Abstract

Background:

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the anxiolytic properties of the decoction of stem bark of Hallea ciliate in mice. The decoction of Hallea ciliata is used in traditional medicine in Cameroon to treat diseases like anxiety disorders, fever, infantile convulsions and malaria.

Materials and Methods:

Stress induced hyperthermia, elevated plus maze, open field and hole-board tests were used. Four different doses of the decoction were administered to mice and their effects were compared to the effects of diazepam and vehicle. Phytochemical characterization of the decoction revealed the presence of alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins and saponins.

Results:

Administration of Hallea ciliata resulted in a significant decrease of stress induced hyperthermia in mice at the doses of 29.5, 59 and 118 mg/kg. In the elevated plus maze test, Hallea ciliata increased the number of entries and the percentages of entries and time into the open arms, and reduced the number of entries and the percentages of entries and time into the closed arms. In the hole-board test, Hallea ciliata increased the number of both head-dipping and crossing and decreased the latency to the first head-dips and rearing. The decoction of Hallea ciliata and diazepam increased locomotion in the open field test.

Conclusion:

The number of rearing and the mass of fecal boli produced were decreased in mice treated with decoction and diazepam. In conclusion, the results indicated that decoction of Hallea ciliata has anxiolytic-like properties in mice and could potentially be used for anxiety treatment.

Keywords: anxiety, herbs, pharmacology, diazepam

Introduction

Anxiety and stress disorders are currently among the ten most important public health concerns, according to the World Health Organization and, have reached epidemic proportions (Thase, 2006). In Cameroon, anxiety disorders are among the top three mental diseases (Ministry of Health of Cameroon, 2006). These disorders are recognized as main risk factors for many other diseases, including cardiovascular, metabolic and neuropsychiatric diseases (Cryan and Holmes, 2005; Thase, 2006). Furthermore, anxiety is among the most prevalent mental disorder with very high comorbidity and severe impact on quality of life (Ngo Bum et al., 2011). In Africa, and particularly in Cameroon, patients mostly go to traditional healers because of the stigma of mental diseases and the side effects of anxiolytic drugs (Abdallah et al., 2014; Griffiths et al., 2014).

A growing number of herbal medicines are being introduced into psychiatric practice on the basis of their efficacy and low side effects for the treatment of psychiatric disorders, as severe depression, anxiety (Ji et al., 2006; Ngo Bum et al., 2009; Shaw et al., 2007; Taiwe et al., 2010). Hallea ciliata Aubrey & Pelegr. (Rubiaceae) (H. ciliata) is used in several conditions in African traditional medicine, particularly in the Northern Cameroon, to treat pain, infantile convulsions, anguish, inflammation, fever, arterial hypertension, diarrhea, diabetes, parasitic infection, mental impairment, and as local antiseptic,. The decoction of this plant together with piper guinense and Xylopia aettiopa is effective for lung diseases, thus being nontoxic in human, (FAO, 1986). Previous studies showed that H. ciliata possess anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties (Dongmo et al., 2003); myorelaxant, antiplasmodial and antipyretic properties (Mibindzou, 2004); anti- trypanosomiase activity (Ogbunugofor et al., 2007) and is a good immunostimulator (Fofana, 2005). However, very little information is available on the effects of H. ciliata on the central nervous system. The present study was undertaken to verify the hypothesis that H. ciliata could exert anxiolytic properties because of its used in traditional medicine in Cameroon to treat anxieties disorders.

Material and Methods

Animals and Treatment

Adult male and female Swiss mice (Mus musculus) weighting 20-24 g were used. The animals were bred in the colony established at the department of Biological Sciences of the University of Ngaoundere (Cameroon). They were housed 5 or 6 per cage and were familiarized with the experimenters and the laboratory environment for at least 4 days before the experiments. Food and water were available ad libitum.

The animal room was maintained at 25 ± 1 °C with a 12/12h light/dark cycle (light on at 6.00 a.m). All experiments were carried out in a quiet room under controlled light conditions between 10:00 a.m. and 3:00 p.m. Mice were divided randomly in 6 groups: one negative control group received distilled water (vehicle), one positive control group received a well-known anxiolytic drug (diazepam or phenobarbital) depending on the test, and four test groups received different doses of the decoction of H. ciliata.

