| (6) |

where is the water phantom diameter, is the pitch, is the slice thickness, and mAs is tube-current-time product. The coefficients are functions of tube voltage and bowtie filter [determined by the choice of scan field of view (FOV)]. Equation (6) can be used to estimate quantum noise in the lung parenchyma regions of a chest CT image if water phantom diameter is substituted by the water-equivalent diameter of the chest 25 providing for noise to be expressed as a function of patient size and scan parameter.

In terms of contrast, as pediatric metastatic disease is rarely presented with calcification15 or evaluated with iodinated contrast,26 the nodule contrast mainly represents the contrast of low-density soft tissue as

| (7) |

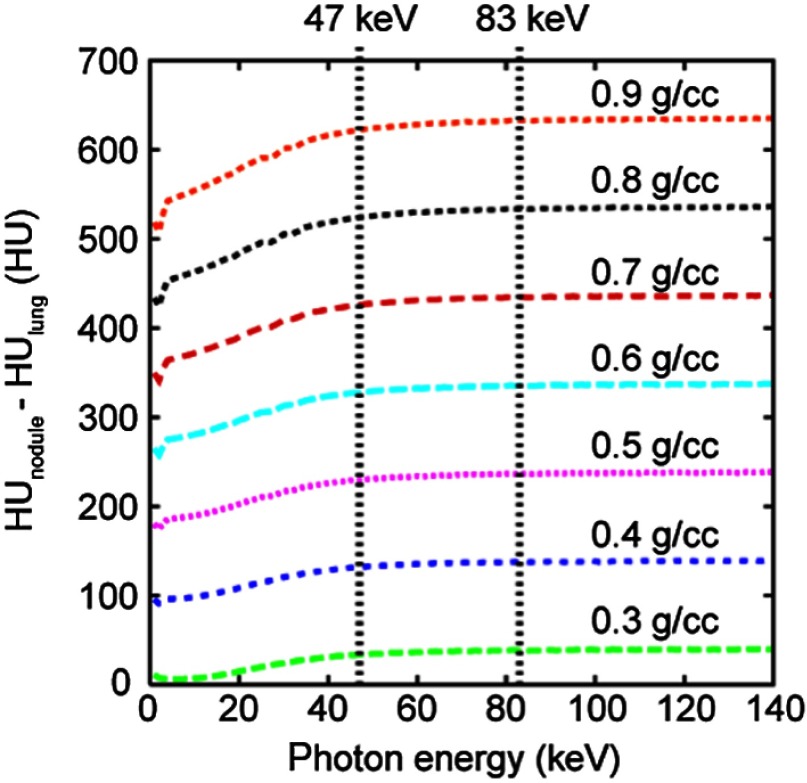

where is the linear attenuation coefficient. Using the atomic compositions of soft tissue and lung defined by ICRU Publication 46,27 was calculated for soft tissue density ranging within 0.3 to over a photon energy range of 1 to 140 keV (Fig. 2). Lung density was kept at per ICRU. For the full range of nodule densities, nodule contrast was found to remain nearly constant over the range of photon energies representative of clinical CT beams, presenting little dependence on the choice of tube voltage or the variation in patient size.

Fig. 2.

Nodule contrast as a function of photon energy for nodule densities ranging between 0.3 and . 47 and 83 keV are mean energies of the 80- and 120-kVp beams, respectively, when attenuated by 40 cm of water (representing the attenuation by an obese adult patient)28 and the most attenuating section of the bowtie filter (at beam angle of ).29

In the last component of , the displayed diameter of a nodule was characterized as

| (8) |

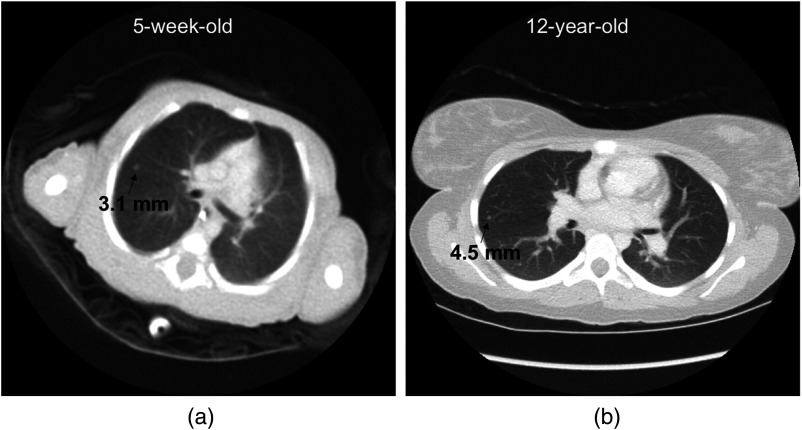

where is the actual (physical) diameter of the nodule, is the reconstruction FOV size, and is the side length of the image as displayed by the display device. Pediatric radiologists rarely use the zoom function when searching for (versus characterizing) lung nodules. Thus, for a given review workstation and display mode in 100% zoom mode, is a constant. Equation (8) indicates that the larger the reconstruction FOV (), the smaller the displayed diameter of a nodule (). This effect is also illustrated in Fig. 3 using images of two pediatric patients as examples.

Fig. 3.

Effect of reconstruction FOV size on the displayed diameter of a nodule. An image of a 12-year-old patient (b) has a larger reconstruction FOV size than an image of a 5-week-old patient (a). As a result, compared to the 4.5-mm diameter simulated nodule in the right image, the 3.1-mm diameter simulated nodule in the left image has a larger displayed diameter and appears larger to an observer.

Estimating the ingredients of Eq. (4) through Eqs. (6)–(8), physical image quality was characterized as function of patient size and scan parameters, which was then related to diagnostic performance per Eq. (5), as a description of the “benefit regime” of Fig. 1.

2.4. Optimization Dependency

The findings of the above steps were integrated to establish continuous relationships, and (i.e., accuracy–dose curves) for each of the nine color-coded protocols. These relationships can be recognized as dose efficiency gradients, the accuracy per dose expected to result a particular level of accuracy.

