Abstract

This study investigates the relationship between religious influence and sexual expression in older Americans, with specific attention to gender. Using the National Social Life, Health and Aging Project, a nationally-representative survey of older adults, we create a composite measure of religious influence on sexual expression using Latent Class Analysis. We find more variability within denominations than between in terms of membership in the high-influence class; this indicates that religious influence on sexual expression is diverse within faiths. We show that religious influence is associated with higher self-reported satisfaction with frequency of sex, as well as higher physical and emotional satisfaction with sex, but only for men. Men are also significantly more likely than women to report that they would only have sex with a person they love. These results persisted in the presence of controls for demographic characteristics, religious affiliation, church attendance, intrinsic religiosity, political ideology, and functional health.

Keywords: Sexuality, Religion, Older adulthood, Latent Class Analysis

INTRODUCTION

Religion can have a strong impact on an individual’s normative orientation towards sex – his or her ideas about where, how, and with whom sex should take place (Laumann, Gagnon, Michael, & Michaels, 1994). Sociologists of religion often describe these normative orientations as constraints on sexual expression, producing greater control over sexual impulses (DeLamater, 1989; Granger & Price, 2009; Gyimah, Tenkorang, Takyi, Adjei, & Fosu, 2010; Haglund & Fehring, 2010; Simons, Burt, & Peterson, 2009). Researchers and popular writers may make a stronger claim, that religion’s relationship to sexuality is basically antagonistic, and that Christian religions in particular are especially anti-sex (Hitchens, 2007; Shea, 1992). It is rarer to consider the positive aspects of religion and religiosity for sexual expression, and to ask whether religion and religiosity ever improve the quality of sexual life (McFarland, Uecker, & Regnerus, 2011).

We explore this topic using a nationally-representative sample of older adults (aged 57 and older). We focus on older adults for several reasons. First, while research on the role of religion in shaping adolescents’ sexual expression is well-studied (McCree, Wingwood, DiClemente, Davies, & Harrington, 2003; L. Miller & Gur, 2002; Thornton & Camburn, 1989; Woodroof, 1985), older adults are not often considered, potentially leading to a focus on risk-taking in the literature on religion and sexuality (Granger & Price, 2009; Gyimah et al., 2010; Haglund & Fehring, 2010; Simons et al., 2009). In addition, the relationship between religion and sexuality in longer-term relationships among older adults is not well-understood. In order to situate our inquiry in exiting scholarship we begin by reviewing literature on the impact of religiosity on sexual expression, with a focus on older couples and variation by gender.

Religion’s Normative Influence on Sexuality

We conceptualize ‘religious influence’ as configurations of behavior and attitudes that reflect the normative teachings of a religion. Note that being influenced by a religion does not require the individual to identify with that religion, or to be actively participating in that religion’s organizations. Individuals may have attitudes or practices that accord with the normative teachings of religion - for instance, encountered through his or her upbringing or contacts - without necessarily being religious themselves. Within sociology this kind of religious influence was first described by Max Weber, who identified the persistent influence of a Protestant ethic on the economy of an apparently secularizing Europe (Weber, 2002 [1905]: 121). This foundational perspective has been used in more modern studies, to document the impact of religious influence on morality (Joas, 2007), and delinquent behavior (Regnerus, 2003). Following this conceptualization, we now outline religious influence on sexuality, before discussing sexuality in older adulthood.

Religious norms generally channel sexual expression into monogamous sexual relationships, and researchers studying religion and quality of life have commonly described religiosity as reducing the frequency of extramarital sex (Drum, Shiovitz-Ezra, Gaumer, & Lindau, 2009; Koenig, George, Meador, Blazer, & Ford, 1994; Room, 1990). However, religious normative codes also may be pro-sex, but dedicated to organizing sexual expression in normatively-appropriate ways. Early sexual debut, for instance, may not be problematic when accompanied by marriage because it demonstrates that the individual has accepted certain moral guidelines and religiously-prescribed avenues of sexual expression (i.e., that sex should take place within a marriage relationship (Freitas, 2008) and is typified by love between the two partners (Laumann et al., 1994).

Qualitative research on religion and marital sex provides insight in how such social processes might unfold. Chrinstine J. Gardner, in a study of abstinence campaigns, shows how the rhetoric of religious leaders includes a promise that chastity will actually mean improved sexual satisfaction, as a divine reward for according with religious codes of conduct (Garnder, 2011). In another recent book, Sex in Crisis, Dagmar Herzog analyzes hundreds of Christian sex guides for long-term couples in order to describe a transformation in American religious discourses on sex, similar to what Gardner describes (2008). Herzog argues that highly-religious Americans are encouraged to organize their pleasure in religious ways without reducing their sexual quality of life (Herzog, 2008, Ch. 2). Thus, suffusing sexual activity with spiritual meaning may improve satisfaction, in the same manner as religiosity can provide sacred significance for worldly experiences in general (Underwood & Teresi, 2002).

While the media that Herzog and Gardner review are largely created by Protestants, other groups also imbue sexual activity with religious significance. For instance, one might expect that highly-religious Catholics would be more likely to be more sexually unsatisfied because Catholic dogma seemingly prohibits sex for reasons besides procreation. In an important work of Catholic apologetics, however, G.E.M. Anscombe argued that in fact, sex in marriage is not only permissible, but good so long as the desire for sex is not “in command” of the person’s morality or reason (Anscombe, 2008 [1972]: 189). And, Jennifer Hirsch, in an interview study of Mexican Catholics, found that many of her subjects understood sexual activity with their partners as commensurate with the Catholic principle that husbands and wives should be sexually available to one another (Hirsch, 2008).

Therefore, older adults may appropriate different elements of religious teachings, to use them in a way which does not necessarily reflect the expectations of religious leaders (Gardner, 2011). Additionally, religious influence may be more important for differences in behavior than religious affiliation in terms of the effect on sexual belief or practice (Regnerus, 2007). In short, there is ample reason to believe that older adults may appropriate religious norms in a manner that improves sexual expression. In the next section, we review research on sexual expression in older adulthood to examine how religious influence may be particularly consequential for this group.

