Abstract

Platinum-based antitumor drugs such as 1,1,2,2-cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II) (cisplatin), carboplatin, and oxaliplatin are currently used to treat nearly 50% of all cancer cases, and novel platinum based agents are under development. The antitumor effects of cisplatin and other platinum compounds are attributed to their ability to induce interstrand DNA-DNA cross-links, which are thought to inhibit tumor cell growth by blocking DNA replication and/or preventing transcription. However, platinum agents also induce significant numbers of unusually bulky and helix-distorting DNA-protein cross-links (DPCs), which are poorly characterized because of their unusual complexity. We and others have previously shown that model DPCs block DNA replication and transcription and cause toxicity in human cells, potentially contributing to the biological effects of platinum agents. In the present work, we have undertaken a system-wide investigation of cisplatin-mediated DNA-protein cross-linking in human fibrosarcoma (HT1080) cells using mass spectrometry-based proteomics. DPCs were isolated from cisplatin-treated cells using a modified phenol/chloroform DNA extraction in the presence of protease inhibitors. Proteins were released from DNA strands and identified by mass spectrometry-based proteomics and immunological detection. Over 250 nuclear proteins captured on chromosomal DNA following treatment with cisplatin were identified, including high mobility group (HMG) proteins, histone proteins, and elongation factors. To reveal the exact molecular structures of cisplatin-mediated DPCs, isotope dilution HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS was employed to detect 1,1-cis-diammine-2-(5-amino-5-carboxypentyl)amino-2-(2′-deoxyguanosine-7-yl)-platinum (II) (dG-Pt-Lys) conjugates between the N7 guanine of DNA and the ε-amino group of lysine. Our results demonstrate that therapeutic levels of cisplatin induce a wide range of DPC lesions, which likely contribute to both target and off target effects of this clinically important drug.

Keywords: mass spectrometry, DNA-protein cross-links, cisplatin, proteomics, DNA repair

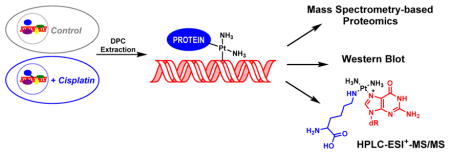

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

DNA-protein cross-links (DPCs) are bulky, helix-distorting lesions that can be induced following exposure to many cytotoxic, mutagenic, and carcinogenic agents including ionizing radiation,1 transition metals,2 and common chemotherapeutic agents such as nitrogen mustards,3–7 platinum agents,8 and alkylnitrosoureas.9 These macromolecular lesions block DNA-protein interactions, interfering with basic cellular functions such as DNA replication, transcription, repair, recombination, and chromatin remodeling,10–13 If left unrepaired, DPCs may result in toxicity and permanent DNA alterations.10,14

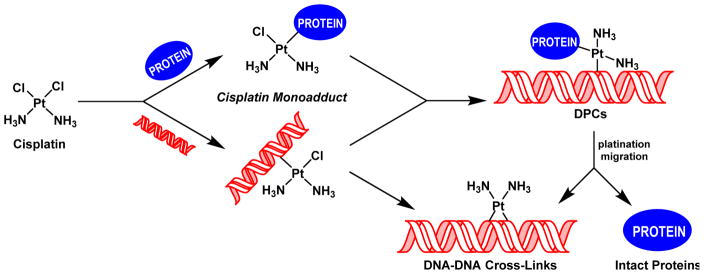

Platinum-based antitumor agents, e.g. 1,1,2,2-cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II) (cisplatin) and its analog cis-diammine-1,1-cyclobutanedicarboxylate platinum(II) (carboplatin), are highly effective in the treatment of testicular and ovarian malignancies, as well as for chemotherapy of bladder, cervical, head and neck, esophageal, and lung cancer.15,16 Upon entering cells, cisplatin is spontaneously hydrolyzed,17 yielding a highly reactive aquated species capable of platinating DNA to form a variety of nucleobase adducts.18–20 The monofunctional DNA adducts formed initially can further react with neighboring bases to produce intrastrand and interstrand DNA-DNA cross-links.20 Alternatively, the monofunctional adducts can be trapped by nuclear proteins found in a close proximity to chromosomal DNA to form covalent DPCs conjugates (Scheme 1).20,21 While cisplatin-induced DNA-DNA cross-links, including 1,2-d(GpG) intrastrand cross-links, 1,2-d(ApG) intrastrand cross-links, and 1,3-d(GpNpG) intrastrand cross-links are well characterized and are thought to play a prominent role in their antitumor effects,20,22–24 relatively little is known about the identities of the corresponding DPC lesions.

Scheme 1.

Formation of DNA-DNA cross-links and DNA-protein cross-links (DPC) by cisplatin.

Several earlier studies have employed biophysical methodologies and western blotting against specific target proteins to show the ability of cisplatin to form DPC lesions.21,25–29 Because of their inherent limitations, such studies have not been able to reveal the full range of cellular proteins participating in DPC formation by cisplatin or to identify their molecular structures. The main goal of the present work was to conduct a system-wide investigation of cisplatin-mediated DPC formation in cultured human cells. We employed an unbiased mass spectrometry based proteomics approach to identify any human proteins that become trapped on DNA in live cells following treatment with cytotoxic concentrations of cisplatin. In addition, liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS) analysis of total proteolytic digests was employed to determine the chemical structures of the cisplatin-induced conjugates.

Materials and Methods

Safety statement

Phenol and chloroform are toxic chemicals that should be handled with caution in a well-ventilated fume hood with appropriate personal protective equipment. 1,1,2,2-Cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II) (cisplatin) is toxic and carcinogenic and needs to be treated with extreme caution.

Chemicals and reagents

1,1,2,2-Cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II) (cisplatin), leupeptin, pepstatin, aprotinin, phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), dithiothreitol (DTT), iodoacetamide, chloroform, ribonuclease A, nuclease P1, phosphodiesterase I (PDE I), phosphodiesterase II (PDE II), and alkaline phosphatase were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Mass spectrometry-grade Trypsin Gold was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). Proteinase K was obtained from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA). Primary polyclonal antibodies specific for glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), flap endonuclease 1 (Fen-1), nucleoin, actin, poly-(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1), elongation factor 1α1 (EF-1α1), and DNA-(apurinic- or apyrimidinic-site) lyase (Ref-1) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Monoclonal antibodies specific for x-ray cross-complementing protein 1 (XRCC-1) and AGT were purchased from Lab Vision/NeoMarkers (Fremont, CA). Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Cis-1,1-diammine-2-(5-amino-5-carboxypentyl)-amino-2-(2′-deoxyguanosine-7-yl)-platinum(II) (dG-Pt-Lys) was prepared in our laboratory and purified by HPLC.

Cell culture

Human fibrosarcoma (HT1080) cells30 were obtained from the American Type Cell Culture Collection. The cells were maintained as exponentially growing monolayer cultures in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 9% fetal bovine serum (FBS) maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Cisplatin cytotoxicity assay

HT1080 cells were plated in Dulbeccos modified Eagle’s medium containing 9% FBS at a density of 5 × 105 cells/6 cm dish and permitted to adhere overnight. On the following morning, dishes (in triplicate) were treated with cisplatin (0, 5, 10, 50, 100, 250, or 500 μM) for 3 h at 37°C in serum-free growth media. Following treatment, cells were either immediately collected or placed in drug-free serum-containing media and allowed to recover for 18 h. The effect of cisplatin on cell survival was determined by direct cell counting. In brief, after incubation the cells were recovered via treatment with trypsin and resuspended in normal growth media containing trypan blue at a final volume of 1 mL. Cells were counted using a hemocytometer, and cytotoxicity was expressed as the number of cells surviving cisplatin treatment relative to non-drug-treated controls.

Isolation of proteins cross-linked to chromosomal DNA by cisplatin

To analyze DPC formation in mammalian cells exposed to cisplatin, HT1080 cells (107 cells, in triplicate) were treated with increasing concentrations of cisplatin (0, 10, 50, 100, 250, or 500 μM) for 3 h at 37°C. Following exposure, the cells were washed three times with ice cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and DPCs were isolated by a modified phenol/chloroform extraction method as described previously. In brief, cells were recovered from dishes by scraping6,31,32 and suspended in PBS at a final density of ~2 × 106 cells/mL. To isolate nuclei, cells were lysed by adding an equal volume of 2X cell lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl/10 mM MgCl2/2% v/v Triton-X100/0.65 M sucrose), incubated on ice for 5 min, and centrifuged at 2,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The nuclear pellet was re-suspended in a saline-EDTA solution (75 mM NaCl/24 mM EDTA/1% (w/v) SDS, pH 8.0) containing RNase A (10 μg/mL) and a protease inhibitor cocktail (1 mM PMSF; 1 μg/mL pepstatin; 0.5 μg/mL leupeptin; 1.5 μg/mL aprotinin) at a concentration of ~ 5 × 106 nuclei/mL and incubated for 2 h at 37°C with gentle shaking. To isolate chromosomal DNA containing covalent DPCs, nuclear lysates were extracted with two volumes of Tris-buffer saturated phenol, and the resulting white emulsion was centrifuged at 1,000 g for 15 min at room temperature. The aqueous layer and the interface material were subjected to a second extraction with two volumes of Tris buffer saturated phenol:chloroform (1:1). DNA was precipitated from the aqueous/interface layers with cold ethanol. Samples were centrifuged at 4,000 g for 20 min at 4°C, and the resulting DNA pellet was washed with cold 70% ethanol, air dried, and reconstituted in 1 mL Millipore water. DNA concentrations were estimated by UV spectrophotometry. DNA amounts and its purity were determined by quantitation of dG in enzymatic hydrolysates as described previously.6 Typical DNA yields were 50 – 75 μg DNA from 107 HT1080 cells.

