Abstract

Objective

To investigate the relationship between temperature extremes and daily number of deaths in Jinan, a temperate city in northern China.

Methods

Data ondaily number of deaths and meteorological variables over the period of 2011–2014 were collected. Cold spells or heat waves were defined as ≥3 consecutive days with mean temperature ≤5th percentile or ≥95th percentile, respectively. We applied a time-series adjusted Poisson regression to assess the effects of extreme temperature on deaths.

Results

There were 152 150 non-accidental deaths over the study period in Jinan, among which 87 607 people died of cardiovascular disease, 11 690 of respiratory disease, 33 001 of stroke and 6624 of chronic obstrutive pulmonary disease (COPD). Cold spells significantly increased the risk of deaths due to non-accidental mortality (RR 1.08, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.11), cardiovascular disease (RR 1.06, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.10), respiratory disease (RR 1.19, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.27), stroke (RR 1.11, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.17) and COPD (RR 1.27, 95% CI 1.16 to 1.38). Heat waves significantly increased the risk of deaths due to non-accidental mortality (RR 1.02, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.05), cardiovascular disease (RR 1.03, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.06) and stroke (RR 1.06, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.13). The elderly were more vulnerable during heat wave exposure; however, vulnerability to cold spell was the same for the whole population regardless of age and gender.

Conclusions

Both cold spells and heat waves have increased the risk of death in Jinan, China.

Keywords: Temperature extremes, Mortality, Poisson regression, Time series

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study was the first to examine the effects of both cold spells and heat waves on mortality in the city of Jinan, China.

A large and recent database with mortality data of >152 000 non-accidental deaths was analysed to achieve robust results.

Air pollution levels were not included due to the unavailability of data.

Ecological bias based on population data was inevitable. Generalisation of the study findings should be made with caution given that data from only one city were included in the study.

Introduction

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has predicted that extreme temperature events will become more frequent and more intense as the global mean temperature rises.1 For example, the heat wave in 1987 in Athens and in 1995 in Chicago caused thousands of deaths.2 In Europe and Russia, an increase in the occurrence of extreme temperature events has been observed, such as the devastating heat waves in 2003 and 2010.3 4 Parts of eastern Asia also experienced an extremely hot summer in 2010.5 In 2014, parts of Canada and the Eastern United States experienced such an extreme period of cold weather that it broke 100-year low-temperature records in the USA (https://www.climate.gov/news-features/event-tracker/polar-vortex-brings-cold-here-and-there-not-everywhere). In 2008, southern China experienced a severe continuous cold spell of a long duration, with estimated direct economic losses of more than US$22.3 billion. This event is considered a once in 50–100 years event.6 In the summer of 2013, the strongest intensity of heat waves since 1951 occurred in southern China.7

Temperature extremes are a threat to human health and are associated with increased mortality risk.8 9 The temperature-mortality relationship has been variously described as having U, V or J shapes, with increased mortality at cold and hot temperatures.10 11 Increasing mortality due to extreme temperatures has been reported in many countries, for example, Europe, Russia, USA, Australia and China.12 13 There is a lack of studies in developing countries exploring the association between extreme temperature and mortality. Additionally, reported heterogeneity of the effects of extreme temperatures on mortality varies greatly across regions.6 14 Limited studies have examined the impacts of extreme temperature on mortality in China and many previous studies were conducted in subtropical zones of southern China.15

Jinan, the capital of Shandong province in Eastern China, is located in a temperate climatic zone. Being surrounded by mountains in the south, Jinan has unique weather conditions with very hot summers and cold winters.16 However, there has been not a clear picture on the effects of both extreme cold and hot temperatures on mortality in the city, which was not included in the previous publication on weather mortality in 66 communities in China.15 Our previous study in Jinan found that heat waves significantly increased the risk of mortality and caused 24.88% excess non-accidental deaths.17 This study used more recent data to investigate the effect of both heat waves and cold spells on the daily number of deaths in Jinan. Furthermore, we have explored the effect of temperature extremes on vulnerable populations.

Materials and methods

Data collection

Jinan is located at latitude 36° 40′N and longitude 116° 57′E, with seven districts, and three counties. Its population was 7 067 900 in 2014 with an urban population of 4 693 700 (Shandong Provincial Statistical Yearbook 2015). Jinan has a temperate climate with four well-defined seasons. The city is dry and nearly rainless in spring, hot and rainy in summer, crisp in autumn and dry and cold in winter. The average annual temperature is 14.70°C and average total annual rainfall is 670 mm (China Meteorological Administration).

