Abstract

Quantum electron-vibrational dynamics in molecular systems at finite temperature is described using an approach based on Thermo Field Dynamics theory. This formulation treats temperature effects in the Hilbert space without introducing the Liouville space. The solution of Thermo Field Dynamics equations with a novel technique for the propagation of Tensor Trains (Matrix Product States) is implemented and discussed. The methodology is applied to the study of the exciton dynamics in the Fenna-Mathews-Olsen complex using a realistic structured spectral density to model the electron-phonon interaction. The results of the simulations highlight the effect of specific vibrational modes on the exciton dynamics and energy transfer process, as well as call for careful modeling of electron-phonon couplings.

Introduction

Unraveling the role of quantum effects in the time evolution of various molecular systems and assemblies under realistic conditions at ambient temperatures is a key problem of modern physical and biological chemistry1. Long range energy and charge transfer in natural as well as in artificial systems are among the most important processes in which quantum coherent motion can be of relevance2–5. However, a proper understanding of these processes is often hampered by the impossibility to properly simulate the evolution of quantum systems with many degrees of freedom.

The quasi-adiabatic path integral (QUAPI)6 and the hierarchical equations of motion (HEOM)7–9 are among the most successful numerically exact methods for density matrix propagation. However, both methods become numerically demanding at low temperature10 and when the Hilbert space of the system is very large8, 10–15. A number of approximate methods based on density matrix formalism is also available, but their range of validity can be very limited and system dependent16–25. Numerically accurate evolution of large systems has also been described by the density matrix renormalization group (DMRG) methodology, and the associated time-evolution algorithms26, 27.

Wave function propagation methods employing a basis set representation, such as the multiconfiguration time-dependent Hartree (MCTDH) method and its multilayer extension (ML-MCTDH)28, 29, Gaussian based MCTDH and other basis set methods30–33, are powerful tools at very low temperature34, but become unhandy in high temperature cases, as their application requires a statistical sampling of the initial conditions and faces both theoretical and computational difficulties35–37. On the other hand, basis set methods are very versatile, and capable of handling a large variety of Hamiltonian operators38, 39.

The development of alternative approaches to the simulation of many body quantum dynamics at ambient conditions is therefore indispensable for better understanding and proper exploitation of quantum effects in nanosystems. In this work we discuss a novel theoretical methodology based on Thermo Field Dynamics theory40, 41 that combines an accurate Hamiltonian description of quantum dynamics at finite temperature with the flexibility of a basis set representation42. We then apply this methodology to the study of exciton dynamics in the Fenna-Matthews-Olsen (FMO) complex, which has nowadays become a “guinea pig” of exciton dynamics theory and quantum biology1, 2, 43, 44. The exciton dynamics at FMO has been simulated by all major numerically exact quantum methods, e.g. QUAPI45, HEOM46, 47, ML-MCTDH48. Several explicit parameterizations of the bath spectral density accounting for the impact of intra- and inter-molecular modes on the FMO dynamics have been developed49, 50. In the present work, we simulate exciton dynamics in FMO at ambient temperature modeling the electron-phonon interaction with a realistic spectral density obtained from experimental data51.

Results

Quantum Dynamics at Finite Temperature

Problems formulated in the quantum mechanics language require the calculation of the expectation value of some dynamical variable, A

where ρ(0) is the initial density matrix of the system, and A(t) = e iHt Ae −iHt is the Heisenberg representation of the operator A, H being the system Hamiltonian ( = 1). The trace operation implies a weighted sum over all the thermally accessible states. In most molecular systems the energies of the electronic degrees of freedom are usually much higher than the vibrational energies. The effect of a finite temperature is then to create a thermal population of excited vibrational states, while only one electronic state of the entire system, |e〉, is tangibly populated. Within the validity of this condition we can safely employ the approximation

| 1 |

Here Z is the proper partition function and ρ vib is the equilibrium Boltzmann distribution of the vibrational degrees of freedom, which, in the present work, is described using harmonic approximation, and β = 1/k B T, where T is the temperature of system and k B the Boltzmann constant. Consequently, the trace operation involves only a summation over a thermal distribution of vibrational states,

| 2 |

where are the creation (destruction) operators of the k-th bosonic degree of freedom with frequency ω k, and the cyclic invariance of the trace operation has been used for the symmetrization. Following the Thermo Field Dynamics approach40 the above trace can be evaluated by introducing a set of auxiliary boson operators and their corresponding occupation number states , and rewriting the summation as52

| 3 |

The dummy tilde variables do not affect the expectation value since A(t) is independent of them, and the states form a complete orthonormal set. We notice that in the above summation the numerical values of {n k} and are identical. Defining the so called thermal vacuum state

| 4 |

where represent the vacuum state of the ensemble of physical and tilde bosons, and

