Abstract

Aim

The objective was to quantify dose calculation accuracy of TiGRT TPS for head and neck region in radiotherapy.

Background

In radiotherapy of head and neck cancers, treatment planning is difficult, due to the complex shape of target volumes and also to spare critical and normal structures. These organs are often very near to the target volumes and have low tolerance to radiation. In this regard, dose calculation accuracy of treatment planning system (TPS) must be high enough.

Materials and methods

Thermoluminescent dosimeter-100 (TLD-100) chips were used within RANDO phantom for dose measurement. TiGRT TPS was also applied for dose calculation. Finally, difference between measured doses (Dmeas) and calculated doses (Dcalc) was obtained to quantify the dose calculation accuracy of the TPS at head and neck region.

Results

For in-field regions, in some points, the TiGRT TPS overestimated the dose compared to the measurements and for other points underestimated the dose. For outside field regions, the TiGRT TPS underestimated the dose compared to the measurements. For most points, the difference values between Dcalc and Dmeas for the in-field and outside field regions were less than 5% and 40%, respectively.

Conclusions

Due to the sensitive structures to radiation in the head and neck region, the dose calculation accuracy of TPSs should be sufficient. According to the results of this study, it is concluded that the accuracy of dose calculation of TiGRT TPS is enough for in-field and out of field regions.

Keywords: Head and neck region, Radiotherapy, Dose calculation accuracy, Treatment planning system

1. Background

Head and neck cancers (HNCs) consist of the oral cavity, nasopharynx, oropharynx, larynx, hypopharynx, nasal cavity, salivary glands, par nasal sinuses and thyroid cancers.1 These cancers arise from digestive tracts, mucous lining of respiratory, lymph nodes, and salivary glands.2 Radiotherapy is applied as a HNC treatment modality either alone or in combination with chemotherapy or surgery.1, 3 One of the techniques in radiation therapy of head and neck cancer is the wedged field technique.4 Wedge filters are commonly applied to modify the dose distribution and make it uniform within the target volume.5, 6, 7, 8

Treatment planning for head and neck cancers is difficult, due to the complex shape of target volumes and also to spare critical organs such as the parotid glands, mandible, spinal cord, brainstem, and normal structures. These organs often are near to the target volumes and have low tolerance to radiation.4 Hence, special attention needs to deliver dose to the tumor, while to keep the dose of the organs at risk as low as possible. To achieve this goal, treatment planning systems (TPSs) should calculate the dose exactly.

There are several studies relevant to dose calculation accuracy of different algorithms and TPSs in radiotherapy; however, most of them were carried out in a water phantom and/or in regions other than the head and neck.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19

2. Aim

To the best of our knowledge, there is no investigation on the accuracy of dose calculations of TiGRT TPS in head and neck region. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the accuracy of dose calculations in this region for TiGRT TPS in the presence of wedged fields.

3. Methods and materials

3.1. Treatment planning and irradiation of the phantom

A computed tomography scan of the head and neck region of a RANDO phantom (Phantom Laboratory, NY, USA) was taken to produce a treatment plan. The Rando phantom is made of bone-equivalent, soft tissue-equivalent or lung-equivalent tissues. Each slice of the phantom has holes which are plugged with bone-equivalent, soft-tissue-equivalent or lung-equivalent pins which can be replaced by TLD holder pins.20 The images of the Rando phantom were transported to TiGRT TPS version 1.2 (LinaTech, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). According to user's manual of TiGRT TPS, the TPS uses a three dimensional photon dose calculation algorithm based on full scatter convolution (FSC), developed to facilitate accurate and fast calculations. According to the manual, this algorithm separates the absorbed dose (D) in a given point into the primary dose (Dp) and the scatter dose (Ds):

| (1) |

The primary dose Dp () is obtained based on the convolution algorithm, using the following formula:

| (2) |

where is photon fluence at the surface of a ray passing through the surface to point and denotes the electron transport kernel, explaining the dose distribution around the primary interaction site of the photon. This demonstrates that the electron transport modeling by this algorithm has been taken into account, and the electron dose deposition kernel can be scaled for heterogeneities such as lung, bone and air cavities. Finally, V′ states the differential calculation volume at point . The scatter dose is derived from the following convolution equation:

| (3) |

In FSC algorithm, multiple scattering of photons is discarded and is the first scatter fluence kernel. This kernel can be derived from the electron transport kernel.

