Abstract

Disheveled-associated activator of morphogenesis (DAAM) is a diaphanous-related formin protein essential for the regulation of actin cytoskeleton dynamics in diverse biological processes. The conserved formin homology 1 and 2 (FH1–FH2) domains of DAAM catalyze actin nucleation and processively mediate filament elongation. These activities are indirectly regulated by the N- and C-terminal regions flanking the FH1–FH2 domains. Recently, the C-terminal diaphanous-autoregulatory domain (DAD) and the C terminus (CT) of formins have also been shown to regulate actin assembly by directly interacting with actin. Here, to better understand the biological activities of DAAM, we studied the role of DAD-CT regions of Drosophila DAAM in its interaction with actin with in vitro biochemical and in vivo genetic approaches. We found that the DAD-CT region binds actin in vitro and that its main actin-binding element is the CT region, which does not influence actin dynamics on its own. However, we also found that it can tune the nucleating activity and the filament end–interaction properties of DAAM in an FH2 domain-dependent manner. We also demonstrate that DAD-CT makes the FH2 domain more efficient in antagonizing with capping protein. Consistently, in vivo data suggested that the CT region contributes to DAAM-mediated filopodia formation and dynamics in primary neurons. In conclusion, our results demonstrate that the CT region of DAAM plays an important role in actin assembly regulation in a biological context.

Keywords: actin, Drosophila, fluorescence, formin, neuron

Introduction

Formins are actin assembly machineries playing essential roles in diverse biological processes. The core actin-interacting region is the conserved formin homology (FH)2 2 domain that catalyzes actin nucleation and mediates processive elongation of filament ends. The activities of the FH2 domain are assisted by the upstream formin homology 1 (FH1) domain that interacts with profilin–actin (1–5). The N- and C-terminal regions flanking the FH1–FH2 domains have diverse composition and functions among different formin families. Formins belonging to the Diaphanous-related formin (DRF) family, including Diaphanous (Dia), Disheveled-associated activator of morphogenesis (DAAM), formin-like protein (FMNL), FH1/FH2 domain-containing protein, and inverted formin2 (INF2) are characterized by the presence of an N-terminal Diaphanous inhibitory domain (DID) and a C-terminal Diaphanous autoregulatory domain (DAD). It is well established that the intramolecular contacts formed between these regions keep the FH2 in an inactive state by preventing its interaction with actin. The functions of the FH2 domain in actin assembly are activated upon Rho GTPase-dependent relief of the DID/DAD autoinhibitory interaction (5–11).

Recent studies showed that, besides autoregulation, the C-terminal regions of formins from yeast to mammals (such as mouse Dia1, FMNL3, INF2, Drosophila Capuccino, yeast Bni1 and Bnr1, and human Daam1) can also influence the active FH2 domain-mediated actin assembly (12–15). A common feature of the C-terminal regions studied so far is that they increase the efficiency of the FH2-catalyzed nucleation. Additionally, isolated C-terminal regions can directly interact with actin, independently of the FH2 domain. The C terminus of INF2 contains a Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome homology (WH2)-like DAD motif, which in its isolated form sequesters monomeric actin and severs actin filaments (12), whereas the WH2-DAD C-terminal region of FMNL3 nucleates actin and slows elongation in a dimeric form (14). Similarly, the isolated dimeric DAD from mDia1 seems to be sufficient to promote actin nucleation (13). In contrast, the tail region of Capuccino does not influence nucleation or elongation in the absence of FH2 (15). The biochemical evidence suggests that the activities of the C-terminal regions vary among formins and raise the question how and which of the activities of the isolated C-terminal regions are transmitted to the functionality of each formin in the context of the FH1–FH2 domains. In addition, the in vivo significance of the direct interaction of the C-terminal regions of formins with actin and its role in actin cytoskeleton dynamics regulation are not well understood.

In this work, we investigated the Drosophila DAAM formin belonging to the DRF family. DAAM is involved in diverse morphogenetic processes mediated by the actin cytoskeleton. For example, DAAM plays a role in organizing apical actin cables that define the tracheal cuticle pattern (16). It is also required for axonal growth and guidance by promoting filopodia formation in the growth cone (17), and DAAM is essential for sarcomerogenesis (18–20). In our previous work, we described the physicochemical properties of the interaction of Drosophila DAAM FH1–FH2 and actin, and we showed that DAAM FH1–FH2 is a profilin-gated actin assembly factor (18, 21). To better understand the biological functioning of DAAM, we aimed to analyze the biochemical activities of recombinantly produced DAD-CT regions of DAAM in its isolated form, as well as in the context of the FH1–FH2 domains in the regulation of actin assembly. By dissecting the activities of the DAD and CT regions of DAAM, we aimed to reveal which of the reported activities of the C-terminal regions of formins are shared by the DAD-CT regions of Drosophila DAAM to influence FH1–FH2-assisted actin assembly. We also investigated how the DAD-CT region influences filopodia formation and FH2-mediated actin dynamics in primary neurons using in vivo genetic approaches.

Results

cDAAM is more efficient in catalyzing actin nucleation than the FH1–FH2 domains

To investigate the effects of the C-terminal regions of Drosophila DAAM on actin assembly, first we produced two recombinant proteins that either lack or possess the C-terminal DAD-CT regions, the FH1–FH2 and cDAAM proteins, respectively (Fig. 1A). To analyze the actin assembly efficiencies of these constructs, the polymerization kinetics of G-actin and profilin/G-actin were measured in pyrenyl polymerization experiments (Fig. 2, A and B). We found that both constructs can accelerate actin polymerization (Fig. 2A). However, cDAAM accelerates the overall polymerization rate of both free G-actin and profilin/G-actin ∼36-fold more efficiently than the FH1–FH2 (which lacks the C-terminal DAD-CT regions) at all concentrations that were tested (Fig. 2B). This observation is consistent with the findings on the human Daam1 protein, suggesting that this feature is conserved between species (13).

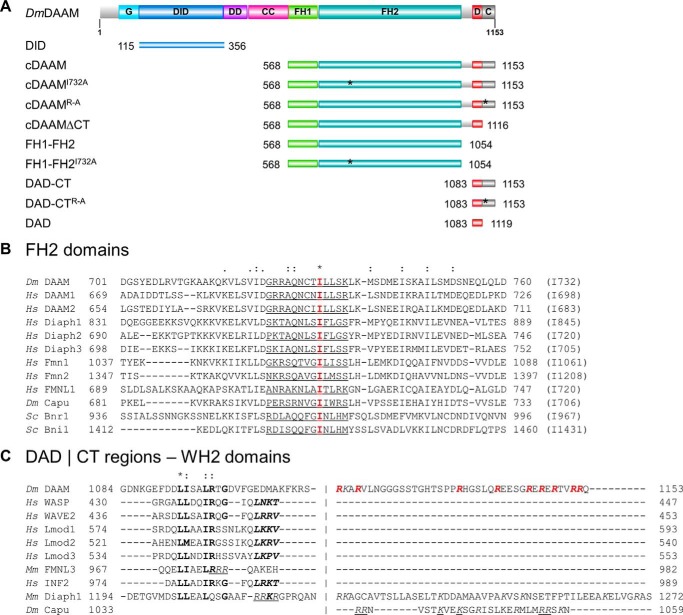

Figure 1.

Domain organization and sequence alignments of DAAM. A, domain organization of full-length Drosophila melanogaster DAAM formin (Dm DAAM) and of the constructs investigated in this study. G, GTPase-binding domain; DID, diaphanous inhibitory domain; DD, dimerization domain; CC, coiled coil; FH, formin homology domain; D, diaphanous autoregulatory domain; CT, C-terminal sequence element. Numbers indicate the number of the first and the last residue in each construct. The positions of the mutated amino acids are highlighted by asterisks. The figure was made with Illustrator for Biological Sciences (57). B, sequence alignment of FH2 domains from different formins. The conserved Ile in the FH2 domain is highlighted in red, and its position in each formin is given in parentheses at the end of the sequences. The αD helix of the knob region is underlined. C, alignment of C-terminal regions from different formins and WH2 domain sequences. The hydrophobic amino acid triplet and the LKK(T/V) motif are shown by bold and bold italics, respectively. Positively charged Arg and Lys residues in the CT region are shown in italics. The Arg residues replaced by Ala in the DAAM DAD-CTArg–Ala construct are highlighted in red. Residues that are shown to be important for actin interaction in mDia1, FMNL3, and Capuccino are underlined (13, 14, 47). UniProt accession numbers are as follows: Dm DAAM, Q8IRY0; Hs DAAM1, Q9Y4D1; Hs DAAM2, Q86T65; Hs Diaph1, O60610; Hs Diaph2, O60879; Hs Diaph3, Q9NSV4; Hs Fmn1, Q68DA7; Hs Fmn2, Q9NZ56; Hs FMNL1, O95466; Dm Capu, Q24120; Sc Bnr1, P40450; Sc Bni1, P41832; Hs WASP, P42768; Hs WAVE2, Q9Y6W5; Hs Lmod1, P29536; Hs Lmod2, Q6P5Q4; Hs Lmod3, Q0VAK6; Mm FMNL3, Q6ZPF4; Hs INF2, Q27J81. Dm, D. melanogaster; Hs, Homo sapiens; Sc, Saccharomyces cerevisiae; Mm, Mus musculus.

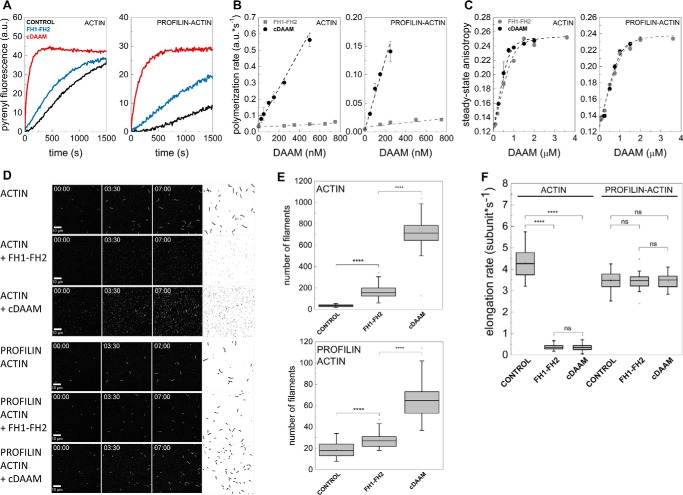

Figure 2.

cDAAM is more efficient in catalyzing actin assembly than FH1–FH2. A, representative pyrenyl traces of spontaneous and FH1–FH2 or cDAAM catalyzed assembly of free G-actin and profilin/G-actin, as indicated. Final concentrations are as follows: [actin] = 2 μm; [profilin] = 6 μm; [FH1–FH2] = 200 nm; [cDAAM] = 200 nm. B, FH1–FH2 and cDAAM concentration dependence of the relative polymerization rate of free G-actin and profilin/G-actin, as indicated. Error bars, standard deviations, n = 3–5. C, steady-state anisotropy of Alexa488NHS–G-actin in the absence and presence of profilin as the function of DAAM concentration, as indicated. Dashed lines in the corresponding colors show the fits to the data according to Equation 3. Dissociation equilibrium constants are summarized in Table 1. Error bars, standard deviations, n = 2–3. Final concentrations are as follows: [actin] = 0.2 μm; [LatA] = 4 μm; [profilin] = 0.8 μm; [NaCl] = 5 mm. D, TIRFM montages of actin assembly and representative skeletonized images showing the field of view of actin assembly in the absence and presence of FH1–FH2 or cDAAM, as indicated. Scale bar, 10 μm, time = min/s. Final concentrations are as follows: [actin] = 0.5 μm; [profilin] = 2 μm; [FH1–FH2] = 100 nm; [cDAAM] = 100 nm. E, number of actin filaments nucleated spontaneously or in the presence of FH1–FH2 and cDAAM derived from skeletonized images. Final concentrations as in D, n = 20–62. F, elongation rate of individual actin filaments polymerized from free and profilin/G-actin in the absence and presence of FH1–FH2 or cDAAM. Final concentrations as in D, n = 30–89. a.u., arbitrary units; ns, not significant.