Sexuality at Older Ages

Several previous studies have shown that sexual activity continues into older ages (Corona et al., 2010; Herbenick et al., 2010; Lindau et al., 2007; Palacios-Cena et al., 2012). Even in the presence of health problems, older adults may change their sexual behaviors to downplay intercourse in sexual expression so they can still engage in reciprocal and pleasurable activity (Corona et al., 2010; Waite, Das, & Laumann, 2008). Such activity at older ages tends to be in the context of long-term relationships (Laumann et al., 1994; Laumann & Michael, 2001; Mahay & Laumann, 2004), and so the challenges that older adults face to their quality of sexual life tend to emerge from pychosocial dynamics within the marital dyad.

For instance, research suggests that sexual ideation and desire seems to decline with age (J. D. DeLamater & Sill, 2005; Herbenick et al., 2010; E. O. Laumann, Glasser, Neves, & Moreira, 2009; Palacios-Cena et al., 2012). While both men and women experience such a decline on average, the rate over time may differ by gender with men typically experiencing higher sexual desire than women at older ages (Herbenick et al., 2010; Palacios-Cena et al., 2012). This may lead to asymmetries between men and women in terms of how satisfied they are with the frequency of sex in their lives. In a study using Finnish data, older men were significantly more likely to be satisfied with coital frequency compared to women (Kontula & Haavio-Mannila, 2009). In the U.S., low sexual desire is also much more common among women than men - 43% of women and 27% of men over the age of 57 report a lack of interest in sex (Laumann, Das, & Waite, 2009).

Older adulthood also creates new contexts for sexual satisfaction. Sexual satisfaction tends to be high in older adults’ romantic and sexual relationships, in part because the normative commitments of partners to one another encourage them to develop partner-specific skills for improving one another’s satisfaction (J. DeLamater, Hyde, & Fong, 2008; Laumann et al., 1994; Matthias, Lubben, Atchison, & Schweitzer, 1997). However, there is also considerable variability in satisfaction at older ages (J. DeLamater et al., 2008; Matthias et al., 1997). For instance, health problems may lower sexual desire (Palacios-Cena et al., 2012), leading to lower enjoyment of sexual activity (J. DeLamater et al., 2008).

A good-quality sex life at older ages will therefore often mean maintaining a level of coital frequency acceptable to two people in a long-term relationship, appropriate to their levels of sexual desire, where both partners feel that they are happy, physically and emotionally, with their sexual experiences. Religious norms may help to encourage sexual expression and improve the quality of older adults’ sexual lives, first by valuing the exclusive availability of sexual partners to each other, and by spiritualizing monogamous sexual expression. However, religious norms may prescribe different codes of conduct depending on gender, and men and women may not benefit equally from the influence of religious norms.

Gender, Religion and Sexual Expression

According to one body of literature, religious romantic and sexual partnerships are more likely to create an advantage for the man than the woman because traditional religious norms emphasize that women should submit to their husbands (Levitt & Ware, 2006). Based on this perspective, we would expect that men would benefit more than women because they are normatively permitted to set the frequency of sexual activity per their prerogative as head of household. Hirsch’s study also claims that women may feel pressured into sex in order to prevent their husbands from initiating extra-marital affairs (Hirsch, 2008), and, if so, women may experience less enjoyment from sex.

However, the competing hypothesis, that women would benefit more from religious norms, also is plausible. Other work has argued that religiosity and religious norms actually empower women in subtle ways (Bartkowski, 1997; Burke, 2012; Pevey, Williams, & Ellison, 1996). While highly-religious women may be instructed by church leaders to submit to their husbands, women may reinterpret these instructions in an empowering manner (Denton, 2004; Pevey et al., 1996). Furthermore, religious leaders sometimes encourage women to be more sexually expressive, as a way to prevent their husbands from being tempted to seek sexual satisfaction outside of the marriage (Bartkowski, 2001: 41). The spiritualization of the sexual relationship also may lead to greater satisfaction for women than men, as the effects of religiosity on behavior and attitudes are usually stronger for women (de Vaus & McAllister, 1987; Krause, Ellison, & Marcum, 2002; A. S. Miller & Hoffmann, 1995). Women across faiths - or even those who do not identify with a faith - may therefore maintain an active sexual relationship while seeing this sexual activity as spiritually meaningful (Bartkowski & Read, 2003).

In sum, previous research suggests two contradictory expectations about what we might find in our analyses of religion and its influence on sexual expression. This work will arbitrate between these perspectives with a focus on gendered associations between religious influence and normative orientations toward sexuality.

METHOD

Data and Respondents

The data come from the National Social Life, Health and Aging Project (NSHAP), a nationally-representative survey of older adults, comprising 1455 men and 1550 women over the age of 57, with data collected in 2005–20061. NSHAP’s large sample, targeted at older adults, makes it an ideal dataset for examining sex at older ages. It also asks numerous questions about sexual attitudes, religious attitudes and religious participation (McFarland et al., 2011). Ten percent of the sample is non-Hispanic black, and seven percent Hispanic. About a third of the sample is having sex once a week or more, and most respondents are satisfied with the amount of sex they are having (physically satisfied =70.6%; emotionally satisfied = 70.5%).

Analytic Procedure

We make use of Latent Class Analysis (LCA) to describe religious influence on sexual expression, following our conceptualization of religious influence as configurations of behavior and attitudes that reflect the normative teachings of a religion. LCA classifies cases into mutually-exclusive categories and facilitates descriptive and exploratory analysis by allowing us to compare classes on key variables (Nylund, Asparouhov, & Muthén, 2007). It also includes numerous measures of model fit for establishing the number of latent categories that best fit the data. We selected six variables for inclusion in the LCA, five dichotomous and one ordinal. These variables stem from the following questions: 1) “My religious beliefs have shaped and guided my sexual behavior” with four response options: strongly disagree, disagree, agree, strongly agree; 2) Whether the respondent has not had sex recently because “Your religious beliefs do not allow sex outside of marriage?;” 3) Whether the respondent answered ‘never’ to the question “On average, in the past 12 months how often did you masturbate?;” 5) Whether the respondent answered “always wrong” to the question “A married person having sexual relations with someone other than their marriage partner. Is this…?” and 6) Whether the respondent reports never having been divorced, if he or she has ever been married.2 In addition, these items were deliberately chosen to be a mix of attitudes and behaviors. While many religions also forbid the use of prostitutes, the LCA does not include this variable since the number of women who have ever paid for sex in the sample is very small compared to men (Male 25.2%, Female 0.3 %). We also do not include any variable on the use of prophylactics, since most of the respondents are in a long-term relationship (61.9%) and only two female respondents of the 1371 who answered the question reported that they are still menstruating (0.2%).

