Abstract

Bacteria have developed various mechanisms by which they sense, interact, and kill other bacteria, in an attempt to outcompete one another and survive. Here we show that Bacillus subtilis can kill and prey on Bacillus megaterium. We find that Bacillus subtilis rapidly inhibits Bacillus megaterium growth by delivering the tRNase toxin WapA. Furthermore, utilizing the methionine analogue L-azidohomoalanine as a nutrient reporter, we provide evidence of nutrient extraction from Bacillus megaterium by Bacillus subtilis. Toxin delivery and nutrient extraction occur in a contact-dependent manner, and both activities are abolished in the absence of the phosphodiestrase YmdB, shown previously to mediate intercellular nanotube formation. Furthermore, we detect the localization of WapA molecules to nanotubes. Thus, we propose that Bacillus subtilis utilizes the same nanotube apparatus in a bidirectional manner, delivering toxin and acquiring beneficial cargo, thereby maximally exploiting potential niche resources.

Bacteria can exchange nutrients and macromolecules through tubular membranous structures called nanotubes. Here, the authors show that Bacillus subtilis can kill and prey on Bacillus megaterium by delivering a toxin and extracting nutrients in a nanotube-dependent manner.

Introduction

In natural microbial communities, each bacterium possesses an array of mechanisms designed to constantly interact with its microbial neighbors. While some mechanisms can act from afar, enabling the delivery of antimicrobial compounds into the shared milieu (e.g., quorum sensing, antibiotic production, membrane vesicle release), others require a tight physical connection between the interacting cells (e.g; refs. 1–3). A well studied example for contact mediated interaction is the type VI secretion system, which plays a key role both in bacterial competition and in bacterial infection. This system assembles as a tubular puncturing device, through which bacteria can deliver toxic molecules directly into prokaryotic or eukaryotic target cells4. Another strategy of intercellular interaction is exemplified by the contact-dependent inhibition phenomenon. In this mode, cells inhibit growth of their neighbors using a system, which comprises an outer-membrane toxin protein, its corresponding transporter and a cognate immunity protein5, 6. The diversity and complexity of direct intercellular interaction systems emphasizes the multiple strategies employed by bacteria to interact with their surroundings.

Some contact-dependent mechanisms are designed not necessarily to actively inhibit rivals, but rather to insure the bacterium’s own survival by exchanging vital compounds between the cells (e.g; refs. 7, 8). We have previously shown that such communication can be mediated by the production of small ‘tube-like’ membranous structures, formed among adjacent bacterial cells, which we previously termed nanotubes9. Utilizing the Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis (Bs) as a model organism, we demonstrated that nanotubes can allow for intercellular transfer of cytoplasmatic molecules from one bacterium to another, resulting in transient acquisition of nonhereditary antibiotic resistance. Cryo-EM analysis further revealed that nanotubes are composed of chains of membranous segments harboring a continuous lumen10. Similar membranous structures were implicated in long range extracellular electron transport in Shewanella oneidensis MR-111. In addition, two recent studies have shown that the bacterial pairs Acinetobacter baylyi and Escherichia coli, as well as Clostridium acetobutylicum and Desulfovibrio vulgaris, can cross feed each other in the absence of vital nutrients, utilizing nanotube-like structures12, 13.

Here we show that Bs delivers the WapA toxin to, and extracts nutrient from Bacillus megaterium (Bm), which we interpret as two parallel strategies to acquire territory and nutrients. We further present evidence that these predatory activities are contact-dependent and require the phosphodiesterase YmdB, previously shown to be required for nanotube formation10.

Results

Bs inhibits Bm growth in a contact-dependent manner

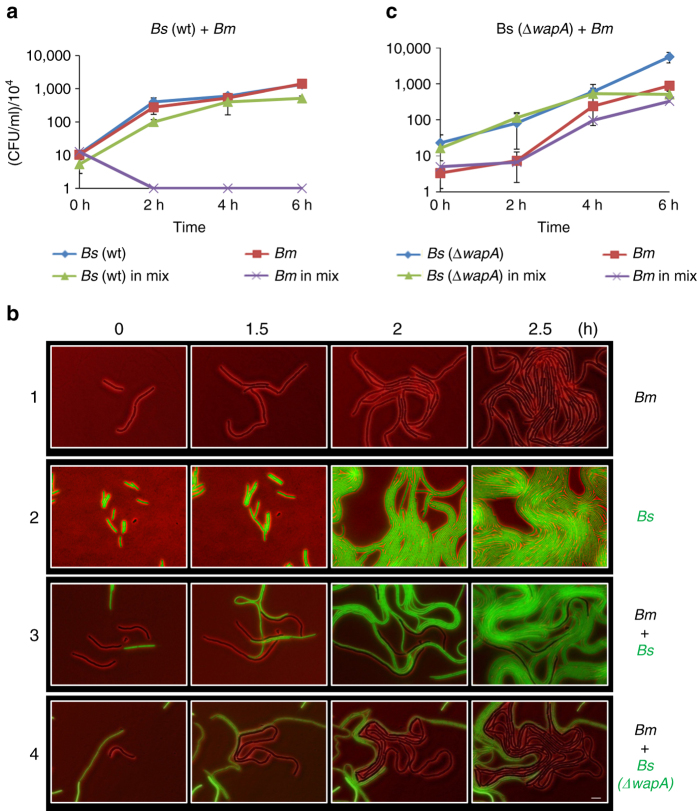

To study how different species impact each other, we examined the interaction between the soil bacterium Bs PY7914 and natural soil isolate bacteria. We enriched for spore forming bacteria derived from a soil niche, and the isolated strains were identified using 16S rDNA analysis. Among the isolated strains was Bm, which henceforth was utilized for interspecies analysis. We first carried out a competition assay, in which Bs was co-cultured with the wild isolate Bm in liquid medium (1:1 ratio), and growth was followed by colony forming units (CFUs). Due to their distinct morphological differences, the colonies of the two Bacillus species could be easily distinguished (Supplementary Fig. 1A). We found that Bm failed to form colonies after merely 2 h of co-incubation (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Fig. 1B), indicating that Bs greatly inhibits its growth, although when grown separately the two Bacilli exhibit a very similar growth rate (Supplementary Fig. 1C). To further analyze the antagonistic effect produced by Bs, we examined the consequence of growing Bm and GFP labeled Bs on a solid surface, in a confined space, using time lapse fluorescence microscopy. We observed that when Bs encounters Bm, an abrupt halt of Bm growth and division occurs, culminating with Bs occupying the majority of the field (Fig. 1b, 1–3), consistent with the CFU viability assay (Fig. 1a). To further inspect the observed Bm growth halt, we supplemented the medium with propidium iodide (PI), which preferentially penetrates and stains cells that lost their membrane integrity. The analysis revealed that the inhibited Bm cells remained unstained, indicating that they did not lyse and maintained an intact membrane (Supplementary Fig. 2). As a comparison, damaging specific cells using highly accurate laser ablation was followed by PI accumulation in the irradiated cells (Supplementary Fig. 2)15.

