Abstract

Rationale: Poor functional status is common after critical illness, and can adversely impact the abilities of intensive care unit (ICU) survivors to live independently. Instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), which encompass complex tasks necessary for independent living, are a particularly important component of post-ICU functional outcome.

Objectives: To conduct a systematic review of studies evaluating IADLs in survivors of critical illness.

Methods: We searched PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, SCOPUS, and Web of Science for all relevant English-language studies published through December 31, 2016. Additional articles were identified from personal files and reference lists of eligible studies. Two trained researchers independently reviewed titles and abstracts, and potentially eligible full text studies. Eligible studies included those enrolling adult ICU survivors with IADL assessments, using a validated instrument. We excluded studies involving specific ICU patient populations, specialty ICUs, those enrolling fewer than 10 patients, and those that were not peer-reviewed. Variables related to IADLs were reported using the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS).

Results: Thirty of 991 articles from our literature search met inclusion criteria, and 23 additional articles were identified from review of reference lists and personal files. Sixteen studies (30%) published between 1999 and 2016 met eligibility criteria and were included in the review. Study definitions of impairment in IADLs were highly variable, as were reported rates of pre-ICU IADL dependencies (7–85% of patients). Eleven studies (69%) found that survivors of critical illness had new or worsening IADL dependencies. In three of four longitudinal studies, survivors with IADL dependencies decreased over the follow-up period. Across multiple studies, no risk factors were consistently associated with IADL dependency.

Conclusions: Survivors of critical illness commonly experience new or worsening IADL dependency that may improve over time. As part of ongoing efforts to understand and improve functional status in ICU survivors, future research must focus on risk factors for IADL dependencies and interventions to improve these cognitive and physical dependencies after critical illness.

Keywords: critical illness, critical care outcomes, functional outcomes, instrumental activities of daily living, patient-centered outcomes

Each year, millions of patients survive critical illness (1–3) but often experience new and persistent physical, psychiatric, and cognitive, impairments (4–10), collectively known as the “post–intensive care syndrome” (11, 12). Cognitive impairments after critical illness are often severe, and adversely affect complex cognitive functions (e.g., memory and executive function) that are essential for day-to-day functioning (13, 14). Physical impairments are also present in many patients (6, 15, 16), and include deficits such as neuromuscular weakness and impaired pulmonary function (6, 7). Psychiatric symptoms are wide-ranging, including depression (7, 17–21), anxiety (7, 9, 10, 19), and posttraumatic stress disorder (21–24). Many patients never return to their preillness functional baseline (7, 23, 25, 26). Each of these types of impairments is associated with long-lasting impairments in daily functioning.

Assessment of functional abilities after critical illness is crucial as functional impairments may interfere with the ability to live independently. Various approaches are available to assess functional outcomes after critical illness, including measures of strength and mobility, and assessment of activities of daily living (ADLs). Activities of daily living involve one’s ability to complete simple daily tasks such as bathing, dressing, and feeding, whereas instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) involve more complex tasks such as financial and medication management, driving, shopping, house cleaning, and meal preparation. ADLs and IADLs are both essential to patient functioning and ability to live independently (27), and dependencies are associated with cognitive and physical impairments (28, 29). IADL dependencies reflect higher order functional impairments due to the cognitive demands required for successful task completion (30, 31). Further, IADL dependency is associated with a wide range of cognitive impairments (14, 28, 29), and new IADL dependency predicts future decline in cognitive function (30). Thus, IADLs represent a clinically meaningful postdischarge outcome in intensive care unit (ICU) survivors (30, 32, 33).

Impairments in IADL have been increasingly evaluated in ICU survivors (2, 34). Hence, our objectives were to synthesize existing data to (1) assess the prevalence of IADL impairments in survivors of critical illness, (2) describe the type of IADL dependency and changes in IADL dependency over time, and (3) identify risk factors associated with IADL dependency after critical illness.

Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (35) were followed for reporting this systematic review.

Search Strategy

We searched using PubMed, CINAHL, the Cochrane Library, SCOPUS, and the Web of Science through December 31, 2016 (see Appendix 1 in the online supplement). Our search strategy focused on articles that assessed IADLs in adult survivors of critical illness, using keywords associated with “critical illness/intensive care” and “IADL” and “functional outcomes” as per the eligibility criteria below. The initial search was limited to human studies and the English language, except for the Cochrane Library (which did not allow language limitation). Additional articles were identified from reference lists of eligible studies and personal files.

Article inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) study population of adult ICU survivors, and (2) assessment of IADLs (complex skills that support living independently), using a validated instrument designed specifically to evaluate IADLs. We excluded studies that (1) enrolled specific ICU populations, such as neurological (e.g., traumatic brain injury or subarachnoid hemorrhage) or cardiac surgery patients; (2) primarily specialty ICU; (3) had sample sizes less than 10 at follow-up; or (4) were not peer-reviewed, including published abstracts and dissertations.

Study Screening and Data Extraction

Each citation was independently reviewed for eligibility by two trained researchers (M.R.S. and R.O.H.) via review of titles and abstract, and then full text articles. Disagreement regarding eligibility was resolved by consensus. Relevant data were extracted for eligible articles by the same researchers and included study design, study setting, patient characteristics, instruments used, and relevant outcomes. Variables related to IADLs were coded and categorized using the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). The PROMIS system was developed by the National Institutes of Health and includes a structure to guide research about physical, mental, and social aspects of health and to identify which outcomes are important to patients (www.nihpromis.org) (36, 37).

Results

Study Selection

The search yielded 991 citations (Figure 1) After removal of duplicate records, screening of titles and abstracts, and identification of 23 additional studies from reference lists and personal files, 50 eligible full-text articles were evaluated for inclusion. Thirty-six articles were excluded as 29 did not include post-ICU IADL assessment using a validated measure and seven described nonadult ICU survivors. Of the 17 remaining articles, one study (38) was excluded as it reported identical data to a previous publication from the same cohort (6, 39), resulting in 16 studies of unique patient cohorts in this review (2, 17, 18, 39–50) (Figure 1 and Table 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Table 1.

