Abstract

Background

The numbers of GPs and training places in general practice are declining, and retaining GPs in their practices is an increasing problem.

Aim

To identify evidence on different approaches to retention and recruitment of GPs, such as intrinsic versus extrinsic motivational determinants.

Design and setting

Synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research using seven electronic databases from 1990 onwards (Medline, Embase, Cochrane Library, Health Management Information Consortium [HMIC], Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (Cinahl), PsycINFO, and the Turning Research Into Practice [TRIP] database).

Method

A qualitative approach to reviewing the literature on recruitment and retention of GPs was used. The studies included were English-language studies from Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development countries. The titles and abstracts of 138 articles were reviewed and analysed by the research team.

Results

Some of the most important determinants to increase recruitment in primary care were early exposure to primary care practice, the fit between skills and attributes, and a significant experience in a primary care setting. Factors that seemed to influence retention were subspecialisation and portfolio careers, and job satisfaction. The most important determinants of recruitment and retention were intrinsic and idiosyncratic factors, such as recognition, rather than extrinsic factors, such as income.

Conclusion

Although the published evidence relating to GP recruitment and retention is limited, and most focused on attracting GPs to rural areas, the authors found that there are clear overlaps between strategies to increase recruitment and retention. Indeed, the most influential factors are idiosyncratic and intrinsic to the individuals.

Keywords: general practice; intrinsic motivation; job satisfaction; primary health care; recruitment; retention; review, systematic

INTRODUCTION

The UK government and professional bodies have become increasingly concerned about the declining numbers of GPs. The reasons for this are thought to be related to problems in training, low GP morale, increasing workload pressures on practices, challenges of changing roles, and reductions in pay.1–4

The number of GPs per 100 000 head of population across England declined from 62 in 2009 to 59.5 in 2012.5 Despite Department of Health policy to increase GP training numbers in England to 3250 per annum, GP recruitment has remained persistently below this target, at around 2700 per annum, and since 2005 there has been a gradual decline in the percentage of students choosing general practice as a first choice.6 Despite a recruitment record of 2989 in 2015–2016, Health Education England () missed their recruitment goal of 3250 new GP trainees.7 Although applications for general practice post-qualifying have substantially increased in 2016, the problem remains in some areas, such as in the North East, North West, and Midlands.7,8 This reduction is set against an increasing GP workload due to changing health needs and policies designed to develop more primary and community-based health care.9–12

Additional pressure arises from an increase in the numbers of GPs leaving general practice, including an increase in those considering practising abroad.13,14 Together, under-recruitment of GPs and increased propensity to leave are key factors in the current GP shortage. To address this, NHS England — working with HEE, the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP), and the British Medical Association (BMA) — in 2015 published Building the Workforce — the New Deal for General Practice,15 where they presented the 10-point plan, then in 2016 the General Practice Forward View,16 both proposing strategies to increase recruitment and reduce turnover in general practice through specific initiatives and further investment in general practice.

As part of the development work for reviewing the 10-point plan and NHS England’s strategy, the Policy Research Unit in Commissioning and the Healthcare System (PRUComm) was asked to review the existing evidence on GP recruitment and retention.17 The review explored the main dimensions related to recruitment and retention of GPs to identify the intrinsic and extrinsic motivational factors connected to career choices and retention. This study reports on the main findings of the review.

METHOD

To identify relevant evidence, the authors undertook a structured review that synthesised the evidence from reviews on primary care physician recruitment and retention from countries with similar health systems to the UK (for example, Canada and Australia), and UK studies specifically examining GP recruitment and retention and GP training (search terms are outlined in Appendix 1). Articles published in English from 1990 onwards were included.

How this fits in

To support the work of NHS England and Health Education England on the development of the Five Year Forward View, the Department of Health commissioned a review of the evidence of the 10-point plan from Building the Workforce — the New Deal for General Practice from the Policy Research Unit in Commissioning and the Healthcare System. The review examined the evidence on GP recruitment and retention determinants, and found that intrinsic and idiosyncratic factors, such as job satisfaction, were more important than extrinsic factors, such as financial incentives.

Following an initial review, the terms were searched as keywords (appearing in title, abstract, subject, and keyword heading fields) and also mapped against MeSH subject headings, where applicable, to ensure comprehensive coverage. The databases searched were Medline, Embase, Cochrane Library, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (Cinahl), PsycINFO, and the Turning Research Into Practice (TRIP) database (an internet-based source of evidence-based research). The literature search included all journal articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, review articles, reports, and grey literature (Table 1 contains the search results). The authors also expanded their data collection to undertake more in-depth searching of the grey literature and conducted hand searches of key journals to provide a more comprehensive analysis and evidence base for policy development. The search was restricted to English-language studies in journals from countries that are part of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and selected articles generally came from countries with similar healthcare systems, such as Canada and Australia.

Table 1.

