Abstract

Four unusual meroterpenoids, dysivillosins A–D (1–4), were isolated from an organic extract of the marine sponge Dysidea villosa collected from the South China Sea. Their planar structures were determined by 1D and 2D NMR and HRESIMS techniques, while the relative and absolute configurations were elucidated by NOESY experiments and comparison between the calculated and experimental ECD spectra. To the best of our knowledge, dysivillosins A–D are the first examples of terpene-polyketide-pyridine hybrid metabolites from the nature. Anti-allergic activity evaluation showed that compounds 1–4 potently inhibited the release of β-hexosaminidase, a marker of degranulation, in a dose-dependent manner with IC50 values of 8.2–19.9 μM. Additionally, the four meroterpenoids could downregulate the production of lipid mediator leukotrienes B4 (LTB4) and pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-4 (IL-4) in the antigen-stimulated RBL-2H3 mast cells. Further biological investigations revealed that dysivillosin A (1) could suppress the phosphorylation of Syk and PLCγ1 in IgE/FcɛRI/Syk signaling pathway, which resulted in the inhibition of degranulation and the downregulation of LTB4 and IL-4 production in mast cells.

Introduction

Mast cells have long been considered as important effector cells in immunoglobulin E (IgE)-associated immune responses1. IgE binds to mast cells via its high-affinity receptor, FcεRI, and cross-linking of FcɛRI-bound IgE molecules by allergen triggers a cascade of signaling events which leads to mast cell degranulation and the release of allergic mediators characteristic of type I hypersensitivity reactions2–4. FcεRI aggregation initiates Src family kinases, and subsequently activates another key tyrosine kinase, Syk, which is most essential for the activation of various downstream signaling molecules, such as GTPase, Ras, PI3K, and PLCγ15. Therefore, FcεRI-proximal kinase, Syk, has recently been proposed as an excellent therapeutic target for the treatment of allergic diseases5.

Marine sponges are rich sources of diverse bioactive metabolites with unusual chemical scaffolds6. As part of our search for new anti-allergic compounds from the South China Sea marine sponges, several sponge specimens have been collected and screened for their inhibitory activity against β-hexosaminidase, a degranulation indicator of mast cells. Among them, the MeOH extract of Dysidea villosa showed the most potent inhibitory activity against β-hexosaminidase with a IC50 value of 5.3 μg/mL. Detailed bioassay-guided fractionation of the active organic extract led to the isolation of four unusual meroterpenoids, dysivillosins A–D (1–4), as depicted in Fig. 1. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of terpene-polyketide-pyridine hybrid metabolites from the nature. All the four compounds were evaluated for their anti-allergic activity, they could significantly inhibit β-hexosaminidase and the production of LTB4 and IL-4 in antigen-stimulated RBL-2H3 mast cells. Further investigations showed that anti-allergic activity of dysivillosin A was triggered by suppressing Syk/PLCγ1 signaling pathway.

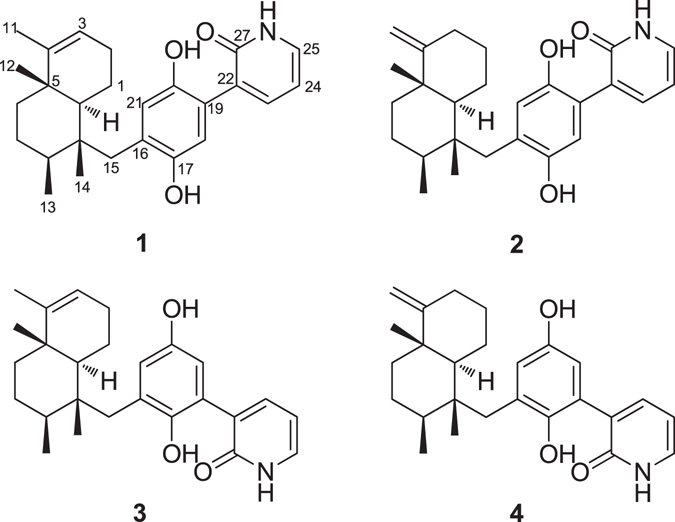

Figure 1.

Structures of dysivillosins A–D (1–4).

Results and Discussion

Dysivillosin A (1) was isolated as an amorphous powder ([α]D 26 + 26.5) and gave a molecular formula of C26H33NO3 with 11 degrees of unsaturation, as determined by HRESIMS data. The IR spectrum indicated the presence of hydroxy (3185 cm−1), carbonyl (1713 and 1662 cm−1), and benzene (1591 and 1440 cm−1) groups7, 8, whereas the UV absorption maxima at 216, 255, and 303 nm were indicative of a 2-pyridone unit9. The 1H NMR spectrum of dysivillosin A (1) (Table 1) displayed the resonances for four methyls at δ H 0.94, 1.03, 1.20, and 1.45, two singlet aromatic protons at δ H 7.59 and 7.74, three mutually coupling olefinic protons at δ H 7.17 (1 H, dd, J = 7.8, 4.8 Hz), 8.13 (1 H, dd, J = 7.8, 1.8 Hz), and 8.46 (1 H, dd, J = 4.8, 1.8 Hz), along with a phenolic hydroxy proton at δ H 11.65. The 13C NMR and HSQC spectra revealed the presence of one conjugated carbonyl (δ C 163.5), four aromatic quaternary carbons [δ C 120.8, 128.4, 147.8 (oxygenated), and 153.9 (oxygenated)], two olefinic quaternary carbons (δ C 117.0 and 143.6), two aromatic methines (δ C 106.1 and 114.9), four olefinic methines (δ C 118.4, 120.4, 129.1, and 145.4), two aliphatic quaternary carbons (δ C 38.0 and 41.8), two aliphatic methines (δ C 36.0 and 45.9), five methylenes (δ C 19.5, 26.3, 27.4, 35.6, and 37.8), and four methyls (δ C 17.3, 17.4, 17.6, and 19.6). These above NMR spectroscopic features were characteristic of a sesquiterpene hydroquinone containing a 2-pyridone unit10.

