Abstract

Background

Concerns about polypharmacy and medication side effects contribute to undertreatment of geriatric pain. This study examines use and effects of pharmacologic treatment for persistent pain in older adults.

Methods

The MOBILIZE Boston Study included 765 adults aged ≥70 years, living in the Boston area, recruited from 2005 to 2008. We studied 599 participants who reported chronic pain at baseline. Pain severity, measured using the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) severity subscale, was grouped as very mild (BPI<2), mild (BPI 2–3.99), and moderate to severe (BPI 4–10). Medications taken in the previous 2 weeks were recorded from medication bottles in the home interview.

Results

Half of participants reported using analgesic medications in the previous 2 weeks. Older adults with moderate to severe pain were more likely to use one or more analgesic medications daily than those with very mild pain (49% versus 11%, respectively). The most commonly used analgesic was acetaminophen (28%). Opioid analgesics were used daily by 5% of participants. Adjusted for health and demographic factors, pain severity was strongly associated with daily analgesic use (moderate-severe pain compared to very mild pain, adj. OR=7.19, 95% CI 4.02–12.9). Nearly one-third of participants (30%) with moderate to severe pain felt they needed a stronger pain medication while 16% of this group were concerned they were using too much pain medication.

Conclusion

Serious gaps persist in pain management particularly for older adults with the most severe chronic pain. Greater efforts are needed to understand barriers to effective pain management and self-management in the older population.

Keywords: Older adults, pain, analgesic medications, side effects, epidemiology

Introduction

Chronic pain is one of the most common problems in older adults, affecting more than half of elderly people living in the community and more than 80% of those living in nursing homes.1 Additionally, chronic pain is a primary reason people seek medical treatment, with a cost exceeding half a trillion dollars per year.2 Nonetheless, chronic pain in older adults is often undertreated.3,4 Hence, health care providers face a significant challenge in pain management for elderly people, having to balance pain relief with adverse effects of treatment.

Pharmacological approaches are critically important interventions for pain control as they are often cost effective and some medications are available without a prescription.5 Generally, the most frequently used class of over-the-counter (OTC) medications among community-dwelling elderly individuals is analgesic medication.6 As a result, much pain management for chronic musculoskeletal pain in older adults occurs as self-management, possibly contributing to undertreatment of pain in this population. Although older adults with chronic pain may seek healthcare to obtain pain relief, little is known about the relation between pain severity and analgesic use in older adults.

For health care providers, selection of analgesic medications for older adults requires an understanding of age-related pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetic changes, and requires taking into account comorbid conditions and other medications including those with and without a prescription.7 Age-related alterations in drug distribution, excretion, and metabolism may lead to longer durations of action, as well as lower or greater plasma concentrations for many pain medications. These processes may result in increased responsiveness to opioids and other analgesics, with an accompanying increased risk of adverse reactions and drug toxicity.8 In addition, comorbid conditions such as those that impair gait, balance, or cognitive function, may make analgesic therapy riskier in older patients as compared to their younger counterparts. Furthermore, although opioid analgesic medications provide effective pain management for patients with moderate to severe pain, their use is limited by patients’ fear of side effects and addiction.9 As a result, clinicians are often hesitant to prescribe some analgesic medications to older adults, a factor that also may contribute to underuse of analgesics.10 The purpose of this study is to gain a better understanding about the association between the use of pharmacologic treatment for pain and pain severity in older adults. In addition, we explored patients’ reports of effectiveness of their current treatment regimens.

Methods

Data Sources

The MOBILIZE Boston Study (MBS), which stands for “Maintenance of Balance, Independent Living, Intellect, and Zest in the Elderly of Boston” is a prospective cohort study of community-living older adults in the Boston area. A detailed description of the methods for the MBS has been published elsewhere.11 Participants were aged 70 years or older living in urban and suburban communities. The participants were recruited door-to-door during the period from 2005 to 2008 using a random sample of older people listed on city and town registers.12 Of the 1,616 older adults who agreed to be screened, 765 people were eligible and enrolled. Participants were eligible if they were aged 70 years or older, able to walk 20 feet unaided, could communicate in English, and planned to stay in the Boston area for at least two years. Exclusion criteria were: diagnosis of a terminal disease, severe hearing or vision deficits, or moderate to severe cognitive impairment (Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) score of less than 18).13, 14 The 2-part baseline assessment consisted of a 3-hour home interview followed within 2 weeks by a 3-hour clinic exam conducted at the study clinic of the Institute for Aging Research (IFAR) at Hebrew SeniorLife in Boston.11

