Abstract

Definitive clinical trials of new chemotherapies for tuberculosis (TB) treatment require following subjects until at least six months after treatment discontinuation to assess for durable cure, making these trials expensive and lengthy. Surrogate endpoints relating to treatment failure and relapse are currently limited to sputum microbiology, which has limited sensitivity and specificity. In this study we prospectively assessed radiographic changes using 2-deoxy-2-[18F]-fluoro-D-glucose (FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) at two months and six months (CT only) in a cohort of subjects with multidrug-resistant (MDR) TB who were treated with second-line TB therapy for two years and then followed for an additional six months. CT scans were read semi-quantitatively by radiologists and computationally evaluated using custom software to provide volumetric assessment of TB-associated abnormalities. CT scans at six months assessed by readers were predictive of outcomes but not two months and changes in computed abnormal volumes were predictive at both time points. Quantitative changes in FDG uptake two months after starting treatment were associated with long-term outcomes. In this cohort, some radiologic markers were more sensitive than conventional sputum microbiology in distinguishing successful from unsuccessful treatment. These results support the potential of imaging biomarkers as possible surrogate endpoints in clinical trials of new TB drug regimens. Larger cohorts confirming these results are needed.

Introduction

A major focus of tuberculosis (TB) research is the identification of a sensitive and specific biomarker that can not only determine disease stage (latent, active, cured) but also quantitate the risk of disease progression from latent to active and identify active disease that is either cured or heading for relapse. A number of candidate biomarkers are currently under study. The most widely proposed biomarker to predict relapse-free cure is two-month sputum culture conversion status (1). However, this biomarker is far from ideal for predicting relapse, with one meta-analysis reporting a pooled sensitivity of 40% (95% CI 25–56) and specificity of 85% (95% CI 77–91) for predicting relapse (2). More severe disease and cavities on baseline chest X-ray have also been associated with an increased risk of relapse (3). Yet, prospective studies using sputum conversion at 2 months and absence of cavities to shorten treatment have not proven successful (4, 5). Two-month sputum culture conversion has also been the basis of recent drug approvals [cite bedaquiline], in spite of literature demonstrating its poor performance as a surrogate endpoint for patient outcome (6). Better biomarkers for both patient management and trial-level surrogacy are clearly needed.

[18F]-2-fluoro-deoxy-glucose (FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) scans are well established in cancer trials to stage disease and predict outcomes (7–13). A number of case reports and small studies have also used PET/CT scans for TB diagnosis or to assess treatment response. Diagnostic studies have focused on determining extent of TB disease (14, 15), differentiating TB from cancer (15–18), or differentiating active from latent TB (15, 19, 20). Studies that assessed treatment response performed a baseline PET/CT and compared that to a follow-up PET/CT either during treatment (19, 21, 22) and/or after treatment completion (16, 19, 23, 24) to monitor or confirm treatment response at these different time points. To our knowledge, no published study has quantitatively correlated final treatment outcome with early PET/CT treatment response or followed subjects after treatment completion to confirm relapse-free cure. Similarly, although high resolution CT (HRCT) has been used to diagnose TB (25–29) or follow for treatment response (30, 31), no study has quantitatively correlated early HRCT changes with final treatment outcome.

In this study, we hypothesized that quantitative changes on PET/CT or HRCT scans from baseline to two months of treatment in pulmonary multidrug-resistant (MDR) TB subjects would serve as an imaging biomarker that predicts final treatment success or failure six months after the end of therapy better than two-month sputum culture conversion rates. We tested this hypothesis as a secondary endpoint in the context of a previously reported, prospective, randomized clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov #NCT00425113).

Results

Thirty-five subjects with pulmonary MDR-TB were enrolled into a two-arm, prospective, randomized clinical trial comparing metronidazole and placebo in combination with an optimized background regimen, with overall results already reported (32). Four subjects did not complete all pre-specified HRCT and PET/CT scans and were excluded. The baseline characteristics of these subjects have been previously published and include median age 37 years, 81% male, 48% having far advanced disease, 52% having cavitary disease by chest x-ray, and 68% having bilateral disease. In the analyses presented here, four additional subjects were excluded: three due to incomplete follow-up data and another due to corruption of the PET imaging file, leaving 28 subjects for analyses. All subjects were treated for approximately 18 months after sputum culture conversion per WHO guidelines, then followed for an additional six months after the end-of-therapy (EOT) for final treatment outcomes. At six months after EOT, four subjects were identified as treatment failures. Of these, one had an excellent radiological response at 2 months but subsequently failed treatment due to poor adherence. Another culture converted by 2 months but subsequently developed positive cultures again while still on treatment. The other two never culture converted. All subjects were grouped together for this analysis, rather than by study drug arm.