Table 1.

1H (600 MHz) and 13C (150 MHz) NMR Data for Dysivillosins A–D (1–4) in Pyr-d 5.

| Position | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ C | δ H (J in Hz) | δ C | δ H (J in Hz) | δ C | δ H (J in Hz) | δ C | δ H (J in Hz) | |

| 1α | 19.5, CH2 | 2.33, m | 22.8, CH2 | 2.35, m | 19.1, CH2 | 2.39, m | 22.5, CH2 | 2.41, m |

| 1β | 1.63, m | 1.55, dd (12.0, 2.4) | 1.57, m | 1.53, dd (12.0, 3.6) | ||||

| 2a | 26.3, CH2 | 2.38, m | 28.0, CH2 | 1.93, m | 26.1, CH2 | 2.23, m | 27.9, CH2 | 1.92, m |

| 2b | 2.14, m | 1.59, m | 2.07, m | 1.35, m | ||||

| 3α | 120.4, CH | 5.16, brs | 32.6, CH2 | 2.36, m | 120.4, CH | 4.98, brs | 32.5, CH2 | 2.26, td (15.0, 4.8) |

| 3β | 2.11, m | 1.96, m | ||||||

| 4 | 143.6, C | 159.4, C | 143.1, C | 159.0, C | ||||

| 5 | 38.0, C | 39.9, C | 37.8, C | 39.8, C | ||||

| 6α | 35.6, CH2 | 0.89, td (13.2, 3.6) | 36.4, CH2 | 1.29, dd (13.2, 3.6) | 35.5, CH2 | 0.75, td (13.2, 3.6) | 36.3, CH2 | 1.14, td (13.2, 3.6) |

| 6β | 1.49, dt (12.6, 3.0) | 1.45, m | 1.41, dt (12.6, 3.6) | 1.35, m | ||||

| 7α | 27.4, CH2 | 1.32, m | 27.4, CH2 | 1.42, m | 27.0, CH2 | 1.20, dd (13.2, 3.6) | 27.0, CH2 | 1.41, m |

| 7β | 1.37, td (12.6, 1.2) | 1.39, m | 1.30, td (13.2, 3.0) | 1.35, m | ||||

| 8 | 36.0, CH | 1.81, m | 36.3, CH | 1.76, m | 35.9, CH | 1.69, m | 36.2, CH | 1.63, m |

| 9 | 41.8, C | 42.2, C | 41.3, C | 41.6, C | ||||

| 10 | 45.9, CH | 1.55, d (12.0) | 48.2, CH | 1.36, dd (12.0, 2.4) | 45.9, CH | 1.39, dd (12.6, 1.2) | 48.3, CH | 1.20, dd (12.0, 1.8) |

| 11a | 17.6, CH3 | 1.45, br s | 102.6, CH2 | 4.46, s | 17.5, CH | 1.35, br s | 102.6, CH2 | 4.32, s |

| 11b | 4.38, s | 4.28, s | ||||||

| 12 | 19.6, CH3 | 1.03, s | 20.0, CH3 | 1.06, s | 19.5, CH3 | 0.96, s | 20.0, CH3 | 0.99, s |

| 13 | 17.3, CH3 | 1.20, d (6.6) | 17.4, CH3 | 1.20, d (6.6) | 16.6, CH3 | 1.09, d (6.6) | 16.8, CH3 | 1.10, d (6.6) |

| 14 | 17.4, CH3 | 0.94, s | 17.3, CH3 | 0.93, s | 17.3, CH3 | 0.87, s | 17.2, CH3 | 0.88, s |

| 15a | 37.8, CH2 | 3.13, s | 37.7, CH2 | 3.09, d (14.4) | 37.2, CH2 | 3.20, d (14.4) | 37.3, CH2 | 3.12, d (14.4) |

| 15b | 3.04, d (14.4) | 2.93, d (14.4) | 2.88, d (14.4) | |||||

| 16 | 128.4, C | 128.2, C | 124.1, C | 123.9, C | ||||

| 17 | 153.9, C | 153.8, C | 147.9, C | 149.7, C | ||||

| 18 | 106.1, CH | 7.74, s | 106.1, CH | 7.69, s | 122.3, C | 122.4, C | ||

| 19 | 120.8, C | 120.8, C | 105.0, CH | 7.68, d (2.4) | 105.1, CH | 7.63, d (3.0) | ||

| 20 | 147.8, C | 147.8, C | 154.3, C | 154.2, C | ||||

| 21 | 114.9, CH | 7.59, s | 114.6, CH | 7.53, s | 120.0, CH | 7.26, d (2.4) | 119.7, CH | 7.20, d (3.0) |

| 22 | 117.0, C | 117.0, C | 117.3, C | 117.2, C | ||||

| 23 | 129.1, CH | 8.13, dd (7.8, 1.8) | 129.1, CH | 8.10, dd (7.8, 1.8) | 129.5, CH | 8.21, dd (7.2, 1.8) | 129.4, CH | 8.18, dd (7.8, 1.8) |

| 24 | 118.4, CH | 7.17, dd (7.8, 4.8) | 118.4, CH | 7.16, dd (7.8, 4.8) | 118.6, CH | 7.21, dd (7.2, 4.8) | 118.5, CH | 7.16, dd (7.8, 4.8) |

| 25 | 145.4, CH | 8.46, dd (4.8, 1.8) | 145.4, CH | 8.45, dd (4.8, 1.8) | 145.8, CH | 8.52, dd (4.8, 1.8) | 145.8, CH | 8.50, dd (4.8, 1.8) |

