Abstract

Background

Older people with common mental health problems (CMHPs) are known to have reduced rates of referral to psychological therapy.

Aim

To assess referral rates to the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) services, contact with a therapist, and clinical outcome by age.

Design and setting

Empirical research study using patient episodes of care from South West of England IAPT services.

Method

By analysing 82 513 episodes of care (2010–2011), referral rates and clinical improvement were compared with both total population and estimated prevalence in each age group using IAPT data. Probable recovery of those completing treatment was calculated for each group.

Results

Estimated prevalence of CMHPs peaks in 45–49-year-olds (20.59% of population). The proportions of patients identified with CMHPs being referred peaks at 20–24 years (22.95%) and reduces with increase in age thereafter to 6.00% for 70–74-year-olds. Once referred, the proportion of those attending first treatment increases with age between 20 years (57.34%) and 64 years (76.97%). In addition, the percentage of those having a clinical improvement gradually increases from the age of 18 years (12.94%) to 69 years (20.74%).

Conclusion

Younger adults are more readily referred to IAPT services. However, as a proportion of those referred, probabilities of attending once, attending more than once, and clinical improvement increase with age. It is uncertain whether optimum levels of referral have been reached for young adults. It is important to establish whether changes to service configuration, treatment options, and GP behaviour can increase referrals for middle-aged and older adults.

Keywords: age factors; IAPT; mental health; referral and consultation; therapy, psychological

INTRODUCTION

In 2009, the Royal College of Psychiatrists suggested that the UK currently provides more mental health services for those <65 years of age than it does for older people.1 Barriers to mental health treatment are known to differ by age2 and concerns that discrimination against older adults may lead to reduced access to mental health treatments, including talking therapies, are expressed.3 Data available from the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme, which aimed to equitably improve access, allows exploration of the degree to which inequalities persist across different age groups.

The Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (APMS) provides data on the prevalence of psychiatric disorder (treated and untreated) in the English adult population. ‘Common mental health problems’ (CMHPs) is an umbrella term describing difficulties in low mood and anxiety, and is a descendant of the term ‘common mental disorders’. The APMS describes common mental disorders as conditions comprising different types of depression and anxiety.4 Data from the APMS suggest prevalence of depression reduces with age from middle age onwards,4 a finding supported by others5 but not by Stordal and colleagues,6 who reported a linear increase of depression with increasing age after carefully adjusting for confounders for individuals in Norway. Whatever the truth about prevalence, it is clearly apparent that there is inequity of access. In the 1990s fewer than 3% of adults aged >65 years reported seeing a mental health professional.7 Using data from the APMS (2007), Cooper and colleagues8 found younger adults (16–34 years) to be 80% more likely than older adults (≥75 years) with the same severity of CMHPs to be receiving talking therapy. In contrast, older adults were more likely than younger adults to receive antidepressants or anxiolytics and hypnotics, suggesting that older adults are being prescribed medication rather than talking therapy and vice versa for younger adults here.

Inequities in access to talking therapies across age may be dependent on patient attitudes, practitioner attitudes, and/or system factors. Depressive symptoms are common in older adults, but psychological adjustment to ageing and chronic illness may mean symptoms are not acknowledged or revealed.9 It may be assumed by some healthcare professionals that older adults experience psychological distress as a natural and inevitable consequence of ageing.9,10 Ross and Hardy11 found GP decisions were influenced by patients’ help-seeking behaviours as well as their representations of mental health problems. GPs may believe older adults are less responsive to cognitive behavioural therapy than younger adults.12,13 Patients’ belief that they can ‘manage themselves’ increases with age, making it less likely that they will disclose their mental health problems to a GP, less likely that they will be referred, and less likely that they will accept offered treatment.14,15 It is possible that older adults attribute their symptoms to physical complaints, whereas younger adults have greater awareness of psychological problems.10 Older adults’ inability to express their psychological problems, and their greater self-stigma, reduce the likelihood that they will seek help,10 or be offered appropriate help by healthcare professionals,11 creating further inequities in access to mental health treatment on the basis of age.

How this fits in

Older adults with common mental health problems are known to have reduced rates of referral to psychological therapy. This study assessed referral and access rates to the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) services, as well as clinical outcome, by age. The results show that older adults with common mental health problems are being under-referred but benefit more than younger individuals once they obtain access to the service. This outcome highlights an imbalance in referral rates across age, which should be addressed at the referral stage by healthcare practitioners.

