Abstract

This article highlights the emerging therapeutic potential of specific epigenetic modulators as promising antiepileptogenic or disease-modifying agents for curing epilepsy. Currently, there is an unmet need for antiepileptogenic agents that truly prevent the development of epilepsy in people at risk. There is strong evidence that epigenetic signaling, which exerts high fidelity regulation of gene expression, plays a crucial role in the pathophysiology of epileptogenesis and chronic epilepsy. These modifications are not hard-wired into the genome and are constantly reprogrammed by environmental influences. The potential epigenetic mechanisms, including histone modifications, DNA methylation, microRNA-based transcriptional control, and bromodomain reading activity, can drastically alter the neuronal gene expression profile by exerting their summative effects in a coordinated fashion. Such an epigenetic intervention appears more rational strategy for preventing epilepsy because it targets the primary pathway that initially triggers the numerous downstream cellular and molecular events mediating epileptogenesis. Among currently approved epigenetic drugs, the majority are anticancer drugs with well-established profiles in clinical trials and practice. Evidence from preclinical studies supports the premise that these drugs may be applied to a wide range of brain disorders. Targeting histone deacetylation by inhibiting histone deacetylase enzymes appears to be one promising epigenetic therapy since certain inhibitors have been shown to prevent epileptogenesis in animal models. However, developing neuronal specific epigenetic modulators requires rational, pathophysiology-based optimization to efficiently intercept the upstream pathways in epileptogenesis. Overall, epigenetic agents have been well positioned as new frontier tools towards the national goal of curing epilepsy.

Keywords: Epigenetics, epileptogenesis, histone modification, DNA methylation, miRNA, epilepsy

1. Molecular cascades of epileptogenesis

The term ‘epileptogenesis’ is used to describe the complex plastic changes in the brain that convert a normal brain into a brain debilitated by recurrent seizure activity (Pitkänen et al., 2009; Reddy, 2013). The progression of epileptogenesis can be divided into three phases: the initial injury phase, the latent phase, and the chronic phase. During the initial injury phase, an insult such as stroke, traumatic brain injury (TBI), brain infection, or exposure to a neurotoxin can activate a host of signaling cascades, triggering the epileptogenic pathway. These signals induce changes that lead to neuroinflammation, oxidation, apoptosis, synaptic plasticity, and functional alterations in the neuronal and neurovascular unit (Pitkänen et al., 2009). The resulting physiological responses alter gene expression in neuronal ensembles by modifying the epigenetic landscape. Next, a dynamic process ensues leading to the rearrangement of synaptic circuitry, neuronal damage, neurogenesis, and synchronic hyperexcitability. These dynamic changes are characteristic of the latent phase, characterized as the most unpredictable phase because it can last several weeks, months, or even years without any clinical symptoms. These changes eventually manifest in spontaneous seizure activity, marking onset of the chronic phase. Intervening in these underlying molecular cascades of epileptogenesis may lead to discoveries and eventual breakthroughs in the development of a cure for epilepsy.

Currently, there is an unmet need for antiepileptogenic agents that truly prevent the development of epilepsy or disease-modifying agents that delay the appearance or severity of epileptic seizures in people at risk (Jacobs et al., 2009). Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) are the mainstay treatment for epileptic seizures, but about one-third of people with epilepsy show intractable seizures that are resistant to even the best drug therapy (Kwan and Sander, 2004; Löscher and Schmidt, 2011). Moreover, many clinical trials showed a lack of antiepileptogenic efficacy of AEDs in patients at high risk for developing epilepsy (Temkin, 2001; 2009). Some AEDs on the market may be adequate in treating an acute seizure occurrence but have no effect on the underlying cause of the seizure, leading to prolonged and unpredictable seizure activity that can further debilitate the brain. Thus, conventional AEDs do not exert a true antiepileptogenic effect, partly because the mechanisms behind anticonvulsant and antiepileptogenic activity are instinctively distinct in the various forms of acquired epilepsy in humans. This is explained by the fact that epilepsy is a spectrum disorder that varies in origin and disease course (Hesdorffer et al., 2013). The heterogenic nature of epilepsy disorders represents both challenges and opportunities for epilepsy research and drug development.

Understanding the causes and halting the progression of various forms of epilepsy are identified as top priorities in the 2014 NIH/NINDS Benchmarks for Epilepsy Research. To fill the gaps in epilepsy research, many labs have been pioneering investigations on the pathophysiology of the mechanisms underlying epileptogenesis. Pinpointing specific targets within the early phases of epileptogenesis may lead to breakthroughs in the development of novel therapies for epilepsy. It is well accepted that epigenetics, neuroinflammation, and neurodegeneration are the critical players underlying the progression of epileptogenesis (Pitkanen et al., 2009; Reddy, 2013; Gibson et al., 2014). However, there are crucial gaps in knowledge on the fundamental mechanisms of epigenetics and neuronal network pathways that are responsible for the spatial and temporal events ultimately leading to epilepsy. Therefore, a mechanism-based, rational approach through multidisciplinary research is essential for advancing the national goal of curing epilepsy within the next decade.

The central premise of ‘epigenetic therapy’ is dependent on the potential reversibility of the epigenetic profile, independent of the non-reversible genome. Signaling pathways that regulate epigenetic enzymes are the fundamental targets of epigenetic therapies. Among currently approved epigenetic drugs, the majority are anti-cancer drugs with well-established profiles in clinical trials and practice (Table 1). Thus, the potential side effects and toxic effects of these drugs have been thoroughly explored and reported. Pre-clinical evidence supports that these drugs may be applied to a wide range of central nervous system disorders. In this article, we highlight the emerging therapeutic potential of a growing collection of epigenetic modulators spanning multiple classes as promising antiepileptogenic or disease-modifying agents for epilepsy.

Table 1.

Epigenetic drugs approved for clinical use and in experimental investigation.

| Class | Epigenetic Target | Agent Name | Developmental Stage | Therapeutic Target |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HDAC inhibitors | HDAC I & II | Valproic acid (VPA) Vorinostat (SAHA) Belinostat (PXD101) Panobinostat (LBH589) Abexinostat (PCI24781) CI994 |

Approved (1986) Approved (2006) Approved (2014) Approved (2015) Phase II Phase II |

Epilepsy T-cell lymphoma T-cell lymphoma Multiple myeloma B-cell lymphoma Multiple myeloma |

|

| ||||

| HDAC I only | Romidepsin (Depsipeptid) Entinostat (MS275) Mocetinostat (MGCD0103) Givinostat (ITF2357) |

Approved (2009) Phase-II Phase-II Phase-II |

T-cell lymphoma Hodgkin’s lymphoma Hodgkin’s lymphoma Hodgkin’s lymphoma |

|

|

| ||||

| DNMT inhibitors | DNMTs | 5-Azacytidin (Azacitidine) 5-Aza-2-deoxycitidin (Decitabine) Zebularine MG98 |

Approved (2004) Approved (2006) Preclinical |

Myelodysplastic syndrome Myelodysplastic syndrome & leukemia Various cancers |

|

| ||||

| DNMT I only | MG98 | Phase II | Renal cell carcinoma | |

|

| ||||

| BET inhibitors | BRDs 2,3,4 | JQ1 iBET |

Preclinical Preclinical |

Various cancers Leukemia & epilepsy |

2. Fundamentals of epigenetic mechanisms in epilepsy

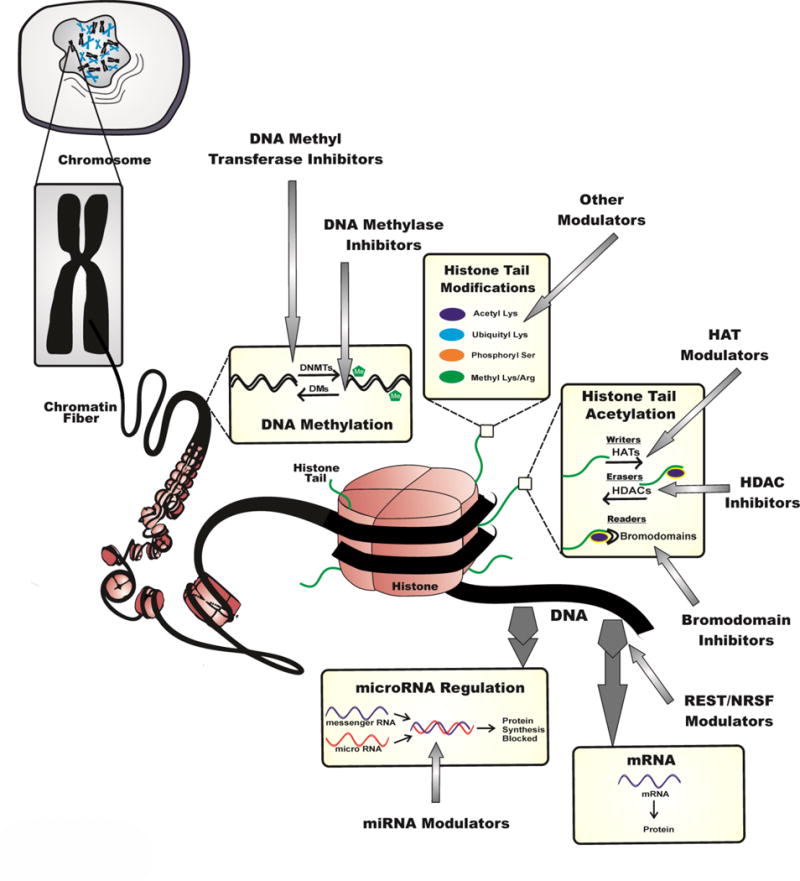

Chromatin and epigenetic modifications play a crucial role in the regulation of gene expression underlying several nervous system disorders such as epilepsy (Fig. 1). Epigenetics refers to specific changes in gene expression that are not hard-wired into the genome and are constantly being reprogrammed by environmental factors. The epigenetic landscape is maintained by epigenetic enzymes called ‘writers’ and ‘erasers’, which can either encode epigenetic marks or remove them, respectively. These marks are crucial for normal physiological functions during embryogenesis, brain development, and in the day-to-day regulation of gene expression (Hwang et al., 2013). Furthermore, a class of ‘readers,’ the bromodomain and extra-terminal domains (BETs) recognize modifications on histone tails and modulate appropriate gene expression of these epigenetic instructions. This incredibly vital, yet complex process is tightly regulated and consequently any dysregulation in such high-fidelity, upstream signaling may have devastating effects leading to the onset of diseases such as epilepsy.