For each patient category, the median age was used as the basis for metrics of chest size (Appendix). The AUC was derived for a reference task, defined as the task for the detection of a nodule with diameter of 4 mm and peak contrast of 350 HU, values corresponding to the average diameter and peak contrast of the subtle lung nodules investigated in the observer study. To calculate the displayed diameter of a nodule [Eq. (8)], the reconstruction FOV was assumed to be 3.0 cm greater than the transverse thickness of the patient’s chest (Appendix), i.e., . was set to be 18.8 cm, which corresponds to the side length of a CT image when displayed in a 100% magnification mode on the workstations used by the pediatric radiologists. To delineate the continuous accuracy–dose relationships, tube current was serially reduced from 700 to 5 mA in 5-mA decrements.

3. Results

Given the magnitude of multiple dependencies represented in the results, they are presented below into four sections as the: 1) dependency between diagnostic quality and effective dose, 2) use the framework to ascertain the impact of scan parameters on the dependencies, 3) design of alternative protocols for more consistent diagnostic quality for each of the patient age/size groups, and 4) impact of representation of results as an RI.

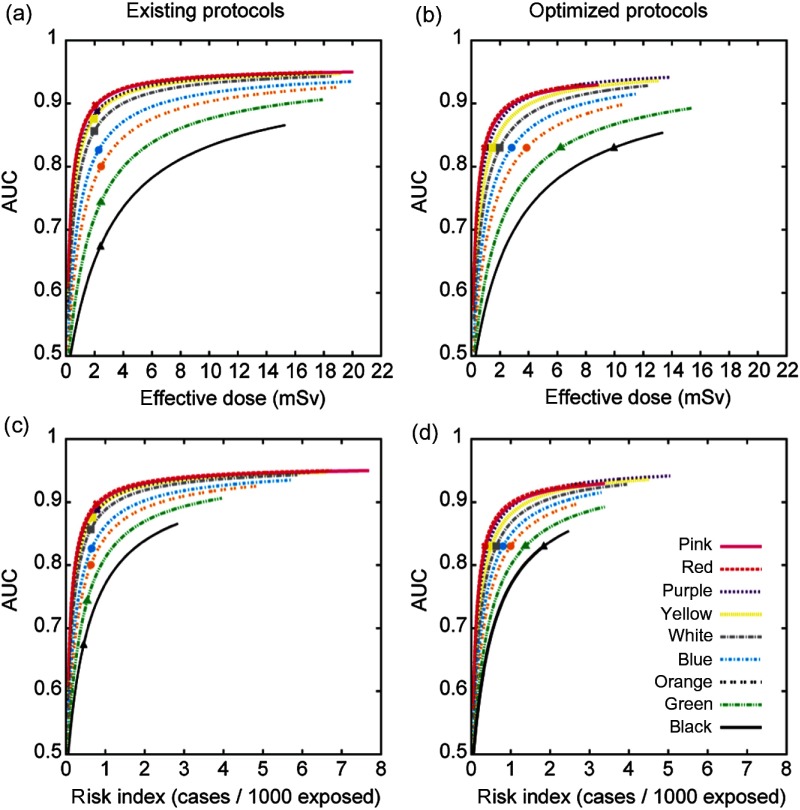

3.1. Effective Dose Dependency for Existing Protocols

In our existing protocols (Table 1), for each patient category, AUC initially increased rapidly with and then approached a plateau [Fig. 4(a)]. For example, taking the blue category (median age: 6.2 years), 1 mSv was required to achieve an AUC of 0.74. Raising the AUC from 0.74 to 0.80 required an additional of 0.7 mSv. However, the gain in AUC with increased dose diminished with further increasing the AUC: raising AUC from 0.80 to 0.85 required a larger additional of 1.3 mSv or doubling the dose increase needed for a similar incremental AUC increase. In other words, for every unit of dose increase, there was a diminishing gain in diagnostic accuracy especially at relatively higher dose levels. The nine existing protocols had a similar of with AUC decreasing from 0.89 for the youngest patient category to 0.67 for the oldest patient category. The average AUC across patient categories was .

Fig. 4.

Diagnostic accuracy (AUC) as a function of effective dose for the (a) existing and (b) optimized protocols. AUC as a function of gender-averaged RI for the (c) existing and (d) optimized protocols. Symbols on the curves correspond to the operating points for the corresponding protocols. Colors represent age/weight-based categories from youngest/least weight [pink, such as an infant to oldest/heaviest weight; black, such as a teenager (Table 1)].