In 2008, the development of new psychological therapy services across England under the IAPT programme improved access to treatments for CMHPs,2 encompassing individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as well as the more prevalent anxiety and depression. By 2011, 142 primary care trusts (PCTs) had an IAPT service and £400 million was being invested up to 2015. Targets for rates of access to psychological therapy included services providing enough therapists to meet the needs of the whole PCT population, with half of those who completed the programme moving to recovery.16 IAPT services include routine collection of session-by-session outcome data for all individuals referred. The IAPT data enable exploration of differences in access to mental health treatments across age, allowing comparisons of referrals, access to the services, and responses to treatment.

Previous audits and monitoring suggest access to talking therapies is greater for younger individuals.8 This study aimed to accurately estimate differences in referral and access rates to the IAPT services and to compare the pathway through treatment across age bands, controlling for predicted prevalence of CMHPs.

METHOD

The overall design of the current study was to derive figures in each age band for total population, estimated prevalence and numbers referred, being seen, and patients who achieved the minimal clinical important difference (MCID) in symptoms; and then to calculate rates using different key denominators. The most recent APMS (2007)4 data were analysed with data collected from IAPT services in 13 primary care trusts (PCTs) from 2010–2011. The dataset was created for a service evaluation project of the IAPT services commissioned by the South West Strategic Health Authority in England.

Population and prevalence data were obtained from the APMS survey, which used a robust stratified, multi-stage probability sample of households, and which assessed and diagnosed psychiatric disorder according to diagnostic criteria where possible. Participants completed the revised Clinical Interview Schedule (CIS- R),17 which measures symptoms linked to the diagnosis of anxiety and depression, and provides an overall score for the presence of CMHPs (indicated by a score of ≥12). The APMS series is the largest, most detailed, and most recent (2007) data (at the time of collection) available for comparison of IAPT services use. The APMS provided numbers on estimated prevalence of CMHPs across sex (which the authors of the current study combined), as well as total population, in each of the 13 PCTs individually. Using this data, the numbers of people in each age group in the South West and the numbers of people in each age group in the South West who were estimated to have CMHPs were totalled, and these were used as denominators to calculate rates and proportions.

Numbers of people referred, obtaining access, and the associated clinical outcomes were derived from the South West IAPT evaluation database, which includes information from the IAPT service providers’ databases relating to 13 South West PCTs. Individuals aged 18–74 years of age were included in the study to reflect data taken from the APMS (which excludes those in care homes). The anonymised referral, access, and outcome data were generated from 82 513 individual episodes of care (76 734 patients). Patients’ demographic information (including age) and details of attendance and health outcomes were recorded at every clinical contact. The latter included the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)18 as a measure of depression, and the Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7)19 questionnaire as a measure of anxiety.

The authors of this study estimated the proportions of the total populations having CMHPs; being referred to IAPT; obtaining access by attending their first session with an IAPT therapist; engaging in treatment by attending at least one further session; and those achieving MCID in both the PHQ-9 and the GAD-7. The proportions were calculated of those estimated to have CMHPs being referred to IAPT; obtaining access by attending their first session with an IAPT therapist; engaging in treatment by attending at least one further session; and those achieving MCID. The proportions were then calculated of referred patients obtaining access; engaging in treatment by attending at least one further session; and those achieving MCID. MCID was also shown as a proportion of those with two or more treatment sessions.

To calculate the MCID patients must have attended two or more (valid) clinical contacts and improvement was measured by comparing final therapy session score with baseline session score on the following outcome measures. The MCID value for PHQ-9 is a reduction of ≥5 points between first and last session, and for GAD-7 it is a reduction of ≥4 points between first and last session.20 The proportion achieving the MCID in both PHQ-9 and GAD-7 by those with more than two therapy sessions in each age group was then calculated.

RESULTS

There were 82 513 treatment episodes recorded across the 13 IAPT services in the South West of England. The number of people in each age group in the study area is shown in Table 1 along with the estimated number of people with CMHPs and the numbers of people referred to IAPT services, attending at least one session with an IAPT practitioner; uptake of treatment by at least one further session; and achieving MCID. The numbers are also expressed as proportions of estimated prevalence, of referrals, and of those seen.

Table 1.