Fig. 1. Targeted approaches to discovery of epigenetic inhibitors in epilepsy.

This schematic representation illustrates the potential epigenetic mechanisms, including DNA methylation, histone alterations, RNA-based transcriptional control, and bro domain reading activity which can alter the cellular gene expression profile and thus promote inhibition of epileptogenesis progression.

The multiple classes of epigenetic modifications include histone alterations, DNA methylation, microRNA-based transcriptional control, and bromodomain reading activity (Fig. 1). These epigenetic pathways work in a highly regulated fashion to establish various levels of gene expression from an individual genome. In other words, through epigenetic reprogramming, identical genetic sequences are directed to be differentially expressed across multiple cells in the context of gene function as per the external milieu.

Epigenetic programming influences gene expression through highly regulated gene activation and gene silencing activity (Henshall and Kobow, 2015). The epigenome encompasses the physical changes in gene-supporting proteins such as histones which are responsible for maintaining the tertiary and quaternary structure of DNA (Graff et al., 2011). Inherently, altering these higher-order structures of DNA leads to the activation or silencing of specific genes. Dysregulation of these essential epigenetic signaling has been associated with various syndromes or disease states such as epileptic syndromes, Fragile X-syndrome, Rett syndrome and autism spectrum disorder (Table 2) (Kobow and Blumcke, 2014). Recently, many studies have reported that epigenetic processes such as histone modification, DNA methylation, and microRNA expression are significantly altered in the epigenome of an epileptic brain (see Table 3–6) (Graff et al., 2011; Sweatt, 2013; Dębski et al., 2016).

Table 2.

List of epigenetic factors and their genetic syndromes.

| Gene | Epigenetic role in the brain | Syndrome |

|---|---|---|

| ARX | Histone methylation and chromatic remodeling; neuronal role include maintenance of specific neuronal subtypes in the cortex | Infantile epileptic encephalopathy-1/West syndrome; X-linked lissencephaly; X-linked mental retardation |

|

| ||

| CHD2 | Chromatic remodeler; neuronal role unclear | Epileptic encephalopathy, childhood-onset |

|

| ||

| CDKL5 | DNMT1 phosphorylation, MeCP2-binding protein; neuronal role unclear | Early infantile epileptic encephalopathy-2; atypical Rett syndrome; Angelman syndrome mental retardation, autosomal dominant-1; 2q23.1 microdeletion syndrome with seizures |

|

| ||

| MBD5 | Methyl DNA-binding protein; Neurogenesis, survival, LTP and memory function | |

|

| ||

| PRICKLE1 | Nuclear receptor; necessary for nuclear localization of REST; involved in neuronal axon guidance | Progressive myoclonic epilepsy-1B |

|

| ||

| ATRX | Chromatic remodeler (SWI/SNF family); neuronal role include neurogenesis. | Alpha-thalassemia/mental retardation |

|

| ||

| EHMT1 | Histone methyltransferases; neuronal role include learning and memory | Kleefstra syndrome |

| FMR1 | RNA-binding protein in miRNA pathway; neuronal role include learning and memory | Fragile X-syndrome |

|

| ||

| KDM5C | Histone demethylase; neuronal role unclear | X-linked mental retardation |

| MECP2 | Methyl DNA-binding protein; neuronal role include LTP and memory function | Rett syndrome; non-syndromic X-linked mental retardation; Angelman syndrome; Autism Sotos syndrome; Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome |

| NSD1 | Histone methyltransferases; neuronal role unclear | |

| SMARCA4 | Chromatin remodeler (SWI/SNF family); neuronal role include neurogenesis | Mental retardation, autosomal dominant-16 |

Table 3.

Summary of histone modification studies in epilepsy models.

| Model | Epigenetic Changes | Clinical Implications | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| SE (Pilo, rat) | Reduced H4 acetylation at GluR2/Gria2; Increased H4 acetylation at BDNF | Seizure susceptibility | Huang et al. (2002) |

|

| |||

| SE (Pilo & KA, mice) | Increased H3 phosphorylation; Correlated to c-fos and c-jun genes | Seizure susceptibility | Crosio et al. (2003) |

|

| |||

| SE (KA, mice) | Increased H4 acetylation and H3 phosphorylation | Seizure susceptibility | Sng et al. (2006) |

|

| |||

| EC (rat) | Reduced H4 acetylation after seizures and Increased H4 acetylation at BDNF and c-fos | Seizure susceptibility | Tsankova et al. (2004) |

|

| |||

| TLE (Pilo, rat) | Increased HDAC2 | Epilepsy | Huang et al. (2012) |

|

| |||

| PTZ (mouse) | Increased seizure threshold with VPA but not TSA | Seizure susceptibility | Hoffmann et al. (2008) |

|

| |||

| HDAC4 KO | Increased seizures | Epileptogenesis | Rajan et al. (2009) |

|

| |||

| TBI (CCI, rat) | Reduced H3 acetylation | Post-traumatic epilepsy | Gao et al. (2006) |

|

| |||

| TBI (CCI, mice) | HDACi enhances learning/memory | Post-traumatic epilepsy | Dash et al. (2009) |

|

| |||

| TBI (CCI, rat) | Increased H3 and H4 acetylation with VPA but not SAHA | Post-traumatic epilepsy | Dash et al (2010) |

|

| |||

| TBI (LFP, rat) | Reduced H3 acetylation; effects blocked by HDACi | Post-traumatic epilepsy | Zhang et al. (2008) |

|

| |||

| TBI (Wt, mice) | Reduced H3 acetylation; effects blocked by HDACi | Post-traumatic epilepsy | Shein et al. (2009) |

Abbreviations: SE, status epilepticus; KA, kainic acid; Pilo, pilocarpine; TLE, temporal lobe epilepsy; TBI, traumatic brain injury; Wt, weight-drop; CCI, controlled cortical impact; KO, knockout; HDACi, histone deacetylase inhibitor; HATi, histone acetyl transferase inhibitor; PTZ, pentylenetetrazol

Table 6.

Summary of studies investigating epigenetic agents in epileptogenesis models.

| Agent name | Epigenetic effect | Model | Main Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VPA | HDAC I & II inhibition | SE (KA, rat) | Inhibited seizure induced neurogenesis in hippocampus | Jessberger et al. (2007) |

| SE (Ptz, mice) | Increased seizure threshold | Hoffmann et al. (2008) | ||

| IBO injection (rat) | Increased H3 acetylation and protection of cholinergic and GABAergic neurons | Eleuteri et al. (2009) | ||

|

| ||||

| TSA | HDAC I & II inhibition | SE (Pilo, rat) | Prevented reduced GluR2 expression | Huang et al. (2002) |

| SE (KA, mice) | Histone hyperacetylation | Sng et al. (2005) | ||

| SE (KA, rat) | Prevented reduced GluR2 expression | Jessberger et al. (2007) | ||

| SE (Ptz, mice) | No anticonvulsive effects | Hoffmann et al. (2008) | ||

|

| ||||

| Sodium Butyrate | HDAC I & II inhibition | EC (mice) | Increased H3 and H4 acetylation and improved anticonvulsant activity of MK-801 | Deutsch et al. (2008) |

| EC (mice) | Increased seizure threshold and reduced seizure severity | Reddy et al. (unpublished) | ||

|

| ||||

| Zebularine | DNMT inhibition | MeCP2 KO (mice) | Rett Syndrome, deficits in spontaneous synaptic transmission | Nelson et al. (2008) |

Abbreviations: SE, status epilepticus; KA, kainic acid; Pilo, pilocarpine; EC, electroconvulsive; VPA, valproic acid; TSA, trichostatin A; IBO, ibotenic acid; GluR2, glutamate receptor 2; PTZ, pentylenetetrazol; KO, knockout

Although epigenetic signaling mechanisms play a critical role in epileptogenesis triggered by TBI, stroke, or other acquired risk factors, there is little effort for drug discovery to target specific epigenetic mechanisms. However, there is a strong rationale that makes epigenetic enzymes a compelling target of investigation for their role in the progression of epileptogenesis. The translational potential of treatments based on epigenetic pathways in epilepsy and epileptogenic models still needs further investigation to uncover therapeutic potential. The field of epigenetic modulation is ripe with the possibility of novel drug therapies that target epigenetic enzymes by inhibiting or modulating their activity. In the next few sections, we reviewed the underlying epigenetic dysfunction in epilepsy and discuss the premise of altering or inhibiting select epigenetic enzymes for the effective interruption of epileptogenesis and chronic epilepsy.

