Abstract

Objective

To determine whether and how transcription factor Erg participates in the genesis, establishment and maintenance of articular cartilage.

Methods

Floxed Erg mice were mated with Gdf5-Cre mice to create conditional mutants lacking Erg in their joints. Mutant and control joints were subjected to morphological and molecular characterization and also experimental osteoarthritis (OA) surgery. Gene expression, promoter reporter assays and gain- and loss-of-function in vitro tests were used to characterize molecular mechanisms of Erg action.

Results

Conditional Erg ablation did not elicit obvious changes in limb joint development and overall phenotype in juvenile mice. Over aging, however, mutant joints became spontaneously deranged and exhibited clear OA-like phenotypic defects. Mutant joints in juvenile mice were more sensitive to surgically induced OA and became defective sooner than operated control joints. Global gene expression data and other studies identified PTHrP and lubricin as possible downstream effectors and mediators of Erg action in articular chondrocytes. Reporter assays using control and mutated promoter/enhancer constructs did indicate that Erg acted on ets DNA binding sites to stimulate PTHrP expression. ERG was up-regulated in severely affected areas in human OA articular cartilage, but remained barely appreciable in less affected cartilage areas.

Conclusion

The study shows for the first time that Erg is a critical molecular regulator of articular cartilage’s endurance over postnatal life and ability to mitigate spontaneous and experimental OA. Erg appears to do so through its regulation of PTHrP and lubricin expression, factors known for their protective roles in joints.

Keywords: Limb synovial joints, articular cartilage, transcription factor Erg, osteoarthritis

Introduction

Articular cartilage is a permanent, avascular and stable tissue that permits joint and body motion through life (1). Its properties and phenotype are distinct from those of growth plate cartilage in which the chondrocytes undergo maturation and hypertrophy, sustain skeletal growth and then disappear by the end of puberty (2, 3). The mechanisms dictating the distinct phenotype of articular and growth plate chondrocytes remain largely unknown, particularly at the molecular level (2). The superficial zone of articular cartilage contains cells oriented along the main direction of movement that sustain frictionless joint movement by means of lubricin/Prg4, hyaluronate and other anti-adhesive molecules (4). Articular chondrocytes in the middle and deep zones produce instead the main components of cartilage extracellular matrix -including aggrecan and collagen II- that provide biomechanical resilience. Unfortunately and too often, articular chondrocytes can lose phenotypic stability and biomechanical vitality during aging. These problems are escalated during osteoarthritis (OA) during which many articular chondrocytes actually switch to a growth plate-like hypertrophic phenotype, paving the way toward joint demise (5, 6). Current therapies for OA are limited and often palliative, and thus there is an urgent need for progress.

Erg belongs to the ETS family of transcription factors, one of the largest in mammals. Erg regulates critical biological processes and is often dysregulated in malignancies including prostate cancer (7), leukemia (8) and Ewing’s sarcoma (9). As other ETS members, Erg regulates target gene expression by interactions to a core sequence motif 5’-GGA(A/T)-3’ via its highly conserved 85-amino acid ets DNA-binding domain. Erg and other ETS members contain the Pointed (PNT) domain and interact with other regulatory factors -including ets members and epigenetic modifiers- to regulate diverse functions in different tissues (10, 11).

Erg was originally shown to be expressed in developing synovial joints, but its roles remained unclear (12). We found that Erg expression was first detectable in embryonic joint progenitor cells and became strong in developing articular chondrocytes, particularly in superficial cells (13, 14). To test biological activity, we over-expressed Erg throughout the developing mouse skeleton via cartilage-specific Col2a1 promoter-enhancer sequences. Whereas control long bones displayed typical articular chondrocytes and growth plate chondrocytes undergoing hypertrophy, the chondrocytes throughout the developing skeleton in transgenic mice were small in size and phenotypically stable, were not organized in growth plates and expressed the articular cartilage marker tenascin-C. Thus, Erg over-expression had imposed an articular-like phenotype on all chondrocytes regardless of origin and location, thus representing the first identified joint development-associated transcription factor seemingly able to stabilize the chondrocyte phenotype and prevent hypertrophy. The present study was conducted to further test these key conclusions and examine their implications. We created a novel line of floxed Erg mice (Erg flox/flox) and mated them with Gdf5-Cre mice (15), thus leading to Erg deficiency in prenatal and postnatal joints. We find that developmental loss of Erg is not compatible with articular cartilage’s endurance over age and renders the joints vulnerable to acute surgical OA challenge, establishing Erg as an essential factor for joint function and longevity as well as an attractive target for joint therapies.

Materials and Methods

Floxed Erg mice

Construction of targeting vector, ES cell selection and subsequent procedures to obtain floxed Erg (Erg flox/flox) mice were carried out in cooperation with University of Cincinnati Mouse Core Facility. Schematic structures of targeting vector, mice used to generate various alleles and primers for genotyping are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

OA mouse model

Two month-old Ergf/f;Gdf-5-Cre mice and control littermates were subjected to experimental medial joint instability-induced OA model that leads to a predictable outcome over time (16). Under anesthesia and using IACUC-approved protocols, we transected medial collateral ligaments and microsurgically removed the medial meniscus of right knee to increase joint instability. Left knees were sham-operated and served as internal controls. Mice were monitored over time, and their knees were collected 4 weeks after surgery.

OA progression and severity assessment

Serial 5 µm sagittal sections of whole knee joints were stained with Safranin-O/Fast green or H&E and graded at 70 µm intervals through the joint by three scorers blind to specimen identity. Degrees of arthritic change of femur and tibia were evaluated by OARSI grading systems (17). At least four sections per sample were analyzed and scored.

Immunohistochemical analysis

Mouse cartilage sections treated with pepsin for antigen retrieval were incubated with rabbit Erg antibodies (Santa Cruz, sc-353, 1:100 dilution), Fli1 antibodies (Santa Cruz sc-22808, 1:100), type X collagen, or MMP13 antibodies (Cosmo Bio Co., LTD., 1:1000), or aggrecan neoepitope VDIPEN (kindly provided by Dr. J. Mort, J. S., Shriners Hospital, 1:1000) processed with Polymer detection Kit (Invitrogen), and counterstained with methyl green. For immunofluorescence, we used VDIPEN antibodies and a goat-anti-rabbit Alexa 594-labeled secondary antibody (Invitrogen, A11012, 1:500). Rabbit anti-lubricin/PRG4 (abcam, ab28484, 1:250) was detected with Biotin-SP-conjugated Affinipure goat anti-rabbit IgGs (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 1:500) and DyLight 549-conjugated Streptavidin (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 1:500). CA, USA).

Cells and cell culture

Primary rabbit articular chondrocytes were isolated from femoral knee joint surface of 3–4 week old New Zealand White rabbits as described (18). Primary mouse epiphyseal chondrocytes, a mixture of articular and growth-plate chondrocytes, were isolated from newborn mice (19). Freshly isolated chondrocytes were subjected to gene expression analysis and reporter assays within 6 hours after isolation. Human prostate cancer cell line DU145 and mouse chondrogenic cell line ATDC5 were obtained from ATCC. AD293 was obtained from TaKaRa Bio, Japan. Cells were maintained in 10% FBS (maintenance) or 1% FBS (transfection) high-glucose DMEM. Lipofectamine LTX with Plus reagents (Invitrogen) was used in all transfection experiments. For PTHrP reporter assays, we co-transfected pGL3 control vectors (0.1% of the amount of pGL4.72 PTHrP reporter vector) to normalize transfection efficiency.

PCR analysis

Total RNA purified by RNA easy mini kit (Qiagen) was reverse transcribed with RT2-First Strand cDNA kit (Qiagen). Conventional PCR was carried out with HS-PrimeStar premix (TakaRa) and primers indicated in figure legends. Regulation of PTHrP and Prg4 by Erg or Fli-1 was analyzed by qPCR with Zen primers (IDTDNA). Product numbers of qPCR primers used were Mm.PT.49a.6430177 (mouse Erg), Mm.PT.49a.11643008 (mouse Fli-1), Mm.PT.49a.11141768 (mouse PTHrP), and Mm.PT.49a.6284011(mouse PRG4/lubricin).