Detail of population and referrals in the South West of England across age including: total population; total number of referrals; referrals as a proportion of population; and estimated prevalence

| Age, years | 18–19 | 20–24 | 25–29 | 30–34 | 35–39 | 40–44 | 45–49 | 50–54 | 55–59 | 60–64 | 65–69 | 70–74 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | (count) | 253 936 | 293 070 | 260 578 | 299 820 | 354 084 | 361 746 | 324 621 | 307 731 | 345 264 | 285 479 | 243 231 | 214 057 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Estimated CMHP cases | (count) | 35 001 | 44 942 | 49 269 | 51 344 | 63 188 | 72 673 | 66 849 | 62 190 | 55 179 | 43 676 | 23 892 | 20 270 |

| (% of population) | 13.78 | 15.33 | 18.91 | 17.12 | 17.85 | 20.09 | 20.59 | 20.21 | 15.98 | 15.30 | 9.82 | 9.47 | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Referrals | (count) | 3527 | 10 313 | 10 199 | 9568 | 9582 | 10 071 | 8885 | 6681 | 5152 | 3595 | 2321 | 1217 |

| (% of population) | 1.39 | 3.52 | 3.91 | 3.19 | 2.71 | 2.78 | 2.74 | 2.17 | 1.49 | 1.26 | 0.95 | 0.57 | |

| (% of CMHP cases) | 10.08 | 22.95 | 20.70 | 18.64 | 15.16 | 13.86 | 13.29 | 10.74 | 9.34 | 8.23 | 9.71 | 6.00 | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Attenders | (count) | 2033 | 5913 | 6205 | 6155 | 6438 | 6916 | 6400 | 4868 | 3954 | 2767 | 1774 | 905 |

| (% of population) | 0.80 | 2.02 | 2.38 | 2.05 | 1.82 | 1.91 | 1.97 | 1.58 | 1.15 | 0.97 | 0.73 | 0.42 | |

| (% of CMHP cases) | 5.81 | 13.16 | 12.59 | 11.99 | 10.19 | 9.52 | 9.57 | 7.83 | 7.17 | 6.34 | 7.43 | 4.46 | |

| (% of referrals) | 57.64 | 57.34 | 60.84 | 64.33 | 67.19 | 68.67 | 72.03 | 72.86 | 76.75 | 76.97 | 76.43 | 74.36 | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Completers (≥2 sessions) | (count) | 675 | 2384 | 2492 | 2486 | 2716 | 2949 | 2723 | 2139 | 1819 | 1266 | 797 | 412 |

| (% of population) | 0.27 | 0.81 | 0.96 | 0.83 | 0.77 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.70 | 0.53 | 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.19 | |

| (% of CMHP cases) | 1.93 | 5.30 | 5.06 | 4.84 | 4.30 | 4.06 | 4.07 | 3.44 | 3.30 | 2.90 | 3.34 | 2.03 | |

| (% of referrals) | 19.14 | 23.12 | 24.43 | 25.98 | 28.34 | 29.28 | 30.65 | 32.02 | 35.31 | 35.22 | 34.34 | 33.85 | |

| (% of attenders) | 33.20 | 40.32 | 40.16 | 40.39 | 42.19 | 42.64 | 42.55 | 43.94 | 46.00 | 45.75 | 44.93 | 45.52 | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Reliable improvement (achieving MCID) | (count) | 263 | 884 | 983 | 994 | 1121 | 1269 | 1143 | 906 | 789 | 560 | 368 | 135 |

| (% of population) | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.38 | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.29 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.06 | |

| (% of CMHP cases) | 0.75 | 1.97 | 2.00 | 1.94 | 1.77 | 1.75 | 1.71 | 1.46 | 1.43 | 1.28 | 1.54 | 0.67 | |

| (% of referrals) | 7.46 | 8.57 | 9.64 | 10.39 | 11.70 | 12.60 | 12.86 | 13.56 | 15.31 | 15.58 | 15.86 | 11.09 | |

| (% of attenders) | 12.94 | 14.95 | 15.84 | 16.15 | 17.41 | 18.35 | 17.86 | 18.61 | 19.95 | 20.24 | 20.74 | 14.92 | |

| (% of completers) | 38.96 | 37.08 | 39.45 | 39.98 | 41.27 | 43.03 | 41.98 | 42.36 | 43.38 | 44.23 | 46.17 | 32.77 | |

CMHP = common mental health problem. MCID = minimal clinical important difference.

