Highlights

-

•

Initial hybrid approach to achieve haemorrhagic and sepsis control is a viable option as a bridge to delayed definitive arterial reconstruction .

-

•

Endovascular stent-grafting provides an alternative treatment strategy to arterial ligation in cases of ruptured mycotic pseudoaneurysms.

-

•

Anticipation of stent-graft infection can allow time to plan for delayed arterial reconstruction.

-

•

Subsequent stent-graft removal and reconstruction can preclude complications of arterial ligation, including claudication and limb-loss.

Abbreviations: IVDU, intravenous drug use; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; CRP, C-reactive protein; CT, computed tomographic; EIA, external iliac artery; cm, centimetre; ITU, intensive treatment unit; DSA, digital subtraction angiogram

Keywords: Case report, Treatment, Mycotic pseudoaneurysm, IVDU

Abstract

Introduction

Ruptured mycotic pseudoaneurysms are one of the ways IVDU patients can present in extremis. The principles of treatment include arterial ligation for haemorrhage control but can leave patients vulnerable subsequent limb ischaemia.

Presentation of case

We report a female IVDU presenting with abdominal pain and sepsis. Imaging demonstrated haemorrhage from an external iliac pseudoaneurysm. A two-staged hybrid approach with initial endografting and debridement for sepsis-control followed by delayed endograft removal and arterial reconstruction was successfully undertaken.

Discussion

The primary use of endovascular techniques to control haemorrhage in unstable patients is a useful adjunct to treat ruptured mycotic pseudoaneurysms in IVDU patients with delayed removal and arterial reconstruction.

Conclusion

We have shown a successful outcome in managing a challenging patient using endovascular techniques as a bridge to definitive arterial reconstruction. This circumvents traditional approaches including primary arterial ligation, which carry a risk of limb-loss.

1. Introduction

Mycotic pseudoaneurysm formation and subsequent rupture in intravenous drug users (IVDU) can be potentially devastating to patients, or result in death [1], [2]. Various treatment strategies for haemorrhage control have been reported with most advocating arterial ligation [3], [4]. Other strategies include arterial ligation with immediate arterial reconstruction or as we report, endovascular stent-graft insertion. This report is compliant with the SCARE criteria and PROCESS guidelines published on case report submissions [5], [6]. Our case adds to the literature by being, we believe, one of two published reports in the literature describing the use of emergency stent-grafting and subsequent (delayed) arterial reconstruction after sepsis–control, and the only one describing its utility in the IVDU setting [7].

2. Case report

A 37-year old Caucasian female IVDU presented to our emergency department with a one-week history of fever with worsening left flank, groin and abdominal pain. She was normotensive, but tachycardic and tachypnoeic at presentation. Examination revealed scarred groins, discharging purulent fluid. Other physical findings were unremarkable. Her medical history included Hepatitis C and she admitted to a heroin addiction. She had no known allergies.