Studies of instrumental activities of daily living in critically ill patients

| Study [Author (Ref.) (place, yr)] | Study Design and Setting | Sample Characteristics and Follow-Up | Sample Size | IADL Instrument | Significant Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abelha et al. (40) (Portugal, 2013) | Prospective cohort | Surgical postoperative | n = 562 enrolled | Lawton IADL | 19% had pre-ICU IADL dependencies |

| Surgical ICU | 6-mo follow-up | n = 410 at 6 mo | 40% had post-ICU IADL dependencies | ||

| Single institution | 6% died | ||||

| 21% lost to follow-up | |||||

| Bienvenu et al. (17) (USA, 2012) | Prospective cohort | Mechanically ventilated patients with acute lung injury | n = 196 enrolled | Lawton IADL | 40% with pre-ICU IADL dependency |

| Medical–surgical ICU | 3-, 6-, 12-, and 24-mo follow-up | n = 146 at 24 mo | 45% had post-ICU IADL dependency at 24-mo follow-up | ||

| Four institutions | 16% died | ||||

| 10% lost to follow-up | |||||

| Boumendil et al. (39) (France, 2004) | Prospective cohort | Age > 75 yr | n = 192 enrolled | Lawton IADL | 56% had IADL ≥ 1 |

| Medical ICU | 24-mo follow-up | 57% died before follow-up | 10% unable to do self-care or perform IADLs | ||

| Single institution | n = 45 with IADL scores at 2 yr | ||||

| 46% incomplete data | |||||

| Broslawski et al. (41) (USA, 1995) | Prospective cohort | Age ≥ 65 yr | n = 45 enrolled | Lawton IADL | 22% had increased IADL dependencies at 6 mo compared with pre-ICU† |

| Medical ICU | 6-mo follow-up | n = 27 at 6 mo | |||

| Single institution | 40% died | ||||

| 0% lost to follow-up | |||||

| Brummel et al. (42) (USA, 2014) | Prospective cohort | >12 h of mechanical ventilation | n = 126 enrolled | FAQ | Surrogate baseline: 21% had IADL dependencies |

| Medical ICU | 3- and 12-mo follow-up | n = 63 at 12 mo | At 12-mo follow-up: 5% had IADL dependencies | ||

| Single institution | 50% died or lost to follow-up | ||||

| Chelluri et al. (43) (USA, 2004) | Prospective cohort | ≥48 h of mechanical ventilation | n = 359 enrolled at 1 yr | Lawton IADL | 41% of survivors had 1 baseline IADL dependency |

| Medical, neurological, trauma, and surgical ICUs | 12-mo follow-up | n = 296 completed 1 yr of follow-up | 68% had >1 IADL dependency at 1 yr (7% dependent in all IADLs)† | ||

| Single institution | 18% lost to follow-up | ||||

| Cox et al. (44) (USA, 2007) | Prospective cohort | Prolonged mechanical ventilation (≥21 d or ≥96 h with tracheostomy) | n = 817 enrolled | Lawton IADL | More IADL dependencies associated with prolonged compared with short-term mechanical ventilation |

| Medical and surgical ICUs | 2-, 6-, and 12-mo follow-up | n = 114 eligible for 12-mo follow-up | |||

| Single institution | n = 42 completed follow-ups at 12 mo | ||||

| 57% died | |||||

| 6% lost to follow-up | |||||

| Daubin et al. (45) (France, 2011) | Prospective cohort | Age ≥ 75 yr | n = 100 enrolled | Lawton IADL | No significant change at 3 mo from pre-ICU IADL (P = 0.04) |

| Medical ICU | 3-mo follow-up | n = 38 at 3 mo | |||

| Single institution | 61% died | ||||

| 1% lost to follow-up | |||||

| Haas et al. (46) (Brazil, 2013) | Prospective cohort | ≥24 h in ICU | n = 506 enrolled at 24 mo | Lawton IADL | Significant decline in Lawton scores for certain subsets of patients at 24 mo compared with ICU discharge (P < 0.001) |

| Non-trauma ICUs | 48-mo follow-up | n = 499 at 2 yr | |||

| Two institutions | 1% missing data | ||||

| 0% died | |||||

| Iwashyna et al.* (2) (USA, 2010) | Prospective cohort from Health and Retirement Study | Severe sepsis and age > 50 yr | n = 516 enrolled | Health and Retirement Core Interview Questionnaire Section G | Mean of 1.57 new functional limitations in patients without limitations before sepsis |

| ICU admission | Interviewed every 2 yr | Mean of 1.5 new IADL dependencies in patients with mild to moderate limitations before sepsis | |||

| Jackson et al. (34) (USA, 2007) | Multicenter prospective longitudinal cohort | Negative brain CT scan | n = 58 enrolled | FAQ | 22% had IADL dependencies in memory, managing finances, and making travel plans |

| Trauma ICU | 12- to 24-mo follow-up | 0% died | |||

| Single institution | 0% lost to follow-up | ||||

| Jackson et al. (47) (USA, 2012) | Randomized trial of home-based cognitive, physical, and functional rehabilitation vs. usual care | Enrolled in BRAIN-ICU Study | n = 21 enrolled | FAQ | No difference in pre-IADL dependency between the two groups |

| Medical–surgical ICU | 3-mo follow-up | 8, usual care; 13, intervention | IADLs improved in the treatment group at 3 mo (P = 0.04) | ||

| Single institution | 0% died | ||||

| 0% lost to follow-up | |||||

| Jackson et al. (18) (USA, 2014) | Prospective cohort | Respiratory failure, cardiogenic or septic shock | n = 826 enrolled | FAQ | 23% had post-ICU IADL dependencies at 12 mo† |

| Medical–surgical ICU | 3- and 12-mo follow-up | n = 382 (46%) at 12 mo | |||

| Multicenter | 38% died | ||||

| 16% lost to follow-up | |||||

| Quality of Life after Mechanized Ventilation in the Elderly Study Investigators (48) (USA, 2002) | Prospective cohort | >48 h of mechanical ventilation | n = 817 enrolled | Lawton IADL | Increased IADL dependency compared with pre-ICU at 2 mo |

| Medical, surgical, neurological, and trauma ICUs | 2-mo follow-up | n = 232; complete data at 2 mo | |||

| Single institution | 43% died | ||||

| 29% lost to follow-up or incomplete data | |||||

| Sacanella et al. (49) (Spain, 2011) | Prospective cohort | Age ≥ 65 yr | n = 230 enrolled | Lawton IADL | IADLs decreased from baseline (6.7 vs. 5.3; P < 0.001) |

| Medical ICU | 12-mo follow-up | n = 112 at 12 mo | IADLs did not recover to baseline in 45% by study end | ||

| Single institution | 51% died | IADL dependency increased ≥2 activities in 27% of patients | |||

| 0% lost to follow-up | |||||

| Van Pelt et al. (50)‡ (USA, 2007) | Prospective cohort | >48 h of mechanical ventilation | n = 169 enrolled | Lawton IADL | 42% had pre-ICU functional dependency |

| Medical, surgical, and trauma ICUs | 2-, 6-, and 12-mo follow-up | 0% died | 70% had functional dependency at 12 mo | ||

| Single institution | 0% lost to follow-up | Functional dependencies for problem solving, laundry, housekeeping, and managing finances |

