Abstract

Obesity is characterized as the excessive accumulation of body fat and has a complex genetic foundation in humans including monogenic high-risk mutations and polygenic contributions. Domestic pigs represent a valuable model on an obesity-promoting high-caloric diet while constantly evaluated for body characteristics. As such, we investigated the genetics of obesity-related traits, comprising subcutaneous fat thickness, lean mass percentage, and growth rate, in a pig population. We conducted genome-wide association analyses using an integrative approach of single-marker regression models and multi-marker Bayesian analyses. Thus, we identified 30 genomic regions distributed over 14 different chromosomes contributing to the variation in obesity-related traits. In these regions, we validated the association of four candidate genes that are functionally connected to the regulation of appetite, processes of adipogenesis, and extracellular matrix formation. Our findings revealed fundamental genetic factors which deserves closer attention regarding their roles in the etiology of obesity.

Introduction

Basic process involved in the development and metabolism of white adipose tissues are of high scientific importance, especially due to the impact of pathological excess of body fat mass on human health. Obesity and obesity related diseases, such as diabetes, high blood pressure and heart diseases, reach epidemic proportions worldwide with gravely consequences especially in industrialized and developing countries1.

Several hypotheses are widely discussed giving different explanations for the genetic manifestation of obesity in humans (reviewed by2). In agreement, obesity is a highly polygenic trait and heritability estimates of obesity related phenotypes (e.g. body mass index; BMI) in humans revealed a proportion of 30–70% assigned to genetics3, 4. Nevertheless, beside rare forms of obesity caused by monogenic high-risk mutations, the complex disease pattern is based on polygenic causes and suggested to be influenced by environmental factors, lifestyle, and dietary habits. Specifically, main driving factors are the permanent availability and consumption of energy dense foods combined with low levels of physical activity which potentially cause chronic imbalance between energy intake and expenditure5. Fundamental metabolic processes and accompanied genetic principles involved in the etiology of obesity related diseases are analogous in all mammalian species. Accordingly, commercial pigs represent an intact biological system on an obesity promoting high caloric diet throughout their lifetime coupled with low physical activity in the conventional production processes. Under these preconditions, pigs are highly susceptible for a disturbed fat metabolism and an obesity related phenotype but at the same time adapted to a diabetogenic environment6. However, due to the breeding structure and the continuous phenotypic evaluation of animals in terms of fat, muscle, and growth traits, basic molecular variations as well as minimal alterations in fat metabolism can be related to genetic causes. Therefore, the elucidation of the genetic architecture of traits related muscle and fat mass in these commercial pig lines provide interesting insights into major and minor factors contributing to the development of obesity related phenotypes.

Genetic studies in different mammalian species, e.g. humans, mice, and pigs, revealed a consistently large number of genes affecting fat deposition and the occurrence and dimension of obesity7–9. Specifically, major players like melanocortin 4 receptor (MC4R), leptin (LEP), and fat mass and obesity-associated gene (FTO) are known key regulators of feed intake/appetite and energy homeostasis9. As many of these factors were derived and validated by genome-wide analyses across different species, the present study aimed to identify genetic markers and genomic regions associated with fat, leanness, and growth traits in pigs. Exploiting the genetic resource of mammalian livestock species can provide positional and functional candidate genes beyond the general knowledge about the main sources for the genetic predisposition of obesity.

Results

Genome-wide association analysis of lean mass percentage (LMP)