The LCA was fit in MPlus 6.1 statistical software using Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) in order to assuage problems with missing data (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2010).3 FIML accomplishes this by using all information which is available for every respondent without imputing values (Enders, 2001; Raykov, 2005). Unless a respondent is missing information on all six variables, the LCA will attempt to classify him or her using whatever information is available. In simulations FIML also has proven to be a more consistent estimator of model parameters than listwise deletion or pairwise deletion, recommending it for our use here (Enders, 2001).

After identifying the best-fitting LCA model, and assigning respondents to classes, we then proceed through two stages. First, we predict membership in the latent classes in order to examine whether religious factors predict membership in high-influence classes. We control for self-reported conservative political orientation, age, gender, race, education, and marital status, since these may confound the relationship between other religious factors and class membership. We also include a control for functional health since one of our variables, never masturbating, could also be the result of deficits in health. Our measure of functional health is a composite measure of difficulties with activities of daily living (Lawton & Brody, 1969). The variable is a count of the number of difficulties with any of the following: walking across a room; walking one block; dressing oneself; bathing; eating; getting in and out of bed; using the toilet; driving a car during daytime; driving a car at night.

Following this exercise, we use class membership to predict a number of outcomes related to sexual well-being. These outcomes include whether the respondent finds his or her current relationship physically pleasurable, and whether he or she finds the relationship emotionally satisfying. We also examine whether the respondent has sex with his or her partner at least once a week (coital frequency), whether the respondent is having sex as often as he or she would like, and if the respondent thinks about sex every day or more. Also, we predict the respondent’s agreement with the statement “I would not have sex with someone unless I was in love with them.” The logistic regression used in this analysis includes controls for gender, race, years of education, conservative political orientation, age, marital status, denomination, functional health status, attendance at services and intrinsic religiosity. We also include an influence-gender interaction term. Our key independent variable will be latent class membership. All analyses use NSHAP sampling weights. Because of the difficulties with interpreting a large number of outcomes at once, we will use the clarify software package for Stata (Tomz, Wittenberg, & King, 1999). As its name suggests, the clarify package is meant to render the effect sizes in models more intelligible, by turning odds ratios into changes in the predicted probability of some outcome.4

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for the variables used in this analysis. For the question of whether religion affects the respondent’s sexual behavior, we show the overall mean and standard deviation for the entire scale (ranging from 1 to 4 where 1 is ‘strongly disagree’), then the proportion of respondents who choose each option. We can see that responses are clustered near the high end of the scale. Most respondents either agree or strongly agree with the statement, and less than thirty percent disagree. This is consistent with other work (Smith, 2006). Of those who were asked whether they refused sex for religious reasons, only 11.8% said yes. The proportions for the other variables in the LCA are much higher, with ninety-six percent of the sample reporting never having a same sex partner. The number of people who never masturbate in the sample is also quite high - over sixty percent (47.9% of men and 75.6% percent of women say that they do not masturbate, results not shown). Prior research indicates that, in general, women do not masturbate as often as men at any age (Laumann et al., 1994), so these results are consistent with those findings.

Table One.

Descriptive Statistics (n=3005)

| Variable List | Range | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables in the Latent Class Analysis | |||

| Religion Affects Sexual Behavior | 1 to 4 | 3.004 | 0.970 |

| Strongly Disagree | (1) | 0.083 | – |

| Disagree | (2) | 0.217 | – |

| Agree | (3) | 0.314 | – |

| Strongly Agree | (4) | 0.387 | – |

| Refused Sex for Religious Reasons | 0 or 1 | 0.118 | 0.322 |

| Never Masturbates | 0 or 1 | 0.619 | 0.486 |

| Never had a Same-Sex Partner | 0 or 1 | 0.960 | 0.197 |

| Infidelity is Always Wrong | 0 or 1 | 0.812 | 0.391 |

| Never had a Divorce | 0 or 1 | 0.656 | 0.475 |

| Predictors and Controls | |||

| Female | 0 or 1 | 0.515 | 0.500 |

| Race/Ethnicity | 1 to 3 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | (1) | 0.806 | 0.395 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | (2) | 0.099 | 0.299 |

| Hispanic | (3) | 0.069 | 0.254 |

| Politically Conservative | 0 or 1 | 0.304 | 0.460 |

| Years of Education | 0 to 32 | 13.039 | 3.662 |

| Age | 57 to 85 | 68.022 | 7.690 |

| Married | 0 or 1 | 0.664 | 0.473 |

| Functional Health Problems | 0 to 9 | 0.836 | 1.570 |

| Religion | |||

| Services at Least Once a Week | 0 or 1 | 0.444 | 0.497 |

| Carries Rel. Beliefs into Other Areas of Life | 0 or 1 | 0.798 | 0.402 |

| Catholic | 0 or 1 | 0.276 | 0.447 |

| Baptist | 0 or 1 | 0.193 | 0.394 |

| Lutheran | 0 or 1 | 0.078 | 0.269 |

| Outcomes | |||

| Finds Current Relat. Physically Pleasurable | 0 or 1 | 0.706 | 0.456 |

| Finds Current Relat. Emotionally Satisfying | 0 or 1 | 0.705 | 0.456 |

| Has Sex With Partner At Least Once a Week | 0 or 1 | 0.338 | 0.473 |

| Sex Not as Often As Preferred | 0 or 1 | 0.353 | 0.478 |

| Sex is More Often than Preferred | 0 or 1 | 0.074 | 0.262 |

| Thinks about Sex Every Day or More | 0 or 1 | 0.164 | 0.371 |

| Would not Have Sex Unless in Love | 0 or 1 | 0.757 | 0.429 |

Turning to predictors and controls, we see that the proportions are what we might expect for this age range. The mean age is 68, and about one third of the sample is politically conservative. The religiosity variables provide some insight into the religious lives of adults at older ages. A little less than half of these adults attend church at least once a week. Almost eighty percent of the respondents agree with the statement that they carry their religious beliefs into other areas of their lives. Furthermore, regarding denomination, the modal denomination is Catholic (85.16% of the sample was Christian - 51 respondents, or 1.7%, were Jewish). Regarding the outcomes of interest in this analysis, we see that, like other age groups in the United States, the sample appears to be happy with their relationships (Laumann et al., 1994). About seventy percent each say that their current relationship is very or extremely physically pleasurable, and almost exactly the same number say that they find their relationships emotionally satisfying (the correlation between these two variables is 0.58). Finally, note that about three-quarters of these respondents say they would not have sex unless they were in love.