All experiments were performed in accordance with the National Ethical Committee (N°. FWA-IRB00001954) and the internationally accepted Principles for Laboratory Animal Use and Care presented in the US guidelines. All efforts were done to minimize suffering and number of animals used.

Diazepam ampoules (HOFFMANN LA ROCHE, BASEL, SWITZERLAND) and phenobarbital (SIGMA-ALDRICH CO., ST. LOUIS, MO, USA) were used as reference drugs. All solutions were prepared freshly in distilled water on the test days and administered intraperitoneally (i. p) in a volume of 10 mL/kg body weight.

Diazepam, phenobarbital and the different doses of the decoction of H. ciliata were administered orally (p.o) once, 1 hour prior to the beginning of all behavioral tests.

Preparation of the Decoction

Stem bark of H. ciliata were collected in Dang, locality of Ngaoundere (Adamaoua, Cameroon). Voucher specimen of H. ciliata was depDosited at the National Herbarium of Cameroon in Yaounde under the number 2101HNC. For the preparation of the decoction, 5 g of H. ciliata stem bark were macerated in 50 mL of distilled water and boiled to 100 °C for 20 minutes. After cooling, the mixture was filtered with wattman paper n° 1 and used for animal experiments. In other to quantify the dried extract of the decoction, the obtained decoction was dried and the residue was weighed. The doses of the decoction were expressed in mg of dried extract per kg of body weight. The decoction was prepared each day of the experiment. The following doses were used: 11.8, 29.5, 59 and 118 mg/kg.

Phytochemical Screening

Preliminary qualitative chemical screening of the decoction of the stem bark of H. ciliata was done using the methods described for the determination of flavonoids, alkaloids, saponins, tannins, anthraquinons and polyphenols (Harbone, 1976).

Behavioral Tests

Behavioral recording was done blindly.

Stress Induced Hyperthermia (SIH) Test

Experiments were performed according to the methodology described by Borsini et al., (1989) with small modifications (Ngo Bum et al., 2009). The animals (10 per group) were weighed and marked on the tail. Phenobarbital (20 mg/kg, i.p) was given to positive control group, the four doses of the plant were given to the four test groups and distilled water as vehicle was given to the negative control group. 1 hour after each treatment, the rectal temperature was recorded by introducing the rectal borer of thermometer (2 mm of diameter and 2 cm of length) in the rectum of the mice. Rectal borer was put into saline solution (NaCl 9°C) before each temperature measurement. SIH was determined as the difference between the mean temperature of three last mice and the mean temperature of the three first mice in each group.

Elevated Plus Maze (EPM) Test

This test is based on the natural empty space fear of rodents (Ollat and Pirot, 2003). The maze made of wooden consisted of two open arm (15 cm x 45 cm) and two closed arms (15 cm x 45 cm x 20 cm), extending from a central platform (5 cm x 5 cm) and elevated to a height of 50 cm above the floor (Ngo Bum et al., 2009). Here, diazepam (3 mg/kg, i.p.) was given as positive control. One hour after treatment, each animal was placed individually in the center of the maze facing an open arm, away from the observer. The behaviors of the animals were recorded for 5 minutes. The number of entries and the time spent into the open and closed arms were registered. An entry was defined as entry of head and at least the half of the body of animal into an arm. The percentage of time spent into open or closed arms (open or closed arm time/5 min x 100) and percentage of entries (open or closed arm entries/total entries x 100) were calculated for each animal. The number of rearing, head-dipping and grooming were recorded (Augustsson, 2004). The maze was cleaned with ethylic alcohol 70° after each mouse test.