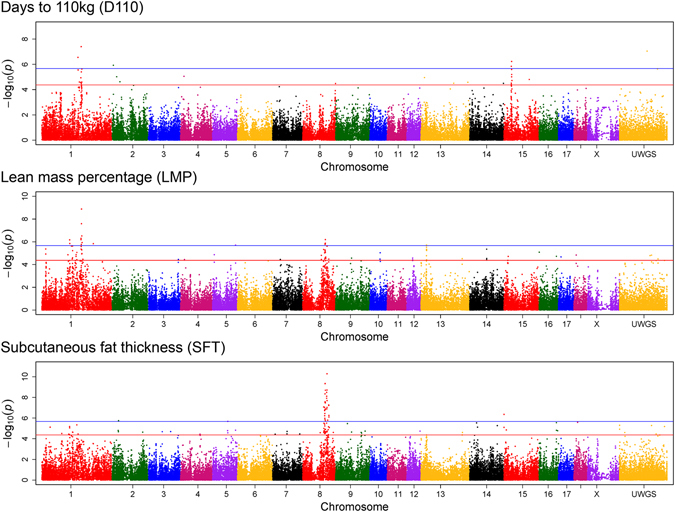

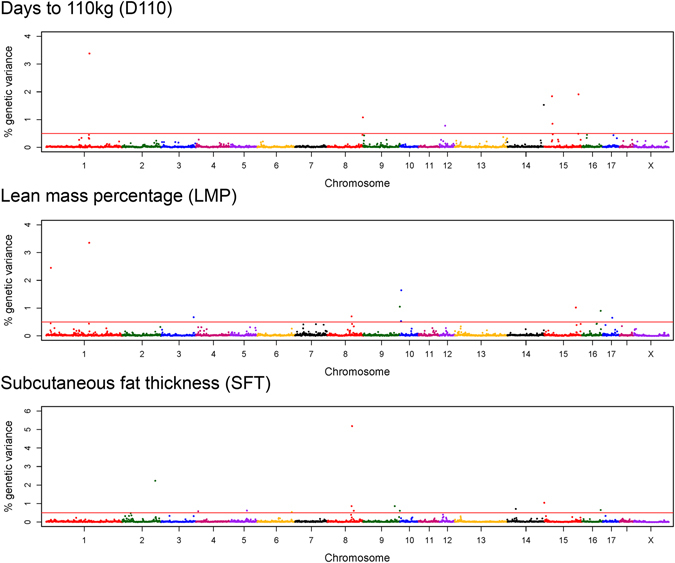

The genome-wide analyses revealed 10 genomic windows with prominent contribution to the genetic variance in LMP (Table 1). In total, genetics explained 41% of the total variance in LMP. The 1-Mb (mega base pairs) window from 178.0 to 178.9 Mb on chromosome 1 explained 0.81% of the genetic variance of the trait. Supportively, single-marker analysis pointed to a genomic region between 175.6 and 180.5 Mb on chromosome 1 including 15 significantly associated markers, of which 7 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) exceed the threshold of genome-wide significance (p < 2.1e-06) (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 2). The highest significantly associated SNP ALGA0006623 mapped next to the MC4R locus. Furthermore, a second region on chromosome 1 (19.0–20.0 Mb) explained the highest proportion of the genetic variance of LMP with 1.39% (Fig. 2). Exclusively, the uncharacterized ENSSSCG00000028974, with predicted sulfotransferase activity, is located in this 1-Mb window. A third genomic region on chromosome 1, at approximately 125 Mb, was indicated by 3 markers reaching genome-wide significance in single-marker analysis (Fig. 1). This region harbours several genomic features and significantly associated markers are linked to MYO1E (ALGA0005584), ADAM10 (ALGA0005610) and novel protein coding features (MARC0103791). Another region linked to the variation in LMP was identified between 98.6 and 104.0 Mb on chromosome 8 by single-marker analyses (Fig. 1) and was further supported by a 1-Mb window between 100.2 and 100.9 Mb (Table 1). While the whole 5 Mb spanning region harbours in total 16 genetic features, none of the genes represented a clear positional or functional candidate for LMP. Single-marker but not multi-marker analyses revealed a region on chromosome 13 from 24.8 to 25.5 Mb harboring several functional candidate genes e.g. ACAA, OXSR1, and SLC22A14 (Fig. 1). The integration of both genome-wide analysis approaches further revealed a genomic window between 77.0 and 77.9 Mb on chromosome 16 contributing to the genetic variance in LMP (0.55%). The most prominent SNP ALGA0091730 is located at 77.6 Mb next to FAT2, SLC36A1 and ENSSSCG00000017082 (predicted as SPARC).

Table 1.

Overview of genomic regions identified by integrating genome-wide single-marker (linear regression) and window-based (Bayes B) approaches for days to 110 kg (D110), lean mass percentage (LMP), and subcutaneous fat thickness (SFT).

| Trait | Chr. | Genomic window | Top SNP in single-marker analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start (Mb) | End (Mb) | Explained genetic variance (%) | Number of significant single marker | SNP | Position | p-value | Number of features in window | plausible candidate gene | ||

| D110 | 1 | 146.0 | 147.0 | 0.74 | 0 | — | — | — | 18 | GPR176 |

| 1 | 176.0 | 176.9 | 0.59 | 2 | ASGA0004976 | 176492950 | 1.6e-07 | 6 | TNFRSF11A | |

| 1 | 177.0 | 178.0 | 0.62 | 2 | H3GA0003111 | 177074934 | 1.2e-05 | 3 | — | |

| 1 | 179.0 | 180.0 | 1.8 | 1 | MARC0013872 | 179327620 | 1.1e-05 | 13 | MC4R | |

| 8 | 145.0 | 146.0 | 0.53 | 0 | — | — | — | 7 | — | |

| 8 | 146.0 | 147.0 | 0.51 | 0 | — | — | — | 10 | BMP3 | |

| 8 | 147.0 | 148.0 | 0.98 | 1 | ASGA0040607 | 147636271 | 2.9e-05 | 5 | GK2, BMP2K | |

| 12 | 23.0 | 24.0 | 0.65 | 0 | — | — | — | 28 | — | |

| 14 | 151.0 | 152.0 | 1.5 | 1 | M1GA0019945 | 151444665 | 3.7e-05 | 3 | - | |

| 15 | 32.0 | 32.9 | 1.38 | 2 | ALGA0084616 | 32933373 | 3.8e-06 | 0 | — | |

| 15 | 142.0 | 143.0 | 1.57 | 0 | — | — | — | 11 | RHBDD1 | |

| LMP | 1 | 19.0 | 20.0 | 1.39 | 0 | — | — | — | 2 | ENSSSCG00000028974 (UST) |

| 1 | 178.0 | 178.9 | 0.81 | 1 | ALGA0006623 | 178024855 | 1.1e-09 | 2 | MC4R at 178.5 Mb | |

| 3 | 134.0 | 134.8 | 0.57 | 1 | ALGA0021640 | 134815777 | 3.5e-05 | 9 | ATP6V1C2 | |

| 7 | 118.0 | 119.0 | 0.51 | 0 | — | — | — | 7 | CALM1 | |

| 8 | 100.2 | 100.9 | 0.52 | 6 | ASGA0039385 | 100921095 | 1.9e-06 | 0 | — | |

| 9 | 152.1 | 153.0 | 0.69 | 0 | — | — | — | 0 | — | |

| 10 | 4.0 | 4.9 | 0.56 | 0 | — | — | — | 1 | — | |

| 10 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 0.98 | 0 | — | — | — | 1 | BRINP3 | |