In this study, two lateral parallel opposed fields were planned, in which one of them was wedge field and another was open field. A source axis distance technique was applied to deliver 200 cGy dose to the selected point (the center slice No. 5 of the RANDO phantom). The treatment fields covered the slices of No. 2–7 of the RANDO phantom. The irradiated area on the RANDO phantom is shown in Fig. 1. Before irradiation, the thermoluminescent detector-100 (TLD-100) chips were placed in special points of the RANDO phantom. The RANDO phantom was irradiated based on the treatment plan with 6 MV X-rays emitted from a Siemens Primus accelerator (Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany). Doses received by the TLD-100 chips were measured and compared with doses calculated by TPS.

Fig. 1.

Irradiated area on the RANDO phantom.

It is notable that the dose calculation in the indicated points of the phantom (Dcalc) was as one point. The points of dose calculation by the TPS were considered centers of TLDs.

3.2. Calibration of applied dosimeters and dosimetric method

Readout and analysis of TLD-100 was carried out in the medical physics research center (Mashhad, Iran), which has a specific protocol for TLD analysis. TLD-100 produced by Harshaw Company that made of LiF, Mg, and Ti with the size of 3 mm × 3 mm and thickness of 0.9 mm were used in this study. TLD-100 chips have a reproducibility of approximately ±1.5% (1 SD). TLD-100 chips were calibrated as mentioned in previous works.21, 22, 23 Briefly, 15 TLD-100 chips were placed in a Perspex holder. This holder was located on a 30 cm × 30 cm × 20 cm water equivalent phantom to create a full scatter conditions. A 15 mm water equivalent slab was placed on the holder to make a build-up region. First, they were irradiated to determine their individual efficiency correction coefficient (ECC). Then, they were irradiated with 50 cGy and readout by Harshaw reader to determine reader calibration factor. Finally, all of the TLD-100 chips were irradiated with 50 cGy and their individual ECC were determined. 47 dosimeters were placed in the different regions of slices of No. 4, 5, 8 and 9 of the RANDO phantom. 3 dosimeters were used to measure the background radiation.

It is noteworthy that the effective point of measurement for the TLD-100 chips was considered at the middle of its height. Also, to have the high accuracy of dosimetry results, measurements were repeated 3 times.

3.3. Analysis of results

For analysis of the results, TRS 43024 and TECDOC 154025 protocols were applied. These protocols provide information on quality assurance (QA) of TPSs. According to these protocols, the difference between the calculated and the measured dose is defined based on Eq. (4):

| (4) |

where Dmeas and Dcalc are the measured dose by TLD-100 chips and the calculated dose by TPS, respectively. Finally, the difference values were obtained for in-field and outside field regions and were compared to the tolerance limit suggested in TRS 430 and TECDOC 1540 protocols.

4. Results

Slices of No. 4, 5, 8 and 9 of RANDO phantom were selected to assess the accuracy of dose calculations in head and neck region; as slices of No. 4 and 5 were used to assess the in-field regions and slices of No. 8, 9 and some points in slices of No. 4 and 5 were applied to evaluate the outside field regions.

In these slices, doses measured by TLD-100 chips were compared with corresponding values calculated by TiGRT TPS. These results are illustrated in the following tables. Table 1, Table 2 list the Dmeas, the Dcalc, and the difference between Dmeas and Dcalc in the selected points of slices of No. 4 and 5 of RANDO phantom, respectively. It is noteworthy that the bolded digits in Table 1, Table 2 are the measured/calculated doses obtained for the outside field regions.

Table 1.

The measured dose (Dmeas), the calculated dose (Dcalc) and the differences between the Dmeas, the Dcalc in the selected points for slice No. 4 of RANDO phantom.