Search results

| Database | Studies, n |

|---|---|

| Medline, Embase, and Cochrane (reviews, meta-analyses) | 129 |

| HMIC (reports, policy documents, and grey literature) | 270 |

| Medline, Embase, and Cochrane (journal articles) | 879 |

| PsycINFO | 351 |

| Cinahl | 43 |

| TRIP | 30 |

Cinahl = Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature. HMIC = Health Management Information Consortium. TRIP = Turning Research Into Practice.

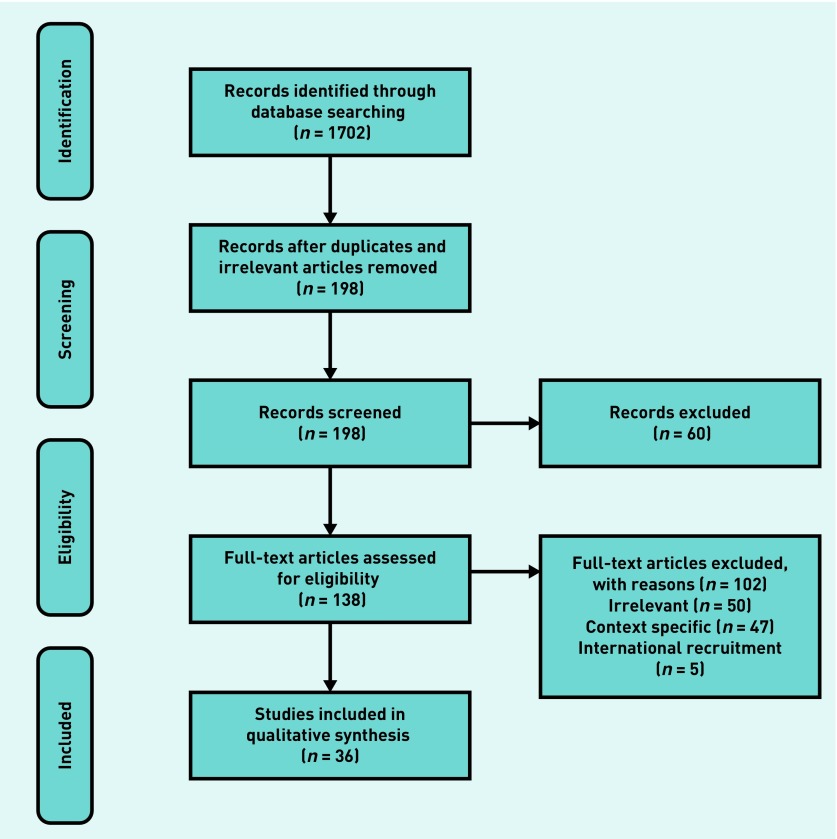

Duplicates were deleted and a basic initial weeding process was undertaken to exclude irrelevant papers. The research team reviewed the titles and abstracts of identified articles to select relevant studies for inclusion in the review. Original research papers and empirical studies (Figure 118) were reviewed, both from the UK and from other countries where relevant.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of identification and inclusion of studies for review. Adapted with permission from the PRISMA statement.18

RESULTS

There was a degree of overlap between studies that examined retention and which also studied recruitment. However, in order to set the evidence on recruitment and retention determinants, these are presented separately.

Recruitment in general practice

Studies that examine specific recruitment strategies for the GP workforce are scarce.19 This review suggests that most studies on primary care physician recruitment (for example, GPs and family doctors) have predominantly focused on remote rural locations. However, the authors identified a number of studies that examined the determinants influencing recruitment that would be relevant to general practice. These can be characterised in terms of how they relate to the individual, institutional, and professional contexts of recruitment.

In a study of career choices, Shadbolt and Bunker20 presented determinants that are mainly intrinsic to the individual. These intrinsic factors include physicians’ self-awareness of their skills, and the factors associated with career orientations or choices. These are influenced by demographic variables, lifestyle orientation, and the opportunities for learning and educational development,20–23 suggesting that medical graduates primarily look for a career that is stimulating and interesting. One study found that medical students were more attracted towards biomedical or technical forms of medical practice, as opposed to a more holistic form of medicine.21

Medical students exposure to, and experience of, general practice has an important effect on preferences for a career in general practice. The authors identified a number of studies that highlighted the important influence on recruitment of the workplace experience, stressing the need for a positive experience from interactions with members of the profession, the length of time spent in general practice, the quality of the practice, and the dedication of the generalists’ faculty.19–21,24–29 In particular, positive experiences were linked to an increased likelihood to choose general practice; especially when the experience occurred at the pre-clinical or early stage.25,29

Similarly, Campos-Outcalt et al30 found that the best strategies to enlarge the proportion of medical students choosing generalist careers included reform of the medical school curricula with emphasis on generalist training, increasing the size of generalist faculties, and ensuring there is clinical training in family practice training. There is some evidence to show that implementing effective medical school curricula in primary care and establishing primary care honours tracks, developing or expanding primary care fast-track programmes, and developing curricula proposing portfolio careers and profile of new skills20,28,30,31 influences students’ career choices. Currently, medical training delivered in general practice, and the proportion of the medical school budget made available for its teaching, is lower than the time dedicated to, and resources available for, teaching related to secondary care.2