3. Targeting histones and their role in epileptogenesis

The human genome is the complete set of nucleic acid sequence encoded as DNA within the 23 chromosome pairs. There are an estimated 20,000 protein-coding genes. DNA contained in a human nucleosome is tightly coiled around a histone octamer. The nucleosome is the fundamental unit of chromatin and is composed of H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 histone pairs, linked by the H1 subunit. The long N-terminal tails of histones contain numerous sites for post-translational modifications. Epigenetic marks are added and removed to histone tails through the complex action of enzymes referred to as ‘writers’ and ‘erasers.’ The most common modifications at the histone tail sites include lysine ubiquination, acetylation and methylation, arginine methylation, and serine phosphorylation. These modifications are cumulatively involved in generating a ‘histone code’ that influences gene expression. Several approaches such as mass spectrometry and protein chemistry have been used to map the histone code (Nicklay et al., 2009). Epigenetic alterations occurring at the histone tail can modulate histone–DNA interactions and significantly influence chromatin structure, thereby modifying the accessibility of transcriptional regulators to DNA-binding elements. Therefore, a histone modification at one site on the histone tail may influence modifications at other sites and may also affect DNA methylation (Miao and Natarajan, 2005). Thus, histone modifications are interrelated and exert changes to the overall epigenetic profile.

The primary histone modification associated with epilepsy and other central nervous system (CNS) disorders is lysine acetylation at the histone tail. Histone acetylation is catalyzed by histone acetyltransferases (HATs), and histone deacetylation is carried out by histone deacetylases (HDACs). As a result of these two opposing epigenetic modifications, chromatin is known to exist in two higher-order structures. Euchromatin refers to the loosely packaged and open form that is transcriptionally active whereas heterochromatin refers to the highly compact and transcriptionally inactive form (Kouzarides, 2007). The interplay between these opposing epigenetic modifications has major implications not only on normal physiology and development of the body, but also on transcriptional activity associated with various central nervous system disorders.

HDACs play a crucial role in repressing gene transcription by condensing chromatin structure. This is achieved through the subsequent removal of acetyl groups (−COCH3) from the lysine residue on amino terminals of histone tails. Removal of the acetyl group increases the positive charge of the histone and confers a more compact state, characteristic of gene repression. HDACs can also remove acetyl moieties from transcription factors, thereby further suppressing gene activity (Morris et al., 2010). There a four classes of HDAC enzymes within the HDAC superfamily, with classes I and II being the most relevant to epilepsy because they have the highest expression seen in the brain (Gray and Ekstrom, 2001). It is important to note that HDAC enzymes do not interact directly with DNA, but rather work collectively with transcription factors to alter the activity of DNA at target genes (Carey and La Thangue, 2006). Specific transcription factors such as the repressor element 1-silencing transcription factor (REST) will be discussed in greater detail later.

In contrast, HATs acetylate lysine residues conferring a less compact, relaxed conformation that increases transcriptional activity. HAT enzymes can either have wide-spread activity resulting in a global up-regulation of gene transcription or induce highly specific local changes on histones cores of specific gene promotors (Selvi et al., 2010). Appropriate HAT activity is crucial for neurogenesis, memory formation, and synaptogenesis. Dysregulation of these essential enzymes has been associated with various disease states such as autism spectrum disorder, Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, cancer, and intellectual disabilities (Hwang et al., 2013).

Cognitive decline is characteristic of several neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and epilepsy. Histone acetylation catalyzed by HATs is one of the major players implicated in neuroplasticity and memory. One of the first studies that discovered this link reported increased H3 acetylation in the CA1 region of the hippocampus during long-term memory consolidation (Levenson et al., 2004). Pinpointing the exact HDACs that play a key role in memory consolidation is critical for targeted pharmacotherapy. The role of HDAC2 and HDAC5 in memory formation and consolidation has been well reported. HDAC2 is believed to repress memory consolidation and synaptic plasticity by inhibiting acetylation (Guan et al., 2009). This was confirmed in Hdac2 knockout mice that showed enhanced associative learning with the loss of HDAC2 (Morris et al., 2013). Overexpression of HDAC2 in the hippocampus of mice had negative effects on long-term memory consolidation (Morris et al., 2013). In contrast, HDAC5 is critical for memory formation. In Hdac5 knockout mice, the loss of HDAC5 impaired memory function and had negative effects on long-term memory (Agis-Balboa et al., 2013).

It is uncontested that epigenetic therapies should be aimed at particular enzyme isoforms that are involved in highly specific brain functions. However, a specific enzyme isoform may not be exclusive to only a certain neuronal function. For example, HDAC6 which is a class II HDAC, is involved in the regulatory functions of the microtubule network and effectively impairs axonal transport (d’Ydewalle et al., 2012). Conversely, HDAC6 plays a fundamental neuroprotective role by stimulating autophagy of damaged proteins (Boyault et al., 2007). As a result of these contrasting regulatory functions, a class II HDAC inhibitor that acts on HDAC6 will yield both contradictory neuroprotective and neurodegenerative effects on the brain. Therefore, uncovering the complex web of both histone and non-histone targets of HDAC inhibitors in the brain may be just as, if not more important, than focusing on targeting specific enzyme isoforms of HDACs.

3.1. Role of histone modifications in epileptogenesis

Histone modifications play a key role in epilepsy. Table 3 summarizes a list of studies that elucidate how histone modification patterns are altered following seizure activity. In pilocarpine and kainic acid induced seizures, significant epigenetic remodeling was reported. Kainic acid triggers seizure activity in the hippocampus by binding kainate receptors that are involved in excitatory neurotransmission (Kew and Kemp, 2005). Kainic acid triggers methylation (gene repression) of the Gria2 gene encoding for the ionotropic glutamate receptor AMPA (GluR2). The Gria2 gene encodes for GluR2, an AMPA (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid) receptor subunit that restricts calcium permeability. Because the GluR2 subunit is responsible for rendering AMPA receptors impermeable to calcium, the downregulation of the Gria2 gene and the subsequent repression of GluR2 are both associated with initiating epileptogenesis and enhancing neuronal hyperexcitability (Tanaka et al., 2000).

In both pilocarpine and kainic acid induced seizures, increased H3 phosphorylation was reported across multiple studies (Crosio et al., 2003; Sng et al., 2006). H3 phosphorylation is believed to promote the underlying mechanism that induces acetylation of histone tails. Furthermore, increased H4 acetylation (correlated with active transcription) was reported in pilocarpine, kainic acid, and electroconvulsive-induced seizure models. Increased H4 acetylation was linked to up-regulated BDNF and c-fos/c-jun genes (Huang et al., 2002; Sng et al., 2006; Tsankova et al., 2004). C-fos and c-jun genes are activated in response to extraneous stimuli to promote cellular growth, differentiation, and neuronal survival (Sng et al., 2006). In contrast, reduced H4 acetylation was reported at GluR2 and Gria2 gene loci after seizure activity (Huang et al., 2002; Tsankova et al., 2004). This may explain why HDAC inhibitors such as trichostatin A that block deacetylation at the Gria2 gene locus have been postulated to have a neuroprotective effect (Huang et al., 2002). Histone modifications in TBI models also showed significant alterations in histone acetylation patterns. In both controlled cortical impact (CCI) and weight-drop models of TBI, a reduction in H3 acetylation was reported, with effects reversed by HDAC inhibition (Gao et al., 2006; Dash et al., 2009, 2010; Zhang et al., 2008; Shein et al., 2009).

The complex epigenetic landscape has demonstrated flexibility and reversibility in a range of neurological disorders. For example, adverse early life care implies significant changes to the epigenetic landscape that affects life-long phenotypes involving behavior, anxiety, stress, and hyperactivity (Weaver et al., 2004). It is possible to reverse the adverse phenotypes by administration of the HDAC inhibitor trichostatin A (Weaver et al., 2006). The inhibitor has also showed promising results in reversing cancer phenotypes in erythroleukemia cells (Yoshida et al., 1987; Futamura et al., 1995). Moreover, administration of the HDAC inhibitor sodium butyrate has been shown to restore learning and synaptogenesis in a mouse model of learning impairment (Fischer et al., 2007).

These examples indicate that histone acetylation plays a key role in memory formation and may have therapeutic potential in cognitive decline and neurodegenerative diseases. Therefore, epigenetic therapies that include HDAC enzyme inhibitors such as valproic acid, sodium butyrate, trichostatin A may be well-suited to alter gene expression profiles and inhibit epileptogenesis (Mehler, 2010a). While uncovering the therapeutic potential of HDAC inhibitors, it is also important to consider the physiological role of HDAC enzymes in neuronal axons and the mitochondria under normal circumstances. These regularly occurring epigenetic actions in the body may also be effectively inhibited by HDAC inhibitors that are meant to target only mechanisms underlying epileptogenesis. For example, HDAC inhibitors such as valproic acid can cause global histone acetylation, resulting in cell death. Therefore, it is increasingly important to improve selectivity of individualized isoforms of HDAC inhibitors with specific pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties to increase their therapeutic potential in epilepsy.

