Abstract

Interest in the consequences of family legal status for children has grown in response to immigration-related changes in the ethnic composition of American society. However, few population-based empirical studies devote attention to family legal status due to data limitations. Using restricted data from the California Health Interview Survey (2009), the primary objectives of this research are to identify and evaluate strategies for measuring this important determinant of life chances among Mexican-origin children. The results indicate that measurement strategies matter. Estimates of the size of status-specific segments of this population and their risks of living in poverty are sensitive to how family legal status is operationalized. These findings provide the foundation for a discussion of how various “combinatorial” measurement strategies may rely on untenable assumptions that can be avoided with less reductionist approaches.

Striking changes have occurred in the ethnic composition of the child population in the United States. According to the Census Bureau, the non-Hispanic white share of children less than 12 years of age declined from 69% to 55% between 1990 and 2011. This was largely due to the ascendance of Mexican-origin children from 8% to 17% of the total --- a change that is especially evident in traditional migration-receiving states. For example, California now includes one-third of all Mexican-origin children in the nation who, in turn, account for almost half of all children in the state. In contrast, 28% of the state’s children are non-Hispanic white and 6% are African American.

Such changes in population composition stem from immigration and the fertility of migrants and their descendants (Landale & Oropesa, 2007). Collectively, these sources of growth draw attention to parental nativity as a determinant of inequality in children’s life chances. Indeed, children of Mexico-born parents are more likely than their co-ethnic counterparts with U.S.-born parents to be impoverished. However, numerous strands of research reveal paradoxical findings about the consequences of parental nativity. The coupling of a relatively high risk of poverty with a low risk of living in a single-parent family among children of Mexican immigrants is a case in point (Landale, Oropesa, & Bradatan, 2006; Reimers, 2006; Van Hook, Brown, & Kwenda, 2004).

The role of nativity cannot be understood apart from legal status. Legal statuses are hierarchically-arranged positions established by institutions through the creation and enforcement of law. Immigration law regulates the admission and removal of non-citizens while alienage law specifies their rights (Romero, 2009). At the apex of the hierarchy are those who acquire citizenship through naturalization after at least three-to-five years as a permanent resident. Permanent residents occupy the middle position. Issued renewable “green cards” for 10 years that must be carried at all times, they have the (largely) unrestricted right to live and work in the United States (Department of Homeland Security, 2007). At the bottom are undocumented residents, who are at risk of deportation because their presence is unauthorized. About 6.8 million of nearly 12 million Mexico-born residents are unauthorized (Hoefer, Rytina, & Baker, 2012).

Non-citizens without green cards are highly vulnerable. Generally confined to poor jobs in secondary labor markets, they are ineligible for public programs that provide a safety net for the low-income population (Fortuny & Chaudry, 2012; Hall, Greenman, & Farkas, 2013). This vulnerability is often hidden in population-based studies of immigrant families (Clark, Glick, & Bures, 2009). Indeed, many of the most widely-used datasets only permit distinctions between naturalized citizens and non-citizens among the foreign born. As a result of the inability to partition non-citizens into permanent residents and undocumented residents, family legal status is frequently a source of unmeasured heterogeneity in studies of the Mexican-origin population.1

The legal status of parents is crucial for children’s circumstances, but its importance cannot be assessed without adequate measurement. Some studies identify “mixed-status” families based on distinctions between foreign-born parents and native-born children using indirect methods (Fix & Zimmermann, 2001; Passel, 2006; Passel & Clark, 1998; Van Hook et al., 2015). Side information from special-purpose surveys is used to generate a probability-based algorithm to impute status in surveys without direct questions. Families are then classified according to the probable statuses of parents and children (see Van Hook et al., 2015 on indirect methods). Those with a probable undocumented parent and a native-born child would be classified as “mixed status.”

Although direct questions are rarely available in population-based studies, the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) and the Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey (LA FANS) are partial exceptions. Ziol-Guest and Kalil (2012) use the SIPP to examine the health-related consequences of family immigration status for children. Because the migration module is restricted to household members who are eligible to enter the labor force, no information is available on the specific status of non-citizen children under age 15 or the status of non-coresident parents. This results in measures of family legal status that are based on two parents for some children and one parent for others. Similarly, a fully informed measure of family legal status is problematic with the LA FANS, despite direct questions on the immigration status of sampled adults and children’s primary caregivers. This survey does not collect information on the legal status of parents who live apart from children and fathers who are not the sampled adult or the primary caregiver. As a result, “family” legal status is typically based on the mother in the household (e.g. Landale et al., 2015).

These issues are problematic if absent parents are financially and non-financially involved in children’s lives (Hummer & Hamilton, 2010; Landale & Oropesa, 2001; Lerman, 2010). To our knowledge, no studies examine whether the legal status of non-coresident parents matters for child poverty. We hypothesize that the likelihood of poverty will be associated with the legal status of coresident and non-coresident parents. Children of undocumented non-coresident parents will be negatively affected because low wages impinge on the ability to make financial contributions. To reiterate, it is rare to have information on the legal status of children and both of their parents to evaluate these issues. Even when direct questions are asked, they are often restricted to parents in the same household or to the parent who answers the survey on behalf of a child.2

Some studies in allied fields that are grounded in the social sciences have been able to construct more complete measures of family legal status from information on both parents (e.g., Guendelman et al., 2005; Ortega et al., 2009). However, disagreement about which distinctions matter and how to aggregate them across family members indicates that this is an underdeveloped area of inquiry. Such issues are potentially crucial for studies immigrants’ children, including those that focus on estimating the size of different segments of the population and those that focus on differences in circumstances or outcomes.

Using restricted data from the 2009 California Health Interview Survey (CHIS), we examine measurement strategies for characterizing the legal status of children’s families. The first objective is to identify different combinatorial strategies from studies that are based on direct questions about the statuses of parents and children. This is important because various strategies have been used to characterize family legal status from the statuses of separate members, with underlying principles and assumptions for doing so often implicit. Because systematic consideration of alternative approaches to this topic is necessary to advance research on immigrant families, the second objective is to evaluate the implications of measurement strategies for inferences about the size of status-specific segments of the Mexican-origin child population and their relative risks of poverty. The relative merits of measurement strategies that use information on both parents is of primary interest, not sampling or survey design per se. Nonetheless, we touch secondarily on the potential implications of the absence of information on non-coresident parents in some household surveys for inferences. Overall, our analysis shows that combinatorial procedures are parsimonious, but potentially problematic. Thus, an alternative approach is offered to illustrate how family legal status matters for children.

These objectives serve research and policy-relevant interests. The prominence of immigration on the public agenda reflects concerns about the size of the undocumented population and the long-term prospects of their offspring (Passel, 2011; Suárez-Orozco & Yoshikawa, 2013; Suárez-Orozco et al., 2011; Yoshikawa 2011). If inferences about these issues are sensitive to strategies for classifying legal status, then measurement is a non-trivial issue. We focus on poverty because it is a major determinant of children’s life chances (Duncan et al., 1998). Moreover, the poverty-legal status intersection is conspicuous for its absence in many studies of the children of immigrants that focus exclusively on nativity and generation due to data limitations (see Borjas, 2011; Oropesa & Landale, 1997; Reimers, 2006). However, our study is not a full-scale investigation of economic deprivation. Rather, poverty is used to illuminate the implications of measurement procedures for understanding how parental legal status affects children.

