Abstract

Objective:

To determine whether logopenic features of phonologic loop dysfunction reflect Alzheimer disease (AD) neuropathology in primary progressive aphasia (PPA).

Methods:

We performed a retrospective case-control study of 34 patients with PPA with available autopsy tissue. We compared baseline and longitudinal clinical features in patients with primary AD neuropathology to those with primary non-AD pathologies. We analyzed regional neuroanatomic disease burden in pathology-defined groups using postmortem neuropathologic data.

Results:

A total of 19/34 patients had primary AD pathology and 15/34 had non-AD pathology (13 frontotemporal lobar degeneration, 2 Lewy body disease). A total of 16/19 (84%) patients with AD had a logopenic spectrum phenotype; 5 met published criteria for the logopenic variant (lvPPA), 8 had additional grammatical or semantic deficits (lvPPA+), and 3 had relatively preserved sentence repetition (lvPPA−). Sentence repetition was impaired in 68% of patients with PPA with AD pathology; forward digit span (DF) was impaired in 90%, substantially higher than in non-AD PPA (33%, p < 0.01). Lexical retrieval difficulty was common in all patients with PPA and did not discriminate between groups. Compared to non-AD, PPA with AD pathology had elevated microscopic neurodegenerative pathology in the superior/midtemporal gyrus, angular gyrus, and midfrontal cortex (p < 0.01). Low DF scores correlated with high microscopic pathologic burden in superior/midtemporal and angular gyri (p ≤ 0.03).

Conclusions:

Phonologic loop dysfunction is a central feature of AD-associated PPA and specifically correlates with temporoparietal neurodegeneration. Quantitative measures of phonologic loop function, combined with modified clinical lvPPA criteria, may help discriminate AD-associated PPA.

Primary progressive aphasia (PPA)1 has a heterogeneous clinical presentation that may be related in part to underlying pathology.2 Three variants of PPA have been delineated through consensus criteria,3 including the logopenic variant (lvPPA).3 Core features of lvPPA include impaired single-word retrieval in spontaneous speech and impaired repetition of sentences and phrases4 in the context of relatively preserved memory (table 1). Clinical features of lvPPA may originate partly from a disorder of the phonologic loop, a component of working memory responsible for short-term representation of verbally coded information.4–7 Phonologic short-term maintenance processes have been associated with posterior–superior temporal and inferior parietal areas, corresponding to core anatomic regions of disease in lvPPA.4

Table 1.

Clinical diagnostic criteria for logopenic variant primary progressive aphasia (lvPPA) and definition of the logopenic spectrum

PPA phenotypes have different underlying neuropathologic substrates, including frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) spectrum (FTLD-tau or FTLD-TDP) or Alzheimer disease (AD) pathology.2 AD neuropathology has preferential atrophy in temporoparietal regions compared to FTLD,8 and lvPPA is often associated with AD neuropathology based on in vivo amyloid imaging.9 However, autopsy studies of lvPPA employing modern criteria are limited.10,11 We assessed an autopsy cohort of patients with PPA to test the hypothesis that phonologic loop impairment is associated with AD neuropathology and that a quantitative measure of phonologic loop function (i.e., forward digit span [DF]) associated with temporoparietal pathology may help identify AD neuropathology in PPA. We found that a large majority of AD-associated PPA has impaired DF performance, which correlates with pathologic burden in superior temporal and inferior parietal lobes. Together with modified clinical criteria, quantitative assessment of phonologic loop function may help identify AD neuropathology in PPA.

METHODS

Patients.

Patients were clinically evaluated at the Penn Frontotemporal Degeneration Center (FTDC) or Alzheimer's Disease Center and autopsied at the Center for Neurodegenerative Disease Research. Autopsy was offered to all patients participating in our longitudinal clinical research program who live within reasonable proximity to the Penn FTDC.

Autopsied patients with a primary clinical diagnosis of PPA12 and no evidence of behavioral variant frontotemporal degeneration or a movement disorder at onset (n = 47) were selected from the Penn Integrated Neurodegenerative Disease Database.13 Clinical diagnosis was first made by the treating physician; patients were then classified using PPA variant criteria3 through review of medical charts by at least 2 experienced clinicians or researchers (C.T.M., D.J.I., D.W., K.R., L.A.A.G., M.G., S.A.); group consensus resolved discrepancies.

