Abstract

Insulin like growth factor II receptor (IGFIIR) is a transmembrane protein overexpressed in activated hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), which are the major target for the treatment of liver fibrosis. In this study, we aim to discover an IGFIIR-specific aptamer that can be potentially used as a targeting ligand for the treatment and diagnosis of liver fibrosis. Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) was conducted on recombinant human IGFIIR to identify IGFIIR-specific aptamers. The binding affinity and specificity of the discovered aptamers to IGFIIR and hepatic stellate cells were studied using flow cytometry and Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR). Aptamer-20 showed the highest affinity to recombinant human IGFIIR protein with a Kd of 35.5 nM, as determined by SPR. Aptamer-20 also has a high affinity (apparent Kd 45.12 nM) to LX-2 human hepatic stellate cells. Binding of aptamer-20 to hepatic stellate cells could be inhibited by knockdown of IGFIIR using siRNA, indicating a high specificity of the aptamer. The aptamer formed a chimera with an anti-fibrotic PCBP2 siRNA and delivered the siRNA to HSC-T6 cells to trigger silencing activity. In Vivo biodistribution study of the siRNA-aptamer chimera also demonstrated a high and specific uptake in the liver of the rats with CCl4-induced liver fibrosis. These data suggest that aptamer-20 is a high-affinity ligand for antifibrotic and diagnostic agents for liver fibrosis.

Keywords: aptamer, SELEX, siRNA chimera, liver fibrosis, hepatic stellate cells, IGFIIR, imaging, targeted delivery, PCBP2.

Introduction

Liver cirrhosis, which is an advanced stage of liver fibrosis, is a worldwide health problem that was responsible for more than one million deaths in 2010 1. Liver fibrosis is a wound healing process characterized by the accumulation of excess extracellular matrix. Liver fibrosis originates with various chronic liver injuries and the activation of collagen-producing cells. As the primary component of the extracellular matrix, type I collagen is mainly produced by activated hepatic stellate cells (HSCs). HSCs are therefore the key pathogenic cells that are involved in liver fibrogenesis. There is clinical evidence that liver fibrosis is reversible but cirrhosis is irreversible 2. However, there is still no acceptable therapeutic strategy for the treatment of liver fibrosis.

HSCs have attracted much attention as targets for the treatment of liver fibrosis during the last decade. However, anti-fibrotic agents are not taken up efficiently by HSCs because of the closure of endothelial fenestrae and an increased resistance of the sinusoidal lumen to blood flow 3. Therefore, developing a targeted delivery system for HSCs is urgent. Several approaches have been reported for the delivery of drugs to HSCs. For example, vitamin A has been conjugated to liposome for the delivery of siRNA for liver fibrosis therapy because HSCs are the major storage site of vitamin A 4. Peptides have also been studied as ligands for targeted delivery to HSCs. A platelet derived growth factor (PDGF) beta receptor-recognizing peptide was conjugated with albumin for the delivery of interferon gamma to activated HSCs because PDGF receptors are highly expressed on activated HSCs 5.

Insulin like growth factor II receptor (IGFIIR), also known as mannose 6 phosphate receptor (M6PR), is a cation-independent glycoprotein that is comprised of three major regional domains, including the cytoplasmic domain, the transmembrane domain and the extracellular domain 6. The function of transporting bound ligands into cytoplasm from the membrane is the most attractive feature of IGFIIR that can be utilized for developing targeted drug delivery systems 7. We have identified a specific peptide that binds to IGFIIR on LX-2 human HSCs and HSC-T6 rat cells with high binding affinity 8. A dimeric form of the peptide further improves its binding affinity to LX-2 cells. However, the apparent Kd values of these peptides are in the range of 700 nM to 6 µM, which is higher compared to antibody or aptamer. In addition, the peptide ligand has to be chemically conjugated to siRNA or its delivery system to deliver them to HSCs.

Aptamers, including RNA aptamers and DNA aptamers, are small nucleic acids that bind to a great variety of targets with extremely high specificity and affinity. Aptamers have been studied as therapeutics and targeting ligands for more than two decades. Aptamers can be potentially exploited as therapeutics in three ways: 1) aptamers can serve as an agonist to activate the function of a cellular receptor; 2) aptamers can also serve as an antagonist to block protein-protein interaction or receptor-ligand interaction; and 3) aptamers can be utilized as a carrier to specifically deliver therapeutic agents to their targets 9-14. Macugen, also known as pegaptanib, is the first aptamer approved by the FDA in 2004 for the treatment of neovascular (wet) age-related macular degeneration15. There are several other aptamers that are in different phases of clinical studies 16. Aptamers have also been widely studied for the delivery of siRNA in three approaches: 1) siRNA encapsulating nanoparticles can be modified with aptamers to increase their cellular uptake and tissue specificity; 2) siRNA can be annealed with aptamers to form siRNA-aptamer chimera via sticky bridge; and 3) siRNA can be chemically linked to aptamers to form siRNA-aptamer chimera 17-20. Among them, siRNA-aptamer chimera formed by annealing of sticky bridge has attracted much attention because of its ease of construction. For example, an siRNA was successfully delivered into HIV infected cells after forming siRNA-aptamer chimera with an aptamers via a sticky bridge 21. In our study, a systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) was conducted to identify IGFIIR-specific aptamers that have a higher binding affinity and are easier to anneal with siRNA. The binding affinity and specificity of these aptamers were evaluated in human HSC LX-2 and rat HSC-T6 cells. The siRNA-aptamer chimera demonstrated high cellular uptake and silencing activity in HSCs. Biodistribution of the siRNA-aptamer chimera also demonstrated high and specific uptake in the liver of the rats with CCl4-induced liver fibrosis.

Materials and Methods

Materials

The single-stranded DNA library containing two 18-base primer regions and a 40-base random region (5'-AGA GTG CTG TTA CTA TCG-N40-AAC TGA ACA AGG TGG TAT-3') and all aptamers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA). Recombinant human IGFIIR extracellular domain with His-tag (Accession # P11717.2, Ser1510-Phe2108) and anti-human IGFIIR antibody were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Non-enzymatic cell dissociation solution was purchased from MP Biomedicals (Solon, Ohio). Cell culture reagents were purchased from Mediatech Inc. (Manassas, VA) and Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. (Pittsburgh, PA).

Cell culture

The rat hepatic stellate cell line (HSC-T6) and spontaneously immortalized human hepatic stellate cell line (LX-2) were kindly provided by Dr. Scott L. Friedman (Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York University). HSC-T6 cells were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. LX-2 cells were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 2% FBS, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. The cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Screening of aptamers using SELEX

