Abstract

Background

Mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to the pathogenesis of acute kidney injury (AKI). The urinary mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) level was previously shown to predict renal function recovery in AKI following cardiac surgery. Herein, we determine whether urinary mtDNA is a marker of severity and predictor of recovery in AKI due to other etiologies.

Methods

We recruited 107 AKI patients. The urinary mtDNA level was measured, the severity of AKI was quantified, and patients were followed for 90 days.

Results

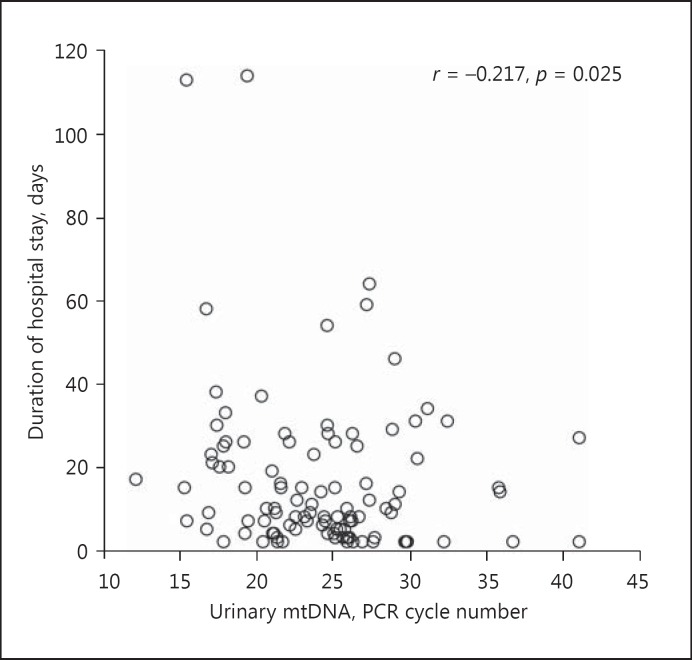

The urinary mtDNA level had modest but statistically significant correlations with the peak serum creatinine level (Spearman's r = −0.248, p = 0.010) and the duration of hospital stay (r = −0.217, p = 0.025). Patients who required temporary dialysis also tended to have higher urinary mtDNA levels than those without dialysis (22.6 ± 4.5 vs. 24.9 ± 5.7 cycles, p = 0.06). There was no definite relation between the urinary mtDNA level and renal function recovery.

Conclusion

The urinary mtDNA level is a marker of AKI severity, as reflected by its significant correlation with the peak serum creatinine level, duration of hospital stay, and probably the need for temporary dialysis. Our result suggests that urinary mtDNA has the potential to serve as a biomarker of AKI.

Keywords: Acute kidney injury, Biomarker, Proteinuria

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a serious and common diagnosis in acute hospital admissions. It is associated with markedly increased in-hospital and long-term mortality, especially in patients admitted to the intensive care unit [1, 2]. Those who survived an AKI episode are at a high risk of progression to chronic kidney disease (CKD), and up to 10% may develop end-stage renal disease [3]. Although AKI is conventionally diagnosed by an increase in the serum creatinine concentration or a reduction in the urine volume, novel biomarkers are much needed for the determination of disease severity as well as prediction of renal function recovery.

Recently, the biological relevance of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is increasingly being recognized [4]. Mitochondrial integrity is a key contributor to AKI pathophysiology. For example, early pathological changes of mitochondria, such as a reduction in abundance, organelle swelling, and fragmentation, are observed in the renal tubular epithelium in AKI of different etiologies [5, 6]. The damaged mitochondria induce and propagate renal injury by generating reactive oxygen species as well as releasing mtDNA, which could activate the innate immune pathways via the toll-like receptor-9 pathway [7, 8]. Moreover, since mitochondrial dysfunction may result in ATP depletion, it may play a role in the recovery from AKI [9].

Despite the accumulating experimental evidence on the relevance of mitochondrial dysfunction in AKI initiation, progression, and recovery, human data are limited. Urinary mtDNA is reported to predict renal function recovery in AKI following cardiac surgery [10]. In this study, we determine whether urinary mtDNA is a marker of severity and predictor of recovery in AKI due to other etiologies.

