Abstract

Introduction

Automated control of mechanical ventilation during general anaesthesia is not common. A novel system for automated control of most of the ventilator settings was designed and is available on an anaesthesia machine.

Methods and analysis

The ‘Automated control of mechanical ventilation during general anesthesia study’ (AVAS) is an international investigator-initiated bicentric observational study designed to examine safety and efficacy of the system during general anaesthesia. The system controls mechanical breathing frequency, inspiratory pressure, pressure support, inspiratory time and trigger sensitivity with the aim to keep a patient stable in user adoptable target zones. Adult patients, who are classified as American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status I, II or III, scheduled for elective surgery of the upper or lower limb or for peripheral vascular surgery in general anaesthesia without any additional regional anaesthesia technique and who gave written consent for study participation are eligible for study inclusion. Primary endpoint of the study is the frequency of specifically defined adverse events. Secondary endpoints are frequency of normoventilation, hypoventilation and hyperventilation, the time period between switch from controlled ventilation to assisted ventilation, achievement of stable assisted ventilation of the patient, proportion of time within the target zone for tidal volume, end-tidal partial pressure of carbon dioxide as individually set up for each patient by the user, frequency of alarms, frequency distribution of tidal volume, inspiratory pressure, inspiration time, expiration time, end-tidal partial pressure of carbon dioxide and the number of re-intubations.

Ethics and dissemination

AVAS will be the first clinical study investigating a novel automated system for the control of mechanical ventilation on an anaesthesia machine. The study was approved by the ethics committees of both participating study sites. In case that safety and efficacy are acceptable, a randomised controlled trial comparing the novel system with the usual practice may be warranted.

Trial registration

DRKS DRKS00011025, registered 12 October 2016; clinicaltrials.gov ID. NCT02644005, registered 30 December 2015.

Keywords: adult anaesthesia, adult surgery, clinical trials

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Safety and efficacy of a novel system for the automated control of mechanical ventilation on an anaesthesia machine as well as feasibility of early assisted ventilation during general anaesthesia in terms of a proof-of-concept approach will be assessed using an observational study design.

In case that safety and efficacy are acceptable, a randomised controlled trial comparing the novel system with the usual practice may be warranted. For the design of such a study, the results and the experience obtained with the ’Automated control of mechanical ventilation during general anesthesia study’ (AVAS) would be of benefit.

The clinical value of the AVAS will be limited due to the observational study design.

Introduction

Automated control of mechanical ventilation is a technology which has been introduced in ventilators used in the intensive care unit (ICU). Different systems (eg, Intellivent-Adaptive Support Ventilation,1 SmartCare/PS2 and Neurally Adjusted Ventilator Assist)3 were developed and commercially distributed. When comparing the performance of automated systems with the clinical routine, it has been shown that automated systems are able to keep a patient in a specified target zone (TZ) for a significantly higher percentage of time than clinicians.4 5 Several randomised controlled trials investigated the effect of automated systems on ventilation time in patients who were weaned from mechanical ventilation. In some studies no significant differences in ventilation times were found,6–11 whereas other studies revealed that automated systems shortened the ventilation time12–18 when compared with weaning protocols or usual care.

During general anaesthesia, the physician has to set-up the same ventilator settings as on an intensive care ventilator. However, an automated control of ventilator settings is currently not available on anaesthesia machines. A novel system called smart ventilation control (SVC) was designed. SVC automatically controls the mechanical breathing frequency, inspiratory time, inspiratory pressure, pressure support and triggers sensitivity and was implemented on an anaesthesia machine (Zeus Infinity Empowered, Drägerwerk AG & Co. KGAa, Lübeck, Germany). The system is designed to adapt the ventilatory settings to keep a patient stable in a TZ. Furthermore, spontaneous breathing activity will be supported as soon as possible. In this paper we describe the design of the first clinical study that will be performed with SVC during general anaesthesia.