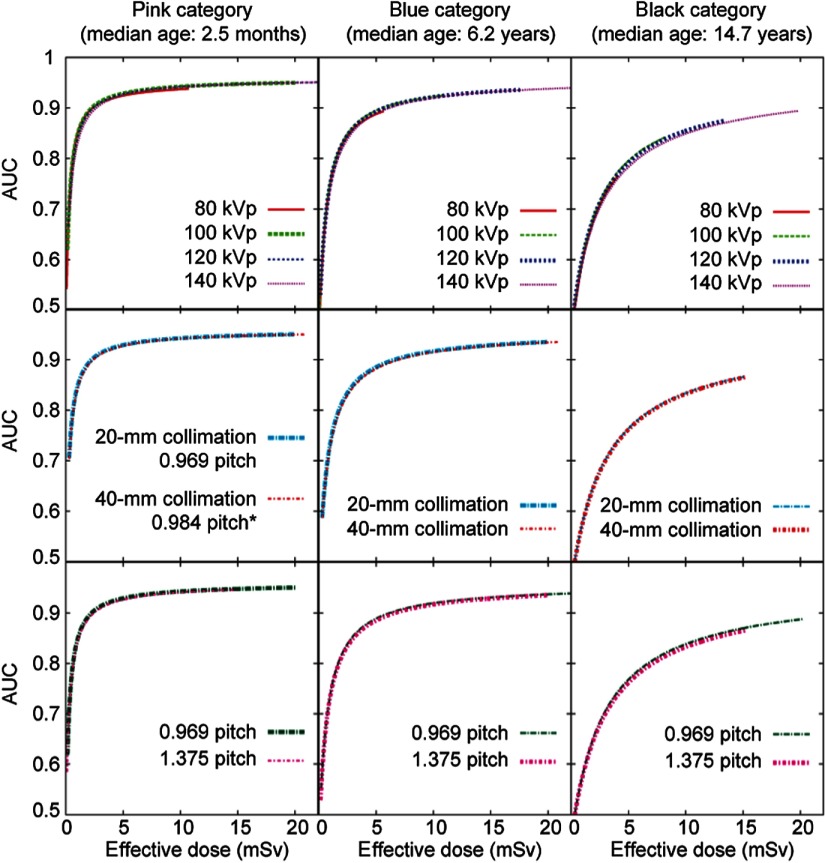

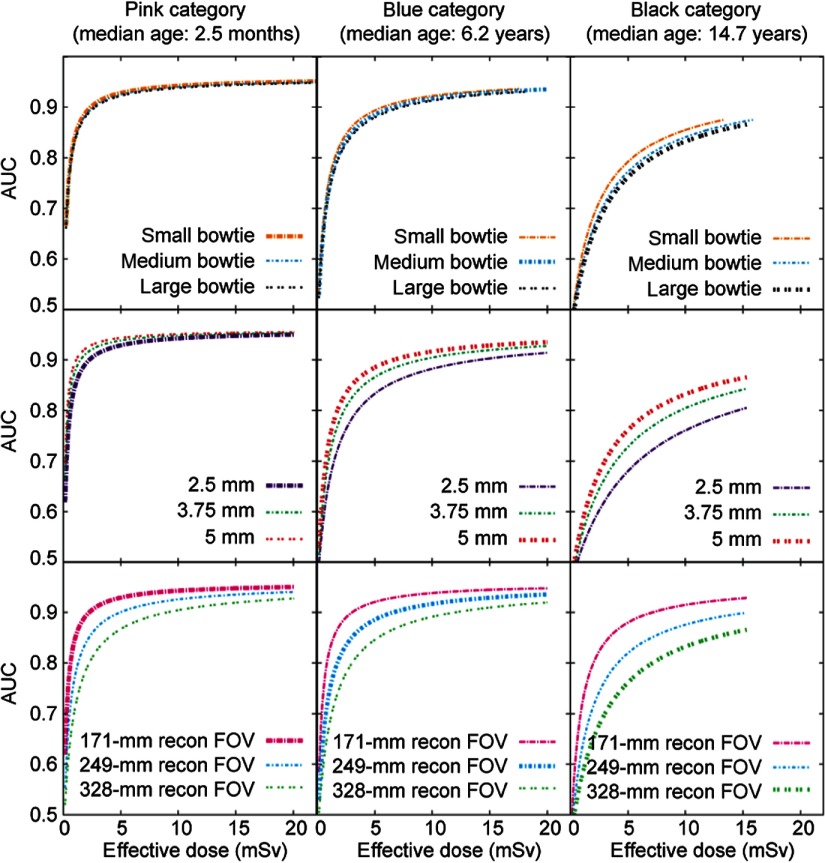

3.2. Optimized Imaging Parameters

For all patient categories, the accuracy–dose curves had little dependence on the choices of tube voltage, collimation, and pitch (Fig. 5). However, they depended substantially on the choices of scan FOV (bowtie filter), slice thickness, and reconstruction FOV (Fig. 6). For example, for the blue category (median age: 6.2 years), to maintain a target AUC of 0.83, decreasing the tube voltage from 120 to 80 kVp reduced by merely 0.02 mSv (1%), whereas decreasing the reconstruction FOV from 33 to 17 cm reduced by 3 mSv (72%). These results, as well as the considerations for scanning speed and other aspects of image quality, dictated the choices of individual scan parameters, as delineated below.

Fig. 5.

The effects of kVp, pitch, and collimation on dose efficiency. Three patient categories are illustrated as examples. In each subplot, the thick curve corresponds to the scan parameters in the existing protocol for the given patient category (Table 1). The other curves represent the adjustment of one scan parameter, while keeping all other scan parameters the same as for the thick curve. One exception is that when evaluating the effect of tube voltage, the “ped body” scan FOV (corresponding to the small bowtie filter) was used for all patient categories. Another exception is that when evaluating the effect of scan FOV (i.e., bowtie filter), 120 kVp was used for all patient categories.

Fig. 6.

The effects of bowtie filter, slice thickness, and FOV on dose efficiency. Three patient categories are illustrated as examples. In each subplot, the thick curve corresponds to the scan parameters in the existing protocol for the given patient category (Table 1). The other curves represent the adjustment of one scan parameter, while keeping all other scan parameters the same as for the thick curve. One exception is that when evaluating the effect of tube voltage, the “ped body” scan FOV (corresponding to the small bowtie filter) was used for all patient categories. Another exception is that when evaluating the effect of scan FOV (i.e., bowtie filter), 120 kVp was used for all patient categories.

3.2.1. Tube voltage

Given that no tube voltage was found to be more dose efficient than other tube voltages for the task of detecting subtle lung nodules in the pediatric age group, tube voltage was chosen to optimize other aspects of imaging performance. The lowest tube voltage 80 kVp could have been chosen for all the patient categories to maximize soft tissue contrast (i.e., contrast between muscle and fat). However, compared to a higher tube voltage, to maintain the same image noise at 80 kVp, a higher tube current would be needed. When the required tube current exceeds system limit, either the pitch needs to be reduced or the rotation time needs to be increased. Either approach prolongs the total scan time and increases the possibility of nonrandom motion artifact and impact of periodic motion (breathing and cardiac motion).

3.2.2. Collimation, pitch, and rotation time

Given the negligible effects of collimation and pitch on dose efficiency, those two scan parameters were chosen to maximize scanning speed while providing desired spatial resolution. For all patient categories, the maximum beam collimation (40 mm) and the second largest pitch (1.375) available on LightSpeed VCT system were chosen to maximize scanning speed. Although a higher pitch of 1.75 is also available on the CT system, earlier research on multislice CT systems has shown that the slice sensitivity profile begins to deteriorate when pitch is increased to 1.75.30 To maximize scanning speed, the shortest gantry rotation time available for noncardiac scans (0.4 s at the time of the investigations) was selected for all patient categories.

3.2.3. Scan field of view

For all patient categories, the small bowtie filter provided the highest dose efficiency (Fig. 6). It corresponds to the “ped body” or “small body” scan FOV. When the “ped body” scan FOV is chosen, the system reports based on a 16-cm diameter phantom. When the “small body” scan FOV is chosen, the system reports based on a 32-cm diameter phantom. To avoid confusion in the reported , “ped body” scan FOV was chosen for all patient categories.