Definition of abbreviations: BRAIN-ICU = Bringing to Light the Risk Factors and Incidence of Neuropsychological Dysfunction in ICU Survivors; CT = computed tomography; FAQ = Functional Activities Questionnaire; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; ICU = intensive care unit.

Report only on sepsis survivors, not on patients with nonsepsis hospitalization.

The percentage of pre-ICU IADL dependencies was not reported.

Data are a selected subset of the Quality of Life Study data (data from caregiver and matched patient) that report 1-yr outcome data. These patients are included in the total number of patients we reported, as it is not possible to know the overlap between Quality of Life and Cox studies.

Study Characteristics

Of the 16 included studies, 11 were conducted in the United States, four in Europe, and one in South America (Table 1). Fifteen studies (94%) involved a prospective cohort design and one was a randomized controlled trial. Eleven (69%) studies were conducted in a single institution and five studies were conducted in multiple institutions. Nine studies (56%) were published since 2010.

Participants and Follow-Up

The 16 studies enrolled 4,723 patients with a mean (SD) sample size of 315 (270) (range, 21–826) patients (Table 1). Sixty-five percent of enrolled patients completed the IADL assessment, with sample sizes ranging from 21 to 499 patients (mean [SD], 191 [176]). The mean (SD) time to follow-up was 12.9 (7.9) months (range, 2 to 24 mo) (Table 1), with eight studies (50%) having 2- or 3-month follow-up, six (38%) with 6-month follow-up, seven (44%) with 12-month follow-up, and five (31%) with 48-month follow-up. Ten studies assessed IADL at two or more time points (six studies with more than two follow-up times).

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Measures

Three different IADL questionnaires were used: the Lawton IADL questionnaire (Lawton IADL) (31) in 11 studies (69%), the Pfeffer Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ) (51) in four studies (25%), and the 2012 Health and Retirement Study Core Interview Questionnaire Section G (52) in one study (6%) (Table 2) The Lawton IADL is an eight-item questionnaire that assesses the following eight tasks: using the telephone, shopping, housekeeping, washing laundry, food preparation, using public transportation, managing medications, and managing finances. Lawton IADL scores range from 0 to 8, with lower scores indicating greater dependence (31). The FAQ is a 10-item questionnaire that assesses tasks needed to live independently, including managing finances, assembling tax records or papers, playing a game or working on a hobby, preparing balanced meals, using the stove, shopping, remembering current events, paying attention to and understanding television or a book, remembering appointments, and traveling. Items are scored 0 (“independence”), 1 (“difficulty, but can complete without assistance”), 2 (“difficulty requiring assistance”), or 3 (“complete dependence”), with FAQ scores ranging from 0 to 30. A cut-point of 9 (dependent in three or more activities) indicates impaired function. The Health and Retirement Study Core Interview Questionnaire Section G assesses the total number dependences for six ADLs (bathing, dressing, walking, eating, getting in and out of bed, and toileting) and five IADLs (preparing a hot meal, shopping for groceries, making telephone calls, taking medications, and managing money) (52) with scores ranging from 0 (no assistance required) to 11 (assistance required in all areas).

Table 2.

Definitions of instrumental activities of daily living dependencies

| IADL Instrument | Study | Definitions of IADL Dependencies |

|---|---|---|

| Lawton IADL | Abelha et al. (40) | One or more dependencies: Total score 0 (completely dependent) to 7 (completely independent) for each of seven items |

| Bienvenu et al. (17) | IADL dependencies: No baseline dependency with ≥2 IADL dependencies at follow-up | |

| Remission: ≤2 IADL dependencies at any follow-up time and a decrease in number of dependencies of greater than the Reliable Change Index for this measure (i.e., needed a difference of ≥2 dependencies) | ||

| Boumendil et al. (39) | Total score from 0 (no limitation) to 4 (difficulties in all activities). Good functional status defined as ≤1 dependency | |

| Broslawski et al. (41) | Percentage of patients whose scores increased, showed no change, or decreased from pre-ICU to follow-up | |

| Chelluri et al. (43) | Total score: Scores range from 0 to 8. Higher score indicates more dependence | |

| Cox et al. (44) | Number of dependencies in IADL | |

| Daubin et al. (45) | Total scores: Scores range from 0 to 4. Scores of 0 (complete independence), 1 (dependent), and 4 (complete dependence) | |

| Haas et al. (46) | Decrease IADL score from pre-ICU function to follow-up | |

| Quality of Life after Mechanized Ventilation in the Elderly Study Investigators (48) | Total scores, with higher scores indicating more dependence | |

| Sacanella et al. (49) | Total score: Scores range from 0 to 8. A score of 8 denotes full autonomy in IADL | |

| Van Pelt et al. (50) | Total score: Scores range from 0 to 8 | |

| FAQ | Brummel et al. (42) | Total score: Range from 0 to 30. Scores ≥9 indicate impaired functioning |

| Jackson et al. (34) | ||

| Jackson et al. (47) | ||

| Jackson et al. (18) | ||

| Health and Retirement Study Care Questionnaire | Iwashyna et al. (2) | Total number of IADL and ADL deficiencies to create a total deficiency score (range, 0 to 11 [assistance in all categories]) |

Definition of abbreviations: ADL = activities of daily living; FAQ = Functional Activities Questionnaire; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; ICU = intensive care unit.

Definitions of Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Dependency

Definitions of IADL dependency varied widely between studies, even when identical IADL measures were used (Table 2). Scores for defining IADL dependency varied from a single category of dependency to absolute numeric scores. This variability made cross-study comparisons difficult, despite use of similar measures. These differences in IADL instruments and dependency definitions precluded meta-analysis of these data.