| 27 | 163.5, C | 163.5, C | 163.3, C | 163.3, C | ||||

| 17-OH | 11.65, br s | 11.63, br s | 11.67, br s | 11.63, br s | ||||

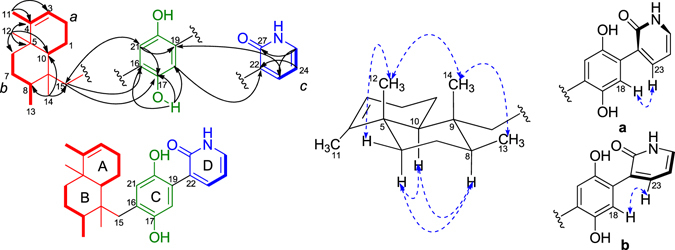

The COSY correlations of H2-1/H-10, H2-1/H2-2, H2-2/H-3, H2-6/H2-7, H2-7/H-8, H-8/H3-13, H-23/H-24, and H-24/H-25 coupled with HSQC spectrum revealed the presence of three isolated spin systems: (a) C-10–C-1–C-2–C-3, (b) C-6–C-7–C-8–C-13, and (c) C-23 –C-24–C-25, as shown in Fig. 2. The elongation from C-3 to C-11 was evident from the allylic COSY correlation of H-3/H3-11. The connections of the three spin systems with the other carbons were mainly determined by analysis of the HMBC spectrum. The long-ranged HMBC correlations of H3-11/C-3, C-4, and C-5 and H3-12/C-4, C-5, C-6, and C-10 connected the two partial structures a and b via C-5 in rings A and B and also allowed the assignment of the two methyls at C-4 and C-5, respectively. Moreover, the HMBC correlations of H3-13/C-7 and C-9 and H3-14/C-8, C-9, C-10, and C-15 established a tetramethyl decalin sesquiterpene moiety with a methylene CH2-15 tethered at C-9. This assignment was supported by the HMBC correlations of H-10/C-4, C-5, C-6, C-9, C-14 and C-15 and H2-15/C-8, C-9, C-10, and C-14. In the down field, the aromatic proton H-18 showed HMBC correlations with C-16 and the oxygenated aromatic carbon C-20, meanwhile H-21 showed HMBC correlations with C-19 and oxygenated aromatic carbon C-17, which indicated the presence of a 1,4-hydroquinone unit (ring C) in 1. The HMBC correlations from the phenolic hydroxy proton at δ H 11.65 to C-16, C-17, and C-18 assigned the phenolic hydroxy group at C-17. Additionally, HMBC correlations of H2-15/C-16, C-17, and C-21 and H-21/C-15 suggested that the sesquiterpene fragment was linked to hydroquinone unit through the carbon bond C-15–C-16 (Fig. 2)10. What’s more, HMBC correlations of H-24/C-22 and H-23/C-27, and H-25/C-27 coupled with the remaining conjugated amide carbonyl C-27 (δ C 163.5) indicated the presence a 2-pyridone substructure (ring D). Finally, HMBC correlations of H-18/C-22 and H-23/C-19 determined that the 2-pyridone unit was tethered at C-19 in the hydroquinone, supported by the NOESY correlation of H-18/H-23.

Figure 2.

Key COSY, HMBC, and NOESY correlations of 1.

Once the planar structure of 1 was established, its relative configuration was addressed by NOESY experiments, as shown in Fig. 2. The large coupling constant value of H-10 (J = 12.0 Hz) and the chemical shift of CH3-12 (δ C 19.6/δ H 1.03) suggested the trans-fusion of the bicyclic system (rings A/B)11, 12, which was confirmed by the NOESY correlations of H3-12/H-6β and H-10/H-6α. The NOESY correlations of H-8/H-10 and H-6α/H-10 indicated the α-orientation of the three protons, meanwhile the correlations of H3-12/H3-14 and H3-13/H3-14 assigned the three methyl groups as β-orientation. Thus, the relative configuration of 1 was determined as 5S*, 8S*, 9R*, 10S*, as depicted in Fig. 2. Additionally, the aromatic proton H-18 in the hydroquinone unit showed NOESY correlations with H-23 in the 2-pyridone moiety, which suggested the presence of two possible configurations (a and b) of the axial chiral center C-19–C-22 (Fig. 2).