Fig. 1.

Bm inhibition by Bs is mediated by the WapA toxin. a Bs (PY79, wt) and Bm (OS2) were grown separately or in a mixture in LB medium at 37 °C. Cells were plated for CFUs at the indicated time points. Each point represents an average value and s.d. of three independent experiments. b Representative time lapse microscopy images of (1) Bm (OS2), (2) Bs (AR16: amyE::PrrnE -gfp), (3) a mixture of Bm (OS2) and Bs (AR16), and (4) a mixture of Bm (OS2) and Bs (OS24: ΔwapA, sacA::Pveg-mCherry). Shown are overlay fluorescence from GFP or mCherry (green) and phase contrast (red) images, captured at the indicated time points. Bm cells are shown in black while Bs cells are shown in green. Scale bar represents 5 µm. c Bs (OS16::ΔwapA) and Bm (OS2) were grown separately or in a mixture and processed as in a. Each point represents an average value and s.d. of three independent experiments

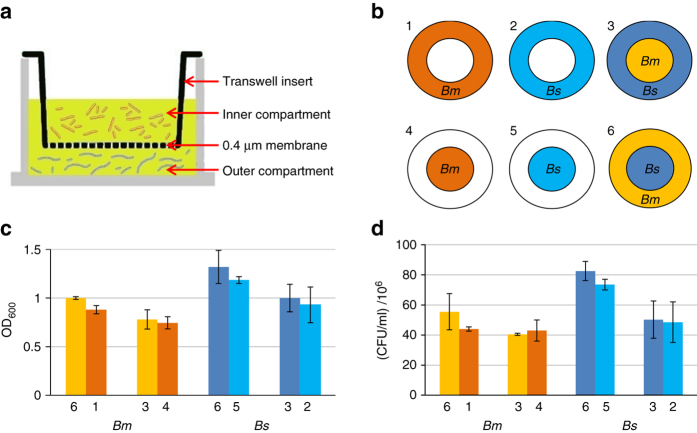

To examine the nature of the observed inhibition, we aimed to determine if it is mediated by an antagonistic factor secreted into the medium, or requires direct cell to cell contact. To address this question, the two Bacilli were placed in a Transwell plate, consisting of double chambered wells, separated by a membrane. The membrane allows the passage of small molecules, while the cells remain compartmentalized (Figs. 2a, b). Following OD600 and CFU values for Bm and Bs, located at the different compartments, revealed that Bm growth was not affected by the presence of Bs in the adjacent chamber, even after 6 h of co-growth (Figs. 2c, d). However, when Bm and Bs were co-incubated in the same compartment Bm growth inhibition was restored (Supplementary Fig. 3A). These results indicate that inhibition of Bm by Bs is not due to an antagonistic molecule secreted into the shared medium, but rather demands physical contact for its occurrence.

Fig. 2.

Bs inhibits Bm growth in a contact-dependent manner. a Illustration of a single Transwell chamber. The medium is shared between the inner and outer compartments, while the cells cannot pass the 0.4 μm membrane barrier. b Bs (PY79) and Bm (OS2) cells were grown in Transwell chambers containing LB as indicated by the layout. Compartments containing Bs are shown in blue hues, while compartments containing Bm are shown in yellow hues. White circles represent compartments containing LB only. c, d Shown are OD600 (c) and CFUs (d) of cells grown in Transwell chambers for 6 h. The numbers and colors correspond to the layout described in b. Each column represents an average value and s.d. of three independent experiments

Bs toxicity is mediated by delivery of WapA toxin to Bm

We next searched for potential toxins encoded by Bs that could cause Bm growth inhibition. It has been previously reported that Bs encodes a wapA-wapI toxin-antitoxin module, in which the WapA toxin was found to cleave tRNases, perturbing translation. WapA was shown to act in an intercellular contact-dependent manner, causing toxicity to neighboring Bs cells lacking the protective antitoxin16. We therefore reasoned that WapA could also act in an interspecies manner, accounting for the Bs toxic activity against Bm. To test this idea, we conducted a liquid competition assay between Bs, lacking wapA, and Bm. Indeed, Bs mutant cells failed to inhibit Bm growth as indicated by the increase of Bm CFU in the mixed culture (Fig. 1c). Consistently, following the growth of Bm and Bs (∆wapA) by time lapse microscopy revealed that Bm was indeed able to grow in the presence of the mutant Bs (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, introducing the Bs wapI antitoxin gene into Bm conferred full immunity to Bm in mixed cultures (Supplementary Fig. 3B, C). Taken together, our results are consistent with the view that Bs inhibits growth of the wild Bm isolate in a contact-dependent manner by delivering the WapA toxin.

