Summary

Membrane transporters move substrates across the membrane by alternating access of their binding sites to one side of the membrane at a time. An emerging model is the elevator mechanism in which a substrate-binding transport domain moves a large distance across the membrane. This mechanism has been characterized by a transition between two states but the conformational path leading to the transition is not yet known, largely because the available structural information has been limited to the two end states. Here we present crystal structures of a concentrative nucleoside transporter from Neisseria wadsworthii representing inward-facing, intermediate, and outward-facing states. Interestingly, we determined the structures of multiple intermediate conformations in which the transport domain is captured halfway through its elevator motion. Our structures present a trajectory of the conformational transition in the elevator model, revealing multiple intermediate steps and state-dependent conformational changes within the transport domain associated with the elevator-type motion.

Secondary active transporters translocate substrates across the membrane against their concentration gradients by coupling to ion movement (typically Na+ or H+) down electrochemical gradients 1,2. Central to this thermodynamically uphill process is that a substrate-binding site interchanges accessibility between the extracellular and intracellular sides of the membrane 3,4. Prevailing models for this alternating access are the rocker-switch and rocking bundle mechanisms wherein the substrate-binding site is fixed and the rocking motion of the protein domain(s) forms barriers above or below the substrate-binding site in an alternating fashion 5–7. Recently, the elevator model has emerged wherein a mobile transport domain containing the substrate-binding sites moves as a rigid-body along a static scaffold domain to achieve alternating access 5,8,9. This mechanism was first put forth by crystal structures of the aspartate transporter GltPh in inward- and outward-facing conformations 9,10, and further characterized by biophysical studies 11–14. Recent reports on sodium-coupled transporters suggest that the elevator mechanism is more widely utilized than previously thought 15–18.

The elevator motion has been inferred as a single rigid-body transition mainly because crystal structures were available for only the two end states 9,10,16,17. This has led to many questions about the structural transition between the two end states. Is the motion composed of a single or multiple steps? Does the transport domain move as a rigid body or does it undergo conformational changes? How do interactions between the transport and scaffold domains change while preventing non-specific ion leakage and hysteresis? Interestingly, smFRET and EPR studies of GltPh suggest the presence of an intermediate step between the inward and outward states 13,19. However, without structural information for intermediate states, it is difficult to probe transitional steps of the mechanism. Here we present structures of a concentrative nucleoside transporter in inward-substrate-bound, inward-open, multiple intermediate, and outward-open conformations. Our findings provide many new structural and mechanistic insights into the conformational pathway of the elevator transition of this secondary active transporter.

Uridine-bound inward-occluded conformation

CNTs utilize sodium or proton gradients to transport nucleosides for DNA and RNA synthesis 20–22. Furthermore, they mediate cellular uptake of nucleoside-analog drugs for the treatment of cancer and viral infection 23–25. We previously determined structures of Vibrio cholerae CNT (vcCNT) in complex with nucleosides and nucleoside-analogs in the presence of sodium, all of which adopt an inward-occluded conformation 26,27. Because vcCNT is resistant to crystallization in alternate conformations, we screened additional orthologs and identified a CNT from Neisseria wadsworthii (CNTNW) that is stable in the absence of sodium and nucleoside (Extended Data Fig. 1). CNTNW mediates sodium-dependent nucleoside transport similar to vcCNT and binds uridine when solubilized in detergent (Extended Data Fig. 2). We first obtained the sodium- and uridine-bound structure of CNTNW, which adopts an inward-occluded conformation nearly identical to vcCNT (Cα r.m.s.d of 0.7 Å). The overall fold is composed of two domains: a transport domain, containing transmembrane helices (TM1, TM2, TM5 and TM8), helical hairpins (HP1 and HP2), and partially unwound helices (TM4 and TM7), and a scaffold domain, consisting of TM6 and TM3, that is involved in trimerization (Extended Data Fig. 2). The nucleoside-binding site is formed by HP1, HP2, and the unwound parts of TM4 and TM7, and the putative sodium-binding site is located between the tip of HP1 and the unwound portion of TM4. TM6 is speculated to serve as a hydrophobic barrier to nucleoside transport 26. The nucleoside-binding site is located below TM6 where the top of the transport domain (TM4b and HP2b) interacts with the scaffold domain (TM3 and TM6), sealing off access to the extracellular space (Extended Data. Fig. 2).

Outward-facing conformation

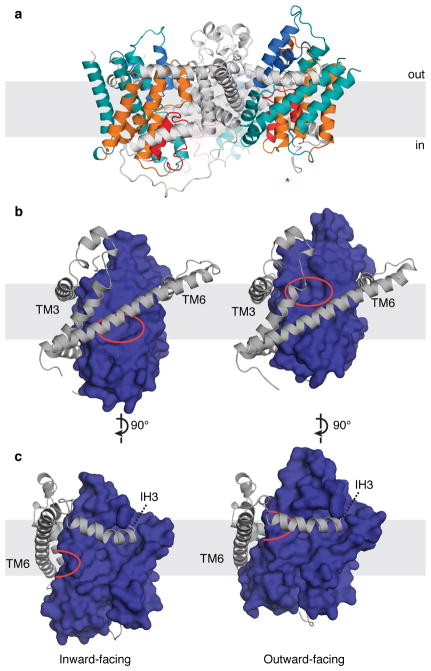

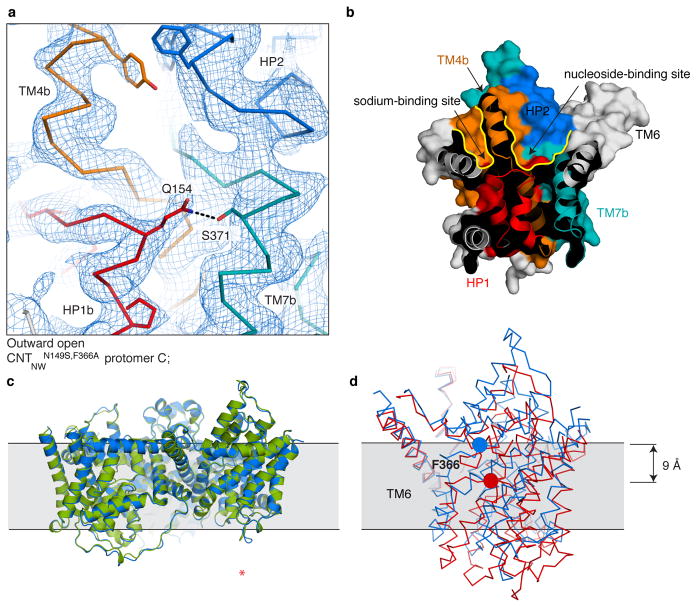

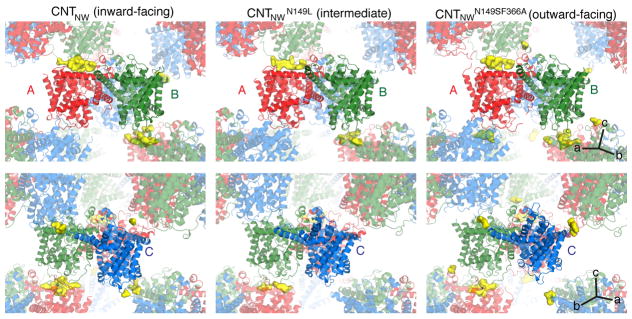

We then introduced two mutations, Asn149Ser and Phe366Ala, to disrupt sodium and nucleoside binding of CNTNW, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 2) 27. We crystallized CNTNWN149S,F366A and collected data to 3.45 Å (Extended Data Table 1). Two protomers (protomers A and B) adopted a nearly identical inward-facing conformation as wild-type CNTNW except for structural changes in HP1 (see below). Surprisingly, the third protomer (protomer C) adopts a conformation distinct from the other protomers (Fig. 1). Only TM3 and TM6 are unchanged while the remaining transmembrane helices move a large distance toward the extracellular side. The translocation of the transport domain involves a ~12 Å upward movement and an ~18o pivot with respect to the membrane plane. Unlike GltPh, the transport domain of CNTNWN149S,F366A does not twist significantly relative to the membrane normal. This movement places the sodium- and nucleoside-binding sites above TM6, making both sites accessible to the extracellular side. Therefore, we propose that this new conformation represents the outward-facing-open state. Interestingly, the sodium-binding site is accessible to the extracellular side through a separate portal (Extended Data. Fig. 3).