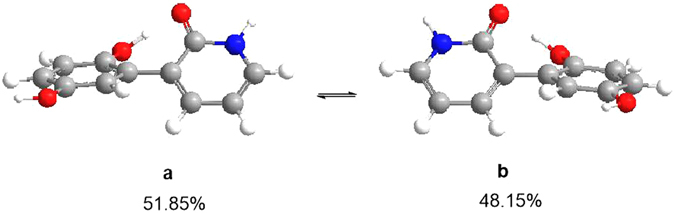

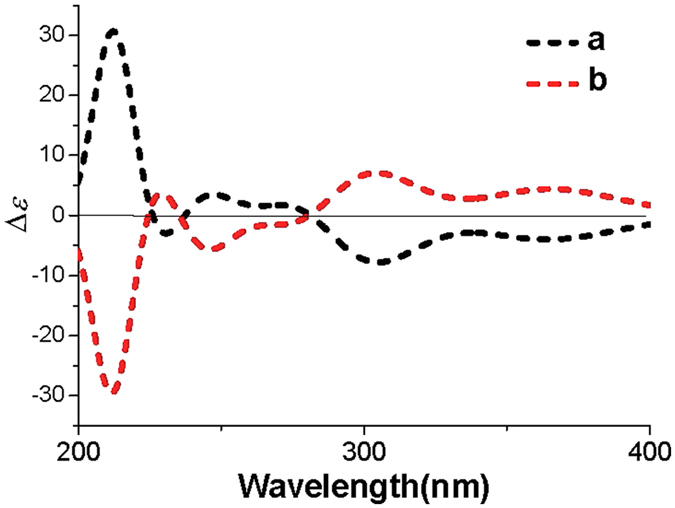

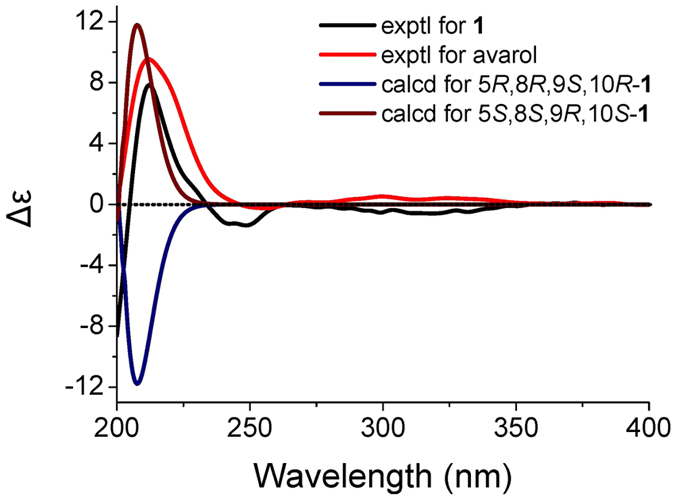

Despite of the best efforts, the crystallization of 1 was finally unsuccessful. In order to determine the whole absolute configuration of 1, quantum chemical ECD calculation methods were employed to determine the absolute configuration of 1 13. Firstly, a hydroquinone-2-pyridone model structure was used to investigate the configuration of the axial chirality in the structure of 1 by HF/6-31G(d) method in Gaussian0914. Only two equilibrium conformers (a and b) were found using molecular mechanics (ΔE = 0–5 kcal/mol), as shown in Fig. 3, which is identical with the deduction form the NOESY experiment. The Boltzman population ratios of the two conformers are 51.85% (a) and 48.15% (b) at the temperature of 298.15 K, and their dihedral angels are 37.5° and 37.6°, respectively. It was interesting to find that the Cotton effects (CEs) in the calculated ECD spectrum of a were opposite to those of b, as shown in Fig. 4. The majority of axial chiral compounds have a rotational barrier sufficiently high to prevent racemization of the atropisomers at room temperature, and the separation of stereoisomers at room temperature requires energy barriers of at least 22 kcal/mol15. However, conformer a could easily convert to b with the energy barriers of less than 5 kcal/mol, which suggested that the axial chiral center in compound 1 could isomerize from M to P atropisomer at room temperature. Therefore, the whole absolute configuration of 1 was mainly determined by the configurations of four chiral centers (C-5, C-8, C-9 and C-10) in the sesquiterpene moiety. Subsequently, two optimized stereoisomers, (5R, 8R, 9S, 10R)-1 and (5S, 8S, 9R, 10S)-1, were built based on the relative configuration of 1, their ECD spectra were calculated at the level of PBE0/6-311 ++ G (2d, 2p) with MeOH as the solvent16, 17. The positive CE at 210 nm in the calculated spectrum of the 5S, 8S, 9R, 10S enantiomer matched well with the CE observed in the experimental ECD spectrum of 1 (Fig. 5), which determined the absolute configuration of 1 as 5S, 8S, 9R, 10S, identical with that of avarol.

Figure 3.

The two conformers ((a) and (b)) of hydroquinone-2-pyridone (ΔE = 0–5 kcal/mol). The Boltzman population ratios of a and b are respective of 51.85% and 48.15% at the temperature of 298.15 K.

Figure 4.

The calculated ECD spectra of the two conformers (a and b) for hydroquinone-2-pyridone.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the experimental ECD spectra of 1 and avarol to the calculated ECD spectra of 1 and its enantiomer.

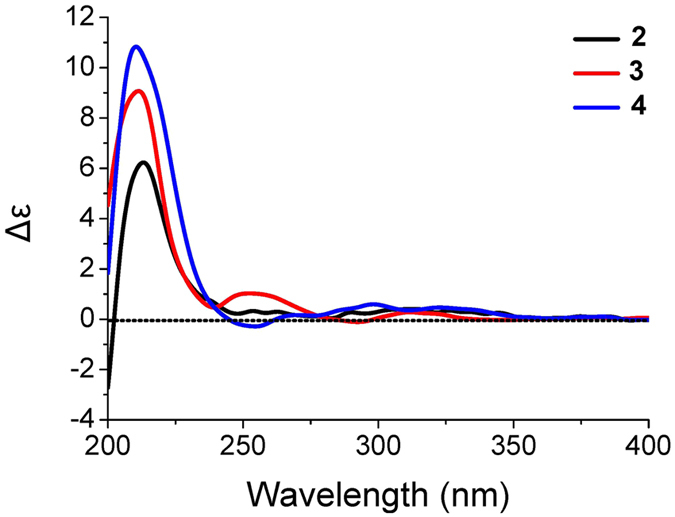

Dysivillosin B (2) was assigned the same molecular formula C26H33NO3 as that of 1 by HRESIMS data. The 1H and 13C NMR data of 2 corresponded closely to those of 1 (Table 1), except for three subunits, a methylene CH2-3 (δ C 32.6/δ H 2.36, 2.11), an olefinic quaternary carbon C-4 (δ C 159.4), and an exomethylene CH2-11 (δ C 102.6/δ H 4.46, 4.38), which implied that the avarol sesquiterenoid fragment in 1 was replaced by an neoavarol fragment in 2 18. This assignment was further supported by detailed analyses of COSY and HMBC correlations (Figure S1). Similar NOESY correlations and CE in the ECD spectrum (Fig. 6) showed that dysivillosin B shared the same relative and absolute configurations with those of 1.

Figure 6.

Experimental ECD spectra of 2–4.

Dysivillosin C (3) was also obtained as an isomer of 1, based on the HRESIMS data. Comprehensive analysis of the 1H and 13C NMR data of 3 (Table 1) showed that the only difference between 1 and 3 was the position of 2-pyridone, which tethered at C-18 in 3 rather than at C-19 in 1. This assignment was supported by HMBC correlations of H-19/C-22 and H-23/C-18 as well as the NOESY correlation of H-19/H-23 (Figure S1). Subsequent analyses of the NOESY and ECD spectra of 3 disclosed that its relative and absolute configurations were both consistent with those of 1 (Fig. 6).