The organization of this article departs from the standard outline of most investigations (i.e. theory→data→ findings). The next section describes the data and specific survey items that serve as building blocks for constructing measures of family legal status. After presenting descriptive statistics for the specific items, we draw upon previous studies to show how information on separate members may be combined to characterize families as collective entities. The analysis then addresses how measurement matters for estimates of the size of family legal status groups and for their risks of poverty. Thus, untenable assumptions of “combinatorial” strategies are exposed.

Data & Methods

We use restricted data from the 2009 CHIS. Conducted by Westat for the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research and the California Departments of Public Health and Health Care Services, this is the most comprehensive state health survey in the United States. This telephone survey targets children (0–11), adolescents (12–17), and adults using a multi-stage sampling design with 44 counties/county groups as geographic strata for random-digit dialing. The “child sample” is examined here. Within each household, one focal child age 0–11 was randomly selected and the adult who was most knowledgeable about the child was interviewed.

The analysis is limited to 2,930 children identified as Mexican, Mexican American or Chicano from questions on the ancestry of those classified as Latino. Children whose parents were deceased or not living in the United States are excluded. Because these children are few in number (see below), the analytic sample is essentially representative of the state’s non-institutionalized Mexican-origin child population. Analyses are based on weighted data, with weights normalized to preserve the actual sample size and standard errors adjusted for the complex sample design. Missing data are imputed by the CHIS with hot-deck imputation.

Poverty Status

Poverty reflects the ratio of household income to federal poverty thresholds. Children living below the poverty line (coded as 1) are contrasted with those living at or above it (coded as 0).

Immigration Status

The CHIS permits four statuses to be determined for the focal child, mother, and father---regardless of where they live. The categories are: (1) native-born citizen, (2) naturalized citizen, (3) permanent resident (green card) and (4) non-permanent resident (no green card). Although the latter includes temporary visa holders, almost all Mexico-born persons without a green card are undocumented (Passel, 2007).3 The inclusion of legal status questions on non-coresident parents is rare in household-based surveys. Yet, information on non-coresident parents is potentially important because it allows for examination of issues that cannot be broached in many surveys. The empirical question whether such parents matter for the family circumstances of children is non-ignorable.

Family Structure

Family legal status measures are typically gender blind in their treatment of parents and do not account for family structure. We identify two-parent and single-parent families, with the latter partitioned for some analyses by the gender of the parent. Two-parent families formed by married vs. cohabiting couples cannot be distinguished.

Methodological Considerations

Several methodological considerations are worth noting. First, the interview completion rate for children is approximately 75% with an overall child-sample response rate of 14% (California Health Interview Survey, 2011). This rate is low by historical standards, but the case for using these data is strong. Response rates for telephone surveys have declined in recent years and the experience of the CHIS is not atypical (Pew Research Center, 2012).4 Moreover, non-response bias cannot be assumed from the magnitude of the response rate, given the weak association between the two (Groves, 2006; Groves & Peytcheva, 2008; Pew Research Center, 2012; Massey & Tourangeau, 2013). The case is further strengthened by the fact that replication is a goal of research and the CHIS has been used extensively in the health literature.5

Second, a comparison of direct measurement approaches with indirect (two-stage) approaches that impute legal status is neither necessary nor possible. The CHIS does not include key variables (e.g., occupation, industry) that are required to assign persons to categories using indirect methods. This constraint does not detract from our goal of evaluating procedures based on direct measures, since direct measures are considered the gold standard. Direct questions on legal status are valid and reliable (Bachmeier, Van Hook, & Bean, 2014).

Third is omitted variable bias in the association between legal status and poverty. It is important to remember that we focus on poverty to demonstrate the advantages and disadvantages of strategies for dealing with legal status. A comprehensive investigation of the mechanisms for observed associations is beyond the purview of this research and the capabilities of surveys that lack information on occupation and industry. Still, we report results of additional analyses which show that findings are not sensitive to the inclusion of covariates such as child age and the coresident parent’s language proficiency, education, and employment. Similarly, the ethnicity of each parent is not ascertained in the child survey and cannot be used to classify children. This has minimal impact because the Mexican-origin population exhibits a very high level of endogamy in parenthood—86% for immigrants and natives combined (Landale, Oropesa, & Bradatan, 2006).

Last, numerous sources of family complexity may intersect with legal status, including parental death, parental residence abroad, and step-parent relationships. There is little transparency about such issues in prior studies, but they are not major concerns.6 Our analytic sample excludes children with a deceased parent (N=6) or a non-U.S. resident parent (N=25) because such parents lack a legal status. However, since the CHIS imputed the “likely” legal status of these parents, we tested whether our results are sensitive to this exclusion and found that that they are not. Further, these data suggest that transnational parenting is very uncommon for young children in California.

Results

The Immigration Status of Children and Parents

Table 1 provides frequencies for the statuses of Mexican-origin children and their parents. Here we see that 96% of nearly three million children are native born. Just 1% are naturalized citizens or permanent residents and 2% lack a green card. In contrast, parents are heterogeneous. About 40% of mothers and 34% of fathers are native born, with the undocumented the second largest category at about 30% for each parent. If the base is restricted to those born in Mexico, this share is 47% for mothers and 43% for fathers. Of course, the latter figures imply that the majority of immigrant parents are legal residents.

Table 1.

Legal Status: Mexican-Origin Children Age 0–11 in California (2009)

| Percent | Weighted N | Unweighted N | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child | |||