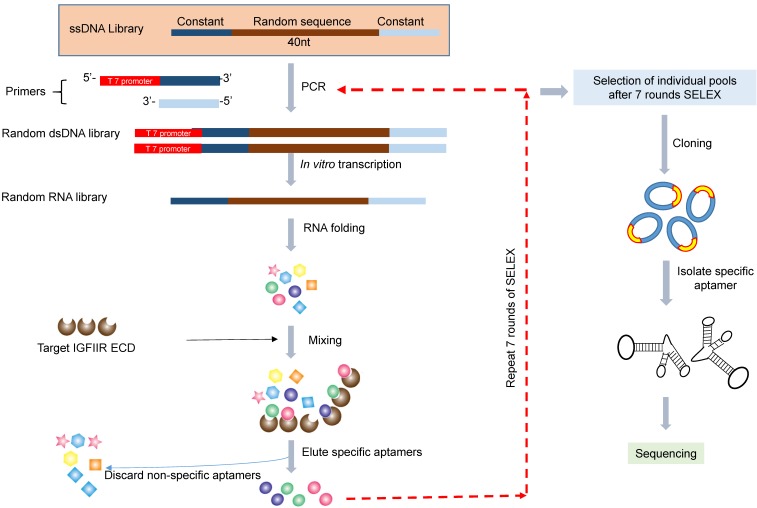

The in vitro SELEX was performed as previously reported (Figure 1) 22. The single-stranded DNA library was amplified by PCR using Taq-polymerase with a forward primer containing the T7 promoter (underlined): 5'-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG-AGAGTGCTGTTACTATCG-3' and a reverse primer 5'-ATACCACCTTGTTCAGTT-3'. The PCR product was transcribed into RNA for binding selection using a T7 transcription kit (MAXI script Kit). For the in vitro SELEX, 150 µL of nickel magnetic bead suspension was suspended in 1 mL of PBST (PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20), and the supernatant was removed after magnetic concentration. Recombinant human IGFIIR extracellular domain with His-tag was absorbed on the magnetic beads by incubation 100 µL of 100 µg/mL of protein at room temperature for 30 min with gentle rotation. Prior to incubation with IGFIIR protein, the RNA aptamer library was incubated with 1 mg of BSA, which was coated on a 24-well plate in a pH 7.4 bicarbonate buffer for 1 h to remove non-specific binding aptamers. The BSA-adsorbed aptamers were then incubated with the IGFIIR protein at room temperature for 1 h, followed by washing three times with 1 mL of PBST. The aptamers were then eluted by 100 µL of elution buffer (20 mM Tris, 500 mM imidazole pH 7.5) for 30 min and extracted with phenol-chloroform. After precipitation with ethanol and washing with 70% ethanol, the aptamers were dissolved in RNase-free water and subjected to RT-PCR for the next round selection.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the RNA aptamer selection using SELEX. A random ssDNA library consisting of a 40nt randomized sequence flanked on both sides by forward and reverse primers was used in SELEX. The ssDNA library was converted to dsDNA using PCR and then transcribed to RNA using T7 polymerase. The randomized RNA library was pre-incubated with BSA to remove non-specific binding aptamers and then incubated with IGFIIR, which was immobilized on magnetic beads. IGFIIR-bound RNA were eluted, reversely transcribed to cDNA and then amplified by PCR.

After seven rounds of selection, dsDNA was amplified by PCR, clone into the pCR™2.1-TOPO® vector, and transformed into TOP10 Escherichia coli (E. coli) cells. Thirty-three white colonies were randomly selected and sent to the sequencing core facility at the University of Missouri- Kansas City for DNA sequencing. The sequences were analyzed using the ClustaIW Multiple Sequence Alignment program at http://clustalw.ddbj.nig.ac.jp.

Serum stability of the DNA and RNA aptamers

Five µL of aptamers (10 µM) were mixed with 5 µL of rat serum or human serum and incubated at 37oC for 0, 5, 30 and 60 min. After incubation, the samples were mixed with DNA loading dye and subjected to gel electrophoresis at 4oC for 4 h at 80 V. The gel was stained with GelRed™ (Biotium, Fremont, CA) at room temperature for 20 min and then visualized under UV light.

Binding affinity of the aptamers to hepatic stellate cells

Two aptamers (aptamer 6 and aptamer 9), which showed more similar sequences with other aptamers in the SELEX, were selected for the affinity assay. A sticky bridge sequence (5'-CACAAGGAACAAGG-3') was added to the aptamers either at 5' or at 3' end. A complementary sequence labeled with Alexa-488 (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) was annealed with the sticky bridge of the aptamer. Binding affinities of these aptamers to HSC-T6 cells were determined as previously reported 8. Briefly, the cells were detached using non-enzymatic cell dissociation solution and re-suspended in Opti-MEM medium. Alexa-488 labeled aptamers (100 nM) were incubated with HSC-T6 cells at 37 oC for 1 h with gentle rotation. The cells were washed three times with PBS and then subjected to fluorescence analysis on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) using an excitation wavelength of 488 nm with a 535 nm emission filter. Cellular uptake of other aptamers was also determined in rat HSC-T6 cells using flow cytometry. The apparent Kd value of aptamers that exhibited high binding affinity to HSC-T6 cells were determined in LX-2 and HSC-T6 cells. The results were calculated by non-linear fit in Graphpad Prism.

Surface plasmon resonance

The binding affinity Kd value of aptamer-20 was determined by Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) using a Biacore X biosensor system according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 5 µg of the recombinant human IGFIIR extracellular domain protein was coated on a CM5 chip using an amine coupling kit. Aptamer-20 (30 µL) was injected into the Biacore X at serial concentrations of 1, 10, 100, 1000 and 10000 nM. The binding data were analyzed using the BIA evaluation program.

Specificity of the aptamer-20 with IGFIIR

The human hepatic stellate LX-2 cells were seeded in a 6-well plate at 200,000 cells/well 16 h before transfection. The cells were transfected with 50 nM IGFIIR siRNA or a scrambled siRNA using Lipofectamine® RNAiMAX for 48 h. The cells were detached using a nonenzymatic cell dissociation solution and resuspended in Opti-MEM. Aptamer-20 (100 nM) was incubated with the suspended cells at 37℃ for 1 h with gentle rotation. The labeled cells were analyzed by flow cytometry as described above.

Fabrication of siRNA-aptamer chimera

The PCBP2 siRNA sense strand containing a 3'-sticky bridge sequence 5'-CACAAGGAACAAGG-3' was annealed with the PCBP2 siRNA antisense strand (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) by maintaining the mixture at 95℃ for 5 min and then cooling down to 48℃ for 10 min. After cooling to 38℃, aptamer-20 with a complementary sticky bridge was mixed with the formed PCBP2 siRNA duplex and then maintained for 10 min to form the siRNA-aptamer chimera. A band shift assay in non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel (20%) electrophoresis was used to confirm the annealing.

Serum stability of the siRNA-aptamer chimera

Unmodified siRNA, siRNA with a 3'-sticky bridge, and the siRNA-aptamer chimera were incubated with Opti-MEM medium or 50% rat serum for 0, 5, 30, 60, 180, and 360 min at 37℃ with gentle shaking. After each time point, samples were taken and stored at -80℃ until they were analyzed by electrophoresis.

Silencing activity of the siRNA-aptamer chimera

HSCs were seeded on 24-well plates at 30,000 cells/well 16 h before transfection. Scrambled siRNA, siRNA with 3' sticky bridge, and siRNA-aptamer chimera were transfected with or without Lipofectamine® RNAIMAX as previously reported 8. The silencing activities at the mRNA and protein levels were determined using real-time RT-PCR and western blot, respectively.

For real-time RT-PCR assay, total RNA was isolated using Direct-zolTM RNA isolation kit (ZYMO RESEARCH, Irvine, CA). Real-time PCR was performed using the iTaq universal SYBR Green one-step kit (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA). The primers used for the study were as follows: PCBP2 5'-ACCAATAGCACAGCTGCCAGTAGA-3' (forward primer) and 5'-AGTCTCCAACATG ACCACGCAGAT-3' (reverse primer). 18s rRNA was used as an internal control, and the primers were 5′-GTCTGTGATGCCCTTAGATG-3′ (forward primer) and 5'-AGCTTATGACCCGCACTTAC-3' (reverse primer).

For western blot, the cells were lysed using RIPA buffer for 10 min on ice. The lysates were centrifuged at 12000g for 20 min at 4℃. Supernatant was collected, and the total protein concentration was determined using BCA assay. Equal amount of protein (20 µg) were resolved on a 6% non-reduction SDS-PAGE gel. After electrophoresis, the separated proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane using wet transfer method overnight at 4℃ with 30V. The membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat milk at 4℃ for 12 h and probed with anti-PCBP2 antibody (GWB-3815A, GenWay Biotech) overnight at 4oC. The protein band was then visualized using horseradish peroxidase conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) after incubation with the Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (MILLIPORE, Billerica, MA). The same membrane was probed with anti-β-actin antibody as an internal control.

Backbone modification of the sense strand of the PCBP2 siRNA

To improve the serum stability of PCBP2 siRNA, 2'-OMe-modified siRNA sense strand was annealed with an antisense strand. The siRNA duplex was then incubated with 10% FBS for 0, 1, 3, 6 and 12 h, or with rat serum for 0, 5, 30 and 60 min at 37℃. All samples were subjected to electrophoresis at 4℃ for 4 h. The 2'-OMe-modified sense strands of the PCBP2 siRNA are listed below.