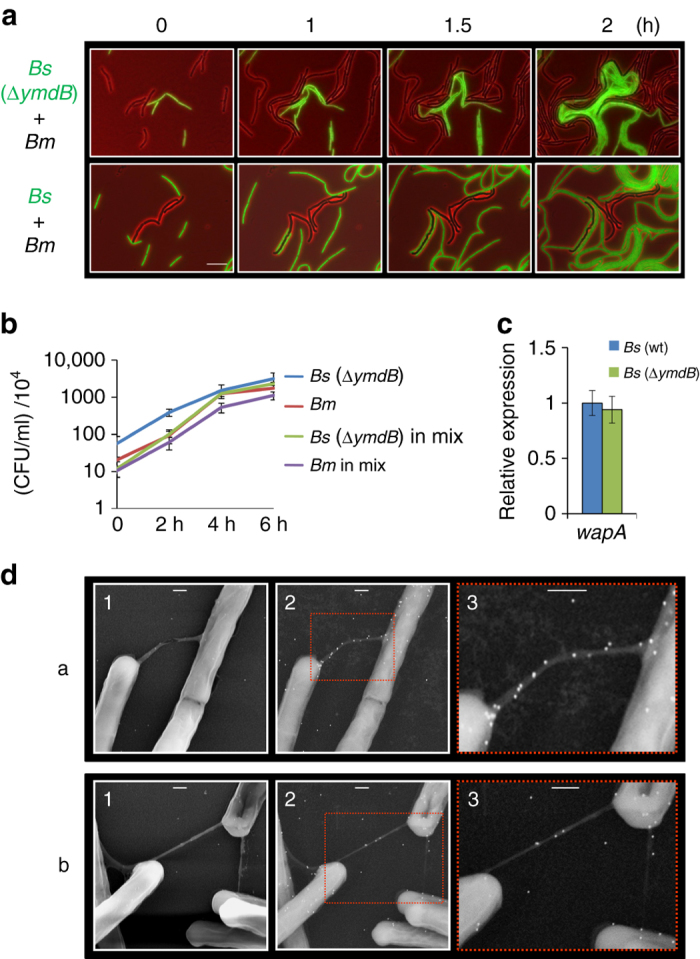

Bm inhibition by Bs is YmdB-mediated

We next searched for additional potential genes encoded by Bs that could be involved in the Bs-Bm interspecies interaction. We reasoned that mutants in such gene(s) would fail to inhibit Bm growth, similarly to the Bs mutant lacking wapA. We conducted a screen using different Bs mutants, lacking a potential gene or genes that might prove accountable for the inhibition. Our survey included 27 mutants (Supplementary Table 1) deficient mainly in biofilm formation (e.g, tasA, sinI, sinR, ymdB), chemotaxis (sigD), membrane metabolism (e.g, ywnE, yerQ, psd), as well as a mutant lacking the major developmental regulator Spo0A. Each of the investigated mutant strains was mixed with Bm, and growth was inspected using time lapse microscopy. Our screen revealed that only the ymdB mutant failed to inhibit Bm growth (Fig. 3a), yielding results similar to that of the wapA mutant (Fig. 1b). Consistent with the microscopy screen, ymdB mutant failed to inhibit Bm growth when grown similarly in liquid LB medium (Fig. 3b). YmdB, a conserved calcineurin-like phosphodiesterase, was previously shown using microarray analysis to affect the mRNA levels of multiple genes; however, no modifcation in wapA transcript level was detected17, 18. We re-examined this possibility utilizing quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) and fluorescence from PwapA-GFP reporter. Both methods confirmed that ymdB does not influence wapA expression levels (Fig. 3c; Supplementary Fig. 4A). YmdB has been previously implicated in biofilm formation18, and was shown by our laboratory to be required for cAMP production, proper colony development, and the formation of intercellular nanotubes10, 15. Furthermore, WapA protein was previously detected in the nanotube enriched biochemical fraction10. To investigate the possibility that WapA is directly associated with nanotubes, Bs cells harboring WapA tagged with HA (human influenza hemagglutinin) epitope, were subjected to non-coated immuno- High Resolution Scanning Electron Microscopy (HR-SEM) analysis utilizing anti-HA antibodies and gold-labeled secondary antibodies. Indeed, WapA molecules were detected along intercellular nanotubes branching from cells and were also scattered over the cell surface (Fig. 3d). The immuno-gold signal was not detectable from cells or nanotubes of Bs lacking HA-tagged WapA (Supplementary Fig. 4B). Thus, our data support the view that ymdB is required for inhibiting the growth of the opponent Bm by delivering the WapA toxin via nanotubes.

Fig. 3.

ymdB mediates Bm inhibition by Bs. a Representative time-lapse microscopy images displaying a mixture of Bs (OS23: ΔymdB, sacA::Pveg -mCherry) and Bm (OS2) (upper panels), and a mixture of Bs (AR16: amyE::PrrnE -gfp) and Bm (OS2) (lower panels). Shown are overlay fluorescence from mCherry or GFP (green) and phase contrast (red) images, captured at the indicated time points. Bm cells are shown in black while Bs cells are shown in green. Scale bar represents 10 µm. b Bs (GB61: ∆ymdB) and Bm (OS2) were grown separately or in a mixture in LB medium at 37 °C. Cells were plated for CFUs at the indicated time points. Bs and Bm were differentiated by colony morphology. Each point represents an average value and s.d. of three independent experiments. c RNA was isolated from Bs (PY79) and Bs (GB61: ∆ymdB) cells grown to the mid logarithmic phase and expression of wapA was determined by qRT-PCR. Transcript levels are relative to Bs (PY79). Each bar represents an average value and s.d. of three independent experiments. d Bs (SH29): wapA-2×HA, ∆ymdB, amyE::Phyper-spank -ymdB, ∆hag) cells harboring wapA-2xHA were spotted onto EM grids. Cells were subjected to immuno-gold HR-SEM using primary antibodies against HA and secondary gold-conjugated antibodies. Samples were not coated before observation. Shown are two examples of WapA-2xHA localization (white dots) to nanotubes: intimate intercellular nanotube (a) and a nanotube network view b. HR-SEM images were acquired using TLD-SE (Through lens detector-secondary electron) (1) and vCD (low-kV high-contrast detector) (2). An enlargement of the boxed regions in (2) is shown in (3). Scale bars represent 200 nm