Because the FH2 domain of some formins, such as Bni1 and mDia1, has low affinity to monomeric actin in the absence of the C-terminal regions (13, 22, 23), we wanted to examine whether the differences in the actin assembly promoting activities of FH1–FH2 and cDAAM can arise from different actin affinities. Therefore, the interactions of FH1–FH2 and cDAAM with G-actin and profilin/G-actin were investigated in steady-state fluorescence anisotropy experiments. To avoid artificial increase in anisotropy due to the presence of polymerizing agents, latrunculin A was used to keep actin in monomeric form (24, 25). We observed a similar concentration-dependent increase in the values of the steady-state anisotropy in the presence of both DAAM constructs (Fig. 2C). This reflects that FH1–FH2, as well as cDAAM, binds monomeric actin, and the complexes are characterized by similar affinities in the few tens of nanomolar range (Table 1). This result suggests that the lower polymerization activity of FH1–FH2 compared with cDAAM does not originate from their different affinities to monomeric actin.

Table 1.

Dissociation equilibrium constants (KD) of the DAAM/actin interactions

FL means fluorescently labeled protein; ND means not determined.

| Construct |

KD ± S.D.a (μm) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| G-actin | Profilin/G-actinFL | ProfilinFL/G-actin | |

| FH1-FH2 | 0.061 ± 0.02 | 0.056 ± 0.02 | ND |

| cDAAM | 0.052 ± 0.02 | 0.068 ± 0.02 | ND |

| DAD-CT | 3.87 ± 0.19 | 3.54 ± 0.22 | 4.71 ± 0.53 |

| 9.71 ± 0.51 (17 mm NaCl) | ND | ND | |

| 44.43 ± 2.85 (50 mm NaCl) | ND | ND | |

| DAD | >100 | >100 | ND |

| DAD-CTArg-Ala | >500 | >500 | ND |

| FH1-FH2I732A | 6.78 ± 0.96 | 4.41 ± 0.76 | ND |

| cDAAMI732A | 0.064 ± 0.02 | 0.093 ± 0.04 | ND |

a The values were derived in the presence of 5 mm NaCl, unless indicated otherwise.

The different polymerization efficiencies of FH1–FH2 and cDAAM can also arise from differences in their nucleation and/or elongation activities. Because bulk pyrenyl polymerization assays cannot distinguish these two activities, the assembly of individual actin filaments was investigated by total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRFM) (Fig. 2, D–F). In control experiments, we found that the number of actin filaments significantly decreased in the presence of profilin, compared with that of measured for free G-actin (p < 0.0001, Fig. 2, D and E), consistent with the nucleation-suppressing activity of profilin (26, 27). In the presence of FH1–FH2 and cDAAM, a dramatic increase in the number of filaments formed was observed as compared with the number of spontaneously formed filaments, which reflects the nucleation-promoting activity of these constructs (Fig. 2, D and E). Importantly, quantitative analysis of these data revealed that cDAAM nucleated significantly more filaments than FH1–FH2, suggesting that cDAAM is more efficient at promoting the initial nucleation phase of actin filament formation than FH1–FH2 (Fig. 2, D and E). This result demonstrates that the DAD-CT region makes the FH2 domain more efficient in catalyzing actin nucleation. Spontaneously growing actin filaments elongated at a rate of 4.30 ± 0.6 and 3.48 ± 0.4 subunits·s−1 in the absence and presence of profilin, respectively (Fig. 2F). These values are in agreement with the well-established barbed-end association rate constants of ATP-Mg2+–G-actin (free G-actin, k+ = 10.23 ± 1.5 μm−1·s−1; profilin/G-actin, k+ = 8.29 ± 0.9 μm−1·s−1, see Equation 4 (21, 28, 29)). The analysis showed that both FH1–FH2 and cDAAM almost completely inhibit the elongation of free G-actin (vFH1–FH2 = 0.36 ± 0.2 subunits·s−1 (p < 0.0001) and vcDAAM = 0.37 ± 0.1 subunits·s−1 (p < 0.0001), Fig. 2F). In contrast, in the presence of profilin the elongation rate is similar to that of the spontaneously growing actin filaments (vFH1–FH2 = 3.44 ± 0.3 subunits·s−1 (p = 0.45) and vcDAAM = 3.49 ± 0.4 subunit·s−1 (p = 0.44), Fig. 2F). Thus, profilin by relieving the elongation inhibitory activity of the constructs contributes to effective filament growth. These observations, regarding the profilin-gated effect of FH1–FH2 on filament elongation are entirely consistent with our previously published data (21). The profilin-dependent regulation of filament elongation was also reported for the human Daam1 protein (30); however, the net effect was different. Daam1 did not affect filament growth significantly in the absence of profilin, although it accelerated elongation from profilin–actin ∼4-fold as compared with the spontaneous rate (30). These differences may arise from different conditions, including the species-specific differences in activities, the expression system, the tag, the profilin isoform used, and/or the labeling of hDaam1.

In conclusion, the effects of the FH1–FH2 and cDAAM constructs on filament elongation from either free or profilin/G-actin are quantitatively the same; however, their nucleation efficiencies differ markedly. These observations clearly show that the more potent actin assembly activity of cDAAM as compared with FH1–FH2 arises from a difference in their nucleating efficiency, suggesting that the C-terminal regions contribute to the nucleating activity of the FH2 domain.

Main G-actin-binding site in DAD-CT is the CT region

To analyze the activities of the C-terminal regions of DAAM in more detail, recombinant fragments were produced containing both the DAD domain and the C-terminal end of the protein (DAD-CT) or only the isolated DAD domain (Fig. 1A). First, the interaction of DAD-CT and DAD with monomeric actin was investigated by measuring the steady-state anisotropy of fluorescently labeled actin. We found that DAD-CT can bind to G-actin, independently of the FH2 domain (Fig. 3A). However, the increase in salt concentration (i.e. increase in the amount of NaCl) resulted in a gradual decrease in actin affinity, suggesting an ionic strength-dependent interaction (Fig. 3A and Table 1), which is similar to the salt-dependent interaction reported for the tail domain of Capuccino (15). DAD-CT interacts with profilin/G-actin equally well as with free G-actin indicating that profilin does not affect the binding (Fig. 3A and Table 1). In contrast to DAD-CT, the interaction of the DAD domain lacking the CT region with monomeric actin is extremely weak even at low ionic strength conditions (KD >100 μm at 5 mm NaCl) (Fig. 3A and Table 1). To further analyze which regions are important in the interaction between DAD-CT and monomeric actin, we investigated a construct in which the basic arginine residues found in the CT region were replaced by alanines (DAD-CTArg–Ala) (Fig. 1, A and C). Our data did not show a detectable interaction between DAD-CTArg–Ala and monomeric actin (KD >500 μm at 5 mm NaCl) (Fig. 3A and Table 1).

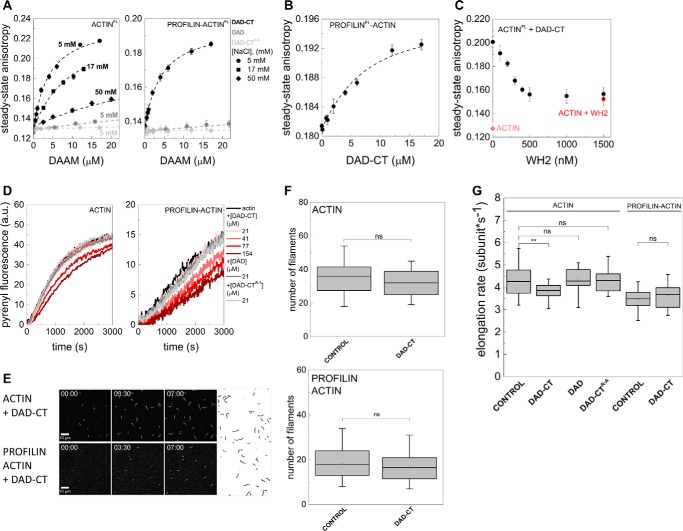

Figure 3.

Interactions of DAD-CT and DAD with actin. A, steady-state anisotropy of Alexa488NHS-labeled G-actin in the absence and presence of profilin as the function of DAD-CT, DAD, and DAD-CTArg–Ala concentrations, as indicated. Dashed lines in the corresponding colors show the fits to the data according to Equation 3. Dissociation equilibrium constants are summarized in Table 1. Error bars, standard deviations, n = 2–4. Final concentrations are as follows: [actin] = 0.2 μm; [LatA] = 4 μm; [profilin] = 0.8 μm; [NaCl] = 5 mm (circles); 17 mm (squares); 50 mm (diamonds). FL, fluorescently labeled protein. B, steady-state anisotropy of Alexa568NHS-labeled profilin in the presence of G-actin as the function of DAD-CT concentration, as indicated. Dashed line in the corresponding color shows the fit to the data according to Equation 3. Dissociation equilibrium constant is given in Table 1. Error bars, standard deviations, n = 2–3. Final concentrations are as follows: [actin] = 4 μm; [LatA] = 8 μm; [profilin] = 2 μm; [NaCl] = 5 mm. FL, fluorescently labeled protein. C, steady-state anisotropy of Alexa488NHS-labeled G-actin in complex with DAD-CT as a function of SALS-WH2 concentration. As controls, the steady-state anisotropies of G-actin in the absence of any binding proteins and G-actin saturated with SALS-WH2 (1.5 μm) are shown. Final concentrations are as follows: [actin] = 0.2 μm; [LatA] = 4 μm; [DAD-CT] = 20 μm; [NaCl] = 5 mm. FL, fluorescently labeled protein. D, representative polymerization kinetics of free G-actin and profilin/G-actin in the absence and presence of the C-terminal regions of DAAM, as indicated. Final concentrations are as follows: [actin] = 2 μm; [profilin] = 6 μm. E, TIRFM montages of actin assembly and representative skeletonized images showing the field of view of actin assembly in the absence and presence of DAD-CT, as indicated (for spontaneous actin assembly see Fig. 2D). Scale bar = 10 μm, time = min/s. Final concentrations are as follows: [actin] = 0.5 μm; [profilin] = 2 μm; [DAAM] = 42 μm. F, number of actin filaments nucleated spontaneously or in the presence of DAD-CT derived from skeletonized images. Final concentrations as in E, n = 16–20. G, elongation rate of individual actin filaments polymerized from free and profilin/G-actin in the absence and presence of DAD-CT (42 μm), DAD (42 μm), or DAD-CTArg–Ala (42 μm). Final concentrations as in E, n = 24–79. ns, not significant.

