Abstract

Peroxiredoxin1 (Prdx1) is an antioxidant enzyme belonging to the peroxiredoxin family of proteins. Prdx1 catalyzes the reduction of H2O2 and alkyl hydroperoxide and plays an important role in different biological processes. Prdx1 also participates in various age-related diseases and cancers. In this study, we investigated the role of Prdx1 in pronephros development during embryogenesis. Prdx1 knockdown markedly inhibited proximal tubule formation in the pronephros and significantly increased the cellular levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which impaired primary cilia formation. Additionally, treatment with ROS (H2O2) severely disrupted proximal tubule formation, whereas Prdx1 overexpression reversed the ROS-mediated inhibition in proximal tubule formation. Epistatic analysis revealed that Prdx1 has a crucial role in retinoic acid and Wnt signaling pathways during pronephrogenesis. In conclusion, Prdx1 facilitates proximal tubule formation during pronephrogenesis by regulating ROS levels.

Introduction

The kidney is an indispensable homeostatic organ that maintains fluid and salt balance in the body1. The kidney functions by filtering and excreting wastes from the body1, 2. Three main structures are formed during kidney development, namely, the pronephros, mesonephros, and metanephros3, all of which originate from the intermediate mesoderm during embryogenesis4. The pronephros, mesonephros, and metanephros are structurally and functionally distinct, except that the nephron is common to all three structures5. The nephron comprises three basic components, namely, the glomerulus, tubule, and duct, and the role of each component in excreting wastes is different. The metanephros serves as the adult kidney in mammals, whereas the mesonephros acts as the adult kidney in amphibians. On the other hand, the pronephros is critical for embryonic development6. Although the adult kidney is distinct in different vertebrates, the underlying mechanism of kidney development is similar in zebrafish, frogs, mice, and humans7.

Kidney development is a complex process involving a series of steps that initiate from the intermediate mesoderm at the neurula stage of embryogenesis3, 5. Several signaling cascades, including bone morphogenetic protein, fibroblast growth factor, notch, Wnt, and retinoic acid (RA) pathways4, are involved in pronephros development. Wnts comprise a family of signaling proteins that bind to Frizzled (Fzd) receptors. Upon activation, Fzd receptors transduce signals to proteins belonging to the Dishevelled (Dsh) family8. Dsh proteins are phosphoproteins that consist of three functional domains, namely, a DIX domain at the N-terminus, a PDZ domain, and a DEP domain at the C-terminus9. Different combinations and interactions among these three domains determine the mode of Wnt signaling, which includes canonical versus non-canonical Wnt signaling10. Evidence indicates that canonical Wnt signaling plays an important role in kidney development, and inhibition of Wnt signaling impedes pronephros development in amphibians8. By contrast, Wnt/β-catenin-independent (non-canonical Wnt) signaling is responsible for proximal tubule formation during pronephrogenesis8, 9, 11. RA signaling is also crucial for pronephros development, and its inhibition results in pronephros abnormalities12–14. Pronephros development is associated with the expression of number of different specific genes and their corresponding transcribed and translated products. Any misregulation in the expression of these genes or abnormalities in the corresponding transcription and translation can lead to developmental defects in the pronephros15.

The peroxiredoxin (Prdx) family comprises thiol-based proteins that function as antioxidants16. Prdx proteins catalyze the reduction of different peroxide substrates, and are crucial for H2O2-mediated cell signaling17. Prdx has six isoforms that are categorized into three subclasses based on the number and position of the cysteine residues, namely, the 2-Cys, atypical 2-Cys, and 1-Cys subclasses. Prdx1 through 4 belong to the 2-Cys subclass; Prdx5 belongs to the atypical 2-Cys subclass; and Prdx6 belongs to the 1-Cys subclass17, 18. Prdx1 through 6 possess conserved cysteine residues and undergo oxidation–reduction cycles18. In addition to their functions as antioxidants, Prdx proteins are also involved in various physiological processes19, 20.

Peroxiredoxin1 (Prdx1), a typical 2-Cys Prdx that contains two conserved cysteines, catalyzes the reduction of H2O2 and alkyl hydroperoxide21. During normal Prdx1 antioxidant function, the conserved N-terminal cysteine (Cys-52) residue is selectively oxidized to Cys-SOH by H2O2. Oxidized Prdx then forms an intermolecular disulfide bond with the conserved thiol group (-SH) at the C-terminus (Cys-178) of the other subunit in the head-to-tail homodimer22. During this process, thioredoxin (Trx) reduces the disulfide bond23. Prdx1 also plays a critical role in the progression of different types of cancer, and several studies have proposed therapies aimed at halting or slowing down cancer growth16, 22. In addition to its protective effects against reactive oxygen species (ROS) or oxidative stress, Prdx1 also influences downstream signaling pathways during organogenesis24.

In the present study, we demonstrate that Prdx1, an antioxidant enzyme, plays a crucial role in pronephros development. Loss of Prdx1 resulted in abnormal proximal tubule formation in the pronephros. Catalytic mutants of Prdx1 (C53S, C173S, and C53S/C173S) were unable to dimerize, thus failing to rescue the Prdx1 knockdown-induced disruption of proximal tubule formation. In addition, treatment with ROS severely disrupted proximal tubule formation, which was restored by Prdx1 overexpression. Moreover, Prdx1 modulated RA and Wnt signaling during pronephros development. In conclusion, Prdx1 is essential for proximal tubule formation during pronephrogenesis.

Results

Prdx1 knockdown arrests proximal tubule formation in the pronephros during embryogenesis

To analyze the Prdx1 expression pattern, RT-PCR and whole-mount in situ hybridization were performed on X. laevis embryos. The Prdx1 transcript was maternally expressed (stage 0), and its expression gradually increased until the tadpole stage of development (Fig. S1A). Whole-mount in situ hybridization analysis at different developmental stages (NF stage 8, 14, 16, 22 and 33) showed that prdx1 was highly and predominantly expressed in the forebrain, eye, multiciliated cells, and pronephros of developing embryos (Fig. S1B). prdx1 was also expressed in the intermediate mesoderm, which comprises the proximal compartments that develop into the proximal tubules (Fig. S1B).

