Abstract

Introduction:

Trauma in elderly population is frequent and is associated with significant mortality, not only due to age but also due to complicated factors such as the severity of injury, preexisting comorbidity, and incomplete general assessment. Our primary aim was to determine whether age, Injury Severity Score (ISS), and preexisting comorbidities had an adverse effect on the outcome in patients aged 65 years and above following blunt trauma.

Methods:

We included 1027 patients aged ≥65 years who were admitted to our Level I Trauma Center following blunt trauma. Patients’ charts were reviewed for demographics, ISS, mechanism of injury, preexisting comorbidities, Intensive Care Unit and hospital length of stay, complications, and in-hospital mortality.

Results:

The mean age of injured patients was 78.8 ± 8.3 years (range 65–109). The majority of patients had mild injury severity (ISS 9–14, 66.8%). Multiple comorbidities (≥3) were found in 233 patients (22.7%). Mortality during the hospitalization stay (n = 35, 3.4%) was associated with coronary artery disease, renal failure, dementia, and warfarin use (P < 0.05). Chronic anticoagulation treatment was recorded in 13% of patients. The addition of a single comorbidity increased the odds of wound infection to 1.29 and sepsis to 1.25. Both age and ISS increased the odds of death as −1.08 and −2.47, respectively.

Conclusions:

Our analysis shows that age alone in elderly trauma population is not a robust measure of outcome, and more valuable predictors such as injury severity, preexisting comorbidities, and medications are accounted for adverse outcome. Trauma care in this population with special considerations should be tailored to meet their specific needs.

Keywords: Blunt trauma, complications, geriatric trauma, injury severity, mortality

INTRODUCTION

The Western population is living longer and aging rapidly. This demographic shift challenges the whole health-care system. Geriatric trauma patients are unique and represent a particular challenge to care providers.[1] Currently, traumatic injuries are the fifth leading cause of death in elderly patients.[2] Worse outcomes have been reported in geriatric trauma compared to younger counterparts.[3,4,5,6] However, early and aggressive care of elderly trauma patients has positive effect on outcome in this population group.[7,8]

Seniors are experiencing physiological and psychological changes, particularly when an elderly person experiences trauma for various reasons. Falls and car accidents are often mentioned. Fainting or loss of consciousness due to underlying diseases was the main cause for falls in the elderly although the reason is not always obvious.[9]

It is of general knowledge that trauma-related mortality increases with advanced age. Furthermore, elderly trauma patients often have comorbidities, which are additional risk factors for adverse outcome compared to younger population. Continuing advancements in the management of chronic diseases have resulted in a more active lifestyle in elderly individuals, predisposing them to injury.[10] Moreover, there seems to be a connection between injury severity and additional comorbidities with an increase in mortality.[11]

As the population ages, an increasing number of trauma patients receive chronic antiplatelets and anticoagulant treatment. These medications increase the risk of hemorrhagic complications, particularly intracranial hemorrhage. Surgical wound infections, pneumonia, and other infectious complications caused extended length of stay (LOS) in Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and doubled the amount of general admission in the hospital.[12] An awareness and better understanding of socioeconomic and clinical variables will directly influence the mortality and morbidity in this population group.

Our objective was to determine and quantify the impact of age, injury severity, and preexisting comorbidities on outcome in patients aged ≥65 years following blunt trauma.

METHODS

Our study was reviewed and approved by the local Institutional Review Board. We included all patients aged ≥65 years who presented and hospitalized to our Level I Trauma Center in a 2-year period (January 2012–December 2013) following blunt trauma. Any types of blunt trauma mechanism were included: falls and car accidents including both inside car injured and pedestrian.

Patients following any penetrating trauma, burns, and assault were excluded from the study. Patients who were pronounced dead on arrival at the trauma bay or had do-not-resuscitate order were also excluded from the study.