Mortality data were obtained from the China Information System for Death Register and the Report of Jinan Municipal Centre for Disease Control and Prevention from 1 January 2011 to 31 December 2014. The mortality data were from 10 administrative divisions. We classified non-accidental mortality according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10 codes A00–R99). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (ICD-10 codes J40-J44, J47), cardiovascular disease (ICD-10 codes I00–I99), respiratory disease (ICD-10 codes J00–J99) and stroke (ICD-10 codes I60-I69) were examined separately.

Daily meteorological data over the same period, including daily maximum, mean, and minimum temperature and relative humidity (RH), were obtained from the China Meteorological Data Sharing Service System (CMDSSS). We did not include air pollution levels in our model due to data unavailability.

Data analysis

Relationship between daily number of deaths and overall temperatures

A descriptive analysis was performed to understand the time-series characteristics of the daily number of deaths and meteorological variables over the study period. Given that previous studies have reported a non-linear relationship between temperature and mortality, non-parametric Spearman correlation analysis was performed. Cross-correlation analysis was also performed with relevant lag values given the potential lagged effect of temperature.

Relationship between daily number of deaths and temperature extremes

Analysis of temperature extremes was restricted to the winter seasons (November–March) and summer seasons (May–August) in 2011–2014 in this study. A heat wave was defined as a period of at least 3 consecutive days with daily mean temperature above the 95th percentile (29.0°C) from May to August during the study period; a cold spell was defined as a period of at least 3 consecutive days with daily mean temperatures below the 5th percentile (−3.8°C) from November to March during the study period. We did not investigate the risks due to different characteristics of heat waves and cold spells due to the similar features of these waves observed from this study area.

Independent-sample t-test was used to compare the difference of the average number of non-accidental deaths and cause-specific deaths between the cold spell/heat wave exposure days and non-exposure days. Time-series adjusted Poisson regression was applied to quantify the impacts of a cold spell/heat wave on the daily number of deaths at different lag days. Contributing factors such as long-term and seasonal trends, day of week (DOW), RH and ambient temperature were controlled in the model as potential confounders. No over-dispersion was detected in our data, and the model used in the analysis can be described as:

Log[E(Yt)]=α+βTmint +ηDOWt+γStratat+λRHt+δEDt

where t is the day of the observation; Yt is the observed daily death counts on day t; α is the intercept; Tmin is mean temperature on day t, and β is vector of coefficients; DOW is day of the week on day t, and η is vector of coefficients; Stratat is a categorical variable of the year and calendar month used to control for season and trends, and γ is vector of coefficients; RH is RH on day t, and λ is vector of coefficients; ED(exposure days)t is a binary variable that is ‘1’ if day t was an extreme temperature exposure day (cold spell/heat wave), and δ is the coefficient.

Relative risks were estimated by the regression. Population vulnerability was examined based on age and gender of deceased cases.

All statistical tests were two-sided and values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant. Stata12 was used for the analysis.