Sociodemographic and Health Measures

Socio-demographic characteristics, including age, gender, race, and years of education, were recorded during the baseline home visit, Body mass index (BMI) was assessed from measured weight and height (weight (kg)/height squared (m2)). Chronic conditions including depression, peripheral neuropathy, diabetes, spinal stenosis/disc disease, and osteoarthritis, were assessed by self-report and/or in the clinical assessment. Depression was measured using a modification of the 20-item Centers for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CESD) scale.15 Semmes-Weinstein monofilament testing was used to assess peripheral neuropathy.16 Diabetes was assessed using a diabetes algorithm based on self-reported physician’s diagnosis, laboratory measures (glucose ≥ 200 mg/dl or hemoglobin Alc >7%), and use of anti-diabetic medications. Osteoarthritis of the hand and knee was defined using clinical criteria from the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), assessed by experienced nurses who were trained by the study rheumatologist (RS).17

Pain Severity

For this study, we analyzed baseline data from 599 participants who reported having pain using the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) pain severity subscale (BPI severity score>0), which made up 78.3% of all participants.18 The BPI severity subscale refers to pain “that you have today that you have experienced for more than just a week or two,” and the score is based on an average of four items measuring pain at its worst, least, on average, and currently, using a 0–10 numeric rating scale. The BPI has been validated in patients with nonmalignant pain.19, 20 BPI severity scores were grouped as very mild (BPI <2), mild (BPI 2–3.99), and moderate to severe (BPI≥4), which approximated tertile groupings. This pain severity classification is associated with poor outcomes including decreased mobility, depression, and falls.21,22,23

Pain Management Strategy (Analgesic Medications)

The ‘medication inventory’ method was performed during the home interview. Participants were asked to show the containers for all the over-the-counter and prescription medications they had taken in the previous two weeks.24 For each medication, research staff recorded the name, route, dose, strength, and frequency of use. Medication names subsequently were coded using the Iowa Drug Information System ingredient codes.25 Analgesic drugs were grouped as non-opioid analgesics, opioid analgesics, and aspirin other than the low daily dose of 325 mg or less for cardio-prevention. These drugs include prescription and non-prescription analgesic use. Prescription analgesic drugs consisted of miscellaneous analgesics, antipyretics, opiate partial agonists, opiate agonists, and selected non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as diclofenac. Non-prescription analgesics included aspirin, ibuprofen, acetaminophen, naproxen, etc.25 Adjuvant medications included antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and corticosteroids. Psychiatric medications included antidepressants, antipsychotics, and anxiolytic mediations. Each medication was categorized as having been used two or more times daily, once daily, less than once a day, and no use.

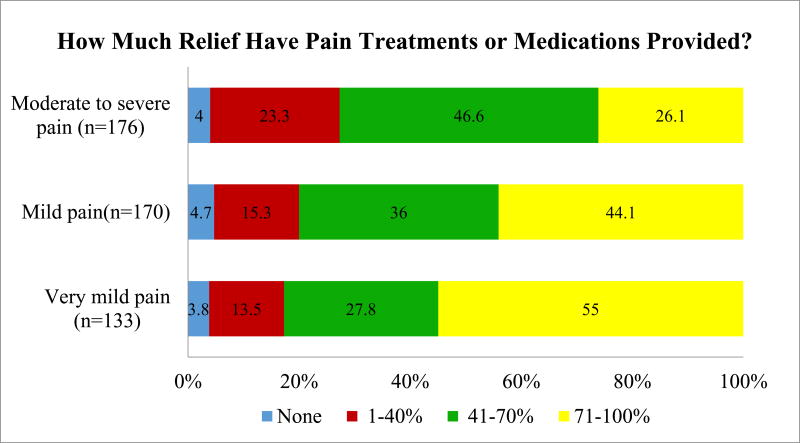

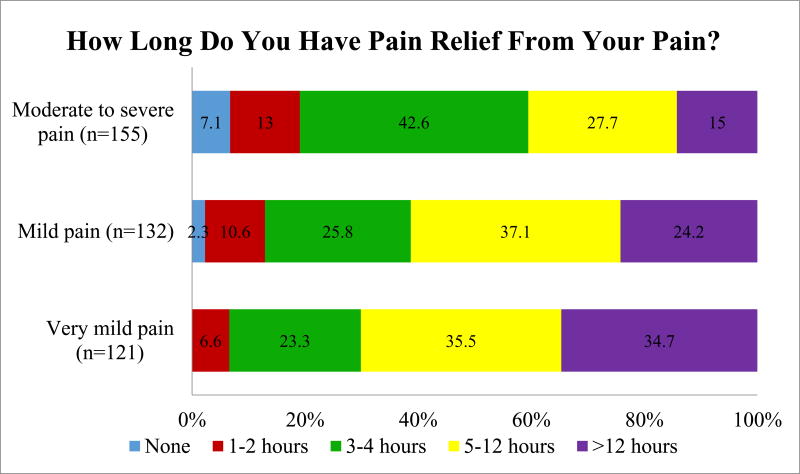

Pain Relief

During the baseline home visit, participants were asked two questions to assess the level of pain relief in the last week, including 1) “How much relief have pain treatments or medications provided?” and 2) “How long did you have relief from your pain?” The level of pain relief ranged from 0% to 100%, with the score of 100% identifying the highest level of pain relief. The duration of pain relief ranged from 0 hours to more than 12 hours, with more than 12 hours indicating a maximum time for pain relief.

