Abstract

To enlarge the germplasm resource of Paulownia plants, we used colchicine to induce autotetraploid Paulownia tomentosa, as reported previously. Compared with its diploid progenitor, autotetraploid P. tomentosa exhibits better photosynthetic characteristics and higher stress resistance. However, the underlying mechanism for its predominant characteristics has not been determined at the proteome level. In this study, isobaric tag for relative and absolute quantitation coupled with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry was employed to compare proteomic changes between autotetraploid and diploid P. tomentosa. A total of 1427 proteins were identified in our study, of which 130 proteins were differentially expressed between autotetraploid and diploid P. tomentosa. Functional analysis of differentially expressed proteins revealed that photosynthesis-related proteins and stress-responsive proteins were significantly enriched among the differentially expressed proteins, suggesting they may be responsible for the photosynthetic characteristics and stress adaptability of autotetraploid P. tomentosa. The correlation analysis between transcriptome and proteome data revealed that only 15 (11.5%) of the differentially expressed proteins had corresponding differentially expressed unigenes between diploid and autotetraploid P. tomentosa. These results indicated that there was a limited correlation between the differentially expressed proteins and the previously reported differentially expressed unigenes. This work provides new clues to better understand the superior traits in autotetraploid P. tomentosa and lays a theoretical foundation for developing Paulownia breeding strategies in the future.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12298-017-0447-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Paulownia tomentosa, Autotetraploid, Superior traits, Proteomics, iTRAQ

Introduction

Paulownia is a fast-growing deciduous ligneous plant indigenous to China where it is cultivated widely, and has also been introduced into many other countries (Zhu et al. 1986). Because of its good properties, such as short rotation, high-quality wood, high biomass, pollution tolerance and attractive flowers, Paulownia is versatile for fodder, paper industry, pencil manufacturing, house construction, furniture making, solid biofuel, forestation and ornamental plant (Zhu et al. 1986; Ates et al. 2008; López et al. 2012; Kaygin et al. 2015).

Polyploidy is a remarkably pervasive phenomenon in eukaryotes, especially in angiosperms (Leitch and Bennett 1997; Comai 2005). Most extant plants have undergone ancient polyploidization events or recent genome duplication events which has been regarded as a great force in the long-term diversification and evolution of flowering plants (Adams and Wendel 2005). According to the chromosomal composition and manner of formation, polyploids can be divided into three types: autopolyploids (duplications of one chromosome set), allopolyploids (mergers of two or more structurally divergent chromosome sets) and segmental allopolyploids (an intermediate condition between auto- and allopolyploids) (Yoo et al. 2014). In addition to creating gene redundancy, polyploidization can also evoke nuclear enlargement, chromosomal rearrangement, epigenetic remodeling and organ-specific subfunctionalization of gene expression, resulting in restructuring of the transcriptome, metabolome, and proteome (Leitch and Leitch 2008). Compared with their diploid progenitors, polyploids are generally more vigorous and adaptive, and can survive better in harsh environments (Comai 2005). Polyploids often exhibit novel useful traits such as asexual reproduction, flowering phenology, increased adversity tolerance, increased disease and pest resistance, and increased organ size and biomass, making polyploids significant in plant breeding (Osborn et al. 2003; Chen 2007). To enrich the germplasm resources of Paulownia plants, autotetraploid Paulownia tomentosa was induced by colchicine using the leaves of diploid P. tomentosa (Fan et al. 2007). Besides differences in morphology and ultrastructure, autotetraploid P. tomentosa exhibits better photosynthetic characteristics and higher stress tolerance than its diploid parent (Zhang et al. 2012, 2013; Deng et al. 2013; Dong et al. 2014a). Recently, Fan et al. (2014, 2015a) revealed the differences in gene expression between diploid and autotetraploid P. tomentosa using high-throughput sequencing. However, information about changes in protein profiles between autotetraploid P. tomentosa and its diploid parent is still undetermined. Proteomics is necessarily complementary to transcriptome, because proteins are the final gene products and the direct executors of biological function (Koh et al. 2012). Besides, there is no strict linear relationship between mRNAs and proteins (Gygi et al. 1999), because post-transcriptional regulations and post-translational modifications (e.g. glycosylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination etc.) have great influence on the proteome (Alam et al. 2010), making it difficult to predict protein expression through transcriptional level analysis. Therefore, investigation of proteome changes between diploid and autotetraploid P. tomentosa using proteomic approaches is imperative to better understand the superior characteristics observed in autotetraploid P. tomentosa. Hitherto, only a few studies have examined proteome changes in polyploids compared with their progenitors, including those of allohexaploid Triticum aestivum (Islam et al. 2003), autopolyploid Brassica oleracea (Albertin et al. 2005), allopolyploid Tragopogon mirus (Koh et al. 2012), Arabidopsis polyploids (Ng et al. 2012), tetraploid Robinia pseudoacacia (Wang et al. 2013) and autotetraploid Manihot esculenta (An et al. 2014). However, most of these studies used two-dimensional electrophoresis, which made it difficult to automate and resolve hydrophobic proteins and proteins with low abundance, extreme isoelectric point or molecular mass (Rabilloud 2002; Gilmore and Washburn 2010). Isobaric tag for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ) combined with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS), which can identify and quantify proteins from multiple samples simultaneously (Wiese et al. 2007), has been widely applied to many proteomic researches recently (Yang et al. 2013; Fan et al. 2015b; Wang et al. 2015a, b).

In the present study, we carried out a comparative proteomic analysis of autotetraploid P. tomentosa and its diploid parent using iTRAQ-based proteomic methods to reveal the proteins associated with the superior characteristics of autotetraploid P. tomentosa (Fig. S1). In addition, we also investigate the correlation between transcriptome and proteome. Our results may help to refine the knowledge of the mechanisms associated with the superior features of autotetraploid P. tomentosa and provide some help for future paulownia breeding programs.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Autotetraploid P. tomentosa (PT4) was induced by colchicine using the leaves of diploid P. tomentosa (PT2) in our previous study (Fan et al. 2007). Then, autotetraploid and diploid P. tomentosa were conserved by tissue culture in the Institute of Paulownia, Henan Agricultural University, Zhengzhou, Henan Province, China. The conservation conditions were as follows: 25 ± 2 °C, 70% humidity, 130 μmol m−2 s−1 illumination intensity and 16 h/8 h (day/night) photoperiod. Compared with diploid P. tomentosa, autotetraploid P. tomentosa exhibits better photosynthetic characteristics (Zhang et al. 2013) and higher stress tolerance (Deng et al. 2013; Dong et al. 2014a, b, c). In this study, leaves of PT2 and PT4 were used for callus induction and plantlets regeneration according to the method of Zhai et al. (2004) and Dong et al. (2009). All the materials were cultured under the condition mentioned above. After culturing, uniformly terminal buds were collected from different PT2 and PT4 plantlets, then mixed respectively, frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until protein extraction. Two parallel samples were prepared for each genotype.

Morphological and physiological index measurements

30-day-old plantlets for each genotype were used to measure the physiological indexes. The lengths and widths of 10 leaves from three replicates of PT2 and PT4 were measured. The content of chlorophyll was determined with the method described previously (Wang et al. 2016).