3.2.4. Slice thickness and reconstruction interval

Dose efficiency was found to increase appreciably with increasing slice thickness (Fig. 6). This is because when dose is kept constant, using a thicker slice reduces image noise. However, as the reference task was the detection of a 4-mm nodule, to reduce partial volume effect, the slice thickness for the last six patient categories was reduced from 5 to 3.75 mm. The slice thickness was kept at 2.5 mm for the youngest patient category to allow the clear visualization of other small anatomical structures in the youngest patients (newborn to half year of age). Earlier research has indicated the benefits of overlapping slices on the detection of small nodules.26 Thus, the reconstruction interval was chosen to be 1.25 mm for the youngest patient category and 2.5 mm for other categories.

3.2.5. Reconstruction field of view

Dose efficiency was found to increase substantially with decreasing reconstruction FOV size (Fig. 6). Thus, the optimized display FOV size was the smallest possible for a given patient size.

3.3. Clinical Operating Dose Levels

Based on the above results, an optimized set of protocols was devised as detailed in Table 2. Figure 4(b) shows the accuracy–dose curves generated using the optimized scan parameters. The average AUC across patient categories was . All metrics of radiation dose increased roughly linearly with patient age ranging between 1.4 and 2.6 mGy for (32-cm phantom), 3.3 to 4.4 mGy for SSDE, and 1.9 to 2.4 mSv for effective dose. The target AUC was set to be 0.83, the average AUC across patient categories provided by the existing protocols. To achieve this target AUC, the required ranged from 1 mSv for the youngest patient category to 10 mSv for the oldest patient category. The corresponding levels of quantum noise in the lungs ranged between 15 and 8 HU, decreasing with increasing patient size (Table 2). To achieve these levels of quantum noise, the required noise indices, derived using the findings of a recent study,31 decreased from 21 HU for the youngest patient category to 12 HU for the oldest patient category.

Table 2.

Optimized protocols based on similar AUCs for the examinations of pediatric chest on a 64-slice CT system (LightSpeed VCT, GE Healthcare).

| Category | Unit | Pink | Red | Purple | Yellow | White | Blue | Orange | Green | Black | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient parameters | Age range | Year | 0 to 0.5 | 0.5 to 1.0 | 1.0 to 1.8 | 1.8 to 3.2 | 3.2 to 5.2 | 5.2 to 7.3 | 7.3 to 9.2 | 9.2 to 13.5 | 13.5 to 18 |

| Median age | Year | 0.2 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 2.5 | 4.1 | 6.2 | 8.2 | 11.3 | 14.7 | |

| Weight range | kg | 5.5 to 7.4 | 7.5 to 9.4 | 9.5 to 11.4 | 11.5 to 14.4 | 14.5 to 18.4 | 18.5 to 23.4 | 23.5 to 29.4 | 29.5 to 36.4 | 36.5 to 55 | |

| Chest size | |||||||||||

| AP thickness | cm | 10.5 | 11.6 | 12.3 | 13.2 | 14.2 | 15.4 | 16.6 | 18.5 | 20.5 | |

| Transverse thickness | cm | 14.1 | 16.0 | 17.3 | 18.5 | 20.0 | 21.9 | 23.8 | 26.6 | 29.8 | |

| Diameter | cm | 12.2 | 13.6 | 14.6 | 15.6 | 16.9 | 18.4 | 19.9 | 22.2 | 24.7 | |

| WEDa | cm | 10.6 | 11.8 | 12.7 | 13.5 | 14.6 | 15.9 | 17.2 | 19.1 | 21.3 | |

| Height | cm | 9.2 | 9.5 | 10.1 | 11.0 | 12.3 | 14.0 | 15.6 | 18.1 | 20.8 | |

| Scan parameters | Tube voltage | kVp | 80 | 80 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 120 | 120 |

| Scan FOV typeb | — | Ped body | Ped body | Ped body | Ped body | Ped body | Ped body | Ped body | Ped body | Ped body | |

| (Bowtie filter) | — | (Small) | (Small) | (Small) | (Small) | (Small) | (Small) | (Small) | (Small) | (Small) | |

| Collimation | mm | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | |

| Pitch | — | 1.375 | 1.375 | 1.375 | 1.375 | 1.375 | 1.375 | 1.375 | 1.375 | 1.375 | |

| Rotation time | s | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | |

| Slice thickness | mm | 2.5 | 3.75 | 3.75 | 3.75 | 3.75 | 3.75 | 3.75 | 3.75 | 3.75 | |

| Reconstruction interval | mm | 1.25 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | |

| Reconstruction algorithm | — | FBPc | FBP | FBP | FBP | FBP | FBP | FBP | FBP | FBP | |

| Reconstruction filter | — | Standard | Standard | Standard | Standard | Standard | Standard | Standard | Standard | Standard | |

| Operating points | Noise index | HU | 21 | 19 | 19 | 18 | 17 | 16 | 15 | 13 | 12 |

| Min tube current | mA | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |

| Max tube currentd | mA | 75 | 82 | 59 | 79 | 112 | 171 | 252 | 284 | 522 | |

| CTDIvol (32-cm phantom) | mGy | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 2.1 | 3.2 | 6.1 | 11.1 | |

| SSDE | mGy | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 2.8 | 4.1 | 5.7 | 10.0 | 16.6 | |

| Effective dose | mSv | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.8 | 3.9 | 6.2 | 10.0 | |

| RI | /1000e | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.8 | |

| Noise in the lungs | HU | 15 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 8 | |

| AUC | — | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 |

WED, water-equivalent diameter.

FOV, field-of-view. The correspondence between scan FOV and bowtie filter is based on the technical reference manual of the LightSpeed VCT system (5116422-100, Rev 6, GE Healthcare, 2006).

FBP, filtered back projection.

The maximum tube current values correspond to the upper limits of the tube currents when TCM is turned on. They also represent the constant tube currents used when TCM is turned off (for example, in situations where patients are uncooperative and accurate patient centering is difficult).

The unit for RI is “cancer incidence cases per 1000 patient exposed.”