Side Effects from Pain Medications

Researchers assessed perceptions of and side effects from medications used for pain management during the home interview. Participants were asked if they had symptoms such as nausea, drowsiness, constipation, diarrhea, or skin reactions after using pain medications. Total numbers of side effects were categorized into none, single side effect, and multiple side effects. Then, participants were asked: “Do you need a stronger type of pain medication?,” “Do you take more of the pain medication than a doctor has prescribed?,” and “Are you concerned about taking too much pain medication?”

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics (frequency distributions and percentages) were used to describe socio-demographics, clinical characteristics, and prevalence of taking analgesic medications in each pain severity group. Chi-square and Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel tests were used to evaluate group differences. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed with daily analgesic use as the dependent variable, and pain severity as the independent variable. Participants with very mild pain comprised the reference group. Model 1 generated odds ratios of the association between pain severity and analgesic use, adjusted for age group, race, education, and gender. Model 2 was additionally adjusted for BMI, peripheral neuropathy, diabetes, spinal stenosis, depression, and osteoarthritis. An alpha level at p <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Of the 765 participants, 599 (78.3%) reported pain and were grouped according to BPI severity ratings, with 35.1% reporting very mild pain (BPI severity score <2), 33.4% reporting mild pain (BPI score 2–3.99), and 31.6% reporting moderate to severe pain (BPI score ≥4). Fewer than one in three (29%) older adults with chronic pain were using analgesic drugs on a daily basis. Participants with moderate to severe pain were more likely to use daily analgesic drugs, which were primarily non-opioid analgesics, than those with very mild pain (47% versus 11%, respectively). Opioid analgesics were used daily by 5% of participants and adjuvant analgesic medications were used daily by 10% of participants overall, with differences observed according to pain severity. Acetaminophen was the most commonly used medication (28%), followed by ibuprofen (10%, see Supplemental Table). Although the proportion of older adults who were using daily psychiatric medication was somewhat greater among those with more severe pain, these differences were not statistically significant (Table 1).

Table 1.

Analgesic, adjuvant, and psychiatric medication use in the previous two weeks by participants reporting chronic pain, MOBILIZE Boston study 2005–2008

| Medication use | Total (n=599) n (%) |

Pain Severity Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very Mild (n=210) n (%) |

Mild (n=200) n (%) |

Moderate-Severe (n=189) n (%) |

P valuea | ||

| Analgesic medicationsb | |||||

| None | 294(49.1) | 142 (67.6) | 93 (46.5) | 59(31.2) | |

| < 1 daily | 131 (21.9) | 45 (21.4) | 49 (24.5) | 37(19.6) | |

| > 1 daily | 174 (29.0) | 23 (11.0) | 58 (29.0) | 93 (49.2) | <0.0001 |

| Opioid analgesic medications | |||||

| None | 554 (92.5) | 209 (99.5) | 189 (94.5) | 156 (82.5) | |

| < 1 daily | 17 (2.8) | 1 (0.5) | 4 (2.0) | 12(6.4) | |

| > 1 daily | 24 (4.7) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (3.5) | 21(11.1) | <0.0001 |

| Non-opioid analgesic medicationsc | |||||

| None | 302 (50.4) | 143 (68.1) | 96 (48.0) | 63 (33.3) | |

| < 1 daily | 130 (21.7) | 44 (20.9) | 49 (24.5) | 37 (19.6) | |

| ≥ 1 daily | 167 (27.8) | 23 (11.0) | 55 (27.5) | 89 (47.1) | <0.0001 |

| Adjuvant analgesic medicationsd | |||||

| None | 537 (89.6) | 194(92.4) | 186 (93.0) | 157 (83.1) | |

| < 1daily | 3 (0.5) | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | |

| > 1daily | 59 (9.9) | 14 (6.7) | 14 (7.0) | 31 (16.4) | 0.004 |

| Psychiatric medicationse | |||||

| None | 462 (77.1) | 170 (80.9) | 147 (73.5) | 145 (76.7) | |

| <1 daily | 24 (4.0) | 10 (4.8) | 11 (5.5) | 3 (1.6) | |

| >1daily | 113 (18.9) | 30(14.3) | 42 (21.0) | 41(21.7) | 0.07 |

Chi square test for overall differences (4–6 df)

Includes all analgesic classes

Includes acetaminophen, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and aspirin (except low dose aspirin for cardio prevention)