| No. TLD | Location of TLD | Dmeas (cGy) | Dcalc (cGy) | Difference between Dcalc and Dmeas (δ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Out of field | 16.81 | 12.73 | −24.25 |

| 2 | Out of field | 17.27 | 13.88 | −19.58 |

| 3 | Out of field | 16.69 | 14.08 | −15.72 |

| 4 | In field | 208.27 | 197.81 | −5.02 |

| 5 | In field | 189.08 | 193.35 | 2.26 |

| 6 | In field | 194.65 | 194.85 | 0.10 |

| 7 | In field | 187.92 | 195.46 | 4.01 |

| 8 | In field | 201.15 | 197.00 | −2.06 |

| 9 | In field | 199.54 | 196.04 | −1.75 |

| 10 | In field | 195.96 | 193.35 | −1.33 |

| 11 | In field | 208.42 | 200.65 | −3.73 |

| 12 | In field | 207.42 | 209.27 | 0.89 |

| 13 | In field | 196.62 | 205.96 | 4.75 |

| 14 | In field | 200.23 | 201.54 | 0.65 |

| 15 | In field | 198.19 | 204.04 | 2.95 |

| 16 | Penumbra | 40.19 | 24.77 | −38.37 |

| 17 | Penumbra | 53.23 | 31.69 | −40.46 |

| 18 | Penumbra | 90.77 | 60.88 | −32.92 |

| 19 | Penumbra | 129.88 | 115.85 | −10.81 |

Table 2.

The measured dose (Dmeas), the calculated dose (Dcalc) and the differences between the Dmeas, the Dcalc in the selected points for slice No. 5 of RANDO phantom.

| No. TLD | Location of TLD | Dmeas (cGy) | Dcalc (cGy) | Difference between Dcalc and Dmeas (δ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | Out of field | 16.35 | 14.27 | −12.76 |

| 21 | Out of field | 14.96 | 14.23 | −4.93 |

| 22 | In field | 192.92 | 191.38 | −0.80 |

| 23 | In field | 185.85 | 192.27 | 3.46 |

| 24 | In field | 199.19 | 193.54 | −2.84 |

| 25 | In field | 179.12 | 190.85 | 6.55 |

| 26 | In field | 190.08 | 193.54 | 1.82 |

| 27 | In field | 191.15 | 195.46 | 2.25 |

| 28 | In field | 194.77 | 195.85 | 0.55 |

| 29 | In field | 183.12 | 187.54 | 2.42 |

| 30 | In field | 199.77 | 210.46 | 5.35 |

| 31 | In field | 192.69 | 203.42 | 5.57 |

| 32 | In field | 196.88 | 202.88 | 3.05 |

| 33 | In field | 195.50 | 200.12 | 2.36 |

| 34 | In field | 32.35 | 34.42 | 6.36 |

| 35 | In field | 56.42 | 54.04 | −4.22 |

| 36 | In field | 96.19 | 98.81 | 2.72 |

| 37 | In field | 132.46 | 129.92 | −1.92 |

| 38 | Out of field | 10.38 | 9.54 | −8.11 |

| 39 | Out of field | 11.35 | 10.23 | −9.94 |

Fig. 2, Fig. 3 show the location of TLDs in slices No. 4 and 5 of RANDO phantom (a) and image of these slices of RANDO phantom and the location of points corresponding to the measured points in TiGRT TPS (b), respectively.

Fig. 2.

The location of TLDs in slice No. 4 of RANDO phantom (a) and image of slice No. 4 of RANDO phantom and the location of points corresponding to the measured points in TiGRT TPS (b).

Fig. 3.

The location of TLDs in slice No. 5 of RANDO phantom (a) and image of slice No. 5 of RANDO phantom and the location of points corresponding to the measured points in TiGRT TPS (b).

Fig. 4 illustrates the dose differences (%) between the measured doses by TLD-100 and the calculated doses using TiGRT TPS for in-field regions.

Fig. 4.

The dose differences (%) between the measured doses by TLD-100 and the calculated doses using TiGRT TPS for in-field regions.

Table 3, Table 4 list the Dmeas, the Dcalc, and the difference between Dmeas and Dcalc in the selected points of slices of No. 8 and 9 of RANDO phantom for out of field regions, respectively.

Table 3.

The measured dose (Dmeas), the calculated dose (Dcalc) and the differences between the Dmeas, the Dcalc in the selected points for slice No. 8 of RANDO phantom for out of field regions.

| No. TLD | Dmeas (cGy) | Dcalc (cGy) | Difference between Dcalc and Dmeas (δ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | 28.62 | 19.69 | −31.15 |

| 41 | 27.19 | 22.69 | −16.60 |

| 42 | 36.73 | 21.73 | −40.86 |

| 43 | 34.15 | 24.88 | −27.15 |

Table 4.