To further elaborate on the binding mode of DAD-CT, the influence of different actin-binding proteins was tested on its interaction with G-actin. Profilin is known to interact with the hydrophobic cleft of monomeric actin (31). The steady-state anisotropy of fluorescently labeled profilin in complex with G-actin was measured in the presence of DAD-CT. We found that DAD-CT causes a concentration-dependent increase in the steady-state anisotropy of profilin bound to G-actin (Fig. 3B and Table 1). In case of competitive binding, one would expect the dissociation of fluorescent profilin from G-actin, which would result in a decrease in anisotropy. The opposite tendency that we observed suggests that a ternary complex is formed between monomeric actin, profilin, and DAD-CT, indicating that the core binding site of DAD-CT is different from that of profilin. Next, we tested how the interaction of DAD-CT is influenced by WH2 domain proteins, which N-terminally interact with the barbed face, while their C terminus binds along the ridge between the inner and outer domains of actin up to the pointed end (32–34). We used the WH2 domains of sarcomere length short protein (SALS-WH2), which have relatively long C-terminal extensions linked to the N-terminal α-helix (28). The steady-state anisotropy of the DAD-CT–G-actin complex was decreased upon addition of SALS-WH2 in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 3C). At a high SALS-WH2 concentration, the value of the anisotropy decreased to the value characteristic to the SALS-WH2–G-actin complex, suggesting that SALS-WH2 interferes with the G-actin binding of DAD-CT. This indicates that the main binding site of DAD-CT overlaps with that of WH2.

Altogether, these observations indicate that the isolated C terminus of DAAM can interact with monomeric actin and that the core C-terminal actin-binding elements are located mainly in the CT region that is able to establish electrostatic interactions with actin.

DAD-CT does not influence actin dynamics in the absence of the FH2 domain

To test the functional consequences of monomer binding, the effects of isolated DAD-CT on actin dynamics were investigated. In fluorescence spectroscopy experiments we found that DAD-CT does not affect significantly the assembly of free G-actin and profilin/G-actin at lower concentrations (Fig. 3D). However, higher amounts of DAD-CT (> ∼40–50 μm) resulted in a concentration-dependent decrease in the pyrenyl fluorescence, similarly to what was observed for Capuccino tail (15). In agreement with the spectroscopic data, TIRFM experiments showed that DAD-CT cannot affect significantly actin nucleation (Fig. 3, E and F), and it does not affect the rate of elongation at lower concentrations either (data not shown). DAD-CT moderately slows elongation of free G-actin when it is present at higher amounts (> ∼40 μm) (vDAD-CT = 3.79 ± 0.4 subunit·s−1 (p = 0.009), Fig. 3G), but it does not influence elongation from profilin/G-actin (vDAD-CT = 3.64 ± 0.6 subunit·s−1 (p = 0.47), Fig. 3G). Also, DAD and DAD-CTArg–Ala do not show any effect in the above experiments, consistent with their negligible interaction with monomeric actin (Fig. 3G).

In conclusion, in contrast to the DAD region of mDia1 (13), the isolated DAAM DAD-CT cannot influence significantly actin assembly in the absence of the FH2 domain, which suggests that the C-terminal region of DAAM possesses an FH2-dependent function in the regulation of actin dynamics.

Functional CT is required for the full nucleation promoting activity of DAAM

To further elaborate on the contribution of the DAD-CT region to the nucleation activity of the FH2 domain, we tested its effect in the presence of the FH2 domain. For this purpose, two C-terminally modified constructs were generated possessing the native FH2 but lacking a functional CT region, either by deleting the CT region (cDAAMΔCT) or by introducing the Arg–Ala mutation into the CT region (cDAAMArg–Ala) (Fig. 1A). The effects of the two constructs are indistinguishable from each other both in pyrenyl and TIRFM actin assembly assays, which support that the two modifications are equivalent (Fig. 4). However, neither cDAAMΔCT nor cDAAMArg–Ala can retrieve the maximum nucleation-promoting activity of cDAAM. Both C-terminally modified constructs are ∼6-fold more efficient in accelerating the overall rate of actin polymerization than FH1–FH2, but they are ∼6-fold less effective than cDAAM possessing the native CT region (Fig. 4, A and B). Because they influence elongation in a similar manner as the wild-type constructs, the polymerization-promoting effect of cDAAMΔCT and cDAAMArg–Ala originates from their actin nucleation activity, which is intermediate as compared with FH1–FH2 and cDAAM, as revealed by TIRFM measurements (Figs. 2F and 4, C–E).

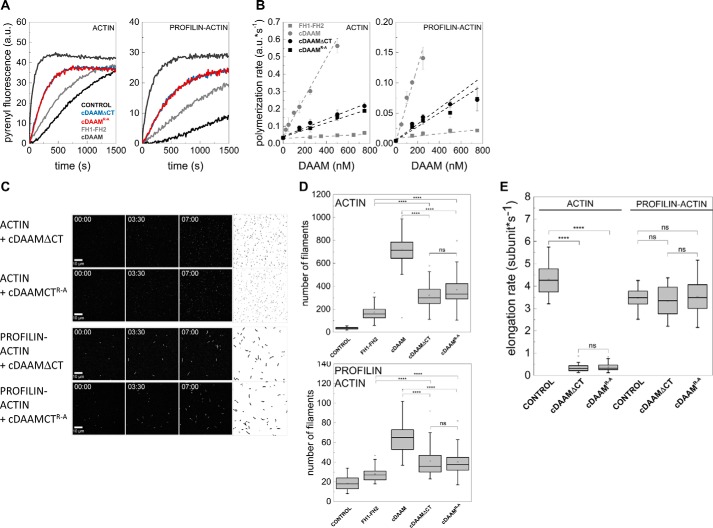

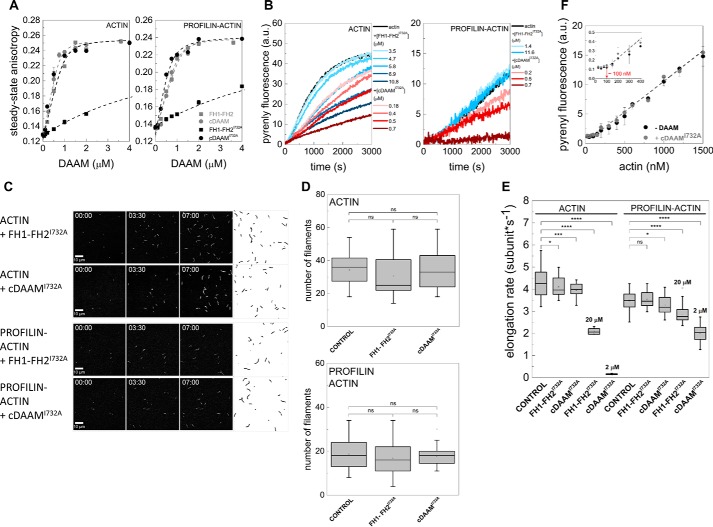

Figure 4.

Effects of DAAM DAD and CT regions in the presence of the native FH2 domain. A, representative pyrenyl traces of spontaneous and cDAAMArg–Ala- or cDAAMΔCT-catalyzed assembly of free G-actin and profilin/G-actin, as indicated. The data for FH1–FH2 and cDAAM from Fig. 2E are shown here as controls. Final concentrations are as follows: [actin] = 2 μm; [profilin] = 6 μm; [cDAAMArg–Ala] = 200 nm; [cDAAMΔCT] = 200 nm. B, cDAAMArg–Ala or cDAAMΔCT concentration dependence of the relative polymerization rate of free G-actin and profilin/G-actin, as indicated. Error bars, standard deviations, n = 3–4. Data obtained for FH1–FH2 and cDAAM from Fig. 2B are shown. C, TIRFM montages of actin assembly and representative skeletonized images showing the field of view of actin assembly in the absence and presence of cDAAMArg–Ala or cDAAMΔCT, as indicated (for spontaneous actin assembly see Fig. 2D). Scale bar, 10 μm, time = min/s. Final concentrations are as follows: [actin] = 0.5 μm; [profilin] = 2 μm; [cDAAMArg–Ala] = 100 nm; [cDAAMΔCT] = 100 nm. D, number of actin filaments nucleated spontaneously or in the presence of cDAAMArg–Ala or cDAAMΔCT derived from skeletonized images. Final concentrations as in C, n = 20–54. E, elongation rate of individual actin filaments polymerized from free and profilin/G-actin in the absence and presence of cDAAMArg–Ala or cDAAMΔCT. Final concentrations as in C, n = 39–79. a.u., arbitrary units; ns, not significant.

These observations suggest that DAD contributes to the nucleation-promoting activity of cDAAM, but the presence of a functional CT region is absolutely necessary to reconstitute its full nucleation ability. Our data also indicate that the contribution of DAD and CT regions to actin nucleation is non-cooperative.

DAD-CT cannot compensate for loss-of function mutation-induced defects in the main activities of the FH2 domain

To better understand the role of DAD-CT in DAAM-mediated actin dynamics, the activities of this region were investigated in the presence of a mutant FH2 domain. The αD helix of the knob region of the FH2 domain contains a highly conserved Ile residue, which is essential for FH2-mediated polymerization (Fig. 1B) (13, 14, 23, 35, 36). By introducing the I732A mutation, we generated a cDAAMI732A construct that contains the DAD-CT region and an FH1–FH2I732A version that is devoid of the C-terminal domains (Fig. 1A). Steady-state anisotropy measurements revealed that the I732A mutation severely reduces the ability of the FH2 domain to bind both free and profilin/G-actin in the absence of DAD-CT (Fig. 5A and Table 1). However, we observed that cDAAMI732A can bind actin with similar affinity as cDAAM, which indicates that the presence of DAD-CT can compensate for the defects in monomer binding induced by the I732A mutation (Fig. 5A and Table 1).

