Abstract

Mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to normal aging and a wide spectrum of age-related diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease. It is important to maintain a healthy mitochondrial population which is tightly regulated by proteolysis and mitophagy. Mitophagy is a specialized form of autophagy that regulates the turnover of damaged and dysfunctional mitochondria, organelles that function in producing energy for the cell in the form of ATP and regulating energy homeostasis. Mechanistic studies on mitophagy across species highlight a sophisticated and integrated cellular network that regulates the degradation of mitochondria. Strategies directed at maintaining a healthy mitophagy level in aged individuals might have beneficial effects. In this review, we provide an updated mechanistic overview of mitophagy pathways and discuss the role of reduced mitophagy in neurodegeneration. We also highlight potential translational applications of mitophagy-inducing compounds, such as NAD+ and urolithins.

1. Introduction

Aging is associated with a loss of physiological integrity, including an imbalance in proteostasis and an increase in mitochondrial dysfunction, which can be caused by compromised autophagy and its subtype mitochondrial autophagy, termed mitophagy. Autophagy is the process by which cellular components are degraded and recycled within the cell. Autophagy can refer to the nonspecific, cell-wide degradation of organelles or misfolded proteins in nutrient-starved conditions, as well as the removal of specific damaged or superfluous organelles. Aging and age-related pathologies are associated with reductions in autophagy [1], and emerging evidence suggests that the upregulation of autophagy may delay the onset and ameliorate the symptoms of age-related phenotypes [2]. A reduction in autophagy leads to neurodegeneration in mice [3–5] and is thought to contribute to several neurodegenerative diseases in humans [6]. Mitophagy is a specialized form of autophagy that regulates the turnover of mitochondria. Mitochondria, classically referred to as the “powerhouse” of the cell, produce cellular energy in the form of ATP. However, a large body of work has established additional and synergistic roles of the mitochondria in the regulation of cellular homeostasis [7]. Mitochondrial dysfunction is considered a hallmark of aging [8], and is implicated in apoptosis, senescence, genome instability, inflammation, and metabolic disorders [7, 9]. The term “mitophagy” was first coined by Dr. Lemasters in 2005 [10]. Since then, mitophagy has been linked to various diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders [11] such as Parkinson’s [12], Huntington’s [13], and Alzheimer’s [14], as well as normal physiological aging [15]. In this review, we summarize recent findings linking mitophagy to aging and neurodegeneration. We discuss connections between mitochondrial turnover and genomic stability, explore therapeutic interventions targeting mitophagy pathways, and highlight emerging avenues of research in the field.

2. Overview of mitophagy pathways

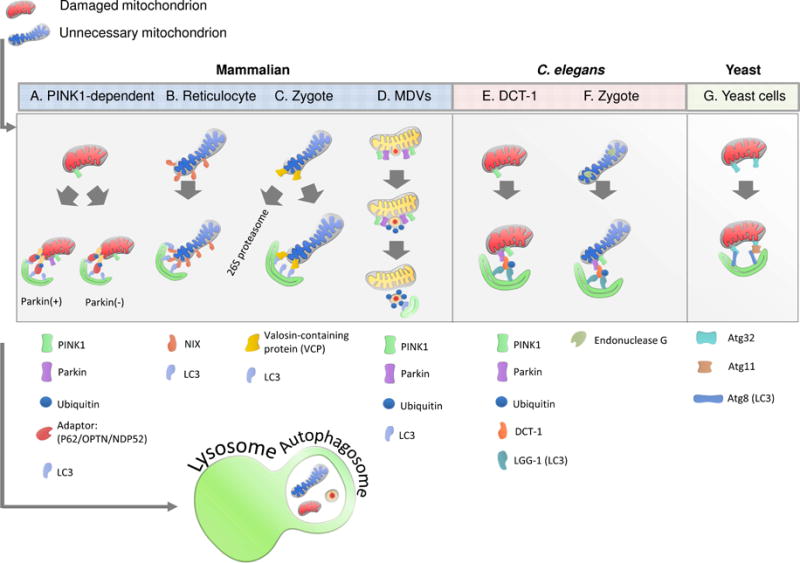

Accumulating evidence demonstrates that mitophagy functions throughout life, in fertilization and development, maintaining health throughout life, and preventing age-related disease. Molecular mechanisms of mitophagy have been intensively investigated in multiple species (Figure 1). Mitophagy can either specifically eliminate damaged mitochondria or clear all mitochondria during specialized developmental stages (fertilization and blood cell maturation) or starvation (phosphoinositide 3-kinase/PI3K-dependent). Here we summarize current knowledge of different mitophagy pathways in mammalian cells, C. elegans, and yeast.

Figure 1. Overview of Mitophagy Pathways.

A. PINK1/Parkin-mediated pathway. PINK1 is stabilized on the outer mitochondrial membrane of damaged mitochondria where it phosphorylates ubiquitin, leading to the activation of parkin. Parkin polyubiquitinates mitochondrial proteins, leading to the association with autophagy receptors and the formation of the autophagosome. The autophagosome then fuses with the lysosome, leading to degradation. Alternatively, PINK1 can recruit autophagy receptors directly in a parkin-independent manner, leading to low levels of mitophagy.

B. Reticulocyte mitophagy. Upon maturation signal, NIX localizes to the outer mitochondrial membrane of reticulocyte mitochondria. NIX binds to LC3, leading to the formation of the autophagosome.

C. Mammalian sperm mitophagy. Ubiquitinated paternal sperm associates with VCP. VCP facilitates the presentation of ubiquitinated (Ub) sperm mitochondrial proteins to the 26S proteasome, leading to degradation. Synchronously, SQSTM1 binds to other ubiquitinated mitochondrial proteins leading to sequestration within an autophagosome.