Hole-Board (HB) Test

The hole-board apparatus consisted of a wooden box (40 cm x 40 cm, 1.8 cm height). The floor was divided in 16 equidistant holes of 3 cm in diameter (Lourenzo et al., 2001). The positive control group received diazepam (0.5 mg/kg, i.p.) a tests groups receive different doses of H. ciliata decoction (11.8, 29.5, 59 and 118 mg/kg, p.o.). One hour after treatment each anim placed individually in the center of the board facing away the observer. And the number of rearing (when the animal stand on i paws, raises its forepaws off the ground, extending its body vertically), head-dipping (when the animal places its head into one holes), crossing (when the animal enter a new area with all four paw) were recorded for 5 min. The latency to the first head-dippi measured using a stopwatch (Taiwe et al., 2010). The floor of the apparatus was cleaned with 70 % alcohol solution between each

Open Field (OF) Test

This method is used to evaluate locomotor activity, level of exploration and emotional reaction of animals (Crawley, 1985). Open field consisted of a surrounding square (40 cm x 40 cm) divided in 16 small square and 1 center field (10 cm x 10 cm) wall of 19 cm high (Brown et al., 2007; Jenck et al., 1997). The positive control group received diazepam (0.3 mg/kg, i.p.). One ho treatment, each mouse was placed individually in the center of the arena and the number of crossing, grooming, rearing, the tim in the center and fecal boli weight were recorded for 5 min. Recording were measured manually with a stopwatch.

Data Analysis

Comparisons of the results were performed using computerized linear regression analysis, of GraphPad Prism (version 4.00, GraphPad Soft- ware Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The statistical analysis of the data was performed in each graph by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnet’s bilateral or multiple comparison test. In all cases differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Results

Phytochemical Screening

Chemical screening of the decoction of stem bark of H. ciliata showed the presence of polyphenols (flavonoids, tannins, phlobotannins), alkaloids, saponins, and anthraquinons.

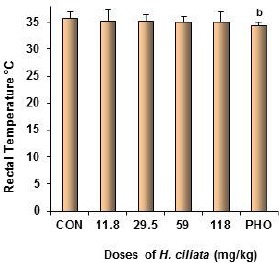

Effect of H. Ciliata on Stress Induced Hyperthermia Test

The decoction of H. ciliata reduced dose dependently the SIH from 2.27 °C in the control group to -0.4° C at the dose of 118 mg/kg [F (6, 60) = 0.45; P<0.01]. HIS was also reduced by phenobarbital (Fig 1). In the contrary, H. ciliata had no effect on the body temperature of mice (Fig 2).

Figure 1.

Effect of the decoction of H. ciliata on the stress induced hyperthermia

Data are A°C (the difference between the mean temperature of the three last mice and the mean temperature of the three first mice). N = 6, p < 0.01, p < 0.001c; one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnet’s bilateral comparison test. CON = distilled water (vehicle), PHO = phenobarbital 20 mg/kg. All other groups were compared to CON, the negative control group

Figure 2.

Effect of the decoction of H. ciliata on the body temperature on stress induced hyperthermia in mice.

Data are temperature (°C). N = 10, p < 0.01; one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnet’s bilateral comparison test. CON = distilled water (vehicle), PHO = phenobarbital 20 mg/kg. All other groups were compared to CON, the negative control group.

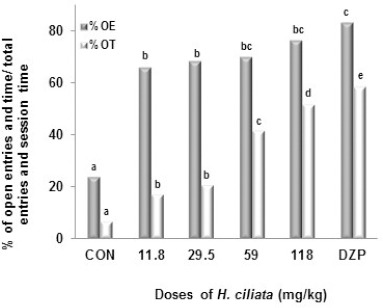

Effect of H. Ciliata on Elevated plus Maze

The administration of the decoction resulted in a significant increase in the number of entries into open arms from 1.67 in the negative control group to 9.67 at the dose of 118 mg/ kg of H. ciliata [F (6, 35) = 9.13; p < 0.001] (Table 1). The percentage of open entries was therefore highly significantly increased from 24.54% in the control group to 76.82% at the dose of 118 mg/ kg of H. ciliata [F (6, 35) = 19.82; p < 0.001]. The percentage of time spent in the open arms increased also from 7.17% in the control group to 58.00% [F (6, 35) = 101.46; p < 0.001] at the dose of 118 mg/kg of H. ciliata. As expected, in the positive control group 3 which received diazepam (3 mg/kg, i.p.), the percentage of entries and time spent into the open arms increased (Fig 3). The time spent in the closed arms was as well reduced by both the decoction and diazepam. Diazepam and the decoction (dose 118 mg/kg) also induced a significant reduction of percentage of entries in the closed arms, from 73.94% in the vehicle-treated group to 23.18% and 16.59% [F (6, 35) = 19.78; p< 0.001], respectively (Fig 4). The number of rearing [F (6, 35) = 8.55; p< 0.001], head-dipping (F (6, 35) = 16.85; p< 0.0001] and stretched attend posture [F (6, 35) = 3.93; p < 0.008] were also reduced by diazepam and the decoction while the number of grooming increased (Table 1).