Mass spectrometric identification of cross-linked proteins

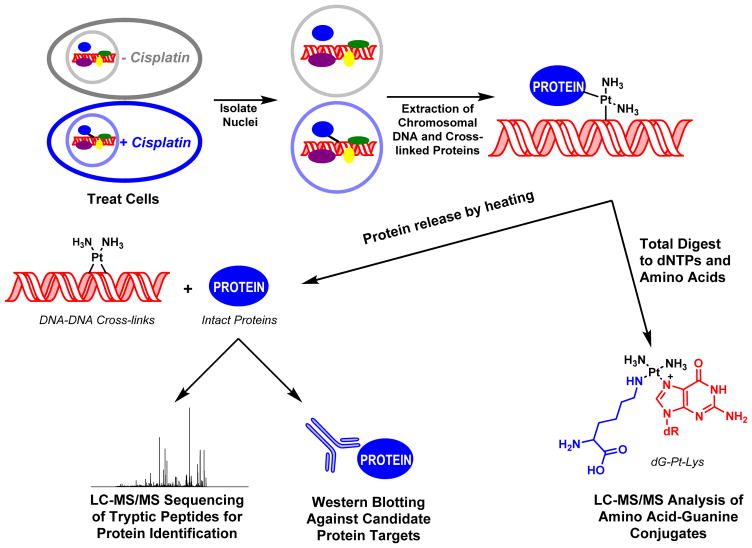

To identify cellular proteins that become covalently attached to chromosomal DNA in cisplatin-treated cells, HT1080 cells (~107 cells, in triplicate) were incubated in serum-free media for 3 h at 37 ºC in the presence or absence of 100 μM cisplatin. Chromosomal DNA containing covalently cross-linked proteins was isolated by a modified phenol/chloroform extraction and quantified as described above. DNA (30 μg) was dissolved in 50 μL of 1X NuPAGE Sample Buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and heated at 70 °C for 1 h to release the cross-linked proteins. Our earlier studies have revealed that heating releases intact proteins from cisplatin-induced DPCs via platination migration to a neighboring DNA base (Ming and Tretyakova, unpublished observations). The resulting proteins were separated using 12% Tris-HCl Ready Gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and stained with SimplyBlue SafeStain (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Gel regions containing protein bands were divided into five sections encompassing the entire molecular weight range, and the gel sections were further diced into ~1 mm pieces. The proteins present within the gel pieces were subjected to in gel tryptic digestion as described elsewhere.33 In brief, gel pieces were rinsed with 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate, and the protein thiols were subjected to reduction with DTT (300 mM) and alkylation with iodoacetamide. The gel pieces were then dehydrated by incubation with acetonitrile, dried under vacuum, and reconstituted in 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer. Mass spectrometry-grade trypsin (2–3 μg) (Promega, Madison, WI) was added, and the samples were digested overnight at 37 °C. The resulting tryptic peptides were extracted with 60% acetonitrile containing 0.1% aqueous formic acid, evaporated to dryness, desalted by ZipTip C18 purification (ZipTip C18 Pipette Tips, Millipore, Temecula, CA), and finally reconstituted in 0.1% formic acid (25 μL) prior to mass spectrometry analysis.

Tryptic peptides were analyzed by HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS with a Thermo Scientific LTQ Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer in line with an Eksigent NanoLC-Ultra 2D HPLC system, a nanospray source, and Xcalibur 2.1.0 software for instrument control. Peptide samples (8 μL) were trapped on a 180 μm × 20 mm Symmetry C18 column (Waters, Milford, MA) upon elution with 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (B) at a flow composition of 95% A and 5% B at 5 μL/min for 3 minutes. Following trapping, the flow was reversed, decreased to 0.3 μL/min, and the peptides were then eluted off the trap column and onto a capillary column (75 μm ID, 10 cm packed bed, 15 μm orifice) created by hand packing a commercially purchased fused-silica emitter (New Objective, Woburn MA) with Zorbax SB-C18 5 μm separation media (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). The solvent composition was initially set at 5% B, followed by a linear increase to 60% B over 60 min and further to 95% B in 5 min. Liquid chromatography was carried out at ambient temperature. Centroided MS-MS scans were acquired using an isolation width of 2.5 m/z, an activation time of 30 ms, an activation Q of 0.25, 35% normalized CID collision energy, and 1 microscan with a max ion time of 100 ms for each MS/MS scan. The mass spectrometer was mass calibrated prior to each analysis and the spray voltage was adjusted to assure a stable spray. Typical MS parameters were as follows: spray voltage of 1.6 kV, a capillary temperature of 275°C, and an S-lens RF Level of 50%. Peptide MS/MS spectra were collected using data-dependent scanning in which one full scan mass spectrum was followed by eight MS/MS spectra. Dynamic exclusion was enabled for 60 s and singly charged species were excluded.

Mass spectral data were analyzed using an in-house developed software pipeline, TINT, which linked raw data extraction, database searching, and probability scoring. Raw data were extracted and converted to the mzXML format using ReadW. Spectra that contained fewer than 6 peaks or had less than 20 measured total ion current were excluded. Data were searched using the SEQUEST v.27 algorithm34,35 on a high speed, multiprocessor Linux cluster in the University of Minnesota Super Computing Institute using the human subset consisting of the NCBI derived human protein database v200806 combined with its reversed counterpart along with common protein contaminants totaling 70,711 entries. Search parameters included trypsin specificity and up to 5 missed cleavage sites. Cysteine carboxamidomethylation (+57.0215 Da) was set as a fixed modification, and methionine oxidation (+15.9949 Da) was set as a variable modification. Precursor mass tolerance was set to 10 ppm within the calculated average mass, and fragment ion mass tolerance was set to 10 mmu of their monoisotopic mass. Identified peptides were filtered using Scaffold 3 software (Proteome Software, INC., Portland, OR)36 to a target false discovery rate (FDR) of 5%. The FDR was calculated as follows: FDR = (2R)/(R+F)*100, where R is the number of passing reversed peptide identifications and F is the number of passing forward (normal orientation) peptide identifications. A second round of filtering removed proteins supported by less than four distinct peptide identifications in the analyses. Parsimony rules were applied to generate a minimal list of proteins that explained all of the peptides that passed our entry criteria.37 Furthermore, t-test analyses were performed on the total ion counts of the identified proteins to ensure that the levels of proteins captured from treated samples were significantly higher than those in untreated controls. All statistical analyses were conducted in Scaffold version 3.0. The significance level was set at 5% (p < 0.05).

Western blot analysis of identified proteins

HT1080 cells (~107) were treated with cisplatin (0, 10, 50, 100, 250, or 500 μM) for 3 h at 37°C. Chromosomal DNA, along with any covalently bound proteins, was extracted and quantified as described above. Approximately 30 μg of DNA from each sample was subjected to heating (1 h at 70°C) to release the intact proteins via platination transfer. Proteins were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to Trans-blot nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Following blocking in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 5% (w/v) bovine serum albumin, the membranes were incubated with the primary antibody against a target protein for 3 h at room temperature, rinsed with TBS buffer, and incubated overnight at 4°C with the corresponding alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibody. The blots were washed and developed with SIGMA Fast BCIP/NBT (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The developed blots were scanned as image files. ImageJ software (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) was used to quantify the optical densities of the protein bands. The efficiency of DNA-protein cross-linking was approximated by comparing signal intensities of the protein which was co-purified with chromosomal DNA (corresponding to cross-linked protein) and the intensity of the corresponding protein band present in the whole cell protein lysate (representing total cellular proteins).6

HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS analysis of dG-Pt-Lys in cells exposed to cisplatin

HT1080 cells (~107) were incubated in serum-free media in the presence or absence of 100 μM cisplatin for 3 h at 37 °C. Chromosomal DNA containing DPCs was isolated using the modified phenol/chloroform extraction procedure described above. DNA (50 μg) was digested with phosphodiesterase I (240 mU), phosphodiesterase II (240 mU), DNase I (120 mU) and alkaline phosphatase (6 U) overnight at 37°C to produce protein-nucleoside conjugates. Samples were dried under vacuum, reconstituted in 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate, and digested to peptides with trypsin (2–3 μg, 37°C overnight). To achieve complete hydrolysis to amino acids, the resulting tryptic peptides were dried under vacuum, reconstituted in water, and digested with proteinase K (20 μg) for 48 h at room temperature. The digest mixtures were subjected to off-line HPLC separation using an Agilent Technologies HPLC system (1100 model) incorporating a diode array detector and a Supelcosil LC-18-DB (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm) column (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The column was eluted at a flow rate of 1 mL/min using 15 mM ammonium acetate, pH 4.9 (A) and acetonitrile (B). The solvent composition was changed linearly from 0 to 24% B over 24 min and further to 60% B in 6 min. HPLC fractions containing dG-Pt-Lys (5–7 min) were collected, dried under vacuum, and reconstituted in 15 mM ammonium acetate (25 μL) for HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS analysis (injection volume, 8 μL).

HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS analyses of dG-Pt-Lys conjugates were conducted with a Thermo-Finnigan TSQ Vantage mass spectrometer in line with an Eksigent MicroAS autosampler and nanoLC 2D HPLC system, a heated ESI source, and Xcalibur 2.1.0 software for instrument control. Chromatographic separation was accomplished using a Hypercarb HPLC column (100 mm × 0.5 mm, 5 μm, ThermoScientific, Waltharm, MA) eluted with a gradient of 15 mM ammonium acetate (A) and 1:1 acetonitrile:water with 1% formic acid (B) at a flow rate of 13 μL/min. The gradient program began at 2% B, followed by a linear increase to 10% B in 10 min and further to 80% B in 8 min. The column was washed with 80% B for 5 min, and the solvent composition was brought back to 2% B in 6 min. Using this gradient, dG-Pt-Lys eluted at ~17.3 min. ESI was achieved at a spray voltage of 3.2 kV and a capillary temperature of 200°C. CID was performed with Ar as the collision gas (2.0 mTorr) at collision energy of 25 V. MS parameters were optimized for maximum response during infusion of a standard solution of dG-Pt-Lys and may vary slightly between experiments. HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS analyses were performed in the selected reaction monitoring (SRM) mode using the mass transitions corresponding to neutral losses of 2′-deoxyribose, ammonia, and dG from protonated molecules of dG-Pt-Lys in a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (m/z 641.3 [M]+ → 508.2 [M–NH3–deoxyribose+H]+, and 340.1 [M–2NH3–deoxyguanosine]+).

Results

Cytotoxicity Experiments

To establish the effects of cisplatin treatment on cellular viability, HT1080 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of the drug (0 – 250 μM) for 3 h. Cell numbers were determined either immediately after treatment (Figure S1) or following overnight incubation in a drug free media (Figure S2). Cytotoxicity was measured as the percentage of cells surviving cisplatin treatment as compared to untreated controls. Treatment with cisplatin for 3 hours had no immediate effect on cell viability (Figure S1), but resulted in a significant decrease in cell numbers if treated cells were left overnight, with approximately 70% cell death observed following treatment with 100 μM cisplatin (Figure S2).

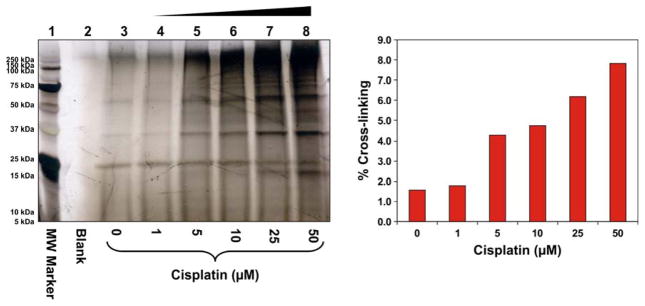

Concentration-dependent DPC formation in cisplatin-treated cells

To investigate DPC formation with increasing concentrations of cisplatin, HT1080 cells were treated with 0, 1, 5, 10, 25, or 50 μM cisplatin for 3 h. DNA was extracted by the modified phenol/chloroform extraction method developed in our laboratory.6 Our previously published studies have shown that this methodology removes non-covalently bound proteins, but preserves covalent DNA-protein conjugates.6 DNA aliquots from each sample were taken and heated at 70°C to release the cross-linked proteins from DNA via platination migration (Ming and Tretyakova, unpublished observations). SDS-PAGE analysis of the released proteins revealed numerous protein bands present in cisplatin-treated samples (lanes 4–8, Figure 1), although control samples (Lane 3) contained background DPC levels. Significant increase in DPC abundance was observed in cells treated with 50 μM cisplatin, reaching an estimated 8% cross-linking efficiency (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Concentration-dependent formation of DPCs in nuclear protein extracts prepared from HeLa human cervical carcinoma cells following exposure to cisplatin. (A) Nuclear protein extracts from HeLa cells (500 μg) and 5′-biotinylated double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (3.12 nmol) were incubated in the presence of 0–50 μM Cisplatin. The resulting DPCs were captured on streptavidin beads, and the proteins were resolved on 12% SDS-PAGE. Gels were stained with SilverQuest SilverStain to visualize the cross-linked proteins. (B) Densitometric analysis of protein bands in the 25 – 250 kDa molecular weight range was used to estimate the extent of total protein cross-linking to DNA in the presence of cisplatin. Known amounts of nuclear protein extract were analyzed as a control to estimate the cross-linking efficiency.