Methionine extraction from Bm by Bs

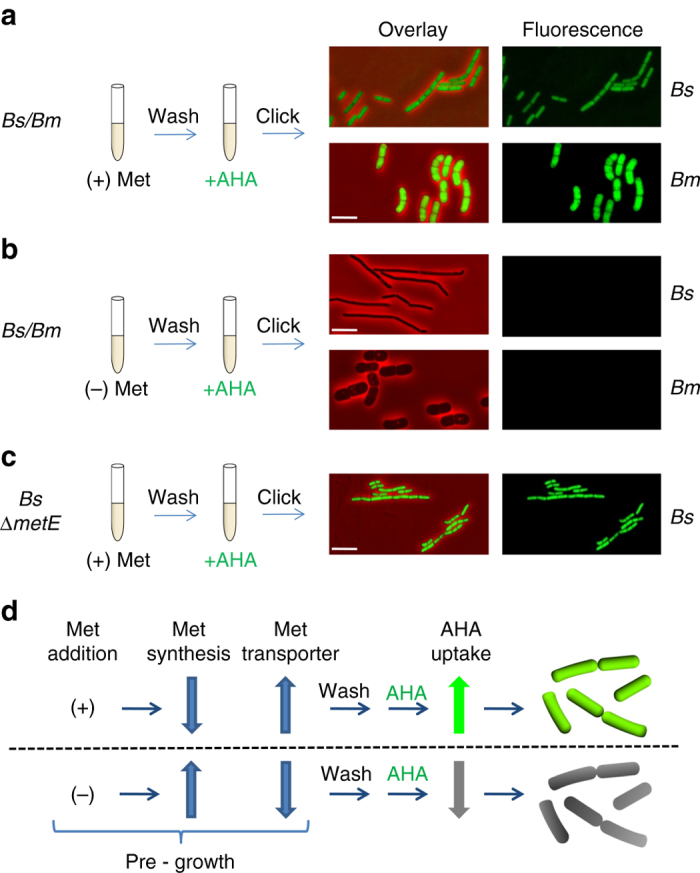

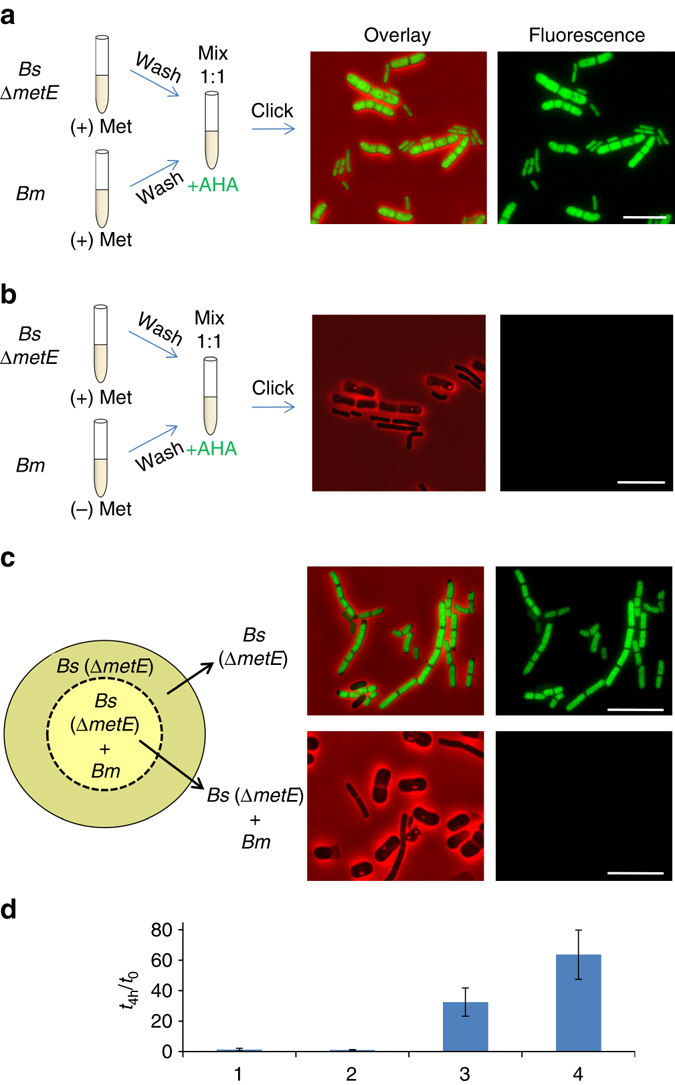

So far we revealed that Bs is capable of delivering the WapA toxin into Bm, killing a potential competitor within the niche, and that this antagonistic activity also requires the phosphodiesterase YmdB. We next examined whether Bs can also act inversely, extracting nutrients from Bm for its own benefit. Evidence for mutual cross feeding between different auxotrophic strains has been previously reported (e.g., ref. 12). To observe such potential molecular delivery, we devised a strategy utilizing the methionine (Met) analogue, L-azidohomoalanine (AHA), as a nutrient reporter. AHA is incorporated into newly synthesized proteins, and can be readily monitored using fluorescence microscopy, by tagging the AHA azide group with a fluorophore using copper catalyzed click reaction19. Bs or Bm cells were pre-grown in the presence of Met in order to repress the expression of Met biosynthesis and boost the expression of Met transporters20. Cells were then washed and incubated for 1.5–2 h with AHA as a substitute for Met. The subsequent click reaction revealed that cells of both Bacilli were heavily labeled by AHA, as indicated by the strong fluorescence signal emitted from the cells (Fig. 4a). However, when the cells of both strains were pre-grown in the absence of Met, and then similarly washed and incubated with AHA, no fluorescence signal was detected (Fig. 4b). These results indicate that when Met is scarce, both strains keep producing endogenous Met for their own growth, which is preferable over AHA21, and therefore remain unstained (Fig. 4d). Consistently, utilizing a Met auxotrophic Bs strain (∆metE) resulted in an increase in AHA uptake, as indicated by a stronger fluorescence signal compared to the prototroph wild type strain (Fig. 4c; Supplementary Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Pre-incubation with Met affects AHA uptake. a, b Bs (PY79) or Bm (OS2) were grown over night in S7 medium in the presence (a) or the absence (b) of Met (50 μg/ml). Cells were then washed in PBS×1 and resuspended in S7 supplemented with AHA (1 mM). Cells were incubated for additional 2 h, underwent click reaction and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Shown are overlay images of fluorescence from AHA (green) and phase contrast (red; left panels), and AHA fluorescence alone (right panels). c Met auxotroph Bs (LS5: ΔmetE) was grown over night with Met and processed as described in a. d A schematic model of exogenous Met effect on Bacilli Met transporters and endogenous Met synthesis. Pre growth in the presence of external Met results in AHA uptake, whereas pre-growth in the absence of external Met restricts AHA uptake. Fluorescence images were normalized to the same intensity range for each strain. Scale bars represent 3 µm

To detect molecular exchange between the two Bacilli, Bm pre-grown with or without Met was mixed with Bs (∆metE), and the mixture was supplemented with AHA instead of Met and incubated for 1.5–2 h. As expected, when Bs (∆metE) was mixed with Bm, pre-grown with Met, the two Bacilli were labeled with AHA (Fig. 5a). In contrast, when Bs (∆metE) was mixed with Bm, pre-grown in the absence of Met, both Bacilli cells remained unlabeled (Fig. 5b), indicating the lack of AHA uptake. Since Bs (∆metE) must obtain external Met/AHA for its survival, the lack of AHA labeling suggests that Bs (∆metE) was able to acquire Met from Bm. Conceivably; the expression of the Met transporters in the Bs (∆metE) was decreased during the co-incubation period, resulting in unlabeled cells. Consistent with this idea, Bs (∆metE) could grow and divide in a medium lacking Met, only when co-cultured with Bm (Fig. 5d). We interpret these results to conclude that Bs (∆metE) acquires Met from its neighboring Bm either from the shared medium or in a contact-dependent manner. To test these possibilities, we designed a Transwell experiment in which Bs (∆metE) was grown simultaneously in two separate compartments in medium containing AHA. One compartment contains Bs alone, while the adjacent compartment contains a mixture of Bs and Bm, the latter pre-grown in the absence of Met. In such system, the two cultures share the same AHA containing medium (Fig. 5c). Following growth, cells from each chamber underwent click reaction separately. Our analysis revealed that Bs (∆metE), grown alone, exhibited an apparent fluorescence signal from AHA, indicating that it could not acquire Met from Bm via the shared medium. On the other hand, neither of the strains in the mixture, located in the adjacent compartment, displayed any detectible fluorescence signal (Fig. 5c). These results show that Bs is capable of extracting Met from Bm, and that a direct contact must exist to facilitate this molecular extraction.

Fig. 5.