Table 1.

The number of open arms entries, closed arms entries, rearing, head- dipping and grooming on Elevated Plus Maze

| Doses of H. ciliate (mg/kg) | Distilled water | 11.8 | 29.5 | 59 | 118 | Diazepam |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open arms entries | 1.67 ± 0.44 | 7.83 ± 0.89c | 8.00 ± 0.67c | 9.00 ± 2.67c | 9.67 ± 2.67c | 10.00 ± 1.33c |

| Closed arms entries | 6.00 ± 2.67 | 4.00 ± 0.67 | 3.83 ± 1.5a | 3.16 ± 0.55b | 2.67 ± 0.67b | 2.00 ± 0.33c |

| Total arms entries | 7.67 ± 2.83 | 11.83 ±1.16a | 11.83 ± 1.67a | 12.17 ±2.83a | 12.33 ± 2.33a | 12.00 ± 1.33a |

| Rearing | 11.67 ± 2.09 | 6.50 ± 1.28c | 5.50 ± 1.50c | 6.83 ± 1.89c | 5.50 ± 2.17c | 5.83 ± 0.89c |

| Head- dipping | 12.17 ± 1.22 | 5.33 ± 1.17c | 4.83 ± 1.83c | 4.50 ± 1.00c | 3.17 ± 0.56c | 3.67 ± 1.00c |

| Grooming | 1.67 ± 0.27 | 2.00 ± 0.67 | 2.16 ± 0.61 | 1.67 ± 0.89 | 3.00 ± 1.00a | 4.17 ± 1.60c |

| SAP | 8.17 ± 4.22 | 8.16 ± 2.14 | 5.00 ± 2.67 | 4.67 ± 2.44 | 3.00 ± 3.00a | 0.83 ± 0.56b |

Data are mean ± S.E.M., n = 6,

=p < 0.05,

=p < 0.01,

=p < 0.001, ANOVA followed by Dunnett (bilateral) comparison test.

Figure 3.

Effect of the decoction of H. ciliata on EPM in mice.

Data are the percentage of open arms entries and the percentage of open arms time. N = 6; one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnet’s multiple comparison test. %OE = Percentage of open arm entries, %OT = Percentage of time spent in open arm, CON = distilled water (vehicle), DZP = diazepam 3 mg/kg.

Figure 4.

Effect of the decoction of H. ciliata on EPM in mice

Data are the percentage of closed arms entries and the percentage of closed arms time. N = 6; one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnet’s multiple comparison test. %CO = Percentage of closed arms entries, %CT: Percentage of time spent in closed arms, CON =distilled water (vehicle), DZP = diazepam 3 mg/kg.

Open Field

As in the elevated plus maze, the number of rearing was decreased both by diazepam and the decoction from 24.4 for the vehicle- treated group to 12.0 at the dose 118 mg/kg of H. ciliate and to 4.4 for diazepam [F(5,29) = 9.82; p < 0.001] (Table 2). The decoction and diazepam also decreased fecal boli [F (5, 29) = 9.81; p < 0.001]. Contrarily, the decoction increased the number of crossing and center time from 20.8 and 3.4 in the vehicle-treated group to 72.4, and 16.6 at the dose of 118 mg/kg of H. ciliata, [F(5,29) = 12.00; p < 0.001] and [F (5,29) = 39.023; p < 0.001], respectively. Increase was also noted in grooming (Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of crossing, rearing, grooming, center time and fecal boli on Open Field

| Doses of H. ciliate (mg/kg) | Distilled water | 11.8 | 29.5 | 59 | 118 | Diazepam |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crossing | 20.80 ± 2.24 | 58.40 ± 18.24b | 80.40 ± 4.88c | 84.20 ± 6.24c | 72.40 ± 10.32c | 78.40 ± 9.68c |