Protein extraction and digestion

Leaf tissues from PT2 and PT4 were well ground in liquid nitrogen and treated with lysis buffer (7 M Urea, 2 M Thiourea, 4% CHAPS, 40 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.5) consisting of 1 mM PMSF and 2 mM EDTA (final concentration). DTT was added to the samples at a final concentration of 10 mM after 5 min. The protein was extracted, reduced and alkylated according to the method of Fan et al. (2015b) and quantified using the Bradford assay with BSA as the standard (Bradford 1976). For each sample, 100 μg of total protein extract was digested using Trypsin Gold (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) with a protein:trypsin ratio of 30:1 for 16 h at 37 °C.

iTRAQ analysis

The digested peptides were dried, reconstituted with 0.5 M TEAB and labeled using iTRAQ 8-plex kits (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) according to the manufacture’s manual. PT2 and PT4 peptide samples were labeled with 113- and 115-iTRAQ tags separately. The iTRAQ experiment was performed on two independent biological replicates. Subsequently, the labeled peptides were pooled, lyophilized and redissolved in 4 ml buffer A (25 mM NaH2PO4 in 25% ACN, pH 2.7) for fractionation by strong cation exchange (SCX) chromatography using LC-20AB HPLC Pump system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) with a Ultremex SCX column (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm particles) (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). The peptides were eluted with a gradient of buffer B (25 mM NaH2PO4, 1 M KCl in 25% ACN, pH 2.7) according to the method of Ge et al. (2014). Elution was monitored by measuring the absorbance at 214 nm, and fractions were collected every 1 min. The eluted fractions were pooled into 20 fractions, desalted with a Strata X C18 column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA), vacuum-dried, and then analyzed by LC–MS/MS using LC-20AD nanoHPLC (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) and TripleTOF 5600 systems (AB SCIEX, Concord, ON) as described previously (Ge et al. 2014). Briefly, each fraction was resuspended in buffer A (5% ACN, 0.1% FA) and centrifuged. Then, 5 μl supernatant was loaded on a LC-20AD nanoHPLC by the autosampler onto a 2 cm C18 trap column. Data acquisition was performed with a TripleTOF 5600 system fitted with a Nanospray III source (AB SCIEX, Concord, ON) and a pulled quartz tip as the emitter (New Objectives, Woburn, MA, USA). The process of LC–MS/MS analysis was detailedly described in the Supplemental protocol. The raw mass spectra data were processed using the Proteome Discoverer 1.2 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA). Proteins identification was performed by using the Mascot software version 2.3.02 (Matrix Science, London, UK) against the recently annotated P. tomentosa transcriptome dataset containing 26,059 entries. The search parameters were used as described earlier (Yang et al. 2013). These parameters were set as follows: MS/MS ion search; trypsin enzyme; the fragment mass tolerance of ±0.1 Da; the intact peptide mass tolerance of ±0.05 Da; monoisotopic mass values; one max missed cleavage site; fixed modifications of carbamidomethyl (C), iTRAQ 8-plex (N-term) and iTRAQ 8-plex (K); variable modifications of Gln->pyro-Glu (N-term Q), Oxidation (M) and iTRAQ 8-plex (Y). iTRAQ 8-plex was chosen for quantification during the search simultaneously.

For protein identification, only peptides with significant hits (99% confidence) were counted as identified, and each confident protein identification involved at least one unique peptide (Ge et al. 2014; Peng et al. 2015; Zhong et al. 2017; Chen et al. 2017). For protein quantification, a protein had to contain at least two unique peptides and the quantitative protein ratios were weighted and normalized by the median ratio in Mascot. Proteins with fold changes >1.2 or <0.83 and p values <0.05 in at least one of the repeated analysis and having the same trend (1 < fold changes < 1.2 or 0.83 < fold changes < 1) in the other repeated analysis were defined as differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) (Shen et al. 2015).

Bioinformatics analysis of proteins

All the identified proteins were annotated and categorized based on the Gene Ontology (GO) (Blake et al. 2013) and Clusters of Orthologous Groups of proteins (COG) databases (Tatusov et al. 2003). Additionally, the identified proteins were also mapped to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genome (KEGG) database (Kanehisa and Goto 2000) for metabolic pathway analysis.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) confirmation

To validate the DEPs identified by iTRAQ, 10 proteins were selected randomly based on the proteomic data and the corresponding unigenes sequences were used for the qRT-PCR analysis. The gene-specific primers were designed using Beacon Designer 7.7 software (http://www.premierbiosoft.com/index.html), and their sequences and other details are listed in Table 1. Total RNA was isolated from the leaves of PT2 and PT4 using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using a iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (http://www.bio-rad.com/webroot/web/pdf/lsr/literature/4106228.pdf). qRT-PCR was performed on CFX96™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The reaction system (20 μl) and amplification procedure referred to the method described by Fan et al. (2015a). 18S rRNA was used as an internal control to normalize the gene expression, and the relative gene expression level was quantified using the 2−ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001).

Table 1.

Primer sequences of the unigenes used for qRT-PCR

| Unigene ID | Protein name | Expression trendsa | Primer sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| m.48523 | 8-Hydroxygeraniol dehydrogenase | Up | GATGTTGGTGCTCCTCTC |

| TGCTTCCTTCTTCTTACTAATAG | |||

| m.37390 | Proteasome subunit alpha type-7-like | Down | CGATATGACAGAGCGATTACG |

| GGCGGCATTTCCTTTACG | |||

| m.1174 | 33 kDa ribonucleoprotein | Down | TGAATGGAGTGGAGGTGGAG |

| CTGGTGGCGGAGGAGATG | |||

| m.20714 | Phosphoglycerate kinase | Up | TTCCAAGCCAAGCAGTAG |

| GTCAAGGTCCACATCTCC | |||

| m.22866 | Light dependent NADH:protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase 2 | Up | GGGCATTTCCTCCTTTCAAG |

| TCAATCCTCCAGCAAGTCC | |||

| m.49884 | Catalase | Up | CCTGCTGTTATTGTTCCTG |

| ATGGTGATTGTTGTGATGG | |||

| m.6239 | Ascorbate peroxidase | Down | GGAAGATGCCACAAGGAAC |

| CAGGGTCAGAAAGAAGAGC | |||

| m.13987 | Chloroplast oxygen-evolving protein | Up | AACACTGATTGACAAGAAGG |

| TTGCTGATGGTCTGGAAG | |||

| m.52984 | Unnamed protein product | Up | GGAGGTGGTGGAGGCTATG |

| CAGATTGTGAGGTCGGATTGG | |||

| m.10949 | PHB1 | Down | GGGCAGCGATTATTAGGG |

| AGGCAGATATACCACATTCC | |||

| Internal control | 18s rRNA | ACATAGTAAGGATTGACAGA | |

| TAACGGAATTAACCAGACA |

aExpression trends indicated the expression trends of the selected proteins in PT4 compared with PT2