CT Reader Study

Baseline, two-month, and six-month HRCT scans were evaluated by three independent radiologists for analysis of ten different active TB-associated radiographic features in each sextant of the lung (33). Individual features were scored using a semi-quantitative 0–4 scale representing quartiles of percent involvement of the indicated sextant (27, 34), allowing a maximum score of 40. Between-reader variability in feature scores was large so we engaged a fourth radiologist to adjudicate the feature values. The sum of all features from the adjudicated scores was used as the estimate of total disease burden for each study visit. Among the ten CT features evaluated by the radiologists, changes (from baseline to six months) in three of them (i.e., bronchial thickening, consolidations, and cavities) were significantly associated with treatment outcome (P<0.05 for the change from baseline to month 6; Supplemental Figure 1). Figure 1a shows a waterfall plot of patient-level total disease burden as defined by the radiologists at baseline and log2-fold changes at two and six months, sorted by the changes at 6 months. Failure was not more likely in patients with more severe baseline disease, while log-fold change from baseline was somewhat associated with outcome. Receiver-operator characteristic (ROC) curve analysis of change in disease burden scores as a predictor of final treatment outcome gave areas under the ROC curve (AUCs) of 0.78 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.52–1.0) at 2 months (Figure 2a) and 0.82 (95% CI: 0.58–1.0) at 6 months (Figure 2b). The subject with a good initial radiological response who subsequently failed was documented to have been poorly adherent to therapy after the first six months. Excluding this subject, the AUC increased to 0.92 (95% CI 0.79–1.0) at 2 months and 0.93 (95% CI 0.81–1.0) at 6 months.

Figure 1.

a: Waterfall plot of change in CT reader scores and correlation with treatment outcomes.

b: Waterfall plot of change in automated CT abnormal volumes and correlation with treatment outcomes.

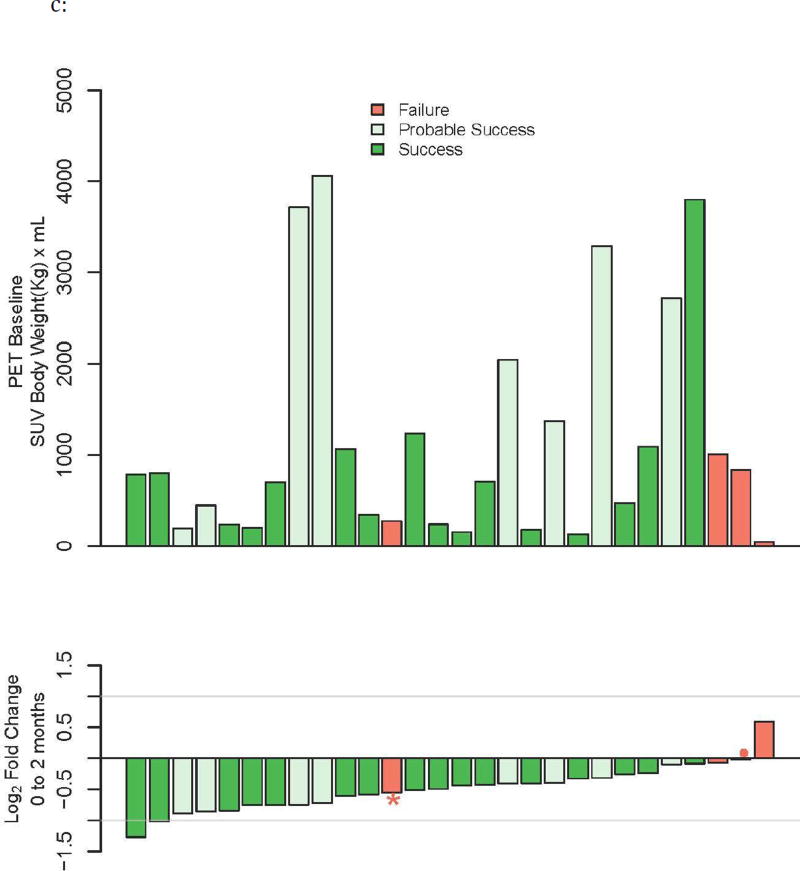

c: Waterfall plot of change in PET total glycolytic activity and correlation with treatment outcomes.

Figure 2.

a: ROC curves for correlation between treatment success with change in sputum culture conversion (solid and liquid), CT reader scores (Area Under the Curve [AUC] 0.78, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.52–1.0), automated CT abnormal softer volume (−500 to −100 HU; AUC 0.57, 95% CI 0.19–0.81), automated CT abnormal harder volume (−100 to 200 HU; AUC 0.91, 95% CI 0.78–1.0), and PET (AUC 0.86, 95% CI 0.59–1.0) at 2 months.

b: ROC curves for correlation between change in CT at 6 months and treatment outcomes. CT reader score Area Under the Curve [AUC] 0.82, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.58–1.0); automated CT abnormal softer volume (−500 to −100 HU) AUC 0.88, 95% CI 0.72–1.0; automated CT abnormal harder volume (−100 to 200 HU) AUC 0.98, 95% CI 0.93–1.0.

Concordance correlation coefficients between the three readers across the ten features were generally low, with values of 0.72, 0.46, and 0.68 for the concordance between readers 1 and 2, 1 and 3, and 2 and 3, respectively for total disease burden. Results were similarly low when evaluating concordance of change from baseline to six months, with values of 0.55, 0.63, and 0.58 for the concordance between readers 1 and 2, 1 and 3, and 2 and 3, respectively (Supplemental Tables 1–5).