The HRESIMS data indicated that dysivillosin D (4) was an isomer of 1–3. Detailed comparison of the NMR data of 4 with those of 2 indicated that the main difference was the position of 2-pyridone in the hydroquinone unit (Table 1). Key HMBC correlations of H-19/C-22 and H-23/C-18 positioned the 2-pyridone at C-18 (Figure S1). Identical NOESY correlations and similar CE in the ECD spectrum showed that dysivillosin D shared the same relative and absolute configurations with those of 1–3, as shown in Fig. 6.

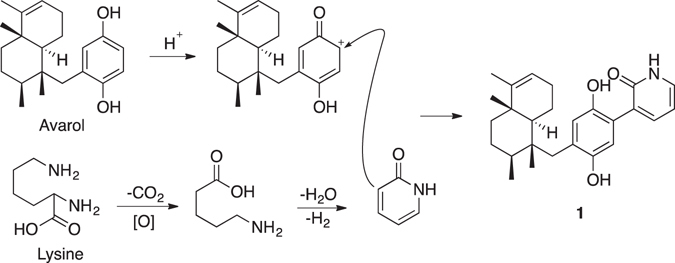

There are a large number of naturally occurring derivatives of avarol/avarone and meroterpenoids where the hydroquinone/quinone is substituted by amines and amino acids19–23. Recently, Anderson et al. reported the structure of avinosol, a meroterpenoid-nucleoside conjugate24. However, dysivillosins A–D (1–4) are the first example of terpene-polyketide-pyridine hybrid compounds from the nature. The proposed biosynthesis of 1–4 could be involved with the biosynthetic pathways of three precursors: terpenoid, acetate, and pyridine. The four compounds could be biogenetically related to two meroterpenoids, avarol and neoavarol, which were both isolated from marine sponges belonging to the Dysidea genus10, 18, 25. As shown in Fig. 7, 2-pyridone might be produced by L-lysine via successive decarboxylation, amidation, and dehydrogenation reactions26. Subsequent nucleophilic attack from the 2-pyridone to the hydroquinone unit in avarol could finally result in the formation of dysivillosin A (1)27.

Figure 7.

Plausible Biogenetic Pathway of 1.

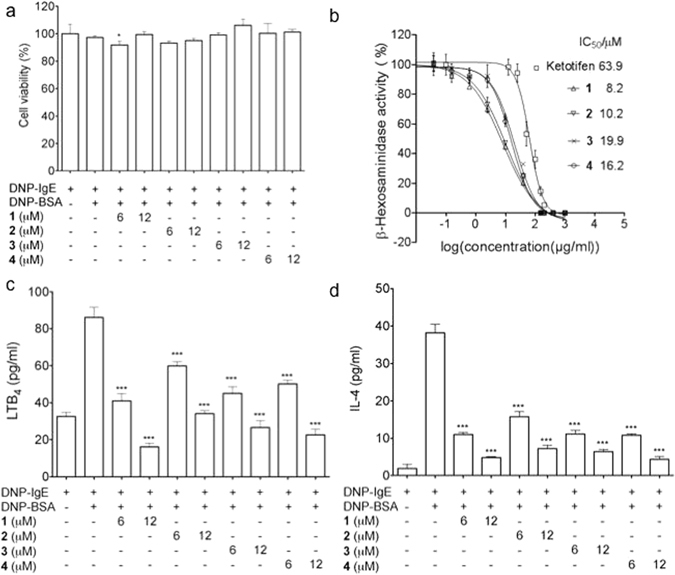

The four compounds (1–4) from D. villosa were screened for their anti-allergic activity on rat basophilic leukemia (RBL-2H3) cells. All of them showed no cytotoxicity on RBL-2H3 cells at the concentrations of 6 and 12 μM, as depicted in Fig. 8a. Subsequently, the inhibitory activity of 1–4 on the degranulation in DNP-IgE-activated RBL-2H3 mast cells was examined, using ketotifen as a positive control28. Dysivillosins A–D were found to potently inhibit the release of β-hexosaminidase, a marker of degranulation, in a dose-dependent manner with IC50 values of, 8.2, 10.2, 19.9, and 16.2, respectively (Fig. 8b). As the main allergic mediators released by mast cells, lipid mediator LTB4 and pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-4 are involved in acute allergic responses29, 30, and the inhibitory activity of 1–4 on LTB4 and IL-4 was investigated as well. As depicted in Fig. 8c and d, all the four compounds could dose dependently downregulate the production of LTB4 and IL-4 in the antigen-stimulated RBL-2H3 mast cells at the concentrations of 6 and 12 μM. Among the four compounds, dysivillosin A (1) showed the most potent anti-allergic activity, and thus was selected for further inhibitory activity evaluation on the antigen specific IgE/FcɛRI/Syk signaling pathway, because both of the degranulation and subsequent production of LTB4 and IL-4 in mast cells are triggered by cross-linking of FcεRI-bound IgE molecules31, 32.

Figure 8.

(a) Cytotoxic effects of 1–4 on RBL-2H3 cells. (b) Inhibitory effects of 1–4 on the release of β-hexosaminidase in DNP-IgE-activated RBL-2H3 cells. (c) Inhibitory activity on lipid mediator LTB4 secretion of 1–4 in RBL-2H3 cells. (d) Inhibition of IL-4 production of 1–4 in RBL-2H3 cells. Data are presented as the mean ± SD values of triplicate determinations. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus DNP-BSA-treated group (n = 3). Data are analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s Multiple Comparison Post-Test (GraphPad Prism 5.0).