| 5 |

the expectation value 3 becomes53

| 6 |

The above equation is an extension of the fundamental result of Thermo Field Dynamics40, 54, 55 and the transformation e −iG is often referred to as Bogoliubov thermal transformation56. Equation 6 can be equivalently written as (see Methods section, and ref. 42)

| 7 |

where the wavefunction |φ(t)〉 satisfies the Schrödinger equation

| 8 |

with the thermal operators

| 9 |

The modified Hamiltonian operator is defined as

| 10 |

where is any operator acting in the vibrational tilde space. Equations 7, 8, 9 and 10 are the main theoretical result of the work. In the methodology described above the evaluation of the thermal average 〈A(t)〉 can be reduced to the solution of the thermal Schrödinger equation 8 with the Hamiltonian specified by Eq. 9, followed by the computation of the desired expectation value.

Since the coupling with the tilde space doubles the number of nuclear degrees of freedom, and since a thermal environment can be realistically mimicked only using hundreds or thousands degrees of freedom, the solution of the time-dependent Schrödinger equation 8 requires efficient numerical methods, suitable to treat a large number of dynamical variables38. Here we follow our recently proposed methodology42 and represent the full vibronic wavefunction using the so-called Tensor-Train (TT) format (Matrix Product States, MPS, in the physics literature)57–59. Equation 8 is then solved using a methodology based on the time-dependent variational principle (TDVP) recently developed by Lubich, Oseledets and Vandereycken59. The reader is referred to the original papers58, 60 for a detailed analysis of the TT decomposition, and to the Methods section (see also ref. 42).

Exciton Dynamics in the FMO complex

In order to apply the above methodology to the study of exciton dynamics at finite temperature in the FMO complex we consider a widely employed model Hamiltonian in which a set {|n〉}, of coupled electronic states interacts linearly with a phonon bath

| 11 |

Here |n〉 describes an electronic state with the excitation localized on the n-th pigment, ε n is the electronic energy of state |n〉, J nm are electronic couplings, ω k are the frequencies of the bath of harmonic oscillators, and the parameters g nk determine the strength of the electron-phonon coupling. In the above notation the index k labels all the vibrations of the system.

The modified thermal Hamiltonian which controls the finite temperature dynamics is readily obtained applying the Bogoliubov thermal transformation to the Hamiltonian operator 1142

| 12 |

Here we have used to exploit the invariance properties of the thermal Bogoliubov transformation56. At T → 0 the mixing parameters θ k become zero, sinh (θ k) → 0, the coupling to the tilde space disappears, and the standard Schrödinger equation is recovered as expected. For high-frequency modes, , sinh (θ k) ≈ 0 and cosh (θ k) ≈ 1 even at room temperature. As a rule of thumb high-frequency modes need not be incorporated into the tilde Hamiltonian. This leads to additional reduction of the active space and computational savings.

The exciton part of the FMO Hamiltonian, the site energies ε n and electronic couplings J nm, have been retrieved from ref. 61. Vibronic coherences are essentially determined by the distribution of the bath vibrational frequencies and their coupling constants g nk. Here we consider the general case in which the excited states of each BChl are independently coupled to a bath of N phonons (uncorrelated baths). Consequently, in the seven site FMO model, we have 7N vibrations, characterized by the coupling parameters g nk. Since a single pigment is excited in each electronic state, only N components of g nk with are nonzero for a given n. These parameters are assumed to be the same for all BChls and are conveniently specified by the so called bath spectral density49, 50

| 13 |

We also point out that in our methodology the values of the parameters g nk can be determined using any method of choice, and no particular benefit is derived from the above specific assumption. Often the Drude-Lorentz spectral density is used, J(ω) = 2γλω/(γ 2 + ω 2), which however deviates substantially from the measured spectral density at 4 K51. Recent theoretical analyses suggest that the use of a structured spectral density can lead to quite relevant changes in the vibronic dynamics of the system47, 48, 62, 63.

Following the very recent work by Schulze et al.48, we model the electron-phonon interaction by discretizing the experimental spectral density of ref. 51 with N = 74 vibrations uniformly distributed in the range [2,300 cm−1]. This way the times corresponding to the frequency ω min = 2 cm−1 and the line spacing Δω = (ω max − ω min)/N are safely beyond the observed time evolution of the system. Accordingly, our model consists of 74 vibrations per molecular site, thus 518 overall vibrational degrees of freedom which are doubled to 1036 due to TFD methodology. The numerical approach to the solution of this problem is described in the Methods section.