To investigate the role of Prdx1 in pronephros development, we performed knockdown studies using prdx1 antisense morpholino oligonucleotides (MOs) and to verify the specificity of prdx1 MO, embryos at two-cell stage were injected with prdx1 MO and prdx1* RNA that failed to bind to the prdx1 MOs. The translation product for WT prdx1 RNA was significantly reduced by prdx1 MO but no marked reduction was observed for prdx1* RNA translated product (Fig. S2E). Hence, it is confirmed that prdx1 is the only affected transcript by prdx1 MO. prdx1 MOs were injected into both blastomeres of two-cell stage embryos, and the phenotypes of the morphant embryos were analyzed. Embryonic development of prdx1 morphants was abnormal, as evident by shorter trunks and smaller heads compared with the control MO-injected embryos (Fig. S2A). Since, MO injections at two-cell stage cause significant defects in axis formation and development of the notochord, somites and dorsal aorta in addition to the kidney, so to avoid the ambiguity that kidney defects arise directly from prdx1 knockdown rather than secondarily caused by defects in other structures, we injected prdx1 MO into a V.2.2 blastomere at 16-cell stage that is a major contributor for pronephros (Fig. S2C). Interestingly embryos exhibited similar developmental abnormalities as were observed for prdx1 MO injections at two-cell stage (Fig. S2C). These results confirmed that the Prdx1 is essential for pronephros development and knockdown of Prdx1 led to abnormalities in embryonic kidney development.

The role of Prdx1 in pronephros development was further examined using hematoxylin and eosin-stained transverse sections of control and prdx1 morphant embryos. prdx1 MO-injected embryos displayed malformed or undifferentiated internal organs that appeared to be scattered compared with control MO-injected embryos (Fig. S2D). The analysis of transverse sections showed that the pronephros was poorly developed in prdx1 MO-injected embryos compared with control MO-injected embryos.

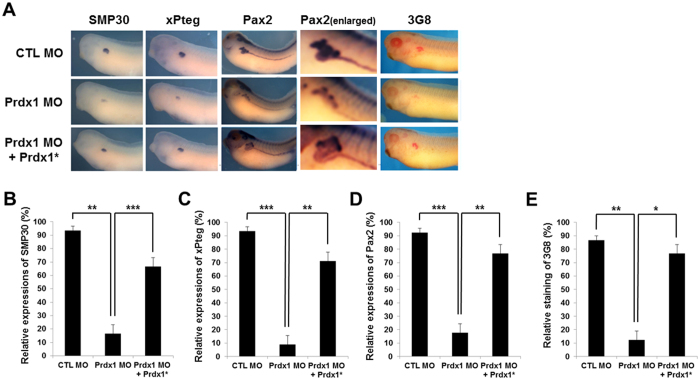

Next, we analyzed the Prdx1 morphant embryos using the proximal tubule-specific markers smp30 25, xPteg 26, and pax2 27 for whole-mount in situ hybridization. The levels of smp30, xPteg, and pax2 were significantly lower in prdx1 MO-injected embryos at the stage 33 than in control MO-injected embryos (Fig. 1A–E). As shown in Fig. 1A, the morphant phenotypes were rescued by co-injection with prdx1* RNA that failed to bind to the prdx1 MOs. Interestingly, the inhibitory effects of the prdx1 MOs were observed only in the proximal tubules (Fig. 1A–E). pax2 was widely expressed in the distal, connecting, and proximal tubules in the developing pronephros. However, decreased pax2 expression in prdx1-knockdown embryos was observed only in the proximal tubules, and not in intermediate, distal and connecting tubules (Fig. 1A,D). Similar results were obtained by immunohistochemistry using a 3G8 antibody that specifically stained the proximal tubules (Fig. 1A,E), while 4A6 antibody staining of intermediate, distal and connecting tubules of prdx1 morphants were not affected at all (Fig. S2F). The proximal tubule defects were rescued by co-injection with prdx1* RNA (Fig. 1A–E), supporting previous results that showed proximal tubule defects are due to the loss-of-function phenotype of Prdx1.

Figure 1.

Inhibition of proximal tubule formation in the pronephros by the loss of Prdx1 and its rescue by Prdx1* RNA co-injection. (A) prdx1 MOs (40 ng) were injected into both blastomeres of two-cell stage embryos. Embryos at the stage 33 were used for whole-mount in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry. Proximal tubules in the pronephros were visualized by whole-mount in situ hybridization using smp30, xPteg, and pax2 probes and by immunohistochemistry using a 3G8 antibody. Expression of the proximal tubule-specific markers smp30 (B), xPteg (C), and pax2 (D) in prdx1 MO-injected embryos compared with the controls. Co-injection with prdx1* RNA rescued the decreased expression. The immunohistochemistry for 3G8 patterns were similar with whole-mount in situ hybridization (E). prdx1 morphants exihibited inhibition of proximal tubule formation only while intermediate, distal and connecting tubules were not affected by loss of prdx1.

Conserved cysteine residues in Prdx1 that are responsible for its function as an antioxidant are essential for pronephrogenesis