Two studies focused on the effect of the modification of admission criteria to identify potential students who are more likely to choose primary care specialisation as part of student selection. They proposed that assessing the community of origin and previous experience of, or interest in, people and social concerns, and discussing future specialty choices be integrated into the admission process.32,33 Providing financial support to students choosing poorly recruiting areas of practice has been shown to have a negative impact on retaining those students when in practice.34 However, increases in student debt from higher tuition fees may make such schemes more attractive, although further research is required.20,27

Factors influencing recruitment are related to the clinical content, perceived lifestyle, and work context. The clinical content of the role is one of the most important factors influencing career choices.23 Given this dominance, the negative view of general practice held by medical students — that it is less intellectually stimulating — may explain the lack of interest in this career choice.20,23 However, Chellappah and Garnham21 concluded that students at the end of their training have a positive image of general practice, suggesting that students’ views change during medical training, but choices regarding eventual specialty are taken earlier in medical school, before these more positive views are formed.

Work climate and work context, such as the support from colleagues, autonomy, flexibility and independence, proximity with patients, the continuity of care, and health promotion, are also key factors affecting recruitment.20,21,23,35,36 Compatibility with family life and the medical breadth of the discipline also positively influence choosing general practice.36

Shadbolt and Bunker20 have suggested that more attention should be paid to the fit between skills and attributes with intellectual content and demands of primary medical care, by emphasising the lifestyle issues (flexibility or work–life balance), social orientation (patient focused or community based), and the opportunity to gain significant and varied clinical experience in the primary care setting.

Retention of GPs

Few studies explicitly examined how to retain primary care physicians in practice. In the UK, the numbers of GPs registering to work abroad has significantly increased in the past 3 years, and GPs’ intention to quit practice has been increasing: from 8.9% in 2012 to 13.1% in 2015 among GPs <50 years old, and from 54.1% in 2012 to 60.9% in 2015 among GPs aged ≥50 years.14 Retention can be influenced by a variety of intrinsic and extrinsic factors, including remuneration, income and salary retention schemes, job satisfaction, and career pathway and portfolio.15,16,37

Although remuneration and retention schemes, such as increases in salary or lump sum payments, are used by the government to retain doctors, there is little evidence of the positive and effective impact of these schemes. Low pay might be a source of dissatisfaction with the job,27 but the evidence suggests that increases in income would not compensate for other sources of job dissatisfaction, such as workload.37

Job satisfaction and job dissatisfaction are significant predictors of GP retention and turnover,38,39 reflecting the findings of research in the wider management and organisational behaviour literature.40,41 Job satisfaction varies from time to time within an individual’s career stages. Therefore, it is important to understand both the determinants influencing job satisfaction and dissatisfaction, and also the factors that increase strain in the workplace and in general practice. Job satisfaction and dissatisfaction are related to three factors: job stressors (for example, workload), job characteristics and attributes (for example, job autonomy), and other conditions (for example, practice geographical location).

Job dissatisfaction is most influenced by work-related variables. In particular, these include increased workload intensity and volume to meet the requirements of external agencies, having insufficient time to do the job justice, increased administration and bureaucracy, increased demand and expectation from patients, increasing work complexity, lack of support from colleagues, lack of professional recognition, and long working hours.14,39,40,42 More recently, adverse publicity from the media, changes imposed from local primary care organisations, and insufficient resources within the practice have all increased job dissatisfaction.13 There is evidence to show that increased work stress and work intensity leads GPs under ‘high strain’ to report higher levels of anxiety, depression, and dissatisfaction than GPs under ‘low strain’, and that the health impacts of stress continued outside of work, which in turn could increase job dissatisfaction and intention to quit the profession.43,44

Job satisfaction is also influenced by expectations about future events.45 If doctors perceive that their workload will not reduce, and that demands will always increase, it is likely that they will feel more overwhelmed and less satisfied with their job, and thus more likely to quit. Therefore, feeling more stressed, disillusioned, and overwhelmed amplifies the negative portrayal of GPs in the media and by government, further negatively affecting GPs’ spirit and professional identity.46

There is some evidence that job autonomy, the variety of work, the feeling of doing an important job, social support, and a good practice environment positively affect job satisfaction.14,39,47 However, GP surveys suggest that a number of these attributes have changed between 2012 and 2015; such as the autonomy in deciding how to do their job and what work to do, the variety of work, and flexibility of working.14

Changes to general practice over the last 10–15 years have been substantial, and job dissatisfaction could be a result of the changing roles necessitated by professional and organisational changes.38,47 However, job satisfaction is also influenced by a number of other factors, such as the local practice context, work–life flexibility, personal development, and the emotional impact of working as a GP.42,47 Wordsworth et al 48 suggested that enhancing the patient care aspects of a GP’s work is more likely to act as a key for retention, and that lack of consultation on changes can lead to dissatisfaction.49 Flexibility and part-time working have always been seen as factors that make general practice a more attractive working environment, although this is increasingly seen to be less relevant.48,50–52