Identification of Cross-linked Proteins by Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics (Scheme 2)

Scheme 2.

Strategy for the isolation and analysis of DPCs from cisplatin-treated mammalian cell cultures.

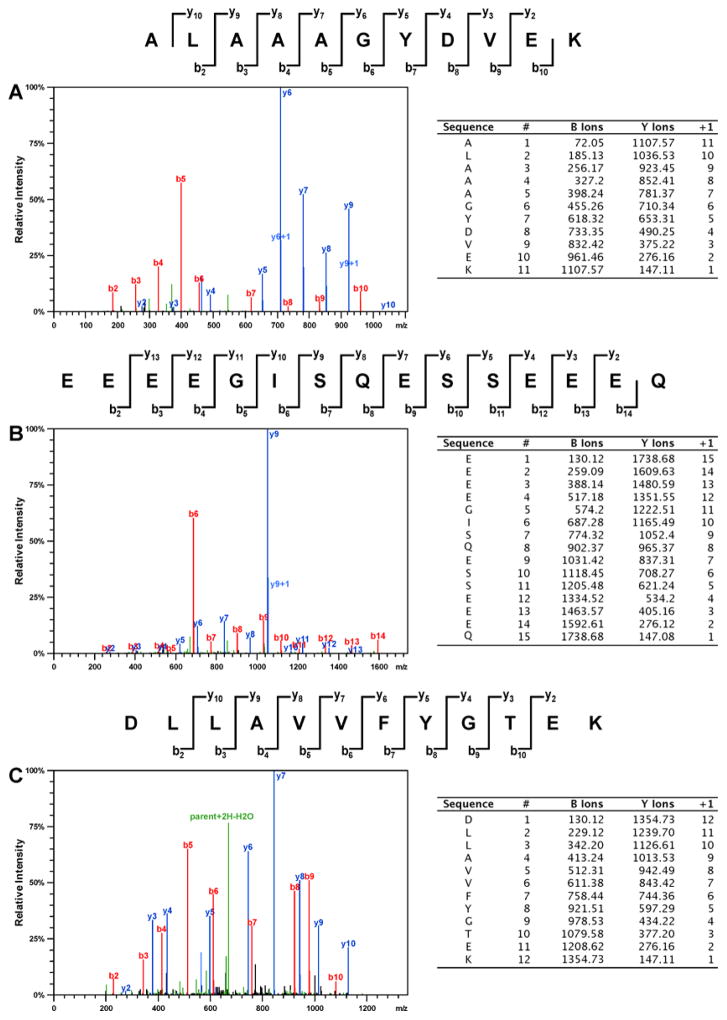

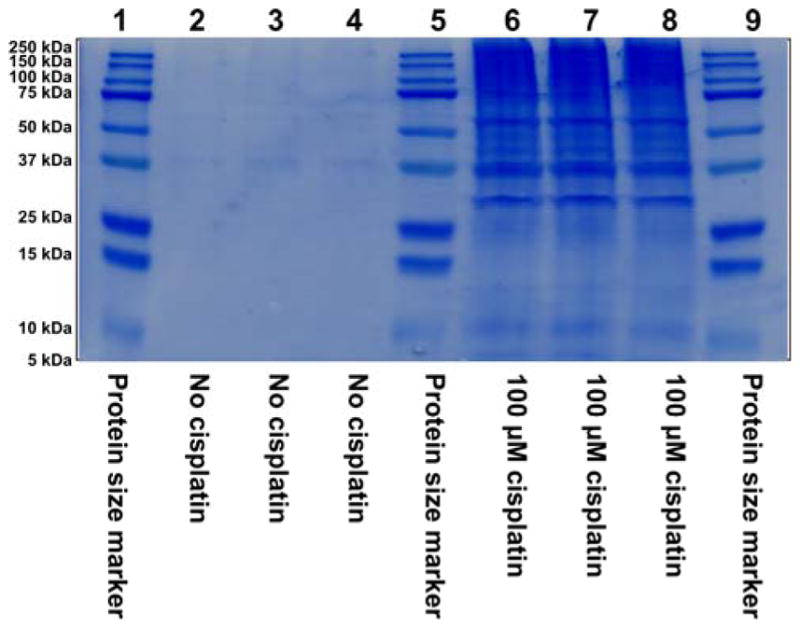

To determine the identities of the proteins participating in cisplatin-mediated DPC formation in vivo, HT1080 cells (~ 107 cells, in triplicate) were treated with cisplatin (100 μM), while control cells were incubated in growth media lacking the drug. This concentration was selected based on our preliminary experiments shown in Figure 1 and are approximately 3-fold higher than typical plasma concentrations observed in treated patients. Our cytotoxicity experiments have shown that 3 h treatment with 100 μM cisplatin to did not affect cell viability (Figure S1), although significant cell death was observed if treated cells were left overnight (Figure S2). Following DNA extraction,6 the cross-linked proteins were released by heating and resolved by SDS-PAGE, followed by simply blue staining (Figure 2). Numerous protein bands were present in cisplatin-treated samples (lanes 6–8, Figure 2), while the untreated samples exhibited minimal protein bands (lanes 2–4, Figure 2). It should be noted that simply blue staining is significantly less sensitive than silver staining used in experiment shown in Figure 1. Gel regions within the molecular weight range of 10–260 kDa were excised from the gel and subjected to in-gel tryptic digestion, followed by HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS analysis of the peptides.38 Protein identification was based on the MS/MS spectra of at least four tryptic peptides, which revealed characteristic b- and y-series fragment ions used to determine their amino acid sequence (see examples in Figure 3).

Figure 2.

SDS-PAGE analysis of samples employed in the proteomics studies of cisplatin-induced DPCs. HT1080 cells (~107 in triplicate) were incubated for 3 h in absence (lanes 2–4) or presence (lanes 6–8) of 100 μM cisplatin, and proteins covalently attached to chromosomal DNA were isolated as described in the Methods section. Proteins were resolved by 12% SDS-PAGE and visualized by staining with SimplyBlue SafeStatin. Molecular weight markers (lanes 1, 5 and 9) were included to permit subsequent recovery of proteins from distinct molecular weight ranges as described in the text.

Figure 3.

Representative HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS spectra of tryptic peptides used in the identification of DPCs involving histone H1D (A), HMG B1 (B), and XRCC-6 protein (C).

Database searching and parsimony analysis of the MS/MS spectral data resulted in identification of 256 proteins that co-purified with chromosomal DNA from cisplatin-treated cells (Table 1). All protein identifications were supported by at least four unique peptides. Statistical analyses were conducted to compare proteomics results for treated and untreated samples, and only proteins which exhibited significantly increased total ion counts in treated samples (p < 0.05) were included in the list. The molecular weights of the identified proteins (Table 1) were consistent with their positions on the gel, although some of the proteins were also present in a higher molecular weight fraction, probably due to the accompanied protein-protein cross-linking or proteins with post-translational modifications that affect the charge state of the proteins.

Table 1.

Proteins participating in cross-linking to chromosomal DNA in human fibrosarcoma HT1080 cells treated with cisplatin (100 μM for 3 h).

| Swiss-Port ID | Identified Proteins | % Coverage | No. of Unique Peptides | No. of Assigned Spectra | Primary Cellular Function | Protein MW (Da) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| P62258 | 14-3-3 Protein epsilon | 24 | 5 | 11 | Cell Signaling/Motility/Architecture | 29175.0 |

| P62736 | Actin, aortic smooth muscle | 24 | 8 | 37 | 42010.1 | |

| P60709 | Actin, cytoplasmic 1 (β-actin) | 35 | 7 | 97 | 41737.8 | |

| Q01518 | Adenylyl cyclase-associated protein 1 | 12 | 4 | 9 | 51855.5 | |

| P12814 | α-Actinin-1 | 13 | 10 | 19 | 103061.1 | |

| O43707 | α-Actinin-4 | 10 | 6 | 11 | 104857.2 | |

| P04083 | Annexin A1 | 37 | 9 | 22 | 38715.9 | |

| P07355 | Annexin A2 | 58 | 15 | 36 | 38606.1 | |

| P23528 | Cofilin-1 | 45 | 5 | 15 | 18503.2 | |

| Q07065 | Cytoskeleton-associated protein 4 | 9 | 4 | 7 | 66022.2 | |

| Q16643 | Drebrin | 14 | 6 | 10 | 71428.6 | |

| P14625 | Endoplasmin | 38 | 24 | 80 | 92471.7 | |

| P15311 | Ezrin | 9 | 5 | 9 | 69414.7 | |

| P21333 | Filamin-A | 3 | 4 | 6 | 280729.4 | |

| Q99988 | Growth/differentiation factor 15 | 23 | 6 | 12 | 34154.8 | |

| P07900 | Heat shock protein HSP 90-α | 23 | 13 | 45 | 84663.2 | |

| P08238 | Heat shock protein HSP 90-β | 21 | 12 | 75 | 83267.3 | |

| O95373 | Importin-7 | 7 | 5 | 15 | 119519.5 | |

| P05787 | Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 8 | 42 | 18 | 74 | 53706.2 | |

| P02545 | Prelamin-A/C | 53 | 34 | 93 | 74140.7 | |

| P20700 | Lamin-B1 | 36 | 16 | 29 | 66409.6 | |

| Q03252 | Lamin-B2 | 22 | 13 | 46 | 67689.8 | |

| Q15185 | Prostaglandin E synthase 3 | 42 | 6 | 15 | 18697.9 | |

| P61026 | Ras-related protein Rab-10 | 28 | 5 | 9 | 22542.1 | |

| Q13813 | Spectrin α chain, brain | 37 | 75 | 161 | 284542.7 | |

| Q01082 | Spectrin β chain, brain 1 | 27 | 46 | 91 | 274613.4 | |

| Q9UH99 | SUN domain-containing protein 2 | 10 | 4 | 9 | 80312.2 | |

| P09493 | Tropomyosin α-1 chain | 14 | 4 | 4 | 32710.0 | |

| Q71U36 | Tubulin α-1A chain | 41 | 14 | 53 | 50135.7 | |

| P07437 | Tubulin β chain | 16 | 4 | 20 | 49670.6 | |

| Q13885 | Tubulin β-2A | 36 | 11 | 91 | 49907.1 | |

| P68371 | Tubulin β-2C chain | 20 | 6 | 18 | 49830.7 | |

| Q9BUF5 | Tubulin β-6 chain | 18 | 4 | 6 | 49857.2 | |

| P08670 | Vimentin | 65 | 28 | 990 | 53652.7 | |

|

| ||||||

| P31946 | 14-3-3 protein β/α | 19 | 5 | 10 | Cellular Homeostasis/Cell Cycle | 28083.1 |