PCBP2-0 sense strand: GUC AGU GUG GCU CUC UUA UdTdT

PCBP2-1 sense strand: mGmUmC AGU GUG GCU CUC UUA UdTdT

PCBP2-2 sense strand: mGmUC AGU GUG GCU CUC UUA UdTdT

PCBP2-3 sense strand: mGUC AGU GUG GCU CUC UUA UdTdT

PCBP2-4 sense strand: GUC AGU GUG GCU CUC UmUmA mUdTdT

PCBP2 antisense strand: AUA AGA GAG CCA CAC UGA CdTdT

The optimized sense strand was elongated by adding a sticky bridge as described above and then annealed with an antisense strand and aptamer-20 to form a siRNA duplex or siRNA-aptamer chimera. Serum stability of the siRNA duplex and chimera was determined in rat serum at 37℃ for 0, 5, 30 and 60 min.

Biodistribution study

The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. Male Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Charles Rivers Laboratories (Wilmington, Massachusetts) and housed in a temperature and humidity controlled room with a 12h light-dark cycle.

Liver fibrosis was induced by intraperitoneal injections of equal amounts of CCl4 and an olive oil mixture (1 µL of CCl4 per gram of body weight) every three days for one month. Six rats were randomized into 2 groups (a siRNA duplex group and a siRNA-aptamer chimera group). The antisense strand of the siRNA was labeled with Alexa-647. Two nmol of the siRNA duplex and siRNA-aptamer chimera were injected into rats via the tail vein. After 1 h, the rats were sacrificed, and the organs were collected and subjected to image analysis using a BRUKER In-Viva MS FX PRO system (Billerica, MA) with 10 sec of exposure time, 4x4 pixels, and using a 600 nm excitation wavelength with a 700 nm emission filter.

Results

In vitro SELEX

The purpose of this project was to identify aptamer ligands for hepatic stellate cells. In Vitro SELEX (Figure 1) was performed to identify aptamers that bind to the IGFIIR protein, which is overexpressed in activated HSCs 23. To reduce the non-specific binding of the selected aptamers, we included an adsorption step with BSA to remove those nonspecific aptamers in the library. The single-stranded RNA aptamer library (19,544 ng) was then incubated with the IGFIIR-bound magnetic beads for 1 h. After removing the unbound aptamers, the bound aptamers were eluted and purified.

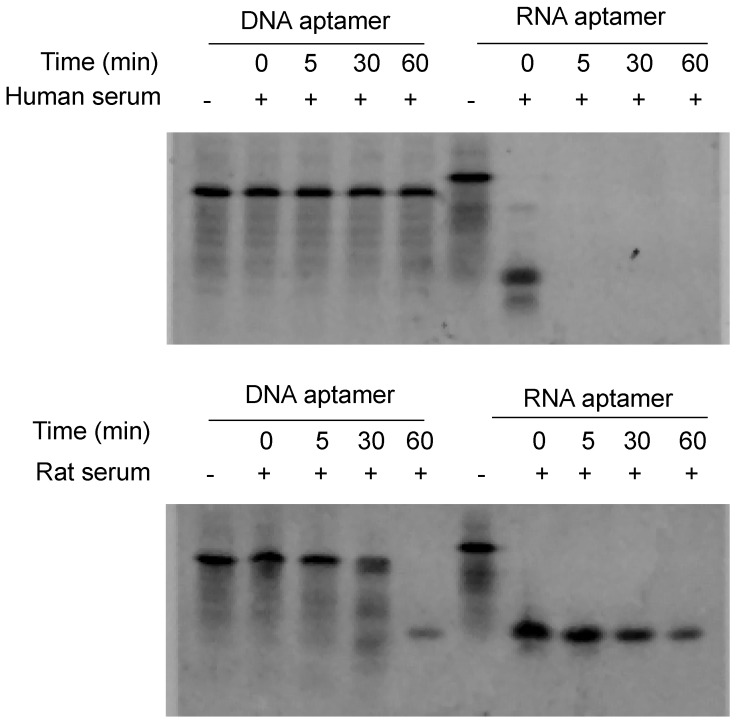

Serum stability of DNA aptamer and RNA aptamer

Serum stability is always a concern for the application of nucleic acid-based molecules, including DNA and RNA aptamers. We therefore compared the stability of the RNA- and DNA-based aptamer-20. As illustrated in Figure 2, serum stability of the DNA aptamer is much better than the RNA aptamer. The RNA aptamer was rapidly degraded after incubation with rat and human serum. By comparison, the DNA aptamer was stable for 60 and 30 min in human and rat serum, respectively. We therefore used DNA aptamers for subsequent studies despite that RNA aptamers, in general, have higher affinity than their corresponding DNA aptamers.

Figure 2.

Serum stability of the DNA and RNA aptamers. Five µL of DNA and RNA aptamers (10 µM) were incubated with equal volume of serum at 37℃ for 0, 5, 30 and 60 min. The samples were subjected to 20% native PAGE electrophoresis at 4℃ for 4 hours.

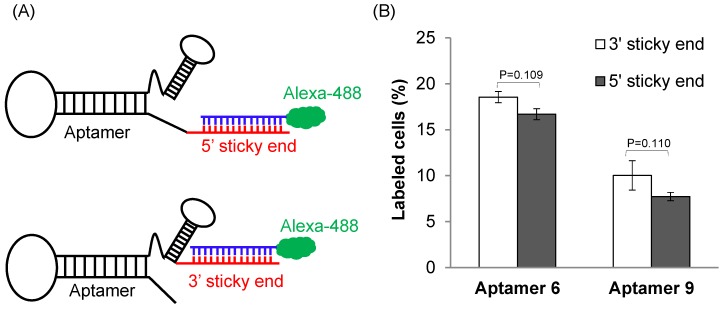

Binding affinity assay

We next evaluated the binding affinity of the identified 29 aptamers. To track the uptake of the aptamers using flow cytometry, we added a 14-nucleotide sticky bridge (5'-CACAAGGAACAAGG-3') to the aptamers and then annealed them with a complementary Alexa-488 labeled DNA oligonucleotide. We first evaluated whether the site (5' or 3' end) of annealing affects the affinity of the aptamers. Aptamer 6 and 9 were selected for this study because they showed more similar sequences with the rest aptamers. Alexa-488 labeled DNA was annealed to the aptamers either at 5' or at 3' end (Figure 3A). Cellular uptake results indicated that there is minor difference for the binding affinity between the 3'- and 5'-labeled aptamers (Figure 3B, p=0.11). Considering the fact that the 3' end of nucleic acids is more vulnerable to degradation by nucleases and modification of the 3' end of aptamers increases serum stability 24, the 14-mer sticky bridge sequence was added to the 3' end of the identified aptamers to enhance its stability.

Figure 3.

The effect of annealing site on the binding affinity of the DNA aptamers. (A) A 14-mer Alexa-488 labeled oligonucleotide was annealed with the DNA aptamers containing a complementary sequence at 5' or 3' end. (B) Cellular uptake of the aptamers annealed with the Alexa-488 labeled oligonucleotide. The aptamers were incubated with HSC-T6 cells at 37℃ for 1 h, and labeled cells were counted using flow cytometry. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n=3).