Methods and analysis

The ‘Automated control of mechanical ventilation during general anesthesia study’ (AVAS) is an international investigator-initiated bicentric observational study investigating the application of SVC during general anaesthesia. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the Christian-Albrechts-University of Kiel, Germany (A154/14) by the Ethics Committee of the county Niederösterreich (GS-1-EK-3/118–2016) and is registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02644005). The study protocol is available as online supplementary appendix. The main objective of this study is to describe the application of SVC and to assess its safety and efficacy.

bmjopen-2016-014742supp001.pdf (212.1KB, pdf)

Description of the system

SVC controls automatically the following ventilator settings:

Mechanical breathing frequency (f mech)

Inspiratory pressure (P insp)

Pressure support (PS)

Inspiratory time (TI)

Trigger sensitivity (TS)

Inspired fraction of oxygen and positive end-expiratory pressure are not controlled automatically. SVC adjusts the ventilator settings with the aim to keep a patient stable in a TZ. Numerous predefined TZs exist that can be set according to the current therapeutic situation. All TZs can be customised by the user for each individual patient and consist of upper and lower limits for tidal volume (VT) and for the end-tidal partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PetCO2). Based on these limits, the system classifies the current quality of ventilation, called classification of ventilation, and derives new ventilator settings accordingly. This is done every 15 s. The physician always has the opportunity to change the ventilator settings manually or to stop the system. If SVC detects spontaneous breathing activity, the mechanical breathing frequency is decreased automatically with the aim to increase the portion of spontaneous ventilation adequately if ‘augmented ventilation’ is activated. In case that ‘encourage spontaneous breathing’ is activated, SVC will automatically change the ventilator mode from controlled mechanical ventilation (pressure controlled ventilation) to assisted ventilation (pressure support ventilation) if PetCO2 is classified as mild hypoventilation. The patient is continuously monitored for possible instabilities. Lastly, the physician is supported in the recovery process of general anaesthesia by supporting the induction of spontaneous breathing and by checking whether the respiratory drive of the patient is sufficient for extubation.

SVC is available as a software option on Zeus Infinity Empowered anaesthesia machines (Drägerwerk AG & Co. KGAa, Lübeck, Germany) and is approved as a medical product according to 93/42/European Economic Community (EEC).

Patient screening

The study team (study nurses and study physicians) will screen consecutively for eligible patients the day before surgery. Possible study candidates will be informed about the study in detail and asked to give consent for study participation.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The following inclusion criteria will be used:

Elective surgery of the upper limb, lower limb or peripheral vascular surgery in general anaesthesia without any additional regional anaesthesia technique.

Patient is classified as American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status I, II or III.

Age ≥18 years.

Written consent of the patient for study participation.

Patients will be excluded when meeting one or more of the following exclusion criteria:

Mild, moderate or severe acute respiratory distress syndrome.19

Known chronic obstructive pulmonary disease Gold stage III or higher.20

Known neuro-muscular disease.

Patient is pregnant.

Two or more of the following acute organ failures or haemodynamic instability defined as systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg, mean arterial pressure <70 mm Hg or administration of any vasoactive drugs or acute renal failure defined as oliguria, that is, urine output <0.5 mL/kg/hour for at least 2 hours despite of adequate management or creatinine increase >0.5 mg/dL or cerebral failure: loss of consciousness or encephalopathy.

Study procedure

All patients will be ventilated with SVC. As SVC does not control the inspired fraction of oxygen (FIO2) and positive end-expiratory pressure, the user will have to set up both of these settings during the whole general anaesthesia with the aim to reach a peripheral saturation of oxygen (SpO2) >95%.

Anaesthesia will be performed by a physician of the study team who has been trained in using SVC. The physician can overrule or stop the system at any time if this is necessary for patient safety. Reasons for stopping or overruling will be documented. Insertion of a tube for gastric decompression is part of our routine clinical practice in endotracheally intubated patients. For this study, we will use a gastric tube for decompression that is additionally equipped with an oesophageal balloon for assessment of oesophageal pressure (Nutrivent, Sidam, Mirandola, Italy).