| 15 | 131.0 | 132.0 | 0.84 | 0 | — | — | — | 8 | PECR | |

| 16 | 77.0 | 77.9 | 0.55 | 1 | ALGA0091730 | 77611594 | 1.5e-05 | 8 | ENSSSCG00000017082 (SPARC) | |

| SFT | 2 | 137.0 | 138.0 | 2.12 | 1 | ALGA0016010 | 137184334 | 2.6e-05 | 9 | SLC27A6 |

| 4 | 9.0 | 9.9 | 0.5 | 0 | — | — | — | 5 | — | |

| 5 | 68.0 | 69.0 | 0.6 | 2 | MARC0036560 | 68326348 | 1.6e-06 | 10 | CCND2 | |

| 6 | 143.0 | 144.0 | 0.6 | 0 | — | — | — | 6 | PRKAA2 | |

| 8 | 100.2 | 100.9 | 0.7 | 9 | CASI0009346 | 100889708 | 6.6e-10 | 0 | — | |

| 8 | 102.0 | 102.9 | 5.36 | 7 | ALGA0048723 | 102070107 | 2.4e-09 | 3 | — | |

| 8 | 109.1 | 109.8 | 0.5 | 6 | ALGA0122904 | 109553065 | 6.8e-11 | 8 | TRPC3, BBS7 | |

| 9 | 131.1 | 132.0 | 1.0 | 1 | ALGA0054936 | 131303382 | 3.0e-05 | 4 | — | |

| 9 | 152.1 | 153.0 | 0.5 | 0 | — | — | — | 0 | — | |

| 14 | 35.0 | 36.0 | 0.7 | 1 | DRGA0013774 | 35264755 | 8.3e-06 | 6 | ENSSSCG00000009839 (CIT) | |

| 15 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.03 | 2 | ALGA0083738 | 259597 | 5.9e-07 | 3 | TNFAIP6 | |

| 16 | 77.0 | 77.9 | 0.6 | 2 | ALGA0091730 | 77611594 | 2.5e-06 | 8 | ENSSSCG00000017082 (SPARC) | |

Figure 1.

Manhattan plots of genome-wide association analysis results for traits related to body fat mass using a single marker (mixed linear model) approach. Chromosome ‘UWGS’ represents a contig of unmapped markers. The threshold for suggestive and genome-wide significance was set to p = 4.3e-05 (equals to -log10(p-value) = 4.37) and p = 2.1e-06 (equals to -log10(p-value) = 5.67), respectively.

Figure 2.

Manhattan plots depicting the proportion of 1 Mb genomic windows to the genetic variance of analysed traits obtained from a Bayesian multi-marker approach (Bayes B). The threshold line represents contributions to the additive genetic variance of traits above 0.5%.

Genomic regions associated with subcutaneous fat thickness (SFT)

The estimated proportion of genetics to the total variance of SFT was 39.4%. In total, 12 1-Mb windows with contributions to the genetic variance above 0.5% were identified (Table 1). Three of these regions, on chromosome 8, 9, and 16, completely or partially overlap with regions linked to LMP. For the region on chromosome 8, results from single-marker analysis showed 59 significantly associated SNPs mapping in a 25 Mb spanning region between 94.4 and 119.8 Mb, of which 35 SNPs reached genome-wide significance (Fig. 1). The genomic window between 102.0 and 102.9 Mb explained the highest proportion of the genetic variance of SFT with 5.36% (Fig. 2). Based on the highest significantly associated SNP ALGA0122904, TRPC3 and BBS7 located at approximately 109.4 Mb were proposed as positional and functional candidate genes.

The 1-Mb genomic window on chromosome 16 showed a contribution of 0.6% to the genetic variance in SFT. The highest significantly associated marker obtained from single-marker analysis in this region mapped next to ENSSSCG00000017082 which is predicted as SPARC precursor. The second highest contribution to the genetic variance (2.12%; Fig. 2) in SFT was explained by a region between 137.0 and 138.0 Mb on chromosome 2. The most prominent single marker ALGA0016010 in this region mapped in an intergenic region between SLC27A6 and ISOC1.

Furthermore, the results from single-marker analysis provide clues for at least two additional associated regions located at the proximal end of chromosomes 2 and 15 (Fig. 1). The region between 0.0 and 1.0 Mb on chromosome 15 was further supported by a 1-Mb window and pointed to TNFAIP6 as positional candidate feature. The region on chromosome 2 was indicated by 3 significantly associated SNPs spanning the genomic region from 27.1 to 28.9 Mb. Specifically, the most prominent marker MARC0063133 mapped in an intronic region of the catalase encoding gene CAT.

Genomic regions contributing to the variation in growth rate (D110)

For D110, genetic factors explained 42.2% of the total variance. Eleven 1-Mb genomic windows on 5 different chromosomes were identified (Table 1). Thereby, the highest proportion to the genetic variance of the trait was explained by a region between 179.0 and 180.0 Mb on chromosome 1 (Table 1). Additionally, 8 SNPs mapping between 174.9 and 179.4 Mb on chromosome 1 showed evidence for significant association with growth rate (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 2). The highest significantly associated SNP ASGA0004992 mapped in an intergenic region between CDH20 and MC4R. Thus, the associated region largely overlaps with results for LMP. The integration of both GWAS approaches further revealed a genomic region located on chromosome 15 as associated with D110 (Table 1, Fig. 1). In total, 6 SNPs showed significant associations with growth rate in the region between 32.4 and 34.7 Mb. The DNA segment around 34.3 Mb, in which most significantly associated SNPs are located, harbors two annotated genes, TSN and NIFK. A third region linked to D110 mapped between 147.0 and 148.0 Mb on chromosome 8. The window contributes 0.98% to the genetic variance of D110 and the highest significantly associated SNP ASGA0040607 is located between GK2 and PAQR3. This region was further supported by two adjacent 1-Mb windows (145.0–147.0 Mb), each contributing above 0.5% to the genetic variance.