Mentorship schemes and opportunities to develop portfolio careers would be welcome at every stage of a GP’s career, not just for senior doctors or towards the end of working lives.20,26,29 Two papers suggest that a wider choice of long-term career paths, such as subspecialisation and portfolio careers (for example, dermatology or paediatrics), is important for both the recruitment and retention of GPs. It is also suggested that an increase in satisfaction of intellectual and altruistic needs, and functional flexibility within their practice, could improve satisfaction and fulfilment, and consequently GPs’ retention.20,29 Providing learning and development activities, such as developing management skills, could support GP recruitment and retention, providing an opportunity for students to map out development pathways and provide variety within a physician’s role.

DISCUSSION

Summary

Three elements are relevant to GP recruitment: individual, institutional, and professional factors. In addition, providing students with appropriate opportunities for contact with, and positive exposure to, general practice and GPs is critical, as well as widening the opportunities for students and GPs so that junior doctors’ specialisation choices can reflect more individual student characteristics. The main determinants of retention are job satisfaction (versus dissatisfaction), the influence of job stress, job attributes and characteristics, and other conditions, such as the geographical location of the practice. All seem related to career pathways and portfolio.

Based on this review of the evidence, the authors would support strategies that provide long-term investment in general practice. Current proposals to increase the proportion of NHS funding in primary care are therefore welcome. The evidence suggests that providing the right environment and opportunity for GPs to focus on supporting patients as medical professionals is crucial, requiring strategies that reduce workload while retaining the core attributes of general practice. However, strategies should also include opportunities for GPs to develop wider interests and skills, and should take into consideration both recruitment and retention simultaneously. From this review, there appear to be three key lessons that should underpin national and local policies:

review the curricula in medical schools and emphasise the importance of exposure to general practice;

job satisfaction is the main predictor of retention and is influenced by workload stress and future anticipation, and thus strategies that reduce workload are required; and

financial inducements (golden handcuffs) are not necessarily effective.

Strengths and limitations

Overall, the published evidence in relation to GP recruitment and retention is limited and mostly focuses on attracting GPs to rural areas — particularly in Australia. The review shows an overlap in the determinants of recruitment and retention.47 Despite this, the evidence suggests that there are some potential factors that may usefully support the development of specific strategies for supporting the recruitment and retention of GPs. These are summarised in Table 2 and Appendix 2. Although most strategies proposed by the 10-point plan from the document Building the Workforce — the New Deal for General Practice and the General Practice Forward View are not based on strong evidence, some determinants might help with the GP workforce crisis.15,16

Table 2.

Summary of evidence to support GP recruitment and retention, using a framework adapted from the 10-point plan from Building the Workforce — the New Deal for General Practice document.15

| 10-point plan | Evidence from GP literature | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Recruitment | 1. Promoting general practice | No clear evidence |

|

| 2. Improving the breadth of training (for candidates seeking to work in geographies where it is hard to recruit trainees) | Some evidence both for candidates seeking to work in geographies where it is hard to recruit trainees, and for GP trainees seeking to work everywhere |

Exposure to general practice:

Curricula modifications:

Recruitment/admission:

|

|

| 3. Training hubs | Some evidence in the rural training and context literature |

Rural training, rural context literature:

|

|

| 4. Targeted support | Some evidence in the rural training and context literature, but no clear evidence in general practice |

|

|

| Other |

Determinant factors in specialisation choice:

|

||

| Retention | 5. Investment in retainer schemes | No clear evidence |

Widening the scope of remuneration and contract conditions:

|

| 6. Improving the training capacity in general practice | No clear evidence | Subspecialisation and portfolio careers where doctors might gain skills in a range of specialties and practices, some or all of them at any one time | |

| 7. Incentives to remain in practice | No clear evidence | ||

| 8. New ways of working | No clear evidence |

Varying time commitment across the working day and week:

|

|

| Other | Evidence |

Increased satisfaction (factors):

|

Implications for research and practice

Newton et al found that retirement at 60 years old was a goal for both happy GPs — in order to do other things or because they feel they have ‘done their bit’ — and those GPs who no longer had the resilience to cope with work stress.50 In their study, Roos et al showed that, although 83.7% of GP trainees and newly qualified GPs would choose to be a physician again, only 78.4% would choose general practice as a specialisation.36 One clear message from the literature is that expectations about the future — whether as a new GP or because of future developments in general practice — affect both recruitment and retention.45,53

One area not fully explored in the literature identified for this review was the recruitment policy of medical schools, given that that there are career choice determinants influencing the recruitment of GPs in medical school. It would be interesting in the future to explore the role of health policy on the specific recruitment policy of medical schools, and this is likely to be influenced by the findings of the joint HEE and Medical Schools Council review chaired by Professor Val Wass.54,55 The General Practice Forward View has suggested recruitment at the international level. International recruitment was outside the scope of this review. A post-hoc analysis shows a lack of evidence of the long-term beneficial effects of such recruitment strategy.56–60 Short-term policies, such as international recruitment, financial bonuses, and other incentive packages, may respond to immediate needs, but are not long-term solutions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms Anna Peckham, consultant librarian, for her assistance in the literature search.