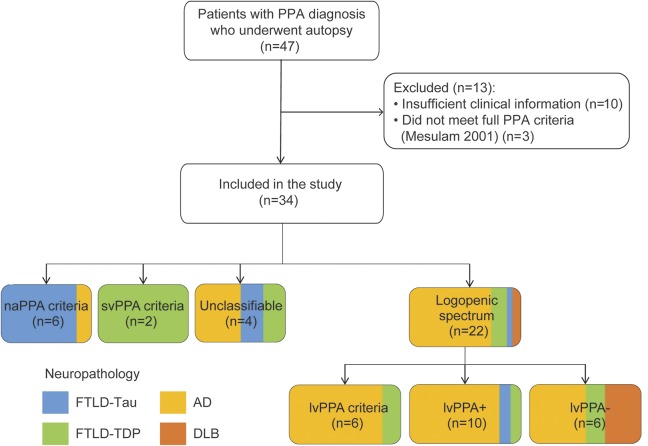

Figure 1 depicts patient selection and classification. We excluded patients with insufficient clinical information (n = 10), defined as the availability of less than 2 visits with complete language assessment (i.e., evaluations of word retrieval, comprehension, repetition, and speech). Three patients were excluded who did not meet PPA criteria12 due to the presence of prominent memory/visuospatial symptoms or nondegenerative disease (e-Methods at Neurology.org).

Figure 1. Flowchart depicting inclusion/exclusion and phenotype classification.

Box shading depicts the frequency of primary neuropathologic diagnosis for each phenotype. AD = Alzheimer disease; DLB = dementia with Lewy bodies; FTLD-TDP = frontotemporal lobar degeneration with TDP inclusions; lvPPA = logopenic variant of primary progressive aphasia; naPPA = nonfluent/agrammatic variant of primary progressive aphasia; PPA = primary progressive aphasia; svPPA = semantic variant of primary progressive aphasia.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

All procedures were performed in accordance with the local institutional review board, including patient informed consent for research participation prior to death.

Chart extraction.

All available medical charts were reviewed to characterize progressive symptoms/signs of word retrieval, repetition, comprehension, speech quality, and other language and cognitive features (e-Methods). Phonologic loop function was examined clinically using qualitative assessment of repetition of multisyllabic words (3–5 syllables), phrases (e.g., “constitutional amendment”), and sentences (e.g., “No ifs, ands, or buts”) and quantitative scoring of the DF task (DF impairment = score ≤4). Average duration of longitudinal assessment was 4.5 ± 2.8 years in AD (n = 19) and 3.6 ± 2.3 years in non-AD (n = 15). We subdivided clinical data into baseline (<2 years after first visit) and follow-up (>2 years after first visit).

Neuropsychological testing.

Neuropsychological data assessed presentation at the first available visit. We examined digit span (forward and backward),14 Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE),15 confrontation naming,16 letter-guided category naming fluency using FAS,17 and 10-item word list delayed recall and recognition.18

Neuropathologic assessment.

Fresh tissue from standard regions19,20 was obtained at autopsy and fixed overnight in either 70% ethanol with 150 mM NaCl or 10% neutral buffered formalin, processed and embedded in paraffin blocks, and cut into 6-μm sections as described.21 Neuropathologic assessment by an experienced neuropathologist (J.Q.T., E.B.L.) used immunohistochemical methods with established monoclonal antibodies19 and diagnostic criteria20,22 with high interrater reliability.23 Recruited patients underwent autopsy prior to commencement of the study (September 1, 2015) and neuropathologic analyses were blinded to phonological loop assessment. Patients were classified by primary neuropathologic diagnosis. FTLD cases were genotyped for pathogenic mutations in GRN, C9orf72, and MAPT as described based on family history risk from structured pedigree analysis.24

Ordinal scores (i.e., 0 = none, 1 = low, 2 = intermediate, 3 = high) for neuropathologic inclusion burden and neuronal loss were analyzed in superior/midtemporal cortex (STC), angular gyrus (ANG), midfrontal cortex (MFC), and cingulate cortex (CING). Brain tissue was sampled from a more posterior portion of STC (Wernicke area) in one case. Ordinal scores of primary proteinopathy (tau for AD/FTLD-tau, TDP-43 for FTLD-TDP, α-synuclein for Lewy body disease) were compared between groups, as well as scores for neuronal loss and gliosis. Missing pathology data (n = 1) were excluded from the analysis.