3.4. Risk Index Dependencies

Figures 4(c) and 4(d) show the curves of generated for the existing and the optimized protocols, respectively. Because the existing protocols provided similar across patient categories [Fig. 4(a)], they corresponded to slightly higher RI values for younger patients [Fig. 4(c)]. In contrast, the optimized protocols aimed to achieve the same AUC across all patient categories, which implied 10 times more and 4.5 times more RI when comparing the oldest to the youngest patient categories.

4. Discussion

Optimization in images should involve both the benefit and risk associated with a procedure. Prior work on optimization has mostly focused on dose alone or on more rudimentary non task specific quality measures such as noise, or Lickert scales. These have also depended on subjective preference-based measures or relied on very sparse sampling of accuracy–dose space. To the best of our knowledge, this study represented the first assessment of the multidimensional requirements for diagnosis for pediatric CT consisting of accuracy–dose trade-off for color-coded size-specific pediatric CT protocols. We demonstrate that characterizing the continuous dependencies of an objective measure of quality (informed by diagnostic accuracy in the detection of metastatic lung nodules) on radiation dose (informed by organ dose estimates) across a range of pediatric sizes can enable protocol improvement. By establishing a continuous curve, the new method enables the practice of the ALARA (as low as reasonably achievable) principle quantitatively, given a measure of quantification to the quality part of this acronym (“reasonably,” that is maintaining justifiable consistent performance). The framework and the ranges of noise, AUC, and dose values provided in this study can serve as a model for future investigations of CT performance based on quantitative integration of image quality and radiation dose for pediatric protocols.

Our study affirms the obvious expectation that both physical image quality and diagnostic image quality increase with radiation dose; however, it highlights the nonlinear nature of this relationship, echoing the well-known hyperbolic nature of the dose/noise relationship in x-ray imaging. For every unit of dose increase, there is more gain in diagnostic quality at a lower dose. The gradient of this dependency diminishes as the dose increases such that beyond a certain decided threshold dose, a further increase in dose may not be considered to offer a justifiable improvement in the diagnostic performance. This can be used as a basis to both define and move toward optimization. Considering that the relationship between diagnostic performance and dose is highly size- and indication-dependent, it becomes crucially important to ascertain these dependencies so that the thresholds can be properly discerned.

To put the results of this study in perspective, Table 3 compares (32-cm phantom) values from this study with those from other sources. These include median (50th percentile) values from large-scale surveys conducted of pediatric CT practices in the developed and the developing countries. It is clear that the color-coded size-specific protocols in Table 1 represent a relatively low-dose practice. Thus, it may be concluded that the pediatric chest CT images acquired elsewhere have lower noise and hence better physical image quality compared to those acquired with our protocols. This, however, would not be expected to automatically translate to demonstrably higher diagnostic image quality as shown in Fig. 4. Higher dose can be considered a “wasted” dose as the operating points are likely on the plateau portion of the relationship. This highlights the need for base dose optimization not on dose or physical image quality alone but on diagnostic quality.

Table 3.

Comparison of (32-cm phantom) from this study with the corresponding median (50’th percentile) values for chest scans reported in large-scale surveys conducted of pediatric CT practices in western and developing countries.

| Study | Pink | Red | Purple | Yellow | White | Blue | Orange | Green | Black |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This study | 0 to 0.5 (year) | 0.5 to 1.0 (year) | 1.0 to 1.8 (year) | 1.8 to 3.2 year) | 3.2 to 5.2 (year) | 5.2 to 7.3 (year) | 7.3 to 9.2 (year) | 9.2 to 13.5 (year) | 13.5 to 18 (year) |

| 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.6 | |

| UK 2003 (Ref. 32) | 0 to 1 (year) |

5 (year) |

10 (year) |

||||||

| 4.8 | 5 | 6 | |||||||

| Switzerland 2005 (Ref. 33) | 0 to 1 (year) |

1 to 4 (year) |

|||||||

| 4.2 | 6.5 | ||||||||

| 5 to 9 (year) |

|||||||||

| 7.6 | |||||||||

| 10 to 15 (year) |

|||||||||

| 9.6 | |||||||||

| Germany 2005/2006 (Ref. 34) | 0 (year) |

||||||||

| 1.6 | |||||||||

| 0 to 1 (year) |

2 to 5 (year) |

||||||||

| 2.3 | 2.3 | ||||||||

| 6 to 10 (year) |

|||||||||

| 3.2 | |||||||||

| 11 to 15 (year) |

|||||||||

| 5.9 | |||||||||

| France 2007/2008 (Ref. 35) | 1 (year) |

5 (year) |

10 (year) |

||||||

| 2 | 3 | 3.5 | |||||||

| Italian 2010/2011 (Ref. 36) | 1 to 5 (year) |

6 to 10 (year) |

|||||||

| 1.6 | 2.7 | ||||||||

| 11 to 15 (year) |

|||||||||

| 3.7 | |||||||||

| IAEA survey of 40 less resourced countries in Asia, Europe, Latin American, and Africa 2007 to 2009 Germany 2005/2006 (Refs. 37 and 38) | 0 to 1 (year) |

||||||||

| 59.1 | 1 to 5 (year) |

6 to 10 (year) |

|||||||

| 3.4 | 4.9 | ||||||||

| 11 to 15 (year) |

|||||||||

| 5.5 | |||||||||

While the decision of what AUC is adequate is a complex clinical decision, it is clear that dose reduction is possible if the current clinical operating point is well into the “plateau” region of the accuracy–dose curve; in this location, reducing dose has no or minimal effect on diagnostic accuracy. One potential application of this is targeted reduction of dose in practices that use relatively high dose: one can systematically reduce the mA or the associated TCM parameters to a point where the gradient of accuracy–dose dependency reaches a predefine value. Further dose reduction (or enhancement in diagnostic accuracy) may be achieved by adjusting other scan parameters. With the judicious choice of scan FOV, slice thickness, and reconstruction FOV, appreciable dose saving can further be utilized to improve the balance of image quality and radiation risk.