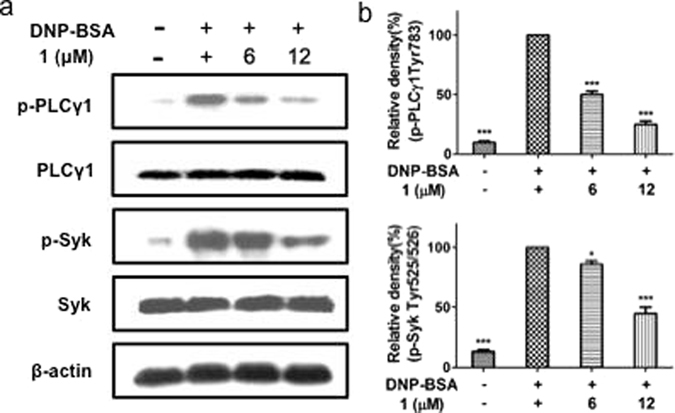

Interestingly, we found that dysivillosin A (1) could significantly inhibit the activation of Syk as well as its downstream signaling molecule, PLCγ1, as shown in Fig. 9a and b. this finding indicated that dysivillosin A could inhibit mast cell activation by suppressing the phosphorylation of Syk and PLCγ1, which subsequently inhibited the degranulation and downregulated the production of LTB4 and IL-4. These results highlight the potential of dysivillosin A (1) as a new chemotherapeutic scaffold targeting Syk-associated allergy.

Figure 9.

Comparison of the dysivillosin A (1) inhibited the activation of signaling molecules in antigen-stimulated RBL-2H3 cells. IgE-sensitized RBL-2H3 cells (2 × 106 cells/well) were stimulated with 1 μg/ml DNP-BSA for 15 min in the presence or absence of 1. The levels of p-Syk, Syk, p-PLCγ1 and PLCγ1 were measured by immunoblotting analysis. (a) The blots are representative of three independent experiments. (b) The data are presented as means ± SD. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 versus DNP-BSA-treated group (n = 3). Data are analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s Multiple Comparison Post-Test (GraphPad Prism 5.0).

Methods

General experimental procedures

Optical rotations were measured with an Autopol I-30575 (l = 10 cm) and UV spectra on a Hitachi U-3010 spectrophotometer; IR spectra (KBr) were obtained with a Jasco FTIR-400 spectrometer, whereas ECD spectra were obtained on a Jasco J-810 spectropolarimeter. NMR spectra were obtained with a Bruker Avance NMR spectrometer at 600 MHz for 1H and 150 Hz for 13C using Pyr-d 5 as solvent. HRESIMS data were obtained on an Agilent 6210 LC/MSD TOF mass spectrometer.

Collection, extraction, and isolation

Samples of Dysidea villosa were collected from the coast of Yongxing Island in South China sea on May 7th, 2011. The voucher sample of D. villosa (XD110507A) was maintained at the Research Center for Marine Drugs, State Key Laboratory of Oncogenes and Related Genes, Department of Pharmacy, Ren Ji Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. The animals (520 g, wet weight) was extracted by MeOH repeatedly to give 9.2 g extract, which showed potent inhibitory activity against β-hexosaminidase (IC50 = 5.3 μg/mL). The bioactive extract was dissolved in 500 mL water, and partitioned with the same volume of CH2Cl2 four times to yield 8.7 g CH2Cl2-soluble fraction, which was subjected to a silica gel chromatography column eluted with gradient n-hexane and EtOAc, yielding 14 subfractions (DA-DN). Fraction DK (1.2 g) was passed through open ODS chromatography column eluted with gradient aqueous MeOH, size-exclusion chromatography Sephadex LH-20 eluted with CH2Cl2/MeOH (1:1), and then purified by reversed-phased HPLC (YMC C18 column, 10 × 250 mm, 2 mL/min, 297 nm) with a elution of 80% CH3CN, to give dysivillosin A (1, 7.0 mg, t R 79.1 min), dysivillosin B (2, 2.3 mg, t R 74.0 min), dysivillosin C (3, 6.4 mg, t R 62.3 min), and dysivillosin D (4, 2.7 mg, t R 58.1 min).

Dysivillosin A (1): colorless solid; [α]D 26 + 26.5 (c 0.1, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λ max (logε) 216 (4.12), 255 (3.90), 303 (4.08), 331 (3.65) nm; CD (MeOH) λ (Δε) 212 (+8.51) nm; IR (KBr) ν max 3185, 2960, 2922, 2854, 1713, 1662, 1591, 1444, 1261, 1166, 1094, 1021, 799 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR data see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 388.2274 [M - H2O - H]− (calcd for C26H30NO2, 388.2277).

Dysivillosin B (2): colorless solid; [α]D 26 + 6.7 (c 0.1, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λ max (logε) 202 (4.01), 248 (3.54), 301 (3.74), 326 (3.34) nm; CD (MeOH) λ (Δε) 209 (+5.56) nm; IR (KBr) ν max 2958, 2924, 2855, 1735, 1665, 1634, 1592, 1444, 1378, 1260, 1162, 1093, 1023, 800 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR data see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 388.2275 [M - H2O - H]− (calcd for C26H30NO2, 388.2277).

Dysivillosin C (3): colorless solid; [α]D 26 + 4.2 (c 0.3, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λ max (logε) 216 (4.11), 254 (3.70), 297 (3.91), 326 (3.33) nm; CD (MeOH) λ (Δε) 210 (+9.21) nm; IR (KBr) ν max 3194, 2957, 2925, 2856, 1713, 1664, 1620, 1594, 1461, 1403, 1379, 1253, 1171 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR data see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 388.2279 [M - H2O - H]− (calcd for C26H30NO2, 388.2277).