Latent Class Analysis

In selecting the correct number of latent classes we relied on the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), which is considered the most reliable test of model fit (Nylund et al., 2007). We settled on two classes, which we present in Table Two. Note that the significance stars associated with the odds ratios in this table were determined by t-test for the dichotomous items, but a chi-squared test for the ordinal item.

Table Two.

Religious Influence on Normative Orientation Toward Sex, Expressed as Proportions within Latent Classes

| Count/ (Percent of Sample) |

High Influence | Low Influence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1903 (63.3%) |

1102 (36.7%) |

||

|

| |||

| Proportion w/in Class |

Proportion w/in Class |

Odds Ratio High to Low |

|

| Religion Affects Sexual Behavior | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 0.001 | 0.208 |

*** ***

|

| Disagree | 0.032 | 0.503 | |

| Agree | 0.331 | 0.288 | |

| Strongly Agree | 0.636 | 0.001 | |

| Refused Sex for Religious Reasons | 0.189 | 0.003 | 77.449 *** |

| Never Masturbates | 0.813 | 0.319 | 9.281 *** |

| Never Had a Same-Sex Partner | 0.977 | 0.932 | 3.100 *** |

| Infidelity is Always Wrong | 0.971 | 0.561 | 26.201 *** |

| Never Had a Divorce | 0.742 | 0.515 | 2.708 *** |

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

The most striking finding in this component of the analysis is that the attitudinal and behavioral variables move together, and that there is no class which is typified by religious attitudes without religious behavior. Almost two-thirds of the first class strongly agrees with the statement that his or her religion affects sexual behavior, and all of the other variables in the LCA suggest that this influence of religion on sexual expression extends to both attitudes and behavior. The odds of refusing sex for religious reasons are 77 times greater in the first class compared to the second. The odds of never masturbating are ten times greater, and twenty-six times greater for saying that infidelity is always wrong. Three quarters of the first class have never been divorced (note that individuals who were never married would have had their values set to missing, and so were excluded from the risk pool). Overall it appears that the U.S. population of older adults can be bifurcated into two classes: one for whom religion seems to play a large role in influencing their normative orientation towards sexual expression, and another for whom the influence is much reduced. Accordingly we label the first class as the ‘high influence’ class and the second ‘low influence.’ Note as well that there are almost twice as many people in the high influence class, further solidifying our impression of this age group as highly religious in their sexual expression.5

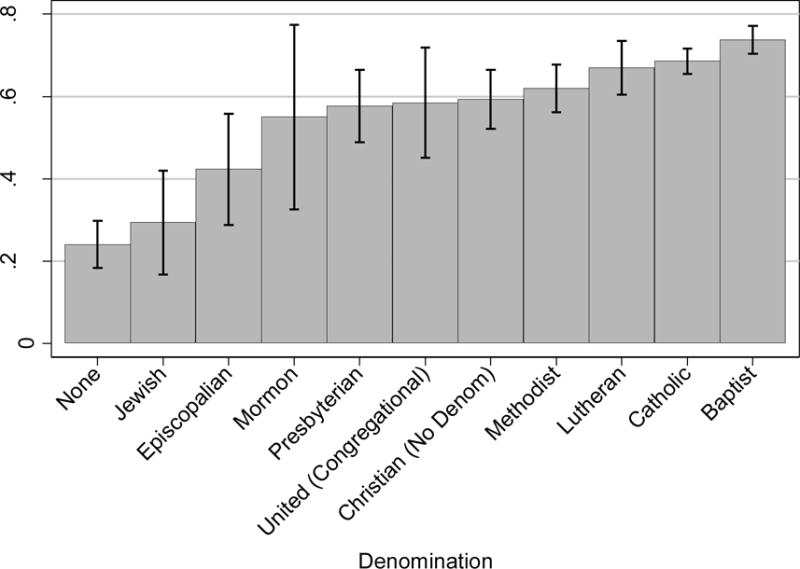

We can break down membership in the high influence class according to denomination in order to see whether any denomination has an exclusive or overwhelming claim on class membership. In Figure 1 denominations are arrayed from left to right in terms of the proportion within each denomination that was placed in the high influence class. While there is a clear difference between the very lowest and the very highest bars, many of the intermediate denominations have confidence interval bars which overlap, indicating that we cannot easily distinguish between them in terms of how strongly their members’ religions influence their sexual expression. Some of this is a matter of small sample size - there are only fifty Mormons in the sample. However for others with larger proportions of the sample, such as Lutherans, there is some reason to suspect that they really are no different from Methodists, Catholics, Congregationalists or Presbyterians. Given that most of the bars’ confidence intervals intersect the gridlines at 0.60, it appears rare that more than sixty percent of any denomination in the United States, within this age range, is highly-influenced by religion in their sexual expression.6

Figure One.

Proportion in High Influence Class by Denomination, with 95% Confidence Interval Bands

In Table 3 we predict membership in the high influence class in three models. The first model includes demographic variables, political identification, and functional health problems. The second model includes religious variables, and the third introduces both sets of variables into the same model. We approach modeling in this manner to see whether the religious variables reduce the demographic variables to insignificance. Note that all coefficients are in odds ratio format.

Table Three.