Associations of selected candidate genes with obesity-related traits

Association analyses of SNPs located in SLC27A6, SPARC, BBS7, and MC4R were carried out in a representative subset of the analysed population (Table 2). For SLC27A6, SPARC, and BBS7 significant associations with fat thickness and lean mass but not with growth rates were demonstrated. Highest significant associations were found between SFT and tagging SNPs of SPARC and BBS7, respectively. For both genes, the homozygous carriers of the rare allele (TT for SPARC and GG for BBS7) showed significant (p < 0.05) higher SFT. Specifically, compared to carriers of the major allele these individuals showed 13% and 9% higher levels of subcutaneous fat for SPARC and BBS7, respectively. Moreover, the observed effects of these two tagging SNPs on LMP were in the opposite direction with a similar order of magnitude. Association analyses of the genotyped MC4R polymorphism revealed significant associations with LMP but not with SFT. Moreover, the tagging SNP in MC4R showed a tendency for affecting growth rates, with carriers of the minor G-allele growing slower but having higher LMP.

Table 2.

Association of selected candidate gene polymorphisms with days to 110 kg (D110), lean mass percentage (LMP), and subcutaneous fat thickness (SFT).

| SNP | Trait | P-value | Least square means ± standard error (n)1 | MAF2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLC27A6 | CC | CT | TT | ||||||

| SFT | 0.0486 | 8.47a ± 0.21 | (42) | 8.31a ± 0.10 | (187) | 7.97b ± 0.12 | (127) | 0.38 | |

| LMP | 0.0323 | 61.85ab ± 0.28 | (42) | 61.83a ± 0.18 | (187) | 62.32b ± 0.21 | (127) | ||

| D110 | 0.8097 | 138.02 ± 1.15 | (42) | 137.36 ± 0.89 | (187) | 137.43 ± 0.96 | (127) | ||

| SPARC | CC | CT | TT | ||||||

| SFT | 4.8E-05 | 7.95a ± 0.09 | (214) | 8.70b ± 0.16 | (74) | 8.98b ± 0.38 | (13) | 0.16 | |

| LMP | 0.0005 | 62.23a ± 0.17 | (214) | 61.43b ± 0.23 | (74) | 61.23b ± 0.47 | (13) | ||

| D110 | 0.2858 | 136.69 ± 0.64 | (214) | 135.46 ± 0.85 | (74) | 136.38 ± 1.65 | (13) | ||

| MC4R | GG | GA | AA | ||||||

| SFT | 0.3601 | 8.00 ± 0.20 | (51) | 8.17 ± 0.11 | (179) | 8.33 ± 0.13 | (124) | 0.40 | |

| LMP | 0.0011 | 62.71a ± 0.25 | (51) | 62.08b ± 0.15 | (179) | 61.68c ± 0.17 | (124) | ||

| D110 | 0.0521 | 138.23a ± 0.87 | (51) | 136.81ab ± 0.55 | (179) | 135.97b ± 0.63 | (124) | ||

| BBS7 | GG | GA | AA | ||||||

| SFT | 2.1E-05 | 8.55 ± 0.22 | (42) | 8.55 ± 0.13 | (152) | 7.82 ± 0.13 | (145) | 0.35 | |

| LMP | 0.0039 | 61.73 ± 0.29 | (42) | 61.73 ± 0.20 | (152) | 62.36 ± 0.21 | (145) | ||

| D110 | 0.5066 | 138.16 ± 1.15 | (42) | 137.18 ± 0.89 | (152) | 136.97 ± 0.90 | (145) | ||

1Least square means for genotypes were compared by t-test and P-values were adjusted by Tukey-Kramer correction. Superscripts a,b,c indicate for significant differences at P < 0.05. Significant associations (P < 0.05) are highlighted in bold. 2Minor allele frequency.

Discussion

The current study elucidated the genetics of fat and muscle deposition in a pig population with a long-term breeding history of selection for leanness, growth and feed efficiency. Thus, it aims at the cross-species identification of genetic factors and genomic regions contributing to the genetic predisposition for an excess of body fat mass. Bayesian multi-marker approaches, which were shown to be beneficial to identify trait-associated genomic regions10, were applied to the dataset. Results were integrated with single-marker analyses which further provide supportive evidence for the association of complex traits and allelic variants11, 12. In total, the genome-wide scan for DNA segments influencing fat, muscle, and growth traits revealed 30 unique 1-Mb genomic windows located on 14 different chromosomes. Proposed candidate genes are involved in the mediation of processes related to extracellular matrix formation, fatty acid transport, carbohydrate metabolism, homeostasis, bone metabolism, and melanocortin system. As such, the analyses provide a major resource of prominent genomic regions and derived genetic factors with specialized functions in the context of fat metabolism and, moreover, with an array of complex contributions to the etiology of obesity-related diseases.

The results partially overlap with genetic factors previously reported in human and mouse studies dealing with the genetics of obesity (reviewed by7). In fact, the MC4R locus represents one of the major obesity-associated loci in humans13, 14 and is linked to fatness, growth, and efficiency traits in pigs15. However, the genotyping of the MC4R rs81219178 polymorphism in the current dataset and subsequent association analyses did not fully represent the highly significant associations obtained from the genome-wide analyses with LMP and D110. Other studies argue for at least a second genetic factor in this genomic region that influences fat deposition and/or muscle development as supported by conditional analysis including MC4R genotype information in pigs16. Moreover, for the human homologous gene, which is located on human chromosome 18, more than 130 mutations are described in the context of monogenic and polygenic obesity17. Depending on the localisation of the MC4R mutation, both response level and direction of effects on BMI vary, thus, arguing for a complex genomic structure of the MC4R locus with protective18 or causative19 implications in the context of obesity. Interestingly, in the current study, no significant associations between the MC4R rs81219178 polymorphism and STF were found. In agreement, MC4R genotypes observed in a long-term study in humans were shown to predominantly affect the level of weight traits, due to the regulation of appetite and food consumption, with more or less strong side and secondary effects on fat deposition20. However, although the MC4R locus has been intensively investigated in human and pigs for decades, the obtained results and the ambiguous situation in humans still argue for the careful dissection of the effects in this wide quantitative trait region. This is supported by several genome-wide analyses in humans consistently assigning variations in the MC4R locus to obesity-related traits21, 22 but having difficulties to clearly narrow down the molecular causes even in large meta-analyses.