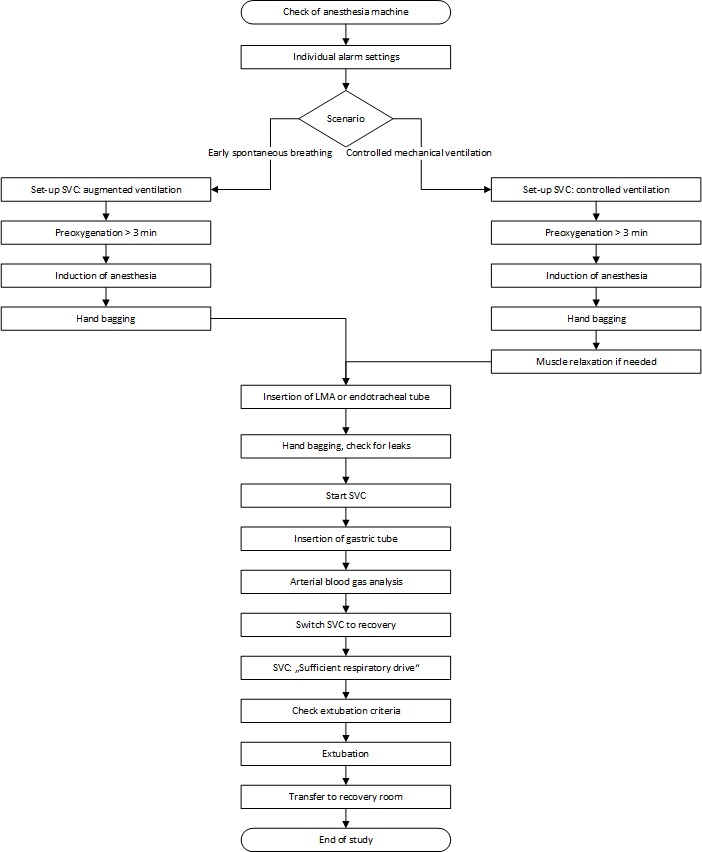

Two different study scenarios are possible according to the surgical procedure (figure 1): (i) Early spontaneous breathing: Patient is allowed to breathe spontaneously immediately after induction of the general anaesthesia. (ii) Controlled mechanical ventilation: Patient will be ventilated in a controlled ventilation mode as long as needed for the surgical procedure. Then, spontaneous breathing will be allowed as soon as possible.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study procedure. LMA, laryngeal mask; SVC, smart vent control.

The study will proceed as follows:

I. Early spontaneous breathing

Checking of the anaesthesia machine.

Setting of the individual alarm settings.

- Setting of SVC:

- level of ventilation, airway and lung mechanics as clinically indicated

- ventilation regime: augmented ventilation.

Preoxygenation of the patient with an FIO2=1 for at least 3 min.

Induction of the general anaesthesia with an opioid (remifentanile, fentanyle or sufentanile) and propofol.

Hand bagging.

Insertion of the laryngeal mask or the endotracheal tube.

Hand bagging while checking for significant leakage (laryngeal mask) and doing correction if needed.

Continuous infusion of remifentanile and propofol or administration of sevoflurane.

Start of SVC.

Insertion and position check of a gastric tube (if clinically indicated).

Arterial blood gas analysis 15 min after the beginning of the surgical procedure (if clinically indicated).

Stopping of the continuous infusion of remifentanile and propofol (or sevoflurane) immediately after the end of the surgical procedure and switch SVC ventilation regime to ‘Recovery’.

II. Controlled mechanical ventilation

Checking of the anaesthesia machine.

Setting of the individual alarm settings.

- Setting of SVC

- level of ventilation, airway and lung mechanics as clinically indicated

- ventilation regime: controlled ventilation.

Preoxygenation of the patient with an FIO2=1 for at least 3 min.

Induction of the general anaesthesia with an opioid (remifentanile, fentanyle or sufentanile) and propofol.

Hand bagging.

Administration of muscle relaxant agent (rocuronium, cis-atracurium or succinylcholine) if needed.

Start of train-of-four (TOF) measurement (every 10 min).

Insertion of the laryngeal mask or endotracheal tube.

Hand bagging while checking for significant leakage and doing correction if needed.

Continuous infusion of remifentanile and propofol or administration of sevoflurane.

Start of SVC.

Insertion and position check of a gastric tube (if clinically indicated).

Arterial blood gas analysis 15 min after the begin of the surgical procedure (if clinically indicated).

If TOF ≥2 stepwise decrease of remifentanile and propofol (or sevoflurane) with the aim to allow spontaneous breathing activity and switch the SVC system to ‘Augmented Ventilation’.

If no spontaneous breaths are detected during 20 min, the SVC system will be switched to ‘Encourage Spontaneous Breathing’.

Stop of the continuous infusion of remifentanile and propofol (or sevoflurane) immediately after the end of the surgical procedure and switch SVC ventilation regime to ‘Recovery’.