Bs extracts Met from its neighboring Bm. a, b Bm (OS2) was pre-grown in the presence (a) or the absence (b) of Met (50 μg/ml), washed in PBSx1, mixed with Bs (LS5: ΔmetE) and resuspended in S7 supplemented with AHA (1 mM). Cells were incubated for additional 1.5 h, underwent click reaction and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Shown are overlay images of fluorescence from AHA (green) and phase contrast (red; left panels), and AHA fluorescence alone (right panels). Fluorescence images were normalized to the same intensity range. c Bm (OS2), pre grown in the absence of Met, and Bs (LS5: ΔmetE) were mixed and incubated in the inner Transwell compartment. For a comparison, Bs (LS5: ΔmetE) was incubated in the outer Transwell compartment. Both the mixture in the inner well, and the Bs grown alone in the outer well, shared the same S7 medium containing AHA (1 mM). After 2 h of incubation, the cells underwent click reaction and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Shown are overlay images of fluorescence from AHA (green) and phase contrast (red; left panels), and AHA fluorescence alone (right panels). Fluorescence images were normalized to the same intensity range. d Shown are CFU ratios at t 4-h/t 0 of the following cultures: (1) Bs (LS5: ΔmetE) grown in the absence of Met. (2) Bs (OS21: ΔmetE, ΔymdB) co-cultured with Bm (OS2) in the absence of Met. (3) Bs (LS5: ΔmetE) co-cultured with Bm (OS2) in the absence of Met. (4) Bs (LS5: ΔmetE) grown in the presence of Met. Bm OS2 cells were pre-grown in the absence of Met. Shown are average values and s.d. of three independent experiments. Scale bars represent 10 µm

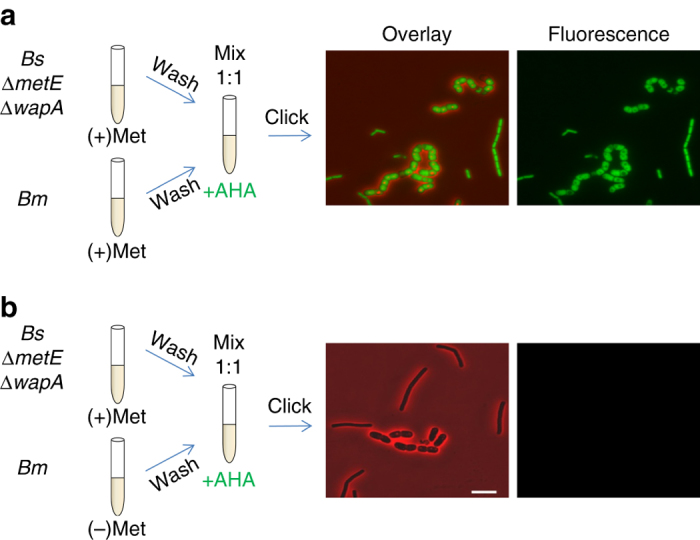

We next sought to explore whether the killing of Bm is a prerequisite for nutrient extraction by Bs. We therefore, co-cultured Bm, pre-grown in the presence or the absence of Met, with Bs (∆metE) lacking the wapA gene. The absence of WapA did not affect the ability of Bs to acquire Met from Bm, as the results were similar to those of the Bs (∆metE) parental strain harboring intact WapA (Fig. 6). Thus, although Met extraction and toxin delivery are both contact-dependent phenomena, they operate autonomously.

Fig. 6.

WapA delivery is not a prerequisite for Met extraction. a, b Bm (OS2) was grown over night in S7 medium in the presence (a) or the absence (b) of Met (50 μg/ml). Cells were then washed in PBSx1, mixed with Bs (OS25: ∆metE, ∆wapA) and resuspended in S7 supplemented with AHA (1 mM). Cells were incubated for additional 1.5 h, underwent click reaction and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Shown are overlay images of fluorescence from AHA (green) and phase contrast (red; left panels), and AHA fluorescence alone (right panels). Scale bar represents 5 µm

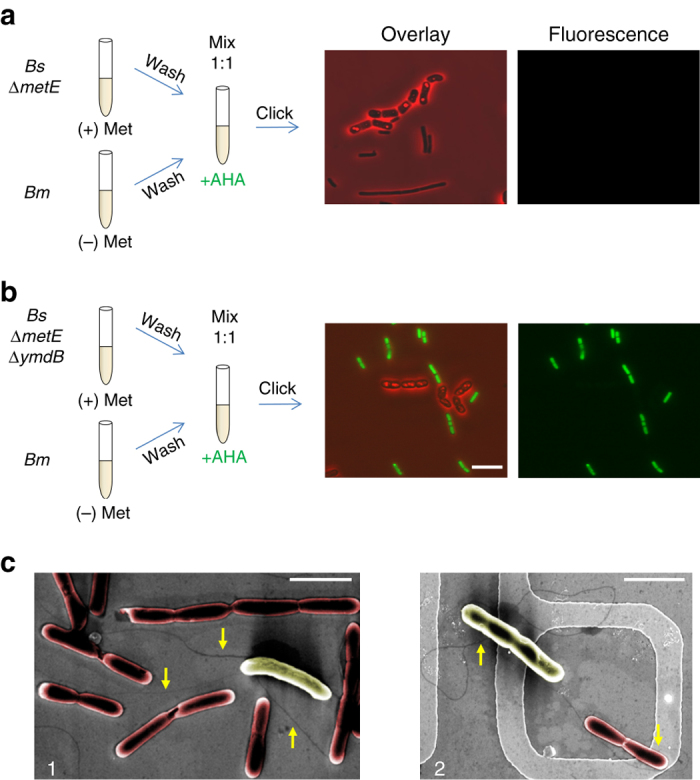

YmdB is required for Met extraction from Bm by Bs

A plausible mechanism that could account for the contact mediated exchange of nutrients between the two Bacilli might involve the YmdB phosphodiesterase, and particularly its role in nanotube formation. We therefore examined whether the ability of Bs to extract nutrients from Bm is also YmdB mediated. To test this possibility, Bs (∆metE) harboring ΔymdB was incubated for 1.5 h with Bm (pre-grown in the absence of Met) in the presence of AHA, and the mixture was subjected to click reaction. The results obtained were explicit, Bs (∆metE) cells lacking ymdB were heavily labeled with AHA (Fig. 7b), while Bs (∆metE) cells harboring intact ymdB remained unlabeled (Fig. 7a), similarly to the results displayed in Fig. 5b. Consistent with these results, Bs (∆metE) cells lacking ymdB were unable to grow and divide in a medium lacking Met, when co-cultured with Bm (Fig. 5d). These findings show that Bs lacking ymdB is deficient in extracting the favorable Met from Bm, and consequently acquires AHA from the medium.