Includes antidepressants (amitriptyline, fluoxetine, venlafaxine, duloxetine), anticonvulsants (gabapentin, carbamazepin, levetiracetran, lamotrigine), and corticosteroids (prednisolone, fludrocortisones, methyprednisolone)

Includes antidepressant (non-adjuvant such as trazadone), and anxiolytic medication

When we examined the use of analgesic medication according to pain severity and strata of demographic and health characteristics, differences emerged between groups (Table 2). For example, older women were more likely to use daily analgesic medications than older men but the difference did not persist after stratifying by pain severity. In addition, although whites and non-whites had similarly low proportions of daily analgesic use overall, lower proportions of non-whites were using daily analgesic medications within strata of pain severity, though the differences were not statistically significant. Participants who had chronic musculoskeletal conditions, including spinal stenosis/disc disease, peripheral neuropathy, and osteoarthritis of the hands and/or knees were more likely to use a daily analgesic, even after stratifying by pain severity (Table 2).

Table 2.

Daily analgesic use according to sociodemographic characteristics and pain severity among 599 participants reporting chronic pain in the baseline assessment, MOBILIZE Boston cohort, 2005–2008

| Characteristics | Pain Severity Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total using daily analgesic | Very mild & using daily analgesic | Mild & using daily analgesic | Moderate-Severe & using daily analgesic | |

| Total | 174/599 (29.0) | 23/210 (11.0) | 58/200 (29.0) | 93/189 (49.2) |

| Age | ||||

| < 75 Years | 58/190 (30.5) | 10 (14.5) | 22 (33.9) | 26 (46.4) |

| 75–84 Years | 94/332 (28.3) | 10 (8.3) | 30 (28.0) | 54 (51.5) |

| ≥85 Year | 22/77 (28.6) | 3 (14.3) | 6 (21.4) | 13 (46.4) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 47/199 (23.6) | 7 (7.7) | 22 (33.3) | 18 (42.9) |

| Female | 127/400 (31.8)a | 16 (13.5) | 36 (26.9) | 75 (51.0) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 132/460 (28.7) | 22 (12.4) | 50 (31.1) | 60 (49.6) |

| Non-white | 41/138 (29.7) | 1 (3.1) | 8 (20.5) | 32 (47.8) |

| Education | ||||

| ≤ High school | 69/213 (32.4) | 5 (11.6) | 14 (21.2) | 50 (48.1) |

| Attended coll. | 105/385 (27.3) | 18 (10.8) | 44 (32.8) | 43 (51.2) |

| Body mass index | ||||

| < 25 kg/m2 | 40/165 (24.2) | 6 (9.1) | 17 (29.8) | 17 (40.5) |

| 25–29.9 kg/m2 | 74/251 (29.5) | 13(13.5) | 22 (27.9) | 39 (51.3) |

| >30 kg/m2 | 56/169 (33.1) | 4 (8.9) | 19 (32.2) | 33 (50.8) |

| Chronic conditions | ||||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 12/36 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (27.3) | 9 (42.9) |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 28/75 (37.3) | 2 (10.5) | 6 (24.0) | 20 (64.5)a |

| Diabetes | 43/125 (34.4) | 5 (15.1) | 10 (26.3) | 28 (51.9) |

| Spinal stenosis/disc disease | 53/120 (44.2)a | 4 (12.5) | 17 (50.0) | 32 (59.3)a |

| Depression | 16/49 (32.7) | 0 (0.0) | 3(25.0) | 13 (46.4) |

| Hand or knee osteoarthritis | 99/258 (38.4)a | 12 (18.8) | 31 (34.4) | 56 (53.9)a |

p-value of <0.05 for all noted associations between the characteristics and use of analgesics. Chi square test for gender differences in the entire cohort; Cochran Mantel Haenszel test for the between group differences for analgesic use according to chronic conditions and pain severity categories.

After adjusting for age, gender, race, and education (Model 1, Table 3), pain severity was strongly significantly associated with daily analgesic use (mild pain, OR=3.43, 95% CI=2.01–5.86 and moderate to severe pain, OR=8.86, 95% CI=5.09–15.4), compared to very mild pain. After further adjustment for BMI and major chronic conditions (Model 2), mild pain and moderate to severe pain remained strongly associated with daily analgesic use as compared to very mild pain (mild pain, OR= 3.19, 95% CI =1.84–5.51 and moderate to severe pain, OR=7.19, 95% CI=4.02–12.9). In addition, persons with spinal stenosis/disc disease or osteoarthritis were more likely to use daily analgesics even after adjusting for covariates including pain severity (Table 3).

Table 3.