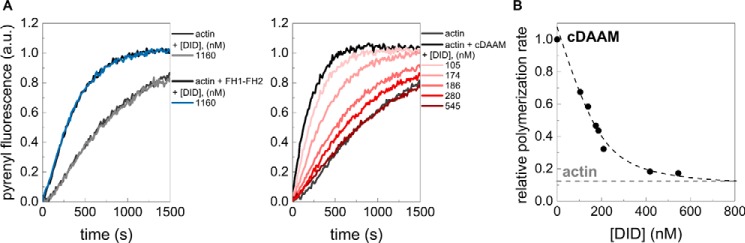

Figure 5.

Effects of DAAM DAD and CT regions on the loss-of-function mutation of FH2. A, steady-state anisotropy of Alexa488NHS-labeled G-actin in the absence and presence of profilin as the function of DAAM concentration, as indicated. The data for FH1–FH2 and cDAAM from Fig. 2C are shown here as controls. Dashed lines in the corresponding colors show the fits to the data according to Equation 3. Dissociation equilibrium constants are summarized in Table 1. Error bars, standard deviations, n = 2–3. Final concentrations are as follows: [actin] = 0.2 μm; [LatA] = 4 μm; [profilin] = 0.8 μm; [NaCl] = 5 mm. B, representative polymerization kinetics of free G-actin and profilin/G-actin in the absence and presence of different regions of DAAM, as indicated. Final concentrations are as follows: [actin] = 2 μm; [profilin] = 6 μm. C, TIRFM montages of actin assembly and representative skeletonized images showing the field of view of actin assembly in the absence and presence of FH1–FH2I732A and cDAAMI732A, as indicated (for spontaneous actin assembly see Fig. 2D). Scale bar, 10 μm, time = min/s. Final concentrations are as follows: [actin] = 0.5 μm; [profilin] = 2 μm; [FH1–FH2I732A] = 100 nm; [cDAAMI732A] = 100 nm. D, number of actin filaments nucleated spontaneously or in the presence of FH1–FH2I732A and cDAAMI732A derived from skeletonized images. Final concentrations as in C, n = 20–50. E, elongation rate of individual actin filaments polymerized from free and profilin/G-actin in the absence and presence of FH1–FH2I732A and cDAAMI732A. Final concentrations as in C. 20 and 2 μm indicate the data obtained in the presence of higher concentrations of FH1–FH2I732A and cDAAMI732A, respectively, n = 15–79. F, critical concentration (J(c)) plots of actin assembly in the absence and presence of cDAAMI732A (1 μm), as indicated. Inset, enlarged view of the initial part of the J(c) plot, red arrow highlights the breaking points corresponding to the unassembled actin at steady-state. Dashed lines in the corresponding colors show the fit to the linear part of the data. Error bars, standard deviations, n = 3. a.u., arbitrary units; ns, not significant.

In pyrenyl polymerization assays, we found that FH1–FH2I732A inhibits the overall polymerization of free G-actin, but the assembly rate of profilin/G-actin is not affected in the concentration range that we could test in these experiments (Fig. 5B). The cDAAMI732A mutant is more efficient in reducing the rate of actin assembly from both free G-actin and profilin/G-actin than FH1–FH2I732A (Fig. 5B). Importantly, the inhibition of the bulk polymerization rate by the constructs carrying the mutation is the opposite as to that observed for the wild-type FH2 domain (Fig. 2, A and B). These observations show that the I732A mutation impairs the proper actin assembly activities of DAAM FH2, which is consistent with previous data (36). To better understand the underlying effects, TIRFM experiments were performed. In contrast to the wild-type fragments (Fig. 2E), filament number was not changed significantly in the presence of either of the two mutant constructs (Fig. 5, C and D). This finding indicates that despite being able to interact with actin, the I732A mutation abolishes the nucleation activity of DAAM. Our data also suggest that the presence of the DAD-CT region is able to counteract the actin-binding defects of the FH2 domain induced by I732A; however, it cannot restore the proper functionality of the mutated FH2 domain in actin nucleation. The analysis of the effects on elongation revealed that FH1–FH2I732A only moderately affects filament growth from free G-actin in the concentration range in which the wild-type construct almost completely inhibits elongation (vFH1–FH2I732A =4.09 ± 0.4 subunit·s−1 (p = 0.03), Fig. 5E). Even higher amounts (20 μm FH1–FH2I732A) resulted only in ∼55% inhibition (Fig. 5E). In agreement with the pyrenyl polymerization experiments, FH1–FH2I732A does not affect significantly filament growth from profilin/G-actin at low concentrations (vFH1–FH2I732A = 3.53 ± 0.4 subunit·s−1 (p = 0.30), Fig. 5E), although it moderately inhibits elongation when it is added at higher amounts (vFH1–FH2I732A = 2.09 ± 0.1 subunit·s−1 (p < 0.0001), Fig. 5E). cDAAMI732A moderately slows filament elongation when it is added at the same amount as cDAAM (vcDAAMI732A = 3.97 ± 0.3 subunit·s−1 (p = 0.00014), Fig. 5E). At relatively high concentrations (2 μm), it largely slows down the elongation from free G-actin, similarly to the wild-type protein (vcDAAMI732A = 0.15 ± 0.02 subunit·s−1 (p < 0.0001), Fig. 5E). However, unlike cDAAM that maintains elongation in the presence of profilin (Fig. 2F), cDAAMI732A functions oppositely, it hinders profilin/G-actin association to barbed ends in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5E).

The reduced filament growth rate observed in the presence of cDAAMI732A can result from the altered barbed-end rate constants of monomers due to capping-like function and/or a decrease in assembly-competent G-actin due to sequestration. To test these possibilities, the influence of cDAAMI732A on the amount of unassembled actin was measured at steady-state (J(c) plot, Fig. 5F). In the case of spontaneous actin assembly, the steady-state amount of unassembled free G-actin (critical concentration) is reflected by the breaking point of the J(c) plot (Fig. 5F). In the absence of DAAM, the breaking point appeared at ∼100 nm, in agreement with the well-established value of the barbed-end critical concentration (Fig. 5F) (1, 2). The J(c) plot recorded in the presence of cDAAMI732A was parallel to the plot obtained for actin, and the breaking point was not affected significantly (Fig. 5F). The complete and permanent blocking of barbed ends by classic barbed-end capping proteins, such as CapG, would result in a shift of the breaking point up to the value characteristic to the critical concentration of pointed ends (∼600 nm) (1–3, 28). The unaffected breaking point indicates that the filament ends are not strongly capped by cDAAMI732A, and monomer-polymer exchanges at barbed ends can occur. We made a similar observation for other DAAM constructs (21). In the case of sequestration, considering the dissociation equilibrium constant of the cDAAMI732A/G-actin interaction (Table 1), the critical concentration of actin assembly (Fig. 5F), and the concentration of cDAAMI732A used in this experiment (1 μm), one would expect an increase of ∼500 nm in the amount of unassembled actin due to sequestration, which would result in a significant shift in the breaking point to ∼600 nm (28). In contrast, in the case of sequestration, the number of actin filaments is expected to be decreased (28); however, in TIRFM experiments we found that cDAAMI732A does not change filament number (Fig. 5D), which further supports the lack of sequestering activity. Therefore, these data support that cDAAMI732A neither sequesters G-actin nor blocks completely and permanently monomer-polymer exchange at barbed ends as a classic capping protein. To explain the large but not complete inhibition of elongation by cDAAMI732A, one can assume that it slows filament elongation at barbed ends by influencing the rate constants of subunit association and/or dissociation.

Consistently with the importance of the conserved Ile residue in actin interaction (37), the mutation impairs not only the nucleation ability of the FH2 domain but also diminishes its interaction with the barbed end of the filaments. The combination of these two effects results in a decreased bulk polymerization rate, detected in the pyrenyl polymerization assays (Fig. 5B). At high concentration, DAAM FH2I732A can maintain some interactions with filament ends similarly to other formins (e.g. mDia1 (13)). Even if such high concentration is physiologically not relevant, this approach allowed us to address the effects of DAD-CT on the interaction of FH2 with barbed ends. Our data indicate that besides the key Ile residue, other residues/binding sites in the FH2 domain also contribute to barbed-end interactions of DAAM, albeit with much lower affinities. Comparative structural analysis of DAAM FH2 with other formins reveals that residues in the knob region near the Ile732, as well as the lasso/post interface, can contribute to actin binding (36). Based on our data, the coordination between these different binding sites is crucial for functional barbed-end interaction. Importantly, our observations that the magnitude of the effect of the FH2I732A mutant on filament elongation is more pronounced in the presence of DAD-CT than in the absence of it suggests that the C-terminal regions are important for filament end interaction.

DAD-CT contributes to the antagonism with capping proteins

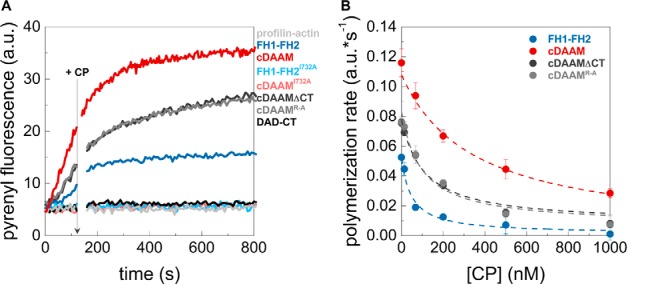

We found that cDAAMI732A affects filament end dynamics more efficiently than the FH1–FH2I732A (Fig. 5, B and E), which suggests that besides nucleation, DAD-CT is also important for filament end interaction. We studied the effect of these domains in the presence of capping protein (CP) to further analyze the potential role of DAD-CT in the formin/barbed-end interaction. CP is well known for its ability to bind to filament barbed ends and block their elongation (Fig. 6) (38, 39). Formins were shown to be able to antagonize the effect of CPs at barbed ends to sustain processive growth of actin filaments (40–44). Thus, we investigated whether DAAM can compete with CP for barbed-end binding and, if it does so, which regions are important for this activity. Actin assembly was initiated in the absence or presence of different DAAM constructs, and the CP in increasing amounts was added to the polymerization mixtures after ∼120 s (Fig. 6A) (40). CP inhibits both the rate and the extent of DAAM-mediated actin assembly for all constructs, however with different efficiencies (Fig. 6). Quantitative analysis revealed that cDAAM is more efficient than FH1–FH2 in protecting filament ends (IC50 = 345.9 ± 27.60 nm and IC50 = 47.7 ± 16.97 nm, respectively). Mutations in the CT region (cDAAMΔCT and cDAAMArg–Ala) partially reduce the ability of DAAM to compete with CP (IC50 = 108.6 ± 19.35 nm for cDAAMΔCT and IC50 = 93.7 ± 19.06 nm for cDAAMArg–Ala Fig. 6). FH1–FH2I732A and cDAAMI732A failed to antagonize the capping effect when added at the same concentration as the wild-type constructs, in agreement with the importance of Ile732 in barbed-end interaction (Fig. 6A) (37). Because FH1–FH2I732A and cDAAMI732A do not show any difference in this assay, we conclude that the DAD-CT region is unable to compete for barbed-end binding in the absence of a functional FH2 domain (Fig. 6A). Consistent with this, we found that the isolated DAD-CT cannot uncap CP-bound barbed ends (Fig. 6A). These observations corroborate the role of the C-terminal regions of DAAM in filament-end interaction. Importantly, our data clearly demonstrate that although the FH2 domain is necessary for uncapping of CP, the DAD-CT regions can contribute to this antagonistic activity by tuning the filament end protection ability of FH2.