Results

Relationship between daily number of deaths and overall temperature

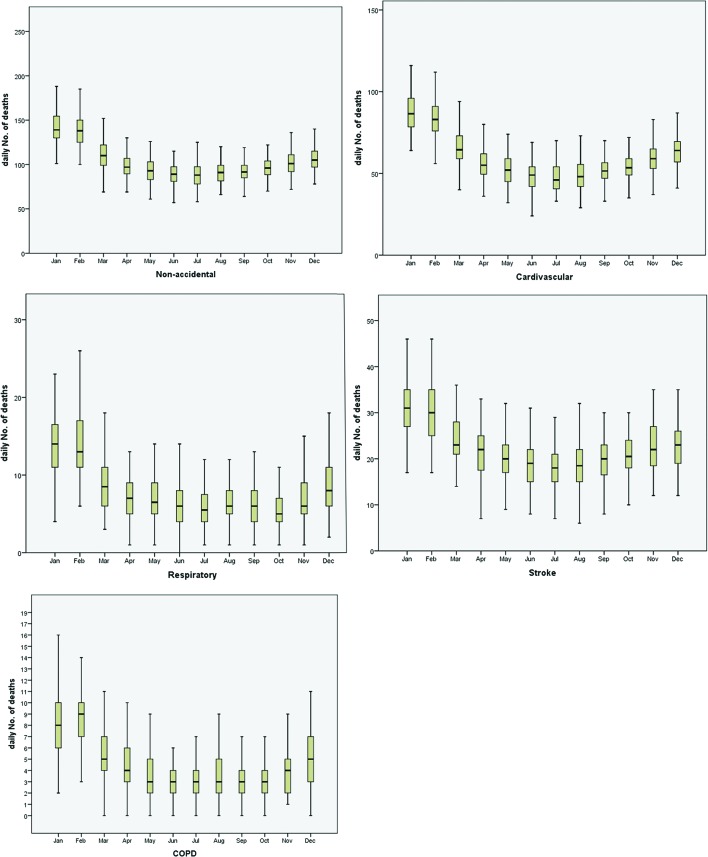

There were 152 150 total non-accidental deaths over the study period in Jinan, among which 87 607 persons (57.5%) died of cardiovascular disease, 11 690 (7.7%) of respiratory disease, 33 001 (21.7%) of stroke and 6624 (4.3%) of COPD. The average daily number of deaths observed was 104.1 for non-accidental mortality, 59.9 for cardiovascular disease, 8.0 for respiratory disease, 22.6 for stroke and 4.5 for COPD. The average daily mean temperature and mean RH were 14.7°C (range −9.4°C to 34°C) and 55% (range 13% to 100.0%), respectively. The 5th and 95th percentiles of temperature were −3.6°C and 29°C, respectively (table 1). Additionally, a clear seasonal distribution of daily number of deaths was observed for all categories of mortality with most cases occurring in winter (December-February) and the least cases in summer (June-August) (figure 1).

Table 1.

Summary of the daily number of deaths and weather conditions in Jinan, China, 2011–2014

| Variables | Mean | SD | Minimum | 5th percentile | 95th percentile | Maximum |

| Death | ||||||

| Non-accidental | 104.1 | 22.4 | 57 | 75 | 149 | 210 |

| Cardiovascular | 59.9 | 16.5 | 24 | 38 | 93 | 130 |

| Respiratory | 8 | 4.1 | 0 | 3 | 16 | 26 |

| Stroke | 22.6 | 6.8 | 5 | 13 | 35 | 46 |

| COPD | 4.5 | 2.9 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 19 |

| Weather variables | ||||||

| Mean temperature | 14.7 | 10.7 | −9.4 | −3.6 | 29 | 34 |

| Mean RH | 55 | 20 | 13 | 24 | 90 | 100 |

| Temperature(°C) | ||||||

| Spring (March-May) | 16 | 7.4 | -8 | 3.9 | 26.3 | 34 |

| Summer (June-August) | 26.5 | 2.8 | 16.3 | 21.6 | 30.9 | 33 |

| Fall (September-November) | 15.3 | 6.3 | -8 | 4.9 | 23.9 | 28 |

| Winter (December-February) | 0.6 | 4.5 | −9.4 | −6.6 | 8.5 | 11.3 |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; RH, relative humidity.

Figure 1.

Seasonal distribution of daily number of deaths in Jinan, China. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The cross-correlation analysis showed that all non-accidental and cause-specific deaths were significantly correlated with mean temperature with lagged effects ranging from 7 to 15 days (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cross-correlation between mortality and daily mean temperature in Jinan, China

| Mortality type | Maximum coefficient | p Value | Lag time (days) |

| Non-accidental | −0.656 | 0.000 | 15 |

| Cardiovascular | −0.678 | 0.000 | 15 |

| Respiratory | −0.551 | 0.000 | 14 |

| Stroke | −0.518 | 0.000 | 7 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | −0.544 | 0.000 | 14 |