Extubation

Readiness for extubation is given when SVC proposes separation from the ventilator. Extubation will be performed when the following criteria are satisfied: patient is awake and cooperative, sufficient airway protection or the Glasgow Coma Scale >8 and no surgical contraindication. After extubation, the patients will be monitored for at least 5 min in the operating room (OR). The study period ends with the initiation of the patients’ transfer from the OR to the recovery room.

Study endpoints

Primary endpoint of the study is the frequency of AE defined as follows:

Severe hypoventilation defined as minute volume <40 mL/kg predicted body weight for >5 min.

Apnoea for >90 s.

Hyperventilation defined as PetCO2<5 mm Hg of the lower target setting for SVC for >5 min. The responsible anesthesiologist defines a target for the arterial PaO2 of carbon dioxide (PaCO2_target) before the induction of the general anaesthesia and sets the corresponding end-tidal CO2 range in the automated ventilation system. Fifteen minutes after the beginning of the surgical procedure, an arterial blood gas analysis may be performed and PaCO2 will be measured.

Hypoventilation defined as PetCO2>5 mm Hg of the upper target setting for the SVC for >5 min.

Respiratory rate >35 breaths per minute for>5 min.

Any override or stop of the automated controlled ventilation settings by the anesthesiologist in charge if the settings are clinically not acceptable. Reasons for overriding or stopping the system will be noted.

Secondary endpoints are as follows:

- Frequency of normoventilated, hypoventilated and hyperventilated patients. Patients will be classified as follows:

- Hypoventilated patient: PaCO2 > (PaCO2_target + 5 mm Hg).

- Hyperventilated patient: PaCO2 < (PaCO2_target – 5 mm Hg).

- Normoventilated patient: (PaCO2_target − 5 mm Hg) ≤ PaCO2 ≤ PaCO2_target + 5 mm Hg.

Time period between the switch from controlled to assisted ventilation and achievement of stable assisted ventilation of the patient.

Proportion of time within the TZ for VT and PetCO2 as individually set up for each patient by the user.

Frequency of alarms.

Frequency distribution of VT, P insp, TI, expiration time and PetCO2.

Number of re-intubations.

End-point determination

The end-points of the study are evaluated using the recorded and protocolled data of the study team only during mechanical ventilation with activated SVC.

Data recording

After study inclusion the following demographic characteristics will be documented: patients’ age, sex, height, weight, date and type of surgery. Beginning with the time of the study period, all available data from the ventilator will be recorded via the MEDIBUS interface. In detail, flow, pressure and expired CO2 will be stored every 8 ms (‘fast data’), and all ventilator settings, measurements and alarms will be stored at least every second (‘slow data’). All SVC patient session journal files will be systematically stored. Heart rate, SpO2 and arterial blood pressures will be recorded at least every 5 min. In patients with a gastric tube, oesophageal pressure swings will be recorded continuously (‘fast data’) until extubation. Data will be pseudonymised and then stored in a secured web space.

Rules for early termination of the study

During each treatment of a patient in this study, the investigator can stop the study procedure when the ventilator settings controlled by SVC are clinically not appropriate or in case of a technical failure of the SVC system. The study will be terminated if the study procedure is stopped by the investigator (as described above) in five consecutive patients.

Statistical considerations

We estimated a frequency of 3%–5% for the AE. Therefore, a sample size of n=100 patients seems reasonable. Descriptive statistical analyses (mean±SD, median and 95% CI where appropriate) will be used.

