Abstract

Background

It has been suggested that the quantity of exposure to general practice teaching at medical school is associated with future choice of a career as a GP.

Aim

To examine the relationship between general practice exposure at medical school and the percentage of each school’s graduates appointed to a general practice training programme after foundation training (postgraduate years 1 and 2).

Design and setting

A quantitative study of 29 UK medical schools.

Method

The UK Foundation Programme Office (UKFPO) destination surveys of 2014 and 2015 were used to determine the percentage of graduates of each UK medical school who were appointed to a GP training programme after foundation year 2. The Spearman rank correlation was used to examine the correlation between these data and the number of sessions spent in placements in general practice at each medical school.

Results

A statistically significant association was demonstrated between the quantity of authentic general practice teaching at each medical school and the percentage of its graduates who entered GP training after foundation programme year 2 in both 2014 (correlation coefficient [r] 0.41, P = 0.027) and 2015 (r 0.3, P = 0.044). Authentic general practice teaching here is described as teaching in a practice with patient contact, in contrast to non-clinical sessions such as group tutorials in the medical school.

Discussion

The authors have demonstrated, for the first time in the UK, an association between the quantity of clinical GP teaching at medical school and entry to general practice training. This study suggests that an increased use of, and investment in, undergraduate general practice placements would help to ensure that the UK meets its target of 50% of medical graduates entering general practice.

Keywords: career destination; education; general practice; undergraduate teaching; students, medical

INTRODUCTION

The Department of Health has set a target of 50% of postgraduate medical training places to be allocated to general practice.1 However, the proportion of UK medical graduates who intend to enter general practice is well below this target, and the proportion is decreasing rather than increasing;2,3 17.4% of foundation year 2 doctors (F2s) were appointed to GP training in 2015.4 Data from The UK Foundation Programme Office (UKFPO) also highlight a variation (7.3–30%) in the proportion of graduates from UK medical schools who enter general practice training post-foundation year 2.4

Undergraduate medical education influences student career choice,5,6 and it is important that universities accept that they have a responsibility to promote general practice as a career to medical students.7,8 The vast majority of undergraduate medical education in the UK has traditionally occurred in a secondary care setting.9 The Royal College of General Practitioners first pushed for primary care involvement in 1952, but it took more than 30 years for significant increases to be seen,10,11 with recent calls to expand this further.6,12 Some of the newer medical schools are innovative in this respect, delivering up to one-third of their curriculum in the community.13

A number of factors underlie the desire for more teaching in the community. Firstly, learning experiences in hospitals can be hampered by shorter inpatient stays, increasing sub-specialisation, lack of supervision,14 and increasing regulation. Second, learning experiences in the community are increasingly perceived as fulfilling many of the key objectives for medical student learning.12,15

It has been suggested, and even presumed, that the quantity of exposure to general practice teaching at medical school is associated with future general practice career destination.11,16 However, others have questioned this,17 and the drivers of career choices while students are at medical school are undoubtedly complex.18

The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between the amount of time spent in primary care as a medical undergraduate, and subsequent appointment to a general practice training programme post-foundation training. If such a link were confirmed, it would strengthen the call for increased exposure of medical students to general practice in helping to fulfil the Department of Health mandate.

METHOD

Data collection

The following question set was sent via email to the current heads of general practice teaching at all 31 UK medical schools. The original email was sent on 25 February 2016 and a reminder on the 9 March 2016:

‘What exposure to primary and community care did your 2008 entry students experience (list in as much detail as needed)? Was this identical to the 2007 entry students (if not, how did it differ)?’

How this fits in

It is known that undergraduate medical education influences student career choices, and that a large proportion of undergraduate medical teaching is delivered in the secondary care setting. Currently, there is a great shortage of doctors entering general practice training. The Department of Health in England has set a target of 50% of postgraduate medical training places to be allocated to general practice, a target that has been challenging to meet. This study has shown an association between increased undergraduate general practice exposure at medical school and more graduates entering general practice training. Medical schools therefore need to seriously consider their role in addressing the service needs of the nation, the GP recruitment crisis, and the contributions they can make through revising their courses.

The data were returned via email and the universities that had not responded were prompted to reply, until a 100% response rate was achieved. Data from two schools were excluded: one because it is a new school with no available UK Foundation Programme Office (UKFPO) data, and the other as it is a graduate entry only school. Internationally, there is evidence that medical students who are graduates19 and mature20,21 are more likely to choose careers in general or family practice, or in rural and shortage specialties.22

The information submitted by each medical school was reviewed, and the total number of clinical or ‘authentic’ sessions18 (such as teaching in a practice with patient contact) and non-clinical sessions (such as group tutorials in the medical school) was determined for each school. A session was defined as a half day but the number of hours was not specified. Analysis was based on the number of sessions and not the number of days. The UKFPO destination surveys of 2014 and 2015 23,4 were used to determine the percentage of foundation doctors who were appointed to a general practice training programme for each UK medical school.