Estimated prevalence of CMHPs peaks in 45–49-year-olds (20.59%), with lowest estimated prevalence in 70–74-year-olds (9.47%). Referral rates as a proportion of CMHPs peak in 20–24-year-olds (22.95%) and then decrease from this point until 74 years of age (6.00%). Attendance rates as a proportion of referrals peak in 60–64-year-olds (76.97%) with lowest attendance rates in 20–24-year-olds (57.34%). Further detail can be found in Table 1.

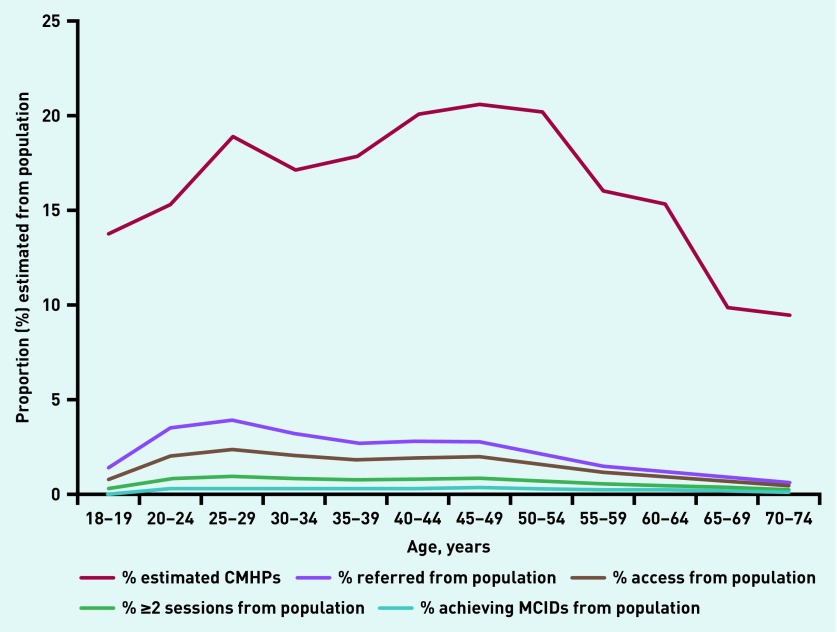

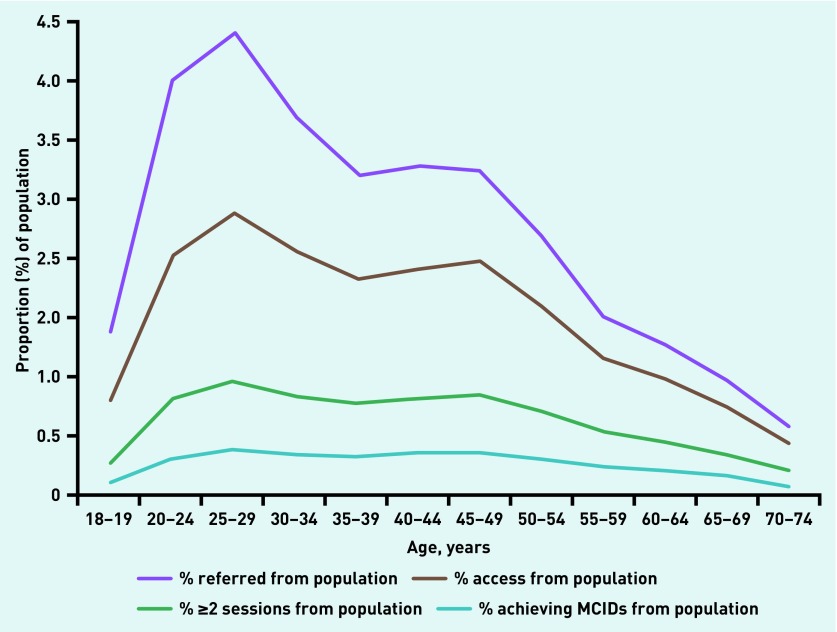

The proportions of the population being referred, obtaining access, engaging with treatment, and achieving MCID each peak in 25–29-year-olds and decline thereafter, with lowest numbers for 70–74-year-olds. Figure 1 shows the contrast graphically. Figure 2 depicts a ‘vertically magnified’ version of Figure 1, showing the proportion of the population referred, obtaining access, continuing with treatment, and achieving MCID from the total population.

Figure 1.

Estimated proportion of CMHPs and number of those: referred, with access, with ≥2 sessions, achieving MCID as a proportion of total population across age in the South West of England. CMHP = common mental health problem. MCID = minimal clinical important difference.