Patients and Methods

Patient Selection

This is a prospective observational study. We recruited 107 patients admitted to our hospital with AKI, which was defined according to Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN) criteria [11]. Patients were classified into 2 groups based on the baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), as determined by the abbreviated Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation [12]: patients with a baseline eGFR 15–45 mL/min/1.73 m2 were classified as the acute-on-chronic renal failure (AOCRF) group, while patients with baseline eGFR >45 mL/min/1.73 m2 were classified as the pure-AKI group. Patients with complete anuria were excluded. The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK). All study procedures were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Collection

After written informed consent had been obtained, background clinical information and the presence of other comorbid conditions were recorded. Renal biopsy results (if performed) and patient outcomes including renal replacement therapy, in-hospital mortality, and duration of stay were also reviewed. A whole-stream early-morning urine sample was collected. If the patient required urinary catheterization, 200 mL of bag urine was used instead of early-morning urine sample.

Quantification of Urinary mtDNA

All urine specimens were processed immediately after collection according to methods described previously [13]. Briefly, protease inhibitors were added, and then samples were centrifuged at 1,000 g to remove cells and cellular debris. Urinary supernatant specimens were stored at −80°C until analysis.

Urinary mtDNA was prepared using the QIAamp DNA Blood Midi Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) standard curves were created. Since urine supernatant was directly used as the template and there is no intrinsic housekeeping gene for comparison, the number of PCR cycles at which mtDNA could be detected, i.e., threshold cycle (CT), was reported. Samples that produced no PCR products after 40 cycles were considered undetectable, and the CT number was set to 41 for statistical computation [14].

Study Outcomes

All patients were followed for 90 days. Their clinical management was decided by individual physicians and was not affected by the study. Complete recovery was defined as serum creatinine levels at 90 days lower than 110% of the baseline; partial recovery was defined as serum creatinine levels at 90 days >110% of the baseline but <90% of the peak serum creatinine; no recovery is defined as serum creatinine levels at 90 days that remained >90% of the peak serum creatinine.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by SPSS for Mac OS software version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data were expressed as mean ± SD unless otherwise specified. The urinary mtDNA level was compared between the groups by the Student t test or one way analysis of variance (ANOVA), as appropriate. Correlations between parameters were tested by the Spearman rank correlation coefficient. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All probabilities were two-tailed.

Results

We enrolled 107 patients. Out of these patients, 62 had a clinical diagnosis of acute tubular necrosis (ATN) without kidney biopsy, 8 had biopsy-confirmed ATN, 12 had presumed ATN with no obvious pathological change in kidney biopsy, and 25 had kidney biopsy that showed acute interstitial nephritis. Their baseline clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. As expected, the AOCRF group was older and had higher baseline serum creatinine levels than the pure-AKI group. Out of the 107 patients, 27 (25.2%) required temporary dialysis support. Urine mtDNA was detectable in 104 patients; the mean urinary mtDNA level was 24.3 ± 5.5 PCR cycles.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical and demographic data

| Pure AKI | AOCRF | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 59 | 48 | |

| Sex (M:F) | 34:25 | 24:24 | 0.4 |

| Age, years | 53.2±17.1 | 68.7±10.7 | <0.0001 |

| Baseline serum creatinine, μmol/L | 91.1±19.3 | 243.6±132.9 | <0.0001 |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | 0.09 | ||

| Clinical ATN, no biopsy | 28 (47.5) | 34 (70.8) | |

| Biopsy-confirmed ATN | 6 (10.2) | 2 (4.2) | |

| Biopsy showed no pathology | 9 (15.3) | 3 (6.3) | |

| Acute interstitial nephritis | 16 (27.1) | 9 (18.8) |

AKI, acute kidney injury; AOCRF, acute-on-chronic renal failure; ATN, acute tubular necrosis.