Dysivillosin D (4): colorless solid; [α]D 26 + 8.5 (c 0.1, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λ max (logε) 205 (4.08), 244 (3.60), 297 (3.85), 326 (2.82) nm; CD (MeOH) λ (Δε) 207 (+11.03) nm; IR (KBr) ν max 3203, 2959, 2925, 2855, 1737, 1666, 1616, 1595, 1495, 1454, 1261, 1174, 1093, 1022, 800 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR data see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 388.2279 [M - H2O - H]− (calcd for C26H30NO2, 388.2277).

Energy Minimization and ECD Calculations

The molecule of 1 was converted into SMILES code before its initial 3D structure was generated with CORINA version 3.4. The conformer database of 1 was generated using CONFLEX version 7.0 with an energy window for acceptable conformers (ewindow) of 5 kcal mol−1 above the ground state using the modified version of the MMFF94 force field. Each conformer was optimized with the HF/6-31G(d) method in Gaussian09. Further optimization at the B3P86/6-31G(d) level led to the observed dihedral angles. The optimized conformers were taken for the ECD calculations, which were performed with Gaussian09 (B3P86/6-311++G(2d,p))13. The solvent effects were taken into account by the conductor-like polarizable continuum model (MeOH as the solvent)14, 16. To gain ECD curves from the output files that were suited for comparison with the experimental data, the length representation of the oscillator and rotatory strengths was always selected and the spectra were overlaid with Gaussian profiles that were in turn summed to give, after Boltzmann weighting of the individual spectra, a calculated ECD spectrum.

Cell Culture

Rat basophilic leukemia (RBL-2H3) cells from the cell bank of Shanghai Science Academy were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), which contains 10% (v/v) FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin, at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Cell Viability

MTT (3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2-H-tetrazolium bromide) assay was conducted to examine cell viability. RBL-2H3 cells (5 × 105 cells/well, 100 μL/well) were plated into a 96-well plate. After 24 h of incubation, cells were incubated with compounds 1–4 for 3 hours and the medium was replaced by MTT solution (250 μg/ml) and incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. The medium was then carefully discarded and the formazan was resuspended in 150 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The absorbance was measured at 490 nm using a microplate reader. Values measured from untreated cells were considered to represent 100% viability.

β-hexosaminidase Release Activity

RBL-2H3 cells were seeded in a 24-well plate (5 × 105 cells/well), and were sensitized with dinitrophenyl (DNP)-specific IgE (DNP-IgE) (1 μg/mL) at 37 °C for overnight. DNP-IgE-sensitized cells were preincubated with sponge extracts or dysivillosins A–D (1–4) for 30 min, and then stimulated with DNP-BSA for 1.5 h. To measure the activity of β-hexosaminidase released from the cells, the cultured media were centrifuged (17,000 g, 10 min) at 4 °C. The supernatant (50 μL) was mixed with 50 μL of 0.1 M sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.5) containing 10 mM 4-nitrophenyl N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminide in a 96-well plate, and then was incubated at 37 °C for 90 min. The absorbance was measured at 405 nm after terminating the reaction by 0.2 M glycine (pH 10.0).

Determination of IL-4 and LTB4

To measure Interleukin-4 (IL-4) and Leukotriene B4 (LTB4) level in the cultured media, all cultured media were centrifuged at 4 °C, and the test compounds were stored at −80 °C until assay. IL-4 and LTB4 were quantified using an ELISA kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunoblot Analysis

After cell collection and extraction with the protein extraction solution, the protein samples were subjected to 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). The protein spots were electrotransferred to a PVDF membrane, and then the membrane was incubated with blocking buffer (Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.05% Tween-20 and 5% w/v nonfat dry milk) for 1 h and was washed by TBST (TBS containing 0.05% Tween-20) three times, each time for 5 min, followed by a diluted solution of anti-p-syk, anti-syk, anti-p-PLCγ1, and anti-PLCγ1 antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology) overnight at 4 °C. In addition, the blots probed with a 1:1000 diluted solution of anti-β-actin antibody (Abcam) were used as internal control to keep each well loading with the same amount of protein. The membrane was washed by TBST for three times, each time for 10 min, shaken in a solution of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-linked anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody, and washed by TBST for another three times, each time for 10 min. The expressions of proteins were detected by enhanced chemiluminescent (ECL) reagent (Thermo Scientific), followed by exposure of the membranes to photographic film (Fujifilm Corporation). The intensity of blots were analyzed and quantitated with ImageJ software.

Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison Test with GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Prism version 5.01 for Windows, San Diego, CA, USA). The values are expressed as the means ± SD. The differences with p < 0.05 were considered significant.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 41576130, U1605221, 41476121, 81370494, 81403160, 81302691, and 81402844), the Foundation of the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (No. 14431901300), and Shenzhen Innovation of Science and Technology Commission programs (No. ZDSYS201506050935272, JCYJ20150403091931191, YLWS20140609102809065, and 201401099).

Author Contributions

Wei-Hua Jiao designed and conducted the main experiments, data analyses, and wrote the manuscript. Bao-Hui Cheng performed the anti-allergic activity of the four compounds. Guo-Hua Shi extracted the marine sponge samples and purified the four compounds. Guo-Dong Chen conducted the ECD calculation for the compound 1. Bin-Bin Gu conducted the ECD calculation for the compounds 2–4. Yong-Jun Zhou revised the biogenetic pathway of compound 1. Li-Li Hong measured the optical values of the four compounds. Fan Yang assisted the sample collection. Zhi-Qiang Liu assisted the anti-allergic activity evaluation. Shu-Qi Qiu assisted the identification of the sample species. Zhi-Gang Liu revised the biological part of the manuscript. Ping-Chang Yang helped design the anti-allergic activity. Hou-Wen Lin helped design the chemical experiments.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Wei-Hua Jiao and Bao-Hui Cheng contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-04021-z

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ping-Chang Yang, Email: pcy2356@163.com.

Hou-Wen Lin, Email: franklin67@126.com.