Appendix 1. Search terms

| Key terms | Combined with: |

|---|---|

| General practitioner | Recruitment |

| GPs | Recruitment strategya |

| General practice | Personnel recruitment |

| Family practitionera | Employment |

| Family practice | Career choice |

| Family physiciana | Personnel turnover |

| Family doctora | Motivation |

| Primary care physiciana | Retention |

| Primary care doctora | GP retention |

| Primary care practitionera | Retirement Early retirement |

Truncation.

Appendix 2. Characteristics of included reviews on determinant of recruitment and retention of GPs

| Authors | Year | Countries | Article type | Topic | Method | Relevance | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buchbinder SB et al 46 | 2001 | US | Cohort study | Primary care physician, job satisfaction and turnover | Questionnaire survey | Weak: cohort from the US and data from 1987 to 1991 | Good |

| Buciuniene I et al 42 | 2005 | Lithuania | Original research | Healthcare reform and job satisfaction | Self-administrated anonymous questionnaires | Weak: GPs and policy from Lithuania | Average/weak: cross-sectional and statistical analyses simplistic (no regression, only correlations) |

| Bustinza R et al 34 | 2009 | Canada | Cohort study | Training programme, GP retention in rural area | Used of secondary data and questionnaires | Average: Canada has a similar primary care context but the study was in a rural context | Good |

| Campos-Outcalt D et al 30 | 1995 | US | Review/quality assessment | Curricula, role models, research support, career choice | Literature search: Medline, PsycINFO, Current Contents, Expanded Academic Index | Average, the article presents three elements influencing career choice, but the article is quite old | Average: the methods are very detailed. Very few articles were included in the results section due to the lack of quality articles fitting their 70 criteria |

| CfWI51 | 2014 | UK | Review/report | GP workforce | N/A | High | Good: because it gives an overview of the GP workforce in the UK |

| Chellappah M, Garnham L21 | 2014 | UK | Original research | Medical student attitude towards general practice | Questionnaire design | High | Weak: not generalisable (specific to one college). Measurement scale not used |

| Crampton PES et al 22 | 2013 | Australia, US, Canada, NZ, South Africa, Japan | Systematic literature review | Undergraduate clinical placements, underserved areas | Database searches, inclusion and exclusion criteria, data extraction, and so on | Weak | High |

| Dale J et al 43 | 2015 | UK (West Midlands) | Cross-sectional study | Retention of GPs | Online questionnaire with free-text section | High | Good: because it questioned the proposition that general practice is in crisis |

| Dayan M et al 37 | 2014 | UK | Report | GP workforce crisis | N/A | Good | Average |

| Doran N et al 47 | 2016 | UK | Mixed-methods research | Why GPs leave the NHS | Online questionnaire with qualitative interviews | High | Good |

| Evans J et al 52 | 2000 | UK | Cohort study | Medical graduates and flexible/part-time working in medicine | Survey with free-text comment. Reported mainly the qualitative data | Weak: medical graduate in general not only future GPs, also the data come from 1977, 1988, and 1993 | Average: used mainly qualitative data coming from the free-text comment. The percentage of comment on flexible and part time is less than 9% for the three cohorts |

| Feeley TH53 | 2003 | N/A | Narrative literature review | Retention in rural primary care physicians | N/A | Weak | Weak |

| Geyman JP et al33 | 2000 | US | Study | Educating GPs for rural practice | Comprehensive literature search: Medline, Health STAR databases | Weak, but the recommendations are interesting | Average/weak: little analysis, only looked at programmes |

| Gibson J et al14 | 2015 | UK | Report, survey | GP work/life survey | Questionnaire | Good | Average: it is a report. |

| Groenewegen PP et al44 | 1991 | US | Review of the literature | GP, effective workload, job satisfaction | N/A | Good | Average: no method but definition and theorisation is interesting |

| Halaas GW et al 24 | 2008 | US | Study | Recruitment and retention of rural physicians | Analysed data from a recruitment programme | Good, but the results are linked to the rural context | Average: no hypothesis, nor hypothesis testing, but 37-year trend studied |

| Harding A et al 2 | 2015 | UK | Cross-sectional study | Teaching and general practice | Review of past national survey and questionnaire survey | Good | Good |

| Hemphill E et al 61 | 2007 | Australia | Mixed design | GP rural recruitment | Three sources of data collection: GP survey, data collected from a convenient sample of students, and interviews with recruiting agencies | Weak | Average |

| Humphreys J et al 49 | 2001 | Australia | Critical review | Rural medical workforce retention | Australian and international database: ATSI Health, Consumer service, AusportMed, Family & Society, and so on | Good | Average: issues with method inclusion/exclusion criteria |