D. Mitochondria-derived vesicles. Unfolded oxidized proteins lead to aggregation. Cardiolipin is locally oxidized to phosphatidic acid, leading to membrane curvature. PINK1 is localized to the outer mitochondrial membrane where it recruits parkin. The vesicle is formed and the cargo is transported to the lysosome for degradation.

E. C. elegans somatic tissue. PINK1 is stabilized on the OMM of damaged/superfluous mitochondria, leading to the recruitment of parkin. Parkin ubiquitinates DCT-1 (homolog of NIX/BNIP3L), which associates with LGG-1 (homolog of LC3), leading to the formation of the autophagosome.

F. C. elegans sperm. Loss of membrane integrity triggers the release of endonuclease G from inner mitochondrial membrane space to the mitochondrial matrix, where it degrades mtDNA.

G. Yeast. Association of OMM protein Atg32 to isolation membrane-bound Atg8 directly or through its interaction with Atg11 recruits targeted mitochondria to the autophagosome.

2.1 Mitophagy in mammals

Under nutrient-rich conditions, damaged and superfluous mitochondria are selectively degraded to maintain mitochondrial homeostasis. One of the most studied pathways in clearing damaged mitochondria in mammalian cells is the PINK1/Parkin pathway (recently reviewed by [16, 17]) (Fig. 1A). PINK1-Parkin-dependent mitophagy is initiated when a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential caused by mitochondrial damage leads to the stabilization of the ubiquitin kinase (PTEN)-induced kinase 1 (PINK1) on the outer mitochondrial membrane. Here, it phosphorylates ubiquitin, leading to the recruitment of the E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin. PINK1 phosphorylation activates Parkin, which polyubiquitinates mitochondrial proteins, leading to their association with the ubiquitin-binding domains of autophagy receptors and the formation of the autophagosome. The autophagosome then fuses with the lysosome, leading to degradation of the mitochondria [18]. Alternatively, PINK1 can recruit autophagy receptors directly in a Parkin-independent manner, leading to low levels of mitophagy [18]. Parkin-mediated mitophagy can be suppressed by deubiquitination of its substrates. USP8 (Ubiquitin Specific Peptidase 8) was found to regulate mitophagy in human cell lines[19], while the reduction of USP30 [20] and USP15 [21] can increase mitophagy and rescue mitochondrial phenotypes in fly models.

Mutations in Parkin [22] and PINK1 [23] lead to the autosomal recessive form of Parkinson’s disease. PINK1−/− mice exhibit mitochondrial dysfunction, including reduced mitochondrial respiration in the striatum already at 3–4 months of age. This dysfunction was only observed in control mice at 24 months of age, indicating PINK1−/− mice are sensitive to age-related damage [24]. While Parkin−/− mice exhibit a reduction in proteins involved in mitochondrial function and oxidative stress responses, as well as mild metabolic phenotypes [25], they do not exhibit severe mitochondrial dysfunction or neuronal death, indicating the existence of Parkin-independent mitochondrial clearance pathway(s) [26]. However, when Parkin−/− mice are crossed with a PolG mutant mouse, characterized by increased mtDNA damage, the resulting phenotypes include mitochondrial dysfunction and dopaminergic neuronal loss characteristic of Parkinson’s disease [27], indicating Parkin-deficient mice are susceptible to increased mtDNA damage.

The PINK1/Parkin-dependent mitophagy pathway has been extensively studied in Drosophila [28–32]. Knockout of Pink1 in Drosophila results in sterility, mitochondrial defects, increased sensitivity to stress [33], dopaminergic neuronal loss and locomotive dysfunction [34]. These phenotypes are ameliorated by the overexpression of Parkin, suggesting that PINK1 and Parkin function in the same pathway to regulate mitochondrial maintenance [33].

Several mitophagy proteins have been reported to work in a Parkin-independent manner, including AMBRA1, Bcl2-L-13, FUNDC1, MUL1, and Nix/BNIP3L. AMBRA1 (the Activating Molecule in Beclin1-Regulated Autophagy) functions in the autophagy pathway, while also playing a pivotal role in embryogenesis and the development of the nervous system [35]. Interestingly, AMBRA1 induces mitophagy independently of Parkin and p62/SQSTM1 (a major autophagy protein) through direct binding with LC3 [36]. The BH domains of Bcl2-L-13 can independently induce mitochondrial fragmentation, while the WXXI motif binds to LC3 and facilitates mitophagy. In the absence of Parkin, Bcl2-L-13 retains its mitophagy-inducing function [37]. The integral mitochondrial outermembrane protein FUNDC1 was originally reported as a major player in hypoxia-induced mitophagy [38]. FUNDC1 can regulate mitophagy both through recruitment of LC3 via its typical LC3-binding motif Y(18)xxL(21), and by regulation of mitochondrial dynamics through interaction with fission and fusion proteins (DNM1L/DRP1 and OPA1, respectively) [38, 39]. MUL1 (mitochondrial ubiquitin ligase 1) is an E3 protein ligase that localizes onto the mitochondrial outer membrane during mitophagy [40]. In PINK1 or parkin deficient Drosophila, MUL1 can ameliorate disease phenotypes through the ubiquitin-dependent degradation of Mitofusin [40]. MUL1 can also cleave sperm-derived mitochondria in a PINK1-dependent manner in zygotes [41](detailed below). Additionally, Nix/BNIP3L can induce mitophagy in a PINK1/Parkin-independent manner [42] (also shown below). Some proteins involved in Parkin-independent mitophagy pathways, such as Ambra1, Nix, and FUNDC1, also have roles in traditional Parkin-dependent mitophagy [43–45]. Thus, in mammalian cells, there are several mitophagy pathways which can compensate for the loss of others.