The parameters g kn cosh (θ k) and g kn sinh (θ k) entering the thermal Hamiltonian govern the coupling of the electronic subsystem with physical and tilde bosonic degrees of freedom. Hence, it is tempting to introduce the spectral densities

| 14 |

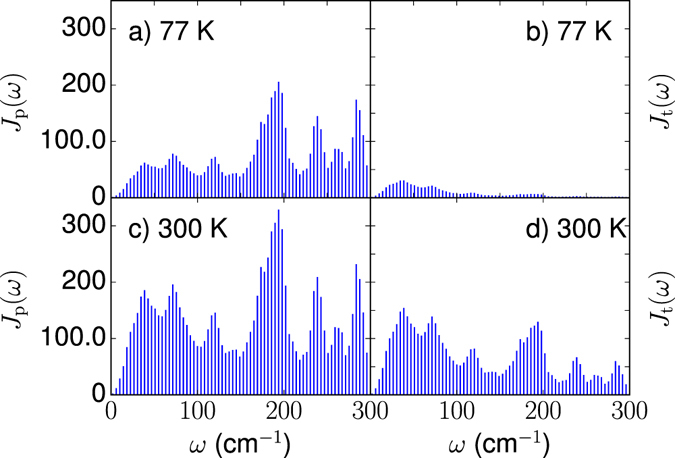

which describe the electron-vibrational couplings in the physical (subscript p) and tilde (subscript t) subspace. As temperature goes to zero, J p(ω) → J(ω) and J t(ω) → 0. The two spectral densities are reported in Figure 1 at 77 K and 300 K. The comparison of lower and upper panels in Figure 1 reveals how effective electron-vibrational coupling increases with temperature, notably for lower-frequency modes.

Figure 1.

Effective site spectral densities J p(ω) and J t(ω) describing the coupling of the physical and tilde bosonic degrees of freedom with the electronic subsystem at different temperatures. (a,b) 77 K, (c,d) 300 K.

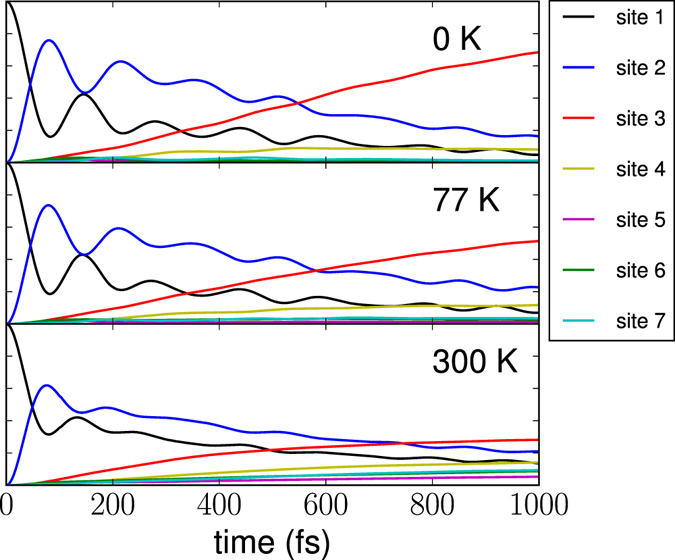

Figure 2 shows the total time-dependent populations p n(t) of seven (n = 1–7) BChla molecules of the FMO complex (standard numbering of the FMO cofactors is used). The populations are evaluated by Eqs 7 and 8 for A = A θ = |n〉 〈n| so that p n(t) = 〈A(t)〉. The initial excitation is assumed to be initially localized on site 1. In all panels, p 1(t) and p 2(t) exhibit pronounced oscillations, as expected45, 46.

Figure 2.

The time evolution of the electronic populations p n(t) of seven (n = 1–7) BChla molecules of the FMO complex at different temperatures indicated in the panels. The initial excitation is localized on site 1.

At T = 0 K (upper panel) the populations are in perfect agreement with the results obtained by Schulze and coworkers using ML-MCTDH48.

At T = 77 K (middle panel) p 3(t) drops to about 0.6 at t = 1 ps. On the other hand, no pronounced difference in the behaviors of p 1(t) and p 2(t) at T = 0 and 77 K is observed. In the language of spectral densities defined in Eq. 14, it means that the contributions of the lower-frequencies vibrational modes (which are strongly temperature dependent) are quite significant in the dynamics of p 3(t) already at 77 K, while are less pronounced in the dynamics of p 1(t) and p 2(t).