| P62244 | 40S ribosomal protein S15a | 29 | 4 | 9 | 14840.0 | |

| P62847 | 40S ribosomal protein S24 | 29 | 4 | 8 | 15423.8 | |

| P61247 | 40S ribosomal protein S3a | 41 | 10 | 23 | 29945.3 | |

| P62753 | 40S ribosomal protein S6 | 23 | 5 | 11 | 28681.7 | |

| P08865 | 40S ribosomal protein SA | 36 | 8 | 15 | 32854.1 | |

| P10809 | 60 kDa heat shock protein, mitochondrial | 23 | 8 | 19 | 61055.7 | |

| P11021 | 78 kDa glucose-regulated protein OS=Homo | 23 | 11 | 24 | 72334.7 | |

| P84077 | ADP-ribosylation factor 1 | 34 | 4 | 8 | 20697.6 | |

| P18085 | ADP-ribosylation factor 4 | 22 | 4 | 9 | 20511.6 | |

| P15144 | Aminopeptidase N | 25 | 18 | 40 | 109542.4 | |

| Q9UKV3 | Apoptotic chromatin condensation inducer in the nucleus | 3 | 4 | 7 | 151887.9 | |

| P25705 | ATP synthase subunit α, mitochondrial | 14 | 7 | 10 | 59752.1 | |

| P06576 | ATP synthase subunit β, mitochondrial | 10 | 4 | 7 | 56560.6 | |

| O00571 | ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX3X | 9 | 4 | 8 | 73245.8 | |

| P27824 | Calnexin | 23 | 14 | 36 | 67570.2 | |

| P27797 | Calreticulin | 52 | 18 | 54 | 48142.9 | |

| Q9UQ88 | Cell division protein kinase 11A | 14 | 10 | 22 | 90976.0 | |

| Q68CQ4 | Digestive organ expansion factor homolog | 12 | 7 | 9 | 87057.4 | |

| P62495 | Eukaryotic peptide chain release factor subunit 1 | 13 | 4 | 7 | 49032.6 | |

| Q99613 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit C | 6 | 5 | 7 | 105347.2 | |

| O60841 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5B | 12 | 11 | 24 | 138831.5 | |

| P02751 | Fibronectin | 8 | 10 | 21 | 262616.9 | |

| P09382 | Galectin-1 | 39 | 5 | 11 | 14715.8 | |

| P14314 | Glucosidase 2 subunit β | 11 | 5 | 6 | 59425.8 | |

| P04406 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) | 35 | 8 | 18 | 36053.4 | |

| P62826 | GTP-binding nuclear protein Ran | 28 | 5 | 10 | 24423.1 | |

| P11142 | Heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein | 13 | 5 | 16 | 70899.8 | |

| Q1KMD3 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U-like protein 2 | 20 | 13 | 24 | 85105.2 | |

| Q9Y4L1 | Hypoxia up-regulated protein 1 | 18 | 12 | 28 | 111336.8 | |

| P05556 | Integrin β-1 | 16 | 10 | 20 | 88415.1 | |

| P05783 | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 18 | 53 | 21 | 61 | 48059.0 | |

| P35580 | Myosin-10 | 8 | 11 | 25 | 229005.3 | |

| P35579 | Myosin-9 | 25 | 38 | 96 | 226537.5 | |

| P07196 | Neurofilament light polypeptide | 53 | 25 | 69 | 61517.8 | |

| Q14978 | Nucleolar and coiled-body phosphoprotein 1 | 8 | 5 | 10 | 73604.2 | |

| Q13823 | Nucleolar GTP-binding protein 2 | 10 | 5 | 9 | 83656.0 | |

| Q9Y2X3 | Nucleolar protein 58 | 21 | 8 | 17 | 59580.2 | |

| P19338 | Nucleolin (C-23) | 36 | 25 | 305 | 76615.9 | |

| P06748 | Nucleophosmin | 47 | 10 | 52 | 32575.5 | |

| Q99733 | Nucleosome assembly protein 1-like 4 | 21 | 6 | 11 | 42823.9 | |

| P62937 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase A | 28 | 5 | 9 | 18012.9 | |

| Q13427 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase G | 5 | 4 | 6 | 88619.0 | |

| Q06830 | Peroxiredoxin-1 | 59 | 9 | 18 | 22110.9 | |

| P18669 | Phosphoglycerate mutase 1 | 25 | 4 | 6 | 28804.8 | |

| P13796 | Plastin-2 | 15 | 6 | 10 | 70292.1 | |

| O00622 | Protein CYR61 | 21 | 8 | 15 | 42026.0 | |

| P07237 | Protein disulfide-isomerase | 38 | 15 | 38 | 57118.1 | |

| P13667 | Protein disulfide-isomerase A4 | 13 | 9 | 17 | 72934.0 | |

| Q58FF3 | Putative endoplasmin-like protein | 9 | 4 | 10 | 45859.7 | |

| Q58FF8 | Putative heat shock protein HSP 90-β-2 | 18 | 6 | 11 | 44350.2 | |

| Q58FF7 | Putative heat shock protein HSP 90-β-3 | 20 | 14 | 170 | 68326.5 | |

| P14618 | Pyruvate kinase isozymes M1/M2 | 13 | 5 | 12 | 57937.5 | |

| P51149 | Ras-related protein Rab-7a | 33 | 6 | 10 | 23490.0 | |

| Q14692 | Ribosome biogenesis protein BMS1 homolog | 8 | 6 | 8 | 145812.2 | |

| Q14137 | Ribosome biogenesis protein BOP1 | 23 | 12 | 20 | 83629.3 | |

| Q9Y265 | RuvB-like 1 | 16 | 6 | 10 | 50229.4 | |

| P62136 | Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase PP1-α catalytic subunit | 25 | 6 | 9 | 37513.9 | |

| Q9BXP5 | Serrate RNA effector molecule homolog | 16 | 11 | 16 | 100669.7 | |

| Q9NQZ2 | Something about silencing protein 10 | 19 | 10 | 35 | 54559.2 | |

| P78371 | T-complex protein 1 subunit β | 13 | 4 | 7 | 57489.9 | |

| P40227 | T-complex protein 1 subunit ζ | 17 | 4 | 7 | 58025.3 | |

| P37802 | Transgelin-2 | 23 | 4 | 7 | 22391.9 | |

| P43307 | Translocon-associated protein subunit α | 20 | 4 | 9 | 32236.0 | |

| Q9BV38 | WD repeat-containing protein 18 | 16 | 4 | 4 | 47405.1 | |

| Q86VM9 | Zinc finger CCCH domain-containing protein 18 | 11 | 6 | 10 | 106379.8 | |

|

| ||||||

| P23396 | 40S ribosomal protein S3 | 35 | 7 | 14 | DNA Damage Response/DNA Repair | 26688.6 |

| Q9Y5B9 | FACT complex subunit SPT16 | 40 | 41 | 113 | 119917.4 | |

| Q08945 | FACT complex subunit SSRP1 | 51 | 29 | 185 | 81077.6 | |

| P09429 | High mobility group protein B1 (HMG B1) | 23 | 5 | 22 | 24894.7 | |

| P26583 | High mobility group protein B2 (HMG B2) | 45 | 11 | 32 | 24034.6 | |

| P17096 | High mobility group protein HMG-I/HMG-Y | 45 | 5 | 10 | 11676.2 | |

| P16403 | Histone H1D | 19 | 5 | 14 | 21365.8 | |

| Q96QV6 | Histone H2A type 1-A | 40 | 5 | 18 | 14234.2 | |

| Q96A08 | Histone H2B type 1-A | 28 | 4 | 9 | 14168.0 | |

| P33778 | Histone H2B type 1-B | 36 | 8 | 31 | 13950.8 | |

| P62805 | Histone H4 | 54 | 6 | 79 | 11367.7 | |

| P09874 | Poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase 1 (PARP-1) | 4 | 4 | 5 | 113087.8 | |

| Q9NY61 | Protein AATF | 41 | 17 | 37 | 63135.0 | |

| B2RPK0 | Putative high mobility group protein B1-like 1 | 32 | 10 | 41 | 24238.8 | |

| P23246 | Splicing factor, proline- and glutamine-rich | 16 | 7 | 11 | 76149.5 | |

| Q9UIG0 | Tyrosine-protein kinase BAZ1B | 5 | 6 | 10 | 170907.0 | |

| P13010 | X-ray repair cross-complementing protein 5 (XRCC-5 or Ku80/86) | 11 | 4 | 10 | 82707.1 | |

| P12956 | X-ray repair cross-complementing protein 6 (XRCC-6 or Ku70) | 27 | 12 | 28 | 69846.4 | |

|

| ||||||

| Q15029 | 116 kDa U5 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein component | 13 | 9 | 12 | RNA Processing/mRNA Splicing | 109438.1 |

| P62081 | 40S ribosomal protein S7 | 32 | 4 | 8 | 22127.5 | |

| P62913 | 60S ribosomal protein L11 | 21 | 4 | 8 | 20253.2 | |

| Q08211 | ATP-dependent RNA helicase A | 8 | 7 | 13 | 140961.5 | |

| Q9NVP1 | ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX18 | 9 | 5 | 11 | 75409.7 | |

| O00148 | ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX39 | 9 | 4 | 6 | 49129.8 | |

| Q9H583 | HEAT repeat-containing protein 1 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 242378.8 | |

| Q32P51 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1-like 2 | 27 | 7 | 17 | 34225.4 | |

| P51991 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A3 | 25 | 8 | 21 | 39595.1 | |

| O60812 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C-like 1 | 29 | 13 | 279 | 32142.7 | |

| P38159 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein G | 22 | 9 | 19 | 42333.7 | |

| P31943 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H | 21 | 6 | 15 | 49229.8 | |

| P31942 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H3 | 16 | 4 | 10 | 36927.6 | |

| P61978 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K | 41 | 12 | 24 | 50978.5 | |

| P14866 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein L | 16 | 6 | 13 | 64132.8 | |

| P52272 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein M | 16 | 9 | 18 | 77517.3 | |

| O60506 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein Q | 15 | 9 | 15 | 69603.5 | |

| Q00839 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U | 37 | 29 | 78 | 90585.2 | |

| P22626 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins A2/B1 | 33 | 10 | 28 | 37430.3 | |

| P07910 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins C1/C2 | 48 | 13 | 739 | 33607.5 | |

| Q9UKD2 | mRNA turnover protein 4 homolog | 51 | 13 | 37 | 27561.3 | |

| P78316 | Nucleolar protein 14 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 97671.9 | |

| O00567 | Nucleolar protein 56 | 24 | 10 | 18 | 66052.0 | |

| Q9NR30 | Nucleolar RNA helicase 2 | 14 | 9 | 13 | 87346.0 | |

| P12270 | Nucleoprotein TPR | 16 | 30 | 52 | 267289.3 | |

| O00541 | Pescadillo homolog | 36 | 19 | 55 | 68004.9 | |

| Q15365 | Poly(rC)-binding protein 1 | 22 | 5 | 8 | 37498.2 | |

| P26599 | Polypyrimidine tract-binding protein 1 | 30 | 9 | 20 | 57222.5 | |

| Q9HCG8 | Pre-mRNA-splicing factor CWC22 homolog | 4 | 4 | 11 | 105470.2 | |

| Q92841 | Probable ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX17 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 72373.0 | |

