Abstract

Energy homeostasis and oncogenic signaling are critical determinants of the growth of human liver cancer cells, providing a strong rationale to elucidate the regulatory mechanisms for these systems. A new study reports that loss of solute carrier family 13 member 5, which transports citrate across cell membranes, halts liver cancer cell growth by altering both energy production and mammalian target of rapamycin signaling in human liver cancer cell lines and in both an in vitro and in vivo model of liver tumors, suggesting a new target for liver cancer chemoprevention and/or chemotherapy.

Introduction

Liver cancer is a serious disease with poor prognosis (1). Similar to other cancers, liver cancer cells exhibit altered energy balance, including changes in lipid metabolism as well as the glycolytic pathway and TCA2 cycle. Numerous oncogenic signaling pathways also contribute to the etiology of liver cancer (1). Efforts are underway to develop drugs that act on these pathways, such as mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) or the adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase, both of which serve as energy sensors and participate in signaling pathways (2). Additionally, combinatorial approaches that influence more than one molecular target are also being investigated as effective treatments for liver cancer (2), because there remains a need for the development of new approaches to prevent and treat this disease. The metabolite citrate, which participates in both glucose metabolism and energy production, has emerged as potentially impacting a variety of biological processes, including cancer (3,4). Li et al. (5) now explore the cotransporter solute carrier family 13 member 5 (SLC13A5), which exchanges citrate for sodium across cell membranes, showing that its loss, thus switching off citrate transport into liver cancer cells, impacts both energy production and mTOR signaling to effectively block tumorigenicity.

Changes to cellular metabolism have been linked to cancer since Warburg's original report (6) that cancer cells generate energy by switching from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis, which occurs in normal cells when they are deprived of oxygen. One of the major products of glycolysis, pyruvate, is converted to citrate in the mitochondria as part of the TCA cycle; citrate is then exported to the cytosol by the citrate carrier SLC25A1 where its cleavage by the enzyme ATP citrate lyase provides substrates for lipid biosynthesis (7). Given the central role of citrate for multiple metabolic pathways, previous studies have focused primarily on SLC25A1 as a possible target to modulate human health (8). However, cells can also import citrate from the blood stream, where its concentrations greatly exceed those in the mitochondria, via SLC13A5, which is highly expressed in liver cells (9). Although previous work has suggested that SLC13A5 is important in for citrate metabolism in liver and other cells (9), the influence of this citrate transporter on liver cancer cells has not been determined to date.

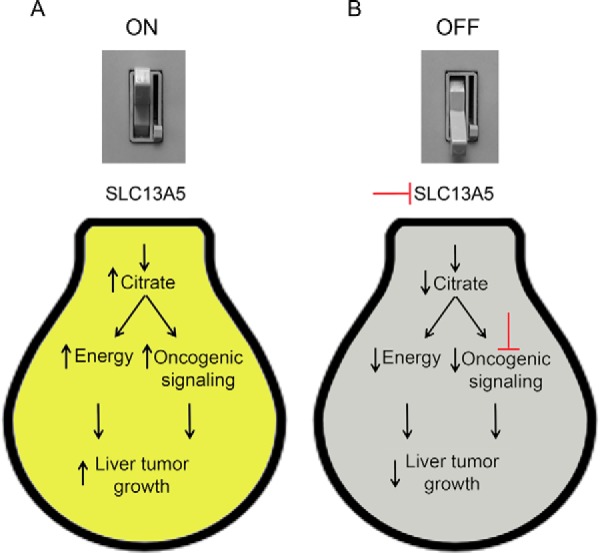

To examine the role of the citrate transporter SLC13A5 in liver cancer, Li et al. (5) used knockdown of SLC13A5 in liver cancer cell lines to monitor the impact on modulating cell growth and oncogenic signaling (Fig. 1). Knocking down SLC13A5 in two human hepatoma cell lines caused a decrease in proliferation and cell cycle arrest at the G1 phase, which were associated with decreased expression of two proteins involved in cell cycle control, p21 and cyclin B1 (5). Interestingly, similar effects were also observed when SLC13A5 was knocked down in an in vitro model of tumorigenicity (anchorage-dependent clonogenicity) and in an in vivo model, ectopic xenografts in mice, derived from human liver cancer cell lines. These observations collectively suggested that citrate transport into liver cancer cells could be critical for tumorigenesis. Indeed, when SLC13A5 was knocked down either in vitro or in vivo, the intracellular concentration of citrate was markedly decreased, and this change was associated with a decreased ATP/ADP ratio and decreased ATP citrate lyase protein and mRNA expression. Moreover, knocking down SLC13A5 caused increased activity of adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase and decreased activity of mTOR. In combination, these results indicate that SLC13A5 is critical for maintaining energy and lipid homeostasis in human liver cancer cells and provide a new link between energy homeostasis and established oncogenic signaling pathways.