Relationship between daily number of deaths and temperature extremes

There were seven cold spells ranging from 3 to 6 days in duration in 2011–2014. The lowest minimum temperature and highest minimum temperature were −12.9°C and −3.2°C, respectively. Eight heat waves lasting a total of 39 days were identified during the study period. The lowest maximum temperature and highest maximum temperature were 33.1°C and 39.1°C, respectively (table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of cold spells and heat waves in Jinan, China

| Year | Date of start | Duration (days) | Lowest minimum temperature (°C) | Highest minimum temperature(°C) | Maximum temperature(°C) |

| Cold spells | |||||

| 2011 | Jan 14 | 6 | −11.6 | −3.2 | 3 |

| Jan 22 | 3 | −9 | −4.5 | 5.4 | |

| 2012 | Jan 20 | 5 | −10.7 | −3.4 | 4 |

| Feb 1 | 3 | −10.4 | −6.1 | 4.8 | |

| Dec 23 | 4 | −11.8 | −9.3 | 0 | |

| 2013 | Jan 2 | 4 | −12.9 | −9.5 | 5 |

| 2014 | Feb 9 | 3 | −11.2 | −6.8 | 1.3 |

| Heat waves | |||||

| 2011 | Jul 22 | 3 | 33.4 | 36.8 | 25.7 |

| 2012 | Jun 17 | 6 | 34.7 | 36.9 | 22.9 |

| Jul 25 | 6 | 33.7 | 36.9 | 24.7 | |

| 2013 | Jul 6 | 3 | 34.5 | 37.2 | 22.2 |

| Aug 4 | 4 | 33.1 | 35.6 | 22.2 | |

| Aug 11 | 6 | 34.6 | 38.2 | 21.0 | |

| 2014 | May 27 | 5 | 36 | 39.1 | 20.7 |

| Jul 16 | 6 | 33.4 | 37.6 | 24 | |

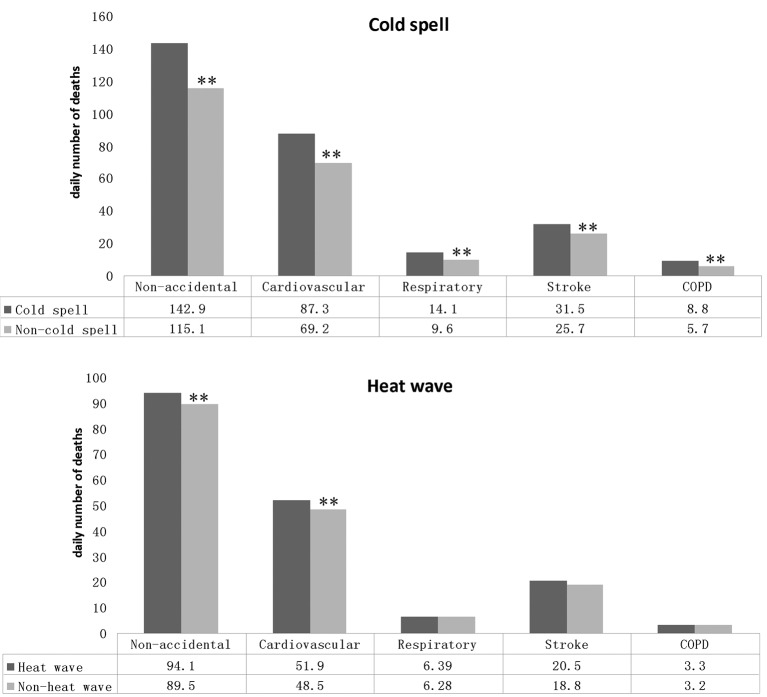

There were a total of 72 416 non-accidental deaths during winter seasons over the study period in Jinan. Of these deaths, 43 698 persons (60.3%) died of cardiovascular disease, 6291 (8.6%) of respiratory disease, 15 973 (22.1%) of stroke and 3786 (5.2%) of COPD. A total of 44 729 non-accidental deaths were reported during summer seasons over the study period, among which 54.4% (24 369) of deaths were from cardiovascular disease, 6.9% (3106) from respiratory disease, 21.1% (9423) from stroke and 3.5% (1607) from COPD. Both cold spells and heat waves were associated with increased mortalities. Cold spells were statistically significant for all examined deaths, while for heat waves the significance was most pronounced for non-accidental and cardiovascular mortality but not for the others (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of the average daily number of deaths between cold spell/heat wave days and non-exposure days. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