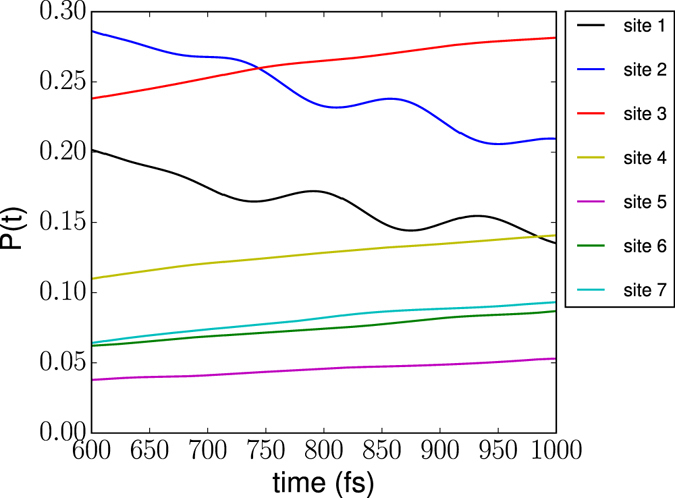

If temperature increases up to 300 K (lower panel) p 3(t) further decreases to 0.3 at t = 1 ps, and the oscillatory components of p 1(t) and p 2(t) are significantly reduced but still visible. As can be seen from Figure 3, which shows an enlargement of the lower panel of Figure 2 at longer times, small amplitude beatings of p 1(t) and p 2(t) are clearly observable even after 700 fs. Such long-lived beatings at ambient temperature have not been reported in models employing an approximate spectral density in the Drude-Lorentz form46, Ohmic form45 or Adolphs-Regner (single peak) form45. The beatings revealed in the present work at T = 300 K are due to the strongly structured spectral density and frequency-dependent coupling between the electronic subsystem and the vibrational degrees of freedom.

Figure 3.

Enlarged section of the lower panel of Fig. 2.

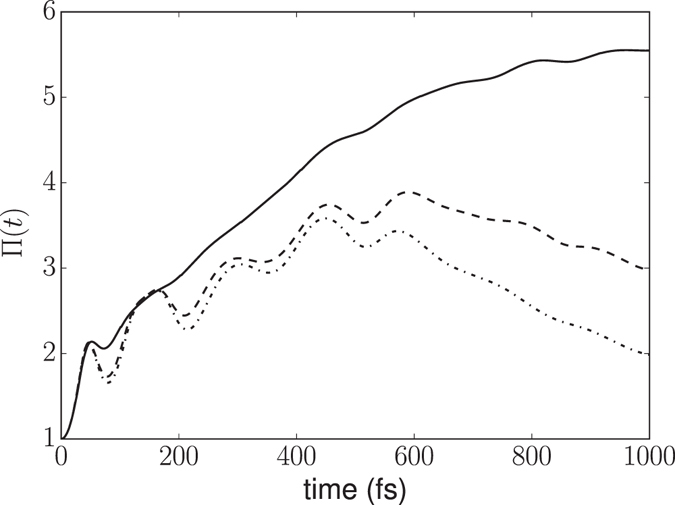

To elucidate how the spectral densities of Figure 1 affect the fraction of BChlas that are significantly occupied during the time evolution of the system, we compute the inverse participation ratio Π(t), defined as64, 65

| 15 |

It is easy to show that Π(t) = 1 for a completely localized exciton wavefunction, while Π(t) = N site (7 in the present case) for a perfectly uniform state. Therefore, Π(t) can be considered as an effective length, measuring the spatial extent of the exciton wave function over the aggregate. Figure 4 shows the computed Π(t) for the FMO complex at different temperatures. At T = 0 K Π(t) has a strong quantum behavior showing an oscillatory increase for the first 400 fs which is followed by an oscillatory decrease to a value of 2 at t = 1 ps. This is an indication of the exciton self-trapping. Therefore, a small number of sites are accessible to the systems during its evolution at T = 0 K, as is also evident from the population dynamics in Figure 2. For T = 77 K, the qualitative behavior of Π(t) remains the same but the number of accessible sites increases to 3 at t = 1 ps. At room temperature the number of accessible sites increases significantly and the effective length of the exciton is about 5.5 at t = 1 ps. The effect of a finite temperature is thus not only to provide a decoherence mechanism but also to increase the number of sites simultaneously accessible for the energy transfer process and to destroy the exciton self-trapping (cf. ref. 65).

Figure 4.

Inverse participation ratio Π(t) as a function of time; (−) 300 K, (− −) 77 K, (− ·) 0 K.

Summarizing, we have developed a new theoretical and numerical approach for the determination of time dependent properties in large molecular aggregates. The methodology is based on Thermo Field Dynamics theory and requires doubling of all the thermalised degrees of freedom. The evaluation of an observable 〈A(t)〉 is reduced to the calculation of a simpler expectation value 〈φ(t)|A θ|φ(t)〉 where |φ(t)〉 satisfies the Schrödinger equation 8. The methodology has been implemented in the framework of the Tensor Train/Matrix Product State representation of the wave function, and using a novel technique for the numerical integration of Tensor Trains based on the time-dependent variational principle59. We have successfully applied this methodology to the study of quantum dynamics of energy transfer in the FMO complex. The present results draw attention to the importance of an accurate modeling of the bath spectral density. A highly structured spectral density is required to observe long-lasting oscillations in 〈A(t)〉 at room temperature which are absent when a simple Drude-Lorentz model46 or Ohmic model45 are employed.