CT Automated Algorithm

We also developed a quantitative software algorithm to computationally extract the volume of diseased lung. The lung region was segmented by sequentially removing external contiguous structures including bone and soft tissues of the chest and back walls (Figure 3a). This was followed by automated detection of the carina and growing of contiguous areas of low radiodensity (less than −350 Hounsfield units [HU]) and assigning these as lung-associated. A third step that relabeled high-density voxels as lung voxels within the thorax using the ribs as a boundary was implemented because of the extensive disease and collapse in many subjects. Histograms of lung voxels according to HU radiodensity were exported. These histograms revealed prominent abnormal density in a window ranging from −500 to +200 HU that appeared to be disease-associated. Visually this abnormal density appeared to capture most of the apparent disease from the CT scans although this window of density also captured larger airways and blood vessels present within the lung (Figure 3b). Summing the total volume of abnormal high density (−100 to +200 HU) for each study visit allowed us to calculate the baseline volume and log2-fold change in volumes at two and six months, as shown in the waterfall plots in Figure 1b, ranked according to log-fold changes at six months.

Figure 3.

a: Automated CT model image showing how the chest is stripped down to the lungs.

b: Representative reconstructed automated CT volume images at 0, 2, and 6 months using Hounsfield unit densities >−200.

Similar to reader scores, baseline severity of disease was not predictive of final treatment outcome but change in abnormal CT volume was somewhat predictive at two months and more predictive at six months. In the ROC analysis, the decrease in overall automated abnormal density CT volume at 2 months had an AUC of 0.80 (95% CI: 0.59–1.0). At 6 months, log-fold change in overall abnormal volume gave an AUC of 0.97 (95% CI 0.91–1.0). This seemingly large increase in AUC is due to the small numbers in our analysis and is not statistically significantly different, only representing a change in four subjects, from 19/24 correctly classified at 2 months to 23/24 at 6 months (Table 1a).

Table 1.

| a: Sensitivity and specificity of 2-month sputum culture conversion, CT change, and PET change to predict treatment outcomes. | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Modality | Sensitivity: P (Responder| true success) |

Specificity: P (Non-responder| failures) |

| PET (two months) | 0.96 (23/24)† | 0.75 (3/4)† |

| Automated CT (six months): HU −100 to 200 | 0.96 (23/24)† | 0.75 (3/4)† |

| Automated CT (two months): HU −100 to 200 | 0.79 (19/24)† | 0.75 (3/4)† |

| Culture-solid (two months) | 0.79 (19/24) | 0.5 (2/4) |

| Smear (two months) | 0.75 (18/24) | 0.5 (2/4) |

| Culture-liquid (two months) | 0.58 (14/24) | 0.5 (2/4) |

| b: Comparision of the sensitivities between the different imaging and laboratory modalities. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Modality | PET | CT6 | CT2 |

| Solid | NS | NS | NS |

| Smear | NS | NS | NS |

| Liquid | 0.008 | 0.016 | NS |

Estimates have been corrected for bias in selection of optimal threshold using cross-validation.

It is likely that abnormal densities at HU −500 to +200 become less dense as they return to normal lung. As such, the volume of the densest lesions may be more sensitive to improvement than the total volume of abnormal lung. In fact, the AUC of the volume of harder abnormal lesions (HU density −100 to +200) increased to 0.91 (95% CI 0.78–1.0) at 2 months (Figure 2a), with a threshold that maximized the sum of sensitivity and specificity corresponding to a cross-validated sensitivity of 0.79 and specificity of 0.75 (Table 1a). At 6 months, the AUC of harder abnormal lesions was 0.98, 95% CI 0.93–1.0 (Figure 2a), with an optimal sensitivity of 0.96 and specificity of 0.75 (Table 1a). This was similar to the AUC for overall abnormal lesions. If the subject with poor adherence was excluded, AUC for harder lesions at 2 months decreased slightly to 0.88 (95% CI 0.73–1.0) and increased slightly at 6 months to 0.99 (95% CI 0.95–1.0).

PET changes on therapy

Most obvious abnormalities in these subjects’ lungs showed significantly higher than background rates of FDG uptake. Maximum SUVs observed were as high as 10–12 but there were also examples of cold lesions, although generally these looked like old lesions from previous TB episodes that did not change over the course of the study. Cavities and their associated processes showed substantial uptake although this was often heterogeneous across the circumference of the cavity. Small nodular lesions generally showed lower uptake although the SUVs were not corrected for partial volume effects so this may not be general. Lesions within most subjects showed substantial decreases in FDG avidity at two months after treatment initiation (Figure 4). To quantify this effect, two nuclear medicine readers independently delineated 3D regions of interest (ROIs) from each PET scan (using MIM Maestro software ver. 5.6.5, MIM Software Inc, Cleveland, OH), and determined total glycolytic activity within these ROIs at baseline and at 2 months of treatment. Concordance correlation coefficients between the two readers were high at baseline (0.89), at 2 months (0.89), and for the change between baseline and two months (0.95). Because of the high degree of correlation, only reader two’s scores were subsequently used for the analysis. Both readers found that the majority of subjects had at least a 50% decrease in overall FDG avidity at two months (Fig. 1c), compared with relatively modest changes in CT abnormalities (Fig 1b, middle).

Figure 4. PET/CT scan of a subject at study entry and after two months of treatment.

This scan shows a subject with right middle and lower lobe disease and no involvement of the left lung. In this representation voxels between −100 and 200 Hounsfield units are labeled gray (smoothed for clarity in the top views but unsmoothed from the primary data in the lower views). FDG uptake is represented by a red to yellow scale ranging from an SUV of 4 to 8. This subject has a fan collapse of the right middle lobe and extensive abnormalities in the right lower lobe posteriorly. These parenchymal abnormalities resolve significantly at the two-month time point by CT and have minimal FDG uptake by two months while the collapse of the middle lobe retains FDG uptake and shows only minimal resolution.