| Rearing | 24.40 ± 7.92 | 13.60 ± 4.88b | 13.00 ± 4.00c | 15.60 ± 5.12b | 12.00 ± 4.40c | 4.40 ± 1.92c |

| Grooming | 0.60 ± 0.48 | 2.00 ± 0.80 | 2.60 ± 1.52 | 2.60 ± 1.12 | 3.00 ± 1.20a | 3.60 ± 0.88b |

| Center time (s) | 3.40 ± 1.84 | 6.60 ± 5.52 | 10.40 ± 3.12 | 14.00 ± 10.00a | 16.60 ± 3.52a | 82.00 ± 10.00c |

| Fecal boli (g) | 0.27 ± 0.22 | 0.001 ± 0.002c | 0.001 ± 0.001c | 0.018 ± 0.003c | 0.00 ± 0.00c | 0.00 ± 0.00c |

Data are mean ± S.E.M., n= 6,

=p < 0.05,

= p < 0.01

= p < 0.001, ANOVA followed by Dunnett (bilateral) comparison test.

Hole-Board

The number of rearing was significantly reduced by H. ciliata, from 7.8 in the vehicle treated-group to 3.0 and 2.8 at the doses 29.5 and 59 mg/kg of the decoction, respectively. The latency time to the first head-dipping was also significantly reduced by H. ciliata, from 8.6 in the vehicle-treated group [(F (5, 29) = 8.99; p < 0.001] to 4.0 (dose of 118 mg/kg of the plant) and to 2.0 (diazepam). In the contrary, the number of head-dipping increased from 13.2 in the vehicle-treated group to 40.4 at the dose of 118 mg/kg of the decoction and to 33.6 for the diazepam- treated group [F (5, 29) = 4.52; p < 0.005]. The number of grooming was also increased by the decoction [F (5, 29) = 0.36; p < 0.90] and diazepam (Table 3).

Table 3.

Number of crossing, rearing, grooming, head-dipping and first head - dipping time on Hole Board

| Doses of H. ciliate (mg/kg) | Distilledwater | 11.8 | 29.5 | 59 | 118 | Diazepam |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crossing | 28.00 ± 6.40 | 28.00 ± 6.40 | 42.80 ± 9.36 | 38.20 ± 7.28 | 19.00 ± 6.40 | 31.80 ± 15.78 |

| Rearing | 7.80 ± 2.64 | 3.00 ± 0.80a | 3.00 ± 2.40a | 2.80 ± 0.72a | 3.20 ± 1.76a | 5.80 ± 2.56 |

| Grooming | 0.60 ± 0.48 | 2.00 ± 0.80 | 2.60 ± 1.52 | 2.60 ± 1.12 | 3.00 ± 1.20a | 3.60 ± 0.88b |

| Head-dipping | 13.20 ± 3.76 | 17.80 ± 4.56 | 20.00 ± 7.20 | 26.80 ± 3.84 | 40.40 ± 16.32b | 33.60 ± 9.92a |

| Latency to | 8.60 ± 2.07 | 8.00 ± 1.00 | 7.20 ± 1.48 | 5.00 ± 1.87a | 4.00 ± 3.16b | 2.00 ± 1.00c |

| first head-dipping (s) |

Data are mean ± S.E.M., n= 6,

=p < 0.05,

= p < 0.01,

= p < 0.001, ANOVA followed by Dunnett (bilateral) comparison test.

Discussion

The anxiolytic properties of the decoction of H. ciliata were investigated for the first time using behavioral testing in mice.