Our application demonstrates that diagnostic image quality is generally higher for younger patients using our protocols, with an AUC differential of 0.22 between newborn and teenage patients. We believe this was a result of two factors. The first is that, all else being equal, image noise increases with increasing patient age/size. Although higher scan parameters (tube current and peak kilovoltage) trended increasingly with age, settings do not fully compensate for the increase in patient size with respect to resultant noise. The second factor was that the reconstruction FOV size generally increases with increasing patient age/size. This leads to reduced nodule diameter as displayed on the workstation. If the chest CT scans are performed for the primary purpose of assessing metastatic disease (e.g., for soft tissue sarcomas), one could argue that dose should be adjusted such that the same diagnostic image quality (AUC) is achieved for all pediatric body sizes. This translates to an 18-fold difference across pediatric categories for an AUC of 0.83. In Table 3, no survey data exhibited such a high ratio. This possibly suggests that the relatively higher diagnostic image quality in younger patients at our institution is also indicative of the practices elsewhere.

This study used effective dose as a basis for optimization. It should be noted that, as the tissue-weighting factors are mean values representing averages over genders and ages, effective dose in principle only applies to reference patients (e.g., average-sized pediatric patients at 0, 1, 5, 10, 15 years of age; 73-kg adult).39 The limited utility of effective dose for medical procedures has been discussed in the literature.40–43 Primarily among those, does not account for some key attributes of radiation burden, age, and gender.22 Though overly simplistic, the scalar aspect of the effective dose and its benchmark against background radiation are of prime convenience for protocol optimization. Other metrics of optimization based on specific organ dose or risk indices using the methodology outlined in this study may also be used. Modality-centric metrics such as CTDI do not linearly relate to patient dose when the patient is varied and, thus, would have limited applicability to optimization tasks.

This study has several limitations. First, due to the retrospective nature of this work, the accuracy–dose curves are only valid for the filtered back projection (FBP) reconstruction algorithm. They do not apply to the recently developed statistical or iterative reconstruction algorithms.44–47 Recent studies in pediatric CT have shown the potential of significant dose saving when using these statistical or iterative reconstruction algorithms.10,48,49 If our study was repeated for the newer generation of reconstruction algorithms, the dose required to achieve the same image quality would likely be lower than what is reported in this paper. However, the methodology applied here can be utilized for other reconstruction techniques. Second, images from the CT scanner investigated in this study do not necessarily represent other CT systems. Some of the newest CT systems employ more sensitive x-ray detectors50 and are equipped with adaptive collimation to reduce overranging distance.51 They likely require lower dose to achieve the same image quality. Third, the accuracy–dose curves published in this study are limited to the task of detecting subtle lung nodules representing pulmonary metastatic diseases, as interpreted by expert pediatric radiologists. For other tasks, such as the detection of iodine-enhanced lesions, the accuracy–dose curves would be different. The clinical operating points would also be different. Finally, our predicted optimized parameters based on our strategy require validation in the clinical routine. Despite the above limitations, the emphasis in this investigation is the model described in this work, exemplified through the clinical task of nodule detection, which can be used as a template in an advanced strategy to analyze the accuracy–dose trade-off for any imaging system, imaging technology, or clinical task. It can further serve as a model for future image quality and radiation dose investigations to define DRLs not based on dose but rather based on image quality.

5. Conclusion

Optimization of CT through quantitative characterization of patient dose and diagnostic quality enables the assessment of the trade-offs between the two as a function of scan parameters for different pediatric patient sizes. The resulting functional dependencies provide a methodology to achieve consistent, task-specific diagnostic accuracy across the broad range of pediatric body sizes. The methodology enables implementation of an optimization targeting a specific dose level irrespective of patient size (with implied differences with respect to resulting image quality), targeting a specific quality level irrespective of patient size (with implied differences with respect to required dose), or targeting an isogradient condition across the sizes. The latter avoids the plateaus where changes in dose have a minimal impact on diagnostic quality, assuring a consistent level of overall performance. The methodology and targeted AUCs can serve as templates and target values for other optimization needs in imaging, serving as an advanced strategy to analyze the accuracy–dose trade-off for other imaging systems, imaging technologies, or clinical tasks.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Yakun Zhang of Duke University for assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Biographies

Ehsan Samei is a professor at Duke University, where he serves as the director of the Duke Medical Physics Graduate Program and the Clinical Imaging Physics Program. His interests include clinically relevant metrology of imaging quality and safety for optimum interpretive and quantitative performance. He strives to bridge the gap between scientific scholarship and clinical practice by meaningful realization of translational research and the actualization of clinical processes that are informed by scientific evidence.

Xiang Li received her MS degree in physics from the University of British Columbia, Canada, and her PhD in medical physics from Duke University. She is a staff physicist at Cleveland Clinic. Her research interests center around radiation dosimetry and image quality in CT. Her clinical responsibilities include CT and magnetic resonance imaging. She also serves as the associate director for the diagnostic medical physics residency at Cleveland Clinic.

Donald P. Frush is John Strohbehn professor and a vice chair of radiology at Duke University. His current research interests are in the field of pediatric radiology and CT technology and application to children. His clinical interests include magnetic resonance imaging, sonography, computer tomography, and sedation. Special interest is in historical material in pediatric radiology.

Appendix: Chest Size Determination

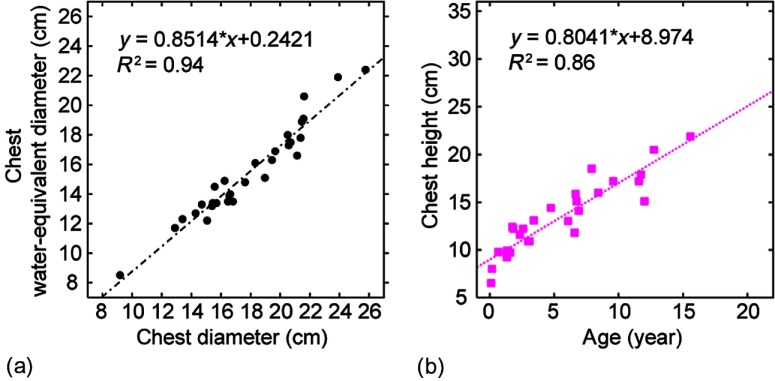

In chest CT, radiation dose and physical image quality depend on chest size. Three metrics of chest size (diameter, water-equivalent diameter, and height) were determined for each patient category to facilitate dose and image quality assessment.