Figure 6.

Antagonism between DAAM and CP. A, polymerization of profilin/G-actin initiated in the absence and presence of DAAM constructs, as indicated. The addition of CP after 120 s is indicated by an arrow. Final concentrations are as follows: [actin] = 2 μm; [profilin] = 6 μm; [CP] = 68 nm; [DAAM] = 200 nm. B, polymerization rates before ([CP] = 0 nm) and after addition of CP at different concentrations derived from pyrenyl traces. Dashed lines in the corresponding color show the fit of the data using Equation 2. The fit gave IC50 values of IC50(cDAAM) = 345.9 ± 27.60 nm; IC50(FH1–FH2) = 47.7 ± 16.97 nm; IC50(cDAAMΔCT) = 108.6 ± 19.35 nm; and IC50(cDAAMArg–Ala) = 93.7 ± 19.06 nm for CP inhibition. Error bars, standard deviations, n = 2–4. a.u., arbitrary units.

Role of DAD-CT in FH2-mediated F-actin interaction

Previously, we showed that both Drosophila DAAM FH2 and FH1–FH2 possess actin filament binding and bundling activities (21). This activity is characteristic for the human Daam1 protein, as well (30, 45). Based on this and to further extend our studies on the role of DAD-CT in actin interaction, we investigated whether the DAD-CT region can interact with F-actin in high-speed co-sedimentation experiments (Fig. 7A). The amount of DAD-CT sedimented with F-actin increased in a concentration-dependent manner, which indicates that DAD-CT can bind to the sides of filamentous actin with a dissociation equilibrium constant of KD(DAD-CT) = 38.9 ± 3.2 μm (Fig. 7A). This suggests less efficient interaction than that of the FH2 domain, which is characterized by KD in the low micromolar range (21). Removal of the CT significantly reduces the binding strength of the C terminus (KD(DAD) >100 μm), whereas the binding of the DAD-CTArg–Ala mutant to F-actin is negligible (Fig. 7A). To test the functional consequences of side binding, the bundling activity of DAAM was studied in low-speed centrifugation assays. We found that FH1–FH2, as well as cDAAM bundle actin filaments with approximately the same efficiency, and the I723A mutation does not affect the bundling activity of FH2 (Fig. 7B). Our results revealed that the DAD-CT region can also bundle F-actin, independently of the FH2 domain; however, its efficiency is extremely low (Fig. 7B). Neither DAD nor DAD-CTArg–Ala show significant activity at the concentrations we could test in the experiments (Fig. 7B).

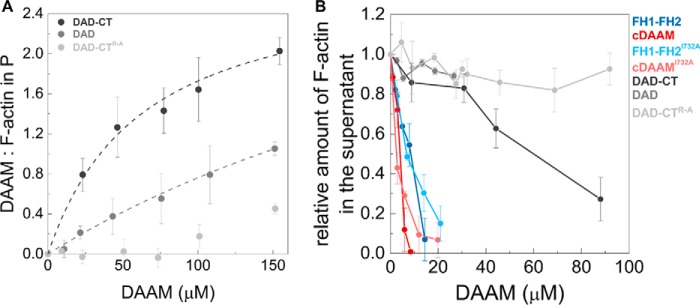

Figure 7.

Interaction of DAD-CT with actin filaments. A, DAAM/F-actin ratio in the pellet (P) derived from the analysis of SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Dashed lines correspond to the fit of the data (21, 35); the fit gave KD values of KD(DAD-CT) = 38.9 ± 3.2 μm, KD(DAD) > 100 μm. [F-actin] = 2.5 μm. Error bars, standard deviations, n = 2–4. B, bundling activity of different regions of DAAM. The relative amount of actin filaments in the supernatant as the function of DAAM concentration, determined from the quantification of SDS-PAGE analysis of the samples. Final concentrations are as follows: [F-actin] = 1 μm. Error bars, standard deviations, n = 2–3.

Altogether, these results show that the isolated DAD-CT can interact with the sides of actin filaments and also suggest that the FH2 domain of DAAM is the core actin filament side-binding/bundling element, whereas the C-terminal region appears to have a minor contribution to this activity. Consistently with the G-actin interaction, these data further support that the main C-terminal actin-binding element is the CT region.

Actin assembly promoting activity of the FH2 domain of DAAM is regulated through an autoinhibitory interaction

The DRF formin subfamily proteins are regulated by intramolecular autoinhibitory interactions mediated by the N-terminal DID and the C-terminal DAD domains. DAAM possesses the N- and C-terminal sequence elements characteristic for these regulatory domains (Fig. 1A). Consistently, our previous investigations showed that Drosophila DAAM constructs lacking either one of the DID or DAD regions behave as constitutively active forms of the protein in in vivo assays (17). To address this issue biochemically, the effects of the recombinant DID fragment on FH1–FH2 (lacking the C-terminal DAD-CT region) and cDAAM (possessing the C-terminal DAD-CT region)-mediated actin assembly were investigated in pyrenyl polymerization experiments (Fig. 8A). We found that DID does not affect the spontaneous actin polymerization or the actin assembly promoting activity of FH1–FH2 (Fig. 8A). In contrast, it inhibits the cDAAM-mediated actin polymerization in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 8). At saturating DID concentrations, the polymerization rate was reduced to the value characteristic of spontaneous actin assembly (Fig. 8). For quantitative analysis, the relative polymerization rates from the slopes of the pyrenyl traces at half-maximum polymerization were derived and plotted as the function of DID concentration (Fig. 8B). The fit gave a dissociation equilibrium constant of ∼30 nm, consistent with a tight interaction between the DID and the DAD-CT domains (see Equation 1).

Figure 8.

FH2/actin interaction is regulated through the DID/DAD-CT interaction. A, representative polymerization kinetics of actin in the absence and presence of DID, FH1–FH2, and cDAAM, as indicated. [actin] = 2 μm (containing 5% pyrenyl actin), [FH1–FH2] = 5 μm, [cDAAM] = 0.51 μm. B, relative polymerization rate of cDAAM catalyzed actin assembly as a function of DID concentration. Dashed line corresponds to the fit of the data using Equation 1. The fit gave half-inhibition of cDAAM by DID at 30.5 ± 14.31 nm. a.u., arbitrary units. The relative rate of spontaneous actin assembly is indicated by gray dashed line.

These results support that the interaction of the FH2 domain of DAAM with actin is regulated by intramolecular interactions between the DID and the C-terminal regions (46). Thus, although the DAD-CT domain might be able to bind actin very weakly (Fig. 3A), similar to other DRFs, its major function is likely related to DID binding through which it shades the actin assembly activity of the FH2 domain.

In vivo activity of the CT region

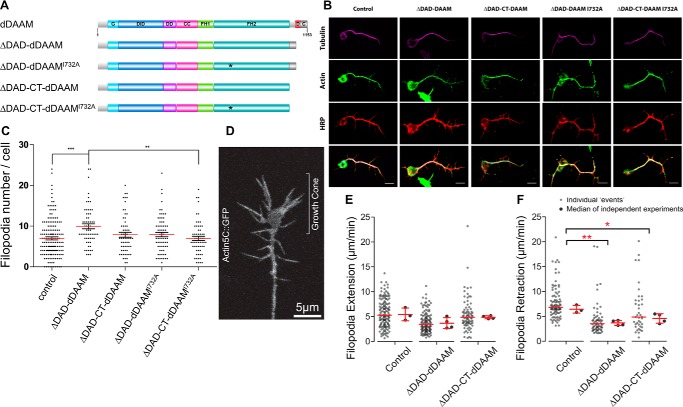

To further assess the functional importance of the actin-interacting domains of DAAM, Drosophila primary neuronal cultures were used to analyze the in vivo effect of FH2 and CT on actin assembly. We took advantage of the fact that growth cone filopodia are primarily actin-based structures, and we previously showed that overexpression of a constitutively active form of dDAAM, lacking the DAD domain (ΔDAD-dDAAM), induces a significant increase in the filopodia number in primary neurons (17). To exploit this effect, CT-truncated and/or FH2I732A-mutated ΔDAD-dDAAM constructs were expressed in Drosophila embryos (Fig. 9A). In accordance with our former results, the pan-neuronal expression of ΔDAD-dDAAM induced a significant increase of axonal filopodia formation as compared with control cells (9.9 ± 0.60 versus 6.9 ± 0.37) (Fig. 9, B and C). In contrast to it, overexpression of ΔDAD-CT-dDAAM induced only a moderate increase in filopodia number (7.8 ± 0.60) (Fig. 9, B and C). Thus, the constitutively active form of dDAAM was more effective in the presence of the CT region. Contribution of the FH2 domain was analyzed by expression of ΔDAD-dDAAMI732A, which was also able to induce a moderate increase in filopodia number (7.9 ± 0.54), comparable with that of ΔDAD-CT-dDAAM (Fig. 9, B and C). These results reveal that, despite the huge differences in their in vitro actin assembly activity, the FH2 and CT domains display some requirements during filopodia formation in cultured neurons. In agreement with a partly redundant role, the filopodia number of cells expressing ΔDAD-CT-dDAAMI732A was comparable with that of control cells (6.9 ± 0.52) (Fig. 9, B and C); thus, the lack of CT combined with the I732A mutation abolished completely the actin assembly activity of dDAAM.

Figure 9.