| Illing J et al 25 | 2003 | UK | Review of evidence | Learning in practice (preregistration house officers) and general practice | Literature search: Embrase, Medline, ERIC, FirstSearch, PsycINFO, www.timelit.org.uk, www.educationgp.com | Good | Average: methods inclusion and exclusion criteria not presented |

| Landry M et al 26 | 2011 | Canada | Original study | Recruitment and retention of doctors and local training (rural) | Short survey | Good but the results are linked to the rural context | Good: methods well presented, the analyses are adequate |

| Lee DM, Nichols T 27 | 2014 | US, Canada | Case study, review | Physician recruitment and retention, rural and underserved areas | Literature review | Weak: but suggestions for different factors influencing recruitment and retention | Average: the review method is described but the case study choice is not explained |

| Newton J et al 50 | 2004 | UK (Northern Deanery) | Original study | Job dissatisfaction and early retirement | Qualitative study: interviews, using a purposefully drawn sample from seven sub-groups of responders | Good | Average: small number of interviewees |

| O’Connor DB et al 45 | 2000 | UK (Liverpool) | Preliminary study | Job strain and blood pressure in general practice | Questionnaire and ambulatory blood pressure procedure | High: relationship between job strain and blood pressure | Good |

| Petchey R et al 23 | 1997 | UK | Original study | Junior doctors’ perceptions of general practice as a career | Qualitative study: interviews, using an heterogeneous sample | High | Weak: little theoretical. development |

| Roos M et al 36 | 2014 | Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Italy, Norway, Portugal, UK | Original cross-sectional study | Motivation for career choice and job satisfaction: GP trainees and newly qualified GPs | Questionnaire/survey | High | Good |

| Rosenthal TC 32 | 2000 | US | Review | Rural training tracts | N/A | Weak: but interesting insight | Weak |

| Schwartz MD et al 28 | 2005 | US | Reflection | Student interest in generalist career | N/A | High | Weak: recommendations without original study, nor based on evidence from various articles |

| Shadbolt N, Bunker J 20 | 2009 | Australia | Review | Career choice determinants | N/A | High | Weak: no method |

| Sibbald B et al 39 | 2003 | England | National survey | Job satisfaction and retirement | Survey | High | Good |

| Stapleton G et al 62 | 2014 | English-speaking countries | Review, ethical criteria | Primary care physicians | Database: Web of Knowledge | Weak | Average: presentation of methods |

| Van Ham I et al 40 | 2006 | UK, US, Australia | Systematic review | GPs and job satisfaction | Two strategies: database and snowball methods | High | High |

| Verma P et al 19 | 2016 | UK, US, Canada, Australia, Japan, NZ, Norway, Chile | Systematic review | Strategies to recruit and retain | Literature search: Medline, Embase, and Central, 1974–2013 | High | High |

| Williamson JW et al 31 | 1993 | US | Comparative studies | Primary care, health systems change | N/A | Weak | Weak: no method |

| Wordsworth S et al 48 | 2004 | UK | Original study | Preferences for general practice jobs | Discrete-choice experiment | Good | Good |

| Young R, Leese B 29 | 1999 | UK | Discussion paper/review | Recruitment and retention of GPs in the UK | Literature search: Medline, BIDS-EMBASE, IBSS, HELMIS, survey of articles in recent issues of relevant professional journals | High | Average: little theoretical development and evidence |

ATSI = Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander. CfWI = Centre for Workforce Improvement. ERIC = Education Resources Information Centre. HELMIS = Health Management Information Service. IBSS: = International Bibliography of the Social Sciences.

Funding

The review was commissioned by the Department of Health from the Policy Research Unit in Commissioning and the Healthcare System (PRUComm). The views expressed are those of the researchers and not necessarily those of the Department of Health. The funding reference number is PHSRHF58.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Gillam S, Siriwardena AN. Evidence-based healthcare and quality improvement. Qual Prim Care. 2014;22(3):125–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harding A, Rosenthal J, Al-Seaidy M, et al. Provision of medical student teaching in UK general practices: a cross-sectional questionnaire study. Br J Gen Pract. 2015. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp15X685321'. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Hobbs FD, Bankhead C, Mukhtar T, et al. Clinical workload in UK primary care: a retrospective analysis of 100 million consultations in England, 2007–14. Lancet. 2016;387(10035):2323–2330. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00620-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones D. GP recruitment and retention. Br J Gen Pract. 2015. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp15X684721'. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.NHS The Information Centre for health and social care. NHS workforce: summary of staff in the NHS: results from September 2012 census. 2013. http://content.digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB10392/nhs-staf-2002-2012-over-rep.pdf (accessed 24 Feb 2017).

- 6.Svirko E, Goldacre MJ, Lambert T. Career choices of the United Kingdom medical graduates of 2005, 2008 and 2009: questionnaire surveys. Med Teach. 2013;35(5):365–375. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.746450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas R. HEE misses GP training target despite record recruitment. Health Serv J. 2016. Oct 20, https://www.hsj.co.uk/sectors/primary-care/hee-misses-gp-training-target-despite-record-recruitment/7011651.article (accessed 24 Feb 2017).