| P17844 | Probable ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX5 | 13 | 7 | 11 | 69149.7 | |

| P46087 | Putative ribosomal RNA methyltransferase NOP2 | 26 | 18 | 35 | 89303.6 | |

| Q8IY81 | Putative rRNA methyltransferase 3 | 34 | 19 | 40 | 96560.5 | |

| O76021 | Ribosomal L1 domain-containing protein 1 | 18 | 7 | 12 | 54974.7 | |

| Q9NW13 | RNA-binding protein 28 | 18 | 12 | 26 | 85739.1 | |

| Q9UKM9 | RNA-binding protein Raly | 37 | 11 | 22 | 32463.9 | |

| Q15287 | RNA-binding protein with serine-rich domain 1 | 26 | 6 | 30 | 34209.6 | |

| Q9Y3B9 | RRP15-like protein | 17 | 5 | 9 | 31484.5 | |

| Q8IYB3 | Serine/arginine repetitive matrix protein 1 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 102337.5 | |

| Q13435 | Splicing factor 3B subunit 2 | 11 | 9 | 17 | 100229.4 | |

| Q07955 | Splicing factor, arginine/serine-rich 1 | 39 | 9 | 16 | 27745.1 | |

| O75494 | Splicing factor, arginine/serine-rich 10 | 23 | 5 | 10 | 31301.7 | |

| P84103 | Splicing factor, arginine/serine-rich 3 | 29 | 5 | 11 | 19330.0 | |

| Q08170 | Splicing factor, arginine/serine-rich 4 | 14 | 7 | 15 | 56680.0 | |

| Q13243 | Splicing factor, arginine/serine-rich 5 | 19 | 5 | 12 | 31264.8 | |

| Q16629 | Splicing factor, arginine/serine-rich 7 | 15 | 4 | 6 | 27367.5 | |

| P62995 | Transformer-2 protein homolog beta | 17 | 4 | 10 | 33666.7 | |

| P09661 | U2 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein A′ | 28 | 5 | 7 | 28417.1 | |

| O00566 | U3 small nucleolar ribonucleoprotein protein MPP10 | 33 | 15 | 38 | 78866.8 | |

| O75643 | U5 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein 200 kDa helicase | 4 | 6 | 11 | 244513.8 | |

| Q96MU7 | YTH domain-containing protein 1 | 9 | 7 | 12 | 84700.6 | |

|

| ||||||

| P62280 | 40S ribosomal protein S11 | 42 | 8 | 18 | Transcriptional Regulation/Translation | 18431.3 |

| P62277 | 40S ribosomal protein S13 | 30 | 4 | 7 | 17223.3 | |

| P62263 | 40S ribosomal protein S14 | 36 | 4 | 9 | 16272.9 | |

| P62249 | 40S ribosomal protein S16 | 45 | 7 | 14 | 16445.9 | |

| P08708 | 40S ribosomal protein S17 | 55 | 5 | 14 | 15550.5 | |

| P62269 | 40S ribosomal protein S18 | 36 | 6 | 12 | 17719.3 | |

| P15880 | 40S ribosomal protein S2 | 23 | 6 | 10 | 31325.2 | |

| P62266 | 40S ribosomal protein S23 | 34 | 7 | 14 | 15807.7 | |

| P62701 | 40S ribosomal protein S4 | 21 | 5 | 8 | 29599.3 | |

| P46782 | 40S ribosomal protein S5 | 35 | 7 | 11 | 22877.0 | |

| P62241 | 40S ribosomal protein S8 | 42 | 7 | 11 | 24206.4 | |

| P46781 | 40S ribosomal protein S9 | 53 | 13 | 29 | 22592.5 | |

| Q8NHW5 | 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0-like | 18 | 5 | 9 | 34365.1 | |

| Q96L21 | 60S ribosomal protein L10-like | 21 | 5 | 14 | 24519.2 | |

| P30050 | 60S ribosomal protein L12 | 49 | 6 | 10 | 17819.1 | |

| P26373 | 60S ribosomal protein L13 | 33 | 7 | 11 | 24262.2 | |

| P40429 | 60S ribosomal protein L13a | 33 | 12 | 26 | 23577.9 | |

| P50914 | 60S ribosomal protein L14 | 37 | 8 | 22 | 23432.3 | |

| P61313 | 60S ribosomal protein L15 | 39 | 8 | 18 | 24146.5 | |

| P18621 | 60S ribosomal protein L17 | 31 | 5 | 11 | 21397.4 | |

| Q07020 | 60S ribosomal protein L18 | 35 | 6 | 19 | 21635.2 | |

| Q02543 | 60S ribosomal protein L18a | 52 | 10 | 23 | 20762.6 | |

| P84098 | 60S ribosomal protein L19 | 32 | 7 | 24 | 23467.4 | |

| P46778 | 60S ribosomal protein L21 | 34 | 5 | 12 | 18565.0 | |

| P62829 | 60S ribosomal protein L23 | 55 | 7 | 21 | 14865.9 | |

| P62750 | 60S ribosomal protein L23a | 33 | 6 | 14 | 17696.2 | |

| P83731 | 60S ribosomal protein L24 | 41 | 7 | 15 | 17779.5 | |

| P61353 | 60S ribosomal protein L27 | 36 | 4 | 9 | 15798.4 | |

| P46776 | 60S ribosomal protein L27a | 34 | 5 | 10 | 16561.4 | |

| P46779 | 60S ribosomal protein L28 | 49 | 8 | 16 | 15747.9 | |

| P39023 | 60S ribosomal protein L3 | 24 | 9 | 18 | 46109.5 | |

| P62888 | 60S ribosomal protein L30 | 51 | 4 | 9 | 12784.7 | |

| P62910 | 60S ribosomal protein L32 | 35 | 4 | 14 | 15860.4 | |

| P49207 | 60S ribosomal protein L34 | 29 | 5 | 9 | 13293.1 | |

| Q9Y3U8 | 60S ribosomal protein L36 | 35 | 5 | 12 | 12254.2 | |

| P61927 | 60S ribosomal protein L37 | 20 | 4 | 5 | 11078.2 | |

| P61513 | 60S ribosomal protein L37a | 59 | 5 | 12 | 10275.4 | |

| P36578 | 60S ribosomal protein L4 | 36 | 13 | 28 | 47699.1 | |

| P46777 | 60S ribosomal protein L5 | 37 | 9 | 20 | 34363.5 | |

| Q02878 | 60S ribosomal protein L6 | 34 | 10 | 26 | 32729.3 | |

| P18124 | 60S ribosomal protein L7 | 40 | 10 | 22 | 29227.7 | |

| P62424 | 60S ribosomal protein L7a | 40 | 9 | 22 | 29996.3 | |

| P62917 | 60S ribosomal protein L8 | 22 | 6 | 11 | 28024.8 | |

| P32969 | 60S ribosomal protein L9 | 55 | 6 | 17 | 21863.7 | |

| P11387 | DNA topoisomerase 1 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 90729.7 | |

| Q03701 | CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein ζ | 11 | 8 | 14 | 120992.2 | |

| Q13185 | Chromobox protein homolog 3 | 17 | 4 | 7 | 20812.0 | |

| O75367 | Core histone macro-H2A.1 | 28 | 7 | 14 | 39618.9 | |

| O95602 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase I subunit RPA1 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 194814.5 | |

| P68104 | Elongation factor 1-α 1 (EF-1α1) | 27 | 9 | 25 | 50141.2 | |

| P13639 | Elongation factor 2 (EF-2) | 17 | 10 | 24 | 95340.1 | |

| P60842 | Eukaryotic initiation factor 4A-I | 21 | 7 | 12 | 46155.3 | |

| P05198 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 subunit 1 | 27 | 8 | 15 | 36112.7 | |

| P63241 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A-1 | 39 | 4 | 8 | 16832.7 | |

| Q5SSJ5 | Heterochromatin protein 1-binding protein 3 | 16 | 7 | 11 | 61208.7 | |

| Q99729 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A/B | 11 | 4 | 7 | 36225.2 | |

| O14979 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein D-like | 15 | 4 | 8 | 46438.6 | |

| Q14103 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein D0 | 23 | 8 | 15 | 38434.5 | |

| P52926 | High mobility group protein HMGA2 | 58 | 5 | 17 | 11831.9 | |

| Q12905 | Interleukin enhancer-binding factor 2 | 62 | 16 | 80 | 43062.7 | |

| Q12906 | Interleukin enhancer-binding factor 3 | 15 | 12 | 18 | 95338.9 | |

| P43243 | Matrin-3 | 50 | 30 | 107 | 94626.7 | |

| Q9BQG0 | Myb-binding protein 1A | 28 | 31 | 80 | 148858.3 | |

| Q13765 | Nascent polypeptide-associated complex subunit α | 26 | 4 | 7 | 23383.3 | |

| P17480 | Nucleolar transcription factor 1 | 20 | 14 | 33 | 89409.6 | |

| P55209 | Nucleosome assembly protein 1-like 1 | 36 | 8 | 24 | 45375.0 | |

| Q9H307 | Pinin | 37 | 22 | 56 | 81613.2 | |

| P51531 | Probable global transcription activator SNF2L2 | 9 | 10 | 22 | 181283.0 | |

| Q8IZL8 | Proline-, glutamic acid- and leucine-rich protein 1 | 15 | 11 | 22 | 119700.6 | |

| P35659 | Protein DEK | 22 | 8 | 15 | 42675.9 | |

| Q8N7H5 | RNA polymerase II-associated factor 1 homolog | 15 | 6 | 12 | 59976.0 | |

| Q15424 | Scaffold attachment factor B1 | 21 | 14 | 30 | 102642.8 | |

| Q92922 | SWI/SNF complex subunit SMARCC1 | 22 | 18 | 42 | 122867.4 | |

| Q969G3 | SWI/SNF-related matrix-associated actin-dependent regulator of chromatin subfamily E member 1 | 30 | 11 | 29 | 46649.7 | |

| Q9Y2W1 | Thyroid hormone receptor-associated protein 3 | 13 | 12 | 33 | 108668.9 | |

| P51532 | Transcription activator BRG1 | 11 | 14 | 28 | 184649.6 | |

| Q5BKZ1 | Zinc finger protein 326 | 33 | 14 | 34 | 65653.5 | |

|

| ||||||

| Q9NVI7 | ATPase family AAA domain-containing protein 3A | 7 | 4 | 6 | unknown | 71370.2 |

| P55081 | Microfibrillar-associated protein 1 | 17 | 5 | 10 | 51958.7 | |

| Q9Y3T9 | Nucleolar complex protein 2 homolog | 30 | 19 | 70 | 84907.1 | |

| O94880 | PHD finger protein 14 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 100055.1 | |

| Q96GQ7 | Probable ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX27 | 17 | 12 | 20 | 89838.1 | |

| Q9H0S4 | Probable ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX47 | 11 | 4 | 9 | 50648.4 | |