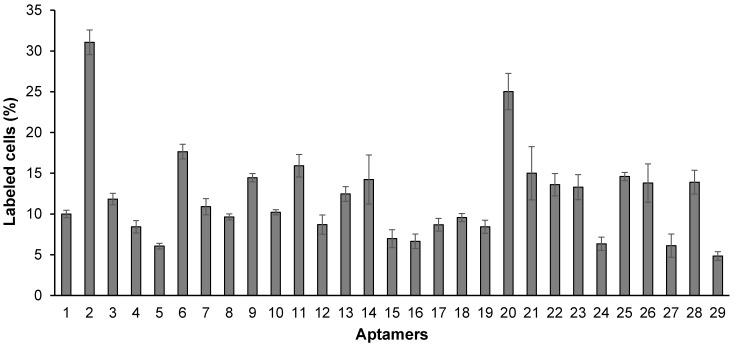

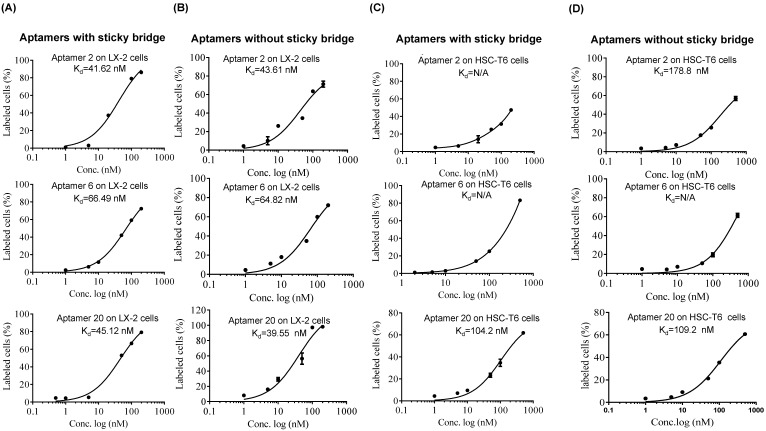

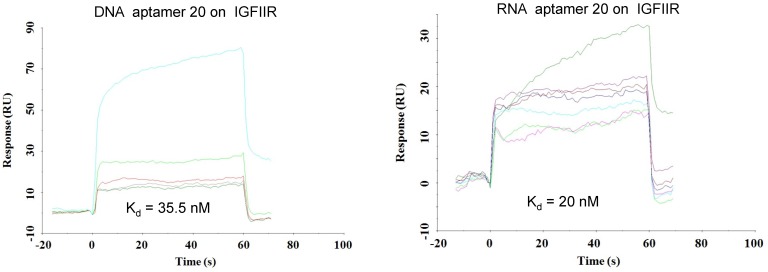

As shown in Figure 4, all of the identified aptamers exhibited high binding affinity with HSC-T6 rat hepatic stellate cells when incubated at a concentration of 100 nM. Among these aptamers, the aptamers 2, 6 and 20 showed the highest binding affinity for HSC-T6 cells. Subsequently, the apparent binding affinity (Kd) of aptamers 2, 6 and 20 were determined with LX-2 and HSC-T6 cells using a saturation binding assay. Aptamer-20 showed the highest binding affinity with an apparent Kd of 45.12 nM for LX-2 cells and 104.2 nM for HSC-T6 cells when aptamer-20 was annealed with a dye-labeled sticky bridge (Figure 5A). Aptamer-20 labeled with a dye showed similar apparent Kd of 39.55 nM for LX-2 cells and 109.2 nM for HSC-T6 cells (Figure 5B and D). This result suggested that the addition of a sticky bridge to the aptamer does not comprising its affinity to IGFIIR. The relatively low affinity of aptamer-20 to HSC-T6 cells is possibly due to the fact that the aptamers were screened against human IGFIIR protein. The Kd values of aptamer-20 with IGFIIR protein was also determined by Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) using a Biacore X instrument according to the manufacturer's instructions (Figure 6). The Kd values of the DNA aptamer-20 and its corresponding RNA aptamer-20 are 35.5 nM and 20 nM, respectively (Figure 6). Although the binding affinity of the RNA aptamer-20 is slightly higher than that of the DNA aptamer-20, serum stability of the DNA aptamer is much better, and we therefore used the DNA aptamer-20 for subsequent studies.

Figure 4.

Binding affinity of the 29 randomly selected aptamers to HSC-T6 cells. The aptamers were annealed at the 3' end with a complementary oligonucleotide labeled with Alexa Fluor®-488. The aptamers were incubated with HSC-T6 cells at 37℃ for 1 h, and labeled cells were counted using flow cytometry. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n=3).

Figure 5.

Equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) of select aptamers in LX-2 and HSC. Apparent Kd values of the DNA aptamers annealed with Alexa-488 labeled oligonucleotides in LX-2 (A) and HSC-T6 (C) cells. Apparent Kd values of the DNA aptamers labeled Alexa-488 in LX-2 (B) and HSC-T6 (D). The cells were incubated with the aptamers at different concentrations at 37℃ for 1 h. The labeled cells were determined using flow cytometry, and apparent Kd values were calculated using GraphPad.

Figure 6.

Equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) of select aptamers on human IGFIIR IGFIIR extracellular domain protein. Kd values of the DNA and RNA aptamer-20 on recombinant human IGFIIR extracellular domain protein were determined by SPR using Biacore X. The binding data was analyzed using a BIA evaluation program. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n=3).

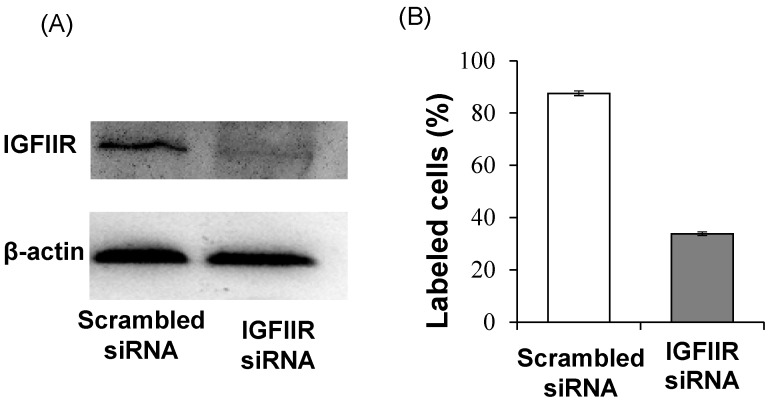

Specificity of the DNA aptamer-20 to IGFIIR

In addition to affinity, specificity of the DNA aptamer-20 for IGFIIR was also evaluated in LX-2 cells. We have previously demonstrated that the expression of IGFIIR in LX-2 cells can be knocked down by an IGFIIR siRNA 8. Accordingly, LX-2 cells were transfected with 50 nM IGFIIR siRNA for 48 h. As shown in Figure 7A, IGFIIR was almost completely downregulated by the siRNA. As a result, the cellular uptake of the DNA aptamer-20 was significantly decreased from 87% to 33% in LX-2 cells treated with the IGFIIR siRNA (Figure 7B). This result confirmed that the high cellular uptake of the DNA aptamer-20 in LX-2 cells was mediated by IGFIIR protein on the cell surface.

Figure 7.

Knockdown of IGFIIR decreases the affinity of aptamer-20 to LX-2 cells. LX-2 cells were transfected with 50 nM of scramble siRNA or IGFIIR siRNA for 48 h. The expression of IGFIIR was determined by western blot (A). After knockdown of IGFIIR, the cells were incubated with aptamer-20 at 37℃ for 1 h, and the labeled cells were counted using flow cytometry (B). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n=3).

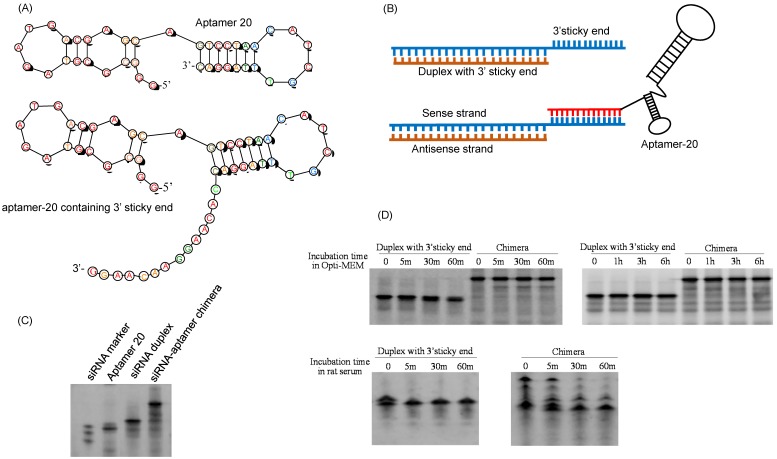

Fabrication of siRNA-DNA chimera

We recently discovered a PCBP2 siRNA that can be potentially used for the treatment of liver fibrosis 25, 26. However, lack of an efficient system to deliver siRNA to hepatic stellate cells still remains a major challenge. We therefore examined whether the DNA aptamer-20 can be used to deliver PCBP2 siRNA to HSCs by forming a siRNA-DNA chimera. As described above and illustrated in Figure 8A, the 14-nucleotide sticky bridge 5'-CACAAGGAACAAGG-3' was added to the 3' end of the aptamer. Accordingly, a complementary sequence of the stick end was added to the 3' end of the sense strand of the siRNA (Figure 8B). The aptamer and the siRNA were then annealed to form the siRNA-aptamer chimera. Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis demonstrated that the siRNA forms a stable chimera with aptamer-20 (Figure 8C).