The region on chromosome 8 that showed the highest contribution to the genetic variance of SFT harbours the BBS7 gene, which is involved in the occurrence of the Bardet-Biedl Syndrome (BBS). Bardet-Biedl Syndrome is a developmental disorder which is independently caused by different genes and is characterised by diverse features including obesity23, 24. Specifically, BBS7 plays a critical role in the assembly of BBS proteins to the BBSome complex. Beside obesity, molecular alterations of BBS7 are shown to be associated with secondary clinical features like developmental delay and hypertension25. Moreover, associations of BBS7 mutations and obesity were consistently observed in different population groups, as exemplified by analyses of a Russian26 and a Korean cohort27. Knock-out studies of genes that are involved in the pathophysiology of BBS, for instance BBS7, were shown to promote the obese phenotype due to altered feed intake and weight gain28, 29. Furthermore, recent findings argue for an impaired trafficking of the leptin receptor due to alterations in the BBSome30. With regards to the significant associations between the BBS7 locus and fat thickness and leanness in pigs, this locus provides an interesting candidate not only for monogenic causes of obesity but also for its contribution to the polygenic implications on obesity rate.

The examined SLC27A6 locus, also known as FTP6, coded for a fatty acid transporter which predominantly acts on the transport of palmitate and linoleate in the plasma membrane of heart cells31. Nevertheless, SLC27A6 is also expressed in skeletal muscle32 and adipose tissue33. Evidence for an association of this locus with weight gain was previously obtained by genome-wide analyses in pigs34. Genetic variations in the porcine SLC26A6 gene are related to divergent lipid metabolism processes35. Although little is known about the role of SLC26A6 in the context of obesity, members of the fatty acid transport proteins are widely discussed as regulators of energy homeostasis, exogenous fatty acid uptake, and thermogenesis36.

The combined analyses further provided first evidence for an association of genetic variants of SPARC (ENSSSCG00000017082) with fat deposition. SPARC, also known as osteonectin, is highly conserved across species and the human homologous gene mapped on chromosome 5 at 151.6 Mb. In white adipose tissues, SPARC is known to be mainly located in the extracellular matrix (ECM). As such, SPARC is involved in the regulation of metabolic processes during adipogenesis and participates in the stabilisation of ECM structures through regulating the expression and modification of collagen37, 38. Beside the knowledge gap regarding genetic-based alterations of SPARC, the gene is well characterised in the background of obesity. Analyses in mouse models revealed a role of different SPARC isoforms in the systemic mobilization and migration of adipose stem cells and established interactions between SPARC expression and obesity related phenotypes39, 40. Furthermore, based on correlations between osteonectin plasma concentrations, SPARC expression and BMI, these connections were also validated in humans41, 42. On the functional level, osteonectin inhibits the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells and preadipocytes into adipocytes and induce the production of osteoblasts by stimulating osteoblastogenesis37. Accordingly, SPARC-null mice showed no difference in weight traits but excessive accumulation of white adipose tissue due to increased size and number of adipose cells43. Phenotypic observations further revealed impaired infarct healing and collagen formation after myocardial infarction in SPARC-null mice indicating multi-dimensional functions of SPARC in adipose tissue organisation and cardio-vascular system44. Moreover, osteonectin represents a substantial proportion of non-collagenous proteins in mineralized tissues and is involved in bone calcification, collagen I deposition, fibrillogenesis, and bone turnover45. Interestingly, total lean mass was previously mentioned as predictor for bone mineral density46 and, thus, the current associations between SPARC and LMP provide evidence for a genetic link between SPARC mutations and altered bone metabolism. Consequently, in the context of recently discussed connections between osteoporosis and obesity47, 48, SPARC could act as an important mediator in the balance of adipogenesis and osteogenesis49.

The presented list of candidate genes and their functional contribution to the etiology of obesity highlighted the usability of genome-wide analysis as a valuable tool to elucidate the genetic architecture of complex traits across species. Nevertheless, the power of the approach is influenced by many factors such as population structure, confounding variables, and the informative value of analysed traits. With respect to these factors, animal models provide several advantages50.

Although the analysed pigs were not classified as having an obese phenotype, LMP and SFT varied considerably within the population enabling to identify genetic drivers for differences of body fat mass. Moreover, the analysed traits are more suitable compared to indirect measures like BMI to distinguish between genetic factors of fat or lean mass development51. Accordingly, the performed association analyses assigned alterations of leanness to the MC4R locus while less pronounced effects were observed for the association with fat thickness. Another advantage of translational studies in model organisms is the environmental stability within the population including homogeneous feeding regimes and the absence of confounding factors such as smoking and alcohol consumption. Moreover, the polygenic inheritance of obesity is suggested to be less complex in pigs due to the on-going selection based on body characteristics and subsequent fixation of loci8, 51. Consequently, there is less genetic heterogeneity which provides the possibility to uncover particular pathways and genetic factors contributing to the predisposition of obesity. The conducted genome-wide analyses of obesity-related traits in pigs revealed prominent genetic factors like MC4R and BBS7 with known contributions to monogenic and polygenic causes in the etiology of obesity. The analyses provided a list of so far unknown and/or not examined candidate genes spotlighting pathways related to bone metabolism, extracellular matrix formation, and fatty acid transport. Genome-wide studies in livestock species provide supporting evidence for candidates discussed in humans and mouse and shed light into putative genetic factors with contribution to the polygenic cause of obesity. In particular, SPARC, as an interesting candidate gene involved in the bone-adipose axis, deserves further investigation with particular focus on human gene polymorphisms affecting obesity rate.