| U.S.-born citizen | 96.4 | 2,699,180 | 2,782 |

| Naturalized citizen | .6 | 17,965 | 27 |

| Permanent resident | .7 | 19,676 | 30 |

| Undocumented | 2.2 | 62,876 | 91 |

| Total | 100.0 | 2,799,697 | 2,930 |

| Mother | |||

| U.S.-born citizen | 39.4 | 1,103,761 | 1,039 |

| Naturalized citizen | 12.1 | 340,117 | 397 |

| Permanent resident | 19.7 | 551,944 | 639 |

| Undocumented | 28.7 | 803,874 | 855 |

| Total | 100.0 | 2,799,697 | 2,930 |

| Father | |||

| U.S.-born citizen | 34.0 | 953,158 | 938 |

| Naturalized citizen | 18.1 | 507,962 | 576 |

| Permanent resident | 19.7 | 550,516 | 599 |

| Undocumented | 28.1 | 788,061 | 817 |

| Total | 100.0 | 2,799,697 | 2,930 |

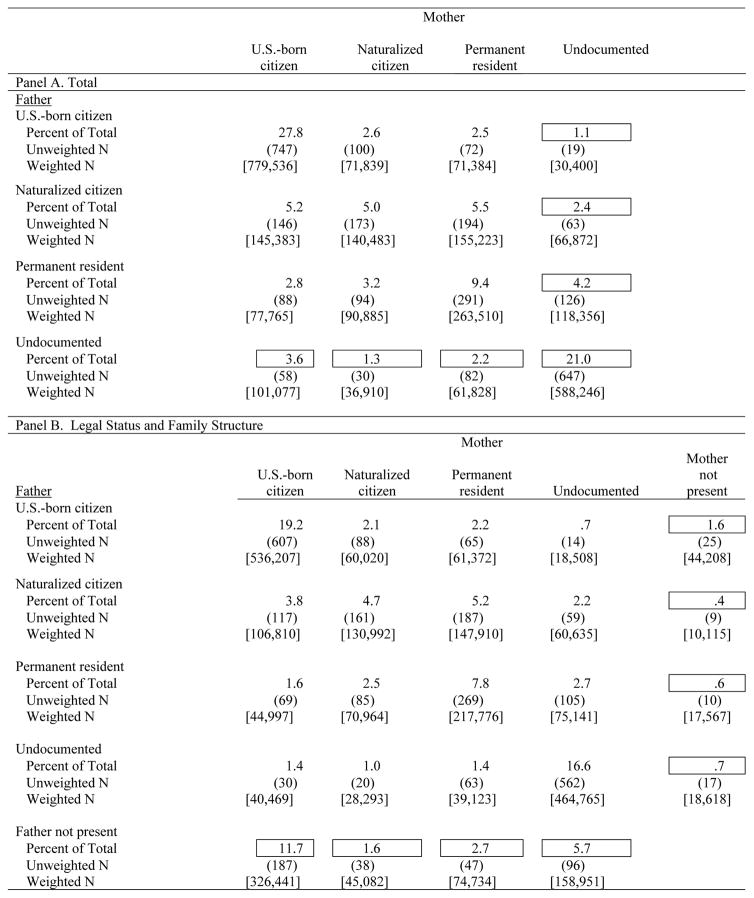

Table 2 presents the joint distribution of mother’s and father’s legal status. The top panel shows how their statuses intersect regardless of family structure. Summing the values on the main diagonal indicates that a majority of children have same-status parents (63%), with both native-born (28%) and both undocumented (21%) leading the way. An additional fifth are in “mixed-nativity” families with one native-born and one foreign-born parent, bringing the total for those with at least one native-born parent to 46% (46=18+28). At the other extreme, the boxed figures indicate that 36% of children have at least one undocumented parent. In numeric terms, a million Mexican-origin children in California have a mother or father who is an unauthorized immigrant.

Table 2.

Mexican-Origin Children by Parents’ Legal Status and Family Structure

Because the legal status of non-coresident parents may affect access to resources, the bottom panel takes family structure into account. Not surprisingly, absent fathers are relatively common. 22% of children live with a single mother and 3% live with a single father (boxed cells). Moreover, the risk of the former is associated with legal status. The third largest cell is for those with a single U.S.-born mother. These 12% constitute one-third of all children with native-born mothers (col. 1). The 6% living with a single undocumented mother account for one-fifth of those with undocumented mothers (col. 4). Lower risks are even more apparent for the other categories. The 2–3% with single naturalized citizen and permanent resident mothers account for 14% of each group.

Measurement Strategies and the Sizes of Subpopulations

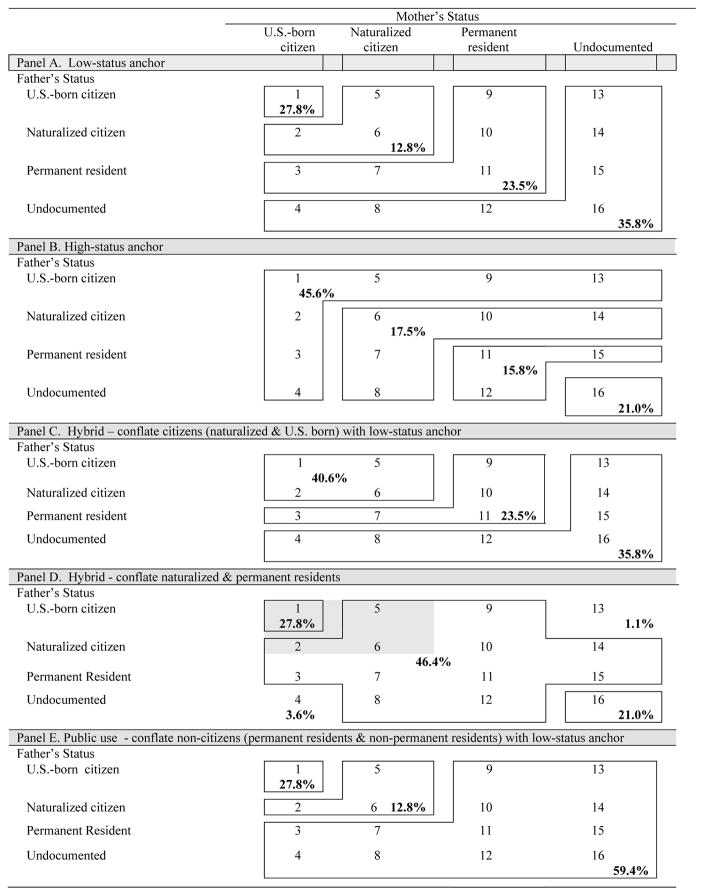

Strategies to summarize family legal status could utilize all information on children and parents. A 64-category measure would maximize the information from a four-category indicator for each of three focal family members (64 = 43). However, child status can be excluded with little loss of information because almost all children are native born and their status cannot affect family poverty. This suggests that a fully informative measure requires 16 categories to represent the 4 x 4 cross-tabulation of mother’s and father’s status, but this would also be unwieldy. To reduce complexity, studies conducted in allied fields offer a number of strategies for combining categories (Guendelman et al., 2005; Zhihuan, Yu, & Ledsky, 2006; Kinchloe, Frates, & Brown, 2007; Ortega et al., 2009; Perez et al., 2009; Stevens, West-Wright, & Tsai, 2010; Ziol-Guest & Kalil, 2012). Although transparency is sometimes compromised by imprecise language, Table 3 describes several combinatorial measurement strategies from this literature to accomplish the first research objective. Each panel corresponds to a particular strategy. Numbered cells and boxed areas identify how the cells are combined. Bolded percentages indicate the share of the sample in each area.

Table 3.

Distribution of Mexican Children in California by Legal Status of the Mother and Father – 2009 (Weighted)

Ziol-Guest and Kalil (2012) anchor measurement in the parent with the lowest status (Panel A). In the low-status anchor strategy, children of one and two undocumented parents are combined. Among those without an undocumented parent, the child of one permanent resident would be classified with the child of two permanent residents. This differs from a high-status anchor strategy where the child of one undocumented parent and one permanent resident parent would be classified with a child of two permanent resident parents (Panel B). A child with an undocumented parent and a native-born parent would be classified with the child of two native-born parents. Thus, anchoring strategies diverge for mixed-status parents.