Pre-ICU Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Dependency

Twelve studies (75%) reported data on pre-ICU IADL dependency (2, 17, 18, 40, 42, 43, 45–47, 48–50) (Table 2), with results ranging from 7 to 85%, but nine studies did not report percentage for either pre- or post-IADL dependency. Pre-ICU IADL dependency was significantly associated with post-IADL dependency in two of 12 studies (16%) (18, 43). One study reported that mild or moderate pre-ICU IADL dependency correlated with post-ICU IADL dependency; however, this was not the case for severe pre-ICU IADL dependency (2). Pre-ICU IADL dependency was also associated with an increased risk of early death post-ICU (43, 48, 49).

Post-ICU Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Dependency

Eleven studies (69%) reported that survivors of critical illness experience new or worsening IADL dependencies (Table 1). Post-ICU IADL dependencies ranged from 5 to 70% at the furthest time point measured (17, 18, 39, 40, 42, 43, 45, 47, 50) (Table 1). Most studies did not describe the specific type of IADL dependencies. Using the Lawton IADL questionnaire, Bienvenu and colleagues (17) reported that survivors were dependent in the following IADL areas: 70% for housekeeping, 60% for shopping, 51% for traveling, 49% for doing laundry, 43% for preparing food, 42% for managing finances, 30% for medication management, and 10% for using the telephone. Using the FAQ, Jackson and colleagues reported that the greatest IADL dependencies occurred in memory, financial management, making travel arrangements, and traveling.

Risk Factors for Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Dependency

There were few consistent associations between risk factors and IADL dependency (Table 3; and see Table E1 in the online supplement). For example, three of five studies showed a positive association between older age and IADL dependency (18, 34, 46). One of three studies showed a positive association with ICU delirium and post-ICU IADL dependency (40). Both studies evaluating mechanical ventilation demonstrated an association between longer duration of mechanical ventilation and increased IADL dependency (44, 47).

Table 3.

Risk factors for instrumental activities of daily living dependencies

| Risk Factors | Total Studies (n) | Studies with No Association [n (%)] | Positive Association (Greater IADL Dependencies) [n (%)] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-ICU factors | |||

| Older age | 5 | 2 (40%) | 3 (60%) |

| Sex (male) | 1 | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) |

| Baseline IADL dependency | 4 | 0 (0%) | 4 (100%) |

| Baseline depression | 1 | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) |

| ICU factors | |||

| ICU delirium | 4 | 2 (50%) | 2 (50%) |

| ICU length of stay | 1 | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) |

| Illness severity | 1 | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation | 2 | 0 (0%) | 2 (100%) |

| Trauma admission | 1 | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) |

| Unplanned surgical or medical ICU admission | 1 | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) |

| Post-ICU factors | |||

| Post-ICU cognitive impairment | 1 | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) |

Definition of abbreviations: IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; ICU = intensive care unit.

Change in Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Dependency over Time

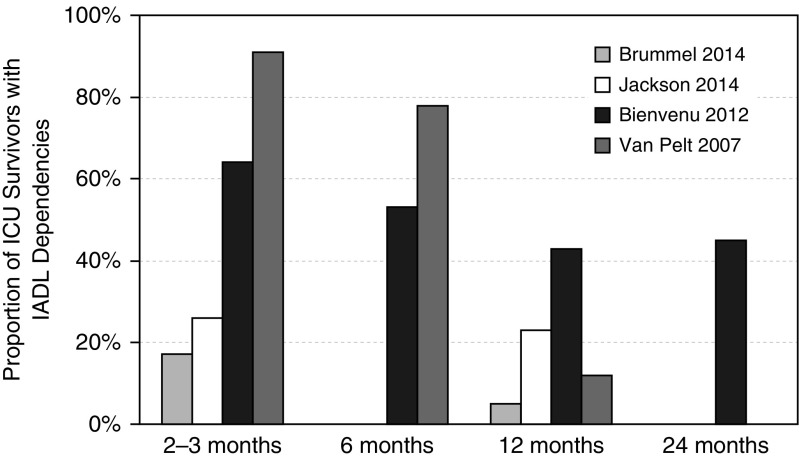

All studies reported an increase in IADL dependency from the pre- to post-ICU period (Table 4). Only four studies assessed post-IADL dependencies over time (17, 18, 42, 50). Of the four studies that monitored patients longitudinally, three reported a decrease in IADL dependencies, among survivors, over 12-month follow-up (17, 42, 50), and one reported no significant change (18) (Figure 2) One of these studies reported that IADL dependencies did not change from 12 to 24 months (17), suggesting that maximum improvement was achieved at 12 months. No studies demonstrated a return in post-ICU IADL dependencies to pre-ICU levels.

Table 4.

Change in instrumental activities of daily living dependency over time

| Study | IADL Instrument | Change in IADL Dependency over Time | Summary of Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abelha et al. (40) | Lawton IADL | Pre-ICU: 7% had at least 1 IADL dependency | Increase in IADL dependencies compared with pre-ICU |

| 6 mo: 19% had at least 1 IADL dependency | |||

| Bienvenu et al. (17) | Lawton IADL | IADL, ≥2 dependencies: | IADL dependencies decreased over time but are still present in many patients |

| 3 mo: 64% | |||

| 6 mo: 53% | |||

| 12 mo: 43% | |||

| 24 mo: 45% | |||

| Remission vs. no remission: | |||

| Remission in IADL dependency ∼1 in follow-up | |||

| No remission in IADL dependency ≥4 in follow-up | |||

| Broslawski et al. (41) | Lawton IADL | Change from pre-ICU to 6 mo | Majority of patients had no change or decrease in IADL dependencies compared with pre-ICU; some patients had increased IADL dependencies over time |

| 6 patients, scores declined | |||

| 21 patients, score stated the same or improved | |||

| Brummel et al. (42) | FAQ | 3 mo: 3 IADL deficiencies (range, 0–6); disability in IADL in 17% | Decrease in IADL dependence over 12 mo |

| 12 mo: 1 IADL deficiency (range, 0–5); disability in IADL in 5% | |||

| Cox et al. (44) | Lawton IADL | Pre-ICU admission: mean, 2.1; SD, 2.7 | Increase in IADL dependencies initially post-ICU compared with pre-ICU: Slight, but not significant decrease over time |