Materials and Methods

Data and phenotyping

All procedures described in this experiment were conducted under experimental licence from the Irish Department of Health in accordance with the Cruelty to Animals Act 1876 and the 1994 European Communities Regulations (Amendments of the Cruelty to Animals Act 1876). Data of boars of the Maxgro sire line recorded between 2006 and 2012 were provided by Hermitage Genetics (Kilkenny, Ireland). Animals have been grouped in standard commercial fully slatted pens which were mechanically ventilated to provide an ambient temperature of 18 °C with ad libitum access to feed and water. Diets had a net energy of 9.90 MJ/kg with 16.5% protein, 3.2% oil, 3.6% fibre and 4.8% ash as previously described52. Prior to the end of the feeding trial (at approximately 110 kg), subcutaneous fat thickness (SFT) and percent lean, as indicator for lean mass percentage (LMP), were measured between the 3rd and 4th last rib, 5 cm and 7 cm from the midline using a Piglog 105 ultrasonic device (Carometec A/S, Denmark). Individual growth rates were expressed as the number of days necessary to gain a final body weight of 110 kg (D110) and recoded for each animal. Descriptive statistics of the traits are presented in Table 3. Blood samples were taken from the Vena jugularis in EDTA containing tubes.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of analysed obesity-related traits in a commercial pig population.

| Traits (unit) | Abbreviation | N | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days to 110 kg (d) | D110 | 861 | 138.99 | 5.93 | 124 | 167 |

| Lean mass percentage (%) | LMP | 861 | 62.08 | 1.55 | 56.3 | 66.3 |

| Subcutaneous fat thickness (mm) | SFT | 860 | 8.20 | 1.19 | 4.7 | 13.9 |

Genotyping

Blood samples were used to extract DNA employing the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). In total, 951 individuals were genotyped using porcine SNP60 Beadchips (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Eleven samples were excluded from analyses due to sample call rates <0.97. In total, 861 individuals with complete phenotypic data were used. After filtering, 52920 SNPs were used for downstream processing. Applied criteria to retain SNP markers in analyses were: call frequencies ≥0.95, and minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥0.03. Imputation of missing genotypes was performed using fastPHASE (v1.2) to close gaps in the genotype matrix53. Marker genotype information was subsequently merged with the latest version of the Sus scrofa build 10.2 available at http://www.animalgenome.org/repository/pig/ (2014-07-07). The map file contains markers mapping to all 18 porcine autosomes, both sex chromosomes and a contig of unmapped markers combined as chromosome ‘UWGS’, resulting in 51661 annotated SNPs used for downstream analyses.

Association Analyses

Genome-wide single-marker analyses

Mixed linear models implemented in JMP genomics 6 (SAS Institute, Cary, USA) were employed for multiple single-SNP-trait association analyses. The models included random effects of dam subline and sire subline to account for relatedness between individuals. To account for age related differences, linear models of SFT and LMP included growth rate as covariate. Regarding the setting of significance thresholds, the simpleM R script was used to estimate the number of independent tests54. Based on 23496 independent test (with the principal components accounting for 99.5% of the variance), thresholds were set to p = 4.3e-05 (1/23496) for suggestive significance and p = 2.1e-06 (0.05/23496) for genome-wide significance. Results were depicted as Manhattan plot using the qqman R package55.

Genome-wide multi-marker analyses

All multi-marker analyses were performed using a Bayesian approach implemented in the web-based GenSel software (version 4.73 R)56. Parameters were set to a chain length of 51000 iterations including 1000 cycles as burn-in phase, and an output was created at 50 iteration intervals. The π-value, representing the number of SNPs considered as having no effects, was set to 0.995 as previously described for pigs57. Thus, approximately 260 SNPs were reported in a single iteration of the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chain. Variance components were estimated using initial Bayes C analyses implemented in GenSel. Taking the estimated residual and genetic variance into account, the multi-marker approach was applied to the dataset employing a Bayes B algorithm. Values of growth rates were included as covariate in the analyses of SFT and LMP. Subsequently, the individual marker results were combined to estimate the contribution of non-overlapping 1-Mb windows to the genetic variance of the three analysed traits. In total, 2577 1-Mb windows were considered (excluding linkage group ‘UWGS’) resulting in a theoretical proportion to the genetic variance of a single window of about 0.04% (100%/2577). Windows that explain more than 0.5% of the genetic variance of a trait were considered in downstream investigations.