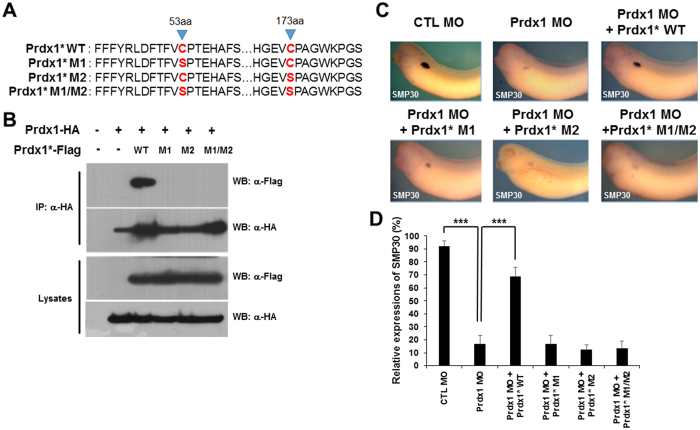

Prdx1, which is well known for its antioxidant properties in vertebrates, undergoes oxidative and reductive reactions within cells28. The function of Prdx1 as an antioxidant depends on its two conserved cysteine residues, namely, Cys-53 and Cys-173. Alterations in these conserved cysteine residues result in abnormalities. To determine the roles of these conserved cysteine residues in pronephros development during embryogenesis, we generated three Prdx1 mutants by changing the peroxidatic and resolving cysteine residues (Cys-53 and Cys-173, respectively) to serine, which disrupted the antioxidant function of Prdx1 (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Conserved cysteines in Prdx1 are essential for pronephros development. (A) Three prdx1 mutants, namely, C53S (M1), C173S (M2), and C53S/C173S (M1/2), were subcloned using PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis. (B) Flag-tagged Prdx1* or HA-tagged prdx1 (200 pg) was co-injected into both blastomeres of two-cell stage embryos. Lysates from stage 12 embryos were used for immunoprecipitation. WT Prdx1 only showed in immune complex whereas mutant Prdx1 did not. (C) prdx1 MOs (40 ng) were co-injected with WT or mutant prdx1 (M1, M2 or M1/M2) into both blastomeres of two-cell stage embryos. Embryos at the stage 33 were used for whole-mount in situ hybridization, and proximal tubules in the pronephros were visualized with a smp30 probe. Inhibited proximal tubule formation in prdx1 morphants was rescued by WT prdx1 but not with mutant prdx1* RNAs. (D) Graphical demonstration of smp30 expression in embryos co-injected with WT or mutant prdx1 (M1, M2 or M1/M2) and prdx1 MOs compared with the controls.

To determine whether these Prdx1 mutants can bind to each other in embryos, we co-injected a Prdx1*-Flag-tagged mutant (WT, M1, M2, or M1/M2) with WT Prdx1-HA mRNA and performed immunoprecipitation using an anti-HA antibody. Flag-tagged WT Prdx1 (Prdx1*-Flag WT) associated with HA immunocomplexes (Figs 2B and S4). However, immunoreactive signals corresponding to the Flag-tagged Prdx1* mutants (M1, M2, and M1/M2) were not detected (Fig. 2B), indicating that the conserved cysteine residues in Prdx1 have roles similar to those in X. laevis embryos.

The roles of the conserved cysteine residues in pronephrogenesis were further analyzed by microinjecting the prdx1 MOs with mutant prdx1* RNA (WT, M1, M2, or M1/M2). Embryos were analyzed by whole-mount in situ hybridization using a probe against the proximal tubule marker smp30. The prdx1 MO-mediated inhibition of proximal tubule formation was rescued by injection with WT prdx1, but not with mutant prdx1* RNAs (Fig. 2C,D). These results clearly demonstrate that the peroxidase function of Prdx1 is critical for pronephros development.

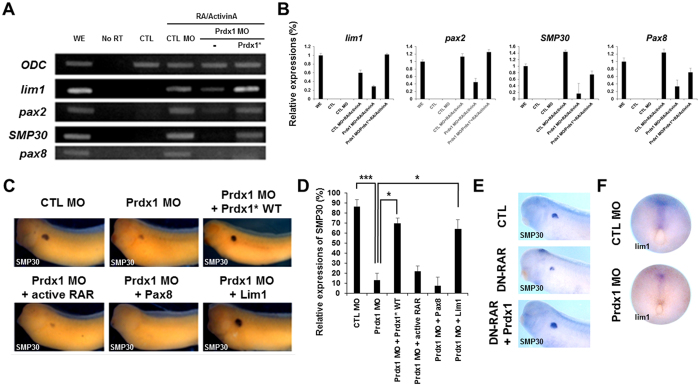

Prdx1 functions downstream of RA signaling during pronephrogenesis

RA signaling is essential for pronephros development29. The treatment of X. laevis gastrulae with trans-RA and activin can induce the differentiation of pluripotent ectodermal cells to the pronephros29. Moreover, pronephros development is impaired when RA signaling is inhibited29. To investigate the role of Prdx1 as a mediator of RA signaling during pronephros development, we performed an in vitro kidney induction assay. Animal cap cells (stem cell-like) were removed from the injected embryos at the stage 8.5 and sequentially treated with activin A (10 ng/mL) and all-trans RA (10−4 M) as previously described29. Animal cap cells were then induced to form the pronephric mesoderm, pronephric tubules, and glomus29. Next, we examined the levels of several pronephros markers during pronephros development by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) and real time PCR. The levels of lim1, pax2, smp30, and pax8 were significantly lower in the prdx1 MO-injected embryos than in the control MO-injected embryos (Fig. 3A,B). The decreased expression of lim1, pax2,smp30 and pax8 was rescued by co-injection with prdx1* RNA (Fig. 3A,B). These results indicate that Prdx1 functions as a one of significant modulator of RA signaling for pronephrogenesis.

Figure 3.