| 2 mo: mean, 5.7; SD, 2.1 | |||

| 6 mo: mean, 5.2; SD, 2.4 | |||

| 12 mo: mean, 4.8; SD, 2.6 | |||

| Daubin et al. (45) | Lawton IADL | No significant change from pre-ICU to 3-mo follow-up | Increase in IADL dependencies compared with pre-ICU early after ICU discharge, with no change over time |

| Pre-ICU: 40% completely independent and 7% completely dependent | |||

| Number of IADL dependencies: Pre-ICU: mean, 1.1; SD, 1.3 vs. 3-mo follow-up: mean, 2.9; SD, 1.4 (P = 0.62) | |||

| Iwashyna et al.* (2) | IADL using Health and Retirement Core Interview Questionnaire Section G | Pre-ICU: 43% with zero IADLs | Increase in IADL dependencies early after ICU discharge compared with pre-ICU; no change over time |

| First survey postsepsis (n = 623): same as baseline | |||

| Second survey postsepsis (n = 288): | |||

| 14% with zero IADLs | |||

| 32% with 0.5 IADLs | |||

| 53% with 3 IADLs | |||

| Third survey postsepsis (n = 98): | |||

| 14% with zero IADLs | |||

| 29% with 0.5 IADLs | |||

| 57% with 3 IADLs | |||

| Jackson et al. (18) | FAQ | 3 mo: 56% of patients with prior IADL disability had disability versus 23% with new IADL disability (9.5 vs. 2.2 IADLs) | New disability in IADL compared with pre-ICU for some patients; no significant change over time |

| 12 mo: 62% of patients with prior IADL disability had disability versus 20% with new IADL disability (10.0 vs. 2.0 IADLs) | |||

| Quality of Life after Mechanized Ventilation in the Elderly Study Investigators (48) | Lawton IADL | Pre-ICU IADL scores: | Increase in IADL dependencies compared with pre-ICU |

| Median = 1 for overall group (survivors and nonsurvivors) | |||

| Median = 4 for nonsurvivors | |||

| Post-ICU IADL scores: | |||

| Median = 4 for patient interview (n = 132) | |||

| Median = 7 for proxy interview (n = 98) | |||

| Sacanella et al. (49) | Lawton IADL | IADL scores: | Slight decrease in IADL dependencies compared with pre-ICU; still significantly disabled in IADL dependencies; no change over time |

| Pre-ICU: mean, 6.7; SD, 1.7 | |||

| 3 mo: mean, 5.2; SD, 1.7 | |||

| 6 mo: mean, 5.6; SD, 1.6 | |||

| 12 mo: mean, 5.3; SD, 2.6 | |||

| Van Pelt et al. (50) | Lawton IADL | Pre-ICU functional dependency: 42% | Increase in IADL dependency compared with pre-ICU with some decrease over time |

| 2 mo: 91% with functional dependency | |||

| 6 mo: 78% with functional dependency at 6 mo | |||

| 12 mo: 70% had functional dependency at 12 mo |

Definition of abbreviations: FAQ = Functional Activities Questionnaire; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; ICU = intensive care unit.

Figure 2.

Change in instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) over time. Summarized are the four studies that longitudinally evaluated IADL dependencies in intensive care unit survivors. Sample sizes at each available time point, respectively: Brummel et al. (42): 76, 55; Jackson et al. (18): 422, 372; Bienvenu et al. (17): 161, 169, 152, 142; and Van Pelt et al. (50): 169 at all three time points. ICU = intensive care unit.

Discussion

This systematic review demonstrates that a large number of ICU survivors (69%) experience new or worsening IADL dependencies after critical illness. The time to follow-up was variable, and most studies were single-center cohort studies. In 75% of longitudinal studies, IADL dependencies decreased over time but did not return to pre-ICU level (17, 18, 42, 50). Pre-IADL dependencies were present in 7–85% of patients and were associated with increased risk of post-ICU IADL dependency (18, 43, 44). Pre-ICU IADL dependency was also associated with an increased risk of early death post-ICU (43, 48, 49). Although a majority of studies report new post-ICU IADL dependencies there was significant variability in the incidence and definitions of IADL dependency despite use of the same instruments across studies. The wide range of definitions of IADL disability, variability in follow-up times, and lack of reporting actual scores, including domain scores, are problematic (53). There is little agreement on the quality of IADL instruments (54) and direct comparisons of IADL instruments in ICU populations have not been done. Uniformity in instruments and consistent reporting of data are essential for accurate interpretation and comparison of findings across studies. In other populations, variability in the incidence of IADL disability has been reported across instruments. For example, one study assessed functional status and mild cognitive impairment using three different IADL measures (Lawton and Brody IADL, Scales for Independent Behavior-Revised, and Everyday Problems Test) and found the results differed based on which IADL instrument was used (55).

Only two studies reported data on the individual domains of IADL function. Data on the type and severity of specific functional impairments is required to develop appropriate interventions. Four studies longitudinally assessed IADL dependency, with all four demonstrating a decrease in dependencies over time in the majority of survivors (17, 18, 42, 50), but these studies did not report a standardized cutoff or minimal important difference, and little change was noted from 12 to 24 months in a single study (17). Studies to determine the minimal important clinical difference for IADL instruments in survivors of critical illness are needed.

Our review suggests that various risk factors may increase ICU survivors’ risk of post-ICU IADL dependencies, but there were few consistent associations with any of the variables reported. For example, older age was associated with post-ICU IADL dependency in three studies (18, 43, 46), whereas two studies did not find a similar relationship (41, 49). IADL dependency was not consistently associated with illness severity or other markers of critical illness. This lack of consistent association may be because some studies were underpowered to demonstrate significant associations with pre-ICU or ICU factors and IADL dependency. Finally, pre-IADL dependency was associated with an increased risk of death after ICU discharge (43, 48, 49).

We found that delirium, and post-ICU cognitive and functional impairments, are variably associated with post-ICU IADL dependency, as one study demonstrated increased IADL dependency (40) and two demonstrated no relationship (18, 42). Delirium is a reported risk factor for IADL dependency in other populations. For example, in a prospective cohort study of patients undergoing cardiac surgery, postoperative delirium was independently associated with IADL decline at 1- and 12-month follow-up after adjusting for age, comorbidity, baseline function, and cognitive function (56). The lack of consistent association may relate to the limited number of small cohort studies that have evaluated the relationship between delirium and IADL dependency.