Figure 1. The outward-facing conformation of CNTNWN149S,F366A.

a, One protomer in CNTNWN149S,F366A adopts an outward-facing conformation (*). Scaffold domain (grey); TM1, TM7, TM8 (teal); TM2, TM4, TM5 (orange); HP1 (red); HP2 (blue). b–c, Inward- (left) and outward-facing (right) protomers from the trimerization axis (b) and 90 degrees rotated (c). The ~12-Å movement of the transport domain (blue) shifts the substrate-binding sites (red circle) past TM6.

We crystallized an additional mutant, Asn149Ser/Glu332Ala (CNTNWN149S,E332A), in which both binding sites were disrupted 27. CNTNWN149S,E332A adopts a similar conformation as CNTNWN149S,F366A, suggesting that the outward-facing conformation is not unique to the particular mutations, but rather due to the shift in equilibrium toward the substrate-free state (Extended Data Fig. 3). There is substantial disparity between the positions of the transport domains in the outward-facing structure of CNTNWN149S,F366A and the previously proposed outward-facing homology model of vcCNT (Cα r.m.s.d of 7.9 Å) (Extended Data Fig. 3) 28.

Intermediate conformations

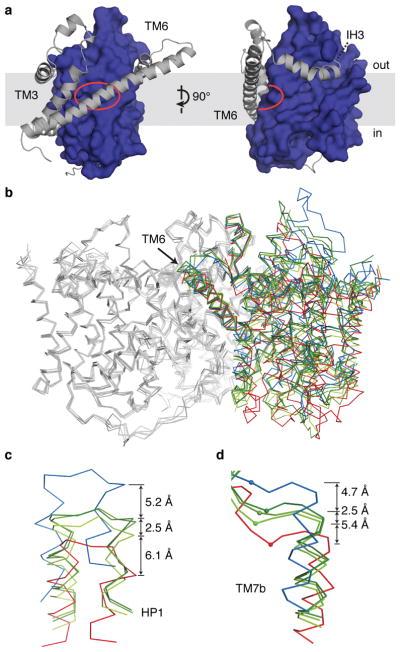

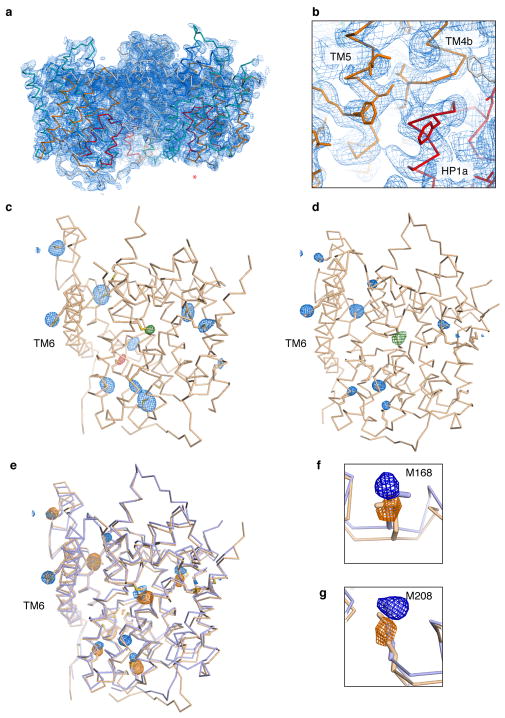

We introduced the mutation Asn149Leu in CNTNW, which reduces affinity and flux for uridine more substantially than Asn149Ser (Extended Data Fig. 2). We obtained CNTNWN149L crystals that diffracted to 3.55–4.2 Å (Extended Data Table 1 and Extended Data Fig. 4). Similar to CNTNWN149S,F366A, protomers A and B adopt a nearly identical inward-facing conformation as wild-type except for structural changes in HP1 (see below). Surprisingly, in protomer C, the transport domain assumes a position strikingly different from both the inward- and outward-facing states (Fig. 2). The transport domain is positioned about halfway between the end states, placing the substrate-binding site behind TM6. Furthermore, we solved many structures of CNTNWN149L from different crystals and found that the location and conformation of the transport domain are slightly different in each structure and can be clustered into three groups (Extended Data Fig. 5). We refer to these crystals as CNTNWN149L-1 (intermediate 1), CNTNWN149L-2 (intermediate 2), and CNTNWN149L-3 (intermediate 3), with intermediate 1 being closest to the inward-facing state and intermediate 3 closest to the outward-facing state (Fig. 2). Selenium anomalous scattering, comparison of each model with each map, log-likelihood gain analysis, and refinement statistics show that these intermediate structures are reliably built and discernible (Extended Data Figs. 4 and 5, Extended Data Table 1). Crystal packing explains why only protomer C shows different conformations, as the transport domains of protomers A and B are involved in packing interactions while protomer C is free to move (Extended Data Fig. 6).

Figure 2. The intermediate conformations of CNTNWN149L.

a, In the CNTNWN149L structures the transport domain (blue) resides halfway between the inward- and outward-facing states, with substrate-binding sites (red circle) behind TM6. b, Overlay of CNTNW (red), CNTNWN149L (green), and CNTNWN149S,F366A (blue). In each CNTNWN149L structure two protomers face inward while the third protomer is in an intermediate state. c–d, HP1 (c) and TM7b (d) positions. Phe366 (Cα) is shown in spheres.

When all the structures are aligned, HP1 of the transport domain moves ~6 Å from the inward-facing state to intermediate 1 and ~5 Å from intermediate 3 to the outward-facing state (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Video).

Physiological relevance of the new conformations

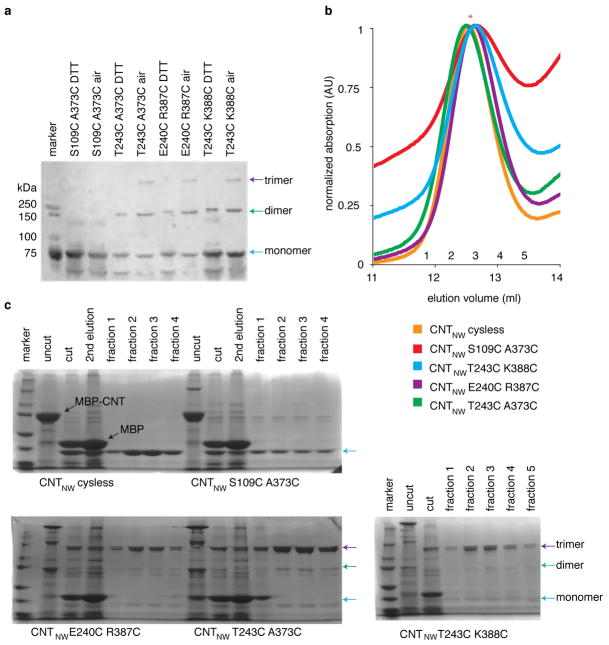

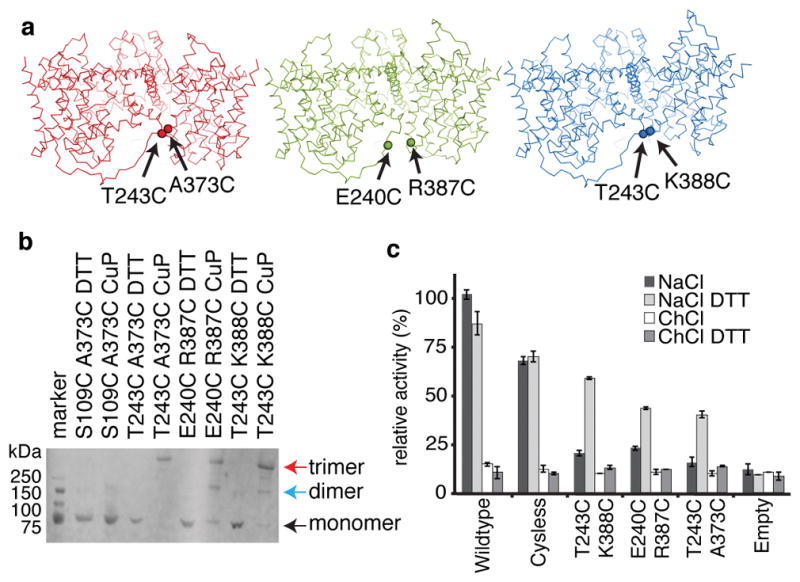

We performed cross-linking experiments to test whether the new conformations are physiologically relevant. In a functionally competent Cys-less background (Cys364Ser), we introduced one cysteine mutation into the transport domain and another into the scaffold domain of the neighboring protomer so that disulfide cross-linking leads to a covalently linked trimer. We mutated residues that are within cross-linking distance only in one state but not the others (Fig. 3). We found that disulfide cross-linking spontaneously occurred to some extent in isolated membranes for each crosslinking mutant (Extended Data Fig. 7). Cross-linking reached near completion upon addition of the oxidant copper phenanthroline (CuPhe) and could be reduced by DTT (Fig. 3). Detergent-solubilized mutants spontaneously cross-linked to near completion (Extended Data Fig. 7). The negative control (S109C, A373C), carrying mutations far from one another in all conformations, did not cross-link.