Figure 2.

Proportion of those: referred, with access, with ≥2 sessions, achieving MCID of total population across age in the South West of England. MCID = minimal clinical important difference.

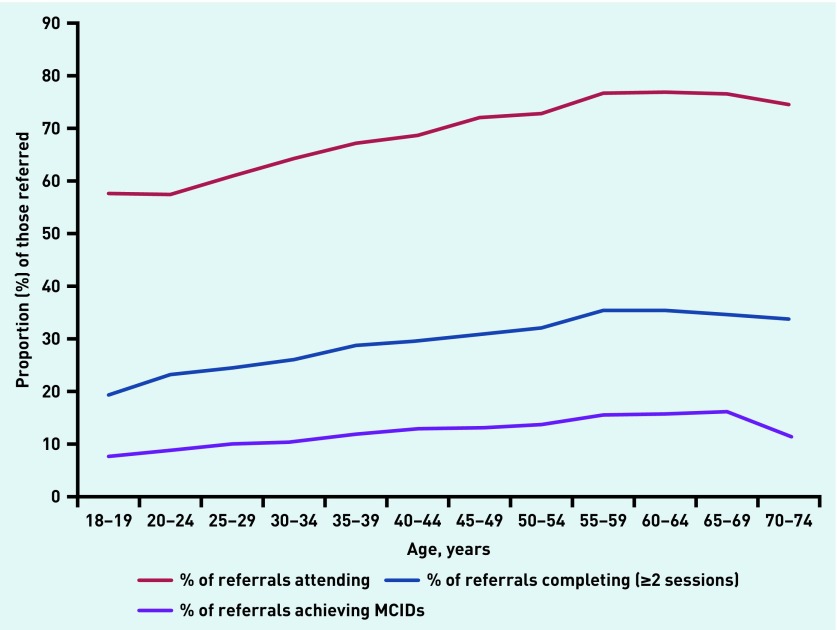

Access uptake, continued treatment, and achieving MCID, represented as a proportion of referrals, is depicted in Figure 3. Of those referred: proportions of people obtaining access increases until 64 years (76.97%); proportions of people with ≥2 treatment sessions increases until 59 years (35.31%); and proportions of people achieving MCID increases from 18 years until 69 years (15.86%).

Figure 3.

Number of those: with access, with ≥2 sessions, achieving MCID as a proportion of those referred across age in the South West of England. MCID = minimal clinical important difference.

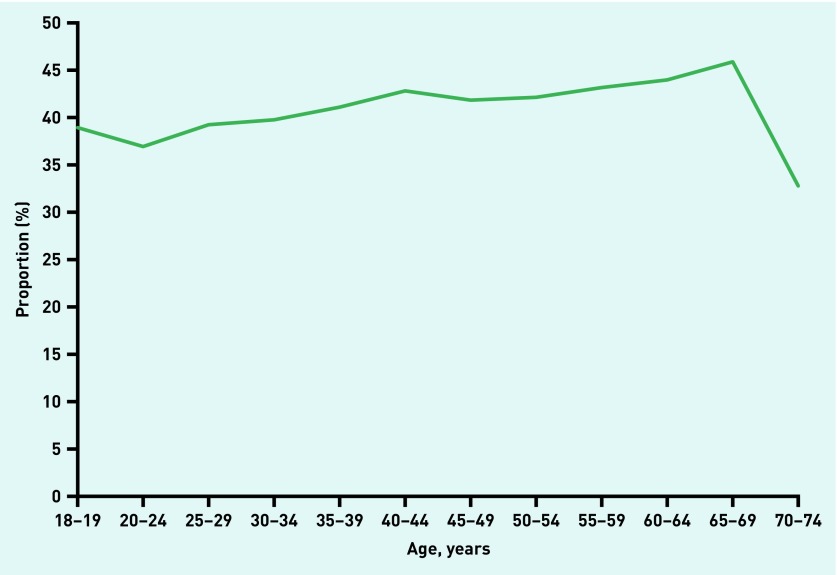

The age group with the lowest proportion achieving MCID or reliable improvement is 70–74-year-olds (32.77%) but otherwise the percentage with MCID gradually increases from those aged 20–24 (37.08%) to those 65–69 years (46.17%), this age group having the highest proportion achieving MCID (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Those achieving minimal clinical important difference as a proportion of those with ≥2 treatment sessions across age in the South West of England. MCID = minimal clinical important difference.