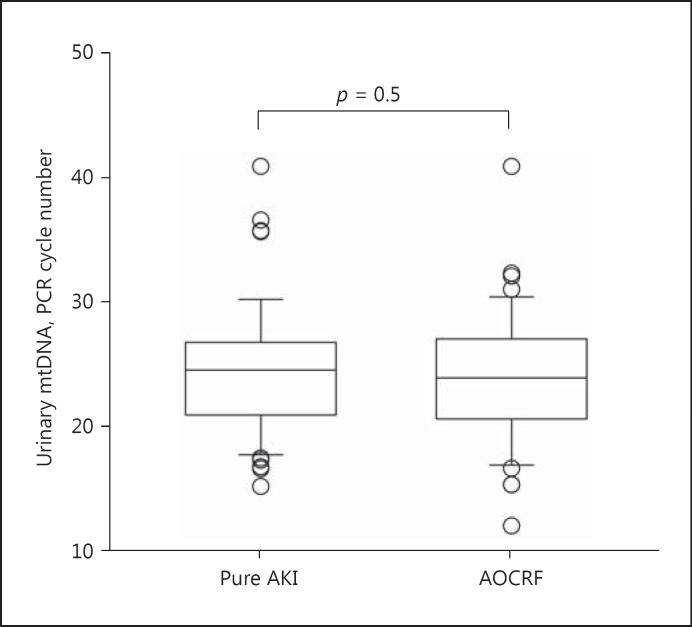

Relation with the Type of AKI

There was no statistically significant difference in the urinary mtDNA level between the pure AKI and AOCRF groups (24.6 ± 5.6 vs. 24.0 ± 5.4 cycles, p = 0.5) (Fig. 1). The urinary mtDNA levels of patients with clinical ATN without kidney biopsy, biopsy-confirmed ATN, presumed ATN with no pathological change in kidney biopsy, and acute interstitial nephritis were 23.1 ± 5.1, 25.8 ± 4.7, 26.1 ± 5.9, and 25.9 ± 5.9 cycles, respectively (one-way ANOVA, p = 0.07).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of urinary mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) levels between patients with pure acute kidney injury (AKI) and those with acute-on-chronic renal failure (AOCRF). Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) levels are expressed as the number of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) cycles; a lower cycle number indicates a higher level of mtDNA. Box and whisker plots with boxes indicating the median, 25th, and 75th percentiles, and whiskers indicating the 5th and 95th percentiles.