Figure 3. Cysteine cross-linking in membranes.

a, Cysteine pairs for inward-facing (red), intermediate (green), and outward-facing (blue) conformations. b, Western blot of MBP-CNTNW cross-linking mutants in crude membranes. Data is representative of three independent experiments. c, Relative activity of CNTNW cross-linking mutants measured by flux assay in proteoliposomes, in the presence (NaCl) or the absence (ChCl) of sodium gradient. Average of six experiments (four for wildype DTT), (technical replicates), error bar indicates s.e.

To functionally probe the new conformations, we reconstituted spontaneously cross-linked mutants into proteoliposomes (Extended Data Fig. 7) and performed uridine flux assays (Fig. 3). We reasoned that if we lock the transporter in one state, it would not be able to transport nucleosides, but when reduced by DTT, it would regain transport activity. We found that the cross-linked mutants are nearly inactive, but when reduced the transport activity is restored substantially (Fig. 3). Since the cross-linking mutants did not include the mutations utilized for crystallization, we conclude that the newly observed conformations reflect physiologically relevant states.

State-dependent structural changes

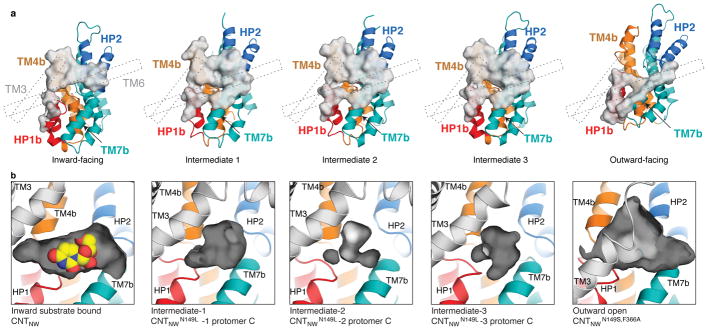

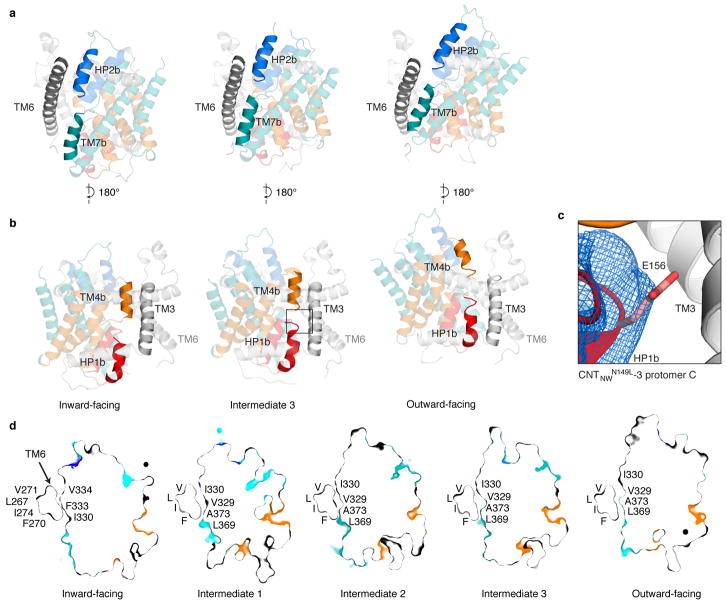

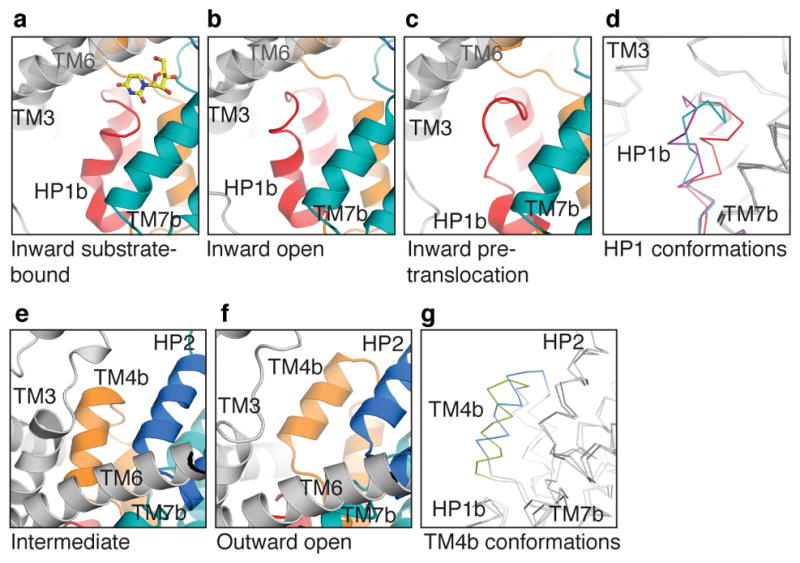

During the elevator-like motion, the transport domain changes its interactions with the scaffold domain in a state-dependent manner. The interface is made up of HP1b, HP2b, TM4b, and TM7b on the transport domain and TM3 and TM6 on the scaffold domain (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Figs. 8). In the inward-facing state, TM4b and HP2b interact with the scaffold domain to close off the binding sites from the extracellular side. In the intermediate states, HP1b, HP2b, TM4b, and TM7b interact with the scaffold domain, rendering both substrate-binding sites inaccessible to both sides of the membrane. Accordingly, a more extensive interface appears to be formed in these intermediates (~1800 Å2) than in the inward-facing (~1400 Å2) and outward-facing (~1700 Å2) states (Fig. 4a). The interface is mainly composed of hydrophobic amino acids, except for Glu156 on HP1 (Extended Data Fig. 8). In the outward-facing conformation, HP1b and TM7b interact with the scaffold domain to shield the binding sites from the cytoplasm.

Figure 4. State-dependent changes in the transport domain.

a, Buried surface area (grey) in each conformation shows state-dependent changes in interactions between the scaffold (dashed lines) and transport domains (colored as Fig. 1). b, In the intermediate states the binding-site cavity (grey) is compacted and incompatible with uridine (yellow) binding.

In the intermediate states, the substrate-binding sites are occluded from both sides of the membrane, leaving no room for ions to leak through (Fig. 4b). Intriguingly, the size of the nucleoside-binding site gradually decreases as the transport domain moves toward the middle intermediate state (intermediate 2). This suggests that during the elevator transition, the transport domain becomes compact at the intermediate states and expands at the two end states.

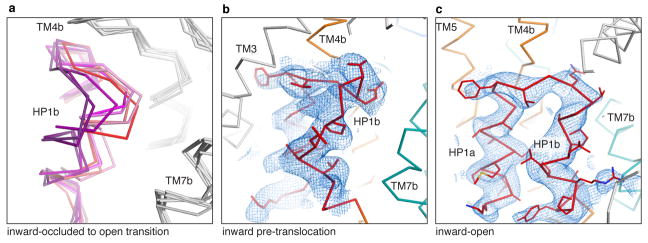

The roles of HP1b and TM4b as gates

Although HP1b, HP2b, TM4b, and TM7b of the transport domain are involved in dynamic interactions with the scaffold domain, only the conformations of HP1b and TM4b change substantially. While protomers A and B adopt inward-facing conformations in CNTNWN149S,F366A and CNTNWN149L crystals, HP1 from these protomers adopts conformations notably different from the inward-occluded substrate-bound state. The conformations of HP1 can be largely categorized into three groups (Fig. 5 and Extended Data Fig. 9). The first group, from the substrate-bound conformation, finds HP1 close to the nucleoside as HP1b interacts with its nucleobase via water molecules, as shown in vcCNT (Extended Data Fig. 2) 27. In the second group, HP1b is rotated out ~30° and moved ~6 Å compared to the substrate-bound conformation, positioning HP1b away from the nucleoside-binding site and exposing both binding sites to the cytoplasm. We believe that this represents an inward-open state. Overlays of protomers with similar HP1 conformations show different degrees of HP1b rotation, providing snapshots of the transition from the inward-occluded to the inward-open state (Extended Data Fig. 9). We found a third, less populated group with HP1b unwound and the tip of HP1 reaching toward Phe366, the center of the nucleoside-binding site. We speculate that this conformation represents an inward-facing pre-translocation state. In the inward-open state, HP1b sticks out toward the cytoplasm below TM6 such that upward movement toward the outward-facing state would result in a steric clash. Therefore, after the nucleoside and sodium are released, a conformational rearrangement of HP1b, as seen in structural group 3, is necessary to progress through the transport cycle. Taken together, HP1 serves as an intracellular gate by changing its conformation at HP1b (Supplementary Video).