Neuroimaging.

We performed an exploratory antemortem neuroimaging analysis on a subset of patients (n = 12) with available MRI data. T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo MRI were acquired and whole brain images were preprocessed using PipeDream and Advanced Normalization Tools and resampled to 2 mm voxels, as described.25 We measured gray matter density (GMD) in regions of interest (ROIs) comparable to neuropathology sampling regions (STC, ANG, MFC, CING) using an OASIS imaging atlas26 as described.27 We created z scores for each ROI based on a demographically similar healthy aging cohort of 108 controls (59 male, 49 female; mean age 65.0 years, mean education 16.6 years).

Statistical analyses.

Frequencies of clinical features were compared between pathology-defined groups using Fisher Exact test. Continuous variables were assessed for normality using Shapiro-Wilk test; group comparisons were performed with parametric independent-sample t test or nonparametric Mann-Whitney U as appropriate. We used Spearman correlation to relate ANG and STC pathology with DF along with our negative-control region (CING). Group comparisons of ROI z scores used analysis of covariance, with age and disease duration at time of scanning as covariates. Receiver operator characteristic curve (ROC) analysis assessed sensitivity and specificity of clinical features for AD neuropathology. All analyses were 2-sided with α = 0.05 using SPSS v. 23.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Neuropathologic groups and clinical phenotypes.

A total of 22/34 patients (65%; figure 1) had a baseline presentation fully or partially consistent with published lvPPA criteria (i.e., logopenic spectrum, table 1), including lvPPA (n = 6), lvPPA+ (n = 10), and lvPPA− (n = 6). Of the remaining patients, 6 met criteria for naPPA and 2 for svPPA. Four patients had an unclassifiable phenotype with impaired lexical retrieval, spared repetition, and grammatical or semantic difficulty. Overall, 20/34 (59%) could not be classified using current consensus criteria.3

In this cohort, 19/34 (56%) patients had primary AD neuropathology (table 2), a large majority of which (14/19 [74%]) did not meet published lvPPA criteria. A logopenic spectrum phenotype was found in 16/19 (84%) AD cases. AD neuropathology occurred in 5/6 (83%) with baseline lvPPA (using strict published criteria), 8/10 (80%) with baseline lvPPA+, and 3/6 (50%) with baseline lvPPA−. A total of 4/18 (22%) with AD neuropathology developed severe memory impairment with visuospatial dysfunction consistent with amnestic AD on follow-up, as opposed to no patient with non-AD pathology (table e-1). One patient had primary AD and secondary FTLD-TDP pathologies (table e-2); we repeated our main analyses below after removing this case and found similar results (data not shown).

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characterization of the patient cohort (n = 34)

Non-AD pathologies included 13/15 (87%) with primary FTLD (n = 6 FTLD-TDP, n = 7 FTLD-tau) and 2/15 (13%) with primary dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) pathology. At baseline, naPPA criteria were associated with FTLD-tau (5/6, 83%) and svPPA criteria with FTLD-TDP (2/2, 100%). The 2 DLB cases had an lvPPA− phenotype. FTLD-TDP patients with a GRN mutation were classified as lvPPA (n = 1), lvPPA+ (n = 1), or unclassifiable (n = 1). AD had longer survival (11.1 ± 3.2 years) than non-AD (8.1 ± 4.1, p = 0.04).

Clinical features in neuropathologic groups.

Pathology groups did not differ in age, sex, or time from onset to first visit (p > 0.05). At baseline, the AD group was more often impaired in DF (≤4 digits, p < 0.01) and sentence comprehension (p = 0.01), whereas the non-AD group had higher frequency of effortful speech (p = 0.03). All patients had impaired lexical retrieval. Groups did not differ in sentence repetition. At follow-up, the group difference of impaired DF persisted (p = 0.01) and impaired backward digit span emerged (p = 0.04). Table 3 summarizes clinical features; supplementary data are available in tables e-3 and e-4 (AD/non-AD comparison) and figure e-1 (AD-associated phenotype).