Relation with Severity

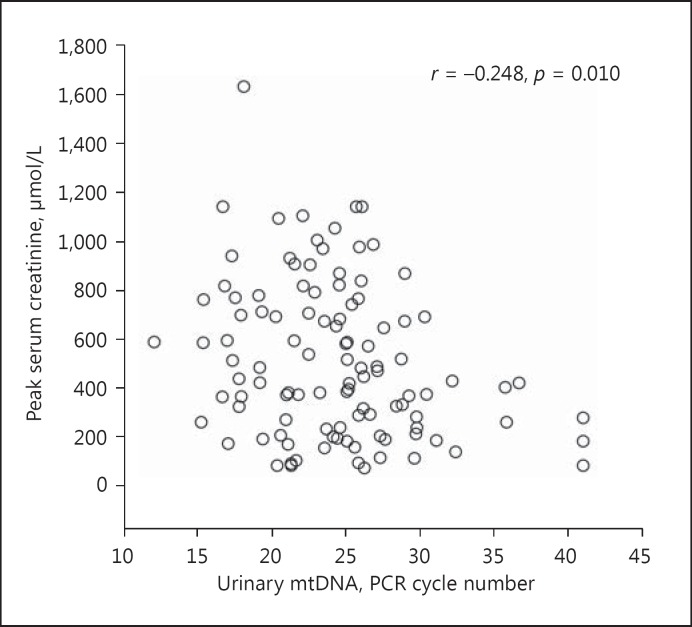

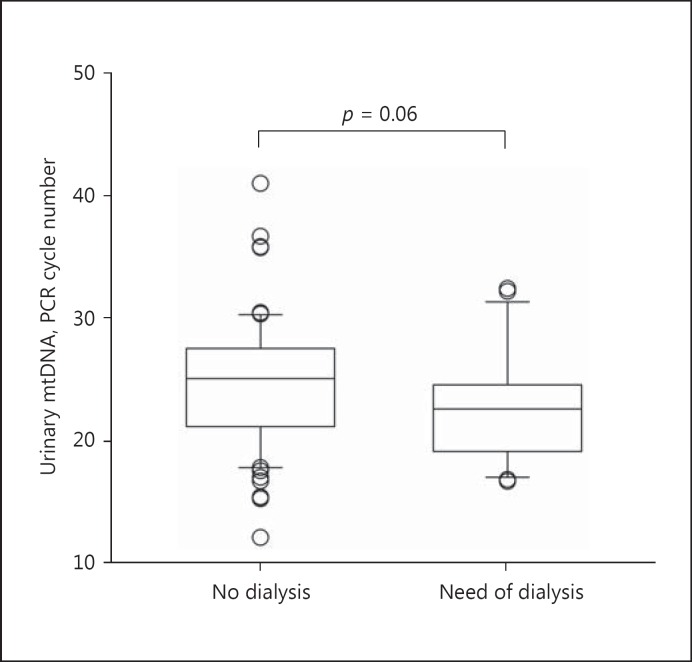

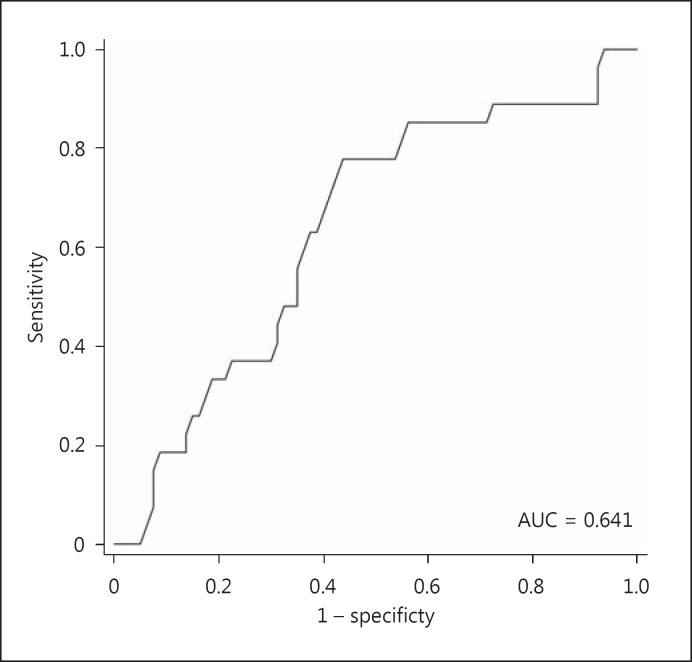

The urinary mtDNA level appears to correlate with the severity of AKI. Specifically, the urinary mtDNA level had a modest but significant correlation with the peak serum creatinine level (Spearman's r = −0.248, p = 0.010) (Fig. 2). Patients who required temporary dialysis support tended to have a higher urinary mtDNA level than those who did not require dialysis (22.6 ± 4.5 vs. 24.9 ± 5.7 cycles, p = 0.06) (Fig. 3), though the difference did not reach statistical significance. The receiver-operating characteristic curve was constructed to evaluate the ability of the urinary mtDNA level in predicting the need of temporary dialysis (Fig. 4). At the cut off of 25.5 PCR cycles, the urinary mtDNA level had a sensitivity of 81.5% and a specificity of 55.0% to predict the need of temporary dialysis. The urinary mtDNA level also correlated with the duration of hospital stay (r = −0.217, p = 0.025) (Fig. 5) and duration of temporary dialysis support (r = −0.306, p = 0.12), although the latter did not reach statistical significance.

Fig. 2.

Relation between the urinary mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) level and peak serum creatinine. mtDNA levels are expressed as the number of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) cycles. A lower cycle number indicates a higher level of mtDNA. Data are analyzed by the Spearman rank correlation coefficient.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the urinary mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) levels between patients with and without the need of temporary dialysis. mtDNA levels are expressed as the number of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) cycles. A lower cycle number indicates a higher level of mtDNA. Box and whisker plots with boxes indicating the median, 25th, and 75th percentiles, and whiskers indicating the 5th and 95th percentiles.

Fig. 4.