Hybrid strategies follow different principles for different statuses. Guendelman et al. (2005) preserve the low-status anchor for children with at least one non-citizen parent, but conflate naturalized and native-born citizens (Panel C). A child with two naturalized parents is treated the same as a child with two native-born parents or one of each. Another hybrid approach conflates naturalization and permanent residence to treat a child with two naturalized parents the same as a child with two permanent resident parents or one of each (Panel D; see Ortega et al., 2009).7 Public-use files require conflation of permanent and non-permanent residents since only the native born, naturalized citizens and non-citizens can be identified. To illustrate, Panel E shows a low-status anchor approach even though other variants are possible (see Perez et al., 2009).

These panels also address the second objective in showing that estimates are sensitive to classificatory procedures. The low-status anchor identifies 28% with two native-born parents. Another 13% have one native-born and one naturalized parent or two naturalized parents. 24% and 36% live in a family in which the lowest status parent is a permanent resident or undocumented, respectively. High-status anchoring places 45% in the top category with at least one U.S.-born parent, followed by 18% with a naturalized citizen and 16% with a permanent resident parent among the remainder. One-fifth of children are in the bottom group with two undocumented parents. Thus, the vast majority have at least one citizen or permanent resident parent (80%).

As for hybrid strategies, low-status anchoring combined with conflating native-born and naturalized citizens in Panel C places 40% of children in the top group. Panel D shows that 46% fall between the extremes when naturalization and permanent residence are conflated, with shares in extreme cells the same as their counterparts under low (cell 1) and high-status anchoring (cell 16). The public-use approach in Panel E shows that conflating the two non-citizen categories places 60% into the lowest category, compared to 36% in Panel A. With high-status anchoring, 37% would be in the bottom group of two parents who are non-citizens (cells 11, 12, 15, 16), compared to 21% in Panel B. Thus, this approach offers limited insights into the Mexican-origin population.

The Sensitivity of Estimates to the Treatment of Non-Coresident Parents

Although this analysis focuses on measurement strategies when information is available on both coresident and non-coresident parents, it is worth taking a slight detour to note the implications of the presence or absence of this information. This can be achieved by aggregating cells in Panel B of Table 2 to reveal what would have happened if questions had only been asked about parents who lived in the same household as their children; that is, if information about non-coresident parents was unavailable (e.g. as with the SIPP). For the sake of brevity, we focus on the high-status and low-status anchoring strategies. Under low-status anchoring, limiting information to coresident parents places 32% of children in undocumented families and 23% in “green card” families. The estimates are 36% and 24% for each type, respectively, when information on non-coresident parents is used as well. Under high-status anchoring, 23% of children are in undocumented families based on coresident parents only and 21% are in undocumented families based on coresident and non-coresident parents. These figures are in the 15–16% range for those in green card families using each scheme. Such similarities in estimates indicate that the exclusion of information on absent parents does not have significant implications for summarizing the family legal status of Mexican-origin children in the aggregate using anchoring strategies.8 The question of whether non-coresident parents matter for poverty remains open.

Measurement Strategies and the Risk of Poverty

Table 4 turns to measurement and the risk of poverty. The first column identifies cell numbers, the second reproduces the shares from the previous table, and the third provides the poverty rate. The strategies differ in the extent to which they conceal heterogeneity. If each parent is considered separately, the difference between U.S.-born and naturalized citizens is relatively small even though it is not unremarkable. About 25% of those with native-born and 17% of those with naturalized-citizen mothers are impoverished.9 These figures reverse to 21% for native-born and 27% for naturalized fathers. Still, risks increase greatly for those furthest from citizenship. The poverty rate is 42–47% for children of green card holders and 69–71% for children of undocumented parents. Such figures are a stark reminder of the strong link between hardship and legal status.

Table 4.

Poverty Rates by Legal Status Strategies

| Cell number in Table 3 | Percent | Poverty | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | |||

| Mother’s status | |||

| U.S.-born citizen | 1–4 | 39.4 | 25.4*** |

| Naturalized citizen | 5–8 | 12.1 | 17.1*** |

| Permanent resident | 9–12 | 19.7 | 41.6***b |

| Undocumented | 13–16 | 28.7 | 70.5c |

|

|

|||

| FRao-Scott | 55.7, p<.001 | ||

| Father’s status | |||

| U.S.-born citizen | 1,5,9,13 | 34.0 | 20.5*** |

| Naturalized citizen | 2,6,10,14 | 18.1 | 26.7*** |

| Permanent resident | 3,7,11,15 | 19.7 | 47.4***c |

| Undocumented | 4,8,12,16 | 28.7 | 69.0c |

|

|

|||

| FRao-Scott | 43.2, p<.001 | ||

|

| |||

| Panel A. Low-status anchor | |||

|

| |||

| Both parents U.S.-born citizens | 1 | 27.8 | 20.6*** |

| Lowest parent naturalized citizen | 2,5,6 | 12.8 | 17.9*** |

| Lowest parent permanent resident | 3,7,9–11 | 23.5 | 35.8***b |

| Lowest parent undocumented | 4,8,12–16 | 35.8 | 67.2c |

|

|

|||

| FRao-Scott | 46.9, p<.001 | ||

|

| |||

| Panel B. High-status anchor | |||

|

| |||

| Highest parent U.S.-born citizen | 1–5,9,13 | 45.6 | 24.6*** |

| Highest parent naturalized citizen | 6–8,10,14 | 17.5 | 26.4*** |

| Highest parent permanent resident | 11,12,15 | 15.8 | 57.3**c |

| Both parents undocumented | 16 | 21.0 | 74.2c |

|

|

|||

| FRao-Scott | 55.2, p<.001 | ||

|

| |||

| Panel C. Hybrid-conflate citizens with low-status anchor | |||

|

| |||

| Both parents U.S. born or naturalized citizens | 1,2,5,6 | 40.6 | 19.8*** |

| Lowest parent permanent resident | 3,7,9,10,11 | 23.5 | 35.8***c |

| Lowest parent undocumented | 4,8,12–16 | 35.8 | 67.2c |

|

|

|||

| FRao-Scott | 71.6, p<.001 | ||

|

| |||

| Panel D. Hybrid-conflate naturalized & permanent residents | |||

|

| |||

| Both parents U.S.-born citizens | 1 | 27.8 | 20.6*** |

| 1+ parent naturalized or permanent resident | 2,3,5–8,9–12,14,15 | 46.4 | 35.3***b |

| Both parents undocumented | 16 | 21.0 | 74.2c |

|

|

|||

| FRao-Scott | 51.1, p<.001 | ||

|

| |||

| Panel E. Public Use-conflate non-citizens with low-status anchor | |||

|

| |||

| Both parents U.S.-born citizens | 1 | 27.8 | 20.6*** |

| Lowest parent naturalized citizen | 2,5,6 | 12.8 | 17.9*** |

| Lowest parent non-citizen | 3,4,7,8,9–12,13–16 | 59.4 | 54.8c |

|

|

|||

| FRao-Scott | 43.3, p<.001 | ||

Note: Two cells for Panel D are omitted (cells 4 and 3, see Table 3). Asterisks indicate significance using the lowest category as the reference:

p<.05,

p<.001,

p<.001.