Table 3.

Frequency of clinical features by pathology group at baseline and follow-up

Neuropsychological data.

A subset of patients (n = 29) had neuropsychological data available (table e-5). Both pathology groups had mild baseline global impairment (MMSE: AD 20.1 ± 5.7, non-AD 23.3 ± 4.8). Patients with AD were more impaired in forward (p = 0.01) and backward (p = 0.02) digit span than were patients with non-AD, confirming our dichotomous observations from clinical data.

Neuropathologic data.

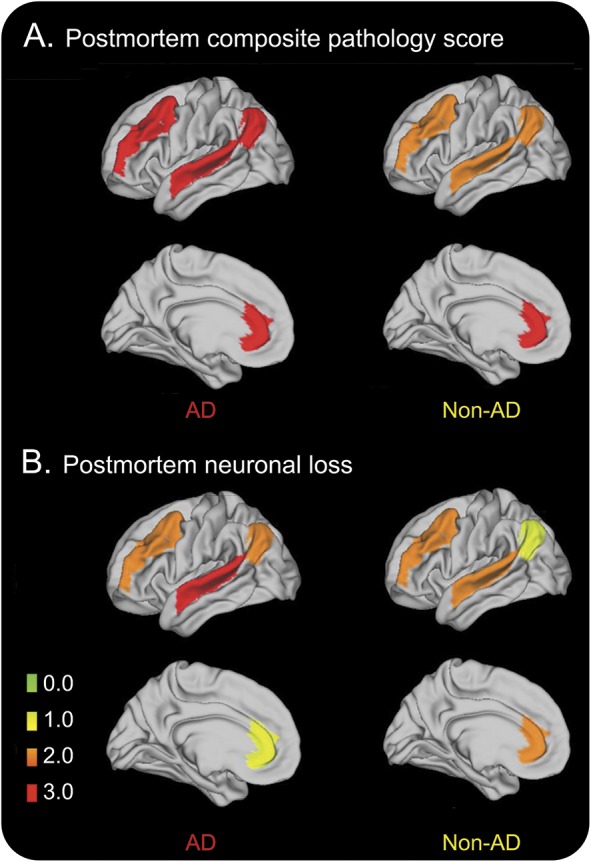

Postmortem pathology scores were compared between groups (AD n = 19, non-AD n = 15 in MFC/CING and n = 14 in STC/ANG). We observed more pathology burden in STC and ANG measured as composite pathology score, neuronal loss, and gliosis in the AD group compared to the non-AD group (p < 0.05; figure 2, A and B, and table e-6). To account for relative differences in overall severity of inclusion burden between diseases, we obtained a within-subject ratio of STC and ANG composite pathology scores to control region (CING) scores, and found again greater pathology in the AD group compared to the non-AD group (p < 0.01). We found that low DF (from neuropsychological testing) correlated with increased composite pathology in STC and ANG (ρ = −0.4, p ≤ 0.03 both) but not in CING (ρ = −0.3, p = 0.09). Preliminary neuroimaging findings of lower GMD in STC and ANG in the AD group were consistent with our postmortem data (tables e-6 and e-7 and figure e-2).

Figure 2. Postmortem burden of pathology in Alzheimer disease (AD) and non-AD groups.

(A) Postmortem pathology burden measured as ordinal score of primary proteinopathy. (B) Postmortem scores of neuronal loss.

Diagnostic accuracy for AD neuropathology.

Published lvPPA criteria were specific (93%) but not sensitive (26%) for AD neuropathology (area under the ROC curve [AUC] 0.60), whereas logopenic spectrum diagnosis (including lvPPA, lvPPA+, and lvPPA−) had improved sensitivity (84%) with modest specificity (60%, AUC 0.72). The combination of impaired DF and logopenic spectrum diagnosis yielded 78% sensitivity and 80% specificity (AUC 0.79). Other ascertained variables (word retrieval, sentence repetition, effortful speech) did not improve diagnostic accuracy (data not shown). At follow-up, lvPPA criteria had 25% sensitivity and 92% specificity (AUC 0.59); logopenic spectrum criteria had 94% sensitivity and 62% specificity (AUC 0.78); impaired DF with logopenic spectrum diagnosis had 94% sensitivity and 67% specificity (AUC 0.80).