| Q9Y4W2 | Protein LAS1 homolog | 22 | 13 | 28 | 83065.5 | |

| Q9BXY0 | Protein MAK16 homolog | 50 | 12 | 30 | 35370.0 | |

| Q5JTH9 | RRP12-like protein | 5 | 4 | 6 | 143705.1 | |

| Q15061 | WD repeat-containing protein 43 | 37 | 20 | 106 | 74890.8 | |

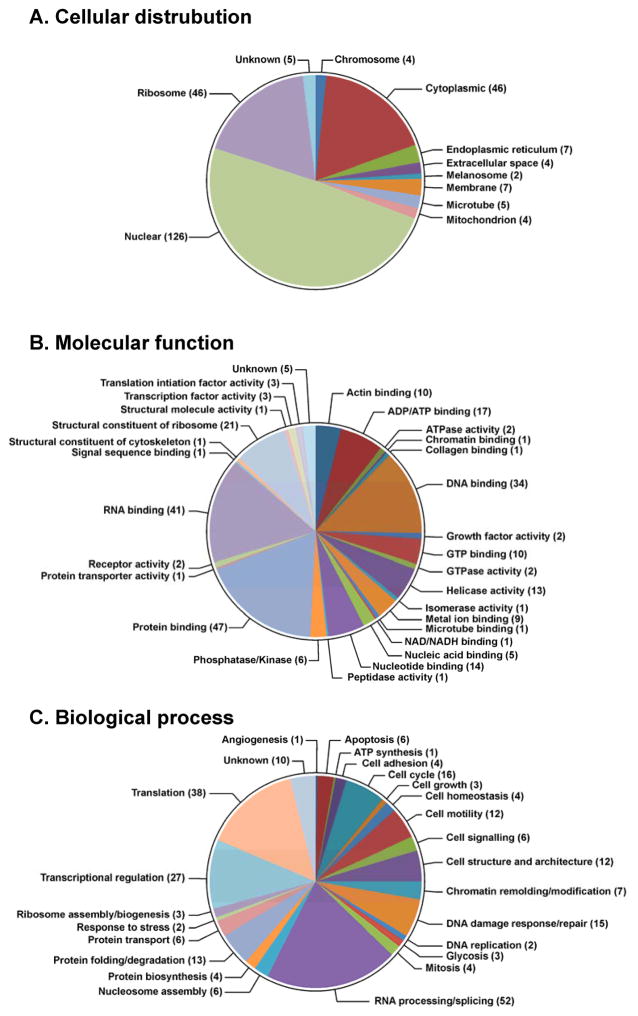

Of the identified proteins listed in Table 1, 126 (49.0%) are classified as nuclear proteins by the GO database available via the European Bioinformatics Institute (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/QuickGO) (Figure 4A). These include high mobility group (HMG) proteins, histone proteins, and elongation factors. This is not unexpected considering that nuclear proteins are either localized in the vicinity of DNA or are directly associated with DNA, increasing their chance to be cross-linked to DNA in the presence of cisplatin. An additional 46 proteins (17.9%) were classified as cytoplasmic, 46 (17.9%) as ribosomal proteins, and 7 (2.7%) as membrane-bound proteins (Figure 3A). It is important to note that many of the identified proteins participate in multiple biological processes, and are subsequently categorized under multiple cellular locations. For example, the 40S ribosomal protein S6,39–41 40S ribosomal protein S7,39 40S ribosomal S9,39,42 60S ribosomal protein L10-like,39 60S ribosomal protein L13a,39,43 and 60S ribosomal protein L23a43,44 have been identified in both the cytoplasm and nucleus of different human cells. DPC-forming proteins were further classified according to their GO annotations relating to their molecular function (Figure 4B) and their participation in biological processes (Figure 4C). We found that the majority of the identified proteins belong to the following three categories: DNA binding (34, or 13.2%), RNA binding (41, or 16.0%), and protein binding (47, or 18.3%) (Table 1 and Figure 4B). Interestingly, 52 of the identified proteins (20.2%) have been reported to play a role in RNA processing or splicing (Figure 4C), including arginine/serine-rich splicing factors, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins, and ATP-dependent RNA helicases. An additional 10.5% of proteins (N=27) are involved in transcriptional regulation, including transcription activator BRG 1, matrin-3, and interleukin enhancer-binding factors (Figure 4C and Table 1). This result is not due to RNA contamination as DNA isolated by our phenol/chloroform methodology has minimal RNA contamination as revealed by HPLC-UV analyses of enzymatic digests (see Figure S2).6 More likely, in addition to their binding to RNA, these proteins may possess additional DNA-binding capabilities which may be triggered by cisplatin treatment.

Figure 4.

GO annotations for proteins involved in cisplatin-induced DPC formation in human HT1080 cells: cellular distributions (A), molecular functions (B), and biological processes (C). The numbers of proteins in each category is indicated in parentheses.

Western blot analysis of cross-linked proteins

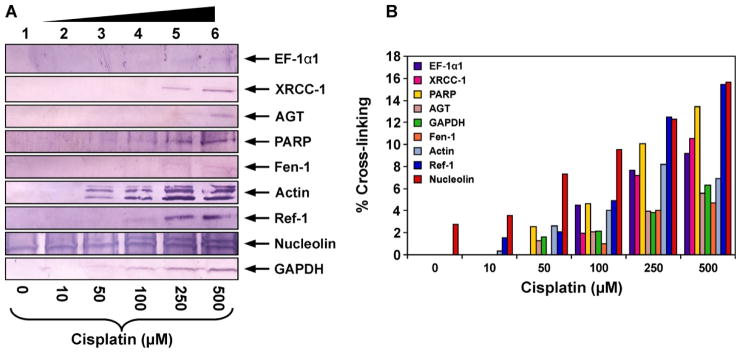

To confirm the results of mass spectrometry analyses and to discover additional proteins participating in DPC formation, proteins co-purified with chromosomal DNA following cisplatin treatment were subjected to western blot analysis using commercial antibodies against EF-1α1, PARP, Ref-1, nucleolin, actin, GAPDH, Fen-1, AGT, and XRCC-1 (Figure 5). These proteins were selected because they were either among the gene products identified by mass spectrometry analyses (EF-1α1, PARP, GAPDH, nucleolin, and actin, Table 1) or have been previously found to form cisplatin-induced DPCs in our earlier studies employing cell free protein extracts (Ref-1, AGT, Fen-1, and XRCC-1).5,45 Equal amounts (30 μg) of DNA isolated from cisplatin-treated HT1080 cells (10, 50, 100, 250, or 500 μM) were taken and heated with SDS-containing gel loading buffer (1 h at 70°C) to release the proteins (Scheme 2). The resulting proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for western blot analysis using the specific antibodies mentioned above.

Figure 5.

Western blot analysis of cisplatin-induced DPCs in HT1080 cells. Following treatment with 0 (lane 1), 10 (lane 2), 50 (lane 3), 100 (lane 4), 250 (lane 5), or 500 μM cisplatin (lane 6), DNA and cross-linked proteins were isolated by phenol/chloroform extraction. Samples were normalized for DNA content, proteins from 30 μg DNA were released by thermal hydrolysis, separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Western blotting was performed using primary antibodies specific for EF-1α1, AGT, Fen-1, nucleolin, actin, GAPDH, PARP, Ref-1, andXRCC-1 (A). The efficiency of DPC formation in the presence of cisplatin was estimated by densitometric analysis of protein bands in DPC samples and a whole cell protein lysate control (B).

Western blotting experiments confirmed the identities of five gene products identified from mass spectrometry based proteomics: EF-1α1, PARP, nucleolin, GAPDH, and actin (Figure 5A). In addition, a concentration-dependent DPC formation involving four additional proteins: Ref-1, AGT, Fen-1 and XRCC-1, was observed. Among these, nucleolin displayed the greatest cross-linking efficiency, with approximately 10 % of total protein becoming cross-linked to DNA following treatment with 100 μM cisplatin (Figure 5B).

HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS Analysis of dG-Pt-Lys Conjugates as Evidence for DPC Formation

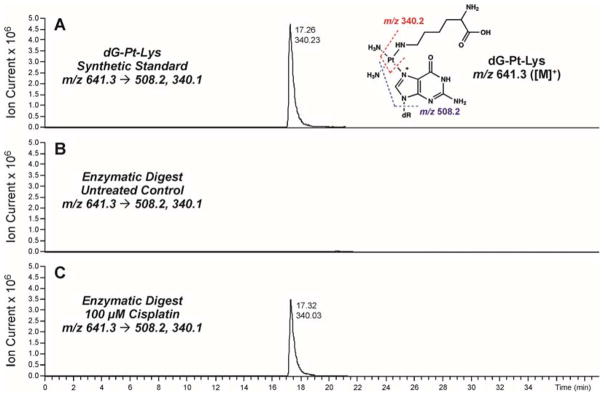

To confirm the formation of covalent DNA-protein conjugates in cisplatin-treated cells, HT1080 cells (~106) were treated with 0 or 100 μM cisplatin, and DPC-containing chromosomal DNA was extracted as described above. Equal DNA amounts were taken from each sample and subjected to enzymatic hydrolysis to yield protein-nucleoside conjugates from the DNA backbone, followed by enzymatic digestion to amino acids in the presence of trypsin and proteinase K. Following offline HPLC enrichment, HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS was used to detect covalent cisplatin-induced lysine-guanine conjugates (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS analysis of dG-Pt-Lys conjugates in total proteolytic digests of chromosomal DNA recovered from cisplatin-treated cells. HT1080 cells were treated with 100 μM cisplatin for 3 h to induce DNA-protein cross-links. Following extraction of the chromosomal DNA containing covalent DPCs, the cross-linked proteins were subjected to enzymatic hydrolysis to release amino acid-nucleobase conjugates. Synthetic dG-Pt-Lys (A); enzymatic digests of DPC mixtures from HT1080 cells incubated in the absence of cisplatin (B); enzymatic digests of DPC mixtures treated with 100 μM cisplatin (C).

Representative extracted ion chromatograms for HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS analysis of dG-Pt-Lys in samples from cisplatin-treated and control HT1080 cells are shown in Figure 5. dG-Pt-Lys was detected in DNA samples from cisplatin-treated cells (Figure 6C), but not in untreated cells (Figure 6B). This conjugate had the same HPLC retention time and the same MS/MS fragmentation pattern as synthetic dG-Pt-Lys standard (Figure 6A). These data indicate that cisplatin-induced DNA-protein cross-linking can take place between the N7 position of guanine in DNA and the side-chain ε-amino group of lysine in proteins, although we cannot exclude the possibility of additional cross-linking via other nucleophilic amino acid side chains such as cysteine, histidine, glutamic acid, and arginine. Our efforts to prepare the corresponding dG-Pt-Cys conjugates were unsuccessful due to their limited stability (results not shown).