Letters indicate significance using the highest category as the reference:

p<.05,

p<.001,

p<.001.

A negative association is also evident in the remaining panels. Poverty rates range from 20% (Panel C) to 25% (Panel B) in the top category and from 67% to 74% in the bottom category, except for the public-use figure of 55% (Panel E). The impact of decisions is more pronounced for the intermediate categories under the anchoring strategies. 36% of children whose lowest status parent is a permanent resident are impoverished, compared to 57% of children whose highest status parent is in this category. The impact of decisions is also substantial for hybrid strategies; a nuanced view of how risks change in the middle part of the distribution is obstructed by conflating naturalized citizens with permanent residents (Panel D) or with native-born citizens (Panel C). Thus, some strategies have a limited ability to reveal substantial differences in poverty for intermediate categories and the public-use file hides the extreme risk of poverty among the undocumented.

The Alternative

Although such findings show that measurement matters, the starting point for assessing how family legal status should be measured is the assumptions that undergird combinatorial strategies: (1) family legal status reflects the joint statuses of both parents; (2) statuses should be combined without attention to gender; and (3) statuses can be collapsed without sacrificing information. These potentially problematic assumptions require empirical scrutiny.

Table 5 displays odds ratios from a series of logistic regressions for poverty. Treating the native born as the reference category, column 1 presents bivariate parameter estimates. Columns 2 and 3 present multivariate estimates for the statuses of both parents only and both parents plus family structure (respectively). In column 1, children whose mothers are naturalized citizens are significantly less likely than those with native-born mothers to be impoverished (odds ratio = .61). This is inconsistent with the non-significant odds ratio for fathers. Results for both mothers and fathers show elevated risks of poverty for children with permanent resident or undocumented parents. The odds for children with undocumented mothers are seven times the odds for those with native-born mothers. The odds ratio for those with undocumented fathers is even higher at 8.6.

Table 5.

Odds Ratios from Logistic Regressions: Poverty for All Children (N=2,930)

| U.S. Born as reference | Undocumented as reference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Bivariate | Multivariate | Bivariate | Multivariate | |||

|

| ||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Mother’s Status | ||||||

| U.S. born | ----- | ----- | ----- | .14*** | .36*** | .28*** |

| Naturalized | .61* | .43** | .53* | .09*** | .16*** | .15*** |

| Permanent | 2.09** | 1.30 | 1.71* | .30*** | .47*** | .47*** |

| Undocumented | 7.04*** | 2.79*** | 3.63*** | ----- | ----- | ----- |

| Wald χ2 | 181.6*** | 51.3*** | 56.1*** | 181.6*** | 51.3*** | 56.1*** |

| Father’s Status | ||||||

| U.S. born | ----- | ----- | ----- | .12*** | .23*** | .25*** |

| Naturalized | 1.41 | 1.35 | 1.47 | .16*** | .31*** | .37*** |

| Permanent | 3.49*** | 2.84*** | 2.65*** | .41*** | .66 | .66 |

| Undocumented | 8.63*** | 4.30*** | 4.00*** | ----- | ----- | ----- |

| Wald χ2 | 111.3*** | 32.0*** | 22.9*** | 111.3*** | 32.0*** | 22.9*** |

| Family Structure | ||||||

| Single parent | 2.16*** | 2.80*** | 2.16*** | 2.80*** | ||

| Two parent | ----- | ---- | ----- | ----- | ||

| Wald χ2 | 27.0*** | 29.7*** | 27.0*** | 29.7*** | ||

Note: Estimates are based on weighted data with adjustments for the complex sample design. Multivariate models are limited to the variables shown.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001.

The multivariate model in column 2 indicates that entering the statuses of both parents simultaneously does not substantially change the pattern of results, despite the non-significance of the estimate for permanent resident mothers and the lower estimates for undocumented parents. The odds ratio for undocumented mothers declines from 7.0 to 2.8 and that for undocumented fathers declines from 8.6 to 4.3. Column 3 indicates that controlling for family structure has little effect on the estimates except to restore the significance of the parameter estimate for children of permanent resident compared to native-born mothers. Thus, the odds ratios suggest that the statuses of both mothers and fathers matter in all models. This conclusion is reinforced by the significant Wald Tests (Type III effects) throughout this table. Mother’s status and father’s status independently improve the fit of all multivariate models.10

Columns 4–6 highlight differences among the foreign born by treating the undocumented as the reference category. All contrasts between children with undocumented mothers and permanent resident or naturalized citizen mothers are significant. The likelihood of poverty is progressively greater as one descends the status hierarchy for foreign-born mothers. This is also the case for fathers although the odds ratio for permanent residents is borderline significant (.66, p<.08). Column 6 shows that the odds ratios for poverty among children with naturalized mothers and permanent resident mothers, respectively, are less than one-fifth (.15) and about half (.47) that for children with undocumented mothers. Estimates for father’s status have a similar pattern. In addition, these results reflect the well-known higher risk of poverty among children of single parents. Regardless of immigration status, their odds of living below the poverty line are 2–3 times greater than the odds for those in two-parent families.11

Our analytic focus on the associations between poverty, legal status and family structure is consistent with the methodological objectives of this paper. Nonetheless, we conducted additional multivariate analyses that took various forms of capital into account (not shown). These included the education and English proficiency of the adult parent who was most knowledgeable about the child and the employment of coresident parents. Child age in years was also included to recognize that constraints on parents’ use of time loosen as children age. Briefly, all multivariate results are consistent with those presented above. Mother’s (Wald χ2 = 9.48, p<.05) and father’s status (Wald χ2 = 10.95, p<.05) are independently associated with poverty after the larger set of covariates is controlled. For example, the odds ratios are .55 (p<.05) for permanent resident mothers and .25 (p<.01) for naturalized citizen mothers when undocumented mothers are treated as the reference and all variables are controlled. With undocumented fathers as the reference, odds ratios are .71 (p=n.s.) for permanent residents, .48 (p<.05) for naturalized citizens and .38 (p<.01) for native-born citizens. The estimate for single parents also remains significant (2.35, p<.001).12

Table 6 extends this line of inquiry with an analysis restricted to children living with single mothers (N=368). It should be noted that the power of statistical tests is reduced for this subpopulation, especially for contrasts involving the relatively few children of permanent resident and naturalized single mothers. However, the bivariate results for children living with single mothers are generally similar to those for the overall sample. Poverty appears to be inversely associated with the legal status of mothers and perhaps non-coresident fathers, despite the nonsignificance of some coefficients. Children of undocumented single mothers are much more likely than children of native-born or naturalized single mothers to live below poverty. The risks of poverty are also high for the children of single mothers in the bivariate model when the absent father is undocumented.

Table 6.