- 8.Millet D. Health education chiefs identify 5,000 GP recruitment target as ‘greatest risk’. GP. 2016. Jul 21, http://www.gponline.com/health-education-chiefs-identify-5000-gp-recruitment-target-greatest-risk/article/1403071 (accessed 13 Feb 2017).

- 9.Department of Health . Primary care delivering the future. London: DH; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health . The new NHS: modern, dependable. London: DH; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Health . The NHS plan: a plan for investment, a plan for reform. London: DH; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Department of Health . Our health, our care, our say: a new direction for community services. London: DH; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis J. 800 GPs applying for permit to work abroad every year. Pulse. 2015. Aug 6, http://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/your-practice/regulation/800-gps-applying-for-permit-to-work-abroad-every-year/20010699.article (accessed 13 Feb 2017).

- 14.Gibson J, Checkland K, Coleman A, et al. Eighth national GP worklife survey. Manchester: Policy Research Unit in Commissioning and the Healthcare System; 2015. http://www.population-health.manchester.ac.uk/healtheconomics/research/Reports/EighthNationalGPWorklifeSurveyreport/EighthNationalGPWorklifeSurveyreport.pdf (accessed 15 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Royal College of General Practitioners. British Medical Association. NHS England. Health Education England Building the workforce — the new deal for general practice. 2015. https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2015/01/building-the-workforce-new-deal-gp.pdf (accessed 13 Feb 2017).

- 16.NHS England General practice forward view. 2016. https://www.england.nhs.uk/gp/gpfv/ (accessed 15 Feb 2017).