Likelihood of using daily analgesic medication according to bpi pain severity and demographic and health characteristics among 599 participants with chronic pain at baseline, MOBILIZE Boston cohort, 2005–2008

| Characteristics | Model 1 (n=597) |

Model 2 (n =574) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval)a | ||

| Very mild pain | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mild pain | 3.43 (2.01–5.86) | 3.19 (1.84–5.51) |

| Moderate-Severe | 8.86 (5.09–15.4) | 7.19 (4.02–12.9) |

| Age (year) | ||

| < 75 Years | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 75–84 Years | 0.87 (0.57–1.33) | 0.92 (0.59–1.43) |

| >85 Years | 0.76 (0.41–1.43) | 0.74 (0.38–1.45) |

| Non-white race | 0.75 (0.47–1.20) | 0.78 (0.47–1.29) |

| Education: attended college | 1.19 (0.78–1.82) | 1.17 (0.75–1.84) |

| Gender: women | 1.11 (0.73–1.69) | 1.12 (0.71–1.75) |

| Body mass index: | ||

| < 25 kg/m2 | – | 1.00 |

| 25–29.9 kg/m2 | – | 1.20 (0.70–2.06) |

| >30 kg/m2 | – | 1.23 (0.75–2.02) |

| Peripheral neuropathy | – | 1.25 (0.70–2.20) |

| Diabetes | – | 1.11 (0.67–1.84) |

| Spinal stenosis/disc disease | – | 1.93 (1.20–3.10) |

| Depression | – | 0.74 (0.37–1.51) |

| Osteoarthritis | – | 1.61 (1.08–2.40) |

Multivariable logistic regression models adjusting for all variables shown in models 1 and 2.

In terms of pain relief, older adults with moderate to severe pain reported less relief overall from pain medications and treatments and a shorter duration of relief from medications compared to those with less pain. For example, more than 60% of persons with moderate to severe pain reported their pain relief lasted only 4 hours or less compared to about 30% of those reporting very mild pain (Figures 1A&1B).

Fig. 1A.

Reported amount of pain relief from pain treatment among 599 participants with chronic pain, MOBILIZE Boston cohort

Overall, three out of four participants (74%) with chronic pain reported ever using medications to manage their pain (Table 4). Nearly one-third of participants (30%) with moderate to severe pain felt they needed stronger pain medication compared to 3.5% of those with very mild pain. Only 7% of those with moderate to severe pain felt they needed more medication than was prescribed for their pain, although most reported not using prescription pain medication. About 15% of those with moderate to severe pain were concerned they were using too much pain medication. Only 6% reported having one or more side effects related to use of pharmacologic pain treatments, but those with moderate to severe pain were more likely to report side effects than those with mild pain or very mild pain (11% and 4.2% and 1.4%, respectively) (Table 4). Among the small number of participants reporting side effects, the most common were reports of feeling tired/sleepy (68%), constipation (46%), and nausea/vomiting (42.3%).

Table 4.

Perceptions and side effects of medications used for pain management, among 445 participants with chronic pain who reported using medication to manage their pain, MOBILIZE Boston study 2005–2008

| Variable | Pain Severity Group | P-valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very Mild (n=142) n (%) |

Mild (n=142) n (%) |

Moderate-Severe (n=161) n (%) |

|||

| Do you feel need a stronger type of pain medication?b | 5 (3.5) | 15 (10.6) | 49 (30.4) | <0.0001 | |

| Do you feel need to take more of the pain medication than your doctor has prescribed?c | |||||

| No | 36 (17.4) | 39 (19.6) | 67 (36.0) | ||

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.0) | 13 (7.0) | ||

| Not taking prescription pain medication | 106 (50.5) | 99 (49.8) | 82 (44.1) | ||

| Never take pain medication | 68 (32.4) | 57 (28.6) | 24 (12.9) | <0.0001 | |

| Are you concerned that you use too much pain medication?b | 3 (2.1) | 12 (8.5) | 25 (15.5) | <0.0003 | |

| Total number of side effects from pain medicationsb | |||||

| None | 140 (98.6) | 136 (95.8) | 145 (89.0) | ||

| Single side effect | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.4) | 4 (2.5) | ||

| Multiple side effects | 1 (0.7) | 4 (2.8) | 14 (8.7) | <0.0001 | |

Chi square test for between group differences; Fishers exact test for tables with cell sizes<5

Excludes 152 participants with chronic pain who reported they never take pain medication

Excludes 4 missing responses out of 599 participants with chronic pain

Discussion

This is one of the first studies to investigate the use of analgesic medication according to pain severity in an older population with chronic pain. Only half of those who rated their pain as moderate to severe reported using analgesics on a daily basis. Overall, the results support our hypothesis that many participants with moderate to severe pain were not using analgesics. However, those with more severe pain were more likely to use daily analgesics than those with less severe pain. We did not find disparities in use of analgesics according to sociodemographic characteristics after accounting for pain severity. These findings demonstrate the need for better pain management among older adults, particularly those with more severe chronic pain.