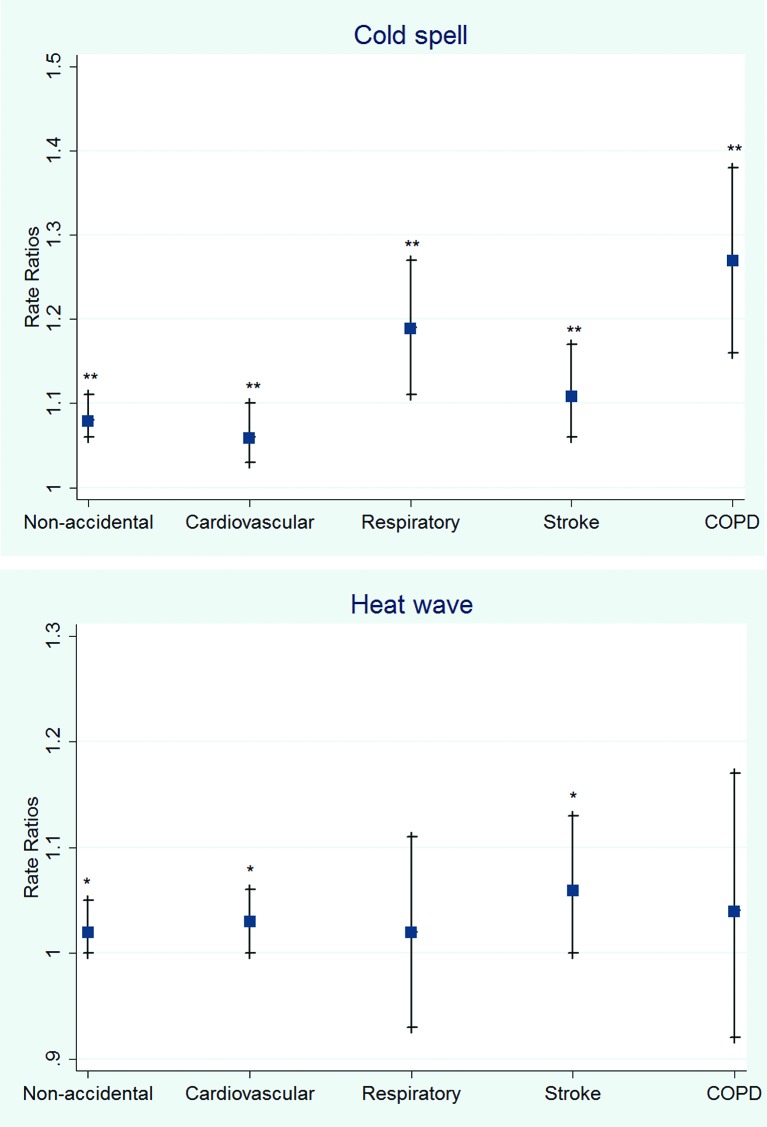

The Poisson regression models showed that cold spells significantly increased the risk of deaths due to non-accidental mortality (RR 1.08, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.11), cardiovascular disease (RR 1.06, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.10), respiratory disease (RR 1.19, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.27), stroke (RR 1.11, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.17) and COPD (RR 1.27, 95% CI 1.16 to 1.38). The risk of deaths related to heat waves increased significantly for non-accidental mortality (RR 1.02, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.05), cardiovascular disease (RR 1.03, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.06) and stroke (RR 1.06, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.13). Deaths from respiratory disease (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.11) and COPD (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.17) also increased during the heat waves, but the impact was not statistically significant (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Rate ratios of cold spells and heat waves on daily number of deaths in Jinan, China. Rate ratios were calculated as ratios between the number of deaths during the cold spell/heat wave days and the number during the non-cold spell/non-heat wave days. *p <0.05, **p <0.01. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Cold spells significantly increased the risk of non-accidental mortality in both genders and age groups. Heat waves increased the risk in both genders. The risk of mortality in elderly people (over 65 years) increased statistically during heat waves, but not in the younger (≤64 years) age group (Table 4).

Table 4.

Gender and age specific risk of cold spells and heat waves on total non-accidental mortality in Jinan, China

| Exposure period | RR of cold spell (95% CI) |

RR of heat wave (95% CI) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1.09 (1.06 to 1.12)** | 1.03 (1.00 to 1.07)* |

| Female | 1.12 (1.08 to 1.16)** | 1.04 (1.00 to 1.07)* |

| Age (years) | ||

| 0–64 | 1.14 (1.09 to 1.19)** | 0.97 (0.93 to 1.02) |

| ≥65 | 1.08 (1.06 to 1.11)** | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.06)** |

*p<0.05, **p<0.01

Discussion

In this study, we have examined the effects of temperature extremes, including both cold spells and heat waves, on deaths in Jinan, China from 2011 to 2014. Our results indicate both extreme cold and heat waves could increase the risk of deaths in the study area. The vulnerability of the population to temperature extremes varies depending on age and gender.