References

- 1.Gail S, Tsai M. IgE and mast cells in allergic disease. Nat. Med. 2012;18:693–704. doi: 10.1038/nm.2755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kraft S, et al. The tetraspanin CD63 is required for efficient IgE-mediated mast cell degranulation and anaphylaxis. J. Immunol. 2013;191:2871–2878. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee YS, Hur S, Kim TY. Homoisoflavanone prevents mast cell activation and allergic responses by inhibition of Syk signaling pathway. Allergy. 2014;69:453–462. doi: 10.1111/all.12356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim JK, et al. Spiraeoside inhibits mast cells activation and IgE-mediated allergic responses by suppressing phospholipase C-γ-mediated signaling. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2014;93:227–235. doi: 10.1139/bcb-2014-0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li X, et al. NecroX-5 suppresses IgE/Ag-stimulated anaphylaxis and mast cell activation by regulating the SHP-1-Syk signaling module. Allergy. 2016;71:198–209. doi: 10.1111/all.12786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blunt JW, et al. Marine natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2015;32:116–211. doi: 10.1039/C4NP00144C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang J, et al. Arthpyrones A–C, pyridone alkaloids from a sponge-derived fungus Arthrinium arundinis ZSDS1-F3. Org. Lett. 2015;17:656–659. doi: 10.1021/ol503646c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haga A, et al. Pyridone alkaloids from a marine-derived fungus, Stagonosporopsis cucurbitacearum, and their activities against azole-resistant Candida albicans. J. Nat. Prod. 2013;76:750–754. doi: 10.1021/np300876t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang Y, et al. Casuarinines A–J, lycodine-type alkaloids from Lycopodiastrum casuarinoides. J. Nat. Prod. 2013;76:1475–1484. doi: 10.1021/np4003355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minale L, Riccio R, Sodano G. Avarol a novel sesquiterpenoid hydroquinone with a rearranged drimane skeleton from the sponge Disidea avara. Tetrahedron Lett. 1974;15:3401–3404. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)91918-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Guzman FS, et al. Bolinaquinone: A novel cytotoxic sesquiterpene hydroxyquinone from a Philippine Dysidea Sponge. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:8042–8044. doi: 10.1021/jo981037t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiao WH, et al. Dysiherbols A–C and Dysideanone E, cytotoxic and NF-κB inhibitory tetracyclic meroterpenes from a Dysidea sp. marine sponge. J. Nat. Prod. 2016;79:406–411. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b01079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li CS, et al. Meroterpenoids with antiproliferative activity from a Hawaiian-plant associated fungus Peyronellaea coffeae-arabicae FT238. Org. Lett. 2016;18:2335–2338. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian09, Revision B.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2010.

- 15.Leroux F. Atropisomerism, Biphenyls, and Fluorine: A comparison of rotational barriers and twist angles. ChemBioChem. 2004;5:644–649. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weigend F, Ahlrichs R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005;7:3297–3305. doi: 10.1039/b508541a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yanai T, Tew DP, Handy NC. A new hybrid exchange–correlation functional using the Coulomb-attenuating method (CAM-B3LYP) Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004;393:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2004.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iguchi K, Sahashi A, Kohno J, Yamada Y. New sesquiterpenoid hydroquinone and quinones from the Okinawan marine sponge (Dysidea sp.) Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1990;38:1121–1123. doi: 10.1248/cpb.38.1121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cimino G, De Rosa S, Cariello L, Zanetti L. Structure of two biologically active sesquiterpenoid amino-quinones from the marine spongeDysidea avara. Experientia. 1982;38:896. doi: 10.1007/BF01953638. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alvi KA, et al. Evaluation of new sesquiterpene quinones from two Dysidea sponge species as inhibitors of protein tyrosine kinase. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:6604–6607. doi: 10.1021/jo00050a043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kobayashi J, Madono T, Shigemori H. Nakijiquinones C and D, new sesquiterpenoid quinones with a hydroxy amino acid residue from a marine sponge inhibiting c-erbB-2 kinase. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:10867–10874. doi: 10.1016/0040-4020(95)00661-Q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takahashi Y, et al. Nakijiquinones J–R, sesquiterpenoid quinones with an amine residue from Okinawan marine sponges. J. Nat. Prod. 2010;73:467–471. doi: 10.1021/np900470e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiao WH, et al. Dysidaminones A–M, cytotoxic and NF-κB inhibitory sesquiterpene aminoquinones from the South China Sea sponge Dysidea fragilis. RSC Adv. 2014;4:9236–9246. doi: 10.1039/C3RA47265E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diaz-Marrero AR, et al. Avinosol, a meroterpenoid-nucleoside conjugate with antiinvasion activity isolated from the marine sponge Dysidea sp. Org. Lett. 2006;8:3749–3752. doi: 10.1021/ol061333p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiao WH, et al. Dysidavarones A–D, new sesquiterpene quinones from the marine sponge Dysidea avara. Org. Lett. 2012;14:202–205. doi: 10.1021/ol202994c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salame R, Gravel E, Leblanc K, Poupon E. Biomimetic synthesis of tangutorine following new biogenetic proposals. Org. Lett. 2009;11:1891–1894. doi: 10.1021/ol9002916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yadav JS, Reddy BVS, Swamy T. Bi (OTf) 3-catalyzed conjugate addition of indoles to p-quinones: a facile synthesis of 3-indolyl quinones. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:9121–9124. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2003.10.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsubara M, et al. Differential regulation of IL-4 expression and degranulation by anti-allergic olopatadine in rat basophilic leukemia (RBL-2H3) cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2004;67:1315–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siraganian RP. Mast cell signal transduction from the high-affinity IgE receptor. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2003;15:639–646. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu M, Yokomizo T. The role of leukotrienes in allergic diseases. Allergol. Int. 2015;64:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gifillan AM, Tkaczyk C. Integrated signalling pathways for mast-cell activation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006;6:218–230. doi: 10.1038/nri1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalesnikoff J, Galli SJ. New developments in mast cell biology. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:1215–1223. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.