Figure 8.

Fabrication of the siRNA-aptamer chimera. (A) Schematic of the DNA aptamer-20 with a 14-mer sticky bridge. (B) Schematic of the siRNA-aptamer chimera. The sense strand of the PCBP2 siRNA containing a 3' sticky bridge which is complementary with the sticky bridge of aptamer-20. (C) Annealing of the siRNA-aptamer chimera was confirmed by native PAGE analysis. (D) Stability of the siRNA duplex and siRNA-aptamer chimera in Opti-MEM medium and rat serum.

Serum stability of the siRNA-aptamer chimera

Serum stability of the siRNA-aptamer chimera was then evaluated in Opti-MEM reduced-serum medium and 50% rat serum. Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis indicated that the siRNA duplex containing the sticky bridge was stable in Opti-MEM medium but rapidly degraded in rat serum. By comparison, the siRNA-aptamer chimera was relatively stable in rat serum (Figure 8D). This is mainly because that annealing of the aptamer at the 3' end of the siRNA inhibited 3'-exonuclease-mediated degradation.

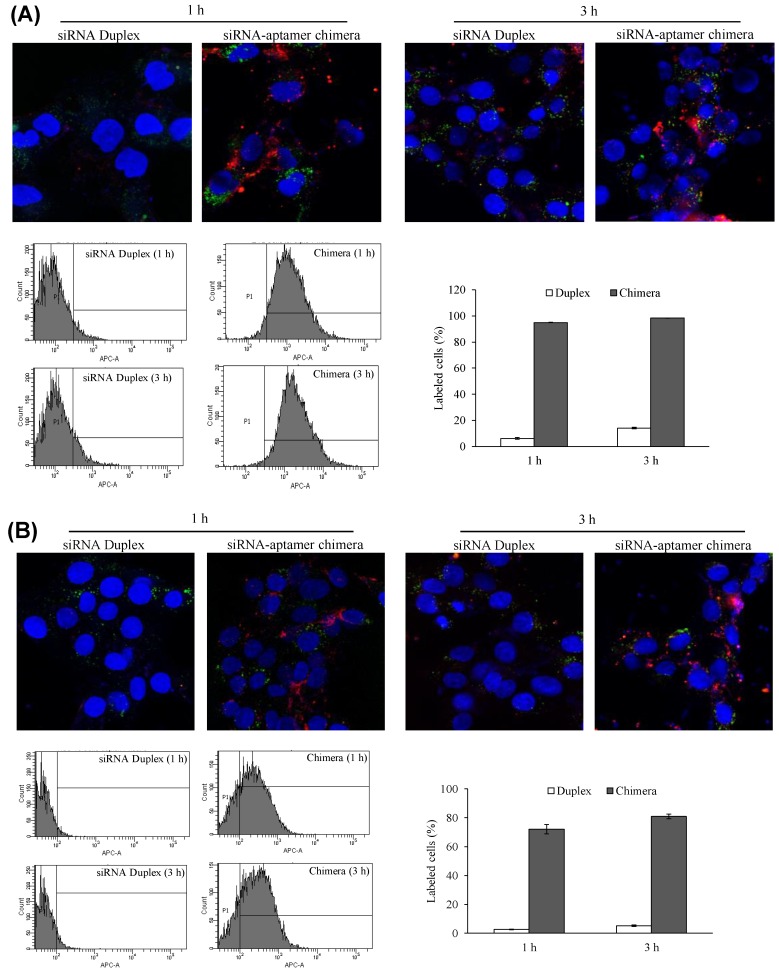

Cellular uptake of the siRNA-aptamer chimera in hepatic stellate cells

Cellular uptake of the siRNA-aptamer chimera in human LX-2 and rat HSC-T6 cells was studied using confocal microscopy and flow cytometry. The antisense strand of the siRNA was labeled with a cellular tracking dye Alexa-647 (red). Lyso Tracker® (green) and DAPI (blue) were used to label the lysosome and nucleus, respectively. The siRNA-aptamer chimera showed dramatically higher cellular uptake compared to the siRNA duplex in human LX-2 hepatic stellate cells (Figure 9A). Similar results were also observed in HSC-T6 cells (Figure 9B). These results clearly demonstrated that aptamer-20 can form a chimera with the PCBP2 siRNA and deliver it into HSCs. Moreover, the uptake of the siRNA-aptamer was higher in LX-2 cells than in HSC-T6 cells. This is consistent with the finding in Figure 5A, which showed a higher affinity of the aptamer to human LX-2 cells than to rat HSC-T6 cells.

Figure 9.

Cellular uptake of the siRNA-aptamer chimera in LX-2 (A) and HSC-T6 (B) cells. The siRNA-aptamer chimera and siRNA duplex were incubated with the cells for 1 and 3 h. Cellular uptake was determined using confocal microscopy and flow cytometry. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n=3).

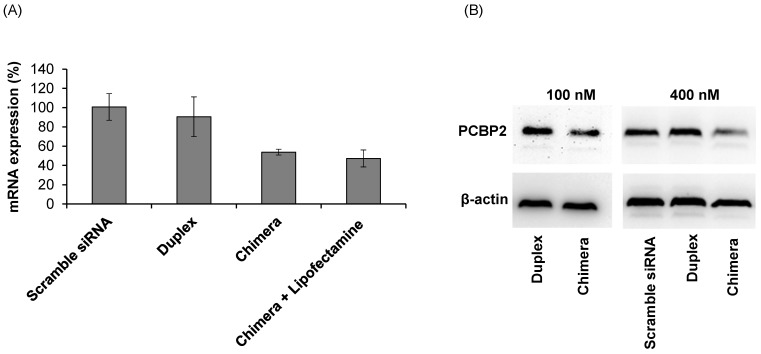

Silencing activity of the siRNA-aptamer chimera

The purpose of this project was to identify an IGFIIR-specific aptamer that can be used to deliver therapeutic agents, such as siRNA, into hepatic stellate cells for the treatment of liver fibrosis. Therefore, the silencing activity of the PCBP2 siRNA-aptamer chimera was determined in HSC-T6 rat hepatic stellate cells. As shown in Figure 10A, the siRNA duplex itself cannot enter the cells and induce silencing activity, but the siRNA-aptamer chimera (100 nM) exhibited a significant silencing effect, which is consistent with the cellular uptake results in Figure 9. The result showed 50% silencing activity on PCBP2 mRNA, which is comparable to the silencing activity of a similar siRNA-aptamer chimera developed by Dr. Rossi 21. We also evaluated whether Lipofectamine can further improve the silencing activity of the siRNA-aptamer chimera, but it showed similar activity as the siRNA-aptamer chimera alone, suggesting a very efficient cellular uptake of the siRNA-aptamer chimera itself. Western blot result confirmed the silencing activity of the siRNA-aptamer chimera in hepatic stellate cells (Figure 10B). In the future, we may use chemically modified siRNA to increase the activity of the siRNA-aptamer chimera.

Figure 10.

Silencing activity of the siRNA-aptamer chimera and siRNA duplex. The siRNA-aptamer chimera and siRNA duplex (100 nM) were incubated with LX-2 cells for 24 h, and the silencing activity at the mRNA level was determined by real time RT-PCR (A). Silencing activity at the protein level was determined using western blot 48 h post-transfection (B). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n=3).