3.2. Targeting HDAC inhibitors to prevent epileptogenesis

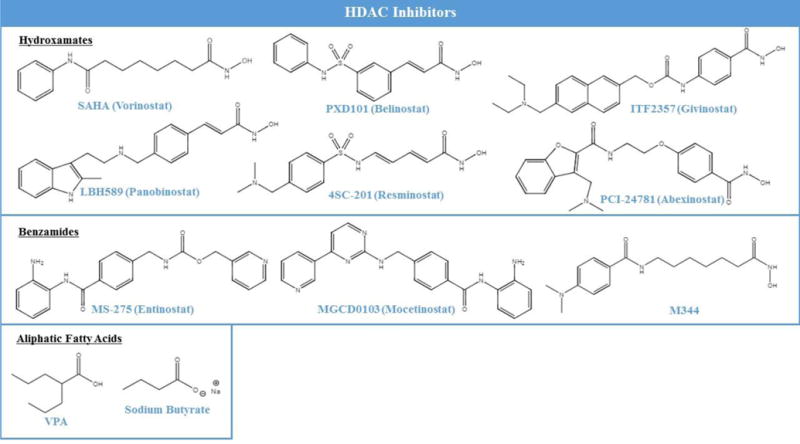

HDAC inhibitors are important regulators of diseases that are associated with epigenetic dysregulation (Fig. 1). There are three families of HDAC inhibitors (Fig. 2): the hydroxymates such as vorinostat and trichostatin A; benzamides such as entinostat and mocetinostat; and aliphatic fatty acids such valproic acid and sodium butyrate. Benzamides have a higher selectivity for class I HDACs while hydroxymates and aliphatic fatty acids target both class I and II HDACs (Ververis et al., 2013). Among their various roles, HDAC inhibitors exert significant influence on the proliferation of tumor cells. These tumor suppressing properties of HDAC inhibitors have contributed to their use as anticancer and neuro-protective agents. Table 1 also shows a list of over half a dozen HDAC inhibitors that have been approved or are undergoing phase 2 or 3 clinical trials for potential therapy in a range of cancers and central nervous system disorders.

Fig. 2. Chemical structures of various classes of HDAC inhibitors.

The first HDAC inhibitors tested in clinical trials for brain disorders were predominantly the family of aliphatic fatty acids. This family of HDAC inhibitors was highly effective in targeting epigenetic enzymes in the brain owing to their ability to cross the blood-brain barrier. Valproic acid is the most investigated epigenetic agent in the family of aliphatic fatty acids. Even before being thoroughly investigated in clinical trials for therapeutic potential in CNS disorders, valproic acid was used as an off-label mood stabilizer in bipolar disorder (Haddad et al., 2009). In clinical trials, valproic acid showed effectiveness as an antipsychotic agent for acute mania (Haddad et al., 2009). When tested in clinical trials for schizophrenia however, valproic acid showed no effectiveness in seven different trails (Schwarz et al., 2008). In animal models of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), valproic acid effectively reversed cognitive impairment and encephalopathy, but these findings did not translate into clinical efficacy (Wu et al., 2013). A meta-analysis of clinical studies for AD showed that valproic acid had no effectiveness in reversing cognitive decline (Amman et al., 2009; Xiao et al., 2010). In a mouse model of Huntington disease, valproic acid showed promising results leading to a Phase I clinical study in patients with Huntington disease. In addition, treatment with the HDAC inhibitor phenylbutyrate demonstrated a safe and positive effect on Huntington disease markers (Hogarth et al., 2007). The next round of Phase II trials has been completed but results have not been made publicly available (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00212316).

In relation to epilepsy, the HDAC inhibitor valproic acid increases levels of GABA, an inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain, while also serving as an epigenetic modulator of histone acetylation and DNA methylation (Gottlicher et al., 2001). It is one of the well-established AEDs, and shows increasing anticonvulsant effects over time (Gottlicher et al. 2001). Chronic treatment with valproic acid has been shown to simultaneously modify multiple aspects of the epigenome, promoting increased H3 acetylation in the brain (Eleuteri et al. 2009), and facilitating the direct or indirect demethylation of DNA (Dong et al. 2007). This ability to exert multiple effects on the epigenome further contributes to valproic acid’s intrigue as an epigenetic anti-convulsive agent. Furthermore, long-term cognitive impairment associated with the proliferation of neural progenitor cells in the dentate gyrus (DG), which occurs as a result of kainic-induced seizures, can be blocked by treatment with valproic acid (Jessberger et al., 2007). This ability to alter histone deacetylase-dependent gene expression in the DG lends protection from seizure induced cognitive impairments. Valproic acid also increased seizure threshold and reduced seizure incidence and severity in an electroconvulsive model of epilepsy.

Sodium butyrate is another promising HDAC inhibitor in the family of aliphatic fatty acids. Sodium butyrate, was reported to increase H3 and H4 acetylation in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex of mice (Deutsch et al. 2008). The same study showed that sodium butyrate also improved the anticonvulsant activity of MK-801 (dizocilpine), an NMDA receptor antagonist. Sodium butyrate was also shown to modulate the effects of the AED flurazepam to antagonize electrically precipitated seizures (Deutsch et al., 2009). These studies suggest that sodium butyrate is an effective epigenetic agent in an electroconvulsive shock model of epileptogenesis and enhances the effects of certain AEDs when administered in conjunction.

The viability of utilizing sodium butyrate for effective disease modification of epileptogenesis was also tested in the hippocampus kindling model, a widely used animal model for studying mesial temporal lobe epileptogenesis (Reddy et al., unpublished). Sodium butyrate was administered twice daily for sustained HDAC inhibition, and mice were subjected to daily kindling epileptogenic stimulation. Treatment with sodium butyrate significantly decreased the development of epileptogenesis as evident by delayed occurrence of severe epilepsy with stage 4/5 seizures and reduced severity of behavioral seizure expression. Sodium butyrate showed marked ‘antiepileptogenic effect’ as evident by reduced epileptogenic rate for generalized seizures. However, sodium butyrate did not affect the rapid kindling epileptogenesis or seizures in fully-kindled mice indicating lack of acute effect on seizure susceptibility.

Among the hydroxymate family of HDAC inhibitors, vorinostat (SAHA) is currently being investigated in a Phase I–II clinical trial for Niemann-Pick disease. This disease is caused by a partial deficiency of lysosomal enzymes and is characterized by neurodegeneration and early onset death during adolescence. The study is currently recruiting participants (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02124083).

The hydroxymate family has yielded encouraging evidence showing increased neuronal survival in epilepsy (Kobow and Blumcke, 2011). This was reported with both trichostatin A and vorinostat (SAHA). However, among existing AEDs that were discovered to have HDAC inhibitory activity, the dilemma still remains that these drugs can exert global epigenetic effects on DNA methylation and histone acetylation leading to cell death (Hwang et al., 2013). Therefore, the development of potent, highly specific HDAC inhibitors which can target transcriptionally responsive genes may be well-suited in inhibiting epileptogenesis.

In the benzamide family of HDAC inhibitors, nicotinamide is being tested in a Phase I clinical trial for safety and efficacy in Alzheimer’s and dementia. Results from a mouse model of Alzheimer’s demonstrated that nicotinamide was effective in delaying cognitive decline (Liu et al., 2013). The results of the clinical trial have yet to be made publicly available (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00580931).

Lastly, a newly synthesized HDAC inhibitor FRM-0334 has also entered clinical trials to treat moderate dementia in patients with a mutated copy of the granulin gene. This particular gene is responsible for cell migration and cell division. The study was launched in 2014 with 30 subjects and is currently ongoing (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02149160).

3.3. Targeting HAT modulators to interrupt epileptogenesis

Histone alterations by HAT mechanism may underlie some epileptogenic or seizure-causing events. There is very limited information on this putative mechanism. HATs and HDACs are recruited to their target promoters through interactions with sequence-specific transcription factors. They usually function within a multisubunit complex in which the other subunits are necessary for them to modify histone residues around the binding site (Fig. 1). H3 and H4 histone proteins are the primary targets of HATs, but H2A and H2B are also acetylated. These histone modifications alter the packing of chromatin. HATs act as transcriptional co-activators or gene silencers. Some HAT transcriptional co-activators contain a bromodomain. HAT mechanisms are essential for cell maintenance and survival and thus, alterations in HATs are implicated in neurodegenerative diseases. The dysregulation of the equilibrium between acetylation and deacetylation has been associated with the disease progression such as cancer and neurodegeneration. This was evident with small molecular inhibitors of HATs such as garcinol, a potent HAT inhibitor (Zhao et al., 2012; Furdas et al., 2012; Oike et al., 2012). The role of HATs is evidently stronger in learning and synaptic function. Mutations in the genes encoding either of the two well-known HATs, CBP and p300, leads to Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome, an autism spectrum disorder (Table 1) (Petrij et al, 1995; Bartsch et al, 2005; Roelfsema et al, 2005; Urdinguio et al, 2009). Furthermore, CBP has a role in the pathophysiology of Huntington disease (Jiang et al, 2006). Curcumin, a polyphenol present in a curry spice, has been shown to modulate HATs (Huang et al., 2016). Curcumin can attenuate seizures and prevent neurodegeneration in the kainate-induced model of TLE (Kiasalari et al., 2013). However, no drugs targeting HAT have been FDA approved or are in clinical trials for the treatment of brain disorders. Further studies on the complex relationship between epigenetic regulation of histones by HATs and epilepsy development are clearly warranted.