Results and discussion

Morphological and physiological index measurements

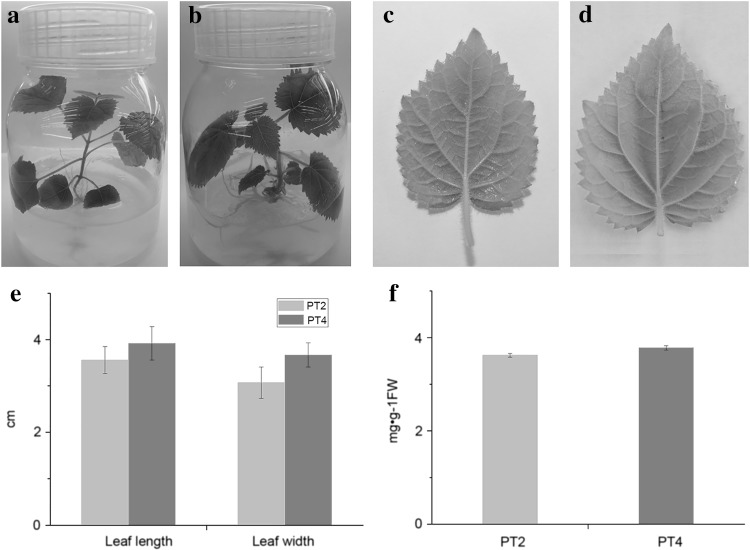

30-day-old plantlets for each genotype were used for morphological and physiological index measurements. The phenotypic differences in plantlets and leaves of PT2 and PT4 are presented in Fig. 1. Compared with PT2 plantlets, PT4 plantlets were more robust with denser bristles (Fig. 1a, b). The leaves of PT4 were larger and thicker than those of PT2 (Fig. 1c, d). As is shown in Fig. 1e, the leaf length and leaf width of PT4 showed increase in contrast with those of PT2. When examining the chlorophyll content, the level of chlorophyll in PT4 was higher than that in PT2 (Fig. 1f).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of morphological and physiological indexes of PT2 and PT4. a Plantlet of PT2 genotype; b plantlet of PT4 genotype; c leaf of PT2; d leaf of PT4; e the leaf length and width of PT2 and PT4; f the chlorophyll content of PT2 and PT4

Protein identification, functional annotation and classification

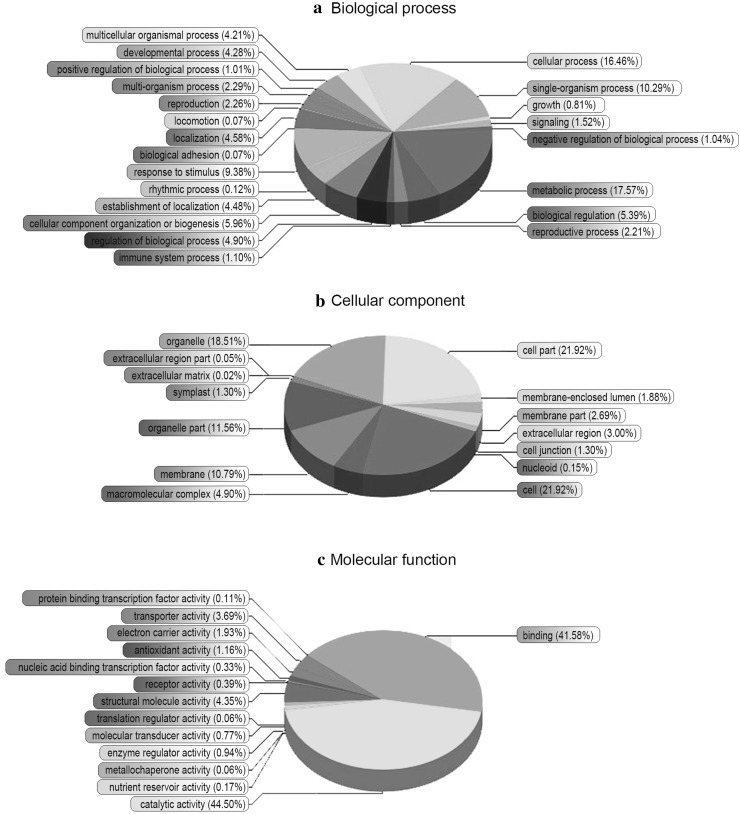

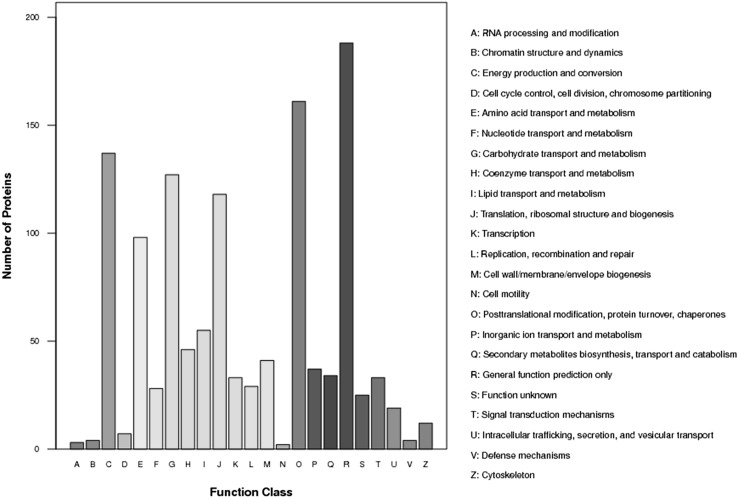

A total of 386,933 spectra were generated from the iTRAQ-based experiments using the proteins extracted from the PT2 and PT4 samples as the materials. The data collected from these samples were analyzed using Mascot 2.3.02 software. Among them, a total of 16,406 spectra matched to known spectra and 13,815 spectra matched to unique spectra (Table S1). Finally, 1427 proteins were identified in P. tomentosa (Table S2). The repeatability of the proteomic analysis is shown in Fig. S2, indicating that the results in our study were reliable. To understand the functions of the identified proteins, GO analysis was conducted under the three main categories: biological process, cellular component and molecular function (Fig. 2). Under the category of biological process, 17.57% of the proteins were related to “metabolic process”, followed by “cellular process” (16.46%); under the category of cellular component, “cell” (21.92%) and “cell part” (21.92%) were the most highly represented; while under the category of molecular function, the highest number of proteins were assigned to “catalytic activity” (44.5%), followed by “binding” (41.58%). In addition, 1241 of the identified proteins were assigned to 23 functional groups in the COG database (Fig. 3). The largest category was “General function prediction only”, followed by “Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones”. Many of the identified proteins were involved in “Energy production and conversion”, “Carbohydrate transport and metabolism” and “Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis”. The KEGG analysis showed that the identified proteins participated in 112 pathways (Table S3). These results indicated that the identified proteins were involved in almost every aspect of P. tomentosa metabolism.

Fig. 2.

GO analysis of proteins identified in P. Tomentosa. 1341 proteins (93.97% of total) were divided into 50 function groups. a Biological process; b cellular component; c molecular function

Fig. 3.