Chest diameter was calculated as , where and denote the anteroposterior and transverse thicknesses of the chest, respectively. They have been measured as functions of pediatric age by Kleinman et al.52 In this study, the results of the linear regression analysis reported by Kleinman et al. were used for patients older than two years of age (i.e., the last six patient categories). For patients younger than two years of age (i.e., the first three patient categories), the original data of Kleinman et al. were fitted to a power-law function. The results can be summarized as

| (9) |

where and are in the unit of cm, and age is in the unit of year. For each patient category, the median age was used to calculate and and derive chest diameter (Tables 1 and 3). was used to calculate size-specific effective dose [Eq. (8)].

An earlier study25 showed that water-equivalent diameter of the chest determined from nonlung chest area can be used to estimate noise in the lung regions of a chest CT image. For each patient category, was calculated from using the linear relationship between the two [Fig. 7(a)]. The linear relationship was established based on measurements made from the chest CT images of 30 pediatric patients (median age, 4 years old; age range, 0 to 18 years old; median weight, 17 kg; weight range, 2 to 52 kg) included in an earlier ROC observer study.18

Fig. 7.

(a) Chest water-equivalent diameter as a function of chest diameter. (b) Chest height as a function of age.

The chest height of a patient was defined as the distance from lung apex to lung base. Chest height was measured from the scout images of the same 30 pediatric patients and was correlated with age using linear regression analysis [Fig. 7(b)]. The result of the analysis was then used to calculate chest height for each patient category based on median age.

Disclosures

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

References

- 1.Donnelly L. F., et al. , “Minimizing radiation dose for pediatric body applications of single-detector helical CT: strategies at a large Children’s Hospital,” Am. J. Roentgenol. 176(2), 303–306 (2001). 10.2214/ajr.176.2.1760303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paterson A., Frush D. P., Donnelly L. F., “Helical CT of the body: are settings adjusted for pediatric patients?” Am. J. Roentgenol. 176(2), 297–301 (2001). 10.2214/ajr.176.2.1760297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frush D. P., et al. , “Improved pediatric multidetector body CT using a size-based color-coded format,” Am. J. Roentgenol. 178(3), 721–726 (2002). 10.2214/ajr.178.3.1780721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boone J. M., et al. , “Dose reduction in pediatric CT: a rational approach,” Radiology 228(2), 352–360 (2003). 10.1148/radiol.2282020471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cody D. D., et al. , “Strategies for formulating appropriate MDCT techniques when imaging the chest, abdomen, and pelvis in pediatric patients,” Am. J. Roentgenol. 182(4), 849–859 (2004). 10.2214/ajr.182.4.1820849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larson D. B., et al. , “System for verifiable CT radiation dose optimization based on image quality. Part I. Optimization model,” Radiology 269(1), 167–176 (2013). 10.1148/radiol.13122320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larson D. B., et al. , “System for verifiable CT radiation dose optimization based on image quality. Part II. Process control system,” Radiology 269(1), 177–185 (2013). 10.1148/radiol.13122321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu L., et al. , “Automatic selection of tube potential for radiation dose reduction in CT: a general strategy,” Med. Phys. 37(1), 234–243 (2010). 10.1118/1.3264614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh S., et al. , “Dose reduction and compliance with pediatric CT protocols adapted to patient size, clinical indication, and number of prior studies,” Radiology 252(1), 200–208 (2009). 10.1148/radiol.2521081554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh S., et al. , “Radiation dose reduction with hybrid iterative reconstruction for pediatric CT,” Radiology 263(2), 537–546 (2012). 10.1148/radiol.12110268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strauss K. J., “Developing patient-specific dose protocols for a CT scanner and exam using diagnostic reference levels,” Pediatr. Radiol. 44(Suppl 3), 479–488 (2014). 10.1007/s00247-014-3088-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larson D. B., “Optimizing CT radiation dose based on patient size and image quality: the size-specific dose estimate method,” Pediatr. Radiol. 44(Suppl 3), 501–505 (2014). 10.1007/s00247-014-3077-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCarville M. B., et al. , “Distinguishing benign from malignant pulmonary nodules with helical chest CT in children with malignant solid tumors,” Radiology 239(2), 514–520 (2006). 10.1148/radiol.2392050631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Absalon M. J., et al. , “Pulmonary nodules discovered during the initial evaluation of pediatric patients with bone and soft-tissue sarcoma,” Pediatr. Blood Cancer 50(6), 1147–1153 (2008). 10.1002/(ISSN)1545-5017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silva C. T., et al. , “CT characteristics of lung nodules present at diagnosis of extrapulmonary malignancy in children,” Am. J. Roentgenol. 194(3), 772–778 (2010). 10.2214/AJR.09.2490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Craft A. W., “Childhood cancer—mainly curable so where next?” Acta Paediatr. 89(4), 386–392 (2000). 10.1080/080352500750028041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.European Society of Radiology, “ESR statement on radiation protection: globalisation, personalised medicine and safety (the GPS approach),” Insights Imaging 4(6), 737–739 (2013). 10.1007/s13244-013-0287-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li X., et al. , “Lung nodule detection in pediatric chest CT: quantitative relationship between image quality and radiologist performance,” Med. Phys. 38(5), 2609–2618 (2011). 10.1118/1.3582975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li X., et al. , “Patient-specific radiation dose and cancer risk for pediatric chest CT,” Radiology 259(3), 862–874 (2011). 10.1148/radiol.11101900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.AAPM, “Size-specific dose estimates (SSDE) for pediatric and adult CT examinations,” AAPM Report No. 204, American Association of Physicists in Medicine, College Park, Maryland: (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 21.ICRP , “The 2007 recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. ICRP publication 103,” Ann. ICRP 37(2–4), 1–332 (2007). 10.1016/j.icrp.2007.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samei E., Tian X. Y., Frush D., “Radiation risk index for pediatric CT: a patient-derived metric,” Pediatr. Radiol., in press (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCollough C. H., et al. , “Achieving routine submillisievert CT scanning: report from the summit on management of radiation dose in CT,” Radiology 264(2), 567–580 (2012). 10.1148/radiol.12112265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Research Council (U.S.). Committee to Assess Health Risks from Exposure to Low Level of Ionizing Radiation, Health Risks from Exposure to Low Levels of Ionizing Radiation: BEIR VII Phase 2, National Academies Press, Washington, DC: (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X., Samei E., “Comparison of patient size-based methods for estimating quantum noise in CT images of the lung,” Med. Phys. 36(2), 541–546 (2009). 10.1118/1.3058482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frush D. F., “MDCT in children: scan techniques and contrast issues,” in MDCT: from Protocols to Practice, Kalra M. K., Saini S., Rubin G. D., Eds., pp. 333–354, Springer, Milan, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 27.ICRU, “Photon, electron, proton and neutron interaction data for body tissues,” Report 46, International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements, Bethesda, Maryland: (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li X., et al. , “Patient-specific radiation dose and cancer risk estimation in CT: Part I. Development and validation of a Monte Carlo program,” Med. Phys. 38(1), 397–407 (2011). 10.1118/1.3515839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li X., et al. , “Effects of protocol and obesity on dose conversion factors in adult body CT,” Med. Phys. 39(11), 6550–6571 (2012). 10.1118/1.4754584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalender W. A., Computed Tomography: Fundamentals, System Technology, Image Quality, Applications, 2nd ed., Publicis Corporate Publishing, Erlangen, Germany: (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Solomon J. B., Li X., Samei E., “Relating noise to image quality indicators in CT examinations with tube current modulation,” Am. J. Roentgenol. 200(3), 592–600 (2013). 10.2214/AJR.12.8580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shrimpton P. C., et al. , “National survey of doses from CT in the UK: 2003,” Br. J. Radiol. 79(948), 968–980 (2006). 10.1259/bjr/93277434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verdun F. R., et al. , “CT radiation dose in children: a survey to establish age-based diagnostic reference levels in Switzerland,” Eur. Radiol. 18(9), 1980–1986 (2008). 10.1007/s00330-008-0963-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galanski M., Nagal H. D., Stamm G., “Pediatric CT exposure practice in the federal Republic of Germany. Results of a nationwide survey in 2005/6. Medizinishe Hochschule Hannover,” 2007, http://www.mh-hannover.de/fileadmin/kliniken/diagnostische_radiologie/download/Report_German_Paed-CT-Survey_2005_06.pdf (7 January 2015).