The present results showed that the decoction of the stem bark of H. ciliata reduced hyperthermia induced by stress. This decrease similar to that induced by phenobarbital, suggested anxiolytic properties of the plant, as hyperthermia induced by stress is reversed by anxiolytics (Berend and al., 2003; Borsini et al., 2002; Lecci et al., 1990; Ngo Bum et al., 2009). Anxiolytic properties of the decoction were confirmed in the elevated plus maze, the open field and hole board tests. The experiment on the elevated plus maze clearly showed that vehicle-treated mice had a strong preference for the closed arms compared to those treated with the decoction of H. ciliata. The number of entries and the time spent into open arms and their percentage; the main behavioral parameters of the evaluation of the anxiolytic effect on this maze (Fakeye et al., 2008; Grundmann et al., 2007; Pollyanna et al., 2007; Rabbani et al., 2008; Reginatto et al., 2006) were increased by the decoction of H. ciliata. Significant decrease in the number of “rearing” associated both to the decrease of closed arms entries and the increase of open arms entries revealed that the increase in open arms entries was not due to the decoction of H. ciliata induced locomotion but rather to the exploration confirming the decrease of anxiety in mice treated with the decoction (Ngo Bum et al., 2009; 2011). In addition, the plant induced a significant increase in the number of grooming in mice treated with the highest dose of H. ciliata (118 mg/kg) and diazepam. Grooming is a behavior that reflects the removal of stress in animals (Augustsson, 2004).

In open field test, H. ciliata and diazepam increased the number of “crossing”. The increase in the number of crossing (exploratory activity) is a sign of intrinsic inhibition of anxiety induction and not an increase in locomotion since rearing which is a locomotion indicator in this test was reduced (Ngo Bum et al., 2009; Pitchaiah et al., 2008; Pollyanna and al., 2007). Reduction of defecation in mice treated with diazepam and the extract of H. ciliata also suggested an anxiolytic activity (Shaw et al., 2007). In hole-board test, the decoction of H. ciliata increased the number of crossing and head-dipping (exploratory activity) and decreased its latency of onset. Since increasing the number of crossing and head-dipping in this test is a sign of anxiolysis (Crawley, 1985; File and Wardill., 1975; Li Min et al., 2005; Lourenzo et al., 2001; Tsuji et al., 1998), these results also indicated the anxiolytic properties of H. ciliata. H. ciliata could have exerted anxiolytic properties through its flavonoids, alkaloids and tannins contain. For instance flavonoids selectively bind with high affinity to benzodiazepine receptors and induce a significant anxiolytic activity (Grundmann et al., 2007). As anxiolytic activities could be mediated by different mechanism of action, we hypothesized that the anxiolytic properties of the decoction H. ciliata could be due to the interaction of its contained compounds with receptors in the central nervous system such as benzodiazepine and GABA sites of GABA-A receptor complex as agonists (EPM test is very sensitive to benzodiazepine receptor agonists), 5-HT1 receptor as agonists (Belzung, 1999; Garcia-Garcia et al., 2014; Lolli et al., 2007; Rodgers et al., 1997) or 5-HT-2 and 5-HT-3 receptors as antagonists (Brown et al., 2007; Ferrero et al., 1999; Rodgers, 2001).

Conclusion

The decoction of H. ciliata showed anxiolytic like-effects that are used in traditional medicine in Cameroon to treat anxieties disorders.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Laboratory of Medicinal Plants, Health and Galenic Formulation of the Faculty of Science of the University of Ngaoundere for the support and didactical equipment