Constitutively active dDAAM induces filopodia formation in Drosophila primary neurons. A, domain organization of full-length D. melanogaster DAAM formin and of the constructs investigated in the in vivo experiments. Abbreviations are as in Fig. 1A. The position of the I732A mutation is highlighted by asterisk. The figure was made with Illustrator for Biological Sciences (57). B, representative images of primary neurons obtained from control or constitutively active dDAAM-overexpressing embryos, stained with tubulin (magenta), actin (green), and HRP (red). Scale bar, 5 μm. C, expression of ΔDAD-dDAAM (c155>UAS-ΔDAD-dDAAM, n = 62) construct induced a significant increase of filopodia number compared with control (c155/+, n = 162) and ΔDAD-CT-dDAAM I732A (c155>UAS-ΔDAD-dDAAM I732A, n = 60)-expressing cells. The other genotypes were not significantly different (c155>ΔDADCT-dDAAM, n = 61; c155>ΔDADCT-dDAAM I732A, n = 68). Data presented on the figure are given as mean ± S.E. Data were analyzed with Kruskal-Wallis for the whole-data set, followed by Dunn's post hoc test for multiple comparison. D, representative image from a time-lapse sequence of a neuronal growth cone expressing Actin5C::GFP. Scale bar = 5 μm (corresponding to supplemental Movie 1). E, comparison of filopodia extension rate showed no significant difference (one-way analysis of variance, p = 0.09; control, 5.4 ± 1.2, mean ± S.D., n = 3/134; ΔDAD-dDAAM, 3.6 ± 1.2, mean ± S.D., n = 4/118; ΔDAD-CT-dDAAM, 4.8 ± 0.3, mean ± S.D., n = 4/77). F, retraction rate is significantly lower in the case of ΔDAD and ΔDAD-CT overexpression, compared with the control filopodia (one-way analysis of variance, p = 0.0047; control, 6.4 ± 0.7, mean ± S.D., n = 3/91; ΔDAD-dDAAM, 3.6 ± 0.5, mean ± S.D., n = 4/63; ΔDAD-CT-dDAAM, 4.5 ± 0.9, mean ± S.D., n = 4/40).

To better understand the mechanisms of the actin-binding domains of DAAM in filopodia formation, filopodia dynamics was studied in primary neurons expressing ΔDAD-dDAAM or ΔDAD-CT-dDAAM. Filopodia dynamics was followed by co-expression of actin5C::GFP (Fig. 9D), and as expected, live imaging of 7–9 HIV neurons revealed an extensive movement of filopodia (supplemental Movie 1), including lateral displacement, collapse, stasis, and fusion. To characterize filopodia dynamics, we used extension and retraction as readouts (Fig. 9, E and F). We found that the overexpression of the truncated DAAM isoforms do not change significantly the extension rate as compared with control neurons, expressing actin5C::GFP alone (Fig. 9E). However, overexpression of the activated DAAM isoform (ΔDAD-dDAAM) leads to decreased filopodia retraction (Fig. 9F). This finding indicates that activated DAAM is probably involved in filopodia stabilization rather than filopodia elongation, although it still remains possible that DAAM is also involved in the initial actin nucleation steps of filopodia formation. The retraction rate upon ΔDAD-CT–dDAAM overexpression is in between the wild-type control and that of ΔDAD-dDAAM (Fig. 9F), suggesting that the CT domain may have a minor role in filopodia stabilization.

Thus, the analysis of filopodia number and dynamics in primary neurons revealed that the CT domain of DAAM appears to contribute to filopodia formation in vivo, and it may also affect the dynamic behavior of filopodia.

Discussion

In this work we extended the characterization of the C-terminal elements of formins by analyzing the role of the DAD and CT regions of Drosophila DAAM in the regulation of actin dynamics both in vitro and in vivo. We showed that the DAD-CT tunes the nucleation activity and the proper filament end interactions of the FH1–FH2 domains of DAAM, as well as its ability to antagonize with CP.

Our data revealed that the DAD-CT region of DAAM can interact with actin in vitro; however, the binding of isolated DAD is very weak, and hence it is the CT region that is largely responsible for actin interaction (Fig. 3A and Table 1). The C-terminal regions of mDia1, INF2, and FMNL3 possess sequence elements characteristic of the N terminus of the actin-binding WH2 domains (12–14). Comparative sequence analysis of the DAD-CT regions of DAAM indicates some sequence similarity to WH2 domains, as well (Fig. 1C). The DAD region contains the conserved hydrophobic amino acid triplet of LLXXI, which mediates interactions between the N terminus of WH2 domains and the hydrophobic cleft of actin (34). However, the characteristic LKK(T/V) motif, which is essential for the actin binding of WH2 domains, is completely absent from the C terminus of DAAM (Fig. 1C). Similar sequence characters can be observed for the DAD of mDia1 and FMNL3, which also bind actin relatively weakly (Fig. 1C and Table 2) (13, 14). Conversely, INF2 possesses the LKK(T/V) motif that appears to strengthen its affinity to actin (Table 2) (12). The CT of DAAM is a relatively long (∼40 aa) extension and predicted to be intrinsically disordered. Our mutational analysis indicates that the Arg/Lys residues in the CT region are central to efficient actin binding (Fig. 3A). Basic amino acids in the C terminus of mDia1, FMNL3, and Capuccino were shown to contribute to their actin affinity (13, 14, 47). These data suggest that the weak actin binding of the DAD region of formins might be attributed to the hydrophobic WH2-like amino acid triplet; however, other sequence elements that are present in the CT region appear to ensure a significantly stronger interaction.

Table 2.

Properties of the C-terminal elements of different formins

Mm is M. musculus and Dm is D. melanogaster.

| Formin | Main actin interacting modulea | G-actin binding affinity | Nucleation activity in isolated form/contribution to FH2-mediated nucleation | Affecting G-actin interaction | Other effects in actin dynamics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mm INF2 (12>) | WH2-like/DAD sequence | KD ∼0.06 μm | No/yes | Profilin interferes | Monomer sequestration, filament severing |

| 50 mm KCl | |||||

| Mm FMNL3 (14) | WH2-DAD-CT | KD ∼2–3 μm | Yes/yes | INF2 C terminus interferes | Inhibits elongation (∼ nm) |

| 50 mm KCl | mDia1 C terminus does not interfere | ||||

| Mm Dia1 (13) | DAD-CT | KD ∼100 μm | Yes/yes | Profilin does not interfere | Accelerates elongation (∼ μm) |

| 200 mm NaCl | |||||

| Dm Capu (15) | tail | KD ∼20 μm | No/yes | WH2, RPEL1 interfere | Inhibits elongation (>10 μm) |

| 50 mm NaCl | Profilin does not significantly interfere | ||||

| Dm DAAM (this study) | DAD-CT | KD = 44.4 ± 2.85 μm | No/yes | Profilin does not interfere | Inhibits elongation (>40–50 μm) |

| 50 mm NaCl | WH2 interferes |

a The main actin interacting elements of the C-terminal regions are highlighted in boldface.

The DAD-CT region of DAAM has similar affinity for free G-actin and profilin-bound G-actin (Fig. 3A and Table 1). We do not detect any indication for mutually exclusive binding between profilin and DAD-CT to monomeric actin, whereas DAD-CT is displaced by WH2 domains possessing a relatively long and disordered C-terminal extension (Fig. 3, B and C). Profilin interacts with the hydrophobic cleft of subdomains 1 and 3 of actin, which might interfere with the WH2-like binding mode of DAD. The long C-terminal half of WH2 extends along the negative surface patch of the actin molecule toward the pointed face, through interactions mainly controlled by electrostatic forces (32–34). The similar structural features and the competitive binding of DAAM CT and WH2 domains indicate that DAAM CT adapts a binding mode, which is similar to that of the C terminus of WH2. These considerations further support our conclusion that the main actin-binding element of DAD-CT is not the DAD but is the CT region (Fig. 10).

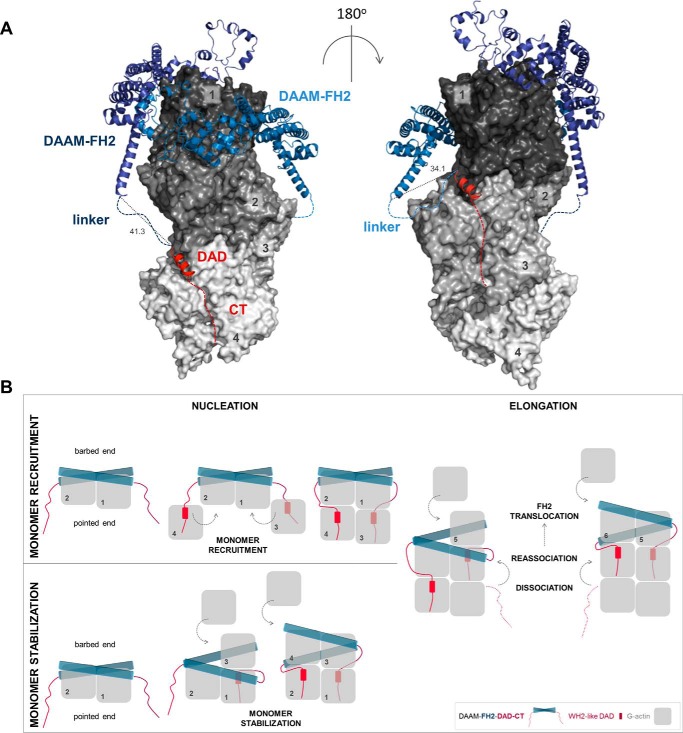

Figure 10.

Structural model of the interactions of FH2, DAD, and CT with actin. A, model was generated using X-ray structures of complexes of FH2–actin and WH2–actin. Four actin subunits (gray, indicated by numbers) are shown according to their arrangement in the Oda's model (58). The FH2 dimer of DAAM (blue) and the DAD region of mDia1 (red) are represented as ribbons. Red dashed lines indicate the possible orientation of the disordered CTs of DAAM. Blue dashed lines indicate the ∼20-aa linkers connecting the FH2 and DAD of DAAM. Distances are given in Å. The model was generated with PyMOL based on the alignment of following structures: Protein Data Bank codes: 4EAH ((48) FMNLFH2-TMR-actin); 2Z6E ((59) hDAAM-FH2); 2BAP ((60) mDia1-DAD); and 2A41 ((61) WIP-WH2). B, alternative model describing actin nucleation mediated by FH2-DAD-CT for low-affinity C-terminal formin regions. In this scenario, the binding of DAD-CT to actin requires increased affinity, which may be manifested through monomer capturing by FH2.

As opposed to mDia1 DAD, the isolated DAD-CT of DAAM cannot nucleate actin filaments on its own, even in its dimeric form maintained by GST (13). However, it markedly contributes to the nucleation efficiency of the FH2 domain, yet a properly functioning FH2 domain is absolutely essential for nucleation (Figs. 2, 4, and 5). The actin binding strengths of the FH1–FH2 and cDAAM constructs are apparently the same (Fig. 2C and Table 1). From this aspect the FH2 domain of DAAM differs from other formins, which requires the C-terminal regions for efficient G-actin binding (13, 22, 23). However, the more potent nucleation activity of cDAAM as compared with that of FH1–FH2 indicates that the presence of the DAD-CT region must change the structural and/or kinetic features of FH1–FH2 when in complex with actin. This is supported by our data, which indicate positive cooperativity between the association of FH2 and DAD-CT to actin, as well as structural considerations as discussed below.

