RETHINKING THE HOW AND WHAT OF HEALTHCARE DELIVERY

‘If primary care fails, the NHS fails.’1

Faced with an unprecedented mismatch between presented health needs and resources available, we must rethink both how we deliver healthcare and what care we deliver. Work has already started on the ‘how’: notably with efforts to strengthen access and integration — improved coordination of the comprehensive care needed to meet a diverse range of needs.2 It is defining ‘what’ to deliver that is proving more challenging. To address emerging problems of over- and under-treatment associated with the undue specialisation of healthcare,3 we need to strengthen delivery of generalist medical care.4 This means that we need to bolster the capacity to decide if and when medical intervention is the right approach for this individual (whole person) in their lived context.5 We need to put the intellectual interpretive expertise6 of the medical generalist back at the core of our primary healthcare systems.

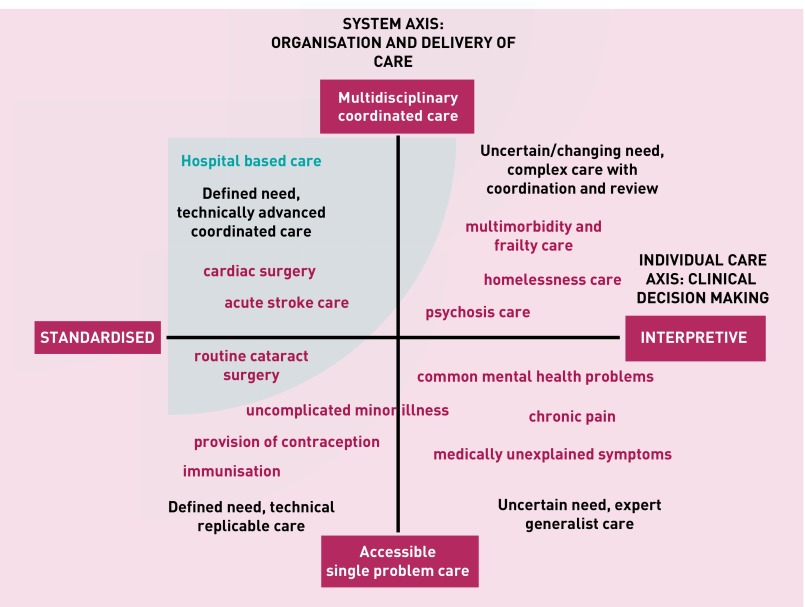

Our ‘United Model of Generalism’ (Figure 1) recognises the important contribution of both ‘Integrated’ and ‘Interpretive care’ in the delivery of whole person generalist medical care. Here, we describe our framework for primary care redesign and discuss the implications for subsequent actions.

Figure 1.

United Model of Generalism.

A UNITED MODEL OF PRIMARY CARE

The ‘Systems Axis’ (on the Y axis) describes a continuum from single problem accessible care through to integrated coordinated care bringing different skills and teams together.

The ‘Individual Care Axis’ (on the X axis) recognises a continuum from standardised, replicable and often evidence informed, to highly-individualised interpretative care. This axis recognises that standardised disease-focused (guideline) medical care, even done well, can have a burdensome effect on individuals.3 Burden comes in many forms; whether as over-investigation and over-treatment, or as a failure to adequately address illness experiences that disrupt daily living (a failure of person-centred care). The two models at each end of the axis represent distinct forms of clinical reasoning that ask different questions and are underpinned by different epistemological approaches.6 In reality, primary care clinicians are often required to move along the continuum in response to particular patient needs.

We thus describe four quadrants with distinct categories of care provision (Figure 1). ‘Single problem/standardised care’ delivers low intensity accessible care at volume, mainly but not only in primary care; and increasingly achieved through technology-supported self-care (for example, blood pressure monitoring, contraception advice) and deployment of less highly-qualified staff (for example, fractures, minor illness). ‘Integrated/standardised care’ sees well-coordinated teams providing access to, and delivery of, condition-specific treatment whether acute management of myocardial infarction or surgical replacement of joints or valves. In both cases, interpretive skills are a lower priority.

Some patients, for example those with mild to moderate mental health needs or medically unexplained chronic pain need ready access to professionals skilled in interpretive practice. Professionals who are able to integrate biomedical, psychosocial, patient and professional accounts of illness in order to help patients make sense of, and so take an active part in managing, their own health problems.6 Patients in this ‘Accessible/Interpretive’ quadrant may benefit from signposting to services outside of medical care, but generally don’t need high levels of integrated care across medical teams. Some need ongoing continuity of care, while for others a single contact can provide timely treatment, reassurance or diversion from unnecessary investigation or medicine.