Figure 5. Intracellular and extracellular gates.

a–c, HP1 conformations in CNTNW (a), CNTNWN149L-1 (b), and CNTNWN149L-2 (c) (colored as Fig 1.) d, Transport domain overlay of three HP1 states: inward-occluded (red), inward-open (purple), and inward-pre-translocation (teal). e–f, TM4b in intermediate CNTNWN149L-3 (e) and outward-facing CNTNWN149S,F366A (f). g, Transport domain overlay of intermediate (green) and outward-facing (blue) structures shows the upward movement of TM4b.

In the intermediate and outward-facing states, HP1 assumes conformations similar to the inward-facing substrate-bound state. The minor change is that HP1b rotates and moves up toward the nucleoside-binding site due to the interaction between Gln154 on HP1b and Ser371 on TM7b, two residues involved in nucleoside binding (Extended Data Fig. 3). In the intermediate states TM4b is pushed down toward the nucleoside-binding site compared to the two end states (Fig. 5). These rearrangements of HP1 and TM4b make the transport domain more compact in the intermediate states, rendering the hydrophilic nucleoside-binding site smaller and inaccessible to either side of the membrane (Figs. 4b and 5g and Extended Data Fig. 8). Interestingly, from intermediate 3 to the outward-facing conformation, TM4b moves up and away from the nucleoside-binding site by ~5 Å (Fig. 5g). This motion not only renders the nucleoside-binding site accessible to the extracellular side but also leads to the creation of an extracellular portal to the sodium-binding site (Extended Data Fig. 3). We therefore suggest that TM4b serves as an extracellular gate.

Discussion

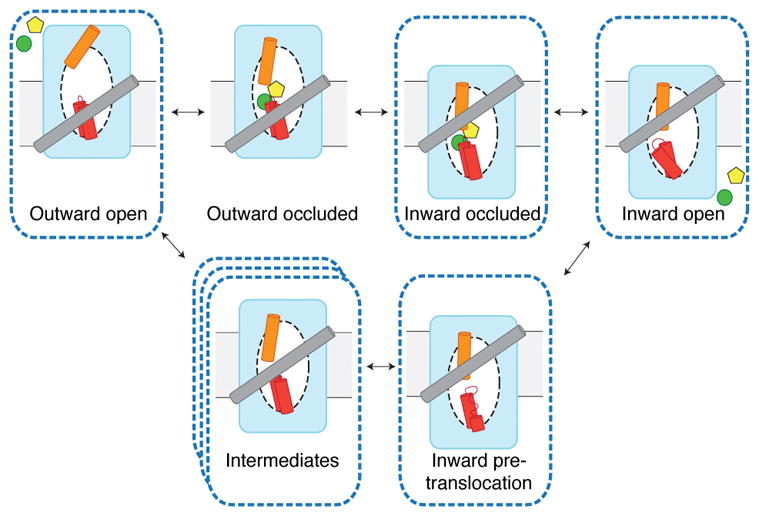

Our structures of CNTNW represent the inward-occluded (substrate-bound), inward-open, inward-pre-translocation, intermediate, and outward-open states, illustrating the conformational pathway between the two end states (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Video). Previously, a structure of GltPh representing an inward-facing “unlocked” state was reported where the interactions between the transport and scaffold domains were loosened 12. However, our intermediate states are distinct in that the transport domain moves halfway through the membrane. These intermediate structures provide new insights into the elevator mechanism, suggesting that the elevator motion involves intermediate steps rather than a single rigid-body motion. Why do these intermediate states exist? A possible role is to guide the conformational path of the repetitive large-scale motions of the transport domain and thus prevent hysteresis and non-specific ion leakage. Consistent with this idea, in the intermediate states, the transport domain is more compact and its hydrophilic nucleoside-binding site is occluded by interactions with the scaffold domain. Another possibility is that these intermediate states serve as a barrier for the transition between the end states. Interestingly, smFRET studies of GltPh showed that the transport domain visits an intermediate step that serves as a barrier between the end states 13. Without these intermediates, uninterrupted switching between the end states in the absence of nucleoside would result in sodium leakage. Consistent with this idea, the interactions between the transport and the scaffold domains are most extensive in the intermediate states of CNTNW. It is noteworthy that mutation of the glutamate residue on HP1 in human CNT1 and CNT3 (Glu321 in hCNT1 and Glu343 in hCNT3) leads to nucleoside-uncoupled sodium leak currents 29,30. Interestingly, the corresponding residue in CNTNW (Glu156) is the only charged residue located at the domain interface in the intermediate states (Extended Data. Fig. 8).

Figure 6. Elevator-mechanism of CNT.

Movement of the transport domain (blue) provides alternating access of the binding sites (white oval) and transport of nucleoside (yellow) and sodium (green). HP1 (red) and TM4b (orange) act as gates. Available crystal structures (dashed outlines) include new intermediate conformations.

Our structural observations of the intermediate states in the absence of substrates leads to a question regarding whether similar states exist when the transporter is bound to sodium and nucleoside. If these states exist, the nucleoside-binding site must adopt different conformations to accommodate nucleosides, as nucleoside cannot be bound in the compacted transport domain of the substrate-free intermediate states (Fig. 4).

Our new structures also show that different gates (HP1b and TM4b) are responsible for each end state. While HP1b serves as a gate in the inward-facing state, it remains largely unchanged in the other states. TM4b changes its conformation in each state. In particular, TM4b plays a major role in making the transport domain more compact in the intermediate states. In short, our structural work suggests that the transport domain undergoes state-dependent conformational changes rather than a single rigid-body motion during its elevator-like movement.

Methods

Expression and purification

CNTNW was expressed from a modified pET26 vector containing a pelB leader sequence and an N-terminal PreScission Protease cleavable His10-maltose-binding-protein tag, as described previously for vcCNT 26. Protein was expressed in C41 cells for 4h at 37°C. SeMet labeled protein was expressed in C41 cells grown in M9 media supplemented with 100 mg/mL lysine, phenylalanine, and threonine; 50 mg/mL isoleucine, leucine, and valine; and 60 mg/mL SeMet at time of induction 31. After expression SeMet labeled protein was purified the same as non-labeled protein. Cells were lysed by sonication and membrane proteins were extracted from the lysate in 30 mM dodecyl maltoside. The insoluble fraction was removed by centrifugation and CNT was purified from the supernatant by Co2+-affinity chromatography. Protein was digested overnight with PreScission Protease. The protein was exchanged to decyl maltoside neopentyl glycol (DMNG) for crystallization and isothermal titration calorimetry experiments or decyl maltoside (DM) for proteoliposome preparation by concentration and subsequent dilution in the new detergent. The sample was applied to a Superdex 200 size-exclusion column pre-equilibrated with 20 mM Tris pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, and 4 mM DM or 0.5 mM DMNG. For crystallization and ITC experiments in the absence of sodium, sodium was removed from the purification in the wash step of affinity chromatography and subsequent buffers contained 150 mM KCl instead of NaCl. For crosslinking experiments, protein was purified in the absence of DTT.