Analysis

Spearman’s rank correlation was used to examine the correlation between the number of sessions spent in clinical placements in general practice (authentic placements) and all teaching sessions delivered by general practice teachers at each medical school, and the percentage of F2 graduates who were appointed to general practice training programmes 2 years after graduation. The data from the 2007 entry students were correlated with the 2014 destination survey results, and the 2008 entry students compared with the 2015 destination surveys. The majority, although not all, of the students would have completed 5 years as an undergraduate and then subsequently 2 years as a foundation doctor.

RESULTS

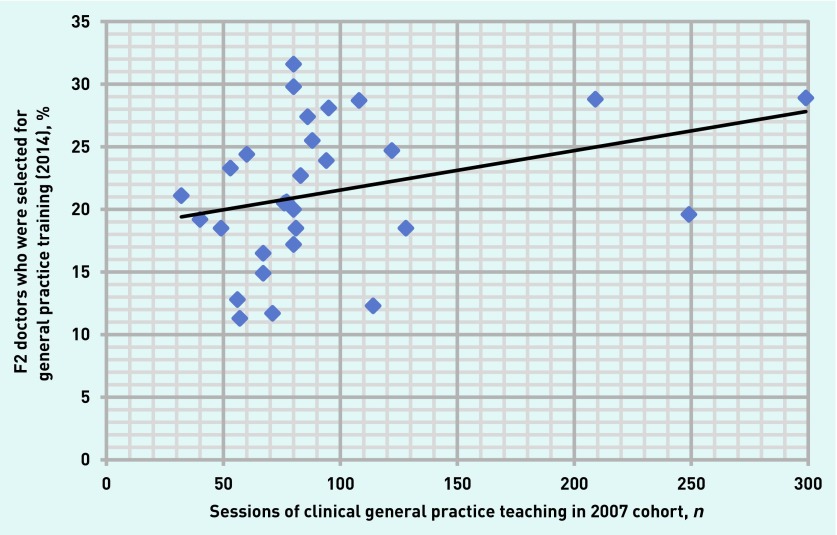

Data from 29 medical schools were included in the analysis. The median total number of sessions spent in general practice per medical school was 106 (range 44–376, interquartile range [IQR] 83–158), and the median number of authentic general practice sessions was 80 (range 32–299, IQR 67–95). No schools reported any changes in the number of sessions for the entry years 2007 and 2008. The median percentage of F2 graduates selected for general practice training per medical school in 2014 was 20.6% (range 11.3–31.6%, IQR 18.5–25.5%), and in 2015, 17.5% (range 7.3–0%, IQR 12.6–22.2%). A statistically significant association was demonstrated between the quantity of authentic general practice teaching per medical school and the percentage of their F2 graduates who selected general practice training programmes in both 2014 (correlation coefficient [r] 0.41, P = 0.027) and 2015 (r 0.3, P = 0.044). (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Scatter diagram of the number of sessions of clinical (authentic) placements in general practice for the 2007 entry cohort, against the proportion of F2s who were selected for general practice training in 2014 per medical school.

Figure 2.

Scatter diagram of the number of sessions of clinical (authentic) placements in general practice for the 2008 entry cohort, against the proportion of F2s who were selected for general practice training in 2015 per medical school.

Comparison of total general practice teaching exposure — which includes, for example, small group teaching in the medical school provided by GPs — with the percentage of F2s appointed to general practice training programmes for 2014 and 2015 demonstrated a non-significant association (r 0.32, P = 0.085, and r 0.23, P = 0.227, respectively).

DISCUSSION

Summary

The authors have clearly demonstrated, for the first time in the UK, an association between the quantity of clinical general practice teaching at medical school and later career destination of general practice after foundation training. This association, previously presumed but not demonstrated, has serious implications for medical schools and the Department of Health. It supports the stance adopted by House of Commons Committee report of April 2016 that:

‘Medical schools should recognise that they have a responsibility to patients to educate and prepare half of all graduates for careers in general practice … Those medical schools that do not adequately teach primary care as a subject, or fall behind in the number of graduates choosing GP training, should be held to account by the General Medical Council.’ 8

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is that the authors have included data from all UK medical schools with an undergraduate entry in the relevant time frame. This improves the validity of the data when applied to UK medical schools. In addition, this is the first published study to review the association between the amount of time spent in primary care as a medical undergraduate, and subsequent appointment to a general practice training programme after foundation training, and to look at a national, as opposed to a regional or single school, dataset.