Vector constructions

Recombinant adenovirus encoding mouse Erg was made with AdEasy XL Adenoviral Vector System (Stratagene). Full coding sequence of mouse Erg NM_133659 was PCR amplified, subcloned into pShuttle vector and verified by sequencing. The resulting Shuttle vector was linearized by Pme I and combined with pAdEasy vector by homologous recombination (pAd-Erg). We then removed the plasmid backbone of pAd-Erg by Pac I digestion and transfected into AD293 virus producing cells. GFP encoding adenovirus was also generated as control.

Plasmid expression vectors encoding Erg (pSG5-Erg), Fli-1 (pSG5-Fli-1) or dominant negative deletion mutant of Erg (pSG-5-Erg(del Ets)) were created by subcloning PCR amplified fragments (Erg; 152–1612 of NM_133659, Fli-1; 161–1519 of NM_008026, Erg(del Ets); 161–1083 of NM_133659 plus termination codon) into pSG5 vector (Stratagene). Control and gene specific siRNAs used were On-Target Smart Pool siRNA for Erg (L-040714-01), Fli-1 (L-045414-01), and On-Target Control Pool (D-001810-10-05)(Thermo Scientific Dharmacon).

To construct mouse PTHrP reporter vectors, we first PCR amplified 4 highly conserved segments by using PTHrP genomic Bac clones as templates. Resulting DNA fragments were amplified again to add appropriate restriction sites and subcloned into pGL4.72 vector (Promega). Oligos used to amplify conserved segments are: 5’-CATTCCCAATGCTATCCCAAAAGTCCCC-3’ and 5’-CCTCAACATATTCTCAAGCCCAAGTAC-3’ for segment 1, 5’-AACACCAGCAAAATATCGCCGCAGTGTT-3’and 5’-ACAGCAGCCATGGAAAGTTCTTTGCCCA-3’ for segment 2, 5’-TATCAGAAGAAGGTGAGAAAGAAGGACT-3’ and 5’-CATCGTGCCGCTCGCTGGCTCTGGGGA-3’ for segment 3, and 5’-GGACTGGCAGAGGCAGACCTTCAGAAC-3’ and 5’-GACTGGCAGAGGCAGACCTTCAGAAC-3’for segment 4. To introduce mutation in 2 conserved Ets binding sites (EBSs) in the proximal promoter, we simultaneously introduced mutation with Quick Change Site directed mutagenesis system (Stratagene). This changes EBS I and II in Fig.4 from TTTCCGGAAGC to TaaCCGGttGC. Oligos used in the experiment were: 5’-PTTGCAACCAGCCCACCGAAGGAGG-3’and 5’-PCCGGAAAGTTGATTCCACAACGCCCTT-3’ (to mutate EBS I), 5’-PCCGGTTGCAACCAGCCCACCG-3’ and 5’-PTTAGTTGATTCCACAACGCCCTTGAACGG-3’ (to mutate EBS II).

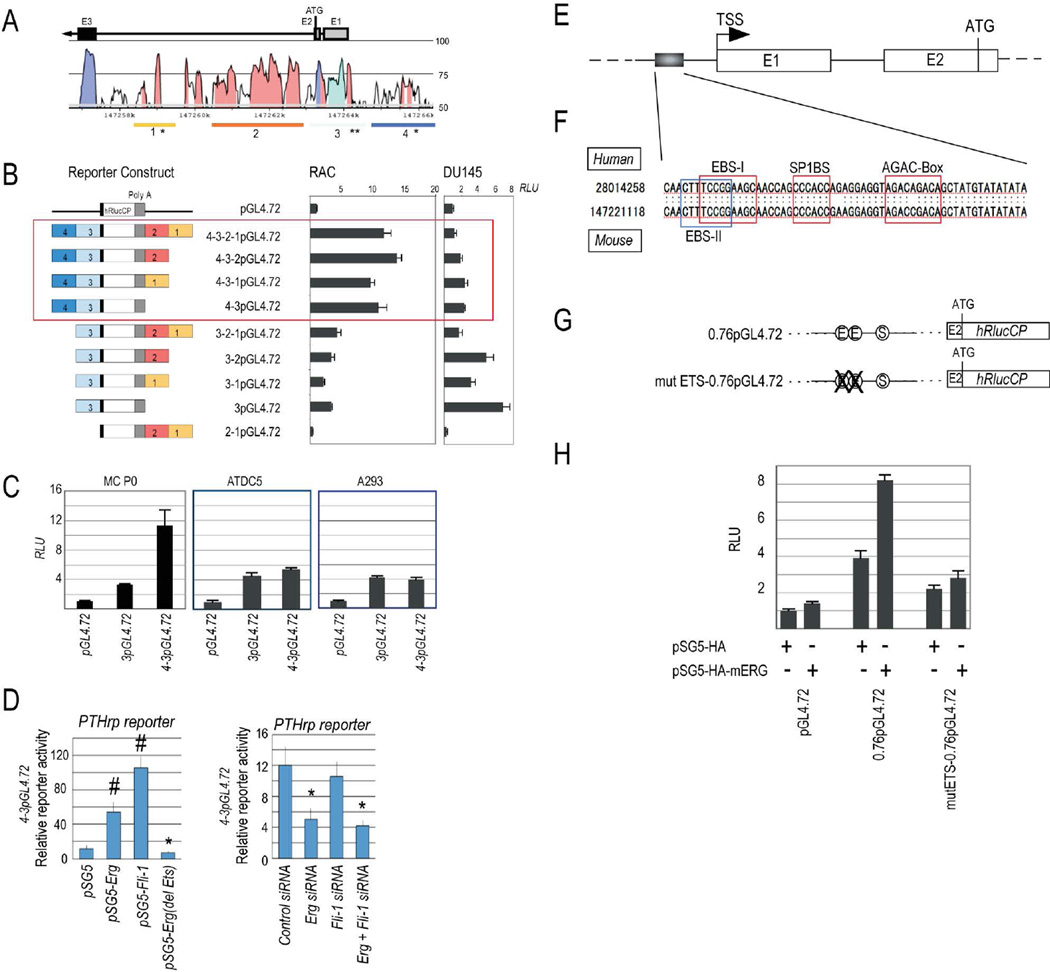

Figure 4.

Erg regulates PTHrP enhancer activities. (A) Sequence conservation degrees in exons 1, 2 and 3 in mouse PTHrP gene, Lines 1, 2, 3 and 4 represent segments cloned and tested for enhancer activity. *, the location of putative ets binding sites. (B) pGL4.72 luciferase reporter constructs containing segments 1, 2, 3 and/or 4 (left) and reporter activity with each construct in primary rabbit articular chondrocytes (RAC) and DU145 cells. (C) PTHrP reporter assays with segment 3 containing reporter 3pGL4.72 or empty vector pGL4.72 in primary mouse chondrocytes (MC PO), ADTC5 cells and A293 cells. (D) PTHrP reporter assays with Erg, Erg mutant or Fli-1 expression vector or Erg and/or Fli1siRNA. (E) Transcription start site (TSS) and portion of upstream segment 3 used for ets site functional analysis (box) of mouse PTHrP. (F) Conserved ets binding sites (EBS-I and EBS-II) and conserved SP1BS site and AGAC-box in human and mouse. (G and H) Scheme of reporter constructs containing wild type portion or mutant portion in which the 2 ets sites were mutated (G). PTHrP reporter assay with each construct and a mouse Erg over-expressing plasmid or empty vector in mouse chondrogenic cells (H).

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was assessed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or unpaired Student’s t-test (Prism 5, GraphPad Software Inc.).