Discussion

Previous studies using biophysical methods25–29 and immunological detection with specific antibodies28 have shown that cisplatin and other platinum compounds are capable of inducing DNA-protein cross-links. These lesions are formed by consecutive platination of proteins and DNA by platinum drugs (Scheme 1). However, to our knowledge, there has been no previous system-wide investigation of the proteins participating in DPC formation in the presence of cisplatin. In the present work, we employed an unbiased mass spectrometry-based approach to identify human proteins that form DPCs in cisplatin treated cells (Scheme 2). We took advantage of a modified phenol/chloroform methodology developed in our laboratory to isolate DPCs from cisplatin-treated cells.6 Following extraction, the cross-linked proteins were released from DNA strands by heating. We have previously shown that under these conditions, proteins cross-linked to DNA via platination are displaced by proximal nucleobases on genomic DNA. This forms DNA-DNA cross-links and releases intact proteins, which can be readily identified by mass spectrometry-based proteomics and immunoblotting (Scheme 2).

We found that human fibrosarcoma HT1080 cells treated with pharmacologically relevant concentrations of cisplatin (100 μM) contained DNA-protein cross-links to 256 cellular proteins. Recent studies have measured free cisplatin levels at a concentration of 9.03 μg/mL (~30 μM) after a three hour treatment period of 100 μg/m2.46 The proteins identified by the mass spectrometry-based proteomics study as being trapped on DNA in the presence of cisplatin (Table 1) participate in a variety of cellular functions including DNA damage response and repair (e.g. HMG proteins, histone proteins, PARP-1, and XRCC proteins), transcriptional regulation (e.g. CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein ζ, Chromobox protein homolog 3, and matrin-3), RNA processing (e.g. ATP-dependent RNA helicase, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins, poly(rC)-binding protein 1, and putative rRNA methyltransferase 3), cell signaling and architecture (e.g. actin, keratin, lamin, and vimentin), and regulation of cell cycle (e.g. GAPDH, nucleolin, nucleophosmin, and T-complex proteins). The majority of the identified proteins are known DNA-binding proteins (e.g. HMG proteins, histone proteins, PARP-1, and XRCC), RNA-binding proteins (e.g. heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins, 40S ribosomal proteins, 60S ribosomal proteins, and arginine/serine-rich splicing factors), and protein-binding proteins (e.g. keratin, lamin, vimentin, and galectin-1) which are present in the nucleus (Figure 4C).

Previous targeted studies employed antibodies against specific proteins have shown that several DNA-binding proteins including HMG 1, 2, and E, cytokeratins, and histones can become cross-linked to DNA in the presence of cisplatin.28 These proteins were also detected in our unbiased proteomics screen of cisplatin-induced DPCs (Table 1). In addition, our system-wide investigation established the identities of many additional nuclear proteins that participate in DNA-protein cross-linking formation in the presence of cisplatin (Table 1) and determined atomic connectivity of the resulting macromolecular conjugates to be between the N7 position of guanine and the ε-amino group of lysine (Figure 6).

Among the proteins identified in the present work (Table 1), 21 proteins (55.2% of all meclorethamine-induced DPCs) were present in both mechlorethamine and cisplatin-treated HT1080 cells.6 These proteins included the transcription regulators matrin-3, nucleolar transcription factor 1, and nucleophosmin.6 Similarly, 106 proteins (79.1% of all phosphoramide mustard-induced DPCs) were present in both phosphoramide mustard and cisplatin treated HT1080 cells.47 The differences in protein targets of cisplatin and nitrogen mustards may result from differences in the respective cross-linking mechanisms associated with DNA/protein platination and alkylation. Furthermore, cisplatin’s ability to react with the lysine, cysteine, and histidine residues of proteins can explain why cisplatin formed DPCs with a greater efficiency than mechlorethamine and phosphoramide mustard and cross-linked a wider range of protein targets.

While the contributions of DNA-protein cross-linking to the biological activity of cisplatin remains to be established, these bulky lesions are expected to block DNA replication, transcription, and repair. We recently reported that proteins conjugated to the N7 position of guanine completely block DNA replication.13 The corresponding DNA-peptide conjugates that would form upon proteolytic degradation of DPCs can be bypassed by human translesion synthesis polymerases η and κ with a relatively low efficiency, but with high fidelity.13 The yeast metalloprotease Wss1 has been identified as the protease which cleaves the protein constituent of DPC at blocked replisomes.48 Recently, the metalloprotease SPRTN has been identified by several laboratories as the mammalian protease responsible for cleaving DPCs at blocked replication forks.49–51

Cellular repair pathways responsible for the removal of cisplatin-induced DPCs are the subject of intense investigation. It has been proposed that DPCs formed as a consequence of cellular exposure to bifunctional alkylating agents (i.e. formaldehyde) can be repaired by NER,52 homologous recombination (HR),53 and proteolytic degradation.54 One possible mechanism includes proteolytic degradation of the protein component of DPCs, followed by NER removal of the resulting DNA-peptide lesions.10 A number of reports are consistent with this hypothesis.55–57 For example, Reardon and Sancar have shown that 4mer and 12mer peptide-DNA substrates can be excised by nucleotide excision repair in-vitro.55 Nakano et al reported that DPCs containing protein constituents smaller than 8 kDa are directly excised by NER in-vitro.53 Similarly, Baker et al56 presented evidence that DNA-peptide cross-links were excised by cell free extracts from mammalian cells substantially more efficiently than DNA-protein cross-links.

Conversely, other recent reports suggest that mammalian DPC repair may occur via a pathway(s) distinct from NER. For instance, recent papers provide evidence for a role for homologous recombination in DPC repair.53,58 Nakano et al failed to detect differences in the kinetics of removal of formaldehyde-induced DPCs when NER-proficient and NER-deficient cells were compared.53 Instead, these authors observed that clones deficient in homologous recombination genes displayed greater hypersensitivity to formaldehyde-induced death than did clones deficient in NER genes.53 Furthermore, a study by Chvalova and colleagues59 observed the failure of human NER system to remove proteins cross-linked to DNA by cisplatin, suggesting that another pathway may be important. These discrepancies may indicate that DPC structures and protein identities may affect their repair mechanism, and more than one repair pathway may be required.10,60 Further studies involving site-specific cisplatin-induced lesions are needed to determine the mechanisms of their repair and their effects on DNA replication.

In conclusion, the present system-wide study demonstrates that DNA-protein cross-links involving a variety of cellular proteins are formed in human fibrosarcoma-derived HT1080 cells following exposure to clinically relevant concentrations of cisplatin.61 In our experiments, cisplatin was able to cross-link over 250 proteins to chromosomal DNA. Proteins were identified by mass spectrometry-based proteomics, and the identities of several proteins were confirmed by immunological detection. Many of the identified proteins are involved in a variety of cellular processes such as chromatin remodeling, translation, DNA replication, DNA damage response, DNA repair, RNA processing, and transcriptional regulation. If not repaired, these bulky DPC lesions are expected to cause chromosomal double-strand breaks or be misread by DNA polymerases to generate mutations, ultimately triggering programmed cell death or genotoxic outcomes. Ongoing studies with site-specific modified plasmids introduced in mammalian cells with different repair backgrounds are currently underway in our laboratory to obtain additional details on the consequences of DPCs induced by antitumor platinum agents in human cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding information:

Funding for this research was provided by the National Cancer Institute (CA1006700), the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (ES023350), and a faculty development grant from the University of Minnesota Academic Health Center. E.M.R. was partially supported by the NIH Chemistry-Biology Interface Training Grant (T32-GM08700), University of Minnesota Masonic Cancer Center, and University of Minnesota Graduate School.

We thank Brock Matter (Masonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota) for his assistance with MS experiments, Dr. Pratik Jagtap (Minnesota Supercomputing Institute, University of Minnesota) for his help with proteomic data analyses, and Bob Carlson for preparing figures for this manuscript. Mass spectrometry was carried out in the Analytical Biochemistry Shared Resource of the Masonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota, funded in part by Cancer Center Support Grant CA-077598 and S10 RR-024618 (Shared Instrumentation Grant).

List of Abbreviations

- Cisplatin

cis-1,1,2,2-diamminedichloroplatinum (II)

- dG-Pt-Cl

cis-1,1-diammine-2-chloro-2-(2′-deoxyguanosine-7-yl)-platinum (II)

- dG-Pt-dG

cis-1,1-diammine-2,2-bis-(deoxyguanosine-7-yl)-platinum (II)

- dG-Pt-Lys

cis-1,1-diammine-2-(5-amino-5-carboxypentyl)amino-2-(2′-deoxyguanosine-7-yl)-platinum(II)

- DEB

1,2,3,4-diepoxybutane

- mechlorethamine

bis(2-chloroethyl)methylamine

- DPC

DNA-protein cross-link

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- FDR

false discovery rate

- GSH

glutathione

- HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS

high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry

- PMSF

phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride

- PARP-1

poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase I

- AGT

O6-alkylguanine DNA alkyltansferase

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- Ref-1

DNA-(apurinic- or apyrimidinic-site) lyase

- XRCC-1

x-ray cross-complementing protein I

- Fen-1

flap endonuclease 1

- EF 1α1

elongation factor 1α1

- HMG

high mobility group protein

- DNase I

deoxyribonuclease I

- PDE I

phosphodiesterase I

- PDE II

phosphodiesterase II

- HR

homologous recombination

- NER

nucleotide excision repair

- SRM

selected reaction monitoring

- TIC

total ion current

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- TBS

tris-buffered saline

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

Footnotes

Cytotoxicity of HT1080 cells to cisplatin, representative trace of enzymatically digested DNA for quantitation. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Reference List