The methodology developed in the present work offers new qualitative insights into the dynamics of excitonic systems at finite temperatures. The time evolution of these systems is governed by the thermal Hamiltonian of Equation 12, which looks like a standard excitonic Hamiltonian H of Equation 11, but contains twice as many vibrational degrees of freedom: the physical ones and the auxiliary (tilde) ones. Hence, all nontrivial dynamic effects are governed by three sets of the parameters: the electronic couplings J nm as well as the temperature-dependent electron-vibrational couplings g kn cosh (θ k) and g kn sinh (θ k). The parameters g kn sinh (θ k) determine the coupling of the electronic degrees of freedom with the vibrational tilde degrees of freedom, and regulate the effective number of vibrational modes of the system. If T = 0 K, g kn sinh (θ k) = 0 and the tilde variables are totally decoupled. At higher temperature both g kn cosh (θ k) and g kn sinh (θ k) tend to contribute on an equal footing. Since the system dynamics is purely Hamiltonian, the time evolution of any observable 〈A(t)〉 is the result of pure dephasing of the wave packet formed by a large number of vibronic eigenstates of the Hamiltonian . All oscillatory behaviors in 〈A(t)〉 are therefore vibronic by definition, since they are caused by the combined effect of electronic and temperature-dependent electron-vibrational couplings. Hence, a proper simulation of the time evolution of excitonic systems at finite temperature requires a careful modeling of electron-phonon interaction.

Methods

Derivation of TFD Schrödinger equation

Equation 6 can be transformed into a convenient Schrödinger representation by first rewriting it as

| 16 |

where is any operator acting in the tilde vibrational space. The choice of the gauge is dictated exclusively by computational convenience and does not affect the expectation value 〈A(t)〉. Hence

| 17 |

where

| 18 |

and the modified Hamiltonian operator is defined as

| 19 |

Equation 17 is clearly equivalent to

| 20 |

where the wavefunction |φ(t)〉 satisfies the equation

| 21 |

We point out that in order to obtain a numerical solution of the Schrödinger equation 21 the Hamiltonian must have an analytical representation or a form which is suitable for numerical treatment. This can be accomplished by expanding in power series of creation-annihilation operators (or position and momentum operators) and using the fundamental relations40

| 22 |

| 23 |

The transformed Hamiltonian depends on temperature through the parameters θ k.

Quantum Dynamics with Tensor-Trains

Let us consider a generic expression of a state of a d dimensional quantum system in the form

| 24 |

where |i k〉 labels the basis states of the k-th dynamical variable, and the elements are complex numbers labeled by d indices. If we truncate the summation of each index i k the elements represent a tensor of rank d. The evaluation of the summation 24 requires the computation (and storage) of n d terms, where n is the average size of the one-dimensional basis set, which becomes prohibitive for large d. Using the TT format, the tensor C is approximated as

| 25 |

where G k(i k) is a r k−1 × r k complex matrix. In the explicit index notation

| 26 |

The matrices G k are three-dimensional arrays, called cores of the TT decomposition. The ranks r k are called compression ranks. Using the TT decomposition 25 it is possible, at least in principle, to overcome most of the difficulties caused by the dimensions of the problem. Indeed, the wave function is entirely defined by d arrays of dimensions r k−1 × n k × r k thus the required storage dimension is of the order dnr 2.

In a time-dependent theory the cores G k(i k) are time dependent complex matrices whose equations of motion can be found by applying the time-dependent variational principle (TDVP) to the parametrized form of the wave function

| 27 |

The resulting equations of motion can be written in the form

| 28 |

and provide an approximate solution of the original equation on the manifold of TT tensors of fixed rank, . In equation 28, is the orthogonal projection into the tangent space of at |Ψ(G(t))〉. We refer the reader to refs 59 and 66, where the explicit differential equations are derived and their approximation properties are analyzed, and to ref. 67 for a discussion of time-dependent TT/MPS in the theoretical physics literature.

Several techiques exist to compute the time evolution of TT/MPS59, 68–70. Here we adopt a methodology recently developed by Lubich, Oseledets and Vandereycken, which combines an explicit expression for the projector and an extremely efficient second order split projector integrator specifically tailored to the TT format59. The computations presented in this paper have been performed using a code based on the software library developed by Oseledets and coworkers.

All results presented in this paper are numerically converged in the sense that the ranks of the TT cores are increased until no significant variations are observed in the solution. The dynamics at 300 K required an average value r k = 40 to obtain fully converged results.