COG analysis of proteins identified in P. Tomentosa. 969 proteins (67.90% of total) were categorized into 23 function groups

Analysis of differentially expressed proteins

Of the 1427 identified proteins, 130 DEPs with fold changes >1.2 and p values <0.05 were screened between PT4 and PT2. Compared with their abundance in PT2, 78 (60%) proteins were increased and 52 (40%) were decreased in PT4 (Table S4). To better understand the differences in the biological processes between PT2 and PT4, we performed a GO enrichment analysis of the DEPs. It was suggested that multiple biological process associated with stress resistance and photosynthesis were significantly enriched at the 5% significant level (Table S5), including defense response to bacterium (GO:0042742, p = 1.29 × 10−4), response to bacterium (GO:0009617, p = 1.70 × 10−4), defense response (GO:0006952, p = 1.63 × 10−2), response to biotic stimulus (GO:0009607, p = 1.88 × 10−2), photosynthesis (GO:0015979, p = 3.78 × 10−4), thylakoid membrane organization (GO:0010027, p = 5.96 × 10−3), and photosystem II assembly (GO:0010207, p = 8.92 × 10−3). Moreover, to further uncover the metabolic pathways in which these proteins may be involved, KEGG enrichment analysis was also conducted. Our results demonstrated that 103 DEPs were mapped to 60 KEGG pathways (Table S6). Among these pathways, DEPs were significantly enriched in ribosome (ko03010, p = 2.97 × 10−3), photosynthesis (ko00195, p = 5.33 × 10−3) and proteasome (ko03050, p = 3.16 × 10−2) at the 5% significant level.

Proteins related to superior photosynthetic characteristics in autotetraploid P. tomentosa

Photosynthesis is the basis of plant growth and development, and improved photosynthetic characteristics have been reported in tetraploid black locust (Meng et al. 2014), hexaploid Miscanthus × giganteus (Ghimire et al. 2016), triploid rice (Wang et al. 2016) and triploid Populus (Liao et al. 2016). The photosynthetic rate is mainly determined by light-dependent reaction, carbon fixation and CO2 entry into the plant through stomata. Zhang et al. (2013) reported that the net photosynthesis rate, stomatal conductance, intercellular CO2 concentration and chlorophyll content all increased in PT4 compared with PT2, which may partly explain the superior photosynthetic characteristics in PT4. Furthermore, in a comparative transcriptome analysis that we reported previously, genes associated with photosynthesis were found to be up-regulated in the PT4 versus PT2 comparison, and it was suggested that the improved photosynthesis in PT4 may mainly attribute to the increased enzyme activity and photosynthetic electron transfer efficiency in the autotetraploid (Fan et al. 2015a). In this study, 14 DEPs with known functions in the non-redundant protein sequences (Nr) database were found to be related to photosynthesis in P. tomentosa (Table 2). Among these DEPs, 7 displayed increased abundances in PT4 compared with PT2 and were annotated as chloroplast rubisco activase (ABK55669.1), phosphoglycerate kinase (AAA79705.1), chloroplast oxygen-evolving protein (ACA58355.1), photosystem I reaction center subunit IV B (PsaE-2) (XP_011080143.1), putative cytochrome b6f Rieske iron-sulfur subunit (ACS44643.1), photosystem I reaction center subunit VI (P20121.1), and protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase 2 (AAF82475.1). The light-dependent reaction involves light induced charge separation, electron transport and synthesis of ATP, and is mainly driven by four intrinsic multi-subunit membrane-protein complexes named photosystem I (PSI), photosystem II (PSII), cytochrome (cyt) b6f complex and ATP synthase (Nelson and Yocum 2006). PSI is located in the stroma lamellae, and is composed of a reaction center consisting of different subunits and a light-harvesting complex (LHC). PsaE, a small hydrophilic subunit of PSI that is very accessible to the surrounding medium, plays an indispensable role in optimizing electron transport to ferredoxin and flavodoxin. Besides, PsaE is likely to be important for the stability of PSI (Scheller et al. 2001). Chloroplast oxygen-evolving protein is a nuclear-encoded extrinsic protein of PSII which is required for O2 evolution activity under physiological conditions and it may constitute a benefit to stabilize the PSII system. Cytochrome b6f Rieske iron-sulfur subunit combining with other subunits of cytochrome (cyt) b6f complex resides in the thylakoid membrane and provides the electronic connection between the PSI and PSII reaction centers, which generates a trans-membrane electrochemical proton gradient for ATP synthesis (Kurisu et al. 2003). These proteins are likely to contribute to the improved photochemical reaction efficiency of PT4. Carbon fixation catalyzed by a series of enzymes can assimilate CO2 into organic matter and may contribute to the accumulation of biomass. Rubisco is a key enzyme involved in the incorporation of atmospheric CO2 into ribulose bisphosphate, and this process generates the necessary building blocks for carbohydrate biosynthesis. Chloroplast rubisco activase (RCA) is a chaperone-like protein of the AAA + ATPase family, which utilizes ATP hydrolysis to remove tight-binding inhibitors and activate the catalytic activity of Rubisco (Henderson et al. 2013). It was reported that photosynthesis in rice can be improved by inducing RCA gene expression (Chen et al. 2014). Hence, the increased RCA may regulate the initial Rubisco activity, which will be beneficial to carbon fixation. Phosphoglycerate kinase catalyzes the phosphorylation of 3-phosphoglycerate to 1,3-diphosphoglycerate within the Calvin cycle using ATP (Tsukamoto et al. 2013), and it is also associated with glycolysis/gluconeogenesis. These findings indicate that changes in the protein expression profiles in PT4 compared with PT2 may help to explain the photosynthetic superiority observed in autopolyploids.

Table 2.

DEPs related to photosynthesis between PT2 and PT4

| Unigene | Accession no.a | Protein name | FCb |

|---|---|---|---|

| m.40546 | ABK55669.1 | Chloroplast rubisco activase | 1.839 |

| m.20714 | AAA79705.1 | Phosphoglycerate kinase | 1.311 |

| m.22866 | AAF82475.1 | Protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase 2 | 1.299 |

| m.13987 | ACA58355.1 | Chloroplast oxygen-evolving protein | 1.280 |

| m.13986 | ACA58355.1 | Chloroplast oxygen-evolving protein | 1.266 |

| m.22039 | XP_011080143.1 | Photosystem I reaction center subunit IV B | 1.246 |

| m.10882 | ACS44643.1 | Putative cytochrome b6f Rieske iron-sulfur subunit | 1.229 |

| m.17700 | P20121.1 | Photosystem I reaction center subunit VI | 1.219 |

| m.48581 | XP_002531690.1 | Chlorophyll A/B binding protein | 0.778 |

| m.21971 | BAH84857.1 | Putative porphobilinogen deaminase | 0.764 |

| m.27093 | CAM59940.1 | Putative Mg-protoporphyrin IX monomethyl ester cyclase | 0.750 |

| m.13940 | AAF19787.1 | Photosystem I subunit III | 0.638 |

| m.43677 | P83504.1 | Oxygen-evolving enhancer protein 1 | 0.561 |

| m.52524 | ABW89104.1 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 0.553 |

| m.19368 | AEC11062.1 | Photosystem I reaction center subunit XI | 0.505 |

aNCBI accession number

bFC: Fold changes of proteins in PT4 compared with PT2

Proteins associated with the potentially enhanced stress adaptability of autotetraploid P. tomentosa