Overall, currently there is intense effort to identify an epigenetic mechanism by which the brain controls over-excitability and seizures following brain injury. A more rational, effective strategy for preventing epilepsy is to target the primary signaling pathways that initially trigger the numerous downstream cellular and molecular mechanisms mediating the development of epilepsy, as the brain becomes progressively more prone to seizures because of injury factors. Blocking the critical epigenetic HDAC pathway may interrupt the process that causes epilepsy. In fact, a few HDAC inhibitors that are tested for gastrointestinal and oncological conditions, can be used to inhibit the HDAC pathway and thus may represent a simple therapy for preventing epilepsy in at-risk people. HAT modulators are another emerging class of epigenetic drugs that can interrupt epileptogenesis.

4. Targeting DNA methyl transferases and demethylases

DNA methylation is accomplished by a group of enzymes called DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), which are essential for gene regulation in the CNS (Fig. 1). There are three active subfamilies of DNMT enzymes (DNMT1, DNMT3a, and DNMT3b). The latter two enzymes are responsible for de novo methylation of new sites on the genome, while the role of DNMT1 is to maintain pre-existing DNA methylation tags (Song et al., 2012). Methylation occurs on the cytosine bases in DNA and also on the lysine and arginine residues on histone tails (Scharf and Imhorf, 2011). DNMTs transfer methyl groups from S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) to cytosine bases at CpG (5′-cytosine-phosphate-guanine-3′) dinucleotide sequences forming 5-methylcytosine (Robertson, 2005). Symmetrical methylation of DNA induces a conformational change to its structure that prevents transcription factors from recognizing the DNA. This results in a silencing effect on gene expression (Barre’s et al., 2009).

Methylation by DNMTs will have a direct inhibitory effect on gene transcription and indirect gene silencing effect mediated by methyl-CpG-binding domain proteins (MBDs). MeCP2 is one such MBD that binds DNA and regulates transcription at methylated-CpG gene loci. CpG in double stranded DNA is a palindromic sequence and DNA methylation at the CpG site can be a heritable epigenetic mark passed to offspring (Kriaucionis et al., 2009). Methylation at non-CpG sites increases in adult neurons when the pattern of methylation does not need to be preserved and may be induced by environmental influences (Guo et al., 2014). The discovery of Non-CpG methylation sites greatly expands the potential of epigenetic reprogramming influenced by environmental factors.

De novo DNA methylation by DNMT3a plays a critical role in memory formation. The inhibition of DNMT activity using RG108 affected learning of new cues but had no effect on retrieving memories consolidated before DNMT inhibition (Day et al., 2013). Furthermore, DNMT inhibitors decitabine and zebularine have both been reported to inhibit long-term memory potentiation in the hippocampus (Levenson et al., 2006). A study using double conditional knockouts of Dnmt3a and Dnmt1 genes resulted in inhibition of DNA methylation and impaired learning and memory (Feng et al., 2010). Based on these reports, it is evident that de novo methylation carried out by DNMT3a is a critical target for the modulation of cognitive and memory-based impairments. DNMTs also play a key role in the development of epilepsy as evidenced by studies of DNMT inhibitors. Inhibiting DNA methylation via DNMT inhibitor RG108 resulted in Gria2 upregulation and blocked the seizure inducing effects of kainic acid in the hippocampus (Machnes et al., 2013).

The increased activity of DNMT enzymes and the subsequent hypermethylation is collectively referred to as the ‘methylation hypothesis of epileptogenesis’ (Kobow and Blumcke, 2011). Hypermethylation of certain extracellular matrix proteins such as Reelin is directly implicated in the pathophysiology of temporal lobe epilepsy (Kobow et al., 2009). Reelin is not only responsible for normal dendritogenesis, synaptogenesis, and synapse maturation, but also plays a vital role in maintaining the correct laminar structure of granule cells in the DG (Herz and Chen, 2006). DNA methylation causes low expression of Reelin in the DG and leads to the anatomical hallmark of altered granule cells (Heinrich et al., 2006). DNA methylation plays a critical role in the rapid onset and severity of seizure activity. At the onset of epilepsy, an increase in epigenetic modifications such as DNA methylation takes place. These modifications lead to increased seizure activity and contribute to the development of the epilepsy (Kobow and Blumcke, 2011). In one particular study, DNMT inhibition in neural progenitor cells altered neuronal cell survival, synaptogenesis, plasticity, and memory (Feng and Nestler 2010). Therefore, DNMT activity is crucial and must be tightly regulated. Altered DNMT activity has been implicated in several neurological disorders such as autism, Alzheimer’s, brain tumors, spinal muscular atrophy, and epilepsy (Henshall and Kobow, 2015). In contrast, demethylation by demethylases (DMs) exerts strong activating effect on gene expression. Deregulation of DNA methylation has been directly linked to a myriad of brain disorders such as stroke and epilepsy (Hwang et al., 2013). Developing novel drugs that allow for specific inhibition of these methylating pathways may lead to breakthroughs in retarding the progression of epileptogenesis.

4.1. Role of DNMTs and DMs in epileptogenesis

Based on studies investigating DNA methylation patterns listed in Table 4, evidence suggests that DNMT-induced DNA methylation is a contributing factor associated with epileptogenesis and recurrent seizure activity (Fig. 1). In patients with temporal lobe epilepsy, the up-regulation of DNMT activity has been well-reported (Kobow et al., 2009; Zhu et al., 2012; Kobow and Blumcke, 2011). Furthermore, the analysis and comparison of chronic epileptic animals and healthy controls demonstrated that genomic-wide changes in DNA methylation were present following status epilepticus (Kobow et al, 2013; Williams-Karnesky et al., 2013). Specifically, in the pilocarpine-induced rat model of chronic epilepsy, a significant up-regulation of global DNA methylation was observed (Kobow et al., 2013). Moreover, global increase in hippocampal DNA methylation was also reported in the kainic acid induced rat model of chronic epilepsy (Williams-Karensky et al., 2013). These reports are in line with reports of over-expression of DNMT1 and DNMT3a in temporal neocortex samples from brain samples of temporal lobe epilepsy (Kobow and Blumcke, 2012; Zhu et al., 2012).

Table 4.

Summary of DNA methylation studies in epilepsy models.

| Model | Epigenetic Changes | Clinical Implications | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| SE (KA, mice) | Global DNA hypomethylation of 275 genes; hypermethylation of 13 genes | Seizure susceptibility | Miller-Delaney et al. (2012) |

|

| |||

| SE (KA, mice) | Increased Grin2b methylation; Reduced BDNF methylation; reduced Grin2b mRNA; Increased BDNF mRNA | Seizure susceptibility | Ryley Parrish et al. (2013) |

|

| |||

| SE (KA, rat) | Global DNA Hypermethylation; adenosine augmentation reduced hypermethylation | Seizure susceptibility | Williams-Karnesky et al. (2013) |

|

| |||

| SE (Pilo, rat) | Global DNA hypermethylation of 1452 loci; hypomethylation of 1121 loci | Seizure susceptibility | Kobow et al. (2013) |

|

| |||

| TLE (Hippo) | Increased reelin methylation; reduced reelin mRna | Epilepsy | Kobow et al. (2009) |

|

| |||

| TLE (Hippo) | Increased DNMT1 and DNMT3a | Epilepsy | Zhu et al. (2012) |

|

| |||

| TBI (Wt, rat) | Increased DNMT1 | Post-traumatic epilepsy | Lundberg et al. (2009) |

|

| |||

| TBI (Wt, rat) | Reduced methylation in microglia and macrophages | Post-traumatic epilepsy | Zhang et al. (2007) |

Adenosine is also a crucial factor that influences DNMT enzymatic activity in the brain. It exerts its effects in the SAM-dependent pathway, which is one of the major sites of DNMT regulation. SAM donates its own methyl group to DNA in a mechanism catalyzed by DNMT. This yields the compound S-adenosyl-homocysteine (SAH) which is further converted to adenosine. Due to the nature of the equilibrium constant, the reaction will only proceed in the forward direction if adenosine levels are low enough (Boison et al., 2002). If SAH levels rise as a result of adenosine buildup, DNMT activity will be inhibited (Boison, 2016). Therefore, adenosine plays a critical role as an endogenous regulator of DNMT activity. Based on this premise, studies have shown that adenosine augmentation significantly reduces DNA methylation in status epilepticus models (Williams-Karnesky et al., 2013). Adenosine also inhibited mossy fiber sprouting in the hippocampus and prevented the progression of epilepsy for up to 3 months (Boison, 2016). Moreover, the role of glycine-N-methyltransferase (GNMT) in competitively binding methyl groups in the SAM-dependent pathway was recently discovered. Glycine augmentation may thereby competitively bind methyl groups destined to be donated to DNA and significantly alter DNMT activity and DNA methylation. These factors in conjunction with DNMT inhibitors show promise in preventing the progression of epileptogenesis. In a recent study investigating the antiepileptogenic potential of adenosine augmentation, kainic acid induced status epilepticus rats had seizure incidence completely suppressed (Williams-Karneksy et al., 2013) The study also reported that seizure incidence remained markedly reduced for at least three months after adenosine augmentation therapy. These results strongly support the notion that adenosine augmentation alone may be sufficient in restoring altered DNA methylation activity and retarding the progression of epileptogenesis (Williams-Karensky et al., 2013; Boison, 2016). Moreover, HDAC inhibitors developed for epileptogenesis should also up-regulate adenosine and glycine activity in the brain, which would result in dual endogenous inhibition of DNMT activity.