Crystallization

Protein was concentrated to ~10 mg ml−1 and mixed with the crystallization solution at a 1:1 ratio in 24-well sitting drop trays. Crystals grew in a wide range of conditions, but crystals grown in the following conditions were used in structure determination. The structure of wild-type CNTNW was solved from crystals grown in 1 M NaCl, 35% PEG400, pH 9.5; CNTNWN149L-1 grew in 50 mM Mg(OAc)2, 30% PEG400, 100 mM KCl, pH 7.5; CNTNWN149L-2 grew in 50 mM Mg(OAc)2, 30% PEG400, pH 7.5; CNTNWN149S,F366A crystallized in 50 mM Mg(OAc)2, 30% PEG400, pH 7.5; and CNTNWN149S,E332A crystallized in 200 mM choline chloride, 14% Poly(ethylene glycol) monomethyl ether 2000 (PEG MME 2000), pH 6.5. Crystals of SeMet labeled protein were grown in the following conditions: CNTNWN149L-3 (purified in presence of 5 mM TCEP and 10 mM DTT in the size-exclusion chromatography buffer) grew in 10 mM Mg(OAc)2, 25% PEG400, pH 7.0 (crystals were grown in a wide range of pHs but the best diffracting data was obtained from the crystal grown in pH 7.0); CNTNWN149L-1 crystallized in 10 mM Mg(OAc)2, 25% PEG400, pH 7.5, 3% DMSO; Se marker mutant CNTNWN149L,L159M in the intermediate 1 conformation crystallized in 75 mM Mg(OAc)2, 25% PEG400, pH 7.0, 3% DMSO; Se marker mutant CNTNWN149L,V328M in the intermediate 1 conformation crystallized in 25 mM Mg(OAc)2, 30% PEG400, pH 7.0, 100 mM KCl; and Se marker mutant CNTNWN149L,V328M in the intermediate 3 conformation crystallized in 25 mM Mg(OAc)2, 25% PEG400, pH 7.5, 3% DMSO. Crystals were transferred to a cryo solution containing 35% PEG400 and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Structure determination

Data were collected at the Advanced Photon Source, beamlines 22-ID and 24ID-C. The native data were processed with iMosfilm 32, SeMet data of CNTNWN149L-3 were processed with HKL2000 33, and the remaining SeMet data were processed with XDS 34. Data for CNTNWN149L-1 were anisotropically truncated to 4.2 Å × 4.2 Å × 4.1 Å using the UCLA Anisotropy Server (http://services.mbi.ucla.edu/anisoscale/) 35. For wild-type CNTNW, molecular replacement was performed using the vcCNT monomer (PDB ID: 3TIJ) using PHASER 36. For molecular replacement of CNTNWN149L, CNTNWN149S,F366A, and CNTNWN149S,E332A, solutions for protomers A and B were found using wild-type CNTNW as a search model. As for protomer C, transport and scaffold domains were used as separate search models after observing a significant domain movement. The connecting regions between the domains such as interfacial helices were built manually during refinement. Coot 37 and PHENIX 38 were used to refine the structures. Refinement of protomers A and B was restrained by non-crystallographic symmetry (NCS) and reference model (wild-type CNTNW) until near convergence. Protomer C was refined using secondary structure restraints generated from wild-type CNTNW. Manual refinement of protomer C was performed initially only by rigid-body fitting of whole domains. The sizes of the rigid bodies were gradually decreased to individual helices as the electron density map improved. Only when the main chain location was accurately determined were the side chain positions refined. To determine the conformation of HP1 in each structure, omit maps were generated and HP1 was rebuilt manually into positive density. Near convergence the NCS and reference model restraints were released. Each structure was analyzed using MolProbity 39 and further refined to minimize clashes and optimize geometry. The structures were aligned on protomers A and B to visualize and quantify the movement of protomer C. The sidechain of certain residues in the interface between the transport and scaffold domain and binding site cavity were not supported by electron density. Therefore, these residues were truncated to the Cβ position in the deposited coordinates. However, to provide a more accurate representation of the interactions, the side chains of these residues, built as the most likely rotamer, were included for the analysis of the interface and binding site. The buried surface area was calculated in PyMOL with a high sampling density (dot_density 3) using the following equation: ((solvent accessible surface area of the transport domain alone) + (solvent accessible surface area of TM3 and TM6)) - (solvent accessible surface area of the transport domain, TM3 and TM6 together). The binding site cavity was created by selection of cavity-lining residues shown in surface cavity mode in PyMOL40 and clipped for clarity. Anomalous difference Fourier maps of the SeMet-substituted and Se marker mutants were calculated using MR phases of two protomers (A and B), excluding protomer C. Single anomalous dispersion phases of CNTNWN149L-3 were calculated using these Se sites from anomalous difference Fourier maps followed by solvent flattening using AutoSol 38.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

DMNG-solubilized CNTNW protein, purified in the absence or presence of sodium, was concentrated to 25 μM. Uridine (3 mM) was titrated into the protein solution 4 μL at a time using a MicroCal VP-ITC system. For ITC experiments of CNTNWN149L, 12 mM uridine was titrated 2 μL at a time into an 80 μM protein solution using a MicroCal ITC200 system. The data were fit to a single-site binding isotherm.

Vesicle reconstitution and flux assay

Protein purified in DM was reconstituted into lipid vesicles as described previously 41. Briefly, lipid vesicles were prepared consisting of 10 mg ml−1 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (POPE) and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol (POPG) in a 3:1 POPE:POPG ratio. Protein was reconstituted in the lipid vesicles at a 1:500 protein to lipid mass ratio. The vesicles contained 20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 200 mM KCl, and 100 mM choline chloride (ChCl). Vesicles were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until further use.

For flux experiments, vesicles were thawed and frozen 3 times prior to extrusion through a 1 μm filter. For flux assay experiments with the cysteine cross-linking mutants, the vesicles were incubated with or without 10 mM DTT at 37°C for 10 min prior to extrusion. The vesicles were diluted 20 times into flux assay buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 100 mM KCl, and 200 mM ChCl or NaCl). The flux assay was performed with 2 μM radioactively labeled uridine and 1 μM valinomycin at 30 °C for 5 min. Vesicles were harvested on GF/B glass microfiber filters and counted by scintillation.

Cross-linking experiments

Cross-linking mutants of CNTNW were prepared in a Cys-less background. The following mutants were cloned by QuikChange mutagenesis: Cys-less mutant CNTNWC364S, negative control CNTNWS109C,C364S,A373C, inward-facing cross-linking mutant CNTNWT243C,C364S,A373C, intermediate cross-linking mutants CNTNWE240C,C364S,R387C, and outward-facing cross-linking mutants CNTNWT243C,C364S,K388C. For membrane cross-linking experiments, protein was expressed for 1h at 37°C and cells were harvested by centrifugation. Cells were lysed by sonication and lysate was spun down twice at 6660 × g for 15 min at 4°C, followed by a high-speed spin (120,000 × g for 1 h) of the supernatant to pellet the membrane fraction. The membrane was resuspended in assay buffer (20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl). The crude membrane was sonicated 2 × 1 min in a water bath sonicator and incubated for 20 min at room temperature with 20 μM copper phenantroline or 10 mM dithiothreitol. The cross-linking reaction was quenched by addition of 20 μM N-ethylmaleimide and 50 mM EDTA. Loading buffer with 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate and 4 M urea was added to the samples. The samples were incubated at 60 °C for 10 min prior to loading onto an SDS-PAGE gel for Western blot analysis using an anti-histidine tag primary antibody (Sigma-Aldrich catalog number H1029; antibody-validation information is available at http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/product/sigma/h1029?lang=en®ion=US) and an anti-mouse secondary antibody (Licor catalog number 926-32212; antibody-validation information is available at https://www.licor.com/documents/x8h1udxje8ker0tcaf8q7utpleagu4tv). For gel source data, see Supplementary Figure 1. For proteoliposome reconstitution, cross-linking mutants were prepared the same as liposomes with wild-type protein.

Data availability statement

The sequence of CNTNW can be found in the National Center for Biotechnology Information under accession code WP_009116906. Atomic coordinates and structure factors for the reported crystal structures are deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession codes 5L26 (substrate-bound inward-facing, CNTNW), 5L27 (intermediate-1, CNTNWN149L-1), 5L24 (intermediate-2, CNTNWN149L-2), 5U9W (intermediate-3, CNTNWN149L-3), 5L2A (outward-facing, CNTNWN149S,F366A), and 5L2B (outward-facing, CNTNWN149S,E332A).

Extended Data

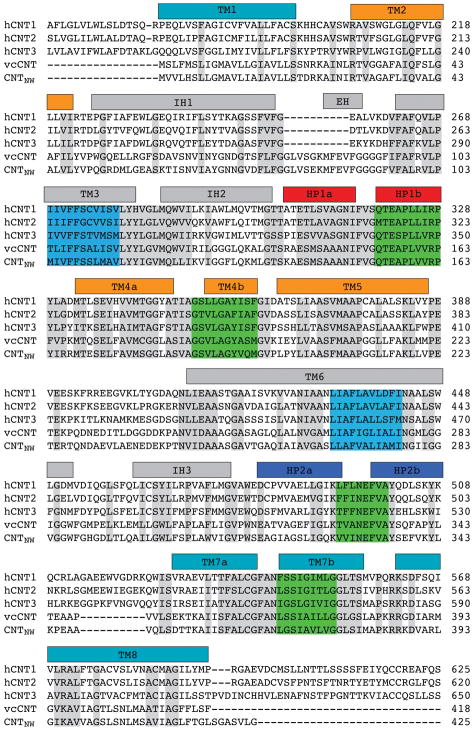

Extended Data Figure 1. Sequence alignment of the human CNT isoforms with vcCNT and CNTNW.