Figure 1.

Targeting citrate transport to turn the light out on liver cancer cells. A, when the citrate transporter SLC13A5 is “ON” (expressed), it increases intracellular citrate in liver cancer cells and causes both an increase in energy and lipid homeostasis and also promotes oncogenic signaling by mTOR. This collectively increases liver tumorigenesis. B, as seen in the knockdown studies by Li et al. (5), antibodies or small molecules could inhibit the citrate transporter SLC13A5 (top red T) to switch citrate transport “OFF,” interrupting energy and lipid homeostasis and disrupting tumor growth. Combining these modulators with a compound like rapamycin to inhibit mTOR (bottom red T) could theoretically further improve the efficacy.

There are a number of important findings from these studies that will impact the field of liver carcinogenesis. It is well accepted that energy homeostasis is linked to tumor promotion and progression, so the regulation of the ATP/ADP ratio in liver cancer cells provides new mechanistic details connecting metabolic processes and carcinogenesis. As SLC13A5 also regulated expression of ATP citrate lyase, and this protein is known to influence the levels of lipids that are also required for tumorigenesis, this points to another unique role for this transporter in its ability to modulate energy homeostasis. It is also intriguing to note that SLC13A5 modulated oncogenic mTOR activity, as this protein has already been validated using known drugs such as rapamycin as an effective cancer target.

How can these findings be applied in a clinical setting? First, it will be of great interest to determine whether single nucleotide polymorphisms that either increase or decrease SLC13A5 activity exist. This could help validate the role of SLC13A5 in liver cancer and define precision medicine opportunities for liver cancer patients that possess such putative mutations. Second, SLC13A5 as a potential cancer target would create alternative entry points to control the mTOR pathway using small molecules or antibodies, which may have significant therapeutic potential. Because targeting upstream and downstream molecules within a pathway has proven to be very effective for preventing and treating cancers, the discoveries by Li et al. (5) also provide potential opportunities for combinatorial therapies that could improve treatment outcomes (Fig. 1). In particular, it is possible that liver cancer therapies could be developed that collectively take advantage of targeting SLC13A5 and oncogenic mTOR signaling to cause a “power outage” in liver cancer cells by flipping the switch on citrate transport (Fig. 1).

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants R01CA124533 and R01CA141029. The author declares that he has no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- TCA

- tricarboxylic acid

- mTOR

- mammalian target of rapamycin

- SLC13A5

- solute carrier family 13 member 5.

References

- 1. Cidon E. U. (2017) Systemic treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: Past, present and future. World J. Hepatol. 9, 797–807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bupathi M., Kaseb A., Meric-Bernstam F., and Naing A. (2015) Hepatocellular carcinoma: Where there is unmet need. Mol. Oncol. 9, 1501–1509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Icard P., Poulain L., and Lincet H. (2012) Understanding the central role of citrate in the metabolism of cancer cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1825, 111–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mycielska M. E., Patel A., Rizaner N., Mazurek M. P., Keun H., Patel A., Ganapathy V., and Djamgoz M. B. (2009) Citrate transport and metabolism in mammalian cells: Prostate epithelial cells and prostate cancer. Bioessays 31, 10–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Li Z., Li D., Choi E. Y., Lapidus R., Zhang L., Huang S.-M., Shapiro P., and Wang H. (2017) Silencing of solute carrier family 13 member 5 disrupts energy homeostasis and inhibits proliferation of human hepatocarcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 13890–13901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Warburg O. (1956) On the origin of cancer cells. Science 123, 309–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chypre M., Zaidi N., and Smans K. (2012) ATP-citrate lyase: A mini-review. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 422, 1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Palmieri F. (2013) The mitochondrial transporter family SLC25: Identification, properties and physiopathology. Mol. Aspects Med. 34, 465–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Inoue K., Zhuang L., Maddox D. M., Smith S. B., and Ganapathy V. (2002) Structure, function, and expression pattern of a novel sodium-coupled citrate transporter (NaCT) cloned from mammalian brain. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 39469–39476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]