Acknowledgements

R.B. acknowledges the CINECA award CSDYN-HP10CTEX1Q under the ISCRA initiative, for the availability of high performance computing resources and support, and the University of Torino for the awards BORR-RILO-16-01. M.F.G. acknowledges the support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) through the DFG-Cluster of Excellence “Munich-Centre for Advanced Photonics” (www.munich-photonics.de).

Author Contributions

R.B. and M.F.G. contributed equally to the research project and wrote the main text of the manuscript. R.B. implemented the code for the quantum dynamical simulations and prepared Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Scholes GD, et al. Using coherence to enhance function in chemical and biophysical systems. Nature. 2017;543:647–656. doi: 10.1038/nature21425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engel GS, et al. Evidence for wavelike energy transfer through quantum coherence in photosynthetic systems. Nature. 2007;446:782–786. doi: 10.1038/nature05678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Reilly EJ, Olaya-Castro A. Non-classicality of the molecular vibrations assisting exciton energy transfer at room temperature. Nat. Comm. 2014;5 doi: 10.1038/ncomms4012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chin AW, et al. The role of non-equilibrium vibrational structures in electronic coherence and recoherence in pigment-protein complexes. Nature Physics. 2013;9:113–118. doi: 10.1038/nphys2515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiang L, et al. Intermediate tunnelling–hopping regime in DNA charge transport. Nature Chemistry. 2015;7:221–226. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makri N, Sim E, Makarov DE, Topaler M. Long-time quantum simulation of the primary charge separation in bacterial photosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:3926–3931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.3926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanimura Y, Kubo R. Time Evolution of a Quantum System in Contact with a Nearly Gaussian-Markoffian Noise Bath. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1989;58:101–114. doi: 10.1143/JPSJ.58.101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanimura Y. Stochastic Liouville, Langevin, Fokker–Planck, and Master Equation Approaches to Quantum Dissipative Systems. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2006;75 doi: 10.1143/JPSJ.75.082001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanimura Y. Real-time and imaginary-time quantum hierarchal Fokker-Planck equations. J. Chem. Phys. 2015;142 doi: 10.1063/1.4916647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang Z, Ouyang X, Gong Z, Wang H, Wu J. Extended hierarchy equation of motion for the spin-boson model. J. Chem. Phys. 2015;143 doi: 10.1063/1.4936924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duan H-G, Thorwart M. Quantum Mechanical Wave Packet Dynamics at a Conical Intersection with Strong Vibrational Dissipation. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016;7:382–386. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b02793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meier C, Tannor DJ. Non-Markovian evolution of the density operator in the presence of strong laser fields. J. Chem. Phys. 1999;111:3365–3376. doi: 10.1063/1.479669. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moix JM, Cao J. A hybrid stochastic hierarchy equations of motion approach to treat the low temperature dynamics of non-Markovian open quantum systems. J. Chem. Phys. 2013;139 doi: 10.1063/1.4822043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen L, Zhao Y, Tanimura Y. Dynamics of a One-Dimensional Holstein Polaron with the Hierarchical Equations of Motion Approach. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015;6:3110–3115. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b01368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishizaki A, Tanimura Y. Quantum Dynamics of System Strongly Coupled to Low-Temperature Colored Noise Bath: Reduced Hierarchy Equations Approach. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2005;74:3131–3134. doi: 10.1143/JPSJ.74.3131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Redfield, A. G. The Theory of Relaxation Processes. In Waugh, J. S. (ed.) Advances in Magnetic and Optical Resonance, vol. 1 of Advances in Magnetic Resonance, 1–32 (Academic Press, 1965).