Predicting Membership in High Influence Class (Logit Link; Odds Ratios)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 2.614 | *** | 2.025 | *** | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.946 | *** | 1.151 | |||

| Hispanic | 1.012 | 0.851 | ||||

| Politically Conservative | 2.334 | *** | 1.751 | ** | ||

| Years of Education | 0.938 | *** | 0.930 | *** | ||

| Age (Five Year Intervals) | 1.218 | *** | 1.177 | *** | ||

| Currently Married | 1.961 | *** | 1.710 | *** | ||

| Functional Health Problems | 0.967 | 0.973 | ||||

| Religion | ||||||

| Religious Participation | 3.927 | *** | 3.627 | *** | ||

| Intrinsic Religiosity | 4.173 | *** | 3.630 | *** | ||

| Catholic | 1.706 | *** | 1.805 | ** | ||

| Baptist | 2.279 | *** | 2.191 | *** | ||

| Lutheran | 1.365 | 1.529 | ||||

| Constant | 0.609 | 0.218 | *** | 0.167 | *** | |

|

| ||||||

| N | 2246 | 2310 | 2198 | |||

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

In Model 1, the largest odds ratio predicting membership in the high influence class is being female. Functional health problems are not significant, and neither is Hispanic ethnicity. Note that not all of these variables are on the same scale; while the odds ratio for years of education seems small, it will quickly compound with each year of education to produce large differences. Most of the coefficients are highly significant as well, including a report that one is politically conservative.

In Model 2, attending services at least once a week and agreeing that one carries one’s religious beliefs into other areas of one’s life are also very strong predictors of membership in the high influence class. Being a Lutheran is not significantly associated with membership in the high influence class, but being Catholic and Baptist, in particular, is, net of religious participation and intrinsic religiosity. Denominations therefore predict membership in the high influence class, but the effects are still notably smaller than participation and intrinsic religiosity.

Adding the two sets of variables together reduces race to insignificance, and lessens the effect of political conservatism. The religious variables all remain large and highly significant, as does gender. We tested whether or not the religious variables’ coefficients were significantly different from all the other variables in the model using adjusted Wald tests. We found that the coefficient for frequently attending services was significantly different from every other coefficient at p<0.05, except intrinsic religiosity. Intrinsic religiosity also was significantly different from every other coefficient, except attendance. These findings suggest that membership in the LCA is a matter of religious influence, and that this influence is not confined to any particular denomination.

Analysis of Outcomes

Table Four is divided into two panels. Panel A shows first differences between those in the low and the high influence classes for men. Panel B shows the same for women. Both panels were generated using the same model, which included an interaction term between high influence class membership and gender (female). We also explored whether there were any interactions by age, and did not find any for these outcomes. Additionally, we re-ran these analyses only for respondents who reported a romantic/sexual partner and also found very similar results.

Table Four.

| Panel A: Difference between men in the low influence class (INF=0) and men in the high influence class (INF=1) on key outcomes. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Outcome | Pr(Y=1|INF=0) | Pr(Y=1|INF=1) | ΔPr(Y=1) |

| Current Relat. Physically Pleasurable | 0.779 | 0.843 | +0.064* |

| Current Relat. Emotionally Satisfying | 0.790 | 0.901 | +0.111** |

| Has Sex with Partner At Least Once a Week | 0.349 | 0.359 | +0.010 |

| Sex is Not as Often As Preferred | 0.479 | 0.335 | −0.144** |

| Sex is More Often than Preferred | 0.017 | 0.024 | +0.007 |

| Thinks About Sex Every Day | 0.292 | 0.214 | −0.078** |

| Would not Have Sex Unless in Love | 0.656 | 0.904 | +0.248** |

| Panel B: Difference between women in the low influence class (INF=0) and women in the high influence class (INF=1) on key outcomes. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Outcome | Pr(Y=1|INF=0) | Pr(Y=1|INF=1) | ΔPr(Y=1) |

| Current Relat. Physically Pleasurable | 0.724 | 0.674 | −0.050 |

| Current Relat. Emotionally Satisfying | 0.710 | 0.743 | +0.033 |

| Has Sex with Partner At Least Once a Week | 0.397 | 0.319 | −0.078 |

| Sex is Not as Often As Preferred | 0.298 | 0.211 | −0.087* |

| Sex is More Often than Preferred | 0.034 | 0.072 | +0.038* |

| Thinks About Sex Every Day | 0.051 | 0.053 | +0.002 |

| Would not Have Sex Unless in Love | 0.852 | 0.963 | +0.111** |

Probabilities computed for white, Protestant, politically moderate, married persons between 61–65 years old, with 12 years of education, no functional health problems who are intrinsically religious and attend church once a week.

Note:

p<.05

p<.01

Probabilities computed for white, Protestant, politically moderate, married persons between 61–65 years old, with 12 years of education, no functional health problems who are intrinsically religious and attend church once a week.

Note:

p<.05

p<.01

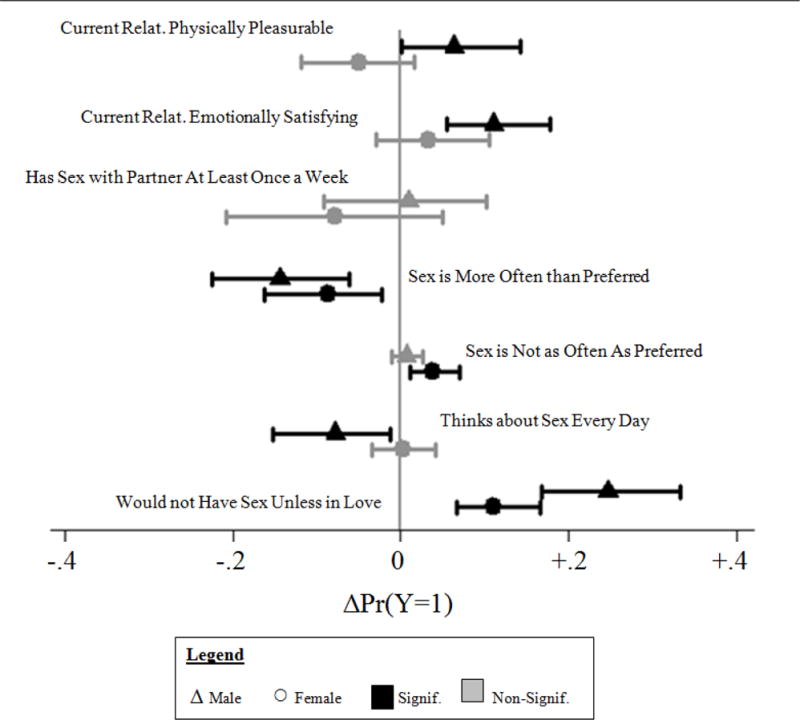

Some of the gender differences between the two panels are quite striking. Perhaps most interesting, men in the high influence class are more likely to say that they find their current relationship to be physically pleasurable and emotionally satisfying compared to men in the low influence class. This is not true for women, and class membership does not significantly distinguish between women in terms of these outcomes. While the gains for men on physical pleasure are modest, gains on emotional satisfaction are almost twice as large, starting from approximately the same baseline probability of agreement. High influence class membership therefore seems to be more beneficial for men than women. Men also are less likely to say that they think about sex every day if they are members of the high influence class. Finally, note the enormous effect of class membership on whether men agree with the statement that they would only have sex if they were in love with their partners—an increase of twenty-five percent. There is a similar increase for women, but it is less than half the size. Other effect sizes are modestly large in comparison.

Both men and women in the high influence class are less likely to say that they are not having sex as often as they would like, compared to the low influence class. While this could suggest that both men and women are benefiting, women in the high influence class are also more likely to say that they are having sex more often than they would like. In other words, women are probably less likely to say that they are not having enough sex because they are having too much, and possibly not the right amount. While the change in the probability of agreement with this statement is small (0.038), the difference is significant, and because the probability of agreement is itself small for the low influence class (0.034), this means that women in the high-influence class are actually about twice as likely to agree with the statement as women in the low-influence class. However, it should be noted that this is a small effect size, especially when compared to results for whether respondents agree with the statement that they would only have sex if they were in love with their partners.

We can describe the gender differences even more clearly in Figure 2, which plots the effect sizes from Table 4. Around each effect size, we have placed 95% confidence interval bands. The point estimates of the effect are marked with triangles for men and circles for women. When the confidence interval bands cross the central vertical axis, zero, we shade the bands with gray in order to indicate that we cannot distinguish this effect from zero at that confidence level. When the confidence interval band for one gender crosses the line at zero, and another does not, we will consider this to be a significant gender difference between men and women. This figure demonstrates that some of the apparent gender differences described above are not so easily distinguishable from one another. There appears to be no difference between men and women in agreeing that they are not having sex as often as they would like. However, as we observed, this response may mean something different for men and women. Finally, note the differences between men and women in terms of their probability of saying that they would not have sex with anyone they were not in love with—the confidence interval bands for the effect on women and the effect on men do not overlap, although they are very close.

Figure Two.

Changes in Outcomes, with 95% confidence interval bands for men and women

DISCUSSION

We initially hypothesized that there would be some intermediary class that would indicate the influence of religion, but only on beliefs and not practices. No such class emerged, and it seems that never having a same-sex partner, condemning infidelity, never divorcing, refusing sex for religious reasons, never masturbating, and agreeing with the statement that religion affects one’s sexual behavior all track together. Moreover, no completely ‘secular’ class emerged from the analysis. One-third of the respondents in the low influence class still agreed with the statement that their religion affected their sexual behavior, and few completely disagreed. The very lower proportion of respondents who refused sex for religious reasons in the low influence class suggests that older adults are not divided between ‘religious’ and ‘non-religious,’ in terms of the impact of religion on their sexual expression. Rather, the two most salient categories are strong and weak influence.

Figure 1 indicates that while it is rare to find people without a religious affiliation in the high influence class, it is by no means impossible. Nearly twenty percent of people who answered ‘none’ when asked their religious affiliation were also classified as being highly influenced by religion. We should therefore avoid interpreting ‘none’ as ‘atheist’ or ‘agnostic.’ Furthermore, large percentages of people who affiliated themselves with a specific religious tradition were not in the high influence class, and subsequent analyses revealed that there is much more variability within denominations than between. Also, our regression analyses showed that denomination mattered less than religious participation or intrinsic religiosity.

We also found that class membership mattered more for men than for women in terms of improving satisfaction, in spite of the fact that more women were in the high-influence class compared to men. While we do not make a causal argument in this paper, as a purely descriptive exercise our findings suggest that women are more likely to be heavily-influenced by religion in their sexual lives, but men are more likely to reap the benefits of that influence. Part of this may be that men are more likely to be risk-takers, and thus step outside the bounds of accepted sexual practice (A. S. Miller & Hoffmann, 1995). Religion could provide a counterbalance to antisocial or reckless sexual expression, bringing men and women closer together in terms of their sexual profiles. We consider this to be the key finding of the paper, and a contribution to our understanding of religion and sexual life in older adulthood, as well as religion and sexual life more broadly. Specifically, our literature review suggested two contradictory expectations about the extent to which the relationship between religious influence and sexual expression would differ by gender, one which emphasized greater benefits for men, and another that emphasized greater benefits for women. Our results indicate that the benefits of long-term relationships may be greater for men.

Important for this finding, neither men nor women in the high influence class seem to be having more sex than men and women in the low influence class, but men are more likely to be happy with the amount of sex they are having, while women are more likely to feel as if it is too much. It could be the case that women in the high influence class would prefer to be having less sex than women in the low influence class, but are less able to avoid or refuse sex because religious norms typically dictate that women should be compliant with their husbands (Levitt & Ware, 2006). However we have no information on whether highly-influenced women are partners with highly-influenced men. We cannot ascertain which account is correct, but our data indicate that women in the high-influence class think about sex as often as women in the low-influence class (so women in the high-influence class do not have more subdued sex drives).

Why men in the high influence class would be more satisfied with the same amount of sex as men in the low influence class requires further explication. We see that men in the high influence class are less likely to say that they think about sex every day or more. While this could be social desirability bias, if we take them at their word then it could be that individuals who are highly influenced by religion in their sexual expression are also influenced by it in terms of sexual ideation. Individuals with high religiosity may think differently about the world, and come to see it suffused with spiritual meaning (Underwood & Teresi, 2002). If so, sex may not be on the male respondents’ minds as much, and the desire for sex felt less strongly than less-religious men. Men in the high influence class also may feel that there is a proper place for sex, namely when it is motivated by genuine love for their partners. Note that we saw a very large effect of high-influence class membership on whether men would only have sex with those they love. This corresponds with the mechanism laid out in our literature review, that religious influence focuses sexual affection on the marital dyad.