Fig. 7.

ymdB is required for Met extraction. a, b Bm (OS2) was pre grown in the absence of Met (50 μg/ml), washed in PBS×1, mixed with Bs (LS5: ΔmetE) (a) or Bs (OS21: ΔmetE, ΔymdB) (b), and resuspended in S7 supplemented with AHA (1 mM). Cells were incubated for additional 1.5 h, underwent click reaction and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Shown are overlay images of fluorescence from AHA (green) and phase-contrast (red; left panels), and AHA fluorescence alone (right panels). Fluorescence images were normalized to the same intensity range. Scale bar represents 10 µm. c Bs (GB168: ΔymdB, Δhag, amyE::Phyperspank-ymdB) and Bm (OS2) cells were incubated at low density in LB medium for 1 h, and then fixed and visualized by HR-SEM without coating. Shown are HR-SEM images (×15,000) of (1) a single Bm cell (yellow) linked via nanotubes to several Bs cells (red), and (2) a single nanotube linking neighboring Bs and Bm. Arrows point to nanotube structures. Scale bars represent 3 µm

The observation that toxin delivery and nutrient extraction are dependent on YmdB, the findings that both activities are contact-dependent, and the localization of WapA to nanotubes, suggest that interspecies nanotubes are involved in these processes. To examine the existence of nanotube connections between the two investigated strains, we utilized a method enabling the visualization of nanotubes in living cells at low cell density using a fluorescent membrane dye10. Nanotubes could be observed in such conditions upon intense fluorescent exposures. By exploiting this approach, we could detect long nanotubes emerging from Bs, connecting neighboring cells (Supplementary Fig. 6A). Elongated nanotubes were also observed to link two Bm cells (Supplementary Fig. 6A), indicating that Bm is also capable of forming tubes. Furthermore, when the two Bacilli were mixed, nanotubes bridging Bs and Bm cells were visible (Supplementary Fig. 6A). To better detect these interspecies connections, the mixture was visualized using non-coated HR-SEM10. We have previously shown that nanotubes observed by fluorescence microscopy correlated with nanotube structures observed by non-coated HR-SEM10. Indeed, a network of long distance and short intimate nanotubes was evidently observed to connect the two Bacilli (Fig. 7c; Supplementary Fig. 6B, C). These results reinforce the view that nanotubes could serve as the route for molecular exchange between the two species. We suggest that the lack of YmdB perturbs nanotube formation, which in turn impairs Bs ability to deliver WapA to Bm and extract its Met.

Discussion

Here we show that Bs employs two complementing approaches in an attempt to antagonize its Bm opponent, both by delivering the WapA toxin to halt its growth and by simultaneously preying on its vital nutrient components. We demonstrate that both activities are mediated by YmdB, but operate independently. Since YmdB is required for nanotube formation10, WapA was found to be localized to nanotube structures, and nanotubes were found to bridge Bs and Bm, we propose that nanotubes facilitate this bidirectional molecular trafficking, and that Bs could both deliver and acquire molecules via the same path.

Nutrient exchange leading to cross feeding among bacterial cells has been known for many years, and was utilized as a basic tool for deciphering bacterial metabolic pathways (e.g, refs. 22–24). However, only in recent studies the requirement of cell to cell contact for such exchange was substantiated, as in some cases it was found to be associated with nanotube like structures bridging distant bacterial species12, 13. Interestingly, long extracellular extensions involved in nutrient delivery from afar were exemplified to be employed by the Gram-negative Delftia sp. In response to a unique carbon source, this bacterium produces membrane vesicle chains, termed nanopods, extending to long distances25, suggesting that nanopods are utilized for long distant acquisition of specific nutrients. The ability to directly extract vital molecules from the surrounding bacteria holds an enormous beneficial potential, as the bacterium not only eliminates its rival, but also has the key to extract valuable nutrients from its opponent reservoir in a direct and efficient way. Thus, after inhibiting the growth of its niche rival, the bacterium can further benefit from exploiting its opponent’s vital resources. Bacteria harboring tools to employ this strategy could gain access to otherwise restricted nutrient pools, and therefore could dominate a niche, especially under limited nutritional conditions. Such mechanism could be valuable for species competing for the same territory in multicellular biofilm-like structures26, 27.

Our results show that the delivery of the WapA toxin is responsible for the observed Bm growth inhibition by Bs. WapA was shown to be constantly exchanged among nearby Bs cells, reducing viability in cells lacking the cognate wapI immunity gene16, 28; however, its exact delivery mechanism was not elucidated. WapA was shown to carry a secretion signal sequence in its N-terminal, and to contain the toxic RNase activity in its C-terminal part16, 29–31. Our data show that nanotubes provide a route for WapA molecular delivery. Yet, it is unclear whether WapA molecules localize over the tube surface and/or inside the tube lumen, as the immuno-SEM analysis utilized in this study may perturb nanotube integrity, and the antibody signal could be obtained from the nanotube lumen or surface. It is possible that WapA is interacting with the nanotube membrane, and that this interaction enables WapA translocation. The substantial abundance and variety of toxin-anti toxin modules, with some bacteria carrying multiple systems in their genome32, 33, brings about the intriguing possibility that nanotubes provide a path for the transport of diverse toxins.

The possibility of bidirectional molecular flow within nanotubes could be explained by a dual function of the same tube or by the existence of two types of operating tubes, each acting in a unidirectional fashion. We have previously shown that proteins and plasmids, which are relatively large molecules, are delivered among Bs cells via nanotubes in a donor to recipient directionality10. Here we provide evidence that small molecules, such as Met, can be acquired via nanotubes, raising the possibility that directionality could be determined by the size of the transported cargo. However, other properties such as electrical charge, shape and hydrophobicity could also affect molecular delivery. So far, the known external apparatuses produced by bacteria such as Type III, IV and VI secretion systems, were shown to operate in a unidirectional fashion from donor to recipient, most commonly by delivering toxic molecules into the targeted cells34. Although evidence for molecular extraction of valuable nutrients are accumulating35, an apparatus that facilitates this extraction has not been assigned. We propose that nanotubes, which operate in a contact-dependent manner, can serve as such an apparatus.

Nutrient exchange among different bacterial species was so far monitored by bacterial growth. Here, we devised a method to visualize and quantify nutrient exchange using the AHA surrogate. This method could be similarly utilized to report molecular exchange among any given bacterial species. Furthermore, this strategy can be extended to determine flow directionality of additional labeled molecules, such as nucleotides and various carbon sources. With the growing conceptual view that comprehending interspecies interactions among bacteria is key for better understanding natural bacterial communities, visualizing molecular trade could provide a direct approach to follow molecular paths in complex communities.

Methods

Strains and general methods

Bs strains are derivatives of the wild type strain PY7914, while Bm is a wild-type soil isolate (OS2). To isolate Bm 1 gm of soil was diluted in LB to 10−5, incubated 30 min at 80 °C, plated on LB plates, and incubated over night at 30 °C. Colonies were than isolated and sequenced (Hylabs) using 16S rDNA global primers. Bacterial strains and plasmids are listed in Supplementary Table 2, and primers are listed in Supplementary Table 3. All general methods were carried out as described previously36. All the experiments were carried out at 37 °C. Transformation into Bm OS2 cells was carried out as previously described37. In brief, Bm OS2 cells were grown up to 1.0 OD600 (10 ml). Cells were then washed with electroporation buffer (25% PEG 6000 and 0.1 M sorbitol) and resuspended in 1 ml of electroporation buffer. Electroporation was carried out with 0.1 ml of cells supplemented with 2 μg of plasmid at 1500 V (Bio-Rad). Cells were then diluted into 1 ml of LB and plated on selective antibiotic plate. wapI expression was induced by the addition of 5 mg/ml xylose.