2.1. Investigations

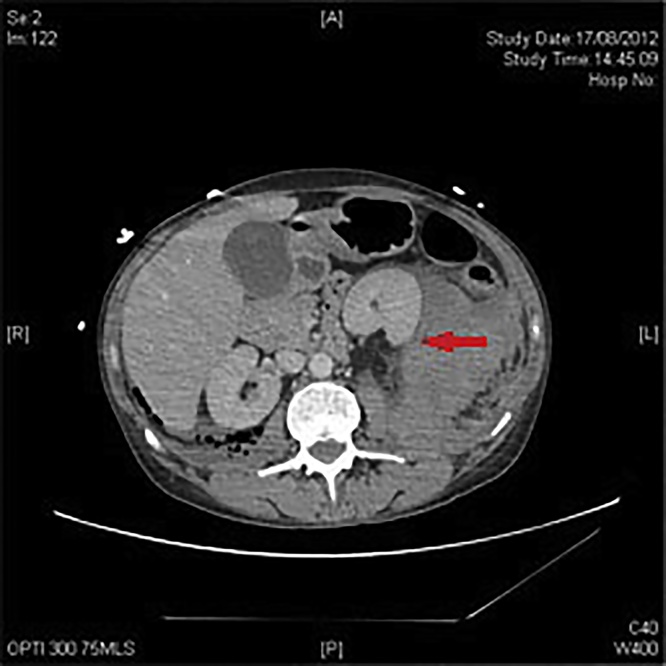

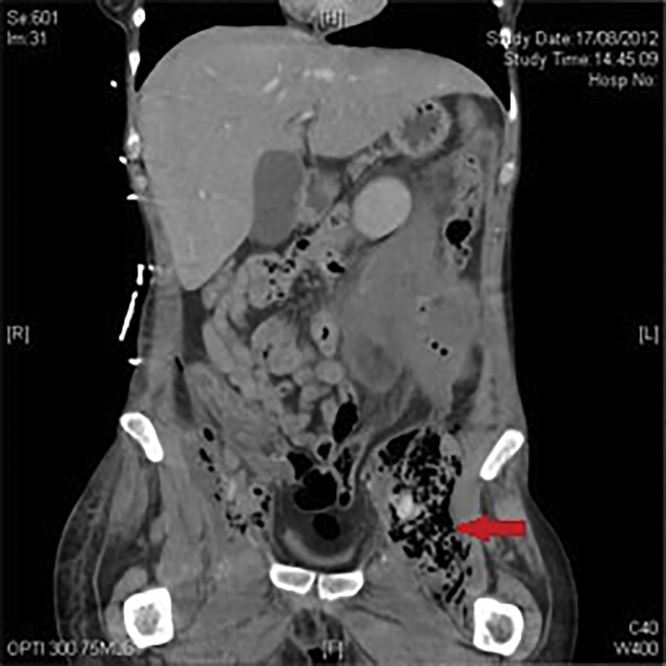

Laboratory investigations showed a marked leucocytosis (38.0 × 109/L), elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) (350 mg/L) and normocytic anaemia (10.0 g/dL). A computed tomographic (CT) angiogram of her abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a medially displaced left kidney with a 10 cm retroperitoneal, loculated collection communicating with the left external iliac artery (EIA) whose appearances suggested pseudoaneurysm formation with recent haemorrhage (Fig. 1, Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Retroperitoneal haematoma and a medially displaced left kidney.

Fig. 2.

Extensive gas locules in the left iliopsoas region.