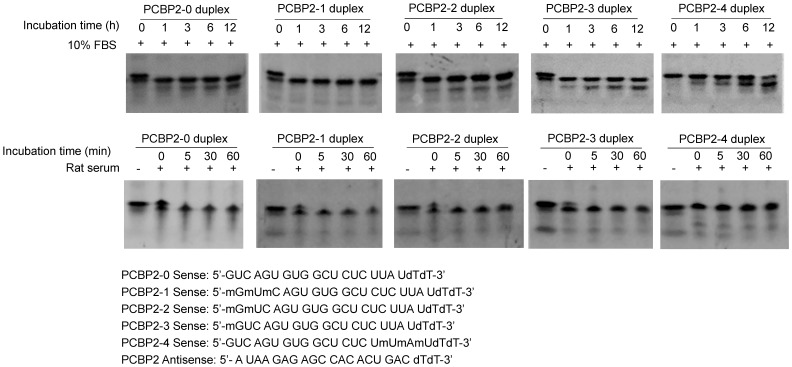

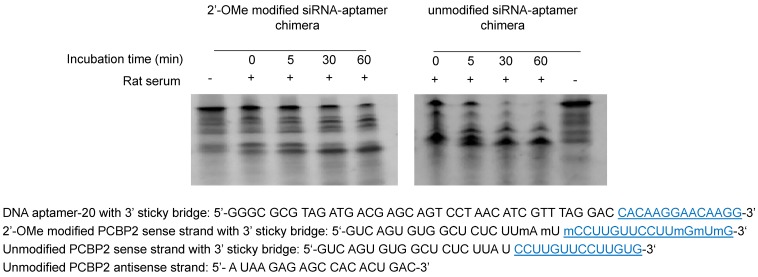

Serum stability of backbone modified PCBP2 siRNA and siRNA-aptamer chimera

To develop a serum-stable aptamer-siRNA chimera for in vivo studies, 2'-OMe backbone modifications were introduced to the sense strand of the siRNA at different positions (Figure 11). Serum stability of the siRNA duplex and the aptamer-siRNA chimera were evaluated in FBS and rat serum. As illustrated in Figure 11, position of the 2'-OMe modification is critical for the serum stability of the siRNA duplex. 2'-OMe modification at the 3' end of the siRNA sense strand (PCBP2-4) exhibited the best stability in 10% FBS and in 50% rat serum. The number of 2'-OMe groups affects the stability of the 5' modification. Three 2'-OMe modifications at the 5' end of the sense strand (PCBP2-1) showed better stability than one 2'-OMe modification (PCBP2-3). Afterwards, we modified the 3' end of the siRNA sense strand containing the sticky bridge (Figure 12) and form a siRNA-aptamer chimera. Compared to the unmodified siRNA-aptamer chimera, the chimera containing the 2'-OMe modification demonstrated much better serum stability. We therefore used this siRNA-aptamer chimera for the subsequent biodistribution study.

Figure 11.

Serum stability of the backbone modified PCBP2 siRNA duplex. The sense strand of the PCBP2 siRNA was modified with 2'-OMe at different positions. The sense strand was annealed with the unmodified antisense strand and incubated with 10% FBS and rat serum for various time intervals, followed by electrophoresis analysis.

Figure 12.

Serum stability of the siRNA-aptamer chimera containing 2'-OMe modification. 2'-OMe modified sense strand of the PCPB2 siRNA was annealed with the antisense strand and then form the chimera with the DNA aptamer-20. The siRNA-aptamer chimera was incubated in rat serum for various time intervals and subjected for electrophoresis with 20% native PAGE.

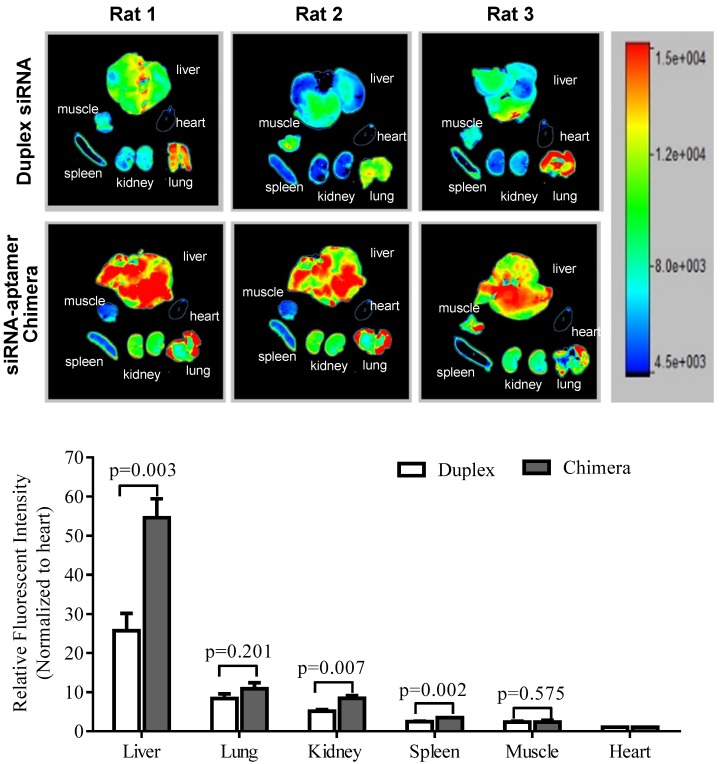

Biodistribution study

It is known that liver fibrosis results in extensive accumulation of collagen and dramatic changes in sinusoids and space of Disse in the liver, which reduce the hepatic uptake of therapeutic agents 3, 27, 28. Therefore, it is critical to study the biodistribution of the siRNA-aptamer chimera in rats with CCl4-induced liver fibrosis. The antisense strand of the siRNA was labeled with Alexa Fluor-647 to track the chimera in the rats. One hour after systemic injection via the tail vein, the rats were sacrificed, and the major organs were collected for examination using a small animal imaging system (Figure 13). Regardless of the high accumulation of scar in the fibrotic liver, the siRNA-aptamer chimera was primarily located in the liver compared to other organs. More importantly, the siRNA-aptamer chimera showed a 2.1-fold higher uptake in the liver compared to the duplex siRNA, suggesting that that the IGFIIR-specific aptamer-20 is able to efficiently deliver its cargo to fibrotic liver in vivo.

Figure 13.

Biodistribution of the PCBP2 siRNA-aptamer chimera in rats with CCl4-induced liver fibrosis. The antisense strand of the PCBP2 siRNA was labeled with Alexa-647. Two nmols of the siRNA-aptamer chimera were injected into the rats via the tail vein. After 1h, the rats were sacrificed, and major organs were harvested for imaging analysis using a BRUKER In-Vivo MS FX PRO system. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n=3).

Discussion

Because of the accumulation of collagen and decreased fenestration in fibrotic liver, hepatic uptake of therapeutic agents is always low in fibrotic liver. Moreover, hepatic stellate cells, which are the major cells responsible for liver fibrogenesis, only accounts for approximately 7% of the liver cells 3, 28. Therefore, development of a targeted delivery system to hepatic stellate cells is essential to the success of antifibrotic therapy. IGFIIR is overexpressed in activated hepatic stellate cells and can be used as a targeting moiety for liver fibrosis. We have previously discovered several IGFIIR-specific peptides, but their apparent Kd values are in the range of 700 nM to 6 µM. In addition, the peptide cannot be linked to siRNA without chemical conjugation, which may limit its future applications for antifibrotic siRNA. We therefore aim to identify an IGFIIR-specific aptamer, which has a higher affinity and can easily form a chimera with siRNA via strand hybridization at the 3' end of the aptamer.

IGFIIR protein is composed of an extracellular region, a transmembrane region, and an intracellular region. The extracellular region contains 15 homologous repeat domains which include the IGFII-binding domain 11 and M6P-binding domains 3 and 9. The major function of IGFIIR is to regulate the serum level of IGFII and the intracellular trafficking of M6P bearing molecules, such as lysosomal enzymes 29. The recombinant human IGFIIR protein used in this study is the extracellular region containing the domains 10 to 14. The aptamer will therefore not interfere with the interaction between IGFIIR and M6P. There is a possibility that the IGFIIR-specific aptamer may interference with the binding of IGFII to IGFIIR. However, the binding affinity of IGFII with IGFIIR is about 100 pM, which is much higher than that of the aptamer, suggesting that the aptamer is unlikely to affect the regulation of IGFII by IGFIIR 30.