For heat waves, an increased risk of deaths has been found for non-accidental, cardiovascular and stroke mortality. Our results have confirmed those from our previous study on heat waves and mortality. Moreover, those subjects above 65 years of age were observed to be more vulnerable during heat wave exposure. This finding is consistent with previous studies in Europe, Latin America and China.15 18 19 However, our estimates of increased mortality risk during heat waves are not as high as Ma’s study which was conducted in 66 communities in China.15 There are several possible reasons for this. First of all, techniques used to estimate increased risks for mortality varied across the studies. We applied a time-series adjusted Poisson regression rather than a time-series regression model combined distributed lag non-linear model (DLNM) used in Ma’s studies. The DLNM can estimate the cumulative effect in the existence of delayed contributions. But they used cumulative excess mortality risk of heat waves only at 0–1 lag days. Instead, we have examined the risk at various lag values. Moreover, Jinan often has particularly very hot summer days with unique geographic and environmental situations. Local residents may have developed adaptive behaviours to the heat, which could contribute to a reduced mortality risk.

The underlying factors of vulnerability are both social and medical. An ageing society means a higher prevalence of chronic and degenerative diseases. For the elderly, their physiological responses to the environment decreased with ageing and poor medication interacts with thermoregulation. China is facing the challenges of a rapid growth in the number of old people, and has the largest elderly population in the world. In Jinan, the number of people above 65 has been reported to be 750 000, which accounted for 12.31% of the population by the end of 2014. Given the large ageing population in Jinan, this study has public health implications for improving the public health service for ageing people in a changing climate.

Cold spells have significantly increased the risk of death compared with non-cold spell periods. This finding is in agreement with previous studies in Europe and Russia. In our study, the significant effects of cold spells were identified by the increase in the number of deaths due to non-accidental mortality, cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, stroke and COPD. The cold spell effect for cause-specific mortality varies in different regions. In a study of the Eurowinter Group, the cold spell effect was found for deaths due to respiratory causes but not for cardiovascular disease and ischaemic heart disease in warmer countries.20 In China, a 36-communities study found a more pronounced cold spell effect for respiratory mortality than for cardiovascular or cerebrovascular mortality.6 Stronger associations with cardiovascular disease compared with respiratory mortality were observed in the USA and Ireland.21 22 A recent meta-analysis showed cold spells were associated with increased mortality from all non-accidental causes, especially from cardiovascular and respiratory diseases.23 Our findings could be important for public health interventions in people with underlying chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, stroke and COPD by addressing behavioural risk factors in the winter season. Besides, there is a need for specific cold spell prevention plans for the public health authorities in Jinan, which would enable mortality attributable to low temperatures to be reduced.

One interesting finding from our study is the higher vulnerability to cold among the younger age group (<65 years) compared with the elderly (over 65 years). This finding seems to differ from those of previous studies that reported older people (over 65 years or 75 years) might be the most vulnerable.24 25 It indicates that population vulnerability to cold spells could vary depending on various study settings. Similar evidence was found in Ireland that young adults (18–64 years) with respiratory disease might be the most susceptible to cold related deaths.22 A study conducted in the Czech Republic reported cold spells had the greatest effect on young adult men (25–59 years) with cardiovascular disease.26 Occupational exposure might contribute to this finding, given that older people tend to stay indoors during cold days, and thus avoid direct exposure to low ambient temperatures. In addition, adaptive behaviours might be more likely to be undertaken by older residents in Jinan because of very cold winters historically. More research is required to identify the underlying reasons for the population vulnerability to cold in Jinan. Climate change, particularly global warming, has led to attention being particularly focused on the effect of heat and heat waves on human health. Cold spells, however, have had less attention from researchers. Studies have reported significant increases in mortality during cold spells in different subpopulations in Bangladesh, the Netherlands, the Czech Republic and Russia (Moscow). Gasparrini et al found that the attributable deaths were more pronounced for low than for high temperatures in a multicountry study.27 Additionally, a study using data from 15 European cities demonstrated that cold-related mortality is an important public health problem across Europe. It should not be underestimated by public health authorities because of the recent focus on heatwave episodes.28 In the UK, excess winter mortality has enjoyed prominent status in many aspects of public policy and research.29 Our finding has demonstrated that cold spells are as important as heat waves in Jinan.