Cognitive impairment adversely affects independent performance of IADLs, especially in areas such as shopping, food preparation, use of public transportation, and management of medications and finances. Only one study assessed the relationship between cognitive impairments and post-ICU IADL dependency and found that 22% of ICU survivors had IADL dependencies that were associated with cognitive impairment (34). This finding parallels previous reports in non-ICU populations, particularly the elderly. For instance, in mild Alzheimer’s disease, executive dysfunction is a key contributor to IADL dependence after accounting for memory impairment (57). In elderly community-dwelling individuals, cognitive impairment was associated with IADL dependence, and worse cognitive function was associated with higher dependence and had a greater impact on independence (58). Better cognitive function was associated with fewer IADL dependencies in 1,095 healthy nondemented community dwellers (59). Finally, a study of hospitalized patients found that a one-point worse score on a cognitive screening test was associated with a 1.5-fold increase in development of new IADL dependencies (60). Assessment of functional dependence should be a research priority given the large numbers of ICU survivors that develop cognitive impairments.

The association of physical, cognitive, and psychological deficits with a patient’s ability to function independently and resume daily function has received little attention until recently. Including IADLs as an outcome may aid evaluating a person’s ability to function independently. Instruments for IADL assessment are validated in other patient populations and easy to administer. The choice of instrument in the studies reviewed was variable, but we recommend the Lawton IADL instrument as it has good psychometric properties, is widely used in a variety of populations (e.g., healthy aging, dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), is easy to administer, can be administered by phone, and can be administered to proxies with good correlation with patient responses (30, 43, 61).

There are important limitations in the available literature. Some of the studies did not report both pre- and post-ICU IADL dependencies, which may be critical for evaluating recovery trajectories. Reporting of IADLs varied between the studies, and few studies reported individual IADL disabilities. That there were only a small number of studies that assessed IADL functioning (16, out of hundreds of studies that have explored post-ICU outcomes in the last 2 decades) is surprising and noteworthy, as from a patient and caregiver vantage point functional ability rivals cognitive or psychological ability in importance. Clinically oriented measures of strength, cognition, and psychiatric symptoms commonly evaluated by critical care investigators do not necessarily have a strong correlation with functional outcomes (62, 63). Needham and colleagues found that muscle strength impairments were significantly less than impairments in 6-minute walk distance or the SF-36 Physical Function self-reported outcome, reinforcing that factors other than muscle weakness contribute to poor physical functioning (10). Restoration of function, rather than an increase in muscle strength, may be what matters most to patients.

Research on IADLs and other functional outcomes should include consistency in the following areas: methods of evaluating functional outcomes, follow-up times, and definitions of IADL dependency. IADL reporting often is patient-based reporting, which may have limitations. Other methods are feasible, including direct assessment and proxy-based reporting. Direct assessment of functional status is an approach used in more traditional rehabilitation contexts, in which IADLs are assessed via direct observation of task performance (e.g., cooking, managing finances, etc.) as opposed to patient self-report on their adeptness at these tasks, which is often limited by patient lack of awareness or cognitive impairment. Such an approach would require in-person assessment, and may not always be feasible. Alternatively, proxy-based reporting may provide additional information that assists in assessment of patient cognitive impairment and correlates with patient reports (43). Future studies should also assess cognitive and psychiatric functioning (depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder) and their association with IADL dependency in ICU populations. As existing research (R24HL111895; see www.improvelto.com) progresses with development of a minimum “core outcome set” (64, 65, 66) of measures used for all important outcome domains in all research studies evaluating patients postdischarge, this type of future research may be more feasible.

Conclusions

We identified only 16 studies evaluating IADL dependency in survivors of critical illness. Even when the same widely used, reliable, and valid instrument was used, comparisons between studies were difficult because of variable definitions of IADL dependency. New or worsening IADL dependency was present and persisted months to years after ICU discharge for most survivors. There was little evidence supporting any consistent association of risk factors with IADL dependency. Longitudinal data are sparse; hence, trajectories of IADL recovery are difficult to interpret. The relationship between cognitive impairment and IADL dependencies, which has been consistently reported in other populations, is lacking in studies of ICU survivors. Studies with rigorous methods are necessary to assess whether interventions will alter IADL dependency in ICU survivors.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI; R24HL111895) (D.M.N.); B.B.K. received funding from a Career Development Award from the UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI) NIH/National Center for Advanced Translational Science (NCATS) (UCLA UL1TR000124 and UL1TR001881).