Prdx1 functions downstream of the RA signaling pathway during proximal tubule formation in the pronephros. (A) prdx1 MOs (40 ng) were injected into both blastomeres of two-cell stage embryos. Animal caps were removed from the injected embryos at the stage 8.5 and incubated with 10 ng/mL activin A, followed by 10−4 M all-trans RA for 3 h. Animal caps were collected from embryos at the stage 33 and used for RT-PCR. RT-PCR results showed the significant reduced expression of lim1, pax2, smp30, and pax8 in prdx1 MO-injected as compared with RA/activin induced. The decreased expression of pronephros markers was rescued by prdx1* RNA. Ornithine decarboxylase (odc) was used as the loading control. A no-RT template in the absence of reverse transcriptase was used as the control. WE, whole embryo; CTL, control animal caps; CTL MO, control MO-injected animal caps. (B) RT-PCR examination of lim1, pax2, smp30 and pax8 expression was confirmed by real time PCR. Significant lower expression level was observed for pronephros markers in the prdx1 MO-injected embryos that was rescued by co-injection with prdx1* RNA except for pax8. WE, whole embryo; CTL, control animal caps; CTL MO, control MO-injected animal caps. (C) prdx1 MOs (40 ng) were co-injected with wild-type prdx1, RARα-vp16 (active rar), pax8, or lim1 (400 pg) into both blastomeres of two-cell stage embryos. Embryos at the stage 33 were used for whole-mount in situ hybridization, and proximal tubules in the pronephros were visualized with a smp30 probe. The pronephros abnormalities of prdx1 morphants were rescued by lim1 mRNA co-injection but not by the activation of active RA receptors or pax8. (D) Graphical representation of pronephros development in prdx1 MO-injected embryos and embryos co-injected with lim1, active RA receptors and pax8 compared to the control embryos (injected with control MO). Pronephros defects were significantly rescued by lim1 mRNA co-injection. (E) Embryos at two-cell stage were injected with dominant-negative retinoic acid receptor (DN-RAR) with or without prdx1. DN-RAR-inhibited pronephros development was rescued by prdx1 overexpression. (F) Expression of pronephros marker lim1 was observed at stage 12.5 in embryos injected with CTL MO and prdx1 MO. lim1 expression was dramatically reduced in Prdx1 morphants.

RT-PCR and real time PCR results were validated by conducting epistatic experiments, which restored the decreased expression of the pronephric markers upon prdx1 knockdown. prdx1 MOs were co-injected with various RNAs [WT prdx1, RARα-vp16 (constitutively active RA receptor), pax8, or lim1] into both blastomeres of two-cell stage embryos. Embryos at the stage 33 were analyzed by whole-mount in situ hybridization using a smp30 probe. The defects in the pronephros of prdx1 morphants were rescued by lim1 mRNA co-injection, but not by the activation of the active RA receptor or pax8 (Fig. 3C,D). To discern affected stages of kidney development by prdx1 activity, we showed lim1 expression at stage 12.5 embryos injected with control MO and prdx1 MO (Fig. 3F). Interestingly, lim1 expression was markedly reduced in prdx1 morphants suggesting that early retinoic acid signaling was also affected (Fig. 3F). Thus, RT-PCR results and epistatic analysis showed that Prdx1 regulates pronephrogenesis by acting as a downstream mediator of RA signaling. To prove the epistatic analysis, we injected dominant-negative retinoic acid receptor (DN-RAR) into both blastomeres of two-cell staged embryos with or without prdx1 RNA and it is clearly evident that DN-RAR-inhibited pronephros development was partially rescued by prdx1 (Fig. 3E). Hence, it is confirmed that Prdx1 acts as a mediator of RA signaling during pronephros development.

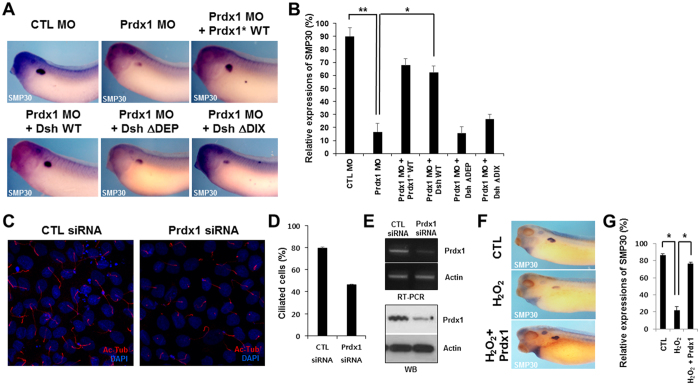

Prdx1 regulates pronephros development via the Wnt signaling pathway

To investigate whether Prdx1 regulates pronephrogenesis via the Wnt signaling pathway, we generated two Dsh deletion constructs, designated DshΔDEP and DshΔDIX. The DIX domain of Dsh is a key regulator of canonical Wnt signaling, whereas the DEP domain activates non-canonical Wnt signaling30, 31. We co-injected the prdx1 MOs and prdx1* RNA, with either Dsh WT or the Dsh deletion constructs (DshΔDEP or DshΔDIX), and then monitored pronephros development by whole-mount in situ hybridization using a smp30 probe. The prdx1 MO-induced inhibition of pronephros development was restored in embryos co-injected with Dsh WT RNA, but not with DshΔDEP or DshΔDIX RNA (Fig. 4A,B). These results indicate that Prdx1 regulates pronephrogenesis by influencing both canonical and non-canonical Wnt signaling.

Figure 4.

Prdx1 regulates pronephrogenesis via the Wnt signaling pathway by modulating ROS levels in X. laevis embryos. (A) prdx1 MOs and WT prdx1*, WT Dsh (Dsh WT), DshΔDEP, or DshΔDIX were co-injected into both blastomeres of two-cell stage embryos. Embryos at the stage 33 were used for whole-mount in situ hybridization, and proximal tubules in the pronephros were visualized with a smp30 probe. Pronephros development recovered only in embryos co-injected with WT prdx1* or Dsh WT. (B) Graphical demonstration of pronephros development in embryos co-injected with prdx1 MOs and WT prdx1*, Dsh WT, DshΔDEP, or DshΔDIX. (C) MDCK cells were transfected with either 10 nM prdx1 or control siRNAs. Primary cilia were visualized using an acetylated-tubulin (Ac-Tub) antibody. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. Numbers of cilia cells were markedly reduced in MDCK cells by prdx1 siRNA mediated knockdown of prdx1. (D) Graphical representation of ciliated cells transfected with control siRNA and prdx1 siRNA. prdx1 knockdown significantly reduced the number of cilia in MDCK cells. (E) Specificity of prdx1 knockdown in MDCK cells transfected with Prdx1siRNA was confirmed by RT-PCR examination as well as western blot studies. Significant reduction in levels of prdx1 mRNA and proteins was observed in MDCK cells transfected with Prdx1siRNA. (F) Control and prdx1-injected (200 pg) embryos were treated with 2 μM H2O2 at stage 8.5. Embryos at the stage 33 were used for whole-mount in situ hybridization, and proximal tubules in the pronephros were visualized with a smp30 probe. H2O2-disrupted proximal tubule formation in the pronephros, and abnormal proximal tubule formation was rescued in Prdx1-injected embryos. (G) Graph showing the pronephros development in embryos co-treated with H2O2 and prdx1. Reduced expression of smp30 in H2O2 treated embryos was rescued by prdx1.