Bars representing helices are colored as in Fig. 1. Grey highlight indicates sequence conservation. Blue and green highlights indicate regions involved in state-dependent interactions between the scaffold and transport domains, respectively. The N-terminal 150–180 residues of the hCNTs are omitted for clarity since they are not present in vcCNT and CNTNW.

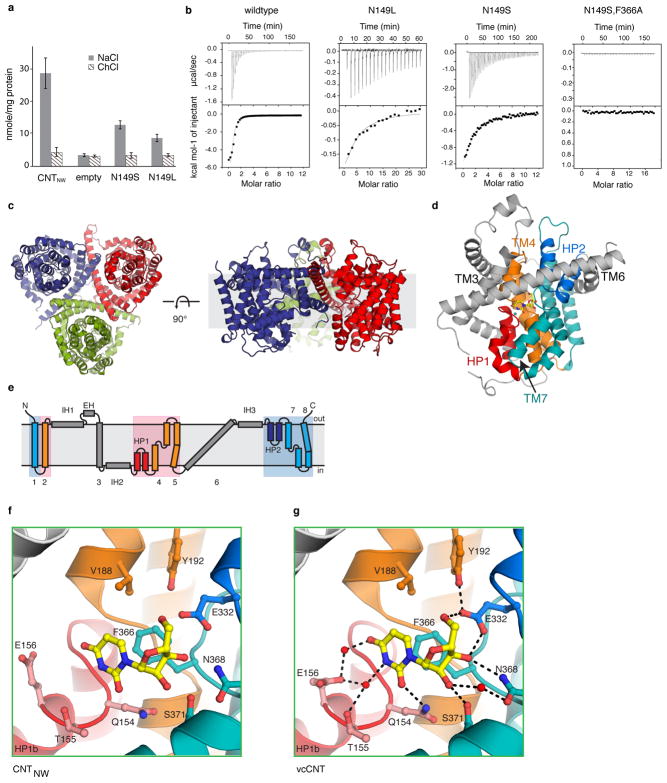

Extended Data Figure 2. Functional characterization of CNTNW and its structure in complex with sodium and uridine.

a, Radioactive uridine flux in proteoliposomes requires a sodium gradient. Average of n = 3 for wild-type and empty vesicles and n = 9 for mutants (technical replicates), error bar indicates s.e. b, Isothermal titration calorimetry of CNTNW, data fit to one-site binding curve for CNTNW (dissociation constant (Kd) = 4.5 μM, enthalpy change (ΔH°) = −8.1 kcal/mol), CNTNWN149L (Kd = 847.5 μM, ΔH° = −1.8 kcal/mol), CNTNWN149S (Kd = 30.8 μM, ΔH° = −2.4 kcal/mol), and CNTNWN149S,F366A (no binding observed).c, CNTNW trimer viewed from the intracellular side (left) and within the membrane plane (right). d, CNTNW viewed from the trimerization axis, colored as in Fig. 1, with uridine in yellow, sodium in green. e, CNT topology diagram, colored as in Fig. 1. f–g, Detailed view of the nucleoside-binding sites for CNTNW (f) and vcCNT (g). The configuration of the binding sites is nearly identical, except for Glu156 which adopts a different rotamer conformation in CNTNW.

Extended Data Figure 3. Quality of the structure and electron density of the outward-facing structure.

a, 2Fo − Fc simulated annealing (SA) composite omit map, calculated using 3,000 K, is shown at 1 σ for the outward-facing protomer region in the CNTNWN149S,F366A crystal structure. The model is shown in ribbon representation with side chains in line representation where supported by the density, colored as in Fig. 1. b, Cutout surface and cartoon representation of the outward-facing conformation, colored as in Fig. 1. Two separate paths, outlined in yellow, provide access to either the sodium- or nucleoside-binding pockets. c, Cartoon representation of the crystal structures of two sodium- and nucleoside-binding mutants, CNTNWN149S,F366A (blue) and CNTNWN149S,E332A (green). The structures overlay with an overall Cα r.m.s.d. of 0.5 Å. CNTNW trimer viewed from within the membrane plane. The asterisk denotes the outward-facing protomer. d, Comparison of the outward-facing crystal structure (blue) with the repeat-swap-modeled outward-facing conformation (red, Protein Model DataBase PM0080188). In the crystal structure Phe366 (blue circle) was found 9.7 Å closer to the extracellular side of the membrane than in the modeled structure (red circle). The Cα r.m.s.d. of the transport domain alone is 7.9 Å, showing a substantial difference between the two structures.

Extended Data Figure 4. Experimentally phased map of CNTNW149L-3 and anomalous signals from SeMet-labeled CNTNW149L-1 and CNTNW149L-3 guided model building.

An overview (a) and detailed view (b) of the electron density map of CNTNWN149L-3, solved by single anomalous dispersion phasing followed by solvent flattening at 3.55 Å. The experimentally phased map is shown in blue mesh at 1 σ, the model is shown in ribbon representation with side chains as sticks where supported by the density, colored as in Fig. 1. The asterisk denotes the outward-facing protomer. c–g, Anomalous difference Fourier maps were calculated using the MR phases of protomers A and B of CNTNWN149L-1 at 6 Å (c) and for CNTNWN149L-3 at 3.6 Å (d) (blue mesh at 3.5 σ). Two mutants were designed to carry an additional methionine in HP1, CNTNWN149L,L159M (red mesh at 2.5 σ in the intermediate 1 state at 4.6 Å) and HP2, CNTNWN149L,V328M (green mesh at 2.5 σ in the intermediate 1 state at 5 Å and in the intermediate 3 state at 6 Å). The locations of methionine residues in the models of CNTNWN149L-1 and CNTNWN149L-3 agree well with the locations of Se anomalous peaks. e, The anomalous maps and models for intermediates 1 (beige) and 3 (blue) were overlaid to compare the locations of anomalous peaks. The positions of anomalous markers in the transport domain are in distinct locations in each intermediate structure. f–g, Close-up view of two methionine residues, Met168 and Met208, in the transport domain of intermediates 1 (beige) and 3 (blue) and their corresponding Se anomalous difference peaks.

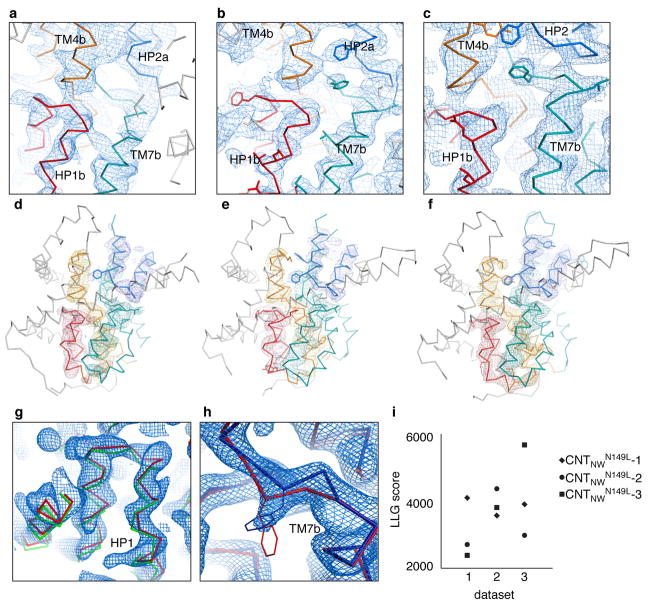

Extended Data Figure 5. Quality of the electron density in the three CNTNWN149L crystal structures.

a–c, A detailed view of the 2Fo − Fc SA composite omit maps of the intermediate state protomers using 3,000 K at 1 σ. d–f,Fo − Fc SA omit maps, calculated at 3,000 K, shown at 2.2 σ for HP1 (red), TM4 (orange), HP2 (blue), and TM7 (teal). Models are shown in ribbon representation with side chains as sticks where supported by the density, colored as in Fig. 1. g–h, Each model fits poorly into the electron density of another intermediate state (2Fo - Fc maps at 1). g, The models of CNTNWN149L −1 (green) and CNTNWN149L −2 (red) shown in the density of CNTNWN149L −2. CNTNWN149L −1 does not fit well in the density of CNTNWN149L −2. h, The models of CNTNWN149L −2 (red) and CNTNWN149L −3 (blue) shown in the density of CNTNWN149L −3. CNTNWN149L −2 does not fit well in the density of CNTNWN149L −3. i, Log-likelihood-gain (LLG) scores of molecular replacement, using MR-phaser, with the refined structure of each intermediate model in each of the datasets. The resolution was cut off at 4.1 Å in order to enable comparison of the LLG scores. For each intermediate the appropriate model has an LLG score substantially higher than the incorrect models.