The measured dose (Dmeas), the calculated dose (Dcalc) and the differences between the Dmeas, the Dcalc in the selected points for slice No. 9 of RANDO phantom for out of field regions.

| No. TLD | Dmeas (cGy) | Dcalc (cGy) | Difference between Dcalc and Dmeas (δ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 44 | 7.96 | 5.81 | −26.97 |

| 45 | 8.19 | 6.46 | −21.15 |

| 46 | 7.50 | 7.12 | −4.97 |

| 47 | 7.65 | 7.00 | −8.62 |

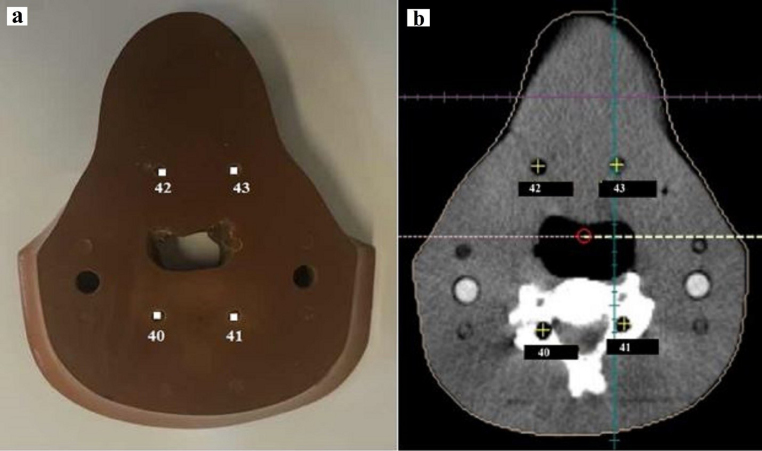

Fig. 5, Fig. 6 show the location of TLDs in slices of No. 8 and 9 of RANDO phantom (a) and image of these slices of RANDO phantom and the location of points corresponding to the measured points in TiGRT TPS (b), respectively.

Fig. 5.

The location of TLDs in slice No. 8 of RANDO phantom (a) and image of slice No. 8 of RANDO phantom and the location of points corresponding to the measured points in TiGRT TPS (b).

Fig. 6.

The location of TLDs in slice No. 9 of RANDO phantom (a) and image of slice No. 9 of RANDO phantom and the location of points corresponding to the measured points in TiGRT TPS (b).

Fig. 7 illustrates the dose differences (%) between the measured doses by TLD-100 and the calculated doses using TiGRT TPS for outside field regions.

Fig. 7.

The dose differences (%) between the measured doses by TLD-100 and the calculated doses using TiGRT TPS for outside field regions.

5. Discussion

In this research, the accuracy of dose calculation in the head and neck region for TiGRT TPS (version 1.2) using TLD-100 was quantified; as both of the in-field and outside field regions were evaluated.

The results show that for in-field regions, in some points, the TiGRT TPS overestimated the dose compared to the measured doses by TLD-100, and for other points underestimated the dose. For outside field regions, the TiGRT TPS underestimated the dose compared to the measured doses by TLD-100. Our results related to out of field regions were consistent to several studies26, 27, 28; as results of these studies showed that TiGRT TPS underestimated the dose of out-of-field regions for most points.

According to protocols of TECDOC 1540 and TRS 430 that provide information on QA of TPSs, tolerance limit for more complex geometry (i.e. inhomogeneous phantom with wedge field) and in-field regions (i.e. high dose-small dose gradient regions) is 4% and in outside field regions (i.e. low dose-small dose gradient regions) is 50%. The results of this study showed that for most points, the difference values between Dcalc and Dmeas (%) for the in-field regions were within the tolerance limit. Farhood et al.28 assessed accuracy of dose calculation of TiGRT TPS for physical wedge fields. They concluded that the accuracy of dose calculation of mentioned TPS for physical wedged fields in the central axis, off-axis, and build-up regions is adequate. Mahmoudi et al.27 evaluated the accuracy of photon dose calculation in radiotherapy of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Their results showed that accuracy of dose calculation of TiGRT TPS in the presence of heterogeneity, shield, and interfaces is inadequate in compared to Monte Carlo simulation data. The results of our study were consistent with results of the above-mentioned studies. Also, the findings demonstrated that for most points, the difference values between Dcalc and Dmeas (%) for the out of field regions were within the tolerance limit. In a study on the accuracy of dose calculation of TiGRT TPS for physical wedged fields in water phantom, the results showed that accuracy of dose calculation of this TPS is insufficient for out-of-field regions.28 The results of our study were inconsistent with their results that this can be due to complexity geometry of our study compared to their study (i.e. assessment in RANDO phantom vs. water phantom). In another study, Bahreyni Toossi et al.26 evaluated accuracy of dose calculations for outside field in breast region. They showed that TiGRT TPS compared to TLD-measured dose generally underestimate the dose of outside points; as the mean underestimation of doses of outside field was 39%. Their results were consistent with results of our study.