Receiver-operating characteristic curve of the urinary mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) level for the prediction of the need of temporary dialysis. AUC, area under the curve.

Fig. 5.

Relation between the urinary mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) level and duration of hospitalization. mtDNA levels are expressed as the number of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) cycles. A lower cycle number indicates a higher level of mtDNA. Data are analyzed by the Spearman rank correlation coefficient.

Relation with Recovery

We further test whether the urinary mtDNA level predicts renal function recovery. After 90 days of follow-up, 41 patients (38.3%) had complete recovery, 37 (34.6%) had partial recovery, and 17 (15.9%) had no recovery. Recovery could not be ascertained in 12 patients because they died within 90 days without obvious renal function recovery. The mean urinary mtDNA CT of the completely, partially recovered, and unrecovered group was 23.2 ± 5.0, 24.9 ± 5.4, and 24.7 ± 5.3, respectively (one-way ANOVA, p = 0.5). There was also no significant difference in the urinary mtDNA level between survivors and those who died with renal failure (24.5 ± 5.3 vs. 23.0 ± 7.2 cycles, p = 0.3).

Discussion

In this study, we found that the urinary mtDNA level increases with the severity of AKI, as reflected by its significant correlation with the peak serum creatinine level, duration of hospital stay, and the need for temporary dialysis support, although the last association fell short of statistical significance.

Despite the growing evidence from animal studies showing the key pathophysiological role of mitochondrial dysfunction in AKI initiation and recovery, studies evaluating the potential of urinary mtDNA as a novel AKI biomarker in human have been limited. Whitaker et al. [10] examined urinary mtDNA as a biomarker of renal injury and function after cardiac surgery, but they did not find any significant difference in urinary mtDNA level between groups of different AKI severity. The apparently contradicting observation may be attributed to the difference in clinical settings: Whitaker et al specifically recruited patients with AKI after cardiac surgery [10], while we recruited AKI patients with various etiologies. Although we did not observe any difference in urinary mtDNA level between AKI of different etiologies, the sample size of each diagnosis subgroup was small and type 2 statistical error is possible.

The exact mechanism behind the association between urinary mtDNA level and AKI severity is not entirely understood. Growing evidence shows that mitochondria in renal tubular cells are damaged in AKI, resulting in the release of injurious contents such as mtDNA [5, 6, 7, 8]. In turn, mtDNA binds to and activate toll-like receptor-9, which activates downstream innate immune cascade and further propagates renal injury [7, 8, 15].

In the study by Whitaker et al. [10], there was a significant association between the urinary mtDNA level and renal function recovery. Similarly, we observed a higher urinary mtDNA level among subjects who died or did not recover than those who had partial or complete recovery, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. Although these 2 studies used different end-point definitions of recovery, the available evidence does suggest that the urinary mtDNA level is a prognostic indicator of renal functional recovery. Since the sample sizes in both studies were small, further validation study would be necessary to confirm the role of urinary mtDNA level as a prognostic indicator. Since mitochondrial disruption results in energy depletion and incomplete renal repair [10, 16], the hypothesis that the urinary mtDNA level predicts AKI recovery has a sound theoretical basis.

We did not find any difference in the urinary mtDNA level between the pure AKI and AOCRF groups. It is uncertain whether the insignificant finding can be attributed to the small sample size of our study and the arbitrary cutoff chosen in defining pre-existing CKD (i.e., eGFR 15–45 mL/min/1.73 m2, equivalent to Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes guideline CKD stages 3b and 4 [17]). To the best of our knowledge, the alteration of the urinary mtDNA level in CKD has not been reported.

There are several limitations of our study. First, our sample size was small, and the negative findings may represent type 2 statistical error. Second, subjects and AKI severity was defined by the peak serum creatinine level, which could be influenced by the age, gender, body built, diet, and probably baseline serum creatinine. Some patients may have profound oliguria but only a modest increase in serum creatinine because of poor dietary intake and muscle wasting. Furthermore, the urinary mtDNA level was reported in terms of the PCR cycle number. Since urine was directly used as the PCR template and there was no intrinsic housekeeping gene for comparison, it was impossible to compute the mtDNA copy number. In this study, we quantified mtDNA from the entire urinary sample and did not adjust for the concentration-dilution factor. Previous studies normalized the urinary mtDNA level to urine creatinine concentration in order to adjust for the concentration/dilution factor [18], but we do not consider this method reliable before urinary creatinine excretion is, by definition, defective in AKI. To the best of our knowledge, there is no practical means to adjust for the urinary mtDNA level, but the total amount of mtDNA in a timed urine sample may be sound theoretically.