In addition to the clearance of damaged mitochondria, mammals have also developed specialized mitophagy pathways to eliminate mitochondria during developmental stages such as fertilization and blood cell maturation. During the process of reticulocyte maturation into red blood cells, mitochondria are completely cleared by the Nix/BNIP3L-dependent mitophagy pathway [46] (Fig 1B). Nix is a member of the Bcl-2 family, and it induces mitophagy by decreasing mitochondrial membrane potential. Mitochondria are maternally inherited. After fertilization, paternal mitochondria are selectively degraded leaving only maternally-derived oocyte mitochondria. Deficiency in this process leads to embryonic lethality, signifying its evolutionary significance [41, 42, 47]. Elimination of sperm mitochondria in metazoan cells may require a combined action of p62-dependent autophagy and valosin-containing protein (VCP)-mediated ubiquitination of sperm mitochondria to the 26S proteasome (Fig. 1C).

In addition to the recycling of entire mitochondria, the isolation and digestion of specific damaged proteins within mitochondria can also occur. In this pathway, oxidized proteins in the mitochondrial matrix are engulfed in mitochondrial-derived vesicles (MDVs) and transported to the lysosomes [48, 49] or to peroxisomes [50]. Mitochondria-derived vesicles (MDVs) contain oxidized proteins, which may indicate protein damage or trigger protein aggregation [48]. MDV transport to the lysosome is dependent on PINK1 and Parkin [51]; however, this process is independent of other autophagic proteins such as ATG5 and LC3. MDVs may be an early response to protein damage within the mitochondria in an attempt to correct mitochondrial damage before complete degradation via mitophagy [48] (Fig. 1D).

2.2 Mitophagy in C. elegans

Decades of research in cross-species studies suggests that many of the cellular pathways involved in neuronal function and aging are evolutionally conserved. In C. elegans, mitophagy plays important roles in lifespan and healthspan [52]. The C. elegans mitochondrial protein DCT-1 (DAF-16/FOXO Controlled, germlineTumour affecting-1) is a putative orthologue to the human mitophagy protein Nix/BNIP3L. DCT-1 works downstream of the PINK1-Parkin pathway and is upregulated by the oxidative stress response transcription factor SKN-1 (ortholog of mammalian NRF2) and the FOXO transcription factor DAF-16 (ortholog of mammalian FOXO3) [52] (Fig. 1E). Additionally, as in mammals, C. elegans sperm mitochondria are eliminated. Recent work in C. elegans suggests that CPS-6, a mitochondrial endonuclease G [42, 47] is required to degrade the paternal mitochondrial genome (Fig. 1F). Further research on the mechanisms of autophagy and mitophagy in C. elegans will accelerate both mechanistic and translational studies in the fields of biological aging and neurodegeneration.

3. Mitophagy in neurodegeneration and aging

Mitochondria are key players in a wide range of pathways involved in cellular and tissue homeostasis and aging, including cellular senescence, stem cell function, inflammation, nuclear gene expression, epigenetics, calcium regulation, apoptosis, telomere maintenance, and genomic stability [9, 15, 53]. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a hallmark of aging [8], demonstrated by the cross-species accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria with age [54]. Mutations [55, 56] and deletions [57] in the mitochondrial genome accumulate with age, leading to bioenergetic dysfunction and age-related pathologies [58, 59]. Mitochondrial dysfunction can also induce senescence (termed mitochondrial dysfunction-induced senescence (“MiDAS”)), recently shown to contribute extensively to age-related pathologies [60].

In C. elegans, mitochondria accumulate with age, which may be due to a reduction in the clearing of damaged mitochondria via mitophagy [61]. Furthermore, induction of mitophagy is required for the lifespan extension of several long-lived C. elegans mutants including the IGF/IGF-1 mutants. Lifespan extension in C. elegans due to mild mitochondrial dysfunction is also mediated by mitophagy [62]. Sun et al developed the mt-keima mouse to measure mitophagy in vivo and demonstrated that mitophagy declines by approximately 70% in the Dentate gyrus, a region of the brain important for memory and learning, between 3 and 21-month old mice [63]. They also observed an increase in mitophagy in the PolG mutator mouse, associating an increase in mtDNA damage [64] with an increase in mitophagy. The authors speculate that it is not an increase in mitochondrial damage that contributes to mitochondrial-driven age-related pathologies, but rather a decline in the cellular capacity to mitigate the damage via mitophagy [63].

Neurons have an exceptionally high demand for ATP, which is needed for axonal transport, maintenance of ion gradients and membrane potential, and generation of synaptic vesicles. ATP production in neurons relies predominately on oxidative phosphorylation. Therefore, mitochondrial health is essential for neuronal function [65]. Given these unique features of neurons, the nervous system may be especially sensitive to mitochondrial damage. Dysfunctional mitophagy is closely linked to Parkinson’s disease (PD) (see section 2.1), a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by a loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra as well as the accumulation of Lewy bodies, a form of protein aggregates.

Mitochondrial dysfunction, including reduced membrane potential and respiration, is also associated with Huntington’s disease (HD) [66]. HD is an autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disorder caused by an expansion of CAG repeats in the huntingtin gene, leading to the accumulation of protein aggregates and neuronal death. It has been reported that HD mouse models have reduced activity of PGC-1α, the master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis [67] and recently found to be important in the formation of hippocampal dendritic spines and synapses [68]. A reduction in mitophagy may also contribute to mitochondrial dysfunction in HD. Furthermore, human Huntingtin’s transgene (HTT) mice crossed with the mt-keima mouse indicated reduced mitophagy in the dentate gyrus [63]. GAPDH, a protein which catalyzes the sixth step of glycolysis, also functions in the direct engulfment of damaged mitochondria by lysosomes. In normal cells, expression of expanded polyglutamine tracts oxidized inactive GAPDH (iGAPDH) to induce micro-mitophagy. Mechanistically, iGAPDH signals the induction of direct engulfment of damaged mitochondria into lysosomes. However, expanded polyglutamine repeats (mutant Huntingtin) inhibit GAPDH-induced mitophagy through abnormal interaction with GAPDH [69]. Hwang et al reported a reduction in GAPDH-induced mitophagy in HD cell models due to the inactivation of GAPDH by polyglutamine expansion[69].