All charts were retrospectively reviewed for demographics (age and gender), Glasgow coma scale at presentation to the emergency department, mechanism of injury (MOI), preexisting comorbidities, Intensive Care Unit (ICU) length of stay (LOS), hospital LOS, surgical interventions, complications, and in-hospital mortality. Injury Severity Score (ISS)[13] was calculated from prospectively collected data for all admitted trauma patients. The main outcome measure was in-hospital mortality. In-hospital complications were recorded following trauma quality improvement assessment and classified as hospital-acquired pneumonia, surgical site infection, venous thrombotic event, and sepsis. Each complication was proved by clinical, laboratory, and radiological data. Patients received anticoagulants and antiplatelets medication (including acetylsalicylic acid) before acute trauma admission were recorded. Discharge placement was defined as the patient's destination after acute care in the trauma center: rehabilitation center, assisted-living facility (ALF) (defined as lower level of dependence requiring professional support), home, or transfer to another acute care hospital. Comorbidities were defined as presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comorbidities identified in the study population

Patients following minor trauma (contusions of chest wall, soft tissue injuries of minor face injury) were hospitalized for observation based on the decision of attending surgeon. Furthermore, chronic anticoagulation/antiaggregation therapy was often a reason for in-hospital observation.

Statistical analysis

For quantitative variables, data are presented as mean and standard deviation. The Chi-square test was used to test the association between two qualitative variables. The Chi-square test for trends was used for qualitative ordinal variables. The Student's t-test was used to compare quantitative variables between the two groups. A univariate analysis was performed. A logistic regression model was used to define predictors of death. To determine predictors of in-hospital death, parameters that were significant on univariate analysis were entered into a stepwise, forward regression model. The adjusted odds ratio (aOR) as well as its 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated for parameters that were found to be significant in univariate analysis. All tests applied were two-tailed, with P ≤ 0.05 considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM Corporation Released 2011, IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corporation, NY, USA).

RESULTS

Patient population

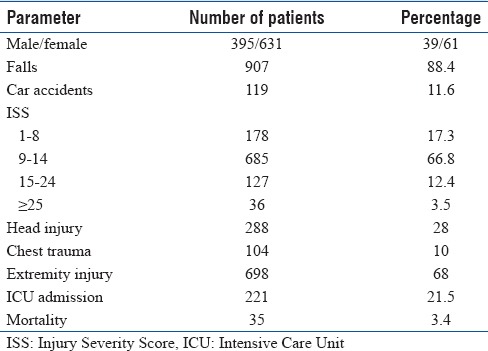

During the study, there were 1027 hospital admissions following blunt trauma. One patient was excluded for lack of data. The mean age of injured patients was 78.8 ± 8.3 years (range 65–109). Demographical data of study group are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Description of study population

Falls (all low energy) was a main MOI (907, 88%) followed by motor vehicle crush and pedestrian injury (119, 11.6%). Orthopedic trauma followed by head trauma (or combined) was the reason for hospital stay in majority of the cases (68 and 28%, respectively). Ten percent of patients had chest trauma (often ribs fractures).

The ISS distribution showed that the majority of patients had mild injury severity (ISS 9–14, 66.8%). The median hospital LOS was 7 days and varied from 1 to 116 days. Patients with minor injuries (ISS 1–8, 178 patients, 17.3%) were often left for observation and pain management, especially when serious comorbidities were noted. There was no mortality in this subgroup.

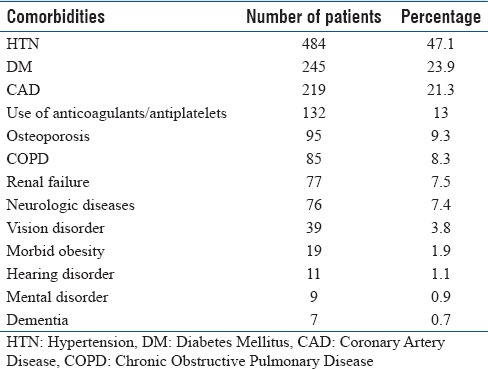

Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and coronary artery disease (CAD) were the most frequent comorbidities in the study group [Table 3]. Thirteen percent of patients used chronic anticoagulation (warfarin, 44 patients, 4.3%) or antiplatelets treatment (aspirin: 89 patients, 8.7%; clopidogrel: 5 patients, 0.5%). Multiple comorbidities (≥3) were found in 233 patients (22.7%).