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: R.O.H., M.R.S.; analysis and interpretation: R.O.H, M.R.S., B.B.K., E.D., D.M.N.; drafting the manuscript for important intellectual content: R.O.H, M.R.S., B.B.K., J.C.J., D.M.N.; final approval of the version to be published: R.O.H, M.R.S., B.B.K., E.D., J.C.J., D.M.N.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Angus DC, Carlet J 2002 Brussels Roundtable Participants. Surviving intensive care: a report from the 2002 Brussels Roundtable. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:368–377. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1624-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DM, Langa KM. Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA. 2010;304:1787–1794. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubenfeld GD, Herridge MS. Epidemiology and outcomes of acute lung injury. Chest. 2007;131:554–562. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuthbertson BH, Roughton S, Jenkinson D, Maclennan G, Vale L. Quality of life in the five years after intensive care: a cohort study. Crit Care. 2010;14:R6. doi: 10.1186/cc8848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desai SV, Law TJ, Needham DM. Long-term complications of critical care. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:371–379. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181fd66e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matté A, Tomlinson G, Diaz-Granados N, Cooper A, Guest CB, Mazer CD, Mehta S, Stewart TE, et al. Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1293–1304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hopkins RO, Weaver LK, Collingridge D, Parkinson RB, Chan KJ, Orme JF., Jr Two-year cognitive, emotional, and quality-of-life outcomes in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:340–347. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-763OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson JC, Hart RP, Gordon SM, Shintani A, Truman B, May L, Ely EW. Six-month neuropsychological outcome of medical intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1226–1234. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000059996.30263.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Needham DM, Dinglas VD, Bienvenu OJ, Colantuoni E, Wozniak AW, Rice TW, Hopkins RO NIH NHLBI ARDS Network. One year outcomes in patients with acute lung injury randomised to initial trophic or full enteral feeding: prospective follow-up of EDEN randomised trial. BMJ. 2013;346:f1532. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Needham DM, Dinglas VD, Morris PE, Jackson JC, Hough CL, Mendez-Tellez PA, Wozniak AW, Colantuoni E, Ely EW, Rice TW, et al. NIH NHLBI ARDS Network. Physical and cognitive performance of patients with acute lung injury 1 year after initial trophic versus full enteral feeding: EDEN trial follow-up. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:567–576. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201304-0651OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elliott D, Davidson JE, Harvey MA, Bemis-Dougherty A, Hopkins RO, Iwashyna TJ, Wagner J, Weinert C, Wunsch H, Bienvenu OJ, et al. Exploring the scope of post-intensive care syndrome therapy and care: engagement of non-critical care providers and survivors in a second stakeholders meeting. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:2518–2526. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, Hopkins RO, Weinert C, Wunsch H, Zawistowski C, Bemis-Dougherty A, Berney SC, Bienvenu OJ, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:502–509. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozge C, Ozge A, Unal O. Cognitive and functional deterioration in patients with severe COPD. Behav Neurol. 2006;17:121–130. doi: 10.1155/2006/848607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tuokko H, Morris C, Ebert P. Mild cognitive impairment and everyday functioning in older adults. Neurocase. 2005;11:40–47. doi: 10.1080/13554790490896802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan E, Dowdy DW, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez PA, Sevransky JE, Shanholtz C, Himmelfarb CR, Desai SV, Ciesla N, Herridge MS, et al. Physical complications in acute lung injury survivors: a two-year longitudinal prospective study. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:849–859. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poulsen JB, Møller K, Kehlet H, Perner A. Long-term physical outcome in patients with septic shock. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:724–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.01921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bienvenu OJ, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez PA, Dinglas VD, Shanholtz C, Husain N, Dennison CR, Herridge MS, Pronovost PJ, Needham DM. Depressive symptoms and impaired physical function after acute lung injury: a 2-year longitudinal study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:517–524. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0503OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Brummel NE, Thompson JL, Hughes CG, Pun BT, Vasilevskis EE, Morandi A, Shintani AK, et al. Bringing to Light the Risk Factors and Incidence of Neuropsychological Dysfunction in ICU Survivors (BRAIN-ICU) Study Investigators. Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and functional disability in survivors of critical illness in the BRAIN-ICU Study: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:369–379. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70051-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kowalczyk M, Nestorowicz A, Fijałkowska A, Kwiatosz-Muc M. Emotional sequelae among survivors of critical illness: a long-term retrospective study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2013;30:111–118. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e32835dcc45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabiee A, Nikayin S, Hashem MD, Huang M, Dinglas VD, Bienvenu OJ, Turnbull AE, Needham DM. Depressive symptoms after critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:1744–1753. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bienvenu OJ, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez PA, Shanholtz C, Dennison-Himmelfarb CR, Pronovost PJ, Needham DM. Cooccurrence of and remission from general anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms after acute lung injury: a 2-year longitudinal study. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:642–653. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cuthbertson BH, Hull A, Strachan M, Scott J. Post-traumatic stress disorder after critical illness requiring general intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:450–455. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-2004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jackson JC, Hart RP, Gordon SM, Hopkins RO, Girard TD, Ely EW. Post-traumatic stress disorder and post-traumatic stress symptoms following critical illness in medical intensive care unit patients: assessing the magnitude of the problem. Crit Care. 2007;11:R27. doi: 10.1186/cc5707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parker AM, Sricharoenchai T, Raparla S, Schneck KW, Bienvenu OJ, Needham DM. Posttraumatic stress disorder in critical illness survivors: a metaanalysis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:1121–1129. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackson JC, Archer KR, Bauer R, Abraham CM, Song Y, Greevey R, Guillamondegui O, Ely EW, Obremskey W. A prospective investigation of long-term cognitive impairment and psychological distress in moderately versus severely injured trauma intensive care unit survivors without intracranial hemorrhage. J Trauma. 2011;71:860–866. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182151961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rasovska H, Rektorova I. Instrumental activities of daily living in Parkinson’s disease dementia as compared with Alzheimer’s disease: relationship to motor disability and cognitive deficits: a pilot study. J Neurol Sci. 2011;310:279–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization. World Health Organization international classification of functioning. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farias ST, Mungas D, Reed BR, Harvey D, Cahn-Weiner D, Decarli C. MCI is associated with deficits in everyday functioning. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20:217–223. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000213849.51495.d9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jefferson AL, Byerly LK, Vanderhill S, Lambe S, Wong S, Ozonoff A, Karlawish JH. Characterization of activities of daily living in individuals with mild cognitive impairment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:375–383. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318162f197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gold DA. An examination of instrumental activities of daily living assessment in older adults and mild cognitive impairment. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2012;34:11–34. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2011.614598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jagger C, Matthews R, Matthews F, Robinson T, Robine JM, Brayne C Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study Investigators. The burden of diseases on disability-free life expectancy in later life. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:408–414. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.4.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wedding U, Röhrig B, Klippstein A, Pientka L, Höffken K. Age, severe comorbidity and functional impairment independently contribute to poor survival in cancer patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2007;133:945–950. doi: 10.1007/s00432-007-0233-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jackson JC, Obremskey W, Bauer R, Greevy R, Cotton BA, Anderson V, Song Y, Ely EW. Long-term cognitive, emotional, and functional outcomes in trauma intensive care unit survivors without intracranial hemorrhage. J Trauma. 