Results

Creation of a novel floxed Erg mouse line

Before embarking into creation of Erg flox/flox mice, we considered that Erg is alternatively spliced (20) and contains two alternative translation start sites in exon 3 and exon 4 (21). Exon 3-ablated mice were found to be viable and broadly normal, whereas exon 4-ablated mice were embryonic lethal and most died by E11.5 (21). To avoid possible complications due to alternative translation products, we created a new transgenic line in which the loxP sites flanked the universal exon 6 and would elicit a precocious stop codon in exon 7 following Cre-mediated deletion (Supplementary Fig. 1). To verify effectiveness of that design, we mated the Erg flox/flox mice with β-actin Cre to globally ablate Erg throughout the developing embryo. Indeed, while the resulting heterozygous Erg+/− embryos were viable and present at expected Mendelian ratios (Supplementary Table 1), homozygous Erg−/− embryos did not develop past E11.5 and displayed severe, and likely fatal, defects in definitive hematopoiesis in yolk sac (Supplementary Fig. 2).

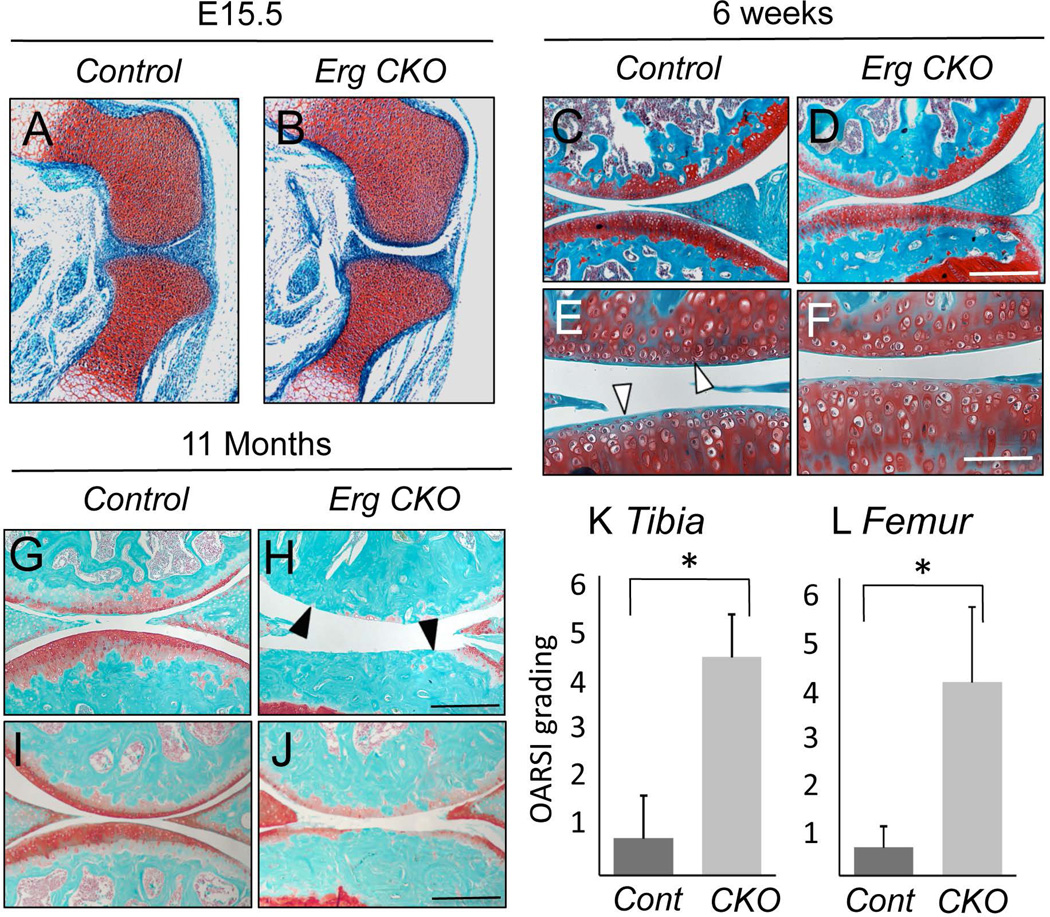

Consequences of Erg ablation on joints

To uncover Erg roles in the joints, we mated the Erg flox/flox mice with Gdf5-Cre mice (15, 22) and examined the resulting Erg flox/flox;Gdf5-Cre (Erg CKO) mutants and control Erg flox/flox littermates at successive prenatal and postnatal time points. Surprisingly, limb joint formation was not overtly affected in mutant embryos (Fig. 1 A and B). Both control and mutant joints shared a similar and typical organization that included well-formed epiphyses, a thick capsule and incipient synovial space (Fig. 1 A and B). To determine whether mutant joints might become defective with age, we sacrificed mice at different postnatal times. By 6 weeks of age, control knees displayed their expected mature and functional organization, with a thick Safranin O-positive articular cartilage (Fig. 1 C and E, arrowheads) and an underlying secondary ossification center (Fig. 1C). Even at this age, we detected no obvious differences in companion mutants (Fig. 1 D and F). In contrast, mutant joints in mice older than 6 to 7 months did exhibit degenerative OA-like defects compared to those in age-matched controls. Mutant knee articular cartilage was exceedingly thin, eroded and nearly absent (Fig. 1 H and J, arrowheads), while cartilage in companion controls still displayed a largely normal structure and organization despite the advanced age (Fig. 1 G and I). Differences between control and mutant cartilage in tibia and femur were statistically significant based on OA assessment criteria (17) (Fig. 1 K and L). To characterize the OA-like changes in aged mice, Erg CKO and control knee joint sections were stained with antibodies against typical OA markers (Supplementary Fig. 3). Type X collagen staining was observed in both Erg CKO and control articular cartilage. However, clear MMP13 expression was detected over the entire articular cartilage in Erg CKO mice, while it was only found in the calcified zone in control articular cartilage. In addition, Erg CKO articular cartilage exhibited strong staining with VDIPEN antibodies that recognize products of MMP-induced cleaved aggrecan molecules.

Figure 1.

Conditional Erg ablation causes articular cartilage degeneration over natural aging. (A,B) Longitudinal knee sections from E15.5 control Erg flox/flox (A) and conditional Erg flox/flox;Gdf5-Cre (Erg CKO) embryos (B) were stained with Safranin-O and fast green. No obvious differences in tissue structure and organization are present (C–F). Longitudinal knee sections from 6 week-old control (C and E) and Erg CKO (D and F) mice processed as above. Control and mutant joints exhibit similar features, including a thick articular cartilage (arrowheads) and an underlying secondary ossification center (C and D). Longitudinal knee sections from 11 month-old control (G and I) and Erg CKO (H and J) mice processed as above. There is obvious cartilage degeneration in mutants, with some specimens displaying complete loss of articular cartilage (H, solid arrowhead) and others displaying thin and uneven articular surface (J). Articular cartilage in controls appears still healthy and well organized (white arrowhead) (G and I). Arthritic changes of tibial plateau (K) and knee joint surface of femur (L) were evaluated by OARSI grading systems. Graphs show averages and standard deviation of 10 control and 7 Erg CKO mice. * P<0.001. Scale bars, 200 µm (C,D,G–J); 100 µm (E and F).