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to characterize the clinical PPA spectrum associated with AD neuropathology. We hypothesized that quantitative assessment of phonologic loop function would help identify AD neuropathology due to the neuroanatomic distribution of disease, while lexical retrieval deficits are too ubiquitous to be informative. We found AD neuropathology in 83% of patients meeting strict published lvPPA criteria, though few patients with PPA in this study met these criteria. Within the broader logopenic spectrum (lvPPA, lvPPA+, or lvPPA−), we found AD pathology in 73% of patients. lvPPA criteria achieved some specificity for AD neuropathology but poor sensitivity. Evidence from postmortem pathology and preliminary antemortem findings5,8,28 are consistent with the observation that DF performance correlates with disease burden in posterior–superior temporal and inferior parietal regions. Our findings thus suggest that DF assessment, combined with a broadened, clinical logopenic spectrum diagnosis, improves identification of AD pathology with acceptable sensitivity and specificity (∼80%).

We found that 14/34 (41%) patients met strict criteria for one PPA variant at baseline. There was a high degree of association between naPPA and svPPA and the neuropathologic substrates of FTLD-tau and FTLD-TDP, respectively. Recent autopsy studies reported FTLD-tau in 50%–80% of naPPA and FTLD-TDP in 70%–80% of svPPA.10,11,29 lvPPA criteria were relatively specific for AD neuropathology, as 83% of patients with lvPPA had underlying AD, but only a small number of patients fulfilled published criteria. This frequency is comparable to previous autopsy (55%–77%)10,11 and AD biomarker studies (60%–100%).9,30–34

Several patients (59%) could not be classified using consensus criteria,3 65% of whom had AD neuropathology. Previous series reported that 10%–40% of patients with PPA did not meet criteria for any PPA variant10,11,35–37; AD neuropathology accounted for 40%–60% of these unclassifiable patients.10,11,36 Moreover, we observed that 74% of patients with AD did not meet published lvPPA criteria. Prior studies found that 20%–50% of AD-associated PPA did not meet published lvPPA criteria.10,11 It should be noted that we excluded PPA cases with behavioral or movement disorders at onset that rarely occur in lvPPA, which may have inflated the proportion of AD cases in this report. Nevertheless, our observations suggest that strict published lvPPA criteria are not sensitive enough for AD neuropathology.

Published lvPPA criteria are unreliable.37 We attempted to stratify cases within the logopenic spectrum (lvPPA, lvPPA+, lvPPA−) to help identify PPA with likely AD pathology. Others have also found exceptions to current lvPPA criteria because of spared repetition.10 The same study reported patients meeting criteria for lvPPA and naPPA simultaneously.10 While this was not a finding in our cohort, the co-occurrence of logopenic and nonfluent/agrammatic features was observed in our lvPPA+ group. In another autopsy study,11 1 of 5 unclassified patients had AD pathology with similar features to our lvPPA− phenotype, and a second patient with primary AD and vascular pathologic findings had impaired lexical retrieval and repetition with additional semantic deficits resembling our lvPPA+ group.

Difficulty identifying lvPPA may be related to our observation that impaired lexical retrieval in conversational speech, 1 of 2 core features of lvPPA, occurs in all PPA variants. Therefore, we focused on phonologic loop impairment in lvPPA, including repetition and DF. Impaired sentence repetition was less accurate in distinguishing cases with AD pathology than impaired DF, which may be partly due to the absence of a standardized repetition battery in our retrospective cohort. DF is a favorable measure of phonologic loop dysfunction, including cross-language comparisons, because of the ease of scoring DF performance compared to ambiguities in qualitative sentence repetition assessment. Impairment of sentence repetition may be related to word or syllable length, speech sound errors and omissions, and grammatical complexity. Additional work is needed to establish a brief, reliable assessment of repetition.