Loss of Prdx1 leads to the formation of fewer primary cilia and increased ROS levels in MDCK cells

Next, we sought to elucidate the molecular mechanism underlying the Prdx1 regulation of Wnt signaling during pronephros development. Both canonical and non-canonical Wnt signaling pathways are required for normal ciliary function32–34. In addition, abnormal ciliary function is the primary cause of kidney defects during development35. Therefore, we speculated that Prdx1 is necessary for cilia formation. To address this, we evaluated cilia formation in Madin-Darby, canine kidney (MDCK) cell lines after prdx1 knockdown. We transfected MDCK cell lines with 10 nM control or prdx1 siRNAs and observed the effects on primary cilia formation. As previously reported, the ROS levels were higher in prdx1-silenced MDCK cells than in the control, thus validating the efficacy of the siRNA-mediated knockdown of prdx1 (Fig. S3). Cilia were then stained using an acetylated-tubulin antibody. The number of cilia in MDCK cells transfected with prdx1 siRNAs was significantly lower than in cells transfected with control siRNAs (Fig. 4C–E). To validate that the Prdx1 overexpression inhibit the effects caused by increased ROS production, we treated MDCK cells with 100 μM H2O2 and observed the effect H2O2 on the expression of phosphorylated kinases (P-AKT, P-AMPKα and P-ERK). We found that treatment of MDCK cells with H2O2 enhanced the phosphorylation of AKT (P-AKT) while the phosphorylation of AMPKα (P-AMPKα) was reduced but the H2O2 treatment of MDCK cells transfected with prdx1 exhibited reverse expression i.e. P-AKT was downregulated while P-AMPKα showed upregulated expression (Fig. S3B). Induced P-ERK by H2O2 was not affected by expression of Prdx1 in transfected MDCK cells. These altered level of expression by prdx1 transfection confirmed that prdx1-inhibited the H2O2 mediated responses (Fig. S3B). Taken together, these data indicate that an uncontrolled increase in the ROS levels results in ciliary defects that lead to severe malformations in the pronephros and Prdx1 significantly inhibits the responses induced by increased ROS production.

Prdx1 overexpression rescues the ROS-induced disruption of proximal tubule formation in the pronephros

Kidney dysfunction associates with increased ROS levels. Prdx1 regulates the production of ROS and protects tissues from the damaging effects of ROS36, 37. We treated control or prdx1-overexpressed stage 8.5 embryos with H2O2 (an inducer of ROS production), evaluated the effects of ROS overproduction on proximal tubule formation, and examined the role of Prdx1 in ROS regulation and pronephros development. For this purpose we treated embryos with different concentration of H2O2 and found that embryos treated with 2 μΜ concentration of H2O2 did not exhibit defects in most organs including pronephros but severe malformations in majority of the organs including pronephros were observed for embryos treated with higher concentrations of H2O2. The treatment of embryos with H2O2 inhibited proximal tubule formation in the pronephros (Fig. 4F,G), indicating that ROS affects proximal tubule formation in the pronephros. In addition, the abnormal phenotype was restored by prdx1 overexpression (Fig. 4F,G). Overall, these data indicate that Prdx1 regulates the production of ROS, which is important for normal proximal tubule formation in the pronephric duct. In conclusion, Prdx1 is essential for pronephros development during primary cilia formation, and it functions by regulating ROS levels.

Discussion

Prdx1 is an antioxidant protein involved in many biological processes. Previous studies indicate that Prdx1 not only regulates the cellular ROS levels; it also functions in different cell signaling pathways and plays a role in vertebrate development38. In the current study, we demonstrated a role for Prdx1 in pronephros development during X. laevis embryogenesis and showed that Prdx1 is essential for X. laevis pronephrogenesis.

A number of genes expressed in the pronephros regulate its development39. Our results showed that prdx1 is upregulated in the developing pronephros. The MO-mediated knockdown of prdx1 resulted in the decreased expression of the proximal tubule-specific markers smp30, xPteg, and pax2 (Fig. 1). The developmental defects in the pronephros due to prdx1 depletion were further confirmed by immunohistochemistry using the proximal tubule-specific antibody 3G8 (Fig. 1). Moreover, rescue experiments highlighted the importance of prdx1 in pronephros development. The reduced expression of proximal tubule-specific markers and the inhibition of pronephros formation were restored by co-injection with prdx1* RNA (Fig. 1). In summary, our findings clearly demonstrate that Prdx1 is essential for X. laevis pronephrogenesis.

The antioxidant properties of Prdx1 as a regulator of cellular ROS levels have been established16. Structural analysis of Prdx1 showed two conserved cysteine residues of Prdx1, namely, Cys-52 and Cys-178, to be largely responsible for the antioxidant properties of Prdx118. In this study, the roles of these conserved cysteine residues in pronephros development were evaluated using Prdx1-Flag mutants carrying Cys-53- or Cys-173-to-serine point mutations. These mutants were co-injected with WT prdx1 RNA. Results of the immunoprecipitation assay showed that only WT prdx1, and not the mutants, was present in the immunocomplexes (Fig. 2A,B). In addition, co-injection of embryos with the prdx1 MOs and the prdx1* mutant RNAs, followed by whole-mount in situ hybridization with a smp30 probe, confirmed the functional importance of these conserved cysteine residues, as well as their antioxidant effects during pronephrogenesis (Fig. 2C,D). These results indicate that the conserved cysteine residues are crucial for pronephros development during X. laevis embryogenesis.