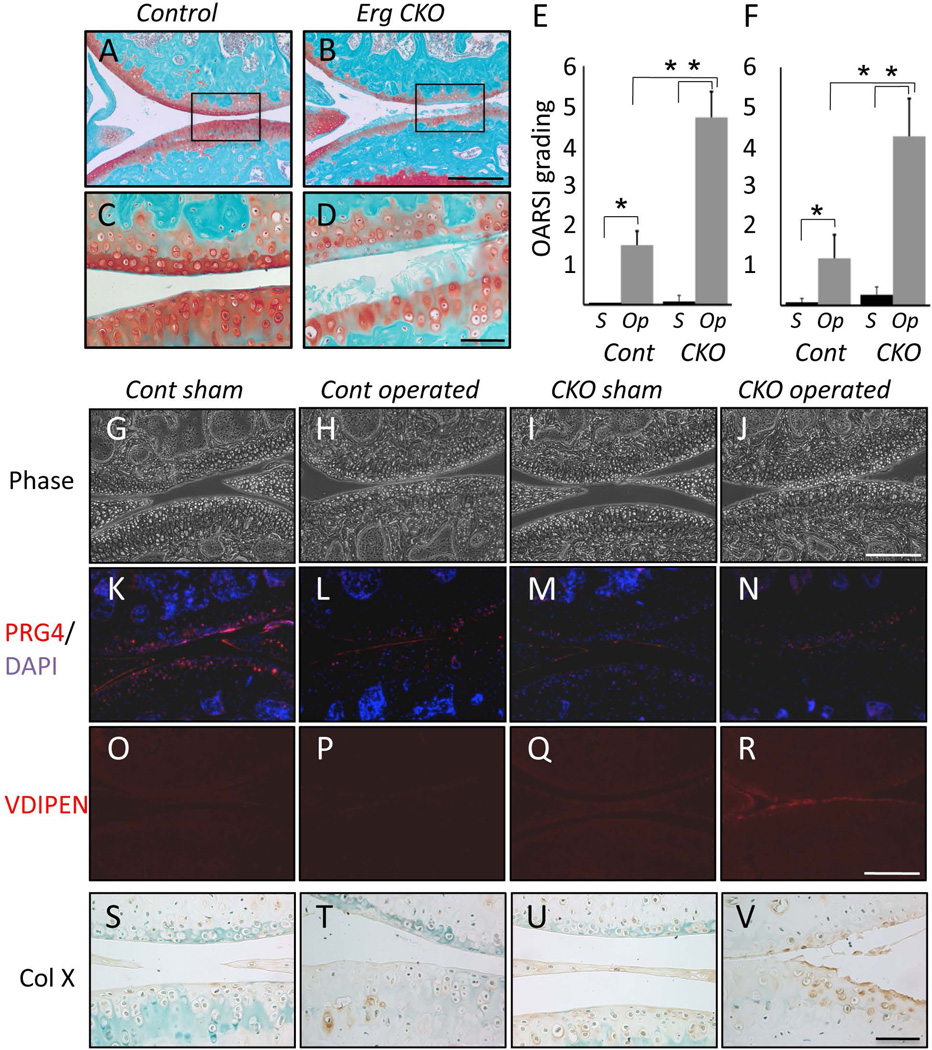

Mutant joints are overly-sensitive to surgical OA challenge

The data suggested that unlike control joints, mutant joints were unable to endure in older animals. This raised the possibility that while joints in younger mutant animals appeared structurally normal, they might actually have some intrinsic phenotypic deficiencies such as poor response to traumatic challenge. To test this thesis, we subjected 8 week-old mutant and control mice to experimental joint instability-induced OA by dissecting the medial collateral ligament and resecting the medial meniscus in right knees. Left joints were sham operated and served as controls. This surgery OA model is widely used in mice and consistently produces OA-like changes starting around 6 weeks after surgery (16). We sacrificed the mice 4 weeks from surgery to determine whether the mutant joints would respond precociously and more negatively to such surgical challenge. In control operated knees, articular cartilage was still largely normal and stained strongly with Safranin O (Fig. 2 A and C) and its superficial zone contained lubricin/Prg4 (Fig. 2L), a key anti-adhesive and lubrication macromolecule that when mutated, causes human joint pathologies (23). In contrast, articular cartilage in operated mutants was already significantly eroded by 4 weeks, was largely devoid of Safranin-O staining proteoglycans (Fig. 2 B and D) and lubricin (Fig. 2N) and already displayed typical patho-phenotypic traits of OA, including VDIPEN (Fig. 2R) and ectopic chondrocyte hypertrophy depicted by collagen X staining (Fig. 2V)(24, 25). Neither of the latter traits was appreciable in operated controls (Fig. 2 P and T). Sham-operated control (Fig. 2 G, K, O and S) and mutant joints (Fig. 2 I, M, Q and U) displayed minor structural differences, with one notable exception being lower lubricin staining in mutants (Fig. 2M). Histomorphometric assessment of articular cartilage using the OARSI grading system (17) revealed that: severity of osteoarthritic changes was significantly higher in operated than sham-operated joints (P<0.0001, 2-way ANOVA); Erg CKO developed significantly severer OA than controls (P<0.0001, 2-way ANOVA); and OA susceptibility upon surgery was significantly higher in Erg CKO (P<0.0001,2-way ANOVA)(Fig. 2 E and F).

Figure 2.

Conditional Erg mutant mice exhibit precocious joint degeneration following OA-inducing surgery. (A–D) Two month-old control and Erg CKO mice were subjected to OA-inducing surgery in their right knee and sacrificed after 4 weeks. Safranin-O/fast green histochemical staining of longitudinal knee sections shows that articular cartilage was markedly deteriorated in operated mutants (B,D), but was largely unaffected in operated controls (A,C). Boxed area in (A–B) is shown at higher mag in (C–D). (E,F) Histological grading by OARSI system confirms that joint degeneration and defects were extensive in Erg CKO joints compared to controls (E; tibial plateau, F; femur). (G–V) Phase microscopy (G-J) and immunohistochemical analyses (K-V) reveal that operated mutant joints exhibit low Prg4 content (N) and conspicuous presence of such OA phenotypic traits as aggrecan degradation neo-epitope VDIPEN (R) and hypertrophic marker collagen X (V). These traits were not observed in control operated joints (P,T) that displayed detectable –albeit reduced- Prg4 levels (L). Sham-operated control (G,K,O,S) and mutant (I,M,Q,U) joints were essentially unchanged with the exception of Prg4 that was reduced after surgery (M). Scale bars, 250 µm (A,C); 100 µm (B,D); 200 µm (G–N).