Logopenic spectrum patients without impaired repetition (lvPPA−) form a heterogeneous group in terms of progression and neuropathology. However, phonologic loop dysfunction may point to underlying AD. In our study, lvPPA− patients with underlying AD were likely to have impaired DF and to progress to lvPPA. Both lvPPA− patients with baseline DF impairment had AD neuropathology; only 1 lvPPA− case with non-AD (DLB) pathology progressed to lvPPA and did not have baseline DF impairment. In the largest previous study, 2 lvPPA− cases with AD pathology and 2 with FTLD-tau progressed to naPPA, 1 with AD pathology progressed to lvPPA, and 1 with Pick disease did not progress.10 Another patient with lvPPA− phenotype and AD pathology progressed to lvPPA.11 This heterogeneity in clinical progression underscores the importance of finding measures such as phonologic loop dysfunction that predict clinical progression and underlying neuropathology.

We found a high frequency of DF impairment in AD-associated PPA both at baseline and follow-up. Impaired performance in span tasks has been consistently associated with lvPPA.7,38 However, digit span may be impaired in other PPA groups37,39 because it is a complex task involving multiple cognitive, linguistic, and motoric demands.38 Difficulty with DF nevertheless helped predict AD neuropathology across the whole cohort. Further, we found evidence of neuropathologic burden consistent with phonologic loop dysfunction that helps discriminate AD neuropathology. Postmortem measures showed that patients with AD neuropathology have more severe disease in ANG and STC, and elevated postmortem pathology burden correlated with reduced DF performance. We found regional specificity as DF did not correlate with our control region (CING). In addition, we had the opportunity to study antemortem disease distribution in brain regions corresponding to our postmortem analysis. Although underpowered, our preliminary neuroimaging findings were suggestive of more disease burden in phonologic loop regions in AD. Converging antemortem evidence in previous reports implicated inferior parietal MRI atrophy in phonologic loop functioning in nonautopsied lvPPA.4,7,28

When we tested the diagnostic accuracy of clinical features for AD neuropathology, we found the best sensitivity and specificity combining logopenic spectrum diagnosis with baseline DF impairment. This suggests that clinical lvPPA criteria may benefit from the addition of a more reliable measure of phonologic loop impairment combined with modified clinical assessment (table 1). At follow-up, we found increased sensitivity but lower specificity for these features. These findings match our longitudinal analysis where patients with baseline lvPPA− progressed to lvPPA, while patients meeting lvPPA criteria at baseline developed additional language features (lvPPA+). Only 4 (22%) with AD neuropathology (3 baseline lvPPA+, 1 baseline lvPPA−) developed severe memory/visuospatial impairment, suggesting that lvPPA does not necessarily progress to typical amnestic AD.

While most patients had longitudinal visits with structured clinical evaluations, the main limitations of our report are inherent to retrospective case-control studies. The lack of a standardized repetition task in our retrospective cohort, customary in clinical practice, limited our ability to compare repetition to DF as a phonologic loop measure. Our sample size was limited due to the strict requirement of pure PPA with sufficient clinical data to apply modern criteria, and recruitment from a tertiary center may have introduced bias for uncommon disease variants. Therefore, absolute frequencies of clinical findings and diagnostic accuracy may not reflect a population-based cohort, and larger, prospective studies are needed. We implemented modern neuropathologic criteria using the density and topographic locus of disease to identify the primary neuropathology underlying the clinical syndrome,20 but further work in larger autopsy series is needed for more detailed studies of pathologic burden and dual pathology. Composite scores compared pathology-specific inclusions across groups, and should be interpreted as relative rather than absolute pathology burden. Neuropathologic burden may be lateralized to the left hemisphere in PPA,10 yet random sampling involved left hemisphere neuropathology in only 62% of our autopsy series. The small neuroimaging sample provided rare preliminary antemortem evidence in an autopsy-confirmed cohort consistent with our postmortem findings but requires replication in a larger sample. The relatively small number of patients without AD in our cohort limited our ability to compare DF performance between clinical syndromes, e.g., naPPA compared to lvPPA, within neuropathologic groups as well as across the entire cohort. With these limitations in mind, our findings suggest that future lvPPA criteria consider a quantitative metric of phonologic loop function along with a broader clinical phenotype to identify AD-associated PPA.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Amy Halpin, MSc (Penn Frontotemporal Degeneration Center) helped with data acquisition; Kim Firn, MSc (Penn Frontotemporal Degeneration Center) contributed technical assistance for the neuroimaging analysis; Andrew Williams, BSc (Penn Frontotemporal Degeneration Center) helped to prepare figure 2; Dr. B.M. de Jong, MD, PhD (Department of Neurology, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, the Netherlands) reviewed the manuscript; Alzheimer Nederland and Internationale Stichting Alzheimer Onderzoek contributed student travel funding.