Ethics and dissemination

In contrast to conventional anaesthesia machines, automated control of mechanical ventilation is steadily increasing in ICU ventilators. The commercially available systems cover the control of one ventilator setting, that is the pressure support level during weaning (SmartCare/PS)2, minute ventilation (mandatory minute ventilation,21 adaptive support ventilation (ASV))22–25 or even all ventilatory settings (Intellivent-ASV).1 SVC provides an automated control of minute ventilation by adapting TI, f mech, P insp and PS and supports spontaneous breathing activity as soon as possible by decreasing f mech and by switching between pressure controlled and pressure support ventilation. It has been shown that the suppression of spontaneous breathing activity contributes to ventilator-induced lung injury,26 leads to ventilator-induced diaphragmatic dysfunction27 and increases the risk of developing pneumonia when increasing ventilation time in ICU patients.28 It is known that the induction of a general anaesthesia leads to a cranial movement of the diaphragm-provoking atelectasis.29 Putensen et al showed nicely that the early use of assisted ventilation leads to recruitment of atelectatic lung regions and thereby improves lung mechanics and gas exchange in patients at high risk of developing lung injury.30 Therefore, an automated system that supports assisted ventilation as early as possible may have beneficial effects like decreasing the frequency of pulmonary complications, the amount of anaesthesia and vasoactive drugs and recovery time. However, in this study with the first SVC use in patients, we focus on the safety and efficacy of the system and assess the feasibility of early assisted ventilation during general anaesthesia in terms of a proof-of-concept approach. In case that safety and efficacy are acceptable (ie, the study was not stopped per the early termination rule) in this study, a randomised controlled trial comparing SVC with the usual practice may be warranted. As spontaneous breathing may not be acceptable or possible during some surgical procedures (eg, neuromuscular blockade needed for the surgical procedure), we designed two different study scenarios (early spontaneous breathing and controlled mechanical ventilation).

Regarding the study design one may argue that a prespecified list for overruling or stopping the system may be provided to the study physicians. Such a list may prohibit inaccurate overriding or stopping of SVC. From our point of view, it is the responsibility and the ethical duty of the study physician to override the ventilatory settings provided by SVC or even stop SVC for any safety reason. Should a list of possible reasons for overruling or stopping be defined in the study protocol, the individual decision of the study physician might be limited or influenced. Therefore, we decided not to provide such a list. We plan to categorise reasons for overriding or stopping SVC after the completion of the whole study.

A three-step dissemination strategy is planned as follows: first, the study results will be presented at international anaesthesia conferences; second, the study will be published in a peer-reviewed journal and third, a multicentre randomised controlled study will be designed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Stefan Mersmann, Drägerwerk AG & Co. KGaA, Lübeck, Germany for excellent support especially in the description of the Smart Vent Control system.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors participated in the design of the study and were involved in writing the study protocol. DS drafted the first version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to drafting the manuscript, and read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: Drägerwerk AG & Co. KGAa, Lübeck, Germany provides a restricted research grant and one anesthesia machine equipped with Smart Vent Control for the conduction of the study to each of the participating study sites.

Competing interests: DS, TB, IF, NW and CH received lecture fees from Drägerwerk AG & Co. KGAa, Lübeck, Germany. DS received consultant honoraria from Drägerwerk AG & Co. KGAa, Lübeck, Germany.