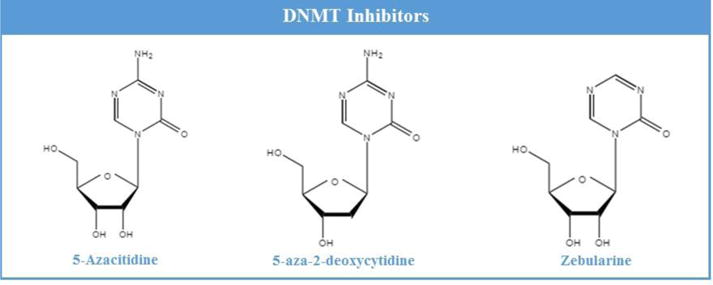

4.2. Development of DNMT inhibitors to prevent epileptogenesis

Currently, we are not aware of any studies that directly explore DNMT inhibitors as a pharmacological intervention for preventing epileptogenesis in animal models of status epilepticus or temporal lobe epilepsy (Hwang et al., 2013). However, it has been reported that inhibition of DNMTs in hippocampal neurons results in suppression of neuronal excitability (Nelson et al., 2008). Studies in vitro also suggest that DNMT inhibitors such as Zebularine result in decreased spontaneous neuro-excitatory transmission in primary hippocampal neurons (Levenson et al., 2006). The underlying mechanism may influence the genes that are associated with neuronal hyperactivity through DNA methylation. These inhibitory effects on neuronal hyper-excitability are modulated by the MBD MeCP2, the mutated gene in Rett syndrome which manifests in spontaneous seizure activity in the disorder.

Furthermore, evidence of global methylation in status epilepticus studies has made developing novel DNMT inhibitors and testing them in epileptogenesis models a high priority. (Kobow et al., 2009; Miller-Delaney et al., 2012). DNMT inhibitors developed to date function by preventing methylation of neighboring sites on DNA in the brain (Kelly et al., 2010). In development of DNMT inhibitors that can penetrate the blood-brain barrier, it is vital to consider toxicity, potency, and specificity. In this regard, second generation DNMT inhibitors should target the translation machinery of mRNAs that encode for DNMTs. This would concede greater regulatory control in inhibiting the initial development of epilepsy (Hwang et al., 2013).

5. Selective inhibition of BET bromodomains

Bromodomain and extra-terminal domains (BETs) are a superfamily of bromodomains that recognize acetylated lysine residues on core histone tails of DNA and may be referred to as ‘readers’ (Fig. 1). In other words, BETs interpret the epigenetic marks encoded by ‘writers’ and ‘erasers’ and therefore, play a key regulatory role in the epigenetic modifications underlying epilepsy. Upon recognizing epigenetic marks on histone tails, BETs bind residues on histone tails and induce a cascade of events that up-regulate the expression of certain genes. These domains exert major influence on cancer genes through regulation of oncogene transcription. BET inhibitors have been rapidly developed over the last five years for the treatment of tumor progression. However, investigation in to their role as therapeutic agents for epilepsy has been very limited, with studies producing some very novel findings, although with significant shortcomings.

5.1. Role of BETs inhibitors in epilepsy

Among the latest literature on BETs, a study explored the role of the BET protein Brd4 in up-regulating transcription in neurons (Korb et al., 2015). The authors reported novel findings about the function of Brd4 in the brain as a mediator of transcriptional regulation underlying memory and learning. It was discovered that inhibition of the Brd4 protein altered synaptic protein function leading to decreased seizure susceptibility. To investigate the effect of Brd4 inhibition on seizure susceptibility, two different animal models of epilepsy were used. Jq1 was used a specific inhibitor of Brd4 and was administered via intraperitoneal injection (50 mg/kg in DMSO) for one week. Seizures were induced in mice using pentylenetetrazol (PTZ), a GABAA receptor inhibitor that increases excitatory activity in neurons. Mice treated with Jq1 showed a significant reduction in seizure susceptibility as measured by the Racine scale. Mice in the Jq1 treatment group had a 100% survival rate and a faster time of recovery to normal movement as compared to control mice, which exhibited only a 70% survival rate after seizure induction. Additionally, seizure incidence was also tested using the kindling model of epilepsy. Repeated kindling stimulation for two weeks induced a kindled state in which mice were more prone to seizures due to increased neuronal firing and strengthened neural connections. The results demonstrated that Brd4 inhibition via Jq1 administration significantly decreased the severity of seizures as compared to the control mice in the kindling model. Based on the findings of this study conducted using two different models of epilepsy, it can be concluded that Jq1-like BET inhibitors have pronounced therapeutic potential in curtailing the progression of epileptogenesis.

5.2. Development of BET bromodomains inhibitors in epilepsy

Inhibiting Brd4 function in the brain using the BET inhibitor Jq1 decreases seizure susceptibility in mice (Korb et al., 2015). To our knowledge, this is the first study that has shown the therapeutic potential of BET inhibitors in mitigating seizure incidence in two different animal models of epilepsy. Jq1 reportedly exerts its anticonvulsant effects by decreasing GluA1 levels, a critical subunit of the excitatory AMPA receptor in the brain. The findings of this study validate the exciting premise of developing other specific BET inhibitors involved exclusively in the pathophysiology of epileptogenesis. This novel targeting method would directly inhibit a protein responsible for regulating receptor transcription instead of targeting the proteins or receptors themselves. This would concede a greater degree of modulatory control over synaptic receptor activity and be a more robust and effective method of ameliorating the incidence of seizures and the underlying synaptic activity.

6. Targeted inhibition of miRNAs

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) represent a class of 19–24 nucleotide sequence of noncoding RNAs that regulate gene expression by targeting messenger RNAs (mRNAs) for cleavage or translational repression (Fig. 1). miRNAs function as environmental biosensors that regulate the expression of large gene networks by binding complementary bases of the target mRNA in the 3′ region (Schratt, 2009). More than 2500 miRNAs have been identified in humans, with each capable of influencing gene transcription at multiple mRNA sites. Hence, most miRNAs play a significant role in regulatory processes such as post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression. miRNAs regulate a range of important steps in gene expression including RNA transcription, translation, and expression of key epigenetic enzymes including the aforementioned DNMTs and HDACs (Sato et al., 2011). Moreover, miRNAs modulate translation of genes in early brain development, which are crucial for appropriate dendritogenesis, synaptogenesis, and synapse maturation. Through a system of checks and balances, miRNAs are regulated in a feedback fashion by epigenetic mechanisms such as DNA methylation and histone modification. Collectively, this system of regulatory feedback within the epigenetic framework is referred to as ‘epigenetic-miRNA regulatory circuits’ (Sato et al., 2011).

miRNAs are also increasingly being regarded as viable biomarkers in many disease states. Research has expanded into a number of diseases such as cancer and Alzheimer’s that show altered miRNAs levels capable of predicting onset of disease (Selvamani et al., 2014; Mitchell et al., 2008). Closely monitoring the expression levels of certain miRNAs could potentially allow for detecting the early onset of epileptogenesis and monitoring disease progression. The changes in miRNA levels in bodily fluids such as blood, urine, and saliva allow for non-invasive sample collection and assaying ability with relative accuracy (Baker, 2015). The characteristics of a unique miRNA profile may result in accurate diagnosis of the onset of epileptogenic activity after a precipitating event such as TBI. In other neural diseases, recent studies successfully profiled miRNA levels in the cerebrospinal fluid to validate the expression of Alzheimer’s in patients with the disease (Blennow et al., 2015). Therefore, monitoring expression of certain miRNAs that are up-regulated at the onset of epilepsy may serve as an effective method of screening for epileptogenic activity in the brain immediately following an initial injury to the brain.