Liquid competition assay

Bs and Bm cells were grown separately over night at 23 °C. Cells were then diluted to OD600 0.05 in 8 ml LB, mixed together, and incubated at 37 °C with shaking (200 rpm). CFUs, and OD600 were measured as indicated. Strains were differentiated by colony morphology.

Solid agarose competition assay

Overnight cultures of Bs and Bm were diluted to OD600 0.1, mixed together and mounted onto a metal ring (A-7816, Invitrogen) filled with LB agarose (1.5%). Cells were incubated in a temperature controlled chamber at 37 °C, and followed by light microscopy, utilizing Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope. Images were captured using Photometrics CoolSnap HQ2, and were edited using NIS Elements AR version 4.5.

Transwell plate assay

Bs and Bm cells were grown separately over night at 23 °C. Cells were then diluted to OD600 0.05 and 3 ml of each strain were placed within a Transwell plate (3450 clear, Costar), consisting of 6 wells, each contains two chambers, separated by a 0.4 µm membrane. The Transwell plate was incubated at 37 °C with shaking (30 rpm), and CFUs and OD600 were measured as indicated.

Visualizing AHA uptake

Bs and Bm cells were grown over night at 30 °C in S7 minimal medium38, containing all amino acids or lacking Met. Cells were then diluted to OD600 0.05 and incubated in S7 medium at 37 °C to OD600 0.3. Next, cells were washed in PBSx1 to remove residual Met, diluted to OD600 0.05, and incubated in S7 medium lacking Met, either in monoculture or co-culture, and supplemented with AHA (1 mM). Cells were grown until reaching OD600 0.15 (~ 1.5–2 h), and click reaction was carried out. In brief, cells were centrifuged and washed in PBS×1 to remove residual AHA, resuspended in 50% ethanol for 3 min, followed by a wash in 100% ethanol. Cells were then centrifuged and re-suspended in 230 µl PBSx1 and 12.5 µl of freshly made sodium ascorbate (100 mM; Sigma). Then, mixed separately with 2.5 µl of 50 mM tris(3-hydroxypropyltriazolylmethyl)amine (THPTA, Sigma), 1.25 µl of 20 mM CuSO4 (Sigma), and 3 µl of 2 mM alkyne dye (Alexa Fluor 488 Alkyne, Invitrogen), and left to react for 3 min in the dark at RT. The mixture was added to the cells, and samples were left in the dark at RT for 30 min. Finally, Cells were centrifuged, washed in PBSx1, and observed by fluorescence microscopy.

Nanotube detection

Exponentially growing cells were spotted at low density onto an ITO-coated cover slip9, 10 and covered with a dialysis membrane. The cover slip was then assembled into a mounting frame (A-7816, Invitrogen) filled with liquid LB supplemented with 1 µg/ml FM 4-64 fluorescent membrane dye (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen). Cells were incubated in a temperature controlled chamber at 37 °C for 1 h. Cells were visualized by Eclipse Ti (Nikon, Japan), equipped with CoolSnap HQII camera (Photometrics, Roper Scientific, USA). System control and image processing were performed with NIS Elements AR 4.3 (Nikon, Japan) and MetaMorph 7.7.5 software (Molecular Devices, USA).

HR-SEM microscopy for nanotube visualization

Bs and Bm cells were spotted at low density onto an ITO cover slip, covered with a dialysis membrane, and incubated in LB medium for 1 h. Cells were then left overnight for fixation in 2% glutaraldehyde in sodium cacodylate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.2) at 4 °C. The dialysis membrane was then removed, and the cover slip was gently pulled out from the ring. To dehydrate the cells, the cover slip underwent a series of washes in increasing concentrations of ethanol (25, 50, 75, and 96%) for 10 min each time, then again in the same concentrations of Freon diluted in ethanol. Samples were observed using Through-Lens Detector operated at Secondary Electron (TLD-SE) mode by Magellan XHR SEM (FEI).

Immuno-HR-SEM

Bs cells were grown on EM grids (mesh copper grids, EMS) and were gently removed and grid-attached cells were washed three times with PBS×1, fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and 0.01% glutaraldehyde in sodium cacodylate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.2) for 10 min at 25 °C. Subsequently, grids were washed 3 times in PBS×1 and were incubated in PBS×1 containing 2% BSA and 0.1% Tween 20 for 30 min at 25 °C and washed twice with PBS×1. Next, grids were incubated for 2 h at 25 °C with rabbit anti-HA antibodies (Thermo Scientific, USA), diluted 1:1000 in PBSx1 containing 1% BSA. Grids were then washed three times with PBS×1 and incubated for 1 h at 25 °C with gold-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibodies (Jackson, USA), diluted 1:500 in PBS×1. Grids were washed three times with PBS×1 and fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in sodium cacodylate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.2) for 1 h at 25 °C. Grids were then washed gently with water, and cells were dehydrated by exposure to a graded series of ethanol washes (25, 50, 75, 95, and 100% (×2); 10 min each), followed by overnight incubation in vacuum. Specimens were imaged without coating by Magellan XHR SEM (FEI) using Through-Lens Detector operated at Secondary Electron (TLD-SE) and Low-voltage high-Contrast backscatter electron Detector (vCD).

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR

RNA was extracted from Bs cells grown to the mid logarithmic phase by FastRNA Pro Blue kit (MP Biomedicals) according to the manufacturer protocol. RNA concentration was determined using NanoDrop 2000C (Thermo Scientific). RNA (2 μg) from each sample was treated with RQ1 DNase (2 Units, Promega), and subjected to cDNA synthesis using qScript cDNA synthesis kit (Quanta Biosciences), according to the manufacturer protocol. qRT-PCR reactions were conducted using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad), and fluorescence detection was performed using Bio-Rad CFX Connect Real time system according to manufacturer instructions. RNA from rpsE and 16S rRNA was used to normalize expression. To verify that a single product was amplified a melt curve analysis was done using the Bio-Rad CFX manager software (v. 3.1). The relative gene expression levels were calculated from threshold cycle (C T) values using the 2−ΔΔCT method39. Each assay was performed in duplicates with at least two RNA templates prepared from independent biological repeats. qRT-PCR primers were designed using Primer3 software (v. 0.4.0, available online).

Data availability

The authors declare that the relevant data supporting the findings of the study are available in this article and its Supplementary Information files, or from the corresponding author upon request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank I. Popov and E. Blayvas (NanoCentre, Hebrew U) for help with the EM analysis and A. Rouvinsky, I. Rosenshine and G. Bachrach (Hebrew University, IL), and members of the Ben-Yehuda laboratory for valuable comments. We are grateful to R. Biedendieck (Technische Universität Braunschweig, DE) for providing Bm plasmids. This work was supported by the European Research Council Advance Grant (339984) awarded to S.B.-Y.