RA signaling is critical for pronephrogenesis, and the inhibition of RA signaling results in developmental defects in the pronephros during X. laevis embryogenesis12. Results of the in vitro kidney induction assay demonstrated that Prdx1 functions as a significant modulator of RA signaling during pronephros development. RT-PCR and real time PCR results revealed a decrease in the expression of the pronephric markers lim1, pax2, smp30, and pax8, which resulted from prdx1 depletion. The decreased expression of these markers was restored by co-injection with prdx1* RNA (Fig. 3A,B). The functional significance of Prdx1 in RA signaling-mediated pronephrogenesis was further verified by epistatic experiments. Embryos were co-injected with prdx1 MOs and pronephros-specific RNAs. Whole-mount in situ hybridization revealed that the decreased expression of smp30 was restored by injection with lim1 RNA, but not with activated RARα-vp16 or pax8 (Fig. 3C,D). Taken together, these results show that Prdx1 functions as a downstream mediator of the RA signaling pathway during pronephros development.

In addition, both canonical and non-canonical Wnt signaling pathways are essential for pronephros development in X. laevis embryos. The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is crucial for kidney development. An inhibition of this pathway results in abnormalities in the pronephric tubule, glomus, and duct and leads to the reduced expression of pronephros-specific markers40. In addition, Wnt/β-catenin independent signaling is responsible for proximal tubule formation during pronephrogenesis8, 9, 41.

The role of Prdx1 in Wnt signaling-mediated pronephros development was investigated using Dsh deletion constructs, namely, DshΔDEP and DshΔDIX. Our results showed that the prdx1 MO-induced inhibition of pronephros formation was rescued by injection with Dsh WT mRNA, but not with DshΔDEP or DshΔDIX. These results indicate that Prdx1 functions upstream of Wnt signaling during pronephrogenesis.

Finally, we explored the mechanism by which Prdx1 regulates Wnt signaling-dependent pronephros development. Cilia are necessary for both canonical and non-canonical Wnt signaling32–34. We found that Prdx1 is necessary for primary cilia development in MDCK cells. siRNA transfection and immunofluorescent studies showed that the loss of Prdx1 resulted in a significant reduction in the number of cells with primary cilia (Fig. 4C–E). These data show that Prdx1 plays a critical role in primary cilia formation in MDCK cells and suggest that Prdx1 regulates cilia formation. In addition, we demonstrated that ROS overproduction due to H2O2 treatment inhibited proximal tubule formation in X. laevis embryos. This abnormal phenotype was rescued by prdx1 overexpression (Fig. 4F,G). These results are consistent with previous findings showing that ROS regulation by Prdx1 is crucial for pronephros development.

In conclusion, our results indicate that Prdx1 is indispensable for pronephrogenesis, which is regulated by RA and Wnt signaling pathways. During pronephros development, Prdx1 modultes RA signaling and Wnt signaling. Our data support the idea that Prdx1 primarily functions in the elimination of excess ROS and it is required for pronephros development, where it presumably acts by modulating ROS levels.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

This study was performed in strict accordance with the documented standards of the Animal Care and Use Committee and in agreement with international laws and policies (National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, publication no. 85-23, 1985). The Institutional Review Board of the Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology approved the experimental use of amphibians (approval no. UNISTACUC-16-14). All members of the research group attended educational and training courses on the proper care and use of experimental animals. Adult aquatic frogs (X. laevis), obtained from the Korean Xenopus Resource Center for Research, were housed at 18 °C under conditions of 12 h light/12 h dark in approved containers obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology. There were no unexpected animal deaths during this study.

Plasmids, MOs, and mRNAs used for the microinjection of X. laevis embryos

A cDNA clone encoding full-length prdx1 was obtained from ATCC (GenBank ID: NM_001092016.1). The prdx1 MO sequence (25 bp) was 5′-ATG TCT GCC GGA AAC GCA AAA ATT G-3′ (Gene Tools, Philomath, OR, USA). Flag-tagged prdx1 (wild-type; active-site mutants; and M1, M2, and M1/M2) and HA-tagged prdx1 were amplified by PCR and subcloned into pCS2 + or pCS107, respectively. For microinjections, prdx1, active rar, pax8, and lim1 cDNAs were linearized with ApaI, NotI, NotI, and BamHI, respectively. The capped mRNAs were synthesized using the mMessage mMachine Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. mRNAs and the MOs were microinjected into both blastomeres of two-cell stage embryos that were incubated until the desired developmental stage was reached. For the rescue experiments, the MO-resistant mRNAs containing four point mutations in the wobble codons after the ATG start codon were subcloned into pCS107 and then microinjected.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization of X. laevis embryos

Embryos at the 33-cell stage were fixed in MEMFA buffer (4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M MOPS, 1 mM MgSO4, and 2 mM EGTA, pH 7.4) for 2 h at room temperature. To prepare the antisense digoxigenin (Dig)-labeled probe, prdx1, smp30, xPteg, and pax2 cDNAs were linearized with BamHI, NcoI, SacI, and EcoRI, respectively. The probes were generated using the mMessage mMachine Kit and detected with an alkaline phosphatase-labeled anti-Dig antibody (1:1000, Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and BM purple dye.

RT-PCR and real time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from injected embryos at cell stages ranging from 0 to 40. cDNAs were synthesized by reverse transcription using the PrimeScript First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara, Shiga, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. PCR was carried out using specific primer pairs (Table 1). The PCR products were electrophoresed on 1% agarose gels, and images were then captured using Wise Capture I-1000 software (Daihan Scientific, Seoul, South Korea).

Table 1.

Primers used for RT-PCR.

| Gene | Forward primer (5′ → 3′) | Reverse primer (5′ → 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| odc 44 | GTCAATGATGGAGTGTATGGATC | TCCATTCCGCTCTCCTGAGCAC |

| lim1 45 | AAGACTCTGAAAGTGCCAATG | AGTCTGAGCTTGAGACGATG |

| pax2 27 | ATGGATATGCACTGCAAGGC | TCTTGCTCACACATCCATGG |

| smp30 25 | ATGGAGGAAGAGTGATCCGCATAGATCCTG | TCCGATGTTGCCTGAACACTGAGAGC |

| pax8 45 | TCAGCTCAGGATGCTCAGC | GCTGTAGTAATAGGGATAGC |

For real-time PCR, cDNA templates were amplified with specific PCR primer sets (Table 2) using SYBR Premix Ex Taq according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Takara, Shiga, Japan) and analyzed with a StepOnePlus™Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Relative expression levels of the target genes were analyzed using the comparative Ct (2-DDCt) method42. All data are representative of at least three experiments. The Primer3 program was used to design primers and odc was used as an internal control43.