6.1. Role of miRNAs as inhibitors and biomarkers in epileptogenesis

Using miRNA inhibitors referred to as antagomirs have helped elucidate the role of miR-34a, miR-132, and miR-184 in neuronal cell death following status epilepticus (Fig. 1) (Sano et al., 2012). A significant up-regulation of miR-134 following experimental epilepsy models such as status epilepticus have been well reported (Jimenez-Mateos et al., 2012, 2015; Peng et al., 2013). miR-134 is responsible for promoting apoptosis (Zhang et al., 2014). Administration of antagomirs that inhibit miR-134 expression have shown promising results in reducing seizure incidence in mouse models of status epilepticus (Jimenez-Mateos et al., 2012, 2015) A list of studies showing miRNA expression in epilepsy studies is compiled in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of miRNAs investigated in multiple epilepsy models.

| miRNA | Model | Expression in Epilepsy | Effect in Study | Clinical Implications | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-34a | SE (KA, mice) | Up-regulated | CA1, CA3 Damage | Proepileptogenic | Sano et al. (2012); Hu et al. (2011) |

| SE (Pilo, rat) | Up-regulated | ||||

| CA1 Protection in experimentally reduced expression levels | Hu et al. (2012b) | ||||

|

| |||||

| miR-128 | Inhibition (mice) | Down-regulated | Mice developed fatal epilepsy in experimentally reduced expression levels | Antiepileptogenic | Tan et al. (2013) |

|

| |||||

| miR-132 | SE (KA, mice) | Up-regulated | CA3 Protection | Proepileptogenic | Jimenez-Mateos et al. (2011) |

| SE (Pilo, rat) | Up-regulated | Not reported | |||

| Hu et al. (2011) | |||||

| SE (Pilo, rat) | Up-regulated | Not reported | |||

| Song et al. (2011) | |||||

|

| |||||

| miR-134 | SE (KA, mice) | Up-regulated | CA3 Protection | Proepileptogenic | Jimenez-Mateos et al. (2012) |

| SE (Pilo, rat) | Up-regulated | Not reported | |||

| Song et al. (2011) | |||||

|

| |||||

| miR-184 | PC (KA, mice) | Up-regulated | CA1 Damage in experimentally reduced expression levels | Antiepileptogenic | McKiernan et al. (2012b) |

Abbreviations: miR, microRNA; PC, seizure preconditioning

miRNAs can also play a crucial role as biomarkers for certain neurological disorders. Recent studies have explored the altered miRNA expression by using an array profile of the hippocampal CA3 region after status epilepticus (Jimenez-Mateos et al., 2011; Song et al., 2011). Specific miRNA biomarkers which were up-regulated in the studies included miR-132, miR-24, miR-29a, miR-99a, miR-134, and miR-357. Specifically, miR-132 showed increased activity in multiple studies and has been identified as an anti-inflammation marker, which is associated with epileptogenesis (Shaked et al., 2009; Vezzani et al., 2011). This data, along with other evidence of up-regulated miRNA activity following kainic acid induced status epilepticus reaffirms the powerful potential of miRNAs to serve as valid biomarkers for hippocampal epileptiform activity.

6.2. Development of miRNA modulators in epilepsy

Emerging evidence on miRNAs points to their key role in mediating epileptogenesis (Selvamani et al., 2012; Yin et al., 2014; Bake et al., 2014). Antagomirs being developed today have the capability of potently inhibiting specific miRNAs to reverse their adverse effects in the progression of epilepsy (Fig. 1). The mechanism of action of these inhibitors is not known to its full extent, but antagomirs have shown promising evidence in protecting against excitotoxicity in animal models (Jimenez-Mateos et al., 2012, 2015). Furthermore, inhibiting methylation of miRNA transcription sites can thereby inhibit transcription of several miRNAs (Bhadra et al., 2013). This may serve as an effective pathway for miRNA inhibition. miRNA profile studies of human epileptic brain samples have also shown localization of specific miRNAs in the nucleus of these neurons (Kan et al., 2012.) Based on these reports, miRNAs can serve as specific biomarkers for epileptogenesis in a brain inflicted with an initial insult that leads to the onset of seizures. Moreover, identifying the direct epigenetic functions of miRNAs that are up-regulated in epileptic brain samples will lead to a better understanding of the complex mechanisms that underlie epileptogenesis.

7. Epigenetic regulation of transcription by REST/NRSF

Transcription factors are DNA-binding proteins that control the rate of transcription by binding specific DNA sequences. The repressor element 1-silencing transcription factor (REST) is one particular transcription factor and is regarded as the “master epigenetic regulator” (Fig. 1) (Tahiliani et al., 2007). REST is also known as Neuron-Restrictive Silencer Factor (NRSF) and functions by recruiting a host of epigenetic corepressors for modulation of DNA, histones, and chromatin (Qureshi and Mehler, 2009). Through this mechanism, REST/NRSF is believed to control the expression of over 1,800 genes associated with synaptic transmission, synaptogenesis, excitability, and neurogenesis (Bruce et al., 2004; Johnson et al., 2006; Ballas and Mandel, 2005; D’Alessandro et al., 2009). REST/NRSF has received a lot of attention since it first linked epigenetic remodeling to seizures. The original report discovered that kainic acid induced seizures in rats correlated with up-regulated REST/NRSF mRNA expression in CA3 hippocampal regions (Palm et al., 1998). Recent studies have reaffirmed that REST/NRSF expression is up-regulated in animal models of induced seizures and ischemic insults (Formisano et al., 2007; Noh et al., 2012). Moreover, REST/NRSF and its truncated isoform, REST4, increased immediately as a result of seizure activity in animal models of epilepsy (Gillies et al., 2009).

REST/NRSF is crucial for the regulation of an array of factors underlying epileptogenesis including growth factors, ion channels, gap junctions, neurotransmitter receptors, and neurosecretory vesicles (Qureshi and Mehler, 2009). Based on reports of REST/NRSF overexpression following seizure activity, it was initially thought that upregulation of REST/NRSF was harmful in neurons. However, recent studies have found that REST/NRSF also functions as a protective homeostatic modulator of intrinsic excitability (Pozzi et al., 2013). REST/NRSF has also been found to have a protective effect on neurons and preserving cognitive function in Alzheimer’s disease (Lu et al., 2014). Therefore, elevated levels of REST/NRSF triggered by hyper-excitability which is characteristic of epileptogenesis, may serve a protective function. In this regard however, there is still some uncertainty about whether the net effect of REST/NRSF-mediated modulation of gene expression is protective in epileptogenesis. A recent finding emerged that HCN1 (hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-regulated cation channel) was repressed after seizures and contributed to the development of epilepsy (McClelland et al., 2011). HCN1 functions to down-regulate excitability in cortical neurons and mice lacking HCN1 in the forebrain exhibit more seizures in both pilocarpine and kindling models of epilepsy (Santoro et al., 2010). REST/NRSF binding to the HCN1 promoter was up-regulated in kainic acid induced seizures. Blocking REST/NRSF binding to HCN1 prevented the down-regulation of HCN1 and resulted in fewer spontaneous seizures (McClelland et al., 2011).

Further evidence has emerged on the role of REST/NRSF expression in epilepsy using REST/NRSF knockout studies. Following REST/NRSF knockout in glutamatergic forebrain neurons, mice exhibited accelerated seizure progression and prolonged afterdischarge in kindling studies (Hu et al., 2011a). However, in conditional knockout of the REST/NRSF gene in all neurons, tonic convulsions and incidence of death required a higher dose of excitotoxin in the PTZ-induced model of epileptogenesis (Liu et al., 2012). The findings of these two studies make it very difficult to conclude whether opposing effects are a result of which cells had REST/NRSF genes conditionally deleted or whether the animal model (kindling or PTZ) had a greater influence. For a more complete investigation into the role of REST/NRSF in transcriptional control, refer to the report by Roopra et al. (2012).

8. Conclusions and future perspectives

Progression of epileptogenesis coincides with the ever-changing landscape of gene expression in the brain. These changes may result in genes being turned on or off, which directly influences gene expression and the pathophysiology underlying epileptogenesis. The altered gene expression rates may trigger neuronal cell death, gliosis, inflammation, axonal and dendritic plasticity, altered ion channel activity, and altered neurotransmitter receptors associated with epilepsy (Pitkanen and Lukasiuk, 2011). The permanent nature of an epileptic brain is also thought to be maintained by transcription factors such as REST/NRSF and epigenetic modulators that regulate DNA/histone structure and function (Henshall and Kobow, 2015). Therefore, pinpointing the exact mechanisms involving DNA methylation, histone acetylation, miRNA expression, BET inhibition, and REST/NRSF activity may lead to breakthroughs in reversing chronic epilepsy and retarding epileptogenesis.

The potential for reversibility in epigenetic therapy is in sharp contrast to the permanent nature of genetic mutations on the genome (Jakovcevski and Akbarian, 2012). This important difference may present a powerful opportunity for developing novel pharmaceutical interventions for epilepsy and related brain disorders. In developing novel epigenetic interventions for epilepsy, we must first address the shortcomings of our current understanding of the epigenetic landscape. Addressing these shortcomings includes investigating the wide array of potential sites for epigenetic modification. Knowledge of the site-specific actions of epigenetic modifications would lend greater specificity in targeting select regions in the brain. Accomplishing this involves incorporating animal knockout models that have specific epigenetic enzyme isoforms deleted. The induced neuropathologies that result from epigenetic knockout studies would shed light on the specific effects of an individual isoform and guide the precise development of isoform-specific inhibitors.