Extended Data Figure 6. Crystal packing in the wild-type (inward-facing), CNTNWN149L-3 (intermediate), and CNTNWN149S,F366A (outward-facing) crystals.

Crystal contacts are mostly mediated by protomers A (red) and B (green) in each crystal. This provides protomer C (blue) with sufficient space to enable movement of the transport domain within the same crystal packing. Crystal packing interactions are shown as yellow surfaces.

Extended Data Figure 7. CNTNW cysteine cross-linking mutants, except for the negative control (CNTNWS109C,A373C), spontaneously cross-link to form covalent trimers.

a, Western blot of MBP-CNTNW cross-linking mutants in crude membrane preparations. Each cross-linking pair, except for the negative control, cross-links spontaneously to form covalently linked dimers and trimers, and this reaction is reversible by addition of reducing reagent. Data is representative of three independent experiments. b, Cross-linked CNTNW mutants have a similar elution volume in size exclusion chromatography as Cys-less CNT, as shown by size-exclusion chromatography and SDS-PAGE analysis. c, The purified cysteine cross-linking mutants were analyzed by Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE before and after PreScission protease treatment to remove the MBP-His tag. After PPX treatment, monomeric, dimeric, and trimeric CNTNW can be seen in the SDS-PAGE gel, indicated by the blue, green, and purple arrows, respectively. Air-oxidized protein in the peak fraction (*) was reconstituted into proteoliposomes for the flux assay shown in Fig. 3.

Extended Data Figure 8. State-dependent interactions between the transport and scaffold domains.

a, Interactions between TM6 (grey) of the scaffold domain and transport domain elements HP2b (blue) and TM7b (teal) in the inward-facing, intermediate, and outward-facing conformations, colored as in Fig. 1. b, Interactions between TM3 (grey) and transport domain elements TM4b (orange) and HP1b (red), colored as in Fig. 1. The black box indicates the region shown in panel c. c, Based on its Cα location, Glu156, the only charged residue on the transport domain at this interface, appears to be positioned toward the interface with the scaffold domain in the intermediate states. The side chain is modeled as its ideal rotamer and a 2Fo − Fc SA composite omit electron density map (blue mesh, 0.8 σ) is shown. d, Cutout surface depictions show the changes in the specific interactions between TM6 and the transport domain elements HP2b and TM7b during the elevator motion. The interaction network is mostly made up of hydrophobic interactions.

Extended Data Figure 9. HP1 conformational transition and quality of the electron density.

a, Overlay of the transport domain for eight protomers (from the CNTNW, CNTNWN149L-1-3, and CNTNWN149S,F366A crystal structures) showing the transition between the inward-occluded, substrate-bound HP1 conformation (thick red trace) and the inward-facing-open HP1 conformation (thick purple trace). b–c, SA composite omit map (2Fo - Fc maps at 1 σ) around HP1 in the pre-translocation conformation in protomer A of CNTNWN149L-3 (b) and around HP1 in the inward-open conformation in protomer A of CNTNWN149L-1 (c). The electron density is shown as blue mesh. The ribbon representation is colored as in Fig. 1, with side chains shown as lines where supported by the density.

Extended Data Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| CNTNW -uridine (PDB ID: 5L26) |

CNTNWN149L-1 (PDB ID: 5L27) |

CNTNWN149L-2 (PDB ID: 5L24) |

CNTNWN149L-3 SeMet (PDB ID: 5U9W) |

CNTNWN149SF366A (PDB ID: 5L2A) |

CNTNWN149SE332A (PDB ID: 5L2B) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||||||

| Space group | P61 | P61 | P61 | P61 | P61 | P61 |

| Cell dimensions | ||||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 115.2 115.2 264.0 | 116.1 116.1 272.2 | 116.2 116.2 274.6 | 115.6 115.6 272.4 | 119.1 119.1 277.0 | 121.0 121.0 277.4 |

| α, β, γ(°) | 90 90 120 | 90 90 120 | 90 90 120 | 90 90 120 | 90 90 120 | 90 90 120 |

| Resolution (Å) | 3.40 (3.61-3.40) | 4.10 (4.58 - 4.10) | 4.10 (4.58 - 4.10) | 3.55 (3.61 – 3.55) | 3.45 (3.66 – 3.45) | 3.80 (4.10 – 3.80) |

| Rpim | 0.08 (0.61) | 0.06 (0.48) | 0.09 (0.30) | 0.05 (0.69) | 0.09 (0.60) | 0.08 (0.54) |

| I/σ(I) | 4.7 (1.2) | 7.3 (2.4) | 6.3 (2.9) | 16.4 (1.7) | 5.6 (0.5) | 6.2 (2.0) |

| CC1/2 | 1.0 (0.48) | 0.98 (0.69) | 0.91 (0.70) | 0.93 (0.56) | 0.98 (0.76) | 0.99 (0.54) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.7 (99.9) | 99.9 (99.9) | 98.7 (89.4) | 99.9 (98.7) | 99.6 (99.5) | 99.4 (99.8) |

| Redundancy | 7.0 (7.4) | 4.7 (4.7) | 11.0 (9.4) | 8.4 (8.5) | 5.8 (5.3) | 4.3 (4.3) |

| Phasing | SAD | |||||

| Figure of merit (resolution) | 0.38 (50 - 3.6 Å) | |||||

| Refinement | ||||||

| Resolution (Å) | 3.40 (3.52-3.40) | 4.10 (4.25 - 4.10)† | 4.11 (4.25 - 4.11)‡ | 3.56 (3.68 – 3.56) | 3.45 (3.57 – 3.45) | 3.8 (3.94 – 3.80) |

| No. reflections | 27137 (2737) | 16224 (1598) | 16202 (1455) | 24655 (2413) | 29068 (2921) | 22489 (2234) |

| Rwork/Rfree | 24.2/26.6 | 26.9/30.9 | 27.1/29.9 | 25.3/27.6 | 27.3/30.7 | 25.1/29.0 |

| No. atoms | 8985 | 8341 | 8741 | 8669 | 8963 | 8770 |

| Protein | 8702 | 8288 | 8655 | 8616 | 8910 | 8682 |

| Uridine/detergent | 277 | 53 | 86 | 53 | 53 | 88 |

| Sodium (water) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| B factors (Å2) | 88.8 | 128.6 | 74.7 | 123.4 | 71.4 | 90.1 |

| Protein | 87.6 | 128.2 | 74.3 | 123.1 | 71.3 | 89.6 |

| Ion/uridine/detergent | 124.8 | 190.6 | 107.7 | 184.9 | 91.8 | 136.4 |

| Water | 74.3 | |||||

| R.m.s. deviations | ||||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.005 | 0.003 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.72 | 0.71 | 1.06 | 0.97 | 0.87 | 0.72 |

| Ramachandran favored/outliers (%) | 97/0.08 | 95/0.17 | 94/0.00 | 95/0.08 | 94/0.08 | 95/0.08 |

| Molprobity score | 1.24 | 1.41 | 1.95 | 1.77 | 1.75 | 1.69 |

| CNTNWN149L SeMet |

CNTNWN149L,L159M -1 SeMet |

CNTNWN149L,V328M -1 SeMet |

CNTNWN149L,V328M -3 SeMet |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||||

| Space group | P61 | P61 | P61 | P61 |

| Cell dimensions | ||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 114.5 114.5 265.2 | 114.7 114.7 269.9 | 114.0 114.0 265.8 | 114.5 114.5 269.4 |

| α, β, γ(°) | 90 90 120 | 90 90 120 | 90 90 120 | 90 90 120 |

| Resolution (Å) | 4.50 (5.03 – 4.50) | 4.61 (5.15 – 4.61) | 4.01 (4.48 – 4.01) | 3.94 (4.41 – 3.94) |

| Rpim | 0.02 (0.38) | 0.03 (0.70) | 0.02 (0.61) | 0.04 (0.55) |

| I/σ(I) | 19.7 (1.7) | 15.4(1.2) | 16.3 (1.3) | 12.0 (1.5) |

| CC1/2 | 1.00 (0.62) | 1.00 (0.47) | 1.00 (0.63) | 1.00 (0.61) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.1 (93.3) | 100 (100) | 100 (100) | 100 (100) |

| Redundancy | 14.9 (12.3) | 19.1 (19.9) | 16.5 (16.6) | 20.7 (20.7) |

Values in parentheses are for highest-resolution shell.