Given that climate change will bring more temperature extremes including cold spells, our study has public health implications for policy and practice for government at all levels, as well as community capacity building. Specifically, the findings of our study can assist in the development of adaptive strategies and policies with a focus on identified vulnerable populations in the community, including the refinement of current public health emergency response plans to focus on both very hot and very cold temperatures. It could also inform the development of clinical guidelines and training programmes to doctors in order to improve health services during extreme temperature events, with a better understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms in mediating the health effects of heat and cold. Building community resilience could also be supported with better preparation to reduce the number of temperature-related deaths.

Some limitations of the study should be acknowledged. First, the data were only from one city, and generalisation of the results to other regions should be viewed with caution. However, we also recognise the importance of local studies to assist decision making for local communities. The lessons learnt from Jinan could provide more evidence for other regions with similar conditions in China. Second, air pollution data, , for example ozone, was not available over the study period. In previous studies, the estimated temperature effects were slightly reduced or not changed when air pollution including ozone was controlled for.10 25Some studies also found a potential interaction between temperature and ozone.30 However, there are also studies suggesting that the effects of air pollution on mortality could be much smaller than the temperature effects.31 32 Thus, the relationship that we detected between mortality and extremes of temperature might not be substantially confounded by the effects of air pollution. Third, ecological bias based on population data is inevitable. More studies could be conducted when individual level data, for example, more detailed age groups, living conditions, health status and socioeconomic status of deceased people, are available to be able to detect more detailed distribution of population vulnerability.

Conclusions

Our results provide more evidence regarding the health impacts of extreme temperatures including cold spells and heat waves. Our study suggests that the effect of cold on health should not be underestimated in Jinan city. The increasing number and intensity of temperature extremes (cold spells and heat waves) will have a deep impact on health. From the point of view of prevention, multidisciplinary cooperation aimed at avoiding or diminishing the effects of temperature extremes need to be carried out.

bmjopen-2016-014741supp001.doc (79KB, doc)