Table 3.

Comorbidity data in study group

Complications and mortality

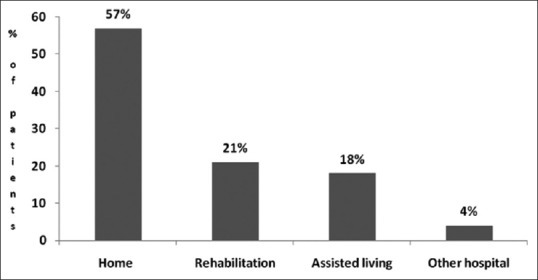

In-hospital complications were recorded in 209 (21%) survivors (n = 991). Sepsis and pneumonia were the most common complications (69 patients, 7% and 67, 6.7%, respectively). Any surgical site infections were found in 49 patients (4.9%). Venous thromboembolic events were detected in 24 cases (2.4%) based on clinical suspension. The discharge destination was noticed in 750 patients (75%), who survived hospital stay (991 patients). Home discharge (n = 430, 57%) was most commonly followed by rehabilitation facilities (n = 160, 21%). Eighteen percent (n = 132) of patients required ALF following hospital stay [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Discharge destination distribution in patients’ population

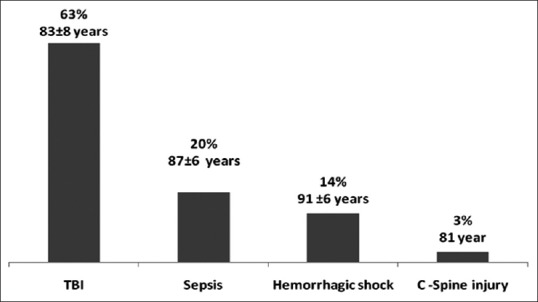

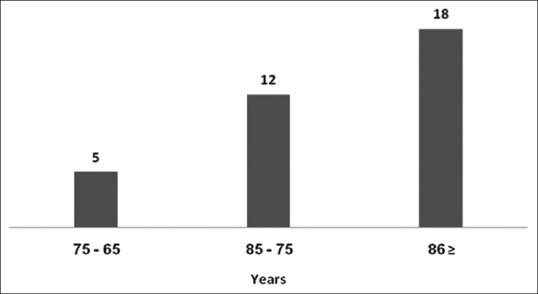

All study group mortality was noticed in 35 cases (3.4%). Analysis of our data showed that 22 patients (63%) died from severe head trauma on median posttrauma day 8 (range 1–11). Another 7 (20%) patients died from sepsis and multi-organ failure, and others from severe multitrauma and hemorrhagic shock and high spinal injury [Figure 2]. Mortality increased with age [Figure 3]. Of 35 deceased, 18 (51%) were above 86 years old.

Figure 2.

Cause of death in 35 patients. TBI – Traumatic brain injury

Figure 3.

Mortality exponentially increased in elder age group (absolute numbers were used)

In the group of patients who passed away during their hospital stay, a statistically significant association was found between death and existence of certain comorbidities (CAD, renal failure, dementia, and warfarin use; P < 0.05). In 29 mortality cases (83%), at least a single comorbidity was noticed versus no co-morbidities in 705 survivors (71%).

Predicting factors of complications and mortality

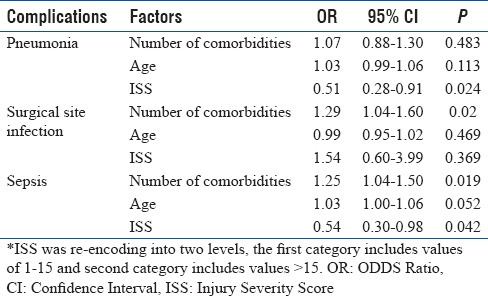

To examine all the factors that may predict the incidence of complications during hospitalization, multivariate logistic regression was used. Our results showed that the number of comorbidities and the ISS score were found to be definite risk factors for additional morbidity in elderly trauma patients. Table 4 presents the odds ratios (ORs) of relative risk of complications’ events, included in the study: pneumonia, surgical site infection, and sepsis. Pulmonary embolism was excluded from analysis due to the small number of observations.