Since in the head and neck region, there are several sensitive structures to radiation with low dose tolerances, considerable attention must be paid to treatment planning of this area. Hence, QA of TPSs for treatment planning of tumors in head and neck region is very important.

It is noteworthy that application of TLD is accepted as a tool for QA in radiation therapy. TLDs have a number of advantages such as high sensitivity, small physical size, and tissue equivalence.29 Some studies have applied TLDs for QA of TPSs.26, 30, 31, 32

There are several limitations in the present study. This research was investigated only for 6 MV photons and for a special geometry (i.e., head and neck region with wedge field).

For future research, evaluation of the dose calculation accuracy of the other TPS for head and neck or other body regions will be interesting.

6. Conclusions

Due to the sensitive structures to radiation in the head and neck region, the dose calculation accuracy of TPSs should be sufficient. In this study, the accuracy of dose calculations of TiGRT TPS in this region was investigated. The findings demonstrated that for the most points, the accuracy of dose calculation of TiGRT TPS is within tolerance limit for in-field and out of field regions.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Financial disclosure

This work was financially supported by the office of vice president for research of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences.

References

- 1.Mercieca-Bebber R.L., Perreca A., King M. Patient-reported outcomes in head and neck and thyroid cancer randomised controlled trials: a systematic review of completeness of reporting and impact on interpretation. Eur J Cancer. 2016;56:144–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar S.S., Vivekanandan N., Sriram P. A study on conventional IMRT and RapidArc treatment planning techniques for head and neck cancers. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2012;17(3):168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorenc M., Kozjek N.R., Strojan P. Malnutrition and cachexia in patients with head and neck cancer treated with (chemo) radiotherapy. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2015;20(4):249–258. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halperin E.C., Brady L.W., Wazer D.E., Perez C.A. 6th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2013. Principles and practice of radiation oncology. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maqbool M. Determination of transfer functions of MCP-200 alloy using 6 MV photon beam for beam intensity modulation. J Mech Med Biol. 2004;4(3):305–310. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maqbool M., Ahmad I. Spectroscopy of gadolinium ion and disadvantages of gadolinium impurity in tissue compensators and collimators, used in radiation treatment planning. J Spectrosc. 2007;21(4):205–210. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kutcher G.J., Burman C., Mohan R. Compensation in three-dimensional non-coplanar treatment planning. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;20(1):127–133. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90148-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones A.O., Das I.J., Jones F.L., Jr. A Monte Carlo study of IMRT beamlets in inhomogeneous media. Med Phys. 2003;30(3):296–300. doi: 10.1118/1.1539040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akino Y., Das I.J., Bartlett G.K., Zhang H., Thompson E., Zook J.E. Evaluation of superficial dosimetry between treatment planning system and measurement for several breast cancer treatment techniques. Med Phys. 2013;40(1):011714. doi: 10.1118/1.4770285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutonjski L., Petrović B., Baucal M. Dosimetric verification of radiotherapy treatment planning systems in Serbia: national audit. Radiat Oncol. 2012;7(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-7-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muhammad W., Maqbool M., Shahid M. Assessment of computerized treatment planning system accuracy in calculating wedge factors of physical wedged fields for 6 MV photon beams. Phys Med. 2011;27(3):135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmp.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howell R.M., Scarboro S.B., Kry S., Yaldo D.Z. Accuracy of out-of-field dose calculations by a commercial treatment planning system. Phys Med Biol. 2010;55(23):6999. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/55/23/S03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gossman M.S., Bank M.I. Dose-volume histogram quality assurance for linac-based treatment planning systems. J Med Phys. 2010;35(4):197. doi: 10.4103/0971-6203.71759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bragg C.M., Conway J. Dosimetric verification of the anisotropic analytical algorithm for radiotherapy treatment planning. Radiother Oncol. 2006;81(3):315–323. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Esch A., Tillikainen L., Pyykkonen J. Testing of the analytical anisotropic algorithm for photon dose calculation. Med Phys. 2006;33(11):4130–4148. doi: 10.1118/1.2358333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fogliata A., Vanetti E., Albers D. On the dosimetric behaviour of photon dose calculation algorithms in the presence of simple geometric heterogeneities: comparison with Monte Carlo calculations. Phys Med Biol. 2007;52(5):1363. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/52/5/011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Venselaar J., Welleweerd H. Application of a test package in an intercomparison of the photon dose calculation performance of treatment planning systems used in a clinical setting. Radiother Oncol. 2001;60(2):203–213. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(01)00304-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farhood B., Bahreyni Toossi M.T., Ghorbani M., Salari E., Knaup C. Assessment the accuracy of dose calculation in build-up region for two radiotherapy treatment planning systems. J Cancer Res Ther. 2017 doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.176421. [in press]. Available from: http://www.cancerjournal.net/aheadofprint.asp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Özgüven Y., Yaray K., Alkaya F., Yücel B., Soyuer S. An institutional experience of quality assurance of a treatment planning system on photon beam. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2014;19(3):195–205. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Available from: http://www.rsdphantoms.com/rt_art.htm.