Besides their role in stabilizing nucleation intermediaries, our results also indicate that the C-terminal regions can contribute to proper filament end interaction and to the processivity of DAAM. This is supported by the fact that cDAAM is more efficient in maintaining filament elongation in the presence of capping protein than FH1–FH2 and that the DAD-CT region influences the effect of the I732A mutation on actin elongation (Figs. 5 and 6). Recent findings on the co-regulation of barbed-end dynamics by CPs and formins (e.g. mDia1, FMNL2, and human Daam1) propose the existence of a ternary or decision complex at the filament end (40, 43). Because of the overlapping binding sites of CPs and formins, the co-existence of these proteins at the filament end results in steric clashes, which can be resolved by the partial dissociation of both CPs and formin from the barbed end, as suggested by structural modeling (43). According to the proposed structural features, the main filament end interacting region of the formin in the ternary complex is the αD helix in the knob region. Disrupting this region, by introducing the mutation in the conserved Ile residue, is expected to loosen the formin/barbed-end interaction and weaken its integrity in the ternary complex. This may result in a faster dissociation and/or slower association or complete removal of the formin, leaving the ends capped by CPs, consistently within our experiments (Fig. 6). Importantly, our results shed light on the importance of DAD-CT in the anti-capping activity of DAAM. The more efficient anti-capping activity of cDAAM as compared with FH1–FH2 (Fig. 6) indicates that the C-terminal regions of DAAM contribute to the stability of the ternary complex, which relies on both DAD and CT. Nevertheless, it seems that the loss-of-function defects in the FH2 domain regarding filament end interaction can be compensated by DAD-CT only in the absence of profilin and CPs. This indicates that in a complex biological context, i.e. filopodial elongation or sarcomeric thin filament lengthening, the FH2 domain of DAAM is essential for properly functioning barbed-end interactions.

What is the mechanistic view of the enhancement of FH2-mediated actin assembly by DAD-CT?

DAD-CT can stabilize the structure of the FH2 domain making it a more efficient nucleator, by which it would contribute indirectly, independent from its own actin binding ability, to the core activity of FH2. A similar mode of action was proposed for the FH1 domain of FMNL3 (48). Alternatively, the binding of isolated DAD-CT to actin suggests that DAD-CT can directly interact with actin in their complexes with FH1–FH2–DAD-CT to promote nucleation. In support of this, structural data predict that each of the DAD-CT regions in the FH1–FH2–DAD-CT dimer can establish contacts with an actin monomer (Fig. 10A). This would result in the stabilization of four actin subunits by DAAM, which would completely overcome the structural and kinetic barrier of actin assembly imposed by the nucleation phase. Accordingly, the current model proposes that the FH1–FH2-C terminus forms a tripartite machinery, in which the C terminus serves as a monomer recruitment motif (13, 48). This model implies that the actin monomers captured by DAD-CT would incorporate at pointed ends, which can be interfered with by profilin. In contrast, the model implicates that the affinity of the C-terminal of DAAM and some other formins, which is relatively weak in their isolated forms (Table 2), must be strengthened in their complexes with FH2. This might occur by FH2-mediated structural changes in the C-terminal regions. Alternatively, the FH2 domain by bringing actin subunits into the close proximity of DAD-CT could increase the apparent affinity of the C terminus. In this scenario, the low-affinity C-terminal regions of formins may be involved in the stabilization of the FH2–actin complex, whereas high-affinity C-terminal domains can mediate monomer recruitment (Fig. 10B). Besides nucleation, DAD-CT also supports the interaction of FH2 with the filament ends, as well as its anti-capping efficiency. This is manifested possibly through interactions of the DAD-CT with the sub-terminal actin subunits, consistently with the proposed structural model (Fig. 10) (48). In the presence of the C-terminal regions, the stair stepping of formins requires the dissociation and re-association of both FH2 and DAD-CT, which can influence the processive mode of filament end tracking, as suggested by our data and the work of others (15).

The contribution of the DAD-CT of DAAM in tuning the activities of the FH2 domain is supported by the analysis of its role in neuronal actin dynamics (Fig. 9). Our results point to the importance of the CT region in actin interactions, in good agreement with the biochemical data. Interestingly, the in vivo data suggest that the contributions of the FH2 and CT regions to filopodia formation are comparable. An explanation might be that the CT region of DAAM is not only important for actin interaction but it can also associate with other cytoskeletal regulators, which can contribute to the functioning of DAAM. As examples, Flightless I was shown to directly interact with the C terminus of DAAM and modulate its actin assembly activity; also other formins can bind microtubules that influence their interactions with actin (20, 47, 49).

In conclusion, the C terminus of DAAM shares similar properties to other formins with regard to actin binding and tuning the nucleation-promoting activity of the FH2 domain, as well as to its processive filament end tracking. We also demonstrate that DAD-CT makes the FH2 domain more efficient in antagonizing with capping protein. Our observations suggest that the effects of DAD-CT on the actin nucleation and elongation activities of DAAM are manifested by cooperative structural and/or kinetic stabilization of the interaction of FH2 with actin. Altogether, our work provides support for the idea that the DAD-CT region plays a significant role in modulation of the actin-assembling properties of the Drosophila member of the DAAM formin.

Experimental procedures

Protein purifications and modifications

For bacterial protein expression, cDNAs of DAAM subfragments (DID, 115–356 aa; cDAAM, 568–1153 aa; FH1–FH2, 568–1054 aa; cDAAMΔCT, 568–1116; DAD-CT, 1083–1153 aa; and DAD, 1083–1119 aa) and their mutated versions (FH1–FH2I732A, cDAAMI732A, cDAAMArg–Ala, and DAD-CTArg–Ala) (Fig. 1A) were inserted into pGEX-2T vector (Amersham Biosciences). Constructs were expressed as glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)pLysS strain (Novagen). Transformed bacteria were grown at 37 °C in Luria Broth powder microbial growth medium (Sigma). Protein expression was induced by addition of 1 mm isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside at A600 ∼0.6–0.8. After overnight expression at 20 °C, the bacterial extracts were collected by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 15 min, 4 °C) and stored at −80 °C until use. For protein purification, the bacterial pellet was lysed by sonication in Lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 5 mm DTT, 50 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, 1% sucrose, 10% glycerol supplemented with 1 mm PMSF, 5 mm MgCl2, 0.1 mg/ml DNase, and Protease Inhibitor Mixture (Sigma P8465)). The cell lysate was ultracentrifuged (110,000 × g, 1 h, 4 °C). The supernatant was slowly loaded onto GSH resin (Amersham Biosciences) in a column. For FH domain-containing constructs, the column was sequentially washed with Lysis, Wash1 (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 5 mm DTT, 400 mm NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1% (w/v) sucrose), ATP (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 5 mm DTT, 100 mm KCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 0.25 mm ATP, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 1% (w/v) sucrose), and Wash2 (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 5 mm DTT, 50 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 10 mm KCl, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 1% (w/v) sucrose) buffers. For the C-terminal constructs, lacking the FH domains, the column was washed with Lysis and Wash2 buffers. The proteins were eluted by Wash2 buffer supplemented with 50 mm glutathione-reduced (Sigma G4251), concentrated (Vivaspin 30,000-Da cutoff), and loaded onto PD10 column (GE Healthcare 17-0851-01) for buffer exchange to Storing buffer (50 mm Hepes, pH 7.6, 5 mm DTT, 50 mm NaCl, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 1% (w/v) sucrose). Before flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen, the constructs were clarified by ultracentrifugation (300,000 × g, 30 min, 4 °C) and stored at −80 °C until use. Control experiments showed that a freeze/thaw cycle does not affect the functionality of the constructs (data not shown). Typically, 5–6 g of bacterial pellet yielded 1–1.2 mg/ml protein. The protein concentrations were measured spectrophotometrically using the extinction coefficients at 280 nm and molecular weights derived from the amino acid sequence (ExPASy ProtParam tool http://web.expasy.org/protparam/).3 Actin was purified from rabbit skeletal muscle, gel-filtered on Superdex 200, and stored in G buffer (4 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 0.1 mm CaCl2, 0.2 mm ATP, 0.005% NaN3, 0.5 mm β-mercaptoethanol) according to standard protocols (50, 51). Actin was labeled at Lys328 by Alexa Fluor® 488 carboxylic acid succinimidyl ester (Alexa488NHS, Invitrogen) or at Cys374 by N-(1-pyrene)iodoacetamide (pyrene, Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to standard protocols (21, 28, 52). Mouse profilin 1 was purified as described previously and labeled with Alexa Fluor® C5 568 maleimide (Alexa568C, Invitrogen) (28, 53). Heterodimeric mouse αβ CP and the WH2 domain-containing construct of SALS (SALS-WH2) were purified as described previously (28, 54).

General experimental considerations

Samples at each concentration were prepared individually for experiments. All measurements were performed at 20 °C. The sum of the volume of the proteins and the volume of their storing buffer were constant in the samples and represented a maximum 50% of the total volume of the sample. The concentrations given in the text are final concentrations. In all experiments Mg2+-ATP-actin was used. The actin monomer-bound Ca2+ was replaced by Mg2+ by adding 200 μm EGTA and 50 μm MgCl2 and incubating the samples for 5–10 min at room temperature.

Pyrenyl polymerization assays

The polymerization kinetics of Mg2+-ATP–G-actin was measured using pyrene-actin. The actin concentration was 2 μm that containing 5 or 2% pyrenyl-labeled actin in the case of free G-actin and profilin–G-actin, respectively. In profilin-containing samples, the profilin concentration was 6 μm. The polymerization was initiated by the addition of 1 mm MgCl2 and 50 mm KCl in the absence and presence of different proteins (for exact sample composition and concentrations, see the figure legends). The measurements were performed using a Safas Xenius FLX spectrofluorimeter (λex = 365 nm, λem = 407 nm). To quantitatively analyze the effect of DAAM on actin assembly, the polymerization rates were determined from the slope of the pyrenyl traces at half-maximum polymerization. The relative polymerization rates were derived as the ratio of the polymerization rate measured in the presence of different amounts of DAAM and the polymerization rate of spontaneous actin assembly (Figs. 2B and 4B). For the quantitative analysis of the effect of DID on cDAAM-mediated actin assembly (Fig. 8B), the relative polymerization rate was derived as the ratio of the polymerization rate measured in the presence of cDAAM and different amounts of DID and the polymerization rate measured in the presence of cDAAM and in the absence of DID. The DID concentration dependence of the relative polymerization rate (vrelative) was fit by Equation 1,

| (Eq. 1) |

where v0 and vmin are the relative polymerization rates in the absence and presence of saturating amounts of DID, respectively; [cDAAM0] is the total cDAAM concentration, and [cDAAM: DID] is the concentration of the cDAAM–DID complex, which was derived from the quadratic binding equation.