In this study, we did not include a group of healthy subjects as a control. A subgroup of the recruited patients had a normal renal biopsy (Table 1) because they had mild ATN with no overt renal tubular cell death. It would be interesting to explore whether their urinary mtDNA levels are elevated as compared to healthy controls.

In summary, we found that the urinary mtDNA level reflects the severity of AKI in terms of peak serum creatinine level, duration of hospitalization, need of temporary dialysis, and probably duration of dialysis required. Unlike a previous report [10], urinary mtDNA level did not predict renal function recovery in our study. Our observations also suggest that therapeutic agents that target at mitochondrial damage and regeneration may be valuable for the prevention or treatment of AKI.

Conflict of Interest Statement

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported in part by the Chinese University of Hong Kong research account 6901031.

References

- 1.Rewa O, Bagshaw SM. Acute kidney injury-epidemiology, outcomes and economics. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014;10:193–207. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2013.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siew ED, Davenport A. The growth of acute kidney injury: a rising tide or just closer attention to detail? Kidney Int. 2015;87:46–61. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cerdá J, Liu KD, Cruz DN, Jaber BL, Koyner JL, Heung M, Okusa MD, Faubel S. Promoting kidney function recovery in patients with AKI requiring RRT. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:1859–1867. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01170215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Che R, Yuan Y, Huang S, Zhang A. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathophysiology of renal diseases. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2014;306:F367–F378. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00571.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tran M, Tam D, Bardia A, Bhasin M, Rowe GC, Kher A, Zsengeller ZK, Akhavan-Sharif MR, Khankin EV, Saintgeniez M, David S, Burstein D, Karumanchi SA, Stillman IE, Arany Z, Parikh SM. PGC-1α promotes recovery after acute kidney injury during systemic inflammation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4003–4014. doi: 10.1172/JCI58662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brooks C, Wei Q, Cho SG, Dong Z. Regulation of mitochondrial dynamics in acute kidney injury in cell culture and rodent models. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1275–1285. doi: 10.1172/JCI37829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Q, Raoof M, Chen Y, Sumi Y, Sursal T, Junger W, Brohi K, Itagaki K, Hauser CJ. Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature. 2010;464:104–107. doi: 10.1038/nature08780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emma F, Montini G, Parikh SM, Salviati L. Mitochondrial dysfunction in inherited renal disease and acute kidney injury. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12:267–280. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2015.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonventre JV, Yang L. Cellular pathophysiology of ischemic acute kidney injury. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4210–4221. doi: 10.1172/JCI45161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whitaker RM, Stallons LJ, Kneff JE, Alge JL, Harmon JL, Rahn JJ, Arthur JM, Beeson CC, Chan SL, Schnellmann RG. Urinary mitochondrial DNA is a biomarker of mitochondrial disruption and renal dysfunction in acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2015;88:1336–1344. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, Levin A. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11:R31. doi: 10.1186/cc5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:461–470. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szeto CC. Urine miRNA in nephrotic syndrome. Clin Chim Acta. 2014;436:308–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Helsel DR. Less than obvious - statistical treatment of data below the detection limit. Environ Sci Technol. 1990;24:1766–1774. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collins LV, Hajizadeh S, Holme E, Jonsson IM, Tarkowski A. Endogenously oxidized mitochondrial DNA induces in vivo and in vitro inflammatory responses. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:995–1000. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0703328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Funk JA, Schnellmann RG. Persistent disruption of mitochondrial homeostasis after acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;302:F853–F864. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00035.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kidney Disease. Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group: KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3:1–150. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ralib AM, Pickering JW, Shaw GM, et al. Test characteristics of urinary biomarkers depend on quantitation method in acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:322–333. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011040325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]