- 21.Soleymanifard S., Bahreyni Toossi M.T., Khosroabadi M., vejdani Noghreiyan A., Shahidsales S., Tabrizi F.V. Assessment of skin dose modification caused by application of immobilizing cast in head and neck radiotherapy. Australas Phys Eng Sci Med. 2014;37(3):535–540. doi: 10.1007/s13246-014-0283-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soleymanifard S., Aledavood S.A., Noghreiyan A.V., Ghorbani M., Jamali F., Davenport D. In vivo skin dose measurement in breast conformal radiotherapy. Contemp Oncol (Pozn) 2015;19:1–4. doi: 10.5114/wo.2015.54396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bahreyni Toossi M.T., Sabet L.S., Soleymanifard S., Anvari K., Bakhshizadeh M. A comparison of the doses received by normal cranial tissues during different simple model conventional radiotherapeutic approaches to pituitary tumours. Australas Phys Eng Sci Med. 2016;39(2):517–524. doi: 10.1007/s13246-016-0451-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andreo P., Cramb J., Fraass B. International Atomic Energy Agency; Vienna: 2004. Commissioning and quality assurance of computerized planning systems for radiation treatment of cancer, technical report series 430. [Google Scholar]

- 25.International Atomic Energy Agency . International Atomic Energy Agency; Vienna: 2007. Specification and Acceptance Testing of Radiotherapy Treatment Planning Systems, TECDOC No 1540. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bahreyni Toossi M.T., Soleymanifard Sh., Farhood B., Mohebbi Sh., Davenport D. Assessment of accuracy of out-of-field dose calculations by TiGRT treatment planning system in radiotherapy. J Cancer Res Ther. 2017 doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.176423. [in press]. Available from: http://www.cancerjournal.net/aheadofprint.asp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahmoudi G., Farhood B., Shokrani P., Amouheidari A., Atarod M. Evaluation of the photon dose calculation accuracy in radiation therapy of malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Cancer Res Ther. 2017 doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.187284. [in press]. Available from: http://www.cancerjournal.net/aheadofprint.asp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farhood B., Bahreyni Toossi M.T., Soleymanifard S. Assessment of dose calculation accuracy of TiGRT treatment planning system for physical wedged fields in radiotherapy. Iran J Med Phys. 2016;13(3):146–153. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rivera T. Thermoluminescence in medical dosimetry. Appl Radiat Isot. 2012;71:30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oinam A.S., Singh L. Verification of IMRT dose calculations using AAA and PBC algorithms in dose buildup regions. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2010;11(4):3351. doi: 10.1120/jacmp.v11i4.3351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baird C.T., Starkschall G., Liu H.H., Buchholz T.A., Hogstrom K.R. Verification of tangential breast treatment dose calculations in a commercial 3D treatment planning system. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2001;2(2):73–84. doi: 10.1120/jacmp.v2i2.2616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramsey C.R., Seibert R.M., Robison B., Mitchell M. Helical tomotherapy superficial dose measurements. Med Phys. 2007;34(8):3286–3293. doi: 10.1118/1.2757000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]