Currently, the American Geriatric Society (AGS) states that pharmacologic treatment is the most common therapy to control pain condition in older people. It recommends that older adults regularly use analgesic medications to maximize pain relief.5 Our study found that 29% of older adults with any chronic pain, and 49% of those with moderate to severe pain used daily analgesic medication. In addition, older women were more likely to use daily analgesic medications than older men. Pokela et al. also reported that around 45% of community dwelling older adults aged ≥75 years old used ≥1 analgesic drug on a daily or an as-needed basis.26 They found that number of factors were associated with use of analgesics in community-dwelling people aged 75 years and older, including being female, living alone, using ≥10 non-analgesic medications, and having poor self-rated health.26 It has also been noted that women have greater pain sensitivity than men, and they report more pain symptoms and seek medical treatment for pain more often than men.27,28 When we examined analgesic use according to pain severity categories, we found modest differences according to the presence of chronic conditions. Specifically, participants who had peripheral neuropathy, spinal stenosis or disc disease, and osteoarthritis were more likely to use analgesic medications than their counterparts without these conditions who reported similar pain severity. The findings suggest that there are other characteristics of pain that may lead to greater use of analgesics, for example, pain distribution or pain quality. A recent study from the MOBILIZE Boston cohort showed that participants reporting neuropathic pain qualities not only reported more severe pain but also more pain interference and more multisite pain.29 Also, persons who experience chronic pain related to diagnosed chronic conditions may see health care providers more often for pain management, and may be more likely to be prescribed medications for pain symptoms.

Analgesic medications that are commonly used among older adults include acetaminophen and other non-opioid analgesics.7,9,30 Acetaminophen is considered the first choice for older adults having mild to moderate pain in part because it is not associated with significant gastrointestinal, renal, or cardiovascular effects associated with use of other analgesic medications.5,30 However, it should be used with caution in elderly people with liver disease, and patients that have a history of alcoholism.26 If acetaminophen is ineffective, it is suggested to cautiously use non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs) and only for short periods.5,9,30,31 In our study, 28% were using acetaminophen and about 1 in 5 participants reported using NSAIDs. A Dutch study by Enthoven et al. reported that 72% of elderly people with low back pain were using analgesic medication. NSAIDs (57%) were more often used than acetaminophen (49%) among these primary care patients aged 55 and older.32 Nonetheless, NSAIDs have been associated with increased hospitalization for renal and gastrointestinal adverse effects, such as hemorrhages, perforations, and peptic ulcers.33,34 In addition, a review study has noted increased risk of cardiovascular events with NSAID use, a finding that may be of particular relevance to older individuals.35 Therefore, clinicians need to be aware of serious adverse effects of NSAIDs among older adults who report persistent pain symptoms.

Current guidelines for managing chronic pain also suggest that healthcare providers consider opioid therapy for older adults who continue to report moderate to severe pain or experience pain-related functional impairment despite non-opioid therapy.5 Opioids, considered the most potent pain relievers, have been found to relieve pain in the short term.31 Most opioid trials have not extended beyond six weeks, thus the findings are not relevant for long-term opioid use.36 Use of opioids can lead to increased risk of falls and fractures especially in older adults.37,38 Older adults with arthritis who initiate therapy with higher opioid doses or those that are short-acting are more likely to report fracture than older adults who took NSAIDs.39 Studies of fall outcomes in persons using opioids and other analgesic medications may be limited in part related to confounding by indication, or inadequate adjustment for pain characteristics known to be associated with falls in older adults.21 Clinicians are already cautious to prescribe opioid therapy for older adults with chronic pain; this is reflected in the low use of opioid analgesics in our study (5% of all participants).

A contributor to the lack of consistent adherence to the current guidelines, in other words, the low prevalence of regular analgesic use among older adults who have chronic pain may be explained by the concerns of elderly people, their families, and their physicians regarding side effects or adverse drug reactions. The results of this study showed that a relatively small subset (15%) of those with moderate to severe pain were concerned that they were using too much pain medication and only 6% of participants who reported ever using medication to manage their pain reported having one or more side effects related to the use of pharmacologic pain treatments. It is well known that older adults are susceptible to adverse drug reactions (ADRs) related to nonprescription and prescription analgesics.40 However, our results do not suggest that side effects were a substantial issue in our population.

Another reason that analgesic use among older adults in our study was limited may be because some analgesic medications are ineffective in treating people with moderate to severe pain.5,9,30,31 Our results show that most older adults with moderate to severe pain reported no more than moderate levels of pain relief (41–70%) from their medications and treatments. This is consistent with other reports that chronic pain often does not completely respond to medical treatments.5,9 Although there are various types of analgesic treatments available, no analgesic, whether taken as monotherapy or in combination with other pain medications, is optimal for all patients.5,9 Hence, the AGS panel recommends that pain management in older adult should include both pharmacologic (PS) and non-pharmacologic strategies (NPS).5 Use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is becoming increasingly prevalent and acceptable in older populations.41 Older adults use CAM therapies quite frequently, with 30% to 100% of this age group choosing these options.41,42 Previous data from the Mobilize Boston Study, showed that more than one-third used both pharmacological strategies (PS) and non-pharmacological strategies (NPS).4 In fact, participants reported using NPS more frequently than PS, with 68% reporting using NPS and 49% using PS, with a substantial overlap.4 Therefore, multimodal treatment approaches involving both pharmacological and nonpharmacological pain therapies could be the most effective in managing persistent pain in older populations.