2.2. Treatment

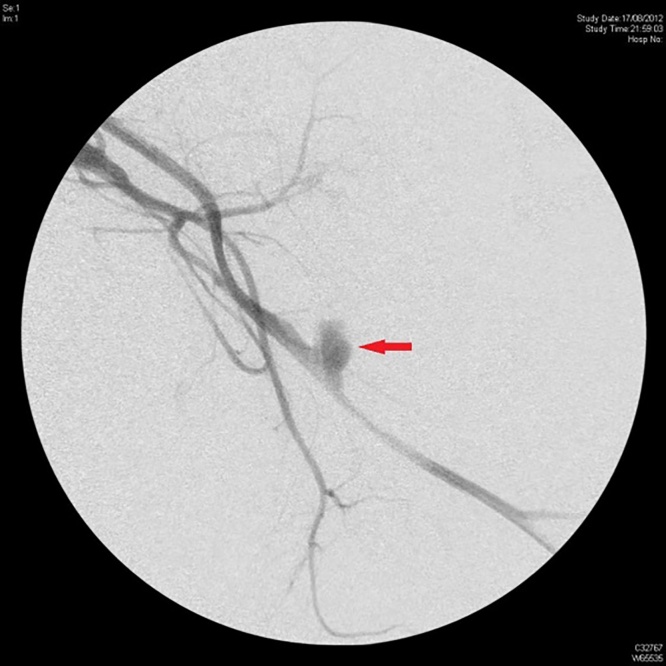

A decision was made to control haemorrhage using endovascular techniques and subsequently plan for delayed arterial reconstruction. She was stabilised and transferred to theatre, where surgical cut-down to the left popliteal artery was undertaken to provide access for Bard Fluency® Plus (covered) Vascular Stent Graft (7 mm × 6 cm) insertion via retrograde puncture (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). Prior to arterial closure, a distal popliteal embolectomy was also performed. Diagnostic laparoscopy excluded occult intra-peritoneal contamination and bilateral Rutherford-Morrison incisions were then made to drain the retroperitoneum. Extensive infected clot was removed from both retroperitoneal spaces, lavage performed and drains placed. Wounds were packed with betadine-soaked gauze in anticipation of further wound toilet and debridement. She was transferred to the intensive treatment unit (ITU) and returned to theatre at 24-h for a re-look. Further infected clot was evacuated and the wound re-packed. This cycle of wound toilet continued for a further 48 h at which point wounds were closed. She remained on ITU for a further ten days and was treated with appropriate antibiotics (intra-operative cultures grew Staphylococcus sp. Diphtheroids sp., anaerobic gram positive cocci and aerobic gram positive bacilli). She was discharged home on antibiotics after a three-week in-patient stay.

Fig. 3.

Intra-operative digital subtraction angiogram (DSA) demonstrating extravasation of contrast from the ruptured external iliac artery mycotic pseudoaneurysm.

Fig. 4.

Intra-operative digital subtraction angiogram (DSA) showing control of haemorrhage using a covered stent-graft.

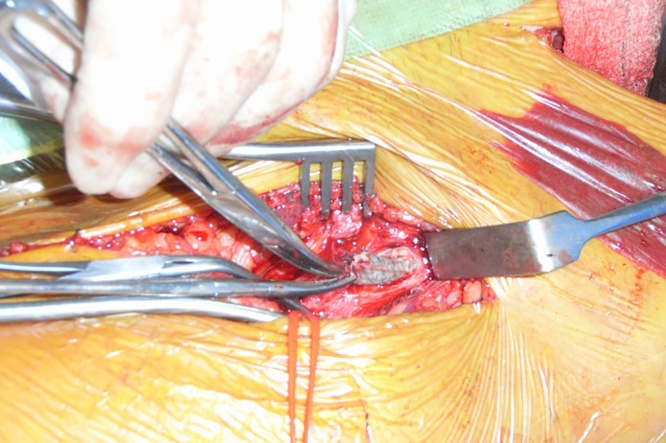

On out-patient follow-up the left-sided incision continued to discharge pus, and CT imaging demonstrated peri-stent-graft infection. Stent-graft removal with arterial reconstruction using an autologous conduit was planned. Pre-operative vein-mapping identified the ipsilateral great saphenous vein (GSV) as a suitable conduit. Five-months post initial surgery she underwent a left-sided ilio-femoral reverse-GSV bypass graft and removal of the stent-graft (Fig. 5). Post-operatively, she had palpable pedal pulses and made a good recovery. She was discharged six days later on a six-week course of antibiotics.

Fig. 5.

Removal of the infected endoprosthesis.

3. Outcome/follow-up

At her last (two-year) follow-up she continued to do well, with palpable pedal pulses and was subsequently discharged from review. Additionally, she had made and retained contact with our alcohol and drug liaison services and successfully refrained from relapsing into drug use.

4. Discussion

Traditionally, treatment of mycotic pseudoaneurysms in the IVDU population has focussed on arterial ligation but this renders the (often young) patient-group vulnerable to on-going problems such as claudication or ischaemia requiring major-limb amputation [3], [4]. In the endovascular era, hybrid procedures with the use of endoluminal devices to achieve haemorrhagic control is a useful adjunct but harbours the significant risk of stent-graft infection requiring delayed excision with or without arterial reconstruction [7], [8].

The common femoral artery is reportedly the most common site of inadvertent injection in IVDUs, presumably due to its large lumen and the relative accessibility of the common femoral vein in the groin [9]. All patients with a known history of IVDU and groin swelling should be presumed to have a pseudoaneurysm until proven otherwise. Our case presented with loin/abdominal pain and early signs of sepsis consistent with a retroperitoneal abscess, confirmed by the prompt availability of CT-imaging. Mycotic pseudoaneurysms, cutaneous infections and abscesses, or localised cellulitis, have been found to occur in up to 65% of addicts which can be the result of both contaminated drugs and un-sterile injection paraphernalia in conjunction with poor hygiene [10]. The commonest pathogen in such cases is Staph. aureus although other gram-positive cocci and anaerobes have also been reported in the literature [11].