The aggregate statistic of total glycolytic activity did not reflect the heterogeneity of response we observed even within individual patients which appears to be more highly correlated with lesion type. An example of this is shown in Fig 4 where the bulk of parenchymal lesions in the right lower lobe of this patient show dramatic resolution while a collapsed middle lobe shows a considerably slower response (in fact the SUVmax in this region increased from 7 to 8 during this time interval against a background of overall disease resolution).

Total glycolytic activity at baseline and the corresponding log2-fold change at two months for each subject are shown by waterfall plot, ranked according to the change at two months (Figure 1c). Baseline severity again did not correlate with treatment outcome. Except for the one subject with poor adherence, all other treatment failure subjects grouped to the right, indicating either an increase in glycolytic activity or minimal changes, at two months. In the ROC analysis, PET AUC was 0.86 (95% CI 0.59–1.0) (Figure 2a), with an optimal threshold selection that gives sensitivity of 0.96 and specificity of 0.75 (Table 1a). When the poorly adherent subject was excluded, the AUC increased to 1.0.

Comparative analysis of biomarkers of successful treatment

As in other trials, sputum smear and culture at two months was only somewhat effective at predicting long-term outcome in our study (Table 1a). In comparing the sensitivities of the different radiological and laboratory modalities with respect to treatment outcome (Table 1b), PET at 2 months and CT at 6 months were better than liquid culture at 2 months (p=0.008 and p=0.016, respectively). Other differences were not statistically significant.

Lesion density analysis

Abnormal lung density in these subjects spanned a wide range of radiodensity (from −500 to +300 HU) and represents an array of different pathological abnormalities. We examined the correlation of these different densities with the semi-quantitative values from the reader study to look for an association between lesion types and density. Cavities, consolidations, and fibrosis all showed significant positive associations with the higher density abnormalities while the smaller nodular lesions all showed stronger correlations with the lower HU densities (Figure 5). The four densest lesions were consolidation, cavity, fibrosis, and bronchial thickening, which overlap with the three CT reader features (bronchial thickening, consolidation, cavity; Supplemental Figure 1) that significantly predicted treatment outcome.

Figure 5.

Correlation plot of 10 CT features and Hounsfield unit (HU) density. Triangles indicate statistical significance at P<0.001 using the bootstrap.

Discussion

Extensive efforts have been made to identify biomarkers for tuberculosis that can reliably identify different stages of disease (latent vs. active), measure degree of treatment response (being cured vs. failing), quantitate risk of disease activation or relapse, or measure protective immunity, e.g. from vaccination (1, 35). A validated biomarker would not only have major implications for routine clinical care but also could be applied to clinical trials of new drugs, vaccines, or diagnostics as a surrogate endpoint to shorten the overall duration of the trials. The current biomarker for which there is the greatest experience in predicting non-relapsing cure is sputum culture conversion at two months of treatment (36), with one analysis arguing that these data are robust enough to serve as a surrogate endpoint in new drug registration trials (37). Despite this, the low sensitivity and specificity of culture in one meta-analysis (2) show that there is still much room for improvement.

The objective of our study was to evaluate candidate biomarkers that would better predict final treatment outcome in pulmonary MDR-TB subjects than two-month sputum culture conversion rates. We examined three different methodologies – semi-quantitative CT readings at two and six months, automated CT quantitation at two and six months, and quantitative PET analysis at two months. In our analysis, change in PET total glycolytic activity from baseline to two months and change in automated CT quantitation of abnormal lung volume from baseline to six months both predicted final treatment outcome six months after EOT reasonably well. Although both PET at two months and automated CT at six months were more sensitive than sputum smear or solid culture conversion at two months, these differences were not statistically significant, possibly because of the small sample size in our study. Future studies should evaluate this with larger sample size; based on the observed differences in sensitivity between PET and solid culture conversion (at two months), a sample size of 60 treatment successes would be required achieve 90% power. Our sample size of 24 treatment successes only gives a power of about 32%. Thus, in this preliminary, hypothesis-generating analysis with small numbers, the results of PET change at two months and CT change at six months suggest that these are potential imaging biomarkers of non-relapsing cure. The expense of PET and CT preclude their widespread use in patient management but this technology has expanded to many middle-income countries where TB is endemic and is available for use in clinical trials. These techniques may provide useful phase 2 endpoints or intermediate endpoints in a multi-stage, multi-arm study. [JID?] Alternatively, they may offer information that more efficiently identifies active drugs and drug combinations prior to undertaking a large and expensive Phase 3 study.

The nature and the magnitude of the PET and CT characteristics encountered in this cohort also suggest that additional metrics that describe the heterogeneity of the response may be of considerable use in characterizing responses to specific drugs and combining them in a more rational way. The spectrum of lesion types and the response of these lesions to treatment reflect a variety of host and bacterial factors that contribute to ultimate outcome. A more detailed characterization of the response rates of specific lesion types will require a larger data set and better analytical tools but offers an attractive extension of the methodology developed here. The magnitude of the PET response at 2 months, and the reproducibility of its measurement, supports looking even earlier for characteristic changes in radiologic features associated with sterilizing cure.