Mechanisms of Erg action

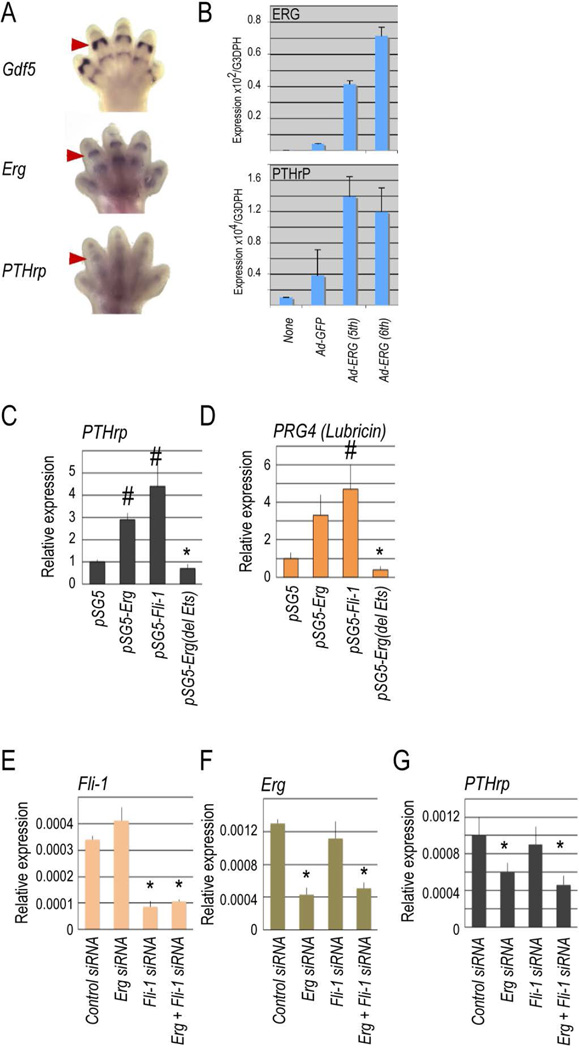

The above data raised the question of why Erg deficiency rendered the joints more susceptible to surgical challenge and how Erg normally acts to stabilize the articular chondrocyte phenotype. We considered a possible link to parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) for several reasons. PTHrP is expressed in developing articular cartilage and is a potent inhibitor of chondrocyte maturation and hypertrophy (26). Indeed, whole mount in situ hybridization showed that PTHrP was co-expressed along with Erg and Gdf5 in developing joints (Fig. 3A). In addition, mouse reference tissue expression databases (NCBI, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/ GDSbrowser?acc=GDS868) created from large scale transcriptome analyses showed that PTHrP and Erg as well as Gdf5 are co-expressed in adult mouse xiphoid cartilage, the only permanent cartilage included in those analyses (Supplementary Fig. 4). Thus, we asked whether Erg regulates PTHrP expression. Adeno- or plasmid-driven over-expression of Erg in freshly isolated mouse chondrocytes did cause about 3-fold increase in PTHrP expression (Fig. 3 B and C) and, interestingly, lubricin (Prg4) expression as well (Fig. 3D). Over-expression of subfamily member Fli-1 elicited very similar increases (Fig. 3 C and D). On the other hand, over-expression of a mutant Erg lacking the ets DNA-binding domain –referred to as Erg(del Ets)- inhibited baseline PTHrP and lubricin expression (Fig. 3 C and D). We carried out additional loss-of-function studies using Erg and Fli-1 siRNA that effectively and specifically reduced target gene expression (Fig. 3 E and F). While Erg down-regulation elicited a decrease in PTHrP expression, Fli-1 down-regulation did not (Fig. 3G), indicating that Erg had preponderant biological relevance.

Figure 3.

Erg and Fli-1 stimulate PTHrP and Prg4 expression. (A) Whole mount in situ hybridization shows that Erg and PTHrP were co-expressed in E13.5 mouse embryo digit joints along with Gdf-5 (arrowheads). (C–D) Adeno- or plasmid-driven over-expression of Erg (B, top panel) stimulated PTHrP expression (B, bottom panel; c) and Prg4/lubricin expression (D) in chondrogenic cell cultures. Fli-1 over-expression elicited a similar up-regulation of PTHrP and Prg4 (c–d), whereas over-expression of the dominant negative Erg (Erg (del Ets) which lacks ets DNA binding domain) reduced baseline expression (C–D). (E–G) Reciprocal siRNA experiments show that: (E) endogenous Fli-1 expression was reduced by treatment with Fli-1 or Fli-1 plus Erg siRNA, but not Erg siRNA; (F) endogenous Erg expression was reduced by treatment with Erg or Erg plus Fli-1 siRNA, but not Fli-1 siRNA; and (G) treatment with Erg siRNA inhibited PTHrP expression, but treatment with Fli-1 siRNA did not. Statistically significant differences observed in control versus treated samples (p < 0.05) are indicated by the symbols # and * above the appropriate histograms. All transfection-based gain and loss of function experiments were repeated at least three times independently.

Erg regulates PTHrP expression

Next, we investigated how Erg regulates PTHrP expression. Using UCSC genome browser, we selected four highly conserved segments spanning the upstream promoter region (identified as segment 1, 2, 3 and 4 in Fig. 4A), amplified the region by PCR, and constructed a series of reporter plasmids (Fig. 4B). Each construct was transfected into primary rabbit articular chondrocytes (RAC) -that can be prepared more readily than mouse chondrocytes- and a non-chondrogenic human cancer cell line (DU145) for comparison. Constructs including segment 3 elicited reporter activity in both cell types (Fig. 4B), but presence of segment 4 markedly increased reporter activity in chondrocytes only (Fig. 4B, boxed histograms). To verify the apparent enhancer activity of segment 4 in chondrocytes, we transfected reporter constructs containing segments 4 and 3 (4-3pGL4.72), segment 3 (3pGL4.72) or empty vector (pGL4.72) into primary epiphyseal mouse chondrocytes (MC P0), mouse chondrogenic ADTC5 cells, and non-chondrogenic A293 cells. While the segment 3-containing construct continued to elicit reporter activity in every cell type, the construct containing segments 3 and 4 elicited strong reporter activity in chondrocytes only (Fig. 4C). Activity of segment 3–4 containing reporter construct was significantly enhanced by plasmid-driven Erg- or Fli-1 over-expression (Fig. 4D), but was reduced by Erg(del Ets) over-expression or Erg siRNA treatment (Fig. 4D).

Studies in human and mouse cancer cells showed that segment 3 contain two ets binding sites needed for responsiveness to Ets-1 and Ets-2 (27, 28). Given the proven Ets responsiveness of those sites, we asked whether they would respond to Erg as well. We constructed luc reporter plasmids in which the two ets sites were mutated (mutETS0.76GL4.72) or left unchanged (ETS0.76GL4.72) (Fig. 4 E–G). Each plasmid was transfected into chondrogenic cells along with a mouse Erg-overexpression plasmid vector or empty vector. Indeed, Erg over-expression increased control ETS0.76GL4.72 reporter activity markedly, but left mutETS0.76GL4.72 reporter activity largely unchanged (Fig. 4H).