- 35.Brisse H. J., Aubert B., “CT exposure from pediatric MDCT: results from the 2007–2008 SFIPP/ISRN survey,” J. Radiol. 90(2), 207–215 (2009). 10.1016/S0221-0363(09)72471-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Granata C., et al. , “Radiation dose from multidetector CT studies in children: results from the first Italian nationwide survey,” Pediatr. Radiol. 45(5), 695–705 (2015). 10.1007/s00247-014-3201-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vassileva J., et al. , “IAEA survey of pediatric CT practice in 40 countries in Asia, Europe, Latin America, and Africa: Part 1, frequency and appropriateness,” Am. J. Roentgenol. 198(5), 1021–1031 (2012). 10.2214/AJR.11.7273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vassileva J., et al. , “IAEA survey of paediatric computed tomography practice in 40 countries in Asia, Europe, Latin America, and Africa: procedures and protocols,” Eur. Radiol. 23(3), 623–631 (2013). 10.1007/s00330-012-2639-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.ICRP, The 2007 Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection, ICRP Publication 103, International Commission on Radiological Protection, Essen, Germany: (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bankier A. A., Kressel H. Y., “Through the looking glass revisited: the need for more meaning and less drama in the reporting of dose and dose reduction in CT,” Radiology 265(1), 4–8 (2012). 10.1148/radiol.12121145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Borras C., Huda W., Orton C. G., “Point/counterpoint. The use of effective dose for medical procedures is inappropriate,” Med. Phys. 37(7), 3497–3500 (2010). 10.1118/1.3377778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brenner D. J., “Effective dose: a flawed concept that could and should be replaced,” Br. J. Radiol. 81(967), 521–523 (2008). 10.1259/bjr/22942198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin C. J., “The application of effective dose to medical exposures,” Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 128(1), 1–4 (2008). 10.1093/rpd/ncm425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prakash P., et al. , “Radiation dose reduction with chest computed tomography using adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction technique: initial experience,” J. Comput. Assisted Tomogr. 34(1), 40–45 (2010). 10.1097/RCT.0b013e3181b26c67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang R., et al. , “Improved image quality in dual-energy abdominal CT: comparison of iterative reconstruction in image space and filtered back projection reconstruction,” Am. J. Roentgenol. 199(2), 402–406 (2012). 10.2214/AJR.11.7159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baker M. E., et al. , “Contrast-to-noise ratio and low-contrast object resolution on full- and low-dose MDCT: SAFIRE versus filtered back projection in a low-contrast object phantom and in the liver,” Am. J. Roentgenol. 199(1), 8–18 (2012). 10.2214/AJR.11.7421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Husarik D. B., et al. , “Radiation dose reduction in abdominal computed tomography during the late hepatic arterial phase using a model-based iterative reconstruction algorithm: how low can we go?” Invest. Radiol. 47(8), 468–474 (2012). 10.1097/RLI.0b013e318251eafd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gay F., et al. , “Dose reduction with adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction for paediatric CT: phantom study and clinical experience on chest and abdomen CT,” Eur. Radiol. 24(1), 102–111 (2014). 10.1007/s00330-013-2982-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith E. A., et al. , “Model-based iterative reconstruction: effect on patient radiation dose and image quality in pediatric body CT,” Radiology 270(2), 526–534 (2014). 10.1148/radiol.13130362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yanagawa M., et al. , “Multidetector CT of the lung: image quality with garnet-based detectors,” Radiology 255(3), 944–954 (2010). 10.1148/radiol.10091010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deak P. D., et al. , “Effects of adaptive section collimation on patient radiation dose in multisection spiral CT,” Radiology 252(1), 140–147 (2009). 10.1148/radiol.2522081845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kleinman P. L., et al. , “Patient size measured on CT images as a function of age at a tertiary care children’s hospital,” Am. J. Roentgenol. 194(6), 1611–1619 (2010). 10.2214/AJR.09.3771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]