Table 2.

Primers used for real time PCR.

| Gene | Forward primer (5′ → 3′) | Reverse primer (5′ → 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| odc | TGGCTGCACTGATCCACAG | TAAAGCCAAGCTCAGCCCC |

| lim1 | GCCCTGGCAGCAACTATGA | CCATTGCACCAAGGGGAGT |

| pax2 | ATCCGGGACAGGCTTTTGG | TGGGGTTGGATGGAATGGC |

| smp30 | TGGAGGCCCGGATTACTCA | CCTCCAGATTGAGGCTGGC |

| pax8 | CTCTCAAGGCAGTGTGGGG | GGAAGTGACACTCCAGGGC |

Western blot analysis

For western blotting, injected whole embryos were lysed in lysis buffer (137 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, 1% Nonidet-P40, and 10% glycerol, pH 8.0) containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5 mM sodium orthovandate, and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail. The lysates were heated for 5 min at 95 °C in loading buffer and then electrophoresed on 12% SDS-PAGE gels. Proteins were cross-reacted with anti-Flag-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and anti-HA-HRP conjugated (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) antibodies. Immunoreactive bands were detected using the HyGLO™ Kit (Denville Scientific, South Plainfield, NJ, USA).

Co-immunoprecipitation assay

Lysates from injected embryos were incubated with 2 μg of HA IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) in the same buffer used for western blotting for 1 h at 4 °C. The immunocomplexes were pulled down with 15 μL of protein A/G PLUS agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) overnight at 4 °C. Agarose beads were washed thrice in a low-salt lysis buffer. Western blot analysis was performed using anti-Flag-HRP and anti-HA-HRP conjugated primary antibodies.

MDCK cell culture

MDCK cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in minimum essential medium (MEM) (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) containing 5% fetal bovine serum (Welgene, Seoul, Korea) and 100 U/mL streptomycin/penicillin.

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

MDCK cells were fixed in 100% methanol in Lab-TEK chambers. Immunofluorescent staining was performed using monoclonal anti-acetylated-tubulin (1:500, Sigma) and Flag (1:500, Applied Biological Materials, Richmond, Canada) antibodies. Alexa Fluor 568 anti-mouse IgG (1:1000, Invitrogen) was used as the secondary antibody. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride, 1:5000, Invitrogen), and cells were examined under a Zeiss LSM7 PASCAL confocal microscope. Image processing and analysis were performed with ImageJ and Adobe Photoshop software, respectively.

Immunohistochemistry

Embryos were fixed in MEMFA buffer for 2 hours at room temperature and then washed with PBS. Immunostaining is performed by using 3G8/4A6 (antibodies specific for proximal tubules/ intermediate, distal and connecting tubules) primary antibodies. Then the embryos were treated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG + IgM secondary antibodies (Invitrogen).

Statistical analysis

Data from whole-mount in situ hybridization experiments were analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health; http://imagej.nih.gov). Results are presented as the means ± standard error (n = 5 with replicates per sample). To determine statistical significance, results were analyzed by one-way ANOVA or unpaired t-tests. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant and is indicated on graphs by an asterisk. p-values of <0.01 and <0.001 are indicated by two and three asterisks, respectively.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) [grant no. NRF-2015R1A2A1A10053265] and the Ministry of Science, ICT, and Future Planning (MSIP) [grant no. 2015R1A4A1042271], the Republic of Korea.

Author Contributions

S.C., H.-K.L., Y.-K.K., Y.J., H.-J.S., C.K., K.-J.M., and T.I. performed the experiments; S.C., Y.-K.K., and H.-S.L. analyzed the data; J.-W.P., O.-S.K., B.-S.K., D.-S.L., J.-S.B., S.-H.K., T.-G.K., M.-J.P., J.-K.H., T.-J.K., T.-J.P., and H.-S.L. developed the concepts, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Soomin Chae, Hyun-Kyung Lee and Yoo-Kyung Kim contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-09262-6

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Tae-Joo Park, Email: parktj@unist.ac.kr.