Author contributions

O.S., A.K.B. and S.B. performed the experiments. O.S., A.K.B., S.B. and S.B.-Y. conceived the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. S.B.-Y. managed the project. G.B.M.M., E.T., L.S. and G.M. contributed tools, strains and reagents.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Ofer Stempler, Amit K. Baidya and Saurabh Bhattacharya contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00344-7.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Konovalova A, Sogaard-Andersen L. Close encounters: contact-dependent interactions in bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 2011;81:297–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ng WL, Bassler BL. Bacterial quorum-sensing network architectures. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2009;43:197–222. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rivera J, et al. Bacillus anthracis produces membrane-derived vesicles containing biologically active toxins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:19002–19007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008843107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pukatzki S, Ma AT, Revel AT, Sturtevant D, Mekalanos JJ. Type VI secretion system translocates a phage tail spike-like protein into target cells where it cross-links actin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:15508–15513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706532104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aoki SK, et al. A widespread family of polymorphic contact-dependent toxin delivery systems in bacteria. Nature. 2010;468:439–442. doi: 10.1038/nature09490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aoki SK, et al. Contact-dependent inhibition of growth in Escherichia coli. Science. 2005;309:1245–1248. doi: 10.1126/science.1115109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nudleman E, Wall D, Kaiser D. Cell-to-cell transfer of bacterial outer membrane lipoproteins. Science. 2005;309:125–127. doi: 10.1126/science.1112440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kudryashev M, et al. Evidence of direct cell-cell fusion in Borrelia by cryogenic electron tomography. Cell Microbiol. 2011;13:731–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubey GP, Ben-Yehuda S. Intercellular nanotubes mediate bacterial communication. Cell. 2011;144:590–600. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubey GP, et al. Architecture and characteristics of bacterial nanotubes. Dev. Cell. 2016;36:453–461. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pirbadian S, et al. Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 nanowires are outer membrane and periplasmic extensions of the extracellular electron transport components. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:12883–12888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410551111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pande S, et al. Metabolic cross-feeding via intercellular nanotubes among bacteria. Nature Communications. 2015;6:6238. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benomar S, et al. Nutritional stress induces exchange of cell material and energetic coupling between bacterial species. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:62833. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Youngman P, Perkins JB, Losick R. Construction of a cloning site near one end of Tn917 into which foreign DNA may be inserted without affecting transposition in Bacillus subtilis or expression of the transposon-borne erm gene. Plasmid. 1984;12:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0147-619X(84)90061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mamou G, Malli Mohan GB, Rouvinski A, Rosenberg A, Ben-Yehuda S. Early developmental program shapes colony morphology in bacteria. Cell Rep. 2016;14:1850–1857. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koskiniemi S, et al. Rhs proteins from diverse bacteria mediate intercellular competition. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:7032–7037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300627110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diethmaier C, et al. The YmdB phosphodiesterase is a global regulator of late adaptive responses in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 2014;196:265–275. doi: 10.1128/JB.00826-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diethmaier C, et al. A novel factor controlling bistability in Bacillus subtilis: the YmdB protein affects flagellin expression and biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 2011;193:5997–6007. doi: 10.1128/JB.05360-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dieterich DC, et al. Labeling, detection and identification of newly synthesized proteomes with bioorthogonal non-canonical amino-acid tagging. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:532–540. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hullo MF, Auger S, Dassa E, Danchin A, Martin-Verstraete I. The metNPQ operon of Bacillus subtilis encodes an ABC permease transporting methionine sulfoxide, D- and L-methionine. Res. Microbiol. 2004;155:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sinai L, Rosenberg A, Smith Y, Segev E, Ben-Yehuda S. The molecular timeline of a reviving bacterial spore. Mol. Cell. 2015;57:695–707. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walter W, Bacher A. Biosynthesis of thiamin in Bacillus subtilis. Isolation of mutants accumulating 4-amino-5-hydroxymethyl-2-methylpyrimidine phosphate. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1977;103:359–366. doi: 10.1099/00221287-103-2-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith-Keary PF. Partial reversions of a proline auxotroph of Salmonella typhimurium. Cross-feeding associated with cell-to-cell contact. Mutat. Res. 1972;15:259–272. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(72)90073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rolfe B, Eisenberg MA. Genetic and biochemical analysis of the biotin loci of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 1968;96:515–524. doi: 10.1128/jb.96.2.515-524.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shetty A, Chen S, Tocheva EI, Jensen GJ, Hickey WJ. Nanopods: a new bacterial structure and mechanism for deployment of outer membrane vesicles. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e20725. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pathak DT, et al. Cell contact-dependent outer membrane exchange in myxobacteria: genetic determinants and mechanism. PLoS. Genet. 2012;8:e1002626. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitri S, Foster KR. The genotypic view of social interactions in microbial communities. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2013;47:247–273. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-111212-133307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lyons NA, Kraigher B, Stefanic P, Mandic-Mulec I, Kolter R. A combinatorial kin discrimination system in Bacillus subtilis. Curr. Biol. 2016;26:733–742. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foster SJ. Molecular analysis of three major wall-associated proteins of Bacillus subtilis 168: evidence for processing of the product of a gene encoding a 258 kDa precursor two-domain ligand-binding protein. Mol. Microbiol. 1993;8:299–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tjalsma H, et al. Proteomics of protein secretion by Bacillus subtilis: separating the “secrets” of the secretome. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2004;68:207–233. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.2.207-233.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Antelmann H, Yamamoto H, Sekiguchi J, Hecker M. Stabilization of cell wall proteins in Bacillus subtilis: a proteomic approach. Proteomics. 2002;2:591–602. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200205)2:5<591::AID-PROT591>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sala A, Bordes P, Genevaux P. Multiple toxin-antitoxin systems in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Toxins. 2014;6:1002–1020. doi: 10.3390/toxins6031002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pandey DP, Gerdes K. Toxin-antitoxin loci are highly abundant in free-living but lost from host-associated prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:966–976. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abdallah AM, et al. Type VII secretion-mycobacteria show the way. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007;5:883–891. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ponomarova O, Patil KR. Metabolic interactions in microbial communities: untangling the Gordian knot. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2015;27:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2015.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harwood, C. R. & Cutting, S. M. Molecular Biological Methods for Bacillus (Wiley, 1990).

- 37.Moro A, Sanchez JC, Serguera C. Transformation of Bacillus megaterium by electroporation. Biotechnol. Tech. 1995;9:589–590. doi: 10.1007/BF00152449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vasantha N, Freese E. Enzyme changes during Bacillus subtilis sporulation caused by deprivation of guanine nucleotides. J. Bacteriol. 1980;144:1119–1125. doi: 10.1128/jb.144.3.1119-1125.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the relevant data supporting the findings of the study are available in this article and its Supplementary Information files, or from the corresponding author upon request.