GLOSSARY

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- ANG

angular gyrus

- AUC

area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

- CING

cingulate cortex

- DF

forward digit span

- DLB

dementia with Lewy bodies

- FTDC

Frontotemporal Degeneration Center

- FTLD

frontotemporal lobar degeneration

- GMD

gray matter density

- lvPPA

logopenic variant of primary progressive aphasia

- MFC

midfrontal cortex

- MMSE

Mini-Mental State Examination

- PPA

primary progressive aphasia

- ROC

receiver operator characteristic curve

- ROI

region of interest

- STC

superior/midtemporal cortex

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

Editorial, page 2244

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Lucia A.A. Giannini: study concept/design, analysis/interpretation of data, drafting and revising the manuscript for content. David J. Irwin: study concept/design, analysis/interpretation of data, revising the manuscript for content, acquisition of data. Corey T. McMillan: analysis/interpretation of data. Sharon Ash: analysis/interpretation of data. Katya Rascovsky: analysis/interpretation of data. David A. Wolk: analysis/interpretation of data. Vivianna M. Van Deerlin: analysis/interpretation of data, acquisition of data. Edward B. Lee: analysis/interpretation of data, revising the manuscript for content, acquisition of data. John Q. Trojanowski: analysis/interpretation of data, revising the manuscript for content, acquisition of data. Murray Grossman: study concept/design, analysis/interpretation of data, revising the manuscript for content, acquisition of data.

STUDY FUNDING

Supported by NIH (AG17586, AG38490, AG10124, K23NS088341), Alzheimer's Association (BAND-9665), Dana Foundation, Newhouse Foundation, and Brightfocus Foundation (A2016244S).