Table 4.

Odds ratio, confidence intervals, and statistical significance of predictors of complications included in the regression analysis

The addition of single comorbidity increases the odds of wound infection to 1.29 and increases the odds to develop sepsis to 1.25. The addition of 1 year to the patient's age increases the odds of sepsis to 1.03 although this relationship seems weak. An increase in the ISS does not increase the risk of pneumonia and sepsis.

Multivariate regression analysis was performed to identify predictors of mortality. Parameters which were found significant on univariate analysis were entered into a forward stepwise regression model. Older age (aOR = 1.1, 95% CI: 1–1.1, P = 0.001), ISS (aOR = 2.47, CI: 1.18–5.19, P = 0.02), and number of comorbidities (aOR = 1.3, 95% CI: 1.1–1.8, P = 0.02) were found to be independent predictors of mortality in elderly trauma patients.

DISCUSSION

Our analysis suggests that chronological age alone in the population of patients aged 65 years and above is not a strong predictor of outcome following trauma. In the hospitalized elderly trauma cohort, the addition of a single comorbidity increases the risk of developing a wound infection by 1.29 times and a risk of sepsis by 1.25 times but does not affect the rate of pneumonia. No statistically significant correlation was found between increasing age and morbidity. Altogether, adding up a single comorbidity, along with an increase in ISS (>15) increases the risk of mortality. Furthermore, the chance of death increases in every additional year (aOR = 1.1, P = 0.001).

We found that chronological age is not a major predictor of mortality; once, more important predictors, such as injury severity and baseline physical health, are taken into account. In our study, the mean age of the patients was 78.8 years, with minor and mild trauma according to ISS score below 15 occurring in 836 of patients (84%) and overall mortality of 3.4%. Perdue et al. found that mortality in elderly patients was twice that of younger patients with comparable ISS.[4]

In the population studied, we found that ISS was a predictor of in-hospital mortality (OR = 2.47, CI: 1.18–5.19, P = 0.017). However, in our previous paper analyzing in-hospital mortality in the severely injured elderly (ISS > 15), we found that on univariate analysis, ISS was significantly higher in the nonsurvivor group (P < 0.0001).[14] However, on multivariate analysis, ISS was not a predictor of in-hospital mortality. That means that current trauma scoring systems are insufficient in directing management and predicting survival for severely injured elderly patients. Preexisting comorbidities can adversely affect a patient's recovery from a traumatic injury.[15,16,17] Hollis et al. have demonstrated that preexisting medical conditions and increased age are independent risk factors of mortality after trauma.[18]

The predominant MOI was falls in 88% in the population, which is a common geriatric syndromal entity, while car accidents accounted for 12% of the trauma. Low-level falls (falls from a standing height) are the most common reason for injury in geriatric patients. Complications resulting from falls are the leading cause of death from injury in this population. Increased morbidity is associated with increased disability, hospital admissions, and inpatient LOS. In our study group, 132 patients (18%) were discharged to ALF. Home discharge or transfers to a rehabilitation facility were associated with long-term survival.[14]

We examined comorbidities which are well known to affect survival. On univariate analysis, CAD, renal failure, dementia, and warfarin use were associated with in-hospital mortality.

Taylor et al. in their analysis of 26,237 blunt geriatric trauma patients found an association between preexisting medical conditions and the development of specific complications after injury, all of which contributed to increased mortality and increased hospital and ICU LOS.[19] It has been previously reported in orthopedic trauma patients with typical femoral fractures that pulmonary and infectious complications are predominant.[20] In our population, pulmonary and infectious complications did not appear to affect survival.

The present study is limited by its retrospective design and recruitment from a single hospital.

We collected data of geriatric trauma patients as a general cohort. No specific organ injury or subgroup analysis of injury severity and age subgroup were analyzed separately.