There are some limitations in this study. Firstly, it is possible that some reported analgesic use may have been used for treating acute pain that was not assessed in the Mobilize Boston Study. Secondly, we studied the relationship between analgesic use and chronic pain in the short-term period, the previous 2 weeks. The cross-sectional study design meant that we could not determine changes in patterns of analgesic use and whether participants had switched to other drugs or stopped using analgesics. In addition, we did not know whether the medications were obtained by prescription or taken as a self-treatment. Thirdly, in answering the questions about perceptions and side effects of medications used for pain management, participants may not have considered that psychiatric medications such as anti-depressants may have some impact on pain management. As a result, participants may not have recognized these effects. Lastly, this study included only those who could communicate in English living in the Boston area. This study should be replicated in other populations, including other ethnic and cultural groups.

It is important to note the strengths of this study. The Mobilize Boston Study is a population-based cohort study that had rigorous methods for enrolling older populations in the Boston area. As such, the findings are generalizable to the English-speaking population of older adults without moderate or severe cognitive impairment living in the community in the greater Boston area, and possibly other large metropolitan communities. The Mobilize Boston Study used objective measures, self-report information, and clinical assessments conducted by trained research staff. Moreover, this study had a large sample size drawn from diverse urban and suburban communities.

Conclusion

Many older adults with moderate to severe pain are not using analgesic medications in ways that are consistent with current geriatric guidelines for pain management. Undertreatment of chronic pain in older adults continues to be a common concern, placing older adults at risk for serious consequences. It would be helpful to know whether recent years have brought any improvements in pain management in older adults. Additional research is needed to understand the barriers to effective pain management and self-management in older adults with chronic pain. Future studies should examine barriers to effective pharmacological management of chronic pain in older adults such as lack of adherence, lack of understanding of effective pain self-management strategies, and fears of adverse effects of medications. Lastly, future studies could identify how pharmacological pain management strategies could be related to longitudinal outcomes such as hospitalization, physical disability, falls, emergency visits, and mortality.

Supplementary Material

Fig. 1B.

Report of duration of pain relief among 599 participants reporting chronic pain in the baseline assessment, MOBILIZE Boston cohort, 2005–2008

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging Grant R01AG041525; NIA Research Nursing Home Program Project Grant P01AG004390; and an unrestricted grant from Pfizer, Inc. to support medication data coding. Ms. Nawai’s effort was supported by a Royal Thai Government Scholarship.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Role of the Sponsors: The sponsors were not involved in the data collection, analysis, interpretation of the findings, or in the preparation of this manuscript.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: The Mobilize Boston Study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Hebrew SeniorLife and the collaborating institutions in Boston, including Harvard Medical School, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston University, and the University of Massachusetts Boston (UMASS).

Informed Consent: Participants who were eligible to participate in the Mobilize Boston Study were obtained using informed consent during the baseline home visits.