DISCLOSURE

L. Giannini, D. Irwin, C. McMillan, S. Ash, K. Rascovsky, D. Wolk, V. Van Deerlin, E. Lee, and J. Trojanowski report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. M. Grossman receives research funding from Piramal and Avid, participates in a clinical trial sponsored by Bristol Myer Squibb, and receives financial support for editorial work for Neurology®. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mesulam MM. Slowly progressive aphasia without generalized dementia. Ann Neurol 1982;11:592–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grossman M. Primary progressive aphasia: clinicopathological correlations. Nat Rev Neurol 2010;6:88–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology 2011;76:1006–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gorno-Tempini ML, Brambati SM, Ginex V, et al. The logopenic/phonological variant of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology 2008;71:1227–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith EE, Jonides J. Neuroimaging analyses of human working memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998;95:12061–12068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baddeley A. Working memory: theories, models, and controversies. Annu Rev Psychol 2012;63:1–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer AM, Snider SF, Campbell RE, Friedman RB. Phonological short-term memory in logopenic variant primary progressive aphasia and mild Alzheimer's disease. Cortex 2015;71:183–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McMillan CT, Avants B, Irwin DJ, et al. Can MRI screen for CSF biomarkers in neurodegenerative disease? Neurology 2013;80:132–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabinovici GD, Jagust WJ, Furst AJ, et al. Abeta amyloid and glucose metabolism in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol 2008;64:388–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mesulam MM, Weintraub S, Rogalski EJ, Wieneke C, Geula C, Bigio EH. Asymmetry and heterogeneity of Alzheimer's and frontotemporal pathology in primary progressive aphasia. Brain 2014;137:1176–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris JM, Gall C, Thompson JC, et al. Classification and pathology of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology 2013;81:1832–1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mesulam MM. Primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol 2001;49:425–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xie SX, Baek Y, Grossman M, et al. Building an integrated neurodegenerative disease database at an academic health center. Alzheimers Dement 2011;7:e84–e93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elwood RW. The Wechsler Memory Scale–Revised: psychometric characteristics and clinical application. Neuropsychol Rev 1991;2:179–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan E, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. Boston Naming Test. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mickanin J, Grossman M, Onishi K, Auriacombe S, Clark C. Verbal and nonverbal fluency in patients with probable Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychology 1994;8:385–394. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Welsh K, Butters N, Hughes J, Mohs R, Heyman A. Detection of abnormal memory decline in mild cases of Alzheimer's disease using CERAD neuropsychological measures. Arch Neurol 1991;48:278–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toledo JB, Van Deerlin VM, Lee EB, et al. A platform for discovery: the University of Pennsylvania integrated neurodegenerative disease biobank. Alzheimers Dement 2014;10:477.e1–477.e84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer's Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol 2012;123:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Irwin DJ, Byrne MD, McMillan CT, et al. Semi-automated digital image analysis of Pick's disease and TDP-43 proteinopathy. J Histochem Cytochem 2016;64:54–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackenzie IR, Neumann M, Bigio EH, et al. Nomenclature and nosology for neuropathologic subtypes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration: an update. Acta Neuropathol 2010;119:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montine TJ, Monsell SE, Beach TG, et al. Multisite assessment of NIA-AA guidelines for the neuropathologic evaluation of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2016;12:164–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wood EM, Falcone D, Suh E, et al. Development and validation of pedigree classification criteria for frontotemporal lobar degeneration. JAMA Neurol 2013;70:1411–1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McMillan CT, Irwin DJ, Avants BB, et al. White matter imaging helps dissociate tau from TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2013;84:949–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang H, Yushkevich PA. Multi-atlas segmentation with joint label fusion and corrective learning: an open source implementation. Front Neuroinform 2013;7:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irwin DJ, Brettschneider J, McMillan CT, et al. Deep clinical and neuropathological phenotyping of Pick disease. Ann Neurol 2016;79:272–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonner MF, Grossman M. Gray matter density of auditory association cortex relates to knowledge of sound concepts in primary progressive aphasia. J Neurosci 2012;32:7986–7991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caso F, Mandelli ML, Henry M, et al. In vivo signatures of nonfluent/agrammatic primary progressive aphasia caused by FTLD pathology. Neurology 2014;82:239–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chare L, Hodges JR, Leyton CE, et al. New criteria for frontotemporal dementia syndromes: clinical and pathological diagnostic implications. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014;85:865–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Botha H, Duffy JR, Whitwell JL, et al. Classification and clinicoradiologic features of primary progressive aphasia (PPA) and apraxia of speech. Cortex 2015;69:220–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu WT, McMillan C, Libon D, et al. Multimodal predictors for Alzheimer disease in nonfluent primary progressive aphasia. Neurology 2010;75:595–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leyton CE, Villemagne VL, Savage S, et al. Subtypes of progressive aphasia: application of the international consensus criteria and validation using beta-amyloid imaging. Brain 2011;134:3030–3043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leyton CE, Hodges JR, McLean CA, Kril JJ, Piguet O, Ballard KJ. Is the logopenic-variant of primary progressive aphasia a unitary disorder? Cortex 2015;67:122–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wicklund MR, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Whitwell JL, Josephs KA. Quantitative application of the primary progressive aphasia consensus criteria. Neurology 2014;82:1119–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teichmann M, Kas A, Boutet C, et al. Deciphering logopenic primary progressive aphasia: a clinical, imaging and biomarker investigation. Brain 2013;136:3474–3488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sajjadi SA, Patterson K, Arnold RJ, Watson PC, Nestor PJ. Primary progressive aphasia: a tale of two syndromes and the rest. Neurology 2012;78:1670–1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leyton CE, Savage S, Irish M, et al. Verbal repetition in primary progressive aphasia and Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2014;41:575–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ash S, Evans E, O'Shea J, et al. Differentiating primary progressive aphasias in a brief sample of connected speech. Neurology 2013;81:329–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.