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JH contributed to the study design, data analysis and drafting of the manuscript. SQL and JZ contributed to data collection, analysis, interpretation of data and wiring the draft. LZ and QLF collected and managed the data sets and contributed to data analysis, manuscript writing and interpretation to policy. YZ and JZ contributed to study design, data analysis and interpretation of results, as well as manuscript writing and dissemination of findings to stakeholders.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Jinan Municipal Centre for Disease Control and Prevention.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Stocker T. Climate change 2013: the physical science basis: working group I contribution to the fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 1535, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Katsouyanni KTD. The 1987 Athens heat wave. Lancet 1998;8610:573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barriopedro D, Fischer EM, Luterbacher J, et al. . The hot summer of 2010: redrawing the temperature record map of Europe. Science 2011;332:220–4. 10.1126/science.1201224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Luterbacher J, Dietrich D, Xoplaki E, et al. . European seasonal and annual temperature variability, trends, and extremes since 1500. Science 2004;303:1499–503. 10.1126/science.1093877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lowe R, Ballester J, Creswick J, et al. . Evaluating the performance of a climate-driven mortality model during heat waves and cold spells in Europe. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2015;12:1279–94. 10.3390/ijerph120201279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhou MG, Wang LJ, Liu T, et al. . Health impact of the 2008 cold spell on mortality in subtropical China: the climate and health impact national assessment study (CHINAs). Environ Health 2014;13:60. 10.1186/1476-069X-13-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gu S, Huang C, Bai L, et al. . Heat-related illness in China, summer of 2013. Int J Biometeorol 2016;60:131–7. 10.1007/s00484-015-1011-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guo Y, Gasparrini A, Armstrong B, et al. . Global variation in the effects of ambient temperature on mortality: a systematic evaluation. Epidemiology 2014;25:781–9. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Huang C, Barnett AG, Wang X, et al. . The impact of temperature on years of life lost in Brisbane, Australia. Nat Clim Chang 2012;2:265–70. 10.1038/nclimate1369 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Anderson BG, Bell ML. Weather-related mortality: how heat, cold, and heat waves affect mortality in the United States. Epidemiology 2009;20:205–13. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318190ee08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baccini M, Biggeri A, Accetta G, et al. . Heat effects on mortality in 15 European cities. Epidemiology 2008;19:711–9. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318176bfcd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de’ Donato FK, Leone M, Scortichini M, et al. . Changes in the effect of heat on mortality in the last 20 years in nine European cities. Results from the PHASE project. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2015;12:15567–83. 10.3390/ijerph121215006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huang C, Chu C, Wang X, et al. . Unusually cold and dry winters increase mortality in Australia. Environ Res 2015;136:1–7. 10.1016/j.envres.2014.08.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gao J, Sun Y, Liu Q, et al. . Impact of extreme high temperature on mortality and regional level definition of heat wave: a multi-city study in China. Sci Total Environ 2015;505:535–44. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ma W, Zeng W, Zhou M, et al. . The short-term effect of heat waves on mortality and its modifiers in China: an analysis from 66 communities. Environ Int 2015;75:103–9. 10.1016/j.envint.2014.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang Y, Bi P, Sun Y, et al. . Projected years lost due to disabilities (YLDs) for bacillary dysentery related to increased temperature in temperate and subtropical cities of China. J Environ Monit 2012;14:510–6. 10.1039/C1EM10391A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang J, Liu S, Han J, et al. . Impact of heat waves on nonaccidental deaths in Jinan, China, and associated risk factors. Int J Biometeorol 2016;60:1367–75. 10.1007/s00484-015-1130-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Åström DO, Forsberg B, Rocklöv J. Heat wave impact on morbidity and mortality in the elderly population: a review of recent studies. Maturitas 2011;69:99–105. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zeng W, Lao X, Rutherford S, et al. . The effect of heat waves on mortality and effect modifiers in four communities of Guangdong Province, China. Sci Total Environ 2014;482-483:214–21. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.02.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. The Eurowinter Group. Cold exposure and winter mortality from ischaemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, respiratory disease, and all causes in warm and cold regions of Europe. The Eurowinter Group. Lancet 1997;349:1341–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Braga AL, Zanobetti A, Schwartz J. The effect of weather on respiratory and cardiovascular deaths in 12 U.S. cities. Environ Health Perspect 2002;110:859–63. 10.1289/ehp.02110859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zeka A, Browne S, McAvoy H, et al. . The association of cold weather and all-cause and cause-specific mortality in the island of Ireland between 1984 and 2007. Environ Health 2014;13:104. 10.1186/1476-069X-13-104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ryti NR, Guo Y, Jaakkola JJ. Global association of cold spells and adverse health effects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Health Perspect 2016;124:12–22. 10.1289/ehp.1408104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Iñiguez C, Ballester F, Ferrandiz J, et al. ; TEMPRO-EMECAS. Relation between temperature and mortality in thirteen Spanish cities. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2010;7:3196–210. 10.3390/ijerph7083196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xie H, Yao Z, Zhang Y, et al. . Short-term effects of the 2008 cold spell on mortality in three subtropical cities in Guangdong Province, China. Environ Health Perspect 2013;121:210–6. 10.1289/ehp.1104541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kysely J, Pokorna L, Kyncl J, et al. . Excess cardiovascular mortality associated with cold spells in the Czech Republic. BMC Public Health 2009;9:19 10.1186/1471-2458-9-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gasparrini A, Guo Y, Hashizume M, et al. . Mortality risk attributable to high and low ambient temperature: a multicountry observational study. Lancet 2015;386:369–75. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62114-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Analitis A, Katsouyanni K, Biggeri A, et al. . Effects of cold weather on mortality: results from 15 European cities within the PHEWE project. Am J Epidemiol 2008;168:1397–408. 10.1093/aje/kwn266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liddell C, Morris C, Thomson H, et al. . Excess winter deaths in 30 European countries 1980–2013: a critical review of methods. J Public Health 2015:fdv184. 10.1093/pubmed/fdv184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ren C, Williams GM, Morawska L, et al. . Ozone modifies associations between temperature and cardiovascular mortality: analysis of the NMMAPS data. Occup Environ Med 2008;65:255–60. 10.1136/oem.2007.033878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Buckley JP, Richardson DB. Commentary: does air pollution confound studies of temperature? Epidemiol 2014;25:242–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ren C, O’Neill MS, Park SK, et al. . Ambient temperature, air pollution, and heart rate variability in an aging population. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173:1013–21. 10.1093/aje/kwq477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014741supp001.doc (79KB, doc)