In summary, more referrals are made for younger adults with a peak age of 25–29 years as a proportion of the total population and a peak age of 20–24 years as a proportion of those with CMHPs, but, once referred, a higher proportion of older adults are engaging with and benefiting from treatment than are 20–29-year-olds.

DISCUSSION

Summary

Concerns about discrimination against older adults leading to reduced access to talking therapies have been widely shared.2,3 The current study has shown, taking estimated prevalence into account, that access is indeed lower for older and middle-aged adults compared with younger adults. The estimated prevalence of CMHPs peaks in 45–49-year-olds but the proportions of those being referred peaks in 20–24-year-olds. This is an important finding as it is possible that, given lower uptake, retention, and improvement, there is over-referral of younger patients who either find it difficult to engage, or who are less likely to improve if they do engage, or who do not see the value of talking therapies at this point in their lives.

This study also showed that, once referred, older adults may benefit more from the IAPT services. Of those referred, the proportion of those obtaining access increases until 64 years, engaging with treatment increases until 59 years, and achieving MCID increases until 69 years. Once referred, adherence to and recovery resulting from treatment increases with age, and higher proportions of older adults are accessing and engaging with treatment than the 20–24-year-olds, who are being referred more frequently.

Strengths and limitations

The data represent populations who have been referred to the IAPT services, and not those using other primary or secondary care services. It is important to note that the APMS only included those living in private households, and not those in care homes.21 Nonetheless, the APMS series is the most recent and detailed data available for comparison of IAPT services use.

The data described above are purely quantitative and although it is possible to speculate, it is difficult to explain why these differences in referral, engagement, and outcome exist between patients from different age groups. Other studies have indicated some of the potential reasons in relation to service configuration but have not focused on older adults.22

Comparison with existing literature

Patients can be signposted to the IAPT services by any appropriate referrer, and the main source of referrals is the GP. As such, GP decision making and practices regarding referral to psychological therapy services will have a large impact on access for patients. Cooper and colleagues8 found younger adults (16–34 years) more likely than older adults (≥75 years) with the same severity to have seen their GP regarding a mental health issue and to be receiving talking therapy treatment. A combination of factors may contribute to lower referral rates of older adults by healthcare professionals:

self-stigma towards mental health in older adults, leading to reduced disclosure and requests for help;11,14,15

increased likelihood of older adults receiving prescribed medication(s);8

attitudes of professionals;10

multimorbidity in older adults leading to reduced recognition of mental health issues; and

system factors that prevent access to those who are frail or homebound.

It seems likely that reasons for the reduced referral shown by this study are multifactorial. However, given that there are much higher contact rates between GPs and older adults than with younger adults, the reduced referral rates are even more striking. Although there are good grounds for believing that GPs may not be offering the opportunity of referral to older adults, it is also likely that these patients may believe they can ‘manage themselves’, making them less likely to disclose information to their GP, or accept suggested help.14,15

The estimated capacity of the patient to benefit from psychological therapy is a prominent feature included in a GP’s referral decision23 and the GP may also assume certain age groups will not engage with the service.

Implications for practice

A number of factors are likely to affect access to IAPT services. Where possible, these need to be considered when evaluating the ability of new IAPT services to achieve their access targets. When considering age and specific age groups facing barriers to use of IAPT services, the main inequity seems to be at the referral stage. Although 20–29-year-olds are being referred in the largest numbers, the proportion remaining engaged with treatment increases with age. Barriers to engagement with IAPT services in younger populations may be overcome by using different technologies, for example. Older adults are being under-referred but benefit significantly once obtaining access to the services. This suggests these inequities need to be acknowledged and addressed. Several barriers to treatment associated with age have been identified in recent work, including older patients’ own perceptions, attitudes, and behaviours towards mental health and associated talking treatments, and communication problems between the patient and doctor.

The current study should demonstrate to GPs that older patients are both more likely to attend and more likely to benefit once engaged in treatment. GPs should perhaps therefore work to discuss mental health problems with older adults and increase awareness of the different available therapies, and their potential benefits. IAPT services may also need to take note. Although those older adults who were referred attended more reliably, it is possible that the nature of services are more suited to young people and that this is a disincentive to referral. These considerations may also apply to those in middle age. It is harder to draw conclusions about younger people and it is not clear whether, in some high-referring PCTs, higher numbers of young people are presenting with distress or access for younger people has achieved an optimum. It is also possible that, if therapy engagement can be improved in people in these younger age groups, they will be more likely to benefit from these types of treatments.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the IAPT services for contributing to the research commissioned by the South West Strategic Health Authority in England.