The primary limitation of our analysis is our small total sample size, which limits the power of our comparisons. In addition, the small number of subjects who failed treatment precluded further, more in-depth analyses of factors associated with failure and which, if any, of the 10 CT reader features were most associated with failure. Reader variability was high for most features that were semi- quantitatively evaluated, an observation similar to that in oncology reader studies. In oncology variability between readers has been highest in complex lesions with poorly defined margins and most concordant when analyzing well-circumscribed tumors (38). TB lesions are very similar to complex tumors so our concordance coefficients between readers were not that different from similar studies in oncology (39, 40). Various strategies have been identified in oncology to attempt to minimize intra-observer variability; larger numbers of subjects and larger numbers of readers have had some success. More encouraging computational image analysis techniques similar to what we report here are now being more widely explored and are promising techniques for future studies (41). Also similar to the experience in oncology (42), we found outstanding reader agreement in evaluating FDG PET data.

In summary, we believe these preliminary data constitute a proof-of-concept of the possibility of using imaging biomarkers early in the course of treatment to predict final tuberculosis treatment outcome in the context of clinical trials of new TB drugs and regimens. This is supported not only by the data in this paper but also in our companion paper using imaging biomarkers in macaques which further suggests that PET/CT could offer a directly translatable tool for piloting human clinical trials in a highly relevant animal model (43). In addition our initial observations that FDG avidity changes with treatment with different kinetics in lesions representing different pathologies may offer a more meaningful way of selecting drug combinations that address the full range of pathologies observed in TB patients. Additional work is needed to confirm this concept with larger datasets to better understand how well and in what contexts this predictive imaging biomarker model works best. If validated by additional data, both PET and CT imaging biomarkers have the potential to serve as surrogate endpoints in future clinical trials of new drugs, allowing a significantly shortened total trial duration, reduced costs, and faster time to trial results and public health benefit.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

A randomized, double blind, placebo controlled, phase II trial was conducted at the National Masan Hospital (NMH) in Changwon, South Korea from 2005–2012 and has been previously described (32). Adult pulmonary MDR-TB subjects were enrolled and received an individualized background treatment regimen for their MDR-TB for at least 18 months following sputum culture conversion, per World Health Organization guidelines. In addition, subjects were randomized to add metronidazole 500 mg three times daily vs. placebo for the initial two months. Subjects were followed until six months after the end of therapy for final treatment outcomes.

CT Reader Study

A high resolution CT (HRCT) scan (120 kV, 250 mA, 0.75 sec, 1 mm × 1 mm slice thickness) was done at baseline, 2 months, and 6 months following treatment initiation. Three independent radiologists scored each sextant of the lung of all CT scans according to the presence of ten features: nodules less than 2 mm, centrilobular nodules/linear lesions 2–4 mm thick, tree-in-bud opacities, 4–10 mm nodules, consolidations, cavities, ground glass opacities, bronchial thickening, collapse, and fibrosis (33, 34). Images were scored for each feature according to the percent involvement in each lung sextant based on the following scale: 0=no involvement, 1=1–25%, 2=26–50%, 3=51–75%, 4=76–100%. A fourth radiologist evaluated the scores of the three primary radiologists to provide an adjudicated score by independently reviewing the three scores and CT images.

CT Automated Algorithm

Using an automated CT structure analysis algorithm developed in-house, the pulmonary CT scan was categorized by voxels into normal lung, abnormal lung, and non-lung voxels. The initial lung region was determined by defining a series of layers in a first pass, performing "layered segmentation". In this pass, a combination of adaptive thresholding, three-dimensional region growing, and component labeling separated the subject's body from the background and any external objects (e.g. clothing), then successively peeled off skin, muscles and fat, skeletal system, and other organs, leaving only low (less than −350) HU intensity voxels of the lungs and trachea. Lung sextants were then defined by first locating the carina, above which were the upper left and right sextants. The rest of the lungs were then divided equally into middle and lower left and right sextants, respectively, with the volume of abnormal voxels in each sextant computationally defined.

A. Locating the Carina

The carina may be difficult to locate in extensive TB disease, particularly under conditions of lung collapse. In collapse, the opposite lung often expands, resulting in gross deformations to the position and layout of the lungs and trachea. To locate the carina under such conditions, several techniques were used including contouring, shape analysis, and fuzzy reasoning.

The first step was to identify a valid seed point in the trachea from which to start the carina tracking process. Because the trachea is a nearly vertical tube filled with air (low HU values) with an expected size range (typically 2 to 4 cm in diameter), we performed contour analysis on the various CT slices and extracted the location and size of ellipsoidal shapes. The individual ellipses are then stacked into tubular shapes upon which length, roundness, and regularity metrics were computed for each resulting tube. Using fuzzy metrics, a score was assigned to each tube and the one corresponding to the trachea was thus selected.

Once a good seed was selected for the trachea, directed cross-sectional analysis was used to track the trachea until the first bifurcation. The center of the bifurcation was recorded as the carina location. Using the carina location information, region growing, and component labeling, low density lung voxels were further labeled as belonging to the trachea or left or right lung.