Patients with chronic complex care needs, especially those with diminished capacity to manage daily living (for example, multimorbidity, severe mental illness, homelessness), need both coordinated/ integrated and interpretive care. Medicine in this quadrant requires expert practitioners able to make decisions with patients, and work across teams taking account of shifting needs in the social, emotional, and biological domains. This approach should help prioritise needs and support choices to do less medicine, so avoiding the iatrogenic harm arising from a failure to tailor care to the individual-in-context.7,8

REVIEWING CURRENT PRACTICE

Applying the United Model of Generalism to current practice highlights examples of how current services do not match resources and skills to patient need.

Demographic changes resulting in more patients living longer with frailty sees a shift of patients into the top-left quadrant. While more resources are needed to support this growing population, some in this group need less medicine not more. 8 We need strengthened capacity for Interpretive Care within emerging frailty initiatives and the so-called ‘new models of care’.9 GPs with enhanced skills in expert generalist practice6 provide a key resource to take on this role if time can be freed up from work in the bottom two quadrants.

WHAT NEEDS TO CHANGE

We need to better understand which quadrant of care individual patients best sit within. We still predominantly define healthcare need based on disease status and/or (unplanned) health service use.10 We now need new tools to help identify patients in need of individually tailored medical care3 in a timely manner. Frailty initiatives are a useful starting point, but will miss many people needing this alternative approach.7 A better understanding of the epidemiology of populations in each of the quadrants is needed to support an effective shift of resources from hospital to community-based care.

Health services monitoring and performance management systems can improve delivery of disease-focused care, but act as a barrier to interpretive care.11 We have previously described the changes needed to enhance professional capacity for Interpretive Practice, including updates to the way we train, supervise, and support primary care health professionals.6,11 We also need appropriate monitoring processes for each of the different quadrants.

Perhaps most challenging will be the public debate required to win hearts and minds over to medicine that is less hospital-based and less technological. It will require-brave and eloquent practitioners and politicians to engage public understanding of the need for change.

CONCLUSION

Lewis described Integrated care and Interpretive Practice as the ‘two faces’ of generalism. He states that:

‘… generalism grounded in person-centred care [Interpretive Practice] may appear quaint and unambitious … But it is relevant to the widespread failures of the here and now, and whether and how it takes hold matters a great deal.’12

The United Generalism Model is a device to help people think differently about both dimensions of care, and for the rationale of shifting resources from the top-left quadrant to the other three quadrants. Greater volume of technical delivery of integrated care alone won’t address today’s key challenges of rising volume and demands. Use of interpretive skills is an important mechanism for achieving more with less medicine; placing patient and practitioner — rather than protocols and system rules — at the centre of clinical decisions.

Such skills are critical for achieving the dual imperatives of managing both the non-specific presentations and ongoing proactive care of individuals with complex needs. By considering the two faces together, and developing flexible delivery systems that are optimised for the different quadrants, we can ensure that Interpretative Generalism — and so strong person-centred primary care — is realised at scale.

Funding

Richard Byng has funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) for the South West Peninsula.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roland M, Everington S. Tackling the crisis in general practice. BMJ. 2016;352:i942. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaw S, Rosen R, Rumbold B. What is integrated care? Research report. 2011. http://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/files/2017-01/what-is-integrated-care-report-web-final.pdf (accessed 26 May 2017)

- 3.Tinetti ME, Fried T. The end of the disease era. Am J Med. 2004;116(3):179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NHS England The Five Year Forward View. 2014. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf (accessed 26 May 2017)

- 5.Heath I. Divided we fail. Clin Med. 2011;11(6):576–586. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.11-6-576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reeve J. Interpretive medicine. Supporting generalism in a changing primary care world. 2010. Occas Pap R Coll Gen Pract. 2010;88:i–viii. 1–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reeve J, Cooper L. Rethinking how we understand individual health care needs for people living with long-term conditions: a qualitative study. Health Soc Care Community. 2016;24(1):27–38. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leppin AL, Montori VM, Gionfriddo MR. Minimally Disruptive Medicine: a pragmatically comprehensive model for delivering care to patients with multiple chronic conditions. Healthcare. 2015;3(1):50–63. doi: 10.3390/healthcare3010050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lloyd H, Pearson M, Britten N, et al. Person-Centred Coordinated Care (PCCC). ‘Care that is guided by and organised effectively around the needs and preferences of the individual’. Plymouth University; 2017. http://www.plymouth.ac.uk/research/primarycare/person-centred-coordinated-care (accessed 5 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis G. Next steps for risk stratification in the NHS. NHS England; 2015. http://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/nxt-steps-risk-strat-glewis.pdf (accessed 26 May 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reeve J, Dowrick C, Freeman G, et al. Examining the practice of generalist expertise: a qualitative study identifying constraints and solutions. JRSM Short Rep. 2013;4(12) doi: 10.1177/2042533313510155. 2042533313510155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis S. The two faces of generalism. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2014;19(1):1–2. doi: 10.1177/1355819613511075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]