Conclusions

This paper was concerned with the role of religious influence on quality of sexual life. Our major finding was that this influence, where it exists, varies by gender. The gender differences not only conform with previous findings, but also suggest a broader influence of religion on sexuality, compared to previous, risk-focused studies. We concentrated on aspects of religion which provide particular, doctrine-bound guidelines for conduct. Other studies interested in examining religious social processes may benefit from attention to these guidelines and the extent to which they shape social choices and social interaction.

Footnotes

NSHAP’s sampling frame involved probability proportionate to size selection of US Metropolitan Statistical Areas, random sampling of area segments within primary units, and a complete listing and screening of all housing units within the area segment. This approach included an oversampling of African-American and Hispanic respondents, as well as the oldest old (85 and up). All results are weighted according to the probability weights derived from this sampling frame.

We selected these questions based on whether religions and religious denominations in the United States often provide normative injunctions which regulate these activities or attitudes, in part because they depart from treating sex as a procreational rather than recreational activity (Laumann et al., 1994).

Only 1440 respondents answered whether they refused sex for the sake of their religious beliefs because only respondents who had not had sex in the past three months were asked this question. We would not want to limit our analysis only to those respondents who have not had sex in the past three months; FIML allows us to include all respondents in our LCA, regardless of whether they were asked this question.

The package does this by drawing simulations of the model parameters from their asymptotic sampling distribution. When the regression has a logit link function, the distribution is a multivariate normal with a mean equal to the parameter estimates and a variance equal to the variance-covariance matrix of the parameter estimates. It then creates multiple simulations in order to produce distributions for these parameter estimates, and thus confidence intervals. Then the program converts the simulated parameters into predicted probabilities and first differences in order to simplify the interpretation of the model. The only restriction is that all variables in the model must be set to specific values. Because predicted probabilities have to be computed after setting the controls to some value, these probabilities refer only to a certain portion of the population. These are the modal values for each of the variables. Years of education was set to 12 because this is the median value for this variable.

Because we wanted to ensure that we were measuring religious influence, we also re-estimated the LCA excluding masturbation and divorce. This LCA also produced two classes of high and low religious influence, and 97.3% of cases that were classified as ‘high influence’ in the above LCA were classified as ‘high influence’ in the second LCA. Furthermore, we re-ran all analyses in this paper using results from the second LCA, and the results were very similar.

In fact, we find that if the overall proportion of the sample in the high influence class is 0.633, the standard deviation of this proportion is 0.482, decomposable into a between-denomination standard deviation of 0.188, and a within-denomination standard deviation of 0.463. These data suggest a great deal of within-denomination variability.

Contributor Information

James Iveniuk, Department of Sociology, University of Chicago, Chicago, USA, Toronto, Canada.

Colm O’Muircheartaigh, Harris School of Public Policy, University of Chicago, Chicago, USA Kathleen A. Cagney, Department of Sociology, University of Chicago, Chicago, USA.

References

- Anscombe GEM. Contraception and chastity. In: Geach M, Gormally L, editors. Faith in a Hard Ground: Essays on Religion, Philosophy and Ethics by GEM Anscombe. Exeter, UK: Imprint Academic; 2008 [1972]. pp. 170–191. [Google Scholar]

- Bartkowski JP. Debating patriarchy: Discursive disputes over spousal authority among evangelical family commentators. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1997;36:393–410. [Google Scholar]

- Bartkowski JP. Remaking the Godly Marriage: Gender Negotiation in Evangelical Families. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bartkowski JP, Read JnG. Veiled submission: Gender, power, and identity among evangelical and Muslim women in the United States. Qualitative Sociology. 2003;26:71–92. [Google Scholar]

- Burke KC. Women’s agency in gender-traditional religions: A review of four approaches. Sociology Compass. 2012;6:122–133. [Google Scholar]

- Corona G, Lee DM, Forti G, O’Connor DB, Maggi M, O’Neill TW, et al. Age-related changes in general and sexual health in middle-aged and older men: results from the European Male Ageing Study (EMAS) The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2010;7:1362–1380. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vaus D, McAllister I. Gender differences in religion: A test of the structural location theory. American Sociological Review. 1987;52:472–481. [Google Scholar]

- DeLamater J, Hyde JS, Fong MC. Sexual satisfaction in the seventh decade of life. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 2008;34:439–454. doi: 10.1080/00926230802156251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLamater JD. The social control of human sexuality. In: McKinney K, Sprecher S, editors. Human Sexuality: The Societal and Interpersonal Context. Westport, CT: Ablex Publishing; 1989. pp. 30–62. [Google Scholar]

- DeLamater JD, Sill M. Sexual desire in later life. Journal of Sex Research. 2005;42:138–149. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton ML. Gender and marital decision making: Negotiating religious ideology and practice. Social Forces. 2004;82:1151–1180. [Google Scholar]

- Drum ML, Shiovitz-Ezra S, Gaumer E, Lindau ST. Assessment of smoking behaviors and alcohol use in the National Social Life, Health and Aging Project. Journals of Gerontology - Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2009;64B:S119–S130. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbn017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. A primer on Maximum Likelihood algorithms available for use with missing data. Structural Equation Modeling. 2001;8 [Google Scholar]

- Freitas D. Sex and the Soul: Juggling Sexuality, Spirituality, Romance and Religion on America’s College Campuses. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner CJ. Making Chastity Sexy: The Rhetoric of Evangelical Abstinence Campaigns. Los Angeles: University of California Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Garnder CJ. Making Chastity Sexy: The Rhetoric of Evangelical Abstinence Campaigns. Los Angeles: University of California Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Granger MD, Price GN. Does religion constrain the risky sex behavior associated with HIV/AIDS? Applied Economics. 2009;41:791–802. [Google Scholar]