B. Lung Segmentation

Once the sextants were defined, the rib cage boundary was used to grow the lung regions, particularly when the Hounsfield intensity of the lung region adjoining the ribs was high due to infection/consolidation. Knowledge of the arteries, veins and aorta in the heart-lung boundary region was used to distinguish between abnormal lung tissue and non-lung tissue. The resulting lung is segmented into upper (defined by the area above the carina), middle, and lower (lung below the carina divided in half) sextants in the left and right lungs.

FDG PET

In addition to the HRCT, a PET/CT scan (CT resolution 1.17 mm × 1.17 mm × 3 mm) with FDG was done at baseline and 2 months following treatment initiation. Two independent nuclear radiologists identified all regions of uptake within the lung to provide a total glycolytic activity using standardized uptake value (SUV) for a given subject at baseline and at two months. Standardized update value at time point t is defined as:

where c is the measured tissue radioactivity concentration (MBq/kg) and injected activity is the amount of radiation (MBq) injected extrapolated to time point t.

Statistical Analysis

Subjects were defined as “success” six months after EOT if they were clinically without disease and had a sputum culture with no growth. “Probable success” was defined as a subject who was a clinical success but without microbiologic confirmation. All other subjects were defined as “failure.” CT reader scores from the adjudicating radiologist were used to evaluate the diagnostic performance. The adjudicated scores for each feature were averaged across sextants to provide a total burden of disease for each feature for a given subject, to account for subjects who did not undergo imaging of the entire lung.

Concordance correlation coefficients (44) describe the agreement in the burden of disease for each feature as evaluated by the three primary radiologists and also by the two nuclear medicine specialists. Log2-fold change from baseline to two months and baseline to six months were computed to describe the relative improvement or worsening of disease. Waterfall plots and non-parametric ROC analysis visualized the relationship between imaging biomarkers and ultimate treatment outcome. Non-parametric areas under the ROC curve (AUC) evaluated statistical significance (45).

To compare the sensitivities and specificities of the imaging biomarkers with those of culture, thresholds were defined for each imaging biomarker. For each modality and time-point (log-fold change from baseline to 2 and 6 months), the threshold corresponding to the largest sensitivity + specificity was selected. To adjust for over-estimation of these parameters due to optimal selection, cross-validated sensitivity and specificity values were reported. Test statistics comparing these values to culture were estimated using a cross-validation procedure as well.

Correlation plots were constructed using Spearman rank correlations using the corrplot function in R (46) based on the sextant-level data at baseline. P-values were obtained using a bootstrap procedure to account for multiple sextants per subject. All statistical analyses were conducted using R version 2.15.1 and Stata version 12.

Supplementary Material

Accessible summary.

In this and our companion study, we explore quantitative PET/CT scan changes in both nonhuman primates and humans as early surrogate markers of treatment efficacy in tuberculosis. In one study, linezolid and the second-generation oxazolidinone AZD5847 demonstrated reduced bacterial load at necropsy and significantly reduced FDG PET avidity and CT-quantified lung pathology in Mtb infected cynomolgus macaques. Similar PET/CT changes were seen in human extensively drug-resistant Mtb patients treated with linezolid. Our second study corroborated this effect in a prospective human multidrug-resistant tuberculosis treatment study where early PET/CT changes predicted final treatment outcomes. Larger studies confirming these results are needed.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients who volunteered to participate in this study.

Funding: Funding for this study was provided (in part) by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, U.S. National Institutes of Health; and (in part) by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea.