Alzheimer’s disease is the most prevalent form of neurodegeneration in aging populations. It is characterized by progressive cognitive decline, memory loss, and neuronal death in the cerebral cortex. Brain sections from Alzheimer’s patients are characterized by neurofibrillary tangles composed of hyperphosphorylated tau protein and plaques of amyloid beta. Mitochondrial dysfunction is also implicated in the disease pathology [70, 71]. The activation of SIRT1 (See “Sirtuins and Mitophagy”) can reduce the amount of beta-amyloid in brain, similar to the reduction mediated by caloric restriction [72].

In addition, compromised mitophagy may also induce amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a fatal neurological disease caused by dysfunction of the motor neurons. ALS-related OPTN and TBK1 gene mutations can cause compromised mitophagy [73]. Taken together, these studies suggest that reduced mitophagy contributes to several neuro degenerative diseases and age-related neurogenerative decline.

4. Sirtuins and mitophagy

The conserved sirtuin (silent information regulator) family of proteins are a group of NAD+ dependent deacetylases that have important roles in metabolism and aging [74]. The mammalian sirtuin family consists of SIRT1-7. SIRT3-5 are predominately targeted to the mitochondria, SIRT1, SIRT6 and SIRT7 are mainly nuclear, and SIRT2 is cytoplasmic. Several excellent reviews have discussed the properties of sirtuins and their role in disease [75–77]. Sirtuin activity is generally correlated with an increase in lifespan and healthspan in yeast [78], flies [79], worms [80], and mice [81, 82]. This is in part due to increased stress response. For example, the increased resistance to oxidative stress in mouse neurons following exercise is mediated by mitochondrial SIRT3 [83]. Furthermore, huntingtin and epilepsy mouse models lacking SIRT3 were more susceptible to neurodegeneration [83]. Sirtuin enzymatic activity is dependent on cellular NAD+ levels, which decline with age across species [84]. In rats, the NAD+/NADH ratio decreases in all organs by middle age compared to young rats [85]. Similar findings were reported in human skin samples [86]. Cellular levels of NAD+ and SIRT1 activity have recently gained attention for their role in regulating mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy, and may provide novel therapeutic targets for neurodegeneration and age-related disease.

4.1 Linking energy sensing to mitochondrial homeostasis

Mitochondrial turnover and mitochondrial biogenesis must be tightly balanced in the cell to maintain energy homeostasis. This is in part regulated by the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). AMPK functions as an energy sensor, stimulating ATP production and suppressing ATP consumption in conditions of high cellular AMP/ATP ratio. AMPK promotes mitophagy through multiple mechanisms. First, AMPK phosphorylation of ULK1/ULK2 (mammalian orthologs of yeast Atg1) is required for mitophagy [87]. Since AMPK can increase intracellular NAD+ levels [88], it may also promote SIRT1-dependent mitophagy [89–91]. SIRT1 activity enhances mitophagy via FOXO signaling and promotes mitochondrial biogenesis by activating PGC-1α [90]. This pathway links energy sensing to mitochondrial homeostasis [92].

4.2 Nuclear to Mitochondrial Signaling and Mitophagy

Nuclear to mitochondrial signaling regulates mitochondrial function, and can have profound impacts on aging and disease [93]. This signaling is mediated by a network of sirtuins. NAD+ is a key metabolite consumed by sirtuins and by the DNA damage response protein poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1). PARP1 detects breaks in DNA and recruits DNA repair proteins through a process called PARylation in which PAR chains are generated and NAD+ is consumed [53, 94]. PARP1 may also participate in the detection of G4 structures [95]. The accumulation of nuclear DNA damage, which occurs with age [96], can lead to persistent activation of PARP1, which depletes cellular levels of NAD+ and reduces sirtuin activity [97]. In C. elegans, when the ortholog of PARP-1, pme-1, was knocked down, mitochondrial function improved due to increased NAD+ levels and Sir2.1 (the C. elegans ortholog of SIRT1) activity and through UPRmt activation. This resulted in lifespan extension and delayed onset of age-related phenotypes [98].

In addition to normal physiological aging, DNA repair-deficient neurodegenerative progeria diseases, including Cockayne Syndrome (CS), Xeroderma Pigmentosum group A (XPA) [99], and Ataxia Telangiectasia (AT) [100], exhibit clinical features similar to classic mitochondrial disorders such as mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, stroke-like episodes (MELAS) and Myoclonic epilepsy with ragged-red fibers (MERRF) syndromes [101]. XPA and AT demonstrate mitochondrial dysfunction due to reduced SIRT1 activity, stemming from an increase in DNA damage, persistent activation of PARP1, and depletion of NAD+[91, 102]. For example, treatment with PARP inhibitors and supplementation of NAD+ precursors attenuated mitochondrial dysfunction in XPA models and extended lifespan in xpa-1 worms [99]. Interestingly, similar results were not found in XPC models, a DNA repair disorder not associated with neurodegeneration. Taken together, these results indicate that cellular levels of NAD+ can modulate mitochondrial homeostasis and genome stability and may provide therapeutic targets for age-related neurodegeneration and neurodegenerative disease.

SIRT1 can also regulate mitochondrial homeostasis in a PGC-1α independent manner. Gomes et al demonstrated that when nuclear NAD+ declines with age, SIRT1 activity is reduced and the transcription factor HIF-1α is stabilized [103]. The authors suggest that chronic activation of HIF-1α leads to a “pseudohypoxic state” in which the transcription of mitochondrially-encoded genes is reduced, leading to an imbalance between nuclear and mitochondrial transcription, and eventually mitochondrial dysfunction. Interestingly, recent work by Jain et al demonstrated that increased HIF activity due to hypoxia ameliorated several features and dramatically increased the lifespan of mouse models of Leigh Syndrome [104]. Thus, the dual role of the HIF pathway to regulate mitochondrial health may be context-dependent and remains to be fully elucidated.