- Gyimah SO, Tenkorang EY, Takyi BK, Adjei J, Fosu G. Religion, HIV/AIDS and sexual risk taking among men in Ghana. Journal of Biosocial Sciences. 2010;42:531–547. doi: 10.1017/S0021932010000027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haglund KA, Fehring RJ. The association of religiosity, sexual education and parental factors with risky sexual behaviors among adolescents and young adults. Journal of Religion and Health. 2010;49:460–472. doi: 10.1007/s10943-009-9267-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbenick D, Reece M, Schick V, Sanders SA, Dodge B, Fortenberry JD. Sexual behaviors, relationships, and perceived health status among adult women in the United States: results from a national probability sample. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2010;7(Suppl 5):277–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog D. Sex in Crisis: The New Sexual Revolution and the Future of American Politics. Philadelphia, PA: Basic Books; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch JS. Catholics using contraceptives: Religion, family planning, and interpretive agency in rural Mexico. Studies in Family Planning. 2008;39:93–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitchens C. God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything. New York, NY: Random House; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Joas H. Braucht der Mensch Religion? Über Erfahrungen der Selbsttranszendenz. Freiburg: Herder Verlag; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, George LK, Meador KG, Blazer DG, Ford SM. Religious practices and alcoholism in a Southern adult population. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1994;45:225–231. doi: 10.1176/ps.45.3.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontula O, Haavio-Mannila E. The impact of aging on human sexual activity and sexual desire. Journal of Sex Research. 2009;46:46–56. doi: 10.1080/00224490802624414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Ellison C, Marcum J. The effects of church-based emotional support on health: Do they vary by gender? Sociology of Religion. 2002;63:21–47. [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Das A, Waite LJ. Sexual dysfunction among older adults: Prevalence and risk factors from a nationally-representative U.S. probability sample of men and women 57–85. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2009;5:2300–2311. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00974.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Gagnon JH, Michael RT, Michaels S. The Social Organization of Sexuality: Sexual Practices in the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Glasser DB, Neves RC, Moreira ED., Jr A population-based survey of sexual activity, sexual problems and associated help-seeking behavior patterns in mature adults in the United States of America. International Journal of Impotence Research. 2009;21:171–178. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2009.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Michael RT. Introduction: Setting the scene. In: Laumann EO, Michael RT, editors. Sex, Love and Health in America: Private Choices and Public Policies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2001. pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt HM, Ware K. Anything with two heads is a monster:’ religious leaders’ perspectives on marital equality and domestic violence. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:1169–1190. doi: 10.1177/1077801206293546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O’Muircheartaigh CA, Waite LJ. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357:762–774. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahay J, Laumann EO. Meeting and mating over the life course. In: Laumann EO, Ellingson S, Mahay J, Paik A, Youm Y, editors. The Sexual Organization of the City. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Matthias RE, Lubben JE, Atchison KA, Schweitzer SO. Sexual activity and satisfaction among very old adults: results from a community-dwelling Medicare population survey. The Gerontologist. 1997;37:6–14. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCree DH, Wingwood GM, DiClemente R, Davies S, Harrington KF. Religiosity and risky behavior in African-American adolescent females. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33:2–8. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00460-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland MJ, Uecker JE, Regnerus MD. The role of religion in shaping sexual frequency and satisfaction: Evidence from married and unmarried older adults. Journal of Sex Research. 2011;48:297–308. doi: 10.1080/00224491003739993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AS, Hoffmann JP. Risk and religion: An explanation of gender differences in religiosity. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1995;34:63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Miller L, Gur M. Religiousness and sexual responsibility in adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31:401–406. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Fifth. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO. Deciding on the number of classes in Latent Class Analysis and Growth Mixture Modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling. 2007;14:535–569. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios-Cena D, Carrasco-Garrido P, Hernandez-Barrera V, Alonso-Blanco C, Jimenez-Garcia R, Fernandez-de-las-Penas C. Sexual behaviors among older adults in Spain: results from a population-based national sexual health survey. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2012;9:121–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pevey C, Williams CL, Ellison CG. Male god imagery and female submission: Lessons from a southern baptist ladies’ bible class. Qualitative Sociology. 1996;19:173–193. [Google Scholar]

- Raykov T. Analysis of longitudinal studies with missing data using covariance structure modeling with full-information maximum likelihood. Structural Equation Modeling. 2005;12:493–505. [Google Scholar]

- Regnerus MD. Linked lives, faith, and behavior: Intergenerational religious influence on adolescent delinquency. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2003;42:189–203. [Google Scholar]

- Regnerus MD. Forbidden Fruit: Sex and Religion in the Lives of American Teenagers. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Room R. Measuring alcohol consumption in the United States: methods and rationales. In: Kozlowski LT, Annis HM, Cappell HD, Glaser FB, Goodstadt MS, Isreael Y, Kalant H, Sellers EM, Vingilis ER, editors. Research Advances in Alcohol and Drug Problems. Vol. 10. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1990. pp. 39–80. [Google Scholar]

- Shea JD. Religion and sexual adjustment. In: Schumaker JF, editor. Religion and Mental Health. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1992. pp. 70–86. [Google Scholar]

- Simons LG, Burt CH, Peterson FR. The effect of religion on risky sexual behavior among college students. Deviant Behavior. 2009;30:467–485. [Google Scholar]

- Smith TW. The National Spiritual Transformation Study. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2006;45:283–296. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton A, Camburn D. Religious participation and adolescent sexual behavior and attitudes. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1989;51:641–653. [Google Scholar]

- Tomz M, Wittenberg J, King G. Clarify: Software for interpreting and presenting statistical results. 1999 Retrieved March 14, 2012, from http://gking.harvard.edu/stats.shtm.

- Underwood LG, Teresi JA. The daily spiritual experiences scale: development, theoretical description, reliability, exporatory factor analysis and preliminary construct validity using health-related data. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2002;24:22–33. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite LJ, Das A, Laumann EO. Sexual activity in later life. In: Carr D, editor. Encyclopedia of the Life Course and Human Development. Woodbridge, CT: Macmillan; 2008. Reference USA. [Google Scholar]

- Weber M. The Protestant Ethic and the “spirit” of Capitalism. In: Baehr P, Wells G, editors. The Protestant Ethic and the “Spirit” of Capitalism and Other Writings. New York, NY: Penguin; 2002 [1905]. pp. 1–203. [Google Scholar]

- Woodroof JT. Premarital sexual behavior and religious adolescents. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1985;24:343–366. [Google Scholar]