- 1.Barker S, Weinfeld M, Zheng J, Li L, Murray D. Identification of mammalian proteins cross-linked to DNA by ionizing radiation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33826–33838. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502477200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhitkovich A, Voitkun V, Kluz T, Costa M. Utilization of DNA-protein cross-links as a biomarker of chromium exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106(Suppl 4):969–974. doi: 10.1289/ehp.98106s4969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas CB, Kohn KW, Bonner WM. Characterization of DNA-protein cross-links formed by treatment of L1210 cells and nuclei with bis(2-chloroethyl)methylamine (nitrogen mustard) Biochemistry. 1978;17:3954–3958. doi: 10.1021/bi00612a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker JM, Parish JH, Curtis JP. DNA-DNA and DNA-protein cross-linking and repair in Neurospora crassa following exposure to nitrogen mustard. Mutat Res. 1984;132:171–179. doi: 10.1016/0167-8817(84)90035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loeber RL, Michaelson-Richie ED, Codreanu SG, Liebler DC, Campbell CR, Tretyakova NY. Proteomic analysis of DNA-protein cross-linking by antitumor nitrogen mustards. Chem Res Toxicol. 2009;22:1151–1162. doi: 10.1021/tx900078y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michaelson-Richie ED, Ming X, Codreanu SG, Loeber RL, Liebler DC, Campbell C, Tretyakova NY. Mechlorethamine-induced DNA-protein cross-linking in human fibrosarcoma (HT1080) cells. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:2785–2796. doi: 10.1021/pr200042u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groehler A, Villalta PW, Campbell C, Tretyakova N. Covalent DNA-Protein Cross-Linking by Phosphoramide Mustard and Nornitrogen Mustard in Human Cells. Chem Res Toxicol. 2016;29:190–202. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.5b00430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kloster M, Kostrhunova H, Zaludova R, Malina J, Kasparkova J, Brabec V, Farrell N. Trifunctional dinuclear platinum complexes as DNA-protein cross-linking agents. Biochemistry. 2004;43:7776–7786. doi: 10.1021/bi030243e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ewig RA, Kohn KW. DNA-protein cross-linking and DNA interstrand cross-linking by haloethylnitrosoureas in L1210 cells. Cancer Res. 1978;38:3197–3203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barker S, Weinfeld M, Murray D. DNA-protein cross-links: their induction, repair, and biological consequences. Mutat Res. 2005;589:111–135. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oleinick NL, Chiu SM, Ramakrishnan N, Xue LY. The formation, identification, and significance of DNA-protein cross-links in mammalian cells. Br J Cancer Suppl. 1987;8:135–140. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wickramaratne S, Boldry EJ, Buehler C, Wang YC, Distefano MD, Tretyakova NY. Error-prone translesion synthesis past DNA-peptide cross-links conjugated to the major groove of DNA via C5 of thymidine. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:775–787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.613638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wickramaratne S, Ji S, Mukherjee S, Su Y, Pence MG, Lior-Hoffmann L, Fu I, Broyde S, Guengerich FP, Distefano M, Scharer OD, Sham YY, Tretyakova N. Bypass of DNA-Protein Cross-links Conjugated to the 7-Deazaguanine Position of DNA by Translesion Synthesis Polymerases. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:23589–23603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.745257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tretyakova NY, Michaelson-Richie ED, Gherezghiher TB, Kurtz J, Ming X, Wickramaratne S, Campion M, Kanugula S, Pegg AE, Campbell C. DNA-reactive protein monoepoxides induce cell death and mutagenesis in mammalian cells. Biochemistry. 2013;52:3171–3181. doi: 10.1021/bi400273m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bosl GJ, Bajorin DF, Sheinfeld J, Motzer R. Cancer of the testis. 6. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boulikas T, Vougiouka M. Recent clinical trials using cisplatin, carboplatin and their combination chemotherapy drugs (review) Oncol Rep. 2004;11:559–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller SE, House DA. The hydrolysis products of cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II) Inorganica Chimica Acta. 1991;187:125–132. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jamieson ER, Lippard SJ. Structure, recognition, and processing of cisplatin-DNA adducts. Chemical Reviews. 1999;99:2467–2498. doi: 10.1021/cr980421n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jung YW, Lippard SJ. Direct cellular responses to platinum-induced DNA damage. Chemical Reviews. 2007;107:1387–1407. doi: 10.1021/cr068207j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sherman SE, Lippard SJ. Structural aspects of platinum anticancer drug-interactions with DNA. Chemical Reviews. 1987;87:1153–1181. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wozniak K, Walter Z. Induction of DNA-protein cross-links by platinum compounds. Zeitschrift fur Naturforschung C-A Journal of Biosciences. 2000;55:731–736. doi: 10.1515/znc-2000-9-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jamieson ER, Lippard SJ. Structure, recognition, and processing of cisplatin-DNA adducts. Chemical Reviews. 1999;99:2467–2498. doi: 10.1021/cr980421n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jung YW, Lippard SJ. Direct cellular responses to platinum-induced DNA damage. Chemical Reviews. 2007;107:1387–1407. doi: 10.1021/cr068207j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barry MA, Behnke CA, Eastman A. Activation of programmed cell-death (apoptosis) by cisplatin, other cnticancer drugs, toxins and hyperthermia. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1990;40:2353–2362. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90733-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zwelling LA, Anderson T, Kohn KW. DNA-protein and DNA interstrand cross-linking by cis-platinum(II) and trans-platinum(II) diamminedichloride in L1210 mouse leukemia-cells and relation to cytotoxicity. Cancer Research. 1979;39:365–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lippard SJ, Hoeschele JD. Binding of cis-dichlorodiammineplatinum(II) and trans-dichlorodiammineplatinum(II) to the nucleosome core. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:6091–6095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.12.6091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banjar ZM, Hnilica LS, Briggs RC, Stein J, Stein G. Cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II) and trans-diamminedichloroplatinum(II)-mediated cross-linking of chromosomal non-histone proteins to DNA in Hela cells. Biochemistry. 1984;23:1921–1926. doi: 10.1021/bi00304a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olinski R, Wedrychowski A, Schmidt WN, Briggs RC, Hnilica LS. In vivo DNA-protein cross-linking by cis- and trans-diamminedichloroplatinum(II) Cancer Res. 1987;47:201–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamamoto J, Miyagi Y, Kawanishi K, Yamada S, Miyagi Y, Kodama J, Yoshinouchi M, Kudo T. Effect of cisplatin on cell death and DNA crosslinking in rat mammary adenocarcinoma in vitro. Acta Med Okayama. 1999;53:201–208. doi: 10.18926/AMO/31616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rasheed S, Nelson-Rees WA, Toth EM, Arnstein P, Gardner MB. Characterization of a newly derived human sarcoma cell line (HT-1080) Cancer. 1974;33:1027–1033. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197404)33:4<1027::aid-cncr2820330419>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gherezghiher TB, Ming X, Villalta PW, Campbell C, Tretyakova NY. 1,2,3,4-Diepoxybutane-induced DNA-protein cross-linking in human fibrosarcoma (HT1080) cells. J Proteome Res. 2013;12:2151–2164. doi: 10.1021/pr3011974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tretyakova NY, Groehler A, Ji S. DNA-Protein Cross-Links: Formation, Structural Identities, and Biological Outcomes. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48:1631–1644. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shin NY, Liu Q, Stamer SL, Liebler DC. Protein targets of reactive electrophiles in human liver microsomes. Chem Res Toxicol. 2007;20:859–867. doi: 10.1021/tx700031r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yates JR, III, Eng JK, McCormack AL. Mining genomes: correlating tandem mass spectra of modified and unmodified peptides to sequences in nucleotide databases. Anal Chem. 1995;67:3202–3210. doi: 10.1021/ac00114a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yates JR, III, Eng JK, McCormack AL, Schieltz D. Method to correlate tandem mass spectra of modified peptides to amino acid sequences in the protein database. Anal Chem. 1995;67:1426–1436. doi: 10.1021/ac00104a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keller A, Nesvizhskii AI, Kolker E, Aebersold R. Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Anal Chem. 2002;74:5383–5392. doi: 10.1021/ac025747h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang B, Chambers MC, Tabb DL. Proteomic parsimony through bipartite graph analysis improves accuracy and transparency. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:3549–3557. doi: 10.1021/pr070230d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shin NY, Liu Q, Stamer SL, Liebler DC. Protein targets of reactive electrophiles in human liver microsomes. Chem Res Toxicol. 2007;20:859–867. doi: 10.1021/tx700031r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Mateo S, Castillo J, Estanyol JM, Ballesca JL, Oliva R. Proteomic characterization of the human sperm nucleus. Proteomics. 2011;11:2714–2726. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmidt C, Lipsius E, Kruppa J. Nuclear and nucleolar targeting of human ribosomal protein S6. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:1875–1885. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.12.1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Macfarlane DE, Gailani D. Identification of phosphoprotein NP33 as a nucleus-associated ribosomal S6 protein and its phosphorylation in hematopoietic cells. Cancer Res. 1990;50:2895–2900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lindstrom MS, Zhang Y. Ribosomal protein S9 is a novel B23/NPM-binding protein required for normal cell proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15568–15576. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801151200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sigal A, Milo R, Cohen A, Geva-Zatorsky N, Klein Y, Alaluf I, Swerdlin N, Perzov N, Danon T, Liron Y, Raveh T, Carpenter AE, Lahav G, Alon U. Dynamic proteomics in individual human cells uncovers widespread cell-cycle dependence of nuclear proteins. Nat Methods. 2006;3:525–531. doi: 10.1038/nmeth892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jakel S, Gorlich D. Importin beta, transportin, RanBP5 and RanBP7 mediate nuclear import of ribosomal proteins in mammalian cells. EMBO J. 1998;17:4491–4502. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.15.4491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Michaelson-Richie ED, Loeber RL, Codreanu SG, Ming X, Liebler DC, Campbell C, Tretyakova NY. DNA-protein cross-linking by 1,2,3,4-diepoxybutane. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:4356–4367. doi: 10.1021/pr1000835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rajkumar P, Mathew BS, Das S, Isaiah R, John S, Prabha R, Fleming DH. Cisplatin Concentrations in Long and Short Duration Infusion: Implications for the Optimal Time of Radiation Delivery. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:XC01–XC04. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/18181.8126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Groehler A, Degner A, Tretyakova NY. Mass Spectrometry Based Tools to Characterize DNA-Protein Cross-Linking by Bis-electrophiles. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2016 doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stingele J, Schwarz MS, Bloemeke N, Wolf PG, Jentsch S. A DNA-dependent protease involved in DNA-protein crosslink repair. Cell. 2014;158:327–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vaz B, Popovic M, Newman JA, Fielden J, Aitkenhead H, Halder S, Singh AN, Vendrell I, Fischer R, Torrecilla I, Drobnitzky N, Freire R, Amor DJ, Lockhart PJ, Kessler BM, McKenna GW, Gileadi O, Ramadan K. Metalloprotease SPRTN/DVC1 Orchestrates Replication-Coupled DNA-Protein Crosslink Repair. Mol Cell. 2016;64:704–719. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stingele J, Bellelli R, Alte F, Hewitt G, Sarek G, Maslen SL, Tsutakawa SE, Borg A, Kjaer S, Tainer JA, Skehel JM, Groll M, Boulton SJ. Mechanism and Regulation of DNA-Protein Crosslink Repair by the DNA-Dependent Metalloprotease SPRTN. Mol Cell. 2016;64:688–703. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morocz M, Zsigmond E, Toth R, Enyedi MZ, Pinter L, Haracska L. DNA-dependent protease activity of human Spartan facilitates replication of DNA-protein crosslink-containing DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakano T, Morishita S, Katafuchi A, Matsubara M, Horikawa Y, Terato H, Salem AM, Izumi S, Pack SP, Makino K, Ide H. Nucleotide excision repair and homologous recombination systems commit differentially to the repair of DNA-protein cross-links. Mol Cell. 2007;28:147–158. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nakano T, Katafuchi A, Matsubara M, Terato H, Tsuboi T, Masuda T, Tatsumoto T, Pack SP, Makino K, Croteau DL, Van Houten B, Iijima K, Tauchi H, Ide H. Homologous recombination but not nucleotide excision repair plays a pivotal role in tolerance of DNA-protein cross-links in mammalian cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284:27065–27076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.019174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Quievryn G, Zhitkovich A. Loss of DNA-protein cross-links from formaldehyde-exposed cells occurs through spontaneous hydrolysis and an active repair process linked to proteosome function. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1573–1580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reardon JT, Sancar A. Repair of DNA-polypeptide crosslinks by human excision nuclease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4056–4061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600538103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baker DJ, Wuenschell G, Xia L, Termini J, Bates SE, Riggs AD, O’Connor TR. Nucleotide excision repair eliminates unique DNA-protein cross-links from mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:22592–22604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702856200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Duxin JP, Dewar JM, Yardimci H, Walter JC. Repair of a DNA-protein crosslink by replication-coupled proteolysis. Cell. 2014;159:346–357. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chvalova K, Brabec V, Kasparkova J. Mechanism of the formation of DNA-protein cross-links by antitumor cisplatin. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:1812–1821. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]