2007;62:80–88. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31802ce9bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reeve BB, Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Cook KF, Crane PK, Teresi JA, Thissen D, Revicki DA, Weiss DJ, Hambleton RK, et al. PROMIS Cooperative Group Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Med Care 2007455, Suppl 1S22–S31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rothrock NE, Hays RD, Spritzer K, Yount SE, Riley W, Cella D. Relative to the general US population, chronic diseases are associated with poorer health-related quality of life as measured by the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1195–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheung AM, Tansey CM, Tomlinson G, Diaz-Granados N, Matté A, Barr A, Mehta S, Mazer CD, Guest CB, Stewart TE, et al. Two-year outcomes, health care use, and costs of survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:538–544. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200505-693OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boumendil A, Maury E, Reinhard I, Luquel L, Offenstadt G, Guidet B. Prognosis of patients aged 80 years and over admitted in medical intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:647–654. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-2150-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abelha FJ, Luís C, Veiga D, Parente D, Fernandes V, Santos P, Botelho M, Santos A, Santos C. Outcome and quality of life in patients with postoperative delirium during an ICU stay following major surgery. Crit Care. 2013;17:R257. doi: 10.1186/cc13084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Broslawski GE, Elkins M, Algus M. Functional abilities of elderly survivors of intensive care. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1995;95:712–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brummel NE, Girard TD, Ely EW, Pandharipande PP, Morandi A, Hughes CG, Graves AJ, Shintani A, Murphy E, Work B, et al. Feasibility and safety of early combined cognitive and physical therapy for critically ill medical and surgical patients: the Activity and Cognitive Therapy in ICU (ACT-ICU) trial. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:370–379. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-3136-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chelluri L, Im KA, Belle SH, Schulz R, Rotondi AJ, Donahoe MP, Sirio CA, Mendelsohn AB, Pinsky MR. Long-term mortality and quality of life after prolonged mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:61–69. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000098029.65347.F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cox CE, Carson SS, Lindquist JH, Olsen MK, Govert JA, Chelluri L Quality of Life after Mechanical Ventilation in the Aged (QOL-MV) Investigators. Differences in one-year health outcomes and resource utilization by definition of prolonged mechanical ventilation: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2007;11:R9. doi: 10.1186/cc5667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Daubin C, Chevalier S, Séguin A, Gaillard C, Valette X, Prévost F, Terzi N, Ramakers M, Parienti JJ, du Cheyron D, et al. Predictors of mortality and short-term physical and cognitive dependence in critically ill persons 75 years and older: a prospective cohort study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:35. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haas JS, Teixeira C, Cabral CR, Fleig AH, Freitas AP, Treptow EC, Rizzotto MI, Machado AS, Balzano PC, Hetzel MP, et al. Factors influencing physical functional status in intensive care unit survivors two years after discharge. BMC Anesthesiol. 2013;13:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-13-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jackson JC, Ely EW, Morey MC, Anderson VM, Denne LB, Clune J, Siebert CS, Archer KR, Torres R, Janz D, et al. Cognitive and physical rehabilitation of intensive care unit survivors: results of the RETURN Randomized Controlled Pilot Investigation. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:1088–1097. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182373115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Quality of Life after Mechanized Ventilation in the Elderly Study Investigators. 2-month mortality and functional status of critically ill adult patients receiving prolonged mechanical ventilation. Chest. 2002;121:549–558. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.2.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sacanella E, Pérez-Castejón JM, Nicolás JM, Masanés F, Navarro M, Castro P, López-Soto A. Functional status and quality of life 12 months after discharge from a medical ICU in healthy elderly patients: a prospective observational study. Crit Care. 2011;15:R105. doi: 10.1186/cc10121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van Pelt DC, Milbrandt EB, Qin L, Weissfeld LA, Rotondi AJ, Schulz R, Chelluri L, Angus DC, Pinsky MR. Informal caregiver burden among survivors of prolonged mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:167–173. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-493OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH, Jr, Chance JM, Filos S. Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol. 1982;37:323–329. doi: 10.1093/geronj/37.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fonda S, Regula Herzog A HRS Health Working Group. HRS/AHEAD Documentation Report: Documentation of physical functioning measured in the Health and Retirement Study and the Asset and Health Dynamics among the Oldest Old Study. Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center, University of Michigan; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Andresen EM, Fouts BS, Romeis JC, Brownson CA. Performance of health-related quality-of-life instruments in a spinal cord injured population. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80:877–884. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sikkes SA, de Lange-de Klerk ES, Pijnenburg YA, Scheltens P, Uitdehaag BM. A systematic review of Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scales in dementia: room for improvement. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:7–12. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.155838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Vaconcelos Torres G, Araújo dos Reis L, Araújo dos Reis L. Assessment of functional capacity in elderly residents of an outlying area in the hinterland of Bahia/Northeast Brazil. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2010;68:39–43. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2010000100009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Burton CL, Strauss E, Bunce D, Hunter MA, Hultsch DF. Functional abilities in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Gerontology. 2009;55:570–581. doi: 10.1159/000228918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hsieh SJ, Ely EW, Gong MN. Can intensive care unit delirium be prevented and reduced? Lessons learned and future directions. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10:648–656. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201307-232FR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rudolph JL, Inouye SK, Jones RN, Yang FM, Fong TG, Levkoff SE, Marcantonio ER. Delirium: an independent predictor of functional decline after cardiac surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:643–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02762.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marshall JC.Inflammation, coagulopathy, and the pathogenesis of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome Crit Care Med 2001297, SupplS99–S106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Millán-Calenti JC, Tubío J, Pita-Fernández S, Rochette S, Lorenzo T, Maseda A. Cognitive impairment as predictor of functional dependence in an elderly sample. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;54:197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cromwell DA, Eagar K, Poulos RG. The performance of Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale in screening for cognitive impairment in elderly community residents. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:131–137. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00599-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zisberg A, Sinoff G, Agmon M, Tonkikh O, Gur-Yaish N, Shadmi E. Even a small change can make a big difference: the case of in-hospital cognitive decline and new IADL dependency. Age Ageing. 2016;45:500–504. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afw063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weinberger M, Samsa GP, Schmader K, Greenberg SM, Carr DB, Wildman DS. Comparing proxy and patients’ perceptions of patients’ functional status: results from an outpatient geriatric clinic. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:585–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb02107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dinglas VD, Hopkins RO, Wozniak AW, Hough CL, Morris PE, Jackson JC, Mendez-Tellez PA, Bienvenu OJ, Ely EW, Colantuoni E, et al. One-year outcomes of rosuvastatin versus placebo in sepsis-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: prospective follow-up of SAILS randomised trial. Thorax. 2016;71:401–410. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-208017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Needham DM, Yang T, Dinglas VD, Mendez-Tellez PA, Shanholtz C, Sevransky JE, Brower RG, Pronovost PJ, Colantuoni E. Timing of low tidal volume ventilation and intensive care unit mortality in acute respiratory distress syndrome: a prospective cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:177–185. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201409-1598OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Blackwood B, Marshall J, Rose L. Progress on core outcome sets for critical care research. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2015;21:439–444. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.