Strategies to treat patients presenting with pseudoaneurysms include control of haemorrhage and drainage of associated collections. Traditionally this has taken the form of surgical ligation of the artery proximal and distal to the aneurysmal segment, This strategy risks rendering the distal limb ischaemic, particularly if the profunda femoris is diseased and major-limb amputation rates in the literature are reported to be as high as 20% [10]. Other strategies include ligation and immediate revascularisation with anatomic, or extra-anatomic prosthetic bypass grafting but this is carries a high risk of graft infection. The use of an autologous conduit to reduce this risk is often hampered by the lack of suitable vein in IVDUs as their injecting history often leaves their veins collapsed and chronically scarred [12].

The use of an endograft in an infected field carries a risk of graft-infection which cannot always be mitigated by long-term antimicrobial therapy. As such, hybrid procedures can certainly act as a ‘bridge’ to more definitive surgery, including delayed-revascularisation, once the patient’s condition has been stabilised and infection controlled.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding source

None.

Ethical approval

N/A.

Consent

The patient gave verbal informed consent to the write-up of this case report. Attempts to contact the patient for written consent failed as the patient was no longer contactable at the given address on record.

Author contribution

M Ahmad: Data collection, write up.

YW Poh: Data collection, write up.

CHE Imray: Study concept, write-up.

Guarantor

Professor Chris Imray PhD FRCS FRCP FRGS.

Consultant Vascular and Renal Transplant Surgeon.

Chair of the Vascular Society Research Committee.

Director of Research, Development & Innovation, UHCW NHS Trust.

References

- 1.Valentine R., Turner W.W. Acute vascular insufficiency due to drug injection. In: Rutherford R.B., editor. Vascular Surgery. 4th ed. WB Saunders; Philadelphia: 1995. pp. 846–853. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coughlin P.A., Mavor A.I.D. Arterial consequences of recreational drug use. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2006;32(4):389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qiu J., Zhou W., Zhou W., Tang X., Yuan Q., Zhu X. The treatment of infected femoral artery pseudoaneurysms secondary to drug abuse: 11 years of experience at a single institution. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2016;36:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2016.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saini N., Luther A., Mahajan A., Joseph A. Infected pseudoaneurysms in intravenous drug abusers: ligation or reconstruction? Int. J. Appl. Basic Med. Res. 2014;4(Suppl. 1):S23–S26. doi: 10.4103/2229-516X.140715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saeta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P. The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Rajmohan S., Barai I., Orgill D.P. Preferred reporting of case series in surgery; the PROCESS guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;36:319–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klonaris C., Katsargyris A., Vasileiou I., Markatis F., Liapis C.D., Bastounis E. Hybrid repair of ruptured infected anastomotic femoral pseudoaneurysms: emergent stent-graft implantation and secondary surgical debridement. J. Vasc. Surg. 2009;49(4):938–945. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Psathas E., Lioudaki S., Karantonis F.-F., Charalampoudis P., Papadopoulos O., Klonaris C. Management of a complicated ruptured infected pseudoaneurysm of the femoral artery in a drug addict. Case Rep. Vasc. Med. 2012;2012:434768. doi: 10.1155/2012/434768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geelhoed G.W., Joseph W.L. Surgical sequelae of drug abuse. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 2016;1974139(5):749–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mittapalli D., Velineni R., Rae N., Howd A., Suttie S.A. Necrotizing soft tissue infections in intravenous drug users: a vascular surgical emergency. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2015;49(5):593–599. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Del Giudice P. Cutaneous complications of intravenous drug abuse. Br. J. Dermatol. 2004;150(1):1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klonaris C., Katsargyris A., Papapetrou A., Vourliotakis G., Tsiodras S., Georgopoulos S. Infected femoral artery pseudoaneurysm in drug addicts: the beneficial use of the internal iliac artery for arterial reconstruction. J. Vasc. Surg. 2007;45(3):498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]