It is generally accepted that polyploidization always confers higher stress tolerance to polyploids compared with their corresponding parents (Podda et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2013), and enhanced adaptability to various stresses has been observed in autotetraploid paulownia (Deng et al. 2013; Dong et al. 2014a, b, c; Xu et al. 2014; Fan et al. 2016). Our previous anatomy research showed that the thickness of leaves, palisade tissue, cell tense ratio and thickness ratio of palisade tissue to sponge tissue of tetraploid paulownia were larger than those of the diploids (Zhang et al. 2012), which may provide a better protection mechanism for autotetraploid paulownia than for its diploid. In a previous study, we found that the constitutive expression levels of stress-responsive genes and miRNAs that mediated defense response were significantly up-regulated and down-regulated, respectively, in autotetraploid paulownia (Fan et al. 2014, 2015a). In the present study, 27 constitutively defense-responsive proteins with known functions were found to be differentially expressed in PT4 compared to its diploid progenitor (Table 3). Among these proteins, 2-hydroxyisoflavanone dehydratase-like (XP_011088284.1), calmodulin (XP_010645766.1), 8-hydroxygeraniol dehydrogenase (Q6V4H0.1), catalase (AFC01205.1), formate dehydrogenase (XP_002278444.1) and pyruvate dehydrogenase E1-beta subunit (ADK70385.1), which play vital roles in the adaptability of PT4 to stresses tended to be up-regulated in the comparison of PT4 versus PT2. Isoflavonoids are a large group of plant secondary metabolites, including pisatin, maackiain, genistin, daidzin and glyceollin, which play important roles as antimicrobial phytoalexins in plant defense systems against microorganisms and herbivores (Wang 2011). In soybean roots infected with Fusarium solani, glyceollin was rapidly produced to resist the fungus (Lozovaya et al. 2004). The abundance of 2-hydroxyisoflavanone dehydratase, which is the key enzyme in isoflavonoid biosynthesis, was increased 2.44-fold in PT4 compared with PT2. The Ca2+ signal is essential for the activation of plant defense responses and calmodulin acting as a Ca2+ signal transducer is reported to participate in Ca2+-mediated induction of plant disease resistance responses (Heo et al. 1999; Ali et al. 2003; Takabatake et al. 2007). Catalase is an important antioxidant enzyme that plays a major role in the defense against oxidative stress by converting hydrogen peroxide to oxygen and water at an extremely rapid rate, thereby protecting the plants from oxidative damage (Michiels et al. 1994; Willekens et al. 1997). Transgenic tobacco plants expressing the maize Cat2 gene had altered catalase levels that resulted in increased catalase activity and enhanced resistance to oxidative stress in the plants (Polidoros et al. 2001). The pyruvate dehydrogenase complex catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA, linking glycolysis to the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. In our iTRAQ data, a subunit of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex was found to be up-regulated in PT4, suggesting that the TCA cycle was enhanced, which would ensure sufficient energy for PT4 to resist stress. The alterations in abundances of these constitutively expressed proteins in PT4 may contribute to its potential stress adaptability.

Table 3.

DEPs associated with stress response between PT2 and PT4

| Unigene | Accession no.a | Protein name | FCb |

|---|---|---|---|

| m.6249 | XP_002266488.1 | Proteasome subunit beta type-6 | 6.8315 |

| m.4321 | ABE66404.1 | DREPP4 protein | 2.447 |

| m.13643 | XP_004230814.1 | Probable carboxylesterase 7-like | 2.4395 |

| m.10909 | XP_002263538.1 | Calmodulin isoform 2 | 2.2845 |

| m.54721 | ACD88869.1 | Translation initiation factor eIF(iso)4G | 2.1205 |

| m.49884 | AFC01205.1 | Catalase | 1.8045 |

| m.50291 | AFP49334.1 | Pathogenesis-related protein 10.4 | 1.734 |

| m.13367 | ADM67773.1 | 40S ribosomal subunit associated protein | 1.5375 |

| m.64528 | ADK70385.1 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1-beta subunit | 1.477 |

| m.48523 | Q6V4H0.1 | 8-Hydroxygeraniol dehydrogenase | 1.471 |

| m.11708 | NP_001234515.1 | Temperature-induced lipocalin | 1.316 |

| m.27962 | XP_002278444.1 | Formate dehydrogenase | 1.297 |

| m.42262 | XP_002514263.1 | Elongation factor ts | 1.292 |

| m.64561 | XP_004235848.1 | Glycine–tRNA ligase 1 | 1.2565 |

| m.26523 | ABF46822.1 | Putative nitrite reductase | 1.24 |

| m.63348 | AFD50424.1 | Cobalamine-independent methionine synthase | 0.802 |

| m.8635 | ACB72462.1 | Elongation factor 1 gamma-like protein | 0.794 |

| m.6239 | AAL38027.1 | Ascorbate peroxidase | 0.771 |

| m.10038 | Q9XG77.1 | Proteasome subunit alpha type-6 | 0.757 |

| m.10949 | AAZ30376.1 | PHB1 | 0.7275 |

| m.5417 | Q05046.1 | Chaperonin CPN60-2 | 0.712 |

| m.37390 | XP_004134855.1 | Proteasome subunit alpha type-7-like | 0.6895 |

| m.64208 | XP_003635036.1 | Heat shock cognate protein 80-like | 0.6875 |

| m.8250 | CAH58634.1 | Thioredoxin-dependent peroxidase | 0.66 |

| m.1613 | ABR92334.1 | Putative dienelactone hydrolase family protein | 0.6485 |

| m.60046 | CAA05280.1 | Loxc homologue | 0.624 |

| m.29947 | XP_002312539.1 | MLP-like protein 28-like | 0.504 |

aNCBI accession number

bFC: Fold changes of proteins in PT4 compared with PT2

Verification of differentially expressed proteins by qRT-PCR

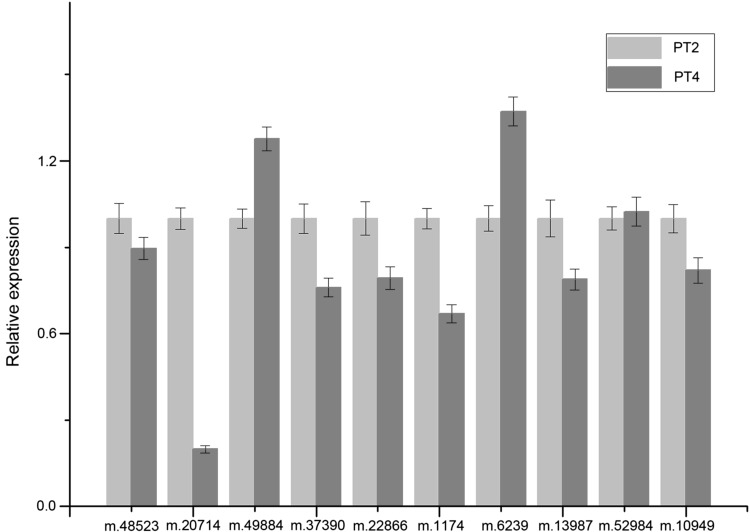

We further performed qRT-PCR to assess the expression of unigenes coding 10 DEPs selected randomly. The results are showed in Fig. 4. Among the unigenes corresponding to the selected proteins, five showed similar change trends in their expression levels with the DEPs based on the iTRAQ data. Three of these unigenes encoding proteasome subunit alpha type-7-like, 33 kDa ribonucleoprotein and PHB1 showed relatively decreased abundances in PT4, and two encoding catalase and NADP-dependent malic enzyme displayed relatively increased abundances in PT4. This result indicated that these proteins were regulated by transcription. However, the other five unigenes encoding 8-hydroxygeraniol dehydrogenase, phosphoglycerate kinase, light dependent NADH: protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase 2, ascorbate peroxidase and chloroplast oxygen-evolving protein, displayed discrepancy with the results of iTRAQ. This may be due to the post-transcriptional, translational, and post-translational regulation processes.