- 17.Kühl A, Domcke W. Multilevel redfield description of the dissipative dynamics at conical intersections. J. Chem. Phys. 2002;116:263–274. doi: 10.1063/1.1423326. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Izmaylov, A. F. et al. Nonequilibrium fermi golden rule for electronic transitions through conical intersections. J. Chem. Phys. 135, 234106–234106–14 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Endicott JS, Joubert-Doriol L, Izmaylov AF. A perturbative formalism for electronic transitions through conical intersections in a fully quadratic vibronic model. J. Chem. Phys. 2014;141 doi: 10.1063/1.4887258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kubo R, Toyozawa Y. Application of the method of generating function to radiative and non-radiative transitions of a trapped electron in a crystal. Prog. Theor. Phys. 1955;13:160–182. doi: 10.1143/PTP.13.160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borrelli R, Peluso A. The temperature dependence of radiationless transition rates from ab initio computations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011;13:4420–4426. doi: 10.1039/c0cp02307h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borrelli R, Capobianco A, Peluso A. Generating function approach to the calculation of spectral band shapes of free-base chlorin including duschinsky and herzberg-teller effects. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2012;116:9934–9940. doi: 10.1021/jp307887s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borrelli R, Peluso A. Quantum Dynamics of Radiationless Electronic Transitions Including Normal Modes Displacements and Duschinsky Rotations: A Second-Order Cumulant Approach. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2015;11:415–422. doi: 10.1021/ct500966c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gelin MF, Egorova D, Domcke W. Exact quantum master equation for a molecular aggregate coupled to a harmonic bath. Phys. Rev. E. 2011;84 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.84.041139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gelin MF, Sharp LZ, Egorova D, Domcke W. Bath-induced correlations and relaxation of vibronic dimers. J. Chem. Phys. 2012;136 doi: 10.1063/1.3676063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White SR. Minimally Entangled Typical Quantum States at Finite Temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009;102:190601–190605. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.190601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeckelmann E, White SR. Density-matrix renormalization-group study of the polaron problem in the Holstein model. Phys. Rev. B. 1998;57:6376–6385. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.57.6376. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beck MH, Jackle A, Worth GA, Meyer HD. The multiconfiguration time-dependent hartree (MCTDH) method: a highly efficient algorithm for propagating wavepackets. Phys. Rep. 2000;324:1–105. doi: 10.1016/S0370-1573(99)00047-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang H, Thoss M. Multilayer formulation of the multiconfiguration time-dependent hartree theory. J. Chem. Phys. 2003;119:1289–1299. doi: 10.1063/1.1580111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burghardt I, Giri K, Worth GA. Multimode quantum dynamics using Gaussian wavepackets: The Gaussian-based multiconfiguration time-dependent Hartree (G-MCTDH) method applied to the absorption spectrum of pyrazine. J. Chem. Phys. 2008;129 doi: 10.1063/1.2996349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borrelli R, Peluso A. Quantum dynamics of electronic transitions with Gauss-Hermite wave packets. J. Chem. Phys. 2016;144 doi: 10.1063/1.4943538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borrelli, R. & Gelin, M. F. The Generalized Coherent State ansatz: Application to quantum electron-vibrational dynamics. Chem. Phys. 91–98 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Zhou N, et al. Fast, Accurate Simulation of Polaron Dynamics and Multidimensional Spectroscopy by Multiple Davydov Trial States. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2016;120:1562–1576. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.5b12483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borrelli R, Thoss M, Wang H, Domcke W. Quantum dynamics of electron-transfer reactions: photoinduced intermolecular electron transfer in a porphyrin–quinone complex. Mol. Phys. 2012;110:751–763. doi: 10.1080/00268976.2012.676211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang H, Song X, Chandler D, Miller WH. Semiclassical study of electronically nonadiabatic dynamics in the condensed-phase: Spin-boson problem with Debye spectral density. J. Chem. Phys. 1999;110:4828–4840. doi: 10.1063/1.478388. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang H, Thoss M. Theoretical Study of Ultrafast Photoinduced Electron Transfer Processes in Mixed-Valence Systems. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2003;107:2126–2136. doi: 10.1021/jp0272668. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borrelli R, Di Donato M, Peluso A. Quantum dynamics of electron transfer from bacteriochlorophyll to pheophytin in bacterial reaction centers. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2007;3:673–680. doi: 10.1021/ct6003802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang H. Multilayer Multiconfiguration Time-Dependent Hartree Theory. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2015;119:7951–7965. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.5b03256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vendrell O, Meyer H-D. Multilayer multiconfiguration time-dependent Hartree method: Implementation and applications to a Henon–Heiles Hamiltonian and to pyrazine. J. Chem. Phys. 2011;134 doi: 10.1063/1.3535541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takahashi Y, Umezawa H. Thermo field dynamics. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B. 1996;10:1755–1805. doi: 10.1142/S0217979296000817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kosov, D. S. Nonequilibrium Fock space for the electron transport problem. J. Chem. Phys. 17, 171102–171102-4 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Borrelli R, Gelin MF. Quantum electron-vibrational dynamics at finite temperature: Thermo field dynamics approach. J. Chem. Phys. 2016;145 doi: 10.1063/1.4971211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Milder MTW, Brüggemann B, van Grondelle R, Herek JL. Revisiting the optical properties of the fmo protein. Photosynth Res. 2010;104:257–274. doi: 10.1007/s11120-010-9540-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thyrhaug E, Židek K, Dostál J, Bína D, Zigmantas D. Exciton structure and energy transfer in the fenna - matthews - olson complex. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016;7:1653–1660. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b00534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nalbach P, Braun D, Thorwart M. Exciton transfer dynamics and quantumness of energy transfer in the fenna-matthews-olson complex. Phys. Rev. E. 2011;84 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.84.041926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ishizaki A, Fleming GR. Theoretical examination of quantum coherence in a photosynthetic system at physiological temperature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:17255–17260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908989106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kreisbeck C, Kramer T. Long-Lived Electronic Coherence in Dissipative Exciton Dynamics of Light-Harvesting Complexes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2012;3:2828–2833. doi: 10.1021/jz3012029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schulze J, Shibl MF, Al-Marri MJ, Kühn O. Multi-layer multi-configuration time-dependent Hartree (ML-MCTDH) approach to the correlated exciton-vibrational dynamics in the FMO complex. J. Chem. Phys. 2016;144 doi: 10.1063/1.4948563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Olbrich C, Strümpfer J, Schulten K, Kleinekathöfer U. Theory and Simulation of the Environmental Effects on FMO Electronic Transitions. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2011;2:1771–1776. doi: 10.1021/jz2007676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aghtar M, Strümpfer J, Olbrich C, Schulten K, Kleinekathöfer U. Different Types of Vibrations Interacting with Electronic Excitations in Phycoerythrin 545 and Fenna–Matthews–Olson Antenna Systems. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014;5:3131–3137. doi: 10.1021/jz501351p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wendling M, et al. Electron-Vibrational Coupling in the Fenna-Matthews-Olson Complex of Prosthecochloris aestuarii Determined by Temperature-Dependent Absorption and Fluorescence Line-Narrowing Measurements. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2000;104:5825–5831. doi: 10.1021/jp000077+. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Louisell, W. H. et al. Quantum statistical properties of radiation. Wiley series in pure and applied optics (John Wiley and Sons, 1990).