Candidate gene selection and validation

Based on the integration of both genome-wide approaches, positional candidate genes were obtained using the porcine genome resource (Ensemble pig genome release 84, http://www.ensembl.org/Sus_scrofa). Moreover, corresponding genomic regions were screened for functional candidate genes using the information of the GeneCards database (http://www.genecards.org/). For promising positional and functional candidate genes, polymorphisms (tagging SNPs) were identified by sanger-sequencing of phenotypic-divergent individuals or by using the SNP database (dbSNP, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/). Subsequently, DNA-based tools for genotyping polymorphisms of Solute Carrier Family 27 Member 6 (SLC27A6; rs342478551), Secreted Protein Acidic And Cysteine Rich (SPARC; rs319770026), and Bardet-Biedl Syndrome 7 (BBS7; rs320343985) were developed based on restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) assays. Moreover, the MC4R polymorphism rs81219178, previously suggested to be causal for effects on fat deposition traits in pigs15, was analysed. In brief, RFLP assays were carried out in a standard PCR mix with SupraTherm Taq Polymerase (Genecraft, Lüdinghausen, Germany) according to manufactor’s specifications. Used primer pairs and restriction enzymes (all New England Biolabs, Frankfurt, Germany) are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Restriction fragments were separated on 2% agarose gel and analysed. Association analyses were performed for a representative subset of the population (n = 356) using SAS (MIXED procedure; SAS Institute). Models included dam subline and sire subline as random effects. Additionally, for the analyses of SFT and LMP, age was considered as a covariate.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Hannelore Tychsen, Angela Garve, and Janine Wetzel for their excellent technical help. This work was part of the ECO-FCE project which has received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development and demonstration.

Author Contributions

K.W. designed and supervised the study. P.V. provided the animals and participated in data collection. K.W. and H.R. performed the experiment. H.R., E.M., and S.P. analyzed the data. H.R. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-08961-4

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Fact sheet: Obesity and Overweight. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/. Accessed June 2016.

- 2.Walley AJ, Asher JE, Froguel P. The genetic contribution to non-syndromic human obesity. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:431–442. doi: 10.1038/nrg2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allison DB, et al. The heritability of body mass index among an international sample of monozygotic twins reared apart. Int. J. Obesity. 1996;20:501–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang J, et al. Genetic variance estimation with imputed variants finds negligible missing heritability for human height and body mass index. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:1114–1120. doi: 10.1038/ng.3390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogden, C. L., Kit, B. K., Fakhouri, T. H. I., Carroll, M. D. & Flegal, K. M. In GI Epidemiology 394–404 (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2014).