CONCLUSIONS

In our cohort, we found that the overall mortality rate in geriatric trauma patients was 3.4%. The odds of in-hospital mortality increase with advance in age; however, morbidity does not change significantly. We also established that in geriatric trauma patients, a higher ISS associated with comorbidities number was found to be significant risk factors for mortality and infectious complications. Therefore, in the management of geriatric trauma patient, considering age alone is not sufficient. The severity of the injury along with the number preexisting comorbidities is established risk factors for infectious complications and should be taken into account during assessment and treatment. Identifying patients at risk of in-hospital complications, and developing tailored preventive strategies (such as geriatric trauma team assessment), should be a focus to improve care for the elderly trauma patient on hospital and national level.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moore L, Turgeon AF, Sirois MJ, Lavoie A. Trauma centre outcome performance: A comparison of young adults and geriatric patients in an inclusive trauma system. Injury. 2012;43:1580–5. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aschkenasy MT, Rothenhaus TC. Trauma and falls in the elderly. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2006;24:413–32, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oreskovich MR, Howard JD, Copass MK, Carrico CJ. Geriatric trauma: Injury patterns and outcome. J Trauma. 1984;24:565–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perdue PW, Watts DD, Kaufmann CR, Trask AL. Differences in mortality between elderly and younger adult trauma patients: Geriatric status increases risk of delayed death. J Trauma. 1998;45:805–10. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199810000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osler T, Hales K, Baack B, Bear K, Hsi K, Pathak D, et al. Trauma in the elderly. Am J Surg. 1988;156:537–43. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(88)80548-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finelli FC, Jonsson J, Champion HR, Morelli S, Fouty WJ. A case control study for major trauma in geriatric patients. J Trauma. 1989;29:541–8. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198905000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demetriades D, Karaiskakis M, Velmahos G, Alo K, Newton E, Murray J, et al. Effect on outcome of early intensive management of geriatric trauma patients. Br J Surg. 2002;89:1319–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKinley BA, Marvin RG, Cocanour CS, Marquez A, Ware DN, Moore FA. Blunt trauma resuscitation: The old can respond. Arch Surg. 2000;135:688–93. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.6.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendelson G, Ben-Israel J. Utilization of external hip protectors in frail elderly residents of nursing homes. Harefuah. 2005;144:112–4, 150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs DG. Special considerations in geriatric injury. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2003;9:535–9. doi: 10.1097/00075198-200312000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shoko T, Shiraishi A, Kaji M, Otomo Y. Effect of pre-existing medical conditions on in-hospital mortality: Analysis of 20,257 trauma patients in Japan. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:338–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sikand M, Williams K, White C, Moran CG. The financial cost of treating polytrauma: Implications for tertiary referral centres in the United Kingdom. Injury. 2005;36:733–7. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2004.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyd CR, Tolson MA, Copes WS. Evaluating trauma care: The TRISS method. Trauma score and the injury severity score. J Trauma. 1987;27:370–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bala M, Willner D, Klauzni D, Bdolah-Abram T, Rivkind AI, Gazala MA, et al. Pre-hospital and admission parameters predict in-hospital mortality among patients 60 years and older following severe trauma. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2013;21:91. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-21-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sasser SM, Hunt RC, Faul M, Sugerman D, Pearson WS, Dulski T, et al. Guidelines for field triage of injured patients: Recommendations of the National Expert Panel on Field Triage, 2011. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;61:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niven DJ, Kirkpatrick AW, Ball CG, Laupland KB. Effect of comorbid illness on the long-term outcome of adults suffering major traumatic injury: A population-based cohort study. Am J Surg. 2012;204:151–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heffernan DS, Thakkar RK, Monaghan SF, Ravindran R, Adams CA, Jr, Kozloff MS, et al. Normal presenting vital signs are unreliable in geriatric blunt trauma victims. J Trauma. 2010;69:813–20. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181f41af8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hollis S, Lecky F, Yates DW, Woodford M. The effect of pre-existing medical conditions and age on mortality after injury. J Trauma. 2006;61:1255–60. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000243889.07090.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor MD, Tracy JK, Meyer W, Pasquale M, Napolitano LM. Trauma in the elderly: Intensive care unit resource use and outcome. J Trauma. 2002;53:407–14. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200209000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liem IS, Kammerlander C, Raas C, Gosch M, Blauth M. Is there a difference in timing and cause of death after fractures in the elderly? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:2846–51. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-2881-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]