Fig. 4.

qRT-PCR analysis of 10 differentially expressed proteins selected randomly between diploid P. tomentosa and its autotetraploid. m.48523 8-hydroxygeraniol dehydrogenase, m.20714 phosphoglycerate kinase, m.49884 catalase, m.37390 proteasome subunit alpha type-7-like, m.22866 protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase 2, m.1174 33 kDa ribonucleoprotein, m.6239 ascorbate peroxidase, m.13987 chloroplast oxygen-evolving protein, m.52984 NADP-dependent malic enzyme, m.10949 PHB1. Bars represent the mean (±SD)

Correlation analysis of proteome with transcriptome data

To further determine whether transcript-level changes between PT4 and PT2 were correlated with changes in protein accumulation, the proteome data produced in this research and transcriptome data generated previously were compared (Fan et al. 2015a).

A subset of 2830 unigenes was differentially expressed between PT4 and PT2 with the absolute value of log2 ratio > 2 and FDR < 0.001. To compare the proteome with the transcriptome, we matched the DEPs against all differentially expressed unigenes. As a result, only 15 (11.5%) DEPs detected in the present study had corresponding differentially expressed unigenes between PT4 and PT2 datasets, indicating there was a poor correlation between mRNA expression and protein abundance (Table S7). Similar up-regulation or down-regulation of transcript and protein levels suggests transcriptional regulation of gene expression. In the PT4 and PT2 comparisons, only four and one proteins displayed the same trend of up-regulation and down-regulation in PT4 at transcript level, respectively. These five proteins were chloroplast rubisco activase (ABK55669.1), Chain A (2DCQ|A), protein S (AAU95203.1), catalase (AFC01205.1) and putative porphobilinogen deaminase (BAH84857.1). In addition, 113 proteins displayed significant expression differences between PT4 and PT2, while the corresponding mRNAs displayed no expression changes (Table S8). Futher, 58 proteins showed no significant expression differences between PT4 and PT2, although the corresponding mRNA showed significant expression differences (Table S9). These data indicated that gene expression was also regulated by post-transcription, translation, and post-translation modifications.

Limited correlation between mRNA expression and protein abundance levels has been also reported in Citrus sinensis (Fan et al. 2011), Arabidopsis polyploids (Ng et al. 2012), T. mirus (Koh et al. 2012) and Brassica hexaploid (Shen et al. 2015). There are several possible explanations for the discordance between transcriptome and proteome data. First, gene expression is a complicated process. In addition to transcriptional regulations, gene expression is also governed by post-transcriptional regulations, translational processes, and post-translational modifications. For instance, transposable elements have been found to participate in regulating the transcription of neighboring genes (Kashkush et al. 2003; Madlung et al. 2005); small RNAs (i.e. microRNAs and small interfering RNAs) may silence mRNAs and repress protein translation (Marmagne et al. 2010); and many mRNAs can give rise to more than one protein due to alternative splicing (Black 2003); moreover, the stability of mRNAs and proteins can also affect protein content. Second, several experimental factors and different detection methods could contribute to the poor correlation between mRNAs and proteins. High-throughput RNA sequencing can provide a precise analysis of RNA transcripts to detect transcriptome changes (Ansorge 2009), while iTRAQ may underestimate protein abundance ratios because of its imperfect accuracy (Ow et al. 2009; Karp et al. 2010). Furthermore, the possibility that the discordance was caused by the different sets of plant materials used in transcriptome and proteome comparative researches cannot be excluded.

Conclusions

iTRAQ-based quantitative proteomic approach was used for the comparative analysis of protein abundances in PT4 and PT2. A total of 1427 proteins were identified, of which 130 proteins were differentially expressed between PT2 and PT4. Photosynthesis-related proteins and stress-responsive proteins were significantly enriched between PT2 and PT4 based on GO and KEGG enrichment analysis. Among them, chloroplast oxygen-evolving protein, chloroplast rubisco activase, photosystem I reaction center subunit IV B, photosystem I reaction center subunit VI, cytochrome b6f Rieske iron-sulfur subunit, phosphoglycerate kinase, 2-hydroxyisoflavanone dehydratase-like, calmodulin, 8-hydroxygeraniol dehydrogenase, catalase and pyruvate dehydrogenase E1-beta subunit increased in PT4 which may be responsible for the superior photosynthetic characteristics and stress adaptability of PT4. Furthermore, the correlation analysis between proteome and transcriptome showed that the changes at protein level are not correlated well with the changes at transcripts level in PT4. This suggests that post-transcriptional, translational and post-translational regulations play important roles in protein expression. Complementary to previous transcriptome and small RNA profile, our proteomic analysis will provide new insights into better understanding the superior traits in PT4 and the candidate target genes identified in the present study could be used for genetic improvement of Paulownia.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 11. Repeatability of the proteomic analysis between two biological replicates X-axis represents the difference of the quantitative ratios between biological replicate 1 and biological replicate 2 of the two samples. The right Y-axis represents the cumulative percentage between the proteins of a certain range and the quantitative proteins, while the left Y-axis represents the number of total protein in a certain range. (TIFF 9744 kb)

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 30271082, 30571496, U1204309), Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (No. 162300410158) and Science and Technology Innovation Talents Project of Henan Province (No. 174200510001).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12298-017-0447-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- Adams KL, Wendel JF. Polyploidy and genome evolution in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2005;8:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam I, Sharmin SA, Kim KH, Yang JK, Choi MS, Lee BH. Proteome analysis of soybean roots subjected to short-term drought stress. Plant Soil. 2010;333:491–505. doi: 10.1007/s11104-010-0365-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Albertin W, Brabant P, Catrice O, Eber F, Jenczewski E, Chevre AM, Thiellement H. Autopolyploidy in cabbage (Brassica oleracea L.) does not alter significantly the proteomes of green tissues. Proteomics. 2005;5:2131–2139. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali GS, Reddy VS, Lindgren PB, Jakobek JL, Reddy ASN. Differential expression of genes encoding calmodulin-binding proteins in response to bacterial pathogens and inducers of defense responses. Plant Mol Biol. 2003;51:803–815. doi: 10.1023/A:1023001403794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An F, Fan J, Li J, Li QX, Li K, Zhu W, Wen F, Carvalho LJ, Chen S. Comparison of leaf proteomes of cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) cultivar NZ199 diploid and autotetraploid genotypes. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e85991. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansorge WJ. Next-generation DNA sequencing techniques. New Biotechnol. 2009;25:195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ates S, Ni Y, Akgul M, Tozluoglu A. Characterization and evaluation of Paulownia elongota as a raw material for paper production. Afr J Biotechnol. 2008;7:4153–4158. [Google Scholar]