The antagonistic effect of DAAM with CP was investigated as described (40). Briefly, profilin/G-actin assembly was initiated in the absence of CP and in the presence of different DAAM constructs (200 nm), and then CP at different concentrations was added after ∼120 s to the protein mixtures. Polymerization rates (v) were derived over 40 s just before and 40 s after the addition of CP. The rates were plotted as the function of [CP], and data were fit by Equation 2.

| (Eq. 2) |

where v0 and vmin are the polymerization rates in the absence and presence of saturating amounts of CP, respectively; [CP0] is the total CP concentration, IC50 is the CP concentration required for 50% inhibition.

Steady-state fluorescence experiments

Steady-state anisotropy

To study the DAAM/G-actin interaction, the steady-state anisotropy of Alexa Fluor 488 succinimidyl ester-labeled Mg2+-ATP-G-actin (Alexa488NHS–G-actin) was measured. Alexa488NHS–G-actin (0.2 μm) was incubated with latrunculin A (LatA, 4 μm) for 20 min. Then DAAM constructs were added at different concentrations, and the samples were further incubated for 1 h at 20 °C. In measurements when profilin was present, profilin (0.8 μm) was added to actin after the incubation with LatA, and the samples were further incubated for 30 min at 20 °C, prior to the addition of DAAM constructs. Note that due to the presence of LatA that prevents actin polymerization, the increase in steady-state anisotropy could not result from filament formation; it solely reflects the binding of DAAM constructs to actin. To study the salt dependence of the DAD-CT/G-actin interaction, the ionic strength was set by adding NaCl to the samples (for exact concentrations see Fig. 3A). Anisotropy measurements were performed using a Horiba Jobin Yvon spectrofluorometer (λex = 488 nm, λem = 516 nm; slits, 5 nm). To study the interaction of DAD-CT with profilin/G-actin, steady-state anisotropy measurements were performed using Alexa Fluor 568C5 maleimide-labeled profilin (Alexa568C–profilin). In these experiments Alexa568C–profilin (2 μm) was added to Mg2+-ATP–G-actin (4 μm) bound to LatA (8 μm), and after a 30-min incubation at 20 °C, the samples were supplemented with DAD-CT at different concentrations and further incubated for 1 h at 20 °C. The measurements were performed using a Horiba Jobin Yvon spectrofluorometer (λex = 578 nm, λem = 600 nm; slits, 5 nm). For quantitative analysis, the DAAM concentration dependence of the steady-state anisotropy (r) measured either in the absence or presence of profilin was fit by Equation 3,

| (Eq. 3) |

where A0 and D0 are the total G-actin and DAAM concentration, respectively, rA is the steady-state anisotropy of Alexa488NHS–G-actin/Alexa568C–profilin; rAD is the steady-state anisotropy of Alexa488NHS–G-actin/Alexa568C–profilin at saturating amount of DAAM; and KD is the dissociation equilibrium constant of the G-actin–AAM complex.

J(c) plot measurements

To investigate the effect of cDAAMI732A on the amount of unassembled actin at steady-state critical concentration, measurements were performed as described (21, 28). The cDAAMI732A concentration was 1 μm. For the analysis, J(c) plots were generated ([actin] dependence of the fluorescence emission).

Total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy

The effects of DAAM constructs on the assembly of individual actin filaments were followed by TIRFM, as described previously (21, 28). Glass flow cells were incubated with 1 volume of N-ethylmaleimide myosin for 1 min and then washed with 2 volumes of myosin buffer (4 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 1 mm DTT, 0.2 mm ATP, 0.1 mm CaCl2, 500 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 0.2 mm EGTA) and 2 volumes of 0.1% (w/v) BSA. Finally, flow cells were equilibrated with 2 volumes of TIRFM buffer (0.5% (w/v) methylcellulose, 0.5% (w/v) BSA, 50 mm 1,4-diazabicyclo-[2,2,2]octane, 100 mm DTT in buffer F* (4 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 1 mm DTT, 0.2 mm ATP, 0.1 mm CaCl2, 50 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 0.2 mm EGTA)) before adding the protein mixture (for exact protein composition and concentration see the figure legends). To follow the assembly of free G-actin or profilin/G-actin in the absence and presence of DAAM, a mixture of G-actin (0.5 μm, containing 10% Alexa488NHS–G-actin) and different DAAM constructs in TIRFM buffer was injected into the flow cell. In profilin-containing samples, the profilin concentration was 2 μm. Images were captured every 10 s with an Olympus IX81 microscope equipped with a laser-based (491 nm) TIRFM module using an APON TIRF ×60 NA1.45 oil immersion objective and a CCD camera (Hamamatsu). Images were background corrected before analysis. For analysis of the number of filaments, images were captured 15 min after the initiation of actin polymerization. Filament number was derived from a 66 × 66-μm region of the images by using Fiji. Time-lapse images were analyzed by either the Multiple Kymograph plugin of Fiji or by manually tracking filament growth to derive the elongation rate of actin filaments. Filament length was converted to subunits using 370 subunits/μm filament (55). The elongation rate of actin filaments (v) was related to the critical concentration of actin assembly (cc ∼0.1 μm (1, 2)) to the association rate constant of actin monomers to filament barbed ends (k+) and to the total actin concentration ([G0]) by Equation 4,

| (Eq. 4) |

Actin filament binding and bundling assays

To investigate the interaction of DAD-CT with actin filaments, high-speed centrifugation experiments were performed and analyzed as described (21, 28). In control experiments, we found that the C-terminal constructs appear in the pellet in the absence of F-actin, however at significantly lower amounts than in the presence of actin filaments. Therefore, for quantitative analysis, the amount of self-pelleting DAAM protein was subtracted from the amount of DAAM sedimented in the presence of actin. The final F-actin concentration was 2.5 μm. To study the bundling activity of DAAM constructs, Mg2+-ATP–G-actin (10 μm) was polymerized for 2 h at 20 °C by adding 1 mm MgCl2 and 50 mm KCl. Actin filaments were diluted to 1 μm in F buffer (G buffer supplemented with 1 mm MgCl2 and 50 mm KCl), in the absence and presence of different DAAM constructs and further incubated for 1 h at 20 °C. Samples were centrifuged (14,000 × g, 5 min, 20 °C), and then the supernatants were carefully removed and processed for SDS-PAGE analysis. The protein content of the supernatants was derived from Coomassie Blue-stained gels (Syngene Bioimaging System). Quantification of Coomassie Blue intensities was performed within the linear range of exposure identified by a calibration curve. The intensity values were corrected for the molecular weight of each protein. The relative amount of F-actin in the supernatant was derived as the ratio of the amount F-actin in the absence of any other protein to the amount F-actin in the presence of different proteins.

Genetics

The following fly stocks were used for in vivo overexpression: ElavGAL4C155 or w;elavGAL4 were crossed to w;UASΔDAD-DAAM, w;UASΔDAD-CT-DAAM, w;UASΔDAD-DAAM I732A, w;UASΔDAD-CT-DAAM I732A, w;UAS-ΔDAD-DAAM;UAS-Actin5C::GFP, w;UAS-ΔDAD-CT-DAAM;UAS-Actin5C::GFP.

Primary cell cultures

Drosophila primary neuronal cells were obtained from stage 11 embryos following a protocol published by Sanchez-Soriano et al. (56) with some modifications. In brief, whole embryos were squashed in Schneider's Drosophila (Sigma) medium supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Sigma), 2 μg/ml insulin (Sigma), and penicillin/streptomycin solution (Lonza). Embryonic homogenates were spun at 380 × g for 4 min at room temperature. Pellets were resuspended in complete medium, and the cells were grown at 27 °C on glass coverslips or in glass-bottom Petri dishes for live imaging (MaTek). For filopodia number analysis, primary neurons were fixed 6 h after plating in 4% formaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were washed with PBST (PBS + 0.1% Triton X-100) and then blocked in 5% goat serum diluted in PBST for 10 min. Cells were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C (mouse anti-tubulin 1:1000 (Sigma), rat anti-actin 1:200 (Babraham Bioscience), rabbit anti-HRP 1:200 (Jackson ImmunoResearch), diluted in blocking solution). After overnight incubation, cells were washed in PBST and then incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature (anti-mouse Alexa 405 1:600, anti-rat Alexa 488 1:600, and anti-rabbit Alexa 647 1:600 (Life Technologies, Inc.) diluted in blocking solution). Cells were washed in PBST, and then coverslips were mounted on microscope slides in 70% glycerol. Confocal images were collected with an Olympus FV1000 LSM microscope and edited with ImageJ software.

Live imaging and filopodia dynamics

Filopodia dynamics measurements were performed on 7–9 HIV neurons in culture using an LSM 880 confocal microscope (Zeiss) equipped with a ×40, 1.4 NA oil-immersion lens. To follow actin dynamics, we overexpressed Actin5C::GFP in the cell culture, using a pan-neuronal driver (Elav-Gal4). Imaging of the neurons was performed in glass bottom Petri dishes (MatTek Corp.) in growth media. Fluorescence was excited using the 488-nm line of the argon laser and recorded at a bandwidth of 500–550 nm at an acquisition rate of 1.27 Hz. Filopodia with recognizable extension and retraction phases were selected for further analysis. To measure the extension and retraction speed, kymographs were built using KymoResliceWide, a Fiji plugin dedicated to generate kymographs with improved contrast. Steepness was measured manually and converted to extension and retraction velocities in Excel (Microsoft).

Statistics

The data presented were derived from at least two independent experiments. Values are displayed as mean ± S.D. The number of independent experiments are given in the figure legends. The significance was calculated using two-sample t tests or Z tests considering the number of data and the variance (Excel, Microsoft). The data were analyzed by Kruskal Wallis or one-way analysis of variance considering the distribution of the data. By convention, p ≥ 0.05 was considered as statistically not significant; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; and ****, p < 0.0001. The significance levels are given in the text and on the corresponding figure.

Author contributions

A. T. V. performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and prepared the digital images. I. F. performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and prepared the digital images. Sz. Sz., performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and prepared the digital images. E. M. performed the experiments. R. G. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. M. A. T., T. H., and R. P. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. G. C. S. T. read the article for intellectual content. J. M. conceived and designed the experiments, analyzed the data, and drafted the article. B. B. conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, drafted the article, prepared the digital images.

Supplementary Material