References

- 1.Helme RD, Gibson SJ. The epidemiology of pain in elderly people. Clin Geriatr Med. 2001;17:417–31. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0690(05)70078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education, Institute of Medicine. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reyes-Gibby CC, Aday L, Cleeland C. Impact of pain on self-rated health in the community-dwelling older adults. Pain. 2002;95:75–82. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(01)00375-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart C, Leveille SG, Shmerling RH, et al. Management of persistent pain in older adults: the MOBILIZE Boston Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:2081–2086. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04197.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Geriatrics Society Panel on Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons. Pharmacological management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1331–1346. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanlon JT, Fillenbaum GG, Ruby CM, et al. Epidemiology of over-the-counter drug use in community dwelling elderly: United States perspective. Drugs Aging. 2001;18:123–131. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200118020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haslam C, Nurmikko T. Pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain in older persons. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3:111–120. doi: 10.2147/cia.s1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLean AJ, Le Couteur DG. Aging biology and geriatric clinical pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev. 2004;56:163–184. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.2.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Auret K, Schug SA. Underutilisation of opioids in elderly patients with chronic pain: approaches to correcting the problem. Drugs Aging. 2005;22:641–654. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200522080-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bressler R, Bahl JJ. Principles of drug therapy for the elderly patient. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:1564–1577. doi: 10.4065/78.12.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leveille SG, Kiel DP, Jones RN, et al. The MOBILIZE Boston Study: design and methods of a prospective cohort study of novel risk factors for falls in an older population. BMC Geriatr. 2008;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samelson EJ, Kelsey JL, Kiel DP, et al. Issues in conducting epidemiologic research among elders: lessons from the MOBILIZE Boston Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:1444–1451. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Escobar JI, Burnam A, Karno M, et al. Use of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) in a community population of mixed ethnicity. Cultural and linguistic artifacts. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1986;174:607–614. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198610000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eaton WW, Muntaner C, Smith C, et al. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: Review and Revision (CESD and CESD–R) In: Maruish ME, editor. The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment. Vol. 3. Mahwah NJ: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vinik AI. Diagnosis and management of diabetic neuropathy. Clin Geriatr Med. 1999;15:293–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klippel JH, Weyand CM, Wortmann R. Primer on the Rheumatic Diseases. Atlanta, GA: Arthritis Foundation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cleeland CS. Measurement of pain by subjective report. In: Chapman CR, Loeser JD, editors. Advances in Pain Research and Therapy, Volume 12: Issues in Pain Measurement. Raven Press; New York: 1989. pp. 391–403. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keller S, Bann CM, Dodd SL, et al. Validity of the brief pain inventory for use in documenting the outcomes of patients with noncancer pain. Clin J Pain. 2004;20:309–318. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200409000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan G, Jensen MP, Thornby JI, et al. Validation of the Brief Pain Inventory for chronic nonmalignant pain. J Pain. 2004;5:133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leveille SG, Jones RN, Kiely DK, et al. Chronic musculoskeletal pain and the occurrence of falls in an older population. JAMA. 2009;302:2214–2221. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eggermont LH, Bean JF, Guralnik JM, et al. Comparing pain severity versus pain location in the MOBILIZE Boston study: chronic pain and lower extremity function. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:763–770. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eggermont LH, Penninx BW, Jones RN, et al. Depressive symptoms, chronic pain, and falls in older community-dwelling adults: the MOBILIZE Boston Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:230–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03829.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Psaty BM, Lee M, Savage PJ, et al. Assessing the use of medications in the elderly: methods and initial experience in the Cardiovascular Health Study. The Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:683–692. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90143-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.IOWA DRUG INFORMATION SERVICE (IDIS) IDID Drug Vocabulary and Thesaurus Description. Homepage of Division of Drug Information Service, College of Pharmacy. University of Iowa (Online); 2012. http://www.uiowa.edu/~idis/dvt_description.pdf. Accessed 1 May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pokela N, Bell JS, Lihavainen K, et al. Analgesic use among community-dwelling people aged 75 years and older: A population-based interview study. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2010;8:233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fillingim RB. Sex, gender, and pain: women and men really are different. Curr Rev Pain. 2000;4:24–30. doi: 10.1007/s11916-000-0006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cepeda MS, Carr DB. Women experience more pain and require more morphine than men to achieve a similar degree of analgesia. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:1464–1468. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000080153.36643.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thakral M, Shi L, Foust JB, et al. Pain quality descriptors in community-dwelling older adults with nonmalignant pain. Pain. 2016;157:2834–2842. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reid MC, Eccleston C, Pillemer K. Management of chronic pain in older adults. BMJ. 2015;350:h532. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCleane G. Pharmacological pain management in the elderly patient. Clin Interv Aging. 2007:637–643. doi: 10.2147/cia.s1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Enthoven WT, Scheele J, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, et al. Analgesic use in older adults with back pain: the BACE study. Pain Med. 2014;15:1704–1714. doi: 10.1111/pme.12515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hersh EV, Pinto A, Moore PA. Adverse drug interactions involving common prescription and over-the-counter analgesic agents. Clin Ther. 2007;29:2477–2497. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griffin MR, Yared A, Ray WA. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acute renal failure in elderly persons. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:488–496. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brune K, Patrignani P. New insights into the use of currently available non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Pain Res. 2015;8:105–18. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S75160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, et al. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: a systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:276–286. doi: 10.7326/M14-2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. Fracture risk associated with the use of morphine and opiates. J Intern Med. 2006;260:76–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soderberg KC, Laflamme L, Moller J. Newly initiated opioid treatment and the risk of fall-related injuries. A nationwide, register-based, case-crossover study in Sweden. CNS Drugs. 2013;27:155–161. doi: 10.1007/s40263-013-0038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller M, Sturmer T, Azrael D, et al. Opioid analgesics and the risk of fractures in older adults with arthritis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:430–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03318.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barber JB, Gibson SJ. Treatment of chronic non-malignant pain in the elderly: safety considerations. Drug Saf. 2009;32:457–474. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200932060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Najm W, Reinsch S, Hoehler F, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among the ethnic elderly. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9:50–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ness J, Cirillo DJ, Weir DR, et al. Use of complementary medicine in older Americans: results from the Health and Retirement Study. Gerontologist. 2005;45:516–524. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.4.516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.