Odds Ratios from Logistic Regressions: Poverty for Children of Single Mothers (N=368)

| U.S. born as reference | Undocumented as reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bivariate | Multivariate | Bivariate | Multivariate | |

| Mother’s status | ||||

| U.S. born | ----- | ----- | .20*** | .31* |

| Naturalized | .48 | .40 | .09*** | .12** |

| Permanent | 3.37 | 2.67 | .67 | .83 |

| Undocumented | 5.07*** | 3.23* | ---- | ----- |

| Wald χ2 | 29.1*** | 13.9** | 29.1*** | 14.0** |

| Father’s status | ||||

| U.S. Born | ----- | ----- | .24*** | .42 |

| Naturalized | 1.33 | 1.27 | .32** | .54 |

| Permanent | 2.40 | 1.57 | .58 | .67 |

| Undocumented | 4.13*** | 2.36 | ----- | ----- |

| Wald χ2 | 12.9** | 3.93 | 12.9** | 3.93 |

Note: Estimates are based on weighted data with adjustments for the complex sample design. The multivariate model is limited to the status of both parents.

p < .05;

p< .01;

p< .001.

When both parents’ statuses are included in the multivariate model, the basic pattern is unchanged. Still, the results are equivocal. Among children of single mothers, the absent father’s status is not significant (Wald χ2 = 3.9, p <.28) in the multivariate model even though the odds ratio of 2.36 (p<.053) for undocumented fathers is borderline significant. This “near result” requires additional scrutiny to determine whether it reflects the ability of fathers to make financial contributions or unmeasured characteristics of the mother that affect the likelihood of poverty.13, 14

Interactions

The above results demonstrate that combinatorial measures that collapse categories may affect estimates of the size of vulnerable populations, differences in risks and each parent’s contribution to risks. However, determining whether there is an empirical foundation for combining categories requires additional analysis based on the intuition that the decision to combine variables should hinge on whether doing so provides more information than considering each separately. In this vein, numerous multiplicative tests for interactions between mother’s and father’s status were conducted for all Mexican-origin children as well as three subpopulations consisting of those living with: two parents; a single-parent mother; and two parents or a single-parent mother. The sensitivities of tests to model specification were also examined by including and excluding family structure along with the covariates. Additional tests involved family structure*parent status. Needless to say, these tests are impervious to grouping error because they utilize the full array of categorical distinctions.

All results suggest that there is no empirical justification for combining the individual items into a single measure. No tests for interaction were significant. The addition of the nine terms for the mother’s status*father’s status interaction, for example, do not improve the fit of a model limited to each variable separately (Wald χ2 = 13.2, p=.15) or each variable and family structure (Wald χ2=11.1, p=.27) for the total sample. Similarly, legal status is not conditioned by family structure for those living with two parents and single-parent mothers. In short, the legal statuses of mothers and fathers are significant independent causes of poverty that do not condition the effects of each other.

Conclusion

Immigration has emerged as a leading issue on the public agenda, partly in response to the sizable number of undocumented adults and children. The sheer magnitude of this population has contributed to a growing recognition of legal status as a key source of inequality in life chances. At the same time, the “problem” for Mexican-origin children is not necessarily reducible to the lack of documentation per se if boundaries are hardening across all categories that define the legal status distribution (Coutin, 2011). Attention is necessary to the full range of statuses that potentially affect family circumstances to illuminate the lives of the children of immigrants.

Although notable population-based studies can be identified, progress on this front has been slowed by the absence of data on legal status in most widely used government surveys. Progress has also been hampered by the lack of consensus on how to measure family legal status from information on individual family members. Using restricted data on a representative sample of Mexican-origin children in California, this study surmounts these barriers to provide evidence-based guidance for moving family legal status to center stage. To advance research, it is necessary to evaluate different strategies for measuring family legal status, as opposed to the child’s legal status, because nearly all of the three million Mexican-origin children in the state are native born. In contrast, their parents are a heterogeneous mix of citizens, permanent residents, and undocumented residents. One million children have at least one undocumented parent.

These key social facts have important implications for measurement. The measurement issue is how to treat the statuses of parents, rather than children. Prior studies offer numerous combinatorial strategies to classify families based on the status of parents and little guidance for determining the optimal approach for specific research situations. Still, progress can be made by acknowledging that combinatorial approaches may assume that family legal status: (1) reflects the statuses of both parents (jointly); (2) is gender-neutral with regard to mothers and fathers; (3) reflects the statuses of coresident and non-coresident parents; (4) involves equivalent categories that are collapsible; and (5) can be described without information on siblings and other coresident relatives. These assumptions should be evaluated empirically, even though some data-related barriers are insurmountable.

The five strategies examined here are grounded in operational decisions that are amenable to different perspectives on the structure of opportunities. Low-status anchoring draws attention to the position of parents with the least access to opportunities while high-status anchoring draws attention to the position of parents with the greatest access to opportunities. In contrast to anchoring strategies that emphasize the overriding importance of particular positions, hybrid strategies make assumptions about the equivalence of positions when they conflate the native born with naturalized citizens, naturalized citizens with permanent residents, or permanent residents with the undocumented. Assumptions about nonessential distinctions are potentially problematic, as well as empirically testable.

Evidence that these assumptions are potentially problematic is available from results that are sensitive to anchoring and conflating categories. Estimates of the shares of children in specific family legal status categories and the risk of poverty within each category vary across strategies. This raises the issue of what should be maximized in measures of family legal status. Because most young children live with one set of family members, some decisions about how to treat categories maximize parsimony with a single measure created from the joint characteristics of parents. However, this erroneously assumes that the combined characteristics of parents offer more information about family circumstances than is available from considering each separately. Negative tests for interaction indicate that there is no empirical basis for combinatorial approaches to child poverty. Information is not gained by aggregating the statuses of parents into a single measure. On the contrary, considering each parent’s legal status separately achieves parsimony without sacrificing information. Differences in child poverty are evident by legal status, with the most pronounced risk evident for children of undocumented mothers and fathers.

The magnitude of differences in poverty by the status of each parent and tests for interactions are relevant to evaluating the assumption of gender neutrality. A gender-neutral approach would be contraindicated by different levels of poverty by each parent’s status, different patterns of poverty across categories for each parent, or a significant interaction between the legal statuses of parents. There is no evidence of any of these situations. The percentages of children in poverty are basically the same whether the mother’s legal status or the father’s legal status is considered. Approximately 70% of children with an undocumented mother and 69% with an undocumented father are below poverty. Similarly, the poverty rates for those with permanent resident mothers and fathers are 42% and 38% respectively. The absence of significant interactions is also consistent with the gender-neutral analytic orientations of the combinatorial strategies that are prevalent in this literature. These findings may not be generalizable to other outcomes of interest.

At the same time, measurement should be synchronized with theoretical priorities. A gender-neutral approach to family status may be untenable if the division of labor and the organization of responsibilities within households are keys to outcomes. Examples of such outcomes are the utilization of medical services or interaction with other institutions such as schools (see Pinto and Coltrane 2009). The point is that assumptions must be evaluated and tailored to particular research problems. It is not difficult to imagine that there are situations where the status of mothers and fathers both matter, but for different reasons. This is impossible to discover with gender neutral strategies that obscure how mothers and fathers contribute to the lives of Mexican-origin children.