5. Therapeutic interventions that target mitophagy

Given that mitochondrial dysfunction and compromised autophagy/mitophagy can induce a wide spectrum of diseases, including neurodegenerative diseases and premature aging, pharmacological maintenance of mitophagy may have broad translational applications. First, direct activators of mitophagy machinery, such as modulators of PINK1 [105] and Parkin [106] have been shown to increase mitophagy. Activation of sirtuins through sirtuin activating compounds (STACs), has also been shown to be a viable strategy for increasing mitophagy. Drugs such as resveratrol [78] and metformin [107], both of which increase mitophagy, fall into this class. Sirtuin activity can also be mediated through supplementation of NAD+ precursors such as NR and NMN, or via inhibitors of NAD+-consumers such as PARP, both of which have been found to improve several facets of age-related decline, including neurodegeneration [108]. Recently, Mills et al reported that long term treatment of NMN delayed the onset of age-related decline in wildtype mice through enhanced energy metabolism, suppression of weight increase, and other features [109]. Mitochondrial dysfunction and defective mitophagy contribute to the severe neurodegeneration phenotypes of several DNA repair deficient premature aging diseases, such as CS, XPA, and AT. Intriguingly, NAD+ replenishment can ameliorate disease phenotypes and improve both lifespan and healthspan in C. elegans and mouse disease models.

Mitophagy can also be induced by bioactive natural compounds, such as antibiotics and plant metabolites. Actinonin is a naturally occurring antibiotic found to increase mitophagy in neuronal stem cells derived from the mt-Keima mouse [63]. The mechanism through which actinonin induces mitophagy may be linked to the depletion of mitochondrial ribosomes and RNA decay [110], although the connection between this pathway and mitochondrial quality control remains to be completely elucidated. Ryu et al recently characterized a novel mitophagy-inducer Urolithin A [4], a metabolite derived from pomegranates. Urolithin A extends the lifespan of C. elegans and improves muscle function in mice through mitochondrial maintenance via upregulation of mitophagy [111]. More work remains to be done to deduce the mechanism behind which Urolithin A increases mitophagy. In conclusion, based on the availability of different mitophagy screening animal models, including C. elegans and mice, we expect an increase in the discovery of new mitophagy-inducing compounds which will propel further potential clinical studies.

6. Conclusions and future perspectives

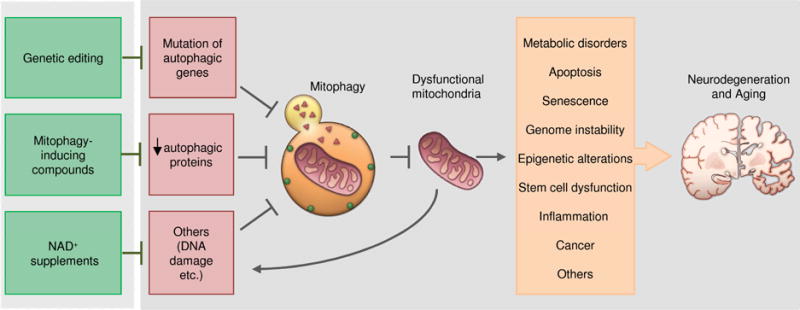

A growing body of research implicates mitophagy in neurodegenerative disease and age-related neurological decline, and provides new avenues for therapeutic intervention (Fig. 2). Although mitochondrial dysfunction has long been implicated in the pathology of neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s, Huntington’s, Alzheimer’s, and others, decreased levels of mitophagy have only recently been recognized as key contributor to disease pathogenesis. Thus, the role of mitochondrial maintenance must be elucidated to better understand the mitochondrial phenotypes in neurodegeneration. Work remains to elucidate the coordination of mitophagy with other mitochondria quality control pathways, such as the UPRmt. For instance, it is interesting to consider the different layers of mitochondrial maintenance in response to stress. In the context of a single mitochondrion, the UPRmt may serve as a first line of defense against damage, progressing to degradation of damaged proteins via mitochondria-derived vesicles, followed by recycling of the entire organelle via mitophagy. One could even consider mitochondrial dysfunction induced senescence (MiDAS) as the next phase, eventually leading to neurodegeneration and other age-related pathologies. Additionally, the roles and molecular mechanisms of mitophagy in stem cell renewal and function deserve further investigation. In summary, further mechanistic studies of mitophagy may not only improve our understanding of the mechanisms of aging, neurodegeneration, and other diseases, but also suggest novel therapeutic strategies to combat multiple devastating neurodegenerative diseases, and possibly even delay biological aging.

Fig 2. Mitophagy in neurodegeneration and aging.

Mitophagy can be inhibited by a reduction of autophagic protein activity or by depletion of metabolites such as NAD+ due to increased DNA damage and consumption or due to a decline in NAD+ synthesis. A reduction in mitophagy leads to an accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria, which can induce a variety of damage contributing to neurodegeneration and aging. These pathologies can be restored by targeting mitophagy through genetic editing, mitophagy-inducing compounds, and NAD+ supplementation.

Highlights.