- Black DL. Mechanisms of alternative pre-messenger RNA splicing. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:291–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake JA, Dolan M, Drabkin H, Hill DP, Li N, Sitnikov D, Bridges S, Burgess S, Buza T, Mccarthy F. Gene ontology annotations and resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:530–535. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZJ. Genetic and epigenetic mechanisms for gene expression and phenotypic variation in plant polyploids. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2007;58:377–406. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.58.032806.103835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Jin JH, Jiang QS, Yu CL, Chen J, Xu LG. Sodium bisulfite enhances photosynthesis in rice by inducing Rubisco activase gene expression. Photosynthetica. 2014;52:475–478. doi: 10.1007/s11099-014-0044-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Fu X, Mei X, Zhou Y, Cheng S, Zeng L, Dong F, Yang Z. Proteolysis of chloroplast proteins is responsible for accumulation of free amino acids in dark-treated tea (Camellia sinensis) leaves. J Proteomics. 2017;157:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2017.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comai L. The advantages and disadvantages of being polyploid. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:836–846. doi: 10.1038/nrg1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng M, Zhang X, Fan G, Zhao Z, Dong Y, Wei Z. Comparative studies on physiological responses to salt stress in tetraploid Paulownia plants. J Cent South Univ For Technol. 2013;33:42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z, Fan G, Wei Z, Yang Z. Effect of chemical mutagens on in vitro plantlet regeneration of Paulownia tomentosa autotetraploid. J Henan Agric Univ. 2009;43:44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Fan G, Deng M, Xu E, Zhao Z. Genome-wide expression profiling of the transcriptomes of four Paulownia tomentosa accessions in response to drought. Genomics. 2014;104:295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Fan G, Zhao Z, Deng M. Compatible solute, transporter protein, transcription factor, and hormone-related gene expression provides an indicator of drought stress in Paulownia fortunei. Funct Integr Genomics. 2014;14:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10142-014-0373-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Fan G, Zhao Z, Deng M. Transcriptome expression profiling in response to drought stress in Paulownia australis. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:4583–4607. doi: 10.3390/ijms15034583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan G, Yang Z, Cao Y. Induction of autotetraploid of Paulownia tomentosa (Thunb.) Steud. Plant Physiol Commun. 2007;43:109–111. [Google Scholar]