A final point pertains to who should be considered “family.” Most investigators assume that the legal statuses of parents are most relevant for children even though Mexican families are complex entities that are often extended. In our view, the instability of extended families and the nativity of children suggest that this assumption is appropriate (Landale, Oropesa & Noah, 2014). A greater concern is how to treat absent parents who are part of children’s families, but not their residential households. Although absent parents are excluded by design from surveys limited to questions about parents in the same household as the child, this has few implications for inferences about the shares in different types of families for investigations that rely on anchoring strategies. This is non-trivial given the argument that determining family legal status from both parents may mischaracterize single-parent families when absent parents have no meaningful presence in the lives of children. The absent parent in this case would be irrelevant even though other children have contact and access to the resources of absent parents. Nonetheless, our results suggest that the effect of legal status is not conditioned by single parenthood. The role of legal status in the involvement of absent parents in children’s lives is a much needed topic for future research.

In closing, the association between legal status and poverty was emphasized here for illustrative purposes in the hope of providing a foundation for future research. Additional studies are needed to demonstrate how these factors intersect with other variables to exacerbate or mitigate the vulnerabilities of children. This will require additional attention to how family legal status is operationalized, especially the grounds for combining parents and statuses. Measurement decisions must be tailored to particular substantive issues, but these results demonstrate the value of routinely evaluating key assumptions. This will permit a fully informed portrait of how inequality in family legal status is reproduced as inequality in the life chances of children.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NICHD grants 5P01HD062498-04 and R24HD041025.

Footnotes

Those with visas permitting temporary residence for work, education, etc. are also part of the non-citizen population. Regardless, the different segments of the non-citizen population are understudied (Clark, Glick & Bures 2009; Glick 2010). No population-based study of family legal status among Mexican-origin children has appeared in Journal of Family Issues or Journal of Marriage and Family. Legal status is also ignored in 16 articles on “Family Complexity, Poverty and Public Policy” in The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science (2014).

Bean et al.’s (2011) application of latent class analysis (LCA) to parental statuses and changes in statuses is noteworthy even though its relevance is tangential, at most. LCA assumes distinctions are latent; that is, not directly observable. In contrast, we assume status is observable from direct questions. Moreover, they examine changes in the statuses of adult respondents’ parents between time-of-entry and interview without synchronization to childhoods and without showing how statuses intersect.

Estimates for the undocumented share of the non-permanent resident population in the United States range from 87% to 93%, irrespective of origin (Hofer, Rytina, & Baker, 2012; Gonzalez-Barrera, Lopez, Passel, & Taylor, 2013; Passel & Cohn, 2011). Although difficult to determine, this share may be higher for California’s Mexican population. Mexico is the largest source of undocumented migration and the state is a major destination for those who enter the country without inspection or with a temporary visa and remain when it expires. There were 2.8 million undocumented Mexican-origin residents in California in 2011 (Hofer, Rytina, & Baker, 2012).

Non-response is inflated by those who did not complete the screener. There is no equivalent survey of children in the state for comparison, but the survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control as part of the California Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) is informative. The response rate for adults in the 2009 CHIS is the same as that for the 2007 BRFSS and slightly lower than that for the 2009 BRFSS (California Health Interview Survey, 2011).

All datasets have advantages and disadvantages. Advantages of the CHIS include direct questions on both parents (regardless of household) and reasonable levels of item nonresponse; non-permanent residence is imputed for less than 5% of parents. In comparison, the “quality of data on immigration status is questionable” in the SIPP due to item nonresponse (National Research Council 2009: 116). The restricted geographic scope of the CHIS is a potential disadvantage, as is a low response rate if it results in non-response bias. There is no evidence of this even though a definitive assessment is not possible. Incidentally, questionnaire changes will compromise the ability to determine legal status in the 2014 SIPP (U.S. Census Bureau, personal communication).

The 2009–12 American Community Surveys indicate that 3.8% of Mexican-origin children (0–11) in California live with a step-parent (author’s calculations). Also, just 21 adoptions occurred per year from Mexico in 2011–2013 (U.S. Bureau of Consular Affairs, http://travel.state.gov).

Uncertainty exists due to imprecise language in the original source which might either preclude or require naturalized and native-born citizens to be combined (represented by the shaded area). Their verbal description also does not indicate how two cells would be classified (cells 4 and 13).

Another scenario is the availability of information only on mothers in two-parent families and either the mother or father who is present in single-parent families. This would place 28% in undocumented, 20% in permanent resident, 12% in naturalized and 39% in U.S.-born households.

The 2009 ACS indicates 22% of all children age 0–11 California were below the poverty line.

These results are consistent with condition indexes, variance-inflation factors, and tolerances that show estimates for mother’s and father’s status are neither harmed nor degraded by collinearity.

Another question is whether father’s status matters more than mother’s status. Wald statistics for Type III effects in multivariate models are greater for mother’s status, but the magnitude of differences depend on the reference. In the model limited to parent’s statuses, the odds ratio for the contrast between undocumented and U.S-born parents is slightly greater for father’s than for mother’s status (.23fathers vs. .36mothers). Contrasting naturalized citizens (.16mothers vs. .31fathers) and permanent residents (.47mothers vs. .66fathers) with the undocumented show greater differences among foreign-born mothers. Additional inquiry is warranted into why the status of each parent matters.

All covariates are significant in supplemental models. Poverty is highest among children of the least educated, the least proficient in English, and those without a parent who works full-time. Poverty is also negatively associated with the child’s age. This variable does not interact with mother’s status.

Because a large majority lives with two parents, the pattern of results for children in this type of family mirrors that for the overall sample. Both mother’s (Wald χ2 = 38.6, p < .001) and father’s status (Wald χ2 = 28.5, p < .001) improve model fit for children living with two parents.

Restricting the analysis to 836 children of undocumented mothers and foreign-born fathers reveals that the status of the latter is significant (Wald Test = 11.85, p<.01), largely due to a lower risk of poverty with naturalized fathers (odds ratio = .28, p<.001). The estimate for permanent resident fathers is 1.04 (n.s.) among children of undocumented mothers. Among the 759 children of undocumented fathers and foreign-born mothers, the status of the latter is significant (Wald 18.34, p<.001). Children of naturalized citizen and permanent resident mothers are less likely than those with undocumented mothers to be impoverished. Marital status is not significant and has no effect on associations for children of either undocumented mothers or undocumented fathers.