Endogenous ERG expression is up-regulated in human OA cartilage

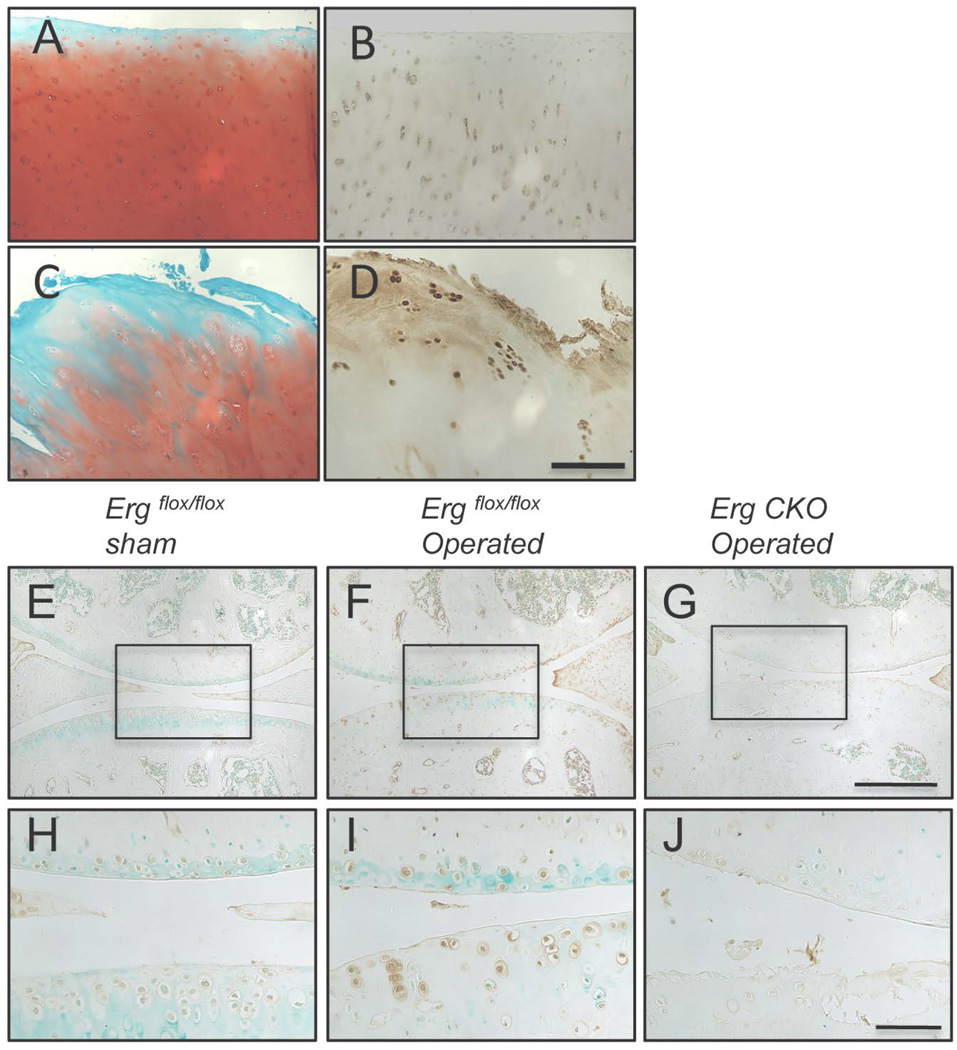

Given the beneficial Erg roles and modes of action revealed by the above mouse studies, we predicted that endogenous ERG expression would increase in human OA cartilage as a possible attempt to stabilize/repair the cell phenotype. Thus, we obtained surgical specimens from consented patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty and processed continuous histological sections for Safranin-O histochemical staining or immunohistochemistry with ERG antibodies. Sections from non-weight bearing and relatively normal portions of articular cartilage displayed strong Safranin-O staining (Fig. 5A) and faint ERG staining (Fig. 5B). In contrast, there was strong ERG immunostaining in the fibrillated and overtly damaged portions of the tissue (Fig. 5D) that was accompanied by faint Safranin-O staining (Fig. 5C). Patterns were consistent from specimen to specimen. To further verify the data, we asked whether a similar Erg up-regulation would characterize mouse joints subjected to OA surgery. Indeed, endogenous Erg was quite evident in tibial and femoral articular chondrocytes in operated mice at 4 weeks from surgery (Fig. 5 F and I), but was at background levels in sham-operated companions (Fig. 5 E and H). As expected, no staining was visible in operated Erg CKO companions attesting to staining specificity (Fig. 5 G and J).

Figure 5.

Up-regulation of ERG in human and mouse OA cartilage. (A–D) Surgical specimens of total knee arthroplasty from consented patients processed for histology. Sections were stained with Safranin-O and methyl green (A,C) or used for immunohistochemical detection of ERG (B,D). ERG was hardly detectable in relatively normal non-weight bearing portions of articular cartilage (B), while strong immuno-reactivity was observed in neighboring damaged and fibrillated articular cartilage areas within the same surgical specimen (D). (E–J) Immunohistochemical detection of Erg in mouse knee joints. Knee joints of 2 month old control (Erg flox/flox) or Erg CKO mice were either sham operated or subjected to medial instability OA surgery. Knee joints were collected 4 weeks after operation, sectioned and stained with Erg antibodies. H–I are higher magnification images of regions indicated in E–F. Erg was barely detectable in sham-operated control (Erg flox/flox) mice (E,H) but was markedly upregulated in the operated joints (F,I). As expected, operated joints in Erg CKO mice exhibited no staining (G–J). Scale bars, 200 µm (A–D); 250 µm (E–G); 100 µm (H–J).

Discussion

Articular cartilage has attracted much research attention for decades owing to its critical importance in skeletal movement and functioning. Those efforts have shed light on the tissue’s morphological and physiological intricacies, the multifunctionality of its numerous matrix components, and its durability and plasticity to mechanical stimulation and deformations during daily routine physical activities (1). What has remained elusive, however, is how the tissue acquires such enduring and unique abilities and why it fails to counter challenges imposed on it by injury, mechanical over-stimulation or chronic disease. Our data here represent a significant and novel step ahead in clarifying such important conundrums. We show that Erg endows limb joint articular cartilage with endurance and structural stability over postnatal life and also enables it to respond to, and delay the deleterious effects of, acute surgical trauma in young adult animals. The latter is particularly striking since morphologically, the young Erg mutant joints appear normal and identical to those in companion control mice prior to surgical trauma. It is thus likely that Erg action is needed early in life to establish the basic but critical characteristics of articular chondrocytes, traits that would serve them well in response to injury as well as over life.

Actions exerted by Erg could include its ability to regulate PTHrP and lubricin expression in chondrocytes. Lubricin is essential for long term joint function (23), and PTH/PTHrP signaling has long been known to stabilize the chondrocyte phenotype, stimulate proteoglycan synthesis and prevent hypertrophy and matrix catabolism (29, 30). Indeed, deficiency in PTHrP or lubricin provokes OA-like changes (23, 31), and treatment with exogenous PTH(1–34) or lubricin reduces them (32, 33). Erg might regulate chondrocyte function through induction of an epigenetic regulator Ezh2. Ezh2 is a catalytic subunit of polycomb repressor complex 2 and prevents differentiation of variety of cell types (34). Interestingly, Ezh2 is a direct target of Erg (36) and highly expressed in developing limb joints (Eurexpress Database http://www.eurexpress.org/ee/: Assay number 008612)(35). We also observed that the Erg CKO mice displayed synovial changes, including synovium hyperplasia and increased vascularity in relation to level of destruction of articular cartilage (data not shown). Since the mouse system used in this study induces ablation of Erg from synovium as well as articular cartilage, Erg may have additional roles in control of inflammation and angiogenesis in synovium.

When subjected to experimental joint destabilization surgery, wild type mice do eventually develop OA. We show here that progression of such OA-like defects is accompanied by a significant up-regulation of endogenous Erg expression, and we observe the same up-regulation in the damaged and fibrillated regions of human articular cartilage from OA patients. PTHrP and PTHR1 expression was previously shown to increase in experimental arthritis as well (32, 36). Given the apparent protective roles of Erg as well as PTHrP, why did such up-regulations fail to protect cartilage? We cannot fully answer this question at the moment, but can consider possibilities. Our human OA data show that ERG up-regulation was topographically restricted and limited to affected cartilage regions but remained at barely detectable levels in surrounding unaffected regions, suggesting that ERG is a locally-regulated and cell-autonomous gene. Given that OA is an organ disease affecting every tissue in the joint (37), it may be that a regional up-regulation of ERG may not be sufficient to counteract overall joint changes and multiple disease pathways. Thus, the up-regulation of both Erg and/or PTHrP during natural or experimental OA may occur too late or be suboptimal. If we could induce Erg expression broadly in the joint, it could in the future be used as an effective tool for joint therapy. Enhancing Erg expression could turn out to be more effective than targeting specific joint pathogenic genes such as Adamts5 or Mmp13 that once suppressed, elicit an amelioration of certain joint OA defects such as matrix degradation, but not other concurrent problems including ectopic chondrocyte hypertrophy (38, 39).

As pointed out above, Erg is part of an ets subfamily that includes Fli-1 (Supplementary Table 2). Erg and Fli-1 share over 65% amino acid homology, are co-expressed in some tissues and can interact with each other (40, 41). Ablation of Fli-1 or Erg is embryonic lethal by E11.5, but the Fli-1-null embryos die because of defective angiogenesis while the Erg-null embryos die due to failure of definitive hematopoiesis (42, 43)(see Supplementary Fig. 2). Erg and Fli-1 are co-expressed in bone marrow and are both required for hematopoietic stem cell maintenance and megakaryocyte differentiation likely by co-regulating common target genes (44). Interestingly, whole mount in situ hybridization data from the Eurexpress Consortium show that Fli-1 is actually co-expressed with Erg in developing mouse limb joints, albeit at lower levels, and we have confirmed those findings (Supplementary Fig. 5, 6 and 7, and Table 2)(35). In addition, Fli-1 expression was markedly higher in severely degenerated regions of human OA specimens (Supplementary Fig. 6). Fli-1 could thus have compensated for Erg in joint formation and growth in Erg-deficient embryos and young adults, though it may have not been able to establish and maintain chondrocyte phenotype over the long term. Our in vitro study showed that similar to Erg, plasmid-driven over-expression of Fli-1 stimulates Prg4 and PTHrP expression, but down-regulation of endogenous Fli-1 by siRNA has little effect on PTHrP expression while Erg down-regulation does. It appears that Fli-1 and Erg may normally have diverse potencies in chondrocytes possibly reflecting their respective and distinct expression levels and/or diverse targets. Once experimentally up-regulated above endogenous levels, however, both factors would elicit similar and encompassing effects on the chondrocyte phenotype, making both factors as attractive therapeutics.

Table 2.