- 6.Gerstein HC, Waltman L. Why don’t pigs get diabetes? Explanations for variations in diabetes susceptibility in human populations living in a diabetogenic environment. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2006;174:25–26. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yazdi FT, Clee SM, Meyre D. Obesity genetics in mouse and human: back and forth, and back again. PeerJ. 2015;3 doi: 10.7717/peerj.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Switonski M, Stachowiak M, Cieslak J, Bartz M, Grzes M. Genetics of fat tissue accumulation in pigs: a comparative approach. J. Appl. Genet. 2010;51:153–168. doi: 10.1007/BF03195724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der K, Agatha A, Farooqi IS. The Hunger Genes: Pathways to Obesity. Cell. 2015;161:119–132. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Maturana EL, et al. Next generation modeling in GWAS: comparing different genetic architectures. Hum. Genet. 2014;133:1235–1253. doi: 10.1007/s00439-014-1461-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reyer H, Hawken R, Murani E, Ponsuksili S, Wimmers K. The genetics of feed conversion efficiency traits in a commercial broiler line. Sci. Rep. 2015;5 doi: 10.1038/srep16387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Onteru SK, et al. Whole Genome Association Studies of Residual Feed Intake and Related Traits in the Pig. PLoS ONE. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeo GS, et al. A frameshift mutation in MC4R associated with dominantly inherited human obesity. Nat. Genet. 1998;20:111–112. doi: 10.1038/2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaisse C, Clement K, Guy-Grand B, Froguel P. A frameshift mutation in human MC4R is associated with a dominant form of obesity. Nat. Genet. 1998;20:113–114. doi: 10.1038/2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim KS, Larsen N, Short T, Plastow G, Rothschild MF. A missense variant of the porcine melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) gene is associated with fatuation of the porcine melanocortin 4 receptor (MC4R) gene as a positional candidate for a fatness QTL in a cross between Landrace and Hampshire. Anim. Genet. 2006;37:359–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2006.01488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruun C, Jørgensen CB, Nielsen VH, Andersson L, Fredholm M. Evaluation of the porcine melanocortin 4 receptor (MC4R) gene as a positional candidate for a fatness QTL in a cross between Landrace and Hampshire. Anim. Genet. 2006;37:359–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2006.01488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hebebrand J, Volckmar A-L, Knoll N, Hinney A. Chipping away the ‘missing heritability’: GIANT steps forward in the molecular elucidation of obesity–but still lots to go. Obes Facts. 2010;3:294–303. doi: 10.1159/000321537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stutzmann F, et al. Non-synonymous polymorphisms in melanocortin-4 receptor protect against obesity: the two facets of a Janus obesity gene. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007;16:1837–1844. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farooqi IS, et al. Clinical spectrum of obesity and mutations in the melanocortin 4 receptor gene. New Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1085–1095. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang JH, et al. Characterization of a Novel Gain of Function Glucocorticoid Receptor Knock-in Mouse. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:6249–6259. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807997200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loos RJ, et al. Common variants near MC4R are associated with fat mass, weight and risk of obesity. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:768–775. doi: 10.1038/ng.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyre D, et al. Genome-wide association study for early-onset and morbid adult obesity identifies three new risk loci in European populations. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:157–159. doi: 10.1038/ng.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sattar S, Gleeson JG. The ciliopathies in neuronal development: a clinical approach to investigation of Joubert syndrome and Joubert syndrome‐related disorders. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2011;53:793–798. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.04021.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Croft JB, Morrell D, Chase CL, Swift M. Obesity in heterozygous carriers of the gene for the Bardet‐Biedl syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1995;55:12–15. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320550105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan, S. A. et al. Genetics of human Bardet–Biedl syndrome, an updates. Clin. Genet. (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Suspitsin EN, et al. Exome sequencing of a family with Bardet-Biedl syndrome identifies the common Russian mutation c. 1967_1968delTAinsC in BBS7. Mol Syndromol. 2015;6:96–98. doi: 10.1159/000371408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin SJ, et al. Identification of compound heterozygous mutations in the BBS7 Gene in a Korean family with Bardet-Biedl Syndrome. Ann. Lab. Med. 2015;35:181–184. doi: 10.3343/alm.2015.35.1.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Q, et al. BBS7 is required for BBSome formation and its absence in mice results in Bardet-Biedl syndrome phenotypes and selective abnormalities in membrane protein trafficking. J. Cell Sci. 2013;126:2372–2380. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mykytyn K, et al. Bardet–Biedl syndrome type 4 (BBS4)-null mice implicate Bbs4 in flagella formation but not global cilia assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:8664–8669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402354101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo D-F, et al. The BBSome Controls Energy Homeostasis by Mediating the Transport of the Leptin Receptor to the Plasma Membrane. PLoS Genet. 2016;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gimeno RE, et al. Characterization of a heart-specific fatty acid transport protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:16039–16044. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211412200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jain SS, et al. Additive effects of insulin and muscle contraction on fatty acid transport and fatty acid transporters, FAT/CD36, FABPpm, FATP1, 4 and 6. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:2294–2300. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ellis JM, Bowman CE, Wolfgang MJ. Metabolic and Tissue-Specific Regulation of Acyl-CoA Metabolism. PLoS ONE. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fontanesi L, Schiavo G, Galimberti G, Calo D, Russo V. A genomewide association study for average daily gain in Italian Large White pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2014;92:1385–1394. doi: 10.2527/jas.2013-7059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Molnár J, et al. Genome sequencing and analysis of Mangalica, a fatty local pig of Hungary. BMC Genomics. 2014;15 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Black PN, Ahowesso C, Montefusco D, Saini N, DiRusso CC. Fatty acid transport proteins: targeting FATP2 as a gatekeeper involved in the transport of exogenous fatty acids. MedChemComm. 2016;7:612–622. doi: 10.1039/C6MD00043F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nie J, Sage EH. SPARC functions as an inhibitor of adipogenesis. J Cell Commun Signal. 2009;3:247–254. doi: 10.1007/s12079-009-0064-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bradshaw AD. The role of SPARC in extracellular matrix assembly. J Cell Commun Signal. 2009;3:239–246. doi: 10.1007/s12079-009-0062-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tseng C, Kolonin MG. Proteolytic Isoforms of SPARC Induce Adipose Stromal Cell Mobilization in Obesity. Stem Cells. 2016;34:174–190. doi: 10.1002/stem.2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tartare-Deckert S, Chavey C, Monthouel M-N, Gautier N, Van Obberghen E. The matricellular protein SPARC/osteonectin as a newly identified factor up-regulated in obesity. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:22231–22237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010634200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takahashi M, et al. The Expression of SPARC in Adipose Tissue and Its Increased Plasma Concentration in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. Obesity Res. 2001;9:388–393. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gomez-Ambrosi J, et al. Plasma osteopontin levels and expression in adipose tissue are increased in obesity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007;92:3719–3727. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bradshaw A, Graves D, Motamed K, Sage E. SPARC-null mice exhibit increased adiposity without significant differences in overall body weight. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:6045–6050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1030790100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schellings MWM, et al. Absence of SPARC results in increased cardiac rupture and dysfunction after acute myocardial infarction. J Exp Med. 2009;206:113–123. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosset EM, Bradshaw AD. SPARC/osteonectin in mineralized tissue. Matrix Biol. 2016;52:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xiao W, et al. ALOX12 polymorphisms are associated with fat mass but not peak bone mineral density in Chinese nuclear families. Int. J. Obesity. 2011;35:378–386. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Søgaard AJ, et al. Abdominal obesity increases the risk of hip fracture. A population‐based study of 43 000 women and men aged 60–79 years followed for 8 years. Cohort of Norway. J. Intern. Med. 2015;277:306–317. doi: 10.1111/joim.12230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Greco, E. A., Donini, L. M., Lenzi, A. & Migliaccio, S. In Multidisciplinary Approach to Obesity 83–88 (Springer, 2015).

- 49.Blogowski, W., Dolegowska, K., Deskur, A., Dolegowska, B. & Starzyńska, T. An Attempt to Evaluate Selected Aspects of “Bone–Fat Axis” Function in Healthy Individuals and Patients With Pancreatic Cancer. Medicine (Baltimore)94 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Kogelman, L. J. & Kadarmideen, H. N. In Systems Biology in Animal Production and Health, Vol. 1 25–42 (Springer, 2016).

- 51.Rocha D, Plastow G. Commercial pigs: an untapped resource for human obesity research? Drug Discov. Today. 2006;11:475–477. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reyer, H. et al. Exploring the genetics of feed efficiency and feeding behaviour traits in a pig line highly selected for performance characteristics. Molecular Genetics and Genomics 1–11 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Scheet P, Stephens M. A fast and flexible statistical model for large-scale population genotype data: applications to inferring missing genotypes and haplotypic phase. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;78:629–644. doi: 10.1086/502802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gao X, Starmer J, Martin ER. A multiple testing correction method for genetic association studies using correlated single nucleotide polymorphisms. Genet. Epidemiol. 2008;32:361–369. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Turner, S. D. qqman: an R package for visualizing GWAS results using QQ and manhattan plots. bioRxiv (2014).

- 56.Fernando, R. & Garrick, D. GenSel-User manual for a portfolio of genomic selection related analyses. Animal Breeding and Genetics, Iowa State University, Ames (2008).

- 57.Ponsuksili S, Reyer H, Trakooljul N, Murani E, Wimmers K. Single-and Bayesian Multi-Marker Genome-Wide Association for Haematological Parameters in Pigs. PloS one. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.