SELEX can be used to screen aptamers against targeting proteins 31, cells 32, specimen 33, or organs 34. In this project, a protein-based SELEX was performed to identify IGFIIR-specific RNA aptamers, and the selected aptamers were converted to DNA aptamers because of the high cost and poor serum stability of RNA aptamers 35. The half-life of unmodified RNA is about few seconds in plasma 36, while the half-life of DNA is approximately 30-60 min. Our results (Figure 2) demonstrated that the half-life of DNA aptamer-20 is approximately 30 min in rat serum but is greater than 60 min in human serum. By contrast, unmodified RNA aptamer-20 is highly unstable in both rat and human serum, which is consistent with a previous report 36. Several chemical modifications, such as 2'-amino pyrimidines, 2'-O-methyl ribose purines, and 2'-fluoro pyrimidines have been developed to improve the serum stability of DNA and RNA aptamers 37. By comparison, the unmodified DNA aptamer-20 exhibits similar affinity to IGFIIR and HSCs as the RNA aptamer-20 (Figure 5). In another study, DNA aptamers were also successfully generated by conversion from RNA aptamers without comprising its binding affinity 38. The obtained DNA aptamer can efficiently deliver an siRNA into CD4+ T cells 38. In general, the Kd value of aptamers identified by SELEX are in the range from pM to mM 39. In our study, the Kd of the DNA aptamer-20 is approximately 35.5 nM for IGFIIR protein and is comparable to other aptamers 40. Moreover, the DNA aptamer-20 exhibits high affinity to LX-2 human hepatic stellate cells (apparent Kd=45.12 nM) and to HSC-T6 rat hepatic stellate cells (apparent Kd=104.2 nM) (Figure 5). Therefore, the aptamer can be potentially used for rats in preclinical studies and human patients in future clinical studies because of its high affinity to human hepatic stellate cells.

We have previously discovered a siRNA targeting the poly(rC) binding protein 2 (PCBP2) gene, which can destabilize the accumulated collagen type-1(I) mRNA in activated HSCs 26. The key remaining challenge for RNAi therapy is how to deliver siRNA to the target cells. Nanoparticles, cation lipid, cation polymers and other novel delivery systems such as avidin-biotin complex have been studied for siRNA delivery 25, 41-43. Among them, siRNA conjugate is a promising approach and some of them are evaluated in clinical trials. For example, the GalNAc-siRNA conjugate developed by Alnylam Pharmaceuticals has entered a Phase III clinical trial 44. However, chemical conjugation of siRNAs is always difficult because of their poor stability 45, 46. By contrast, aptamers can easily form a chimera with siRNA by annealing. The first aptamer-siRNA chimera was reported in 2006 to link a PSMA-specific aptamer to a therapeutic siRNA. The aptamer-siRNA was successfully delivered to PSMA-positive prostate cancer cells but not the PSMA-negative cells 20. Moreover, a sticky bridge was applied to link aptamers with anti-HIV siRNA for siRNA targeted delivery. The silencing activity of the aptamer-siRNA chimera was in the range of 55% to 85% at the concentration of 400 nM of siRNA 21. In this study, we annealed the siRNA with aptamer-20 by adding a sticky bridge to each of them. The siRNA-aptamer chimera was efficiently taken up by LX-2 and HSC-T6 cells. Approximately 50% of the PCBP2 gene expression was suppressed after transfection of the siRNA-aptamer without using Lipofectamine® RNAiMAX (Figure 10), indicating that the aptamer can mediate cellular internalization of the siRNA and trigger the silencing activity. Compared to the silencing activity of free PCBP2 siRNA which was transfected by Lipofectomine® with HSC-T6 cells, the siRNA-aptamer chimera showed slightly decreased activity (from 65% to 50%) at the concentration of 100 nM siRNA 26.

In summary, we discovered an IGFIIR-specific aptamer and demonstrated its high affinity and specificity to human and rat hepatic stellate cells. The aptamer can form a stable chimera with the PCBP2 siRNA and deliver them to HSCs to induce the silencing activity. The siRNA-aptamer chimera also exhibited high hepatic uptake in rat with CCl4-induced liver fibrosis, indicating its great potential as a targeting ligand for antifibrotic therapeutics and imaging agents.

Table 1.

Sequences of randomly selected aptamers after seven rounds of SELEX. Twenty-nine sequences were identified from thirty-three randomly selected clones.

| Sample ID | Aptamer Sequence |

|---|---|

| 1 | GTGGTAGATTTCGCTACTTCCGTTGTGTGCGTCACGGTGGG |

| 2 | GGGGAGGCGATTCGGTGTGTCCTCCAGAAGATATTTCCGA |

| 3 | TGCCCGCTCATGGACAAGTGTTATTCGACTCCGCCGCCCC |

| 4 | CCTACAATTTCCTGAAACCCATCTCAGCCC |

| 5 | GACGCGGATCGAAGTTAGCGGGCGTTTGCCAGTAGAAGAT |

| 6 | CGGGCACGGATGGAGTCGTTGCAGGGGCCCTTCCCCTTGG |

| 7 | CCATTCCACACTTGTAGGGCCCCTCTCGCCGCACCATTTGG |

| 8 | CCGGGAGCGTAACTTAGGCTCAATCACTACATATACCTCA |

| 9 | CCGACCGTGACCAGACAAACGTTTGAGTAGGCGCCCGACA |

| 10 | CGCGGGAACTATAGTAGCACAGTTCGCATCGAGAGGGTCT |

| 11 | ATGCCGGATTCCGTTCATGGTGACTCTACCCCGGGCGCCG |

| 12 | CGGCGAGACATGGAGTTCACCAAGGGCGTGGTCTTGTGCT |

| 13 | CGAATGCGTGTTTTCCAATCGGCACTCTTCCTAGCCCCGG |

| 14 | CCTCTGTCTATTAATCCTCTTATTTCGCTCCGGGCCCC |

| 15 | CGCGCCAGTTGACGAGCAATGACCGACGACAAGTTCACGT |

| 16 | CGCCAGATTGCCTTGAAACCAATTAGTTCCGAAGGACTAC |

| 17 | GTTCATTTGGACCTGTATAGCCTGGCCCCCTTGTCTTCGC |

| 18 | TTCAACCGAATACCAAAATTGTATTGCTTGTGTAATGCC |

| 19 | CGAGGTGATGAGGACCGCGTTCTTGGTGTAACCTCTGCCG |

| 20 | GGGCGCGTAGATGACGAGCAGTCCTAACATCGTTTAGGAC |

| 21 | TATTTTTTGCTTCTTTCAACCACTTCAGGTGAAAGCCCGG |

| 22 | CTAGCCCAACAAGAACTTGCCTTCGATTACGTGGGGATGG |

| 23 | CTTGCGCAACTAACACCCGCATGCCTCGGATCCCATTCCT |

| 24 | TCGAGGACATCAGGGCAAGGATTTTCTACTCGTACCGCCG |

| 25 | ACGTACTCTCATCCCTTAACCTGTCGTAGCTCCAGGTCCG |

| 26 | CACGGGTTCGGCATTCTCGTCAATGATCAACAGGCGAATT |

| 27 | GGGGTGTCGAGCCAGCAATGAACGCGCCCAGTCGCAAAGA |

| 28 | CGCGAGAGAATGGTGGAGGACGATGCCAATGCGACCCTGC |

| 29 | CCACGCGACGCAATAGAGGAATAATATTACGACGGCCTTT |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an award (1R01AA021510) from the National Institutes of Health and a School of Graduate Studies Research Grant Award from the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