References

- 1.Abdallah S. D, Marian J, Stig Wall, Johann Groenewald, Julian Eaton, Vikram Patel, Palmira dos Santos, Ashraf Kagee, Anik Gevers, Charlene Sunkel, Gail Andrews, Ingrid Daniels, David Ndetei. Declaration on mental health in Africa: moving to implementation. Global Health Action. 2014;7:24589. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.24589. http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/gha.v7.24589 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Augustsson H. Etho experimental study of behavior in wild and laboratory mice. Doctorate thesis, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Uppsala. 2004:62. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belzung C. Measuring rodent exploratory behavior. Crusio W. E, Gerlai, editors. Handbook of Molecular- Genetic techniques. Brain and Behavioural Research. 1999;11:738–749. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berend O, Zethof T, Pattif T, Mey Van Boogaert, Ruud Var Oorschot, Cloush Lealy, Oosting R, Arjan Boowkenecht, Ja Vering, Jarxarder Crugter, Luceana Groeming. Stress-induced hyperthermia and anxiety: pharmacological validation. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2003;463:117–132. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01326-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borsini F, Lecci A, Volterra G, Meli A. A model to measure anticipatory anxiety in mice. Psychopharmacology. 1989;98:207–211. doi: 10.1007/BF00444693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borsini F, Podhorna J, Donatella M. Do animal model of anxiety predict anxiolytic- like effects of antidepressants. Psychopharmacology Review. 2002;163:121–141. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown E, Neils Hurd, Suzanne Mc Call, Thomas E. Ceremuga. Evaluation of the anxiolytic effects of chrysin, a passiflora incarta extract, in the laboratory rat. American association of Nurse Anesthetists Journal. 2007;75(5):333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crawley J. N. Exploratory Behavior Models of Anxiety in mice. Neurosciences and behavioral reviews. 1985;9:37–44. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(85)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cryan J. F, Holmes A. The ascent of mouse: advances in modelling human depression and anxiety. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2005;4:775–790. doi: 10.1038/nrd1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dongmo A.B, Kamanyi A, dzikouk G, Nkek B, Tan P.V, Nguelefack T, Nole T, Bopdet M, Wagner H. Anti- inflammatory and analgesic properties of the stem bark extract of Mitragyna ciliata (Rubiaceae) Aubriew Pellegre. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2003;80(1):17–21. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00252-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fakeye T. O, Pal A, Khanija S. P. Anxiolytic and sedative effects of extracts of Hibiscus sabdariffa Linn (family Malvaceae) Africa journal of Medical Sciences. 2008;37:49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization) Some medicinal forest plants of Africa and Latin America. Rome, Italia: 1986. M-71 ISBN 92-5-1 02361-1, 142. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrero L, Beani L, Trist D, Reggiania Bianchi. Effects of cholécystokinine peptids and GV 150013 a selective cholécystokinine B receptor antagonist on electrically evoked endogenous GABA release from cortical slices. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1999;73:1973–1981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.File S. E, Wardill A. G. Validity of head-dipping as a measure of exploration in a modified hole board. Psychopharmacologia (Berl) 1975;44:53–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00421184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fofana S. Exploration biochimique sur le pouvoir de immunogène trois plantes en Còte d’Ivoire: Alstonia boonei (Apocynaceae), Mitragyna ciliata (Rubiaceae) et Terminalia catappa (Combretaceae) Ph. D Thesis. University of Bamako Mali 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia-Garcia A.L, Meng Q, Richardson-Jones J, Dranovsky A, Leonardo E. D. Disruption of 5-HT 1°function in adolescence but not early adulthood leads to sustained increases of anxiety. Neurosciences. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.05.076. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.05.076 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Griffiths K.M, Carron-Arthur B, Parsons A, Reid R. Effectiveness of programs for reducing the stigma associated with mental disorders. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(2):161–75. doi: 10.1002/wps.20129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grundmann O, Jun-Ichiro N, Shujiro Seo, Veronika Butterweck. Anti- anxiety effects of Apocynum venetum L. in the elevated plus maze. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2007;110:406–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harbone J. B. A guide to modern techniques of plant analysis. 1st ed. Champignon and Hall; London: 1976. Phytochemical methods; pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jenck F, Moreau J. L, James R. M, Gavin J.K, Rainer K.R, Monsma F.J, Jr, Nothatker H.P, Civelli O. Orphanin FQ acts as an anxiolytic to attenuation behavioural responses to stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(7):14854–14858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ji W. J, Nam Y. A, Hye R. O, Bo K. L, Sun J. K, Jae H. C, Jong H. R. Anxiolytic effects of the aqueous extract of Uncaria rhynchophylla. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2006;108(2):193–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lecci A, Borsini F, Giovanna Volterra, Alberto Meli. Pharmacological validation of a novel animal model of. anticipatory anxiety in mice. Psychopharmacology. 1990;101:255–261. doi: 10.1007/BF02244136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Min Si, Wei C, Wei Jing Li, Rui Wang, Yu Lei Li, Wen Juan W, Xioa Juan M. The effects of angelica essential oil in social interaction and hole board test. Pharmacology Biochemistry and behavior. 2005;94(4):838–842. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lolli Luiz F, Claudia M. S, Càssio V. R, Larissa De Biaggi Villas-Boas, Ced A Moroes Santos and Rubia De Oliviera. Possible involvement of GABAA - benzodiazépine rceptor in the anxiolytic- like effect induced by Passiflora actinia extracts in mice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2007;111:308–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lourenzo Da Silva A, Elisabetsky E. Interference of propylene glycol with the hole board test. Brasilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 2001;34:545–547. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2001000400016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mibindzou Mouellet A. Screeming phythochimique de deux espèces de plantes: Crotalia retusa L (Papilionaceae) et al H. ciliata Aubrev & Pellegr. (Rubiaceae) récoltées au Gabon. Ph. D Thesis. University of Bamako Mali. Ministry of Health Cameroon; National program for mental health, “programme national de santémentale”. 2004:1–31. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ngo Bum E, Taiwe G.S, Moto F.C.O, Ngoupaye G.T, Nkantchoua G.C.N, Pelanken M.M, Rakotonirina SV, Rakotonirina A. Anticonvulsant, anxiolytic and sedative properties of the roots of Nauclea latifolia Smith in mice. Epilepsy and Behavior. 2009;15(4):434–440. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ngo Bum E, Nanga L. D, Soudi S, Taiwe G. S, Ayissi E. R, Dong C, Lakoulo N. H, Maidawa F, Rakotonirina A, Seke P. F. E, Rakotonirina S. V, Dimo T, Njikam Njifutie, Kamanyi A. Anxiolytic activity evaluation of four medicinal plants from cameroon. African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2011;8:130–139. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v8i5S.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogbunugafor H. A, Okochi V. I, Okpuzor J, Adedayo Tililayo, Esue S. Mitragyna ciliata and its trypanosidal activity. African journal of biotechnology. 2007;6(20):2310–2313. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ollat H, Pirot S. Antidépreseurs, sérotonine et anxiété. Neuropsychiatrie: Tendances et Débats. 2003;13:21–29. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pitchaiah G, Viswanatha G. L, Srinath R, Nandakumar K. Pharmacological evaluation of alcoholic extract of stem bark of Erythrina variegate for anxiolytic and anticonvulsant activity in mice. Pharmacology Online. 2008;3:938–947. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pollyanna Celso de Castro, Alberto Hoshino, Jair Campos da Silva, Ruli Fùlvio. Possible anxiolytic effect of two extract of passiflora quadragularis L. in experimental models. Phytotherapie research. 2007;21:481–484. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rabbani M, Saffadi S. E, Mohammadi A. Evaluation of the anxiolytic effect of Nepita persica Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2008;5(2):181–186. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reginatto F. H, Fernanda Raquel D. P, Joào Quevedo, George Gonzalez Ortega, Eloir P. Schenkel. Evaluation of anxiolytic activities of spried dried powder of two South Brazilian Passiflora species. Phytotherapy Research. 2006;20:348–351. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodgers R.J. Anxious genes, emerging themes. Commentary on Belzung “The genetic basis of the pharmacological effects of anxiolytics” and Olivier et al. “The 5-HT1A receptor knockout mouse and anxiety”. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2001;12:471–476. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200111000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodgers R.J, Cao B.-J, Dalvi A, Holmes A. Animal models of anxiety: an ethological perspective. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biolgy Research. 1997;30:289–304. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x1997000300002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shaw D, Annett J. M, Doherty B, Leslie J. C. Anxiolytic effects of lavender oil inhalation on open field behavior in rat. Phytomedecine. 2007;14:613–620. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taiwe G.S, Ngo Bum E, Dimo T, Talla E, Weiss N, Dawe A, Moto F.C.O, Sidiki N, Dzeufiet P.D, De Waard M. Antidepressant, Myorelaxant and Anti-Anxiety-Like Effects of Nauclea latifolia Smith (Rubiaceae) Roots Extracts in Murine Models. International Journal of Pharmacology. 2010;6(4):326–333. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thase M.E. Managing depressive and anxiety disorders with escitalopram. Expert Opinion of Pharmacotherapy. 2006;7:429–440. doi: 10.1517/14656566.7.4.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsuji Takeda M H, Matsumiya T. Different effects of 5 HT-1A receptor agonist and benzodiazepine anxiolytics on the emotional state of naîve and stress mice, a study using hole-board test. Psychopharmacology. 1998;152(2):157–166. doi: 10.1007/s002130000514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]