Data truncated to 4.2 Å, 4.2 Å, 4.1 Å using the UCLA anisotropy server.

Effective resolution is 4.2 Å.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Data were collected at beamlines 24-ID-C and 22-ID in the Advanced Photon Source. We thank B. Kloss and W. Hendrickson from the Center on Membrane Protein Production and Analysis (COMPPÅ) for additional homolog screening, and F. Valiyaveetil, J. Richardson, and D. Richardson for critical manuscript reading. This work was supported by NIH R01 GM100984 (S.-Y.L.) and NIH R35 NS097241 (S.-Y.L.). Beamline 24-ID-C is funded by P41GM103403 and S10 RR029205. COMPPÅ is funded by P41 GM116799 (W. H.).

Footnotes

A supplementary video is included in a separate file.

Author Contributions M.H. and Z.J. crystallized the protein and performed ITC and flux experiments. M.H. solved the structures and carried out cross-linking experiments. S.-Y.L. and M.H. wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Author Information The authors declare no competing financial interests

References

- 1.Krishnamurthy H, Piscitelli CL, Gouaux E. Unlocking the molecular secrets of sodium-coupled transporters. Nature. 2009;459:347–355. doi: 10.1038/nature08143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forrest LR, Kramer R, Ziegler C. The structural basis of secondary active transport mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1807:167–188. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell P. A general theory of membrane transport from studies of bacteria. Nature. 1957;180:134–136. doi: 10.1038/180134a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jardetzky O. Simple allosteric model for membrane pumps. Nature. 1966;211:969–970. doi: 10.1038/211969a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drew D, Boudker O. Shared Molecular Mechanisms of Membrane Transporters. Annu Rev Biochem. 2016;85:543–572. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forrest LR, Rudnick G. The rocking bundle: a mechanism for ion-coupled solute flux by symmetrical transporters. Physiology (Bethesda) 2009;24:377–386. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00030.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Penmatsa A, Gouaux E. How LeuT shapes our understanding of the mechanisms of sodium-coupled neurotransmitter transporters. J Physiol. 2014;592:863–869. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.259051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crisman TJ, Qu S, Kanner BI, Forrest LR. Inward-facing conformation of glutamate transporters as revealed by their inverted-topology structural repeats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:20752–20757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908570106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reyes N, Ginter C, Boudker O. Transport mechanism of a bacterial homologue of glutamate transporters. Nature. 2009;462:880–885. doi: 10.1038/nature08616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yernool D, Boudker O, Jin Y, Gouaux E. Structure of a glutamate transporter homologue from Pyrococcus horikoshii. Nature. 2004;431:811–818. doi: 10.1038/nature03018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akyuz N, Altman RB, Blanchard SC, Boudker O. Transport dynamics in a glutamate transporter homologue. Nature. 2013;502:114–118. doi: 10.1038/nature12265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akyuz N, et al. Transport domain unlocking sets the uptake rate of an aspartate transporter. Nature. 2015;518:68–73. doi: 10.1038/nature14158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erkens GB, Hanelt I, Goudsmits JM, Slotboom DJ, van Oijen AM. Unsynchronised subunit motion in single trimeric sodium-coupled aspartate transporters. Nature. 2013;502:119–123. doi: 10.1038/nature12538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanelt I, Wunnicke D, Bordignon E, Steinhoff HJ, Slotboom DJ. Conformational heterogeneity of the aspartate transporter Glt(Ph) Nature structural & molecular biology. 2013;20:210–214. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mulligan C, et al. The bacterial dicarboxylate transporter VcINDY uses a two-domain elevator-type mechanism. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2016;23:256–263. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wohlert D, Grotzinger MJ, Kuhlbrandt W, Yildiz O. Mechanism of Na(+)-dependent citrate transport from the structure of an asymmetrical CitS dimer. Elife. 2015;4:e09375. doi: 10.7554/eLife.09375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coincon M, et al. Crystal structures reveal the molecular basis of ion translocation in sodium/proton antiporters. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2016;23:248–255. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCoy JG, et al. The Structure of a Sugar Transporter of the Glucose EIIC Superfamily Provides Insight into the Elevator Mechanism of Membrane Transport. Structure. 2016;24:956–964. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanelt I, Jensen S, Wunnicke D, Slotboom DJ. Low Affinity and Slow Na+ Binding Precedes High Affinity Aspartate Binding in the Secondary-active Transporter GltPh. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:15962–15972. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.656876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young JD, Yao SY, Baldwin JM, Cass CE, Baldwin SA. The human concentrative and equilibrative nucleoside transporter families, SLC28 and SLC29. Molecular aspects of medicine. 2013;34:529–547. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King AE, Ackley MA, Cass CE, Young JD, Baldwin SA. Nucleoside transporters: from scavengers to novel therapeutic targets. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:416–425. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.06.004. S0165-6147(06)00152-0 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molina-Arcas M, Casado FJ, Pastor-Anglada M. Nucleoside transporter proteins. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2009;7:426–434. doi: 10.2174/157016109789043892. CVP-Abs-054 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang J, et al. The role of nucleoside transporters in cancer chemotherapy with nucleoside drugs. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:85–110. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Damaraju VL, et al. Nucleoside anticancer drugs: the role of nucleoside transporters in resistance to cancer chemotherapy. Oncogene. 2003;22:7524–7536. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marechal R, et al. Human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 and human concentrative nucleoside transporter 3 predict survival after adjuvant gemcitabine therapy in resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2913–2919. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson ZL, Cheong CG, Lee SY. Crystal structure of a concentrative nucleoside transporter from Vibrio cholerae at 2.4 A. Nature. 2012;483:489–493. doi: 10.1038/nature10882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson ZL, et al. Structural basis of nucleoside and nucleoside drug selectivity by concentrative nucleoside transporters. Elife. 2014;3:e03604. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vergara-Jaque A, Fenollar-Ferrer C, Kaufmann D, Forrest LR. Repeat-swap homology modeling of secondary active transporters: updated protocol and prediction of elevator-type mechanisms. Front Pharmacol. 2015;6:183. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2015.00183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slugoski MD, et al. Conserved glutamate residues Glu-343 and Glu-519 provide mechanistic insights into cation/nucleoside cotransport by human concentrative nucleoside transporter hCNT3. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:17266–17280. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.009613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yao SY, et al. Conserved glutamate residues are critically involved in Na+/nucleoside cotransport by human concentrative nucleoside transporter 1 (hCNT1) J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30607–30617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703285200. M703285200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Duyne GD, Standaert RF, Karplus PA, Schreiber SL, Clardy J. Atomic structures of the human immunophilin FKBP-12 complexes with FK506 and rapamycin. J Mol Biol. 1993;229:105–124. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Battye TG, Kontogiannis L, Johnson O, Powell HR, Leslie AG. iMOSFLM: a new graphical interface for diffraction-image processing with MOSFLM. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67:271–281. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910048675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Otwinowski Z, Minor W, et al. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kabsch W. Xds. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strong M, et al. Toward the structural genomics of complexes: crystal structure of a PE/PPE protein complex from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8060–8065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602606103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen VB, et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Delano WL. The PyMol Molecular Graphics System. DeLano Scientific; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson ZL, Lee SY. Liposome reconstitution and transport assay for recombinant transporters. Methods Enzymol. 2015;556:373–383. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2014.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The sequence of CNTNW can be found in the National Center for Biotechnology Information under accession code WP_009116906. Atomic coordinates and structure factors for the reported crystal structures are deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession codes 5L26 (substrate-bound inward-facing, CNTNW), 5L27 (intermediate-1, CNTNWN149L-1), 5L24 (intermediate-2, CNTNWN149L-2), 5U9W (intermediate-3, CNTNWN149L-3), 5L2A (outward-facing, CNTNWN149S,F366A), and 5L2B (outward-facing, CNTNWN149S,E332A).