- 17.Peckham S, Marchand C, Peckham A. General practitioner recruitment and retention: an evidence synthesis. Final report. Canterbury: Policy Research Unit in Commisioning and the Healthcare System; 2016. https://kar.kent.ac.uk/58788/1/PRUComm%20General%20practitioner%20recruitment%20and%20retention%20review%20Final%20Report.pdf (accessed 13 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, for the PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verma P, Ford JA, Stuart A, et al. A systematic review of strategies to recruit and retain primary care doctors. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:126. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1370-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shadbolt N, Bunker J. Choosing general practice: a review of career choice determinants. Aust Fam Physician. 2009;38(1–2):53–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chellappah M, Garnham L. Medical students’ attitudes towards general practice and factors affecting career choice: a questionnaire study. London J Prim Care. 2014;6(6):117–123. doi: 10.1080/17571472.2014.11494362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crampton PES, McLachlan JC, Illing JC. A systematic literature review of undergraduate clinical placements in underserved areas. Med Educ. 2013;47(10):969–978. doi: 10.1111/medu.12215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petchey R, Williams J, Baker M. ‘Ending up a GP’: a qualitative study of junior doctors’ perceptions of general practice as a career. Fam Pract. 1997;14(3):194–198. doi: 10.1093/fampra/14.3.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halaas GW, Zink T, Finstad D, et al. Recruitment and retention of rural physicians: outcomes from the rural physician associate program of Minnesota. J Rural Health. 2008;24(4):345–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2008.00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Illing J, Van Zwanenberg T, Cunningham WF, et al. Preregistration house officers in general practice: review of evidence. BMJ. 2003;326(7397):1019–1022. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7397.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landry M, Schofield A, Bordage R, Belanger M. Improving the recruitment and retention of doctors by training medical students locally. Med Educ. 2011;45:1121–1129. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee DM, Nichols T. Physician recruitment and retention in rural and underserved areas. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2014;27(7):642–652. doi: 10.1108/ijhcqa-04-2014-0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwartz MD, Basco WT, Jr, Grey MR, et al. Rekindling student interest in generalist careers. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(8):715–724. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-8-200504190-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Young R, Leese B. Recruitment and retention of general practitioners in the UK: what are the problems and solutions? Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49(447):829–833. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campos-Outcalt D, Senf J, Watkins AJ, Bastacky S. The effects of medical school curricula, faculty role models, and biomedical research support on choice of generalist physician careers: a review and quality assessment of the literature. Acad Med. 1995;70(7):611–619. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199507000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williamson JW, Walters K, Cordes DL. Primary care, quality improvement, and health systems change. Am J Med Qual. 1993;8(2):37–44. doi: 10.1177/0885713X9300800203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenthal TC. Outcomes of rural training tracks: a review. J Rural Health. 2000;16(3):213–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2000.tb00459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geyman JP, Hart LG, Norris TE, et al. Educating generalist physicians for rural practice: how are we doing? J Rural Health. 2000;16(1):56–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2000.tb00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bustinza R, Gagnon S, Burigusa G. [The decentralized training programme and the retention of general practitioners in Quebec’s Lower St Lawrence Region]. [Article in French] Can Fam Physician. 2009;55(9):e29–e34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hemphill E, Kulik CT. Segmenting a general practitioner market to improve recruitment outcomes. Aust Health Rev. 2011;35(2):117–123. doi: 10.1071/AH09802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roos M, Watson J, Wensing M, Peters-Klimm F. Motivation for career choice and job satisfaction of GP trainees and newly qualified GPs across Europe: a seven countries cross-sectional survey. Educ Prim Care. 2014;25(4):202–210. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2014.11494278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dayan M, Arora S, Rosen R, Curry N. Is general practice in crisis? London: Nuffield Trust; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sibbald B, Enzer I, Cooper C, et al. GP job satisfaction in 1987, 1990 and 1998: lessons for the future? Fam Pract. 2000;17(5):364–371. doi: 10.1093/fampra/17.5.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sibbald B, Bojke C, Gravelle H. National survey of job satisfaction and retirement intentions among general practitioners in England. BMJ. 2003;326(7379):22. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7379.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Ham I, Verhoeven AAH, Groenier KH, et al. Job satisfaction among general practitioners: a systematic literature review. Eur J Gen Pract. 2006;12(4):174–180. doi: 10.1080/13814780600994376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Griffeth RW, Hom PW, Gaertner S. A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. J Manag. 2000;26(3):463–488. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buciuniene I, Blazeviciene A, Bliudziute E. Health care reform and job satisfaction of primary health care physicians in Lithuania. BMC Fam Pract. 2005;6(1):10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dale J, Potter R, Owen K, et al. Retaining the general practitioner workforce in England: what matters to GPs? A cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:140. doi: 10.1186/s12875-015-0363-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Groenewegen PP, Hutten JB. Workload and job satisfaction among general practitioners: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(10):1111–1119. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90087-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Connor DB, O’Connor R, White B, Bundred P. Job strain and ambulatory blood pressure in British general practitioners: a preliminary study. Psychol Health Med. 2000;5(3):241–250. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buchbinder SB, Wilson M, Melick CF, Powe NR. Primary care physician job satisfaction and turnover. Am J Manag Care. 2001;7(7):701–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Doran N, Fox F, Rodham K, et al. Lost to the NHS: a mixed methods study of why GPs leave practice early in England. Br J Gen Pract. 2016. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp16X683425'. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Wordsworth S, Skåtun D, Scott A, French F. Preferences for general practice jobs: a survey of principals and sessional GPs. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(507):740–746. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Humphreys J, Jones J, Jones M, et al. A critical review of rural medical workforce retention in Australia. Aust Health Rev. 2001;24(4):91–102. doi: 10.1071/ah010091a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Newton J, Luce A, Van Zwanenberg T, Firth-Cozens J. Job dissatisfaction and early retirement: a qualitative study of general practitioners in the Northern Deanery. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2004;5(1):68–76. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Centre for Workforce Intelligence . In-depth review of the general practitioner workforce. London: CfWI; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Evans J, Goldacre MJ, Lambert TW. Views of UK medical graduates about flexible and part-time working in medicine: a qualitative study. Med Educ. 2000;34(5):355–362. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Feeley TH. Using the theory of reasoned action to model retention in rural primary care physicians. J Rural Health. 2003;19(3):245–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2003.tb00570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matthews-King A. Education bosses launch landmark review into GP attitude in medical schools. Pulse. 2016. Mar 2, http://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/your-practice/practice-topics/education/education-bosses-launch-landmark-review-into-gp-attitude-in-medical-schools/20031274.fullarticle (accessed 13 Feb 2017).

- 55.Wass V, Gregory S, Petty-Saphon K. By choice — not by chance: supporting medical students towards future careers in general practice. London: Medical Schools Council and Health Education England; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bradby H. International medical migration: a critical conceptual review of the global movements of doctors and nurses. Health (London) 2014;18(6):580–596. doi: 10.1177/1363459314524803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Buchan J, Dovlo D. International recruitment of health workers to the UK: a report for DFID: final report. London: DFID HSRC; 2004. Department for International Development Health Systems Resource Centre. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Legido-Quigley H, Saliba V, McKee M. Exploring the experiences of EU qualified doctors working in the United Kingdom: a qualitative study. Health Policy. 2015;119(4):494–502. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lozano M, Meardi G, Martín-Artiles A. International recruitment of health workers. British Lessons for Europe? Emerging concerns and future research recommendations. Int J Health Serv. 2015;45(2):306–319. doi: 10.1177/0020731414568510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Young R, Noble J, Mahon A, et al. Evaluation of international recruitment of health professionals in England. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2010;15(4):195–203. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2010.009068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hemphill E, Dunn S, Barich H, Infante R. Recruitment and retention of rural general practitioners: a marketing approach reveals new possibilities. Aust J Rural Health. 2007;15(6):360–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2007.00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stapleton G, Schroder-Back P, Brand H, Townend D. Health inequalities and regional specific scarcity in primary care physicians: ethical issues and criteria. Int J Public Health. 2014;59(3):449–455. doi: 10.1007/s00038-013-0497-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]