Expression of ets transcription factor family members in developing limb skeleton.

| Gene Symbol | Entrez Gene ID | Euroexpress Assay ID |

In situ hybridization signal around limb skeleton at E14.5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| ELF subfamily | |||

| ELF1 | 13709 | 019460 | no regional signal |

| ELF2 (NERF) | 69257 | 019461 | weak and ubiquitous signal |

| ELF4 (MEF) | 56501 | 019462 | around cartilage primodia |

| ERG subfamily | |||

| ERG | 13876 | 019466 | joint specific signal |

| FLI1 | 14247 | 019453 | joint specific signal |

| FEV | 260298 | 019661 | no regional signal |

| ELG subfamily | |||

| GABPa | 14390 | 005429 | no regional signal |

| ERF subfamily | |||

| ERF (PE2) | 13875 | 019452 | ubiquitous signal, low in cartilage |

| ETV3 (PE1) | 27049 | 007938 | no regional signal |

| ESE subfamily | |||

| ELF3 (ESE1/ESX) | 13710 | 008831 | signal in cartilage primodia, lower signal in hypertrophic zone |

| ELF5 (ESE2) | 13711 | 004671 | ubiquitous signal, low in cartilage |

| ESE3 (EHF) | 13661 | 011934 | no regional signal |

| ETS subfamily | |||

| ETS1 | 23871 | 011289 | vasculature |

| ETS2 | 23872 | 011879 | joint and cartilage |

| PDEF subfamily | |||

| SPDEF (PDEF/PSE) | 30051 | 011402 | not available |

| PEA3 subfamily | |||

| ETV4 (PEA3/E1AF) | 18612 | 016708 | not available |

| ETV5 (ERM) | 104156 | 000518 | around cartilage primodia |

| ETV1 (ER81) | 14009 | 017317 | around cartilage primodia |

| ER71 subfamily | |||

| ETV2 (ER71) | 14008 | 006056 | not available |

| SPI subfamily | |||

| SPI1 (PU.1) | 20375 | 011887 | signal in cartilage |

| SPIB | 272382 010913 | 010913 | no regional signal |

| SPIC | 20728 | 010421 | no regional signal |

| TCF subfamily | |||

| ELK1 | 13712 | 006574 | no regional signal |

| ELK4 (SAP1) | 13714 | 008987 | no regional signal |

| ELK3 (NET/SAP2) | 13713 | 019463 | cartilage and vasculature |

| TEL subfamily | |||

| ETV6 (TEL) | 14011 | 012303 | no regional signal |

| ETV7 (TEL2) | not available in mouse | ||

PTHrP is encoded by a single gene. Studies have found that transcription can start from three alternative sites that are 5’ of exon 1 and 4 (termed P1 and P3, respectively) and 5’ of exon 3 (P2) (45–47). P3-initiated transcription is usually observed in many tissues, while transcription from P1 and P2 is more restricted. Alternative splicing at 5’ and 3’ termini generates multiple transcripts that produce three main isoforms of mature PTHrP. As pointed out above, PTHrP is widely recognized as critical for skeletal development and growth, including articular cartilage where its notable function is to stabilize the chondrocyte phenotype, prevent hypertrophy and stimulate matrix synthesis (48). However, much less is known about how the gene is transcriptionally regulated in chondrocytes. Thus, we used here a more global approach by identifying highly conserved promoter/enhancer regions –and thus likely important- and then carried out gain- and loss-of-function experiments. Given that the gene is expressed in many cell types albeit at different levels, we were not surprised to find that some of those segments directed reporter expression in any cell type tested. Within one such segment and specifically segment 3, we did find that the putative ets binding sites are needed for Erg responsiveness. Further investigation is required to clarify how the upstream segment 4 encompassing the promoter region confers apparent chondrocyte enhancer specificity to the reporter construct. Overall, our data provide proof-of-principle evidence that PTHrP expression is responsive to, and can be significantly up-regulated by, Erg or Fli-1, indicating that the latter lie upstream in expression hierarchy and may be critical in establishing and modulating PTHrP expression in joints under normal or pathological circumstances.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Embryonic Death of Erg −/− Mice

| Embryos (viable (%of total sac number)) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Erg +/+ | Erg +/− | Erg−/− | Sacs (total #) |

| E9–9.5 | 7 (23) | 17 (57) | 6 (20) | 21 |

| E10.5 | 5 (28) | 8 (44) | 5 (28) | 18 |

| E11.5 | 3 (17) | 12 (67) | 0 | 18 |

| E13.5 | 3 (33) | 4 (44) | 0 | 9 |

| E14.5 | 1 (11) | 4 (44) | 0 | 9 |

| E18.5 | 3 (16) | 9 (47) | 0 | 19 |

| Postnatal (P2) | 5/5 | 9/9 | 0 | |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health RO1 grants AR046000 (M.I. and M.P.) and AR062908 (M.P. and M-E. I.), and the Japan Orthopaedics and Traumatology Foundation Inc. grant (No.213) (T.O). We thank the University of Cincinnati Mouse Genetics Core for their help in the creation of the Erg-floxed mice.

Footnotes

Author contributions

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. Dr. Iwamoto had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design. Iwamoto, Pacifici

Acquisition of data. All authors

Analysis and interpretation of data. Iwamoto, Pacifici, Enomoto-Iwamoto, Ohta, Okabe