References

- 1.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V. et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095–128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellis EL, Mann DA. Clinical evidence for the regression of liver fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2012;56:1171–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng K, Mahato RI. Gene modulation for treating liver fibrosis. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 2007;24:93–146. doi: 10.1615/critrevtherdrugcarriersyst.v24.i2.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sato Y, Murase K, Kato J, Kobune M, Sato T, Kawano Y. et al. Resolution of liver cirrhosis using vitamin A-coupled liposomes to deliver siRNA against a collagen-specific chaperone. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:431–42. doi: 10.1038/nbt1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bansal R, Prakash J, de Ruijter M, Beljaars L, Poelstra K. Peptide-modified albumin carrier explored as a novel strategy for a cell-specific delivery of interferon gamma to treat liver fibrosis. Mol Pharm. 2011;8:1899–909. doi: 10.1021/mp200263q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morgan DO, Edman JC, Standring DN, Fried VA, Smith MC, Roth RA. et al. Insulin-like growth factor II receptor as a multifunctional binding protein. Nature. 1987;329:301–7. doi: 10.1038/329301a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gary-Bobo M, Nirde P, Jeanjean A, Morere A, Garcia M. Mannose 6-phosphate receptor targeting and its applications in human diseases. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:2945–53. doi: 10.2174/092986707782794005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Z, Jin W, Liu H, Zhao Z, Cheng K. Discovery of Peptide ligands for hepatic stellate cells using phage display. Mol Pharm. 2015;12:2180–8. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lao YH, Phua KK, Leong KW. Aptamer nanomedicine for cancer therapeutics: barriers and potential for translation. ACS Nano. 2015;9:2235–54. doi: 10.1021/nn507494p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu H, Li J, Zhang XB, Ye M, Tan W. Nucleic acid aptamer-mediated drug delivery for targeted cancer therapy. ChemMedChem. 2015;10:39–45. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201402312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiang D, Shigdar S, Qiao G, Wang T, Kouzani AZ, Zhou SF. et al. Nucleic acid aptamer-guided cancer therapeutics and diagnostics: the next generation of cancer medicine. Theranostics. 2015;5:23–42. doi: 10.7150/thno.10202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou J, Rossi J. Aptamers as targeted therapeutics: current potential and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov; 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bock LC, Griffin LC, Latham JA, Vermaas EH, Toole JJ. Selection of single-stranded DNA molecules that bind and inhibit human thrombin. Nature. 1992;355:564–6. doi: 10.1038/355564a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanwar JR, Shankaranarayanan JS, Gurudevan S, Kanwar RK. Aptamer-based therapeutics of the past, present and future: from the perspective of eye-related diseases. Drug Discov Today. 2014;19:1309–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ng EW, Shima DT, Calias P, Cunningham ET Jr, Guyer DR, Adamis AP. Pegaptanib, a targeted anti-VEGF aptamer for ocular vascular disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:123–32. doi: 10.1038/nrd1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drolet DW, Green LS, Gold L, Janjic N. Fit for the Eye: Aptamers in Ocular Disorders. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2016;26:127–46. doi: 10.1089/nat.2015.0573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou J, Rossi JJ. Cell-specific aptamer-mediated targeted drug delivery. Oligonucleotides. 2011;21:1–10. doi: 10.1089/oli.2010.0264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li X, Zhao Q, Qiu L. Smart ligand: aptamer-mediated targeted delivery of chemotherapeutic drugs and siRNA for cancer therapy. J Control Release. 2013;171:152–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu G, Niu G, Chen X. Aptamer-Drug Conjugates. Bioconjug Chem. 2015;26:2186–97. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNamara JO 2nd, Andrechek ER, Wang Y, Viles KD, Rempel RE, Gilboa E. et al. Cell type-specific delivery of siRNAs with aptamer-siRNA chimeras. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1005–15. doi: 10.1038/nbt1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou J, Swiderski P, Li H, Zhang J, Neff CP, Akkina R. et al. Selection, characterization and application of new RNA HIV gp 120 aptamers for facile delivery of Dicer substrate siRNAs into HIV infected cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:3094–109. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanaka Y, Honda T, Matsuura K, Kimura Y, Inui M. In vitro selection and characterization of DNA aptamers specific for phospholamban. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:57–63. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.149526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greupink R, Bakker HI, van Goor H, de Borst MH, Beljaars L, Poelstra K. Mannose-6-phosphate/insulin-Like growth factor-II receptors may represent a target for the selective delivery of mycophenolic acid to fibrogenic cells. Pharm Res. 2006;23:1827–34. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dougan H, Lyster DM, Vo CV, Stafford A, Weitz JI, Hobbs JB. Extending the lifetime of anticoagulant oligodeoxynucleotide aptamers in blood. Nucl Med Biol. 2000;27:289–97. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(99)00103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shukla RS, Jain A, Zhao Z, Cheng K. Intracellular trafficking and exocytosis of a multi-component siRNA nanocomplex. Nanomedicine. 2016;12:1323–34. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shukla RS, Qin B, Wan YJ, Cheng K. PCBP2 siRNA reverses the alcohol-induced pro-fibrogenic effects in hepatic stellate cells. Pharm Res. 2011;28:3058–68. doi: 10.1007/s11095-011-0475-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng K, Ye Z, Guntaka RV, Mahato RI. Biodistribution and hepatic uptake of triplex-forming oligonucleotides against type alpha1(I) collagen gene promoter in normal and fibrotic rats. Mol Pharm. 2005;2:206–17. doi: 10.1021/mp050012x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng K, Ye Z, Guntaka RV, Mahato RI. Enhanced hepatic uptake and bioactivity of type alpha1(I) collagen gene promoter-specific triplex-forming oligonucleotides after conjugation with cholesterol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:797–805. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.100347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dahms N, Hancock MK. P-type lectins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1572:317–40. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00317-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foulstone E, Prince S, Zaccheo O, Burns JL, Harper J, Jacobs C. et al. Insulin-like growth factor ligands, receptors, and binding proteins in cancer. J Pathol. 2005;205:145–53. doi: 10.1002/path.1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lupold SE, Hicke BJ, Lin Y, Coffey DS. Identification and characterization of nuclease-stabilized RNA molecules that bind human prostate cancer cells via the prostate-specific membrane antigen. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4029–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sefah K, Shangguan D, Xiong X, O'Donoghue MB, Tan W. Development of DNA aptamers using Cell-SELEX. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:1169–85. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li S, Xu H, Ding H, Huang Y, Cao X, Yang G. et al. Identification of an aptamer targeting hnRNP A1 by tissue slide-based SELEX. J Pathol. 2009;218:327–36. doi: 10.1002/path.2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng C, Chen YH, Lennox KA, Behlke MA, Davidson BL. In vivo SELEX for Identification of Brain-penetrating Aptamers. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2013;2:e67. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2012.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.White RR, Sullenger BA, Rusconi CP. Developing aptamers into therapeutics. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:929–34. doi: 10.1172/JCI11325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adler A, Forster N, Homann M, Goringer HU. Post-SELEX chemical optimization of a trypanosome-specific RNA aptamer. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2008;11:16–23. doi: 10.2174/138620708783398331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keefe AD, Pai S, Ellington A. Aptamers as therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:537–50. doi: 10.1038/nrd3141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu Q, Shibata T, Kabashima T, Kai M. Inhibition of HIV-1 protease expression in T cells owing to DNA aptamer-mediated specific delivery of siRNA. Eur J Med Chem. 2012;56:396–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Darmostuk M, Rimpelova S, Gbelcova H, Ruml T. Current approaches in SELEX: An update to aptamer selection technology. Biotechnol Adv. 2015;33:1141–61. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rockey WM, Hernandez FJ, Huang SY, Cao S, Howell CA, Thomas GS. et al. Rational truncation of an RNA aptamer to prostate-specific membrane antigen using computational structural modeling. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2011;21:299–314. doi: 10.1089/nat.2011.0313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qin B, Chen Z, Jin W, Cheng K. Development of cholesteryl peptide micelles for siRNA delivery. J Control Release. 2013;172:159–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jain A, Cheng K. The principles and applications of avidin-based nanoparticles in drug delivery and diagnosis. J Control Release. 2016;245:27–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jain A, Barve A, Zhao Z, Jin W, Cheng K. Comparison of avidin, neutravidin, and streptavidin as nanocarriers for efficient siRNA Delivery. Mol Pharm. 2017;14:1517–1527. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wittrup A, Lieberman J. Knocking down disease: a progress report on siRNA therapeutics. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16:543–52. doi: 10.1038/nrg3978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamada T, Peng CG, Matsuda S, Addepalli H, Jayaprakash KN, Alam MR. et al. Versatile site-specific conjugation of small molecules to siRNA using click chemistry. J Org Chem. 2011;76:1198–211. doi: 10.1021/jo101761g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nair JK, Willoughby JL, Chan A, Charisse K, Alam MR, Wang Q. et al. Multivalent N-acetylgalactosamine-conjugated siRNA localizes in hepatocytes and elicits robust RNAi-mediated gene silencing. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:16958–61. doi: 10.1021/ja505986a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]