Potential limitations of the study need to be recognised. Association does not prove causation and it can be reasonably hypothesised that potential medical students who are attracted to general practice as a career may be attracted to medical schools known to provide more teaching in primary care. The statistical association found would suggest that other factors are also implicated, and certainly the striking variation of graduates appointed to general practice training programmes across the medical schools has been highlighted and is worthy of further exploration.6 The data collection relies on the accuracy of submissions from each medical school and, in integrated curricula, schools may be unable to accurately attribute clinical course time clearly to general practice or hospital. In this analysis, the authors have assumed that all students graduated 5 years after entry, and so it ignores the effects of 4-year graduate entry courses in schools with parallel 4-and 5-year courses, 6-year courses with an intercalated degree, intercalation, and resits. The authors consider that this is reasonable, given that the pace of curricular change is slow. They have also relied on data for F2 doctors. Many will select general practice as a career later, but there is no reason to suggest why this would vary across medical schools. Finally, the authors have demonstrated a relationship between exposure and the percentage of F2 doctors appointed to general practice training programmes and used this as a proxy for career choice. The authors are aware that there may be factors other than the candidate’s choice that determine their final career outcome, such as selection procedures and competition rates.

Comparison with existing literature

Until now, the empirical UK literature on career choices has either been that of Goldacre’s group,2,3,24–27 which was based on national surveys of postgraduate career intentions and choice, or smaller quantitative and qualitative studies.18,28 Internationally, evaluations of the impact of medical curricula have demonstrated that embedding medical education in underserved (usually rural) communities, and targeted recruitment to medical school from those communities, has increased the number of graduates who choose to return to practice in those communities.29–34

This is the first study to demonstrate an association between the number of sessions students spend in authentic placements in general practice and the likelihood of them entering general practice training.

Implications for research and practice

Further research is needed to confirm or refute the association identified, to explore what factors within ‘authentic teaching’ may be relevant, and to further interrogate the intertwining factors of recruitment and teaching exposure. Nicholson and colleagues18 have started that exploration, but as they observe, further work is needed to fully understand the factors (of which the medical curriculum and exposure to general practice are two) which impact on eventual career choice.

Nevertheless, in order to reflect the changing landscape of health care, universities need to urgently consider means to increase the amount of primary care exposure within their curriculum. This study suggests that an increased percentage of medical undergraduate funding should be directed towards general practice placements to address the crisis in recruitment to primary medical care. Furthermore, because of the uncertain and complex funding arrangements currently in place within medical schools, the authors recommend that this money be ringfenced to ensure that it reaches its intended destination safely.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the general practice heads of teaching at the medical schools who responded to the questions. They are also grateful to Sammy Mansour and Hannah Marshall for preparation work towards the study, and to James Somauroo for providing some of the background literature.

Funding

None given.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Provenance

Freely given; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

All of the authors are GPs who believe that general practice can, and should, make a major contribution to undergraduate medical teaching. No other competing interests have been declared.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Department of Health Delivering high quality, effective, compassionate care: Developing the right people with the right skills and the right values. A mandate from the Government to Health Education England: April 2015 to March 2016. 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/411200/HEE_Mandate.pdf (accessed 16 Feb 2016).

- 2.Lambert T, Goldacre M. Trends in doctors’ early career choices for general practice in the UK: longitudinal questionnaire surveys. Br J Gen Pract. 2011. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp11X583173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Svirko E, Goldacre M, Lambert T. Career choices of the UK-qualified medical graduates of 2005, 2008 and 2009: questionnaire surveys. Med Teach. 2013;35:365–375. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.746450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The UK Foundation Programme Office F2 career destination report 2015. http://www.foundationprogramme.nhs.uk/download.asp?file=F2_Career_Destination_Report_2015_-_FINAL.pdf (accessed 16 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howe A, Ives G. Does community-based experience alter career preference? New evidence from a prospective longitudinal cohort study of undergraduate medical students. Med Educ. 2001;35(4):391–397. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDonald P, Jackson B, Alberti H, Rosenthal J. How can medical schools encourage students to choose general practice as a career? Br J Gen Pract. 2016. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp16X685297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Verma P, Ford J, Stuart A, et al. A systematic review of strategies to recruit and retain primary care doctors. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:126. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1370-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.House of Commons Health Committee Primary care: fourth report of session 2015–2016. 2016. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201516/cmselect/cmhealth/408/408.pdf (accessed 16 Jan 2017).