However, focusing exclusively on specificity may not appropriately account for systemic interactions underlying the dynamic and interconnected epigenetic landscape. Therefore, it also imperative to consider how neuronal diseases broadly affect gene expression through the interactions of epigenetic enzymes leading to bidirectional and often opposing effects in the brain. The bidirectional neuroprotective and neurodegenerative effects of some enzyme isoforms such as HDAC6 have been recognized. Such bidirectional effects validate the need for combination therapy, either in conjunction with other epigenetic agents or existing AEDs. Reaffirming this premise, a study showed that AEDs were more effective in ameliorating electroconvulsive seizure activity when used in combination with the HDAC inhibitor sodium butyrate. In fact, sodium butyrate improved the anticonvulsant activity of dizocilpine and flurazepam in experimental seizure models (Deutsch et al., 2009).

Many epigenetic changes and modifications have normal physiological roles, so it is difficult to directly attribute their activity in certain regions of the brain to epileptic mechanisms. However, recent studies have uncovered many epigenetic mechanisms in epileptogenesis (see Tables 3–6). This has led to the exciting possibility of targeting these epigenetic pathways to find a permanent cure for epilepsy. The types of therapeutic drugs that should be targeted include DNMT inhibitors and HDAC inhibitors that can easily penetrate the blood-brain barrier. Inhibition of histone deacetylation by HDACs appears to be a very promising epigenetic target for therapeutic potential as studies in animal models have shown that HDAC inhibitors can effectively retard epileptogenesis. Furthermore, inhibition of certain miRNAs and BETs have led to promising results in epilepsy models.

Epigenetic interventions may be incredibly useful in targeting epileptogenesis due to the fact that epigenetic a modifications are further potentiated by the progression of epileptogenesis itself. In other words, the underlying pathway that leads to the progression of epileptogenesis is modulated similarly to a positive feedback mechanism that increases in severity with time. Moreover, targeting transient compounds such as adenosine and glycine that are pivotal in the methylation equilibrium reactions underlying epileptogenesis may have therapeutic potential. Furthermore, glycine augmentation therapies via diet or injection may be an alternate route of targeting DNA methylation and hence epileptogenesis. More research into the role of adenosine-glycine interactions in the epigenetic pathways beyond DNA methylation should be explored. DNMT inhibitors should be administered in conjunction with these agents to up-regulate adenosine and glycine activity in the brain. The cumulative effect of these therapies could result in endogenous inhibition of DNMT activity and significant retardation of epileptogenesis.

Novel findings regarding the role of miRNAs and BETs in mediating epileptogenesis have contributed to our understanding of their role in the disease process (Selvamani et al., 2012; Yin et al., 2014; Bake et al., 2014; Korb et al., 2015). miRNA antagomirs have been reported to inhibit specific miRNAs to reverse their adverse effects in the progression of epilepsy. Furthermore, miRNAs can also serve as valid biomarkers for epileptogenesis. Identifying the direct epigenetic functions of miRNAs that are up-regulated in epileptic brain samples will lead to a better understanding of the complex mechanisms that underlie epileptogenesis. Another notable finding that links epigenetic mechanisms to epileptogenesis includes the discovery of epilepsies caused by mutations in the epigenetic enzymes themselves. Of particular interest is Rett syndrome (Guy et al., 2007; Amir et al., 1999; Shahbazian et al., 2002). This genetic disorder is caused by mutations in the gene encoding for MeCP2 and results in chronic infantile spasms and epilepsy (Amir et al., 1999). The discovery of epilepsies caused by altered epigenetic machinery further validates the opportunity to investigate these targets for their viability in halting epileptogenesis.

In summary, epigenetic modulation is a powerful strategy for therapeutic intervention with the possibility of novel drugs that inhibit epigenetic enzymes critically involved in the progression of epileptogenesis. The emerging evidence reviewed in this article reveal the pharmacotherapeutic potential of targeting epigenetic pathways underlying the development of epilepsy. The next steps for research in the field should focus on how to identify epileptogenic disorders that would respond effectively to a particular epigenetic therapy. Modulating these pathways by altering or inhibiting select epigenetic agents can lead to the effective interruption of epileptogenesis and chronic epilepsy. Nevertheless, the framework for using epigenetic drugs, in combination or alone, may present a momentous opportunity for curing epilepsy.

Fig. 3. Chemical structures of DNMT inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs through the FY 2015 Epilepsy Research Program under Award #W81XWH-16-1-0660. Opinions, interpretations, conclusions and recommendations are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the U.S. Department of Defense.

Abbreviations

- AEDs

antiepileptic drugs

- BET

bromodomain and extra-terminal domains

- CCI

controlled cortical impact

- CNS

central nervous system

- DG

dentate gyrus

- DM

demethylase

- DNMT

DNA methyltransferases

- EC

electroconvulsive

- HAT

histone acetyltransferases

- HATi

histone acetyl transferase inhibitor

- HCN

hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide

- HDAC

histone deacetylases

- HDACi

histone deacetylase inhibitor

- IBO

ibotenic acid

- KA

kainic acid

- KO

knockout

- MBD

methyl-CpG-binding domain proteins

- miRNA

micro-RNA

- NRSF

neuron-restrictive silencer factor

- PTZ

pentylenetetrazol

- RES

repressor element 1-silencing transcription factor

- SE

status epilepticus

- TBI

traumatic brain injury

- TLE

temporal lobe epilepsy

- TSA

trichostatin A

- VPA

valproic acid

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Amann B, Pantel J, Grunze H, Vieta E, Colom F, Gonzalez-Pinto A, Naber D, Hampel H. Anticonvulsants in the treatment of aggression in the demented elderly: an update. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2009;5:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amir RE, Van den Veyver IB, Wan M, Tran CQ, Francke U, Zoghbi HY. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nat Genetics. 1999;23:185–188. doi: 10.1038/13810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acharya MM, Hattiangady B, Shetty AK. Progress in neuroprotective strategies for preventing epilepsy. Progr Neurobiol. 2008;84:363–404. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agis-Balboa RC, Pavelka Z, Kerimoglu C, Fischer A. Loss of HDAC5 impairs memory function: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2013;33:35–44. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-121009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertson TE, Joy RM, Stark LG. A pharmacological study in the kindling model of epilepsy. Neuropharmacol. 1984;23:1117–1123. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(84)90227-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alldredge BK, Lowenstein DH. Status epilepticus related to alcohol abuse. Epilepsia. 1993;34:1033–1037. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1993.tb02130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arboix A, Garcia-Eroles L, Massons JB, Oliveres M, Comes E. Predictive factors of early seizures after acute cerebrovascular disease. Stroke. 1997;28:1590–1594. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.8.1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arntz R, Rutten-Jacobs L, Maaijwee N, Schoonderwaldt H, Dorresteijn L, van Dijk E, de Leeuw FE. Post-stroke epilepsy in young adults: a long-term follow-up study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55498. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bake S, Selvamani A, Cherry J, Sohrabji F. Blood brain barrier and neuroinflammation are critical targets of IGF-1-mediated neuroprotection in stroke for middle-aged female rats. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91427. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker M. MicroRNA profiling: separating signal from noise. Nature Methods. 2010;7:687–692. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0910-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballas N, Mandel G. The many faces of REST oversee epigenetic programming of neuronal genes. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:500–516. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker-Haliski ML, Friedman D, French JA, White HS. Disease modification in epilepsy: from animal models to clinical applications. Drugs. 2015;75:749–767. doi: 10.1007/s40265-015-0395-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barre’s R, et al. Non-CpG methylation of the PGC-1alpha promoter through DNMT3B controls mitochondrial density. Cell Metab. 2009;10:189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch O, Schmidt S, Richter M, Morlot S, Seemanová E, Wiebe G, Rasi S. DNA sequencing of CREBBP demonstrates mutations in 56% of patients with Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome (RSTS) and in another patient with incomplete RSTS. Hum Genet. 2005;117(5):485–493. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-1331-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beghi E, D’Alessandro R, Beretta S, Consoli D, Crespi V, Delaj L, Gandolfo C, Greco G, La Neve A, Manfredi M, Mattana F, Musolino R, Provinciali L, Santangelo M, Specchio LM, Zaccara G, Epistroke G. Incidence and predictors of acute symptomatic seizures after stroke. Neurol. 2011;77:1785–1793. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182364878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger SL. The complex language of chromatin regulation during transcription. Nature. 2007;447:407–412. doi: 10.1038/nature05915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhadra T, Bhattacharyya M, Feuerbach L, Lengauer T, Ban- dyopadhyay S. DNA methylation patterns facilitate the identification of microRNA transcription start sites: A brain-specific study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e66722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biernaskie J, Corbett D, Peeling J, Wells J, Lei H. A serial MR study of cerebral blood flow changes and lesion development following endothelin-1-induced ischemia in rats. Magn Reson Med. 2001;46:827–830. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bladin CF, Bornstein N. Post-stroke seizures. Handb Clin Neurol. 2009;93:613–621. doi: 10.1016/S0072-9752(08)93030-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bladin CF, Alexandrov AV, Bellavance A, Bornstein N, Chambers B, Cote R, Lebrun L, Pirisi A, Norris JW. Seizures after stroke: a prospective multicenter study. Arch Neurol. 2000;57(11):1617–1622. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.11.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blennow K, Dubois B, Fagan AM, Lewczuk P, de Leon MJ, Hampel H. Clinical utility of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in the diagnosis of early Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dementia. 2015;11:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]