References

- 1.Hunziker EB, Kapfinger E, Geiss J. The structural architecture of adult mammalian articular cartilage evolves by a synchronized process of tissue resorption and neoformation during postnatal development. Ostearthr Cart. 2007;15:403–413. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lefebvre V, Bhattaram P. Vertebrate skeletogenesis. Curr Opin Dev Biol. 2010;90:291–317. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(10)90008-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mackie EJ, Tatarczuch L, Mirams M. The skeleton: a multi-functional complex organ. The growth plate chondrocyte and endochondral ossification. J Endocrinol. 2011;211:109–121. doi: 10.1530/JOE-11-0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jay GD, Torres JR, Warman ML, Laderer MC, Breuer KS. The role of lubricin in the mechanical behavior of synovial fluid. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:6194–6199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608558104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aigner T, Soder S, Gebhard PM, McAlinden A, Haag J. Mechanisms of disease: roles of chondrocytes in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis - structure, chaos and senescence. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007;3:391–399. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loeser RF, Olex AL, McNulty MA, Carlson CS, Callahan M, Ferguson C, et al. Disease progression and phasic changes in gene expression in a mouse model of osteoarthritis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomlins SA, Rhodes DR, Perner S, Dhanasekaran SM, Mehra R, Sun XW, et al. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science. 2005;310(5748):644–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1117679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bock J, Mochmann LH, Schlee C, Farhadi-Sartangi N, Gollner S, Muller-Tidow C, et al. ERG transcriptional networks in primary acute leukemia cells implicate a role for ERG in deregulated kinase signaling. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e52872. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sorensen PH, Lessnick SL, Lopez-Terrada D, Liu XF, Triche TJ, Denny CT. A second Ewing's sarcoma translocation, t(21;22), fuses the EWS gene to another ETS-family transcription factor, ERG. Nat Genet. 1994;6(2):146–151. doi: 10.1038/ng0294-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qiao F, Bowie JU. The many faces of SAM. Science STKE. 2005;286:re7. doi: 10.1126/stke.2862005re7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharrocks AD. The ETS-domain transcription factor family. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2(11):827–837. doi: 10.1038/35099076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dhordain P, Dewitte F, Desbiens X, Stehelin D, Duterque-Coquillaud M. Mesodermal expression of the chicken erg gene associated with precartilaginous condensation and cartilage differentiation. Mech Dev. 1995;50:17–28. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(94)00322-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwamoto M, Higuchi Y, Koyama E, Enomoto-Iwamoto M, Yeh H, Abrams WR, et al. Transcription factor ERG variants and functional diversification of chondrocytes during long bone development. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:27–39. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iwamoto M, Tamamura Y, Koyama E, Komori T, Takeshita N, Williams JA, et al. Transcription factor ERG and joint and articular cartilage formation during mouse limb and spine skeletogenesis. Dev Biol. 2007;305:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rountree RB, Schoor M, Chen H, Marks ME, Harley V, Mishina Y, et al. BMP receptor signaling is required for postnatal maintenance of articular cartilage. PLoS Biology. 2004;2:1815–1827. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamekura S, Hoshi K, Shimoaka T, Chung U, Chikuda H, Yamada T, et al. Osteoarthritis development in novel experimental mouse models induced by knee joint stability. Osteoarth Cart. 2005;13:632–641. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glasson sS, Chambers MG, van den Berg WB, Little CB. The OARSI histopathology initiative - Recommendations for histological assessment of osteoarthritis in the mouse. Osteoarth Cart. 2010;18:517–523. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams JA, Kane M, Okabe T, Enomoto-Iwamoto M, Napoli JL, Pacifici M, et al. Endogenous retinoids in mammalian growth plate cartilage: analysis and roles in matrix homeostasis and turnover. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(47):36674–36681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.151878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yasuhara R, Ohta Y, Yuasa T, Kondo N, Hoang T, Addya S, et al. Roles of beta-catenin signaling in phenotypic expression and proliferation of articular cartilage superficial zone cells. Lab Invest. 2011;91(12):1739–1752. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2011.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rao VN, Papas TS, Reddy ES. Erg, a human ets-related gene on chromosome 21: alternative-splicing, polyadenylation, and translation. Science. 1987;237:635–639. doi: 10.1126/science.3299708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vijayaraj P, Le Bras A, Mitchell N, Kondo M, juliao S, Wasserman M, et al. Erg is a crucial regulator of endocardial-mesenchymal transformation during cardiac valve morphogenesis. Development. 2012;139:3973–3985. doi: 10.1242/dev.081596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koyama E, Shibukawa Y, Nagayama M, Sugito H, Young B, Yuasa T, et al. A distinct cohort of progenitor cells participates in synovial joint and articular cartilage formation during mouse limb skeletogenesis. Dev Biol. 2008;316:62–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jay GD, Torres JR, Rhee DK, Helminen HJ, Hytinnen MM, Cha C-J, et al. Association between friction and wear in diarthrodial joints lacking lubricin. Arthr Rheum. 2007;56:3662–3669. doi: 10.1002/art.22974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chambers MG, Cox L, Chong L, Suri N, Cover P, Bayliss MT, et al. Matrix metalloproteases and aggrecanases cleave aggrecan in different zones of normal cartilage but colocalize in the development of osteoarthritic lesions in STR/ort mice. Arthr Rheum. 2001;44:1455–1465. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200106)44:6<1455::AID-ART241>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirsch T, Swoboda B, Nah H-D. Activation of annexin II and V expression, terminal differentiation, mineralization and apoptosis in human osteoarthritic cartilage. Osteoarth Cart. 2000;8:294–302. doi: 10.1053/joca.1999.0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vortkamp A, Lee K, Lanske B, Segre GV, Kronenberg HM, Tabin CJ. Regulation of rate of cartilage differentiation by Indian hedgehog and PTH-related protein. Science. 1996;273:613–622. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5275.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cataisson C, Gordon J, Roussiere M, Abdalkhani A, Lindemann R, Dittmer J, et al. Ets-1 activates parathyroid hormone-related protein gene expression in tumorigenic breast epithelial cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;204:155–168. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindemann RK, Braig M, Hauser CA, Nordheim A, Dittmer J. Ets2 and protein kinase C epsilon are important regulators of parathyroid hormone-related protein expression in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Biochem J. 2003;372:787–797. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kato Y, Shimazu A, Nakashima K, Suzuki F, Jikko A, Iwamoto M. Effects of parathyroid hormone and calcitonin on alkaline phosphatase activity and matrix calcification in rabbit growth-plate chondrocyte cultures. Endocrinology. 1990;127:114–118. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-1-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schipani E, Lanske B, Hunzelman J, Luz A, Kovacs CS, Lee K, et al. Targeted expression of constitutively active receptors for parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone-related peptide delays endochondral bone formation and rescues mice that lack parathyroid hormone-related peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13689–13694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macica CM, Liang G, Nasiri A, Broadus AE. Genetic evidence of the regulatory role of parathyroid hormone-related protein in articular chondrocyte maintenance in an experimental mouse model. Arthr Rheum. 2011;63:3333–3343. doi: 10.1002/art.30515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruan MZC, Erez A, Guse K, Dawson B, Bertin T, Chen Y, et al. Proteoglycan 4 expression protects against the development of osteoarthritis. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:176ra34. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sampson ER, Hilton MJ, Tian Y, Chen D, Schwarz EM, Mooney RA, et al. Teriparatide as a chondroprotective therapy for injury-induced osteoarthritis. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:101ra93. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sparmann A, van Lohuizen M. Polycomb silencers control cell fate, development and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(11):846–856. doi: 10.1038/nrc1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diez-Roux G, Banfi S, Sultan M, Geffers L, Anand S, Rozado D, et al. A high-resolution anatomical atlas of the transcriptome in the mouse embryo. PLoS Biol. 2011;9(1):e1000582. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Godler DE, Stein AN, Bakharevski O, Lindsay MM, Ryan PF. Parathyroid hormone-related peptide expression in rat collagen-induced arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44(9):1122–1131. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van der Kraan PM. Osteoarthritis year 2012 in review: biology. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20(12):1447–1450. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glasson SS, Askew R, Sheppard B, Carito B, Blanchet T, Ma HL, et al. Deletion of active ADAMTS5 prevents cartilage degradation in a murine model of osteoarthritis. Nature. 2005;434(7033):644–648. doi: 10.1038/nature03369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Little CB, Barai A, Burkhardt D, Smith SM, Fosang AJ, Werb Z, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase 13-deficient mice are resistant to osteoarthritic cartilage erosion but not chondrocyte hypertrophy or osteophyte development. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(12):3723–3733. doi: 10.1002/art.25002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carrere S, Verger A, Flourens A, Stehelin D, Duterque-Coquillaud M. Erg proteins, transcription factors of the Ets family, form homo, heterodimers and ternary complexes via two distinct domains. Oncogene. 1998;16(25):3261–3268. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maroulakou IG, Bowe DB. Expression and function of Ets transcription factors in mammalian development: a regulatory network. Oncogene. 2000;19:6432–6442. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spyropoulos DD, Pharr PN, Lavenburg kR, Jackers P, Papas TS, Ogawa M, et al. Hemorrhage, impaired hematopoiesis and lethality in mouse embryos carrying a targeted disruption of the Fli1 transcription factor. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5643–5652. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.15.5643-5652.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Loughran SJ, Kruse EA, Hacking DF, de Graaf CA, Hyland CD, Willson TA, et al. The transcription factor Erg is essential for definitive hematopoiesis and the function of adult hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(7):810–819. doi: 10.1038/ni.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kruse EA, Loughran SJ, Baldwin TM, Josefsson EC, Ellis S, Watson DK, et al. Dual requirement for the ETS transcription factors Fli-1 and Erg in hemetopoietic stem cells and the megakaryocyte lineage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13814–13819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906556106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Southby J, O'Keeffe LM, Martin TJ, Gillespie MT. Alternative promoter usage and mRNA splicing pathways for parathyroid hormone-related protein in normal tissues and tumours. Br J Cancer. 1995;72(3):702–707. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu G, Iwamura M, di Sant'Agnese PA, Deftos LJ, Cockett AT, Gershagen S. Characterization of the cell-specific expression of parathyroid hormone-related protein in normal and neoplastic prostate tissue. Urology. 1998;51(5A Suppl):110–120. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00077-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sellers RS, Luchin AI, Richard V, Brena RM, Lima D, Rosol TJ. Alternative splicing of parathyroid hormone-related protein mRNA: expression and stability. J Mol Endocrinol. 2004;33(1):227–241. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0330227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adams SL, Cohen AJ, Lassova L. Integration of signaling pathways regulating chondrocyte differentiation during endochondral bone formation. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213(3):635–641. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.