- Fan J, Chen C, Yu Q, Brlansky RH, Li ZG, Gmitter FG., Jr Comparative iTRAQ proteome and transcriptome analyses of sweet orange infected by “Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus”. Physiol Plantarum. 2011;143:235–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2011.01502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan G, Zhai X, Niu S, Ren Y. Dynamic expression of novel and conserved microRNAs and their targets in diploid and tetraploid of Paulownia tomentosa. Biochimie. 2014;102:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan G, Wang L, Deng M, Niu S, Zhao Z, Xu E, Cao X, Zhang X. Transcriptome analysis of the variations between autotetraploid Paulownia tomentosa and its diploid using high-throughput sequencing. Mol Genet Genomics. 2015;290:1627–1638. doi: 10.1007/s00438-015-1023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan H, Xu Y, Du C, Wu X. Phloem sap proteome studied by iTRAQ provides integrated insight into salinity response mechanisms in cucumber plants. J Proteomics. 2015;125:54–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan G, Li X, Deng M, Zhao Z, Yang L. Comparative analysis and identification of miRNAs and their target genes responsive to salt stress in diploid and tetraploid Paulownia fortunei seedlings. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0149617. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Zhang C, Wang Q, Yang Z, Wang Y, Zhang X, Wu Z, Hou Y, Wu J, Li F. iTRAQ protein profile differential analysis between somatic globular and cotyledonary embryos reveals stress, hormone, and respiration involved in increasing plantlet regeneration of Gossypium hirsutum L. J Proteome Res. 2014;14:268–278. doi: 10.1021/pr500688g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghimire BK, Seong ES, Nguyen TX, Ji HY, Chang YY, Kim SH, Chung IM. Assessment of morphological and phytochemical attributes in triploid and hexaploid plants of the bioenergy crop Miscanthus × giganteus. Ind Crop Prod. 2016;89:231–243. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.04.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore JM, Washburn MP. Advances in shotgun proteomics and the analysis of membrane proteomes. J Proteomics. 2010;73:2078–2091. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gygi SP, Rochon Y, Franza BR, Aebersold R. Correlation between protein and mRNA abundance in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1720–1730. doi: 10.1128/MCB.19.3.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson JN, Hazra S, Dunkle AM, Salvucci ME, Wachter RM. Biophysical characterization of higher plant Rubisco activase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1834:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo WD, Lee SH, Kim MC, Kim JC, Chung WS, Chun HJ, Lee KJ, Park CY, Park HC, Choi JY, Cho MJ. Involvement of specific calmodulin isoforms in salicylic acid-independent activation of plant disease resistance responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:766–771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam N, Tsujimoto H, Hirano H. Proteome analysis of diploid, tetraploid and hexaploid wheat: towards understanding genome interaction in protein expression. Proteomics. 2003;3:549–557. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200390068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karp NA, Huber W, Sadowski PG, Charles PD, Hester SV, Lilley KS. Addressing accuracy and precision issues in iTRAQ quantitation. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:1885–1897. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900628-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashkush K, Feldman M, Levy AA. Transcriptional activation of retrotransposons alters the expression of adjacent genes in wheat. Nat Genet. 2003;33:102–106. doi: 10.1038/ng1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaygin B, Kaplan D, Aydemir D. Paulownia tree as an alternative raw material for pencil manufacturing. BioResources. 2015;10:3426–3433. doi: 10.15376/biores.10.2.3426-3433. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koh J, Chen S, Zhu N, Yu F, Soltis PS, Soltis DE. Comparative proteomics of the recently and recurrently formed natural allopolyploid Tragopogon mirus (Asteraceae) and its parents. New Phytol. 2012;196:292–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurisu G, Zhang H, Smith JL, Cramer WA. Structure of the cytochrome b6f complex of oxygenic photosynthesis: tuning the cavity. Science. 2003;302:1009–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.1090165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitch IJ, Bennett MD. Polyploidy in angiosperms. Trends Plant Sci. 1997;2:470–476. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(97)01154-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leitch AR, Leitch IJ. Genomic plasticity and the diversity of polyploid plants. Science. 2008;320:481–483. doi: 10.1126/science.1153585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao T, Cheng S, Zhu X, Min Y, Kang X. Effects of triploid status on growth, photosynthesis, and leaf area in Populus. Trees. 2016;30:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00468-016-1352-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López F, Pérez A, Zamudio MAM, De Alva HE, García JC. Paulownia as raw material for solid biofuel and cellulose pulp. Biomass Bioenergy. 2012;45:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2012.05.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lozovaya VV, Lygin AV, Zernova OV, Li S, Hartman GL, Widholm JM. Isoflavonoid accumulation in soybean hairy roots upon treatment with Fusarium solani. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2004;42:671–679. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madlung A, Tyagi AP, Watson B, Jiang H, Kagochi T, Doerge RW, Martienssen R, Comai L. Genomic changes in synthetic Arabidopsis polyploids. Plant J. 2005;41:221–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmagne A, Brabant P, Thiellement H, Alix K. Analysis of gene expression in resynthesized Brassica napus allotetraploids: transcriptional changes do not explain differential protein regulation. New Phytol. 2010;186:216–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng F, Peng M, Pang H, Huang F. Comparison of photosynthesis and leaf ultrastructure on two black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia L.) Biochem Syst Ecol. 2014;55:170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.bse.2014.03.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Michiels C, Raes M, Toussaint O, Remacle J. Importance of Se-glutathione peroxidase, catalase, and Cu/Zn-SOD for cell survival against oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 1994;17:235–248. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson N, Yocum CF. Structure and function of photosystems I and II. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:521–565. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng DW, Zhang C, Miller M, Shen Z, Briggs SP, Chen ZJ. Proteomic divergence in Arabidopsis autopolyploids and allopolyploids and their progenitors. Heredity. 2012;108:419–430. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2011.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn TC, Pires JC, Birchler JA, Auger DL, Chen ZJ, Lee HS, Comai L, Madlung A, Doerge RW, Colot V, Martienssen RA. Understanding mechanisms of novel gene expression in polyploids. Trends Genet. 2003;19:141–147. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ow SY, Salim M, Noirel J, Evans C, Rehman I, Wright PC. iTRAQ underestimation in simple and complex mixtures: “the good, the bad and the ugly”. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:5347–5355. doi: 10.1021/pr900634c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X, Qin Z, Zhang G, Guo Y, Huang J. Integration of the proteome and transcriptome reveals multiple levels of gene regulation in the rice dl2 mutant. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:351. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podda A, Checcucci G, Mouhaya W, Centeno D, Rofidal V, Del Carratore R, Luro F, Morillon R, Ollitrault P, Maserti BE. Salt-stress induced changes in the leaf proteome of diploid and tetraploid mandarins with contrasting Na+ and Cl− accumulation behaviour. J Plant Physiol. 2013;170:1101–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polidoros AN, Mylona PV, Scandalios JG. Transgenic tobacco plants expressing the maize Cat2 gene have altered catalase levels that affect plant-pathogen interactions and resistance to oxidative stress. Transgenic Res. 2001;10:555–569. doi: 10.1023/A:1013027920444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabilloud T. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis in proteomics: old, old fashioned, but it still climbs up the mountains. Proteomics. 2002;2:3–10. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200201)2:1<3::AID-PROT3>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheller HV, Jensen PE, Haldrup A, Lunde C, Knoetzel J. Role of subunits in eukaryotic Photosystem I. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1507:41–60. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(01)00196-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Zhang Y, Zou J, Meng J, Wang J. Comparative proteomic study on Brassica hexaploid and its parents provides new insights into the effects of polyploidization. J Proteomics. 2015;112:274–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takabatake R, Karita E, Seo S, Mitsuhara I, Kuchitsu K, Ohashi Y. Pathogen-induced calmodulin isoforms in basal resistance against bacterial and fungal pathogens in tobacco. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007;48:414–423. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusov RL, Fedorova ND, Jackson JD, Jacobs AR, Kiryutin B, Koonin EV, Krylov DM, Mazumder R, Mekhedov SL, Nikolskaya AN, Rao BS, Smirnov S, Sverdlov AV, Vasudevan S, Wolf YI, Yin JJ, Natale DA. The COG database: an updated version includes eukaryotes. BMC Bioinform. 2003;4:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto Y, Fukushima Y, Hara S, Hisabori T. Redox control of the activity of phosphoglycerate kinase in Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013;54:484–491. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pct002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. Structure, function, and engineering of enzymes in isoflavonoid biosynthesis. Funct Integr Genomics. 2011;11:13–22. doi: 10.1007/s10142-010-0197-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Wang M, Liu L, Meng F. Physiological and proteomic responses of diploid and tetraploid black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia L.) subjected to salt stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:20299–20325. doi: 10.3390/ijms141020299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Lv Y, Fang F, Hong S, Guo Q, Hu S, Zou F, Shi L, Lei Z, Ma K, Zhou D, Zhang D, Sun Y, Ma L, Shen B, Zhu C. Identification of proteins associated with pyrethroid resistance by iTRAQ-based quantitative proteomic analysis in Culex pipiens pallens. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:95. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0709-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XC, Li Q, Jin X, Xiao GH, Liu GJ, Liu NJ, Qin YM. Quantitative proteomics and transcriptomics reveal key metabolic processes associated with cotton fiber initiation. J Proteomics. 2015;114:16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2014.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Chen W, Yang C, Yao J, Xiao W, Xin Y, Qiu J, Hu W, Yao H, Ying W, Fu Y, Tong J, Chen Z, Ruan S, Ma H. Comparative proteomic analysis reveals alterations in development and photosynthesis-related proteins in diploid and triploid rice. BMC Plant Biol. 2016;16:199. doi: 10.1186/s12870-016-0891-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese S, Reidegeld KA, Meyer HE, Warscheid B. Protein labeling by iTRAQ: a new tool for quantitative mass spectrometry in proteome research. Proteomics. 2007;7:340–350. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willekens H, Chamnongpol S, Davey M, Schraudner M, Langebartels C, Van Montagu M, Inzé D, Van Camp W. Catalase is a sink for H2O2 and is indispensable for stress defence in C3 plants. EMBO J. 1997;16:4806–4816. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.16.4806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu E, Fan G, Niu S, Zhao Z, Deng M, Dong Y. Transcriptome-wide profiling and expression analysis of diploid and autotetraploid Paulownia tomentosa × Paulownia fortunei under drought stress. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e113313. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang LT, Qi YP, Lu YB, Guo P, Sang W, Feng H, Zhang HX, Chen LS. iTRAQ protein profile analysis of Citrus sinensis roots in response to long-term boron-deficiency. J Proteomics. 2013;93:179–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo MJ, Liu X, Pires JC, Soltis PS, Soltis DE. Nonadditive gene expression in polyploids. Genetics. 2014;48:485–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-120213-092159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai X, Wang Z, Fan G. Direct plantlet regeneration via organogenesis of Paulownia plants. Acta Agric Nucleatae Sin. 2004;18:357–360. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Zhai X, Fan G, Deng M, Zhao Z. Observation on microstructure of leaves and stress tolerance analysis of different tetraploid Paulownia. J Henan Agric Univ. 2012;46:646–650. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Zhai X, Zhao Z, Deng M, Fan G. Study on the photosynthetic characteristics of different species of tetraploid Paulownia plants. J Henan Agric Univ. 2013;47:400–404. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong X, Wang ZQ, Xiao R, Wang Y, Xie Y, Zhou X. iTRAQ analysis of the tobacco leaf proteome reveals that RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) has important roles in defense against geminivirus–betasatellite infection. J Proteomics. 2017;152:88–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z, Chao C, Lu X, Xiong Y. Paulownia in China: cultivation and utilization. Canada: Asian Network of Biological Sciences, Singapore and International Developmental Research Center; 1986. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 11. Repeatability of the proteomic analysis between two biological replicates X-axis represents the difference of the quantitative ratios between biological replicate 1 and biological replicate 2 of the two samples. The right Y-axis represents the cumulative percentage between the proteins of a certain range and the quantitative proteins, while the left Y-axis represents the number of total protein in a certain range. (TIFF 9744 kb)