Funding

This work was conducted as part of the South West of England IAPT Evaluation Project, commissioned by the South West Strategic Health Authority, with additional contributions from the National Institute for Health Research’s Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care for the South West Peninsula towards supporting Adam Qureshi and Richard Byng. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS or the NIHR.

Ethical approval

The dataset was created for a service evaluation project of the IAPT services commissioned by the South West Strategic Health Authority. Ethical approval was sought from and granted by the Cornwall and Plymouth Research Ethics Committee (ref. 09/H0203/91).

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson D, Banerjee S, Barker A, et al. The need to tackle age discrimination in mental health A compendium of evidence. London: Faculty of Old Age Psychiatry, Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2009. http://docplayer.net/107785-The-need-to-tackle-age-discrimination-in-mental-health-a-compendium-of-evidence.html (accessed 15 Mar 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health . Improving access to psychological therapies. Implementation plan: national guidelines for regional delivery. London: DH; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.NHS . Older people: positive practice guide. London: DH; 2009. Improving access to psychological therapies. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McManus S, Meltzer H, Brugha T, et al. Adult psychiatric morbidity in England, 2007: results of a household survey. Leeds: NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henderson A, Jorm A, Korten A, et al. Symptoms of depression and anxiety during adult life: evidence for a decline in prevalence with age. Psychol Med. 1998;28(6):1321–1328. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stordal E, Mykletun A, Dahl A. The association between age and depression in the general population: a multivariate examination. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;107(2):132–141. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.02056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olfson M, Pincus H. Outpatient mental health care in nonhospital settings: distribution of patients across provider groups. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(10):1353–1356. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.10.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper C, Bebbington P, McManus S, et al. The treatment of common mental disorders across age groups: results from the 2007 Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. J Affect Disord. 2010;127(1–3):96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McPherson I. Mental health problems in old age: double discrimination or everybody’s business? . Scribd. 2008. https://www.scribd.com/document/149629849/Mental-Health-Problems-in-Old-Age# (accessed 22 May 2017)

- 10.Murray J, Banerjee S, Byng R, et al. Primary care professionals’ perceptions of depression in older people: a qualitative study. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(5):1363–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ross H, Hardy G. GP referrals to adult psychological services: a research agenda for promoting needs-led practice through the involvement of mental health clinicians. Br J Med Psychol. 1999;72(Pt1):75–91. doi: 10.1348/000711299159835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meltzer H, Bebbington P, Dennis M, et al. Feelings of loneliness among adults with mental disorder. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(1):5–13. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0515-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Serfaty M, Haworth D, Blanchard M, et al. Clinical effectiveness of individual cognitive behaviour therapy for depressed older people in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(12):1332–1340. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell A, Selmes T. Why don’t patients attend their appointments? Maintaining engagement with psychiatric services. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2007;13(6):423–434. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wetherell J, Kaplan R, Kallenberg G, et al. Mental health treatment preferences of older and younger primary care patients. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2004;34(3):219–233. doi: 10.2190/QA7Y-TX1Y-WM45-KGV7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Department of Health, Mental Health Division, IAPT Programme . The IAPT Pathfinders: achievements and challenges. London: DH; 2008. Improving Access to Psychological Therapies. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis G, Pelosi AJ, Araya R, Dunn G. Measuring psychiatric disorder in the community: a standardized assessment for use by lay interviewers. Psychol Med. 1992;22(2):465–486. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700030415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spitzer R, Kroenke K, Williams J. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spitzer R, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Int Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Copay AG, Subach BR, Glassman SD, et al. Understanding the minimum clinically important difference: a review of concepts and methods. Spine J. 2007;7(5):541–546. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glover G. Estimating the prevalence of common mental health problems in PCTs in England. 2008. Mental Health Observatory Briefs. Stockton-on-Tees: Mental Health Observatory.

- 22.Marshall D, Quinn C, Child S, et al. What IAPT services can learn from those who do not attend. J Ment Health. 2015;3:410–415. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2015.1101057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stavrou S, Cape J, Barker C. Decisions about referrals for psychological therapies: a matched-patient qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2009. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp09X454089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]