Contributor Information

R.S. Oropesa, Department of Sociology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802

Nancy S. Landale, Department of Sociology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802

Marianne M. Hillemeier, Department of Health Policy and Administration, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802

References

- Bachmeier J, Van Hook J, Bean FD. Can we measure immigrants’ legal status? Lessons from two U.S. surveys. International Migration Review. 2014 doi: 10.1111/imre.12059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean FD, Leach MA, Brown SK, Bachmeier JD, Hipp JR. The educational legacy of unauthorized migration: Comparisons across U.S.-immigrant groups in how parents’ status affects their offspring. International Migration Review. 2011;45:348–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2011.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borjas GJ. Poverty and program participation among immigrant children. The Future of Children. 2011;21:247–266. doi: 10.1353/foc.2011.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Health Interview Survey. CHIS 2009 methodology series: Report 4-response rates. UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; Los Angeles, CA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Glick JE, Bures R. Immigrant families over the life course: Research directions and needs. Journal of Family Issues. 2009;30:852–972. [Google Scholar]

- Coutin SB. The rights of noncitizens in the United States. Annual Review of Law and Social Science. 2011;7:289–308. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Homeland Security. Welcome to the United States: A guide for new immigrants. U.S. Ctizenship and Immigration Services, Office of Citizenship; Washington, D.C: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Yeung WJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Smith JR. How much does poverty affect the life chances of children? American Sociological Review. 1998;63:406–423. [Google Scholar]

- Fix M, Zimmermann W. All under one roof: Mixed-status families in an era of reform. International Migration Review. 2001;35:397–419. [Google Scholar]

- Fortuny K, Chaudry A. Overview of immigrants’ eligibility for SNAP, TANF, Medicaid, and CHIP. ASPE Brief. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Glick J. Connecting complex processes: A Decade of Research on Immigrant Families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72(3):498–515. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Barrera A, Lopez MH, Passel JS, Taylor P. The path not taken: Two-thirds of legal Mexican immigrants are not U.S. citizens. Pew Hispanic Center; Washington D.C: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Groves RM. Nonresponse rates and nonresponse bias in household surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2006;70(5):646–675. [Google Scholar]

- Groves RM, Peytcheva E. The impact of nonresponse rates on nonrsponse bias. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2008;72(2):167–189. [Google Scholar]

- Guendelman S, Angulo V, Wier M, Oman D. Overcoming the odds: Access to care for immigrant children in working poor families in California. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2005;9(4):351–362. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-0018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M, Greenman E, Farkas G. Legal status and wage disparities for Mexican immigrants. Social Forces. 2010;89:491–513. doi: 10.1353/sof.2010.0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoefer M, Rytina N, Baker BC. Estimates of the unauthorized immigrant population residing in the United States: January 2011. Office of Immigration Statistics, Policy Directorate, U.S. Department of Homeland Security; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hummer RA, Hamilton ER. Race and ethnicity in fragile families. The Future of Children. 2010;20:113–131. doi: 10.1353/foc.2010.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kincheloe J, Frates J, Brown ER. Determinants of children’s participation in California’s Medicaid and SCHIP programs. Health Services Research. 2007;42:847–866. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00624.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landale NS, Hardie J, Oropesa RS, Hillemeier MM. Behavioral functioning among Mexican-Origin children: Does parental legal status matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2015;56:2–18. doi: 10.1177/0022146514567896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landale NS, Oropesa RS. Father involvement in the lives of mainland Puerto Rican Children: Contributions of nonresident, cohabiting and married fathers. Social Forces. 2001;79:945–968. [Google Scholar]

- Landale NS, Oropesa RS. Hispanic families: Stability and change. Annual Review of Sociology. 2007;33:381–405. [Google Scholar]

- Landale NS, Oropesa RS, Bradatan C. Hispanic families in the United States: Family structure and process in an era of family change. In: Tienda M, Mitchell F, editors. Hispanics and the future of America. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 2006. pp. 138–178. [Google Scholar]

- Landale NS, Oropesa RS, Noah AJ. Immigration and the family circumstances of Mexican-origin children: A binational longitudinal analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2014;76:24–36. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman RL. Capabilities and contributions of unwed fathers. The Future of Children. 2010;20:63–85. doi: 10.1353/foc.2010.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Tourangeau R. Where do we go from here? Nonresponse and social measurement. The Annals. 2013;645:185–221. doi: 10.1177/0002716212464191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Reengineering the Survey of Income and Program Participation. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Oropesa RS, Landale NS. Immigrant legacies: Ethnicity, generation, and children’s familial and economic lives. Social Science Quarterly. 1997;78:399–416. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega AN, Horwitz S, Kuo AA, Wallace SP, Imkelas M. Documentation status and parental concerns about development in young US children of Mexican Origin. Academic Pediatrics. 2009;9(4):278–282. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passel JS. Background briefing prepared for task force on Immigration and America’s Future. Pew Hispanic Center; Washington, D.C: 2005. Unauthorized migrants: Numbers and characteristics. [Google Scholar]

- Passel JS. Unauthorized migrants in the United States: Estimates, methods, and characteristics. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; 2007. Working papers. No. 57. [Google Scholar]

- Passel JS. Demography of immigrant youth: Past, present and future. The Future of Children. 2011;21:19–41. doi: 10.1353/foc.2011.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passel JS, Clark RL. Immigrants in New York: Their legal status, incomes and tax payments. Urban Institute; Washington, D.C: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Passel JS, Cohn D. Unauthorized immigrant population: National and state trends, 2010. Pew Hispanic Center; Washington, D.C: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Perez VH, Fang H, Inkelas M, Kuo A, Ortega AN. Access to and utilization of health care by subgrops of Latino children. Medical Care. 2009;47(6):695–699. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318190d9e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. Assessing the representativeness of public opinion surveys. Washington, DC: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto K, Coltrane S. Division of labor in Mexican origin and Anglo families: Structure and culture. Sex Roles. 2009;60:482–495. [Google Scholar]

- Reimers C. Economic well-being. In: Tienda M, Mitchell F, editors. Hispanics and the future of America. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 2006. pp. 291–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero VC. Everyday law for immigrants. Boulder, CO: Paradigm; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens GD, West-Wright CN, Tsai K. Health insurance and access to care for families with young children in California, 2001–2005: Differences by immigration status. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2010;12:273–281. doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9185-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozco C, Yoshikawa H, Teranishi RT, Suárez-Orozco MM. Growing up in the shadows: the developmental implications of unauthorized status. Harvard Educational Review. 2011;81:438–472. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozco C, Hirokazu Y. Undocumented status: Implications for child development, Policy, and Ethical Research. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2013;141:61–78. doi: 10.1002/cad.20043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hook J, Bachmeier JD, Coffman DL, Harel O. Can we spin straw into gold? An evaluation of immigrant legal status imputation approaches. Demography. 2015;52:329–354. doi: 10.1007/s13524-014-0358-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hook J, Brown SL, Kwenda M. A decomposition of trends in poverty among children of immigrants. Demography. 2004;41:649–670. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H. Immigrants raising citizens:Undocumented parents and the young children. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhihuan, Huang J, Yu SM, Ledsky R. Health status and health service access and use among children in U.S. immigrant families. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(4):634–640. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.049791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziol-Guest KM, Kalil A. Health and medical care among the children of immigrants. Child Development. 2012;83(5):1494–1500. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]