- 53.Barnett SM, Knight PL. Thermofield analysis of squeezing and statistical mixtures in quantum optics. J. Opt. Soc. Amer. B. 1985;2 doi: 10.1364/JOSAB.2.000467. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suzuki M. Density matrix formalism, double-space and thermo field dynamics in non-equilibrium dissipative systems. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B. 1991;5:1821–1842. doi: 10.1142/S0217979291000705. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arimitsu T, Umezawa H. A General Formulation of Nonequilibrium Thermo Field Dynamics. Progr. Theor. Phys. 1985;74:429–432. doi: 10.1143/PTP.74.429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Umezawa, H., Matsumoto, H. & Tachiki, M. Thermo field dynamics and condensed states (North-Holland, 1982).

- 57.Vidal G. Efficient Classical Simulation of Slightly Entangled Quantum Computations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003;91 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.91.147902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oseledets I. Tensor-Train Decomposition. SIAM J. Sci. Comp. 2011;33:2295–2317. doi: 10.1137/090752286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lubich C, Oseledets I, Vandereycken B. Time Integration of Tensor Trains. SIAM J. Num. Anal. 2015;53:917–941. doi: 10.1137/140976546. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Holtz S, Rohwedder T, Schneider R. On manifolds of tensors of fixed TT-rank. Numerische Mathematik. 2011;120:701–731. doi: 10.1007/s00211-011-0419-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moix J, Wu J, Huo P, Coker D, Cao J. Efficient Energy Transfer in Light-Harvesting Systems, III: The Influence of the Eighth Bacteriochlorophyll on the Dynamics and Efficiency in FMO. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2011;2:3045–3052. doi: 10.1021/jz201259v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kreisbeck, C., Kramer, T., Rodrguez, M. & Hein, B. High-Performance Solution of Hierarchical Equations of Motion for Studying Energy Transfer in Light-Harvesting Complexes 7, 2166–2174 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Schulze, J. & Kühn, O. Explicit Correlated Exciton-Vibrational Dynamics of the FMO Complex. J. Phys. Chem. B 6211–6216 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Meier T, Zhao Y, Chernyak V, Mukamel S. Polarons, localization, and excitonic coherence in superradiance of biological antenna complexes. J. Chem. Phys. 1997;107:3876–3893. doi: 10.1063/1.474746. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chorošajev V, Rancova O, Abramavicius D. Polaronic effects at finite temperatures in the B850 ring of the LH2 complex. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016;18:7966–7977. doi: 10.1039/C5CP06871A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lubich C, Rohwedder T, Schneider R, Vandereycken B. Dynamical Approximation by Hierarchical Tucker and Tensor-Train Tensors. SIAM J. Mat. Anal. App. 2013;34:470–494. doi: 10.1137/120885723. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Haegeman J, Osborne TJ, Verstraete F. Post-matrix product state methods: To tangent space and beyond. Phys. Rev. B. 2013;88 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.88.075133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wall ML, Carr LD. Out-of-equilibrium dynamics with matrix product states. New Journal of Physics. 2012;14 doi: 10.1088/1367-2630/14/12/125015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wall, M. L., Safavi-Naini, A. & Rey, A. M. Simulating generic spin-boson models with matrix product states. arXiv:1606.08781 [cond-mat, physics:quant-ph], ArXiv: 1606.08781 (2016).

- 70.Garca-Ripoll JJ. Time evolution of Matrix Product States. New Journal of Physics. 2006;8 doi: 10.1088/1367-2630/8/12/305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]