Mitophagy in neurodegeneration and aging

Mitophagy is essential for the maintenance of mitochondrial quality in neurons

Compromised autophagy/mitophagy can cause neurodegenerative diseases

Different molecular pathways of mitophagy have been uncovered

Mitophagy induction can be a novel approach for the treatment of some neurodegenerative diseases

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the valuable work of the many investigators whose published articles we were unable to cite owing to space limitations. We thank Dr. Beverly Baptiste and Mr. Jesse Kerr for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Marc Raley for some of the art works. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, including a 2015–2016 NIA intra-laboratory grant (EFF/VAB).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rubinsztein DC, Mariño G, Kroemer G. Autophagy and aging. Cell. 2011;146(5):682–695. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Madeo F, Tavernarakis N, Kroemer G. Can autophagy promote longevity? Nature cell biology. 2010;12(9):842–846. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hara T, et al. Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature. 2006;441(7095):885–889. doi: 10.1038/nature04724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park D, et al. Resveratrol induces autophagy by directly inhibiting mTOR through ATP competition. Scientific reports. 2016:6. doi: 10.1038/srep21772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Komatsu M, et al. Loss of autophagy in the central nervous system causes neurodegeneration in mice. Nature. 2006;441(7095):880–884. doi: 10.1038/nature04723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menzies FM, Fleming A, Rubinsztein DC. Compromised autophagy and neurodegenerative diseases. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2015;16(6):345–357. doi: 10.1038/nrn3961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallace DC. A mitochondrial bioenergetic etiology of disease. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013;123(4):1405–1412. doi: 10.1172/JCI61398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.López-Otín C, et al. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153(6):1194–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scheibye-Knudsen M, et al. Protecting the mitochondrial powerhouse. Trends Cell Biol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lemasters JJ. Selective mitochondrial autophagy, or mitophagy, as a targeted defense against oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and aging. Rejuvenation research. 2005;8(1):3–5. doi: 10.1089/rej.2005.8.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palikaras K, Tavernarakis N. Mitophagy in neurodegeneration and aging. Frontiers in genetics. 2012;3:297. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan BJ, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and mitophagy in Parkinson’s: from familial to sporadic disease. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2015;40(4):200–210. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khalil B, et al. PINK1-induced mitophagy promotes neuroprotection in Huntington’s disease. Cell death & disease. 2015;6(1):e1617. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ye X, et al. Parkin-mediated mitophagy in mutant hAPP neurons and Alzheimer’s disease patient brains. Human molecular genetics. 2015;24(10):2938–2951. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun N, Youle RJ, Finkel T. The mitochondrial basis of aging. Molecular cell. 2016;61(5):654–666. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Youle RJ, Narendra DP. Mechanisms of mitophagy. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2011;12(1):9–14. doi: 10.1038/nrm3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pickrell AM, Youle RJ. The roles of PINK1 parkin, and mitochondrial fidelity in Parkinson’s disease. Neuron. 2015;85(2):257–273. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lazarou M, et al. The ubiquitin kinase PINK1 recruits autophagy receptors to induce mitophagy. Nature. 2015;524(7565):309–14. doi: 10.1038/nature14893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durcan TM, et al. USP8 regulates mitophagy by removing K6-linked ubiquitin conjugates from parkin. The EMBO journal. 2014:e201489729. doi: 10.15252/embj.201489729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bingol B, et al. The mitochondrial deubiquitinase USP30 opposes parkin-mediated mitophagy. Nature. 2014;510(7505):370–375. doi: 10.1038/nature13418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cornelissen T, et al. The deubiquitinase USP15 antagonizes Parkin-mediated mitochondrial ubiquitination and mitophagy. Human molecular genetics. 2014:ddu244. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kitada T, et al. Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature. 1998;392(6676):605–608. doi: 10.1038/33416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valente EM, et al. Hereditary early-onset Parkinson’s disease caused by mutations in PINK1. Science. 2004;304(5674):1158–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1096284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gautier CA, Kitada T, Shen J. Loss of PINK1 causes mitochondrial functional defects and increased sensitivity to oxidative stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105(32):11364–11369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802076105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palacino JJ, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage in parkin-deficient mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(18):18614–18622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401135200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perez FA, Palmiter RD. Parkin-deficient mice are not a robust model of parkinsonism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(6):2174–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409598102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pickrell AM, et al. Endogenous Parkin preserves dopaminergic substantia nigral neurons following mitochondrial DNA mutagenic stress. Neuron. 2015;87(2):371–381. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greene JC, et al. Mitochondrial pathology and apoptotic muscle degeneration in Drosophila parkin mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(7):4078–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0737556100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang Y, et al. Mitochondrial pathology and muscle and dopaminergic neuron degeneration caused by inactivation of Drosophila Pink1 is rescued by Parkin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(28):10793–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602493103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deng H, et al. The Parkinson’s disease genes pink1 and parkin promote mitochondrial fission and/or inhibit fusion in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(38):14503–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803998105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poole AC, et al. The PINK1/Parkin pathway regulates mitochondrial morphology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(5):1638–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709336105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang Y, et al. Pink1 regulates mitochondrial dynamics through interaction with the fission/fusion machinery. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(19):7070–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711845105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clark IE, et al. Drosophila pink1 is required for mitochondrial function and interacts genetically with parkin. Nature. 2006;441(7097):1162–1166. doi: 10.1038/nature04779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park J, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Drosophila PINK1 mutants is complemented by parkin. Nature. 2006;441(7097):1157–1161. doi: 10.1038/nature04788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fimia GM, et al. Ambra1 regulates autophagy and development of the nervous system. Nature. 2007;447(7148):1121–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strappazzon F, et al. AMBRA1 is able to induce mitophagy via LC3 binding, regardless of PARKIN and 62/SQSTM1. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22(3):517. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murakawa T, et al. Bcl-2-like protein 13 is a mammalian Atg32 homologue that mediates mitophagy and mitochondrial fragmentation. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7527. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu L, et al. Mitochondrial outer-membrane protein FUNDC1 mediates hypoxia-induced mitophagy in mammalian cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(2):177–85. doi: 10.1038/ncb2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen M, et al. Mitophagy receptor FUNDC1 regulates mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy. Autophagy. 2016;12(4):689–702. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1151580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yun J, et al. MUL1 acts in parallel to the PINK1/parkin pathway in regulating mitofusin and compensates for loss of PINK1/parkin. Elife. 2014;3:e01958. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rojansky R, Cha M-Y, Chan DC. Elimination of paternal mitochondria in mouse embryos occurs through autophagic degradation dependent on PARKIN and MUL1. eLife. 2016;5:e17896. doi: 10.7554/eLife.17896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song WH, et al. Autophagy and ubiquitin-proteasome system contribute to sperm mitophagy after mammalian fertilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(36):E5261–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605844113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Humbeeck C, et al. Parkin interacts with Ambra1 to induce mitophagy. J Neurosci. 2011;31(28):10249–61. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1917-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ding WX, et al. Nix is critical to two distinct phases of mitophagy, reactive oxygen species-mediated autophagy induction and Parkin-ubiquitin-62-mediated mitochondrial priming. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(36):27879–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.119537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu W, et al. ULK1 translocates to mitochondria and phosphorylates FUNDC1 to regulate mitophagy. EMBO Rep. 2014;15(5):566–75. doi: 10.1002/embr.201438501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sandoval H, et al. Essential role for Nix in autophagic maturation of erythroid cells. Nature. 2008;454(7201):232–5. doi: 10.1038/nature07006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou Q, et al. Mitochondrial endonuclease G mediates breakdown of paternal mitochondria upon fertilization. Science. 2016;353(6297):394–9. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf4777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sugiura A, et al. A new pathway for mitochondrial quality control: mitochondrial-derived vesicles. The EMBO journal. 2014:e201488104. doi: 10.15252/embj.201488104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Soubannier V, et al. A vesicular transport pathway shuttles cargo from mitochondria to lysosomes. Current Biology. 2012;22(2):135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Neuspiel M, et al. Cargo-selected transport from the mitochondria to peroxisomes is mediated by vesicular carriers. Current Biology. 2008;18(2):102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McLelland GL, et al. Parkin and PINK1 function in a vesicular trafficking pathway regulating mitochondrial quality control. The EMBO journal. 2014:e201385902. doi: 10.1002/embj.201385902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Palikaras K, Lionaki E, Tavernarakis N. Coordination of mitophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis during ageing in C. elegans. Nature. 2015;521(7553):525–8. doi: 10.1038/nature14300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fang EF, et al. Nuclear DNA damage signalling to mitochondria in ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17(5):308–21. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wallace DC. Mitochondrial diseases in man and mouse. Science. 1999;283(5407):1482–1488. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hudson E, et al. Age-associated change in mitochondrial DNA damage. Free radical research. 1998;29(6):573–579. doi: 10.1080/10715769800300611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fayet G, et al. Ageing muscle: clonal expansions of mitochondrial DNA point mutations and deletions cause focal impairment of mitochondrial function. Neuromuscular Disorders. 2002;12(5):484–493. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(01)00332-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Corral-Debrinski M, et al. Mitochondrial DNA deletions in human brain: regional variability and increase with advanced age. Nature genetics. 1992;2(4):324–329. doi: 10.1038/ng1292-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bratic A, Larsson N-G. The role of mitochondria in aging. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013;123(3):951–957. doi: 10.1172/JCI64125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Larsson NG. Somatic mitochondrial DNA mutations in mammalian aging. Annual review of biochemistry. 2010;79:683–706. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060408-093701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wiley CD, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction induces senescence with a distinct secretory phenotype. Cell metabolism. 2016;23(2):303–314. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Palikaras K, Lionaki E, Tavernarakis N. Coordination of mitophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis during ageing in C. elegans. Nature. 2015;521(7553):525–528. doi: 10.1038/nature14300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schiavi A, et al. Iron-starvation-induced mitophagy mediates lifespan extension upon mitochondrial stress in C. elegans. Current Biology. 2015;25(14):1810–1822. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sun N, et al. Measuring in vivo mitophagy. Molecular cell. 2015;60(4):685–696. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Trifunovic A, et al. Premature ageing in mice expressing defective mitochondrial DNA polymerase. Nature. 2004;429(6990):417–423. doi: 10.1038/nature02517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rugarli EI, Langer T. Mitochondrial quality control: a matter of life and death for neurons. The EMBO journal. 2012;31(6):1336–1349. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bossy-Wetzel E, Petrilli A, Knott AB. Mutant huntingtin and mitochondrial dysfunction. Trends in neurosciences. 2008;31(12):609–616. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weydt P, et al. Thermoregulatory and metabolic defects in Huntington’s disease transgenic mice implicate PGC-1α in Huntington’s disease neurodegeneration. Cell metabolism. 2006;4(5):349–362. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cheng A, et al. Involvement of PGC-1α in the formation and maintenance of neuronal dendritic spines. Nature communications. 2012;3:1250. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hwang S, Disatnik MH, Mochly-Rosen D. Impaired GAPDH-induced mitophagy contributes to the pathology of Huntington’s disease. EMBO molecular medicine. 2015;7(10):1307–1326. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201505256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Casley C, et al. β-Amyloid fragment 25–35 causes mitochondrial dysfunction in primary cortical neurons. Neurobiology of disease. 2002;10(3):258–267. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kerr JS, et al. Mitophagy and Alzheimer’s disease: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Trends Neurosci. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2017.01.002. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Qin W, et al. Neuronal SIRT1 activation as a novel mechanism underlying the prevention of Alzheimer disease amyloid neuropathology by calorie restriction. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(31):21745–21754. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602909200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Moore AS, Holzbaur EL. Dynamic recruitment and activation of ALS-associated TBK1 with its target optineurin are required for efficient mitophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(24):E3349–58. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1523810113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Houtkooper RH, Pirinen E, Auwerx J. Sirtuins as regulators of metabolism and healthspan. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 2012;13(4):225–238. doi: 10.1038/nrm3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Imai S-i, Guarente L. NAD+ and sirtuins in aging and disease. Trends in cell biology. 2014;24(8):464–471. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Imai S-i, Guarente L. It takes two to tango: NAD+ and sirtuins in aging/longevity control. npj Aging and Mechanisms of Disease. 2016;2:16017. doi: 10.1038/npjamd.2016.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Haigis MC, Sinclair DA. Mammalian sirtuins: biological insights and disease relevance. Annual review of pathology. 2010;5:253. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Howitz KT, et al. Small molecule activators of sirtuins extend Saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan. Nature. 2003;425(6954):191–196. doi: 10.1038/nature01960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bauer JH, et al. dSir2 and Dmp53 interact to mediate aspects of CR-dependent life span extension in D. melanogaster. Aging. 2009;1(1):38. doi: 10.18632/aging.100001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tissenbaum HA, Guarente L. Increased dosage of a sir-2 gene extends lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2001;410(6825):227–230. doi: 10.1038/35065638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kanfi Y, et al. The sirtuin SIRT6 regulates lifespan in male mice. Nature. 2012;483(7388):218–221. doi: 10.1038/nature10815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Boily G, et al. SirT1 regulates energy metabolism and response to caloric restriction in mice. PLoS One. 2008;3(3):e1759. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cheng A, et al. Mitochondrial SIRT3 mediates adaptive responses of neurons to exercise and metabolic and excitatory challenges. Cell metabolism. 2016;23(1):128–142. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cantó C, Menzies KJ, Auwerx J. NAD+ metabolism and the control of energy homeostasis: A balancing act between mitochondria and the nucleus. Cell metabolism. 2015;22(1):31–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Braidy N, et al. Age related changes in NAD+ metabolism oxidative stress and Sirt1 activity in wistar rats. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e19194. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 86.Massudi H, et al. Age-associated changes in oxidative stress and NAD+ metabolism in human tissue. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e42357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Egan DF, et al. Phosphorylation of ULK1 (hATG1) by AMP-activated protein kinase connects energy sensing to mitophagy. Science. 2011;331(6016):456–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1196371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cantó C, et al. AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD+ metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature. 2009;458(7241):1056–1060. doi: 10.1038/nature07813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fang EF, et al. Defective mitophagy in XPA via PARP-1 hyperactivation and NAD(+)/SIRT1 reduction. Cell. 2014;157(4):882–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fang EF, et al. NAD+ replenishment improves lifespan and healthspan in Ataxia telangiectasia models via mitophagy and DNA repair. Cell Metabolism. 2016;24(4):566–581. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fang EF, Bohr VA. NAD+: The convergence of DNA repair and mitophagy. Autophagy. 2016:1–2. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1257467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mihaylova MM, Shaw RJ. The AMPK signalling pathway coordinates cell growth, autophagy and metabolism. Nature cell biology. 2011;13(9):1016–1023. doi: 10.1038/ncb2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fang EF, et al. Nuclear DNA damage signalling to mitochondria in ageing. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2016;17(5):308–321. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kameshita I, et al. Poly (ADP-Ribose) synthetase. Separation and identification of three proteolytic fragments as the substrate-binding domain, the DNA-binding domain, and the automodification domain. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1984;259(8):4770–4776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Scheibye-Knudsen M, et al. Cockayne syndrome group A and B proteins converge on transcription-linked resolution of non-B DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(44):12502–12507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1610198113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chow H-m, Herrup K. Genomic integrity and the ageing brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nrn4020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gibson BA, Kraus WL. New insights into the molecular and cellular functions of poly (ADP-ribose) and PARPs. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2012;13(7):411–424. doi: 10.1038/nrm3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mouchiroud L, et al. The NAD+/sirtuin pathway modulates longevity through activation of mitochondrial UPR and FOXO signaling. Cell. 2013;154(2):430–441. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fang EF, et al. Defective mitophagy in XPA via PARP-1 hyperactivation and NAD+/SIRT1 reduction. Cell. 2014;157(4):882–896. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fang EF, et al. NAD+ Replenishment Improves Lifespan and Healthspan in Ataxia Telangiectasia Models via Mitophagy and DNA Repair. Cell metabolism. 2016;24(4):566–581. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Scheibye-Knudsen M, et al. A novel diagnostic tool reveals mitochondrial pathology in human diseases and aging. Aging (Albany NY) 2013;5(3):192–208. doi: 10.18632/aging.100546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chen S, et al. RAD6 promotes homologous recombination repair by activating the autophagy-mediated degradation of heterochromatin protein HP1. Mol Cell Biol. 2015;35(2):406–16. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01044-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gomes AP, et al. Declining NAD+ induces a pseudohypoxic state disrupting nuclear-mitochondrial communication during aging. Cell. 2013;155(7):1624–1638. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jain IH, et al. Hypoxia as a therapy for mitochondrial disease. Science. 2016;352(6281):54–61. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hertz NT, et al. A neo-substrate that amplifies catalytic activity of parkinson’s-disease-related kinase PINK1. Cell. 2013;154(4):737–747. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hasson SA, et al. Chemogenomic profiling of endogenous PARK2 expression using a genome-edited coincidence reporter. ACS chemical biology. 2015;10(5):1188–1197. doi: 10.1021/cb5010417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Song YM, et al. Metformin alleviates hepatosteatosis by restoring SIRT1-mediated autophagy induction via an AMP-activated protein kinase-independent pathway. Autophagy. 2015;11(1):46–59. doi: 10.4161/15548627.2014.984271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bonkowski MS, Sinclair DA. Slowing ageing by design: the rise of NAD+ and sirtuin-activating compounds. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Mills KF, et al. Long-term administration of nicotinamide mononucleotide mitigates age-associated physiological decline in mice. Cell Metabolism. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Richter U, et al. A mitochondrial ribosomal and RNA decay pathway blocks cell proliferation. Current Biology. 2013;23(6):535–541. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ryu D, et al. Urolithin A induces mitophagy and prolongs lifespan in C. elegans and increases muscle function in rodents. Nature Medicine. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nm.4132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]