Hyun-Shik Lee, Email: leeh@knu.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Vize PD, Jones EA, Pfister R. Development of the Xenopus pronephric system. Dev Biol. 1995;171:531–540. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vize PD, Seufert DW, Carroll TJ, Wallingford JB. Model systems for the study of kidney development: use of the pronephros in the analysis of organ induction and patterning. Dev Biol. 1997;188:189–204. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wessely O, Tran U. Xenopus pronephros development–past, present, and future. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26:1545–1551. doi: 10.1007/s00467-011-1881-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan T, Asashima M. Growing kidney in the frog. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2006;103:e81–85. doi: 10.1159/000092192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carroll T, Wallingford J, Seufert D, Vize PD. Molecular regulation of pronephric development. Curr Top Dev Biol. 1999;44:67–100. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(08)60467-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brandli AW. Towards a molecular anatomy of the Xenopus pronephric kidney. Int J Dev Biol. 1999;43:381–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hensey C, Dolan V, Brady HR. The Xenopus pronephros as a model system for the study of kidney development and pathophysiology. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17(Suppl 9):73–74. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.suppl_9.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyons JP, et al. Requirement of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in pronephric kidney development. Mechanisms of Development. 2009;126:142–159. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang B, Tran U, Wessely O. Expression of Wnt signaling components during Xenopus pronephros development. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCoy KE, Zhou X, Vize PD. Non-canonical wnt signals antagonize and canonical wnt signals promote cell proliferation in early kidney development. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:1558–1566. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller RK, et al. Pronephric tubulogenesis requires Daam1-mediated planar cell polarity signaling. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. 2011;22:1654–1664. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010101086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi W, et al. Heat shock 70-kDa protein 5 (Hspa5) is essential for pronephros formation by mediating retinoic acid signaling. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:577–589. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.591628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerlach GF, Wingert RA. Zebrafish pronephros tubulogenesis and epithelial identity maintenance are reliant on the polarity proteins Prkc iota and zeta. Developmental biology. 2014;396:183–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wingert RA, Davidson AJ. Zebrafish nephrogenesis involves dynamic spatiotemporal expression changes in renal progenitors and essential signals from retinoic acid and irx3b. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2011;240:2011–2027. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carroll, T. J., Wallingford, J. B. & Vize, P. D. Dynamic patterns of gene expression in the developing pronephros of Xenopus laevis. Dev Genet24, 199-207, doi:10.1002/(sici)1520-6408(1999) (1999). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Neumann CA, et al. Essential role for the peroxiredoxin Prdx1 in erythrocyte antioxidant defence and tumour suppression. Nature. 2003;424:561–565. doi: 10.1038/nature01819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shuvaeva TM, Novoselov VI, Fesenko EE, Lipkin VM. Peroxiredoxins, a new family of antioxidant proteins. Bioorg Khim. 2009;35:581–596. doi: 10.1134/s106816200905001x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong S, Kim CY, Lee JH, Seong GJ. Immunohistochemical localization of 2-Cys peroxiredoxins in human ciliary body. Tissue Cell. 2007;39:365–368. doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim SY, Kim TJ, Lee K-Y. A novel function of peroxiredoxin 1 (Prx-1) in apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1)-mediated signaling pathway. FEBS Letters. 2008;582:1913–1918. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chu G, et al. Identification and verification of PRDX1 as an inflammation marker for colorectal cancer progression. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8:842–859. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim JH, et al. RNA-binding properties and RNA chaperone activity of human peroxiredoxin 1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;425:730–734. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.07.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim JH, et al. Up-regulation of peroxiredoxin 1 in lung cancer and its implication as a prognostic and therapeutic target. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2326–2333. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daly KA, Lefevre C, Nicholas K, Deane E, Williamson P. Characterization and expression of Peroxiredoxin 1 in the neonatal tammar wallaby (Macropus eugenii) Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;149:108–119. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pirson M, Knoops B. Expression of peroxiredoxins and thioredoxins in the mouse spinal cord during embryonic development. The Journal of comparative neurology. 2015;523:2599–2617. doi: 10.1002/cne.23807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cartry J, et al. Retinoic acid signalling is required for specification of pronephric cell fate. Dev Biol. 2006;299:35–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee SJ, Kim S, Choi SC, Han JK. XPteg (Xenopus proximal tubules-expressed gene) is essential for pronephric mesoderm specification and tubulogenesis. Mechanisms of development. 2010;127:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan TC, Takahashi S, Asashima M. A role for Xlim-1 in pronephros development in Xenopus laevis. Dev Biol. 2000;228:256–269. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang HY, Lee TH. Antioxidant enzymes as redox-based biomarkers: a brief review. BMB reports. 2015;48:200–208. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2015.48.4.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ariizumi T, Asashima M. In vitro induction systems for analyses of amphibian organogenesis and body patterning. The International journal of developmental biology. 2001;45:273–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park TJ, Gray RS, Sato A, Habas R, Wallingford JB. Subcellular localization and signaling properties of dishevelled in developing vertebrate embryos. Current biology: CB. 2005;15:1039–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rothbacher U, et al. Dishevelled phosphorylation, subcellular localization and multimerization regulate its role in early embryogenesis. The EMBO journal. 2000;19:1010–1022. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.5.1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lancaster MA, Schroth J, Gleeson JG. Subcellular spatial regulation of canonical Wnt signalling at the primary cilium. Nature cell biology. 2011;13:700–707. doi: 10.1038/ncb2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.May-Simera HL, et al. Ciliary proteins Bbs8 and Ift20 promote planar cell polarity in the cochlea. Development. 2015;142:555–566. doi: 10.1242/dev.113696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ross AJ, et al. Disruption of Bardet-Biedl syndrome ciliary proteins perturbs planar cell polarity in vertebrates. Nature genetics. 2005;37:1135–1140. doi: 10.1038/ng1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown JM, Witman GB. Cilia and Diseases. Bioscience. 2014;64:1126–1137. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biu174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Graves JA, Metukuri M, Scott D, Rothermund K, Prochownik EV. Regulation of reactive oxygen species homeostasis by peroxiredoxins and c-Myc. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:6520–6529. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807564200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agharazii M, et al. Inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species as mediators of chronic kidney disease-related vascular calcification. American journal of hypertension. 2015;28:746–755. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpu225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jarvis RM, Hughes SM, Ledgerwood EC. Peroxiredoxin 1 functions as a signal peroxidase to receive, transduce, and transmit peroxide signals in mammalian cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53:1522–1530. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buisson I, Le Bouffant R, Futel M, Riou JF, Umbhauer M. Pax8 and Pax2 are specifically required at different steps of Xenopus pronephros development. Dev Biol. 2015;397:175–190. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cizelsky W, Tata A, Kuhl M, Kuhl SJ. The Wnt/JNK signaling target gene alcam is required for embryonic kidney development. Development. 2014;141:2064–2074. doi: 10.1242/dev.107938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tauriello DVF, et al. Wnt/β-catenin signaling requires interaction of the Dishevelled DEP domain and C terminus with a discontinuous motif in Frizzled. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:E812–E820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114802109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yuan JS, Reed A, Chen F, Stewart CN., Jr. Statistical analysis of real-time PCR data. BMC bioinformatics. 2006;7 doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rozen S, Skaletsky H. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;132:365–386. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bouwmeester T, Kim S, Sasai Y, Lu B, De Robertis EM. Cerberus is a head-inducing secreted factor expressed in the anterior endoderm of Spemann’s organizer. Nature. 1996;382:595–601. doi: 10.1038/382595a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sato A, Asashima M, Yokota T, Nishinakamura R. Cloning and expression pattern of a Xenopus pronephros-specific gene, XSMP-30. Mechanisms of development. 2000;92:273–275. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4773(99)00331-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.