- 9.Seabrook M, Lempp H, Woodfield SJ. Extending community involvement in the medical curriculum: lessons from a case study. Med Educ. 1999;33(11):838–845. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oswald N. Why not base clinical education in general practice? Lancet. 1989;334:148–149. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90195-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harding A, Rosenthal J, Al-Seaidy M, et al. Society for Academic Primary Care (SAPC) Heads of Teaching Group. Provision of medical student teaching in UK general practices: a cross sectional study. Br J Gen Pract. 2015. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp15X685321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Park S, Khan NF, Hampshire M, et al. A BEME systematic review of UK undergraduate medical education in the general practice setting: BEME Guide No. 32. Med Teach. 2015 May 6;:1–20. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1032918. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wass V. Undergraduate learning. Educ Prim Care. 2008;19(4):446–448. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Worley P, Prideaux D, Strasser R, et al. Empirical evidence for symbiotic medical education: a comparative analysis of community and tertiary-based programmes. Med Educ. 2006;40(2):109–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pearson DJ, McKinley RK. Why tomorrow’s doctors need primary care today. J R Soc Med. 2010;103(1):9–13. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2009.090182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zink T, Center B, Finstad D, et al. Efforts to graduate more primary care physicians and physicians who will practice in rural areas: examining outcomes from the University of Minnesota–Duluth and the Rural Physician Associate Program. Acad Med. 2010;85(4):599–604. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d2b537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lancaster T. Editor’s choice. Letters. Br J Gen Pract. 2015. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp15X685561.

- 18.Nicholson S, Hastings AM, McKinley RK. Influences on students’ career decisions concerning general practice: a focus group study. Br J Gen Pract. 2016. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp16X687049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Shelker W, Belton A, Glue P. Academic performance and career choices of older medical students at the University of Otago. N Z Med J. 2011;124(1346):63–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennett KL, Phillips JP. Finding, recruiting, and sustaining the future primary care physician workforce: a new theoretical model of specialty choice process. Acad Med. 2010;85(10 Suppl):S81–88. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ed4bae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vanasse A, Orzanco MG, Courteau J, Scott S. Attractiveness of family medicine for medical students. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(6):e216–227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hays RB, Lockhart KR, Teo E, et al. Full medical program fees and medical student career intention. Med J Aust. 2015;202(1):46–49. doi: 10.5694/mja14.00454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The UK Foundation Programme Office F2 Career Destination Report 2014. http://www.foundationprogramme.nhs.uk/download.asp?file=F2_career_destination_report_2014_-_FINAL_-_App_A_updated.pdf (accessed 16 Jan 2017).

- 24.Maisonneuve JJ, Lambert TW, Goldacre MJ. Doctors views about training and future careers expressed one year after graduation by UK-trained doctors: questionnaire surveys undertaken in 2009 and 2010. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:270. doi: 10.1186/s12909-014-0270-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldacre MJ, Turner G, Lambert TW. Variation by medical school in career choices of UK graduates of 1999 and 2000. Med Educ. 2004;38(3):249–258. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2004.01763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lambert TW, Goldacre MJ, Parkhouse J, Edwards C. Career destinations in 1994 of United Kingdom medical graduates of 1983: results of a questionnaire survey. BMJ. 1996;312(7035):893–897. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7035.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lambert TW, Goldacre MJ, Edwards C, Parkhouse J. Career preferences of doctors who qualified in the United Kingdom in 1993 compared with those of doctors qualifying in 1974, 1977, 1980 and 1983. BMJ. 1996;313(7048):19–24. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7048.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cleland JA, Johnston PW, Anthony M, et al. A survey of factors influencing career preference in new-entrant and exiting medical students from four UK medical schools. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:151. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-14-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Straume K, Shaw DMP. Effective physician retention strategies in Norway’s northernmost county. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:390–394. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.072686. http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/88/5/09-072686/en/ (accessed 16 Feb 2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Worley P, Murray R. Social accountability in medical education — an Australian rural and remote perspective. Med Teach. 2011;33(8):654–658. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.590254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strasser R, Neusy A-J. Context counts: training health workers in and for rural and remote areas. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(10):777–782. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.072462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smucny J, Beatty P, Grant W, et al. An evaluation of the rural Medical Education Program of the State University Of New York Upstate Medical University, 1990–2003. Acad Med. 2005;80(8):733–738. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200508000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Viscomi M, Larkins S, Gupta TS. Recruitment and retention of general practitioners in rural Canada and Australia: a review of the literature. Can J Rural Med. 2013;18(1):13–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pfarrwaller E, Sommer J, Chung C, et al. Impact of interventions to increase the proportion of medical students choosing a primary care career: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(9):1349–1358. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3372-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]