Ethics approval: Ethics Committe of the Medical Faculty of the Christian-Albrechts-University of Kiel, Ethics Committeeof the County Niederösterreich.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Arnal JM, Wysocki M, Novotni D, et al. . Safety and efficacy of a fully closed-loop control ventilation (IntelliVent-ASV) in sedated ICU patients with acute respiratory failure: a prospective randomized crossover study. Intensive Care Med 2012;38:781–7. 10.1007/s00134-012-2548-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dojat M, Brochard L, Lemaire F, et al. . A knowledge-based system for assisted ventilation of patients in intensive care units. Int J Clin Monit Comput 1992;9:239–50. 10.1007/BF01133619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sinderby C, Navalesi P, Beck J, et al. . Neural control of mechanical ventilation in respiratory failure. Nat Med 1999;5:1433–6. 10.1038/71012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dojat M, Harf A, Touchard D, et al. . Evaluation of a knowledge-based system providing ventilatory management and decision for extubation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;153:997–1004. 10.1164/ajrccm.153.3.8630586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lellouche F, Bouchard PA, Simard S, et al. . Evaluation of fully automated ventilation: a randomized controlled study in post-cardiac surgery patients. Intensive Care Med 2013;39:463–71. 10.1007/s00134-012-2799-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Burns KE, Meade MO, Lessard MR, et al. . Wean earlier and automatically with new technology (the WEAN study). A multicenter, pilot randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;187:1203–11. 10.1164/rccm.201206-1026OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dongelmans DA, Veelo DP, Bindels A, et al. . Determinants of tidal volumes with adaptive support ventilation: a multicenter observational study. Anesth Analg 2008;107:932–7. 10.1213/ane.0b013e31817f1dcf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Petter AH, Chioléro RL, Cassina T, et al. . Automatic ‘respirator/weaning’ with adaptive support ventilation: the effect on duration of endotracheal intubation and patient management. Anesth Analg 2003;97:1743–50. 10.1213/01.ANE.0000086728.36285.BE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rose L, Presneill JJ, Johnston L, et al. . A randomised, controlled trial of conventional versus automated weaning from mechanical ventilation using SmartCare/PS. Intensive Care Med 2008;34:1788–95. 10.1007/s00134-008-1179-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schädler D, Engel C, Elke G, et al. . Automatic control of pressure support for ventilator weaning in surgical intensive care patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;185:637–44. 10.1164/rccm.201106-1127OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stahl C, Dahmen G, Ziegler A, et al. . Comparison of automated protocol-based versus non-protocol-based physician-directed weaning from mechanical ventilation. Intensivmedizin und Notfallmedizin 2009;46:441–6. 10.1007/s00390-009-0061-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Celli P, Privato E, Ianni S, et al. . Adaptive support ventilation versus synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation with pressure support in weaning patients after orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplant Proc 2014;46:2272–8. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2014.06.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gruber PC, Gomersall CD, Leung P, et al. . Randomized controlled trial comparing adaptive-support ventilation with pressure-regulated volume-controlled ventilation with automode in weaning patients after cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology 2008;109:81–7. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31817881fc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kirakli C, Naz I, Ediboglu O, et al. . A randomized controlled trial comparing the ventilation duration between adaptive support ventilation and pressure assist/control ventilation in medical patients in the ICU. Chest 2015;147:1503–9. 10.1378/chest.14-2599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kirakli C, Ozdemir I, Ucar ZZ, et al. . Adaptive support ventilation for faster weaning in COPD: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Respir J 2011;38:774–80. 10.1183/09031936.00081510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lellouche F, Mancebo J, Jolliet P, et al. . A multicenter randomized trial of computer-driven protocolized weaning from mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:894–900. 10.1164/rccm.200511-1780OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sulzer CF, Chioléro R, Chassot PG, et al. . Adaptive support ventilation for fast tracheal extubation after cardiac surgery: a randomized controlled study. Anesthesiology 2001;95:1339–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhu F, Gomersall CD, Ng SK, et al. . A randomized controlled trial of adaptive support ventilation mode to wean patients after fast-track cardiac valvular surgery. Anesthesiology 2015;122:832–40. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Force ADT, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. . Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin definition. JAMA 2012;307:2526–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Global Initiative for chronic obstructive lung diesease. Pocket guide to COPD diagnosis, management and prevention. Secondary Global Initiative for chronic obstructive lung diesease. Pocket guide to COPD diagnosis, management and prevention. 2010. http://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/wms-GOLD-2017-Pocket-Guide.pdf (accessed 26 oct 2015).

- 21. Hewlett AM, Platt AS, Terry VG, et al. . A new concept in weaning from mechanical ventilation. Anaesthesia 1977;32:163–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brunner JX, Iotti GA. Adaptive support ventilation (ASV). Minerva Anestesiol 2002;68:365–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Campbell RS, Sinamban RP, Johannigman JA, et al. . Clinical evaluation of a new closed loop ventilation mode: adaptive supportive ventilation (ASV). Critical Care 1999;3:P038. 10.1186/cc413 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tehrani FT. United States patent US patent. 1991;4:268. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tehrani FT. Automatic control of an artificial respirator. Proc IEEE EMBS Conf 1993;1991:1738–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Putensen C, Hering R, Wrigge H. Controlled versus assisted mechanical ventilation. Curr Opin Crit Care 2002;8:51–7. 10.1097/00075198-200202000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Levine S, Nguyen T, Taylor N, et al. . Rapid disuse atrophy of diaphragm fibers in mechanically ventilated humans. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1327–35. 10.1056/NEJMoa070447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cook DJ, Walter SD, Cook RJ, et al. . Incidence of and risk factors for ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients. Ann Intern Med 1998;129:433–40. 10.7326/0003-4819-129-6-199809150-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Froese AB, Bryan AC. Effects of anesthesia and paralysis on diaphragmatic mechanics in man. Anesthesiology 1974;41:242–55. 10.1097/00000542-197409000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Putensen C, Zech S, Wrigge H, et al. . Long-term effects of spontaneous breathing during ventilatory support in patients with acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:43–9. 10.1164/ajrccm.164.1.2001078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014742supp001.pdf (212.1KB, pdf)