Footnotes

Author contributions: ML, DJ, MWC, JDL, YJJ, SL, LCG, YC, LEV, SKP, SNC, and CEB designed and implemented the metronidazole study and PET/CT substudy; DAH, JMM, HZ, MTC, and PH read the PET and CT scans; PP, NZ, SL, MT, AR, and SS developed the automated CT reading software; LED conducted the statistical analyses; RYC and CEB drafted the manuscript; all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Wallis RS, Kim P, Cole S, Hanna D, Andrade BB, Maeurer M, Schito M, Zumla A. Tuberculosis biomarkers discovery: developments, needs, and challenges. The Lancet infectious diseases. 2013;13:362–372. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70034-3. published online EpubApr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horne DJ, Royce SE, Gooze L, Narita M, Hopewell PC, Nahid P, Steingart KR. Sputum monitoring during tuberculosis treatment for predicting outcome: systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet infectious diseases. 2010;10:387–394. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70071-2. published online EpubJun. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benator D, Bhattacharya M, Bozeman L, Burman W, Cantazaro A, Chaisson R, Gordin F, Horsburgh CR, Horton J, Khan A, Lahart C, Metchock B, Pachucki C, Stanton L, Vernon A, Villarino ME, Wang YC, Weiner M, Weis S C. Tuberculosis Trials. Rifapentine and isoniazid once a week versus rifampicin and isoniazid twice a week for treatment of drug-susceptible pulmonary tuberculosis in HIV-negative patients: a randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2002;360:528–534. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09742-8. published online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson JL, Hadad DJ, Dietze R, Maciel EL, Sewali B, Gitta P, Okwera A, Mugerwa RD, Alcaneses MR, Quelapio MI, Tupasi TE, Horter L, Debanne SM, Eisenach KD, Boom WH. Shortening treatment in adults with noncavitary tuberculosis and 2-month culture conversion. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2009;180:558–563. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200904-0536OC. published online EpubSep 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phillips PP, Nunn AJ, Paton NI. Is a 4-month regimen adequate to cure patients with non-cavitary tuberculosis and negative cultures at 2 months? The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2013;17:807–809. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0725. published online EpubJun. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phillips PP, Fielding K, Nunn AJ. An evaluation of culture results during treatment for tuberculosis as surrogate endpoints for treatment failure and relapse. PloS one. 2013;8:e63840. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kato H, Nakajima M. The efficacy of FDG-PET for the management of esophageal cancer: review article. Annals of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery : official journal of the Association of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgeons of Asia. 2012;18:412–419. doi: 10.5761/atcs.ra.12.01954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poeppel TD, Krause BJ, Heusner TA, Boy C, Bockisch A, Antoch G. PET/CT for the staging and follow-up of patients with malignancies. European journal of radiology. 2009;70:382–392. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.03.051. published online EpubJun. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu G, Zhao L, He Z. Performance of whole-body PET/CT for the detection of distant malignancies in various cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2012;53:1847–1854. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.105049. published online EpubDec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paul NS, Ley S, Metser U. Optimal imaging protocols for lung cancer staging: CT, PET, MR imaging, and the role of imaging. Radiologic clinics of North America. 2012;50:935–949. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2012.06.007. published online EpubSep. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maziak DE, Darling GE, Inculet RI, Gulenchyn KY, Driedger AA, Ung YC, Miller JD, Gu CS, Cline KJ, Evans WK, Levine MN. Positron emission tomography in staging early lung cancer: a randomized trial. Annals of internal medicine. 2009;151:221–228. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00132. W-248; published online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Margolis ML. The PET and the pendulum. Annals of internal medicine. 2009;151:279–280. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00134. published online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Truong MT, Munden RF, Movsas B. Imaging to optimally stage lung cancer: conventional modalities and PET/CT. Journal of the American College of Radiology : JACR. 2004;1:957–964. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2004.07.007. published online EpubDec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sathekge M, Maes A, Kgomo M, Stoltz A, Pottel H, Van de Wiele C. Impact of FDG PET on the management of TBC treatment. A pilot study. Nuklearmedizin. Nuclear medicine. 2010;49:35–40. doi: 10.3413/nukmed-0270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heysell SK, Thomas TA, Sifri CD, Rehm PK, Houpt ER. 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography for tuberculosis diagnosis and management: a case series. BMC pulmonary medicine. 2013;13:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-13-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofmeyr A, Lau WF, Slavin MA. Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in patients with cancer, the role of 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography for diagnosis and monitoring treatment response. Tuberculosis. 2007;87:459–463. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2007.05.013. published online EpubSep. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goo JM, Im JG, Do KH, Yeo JS, Seo JB, Kim HY, Chung JK. Pulmonary tuberculoma evaluated by means of FDG PET: findings in 10 cases. Radiology. 2000;216:117–121. doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.1.r00jl19117. published online EpubJul. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tian G, Xiao Y, Chen B, Guan H, Deng QY. Multi-site abdominal tuberculosis mimics malignancy on 18F-FDG PET/CT: report of three cases. World journal of gastroenterology : WJG. 2010;16:4237–4242. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i33.4237. published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Demura Y, Tsuchida T, Uesaka D, Umeda Y, Morikawa M, Ameshima S, Ishizaki T, Fujibayashi Y, Okazawa H. Usefulness of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography for diagnosing disease activity and monitoring therapeutic response in patients with pulmonary mycobacteriosis. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. 2009;36:632–639. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-1009-5. published online EpubApr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim IJ, Lee JS, Kim SJ, Kim YK, Jeong YJ, Jun S, Nam HY, Kim JS. Double-phase 18F-FDG PET-CT for determination of pulmonary tuberculoma activity. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. 2008;35:808–814. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0585-0. published online EpubApr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinez V, Castilla-Lievre MA, Guillet-Caruba C, Grenier G, Fior R, Desarnaud S, Doucet-Populaire F, Boue F. (18)F-FDG PET/CT in tuberculosis: an early non-invasive marker of therapeutic response. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2012;16:1180–1185. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0010. published online EpubSep. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sathekge M, Maes A, Kgomo M, Stoltz A, Van de Wiele C. Use of 18F-FDG PET to predict response to first-line tuberculostatics in HIV-associated tuberculosis. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2011;52:880–885. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.083709. published online EpubJun. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park IN, Ryu JS, Shim TS. Evaluation of therapeutic response of tuberculoma using F-18 FDG positron emission tomography. Clinical nuclear medicine. 2008;33:1–3. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e31815c5128. published online EpubJan. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tian G, Xiao Y, Chen B, Xia J, Guan H, Deng Q. FDG PET/CT for therapeutic response monitoring in multi-site non-respiratory tuberculosis. Acta radiologica. 2010;51:1002–1006. doi: 10.3109/02841851.2010.504744. published online EpubNov. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang YH, Lin AS, Lai YF, Chao TY, Liu JW, Ko SF. The high value of high-resolution computed tomography in predicting the activity of pulmonary tuberculosis. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2003;7:563–568. published online. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kosaka N, Sakai T, Uematsu H, Kimura H, Hase M, Noguchi M, Itoh H. Specific high-resolution computed tomography findings associated with sputum smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis. Journal of computer assisted tomography. 2005;29:801–804. doi: 10.1097/01.rct.0000184642.19421.a9. published online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ors F, Deniz O, Bozlar U, Gumus S, Tasar M, Tozkoparan E, Tayfun C, Bilgic H, Grant BJ. High-resolution CT findings in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis: correlation with the degree of smear positivity. Journal of thoracic imaging. 2007;22:154–159. doi: 10.1097/01.rti.0000213590.29472.ce. published online EpubMay. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakanishi M, Demura Y, Ameshima S, Kosaka N, Chiba Y, Nishikawa S, Itoh H, Ishizaki T. Utility of high-resolution computed tomography for predicting risk of sputum smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis. European journal of radiology. 2010;73:545–550. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.12.009. published online EpubMar. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeh JJ, Yu JK, Teng WB, Chou CH, Hsieh SP, Lee TL, Wu MT. High-resolution CT for identify patients with smear-positive, active pulmonary tuberculosis. European journal of radiology. 2012;81:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.09.040. published online EpubJan. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poey C, Verhaegen F, Giron J, Lavayssiere J, Fajadet P, Duparc B. High resolution chest CT in tuberculosis: evolutive patterns and signs of activity. Journal of computer assisted tomography. 1997;21:601–607. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199707000-00014. published online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee JJ, Chong PY, Lin CB, Hsu AH, Lee CC. High resolution chest CT in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis: characteristic findings before and after antituberculous therapy. European journal of radiology. 2008;67:100–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.07.009. published online EpubJul. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carroll MW, Jeon D, Mountz JM, Lee JD, Jeong YJ, Zia N, Lee M, Lee J, Via LE, Lee S, Eum SY, Lee SJ, Goldfeder LC, Cai Y, Jin B, Kim Y, Oh T, Chen RY, Dodd LE, Gu W, Dartois V, Park SK, Kim CT, Barry CE, 3rd, Cho SN. Efficacy and safety of metronidazole for pulmonary multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2013;57:3903–3909. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00753-13. published online EpubAug. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hatipoglu ON, Osma E, Manisali M, Ucan ES, Balci P, Akkoclu A, Akpinar O, Karlikaya C, Yuksel C. High resolution computed tomographic findings in pulmonary tuberculosis. Thorax. 1996;51:397–402. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.4.397. published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Casarini M, Ameglio F, Alemanno L, Zangrilli P, Mattia P, Paone G, Bisetti A, Giosue S. Cytokine levels correlate with a radiologic score in active pulmonary tuberculosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1999;159:143–148. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9803066. published online EpubJan. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maertzdorf J, Weiner J, 3rd, Kaufmann SH. Enabling biomarkers for tuberculosis control. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2012;16:1140–1148. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0246. published online EpubSep. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wallis RS, Pai M, Menzies D, Doherty TM, Walzl G, Perkins MD, Zumla A. Biomarkers and diagnostics for tuberculosis: progress, needs, and translation into practice. Lancet. 2010;375:1920–1937. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60359-5. published online EpubMay 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wallis RS, Wang C, Doherty TM, Onyebujoh P, Vahedi M, Laang H, Olesen O, Parida S, Zumla A. Biomarkers for tuberculosis disease activity, cure, and relapse. The Lancet infectious diseases. 2010;10:68–69. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70003-7. published online EpubFeb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McErlean A, Panicek DM, Zabor EC, Moskowitz CS, Bitar R, Motzer RJ, Hricak H, Ginsberg MS. Intra- and interobserver variability in CT measurements in oncology. Radiology. 2013;269:451–459. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13122665. published online EpubNov. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Erasmus JJ, Gladish GW, Broemeling L, Sabloff BS, Truong MT, Herbst RS, Munden RF. Interobserver and intraobserver variability in measurement of non-small-cell carcinoma lung lesions: implications for assessment of tumor response. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21:2574–2582. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.144. published online EpubJul 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hopper KD, Kasales CJ, Van Slyke MA, Schwartz TA, TenHave TR, Jozefiak JA. Analysis of interobserver and intraobserver variability in CT tumor measurements. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 1996;167:851–854. doi: 10.2214/ajr.167.4.8819370. published online EpubOct. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parmar C, Rios Velazquez E, Leijenaar R, Jermoumi M, Carvalho S, Mak RH, Mitra S, Shankar BU, Kikinis R, Haibe-Kains B, Lambin P, Aerts HJ. Robust radiomics feature quantification using semiautomatic volumetric segmentation. PloS one. 2014;9:e102107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paidpally V, Mercier G, Shah BA, Senthamizhchelvan S, Subramaniam RM. Interreader agreement and variability of FDG PET volumetric parameters in human solid tumors. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2014;202:406–412. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.10841. published online EpubFeb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coleman MT, Chen RY, Lee M, Lin PL, Dodd LE, Maiello P, Via LE, Kim Y, Marriner G, Dartois V, Scanga C, Janssen C, Wang J, Klein E, Cho SN, Barry CE, 3rd, Flynn JL. PET/CT monitoring demonstrates a therapeutic response to oxazolidinones in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infected macaques and humans. Sci Trans Med. 2014 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009500. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin LI. A concordance correlation coefficient to evaluate reproducibility. Biometrics. 1989;45:255–268. published online. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pepe MS. The statistical evaluation of medical tests for classification and prediction. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wei T. corrplot: Visualization of a correlation matrix. R package version 0.71. 2013 http://cran.r-project.org/package=corrplot.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.